In this how-to chapter, we apply the cultural and technical elements of the first seven chapters combined with best practice recommendations to describe a framework for devising, designing, and implementing knowledge networks. This is not a list of quick and easy recipes but a process of analyzing what you've got, clearly stating what you want to accomplish, and choosing from the available options to design the most appropriate social and technical structure.

Our technique is to present recommendations—based on our experience and the experiences of other experts in the fields of knowledge management and online community—for mobilizing and supporting internal communities that will benefit significantly by conversing through the Net. Our instructions will provide some shortcuts, but their main value will be in helping to avoid subtle pitfalls—the miscalculations in social assumptions or interface design that can significantly reduce the enthusiasm, participation, or creativity of a group. Participation is vital to successful knowledge sharing.

We preface our recommendations by reemphasizing that the culture must encourage people to converse with each other online. Our advice alone can't overcome internal resistance to taking conversation to the Net. Some groups working within rigidly hierarchical cultures are satisfied with creating isolated pockets of free knowledge exchange. That may be revolutionary, but it's not guaranteed to inspire a revolution in a resisting company. Fortunately, the trends are swinging in our direction, and more executives are recognizing that it's in their own and their companies' self-interests to support internal group interaction on their intranets.

We're about to describe the best ways to grow productive knowledge networks on a company's internal network. If we were growing productive tomato plants, we'd begin by making sure the ground—the growing medium—was well prepared for planting the seeds or seedlings. The ground in which a social network is planted is the culture in which it must take root. The manager of an online social network is like a gardener who must get the plants off to a healthy start and then nurture them to maturity and a fruitful harvest. A gardener, though, has more control over the soil conditions of the garden than a knowledge network manager has over the culture of the organization. And though knowledge networking will influence the culture of the organization once it's under way, its interaction will become productive much more quickly if the leaders of the organization assume part of the gardener's role.

In this case, we refer you back to Chapters 4, 5, and Chapter 6 where we explored the relationships of culture to organization and technology. Having those relationships in order is the preparation required for getting the most from this chapter. Four optimum conditions highlighted in those earlier chapters are described in Table 8.1.

With these four conditions fulfilled, the recommendations offered in this chapter stand a much greater chances of success.

Table 8.1. Four Optimum Conditions to Have in Place before an Organization's Knowledge Network Can Be Successful

CONDITION | WHAT IT MEANS |

|---|---|

Supportive leadership | High-level support removes the resistance to online conversation that stifles participation. Patient support allows time for conversation skills to develop and knowledge benefits to be delivered. |

A thirst for knowledge | Demand for online conversational opportunities and motivation for refining knowledge-sharing practices must be strong to bring together and launch an effective knowledge network. |

Internet-savvy throughout the organization | To take full advantage of the available tools for online conversation, the organizational culture must be aligned with the realities of Internet communication and an increasingly innovative marketplace. |

Collaborative IT department | Building effective online communities for knowledge exchange requires involved technical support that will collaborate with and respond to groups that are constantly learning how their conversation environment can be improved. |

In certain situations during the planning, launch, and maintenance of knowledge-sharing communities, the advice and guidance of outside experts are well worth their cost. On these occasions, consultants can save the organizations time and expense and make significant differences in achieving goals and high productivity. Table 8.2 summarizes the authors' recommendations on this topic.

A consultant with broad experience in social networking, online community, and organizational development can help your company prepare for successful knowledge networking by providing expertise in the following areas:

Cultural assessment and knowledge auditing. Chapters 5 and 6 explained the impact of certain traits of internal culture on the choice of appropriate technology and the design of online meeting spaces. Cultural assessment and knowledge auditing are valuable techniques for identifying those traits and determining the formats of interaction that work best with them. A consultant with extensive experience working with diverse organizations with different cultural traits and knowledge needs, and who understands the shifting social dynamics that take place when taking a culture online, will have relevant advice to offer a company going through that transition for the first time.

Table 8.2. Degrees of Necessity for Consulting in Various Situations

STAGE OF DEVELOPMENT

NEED FOR CONSULTING

TO DO WHAT?

Cultural assessment

High

Provide objective perspective drawn from experience with previous client organizations and groups. Point out traits that will help or hinder adaptation to online conversation.

Proposal

High

Align design of knowledge-sharing project with goals of company and culture of community. Advise on cost justification.

Pilot project

Medium

Identify existing conversational groups that would make the most effective pilot communities

Prelaunch

Medium

Train and coach leadership and facilitation skills, especially where accelerated learning is mission critical.

Design

High

Match traits and goals of the group with appropriate software, features, and environmental design.

Early conversation

High

Coach conversation leaders and content providers to achieve early success and identify potential core members of community.

Marketing

Medium

Advise on leveraging early activity to attract more members and expand concept within organization.

Identify potential pilot groups. An experienced consultant can help identify potential pilot groups whose natural tendencies to collaborate toward company goals through conversation qualify them to lead the way into the new knowledge-sharing environment. The consultant also can help the organization find existing internal networks or communities of practice that can serve as guides and prototypes for replication within the organization. Not all existing groups are appropriate pilots or models. Some use technologies not adaptable for use by other groups; others have membership requirements too restrictive for other groups to emulate; some are too informal, making them poor models for networks meant to get work done. A qualified consultant can recognize existing opportunities for leverage within the company that may be invisible to managers and executives.

Provide training and coaching. A consultant who has worked with groups adjusting to conversational interfaces can provide valuable training and coaching in community management and facilitation techniques. Although many workers now connect to a local network from their desktop, and a great number of them can reach the Internet, their interface with the company may only take them as far as information access and the basic necessities of email correspondence. Stimulating active knowledge exchange through conversation and taking those conversations online require new skills and new practices that may take time to discover without guidance.

Assist in appropriate interface design. Appropriate interface design for the size, style, structure, and goals of a knowledge-sharing group or an entire organization's needs is an art. Subtle features of the online interface can have a disproportionate affect on the behaviors and reactions of the people using it. Navigational clues (for example, the absence of links to "discussion" on the top-level page of the portal) and wording (inviting people to "join the community" when "join the conversation" is what they'd rather do) can encourage or discourage people from participating. Confusion can result from poor labeling or bad placement of navigational buttons within a discussion environment. The best practice elements of Web design are inadequate to cover the design of an online meeting environment. Most enterprise-level software products come bundled with limited consulting services or provide customer support through their corporate sites. But not even the software vendor has the cross-discipline expertise to make the conversation environment compatible with the community that a good consultant has studied and analyzed.

Advise on internal marketing. The best marketing method for attracting more people to an online community is the word of mouth of community members and exposure to the actual interaction of the community. Even the early stages of an organization's online conversations provide a foundation to build on. Someone who has experienced all of the life stages of virtual communities can help the organization identify social assets in the young online community. An experienced eye can identify participants who fill vital roles in social ecologies: leaders, facilitators, mediators, provocateurs, and initiators. A qualified consultant can help the organization respond to the suggestions and complaints that will inevitably come from the community as it gets used to its new virtual home.

If upper management hasn't initiated the idea of knowledge networking, it will probably need to be convinced that it's a good idea for the company. The job of convincing them is getting easier every day now that knowledge management is being accepted as an essential practice in most organizations. But there may still be resistance, especially to the more self-governing aspects and "out-of-control" perceptions of the conversational knowledge network.

In these days of tightened budgets, every proposal is likely to get microscopic scrutiny. New concepts, such as that of a knowledge network, will encounter even more skepticism because they haven't had the time to generate a lot of successful case studies. Even the cases where intentional, purposeful online discussion has demonstrably helped a company become more innovative or respond better to customers might be regarded as "not applicable to our situation."

In any organization contemplating a knowledge network for sharing information, one of two basic circumstances is true about the level of knowledge sharing in online conversations:

No organized online conversation is happening for the purpose of sharing knowledge. Whatever the company does, it will be breaking new ground for itself both culturally and in building new skills. It has no internal guides or "scouts" from whom it can learn.

©SociAlchemy

Such conversations have existed historically or are currently going on. An organization has a base of experience from which it can learn and possibly some internal leaders for the expansion of the practice within the organization.

Which one of these is truer affects the process of selling the idea to decision makers.

Let's look at circumstance 1, where no employees are using online technologies in any organized way to share knowledge with each other. Email is available to employees; there may or may not be an intranet or portal with online discussion space. A team or work group has discovered (and agrees) that a more effective environment and process for exchanging knowledge would help them and the company excel.

In such a circumstance, we recommend minimizing the time required to propose and sell the idea and maximizing the use of available technologies and existing social agreements to begin the online knowledge-sharing process. Learn by doing. Demonstrate incremental success. Follow the recommendations made later in this chapter under Spontaneous Conversational Communities, and once the network has proven its value, point to that success in a more ambitious proposal. By that time, the group will understand the technical improvements it actually needs for more productive mutual learning and for putting its shared knowledge to work.

Your organization might be open to the idea of skipping these learning steps and diving right in to redefining itself as a knowledge-sharing company. This is a challenge, and we know of at least one company (Buckman Labs, cited in Chapter 5, "Fostering a Knowledge-Sharing Culture") that has pulled it off successfully and become a good example, but full acceptance and adoption of its new system and practices took 3 years. Two conditions must be satisfied for the strategy of skipping the incremental grass-roots learning phase to be a good bet.

The CEO must be receptive to the idea. This is most likely if there are problems in the organization that she attributes to slow or inefficient knowledge flow. The proposal for a system that increases knowledge exchange may be just the thing she's waiting for. In such a case, the CEO sees the knowledge network as being in perfect alignment with the company's strategy and as a good means for achieving that strategy. We describe such strategic communities later in the chapter.

There is a base of experience in online conversation in the workplace. People who have spent enough time engaged in online knowledge-sharing activities outside the organization and understand its utility can lead the organization to implementing internal communities without having to discover how it works through slow, incremental experimentation.

The cost of the interface does not have to be a major obstacle in getting approval or starting the network conversation. In fact, simplicity sometimes works in favor of the social interaction rather than against it. In our experience, we've witnessed higher cohesion and interactivity in online communities where the interface was not ideal and presented users with some challenges. In groups such as the early WELL, the early incarnation of Women.com, and in many email discussion groups we've managed and participated in, lack of features and sophistication in the discussion software and online environment forced people to try harder to communicate. They had to solve problems as groups to make the interface work. They were forced to collaborate to invent solutions and raise the quality of the communication.

In taking the cheap and simple route, there are trade-offs, of course; some people won't participate if the interface lacks certain features. Some of the creative energy of the group is used up in figuring out its online conversational processes. But there is something Darwinian at work when the interface selects for the most committed and innovative users. The filtering effect of what amounts to an interface boot camp is actually a good way to select participants for the startup stages for an online community when what you want are some willing pioneers to settle the new environment and civilize it for the later arrivals.

In sum, where the organization has not yet invested in leveraging online conversation, make the best possible use of tools and internal resources that are already available. Build a pilot network using email or available message boards and take the interaction as far as possible using technology that doesn't cost the company anything. Set reasonable goals, provide good leadership, document achievements, and demonstrate improvements over previous methods of collaboration in the performance of network members or of the group as a whole. The best way to sell an unfamiliar concept is to demonstrate its potential to change the organization in alignment with its strategy.

Once an online conversational community has demonstrated its effectiveness within an organization, circumstance 1 is instantly transformed into circumstance 2, with experiential evidence to support the proposal. A track record and a functioning prototype will increase the chances of the proposal being approved.

The leap in effectiveness from conversations using email to conversations using a well-designed message board with content management can be significant depending on the group and the nature of its knowledge exchange. The proposal must outline how the current technology is holding the community back from achieving its potential. The specific gains that can be realized through better supported conversation must be detailed.

As described in Chapter 7, "Choosing and Using Technology," there is a wide range of software and platforms appropriate for knowledge networks. The scale of the conversational community must be large enough to justify the most expensive platforms by spreading out the costs over more users. There may be substantial costs for integrating the platform into the existing technology. There will be costs in training and refining the design once the platform is in use.

A joint proposal representing the needs of other groups within the organization stands a better chance of approval. There may be many other groups expressing the same needs to engage online through better software and wanting more training or more time to spend in online collaboration. The more groups that are allied behind the proposal, the more leverage there is for getting necessary funding. Be willing to compromise and accept software solutions that are less than perfect, at least as an interim concession. Different groups will have different visions of the ideal platform, but if the major features can be agreed on, all groups may benefit to a greater extent than any one of them could on its own.

Remember above all that it's the motivation and focus of the group, not the interface it uses, that is most responsible for the effectiveness of its knowledge exchange. It can be a blessing in disguise to be forced to bootstrap the community conversation from the ground up. If motivation and focus can carry the load in the beginning, the community will eventually earn itself access to better tools, and selling the idea will be relatively easy.

In summary, a group, community, team, or line of business that recognizes a need for more powerful online knowledge sharing should approach the appropriate decision maker with the following:

A proposal describing the needs and goals of the group that can be satisfied through online conversation

An explanation of the return on investment that the group will provide after it is empowered to converse online

A well-researched description, with pricing, of the ideal interface or platform that will fit the group's specific needs

Agreement with other groups with similar needs within the organization around a request for a shared platform that will serve them all for less cost than their respective ideal platforms.

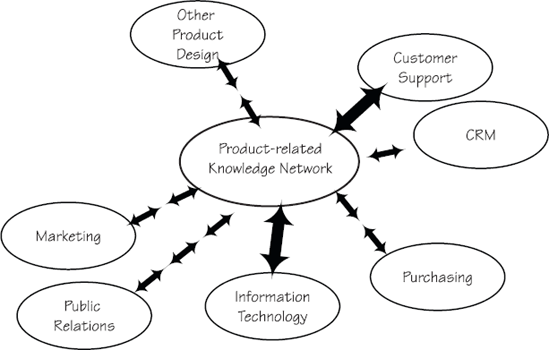

Groups that seek to share knowledge may not be aware of how important their eventual success will be to other entities within the organization. These entities— individuals, other groups. or entire departments—are potential allies in all stages of development of the knowledge-sharing community; their knowledge needs intersect and overlap. They should be identified, contacted, and recruited to support the development of the network. As Figure 8.2 shows, there can be a variety of tight and loose ties between a knowledge network and established units and teams within an organization. In this case, we picture a product-related knowledge network that can gather and surface relevant knowledge to serve these relationships. The power of the online knowledge network is largely in its ability to easily involve people who have the knowledge it needs or who need the knowledge it has. These are what we call stakeholders in the knowledge conversation.

At Cisco, the original community of networking professionals was envisioned as a closed knowledge loop where individual users of Cisco equipment would meet with each other and share discoveries, experiences, and knowledge. Cisco employees would be involved only as discussion facilitators, encouraging people to participate and contribute but not serving as information providers. However, it was not long before it became obvious how important these conversations might be to other internal knowledge centers within Cisco's organization. Customer service could learn tips and solutions that only the actual users of its equipment had developed. Marketing could learn the strengths and weaknesses of Cisco's and its competitors' products in the language of actual users. Product design and engineering could learn what customers wished for in the way of new products or improvements in existing products.

©SociAlchemy

When assembling the community, cast a wide net and consider who else in the company might be valuable members or associates, with interest in the knowledge being generated and with valuable knowledge to contribute. Consider who might stand to gain from the community's success. These groups not only help deliver the value of the knowledge network to the different arms of the organization, but they can also bring more leverage to proposals for upgrading systems and platforms. Engaging other stakeholders helps narrow the knowing-doing gap by providing more practical outlets for the knowledge being generated and exchanged.

Return on investment in a platform to support online conversation requires participation by the people it is intended to serve. The conversation must not only offer knowledge and information that people will log on to receive; it must stimulate people to contribute that knowledge and refine it through discussion, debate, and collaboration. Many people have experience in online conversation, but it's safe to assume that most have yet to try. What kinds of incentives work to attract them to become productive members of an online knowledge network?

There are four main categories of incentives to join: personal, cultural, goal-oriented, and compensatory. Table 8.3 summarizes the motivating forces that characterize them. Note that there is plenty of overlap. A personal incentive may also have to do with compensation. Cultural incentives also have their goals in the company strategy and mission. A personal goal may be to get a promotion or land a job managing the online communities.

The thirst for faster access to solutions is a powerful force and can attract many people to a conversation where answers are revealed, traded, and created through collaboration. That thirst often is enough incentive for the people who commonly form the core groups in knowledge-sharing communities. No external motivations, carrots, or sticks are required to bring them in. In fact, they probably initiated the community.

But most online conversations initiated to develop knowledge must draw in other people from outside the core group who also hold essential bits, chunks, and piles of knowledge that are difficult to access in any form other than conversation. If they don't show up at the party, the party can't satisfy its attendees. The knowledge development loop remains small and limited in scope.

Table 8.3. Four Main Categories of Incentives to Join a Knowledge Network

TYPE OF INCENTIVE | EXAMPLES |

|---|---|

Personal | I want learn from others I want to help others. I'm curious about the topic or practice. I love participating in online conversation. I want to display my skills in online conversation. I want to be recognized as an expert in my field. |

Cultural | Conversation is part of the company "way." Collaboration is the best way to get things done. Prestige comes with regular participation. To not participate is to be out of the loop. If you give, you'll get in return. |

Goal-oriented | Online collaboration is the best way to get things done. The project team is meeting online, and that's that! The knowledge network is the most direct way to locate and contact experts. Conversing online saves money in our department's budget. |

Compensatory | The company pays bonuses based on new ideas brought to the conversation. The company pays bonuses based on efficiency of operation. Promotions are partially based on regular participation in knowledge networks. New paid positions are being created for managing knowledge networks. |

Knowledge exchange won't happen online or off if there are cultural disincentives to telling others what one knows. If people feel that they will somehow lose opportunities, status, safety, power, prestige, or value in the company by sharing their expertise, their part in a knowledge-sharing conversation will be pretty quiet. A company may take pains to remove disincentives for contributing knowledge, but rather than rest at a neutral attitude toward sharing knowledge, there should be clear positive incentives for workers to join the online conversation.

Time constraints are a disincentive for many busy workers. One of the main reasons people refuse to adopt any new practice in an organization is the complaint of too little time. Their schedules are full, and asking them to learn and then participate in an activity that may cause them to fall behind in their other work is only going to anger them. Eventually, participation in the knowledge conversation will prove to be a time-saving activity, but there will be a transition period during which the employee has to make a choice: Should I drop what I'm doing and try this new thing or play it safe and keep delivering on my current responsibilities? Only management can make this decision easier and less risky for the employee. Some HR departments have begun allocating extra time for employees to spend seeking knowledge rather than reinventing wheels.

As we've described, an interface that puts barriers in the way of participation or that requires training and practice that consume valuable time can cause potential participants to lose interest early in the process. Using interfaces with which the population is comfortable, even if they lack key features for knowledge exchange, removes these early stage disincentives.

Financial incentives can be structured to reward individuals or to reward work groups, teams, and divisions. They can be offered as bonuses based on amount of participation in conversation, significant contributions to the knowledge pool, or effectiveness of leadership in a knowledge-generating community. There is little experiential evidence by which to judge the long-term effectiveness of such compensatory incentives.

Davenport and Prusak report that a large consulting firm "revamped its performance appraisal system to include contributions to the firm's knowledge database as an important part of compensation decisions."[80] This may work well in companies that sell knowledge but may not be as practical where knowledge is less central to the business strategy.

New software products record employee activities in ways that can be used to construct incentive reward systems. A product called "Clerity for Enterprise Knowledge Sharing" advertises that its "software and methodologies can create customized, automated incentive systems for your organization that can include points, recognition awards, linkages to human resource and employee review systems or other special programs."[81]

One of the most powerful and effective incentives is recognition by one's peers as an expert or holder of key knowledge in the group. Being invited to contribute to a conversation is like being invited to speak at a conference; even if you don't get paid, it feels good to be on stage as the center of attention. It feels good to tell people things that you know and they don't. Even being distinguished in the knowledge community's yellow pages directories can be satisfying.

For some, participation in a new or cutting-edge activity such as a knowledge network is reward in itself. The opportunity to be a big fish in a little pond or a pioneer in the company's newest project can be a great attraction. The opportunity to contribute to a community in a tangible way is refreshing to many people whose work seems to disappear into the ether with no response or feedback from its destination. In a conversational community, the likelihood of response is much greater.

Members of a community notice who contributes and whose contributions are most helpful. Reputations can be built in the online social context that may not be accessible in any other form to desk-bound workers. But reputations work in both directions. Those who exhibit selfish or impatient behaviors in a collaborative group can earn themselves social demerits. Redemption is fairly simple, though, because interaction is ongoing, and apologies and reparations are just as visible as offenses and insults. As we pointed out in Chapter 7, software that allows members of the group to rank each other's performance can inhibit participation in the early growth stages of the community. Use such features with discretion because they work best when people can't or don't take the time to form personal relationships.

The nature of a knowledge-sharing conversation is that helpful information and ideas move in both directions: from the participant to the community and from other members of the community back to the participant. Once the reliability of the exchange has been established, contributors of knowledge are likely to return because they expect that they will be enriched in equal measure to what they have given. Reciprocity does not necessarily work throughout the organization. People don't have agreements to reciprocate, and they have limited opportunities to do so in their irregular encounters with each other.

In an online environment dedicated to the exchange of knowledge, it's easier to keep one's books straight on who has contributed and who has not. Because the transactional record is there for everyone to read, a sense of balance and fairness is apparent, at least to regular participants. Once the knowledge marketplace has begun working, members know that they can offer what they've learned and that they can learn from what others offer. The incentive to participate becomes part of the marketplace mentality. Marketplaces are conversations.

The most basic incentive to participate in any community is the sense of community that comes with it: the feeling of being part of something bigger than one's self. The social rewards of membership in a group can be compelling, especially if the group has a purpose and an agreement to collaborate civilly toward achieving common goals. Leadership and role modeling are important in establishing such cultural agreements, and mastering challenges together reinforces the bonds that make teams and conversational communities more efficient.

Thus, the founding members or central interest of a knowledge-sharing community may be the most effective incentives for participation by others. Communities of practice form around common interests, and their motivation to pursue those interests can overcome even powerful disincentives like lack of time and primitive conversational environments.

Storytelling is as old as spoken language. As we related in Chapter 1, "Knowledge, History, and the Industrial Organization," it's the bedrock of knowledge transfer. In Chapter 2, "Using the Net to Share What People Know," we described how the WELL's True Confessions conference, with its autobiographical stories, was so influential in building trust within the community. Some people are natural storytellers, whereas others prefer to be on the receiving end of a good story. As a means of generating new ideas and explaining one's experience, stories are the ultimate knowledge transfer medium.

To take it one step further, we recommend without qualification that people use the Net to tell stories to each other. This is no longer a belief held by an intellectual fringe; stories are now being adopted as the format for everything from organizational change to product branding. Storytelling is a skill worth learning and could become a distinguishing feature of leadership in a knowledge-oriented culture. People react to stories; we seem to be wired internally to follow from beginnings to middles to ends and to interpret deeper meaning from the tales we hear. Stories elicit emotional responses in us and awaken the human part that wants to connect with others. And some stories make us think.

Within an organization, especially one driven by business values and profit, the humanizing effect of sharing experiential stories builds trust. Trust, as we've emphasized throughout this book, is powerful stuff. A knowledge network can be effective without fancy software, but it can't be effective without trust. People must feel safe to pour out what they know and believe to be true. Stories not only provide an easily interpreted explanation of knowledge, but they also reveal the storytellers as fellow humans, making them more real and trustworthy to the virtual audience.

The storytelling style should be modeled and encouraged in all online conversations aimed at sharing knowledge. Elements of effective storytelling should be part of the organization's training for knowledge community leaders and facilitators.

Describing how one learned something not only imparts the knowledge, it wraps that knowledge in an applicable lesson. True knowledge sharing is not the simplistic activity of asking and answering questions; it's a process of raising the collective intelligence and problem-solving capacity of the group or organization and providing the group with better handles for putting knowledge to work and implementing new ideas.

Stories also are more interesting to read and write than dry facts and information; they make participation in an online conversation more enjoyable and engaging, retaining more participants. In the pursuit of practical knowledge, stories provide context. They serve as a framework for delivering one's experience to others in ways that teach and inspire as well as inform and entertain.

Stephen Denning has a special view and purpose for telling stories. In The Springboard,[86] he describes the story as "a launching device aimed at enabling a whole group of people to leap—mentally—higher than they otherwise might, to get beyond mere common sense." This is more than a teaching function or simple knowledge exchange. It is more akin to intellectual stimulation or a call to action. Denning's stories are short and tend to describe possibilities based on actual events. They are carefully assembled and delivered. The springboard story is meant to catalyze organizational change.

Springboard stories share some common elements. They generally begin with a protagonist and what he calls "the predicament" that describes a problem the audience can relate to. They then move on to "the resolution of the predicament, embodying the change idea." This is meant to stimulate audience thinking, where they apply the change idea to their organization. The story wraps up either with "extrapolating the story to complete the picture" or with "drawing out the implications." Sometimes both elements are included. They help the audience connect the change idea with practical implications for their specific situations.

Denning's book assumes its readers will use his lessons in face-to-face situations. Drawing from his recommendations, we've adapted them to the virtual meeting place and present those adapted recommendations as follows:

Study and understand your audience. As Denning says, "You implicitly reflect the inner cravings of your audience." Your understanding will come across in your story.

In preparing a story for online presentation, emphasize qualities such as conviction, readiness, and a sense of ownership of the content of the story. Unlike stories told face-to-face, online stories are not usually presented repeatedly to different audiences. But once an online story is posted, it may be distributed to many different groups and individuals.

Unlike Denning's in-person situation, posting a story online allows the author to continue interacting with his or her audience, expanding on the story's theme, or using it as a starting point for developing innovative ideas. Remaining available for follow-up discussion is appropriate in conversational communities.

Take care in composing stories to be presented as text. Be economical in the use of words. Tell the story as briefly and concisely as possible. Break up the story into small paragraphs for easier reading. Use proper punctuation and check your spelling. Select a readable typeface such as Times New Roman and double space the lines. Your presentation is important.

Do not complement your story with visual aids (such as Web graphics, Power Point slides, attached documents with charts) unless it's necessary. Don't distract the audience from the essence of the message, whether it's a lesson, relevant experience, or a moral meant to mobilize the audience to action.

Emphasize key points in the story through whatever conventions are available in the medium being used. Embolden or italicize words, or in plain-text email, use punctuation marks to *emphasize* specific words or phrases. Isolate key sentences or paragraphs to ensure that they stand out for readers.

Denning advises springboard storytellers, "As a presenter, you must above all believe in your presentation." In the impersonal environment of the Net, where each participant in a conversation sits alone in front of a keyboard, it's tempting to treat what one posts to the screen lightly. Yet, when the discussion environment is defined by a collective hunger for useful knowledge, a story told with deep belief is likely to be read with correspondingly deep attention and respect.

Stories fit well within all three of the community types we are about to describe. One story may be the seed that launches a conversational community, or storytelling may be the preferred style for a knowledge exchange community.

Change is a dire need in many organizations and an aspired-to value in others. The springboard story—brief, illustrative, relevant, sometimes inspiring, sometimes unsettling—is a valuable instrument for catalyzing and directing change. It can be used by managers and team leaders but can just as easily be applied by frontline workers. As an igniter of innovative conversation or as an initiator of a new knowledge-sharing community, a springboard story can be quite effective.

We described what we did on the WELL as "talking through typing." Although the physical act of pressing keys and constructing words and sentences was identical to that used in composing a letter or writing a book, the sense we had as we typed those words was one of responding to something that someone had just said to us. And in the course of an hour, we would find ourselves feeling as if we'd been in 10 or 20 different discussions covering that many topics and involving perhaps dozens of people.

Talking through typing takes some getting used to. It takes some suspension of disbelief that the participants in the virtual conversation are actually as remote from each other as they physically are. The fact that the other participants might be down the hall, on another floor, in another building, or in another country is not so important in the exchange of ideas. But that remote-ness—along with the lack of visual and auditory clues that transmit mood, meaning, and style—must be compensated for in the online relationship. The style and quality of writing and reading can make a virtual conversation feel more sincere, detailed, trustworthy, and human.

As an aid to those engaging in continuing online conversation for the first time, we have compiled a list of basic competencies in effective online conversation (see Table 8.4). They begin with the practice of leading and initiating conversations, move into recommendations for composing messages and responses in a conversation, and gradually pull back in focus to describe ways of envisioning the conversational landscape.

Table 8.4. Basic Competencies in Continuing Online Conversation

KEY PRACTICES FOR EFFECTIVE ONLINE CONVERSATION | WHY THEY ARE IMPORTANT |

|---|---|

Create a tone of invitation and openness | Leaders are recognized by the attention they pay to motivating people to participate. Welcome newcomers and thank contributors. |

State the purpose and goals of the conversation | Make it clear what the discussion is about and what it is supposed to achieve. Be attentive to titles of discussions and subject lines of messages. |

Manage time constraints | Lead conversations to reasonable resolution, especially if there are time limits and deadlines. Open-ended discussions can become time wasters. |

Avoid unproductive argument | Argument is good, up to a point. When an argument cannot be resolved in the conversational forum, redirect it to email or "offline resolution" to avoid distracting the community. |

When two members are at odds, attempt to mediate their disagreement within the community's value in civility. Use backchannels to help resolve spats outside the conversation space. | |

Partition formal and informal conversation | Provide conversation areas for informal interaction that serve to build trust and strengthen relationships. Keep these areas distinct from those used for work, knowledge sharing, and problem solving. |

Avoid opening excess conversations | Given the number of participants, only a certain number of active conversations can be supported. Open new conversations only when there is demand. |

Identify people in official roles | Make it plain which members are in leadership positions or who have control over conversation management tools. Use special user names or symbols to designate them in the space. |

Those who post the most words command the most attention, but they don't necessarily contribute the most useful knowledge. Make sure prolific posters leave room for others. | |

Follow up on your controversial posts | Don't post messages guaranteed to elicit strong reactions and then fail to show up to respond. It's a conversation, and it's rude to stir things up and leave. |

Be accountable for your contributions | Be ready to back up information that is challenged. Again, in a conversation focused on knowledge, all parties should be fully engaged as information providers and experts. |

Communicate clearly | Take pains to compose messages carefully. Use uppercase and lowercase appropriately. Check spelling and grammar. Break up messages into small paragraphs and be concise. |

Be honest | Don't play a role different from who you really are unless the conversation manager has declared it to be virtual Halloween. |

The tone and wording of the first content in a new online discussion are very influential on the subsequent interaction. When the words and tone are inviting and communicate openness and enthusiasm, they are more likely to elicit response than dry, businesslike remarks. It's okay to overdo the emotional content somewhat to offset the impersonal nature of the medium.

A conversation space for knowledge exchange has a purpose. The question is: How specific is the purpose? This should be clarified at the outset of every new conversation or collection of conversations. A reminder on the entry screen to the discussion space is a good idea, and attention to the labeling of topics helps remind participants of their focus of interaction. If there is a deadline or time limit on the conversation, a facilitator should be minding the clock (or calendar) and leading discussion toward resolution in advance of the deadline.

Facilitation may also entail regularly summarizing lessons learned, points made, and issues still left unresolved. A facilitator, if there is one, has specific responsibilities that also should be made clear to participants. In some cases, a facilitator will serve in the role of debate moderator or even referee, charged with helping to resolve or settle arguments. The classic role of a facilitator is to help meetings and discussions stay on track toward a goal by getting people involved and clarifying their contributions to the conversation. If there are disagreements of substance, the facilitator points out the relevance of the disagreement to the group and attempts to lead it to consensus or resolution.

If some people hold special roles in the community, as moderators, facilitators, hosts, or leaders, their identities should be made clear to the rest of the community. New joiners won't necessarily recognize which members hold positions of authority, and for the sake of convenience and orderliness, they should have special user names or other obvious designations in the online environment.

As important to smooth knowledge flow as any other factor is the building of trust and relationship. These may happen offline already, but if there are no opportunities for community members to meet in person and spend time with each other informally, the opportunities must be provided in the online meeting space. The kind of interaction that builds trust and relationship is not the same as knowledge sharing, so it's wise to make a clear partition between knowledge exchange areas and social hangout areas as the site is designed and organized. In a simple email conversation list, participants should take the time to correspond with each other individually rather than overload list recipients with social chitchat.

Some veterans of the activity believe that online communities are good for extending conversations but bad for resolving them. Because in most cases the conversations happen without moderation or facilitation, they are subject to an effect that could be called the last word obsession. Everyone wants to get in the last word, and if the conversation has been left open to additional posts, the issue being discussed may never be settled. The cure for this is to include a moderator or facilitator in any discussion that must be resolved or in any community that shows tendencies to argue rather than reach agreement. Responsible participants can control their urges to get in the last word by simply paying attention to the sense of the conversation. Every conversation has a natural ending, and learning what that means is part of learning to be a good online conversationalist.

In the same vein, a knowledge-sharing community should learn the value of avoiding unproductive arguments. These not only distract other members from pursuing the knowledge they need, but they can poison the social well, eroding trust and making participation unpleasant enough to overcome whatever incentives drew people to the community in the first place. As the old Western sheriffs used to say, "Check your guns at the door." The purpose of the community is to get smarter, not dumber.

Some people avoid argument by posting something controversial and then logging out, without returning to deal with the responses they have provoked. This, too, can be deadly to a culture based on goodwill and trust. Accountability is important in professional communities, unlike some consumer-based forums where anonymous participation is invited. If you post something, take responsibility for it and be around for follow-up discussion. Be yourself; don't assume roles that will confuse people about your true identity, what you really think, and how you really behave. If the purpose is to exchange knowledge, don't mix fact with fantasy.

All participants in an ongoing online knowledge-sharing community have equal responsibility to be clear in their communication. This means being a good reader (the text-based analog to being a good listener) and taking part in coherent discourse. Good writing skills should be developed for the sake of the reading audience, and attention should be paid to details of spelling, grammar, composition, and the organization of thoughts. It all makes a big difference, not only in the regard in which the person will be held but also in the overall quality of the knowledge exchange. You'll appreciate good writers when you've been subjected to enough bad ones.

Remember that an online discussion community is a postocracy where those who post their comments and responses get more attention than those who don't. As Woody Allen said, 80 percent of success is showing up, and in an online community, that's how recognition works. If you make your presence known, you're part of the conversation. If you don't, then you aren't. And where reciprocity is a big incentive for participation, it's important that every member contributes his or her share to the knowledge pool.

In the simplest online communities for knowledge exchange, there is likely to be one focus, one purpose, and one fairly stable group of participants. Aside from the occasional scheduling intervention by leaders or initiators in the group, there are few organizational concerns. The main questions about membership are how many should there be and who should be invited.

As the community grows and diversifies—attending to wider ranges of knowledge and serving different groups and needs—organizational issues arise. These have to do with leadership, responsibility, and access rights. How will the discussion space be partitioned and controlled? Who will have access to the tools for managing the interface and the database of conversations? Will policies for participation be the same across all communities, or will there be different ground rules in different forums?

Each group must consider, for example, how it will determine membership. Will a certain amount of participation be necessary to retain access rights? Will members be allowed to read without contributing their own posts? Will lurking (reading the contents of online conversations without even logging on to the discussion space) be allowed or encouraged? In some cases, this can be a good thing; it allows people who are considering joining an online community to look through a virtual window and decide if it's the kind of interaction they'd like to be part of.

An original knowledge-sharing community has to decide if it wants to divide into subcommunities, and if so, how to arrange it socially and technically. It may also have to decide, once the original focus begins to break down, if those daughter communities should be spun off into their own separate conversational forums.

We described some best practices for leading online communities, but in terms of leadership, there are other roles to consider beyond moderator and facilitator. When there are many conversations going on in parallel, a coordinator or administrator may be needed to take care of the content and to do housekeeping through the discussion interface. This involves archiving or deleting old conversations, retitling conversations whose original titles don't match their content, and scheduling intentional conversations when specific knowledge needs arise in the organization.

The ideal situation in an online community is to achieve a level of self-governance that minimizes the need for oversight, leadership, and external control. Self-governance must be learned collectively; early attempts are prone to power struggles between people with differing views of what self-governance entails. The presence of what we call a benevolent dictator can quell small civil wars before they threaten the community and maintain control of the tools for removing damaging content and restricting access. A determined disruptor can ruin a community before it has a chance to grow, and it's sometimes necessary to ban such people until they understand the necessity of civil discourse.

Community health is of interest not only to the members but should be of interest to other people in the organization who depend on the knowledge generated and shared in its conversations. Social breakdowns do occur, and although there are no objective measurements to indicate the health or sickness of a community, there are ways to assess it that have meaning. A community leader should, for example, keep a conversation open for discussion of meta issues—the social and behavioral aspects (as opposed to the knowledge-sharing aspects) of the community as a whole. Meta conversations occur when the community talks about itself and how it's doing. They provide clues pointing to potential threats to trust and openness that can short-circuit knowledge exchange. They bring up warnings about dissatisfaction of key participants or problems with the interface that need to be remedied. Meta discussions are also important in establishing the community's sense of itself as a distinct social entity, which is an important aspect of the identification of its members with the group.

"Let's get together and talk about it."

That's the spontaneous beginning of a dialogue in which two people exchange their unanswered questions, their viewpoints, and their stories. Or that's the beginning of a discussion in which a group of people with a shared interest does the same. The stimulus for these conversations may be a pending deadline, a potential project, a crisis in the organization, or mutual curiosity. The only requirements for making the conversations possible are agreed-upon time and place—a time when the participants can communicate and a place where they can gather. The Net simplifies those requirements. People can now get together without synchronizing their schedules and without meeting physically.

Spontaneous communities that provide value to the organization are more likely to be approved, supported, and promoted. How do they provide value? Here are several ways:

They discover useful knowledge and solutions that more formal groups often miss

They learn on their own how to manage collaborative online conversation and group process

They incubate new ideas and develop prototypes that can then be put to use by others in the organization

They develop teachers and leaders for more widespread practice of online conversation and knowledge exchange

Spontaneous communities form (and dissolve) constantly within organizations whether the management is aware of them or not. Many of them make use of the internal resources such as paid time, office space, and bandwidth on the intranet. It's in the organization's interest to get some value out of them.

Some grass-roots groups come together spontaneously to form true communities of practice. We'll describe their special case later in this chapter. Other groups are less focused on pursuing common interests and more interested in having convenient access to an online forum where they can get reliable and expert answers to their questions. Such forums may form spontaneously, using whatever communications tools are available. Or they may be provided by an organization on its intranet as part of its knowledge management strategy. Often, though, spontaneous communities appear to fill a vacuum, becoming the organization's first experiments in online community.

Spontaneous communities may be the explorers and pioneers in an organization's migration to new cultural practices and new customer relationships. Working behind the scenes, they take chances and occasionally suffer setbacks, but at minimal cost to the organization. They gain experience in managing the social processes of online conversation and relationship building. They learn to deal with the shifting dynamics of group interaction over time. They become the organization's local experts in virtual community. Their accumulated experience is an asset that the sponsoring organization should both realize it has and put to good use.

Knowledge-sharing networks initiated by workers are fertile incubators for new ideas and practices that can enhance the organization in many ways. Collaborative networks build intellectual and social capital for the company. The initiators and leaders of productive spontaneous communities may help the organization to expand knowledge-sharing practices as internal consultants. Experienced knowledge networkers can author training programs to disseminate new collaborative skills throughout the organization.

Where do grass-roots efforts fit within an organization's hierarchy and management processes? Who owns these bottom-up projects and who makes use of their output? Who harvests the knowledge they generate through their conversations and the social techniques they invent? Who decides whether they are a valid and productive use of resources? How involved should a company be in providing and maintaining the technical means for their formation and operation?

Peer-to-peer networks link individuals and offer perhaps the optimum in personalization through the network. They encourage and support each user's decisions about who is included in their personal network and how to interact with each member of that network. The individuality of the interface in a program such as Groove may work both for and against fluid collaboration. The exclusivity that each individual can enforce can eliminate extraneous communications, but it can also block what could be valuable input. In practice, a P2P knowledge-sharing network should be managed in much the same way as an email list. If used as the operational base for a spontaneous knowledge network, the members of the network must pay attention not only to the focus of their interest but to what they might be missing by using an interface separated from the intranet.

There's a romanticized idea that cabals of workers, meeting in secret and independently developing projects below the radar of the organization—so-called skunk-works teams—are good things for the organization. Because of a few notable successes, legend has it that skunk-works teams are made up of geniuses, and their inventions invariably revolutionize the company, which looks dumb for having forced its best employees into secrecy.

In fact, skunk-works teams are not commonly composed of geniuses and do not often invent successful products. We don't hear much about their failures, of course. And because of their invisibility, whatever good things they do discover in the way of new knowledge and process are not made available to the organization. So although spontaneous communities might warrant some protection from the effects of overexposure and overpopulation, they should remain visible and active contributors to the organization.

That said, here are five recommendations for realizing value from spontaneous knowledge-sharing communities:

Appoint or hire someone to serve in the role of knowledge coordinator, or KC. The KC, in this case, is the recipient and distributor of things learned in spontaneous groups.

Announce to all employees that the company will support any spontaneous group conversation on its intranet or email system that identifies a representative who will stay in regular contact with the KC.

Make it clear that the company management will not interfere with the natural formation and development of these groups and their interactions unless it is specifically invited to participate. If appropriate, such groups can operate with restricted access. Groups that wish to remain private should be respected as long as they communicate with the KC.

Create a means by which knowledge of use to other groups or to the organization as a whole can be extracted from the spontaneous communities. These may be discoveries about the company, its products or services, suggested interface improvements, or the process of managing group interaction toward goals. A periodic community made up of community representatives and the KC may convene to build more knowledge about knowledge-sharing practices.

Report to the organization as a whole valuable lessons learned in spontaneous communities. If appropriate, evangelize discovered practices that improve on current practices. As spontaneous groups build histories, have their leaders, representatives, and active participants report on their experiences and best practices in meetings and online Q&A sessions.

In objective and dollar terms, the returns from spontaneous networks are difficult to measure. Anecdotal evidence is useful, though, because it's also difficult to measure the time lost and frustration experienced in seeking vital knowledge through database searching and not finding relevant answers. Spontaneous networks don't cost the company much to support and administer, but to make them as productive and useful to the company as possible, there are things the company can do to bring out the best in them.

Self-starting, self-governing, self-sustaining innovative teams that provide new knowledge to the organization are valuable assets. The same can be said about employees who communicate and collaborate productively without the need for micromanagement or IT handholding. A company can build these assets for the relatively cheap price of some meaningful cultural support. Creative people aren't as likely to initiate spontaneous networks if they suspect the company doesn't approve of such activities. They're much more likely to start networks if they know it's not only okay but appreciated by the company. So an unambiguous statement by the leadership of the organization, as we described a few paragraphs earlier, is important.

As we all know from our office lives, most people are satisfied to use whatever means are convenient and available to meet with and learn from each other. We meet in the company's cafeteria, in hallways and lobbies, or in temporarily vacant offices. It's not the environment that matters; it's the contact, the content, and the effectiveness of the communication.

In the online realm, people who simply want effective communication with a small group may be satisfied using email or the commercial messaging clients they download from Microsoft or AOL. They don't think in terms of asking the company to provide them with a new software platform. People intent on spontaneous group communication don't look for elegant solutions; they tend to adopt what is familiar to group members.

If the organization is aware that such groups are forming and recognizes potential benefits from their collaboration, it can provide support to help them succeed. It may be in the form of technical help in setting up email lists or custom configuring a private discussion space on the company intranet. It may be in providing authorization and entitlement for restricted access to the group's online home. It's important that the culture make people feel safe in proposing new knowledge-sharing groups and in selectively supporting them when they come forward with their ideas.

One characteristic of participants in spontaneous knowledge networks is their sense of independence and freewheeling exchange. As organic entities, they may invent or adopt styles of interaction unique to their groups and very different from the visible artifact level of the organization's overall culture. In an online environment, a very strong sense of unity is possible. That sense may be creative but also rebellious, confident but also vulnerable and wary of any management attempt to control or interfere with its self-governance. The relationship between an organization and the spontaneous knowledge networks it supports should resemble patron and artist: The sponsor supports the artist from a distance with faith that the creative spark will pay the patron back, and then some.

This is not to say that the organization must support every group that wants to use its network infrastructure as a regular meeting place; resources do have limits. But given limited resources, the organization should first support the aspiring communities that are most important to (and aligned with) its strategy. In Chapter 3, "Strategy and Planning for the Knowledge Network," we described "knowledge of maximum leverage," explaining how groups that seek, share, and generate such knowledge should get priority treatment and support.

Successful spontaneous communities advance strategy and cultural change most effectively if their work is transparent to the organization. They should serve as prototypes and learning models to bring maximum value to their sponsors. As Davenport and Prusak write: "it's not terribly difficult to envision ways of using knowledge more effectively in business strategy. The difficulty, of course, is in making changes to strategic programs and adopting the necessary behaviors throughout your organization." Spontaneous knowledge sharing helps push those changes along while modeling those necessary behaviors.

Communities that form spontaneously are just as likely to dissolve spontaneously. Because they are powered by passions and interest, they are subject to the periodic fading of those power sources or to the loss of key participants and leaders. The sponsoring organization should stay aware of the various segments of its knowledge network, not only to learn from them but also to know which of them are vigorous, which are dying, and which are going through periods of activity and quiet.

Networks formed by special project teams fire up quickly at birth and burn brightly, fueled by high focus and motivation until the project is done or the problem is solved. The knowledge sharing required to meet the deadline is intense. After that, their members disband and the activity fades out. Their reason for being has disappeared, and their purpose has been fulfilled.

Other networks form for a purpose that remains vital; the problem doesn't ever get completely solved but changes shape and requires the group constantly to adapt. These groups may show cyclical ebbs and flows in their activity and creative spirit. The organization should be aware of these dynamics in its management of the communications platform and support of the groups that are using it. There should be regular communications between the leaders of spontaneous networks and a clearly identified administrator of the communications platform being used so that communities going through lulls in activity are not mistaken for communities that have ceased to be.

Though we recommend that they serve as prototypes for the company, the success of a spontaneous conversational community can be its worst enemy. When such a group is regarded as a best practice example, labeled by the company with a gold star, it may gain prestige but lose the anonymity that was part of its appeal. Suddenly, waves of people want to join the community or observe what makes it tick. Executives in the organization want to analyze it and break it down for replication. Tech magazines may even want to write an article about it. Its world is changed into a fishbowl, and the uninhibited spirit that was responsible for its initial success is threatened. Most people stop feeling so open and creative when thrust into the roles of cast members in a dramatized online demo community.

External forces can shut down free-flowing conversation, but equally damaging to the creative spirit can be the inflated sense of self-importance that cohesive communities often develop, especially after being recognized as exceptional and successful. Such communities may become isolated from the rest of the organization, too exclusive to accept input from nonmembers. The WELL became that way after it began getting mentioned in the national press in the late 1980s. As new members appeared, they were challenged. Members began to be preoccupied with the value of their words and of the WELL's conversations to the detriment of the quality of the discourse that had attracted the press attention in the first place.

So how can the organization make the best use of a successful community's example without "killing the goose that laid the golden egg"? First, don't allow the online meeting places of such groups to become tourist attractions; keep them closed to all but their natural community members. If the community has something to teach the organization, arrange an online forum, event, or in-person meeting where its members can answer questions and describe their techniques. In general, use discretion when heaping praise on grass-roots conversational groups or on any productive collaborative groups, regardless of their sources. Learn from their success and provide a repository for lessons learned about their techniques, mix of talents, and style of communication, but don't turn the glare of the spotlight on them and distract them from their good work.

Beyond the realm of organizational values, missions, and policies, though, there must be an online medium available to people in the workplace through which they can participate in such communities. One medium remains, after almost 40 years, the most ubiquitous and understood means of group communication over the Net: email.

The founding participants of the Kraken at Price Waterhouse saw themselves as a group of "self-selected creatives" looking for a way to collaborate more innovatively than they could within the established structure of the large consultancy. To that end, they made use of their Lotus Notes email, a tool that was accessible to all employees and could be configured appropriately without having to submit a formal proposal, wait for funding, or explain their needs to IT.

Their technique was simple: Make a list of email recipients that was shared by all of the original members. Every message reached everyone on the list. Every response to every message reached the same list. Any individual was free to read or ignore each message. Success relied only on regular participation and the perceived value of new knowledge (or of appreciation) that each member realized by participating.

They named their interactive email list after a mythological sea creature of great power (the Kraken) that lived largely out of sight. Word soon got around about this low-profile but exceptionally productive knowledge exchange, and others were allowed to join—to have their names added to the email list. Even after the merger of Price Waterhouse with Coopers & Lybrand (another large accounting and consultancy firm), the Kraken continued to exist and grow to about 500 members. Its success has since spawned new internal email lists for knowledge exchange within the firm, serving different purposes and including different categories of expertise.

The Kraken is notable as an example of spontaneous knowledge exchange for several reasons:

It formed around recognition of common needs

It used a familiar and readily available communications interface

It followed no company-dictated agenda or schedule of deliverables

It cost practically nothing to create and to maintain

Its members saw it as an effective means for innovative collaboration

This last reason is especially telling because following the merger, PriceWaterhouseCoopers put in place an elaborately designed interface called KnowledgeCurve to expand its knowledge management activities. KnowledgeCurve was not used as often or with as much enthusiasm as the email-mediated communities. It was not considered by employees to be as effective in disseminating usable knowledge.

The strength of email is that it is so basic and adaptable. Every employee with a networked computer on the desktop now has an email account and knows how to send and receive messages. No new software is required; the IT department doesn't need to install or integrate new software into its systems. People are free to adjust their participation according to their available time. The tool does not drive the worker, so there is less resentment of its use.

Nevertheless, some practices should be learned and adopted to make email productive for knowledge sharing. Because there is so little structure—for example, an email conversation does not live on a specific Web page and cannot be seen as a scrolling list of responses on a series of Web pages—motivation and incentive serve as the only bonding agents to initiate the conversation and keep it going. New messages to the group must be circulating almost constantly or people tend to pull their heads out of the conversation and forget it's even going on.

Because most ongoing email conversations happen without leadership or moderation, it's contingent on the participants to maintain the focus, to make the list readable and worthwhile, and to occasionally reflect on what has been discussed, decided, and accomplished through the interaction. The original sense of purpose must be reconfirmed regularly to keep incentives for active participation alive.

An email list should be set up by having IT provide the initiator with ownership of a listserv run through the organization's mail server. Listservs offer options for managing the correspondence that personal email clients don't have. They offer convenient means for registration and joining the list and allow the owner to control access through the member list. A company portal can even provide the means for individuals to start listservs without help from IT.

One of email's main assets is also one of its main liabilities: the lack of a distinct home on the computer screen. Except for when new messages arrive, there is no location where the conversation can be found and revisited. There is less to keep track of, but when one wants to review the messages that made up a recent conversation, the medium makes such a task clumsy and time-consuming. For many people, an identifiable location on the Net where conversations can happen and be stored for reference makes more sense.

If the organization's culture is friendly to it, spontaneous knowledge sharing will happen when virtual meeting rooms are easily available. Many, if not most, corporate portals feature links to "community" or "collaboration" where discussion boards can be found. These are often dedicated to the business line associated with the employee, but some companies provide discussion space for general use and access, permitting conversation across business lines. As we pointed out in Chapter 7, "Choosing and Using Technology," commercial portal products vary in their ability to integrate applications from different vendors. Many portals bundle the eRooms message board, whereas others allow standalone discussion interfaces such as Web Crossing to be integrated. For spontaneous communities, the feature set is not as important as the easy availability. The motivation of the spontaneous group can overcome many shortcomings in the interface.

Email, as a home for ongoing focused discussion, has many limitations for scaling, expanding, and diversifying the conversation. In Chapter 6, Taking Culture Online, we described the differences between linear and threading discussion interfaces and their effects on social interaction. Either one of these offer advantages over an email list in that they both provide a clear, graphic depiction of the conversational landscape. Coherent conversation in email relies on the conscientious use of the Subject line to distinguish one thread from another amidst the flow of messages, but discussion interfaces display conversations and related threads in stable formats that can be navigated easily by new members of the community. Discussion systems provide a history of the conversations and how they developed. They include member profiles that can be referenced to add context and credibility to the opinions and knowledge expressed. Some of them include the ability to search the content of their discussion databases.

Discussion interfaces offer more options and flexibility than email lists, so spontaneous interaction can take different forms. It may include separate topics for new member introductions or the identification of a core problem to tackle or interest to explore. The initiator may want to conduct one conversation as an interview of an expert while creating a related conversation for open discussion of the expert's specialty.

Thus, open access to a discussion board located on the company intranet may be an improvement over the email approach. The board could provide an area for innovation where any member of the organization could start a collection of conversations, or a site administrator could answer requests by opening new private discussion areas for specific communities of knowledge exchange. Leaders of these areas could be granted the power to invite and provide access to members of a group, or the areas could require new joiners to go through a registration process. Either way, a discrete meeting place would be provided that would hold a record of all conversations and would be available for participation at any time of day.

Within certain populations, moderation or facilitation of the conversation is appropriate. This entails selection of which submitted messages will be passed on to the recipient group in the case of a moderator. Or it may entail regular guidance, clarification, summarization, and direction of the conversation in the case of the facilitator. The group as a whole must decide how much intervention is helpful or how much is distracting. More creative populations will opt to manage the conversation on their own, allowing the topic to drift in exploratory directions at times and then pulling it back on topic when required. Groups that are more interested in finding the missing knowledge held by its members and using it to solve ongoing problems may not care as much about having the freedom to widen the conversation.

Bringing people together online for the purposes of instruction, education, or inspiration certainly falls under the description of knowledge transfer. So does crisis management, and for many organizations not yet ready to support ongoing online conversation, the occasional time-bound event is a good way of getting the attention of many people at the same time and of persuading them to use online group communication tools that they don't normally use in their daily work lives.