Ethical Capital and the Culture of Integrity

Three Cases in the United Kingdom and New Zealand

Introduction

This chapter reviews three case studies on how integrity is defined and enacted through principles, policies, and practices of three organizations that regard integrity as a core value and Unique Selling Point (USP) in marketing their products and services. Integrity has been variously defined, and we will seek to address this central aspect of building sustainable ethical capital in organizations in our introduction and outline of this chapter in terms of paradigms, practices, and perspectives of the foundational ideals intended and applied.

In 2012, the International Year of Cooperatives, it is fitting that the three case organizations are based on the principles of cooperation. Each organization is, however, embedded in different local and national contexts, so legal constraints vary although they share some common philosophical foundations and historical bases. Two of the organizations are in the United Kingdom, arguably the birthplace of capitalism and the industrial revolution; in the United Kingdom, 2011 has been a year of resilience and growth of the cooperative sector. Currently “... the co-operative economy is driving a value of £33bn in the UK and engaging 800 million members and providing over 100 million jobs around the world.”1 The other case study organization is in New Zealand; a country known for its “clean, green” image and whose largest business is Fonterra, a farmers’ cooperative.

These three case organizations are from different sectors in the economy and range in size from an established Small and Medium Enterprise (SME) to a major retail bank. The three organizations will be compared and contrasted in terms of how they have not only interpreted but also enacted their ethical missions. Have they operated with integrity? How is this demonstrated in their policies and practices? What are the elements they share and are there any areas in which they differ in absolute or relative terms? What can we learn? We will focus on the organizational level rather than individual level and will assess the responses using a three-dimensional model to visually illustrate the organizations’ relative positions on each axis.

Defining Operational Integrity as Ethical Capital

The central problem with any social science research is that it deals with reflexive subjects (i.e., people). People think about what they do and how they present this to others in order to convey what they regard as an acceptable impression.2 It is fundamental to a research activity that distinctions are made between concepts, theories, and issues, at the different levels of analysis relevant to the domains under consideration. We propose to provide the reader with a brief overview of how integrity has been conceived or defined within the wider research literature.

The original usage is drawn from old French and Latin and has a connotation referring to wholeness in the sense of the word, “integer,” but we are less concerned with that meaning except insofar as it relates to the “wholeness” of organizational integrity as understood and routinely practiced in workplaces.3 Collins Concise Dictionary and Thesaurus proposes three slightly more modern definitions (with examples in italics): “integrity n 1 honesty 2 the quality of being whole or united: respect for a state’s territorial integrity. 3 the quality of being unharmed or sound: the integrity of the cell membrane.” On the same page, under the thesaurus section they elaborate as follows: “integrity 1 candour, goodness, honesty, honour, incorruptibility, principle, probity, rectitude, righteousness, uprightness, virtue, 2 coherence, cohesion, completeness, soundness, unity, wholeness.”4

For everyday purposes in organizations there are simpler definitions, though these all inevitably involve a continuum representing varying degrees of “fudging” or compromises with practical reality of leaders’ or others’ agency, company cultures, and emotional and cognitive understanding of the collective implications in their implementation of their boundaries and benchmarks,5 derived from the terms. In order to operationalize the concept we simply define organizational integrity as follows: The proactive structures, principles, and systems for accruing “ethical capital” by promoting, monitoring, and developing shared norms designed to identify and avoid potential conflicts of interest, abuse of office in any function, role, or location in the business. Issues such as the managers’ personalities, skills in managing others, managing relationships with peers and bosses, managing self and coping with setbacks and disappointments are thus accounted for in the definition.

Ethical capital might be described as the accrued differences between the goodwill “assets” and perceived moral liabilities of an organization as expressed in the coevolving relationship of customer loyalty and manifest employee integrity. Thus, assuming that the competitiveness of the product or service is comparable to rivals, then ceteris paribus, as integrity rises customer loyalty is also likely to increase as a part of the differentiating “unique selling point.” In line with that there is a need for an interactive and empowered set of relationships in the specific community using the cooperative services and products. However, as Kulik6 suggests, irresponsibility or lack of integrity in dealings with others is just as likely where “empowered” and “innovative” cultures exist but where certain conditions such as individualist incentives are also in place, hence the concerns expressed by our respondents about checks and balances in various places so that, in a period of economic crisis, the corporate integrity has to be perceived as above reproach.

The Three Case Study Organizations

The first organization from the United Kingdom, Suma Wholefoods, is essentially a retail workers’ cooperative specializing in health foods. Suma is also the youngest organization in the trio. Suma Wholefoods has an egalitarian culture and is a voluntary, open-membership, workers’ cooperative owned by its members as well as an SME and was initiated in 1975 by a group of friends. Members may be employees but employees do not have to be members. Members have extra duties and responsibilities but in order to avoid discriminating against those lacking formal qualifications, the only “qualification” required is ability. Suma has created a member job description outlining the duties of members over and above those of employees. Members are rigorously selected and have to undergo a compulsory 3–6 month probationary work trial period before they become eligible to apply for a “trial membership” in the first instance. Suma hires nonmembers as contract staff and as casual workers for peak business periods though many such workers then go on to become permanent members. As membership is voluntary, staff may opt to remain as nonmembers without any adverse impact on their employment although recurrent regeneration of member numbers is a requirement to keep the cooperative alive and some cooperatives have ceased due to declining membership or unevenly distributed workloads.7

It is also credited with being the very first organization to introduce fair trade products in the 1980s long before all the major UK supermarkets “jumped on the bandwagon” some decades later. Suma has an annual turnover in the excess of £25 million and supplies approximately 6,000 product lines to over 2,500 UK and overseas customers and employs 150 people. Their customers range from small independent wholefood retail stores to restaurants, hotels, bakeries, and food manufacturers. They also have grown their frozen food and export trade with countries such as Norway, South Africa, Lithuania, and countries further afield such as the Middle East. “Suma is the UK’s largest independent wholefood wholesaler/distributor, specializing in vegetarian, fairly traded, organic, ethical and natural products. We are a workers’ co-operative committed to ethical business” is how they describe themselves on their official 2012 website.8

Although they have an elected management committee, the Suma website proclaims the cooperative is not bound by “the conventional notions of hierarchy.” In practice that means that everyone gets the same pay, an equal say in major decisions, and is ready and willing to help out with any and all necessary tasks regardless of professional status or position. The Suma cooperative encourages multiskilling, enabling staff members to engage in many different facets of the business, and claims that this also improves job satisfaction, decision making, and performance overall. Business decisions and plans are made at regular general meetings with the consent of every cooperative member. “.... there’s no chief executive, no managing director, and no company chairman. In practice, this means that our day-to-day work is carried out by self-managing teams of employees who are all paid the same wage, and who all enjoy an equal voice and an equal stake in the success of the business.”9 Cooperative teams are delegated and self-managing with coordinators rather than captains, so consultation and communication skills are the key to their success.

The Credit Union

The second organization, First Credit Union (FCU), is the second oldest organization of the three studied here. FCU operates in New Zealand and is largely, though not completely, focused on the indigenous Maori and Pacific Islander populations in New Zealand as well as ethnic minority populations of more recent immigrant groups such as Indians and Africans. Credit unions are simply described as not-for-profit financial institutions owned by and democratically operated for the benefit of those using their services. FCU is one of the 20 members of the New Zealand Credit Union Association and has four branches in the North Island. It was originally formed as an initiative of some members of the Catholic Church and targeted at other members of the Church; St Mary’s Credit Union, as it was known, paid out its first loan of ₤100 in August 1955. Although it has since evolved to enable members of all faiths and no faith to become members, FCU retains the same philosophy and mission to support members to handle their finances with dignity.

Credit unions are registered under the Friendly Societies and Credit Unions Act 1982 and are not registered banks. It is a matter of pride that staff will readily tell you that they are not a bank, that they are locally owned by their customers, and are not-for-profit thus they are a trusted alternative to banks. The FCU, like others, is 100% New Zealand-owned and operated. They do not have the pressure to maximize profits for external shareholders, as banks do, so profits are redistributed back as a combination of better rates, fairer fees, responsible lending, and community support as well as improved customer service. The members’ funds are retained in New Zealand and are not used to fund any offshore investments.

The FCU’s lending criteria are “... humanitarian... FCU evaluates loans through a values-based approach placing character of the applicants above capacity and collateral; reversing the usual order of the ‘3Cs’ of loan applications procedures used in banking, in effect. All three factors are taken into account but… If the person/family’s character and local ‘groundedness’ or familial ‘centre of gravity’ are sound, then FCU adopts a constructive perspective of ‘How can we make this work?’ The respondent gave examples such as one case where a Pacific Islander family in the area had been refused credit elsewhere and was subject to a threatened mortgagee sale, the FCU arranged a loan to save the family from eviction.”

The FCU is also a member of the New Zealand Association of Credit Unions (NZACU)—the key New Zealand credit union association. FCU is also a member of the World Council of Credit Unions (WOCCU)—the leading international trade association and development agency for credit unions, again signifying their global engagement and alignment with international principles of credit unions as well as their parochial viewpoint.

The Co-operative Bank

The third organization is the Co-operative Bank from the United Kingdom. The bank is a major financial institution which has evolved from a retail cooperative started over 150 years ago. The largest consumer cooperative in the world is the Co-operative group in the United Kingdom. The group has an annual turnover of more than £9 billion, over 4,500 stores and branches, 87,000 employees, 4.5 million members, and plans to increase its membership to 20 million whilst doubling its support for green energy to £1 billion in future. The Co-operative group now also provides financial and banking services as well as retailing goods.

The original 1844 retail cooperative founding principles were as follows:

1. Membership was open to all.

2. Governance was democratic, that is, one person, one vote.

3. Profits were distributed amongst members and customers in proportion to purchases made from the cooperative as a member’s “dividend.”

4. Limited interest paid on capital.

5. Political and religious neutrality.

6. Cash trading only.

7. Education and personal “betterment” was encouraged.

The pioneers collaborated with other cooperatives and diversified into other businesses. The original set of principles were also extended and updated in the twentieth century to cover wider social concerns such as antiracism and antisexism. However, they still retain their aim to educate and advocate for their principles whilst operating responsibly and ethically.

In 1872 the Co-operative Wholesale Society opened a Loan and Deposit Department, which became the CWS Bank 4 years later. Almost 100 years after that, in 1971, the bank was registered under the UK Companies’ Act as Co-operative Bank Limited. The mission statement was drawn up in 1988 to reflect cooperative principles. The bank has over 340 branches since its 2009 merger with Britannia Building Society. The CWS group also currently has exclusive negotiating rights with Lloyd’s bank over the potential sale of 632 Lloyd’s bank branch offices. Although large by many typical cooperative and credit union standards, the Co-operative Bank is still not a mainstream, “high street” bank. The majority of the UK population do not put their money into the Co-operative Bank rather than the so-called Big four global banks. Furthermore, it is amongst the small minority of UK banks that has not been rescued by public funds from the brink of financial annihilation.

In relation to integrity and values, the Co-operative Bank’s website highlights its “Ethical Policy” as covering six major sections:

• Human Rights—endorsed by Amnesty International

• International Development—supported by Amnesty International vis-a-vis child labor and so forth and The Fair Trade Foundation

• Social Enterprise—in the shape of support for credit unions, community finance initiatives, and so forth

• Customer Consultation

• Ecological Impact—supported by Forum for the Future. The Co-operative Bank views itself as a “green advocate” and complies with ISO 14001

• Animal Welfare—endorsed by BUAV (antivivisection pressure group); as a matter of principle rejects customers involved in “blood sports.”

As recorded on the bank’s webpage, the Co-operative Insurance arm became the world’s first insurance company to launch a customer-led ethical policy to guide the social, ethical, and environmental aspects of its investments in 2005. The topics in the bulleted list above can be seen in the 2011 launch of an ethical operating plan across the entire Co-operative group’s retail as well as banking businesses. It will establish a benchmark for Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) on CO2 reduction, fair trade, and community involvement.

Furthermore, the Co-operative Bank will increase its involvement with schools in the United Kingdom and create 2,000 apprenticeships in the next few years, as well as invest £5 million annually to tackle poverty around its stores and branches. The most ambitious target of the group is the reduction of its carbon emissions by 35% by 2017, which the Co-operative Bank asserts is the most progressive policy of any major business in the United Kingdom. It has plans to ensure that by 2020 90% of its developing world primary commodities will be certified as fair trade.10

Research Methods

All the authors were familiar with one or more of the three organizations in a research or governance capacity. Nevertheless, we also conducted interviews with senior members of the organizations using the questions below to interrogate the organization as to their culture, processes, and formal systems for reinforcing behavioral integrity. We also examined webpages and documents produced in each of the organizations. We sought to qualitatively analyze, compare, and evaluate answers under the following 12-key thematic areas.

1. Vision and Goals—considers what the organization identifies and defines core ethical values, principles, and how these are to be integrated and embedded in everyday business conduct as well as strategy.

2. Leadership—assesses the “tone from the top,” that is, at senior executive and board governance levels.

3. Ethics Infrastructure—explores how the organization structures and organizes its ethics and integrity function, roles, or unit to ensure effectiveness.

4. Legal Compliance, Policies, and Rules—includes key legislation and the internal framework which supports ethical behavior and practice, for example, codes of conduct, recruitment policies, and guidance for staff.

5. Organizational Culture—addresses how ethical behavior is promoted or reinforced in the corporate culture and through the mission, vision, structure, and strategy processes.

6. Disciplinary and Reward Measures—considers how the organization sets and enforces its standards of ethical conduct, including by means of its performance appraisal process. Is ethical conduct linked to compensation?

7. Whistleblowing —explores how the organization treats individuals (both internal and external to the entity) who speak up and report questionable conduct. Do they encourage and support them or discourage them? Are they enabled to make confidential and anonymous reports and protected from retaliation or retribution and harassment by others?

8. Measurement, Research, and Assessment—seeks to determine the organization’s level of commitment to continuous improvement, based on their benchmarks and evaluation technologies and methods such as research into ethics strategies.

9. Ethics Training, Education, or Confidential Advice and Support—basically refers to what specific forms of provision are made to train staff in ethics, providing which skills, knowledge, and attitudes, and how far such training is integrated with other organization-wide training and support structures currently in place or planned.

10. Ethics Communications—summarized as how ethics and integrity initiatives including green issues are articulated and promoted, both internally and externally, and what the target audiences are.

11. Green Issue Policies and Awareness—summarized as concerning the organization’s awareness of “green” issues and how it deals with environmental sustainability concerns.

12. CSR—summarized as a broader theme describing relevant government relations, environmental consciousness, sustainability, and community impact sought by the organization.

In the 24 questions in the interview schedule there are a number of areas which overlap and are interrelated. This not only enabled some cross-referring and confirmation but also allowed for some extra probes to elucidate and clarify or extend the discussion of each of the 12 thematic areas. There are areas where the three case organizations overlap and a few where they differ in terms of normative expectations of staff and members and practical means to ensure good risk management without compromising core values and strategic performance objectives.

Illustrative Quotations for Each of the 12 Thematic Areas

Vision and Goals (Question 1)

The Suma mission statement is:

“... To provide a high quality service to customers and a rewarding working environment for the members, within a sustainable, ethical, co-operative business structure. To strive to promote a healthier lifestyle by supplying ethical, eco-friendly, vegetarian products.”11

The 56th Annual report of the FCU for 2010–2011, states:

“First Credit Union is a financial co-operative and our purpose is to provide financial services that enable our members to handle their financial affairs with dignity.”12

Paul Flowers, current chairman of the Co-operative Bank states:

“The compelling co-operative alternative is built on the same values that inspired the Rochdale Pioneers to create the first Co-operative business 168 years ago—voluntary and open membership; democratic control; economic participation; autonomy and independence; education and development; and concern for our community. It is the resonance of those values with customers and investors alike that underpins our ambition to become a real force in UK financial services.”13

Leadership (Question 2)

Suma as both an SME and advocate of worker participation is keen to ensure that it has a form of direct democracy, “Company officers who act as executive managers of Suma participate in the Management Committee, but have no vote. The nonexecutive (elected) directors have the authority and power and not the executives. This prevents the executive running the organization for its own self- interest.”

For FCU, “... the FCU leadership are expected to be exemplars of best practice not only in technical savings and loan administration but in maintaining a high ethical standard towards colleagues and members.”

Ethics Infrastructure (Question 3)

FCU has a code of ethics and an ethics committee charged with overseeing and judgment of relevant actions with respect to sanctions applied for ethical infringements at any levels in the organization.

Their code encompasses respect and fair and confidential treatment of staff and members irrespective of age, gender, disability, ethnic origin as well as ensuring legal compliance. FCU sees the trustees as a key part of the ethics infrastructure: “... The trustees act as the asset and liability Committee and are responsible for overseeing the treasury framework including approval of rates for loans and deposits. There is a complete trial balance each day and exception reports.... The Ethics Code also encompasses maintaining the FCU reputation, dress standards as well as indicating communication and behavior standards regarded as indicative of respectful behavior between people and in discussing others privacy and confidentiality is maintained rigorously....”

The Co-operative Bank’s “Ethical Policy” covers six major sections as listed earlier. The Co-operative Bank consults with members and staff to determine ethical policy and practice and has demonstrated that it is prepared to accept the costs of maintaining ethical behavior such that “.... The Co-operative Bank has withheld more than £1 billion of funding from business activities that its customers say are unethical.”

They further state “... Our asset management business introduced the world’s first customer-led Ethical Engagement Policy, and is committed to use its influence to push for improvements in the social and environmental performance of its investee companies.”14 Suma believes that their democratic structure and decision-making apparatus serve the same purpose as the Co-operative bank’s customer-led Ethical Engagement policy.

Legal Compliance, Policies, and Rules (Question 4)

Each organization fully complies with domestic and, where relevant, international legislation regarding employment law, licensing requirements as financial institutions, and reporting requirements. Each asserts that they go beyond the minimum requirements. FCU respondent states, “There is a legal regulatory compliance environment that relates the governance and capital requirements, loans issue and debt provisioning. The Credit Union is registered under the Friendly Societies and Credit Unions act 1982 and its operations are monitored for compliance by the Trustees Executor Ltd.... There are internal financial audits and financial reports are independently audited.”

Culture (Question 5)

In Suma, “The General Meeting [GM] of the members agrees strategies, business plans, and majority policy decisions. Such meetings take place 6 times a year. The General Meeting decisions are mandatory on all members. Six of the GM members are selected to form the Management Committee (MC) during whose weekly meetings the implementation of the agreed business plan and other GM decisions are initiated. MC members act as Suma’s elected directors, appointing company officers, personnel, operations, finance, and function area coordinators.”

In FCU “... Members, staff and the community are active stakeholders.... Members and staff shape the culture in a mutually interactive manner e.g., in custom and practice such as ‘no talking out of school’ about business, in reference to the community initiatives and to other areas such as perceived worries of staff and members about security.”

Of course Suma and FCU are smaller organizations although the staff members in FCU are more geographically dispersed of the two with branches across the North Island of New Zealand. Thus, some differences in scale and scope of operational and organizing arrangements might reasonably be expected to impinge on processes for stakeholder involvement, especially in routine matters.

The scale of operations is much bigger in the Co-operative Bank, although they maintain a democratic approach involving consultation by the management team with staff and members “…Asking cooperative members (including employees) to feed into the policies by way of open consultation” and getting “... staff buy in at all levels.” The respondent at the bank further indicated most effort in the organization was directed towards gaining staff input and support for policies, although they are also influenced by the efforts of environmental pressure groups.

The extent of the norms of equality, mutuality, and reciprocation of obligations between staff and customers and within the staff cohort varies across the three organizations. Broadly, the Co-operative Bank is on the conservative end of the continuum and Suma is closer to the radical end with FCU somewhere between the two. So for Suma, “All Suma staff, member, employee or casual, receive the same daily net wage plus allowances and overtime. Job variety is emphasized within the firm, drivers will drive for a maximum of 3 days and then be employed in the warehouse or office. Office workers are required to perform manual tasks for a minimum of one day a week.” As members of a workers’ cooperative, this way of organizing staff employment is not unexpected, however, it does possess unique elements which are not seen in the majority of customer owned cooperatives. However, for the FCU “... some ‘rules’ were developed regarding members wearing ‘hoodies’ and ‘shades’ in the premises—a common robber’s ‘uniform’—and use of profanities when speaking to staff or others. Members have also taken this on board and begun spontaneously to exercise additional ‘respect’ by removing gumboots before entry as is customarily done on entering houses in the New Zealand community.”

Disciplinary and Reward Measures (Question 6)

Many organizations now tie ethical behavior to employees’ performance reviews or career goals—though this alignment and respective action depends on reliability of data gathering.15 “FCU has had only had to dismiss two staff for serious violations in 30-odd years in the Credit Union.” As regards rewards, “FCU has no KPIs pushing loans or performance management.”

Suma has indicated that their democratic scrutiny processes ensure transparency and prevent or reduce opportunities for staff or members to engage in unethical behaviors and “… the co-operative structure of the organization ensures that any policies are followed by consensus. Additionally many members of the co-operative are involved, both in the course of their work and on a voluntary basis, in environmental and social initiatives.” The Co-operative Bank “... is the only UK bank with an Ethical Policy that is voted on by its customers and their Ethical Engagement Policy was launched after consultation with their insurance and investments customers.”

Whistleblowing (Question 7)

Suma considers that their democratic systems, as discussed above, negate the need for a specific whistleblowing policy or structure.

FCU currently has no formally assigned whistleblower support structure but suggested that the trustees as independent, community representatives, scrutineers, and auditors perform that role by default.

The Co-operative Bank has a committee meeting at least four times a year dealing with risk review arrangements whereby staff may raise concerns, in confidence, about possible wrong doing in financial reporting or other matters (i.e., whistleblowing).

Research and Assessment (Question 8)

The Co-op bank has a continuous structured review process involving CSR accounting and financial audits and a series of public reports covering current or projected issues relating to measurement, research and assessment. First Credit Union is closer to the Co-op approach and includes reports from external agencies, trustees and consultants such as S&P. On the other hand, Suma relies on plenary meetings to agree on current and future research assessment and metrics.

Ethics Training or Confidential Support (Question 9)

Suma’s ethical policy seeks to ensure they “... source goods at the best possible quality and price within acceptable ethical parameters” and such goods must fulfill Suma’s criteria such as promoting fair trade, “green,” GM (genetically modified)-free, cruelty-free and healthy, vegetarian, eating. Further they aim to avoid or boycott products containing harmful food additives, with minimal environmental impact, and will actively boycott goods from countries or companies with proven poor human rights records.

Suma regard their proclaimed principles, transparent procedures, multitasking, and volunteering arrangements as largely fulfilling this training role; they also enable staff to attend or present at ethics and environmental workshops and seminars as part of their development.

The FCU interviewee commented that it was also a part of their culture to train staff well. He noted “there is extensive and continuous staff training and development in house and external professional education and training related to staff development or promotion e.g., for professional accreditation or university degrees. Staff get an initial training of 2 weeks including, where relevant, subsidized external courses, accommodation and transport, etc. Leaders and managers also attend WOCCU (World Council of Credit Unions) events, Strategic Planning, and training. This ensures a ‘pipeline’ of trained staff for succession planning and talent management purposes and builds commitment.”

Ethics Communication (Question 10)

Suma says that in addition to a structure promoting workers’ rights “Co-operative teams are delegated and self-managing with co-ordinators rather than captains, so consultation and communication skills are the key to their success.” They are well-known in the industry and it is very clear amongst staff and members that, for example, they will only sell “fair trade” and have a “zero tolerance” policy for sale of any nonvegetarian products.

Green Issues, Policies, and Awareness (Question 11)

We asked the respondents to rate their organization using the ladder of “green-ness” (Table 1.1).

Table 1.1. Ladder of Organizational “Green-ness”

|

Ladder of “green-ness” |

Summary description |

|

A. Militant Green |

“Activist” for Green cause |

|

B. Green partner |

Collaborates with activists |

|

C. Green Advocate |

Openly supports Green issues/cause |

|

D. Green Client |

Accepts advice by Greens on issues |

|

E. Neutral/passive |

Not interested, uninvolved, or unsure |

|

F. Green Consumer |

Use of Green products/services |

|

G. Suspect Green |

Ambivalent about Green issues |

|

H. Anti-Green |

Against Green causes |

Suma advocates vociferously and frequently for Green issues and is very aware and committed, regarding itself as occupying level A, top of the ladder, but noting that issues “... tend to revolve around balancing the need to get the job done in good time with getting things done as ‘greenly’ as possible. For instance, waste segregation (keeping cardboard and plastic packaging separate) sometimes suffers when the warehouse is being cleaned up in a big hurry before the day’s order picking starts. Additionally, there are members of the co-operative who need constant reminders to switch off office equipment when they leave, rather than leaving things on stand-by.”

At FCU, they regard themselves as occupying level C on the ladder of Green-ness, see Table 1.1. The respondent provided documentation and reports to sustain the comment that “First Credit Union also has a sustainability report and several initiatives including sustainable offices, recycling, tree planting, university/polytechnic/schools’ based activities and awards for sustainable endeavours.”

Co-operative Bank’s website highlights its “Ethical Policy” covering Ecological Impact, supported by Forum for the Future. The Co-operative Bank views itself as a “green advocate,” complying fully with international benchmarks such as ISO 14001 and as noted above as having plans in place for 35% more reduction in its carbon emissions by 2017.

CSR (Question 12)

Some observers perceive an instrumentalist orientation of many CSR and ethical projects and regard that element as tainting the beneficial outcomes. Thus, the Suma representative interviewed replied that “vendors of management consultancy solutions who… assert that there are greater profits to be had by adopting such measures. Pursuing objectives that favor ethical and environmental standards, becomes rather suspect when such pursuit is profit motivated.” It was also stated that when using Google to check CSR, one would find Kellogg’s on top of the list and yet a “Which?” survey in 2006 called “Cereal Offenders,” which analyzed 275 major breakfast cereals from leading manufacturers on sale in the UK supermarkets indicated that 75% had high levels of sugar and around 20% had high levels of salt16 although some have since been reformulated to reduce salt and sugar content.

Nevertheless, the latter comment does have to be tempered by pragmatism and business realities that necessarily intrude into moral calculation for Suma too. The cooperative is an SME and business survival means it does have to take account of costs as the respondent indicated, “…the cost has to be carefully assessed and the operating period over which any such cost can be amortized can be taken into account. Our business works on very small margins so operating costs feature heavily in such decisions.”

Like Suma, the business practicalities of the FCU have also to be taken account of and “Staff meetings are rotated—sometime staff members are accommodated when living away from home in their role as temporary cover! The IT software used allows staff also seconded temporarily to other offices to meet work role requirements at their own office as well as getting to know branch colleagues and form an understanding of local areas. There is also communication through the staff newsletter.”

David Anderson, the Co-operative financial services chief executive, is quoted as saying, “... those things that started out in the Ethical Policy have become Public Policy and we want to lead that Public Policy forward... with the revisions to the Ethical Policy that are being made now. The fact that 80,000 of our customers have participated in updating it just shows how important it is to them and we think... a third of the Bank’s profits come from customers who’ve joined it just because of the Ethical Policy. So, it’s been a real differentiating factor for the Bank. It’s been part of our heritage and we see it as central to what the Bank stands for going forward.”17

It is not only employees whose actions may tarnish an organization’s reputation and diminish its ethical capital. For example, it has been argued that the perceived reputation and integrity or publicly accepted legitimacy of Finnish Forestry companies became questionable due to the unethical tactics and actions of their Brazilian business partners, and thus their integrity was called into question when they did nothing to challenge the Brazilian partner with respect to CSR.18 The Co-operative Bank also “seeks to change companies from the inside, by engaging with them on social, ethical and environmental issues” according to its website. The Co-operative Bank interviewee suggested that they are “not unique in having some of the policies e.g., Food ethics in the grocery business but several are bespoke to the Co-operative and to the bank.”

Analysis: Integrity Vectors

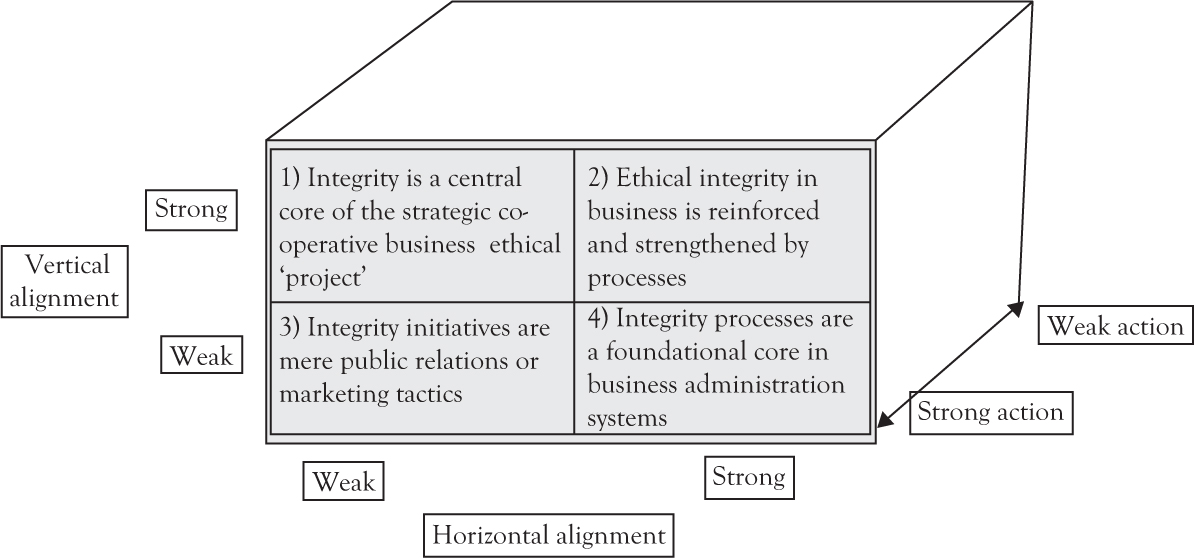

We decided to opt for a more “rounded” view by adopting the idea of three-dimensionality from the Gratton and Truss19 model for analyzing strategic HR alignment in organizations. Regarding levels of impact on business, values may be regarded as a strategic vector (vertical alignment), tactical vector (horizontal/process alignment), or operational vector (action/implementation alignment). We plotted the various responses to the interview questions against each of the vectors in Table 1.2 and this allows us to later present a visual representation of the three axes of the alignment, their relative strength, and overall trajectory of corporate integrity. This will enable executives to review corporate integrity and make needed changes in specific areas to build a coherent, balanced, and integrated ethical strategy.

Table 1.2. Ethics and Integrity Themes Comparative Overview

|

Integrity theme |

Suma |

Co-operative bank |

FCU |

|

1. Vision and Goals (Vertical–Strategic) |

Stresses democratic values and practices of staff/member empowerment in General Meetings (GM) to decide strategic development |

Stresses Co-operative Bank’s principles of customer consultation on strategy and legal accountability of the organization executive |

Stresses strategic community values, of founding (“people helping people”) philosophy |

|

2. Leadership (Vertical) |

Direct participation of all staff in strategic decision making in MC |

Hierarchical decision making but with some staff consultation on decisions on strategy |

Chairman = “head coach,” Board of trustees ensures community input on strategic decisions and scrutiny of leadership and operations |

|

3. Ethics Infrastructure (Horizontal–Processes/tactics) |

Well-developed policies and practices on membership and employment |

Well-developed policies and practices |

Well-developed policies and practices |

|

4. Legal Compliance, Policies, and Rules (Vertical–Horizontal) |

Goes beyond legal compliance-extending actions to fair trading in sourcing supplies |

Compliant and refused major deals to ensure principled business and CSR |

Systematic adherence to compliance and to founding philosophy |

|

5. Organizational Culture (Horizontal + Action/depth—In Operations) |

Somewhat Kibbutz-like everyone helping out in work tasks without status distinctions, democratic vote on decisions at GMs |

Corporation structure and roles related to position description and member consultation on key changes or strategic direction and initiatives |

Corporation structure and roles related to position description and member-directed AGM. |

|

6. Disciplinary and Reward Measures (Horizontal + Action/depth) |

Collectively determined and administered sanctions and flat rate salaries dependent on collective agreement |

Standard formal ethical and disciplinary codes and some bonuses based on targets |

Following 3Cs for loans; rewards closely related to values and serving client needs |

|

7. Whistleblowing (Horizontal + Action/depth) |

Not formally but issues may be raised at meetings and put to a vote |

Yes—formal structure in place |

None in place formally but see trustees as a channel enabling whistleblowing |

|

8. Measurement, Research, and Assessment (Action + Horizontal) |

Transparent measures agreed and reviewed at meetings |

Public Reports/CSR accounting/Financial audits |

Legal/CSR reports/S&P audits, Trustees’ reports |

|

9. Ethics training, Education or Confidential Advice and Support (Horizontal + Action) |

Cooperative system and democratic voting, on-the-job training infrastructure, otherwise Ad hoc training systems |

Some formal training related to levels of job and role |

Some training for all (e.g., on induction and orientation on operations plus Trustee role) |

|

10. Ethics Communications (Horizontal + Action) |

Centrally Embedded in systems and corporate literature |

Centrally Embedded in systems and corporate literature |

Centrally Embedded in systems and corporate literature |

|

11. Green Issue Policies and Awareness (Vertical) |

Very explicit green-ness (Militant Green as per Table 1.1) |

Green partner (see Table 1.1) |

Green advocate—passive (see Table 1.1) |

|

12. Corporate Social Responsibility (Vertical + Action) |

CSR = core component of strategy, processes and impacts on operations |

CSR = core component of strategy, processes and impacts on operations |

CSR = core component of strategy, processes and impacts on operations |

Each of the three organizations regards these values as realistic as well as central to their “brand” marketing and thus as more than mere rhetoric. However, each applied these differentially across these vectors, for instance, in terms of how explicit, systematic, or well-actioned their policies, codes, and procedures are. We have illustrated some of the differences with brief quotations and comments on each of the case organizations. The strength of each of the three dimensions is represented in Figure 1.1 as height, width, and depth (i.e., vertically, horizontally, and from front to rear of the figure).

The Co-operative Bank has a “clean” image despite some recent concerns by some commentators.20 There are suggested downsides insofar as the responsiveness of the bigger cooperatives to change and the level of bureaucracy required, disseminating and canvassing opinion,21 though the Co-operative Bank is amongst the very few UK banks that survived the global financial upheaval without a government bailout which they attribute to their philosophy and not seeking quick profits. In line with other management concepts, growth in size for the Suma collective may yet pose more of the kinds of conflicts they already see between espoused ideology and practicality though these need not prevent them from growing the business with integrity as the Co-operative Bank has attempted to do. Growth for cooperative enterprises is an under-researched area and thus there is plenty of scope for further research in each of the three cases.

Conclusion, Recommendations, and Future Research

These three organizations are neither typical of modern capitalism nor for-profit corporations (in terms of their cooperative missions and structures). Further, they are each at different stages of their organizational “lifecycles.” Nevertheless, the three organizations clearly see themselves as being part of a wider social change and riding the crest of a wave of ethical consumerism. According to the interviewees, there are bottom-line benefits accruing as a result of ethical capital growth from their integrity. In implementing their values they perceive themselves to be at the leading edge in their respective sectors as we shall see below. In the postglobal financial crisis and upsurge of interest in co-operatives of various kinds, now is a good time to study their development paths.

Practical steps taken by cooperatives accommodate well the following 10-step process—a variant of one outlined elsewhere by one of the authors:22

1. Champion and commit to transparent, organization-wide emotional literacy using a “no blame” approach and surfacing the “undiscussables” to give voice to all workers and members of the cooperative.

2. Engage proactively with key stakeholders and the wider community through a steering committee invested with genuine authority, influence at all organizational levels, and responsibility for the work.

3. Develop and articulate a shared vision, expressing the high hopes and dreams of all stakeholders at all levels in the organization in order to bring energy and a positive focus to the work systems.

4. Conduct a needs and resources assessment including emotional impact and resilience across the organization. Identify specific issues to address; build from what’s already in place and working well wherever possible.

5. Develop an action plan and timeline with sufficient flexibility to cope with emerging complexity in the business environment. Include the shared stakeholder goals and objectives as well as a plan for attaining, measuring, and evaluating their ongoing strategic alignment and using technology such as social networking tools to ease administrative and bureaucratic burdens whilst attempting to maintain active communication and participation of the whole community with enhanced accessibility.

6. Select evidence-based programs and strategies; begin building a shared vocabulary and framework of understanding. This creates consistency and coherence for the stakeholders when reviewing strategic identity branding, operational projects, codes of practice, or implementation concerns.

7. Conduct initial staff development for “onboarding” new staff to ensure that they fully understand and can apply with integrity and consistency the relevant principles as a practical frame of reference alongside technical best practice models embodied in behavioral guides or codes. This will be increasingly relevant in a period of growth.

8. Provide a technical support infrastructure as well as a values-based communication network and help staff or members become familiar with and experienced in the required skill set.

9. Expand instruction and integrate organization-wide, to build a consistent cultural environment and experiences for all involved.

10. Revisit activities—adjust for continuous improvement and emergent challenges. Check on progress to resolve problems early.

Key Terms

Integrity—defined as the proactive structures, principles, and systems for accruing “ethical capital” by promoting, monitoring, and developing shared norms designed to identify and avoid potential conflicts of interest, abuse of office in any function, role, or location in the business.

Co-operative—defined as a member-based form of organization structure based on open membership giving access to all. Governance is democratic (i.e., one person, one vote) and members regularly consulted on strategic decisions. Limited interest is paid on capital.

Credit union—defined as a cooperative form of not-for-profit financial and lending institutions owned by and democratically operated for the benefit of those using their services.

Ethical capital—defined in the chapter as the accrued differences between the goodwill “assets” and perceived moral liabilities of an organization as expressed in the coevolving relationship of customer loyalty and manifest employee integrity.

Three integrity vectors—the strategic direction of an organization, the organizational systems including its policy frameworks and the implementation or operational actions.

Strategic values trajectory—the direction, strength, and alignment of the overall patterns of interrelationships between the three integrity vectors on the emergent strategy of the organization. That is the direction and strength of the intersecting dimensions of strategy, systems and processes and actions taken to implement policies, goals, and mission across the organization and thus enabling “gap” analysis and corrective action by leaders.

Unique selling point (USP)—a marketing term which simply indicates what the organizational leaders believe, based on perceptions of customer preferences or key values the organization aims to project, are core “brand” values which “sell” the organization and its products or services in their market.

Study Questions

1. Using the themes as in Table 1.2, analyze an organization you are involved with as an employee, or volunteer, or as a member.

2. Critically reflect on any perceived gaps between leaders’ rhetoric and customer/employee reality.

3. Why are there such gaps?

4. How have these gaps arisen?

5. How might the gap be closed in future?

6. What sorts of visible measures, rewards, or auditing of ethical capital is required for best effect in the organization you are studying?

Further Reading

Allan, J., Fuller, D., & Luckett, M. (1998). Academic integrity: Behaviors, rates, and attitudes of business students toward cheating. Journal of Marketing Education 20(1), 41–52.

Benjamin, B., & O’Reilly, C. (2011). Becoming a leader: Early career challenges faced by MBA graduates. Academy of Management Learning & Education 10(3), 452–472.

Brown, M. T. (2006). Corporate integrity and public interest: A relational approach to business ethics and leadership. Journal of Business Ethics 66, 11–18.

BITC/Radley Yeldar. (2007). Taking shape—The future of corporate responsibility communications. Retrieved on March 6, 2007 from http://www.bitc.org.uk/ resources/publications/future_of_cr_comms.html

Carson, T. L. (2003). Self-interest and business ethics: Some lessons of the recent corporate scandals. Journal of Business Ethics 43(4), 389–394. DOI: 10.1023/A:1023013128621

Devinney, T. M., Auger, P., Eckhardt, G., & Birtchnell, T. (2006, Fall). The other CSR. Stanford Social Innovation Review. Retrieved on January 6, 2007 from http://www.ssireview.org/articles/entry/the_other_csr/

Entine, J. (2010). Eco marketing: What price green consumerism? Retrieved 16 February, 2012 from http://www.ethicalcorp.com/environment/eco-marketing-what-price-green-consumerism

Kasper-Fuehrer, E. C., & Ashkanasy, N. M. (2001). Communicating trustworthiness and building trust in interorganizational virtual organizations. Journal of Management 27(3), 235–254.

Kisamore, J. L., Stone, T. H., & Jawahar, I. M. (2007). Academic integrity: The relationship between individual and situational factors on misconduct contemplations. Journal of Business Ethics 75, 381–394.

Kizirian, T. G., Mayhew, B. W., & Sneathen, L. D. Jr. (2005). The impact of management integrity on audit planning and evidence. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 24(2), 49–67.

Lorsch, J. W., Berlowitz, L., & Zelleke, A. (2005). Restoring trust in American business. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.