Integrity and Anticorruption Actions in an Organizational Context

Introduction

This chapter seeks to discuss integrity and anticorruption actions in an organizational context, and suggesting innovative methods of integrity and corruption—prevention management in diverse organizations. It is an opening and invitation to further exploration for finding better ways of integrity competences in organizations of acquisition and management, in addition to building corruption-preventative contexts with the aim of constructing corruption-free organizations that benefit their owners, shareholders, and community stakeholders.

How can we define integrity, and integrity in an organizational context? In fact, there is no simple explanation to this term. Organizations can understand it differently. Integrity can be defined as a philosophy of consistency of actions, values, methods, organizational principles, expectations, and results. Integrity, as defined in the 2007 edition of the Merriam-Webster dictionary, is a “firm adherence to a code of especially moral or artistic values (incorruptibility), an unimpaired condition (soundness), and the quality or state of being complete or undivided (completeness).”1 Types of integrity include integrity of character and professional integrity.

Aristotle said: “Men acquire a particular quality by constantly acting in a particular way.” One of the keys to maintaining integrity is the ability to act not in one’s own interest but in the interest of others. Integrity is not something you are born with. It is something you learn and strengthen over time. It is a conscious choice you make that you have total control over.2 Integrity is one of the most important and often-cited terms of virtue. To put it in plain managerial words, integrity can be defined as the formal relation to one’s self and in an organizational context, it always has something to do with acting morally. In an organizational context we should examine the integrity principle of consistency. Is it possible to evaluate the manager’s behavior in the organizational context on the basis of a body of his or her integrity standards? The principle of integrity could provide us with ideas on how to solve these problems.

Integrity issues in organizations are closely related to the notion of ethics. The practical goal of integrity issues is to solve the problem of how to select the best decision in an organizational context in an ethically difficult business context. The main known tools for application of the principles of business ethics are principles and codes of ethics. The implementation of various concepts and ethics programs, for example Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), is not sufficient to maintain integrity in an organizational context.

Integrity issues are becoming increasingly important due to the internal business benefits and efficiency in searching for new customers, cooperating firms, and partners. It can be foreseen that issues of integrity in an organizational context are going to become increasingly important in the next few years. This is primarily caused by the crisis facing both organizations and sovereign states—mostly debt-ridden states—where organizations operate and there is reduced confidence in many companies caused by recent financial and socioeconomic crises.

Impediments to integrity skills acquisition in organizational contexts can be the result of the following: poor integrity management, a lack of consultation with employees and owners or their representatives, and CEOs or company directors who knowingly or unknowingly perpetrate a toxic management environment as they aim to implement a “bottom line profit” philosophy at all cost. Lack of knowledge and integrity competence transfer delivery in organizational settings can result in people delaying or refusing to communicate a philosophy of integrity in the managerial process. The personal attitudes of individual employees, which may be due to lack of motivation or dissatisfaction at work, can lead to corrupt practices in situations of insufficient or inappropriate integrity and anticorruption training in organizational contexts. Integrity, as defined in this chapter, suggests a person whose self is sound, undivided, and complete.

According to Wankel and Stachowicz-Stanusch, recent examples of “corporate, national and international ethical and financial scandals and crises have created a need to bolster the ethical acumen of managers through business education imperatives.”3 Their book, Management Education for Integrity, explains how curricula should be streamlined and rejuvenated to ensure a high level of integrity in management education, providing numerous examples of new tools, teaching methods, integrity sensitization and development exercises, and ethical management education assessment approaches. They suggest fostering integrity in business curricula, a critique of ethics education in management, measuring best practices in management education for integrity capacity, encouraging moral engagement in business ethics courses, management education for behavioral integrity, and a scenario-based approach as a teaching tool to promote integrity awareness.4

Corruption and Anticorruption

The Asian Development Bank (ADB), describing the term corruption, uses it as a shorthand reference for a large range of illicit or illegal activities. Although there is no universal or comprehensive definition as to what constitutes corrupt behavior, the most prominent definitions share a common emphasis upon the abuse of public power or position for personal advantage. The Oxford Unabridged Dictionary defines corruption as perversion or destruction of integrity, in the discharge of public duties, by bribery or favor. The Merriam Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary defines it as inducement to wrong by improper or unlawful means (as bribery). The succinct definition utilized by the World Bank is the abuse of public office for private gain. This definition is similar to that employed by Transparency International (TI), the leading NGO in the global anticorruption effort:

Corruption involves behavior on the part of officials in the public sector, whether politicians or civil servants, in which they improperly and unlawfully enrich themselves, or those close to them, by the misuse of the public power entrusted to them.5 The author concurs with the ADB judgment that these definitions do not give adequate attention to the problem of corruption in the private sector or to the role of the private sector in fostering corruption in the public sector. As a shorthand definition, ADB defines corruption as the abuse of public or private office for personal gain. A more comprehensive definition is available on ADB’s website.6

Corruption involves behavior on the part of officials in the public and private sectors, in which they improperly and unlawfully enrich themselves, those close to them, or both, or induce others to do so by misusing the position in which they are placed. Some types of corruption are internal in that they interfere with the ability of a government agency to recruit or manage its staff, make efficient use of its resources, or conduct impartial in-house investigations. Others are external in that they involve efforts to manipulate or extort money from clients or suppliers, or to benefit from inside information. Still, others involve unwarranted interference in market operations, such as the use of state power to artificially restrict competition and generate monopoly rents. More narrow definitions of corruption are often necessary to address particular types of illicit behavior. In the area of procurement fraud, for example, the World Bank defines corrupt practice as the offering, giving, receiving, or soliciting of anything of value to influence the action of a public official in the procurement process or in contract execution.7

Concurring further with the ADB sources, it is often useful to differentiate between grand corruption—which typically involves senior officials, major decisions or contracts, and the exchange of large sums of money—and petty corruption, which involves low-level officials, the provision of routine services and goods, and small sums of money. It is also useful to differentiate between systemic corruption, which permeates an entire government or ministry, and individual corruption, which is more isolated and sporadic. Finally, it is useful to distinguish between syndicated corruption, in which elaborate systems are devised for receiving and disseminating bribes, and nonsyndicated corruption, in which individual officials may seek or compete for bribes in an ad hoc and uncoordinated fashion.

Concurring with Wankel’s and Stachowicz-Stanusch’s claim over the last decade, “we have been witnessing a dramatic contrast between the CEO as a superhero and CEO as an antihero. The new challenge in business education is to develop responsible global leaders.” Relatively little is known, however, about how management educators can prepare future leaders to cope effectively with the challenge of leading with integrity in a multicultural space. Their recent volume Handbook of Research on Teaching Ethics in Business and Management Education is authored by a spectrum of international experts with diverse backgrounds and perspectives. It suggests directions that business educators might take to reorient higher education to transcend merely equipping people and organizations to greedily pursue their materialistic gains, gains which may have dire effects on the preponderance of people, nations, our planet, and the future. Their book is a collection of ideas and concrete solutions with regard to how morality should be taught in a global economy. In the first part, the editors present reasons why management education for integrity makes up an important challenge in an intercultural environment. This contribution is an overview of a spectrum of approaches to developing moral character in business students in this epoch of dynamic technologies and globalization.8

There is an enormous role for all types of international organizations in integrity support. Additionally, there is an undisputed role for these organizations in the process of supporting business anticorruption activities. According to the UN Global Compact conference on anticorruption in 2008, representatives of international businesses met in Bali on January 30, 2008 for a special meeting entitled Business Coalition: The United Nations Convention Against Corruption as a New Market Force. The meeting was held on the occasion of the Second Conference of State Parties to the United Nations Convention Against Corruption (UNCAC). Business and nongovernmental organizations’ representatives in Bali adopted a declaration calling on governments to establish effective anticorruption mechanisms to review the implementation of the UNCAC. This declaration forms an integral part of the report adopted by the Conference of States Parties, which forms the core of anticorruption policies.

Jointly organized by the United Nations Global Compact, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), International Chamber of Commerce, World Economic Forum, Partnering Against Corrupt Initiative (PACI) and TI, the meeting underscored the commitment of the business community to the fight against corruption. It also provided an opportunity for the business community to express its views on the role that business can play to ensure the effective implementation of the Convention.

Participants discussed the need to work toward the alignment of existing business principles with the fundamental values enshrined in the Convention, and to develop mechanisms to review companies’ compliance with the realigned business principles. They also agreed to include effective whistleblower protection, due diligence in the selection of agents and intermediaries, as well as to address facilitation payments, described as “one of the cardinal inconsistencies of existing business principles,” in their anticorruption policies and strategies.9

Stachowicz-Stanusch points out that in management philosophy, corruption and its variants have been studied across a number of disciplines, including psychology, sociology, economics, law, political science, and of course management. The current discussion about corruption in organizational studies is one of the most growing, most fertile, and perhaps, most fascinating ones. Corruption is also a construct that is multilevel and can be understood as being created and supported by social and cultural interaction. As a result, an ongoing dialogue on corruption permeates the levels of analysis and numerous research domains in organizational studies. Thus, she sees a major opportunity and necessity to look at corruption from a multilevel and multicultural perspective. Second, in the global society of the world today where organizational boundaries are becoming increasingly transparent and during the Global Crisis, which has been rooted in the unethical and corrupt behavior of large corporations, a deeper understanding of corruption, its forms, typologies, ways to increase organizational immunity, and to utilize the best practices to fight against—as well as uncover—corruption are particularly significant. This means that individuals, groups, organizations, and whole societies can be used to sustain a sense of purpose, direction, and meaning, as well as to find the best process for creating a moral framework for ethical behavior in a world of flux. Stachowicz-Stanusch provides an authoritative and comprehensive overview of organizational corruption. She contributes an essential reference tool to carry out further research on corruption in organization. Her work uncovers new theoretical insights that will inspire new questions about corruption in organization; it also changes our understanding of the phenomenon and encourages further exploration and research.10

Impediments to Integrity Promulgation and Anticorruption Practice

There is a multitude of impediments to acquiring integrity skills and to the application of anticorruption practices in organizational contexts. These impediments can result from poor integrity management, a lack of consultation and communication with employees, or a toxic management environment often unknowingly perpetrated by owners who implement a “bottom line profit” philosophy with the silent approval of corruptive practices. Impediments to communicating integrity standards and practices can be found in individual attitudes; for example, a refusal or unwillingness to communicate integrity philosophies because of personality conflicts, personal attitudes toward integrity and ethics, or a lack of motivation or dissatisfaction related to work. Sometimes, impediments beyond individual personalities may be the problem, such as language or cultural barriers,11 or ineffective or inefficient channels of communication which are needed for the implementation of integrity management training and guidance. Awareness of such impediments is the first step for educators and managers in acquiring the necessary tools for managing integrity and anticorruption approaches in an organizational context.

Integrity learning challenges us to face new experiences and enables us to develop a global mindset. Self-examination of values—personal, cultural, or organizational—can come from new experiences, from our leaving the safety of what we know and experiencing something new and different. A global mindset allows us to transcend the constraints of our experiences and belief systems and to see the world for what it really is. In order to approach the fast-paced global world, people need to work across disciplines and think holistically. Integrity and anticorruption education in organizations for an increasingly global frame of reference will require educators and managers to inculcate those in their charge with adaptability and flexibility, while balancing this with the tools of instilling ethical reasoning and a commitment to one’s own individual moral equilibrium. The process of refining these emerging global integrity competencies will be accomplished through the use of E-learning, blended learning, social media, and personalized learning environments. The process of teaching integrity in education and management is by acquiring global integrity competence benefits from such procedures as videoconferencing and collaborative blog-based methodology.

Integrity, ethics, and anticorruption in management and management education are intertwined. Ethics is the foundation for codes of conduct. It is a branch of philosophy that addresses questions of morality. These questions can be answered by adhering to a set of behavioral guidelines. A workplace, being the source of bread and butter for many, can also satisfy people’s self-actualization needs. Work often provides a raison d’être beyond the simple maintenance of a standard of living. Following ethical practices in the workplace is ultimately a personal choice. It is a choice that cannot be forced upon employees; it can only be explained and expected as a part of an overall integrity management strategy. A workplace is a cluster of individuals, and hence it is an amalgamation of attitudes and imaginations. This diversity can sometimes dilute the adherence to ethical standards of conduct. It takes the zeal of an evangelist to have the workforce imbibe ethics while facilitating the growth of the organization in a holistic way.12 Having integrity is not a state in which one is debilitated by a strict adherence to a normative code; integrity is indivisible from the growth of both individuals and the organization.

Modern organizations today do focus mainly on profitmaking. There is, however, a new trend to resurrect integrity and ethics to the workplace. Various multinational corporations today have incorporated ethics and integrity training for all their employees, from those working at the junior level to the CEO. Their employees understand what ethics are and how they can benefit the company in the long run. Many organizations, both in the public and private sectors, have designed their own workplace ethics training programs. These programs offer practical solutions to employees facing ethical dilemmas. Despite these advances in corporate training, many employees lack business ethics awareness and knowledge about their role in integrity as an organizational philosophy. These programs focus on two core messages: first, ethical dilemmas are part of the world of work; and second, there are written policies and guidance on how to work through these ethical dilemmas which are available to employees. These resources give a contextualizing framework to the employees upon which they can make ethical decisions. A rewards system for ethics and values, alongside one’s performance, is another way of ethics promotion among the employees, and is being employed by many organizations.

Organizations which promote integrity, values, and ethics have many advantages vis-à-vis other organizations. First, employees of organizations which emphasize ethical conduct experience less integrity-related stress, as they are less inclined to compromise their personal or organizational values. Secondly, in such organizations, misconduct is more often immediately reported to individual managers in the hierarchy responsible for resolving ethical misconduct issues. Thirdly, instances of misconduct are minimized and the overall level of employee satisfaction in such ethics-focused organizations is higher than in organizations without a similar emphasis. Ethical issues in the workplace can be resolved if proper procedures are in place. Upholding ethics promotes a better working environment, and at the same time, a good reputation for the business. Both of these contribute to higher work productivity and profits.13

The Role of Managers in Organizational Contexts

The terms ethical and moral are used in two ways. First the term ethical is used as a synonym for the moral quality of conduct. When, for example, we speak of people being “ethical” or “unethical,” we often mean that they habitually or intentionally act or fail to act in “good faith,” and that they consistently do, or fail to do, what is right. “Ethical” may also refer to a “class” of judgments pertaining to morality that is distinguishable from other classes such as factual, perceptual, and logical judgments; here the terms ethical and moral do not denote that which is unethical or immoral, but pertain to ethics or morality as opposed to that which is nonmoral or nonethical.14

The role of managers is to incorporate integrity and anticorruption training programs in organizational contexts into the modern communications arena using social media, such as LinkedIn, Facebook, and Twitter, real life case studies, work-study-internship examples, and blogs on integrity-related discussions. Additionally, managers and instructors can employ nonstandard approaches such as community visits to local companies with integrity-related and anticorruption-focused interviews that are carried out as a part of the training, and are later conducted during get-togethers and anticorruption integrity sessions. These interviews will in fact become organizational integrity teaching materials for real life, as interview videos, interview transcripts, and portions of analytical works, such as papers, reports, or studies.

Similarly, in European Union countries that accredit and license governmental and nonprofit agencies, students are required to study business ethics as a part of their academic curriculum, regardless of the type of degree, whether business, or management, or economics. However, the process is not very well-structured in many schools where business ethics courses are offered as electives only, and are not part of the overall integrity and ethics education program, or part of an institutionally organized instructional approach and educational philosophy.

It is highly recommended that groups of employees do one or more of the following: participate in integrity and anticorruption exercises or scenarios using role-playing or social media; create integrity and ethics discussion groups on line; conduct and record video interviews on the topic of integrity and ethics. All of these are active methods for employees to use in order to acquire a basic orientation toward and knowledge of issues related to integrity and anticorruption. Employees will get the feeling that they are part of the solution related to the challenges of integrity management. In the field of integrity in organizations, ethical policies are typically recognized as protecting individuals from ethnic and gender discrimination, sexual harassment, physical brutality, violations of confidentiality, nepotism, inhumane research, and other violations of civil and human rights. Policies addressing professional competence, such as the setting of standards for good teaching, tenure, and promotion, are not typically identified as pertaining to ethics. Both types of policies, however, typically pertain to morality in that both attempt to direct conduct toward what is “right” or conduct which is in keeping with policies pertaining to morality. Unfortunately, our tendency to restrict professional ethics to matters pertaining to the protection of civil and human rights, and to treat issues related to competence as nonethical, obscures significant professional, moral, and ethical problems and dilemmas.15

It is worth pointing out that without effective integrity and anticorruption training during college and university years many managers may be severely lacking in much-needed integrity and anticorruption competences.

Personal Values, Morals, and Workplace Ethics

As individuals are the instruments who carry the process of making ethical decisions, many factors influence this process. These may include things as far-removed as early childhood understanding of ethical behavior, through to the examples set by parents, teachers, and spiritual leaders, to the behavior of organizational leaders and formal organizational codes of conduct.

Even though most instances of ethical and integrity misconduct are motivated for positive business or corporate performance reasons (financial, productivity, efficiency, effectiveness, etc.), good people sometimes do bad things, believing that they are acting in the corporation’s best interest. However, more evidence has come out in recent years indicating that many instances of executive misbehavior have been extremely costly to the firms or institutions with which such persons were affiliated.16

A substantial amount of the research related to culture and business ethics has been done by Geert Hofstede himself or by others using one or more of his cultural dimensions of cultures, that is, the concepts of power–distance, individualism versus collectivism, uncertainty avoidance, long-term versus short term orientation, and masculinity–femininity. These have been particular to different cultures. Such studies include ethical attitudes of business managers in India, Korea, and the United States, the effects of Hofstede’s typologies on ethical decision making and on sales force performance, and many more.17

Integrity and Ethical Standards in the Workplace

Even though the issue of ethics has been discussed for centuries, it is only during the past couple of decades that the topic has come to prominence in business literature. Ethics theorists divide the field of ethics into three general categories: metaethics, normative ethics, and applied ethics. Applied ethics has become a staple of business education. The two other categories of ethics—metaethics, which ponders the likely sources of our ethical principles and their meaning, and normative ethics, which deals with the more practical task of attempting to arrive at moral standards that regulate right and wrong conduct—have largely been left underexplored by business researchers.18

Many organizations, public and private, suffer from a serious decline in integrity and ethical standards. According to Newman and Fuqua these declines are related to increased aggression and violence in the workplace, which are occurring with increased frequency.19 Universities and colleges that fail to uphold high integrity and ethical standards in teaching, and that fail to ensure policies and procedures are also followed (as well as displayed and approved), in practice, may encounter the same problems.

Ethics Rationalizations and Managerial Positions in Workplace

Ethics rationalizations are a problem for those in managerial positions. In order to understand this problem, as part of education and training, or as an actual issue in the workplace, a situation and an explanation of its conditions are needed, such as this one:

Adopted from Gentile:20

“Jonathan has a new job. Just promoted from the accounting group at headquarters, he is now the controller for a regional sales unit of a consumer electronics company. He is excited about this step up and wants to build a good relationship with his new team. However, when the quarterly numbers come due, he realizes that the next quarter’s sales are being reported early to boost bonus compensation. The group manager’s silence suggests that this sort of thing has probably happened before. Having dealt with such distortion before, Jonathan is fully aware of its potential to cause major damage. But this is his first time working with people who are creating the problem instead of those who are trying to fix it. This may seem like a mundane accounting matter. But the consequences—in terms of carrying costs, distorted forecasting, compromised ethical culture and even legal ramifications—are very serious. And except in only the most extraordinarily well-run corporations, this kind of situation can arise easily. All managers should know how to respond constructively. Indeed, learning to do so is a key piece of their professional development. Senior managers must be able to change the cultural norms that give rise to bad judgment in the first place.”

These challenges will arise frequently in modern organizations, and without proper integrity in organizational management, they can turn into company liabilities and long term problems.

Use of Case Studies in Integrity and Ethics Education and Training

The use of case studies is an established method of instructing integrity and anticorruption prevention. Case studies can either be textual or in video form. Experience has demonstrated that video learning materials are generally more effective. Regardless of the case study format, a review of the elements of the case study should be followed by employees’ discussion and role-playing scenarios moderated by the instructor. Prepared material with suitable questions and presentations by groups of employees, with an integrity and anticorruption trainer acting as a facilitator of learning, may help in organizational context competences acquisition and integrity/anticorruption skills learning. The innovative methods of synchronous knowledge could be a good means of bringing more interaction into organizational managerial integrity training and competence acquisition, by increasing discussion and participation and by making learning integrity more interactive while educating workers and managers in an organizational context.

Ethics and Integrity in Managing a Global Workplace

Managing a global workplace with significant social, ethical, cultural, and infrastructural differences from one country to another is, and has always been, a major challenge for multinational companies.21 The concept of a global business citizen is instructive. A global business citizen has been defined as “a business enterprise (and its managers) that responsibly exercises its rights and implements its duties to individuals, stakeholders and societies within and across national and cultural borders.”22 This extended conceptualization of corporate citizenship argues that responsible multinational companies are trying to wrestle in good faith with the challenges of globalization. Such a company is considered as “a global business citizen.”23

Globalization brings a number of challenges for multinational companies. Most of these challenges are related to differences of social, cultural, ethical, and infrastructural issues from one country to another. From a universal principles perspective of corporate citizenship, multinational companies should think globally and act locally by applying basic ethical values everywhere they operate.24

There are elementary steps being taken to improve compliance with legal and ethical principles, especially in organizations, both public and private. Rule-driven approaches to compliance will, at best, only have an impact on a limited number of operational areas, and will not create desired change throughout the organization. In the true spirit of capitalism, many consultants are developing and advertising ethics-based programs “for sale.” Imposition of external constraints cannot, by itself, help organizations become ideal human environments. Fundamental structural changes are necessary in order to produce moral intentions, as well as both moral reasoning and behavior within every aspect of organizational life. Organizations, by their very nature, represent complex social contexts in which structural and relational characteristics are inherently value-laden. For example, consider the often competitive nature of interests among stakeholders of an organization.

It is a rare case when a given course of action will satisfy the interests of all relevant stakeholder groups equally well. It might be expected that production staff’s concerns about working conditions, administration’s concerns about profitability, and consumers’ concerns about product safety and affordability might drive problem-solving processes in quite different directions. The functions of various organizational elements can dictate moral and ethical concerns. Therefore, diverse and inherent moral and ethical issues are embedded in the power structure of most organizations. It goes without saying that when power is unequally distributed among organizational members or groups, the emergence of moral and ethical conflicts is virtually inevitable. These are just a few examples of how the complexity of the organizational context can further complicate moral and ethical matters. The inherent limitations of mandatory integrity and ethics codes in such contexts seem clear. Organizations with genuine commitments to moral goals must actively pursue broader and more innovative approaches to building integrity and morality throughout the various dimensions of organizational structure and functioning.

The ideas of Tobias, in his articulated parallels between the thriving person and the thriving organization, have much relevance to the issues of individual and organizational morality and ethics.25 He proposed several dimensions of human adjustment and maturity that have correlates in organizational culture—initiative, discipline, and accountability, to name a few. Tobias very effectively described the inextricable linkage between characteristics of members of the organization and organizational culture. In much the same way, managers need to recognize the notion of interdependence between individual member morality and organizational morality.

Conclusion

Mandatory ethical programs are an important part of an organization’s framework. Clear guidelines established in formal ways create a baseline for expectations critical to the general well-being of the organization. Written rules in some areas (e.g., accounting) are mandated by law or by regulatory groups. Clear communication of certain principles and procedures are essential in many functional areas to meet externally- and internally imposed standards. Adherence to such standards is often so important that reporting and enforcement programs are critical components of operations.

However, the thoroughly moral organization must go well beyond principle-driven mandatory ethics programs. There are a variety of concept systems that one might use to discuss the nature of moral functioning at the organization level. Leadership topics often included moral and ethical dimensions. The key role of values and norms in organizational culture are closely related to integrity, moral, and ethical concerns and should be taught using innovative case studies approaches that use synchronous delivery methods such as role-playing, video-interviews, integrity project-participation, and intensive social media used in management education. More research needs to be conducted on the viability of synchronous competence acquisition methods and integrity competences in organization acquisition. Also, greater support is needed in using social media or similar synchronous and similar learning methods in integrity and anticorruption knowledge acquisition, by using real-life examples from organizations in order for an organization to gain integrity and anticorruption intellectual capital.

References

Andersen, J. F., & Andersen, P. A. (1987). Never smile until Christmas? Casting doubt on an old myth. Journal of Thought, 22(4), 57–61.

Carnegie Forum on Education and the Economy (1986) A nation prepared: Teachers for the 21st century. Carnegie Forum on Education and the Economy, Washington.

Goodlad, J. (1990). Teachers for our nation’s schools. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Holmes Group, (1986). Tomorrow’s teachers: A report of the Holmes Group, East Lansing, MI: Author.

Richmond, V. P., Gorham, J., & McCroskey, J. C. (1987). The relationship between immediacy behaviors and cognitive learning, in M. McLaughlin (Ed.), Communication Yearbook 10 (pp. 574–590). Beverly Hills, CA: SAGE.

Internet Sources

Kell,G. (2006). Business Against Corruption, Case Studies and Examples, UN Global Contact Office, New York, http://www.unglobalcompact.org/docs/issues_doc/7.7/BACbookFINAL.pdf, accessed 22.01.2012.

Kell, G. (2006). Business Against Corruption, Case Studies and Examples,

http://www.unglobalcompact.org/docs/issues_doc/AntiCorruption/UNGC_AntiCorruptionReporting.pdf, retrieved by the author on 28.12.2011.

Miller B.A. (2011). http://www.articlesbase.com/leadership-articles/leadership-how-important-is-integrity-in-todays-business-world-is-integrity-an-afterthought-1063750.html, accessed 27.11.2011.

www.tnv.com.pl retrieved by the author on 28.02.2011.

www.tnv.com.pl/gpmi, accessed on 13.03.2011.

http://www.unodc.org/documents/commissions/WGGOVandFiN/Thematic_Programme_on_Corruption.pdf, accessed Jan 20,2012.

http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/26/31/45019804.pdf, retrieved by the author, 02.02.2012.

http://www.unglobalcompact.org/docs/issues_doc/AntiCorruption/UNGC_AntiCorruptionReporting.pdf, accessed 28.12.2011.

http://unglobalcompact.org/, retrieved by the author on 12.11. 2011.

http://www.adb.org/Documents/Policies/Anticorruption/anticorrupt300.asp?p=antipubs, retrieved by the author on 23.01.2012.

http://www.unglobalcompact.org/docs/issues_doc/AntiCorruption/Bali_Business_Declaration.pdf, accessed 01.09.2012.

http://www.amazon.com/gp/product1613505108/ref; retrieved on 20.01. 2012

http://www.adb.org/Documents/Policies/Anticorruption/anticorrupt300.asp?p=antipubs, retreved by the author on 14.02.2012.

http://amazon.com/gp/product1613505108, accessed on 02.02. 2012.

Key Terms

Integrity—the quality of being honest and having strong moral principles that you refuse to change, the quality of being whole and complete.

Anticorruption—institutional and noninstitutional actions to prevent and eradicate corruption in an organizational context and public spheres.

Ethics—the study of what is morally right and what is not.

Management education—in all business and organizations, regardless of size, including private, not for profit, public, and mixed ownership this is the act of getting people together to accomplish desired goals and objectives using available resources efficiently and effectively following ethical guidelines, striving to create integrity, and sustainable organizations caring for their communities as much as possible.

Impediment—something that makes progress, movement, or achieving something difficult or impossible.

Study Questions

1. Discuss integrity and anticorruption actions in an organizational context by showing innovative methods of dealing with new challenges and by suggesting the most effective approaches in an organizational context.

2. How can business strengthen the process of building an integrity-proof, corruption-free organization of the future?

3. Should integrity in an organizational setting be a part of executive learning/future training as an aim for all organizations? If yes , how can this be achieved in your industry ?

Further Reading—Books

Carter, C. (2007). Business ethics as practice: Representation, reflexivity and performance. Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

Cloke, K. (2002). The end of management and the rise of organizational democracy. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Cohen, W. (2008). A class with Drucker: The lost lessons of the world’s greatest management teacher. New York, NY: AMACOM/ American Management Association.

Conrad, B. K. (2003). The Tao of legal ethics: Integrating the rules of legal ethics with codes of personal morals and integrity. Columbia, SC: H/S Publications in affiliation with Ment-A-Tech Publications.

Dealy, M. D. (2007). Managing by accountability: What every leader needs to know about responsibility, integrity-and results. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Finser, T. M. (2007). Organizational integrity: How to apply the wisdom of the body to develop healthy organizations. Great Barrington, MA: Steiner Books.

Frederickson, H. G., & Ghere, R. K. (Eds.). (2005). Ethics in public management. Armonk, NY : M. E. Sharpe.

Garsten, C., & Hernes, T. (Ed.). (2009). Ethical dilemmas in management. London, UK; New York, NY: Routledge.

Garten, J. E. (2002). The politics of fortune: A new agenda for business leaders. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Jackson, K. T. (2004). Building reputational capital: Strategies for integrity and fair play that improve the bottom line. Oxford, UK; New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Johnson, L. (2003). Absolute honesty: Building a corporate culture that values straight talk and rewards integrity. New York, NY: AMACOM, American Management Association.

Kolthoff, E. (2007). Ethics and new public management: Empirical research into the effects of businesslike government on ethics and integrity. Den Haag, Netherlands: Boom Juridische.

Langlais, K. J. (1997). Managing with integrity for long term care: The key to success for building stability in staffing. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

LeClair, D. T. (1998). Integrity management: A guide to managing legal and ethical issues in the workplace. Tampa, FL: University of Tampa Press.

Maak ,T., & Pless, N. M. (Eds.). (2006). Responsible leadership in business. New York, NY: Routledge.

Menzel, D. C. (2007). Ethics management for public administrators: Building organizations of integrity. Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe.

Murray, T. H., & Johnston, J. (EdS.). (2010). Trust and integrity in biomedical research: The case of financial conflicts of interest. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Neef, D. (2003) Managing corporate reputation and risk: Developing a strategic approach to corporate integrity using knowledge management. Amsterdam; Boston, MA: Elsevier/Butterworth-Heinemann.

Perry, J. L. (Ed.). (2009). The Jossey-Bass reader on nonprofit and public leadership. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Petrick, J. A. (1997). Management ethics: Integrity at work. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Robbins, D. A. (1998). Managed care on trial: Recapturing trust, integrity, and accountability in healthcare. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Siddiqui, M. (2005). Corporate soul: The monk within the manager. New Delhi, India; Thousand Oaks, CA: Response Books.

Sonnenberg, F. K. (1994). Managing with a conscience: How to improve performance through integrity, trust, and commitment. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Spinello, R. A. (2003). CyberEthics: Morality and law in cyberspace. Boston, MA: Jones and Bartlett Publishers.

Srivastva, S. & associates. (1988). Executive integrity: The search for high human values in organizational life. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Storey, J. (Ed.). (2011). Leadership in organizations: Current issues and key trends. New York, NY: Routledge.

Traer, R. (2009). Doing environmental ethics. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Westra, L., & Lemons, J. (Eds.). (1995). Perspectives on ecological integrity. Dordrecht; Boston, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Whitton, H. (2005). Managing conflict of interest in the public sector: A toolkit. Paris, France: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Further Reading—Journals

Dobni, D., Ritchie, J. R. B., & Zerbe, W. (2000). Organizational values: The inside view of service productivity. Journal of Business Research 47, 91–107.

Ferrell, L. (2004). Successful programs for teaching business ethics. Presentation at the Teaching Business Ethics Conference, Boulder, CO, July 21–23.

Fritzsche, D. J. (1987). Marketing/business ethics: A review of the empirical research. Business and Professional Ethics Journal 6, 65–79.

Gowen, C. R., III, Hanna, N., Jacobs, L. W., Keys, D. E., & Weiss, D. E. (1996). Integrating business ethics into a graduate program. Journal of Business Ethics 15, 671–679.

Kelly, M. (2002). It’s a heckuva time to be dropping business ethics courses. Business Ethics 16(5 and 6), 17–18.

McCabe, D. L., & Treviño, L. K. (1993). Academic dishonesty: Honor codes and other contextual influences. Journal of Higher Education 64(5), 522–538.

Reidenbach, R. E., & Robin D. P. (1991). A conceptual model of corporate moral development. Journal of Business Ethics 10, 273–284.

Swanson, D. L. (2004). The buck stops here: Why universities must reclaim business ethics education. Journal of Academic Ethics 2(1), 1–19.

Treviño, L. K., & McCabe, D. (1994) Meta-learning about business ethics building honorable business school communities. Journal of Business Ethics 13, 405–416.

Verschoor, C. C. (1998). Corporations financial performance and its commitment to ethics. Journal of Business Ethics 17, 1509–1516.

Woo, C. Y. (2003). Personally responsible. BizEd (May/June), 22–27.

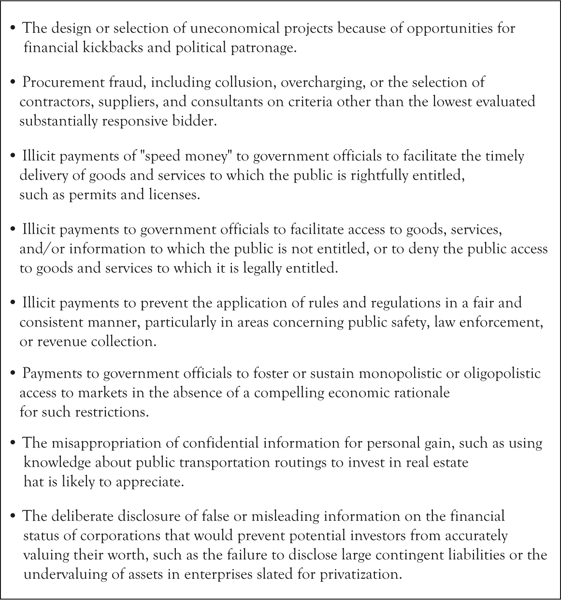

Figure 4.1. An illustrative list of corrupt behaviors.

Note: Courtesy of the Asian Development Bank, 2012.