A Consulting Model that Clarifies Core Values and Promotes Greater Organizational Integrity

Introduction

Humanistic organizations are concerned with the kinds of meaning that will sustain it for the long term. The increasing need for organizations to act with integrity is imperative given the documented decline in ethical culture and behavior.1 The kinds of meaning that are most important to an entity are ultimately acted upon by the entity—whether the actions are beyond goals of profit or focused on profitability shaped by business values.2 This chapter explores how humanistic organizations are those that act beyond a goal of profitability and have a vision that generates clarity during times of turbulence or flourishing.

This case study of three different organizations provided the opportunity to observe, document, and analyze 4 months of consulting with each entity. Each organization is classified as an SME. The consulting engagements centered on the organizations identifying and defining their core values and defining their vision statement.

Core values acted out by an entity represent expressions of integrity which in turn make up the kinds of meaning that are most important to the entity. Integrity, a wholeness or completeness in organizations,3 is the result of actions based on a clear set of values. By having a set of core values that act as organizing principles, the organization attains clarity in the decisions it makes down to the routine practices of everyday operations.4 How the organization acts out its core values is primarily based on the idea that they are structured in an ordinal fashion. That is, a certain core value or set of values are prioritized over others. It is this ordinal nature of the entity’s core values that provide a structure of meaning for the purpose of seeking enduring success.

Diverse Organizations with Similar Needs

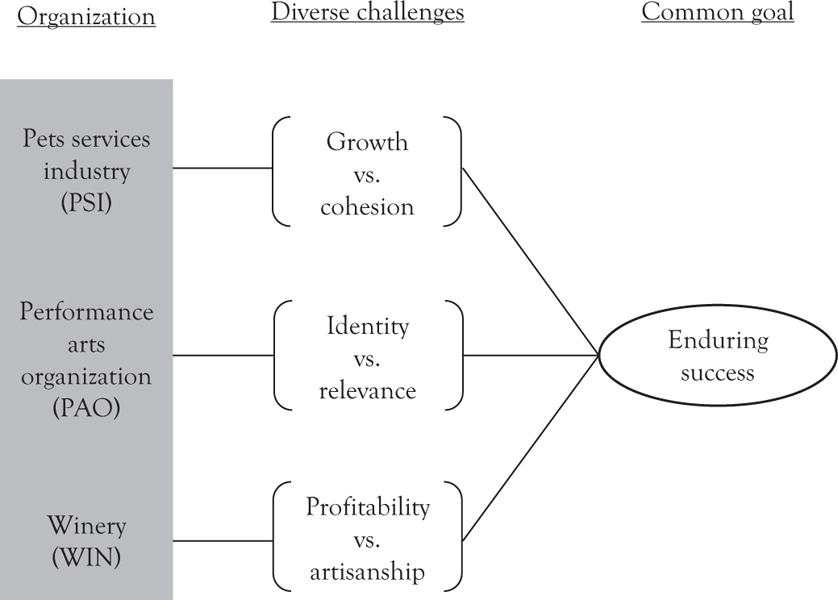

There are a variety of reasons as to why an organization will seek out to define their core values and vision. Five reasons are: change in organizational status, change in top management, change in profitability, change in the competitive environment, and initiation of change.5 For this case study, each organization wanted a degree of clarity on their reason for being. They wanted what Collins and Porras superbly expressed as attaining “enduring success.”6 With the possibility of enduring success, however, each organization faced different challenges prompting the need for clarity and purpose.

Serving Pets and Their People…in Unique Ways

The Pets Services Industry business (PSI) serviced client needs for pets. In speaking with the owner over a series of meetings, he came to the conclusion that he wanted his business to maintain the dynamic culture of his management team, yet still grow the business. He had successfully foiled franchise competitors over the years and was on the way to developing the largest specific pet service business in the state. What continually concerned the owner in spite of growth and healthy profits, however, was the desire to maintain growth but not at the expense of losing the close connection between employees. A reasonable and common challenge faced by nearly all successful SMEs as they move beyond the “small” or even “medium” definition. Bureaucracy emerges which, in the eyes of the leadership team, threatens the closely shared identity of the business. Probing more through inquiries, the owner revealed that there was a lack of clarity in deciding what new ventures to pursue, but also on how that would impact the business. Enduring success is a goal, but the immediate challenge was clarity on how to manage growth.

Be, Sing, Become…..IMPACT

The Performance Arts Organization (PAO) earned a reputation of excellence, but at the same time found itself to be in stasis with respect to patron and audience growth. Like most performance organizations and nonprofits, members participate, whether paid or volunteer, to be what Peter Drucker coined “human change-agents.”7 The artistic director, board members, and nonmembers proposed that the chief challenge of the ensemble was brand identity and needed to be revitalized. As such, the quick fix would be to create a new logo or a new brand and advertise it. While such efforts may attain some returns, they are short lived. Most importantly, they do not address the real need of seeking and sustaining the kinds of meaning that will provide direction. Upon discussing with the artistic director and board president, the real issue surfaced. We discovered that the organization didn’t have an identity crisis, but instead had not fully identified or articulated what was most important in all matters of performance, administration, rehearsal, and fund-raising. The organization lacked clarity of vision in fulfilling what seemed to be an obvious reason for being: to perform, more than a redesign of brand or name was in need.

Wine for the People

Winemaking is an artesian process which is rich with practices characterized by tacit knowledge.8 Such is the case with the winery. Previous consulting services yielded the identification of indirect costs for the winery (WC) thereby providing a frame of reference toward managing costs but not at the expense of compromising quality. Upon identifying indirect costs for the client, he found there was a basis to improving profitability, and perhaps the first time in 5 years. Yet from working with the owner, the winery needed to establish focus in seeking profitability balanced with artisanship.

Note that each organization faces a different challenge: one of maintaining identity while attaining growth; one of finding clarity of vision and being relevant to patrons; and one that needs to preserve their way of winemaking but not at the expense of pursuing only profit. All are challenges to the kinds of meaning that will sustain each entity. Why an organization preserves and draws from their values is a manifestation of integrity and characteristic of practices that set the foundation for a humanistic management.

Integrity in Organizations

Each consulting engagement focused on the organization identifying their core values and vision. As noted above, the entities sought enduring success and also clarity in confronting each of their unique challenges (see Figure 6.1). In the process of consulting with each entity, the pattern of integrity expressed through core values emerged as a salient pattern.

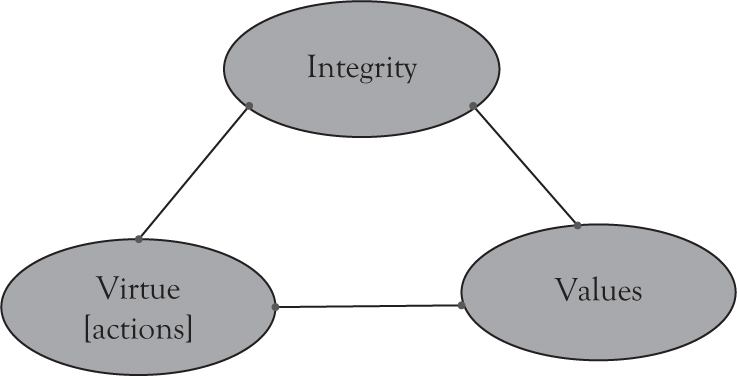

As a topic, “Integrity” has yielded research ranging from trust in organizations9 to a resource that is managed.10 Importantly, integrity has been defined as a wholeness, soundness, or completeness in the organizational context11 and within the individual context.12 All perspectives, however, differ on how integrity is expressed through actions leading to integrity being labeled as a virtue or implied as a type of business character.13 Virtue, though connected to integrity, should be examined separately, yet part of the wholeness that makes up integrity.

Recently, the concept of virtue ethics has emerged as a priority topic in management journals. Virtue has been identified as a basis of consistent actions or habits yielding excellence over time. Alasdair MacIntyre describes virtue as “practices” developed over time that hold intrinsic value.14 Managing through a virtue context contributes to contexts where employee attitudes and behaviors contribute to a positive environment or mitigate negative circumstances.15 In summary, virtues contribute to human flourishing16 and a basis for action during challenging or routine times.17

Identifying distinctions between virtue ethics and the characteristics of integrity is essential toward understanding how an organization acts through its daily practices as manifesting integrity or falling short of acting with integrity. Specifically, the foundations for the existence of integrity—a wholeness and completeness—within an organization are dependent on why the mundane pattern of actions (the virtues) resonate or do not resonate of integrity.18 Core values serve as guiding principles since individuals act out on what is important to them.19 In other words, a type of end, or telos, is essential toward linking behavior and actions (virtues) to integrity.20 Organizations are driven by purpose that shape how work is accomplished.21 Values serve toward ends, purpose, mission, and vision. Virtue, integrity, and values provide a trinity of concepts that are interrelated. Figure 6.2 exhibits the attributes of each defined variable of virtue, integrity, and values.

Expressions of Integrity in Organizations

Given the above patterns, integrity is expressed via acting out a set of core values. Integrity is a wholeness and is derived by actions that provide a completeness.22 Values are organizing principles that serve as signposts to why decisions are made or how mundane work practices are acted out. The connection between what is valued by the organization—core values—and acting out such core values represents expressions of integrity.

What determines the basis for a decision or action? If values are instinctive drives then such drives work competitively toward a point of balance.23 Pirson and Lawrence suggest that individual actions are fundamentally shaped by four drives: the drive to acquire, the drive to bond, the drive to comprehend, and the drive to defend.24 The four drives, however, are independent of each other and thus, inherently competitive toward each other as are instincts. Each drive will be more important than the other depending on the circumstance the individual faces. The problem with instincts or the four drives is that obeying them may be like obeying people. We tend not to if given a choice.25

Evidence emerging through the consulting engagements with the three SMEs suggests an alternate vantage point. While there is clearly a manifestation of the four drives in organizations, the competitiveness of each drive suggests that integrity is not a structural wholeness but dependent on circumstances and personal preference. In contrast, the consulting engagements provided evidence that suggests an ordinal structure to the core values identified and acted upon by members. Participants acted on a set of organizing principles.26 This ordinal structure resonates of Augustinian thought as an “order of loves.”27 For purposes of this case study, evidence suggests that each organization leaned on certain core values placed above the rest but not at the expense of the other values.

The Consulting Engagements

Consulting offers a rich outlet to study, observe, and validate findings of how organizations accomplish their purpose. And since the consulting engagement is for the purpose of serving a client’s needs, it also serves toward the application of action research.28 Working as a perceived colleague, yet being a third party, consulting as action research allows for observations on how each entity developed their core values.29 The consulting engagements also provided the best of what action research provides: a value outcome for the client that is applicable and relevant to business.

The process used for developing the core values for each entity was based on Appreciative Inquiry.30 My approach to extracting out a set of core values and vision statement is essentially a synthesis of visioning and purpose;31 appreciative inquiry in bringing out the “best of what is” in the organization;32 and the researcher–client relationship where both work in developing solutions. Table 6.1 displays the characteristics of each business in the case study along with other case study components.

Table 6.1. Organization Characteristics and Consulting Data Methods*

|

Organization characteristics |

Core value consulting sessions |

Post session consulting interviews |

Data methods |

|

Pet Services Industry Business (PSI) Employees—40 Type: Profit |

4 sessions 4 hours each 5 attendees; management team and owner |

8 sessions 1 hour each Owner |

Pattern Matching (Cao 2007; Yin 1994; Cresswell 1998) Data Trees (Jonsen & Jehn 2009 ) Regular review and confirmation/corrections by participants (Vries, Manfred, & Miller 1987; Yin, 1994; Cresswell 1998 ) |

|

Performing Arts Organization (PAO) Members—65 Type: Non-Profit |

4 sessions 4 hours each 15 attendees; board, non-board, and artistic director |

8 sessions 1 hour each Artistic Director |

Pattern Matching (Cao 2007; Yin 1994; Cresswell 1998) Data Trees (Jonsen & Jehn 2009 ) Regular review and confirmation/corrections by participants (Vries, Manfred, & Miller 1987; Yin, 1994; Cresswell 1998 ) |

|

Winery (WIN) Owner and 3 part-time employees. Type: Artisan/Family |

3 sessions 3 hours each 1 attendee; owner |

3 sessions 2 hours each Owner |

Pattern Matching (Cao 2007; Yin 1994; Cresswell 1998) Data Trees (Jonsen & Jehn 2009 ) Regular review/corrections by owner (Vries, Manfred, & Miller 1987; Yin, 1994; Cresswell 1998 ) |

*All entities had at least 3 consulting sessions followed by post consulting interviews. Applied pattern matching, data trees, and post interviews to interpret and confirm results.

Integrity in Action: Core Value Sessions

Sessions with the entities were characterized by long hours of addressing questions and arranging data. The four questions used for each of the core values sessions are as follows:

1. Think of a time in your entire experience with your organization when you have felt most excited, most engaged, and most alive. What were the forces and factors that made it a great experience? What was it about you, others, and your organization that made it a peak experience for you?

2. What do you value most about yourself, your work, and your organization?

3. What are your organization’s best practices (ways of management, approaches, traditions)?

4. What is the core factor that “gives life” to your organization?33

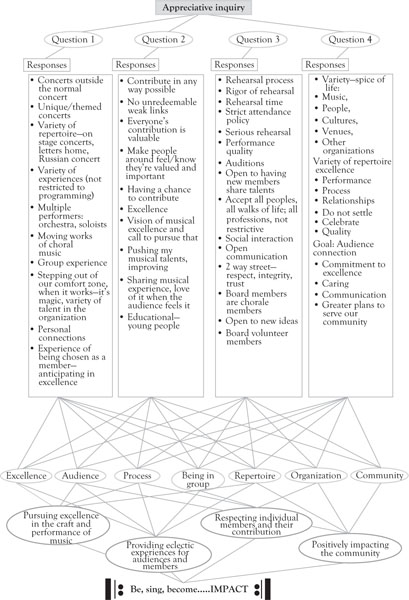

Each question is designed to solicit responses that focus on “the best of what is” within the organization. Participants work together toward a common end, but not through a process of “problem analysis” that focuses on what is wrong. Rather, the approach is to focus on the inherent strengths and a tacit understanding of what is most important to the participants. Table 6.2 outlines session responses and how the volume of responses trickles down to a set of core values and vision.

Table 6.2. Responses by Session from Themes to Core Values to Vision Statements*

|

PSI |

PAO |

WIN |

|

|

Session 1 Responses |

42 Responses |

147 Responses |

12 Responses |

|

Session 2 Deriving Values |

Four Themes Work Environment People and Servant Leader Customer Service Pet Compassion |

Seven Themes Excellence in performance Audience interaction Process-rehearsal Being part of the group Variety of repertoire Organization/Board Community |

Six Themes Removing snobbery from wine Educating customers Urban winery in a community Making visitors feel like family Reward of having people enjoy the wine A crafted good for others |

|

Session 3 Finalizing Values |

Seven Core Values Passion for pets Respect for others Accountability Service Excellence-customer driven Integrity FUN work environment |

Four Core Values Pursuing excellence in the craft and performance of music Providing eclectic experiences for audiences Respecting individual members and their contribution Positively impacting the community |

Three Core Values Education about wine and its virtues Neighborhood family winery where visitors are welcome like family Artisanship of a crafted good from practices handed down the family |

|

Session 4 Establishing Vision and Purpose |

Serving pets and their people, in unique ways |

Be, Sing, Become….IMPACT! |

Wine for the people |

*All entities, PSI (Pet Services Industry), PAO (Performing Arts Organization), and WIN (Winery) developed themes from the early consulting sessions that eventually emerged as core values. From core values, a concise vision statement was developed. Note that several responses by each entity filtered down to essential core values and a concise vision statement.

The first question always prompts the most enthusiastic of responses since reflection on a peak experience brings up memories of how excellent work can be accomplished. In each situation, many of the responses from the first question ultimately end up as a core value, an ideal within a core value, or in support of a core value. As an example of using pattern matching and theme analysis through tree diagrams, Figure 6.1 illustrates for the PAO the process of questions to final core values in Figure 6.3.34

A consistent set of responses suggested what was most important to participants in the organization. An organization’s consistency to its values and aspirations is critical toward expressing integrity.35 This also corresponded with the organization’s general goals or approaches to conducting business since what is most important is acted upon.

A feeling of disorientation, rather than focus, was experienced by the participants. This disorientation was important for each of the sessions. Participants initially perceived their responses as having limited correlation yet recognized that organizational life offered much in terms of current and potential fulfillment. Experiencing dissonance in the process represents a form of sense-making that leads to a plausible set of core values.36 The sense-making process that took place during the sessions reflects an expression of integrity in the organization for three reasons: First, by wrestling with the questions and trying to establish themes and patterns, participants regularly sought out cues and retrospectively created meaning.37 This type of behavior is necessary at the organizational level under circumstances of conducting routine business. It suggests a bridge between behavior and character,38 whether circumstances are mundane or extraordinary.39 The problem faced by the participants was equivocality, not the need for more information.40 When faced by a variety of outcomes, guidance toward establishing priorities is essential toward defining what matters most. This represents an expression of integrity: the acting out of core values given a consistent history of doing so (retrospectively answering the questions).41

Second, the identity of each participant was challenged in the process of extracting core values out of several responses.42 The end (telos) of defining core values was plausible to participants rather than a “right” answer to be achieved. It was a process of sharing narratives where personal narratives represent expressions of integrity.43 The appreciative inquiry process required individuals to negotiate their personal narratives to those of the group and to those of the organization. In this way, participants did “act out” what was most important to them and in the process aligned their values with that of the organization.44

Third, the sessions were social and led toward plausible outcomes.45 Participants had to work with others and come to an agreement on what constituted the core values of their organization. It was one thing for individuals to tacitly know and have a general sense of what was most important to them as individuals and as groups. It was quite another to concretely define the values. The conduct of the participants was contingent on the conduct of others in the group. That type of interrelationship of conduct expresses the soundness and integrity of the organization.46 As an expression of integrity, the process challenged participants to solidify the structural components of the organization’s core values and vision as a team.

For the winery, I served as facilitator/guide but also the social dynamic of focusing on cues since the owner was the sole participant. The process, however, worked the same way as with the other entities. His sense-making was no different since I was available as both the facilitator and the collaborator in the process of developing a vision of Wine for the people.

Using the approach of asking “WHY” five times about why it is important what the organization provides, there was first a general sense of the disorientation experienced in defining a vision.47 After many iterations in the process, a rewritten vision statement would strike an immediate response of agreement. The group would sleep on the vision statement and days later would still represent what the entity is all about.

To summarize, the process of developing core values and vision was an occasion for sense-making.48 It was also an expression of integrity because what people tacitly knew was challenged. Participants needed to transform imprecise values into concrete values while working out that process with others. Since integrity is a wholeness the core values and vision process as sense-making challenges the underlying assumption of what people hold to be important and to act on what is important.49

Integrity in Action: Post-Session Consulting Interviews with Owners and Directors

As part of the consulting engagement, I met regularly with the owners and director for each organization. That time provided the owners and director to reflect on how the established core values were “holding up” in mundane everyday work. Habits, particularly in the mundane or remarkable, eventually shine as virtues or vices, either of which sustains the completeness of integrity or undermine it.50

During the time of post-session interviews I had with each organization spanning two months, the following outcomes were apparent and represent some of the practical outcomes of establishing a set of core values and vision.

1. Clarity on strategic direction

• The direction of the entity had greater clarity and focus.

• Distinctions between distractions versus opportunities emerged.

• Clear strategies in tandem with improved operations.

2. Acting deliberately

• There was a point of reference and reason for acting and deciding.

• Priorities for operations had a rationale since they are based on values.

• Cohesion within teams and groups based on agreed values.

3. Core values crystalize

• Issues surfaced that challenged the relevance of the core values.

• Internal conflicts require management and employees to apply what is most important in the business—the agreed upon core values.

• Perceived conflicts deflated during the core values session since participants realized others held similar points of view and opinions.

Acting out the core values was an expression of integrity and completeness in the organization. The actions of the owners and director indicate that they are concerned with the kind of meanings that will yield enduring success for the organization. Since human activity and creativity creates a world of things, values also provide vitality to routines and processes.51

In the interest of space, the following are only samples of events for all three organizations. For the PSI organization, the first notable difference was the clarity the organization had about the direction of the business. The owner (Ben) comments:

“I’ve been wondering, actually all of us, about what really is the purpose of our work? We knew it was important, but identifying it and making it a continual pursuit as a vision statement and core values is great. I can’t believe how clear a direction and purpose we have. In fact, we’re now working on a new marketing campaign. One based on the direction and values that are most important to us and our customers.”

Another instance was a challenge to the core values set by the group and the continual process of sense-making. In this situation, it was a simmering conflict between two managers. The owner continues:

“Will it keep us from growing? I wonder if this type of thing will keep us from growing into a world class company. Can we attain that status or do we need perfect employees?”

As owner and leader, he wants it to be a place where employees have fulfilling careers. He also wonders if he is at fault, another component of sense-making where one questions their identity.52 When I followed up a week later on the conflict he responded:

“They’re doing better. We agreed that respect for our team and accountability were at stake. If we create a problem then we need to create a solution. And, the root of the issue was just a lack of respect one had over the other.”

Overcoming a challenge to the core values creates cohesiveness of the assumptions and beliefs of the entity’s culture.53

One final event stands as an exemplar on Ben’s approach to conducting business. In one interview he said that a competitor approached him and asked if he would be interested in buying 25% of his client list. Surprised, Ben asked why. The competitor (smaller than Ben’s operation which is three times larger) said his truck used on the job needed major repairs and he was out of operating cash. He also didn’t want to borrow additional funds. Ben’s response:

“It’s the guy’s bread and butter. I couldn’t take away or even consider buying that list and further create a bigger hole for him. That could send him out of business, just to fix the truck and have him try to recoup the costs and customers in the future. It wasn’t right.”

He acted consistently with his values and the values the team defined. Some items are worth noting about this incident: First, Ben exhibited what Michael Porter in Competitive Advantage calls being a good competitor,54 one that creates a good competitive landscape where all organizations can thrive rather than one that seeks out predatory approaches and diminishes the value of the market and ultimately to the consumer. Second, Ben exhibited integrity out of habit. His order of values is set and he acts on them by habit yielding excellence. He acted based on an emerging ordinal structure of the core values. His habits cultivated virtue, which further strengthens the completeness of integrity.55 Third, by virtue of Ben’s actions, we find that he is concerned with the kinds of meaning that will sustain the business and the competitive landscape.56

For the PAO, a positive environment for processes and board meetings emerged where core values mitigated years of board latent conflict.

“Honoring people for who they are is that vital part of the process. I mean, the process can only be as good if people know they are respected, that what they have to contribute is important, that people enjoy being part of the chorale, that I respect them and want their best and of who they are. Because people have dignity as humans, that process is vibrant and has life. It’s full of life.

Take orchestras—some are cogs in the wheel. They are equipment, supplies. They [musicians] are sour and well don’t feel appreciated. We are not like that. What people contribute is vitally important and they know it.”

Here, the artistic director, Mark, enacts the core values as one would a code of ethics, but it is more than ethics that are at stake. The positive climate of the ensemble is maintained.57 Acting out the core value created greater cohesiveness in the ensemble.

Another instance on clarity follows:

“One thing I really appreciated about your process is that it diffused a lot of conflict in the board. Our meetings are so rife and dysfunctional. Members would sit and not comment during meetings even after our gracious president asked, any thoughts. Then out of nowhere, a member flares out with a comment, then sits silently and stews. This was essentially our way of having meetings.

Your process changed all of that. When the board members saw that everyone agreed on issues, they realized they were fighting based on misconceived ideas and assumptions. When they realized that so and so is thinking and thought along the same line as me, it was, ‘Wow. I don’t have to fight that person.’ The meetings now have changed, people comment, interact because there is a common agreement that what they all value, they actually valued prior to the meeting. It took the process to discover that assumptions held eroded the moral integrity of interacting in the meetings and pursuing common goals for the good of the choir.”

The appreciative inquiry process alone reduced latent conflict and encouraged closer collaborative meetings by improving their language and communication.58 In this instance, an order of values emerges where respect for individuals is a priority. This contributes to a closer connection to the organization as a whole.59

Finally, the winery owner exhibited qualities of his established core values for the business. His artisanship coupled with his desire to remove the snobbery associated with wine (to educate) permeates how he conducts business.

In all of our interviews, when Peter speaks of making wine he trails off in various directions. His knowledge of making wine is highly tacit, which accounts for the “rabbit trails.” But when working with him on the process of making wine, his desire to educate people about the realities of the effort and care taken into the process override stale explanations. On one occasion I had the privilege of observing how he blended one of the winery’s signature labels. Peter continues:

“Have a seat. Blending today will be a challenge since a restaurant downtown needs more of the label (wine) before scheduled. This will be interesting. You need two glasses so you can sample. This barrel (at the end of a row of barrels) has been sitting a couple of years, it should do for what we need. [Sniffs, looks, sniffs a sample]. This is important, if the blend doesn’t work, the label is not there…and if it is not there, what’s the point in making it? You know? [Explicative] this has to be good….it helps business, but most of all, I want people to enjoy what I’ve made.”

Making wine is not just smashing grapes. Peter’s approach was anything but precise, but it was qualitatively superior to what a mechanized approach could produce—at least for the very way and means as to how it was produced. This is important to realize since how Peter conducts business is reflective of how he makes wine and that improves my understanding about how certain entities conduct business.60 For Peter, the lengthy process of making wine is how he conducts business, and this poses a challenge to attaining and sustaining profitability. His current status shows emerging profitability, but he also wrestles to balance that with the intent of the winery—to educate others on wine and preserve the way of making wine. There is excellence in practices, but there is also the personal integrity acting out the enduring tenets he originally set out when he opened his business. The profitability is testimony to his hard work and craft and yet, Peter still unifies his individual interests to what is good for the community.61 His primary value is to educate the public: wine for the people. He is concerned with the kinds of meaning that contribute toward wine as being a part of the experience his customers feel when they have a glass of his artisanship.

Ending Comments

In each area of consulting, the core value sessions and the interview sessions, a consistent pattern of acting out values that express a completeness of integrity is evident. During the core values sessions, participants found their general sense of identity and what they believed to be challenged. The sense-making process was an occasion to challenge their values and act out with integrity. For organizations to develop integrity, the values of persons or entities must be challenged. This suggests that there not be permanent solutions to the intrinsic tensions organizations face. Rather, it is confronting tensions and challenges that build up virtue [actions] based on values that strengthen integrity.62

Key Terms

Core values—the enduring tenets of an organization, the most important values to the organization. They serve to guide in decision making.

Appreciative inquiry—the practice of focusing on what the organization does well rather than focusing on the negative or weaknesses.

Sense-making—making sense of situations that are vague by searching for plausible solutions or outcomes.

Study Questions

1. The three organizations in the chapter each had a set of challenges toward enduring success. What are your organization’s challenges that serve toward your focusing on enduring success?

2. What shapes the decision-making process for major decisions and for routine decisions? Is what shapes the decision different in each? If so, how?

3. What constitutes virtue—actions and practices—in your organization?

4. What do you think are the core values in your organization? Would they also be held by employees?

5. From the case studies in the chapter, virtue and values work in tandem in building integrity. What does this process look like in your organization? Why?

6. Without core values, what serves as guiding your organization toward enduring success?

7. What types of sense-making are you engaged in, or your organization, where a set of core values would greatly help and thereby build the integrity of your organization?

Further Reading

For Nonprofits Working on Vision and Strategy

Collins, J., (2005). Good to great: The social sectors. Boulder, CO: Jim Collins.

On Organizational Culture and Management Perspectives

Schein, E. H. (1992). Organizational culture and leadership (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Maslow, A. H. (1998). Maslow on management. Stephens, D. C., & Heil, G.(Eds.). New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

For Insights on Future Organization Design and Practice

Chodhury, S. (2003). Organization 21C: Someday all organizations will lead this way. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Financial Times Prentice-Hall.

On Action Research and Appreciative Inquiry

Reason, P., & Bradbury, H. (2001). Handbook of action research: Participative inquiry and practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.