Business process change

Keywords

Information technology (IT); Lean; Levels; Six Sigma; Systems; Value chain

This chapter provides a brief history of corporate business process change initiatives. Individuals working in one tradition, whether business process reengineering (BPR), Six Sigma, or enterprise resource planning (ERP), often imagine that their perspective is the only one, or the correct one. We want to provide managers with several different perspectives on business process change to give everyone an idea of the range of techniques and methodologies available today. At the same time we will define some of the key terms that will be used throughout the remainder of the book.

People have always worked at improving processes. Some archeologists find it useful to organize their understanding of early human cultural development by classifying the techniques and processes that potters used to create their wares. In essence, potters gradually refined the pot-making process, creating better products, while probably also learning how to make them faster and cheaper.

The Industrial Revolution that began in the late 18th century led to factories and managers who focused considerable energy on the organization of manufacturing processes. Any history of industrial development will recount numerous stories of entrepreneurs who changed processes and revolutionized an industry. In the introduction we mentioned how Henry Ford created a new manufacturing process and revolutionized the way automobiles were assembled. He did that in 1903.

In 1911, soon after Henry Ford launched the Ford Motor Company, another American, Frederick Winslow Taylor, published a seminal book: Principles of Scientific Management. Taylor sought to capture some of the key ideas that good managers used to improve processes. He argued for simplification, for time studies, for systematic experimentation to identify the best way of performing a task, and for control systems that measured and rewarded output. Taylor’s book became an international bestseller, and many would regard him as the father of operations research, a branch of engineering that seeks to create efficient and consistent processes. From 1911 on, managers have sought ways to be more systematic in their approaches to process change.

New technologies have often led to new business processes. The introduction of the train, the automobile, the radio, the telephone, and television, has each led to new and improved business processes. Since the end of World War II computers and software systems have provided a major source of new efficiencies.

Two recent developments in management theory deserve special attention. One was the popularization of systems thinking, and the other was the formalization of the idea of a value chain.

Organizations as Systems

Many different trends led to the growing focus on systems that began in the 1960s. Some derived from operations research and studies of control systems. Some resulted from the emphasis on systems current in the computer community. Today’s emphasis on systems also arose out of contemporary work in biology and the social sciences. At the same time, however, many management theorists have contributed to the systems perspective. One thinks of earlier writers like Ludwig von Bertalanffy, Stafford Beer, and Jay W. Forrester and more recent management theorists like John D. Sterman and Peter M. Senge.

In essence, the systems perspective emphasizes that everything is connected to everything else and that it is often worthwhile to model businesses and processes in terms of flows and feedback loops. A simple systems diagram is shown in Figure 1.1.

The idea of treating a business as a system is so simple, especially today when it is so commonplace, that it is hard for some to understand how important the idea really is. Systems thinking stresses linkages and relationships and flows. It emphasizes that any given employee or unit or activity is part of a larger entity and that ultimately those entities, working together, are justified by the results they produce.

To make all this a bit more concrete, consider how it is applied to business processes in the work of Michael E. Porter.

Systems and Value Chains

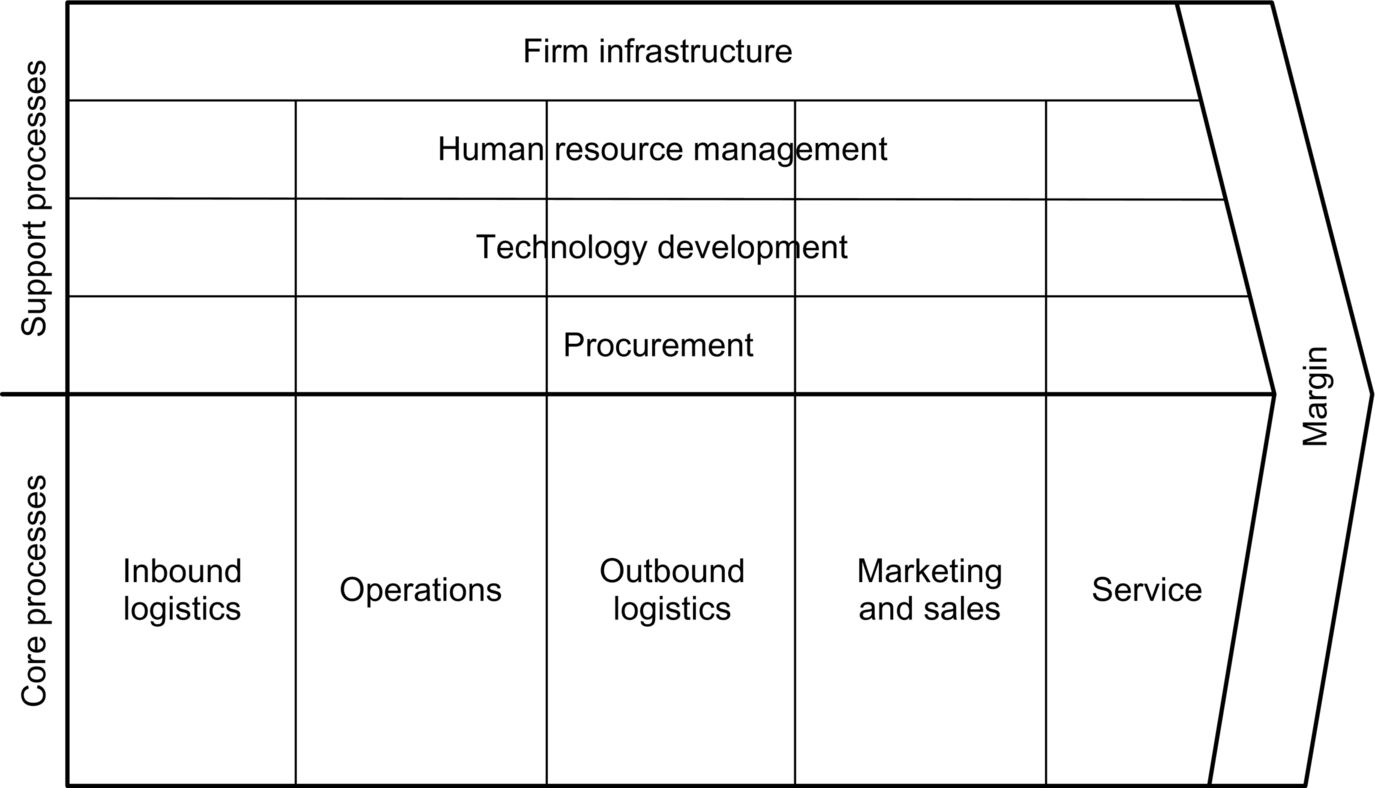

The groundwork for the current emphasis on comprehensive business processes was laid by Michael Porter in his 1985 book, Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance. Porter is probably best known for his earlier book, Competitive Strategy, published in 1980, but it is in Competitive Advantage that he lays out his concept of a value chain—a comprehensive collection of all the activities that are performed to design, produce, market, deliver, and support a product line. Figure 1.2 shows the diagram that Porter has used on several occasions to illustrate a generic value chain.

Although Porter does not show it on this diagram, you should assume that some primary activity is initiated on the lower left of the diagram when a customer orders a product, and ends on the right side when the product is delivered to the customer. Of course, it may be a bit more complex, with marketing stimulating the customer to order and service following up the delivery of the order with various activities, but those details are avoided in this diagram. Figure 1.2 simply focuses on what happens between the order and the final delivery—on the value chain or the large-scale business process that produces the product. What is important to Porter’s concept is that every function involved in the production of the product, and all the support services, from IT to accounting, should be included in a single value chain. It is only by including all the activities involved in producing the product that a company is in a position to determine exactly what the product is costing and what margin the firm achieves when it sells the product.

As a result of Porter’s work, a new approach to accounting, Activity-Based Costing, has become popular and is used to determine the actual value of producing specific products.

Geary Rummler was the second major business process guru of the 1980s. With a background in business management and behavioral psychology, Rummler worked for years on employee training and motivation issues. Eventually, Rummler and his colleagues established a specialized discipline that is usually termed Human Performance Technology. Rummler’s specific focus was on how to structure processes and activities to guarantee that employees—be they managers, salespeople, or production line workers—would function effectively. In the 1960s and 1970s he relied on behavioral psychology and systems theory to explain his approach, but during the course of the 1980s he focused increasingly on business process models.

When Porter’s concept of a value chain is applied to a business organization a different type of diagram is produced. Figure 1.3 illustrates a value chain or business process that cuts across five departmental or functional boundaries, represented by the underlying organizational chart. The boxes shown within the process arrow are subprocesses. The subprocesses are initiated by an input from a customer, and the process ultimately produces an output that is consumed by a customer. As far as I know, this type of diagram was first used by another management systems theorist, Geary Rummler, in 1984.

This can all get confusing, so it’s worth taking a moment to be clear. Either a system or a process converts inputs into outputs. In effect, a business process is just one type of system. Similarly, we can think of a business organization as a system, or as a type of large business process. A business organization takes various types of inputs (e.g., materials, parts, etc.) and converts them into products or services that are sold (output) to customers. If a business organization is relatively simple and only has one value chain—if, in other words, the organization only creates one line of products or services—then the business organization is itself a value chain, and both are processes. If a business organization contains more than one value chain, then the business organization is a process and it has two or more value chains as subprocesses.

At the end of the 1980s Rummler and a colleague, Alan Brache, wrote a book, Improving Performance: How to Manage the White Space on the Organization Chart, which described the approach they had developed while consulting on process improvement during that decade. Rummler focused on organizations as systems and worked from the top down to develop a comprehensive picture of how organizations were defined by processes and how people defined what processes could accomplish. He provided a detailed methodology for how to analyze an organization, how to analyze processes, how to redesign and then improve processes, how to design jobs, and how to manage processes once they were in place. The emphasis on “the white space on the organization chart” stressed the fact that many process problems occurred when one department tried to hand off things to the next. The only way to overcome those interdepartmental problems, Rummler argued, was to conceptualize and manage processes as wholes.

Later, in the 1990s Hammer and Davenport would exhort companies to change and offered many examples about how changes had led to improved company performance. Similarly, IDS Scheer would offer a software engineering methodology for process change. Rummler and Brache offered a systematic, comprehensive approach designed for business managers. The book that Rummler and Brache wrote did not launch the BPR movement in the 1990s. The popular books written by Hammer and Davenport launched the reengineering movement. Once managers became interested in reengineering, however, and began to look around for practical advice about how to actually accomplish process change, they frequently arrived at Improving Performance. Thus, the Rummler-Brache methodology became the most widely used systematic business process methodology in the mid-1990s.

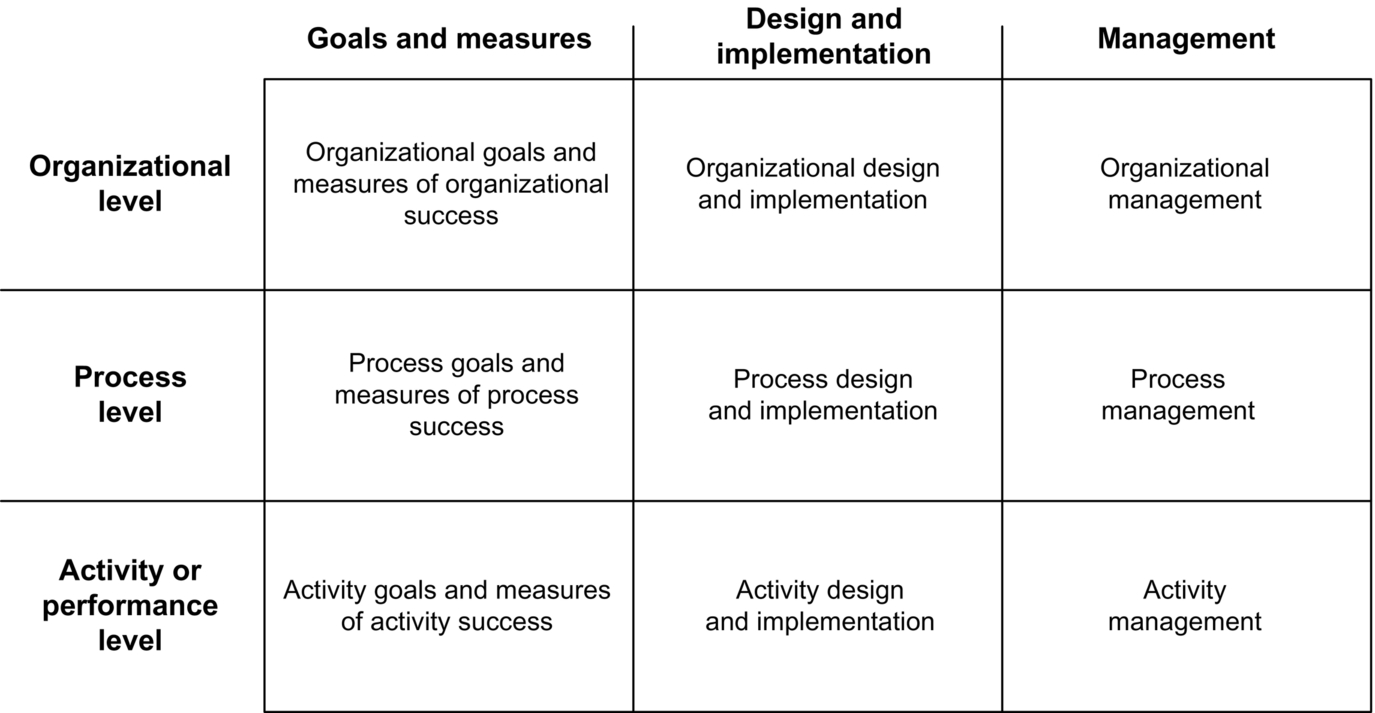

One of the most important contributions made by Rummler and Brache was a framework that showed, in a single diagram, how everything related to everything else. They define three levels of performance: (1) an organizational level, (2) a process level, and (3) a job or performer level. This is very similar to the levels of concern we will describe in a bit, except that we refer to level (3) as the implementation or resource level to emphasize that an activity can be performed by an employee doing a job, by a machine or robot, or by a computer executing a software application. Otherwise, our use of levels of concern in this book mirrors the levels described in Rummler-Brache in 1990 (see Figure 1.4).

Notice how similar the ideas expressed in the Rummler-Brache framework are to the ideas expressed in the Software Engineering Institute (SEI) Capability Maturity Model (CMM) we considered in the introduction. Both seek to describe an organization that is mature and capable of taking advantage of systematic processes. Both stress that we must be concerned not only with the design of processes themselves, but also with measures of success and with the management of processes. In effect, the CMM diagram describes how organizations evolve toward process maturity, and the Rummler-Brache framework describes all the things that a mature organization must master.

Mature organizations must align both vertically and horizontally. Activity goals must be related to process goals, which must in turn be derived from the strategic goals of the organization. Similarly, a process must be an integrated whole, with goals and measures, a good design that is well implemented, and a management system that uses the goals and measures to ensure that the process runs smoothly and, if need be, is improved.

The Rummler-Brache methodology has helped everyone involved in business process change to understand the scope of the problem, and it provides the foundation on which all of today’s comprehensive process redesign methodologies are based.

Prior to the work of systems and management theorists like Porter and Rummler, most companies had focused on dividing processes into specific activities that were assigned to specific departments. Each department developed its own standards and procedures to manage the activities delegated to it. Along the way, in many cases, departments became focused on doing their own activities in their own way, without much regard for the overall process. This is often referred to as silo thinking, an image that suggests that each department on the organization chart is its own isolated silo.

In the early years of business computing a sharp distinction was made between corporate computing and departmental computing. A few systems like payroll and accounting were developed and maintained at the corporate level. Other systems were created by individual departments to serve their specific needs. Typically, one departmental system would not talk to another, and the data stored in the databases of sales could not be exchanged with data in the databases owned by accounting or by manufacturing. In essence, in an effort to make each department as professional and efficient as possible the concept of the overall process was lost.

The emphasis on value chains and systems in the 1980s and the emphasis on BPR in the early 1990s was a revolt against excessive departmentalism and a call for a more holistic view of how activities needed to work together to achieve organizational goals.

The Six Sigma Movement

The third main development in the 1980s evolved from the interaction of the Rummler-Brache approach and the quality control movement. In the early 1980s Rummler had done quite a bit of consulting at Motorola and had helped Motorola University set up several courses in process analysis and redesign. In the mid-1980s a group of quality control experts wedded Rummler’s emphasis on process with quality and measurement concepts derived from quality control gurus W. Edwards Deming and Joseph M. Juran to create a movement that is now universally referred to as Six Sigma. Six Sigma is more than a set of techniques, however. As Six Sigma spread, first from Motorola to GE, and then to a number of other manufacturing companies, it developed into a comprehensive training program that sought to create process awareness on the part of all employees in an organization. Organizations that embrace Six Sigma not only learn to use a variety of Six Sigma tools, but also embrace a whole culture dedicated to training employees to support process change throughout the organization.

Prior to Six Sigma, quality control professionals had explored a number of different process improvement techniques. ISO 9000 is a good example of another quality control initiative. This international standard describes activities organizations should undertake to be certified ISO 9000 compliant. Unfortunately, ISO 9000 efforts usually focus on simply documenting and managing procedures. Recently, a newer version of this standard, ISO 9000:2000, has become established. Rather than focusing so much on documentation the new standard is driving many companies to think in terms of processes. In many cases this has prompted management to actually start to analyze processes and use them to start to drive change programs. In both cases, however, the emphasis is on documentation and measurement while what organizations really need are ways to improve quality.

At the same time that companies were exploring ISO 9000 they were also exploring other quality initiatives like statistical process control, total quality management, and just-in-time manufacturing. Each of these quality control initiatives contributed to the efficiency and quality of organizational processes. All this jelled at Motorola with Six Sigma, which has evolved into the most popular corporate process movement today. Unfortunately, Six Sigma’s origins in quality control and its heavy emphasis on statistical techniques and process improvement have often put it at odds with other, less statistical approaches to process redesign, like the Rummler-Brache methodology, and with process automation. That, however, is beginning to change, and today Six Sigma groups in leading corporations are reaching out to explore the whole range of business process change techniques. This book is not written from a traditional Six Sigma perspective, but we believe that Six Sigma practitioners will find the ideas described here useful and we are equally convinced that readers from other traditions will find it increasingly important and useful to collaborate with Six Sigma practitioners.

Business Process Change in the 1990s

Much of the current corporate interest in business process change can be dated from the BPR movement that began in 1990 with the publication of two papers: Michael Hammer’s “Reengineering Work: Don’t Automate, Obliterate” (Harvard Business Review, July/August 1990) and Thomas Davenport and James Short’s “The New Industrial Engineering: Information Technology and Business Process Redesign” (Sloan Management Review, Summer 1990). Later, in 1993, Davenport wrote a book, Process Innovation: Reengineering Work through Information Technology, and Michael Hammer joined with James Champy to write Reengineering the Corporation: A Manifesto for Business Revolution.

BPR theorists like Champy, Davenport, and Hammer insisted that companies must think in terms of comprehensive processes, similar to Porter’s value chains and Rummler’s organization level. If a company focused only on new product development, for example, the company might improve the new product development subprocess, but it might not improve the overall process. Worse, one might improve new product development at the expense of the overall value chain. If, for example, new process development instituted a system of checks to ensure higher quality documents, it might produce superior reports, but take longer to produce them, delaying marketing and manufacturing’s ability to respond to sudden changes in the marketplace. Or the new reports might be organized in such a way that they made better sense to the new process development engineers, but became much harder for marketing or manufacturing readers to understand.

Stressing the comprehensive nature of business processes, BPR theorists urged companies to define all of their major processes and then focus on the processes that offered the most return on improvement efforts. Companies that followed this approach usually conceptualized a single business process for an entire product line, and ended up with only 5–10 value chains for an entire company, or division, if the company was very large. The good news is that if companies followed this advice, they were focusing on everything involved in a process and were more likely to identify ways to significantly improve the overall process. The bad news is that when one conceptualizes processes in this way, one is forced to tackle very large redesign efforts that typically involve hundreds or thousands of workers and dozens of major IT applications.

BPR was more than an emphasis on redesigning large-scale business processes. The driving idea behind the BPR movement was best expressed by Thomas Davenport, who argued that IT had made major strides in the 1980s, and was now capable of creating major improvements in business processes. Davenport’s more reasoned analysis, however, did not get nearly the attention that Michael Hammer attracted with his more colorful rhetoric.

Hammer argued that previous generations of managers had settled for using information technologies to simply improve departmental functions. In most cases the departmental functions had not been redesigned but simply automated. Hammer referred to this as “paving over cow paths.” In many cases, he went on to say, departmental efficiencies were maximized at the expense of the overall process. Thus, for example, a financial department might use a computer to ensure more accurate and up-to-date accounting records by requiring manufacturing to turn in reports on the status of the production process. In fact, however, many of the reports came at inconvenient times and actually slowed down the manufacturing process. In a similar way, sales might initiate a sales campaign that resulted in sales that manufacturing could not produce in the time allowed. Or manufacturing might initiate changes in the product that made it easier and more inexpensive to manufacture, but which made it harder for salespeople to sell. What was needed, Hammer argued, was a completely new look at business processes. In most cases, Hammer argued that the existing processes should be “obliterated” and replaced by totally new processes, designed from the ground up to take advantage of the latest information system technologies. Hammer promised huge improvements if companies were able to stand the pain of such comprehensive BPR.

In addition to his call for total process reengineering, Hammer joined Davenport in arguing that processes should be integrated in ways they had not been in the past. Hammer argued that the economist Adam Smith had begun the movement toward increasingly specialized work. Readers will probably all recall that Adam Smith analyzed data on pin manufacture in France in the late 18th century. He showed that one man, working alone, could create a given number of straight pins in a day. But a team, each doing only one part of the task, could produce many times the number of pins per day that the individual members of the team could produce, each working alone. In other words, the division of labor paid off with handsome increases in productivity. In essence, Ford had only been applying Smith’s principle to automobile production when he set up his continuous production line in Michigan in the early 20th century. Hammer, however, argued that Smith’s principle had led to departments and functions that each tried to maximize its own efficiency at the expense of the whole. In essence, Hammer claimed that large companies had become more inefficient by becoming larger and more specialized. The solution, according to Hammer, Davenport, and Champy, was twofold: First, processes needed to be conceptualized as complete, comprehensive entities that stretched from the initial order to the delivery of the product. Second, IT needed to be used to integrate these comprehensive processes.

As a broad generalization the process initiatives, like Six Sigma and Rummler-Brache, that began in the 1980s put most of their emphasis on improving how people performed while BPR in the 1990s put most of the emphasis on using IT more effectively and on automating processes wherever possible.

The Role of IT in BPR

Both Hammer and Davenport had been involved in major process improvement projects in the late 1980s and observed how IT applications could cut across departmental lines to eliminate inefficiencies and yield huge gains in coordination. They described some of these projects and urged managers at other companies to be equally bold in pursuing similar gains in productivity.

In spite of their insistence on the use of IT, however, Hammer and his colleagues feared the influence of IT professionals. Hammer argued that IT professionals were usually too constrained by their existing systems to recognize major new opportunities. He suggested that IT professionals usually emphasized what could not be done rather than focusing on breakthroughs that could be achieved. To remedy this, Hammer and Champy argued that the initial business process redesign teams should exclude IT professionals. In essence, they argue that the initial BPR team should consist of business managers and workers who would have to implement the redesigned process. Only after the redesign team had decided how to change the entire process, Hammer argued, should IT people be called in to advise the team on the systems aspects of the proposed changes.

In hindsight, one can see that the BPR theorists of the early 1990s underestimated the difficulties of integrating corporate systems with the IT technologies available at that time. The BPR gurus had watched some large companies achieve significant results, but they failed to appreciate that the sophisticated teams of software developers available to leading companies were not widely available. Moreover, they failed to appreciate the problems involved in scaling up some of the solutions they recommended. And they certainly compounded the problem by recommending that business managers redesign processes without the close cooperation of their IT professionals. It is true that some IT people resisted major changes, but in many cases they did so because they realized, better than most business managers, just how much such changes would cost. Worse, they realized that many of the proposed changes could not be successfully implemented at their companies with the technologies and personnel they had available.

Some of the BPR projects undertaken in the mid-1990s succeeded and produced impressive gains in productivity. Many others failed and produced disillusionment with BPR. Most company managers intuitively scaled down their BPR efforts and did not attempt anything as large or comprehensive as the types of projects recommended in the early BPR books.

The Misuses of BPR

During this same period many companies pursued other goals under the name of BPR. Downsizing was popular in the early to mid-1990s. Some of it was justified. Many companies had layers of managers whose primary function was to organize information from line activities and then funnel it to senior managers. The introduction of new software systems and tools that made it possible to query databases for information also meant that senior managers could obtain information without the need for so many middle-level managers. On the other hand, much of the downsizing was simply a natural reduction of staff in response to a slowdown in the business cycle. The latter was appropriate, but it led many employees to assume that any BPR effort would result in major reductions in staff.

Because of some widely discussed failures, and also as a result of employee distrust, the term BPR became unpopular during the late 1990s and has gradually fallen into disuse. As an alternative, most companies began to refer to their current business process projects as “business process improvement” or “business process redesign.” Recently, the term “digital transformation” has become popular. It emphasizes the importance of the use of IT techniques in business process redesign, and to a lesser degree an emphasis on using new technologies to introduce discontinuous changes that require that the business be reconceptualized in major ways.

Lean and the Toyota Production System

Independent of BPR a totally separate approach to business process improvement, popularly called “Lean,” also started to became popular in the 1990s. In the late 1980s a team of MIT professors visited Japan to study Japanese auto-manufacturing processes. In 1990 James Womack, Daniel Jones, and Daniel Roos published a book, The Machine That Changed the World: The Story of Lean Production. In essence, the authors reported that what they saw at the Toyota factories in Japan was so revolutionary that it deserved emulation in the West. Since this first report, process people throughout the world have studied the Toyota approach, which is now generally termed the Toyota Production System (TPS). In the initial book Womack, Jones, and Roos tended to emphasize Toyota’s process improvement methods, which included a careful study of each activity in a process stream to determine if the activity did or did not add value to the final product. Lean practitioners referred to the various ways in which activities failed to add value as forms of waste (muta in Japanese), and soon process people were talking about the seven types of waste, or perhaps the eight types, depending on who you read.

Now that two decades have passed, now that Toyota has factories in the United States and has become the largest auto producer in the world, and dozens of books have been published on Lean and TPS, we have a broader understanding of the entire Toyota approach to process improvement. The TPS starts with the CEO and permeates the entire organization. In essence, all the managers and employees at the Toyota plants are constantly focused on improving the organization’s business processes. Today, Lean is even more popular than it was in the 1990s, although many think of Lean rather narrowly and have not yet fully understood the comprehensive nature of the TPS approach. At the same time many Six Sigma groups have attempted to combine Lean and Six Sigma into a single approach.

Other Process Change Work in the 1990s

Many of the approaches to business process redesign that emerged in the mid- to late 1990s were driven by software technologies. Some companies used software applications, called workflow systems, to automate business processes. In essence, early workflow systems controlled the flow of documents from one employee to another. The original document was scanned into a computer. Then, an electronic copy of the document was sent to the desk of any employees who needed to see or approve the document. To design workflow systems one created a flow plan, like the diagram shown in Figure 1.3, that specified how the document moved from one employee to the next. The workflow system developers or managers could control the order that electronic documents showed up on employees’ computers by modifying the diagram. Workflow systems became a very popular way to automate document-based processes. Unfortunately, in the early 1990s most workflow systems were limited to automating departmental processes and could not scale up to enterprise-wide processes.

During this same period vendors of off-the-shelf software applications began to organize their application modules so that they could be represented as a business process. In effect, one could diagram a business process by simply deciding how to link a number of application modules. Vendors like SAP, PeopleSoft, Oracle, and JD Edwards all offered systems of this kind, which were usually called ERP systems. In effect, a business analyst was shown an ideal way that several modules could be linked together. A specific company could elect to eliminate some modules and change some of the rules controlling the actions of some of the modules, but overall one was limited to choosing and ordering existing software application modules. Many of the modules included customer interface screens and therefore controlled employee behaviors relative to particular modules. In essence, an ERP system is controlled by another kind of “workflow” system. Instead of moving documents from one employee workstation to another the ERP systems offered by SAP and others allowed managers to design processes that moved information and control from one software module to another. ERP systems allowed companies to replace older software applications with new applications, and to organize the new applications into an organized business process. This worked best for processes that were well understood and common between companies. Thus, accounting, inventory, and human resource processes were all popular targets for ERP systems.

SAP, for example, offers the following modules in their financials suite: Change Vendor or Customer Master Data, Clear Open Items, Deduction Management, Payment with Advice, Clearing of Open Items at Vendor, Reporting for External Business Partners, and SEM: Benchmark Data Collection. They also offer “blueprints,” which are in essence alternative flow diagrams showing how the financial modules might be assembled to accomplish different business processes.

Davenport supported and promoted the use of ERP packaged applications as a way to improve business processes. At the same time, August-Wilhelm Scheer, a software systems theorist, advocated the use of ERP applications for systems development, and wrote several books promoting this approach and the use of a modeling methodology that he named ARIS.

Most large companies explored the use of document workflow systems and the use of ERP systems to automate at least some business processes. The use of document workflow and ERP systems represented a very different approach to process redesign than that advocated by the BPR gurus of the early 1990s. Gurus like Hammer had advocated a total reconceptualization of complete value chains. Everything was to be reconsidered and redesigned to provide the company with the best possible new business process. The workflow and ERP approaches, on the other hand, focused on automating existing processes and replacing existing, departmentally focused legacy systems with new software modules that were designed to work together. These systems were narrowly focused and relied heavily on IT people to put them in place. They provided small-scale improvements rather than radical redesigns.

We have already considered two popular software approaches to automating business processes: workflow and the use of systems of ERP applications. Moving beyond these specific techniques, any software development effort could be a response to a business process challenge. Any company that seeks to improve a process will at least want to consider if the process can be automated. Some processes cannot be automated with existing technology. Some activities require people to make decisions or to provide a human interface with customers. Over the course of the past few decades, however, a major trend has been to increase the number of tasks performed by computers. As a strong generalization, automated processes reduce labor costs and improve corporate performance.

Software engineering usually refers to efforts to make the development of software more systematic, efficient, and consistent. Increasingly, software engineers have focused on improving their own processes and on developing tools that will enable them to assist business managers to automate business processes. We mentioned the work of the SEI at Carnegie Mellon University on CMM, a model that describes how organizations mature in their use and management of processes.

At the same time, software engineers have developed modeling languages for modeling software applications and tools that can generate code from software models. Some software theorists have advocated developing models and tools that would allow business analysts to be more heavily involved in designing the software, but to date this approach has been limited by the very technical and precise nature of software specifications. As an alternative, a good deal of effort has been focused on refining the concept of software requirements—the specification that a business process team would hand to a software development team to indicate exactly what a software application would need to do to support a new process.

The more complex and important the business process change, the more likely a company will need to create tailored software to capture unique company competencies. Whenever this occurs, then languages and tools that communicate between business process teams and IT teams become very important.

The Internet

In the early 1990s, when Hammer and Davenport wrote their BPR books, the most popular technique for large-scale corporate systems integration was electronic data interchange (EDI). Many large companies used EDI to link with their suppliers. In general, however, EDI was difficult to install and expensive to maintain. As a practical matter, EDI could only be used to link a company to its major suppliers. Smaller suppliers could not afford to install EDI and did not have the programmers required to maintain an EDI system.

By the late 1990s, when enthusiasm for BPR was declining and at the same time that companies began to explore workflow and ERP approaches, new software technologies began to emerge that really could deliver on the promise that the early BPR gurus had oversold. Among the best known are the Internet, email, and the Web, which provide powerful ways to facilitate interactions between employees, suppliers, and customers.

The Internet does not require proprietary lines, but runs instead on ordinary telephone lines and increasingly operates in a wireless mode. At the same time, the Internet depends on popular, open protocols that were developed by the government and were widely accepted by everyone. A small company could link to the Internet and to a distributor or supplier in exactly the same way that millions of individuals could surf the Web, by simply acquiring a PC and a modem and using browser software. Just as the Internet provided a practical solution for some of the communications problems faced by companies, email and the Web created a new way for customers to communicate with companies. In the late 1990s customers rapidly acquired the habit of going to company websites to find out what products and services were available. Moreover, as fast as companies installed websites that would support it, customers began to buy products on line. In effect, the overnight popularity of the Internet, email, and the Web in the late 1990s made it imperative that companies reconsider how they had their business processes organized to take advantage of the major cost savings that the use of the Internet, Web, and email could provide. As additional products from wireless iPads to smartphones have proliferated in the first decade of the 21st century the ways in which employees and customers can interact with businesses have grown exponentially, requiring almost all business processes to be reconsidered.

Of course, the story is more complex. A number of dot.com companies sprang up, promising to totally change the way companies did business by using the Internet, Web, and email. Some, like Amazon and Apple’s iTunes, have revolutionized major industries. Most early dot.com companies, however, disappeared when the stock market realized that their business models were unsound.

In the nearly two decades since the dot.com companies were a business sensation, Internet-based applications (apps) of all kinds have proliferated and completely changed our lives. One thinks of social media like Google and Facebook and whole ecosystems of interrelated web applications that provide us maps and driving directions, online books, and various smartphone apps of all kinds. These various apps provide challenges for process designers that we will consider in later chapters.

A Quick Summary

Figure 1.5 provides an overview of some of the historical business process technologies we have described in this chapter. Most are still actively evolving. As you can see in the figure, business process management has evolved from a diverse collection of ideas and traditions. We have grouped them very loosely into three general traditions: (1) the Industrial Engineering/Quality Control tradition, which is primarily focused on improving operational processes, (2) the Management and Business Process Redesign tradition, which is focused on aligning or changing major business processes to significantly improve organizational performance, and (3) the IT tradition, which is primarily focused on process automation. Most large companies have groups working in each of these traditions, and increasingly the different traditions are borrowing from each other. And, of course, none of the groups has confined itself to a single tradition. Thus, Lean Six Sigma is focused on process improvement, but it also supports process management and process redesign initiatives. Similarly, IT is focused on automation, but IT process groups are often heavily involved in process redesign projects and are strongly committed to architecture initiatives that incorporate business process architectures.

The author of this book comes from the Management and Process Redesign tradition—he began his process work as an employee of a consulting company managed by Geary Rummler—and this book describes that tradition in more detail than any other. However, the author has worked with enough different companies to know that no solution fits every situation. Thus, he is firmly committed to a best-practices approach that seeks to combine the best from all the process change traditions and provides information on the other traditions whenever possible to encourage the evolving synthesis of the different process traditions. Senior managers do not make the fine distinctions that we illustrate in Figure 1.5. Executives are interested in results, and, increasingly, effective solutions require practitioners from the different traditions to work together. Indeed, one could easily argue that the term “business process management” was coined to suggest the emergence of a more synthetic, comprehensive approach to process change that combines the best of process management, redesign, process improvement, and process automation.

Business Process Change in the New Millennium

For a while the new millennium did not seem all that exciting. Computer systems did not shut down as the year 2000 began. The collapse of the dot.com market and a recession seemed to provide a brief respite from the hectic business environment of the 1990s. By 2002, however, the sense of relentless change had resurfaced.

The corporate interest in business process change, which seemed to die down a bit toward the end of the 20th century, resurfaced with a vengeance. Many people working in IT realized that they could integrate a number of diverse technologies that had been developed in the late 1990s to create a powerful new approach to facilitate the day-to-day management of business processes. The book that best reflected this new approach was called Business Process Management: The Third Wave by Howard Smith and Peter Fingar. They proposed that companies combine workflow systems, software applications integration systems, and Internet technologies to create a new type of software application. In essence, the new software—business process management software (BPMS)—would coordinate the day-to-day activities of both employees and software applications. The BPMS applications would use process models to define their functionality, and make it possible for business managers to change their processes by changing the models or rules that directed the BPMS applications. All of these ideas had been tried before, with earlier technologies, but in 2003 it all seemed to come together, and dozens of vendors rushed to create BPMS products. As the enthusiasm spread the vision was expanded and other technologists began to suggest how BPMS applications could drive management dashboards that would let managers control processes in something close to real time. A decade later, process mining promised help in the analysis of information flows within organizations and new analytic tools offered ways to search the huge databases generated by the use of email and even newer mobile devices, and to generate ongoing advice to management. As each new technology has been brought to market the BPMS tools have become even more powerful and flexible.

In 2002 there were no BPM conferences in the United States. In 2012 there were a dozen BPM meetings in the nation, and the first major international BPM conference was held in China. In 2003 Gartner suggested that BPMS vendors earned around $500 million. In 2007 Gartner projected the market for BPMS products would exceed $1 billion by 2009. In 2012 Gartner projected a market of $2.6 billion, while the ever-optimistic Forrester projected the market at $6.3 billion.

Were everyone only excited about BPMS then we might suggest that the market was simply a software market, but that was hardly the case. All the various aspects of business process have advanced during the same period. Suddenly large companies were making major investments in the creation of business process architectures. To create these architectures they sought to define and align their processes while simultaneously defining metrics to measure process success. Similarly, there was a broad movement toward reorganizing managers to support process goals. The Balanced Scorecard played a major role in this. There has been renewed interest in using maturity models to evaluate corporate progress. A number of industry groups have defined business process frameworks, like the Supply Chain Council’s SCOR, the TeleManagement Forum’s eTOM, and the APQC’s business process frameworks, and management has adopted these frameworks to speed the development of enterprise-level architectures and measurement systems.

Process redesign and improvement have also enjoyed a renaissance, and Six Sigma has expanded from manufacturing to every possible industry while simultaneously incorporating Lean. A dozen new process redesign methodologies and notations have been published in the past few years, and more than 200 books on the various aspects of process change have been published. It is hard to find a business publication that is not talking about the importance of process change. Clearly this interest in business process change is not driven by just BPMS or by any other specific technology. Instead, it was being driven by the deeper needs of the business managers in the 2000s. This enthusiasm continued till 2007 when an economic recession slowed things down a bit. A recovery is now underway, supported by all the concerns of the early 2000s and encouraged by new innovations in AI and social media that will require major investments in new business process redesign efforts in the years ahead.

What Drives Business Process Change?

So far, we have spoken of various approaches to business process change. To wrap up this discussion, perhaps we should step back and ask what drives the business interest in business processes in the first place. The perennial answers are very straightforward. In economically bad times, when money is tight, companies seek to make their processes more efficient to save money. In economically good times, when money is more available, companies seek to expand to ramp up production and to enter new markets. They improve processes to offer better products and services in hopes of attracting new customers or taking customers away from competitors.

Since the 1980s, however, the interest in process has become more intense. The new interest in process is driven by change. Starting in the 1980s, large US companies became more engaged in world trade. At the same time, foreign companies began to show up in the United States and compete with established market leaders. Thus, in the 1970s most Americans who wanted to buy a car chose among cars sold by General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler. By the mid-1980s Americans were just as likely to consider a VW, a BMW, a Nissan, or a Honda. Suddenly, the automobile market had moved from a continental market to a world market. This development has driven constant changes in the auto market and it is not about to let up in the next few years as auto companies throughout the world race to shift from cars with gasoline engines to cars powered by electric engines.

Increased competition also led to mergers and acquisitions, as companies attempted to acquire the skills and technologies they needed to control their markets or enter new ones. Every merger between rivals in the same industry creates a company with two different sets of processes, and someone has to figure out which processes the combined company will use going forward.

During this same period, IT technology was remaking the world. The first personal computers appeared at the beginning of the 1980s. The availability of relatively cheap desktop computers made it possible to do things in entirely different and much more productive ways. In the mid-1990s the Internet burst on the scene and business was revolutionized again. Suddenly people bought PCs for home use so they could communicate via email and shop on line. Companies reorganized their processes to support web portals. That, in turn, suddenly increased competitive pressures as customers in one city could as easily buy items from a company in another city or country as from the store in their neighborhood. Amazon.com revolutionized the way books are bought and sold. Then came iPads, intelligent phones, intelligent cars, GPS, and the whole wireless revolution, with music, TV, and movies available on demand. Today an employee or a customer using some type of computer can access information or buy from your organization at any time from any location in the world.

The Internet and the Web and the broader trend toward globalization also made it easier for companies to coordinate their efforts with other companies. Increased competition and the search for greater productivity led companies to begin exploring all kinds of outsourcing. If another company could provide all the services your company’s HR or IT departments used to provide, and was only an email away, it was worth considering. Suddenly, companies that had historically been manufacturers were outsourcing the manufacture of their products to China and were focusing instead on sticking close to their customers, so they could specialize in designing and selling new products that would be manufactured by overseas companies and delivered by companies who specialized in the worldwide delivery of packages.

In part, new technologies like the Internet and the Web are driving these changes. They make worldwide communication easier and less expensive than in the past. At the same time, however, the changes taking place are driving companies to jump on any new technology that seems to promise them an edge over their competition. Wireless laptops, cell phones, and personal digital assistants are being used by business people to work more efficiently. At the same time, the widespread purchase of iPods by teenagers is revolutionizing the music industry and driving a host of far-reaching changes and realignments.

We won’t go on. Lots of authors and many popular business magazines write about these changes each month. Suffice it to say that change and competition have become relentless. Large companies are reorganizing to do business on a worldwide scale, and predictably some will do it better than others and expand, while those that are less successful will disappear. Meantime, smaller companies are using the Internet and the Web to explore the thousands of niche service markets that have been created.

Change and relentless competition call for constant innovation and for constant increases in productivity, and those in turn call for an even more intense focus on how work gets done. To focus on how the work gets done is to focus on business processes. Every manager knows that if his or her company is to succeed it will have to figure out how to do things better, faster, and cheaper than they are being done today, and that is what the focus on process is all about.

Notes and References

We provided a wide-ranging history of the evolution of business process techniques and concerns. We have included a few key books that provide a good overview to the concepts and techniques we described.

McCraw, Thomas K. (Ed.), Creating Modern Capitalism: How Entrepreneurs, Companies, and Countries Triumphed in Three Industrial Revolutions, Harvard University Press, 1997. A good overview of the Industrial Revolution, the rise of various early companies, the work of various entrepreneurs, and the work of management theorists like F.W. Taylor.

Taylor, Frederick W., The Principles of Scientific Management, Harper’s, 1911. For a modern review of the efficiency movement and Taylor check Daniel Nelson’s Frederick W. Taylor and the Rise of Scientific Management, University of Wisconsin Press, 1980.

Bertalanffy, Ludwig von, General Systems Theory: Foundations, Development, Applications, George Braziller, 1968. An early book that describes how engineering principles developed to control systems ranging from thermostats to computers provided a better way to describe a wide variety of phenomena.

Beer, Stafford, Brain of the Firm, Harmondsworth, 1967. Early, popular book on how managers should use a systems approach.

Forrester, Jay, Principles of Systems, Pegasus Communications, 1971. Forrester was an influential professor at MIT who wrote a number of books showing how systems theory could be applied to industrial and social systems. Several business simulation tools are based on Forrester’s ideas, which are usually referred to as systems dynamics, since they focus on monitoring and using changing rates of feedback to predict future activity.

Sterman, John D., Business Dynamics: Systems Thinking and Modeling for a Complex World, Irwin McGraw-Hill, 2000. Sterman is one of Forrester’s students at MIT, and this is a popular textbook for those interested in the technical details of systems dynamics, as applied to business problems.

Senge, Peter M., The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization, Currency Doubleday, 1994. Senge is also at the Sloan School of Management at MIT, and a student of Forrester. Senge has created a more popular approach to systems dynamics that puts the emphasis on people and the use of models and feedback to facilitate organizational development. In the Introduction we described mature process organizations as organizations that totally involved people in constantly improving the process. Senge would describe such an organization as a learning organization.

Porter, Michael E., Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance, The Free Press, 1985. This book focuses on the idea of competitive advantage and discusses how companies obtain and maintain it. One of the key techniques Porter stresses is an emphasis on value chains and creating integrated business processes that are difficult for competitors to duplicate.

Hammer, Michael, “Reengineering Work: Don’t Automate, Obliterate,” Harvard Business Review, July–August 1990. This article, and the one below by Davenport and Short, kicked off the BPR fad. The books that these authors are best known for did not come until a couple of years later.

Rummler, Geary. 1984. Personal correspondence. Geary sent me a photocopy of a page from a course he gave in 1984 with a similar illustration.

Rummler, Geary, and Alan Brache, Performance Improvement: Managing the White Space on the Organization Chart, Jossey-Bass, 1990. Still the best introduction to business process redesign for senior managers. Managers read Hammer and Davenport in the early 1990s, and then turned to Rummler and Brache to learn how to actually do business process redesign. So many ideas that we now associate with business process change originated with Geary Rummler.

Hammer, Michael, and James Champy, Reengineering the Corporation: A Manifesto for Business Revolution, Harper Business, 1993. This was a runaway bestseller that got everyone in business talking about reengineering in the mid-1990s. It argued for a radical approach to redesign. Some companies used the ideas successfully; most found it too disruptive.

Davenport, Thomas H., Process Innovation: Reengineering Work through Information Technology, Harvard Business School Press, 1993. This book doesn’t have the breathless marketing pizzazz that Hammer’s book has, but it’s more thoughtful. Overall, however, both books advocate radical change to take advantage of the latest IT technologies.

Smith, Adam, The Wealth of Nations (any of several editions). Classic economics text that advocates, among other things, the use of work specialization to increase productivity.

Fischer, Layna (Ed.), The Workflow Paradigm: The Impact of Information Technology on Business Process Reengineering (2nd ed.), Future Strategies, 1995. A good overview of the early use of workflow systems to support BPR efforts.

Davenport, Thomas H., Mission Critical: Realizing the Promise of Enterprise Systems, Harvard Business School Press, 2000. This is the book in which Davenport laid out the case for using ERP systems to improve company processes.

Ramias, Alan, The Mists of Six Sigma, October 2005, available at http://www.bptrends.com. Excellent history of the early development of Six Sigma at Motorola.

Scheer, August-Wilhelm, Business Process Engineering: Reference Models for Industrial Enterprises (2nd ed.), Springer, 1994. Scheer has written several books, all very technical, that describe how to use IT systems and modeling techniques to support business processes.

Harry, Mikel J., and Richard Schroeder, Six Sigma: The Breakthrough Management Strategy Revolutionizing the World’s Top Corporations, Doubleday & Company, 1999. An introduction to Six Sigma by the Motorola engineer who is usually credited with originating the Six Sigma approach.

Harrington, H. James, Erik K. C. Esseling and Harm Van Nimwegen, Business Process Improvement Workbook, McGraw-Hill, 1997. A very practical introduction to process improvement, very much in the Six Sigma tradition, but without the statistics and with a dash of software diagrams.

Boar, Bernard H., Practical Steps for Aligning Information Technology with Business Strategies: How to Achieve a Competitive Advantage, Wiley, 1994. Lots of books have been written on business-IT alignment. This one is a little out of date, but still very good. Ignore the methodology, which gets too technical, but focus on the overviews of IT and how they support business change.

CIO, “Reengineering redux,” CIO Magazine, March 1, 2000, pp. 143–156. A roundtable discussion between Michael Hammer and four other business executives on the state of reengineering today. They agree on the continuing importance of process change. More on Michael Hammer’s recent work is available at http://www.hammerandco.com.

Smith, Howard, and Peter Fingar, Business Process Management, The Third Wave, Meghan-Kiffer Press, 2003. Although this book is a bit over the top in some of its claims, like Hammer and Champy’s Reengineering the Corporation, it got people excited about the idea of Business Process Management Software systems and helped kick off the current interest in BPM.

Womack, James P., Daniel T. Jones, and Daniel Roos, The Machine that Changed the World: The Story of Lean Production, Harper Collins, 1990. The book that launched the interest in Lean and the TPS in the United States.