Process management

Keywords

Functional management; IT Governance Institute (ITGI)’s COBIT (control objectives for information and related technology) framework; Managing managers; Matrix management; Organization chart; Project Management Institute (PMI) project management; Process management; SCOR (Supply Chain Operations Reference) management framework; Software Engineering Institute (SEI) Capability Maturity Model Integrated (CMMI) management; Value chain managers

Managers plan, organize, lead, and control the work of others to achieve their goals. There are two senses in which we will discuss process management in this book. We will consider process management in conjunction with how senior managers understand the goals and activities of their organizations. Separately, we will discuss how the activities of managers impact the success of specific business processes. In this section, which is focused on enterprise issues, we will focus on understanding how the ideal of a “process” helps managers understand their organization’s goals. We will also consider how an organization might organize itself to support process managers. In a separate chapter in Part II, when we consider business process redesign, we will consider how managers effect the success of specific business processes.

The Process Perspective

Managers, from the CEO down, are responsible for the ongoing activities of their organizations. To set goals and make decisions about their organizations they need to understand how their organizations are performing. There are different ways, historically, that managers have done this.

- 1. One approach is to think of the organization as a black box that takes in capital, and after using it generates a return in that investment. This is the perspective that managers adopt when they focus extensively on spreadsheets and other financial information.

- 2. Most executives take a broader view, imagine that an organization is trying to accomplish a set of goals, and monitor key performance indicators to determine if the organization is meeting its goals or not.

- 3. Still another approach is to focus on the organization chart, implicitly assuming that people make things happen. If the sales department is not generating the results, then the CEO considers whether or not to replace the head of sales. Similarly, the head of sales looks to see which salespeople are performing poorly, and considers replacing them with new salespeople.

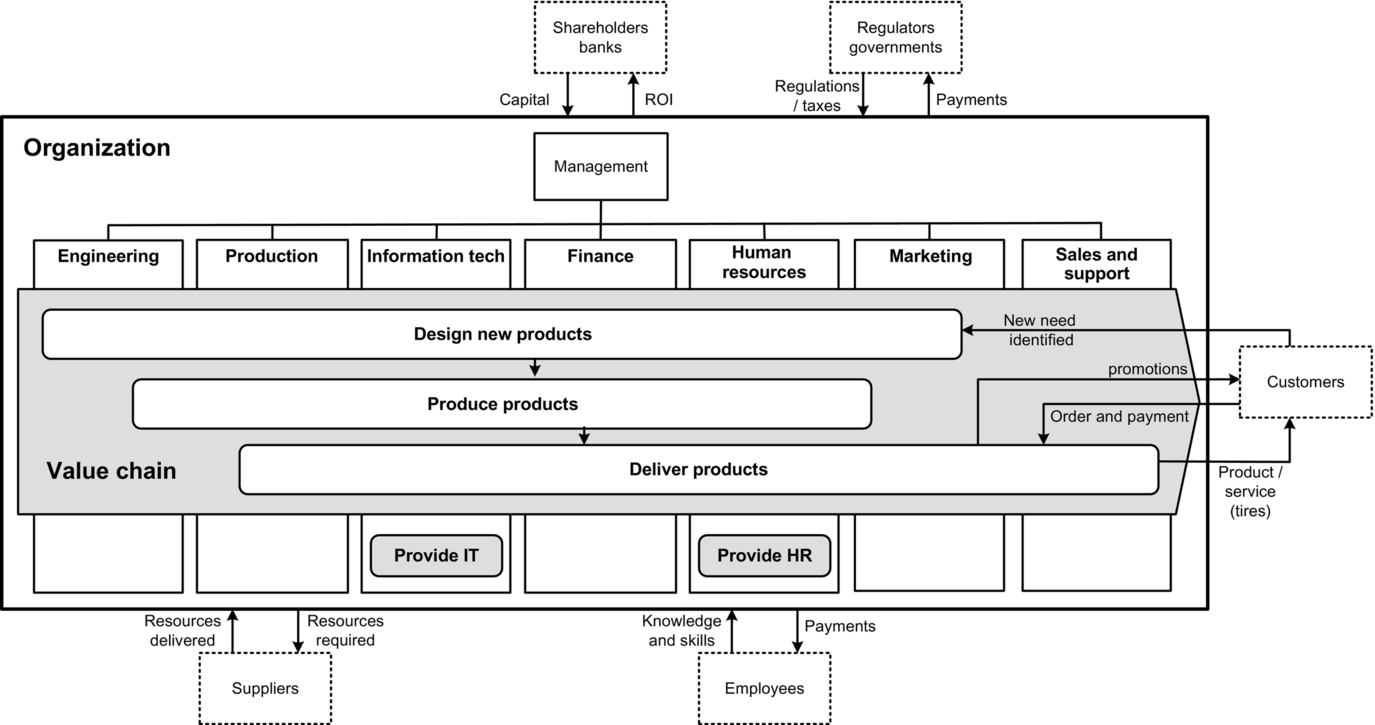

We might term these approaches (1) the financial/return on investment approach, (2) the strategy and goals approach, and (3) the leadership or organization chart approach, most senior executives rely on a mix of these approaches. What all three of these approaches lack, however, is a systematic way of conceptualizing how everything in the organization fits together to produce results for customers. Thinking of an organization as a system or a process that takes inputs and turns them into valued outputs is a fourth approach. The reason that the process approach to management remains popular is that it integrates everything. If the organization is large, we divide it into multiple value chains, each with its own customers and stakeholders, but to keep things simple let’s assume that the organization is a single value chain, as we have pictured it in Figure 6.1. Moreover, let’s assume it has three basic Level 1 processes: one to design new products, one to produce products, and a third to deliver products.

The whole organization is shown in this single picture. The value chain produces products and services that are sold to customers. As time passes the organization may introduce new products or incorporate new technologies to make a better or less expensive product, but the essence of the value chain remains. Departments exist to provide people and activities needed in the major processes that make up the value chain. If we were to expand this diagram we could show the specific activities that were performed by people in specific departments that contributed to the success of the major processes in the value chain. If a department is doing something that does not contribute to the production of value for the customer or for some other stakeholder, then we need to consider dropping it. As important as the customer is, there are other stakeholders, such as the shareholders, government agencies, business partners, and employees, that need to be taken care of to ensure the value chain can continue to function.

Sales may drop, and it may be that the head of sales or specific salespeople should be fired. But it is just as likely that the process needs to be changed. Finances are critical. But cutting costs that result in poorer products and the loss of sales is not a win in the long run. A good strategy and goals are important, but once they are selected the organization needs to have a specific process to ensure that those goals are met. The process perspective is the only perspective that connects everything else together and gives you a concrete way in which to see exactly how those connections lead to positive or negative results. If you take away only one message from this book let it be this: the process perspective is the one perspective that shows a manager how everything in an organization must work together if the organization is to succeed. In this chapter we will consider how the process perspective can improve managerial practices. Similarly, we will consider how savvy managers can improve the results that can be obtained from processes.

What Is Management?

Many books have been written about management. This book is about improving business processes, so we will consider how management can be organized to support effective business processes and vice versa. Before we get into specifics, however, we need to start with some definitions. In the discussion that follows we are talking about roles and not about jobs or individuals. A single individual can fulfill more than one role. Thus, for example, one individual could perform two different managerial roles in two different situations—managing a functional department, but also serving as the manager of a special project team. Similarly, a job can be made up of multiple roles.

Broadly, there are two types of managerial roles: operational management and project management. Operational managers have ongoing responsibilities. Project managers are assigned to manage projects that are limited in time. Thus a project manager might be asked to redesign the widget process, or to conduct an audit of the company’s bonus system. The head of a division, a department head, or the process manager in charge of the day-to-day performance of the widget process all function as operational managers. In the rest of this chapter we will focus on operational management. We will consider project management when we consider what’s involved in managing a business process change project.

Operational management can be subdivided in a number of ways. One distinction is between (1) managers who are responsible for the organization as a whole or for functional units, like sales or accounting, and (2) managers who are responsible for processes, like the widget process (see Figure 6.2). All organizations have organization or functional managers, only some organizations have explicit process managers.

Functional Managers

Most companies are organized into functional units. Smaller companies tend to structure their organizations into departments. Larger organizations often divide their functional units into divisions and then divide the divisions into departments. The definition of a division varies from company to company. In some cases a division is focused on the production of one product line or service line. In that case the division manager can come very close to functioning as a process manager. In other cases divisions represent geographical units, like the European division, which may represent only a part of a process, or even parts of multiple processes that happen to fall in that geographical area. At the same time, there are usually some enterprise-wide departments like IT or finance. Thus in a large company it is not uncommon to have a mix of divisional and departmental units and managers playing multiple roles.

Figure 6.3 illustrates a typical organization chart for a midsize company. The managers reporting to the CEO include both divisional managers (senior vice president, or SVP, widget division) and departmental managers (CIO, CFO). Some of the departmental managers might be responsible for core processes, but it is more likely they are responsible for support processes.

An organization chart like the one illustrated in Figure 6.3 is designed to show which managers are responsible for what functions and to indicate reporting relationships. In Figure 6.3 it’s clear that the manager of production reports to the VP of widget manufacturing. This probably means that the VP of widget manufacturing sets the manager of production’s salary with some guidance from HR, evaluates the manager’s performance, approves his or her budget, and is the ultimate authority on policies or decisions related to widget production.

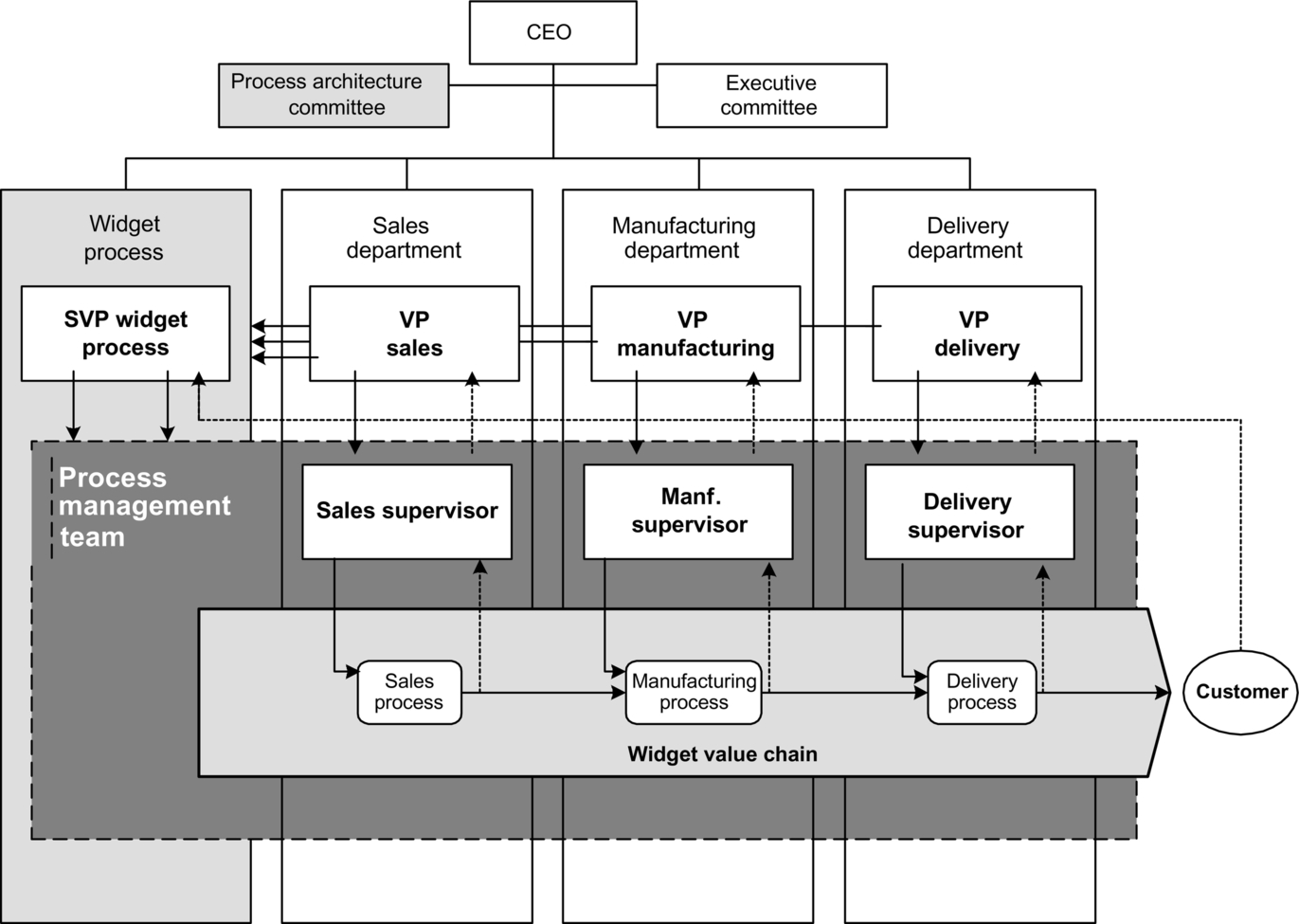

In many organizations mid-level functional managers wear two hats and serve as both a functional manager and a process manager. Consider the managers shown in Figure 6.4. In this simple example a value chain is made up of a sale, a manufacturing, and a delivery process. Each of these processes is managed by an individual who works within a functional unit and reports to the head of the functional unit. Thus the same manager—the sales supervisor, for example—is both the functional and the process manager of the widget sales process.

The situation shown in Figure 6.4 is very common. If problems arise they occur because functional units often defend their territory and resist cooperating with other functional units. What happens if the manufacturing process doesn’t get the sales information it needs to configure widgets for shipment? Does the manufacturing supervisor work with the sales supervisor as one process manager to another to resolve the problem, or does the manufacturing supervisor “kick the problem upstairs” and complain to his or her superior? It’s possible that the VPs of sales, manufacturing, and delivery all sit on a widget process committee and meet regularly to sort out problems. It’s more likely, unfortunately, that the VP of sales manages sales activities in multiple value chains and is more concerned with sales issues than he or she is with widget process issues. In the worst case we have a situation in which the issue between the two widget activities becomes a political one that is fought out at the VP level with little consideration for the practical problems faced by activity-level supervisors. This kind of silo thinking has led many organizations to question the overreliance on functional organization structures.

Before we consider shifting to an alternative approach, however, we need to be clear about the value of the functional approach. As a strong generalization, departmental managers are primarily concerned with the standards and best practices that apply to their particular department or function. In most cases a manager was hired to fulfill a junior position within a department—say, sales or accounting—and has spent the last 20 years specializing in that functional area. He or she is a member of professional sales or accounting organizations, reads books on sales or accounting, and attends conferences to discuss the latest practices in sales or accounting with peers from other companies. In other words, the individual has spent years mastering the details and best practices of sales or accounting by the time he or she is appointed a VP. Such an individual naturally feels that he or she should focus on what they know and not get involved in activities they have never focused on before. This type of specialization is a very valuable feature of the functional approach. Thus, for example, bookkeepers in an organization ought to follow accepted accounting practices. Moreover, they ought to follow the specific policies of the company with regard to credit, handling certain types of transactions, etc. The CFO is responsible to the CEO for ensuring that appropriate standards and practices are followed. In a similar way the head of sales follows standard practices in hiring and motivating the sales force. Moreover, the head of sales is well positioned to recognize that a widget sales supervisor is due a promotion and conclude that she is ready to become the new sales supervisor of the smidget sales process when the current guy retires. Functional management preserves valuable corporate knowledge and brings experience to the supervision of specialized tasks. Sometimes, however, it results in senior managers who are very territorial and prefer to focus on their special area of expertise while ignoring other areas.

Process Managers

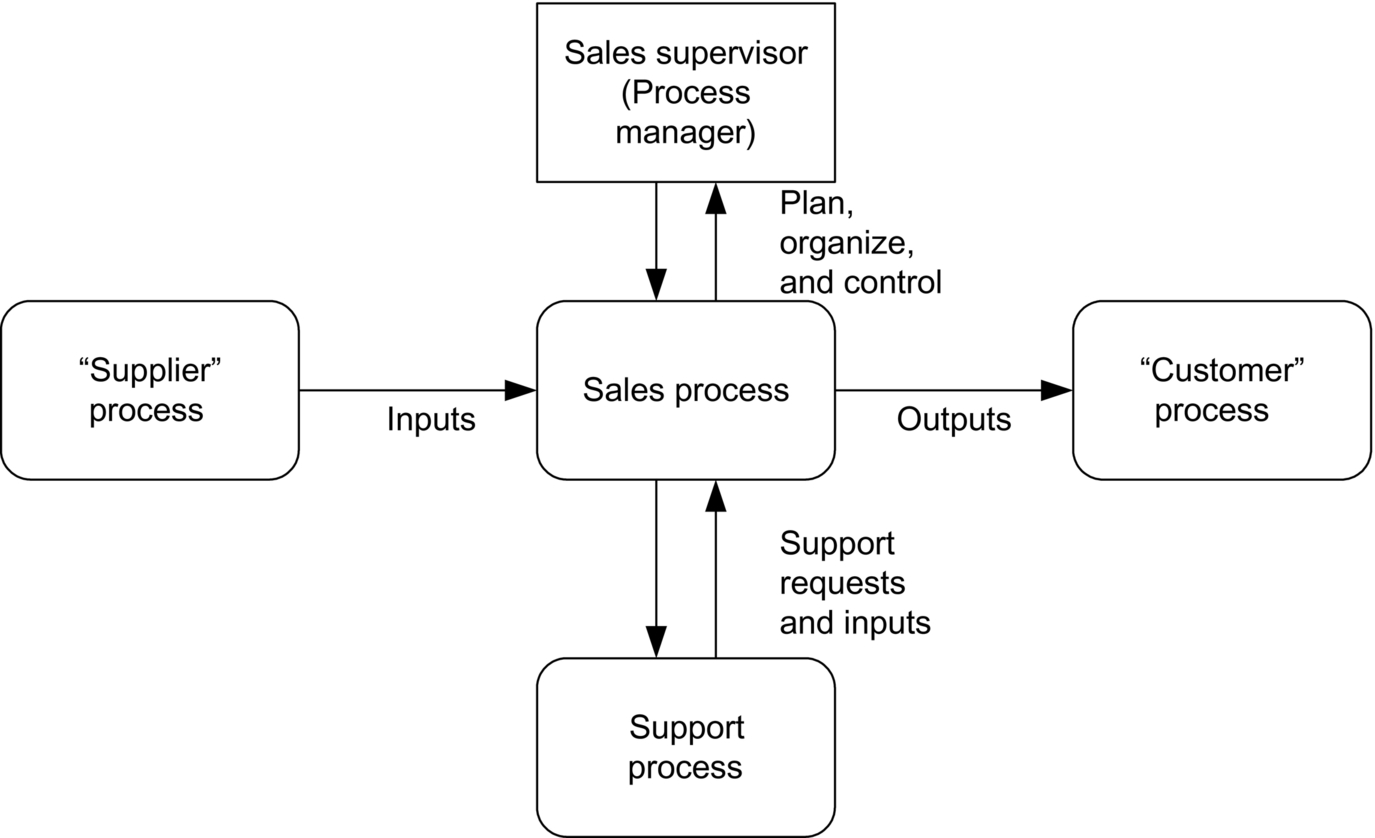

Since we are primarily concerned with process management we will consider the role of a process manager in a little more detail. Figure 6.5 provides a very general overview of the role of a process manager. (Note that in Figure 6.4 we picture the process manager in a box outside the sales process. Earlier, in Figure 6.2 we pictured the process manager insider the process being managed. There is no correct way to do this and we do it differently, depending on what we are trying to emphasize.) This model could easily be generalized to serve as a high-level description of the job of any operational manager. This model could describe the job of the sales supervisor in Figure 5.4, for example. We’ll talk about it, however, to provide a description of the various managerial activities as they relate to a core process. The key point to consider is that an organization is made up of processes, and for each process there must be someone who is responsible for the day-to-day functioning of that process. At lower levels within an organization the individual who is responsible might very well be a functional manager who is also wearing a process manager’s hat. At higher levels in the organization, wearing two hats is harder because value chains and even large processes like new product development and supply chain often cut across functional boundaries.

Ignoring organizational issues for a moment, let’s just consider what sort of work any process manager needs to accomplish. The process manager is responsible for what happens as the process is executed. He or she is also responsible for working with suppliers, customers, and support processes to ensure that the process he or she manages has the resources and support it needs to produce the product or service the process’s customer wants. When one approaches process management in this way, it is often unclear whether one is talking about a role, a process, or an individual. When you undertake specific process redesign projects you will often find yourself analyzing whether or not a specific process manager is performing in a reasonable manner. Things the specific individual does or doesn’t do may result in process inefficiencies. When you focus on organization charts and managerial responsibilities you are usually focused on the role and seek to define who a specific manager would report to, without concerning yourself with the specific individual who might perform the role. Finally, when you focus on the competencies that a process manager should have to function effectively you are focusing on the managerial processes that successful individuals need to master if they are to perform the role effectively.

In Figure 6.6 we have expanded the process management box from Figure 6.5 and inserted some typical managerial processes. Different managerial theorists would divide or clump the activities that we have placed in the four managerial processes in different ways. Our particular approach is simply one alternative. We divide the process management process into four generic subprocesses: one that plans, schedules, and budgets the work of the process; one that organizes the workflow of the process, arranges for needed resources, and defines jobs and success criteria; one that communicates with employees and others about the process; and one that monitors the work and takes action to ensure that the work meets established quality criteria. We have added a few arrows to suggest some of the main relations between the four management processes just described and the elements of the process that is being managed.

Most process managers are assigned to manage an existing process that is already organized and functioning. Thus their assignment does not require them to organize the process from scratch, but if they are wise they will immediately check the process to ensure that it is well organized and functioning smoothly. Similarly, if they inherit the process they will probably also inherit the quality and output measures established by their predecessor. If the new manager is smart he or she will reexamine all the assumptions to ensure that the process is in fact well organized, functioning smoothly, and generating the expected outcomes. If there is room for improvement the new manager should make a plan to improve the process. Once satisfied with the process the manager has some managerial activities that need to be performed on a day-to-day basis and others that need to be performed on a weekly, monthly, or quarterly basis. And then, of course, there are all the specific tasks that occur when one has to deal with the problems involved in hiring a new employee, firing an incompetent employee, and so forth.

Without going into details here, each process manager sometimes functions as if he or she were a process analyst, considering redesigning the process. All of the tools described in this book can be useful to a business manager when he or she is functioning in this role. In essence, the manager must understand the process and know how to make changes that will make the process more efficient and effective.

We’ll consider the specific activities involved in process management in a later chapter when we consider how one approaches the analysis of process problems. At the enterprise level we will be more concerned with how companies establish process managers, how process managers relate to unit or functional managers, and how processes and process managers are evaluated.

Process managers, especially at the enterprise level, have a responsibility to see that all the processes in the organization work together to ensure that the value chain functions as efficiently as possible. While a functional manager would prefer to have all the processes within his or her department operate as efficiently as possible a process-focused manager is more concerned that all the processes in the value chain work well together and would in some cases allow the processes within one functional area to function in a suboptimal way to ensure that the value chain functions more efficiently. Thus, for example, there is a tradeoff between an efficient inventory system and a store that has in stock anything the customer might request. To keep inventory costs down the inventory manager wants to minimize inventory. If that’s done then it follows that customers will occasionally be disappointed when they ask for specific items and learn that they are not in stock. There is no technical way to resolve this conflict. It comes down to the strategy the company is pursuing. If the company is going to be the low-cost seller they have to keep their inventory costs down. If, on the other hand, the company wants to position itself as the place to come when you want it now they will have to charge a premium price and accept higher inventory costs. The process manager needs to understand the strategy the company is pursuing and then control the processes in the value chain to ensure the desired result. In most cases this will involve suboptimizing some departmental processes to make others perform as desired. This sets up a natural conflict between functional and process managers and can create problems when one manager tries to perform both roles.

If we had to choose the one thing that distinguishes a process manager from a functional manager it would be the process manager’s concern for the way his or her process fits with other processes and contributes to the overall efficiency of the value chain. This is especially marked by the process manager’s concern with the inputs to his or her process and with ensuring that the outputs of his or her process are what the downstream or “customer” process needs.

Functional or Process Management?

As we have already seen, at lower levels in the organization it’s quite common for a single manager to function as both a unit and a process manager. At higher levels, however, it becomes harder to combine the two roles. Thus, when an organization considers its overall management organizational structure, the organization often debates the relative advantages of an emphasis on functional or process management. Figure 6.7 illustrates a simple organization that has two value chains, one that produces and sells widgets and another that sells a totally different type of product, smidgets. This makes it easy to see how the concerns of functional managers differ from process managers. The head of the sales department is interested in maintaining a sales organization. He or she hires salespeople according to sales criteria, trains salespeople, and evaluates them. Broadly, from the perspective of the head of sales, selling widgets and selling smidgets is the same process, and he wants to be sure that the selling process is implemented as efficiently as possible. The VP for the widget process, on the other hand, is concerned with the entire widget value chain and is primarily concerned that the widget sales and service processes work together smoothly to provide value to widget customers. The widget process manager would be happy to change the way the sales process functions if it would, in conjunction with the other widget processes, combine to provide better service to widget customers.

Thus, although it’s possible for one individual to serve as both a unit and a process manager, it’s a strain. Without some outside support from someone who emphasizes process it’s almost impossible.

Matrix Management

Having defined functional and process management let’s consider how an organization might combine the strengths of the two approaches at the top of the organization. Recently, leading organizations have begun to establish some kind of process management hierarchy that, at least at the upper level, is independent of the organization’s functional hierarchy. The top position in a process hierarchy is a manager who is responsible for an entire value chain. Depending on the complexity of the organization the value chain manager might have other process managers reporting to him or her. This approach typically results in a matrix organization like the one pictured in Figure 6.8.

In Figure 6.8 we show a company like the one pictured earlier with three functional units. In this case, however, another senior manager has been added, and this individual is responsible for the success of the widget value chain. Different organizations allocate authority in different ways. For example, the widget process manager may function only in an advisory capacity. In this case he or she would convene meetings to discuss the flow of the Widget value chain. In such a situation the sales supervisor would still owe his or her primary allegiance to the VP of sales, and that individual would still be responsible for paying, evaluating, and promoting the sales supervisor. Key to making this approach work is to think of the management of the widget value chain as a team effort. In effect, each supervisor with management responsibility for a process that falls inside the widget value chain is a member of the widget value chain management team.

Other companies give the widget value chain manager more responsibility. In that case the sales supervisor might report to both the widget value chain manager and to the VP of sales. Each senior manager might contribute to the sales supervisor’s evaluations and each might contribute to the individual’s bonus, and so forth.

Figure 6.9 provides a continuum that is modified from one originally developed by the Project Management Institute (PMI). PMI proposed this continuum to contrast organizations that focused on functional structures and those that emphasized projects. We use it to compare functional and process organizations. In either case the area between the extremes describes the type of matrix organization that a given company might institute.

The type of matrix an organization has is determined by examining the authority and the resources that senior management allocates to specific managers. For example, in a weak matrix organization functional managers might actually “own” the employees, have full control over all budgets and employee incentives, and deal with all support organizations. In this situation the process manager would be little more than the team leader who gets team members to talk about problems and tries to resolve problems by means of persuasion.

In the opposite extreme the process manager might “own” the employees and control their salaries and incentives. In the middle, which is more typical, the departmental head would “own” the employees and have a budget for them. The process manager might have control of the budget for support processes, like IT, and have money to provide incentives for employees. In this case employee evaluations would be undertaken by both the departmental and the project manager, each using their own criteria.

Most organizations seem to be trying to establish a position in the middle of the continuum. They keep the functional or departmental units to oversee professional standards within disciplines and to manage personnel matters. Thus the VP of sales is probably responsible for hiring the sales supervisor shown in Figure 6.8 and for evaluating his or her performance and assigning raises and bonuses. The VP of sales is responsible for maintaining high sales standards within the organization. On the other hand, the ultimate evaluation of the sales supervisor comes from the SVP of the widget process. The sales supervisor is responsible for achieving results from the widget sales process and that is the ultimate basis for his or her evaluation. In a sense the heads of departments meet with the SVP of the widget process and form a high-level process management team.

Management of Outsourced Processes

The organization of managers is being complicated in many companies by outsourcing. Reconsider Figure 3.6 in which we described how Dell divides its core processes from those it outsources. Dell currently designs new computers that can be manufactured by readily available components. It markets its computers in a variety of ways and sells them by means of a website that lets users configure their own specific models. Once a customer has placed an order Dell transfers the information to an outsourcer in Asia. The components, created by still other outsourcers, are available in a warehouse owned and operated by the outsourcer, and the computers are assembled and then delivered by the outsourcer. If, after delivery, the computer needs repairs it is picked up by an outsourced delivery service and repaired in a warehouse operated by the outsourcer, then returned to the owner.

Leaving aside the issues involved in describing a value chain that are raised when a company outsources what have traditionally been considered core processes—Dell, after all, is usually classified as a computer equipment manufacturer—consider the management issues raised by this model. Dell isn’t doing the manufacturing or the distribution. The outsourcer is managing both those processes with its own management team. On the other hand, Dell certainly needs to indirectly manage those processes, since its overall success depends on providing a customer with a computer within 2–3 days of taking the customer’s order. In effect, Dell does not need to manage the traditional functional aspects of its PC/desktop-manufacturing process, but it does need to manage the process as a whole. This situation, and many variations on this theme, is driving the transition to more robust process management.

Value Chains and Process Standardization

One other trend in process management needs to be considered. When we discussed the types of alignment that companies might seek to document we mentioned that the identification of standard processes was a popular goal. In effect, if a company is doing the same activity in many different locations, it should consider doing them in the same way. A trivial example would be obtaining a credit card approval. This occurs when a customer submits a credit card and the salesperson proceeds to swipe it through a “reader” and then waits for approval and a sales slip to be printed. The flow we described depends on software that transmits information about the credit card to the credit card approval agency and returns the information needed to generate the sales slip. Doing this process in a standard way reduces employee training, simplifies reporting requirements, and makes it easier to move employees between different operations, all things that make the company more agile and efficient. Doing it with the same software reduces the need to develop or buy new software. If an enterprise resource planning (ERP) application is used, then a standardized process reduces the cost of updating the packaged software module and ensures that the same ERP module can be used everywhere credit card approval is undertaken.

Many companies installed ERP applications without first standardizing processes. This resulted in ERP modules that were tailored in different ways to support different specific processes. When the basic ERP module is updated this means that the new module has to be tailored again for each different specific process that it supports. If all the processes are standardized this will greatly reduce the cost of developing and maintaining the organization’s ERP applications. Thus several large companies have launched programs designed to identify and standardize processes throughout the organizations.

Most companies, when they set about standardizing their processes, structure the effort by establishing a process management organizational structure. Thus they create a matrix organization and assign individuals to manage “standard process areas.” These individuals (process managers) are then asked to look across all the departments in the firm and identify all the places where activities are undertaken that might be standardized. Figure 6.10 shows the matrix developed in the course of one such effort.

In Figure 6.10 we have turned the traditional functional organization on its side, so that the company’s divisions and departments run from left to right. Across the top we picture the process managers and show how their concerns cut across all the divisions and departments. At first glance this might seem like a matrix organization that organizes around functional units and processes. Consider, however, that the company has more than one value chain. One division sells commodity items to hospitals while another builds refinery plants, which it then sells to other organizations. These activities are so different that they have to be separate value chains. If we are to follow Porter and Rummler we will seek to integrate all the processes within a single value chain around a single strategy to ensure that the value chain as a whole is as efficient as possible. To achieve this the ultimate process manager is the manager responsible for the entire value chain. In the example shown in Figure 6.10 the division manager responsible for the customer refinery engineering division is better positioned to pursue that goal than the sales process manager. Similarly, the division manager responsible for hospital products is better positioned to optimize the hospital product value chain than the sales process manager.

The sales process manager in Figure 6.10 is well positioned to examine all the sales processes in all the divisions and departments and find common processes. The company’s goal in creating this matrix was to standardize their ERP applications. If the process manager is careful and focuses on lower level processes, like credit card approval, then he or she will probably be able to identify several processes that can be usefully standardized. On the other hand, if the sales process manager seeks to standardize the overall sales processes he or she runs the risk of suboptimizing all the value chains. It’s to avoid this situation that we recommend beginning by identifying the organization’s value chains and then organizing process work around specific value chains. We certainly understand the value in identifying standard processes that can be automated by standard software modules, but it is an effort that needs to be subordinated to the goal of optimizing and integrating the organization’s value chains. Otherwise this becomes an exercise in what Porter terms operational effectiveness—a variation on the best practices approach—that seeks to improve specific activities without worrying about how they fit together with other activities to create a value chain that will give the company a long-term competitive advantage.

Setting Goals and Establishing Rewards for Managers

Managers, like everyone else, need to have goals to focus their efforts. Moreover, in business situations managers will predictably try to accomplish the goals they are rewarded for achieving. Rewards can take many forms: being told that you did a good job, getting a raise, knowing you are likely to get promoted, or receiving a significant bonus. The key point, however, is that a well-run organization sets clear goals for its managers and rewards effective performance. If the goals aren’t clear, or if a given manager is asked to simultaneously pursue multiple, conflicting goals, then suboptimal performance will invariably result. In examining defective processes it is common to find managers who are being rewarded for activities that are detrimental to the success of the process. This sounds absurd, but it is so common that experienced process analysts always check for it.

Does the organization really want more sales, and does it motivate the sales manager in every way it can? Or does it want sales reports turned in on time, and does it reward the sales manager who always gets his or her reports in on time while criticizing the sales manager who achieves more sales for failing to submit the reports? We remember working on a call center process where the management wanted the agents to try to cross-sell hotel stays to people who called to ask about airline flights. One group worried that, despite training and posters in the call center, few hotel stays were being sold. A closer examination showed that the call center supervisor was rewarded for keeping the number of operators at a minimum. That was achieved by keeping each phone call as short as possible. The time operators talked to customers was carefully recorded, and operators who handled more calls in any given period were rewarded and praised. Those who spent more time on their calls—trying to sell hotel stays, for example—were criticized. There were no compensating rewards for selling hotel stays, so predictably no hotel stays were being sold.

When we consider the analysis of specific processes we will see that it is important to carefully analyze each manager’s goals and motivation. If a process is to succeed, then we need to be sure the manager’s goals and rewards are in line with the goals of the process. Thus, just as it is important to have a management system that focuses on integrating and managing processes, it is important to see that there is a system for aligning the goals and rewards given to specific managers with the goals of the processes that they manage. We’ll consider performance measurement and then return to a discussion of how an organization can align measurement and manager evaluation.

Management Processes

A company could analyze each manager’s work from scratch using our generic management model. Increasingly, however, companies find it more efficient to rely on one or more generic models that help analysts identify the specific management processes that effective process managers need to master. Let’s quickly review some of the frameworks and maturity models that are currently popular. We’ll start with the PMI Project Management Maturity Model and then consider the Software Engineering Institute’s (SEI) Capability Maturity Model Integrated (CMMI) model, the Supply Chain Council’s (SCC) Supply Chain Operations Reference (SCOR) business framework, and the IT Governance Institute’s (ITGI) COBIT (control objectives for information and related technology) framework.

PMI’s Project Management Maturity Model

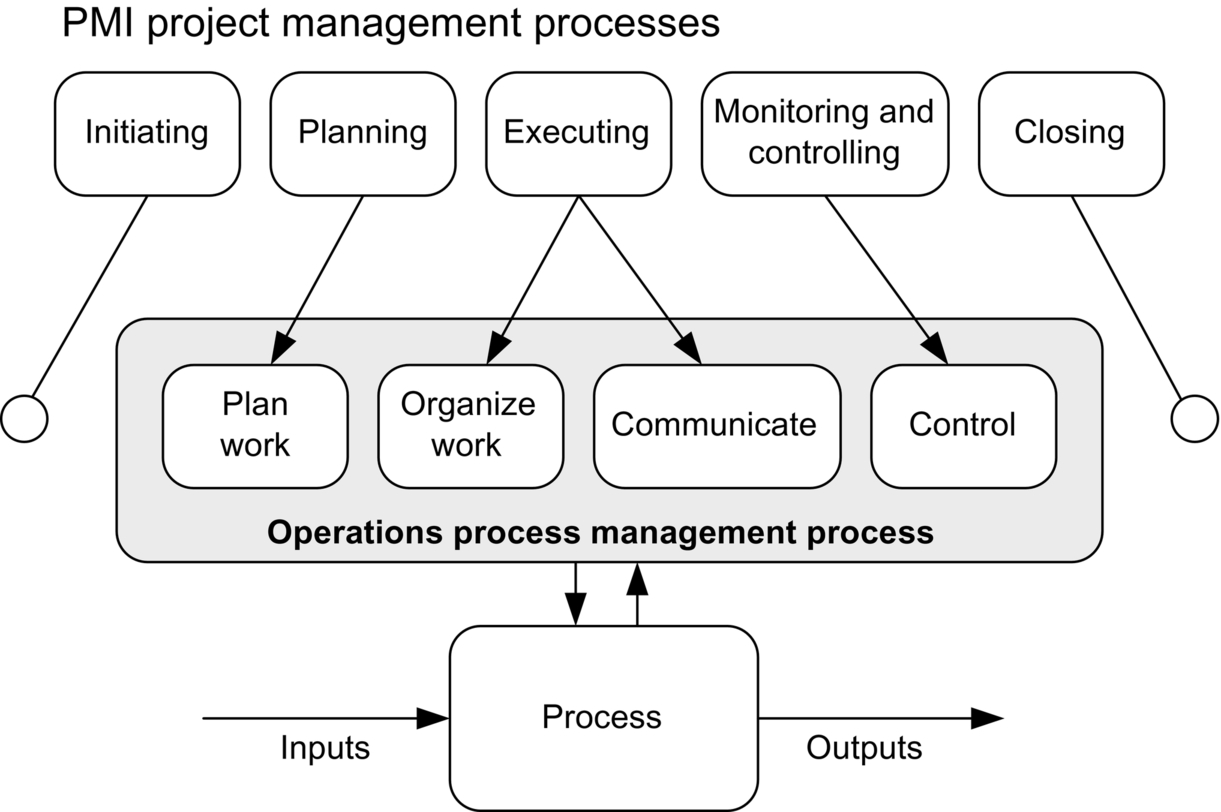

PMI distinguishes between operations management (ongoing) and project management (done in a limited timeframe). They describe a body of knowledge about project management (PMBOK) and an Organizational Project Management Maturity Model (OPM3) that organizations can use to (1) evaluate their current sophistication in managing projects and then use as (2) a methodology for introducing more sophisticated project management skills. In their PMBOK and in the OPM3 they assume that there are five management processes that every project manager must learn. They include (1) initiating, (2) planning, (3) executing, (4) monitoring and controlling, and (5) closing. Figure 6.11 suggests how the skills involved in each of these processes map to our general overview of management.

Our general model of management (Figure 6.6) pictures an operational management role and describes the activities that a process manager must perform. Project management extends that by adding a process for defining the nature of the specific project to be managed (initiating) and another that critiques the project and pulls together things that were learned in the course of the project (closing).

SEI’s CMMI Model

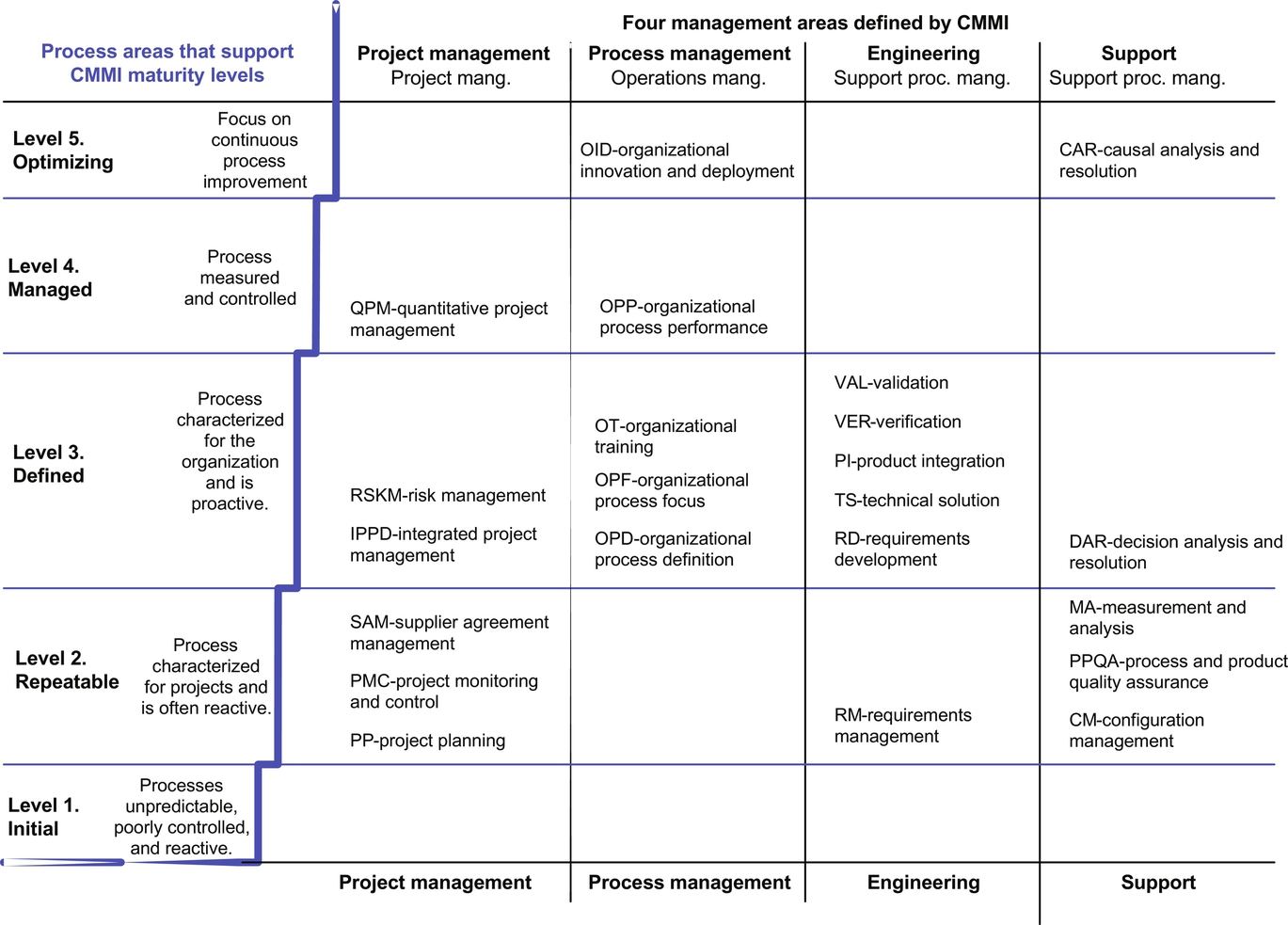

The best known of all the process maturity models is the SEI’s CMMI, which we discussed in some detail in the Introduction. Although CMM was originally developed to evaluate IT departments, the extended version CMMI is designed to help companies evaluate and improve any type of business process. CMMI supports two ways of organizing your effort. You can either analyze the capabilities of a given department or group of practitioners or you can focus on the overall maturity of an organization. The first, which focuses on capability levels, looks to see what skills are present and then focuses on teaching managers or process practitioners the skills that are missing. The second, which focuses on maturity levels, assumes that organizations become more process savvy in a systematic, staged manner and focuses on identifying the state the organization is at now and then providing the skills the organization needs to move to the next higher stage. Obviously, if you focus on organizational maturity, then CMMI functions as an enterprise process improvement methodology that provides a prescription for a sequence of process-training courses designed to provide process managers with the skills they need to manage their process more effectively. If you focus on the individual work unit and emphasize capabilities, then CMMI provides a set of criteria to use to evaluate how sophisticated specific process managers are and to determine what management processes they need to master to more effectively manage the specific process you are trying to improve.

No matter which approach you use, once the basic evaluation is complete the focus is on either the management processes that need to be acquired by the organization’s managers or on the activities needed by individuals who are responsible for improving the organization’s existing processes.

Although CMMI doesn’t place as much emphasis on types of management as we might one way they organize their processes is based on the type of manager who will need to master the process. Thus they define some management processes for operations managers (which they term process management), a second set of processes for project managers, and a third set for engineering and support managers who manage enabling or support processes. Figure 6.12 shows how CMMI would define the various management processes and shows at what organizational maturity level company managers would normally require the ability to use those processes. It will help to understand the CMMI classification if you keep in mind that day-to-day operational managers need to manage routine improvements in processes, but that major changes are undertaken as projects and that a business process management group that maintained an architecture or provided process consultants (black belts) to a specific project effort would be a support group. Put a different way, CMMI’s focus is on improving processes, but their major assumption is that processes are improved as they are defined, executed consistently, measured, and as a result of measurement systematically improved. Ultimately, putting these elements in place and executing them on a day-to-day basis is the responsibility of the individual who is managing the process.

Here are the definitions that CMMI provides for its process management “process areas”:

- • OPD—Organizational process definitions process. Establish and maintain a usable set of organization process assets and work environment standards.

- • OPF—Organizational process focus process. Plan, implement, and deploy organizational process improvements based on a thorough understanding of the current strengths and weaknesses of the organization’s processes and process assets.

- • OT—Organizational training process. Provide employees with the skills and knowledge needed to perform their roles effectively and efficiently. It includes identifying the training needed by the organization, obtaining and providing training to address those needs, establishing and maintaining training capability, establishing and maintaining training records, and assessing training effectiveness.

- • OPP—Organizational process performance process. Establish and maintain quantitative understanding of the performance of the organization’s set of standard processes in support of quality and process performance objectives, and to provide process performance data, baselines, and models to quantitatively manage the organization’s projects.

- • OID—Organizational innovation and deployment process. Select and deploy incremental and innovative improvements that measurably improve the organization’s processes and technologies.

If we were to map this particular subset of operational management processes to our general process management model (Figure 6.6) it would look something like what we picture in Figure 6.13. We placed numbers in front of the processes to suggest that at maturity Level 3 a manager would be expected to have the capabilities identified as (3). As the individual or organization matured and reached Level 4 you would assume the manager had mastered the (4) processes and at Level 5 he or she would have mastered the (5) processes.

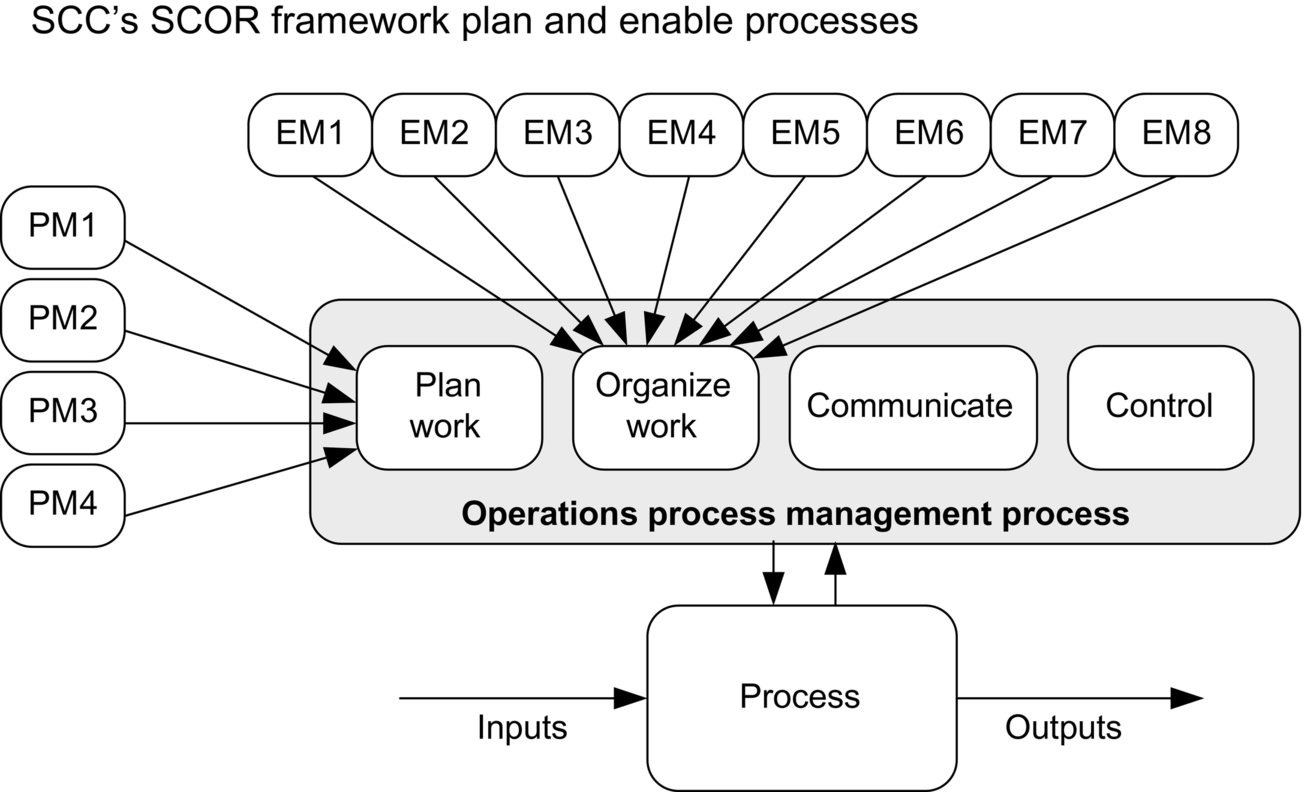

SCC’s SCOR Framework

The SCC is primarily focused on defining the core processes that make up a supply chain system. At the same time, however, they have a generic process called plan. For each supply chain process, such as source, make, deliver, or return, they require the modeler to add a plan process. In fact, they require a hierarchy of plan processes, in effect creating a picture of the process management effort required for a supply chain process. Figure 6.14 shows how SCOR analysts would model a simple supply chain. To simplify things we only show plan processes for the top row of processes. Within Alpha there are two departments, which are separated by the dashed line. Within each department there are source, make, and deliver processes. There is one plan process for each. In addition, there is one plan process for all of the plan source, plan make, and plan deliver processes within a given department.

The SCC defines four subprocesses for their plan process, which vary slightly depending on the core process they are supporting. The plan make subprocesses include:

- • PM1 Identify, Prioritize, and Aggregate Production Requirements

- • PM2 Identify, Assess, and Assign Production Resources

- • PM3 Balance Product Resources and Requirements

- • PM4 Establish Production Plans

Although they don’t picture the processes on their thread diagrams the SCC’s SCOR framework also defines an enable process and then defines enable subprocesses. Here are the eight enable make subprocesses:

- • EM1 Manage Production Rules

- • EM2 Manage Production Performance

- • EM3 Manage Production Data

- • EM4 Manage In-Process Production Inventory

- • EM5 Manage Equipment and Facilities

- • EM6 Manage Make Transportation

- • EM7 Manage Production Network

- • EM8 Manage Production Regulatory Compliance

The subprocess list reflects the more specialized role of the supply chain manager. In addition, while a lower level make process manager might not be concerned with some of these subprocesses, higher level supply chain managers would and this reflects the fact that SCOR describes not only the work of the immediate managers of a process but also considers the work that the manager’s boss will need to do.

The SCC decided to focus on management processes that are more knowledge intensive and thus didn’t include things like assigning people to tasks, monitoring output, or providing employees with feedback. An overview of how the SCOR management processes map to our general process management model (Figure 6.6) is presented in Figure 6.15.

The ITGI’s COBIT Framework

ITGI developed their process framework to organize the management of IT processes. Their high-level IT management processes map easily to our general management model (see Figure 6.16).

ITGI has defined subprocesses for each of their processes and the subprocesses also reflect our general model. Thus, for example, the ITGI subprocesses for plan and organize (PO) include:

- • PO1 Define a Strategic IT Plan

- • PO2 Define an IT Architecture

- • PO3 Define Technical Direction

- • PO4 Define IT Processes, Organization, and Relationships

- • PO5 Manage IT Investment

- • PO6 Communicate Management Aims and Directions

- • PO7 Manage IT Human Resources

- • PO8 Manage Quality

- • PO9 Manage Projects

As we look at the subprocesses we realize that the COBIT management processes are more appropriate for a CIO or a senior IT manager and not for the manager of maintain ERP applications, let alone the manager of the process to maintain ERP for accounting.

On the other hand, a review of the COBIT documentation shows that COBIT not only defines high-level IT management processes, but also defines goals for the IT organization as a whole, and then shows how different IT management processes can be linked to IT goals and proceeds to define metrics for each management process.

We have not gone into any of the various process management frameworks in any detail. For our purposes it suffices that readers should know that lots of different groups are working to define the processes that managers use when they manage specific processes. Some groups have focused on the activities, skills, and processes that a manager would need to manage an ongoing process, and others have focused on the activities, skills, and processes a manager would need to manage a project. Some have focused on the activities of senior process managers, and others have focused on managers who are responsible for very specific core processes. As we suggested earlier, defining process management is hard. Different people have pursued alternative approaches. Some simply diagnose what specific managers are doing wrong as they look for ways to improve the performance of a defective process. Others focus on the actual processes and activities that effective managers need to master to plan, organize, communicate, and monitor and control the process they are responsible for managing. Organizations that focus on managerial processes usually tend to establish process management–training programs to help their managers acquire the skills they need to perform better.

Documenting Management Processes in an Architecture

Most organizations do not document management process in their formal business process architecture. If you think of every operational process as always having an associated management process, then it seems unnecessary to document the management processes. If day-to-day management processes are documented they are usually done so as generic, standard processes that it is assumed every manager will use. If this is the company approach, then using one of the frameworks described as a source of information and definitions is a reasonable way to proceed. Most organizations identify high-level management processes that are independent of any specific value chain, and document them independently. Thus, an organization might document the strategy formulation process or the processes of a business process management support group. Others treat these specialized processes as support processes and document them in the same way they document other support processes. However your company decides to approach documentation the management processes describe sets of activities that process managers ought to master, and thus they should provide a good basis for a process manager training program.

Completing the Business Process Architecture Worksheet

Recall that the Level 1 architecture analysis worksheet provides a space at the top for the name of the manager of the value chain (see Figure 4.2). Then, below, you were asked to enter each Level 1 process, and identify the manager for each of the Level 1 processes. Then you were asked to complete a worksheet for each Level 1 process on which you listed the Level 2 processes that make up the Level 1 process, and you were asked to identify the managers responsible for each Level 2 process. In our experience most companies can identify the managers of their Level 2 or Level 3 processes without too much trouble. They have problems with identifying the managers responsible for the value chains and for the Level 1 processes. If you recall our sales supervisor in Figure 6.8, that individual was both a unit manager and a process manager, and he or she would be easy to identify in most organizations. It’s the process manager who is responsible for processes that cross the traditional boundaries that are harder to identify. In many cases they don’t exist. Yet they are the only managers who can ensure that your organization’s large-scale processes work as they should. They are the managers who focus on integrating the entire value chain and aligning the value chain with your organization’s strategy. They are the managers who are really focused on the value chain’s external measures and satisfying the customer. Most organizations are just beginning to sort through how they will manage processes at the higher levels of the organization, yet it is at these levels that huge gains are to be made and that competitive advantage is to be achieved. Ultimately, this is the work of the senior executives of your organization. If they believe in process, then this is a challenge they must address.

Notes and References

There are so many ways of classifying the basic tasks a manager must perform. I worked for a while for Louis Allen and became very familiar with his system. I’ve certainly studied Drucker, and my personal favorite is Mintzberg. And, of course, I’ve studied Geary Rummler’s papers on process management. They all segment the tasks slightly differently, but the key point is that managers undertake activities to facilitate and control the work of others.

Drucker, Peter F., Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices, Collins, 1993.

Allen, Louis Α., Principles of Professional Management (2nd ed.), Louis Allen Associates 1978. In the mid-1970s I worked briefly for Louis A. Allen, a then-popular management consultant. As far as I know, his books are no longer in print, but he introduced me to the idea that managers must plan, organize, lead, and control. I’ve simplified that in this chapter to planning and controlling.

Mintzberg, Henry, The Nature of Managerial Work, Prentice Hall, 1973.

A lot of companies tried matrix management in the 1970s and found it too difficult to coordinate, and dropped it. Most companies are doing it today—individual managers are reporting to more than one boss—but no one seems to want to call it matrix management. But there doesn’t seem to be any other popular name for the practice, so I’ve termed it matrix management.

PMI has developed an excellent framework for project management. We rely on them for their description of organizational structure, which they suggest ranges from functional to project management, with stages of matrix management in between. And we also discuss their PMI Management Maturity Model. More information is available at http://www.pmi.org. The best book for a general description of their maturity model is Bolles, Dennis L., and Darrel G. Hubbard, The Power of Enterprise-Wide Project Management, AMACOM, 2007.

Ahem, Dennis M., Aaron Clouse, and Richard Turner, CMMI Distilled: A Practical Introduction to Integrated Process Improvement (2nd ed.), Addison-Wesley, 2004. This book is the best general introduction to CMMI management processes. More information on CMMI is available at http://www.sei.cmu.edu.

Information about how the SCC’s SCOR defines plan and enable processes is available at http://www.supply-chain.org.

Information about ITGI’s COBIT framework is available at http://www.itgi.org.

There are other business process theorists who have focused on improving the management of processes. Three of the best are:

Champy, James, Reengineering Management, HarperBusiness, 1995. As with the original reengineering book this is more about why you should do it than how to do it.

Hammer, Michael, Beyond Reengineering: How the Process-Centered Organization Is Changing Our Work and Our Lives, HarperBusiness, 1997. Similar to the Champy book. Lots of inspiring stories.

Spanyi, Andrew, More for Less: The Power of Process Management, Meghan-Kiffer, 2006. This is a good, up-to-date discussion of the issues involved in managing processes from an enterprise perspective.

Information on the Chevron process management improvement effort is documented in a white paper: “Strategic Planning Helps Chevron’s E&P Optimize Its Assets,” which is available at http://www.pritchettnet.com/COmp/PI/CaseStudies/chevroncase.htm.