Rental Cars-R-Us case study

Keywords

As-Is diagram; Business Process Model and Notation (BPMN) diagram; Cause-effect diagram; Concept model; Human performance problems; Organization analysis; Policies and business rules; Problem analysis worksheet; Process management problems; Scope diagramming; Stakeholder analysis; Subprocess analysis; To-Be diagram; Use case diagram

The Rental Cars-R-Us case study is hypothetical. We did not want to describe problems associated with any specific client. At the same time we wanted a case that would give us an opportunity to cover the full range of process redesign techniques we have discussed in this part of the book. Thus we created a case study that blends the characteristics and problems faced by several companies we have worked with in the past several years. (We have never worked with a rental car company.) Similarly, we show diagrams and worksheets, although in almost all cases, when we work with actual clients, we use process modeling software tools and document our results with the tool. With those qualifications we have tried to make the case study as realistic as possible so that readers will get a good idea of the problems they will face when they seek to implement the concepts and techniques we have described.

Rental Cars-R-Us

Rental Cars-R-Us is a small car company, established initially in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. In the past 2 years, it has been acquiring other car companies in Western Canada and the United States and growing larger. Senior management is largely focused on acquisitions, franchising, and finance, but the COO is concerned with the fact that quality and consistency have decreased as the organization has grown.

There are many types of redesign projects that a company can undertake. Some involve the creation of new processes or the transformation of an existing process into some radically new process. This is not what is being asked for here. The company has a car rental process and is happy with the overall result. What it wants, instead, is for the process to be more consistent and to be smoother. So, rather than beginning with a goal of completely changing the process, we begin with the goal of making an existing process smoother and more efficient. We do not begin with a specific change in mind, but rather begin with a broad examination to determine where there are opportunities for improvement.

Rental Cars-R-Us rents cars to its customers. Customers may be individuals or companies. Different models of cars are offered and organized into groups. All cars in a group are charged at the same rates. A car may be rented by a booking made in advance or by a “walk-in” customer who simply shows up and wants to rent a car. A rental booking specifies the car group required, the start and end dates/times of the rental, and the rental branch from which the rental is to start. Optionally, the reservation may specify a one-way rental (in which the car is returned to a branch different from the pickup branch) and may request a specific car model within the required group.

The overall organization of Rental Cars-R-Us is described in the organization chart shown in Figure 14.1.

Phase 1: Understand the Project

The business process management (BPM) redesign team was established by Steve La Tour, the COO, who resides in the corporate headquarters in Vancouver. Steve is interested in what he can do to standardize practices and improve quality in all the franchise groups that the corporation deals with. Without going into details a team of seven people, including business analysts, an HR performance specialist, and an IT developer, has been assembled and placed under the direction of Mary Mahal, who is to serve as the BPM team project manager. At this point Steve, Mary, and the team are trying to establish what they will attempt to achieve in their first project.

Trying to come up with an initial description of the scope of the problem is a bit tricky because the organization has layers and manages different processes at different organizations. At the same time it is a nice illustration of the power-of-process approach. Figure 14.2 shows a simple architecture of the core, management, and support processes that the BPM redesign team worked out with Steve La Tour when they met for the second time.

There are two value chains: one that acquires customers and rents cars to them and another that establishes franchise car rental companies. In Figure 14.2 we have divided the acquire-and-rent value chain into two major streams, one focused on acquiring customers and one focused on renting cars to customers who request the service, primarily to reflect the fact that the corporate group runs the first and the franchise groups run the second. There are management processes at the corporate, operating, and local level, and there are support processes at each level as well.

The process improvement effort began when Steve La Tour asked the BPM redesign team to study one local area franchise in Calgary, Alberta, Canada. To develop a concrete understanding of the problem the process redesign team refined the task even more, and decided to focus on the airport branch of the Calgary franchise, which is one of the largest Rental Cars-R-Us branches and one that gets many complaints.

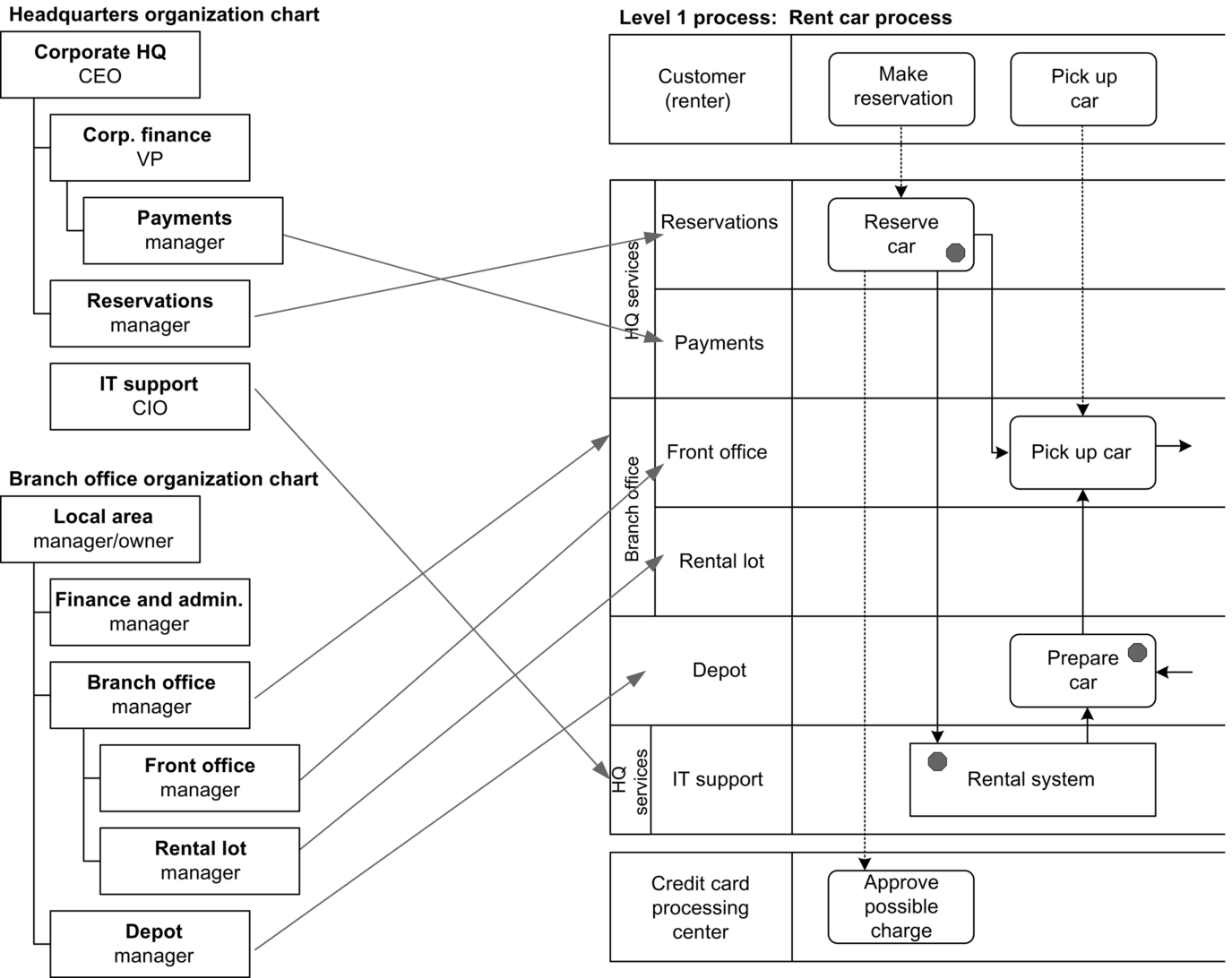

As the process redesign team pointed out, however, the overall process of renting cars was not confined to the branch and included subprocesses that occurred at the corporate HQ and at the local branch. For example, reservations were taken at a Canadian call center and then entered into a computer maintained at corporate HQ. Once a reservation is made the local franchise is notified and the information is made available on the database that franchise people can access. Looking at the architecture that the process redesign team had sketched Mr. La Tour asked the the team to focus on the rent cars process, at the Calgary airport.

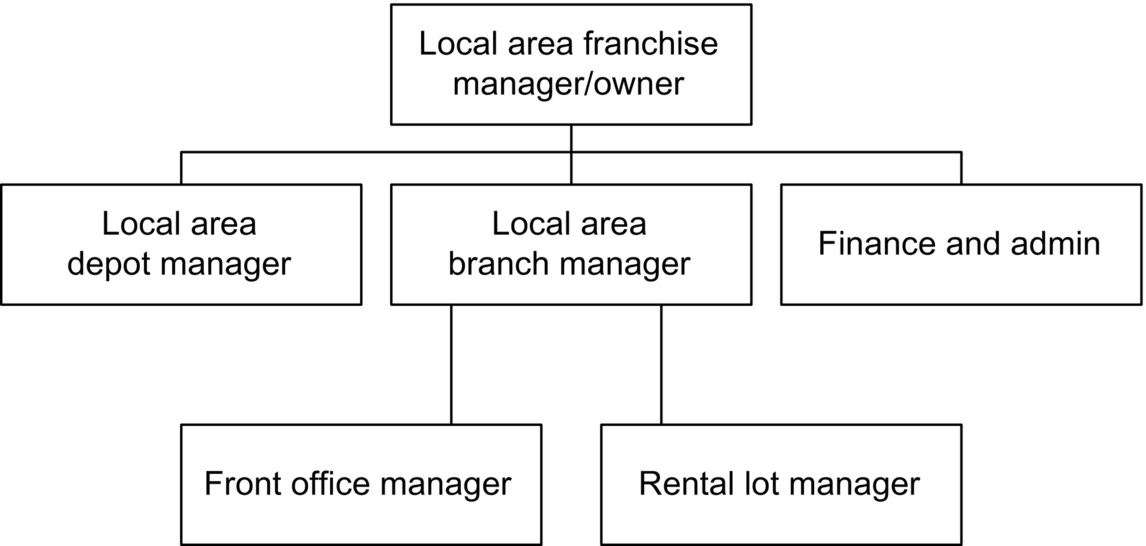

After visiting the Calgary site the process redesign team created Figure 14.3 to show the basic management organization at the local franchise branch offices.

At the same time the team sketched out the diagram in Figure 14.4 to show the value stream—rent cars—that the team decided to focus on. The team decided that the process was triggered by a request for a car, however the request originated, and concluded when the rented car had been returned and paid for, ensuring that the transaction could then be closed.

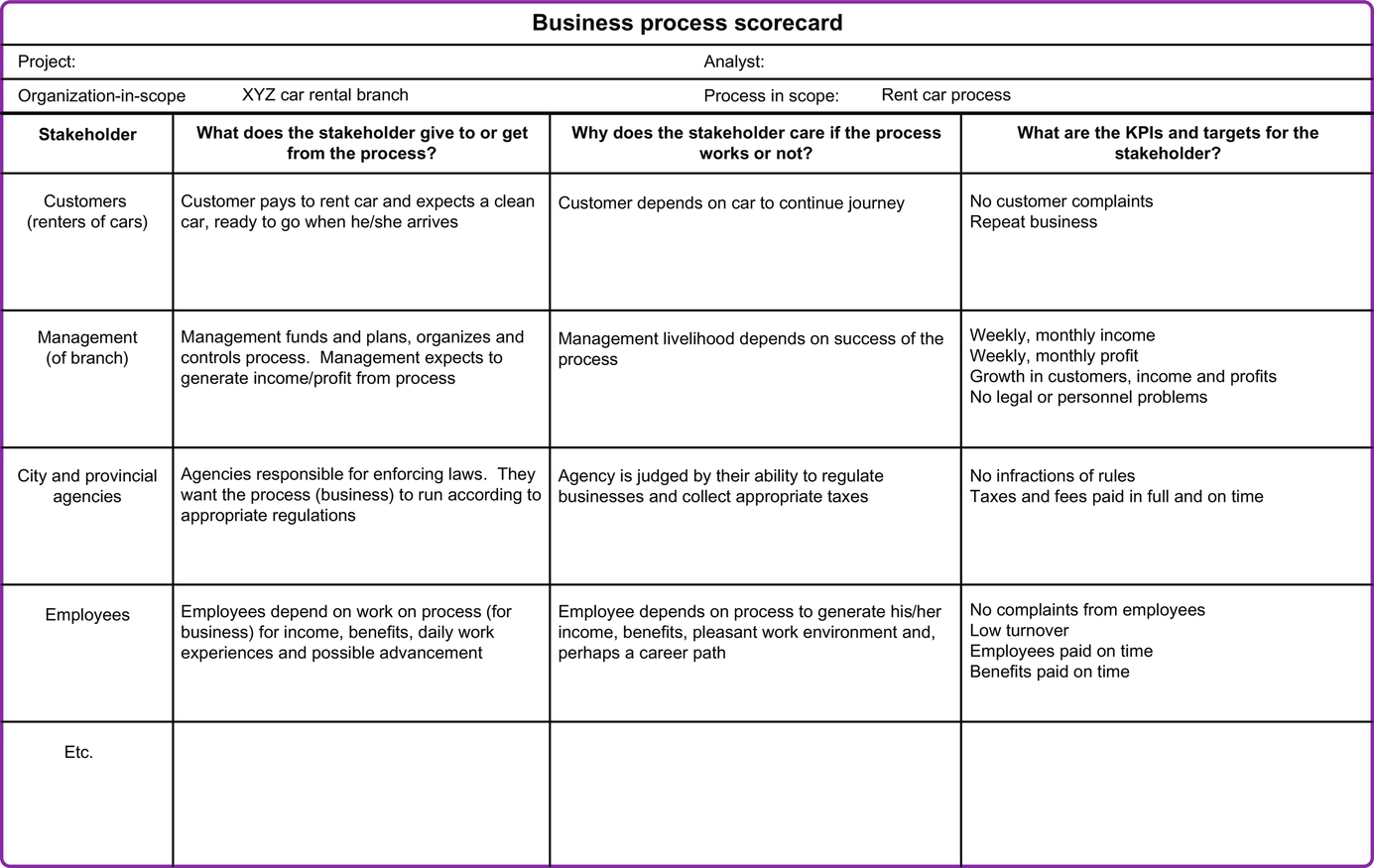

Once everyone agreed that rent cars was the process the redesign team was going to focus on the process redesign team interviewed managers and employees at the Calgary branch and proceeded to create a stakeholder diagram for the rent cars process (or value stream), which is pictured in Figure 14.5. The stakeholder diagram pictures all the individuals, groups, systems, or processes that have a major interest in whether the rent cars process works as it should. Usually, the major stakeholder is the customer—in this case the person who rents a car—but other stakeholders are also important and should not be overlooked. Management, for example, is a major stakeholder, vitally interested in the costs and the profits of the rental car franchise. (The management of the overall company is not a stakeholder in the rent cars process as such, but rather a stakeholder in the franchise itself.) A good stakeholder diagram ensures that the team is thinking about all the people the process will need to support.

As soon as the team completed the stakeholder diagram they proceeded to develop a worksheet on which they listed how each of the stakeholders would judge the success of the rent cars process. The customer, for example, wanted a car on time and in perfect condition with minimal hassle getting the car and checking it back in. Tax agencies wanted accurate reports and payments on time. Similarly, the owners and managers of the franchise operation (management) wanted accurate financial reports, a good return on their investment, and compliance with corporate policies and local rules. (The local managers in turn were responsible for reports and cashflow to the corporate management organization.) In essence, the collected concerns of the stakeholders provided the BPM team with a clear statement of the goals by which the overall success of the process might be judged.

Figure 14.6 shows a portion of the stakeholder scorecard that the process team developed for the specific franchise unit that managed the rent cars process. In conjunction with the management group responsible for company strategy and goals they developed another scorecard for the HQ group. This corporate management scorecard was later elaborated into a full-scale management tool for measuring the company’s success. In the meantime the franchise scorecard served as a source of measures to determine the success of the process improvement effort.

Next, the BPM team developed a scope diagram describing the rent cars process. They developed this diagram with a team of managers and employees from the Calgary franchise. Working with a whiteboard the group discussed all the interactions between the rent cars process and its surrounding environment. They considered individuals and organizations that interacted with the process. They also considered other processes and systems that interacted with the process. The team began by discussing inputs and outputs. They identified the nature of the input or output—telephone calls, reports, over-the-counter requests—and who originated the input or received the output. Then they considered interactions that constrained the process in one way or another—policy statements issued by corporate HQ, rules in employee manuals, or legal requirements issued by various agencies. They also considered all the resources used each time the process was executed, such as employees, facilities, databases, or software applications. Figure 14.7 shows the initial scope diagram they came up with.

After developing the initial scope diagram the team considered each interaction. They asked if it was acceptable as it was, if it could use some improvement, or if it was a real problem that had to be fixed. Several problems had been uncovered in interviews. Policies were unclear or confusing and thus clerks taking reservations on the telephone often made mistakes in completing the reservation screens. These mistakes were usually caught when renters arrived to pick up the cars, but customers still complained about the time spent revising the reservation information. Some problems slipped through, and subsequently HQ legal or finance staff sent formal complaints to local area management about incorrect reservations that put company insurance at risk. The local area staff, however, thought headquarters should make policies clearer and should program the rental system to reject reservations made incorrectly.

Problems also occurred in car setups. Occasionally, customers arrived to find their car was not set up right. A car might not have a global positioning system as ordered, or a car might be logged into the wrong slot on the lot, so a customer could not find it. Sometimes, the general maintenance of the cars was not as good as it could have been—a paper cup found in the back seat area or the gas tank not full—leading to customer complaints. The depot manager blamed the problems on poor training of the employees who carry out auto maintenance and preparation. Some of these problems—poor setups, for example—were internal problems that would not really get noticed until you looked at a flow diagram focused on the subprocesses within the rent cars process.

Clearly, the fact that reservations were often incomplete or inaccurate was a major problem. The process redesign team developed the cause-effect diagram shown in Figure 14.8 to explore the sources of incomplete and inaccurate reservations in more detail.

Figure 14.9 shows a scope diagram that has been annotated to show where problems occur, to indicate the severity of the problems, and to show what external processes might need to be examined during the analysis phase to ensure comprehensive analysis of the major problems.

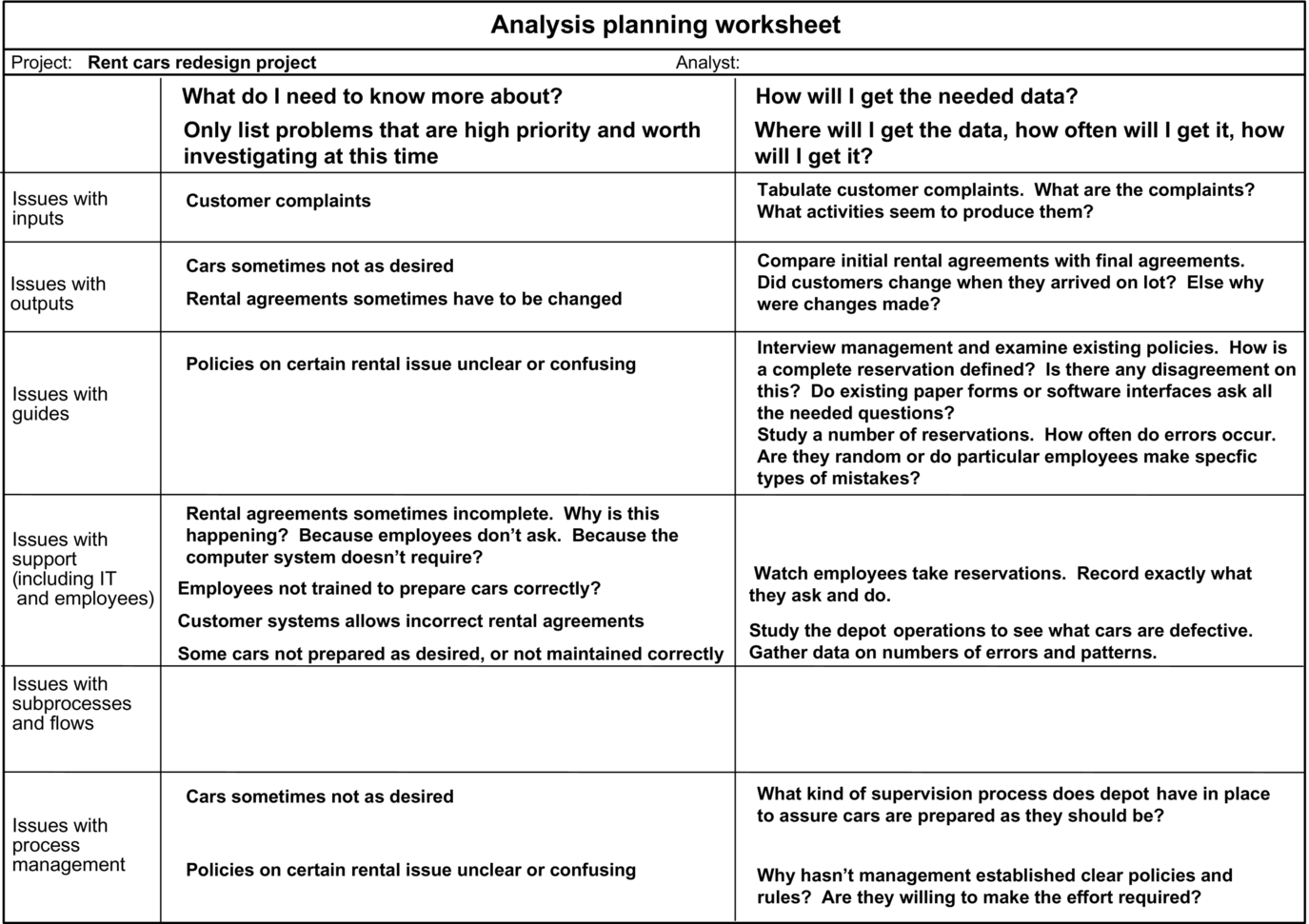

Figure 14.10 shows the problem analysis worksheet that the process redesign team completed in conjunction with the scope diagram. We normally consider six types of problems. Four of these—input problems, output problems, guide or constrain problems, and resource or enabler problems—can be analyzed by means of a scope diagram and the results of the analysis can be entered on the worksheet.

Information about the flow of subprocesses within the rent car process and internal management processes will be considered when we turn to a flow diagram that defines the internal activities of the rent car process.

Once the scope diagram and the initial problem analysis worksheet were completed the BPM team was in a good position to suggest to management what they would want to study in more detail in the analysis phase of the project. They were also in a good position to suggest to their sponsors what kinds of problems they were looking at and to make some guesses as to what kinds of solutions and what costs might be involved in redesigning the rent cars process. Their conclusions were not final at this point, but the team shared them with appropriate personnel simply to engage management in a conversation about the redesign. Good change management requires that people be kept informed and that the team develop a dialog with those whose jobs or activities might be altered. A presentation at the end of the understand phase provided a place to start and suggested where resistance might lie—which in turn helped direct the types of questions the team asked during the second phase.

Phase 2: Analyze the Business Process

In the initial phase the team seeks an overview and tries to define issues they need to explore in more detail. In essence, during the second phase the team gathers data to really understand why the problems identified by the scope diagram existed and to define how serious the problems really are.

As a generalization, when one switches from the understand phase to the analysis phase one shifts from looking at how the process interacts with its environment and begins to explore why the process functions as it does. We shift, in other words, from asking what the process is doing to asking why it is doing what it is doing. At the same time we shift from a scope diagram to a process flow diagram—which in our case usually means shifting to a Business Process Model and Notation (BPMN) diagram. Figure 14.10 pictures the first flow diagram that the process redesign team developed to try to understand the internal flow of the activities that made up or supported the rent car process. We have marked it up to emphasize several things. First, the pool that makes up the core of the BPMN diagram is equivalent to the center of the scope diagram—except that it contains the activities that occur inside the rent car process. Processes that occur outside the rent car process are shown in swimlanes above or below the rent car process pool. The swimlanes that make up the rent car process pool are labeled on the left to show who is responsible for them. Figure 14.11 highlights how we can tie management processes to the organization diagrams of the HQ and franchise operations.

In essence, when we develop a BPMN flow diagram to depict our rent car process we create a new way of looking at our process. We look inside the process we considered in the scope diagram to see how the process deals with the external inputs and outputs we considered in that diagram. Let’s shift our focus and and try to answer three questions: What activities make up the rent car process? How do activity flows pass from one activity to another? Who is responsible for managing each activity? In addition, we continue to consider some interactions between the rent car process and its external environment. If we place a customer swimlane above the rent car pool, then we can examine all the interactions between the rent car process and the customer. This is an important consideration if we are focused on how to improve customer-process interactions. In a similar way, we can place one or more suppliers or partners in swimlanes below the rent car process to allow us to show the details of those interactions.

Sometimes, when we initially draft our first BPMN diagram we place all the Level 2 processes inside a single swimlane (a pool) and just focus on getting the basic flow worked out. Later we usually divide the pool into several swimlanes to show which functional units, departments, roles, or specific managers are responsible for each of the activities. In an ideal world we should be able to trace our swimlane titles to the managers on the organization chart (Figure 14.12).

Finally, we transfer information from our scope diagram to our new BPMN diagram, using red and yellow icons to show where there are serious problems and where there are less serious problems. You will find that some trouble icons should be within activity boxes, whereas others will be better shown on the flow between processes. The key thing is to define the internal flow of the process and highlight the problem areas.

Figure 14.13 highlights a question that process redesign teams always have to consider. What level of detail should you show on any given diagram? Should you show only the default paths or should you also show the exceptions? Should you show responses from systems? There is no correct answer. You should show what makes sense to the people creating and using the diagram, and you should focus on the elements that are important for your purposes. There are no “correct” diagrams—they all simplify the complexity of reality. There are only more or less useful diagrams. If you are trying to figure out the overall order of subprocesses, then it is probably best to skip the exceptions until you are ready to focus on them.

When the BPM redesign team created their initial BPMN diagram to provide an overview of the activities and flow of the rent cars process. They also created a worksheet and documented the problems they had encountered. The worksheet listed topics they wanted to learn more about and suggested how they might gather data to help clarify the nature and extent of each possible problem (Figure 14.14).

There is no one approach to analysis. When we undertook the first phase and created a scope diagram we learned much about the types of problems we might expect as we studied the rent cars process from an external perspective. (We defined input, output, guide, and enabler problems.) We already have a worksheet that lists some problems and another that lists criteria stakeholders can use to judge the process. Our initial challenge in the analysis phase is to refine our understanding of the problems, and then proceed to diagnose the causes of various internal problems. Specifically, we will want to learn more about the external problems we have already defined, and we will want to look at how the activities, the workflow, and the management of specific activities generate the problems we have already encountered. Later, we will want to determine the salience of each problem to decide how to allocate the time and resources we will expend on fixing various problems.

In some cases a process will have obvious problems and it will be easy to see what should be done. In other cases the problems will be complex, or there will be many interacting problems and it will be harder to decide just exactly what is causing the problems or what changes will give us the biggest improvement for the effort we expend. Assuming our current process is complex and we feel a need to examine the problems from many angles we would probably follow an investigation that considered each of the following:

- • What do we ask of the customer?

- • What do we actually do, especially when we are generating problems?

- • How do employees or automated systems contribute to success or problems?

- • Is the process managed effectively?

- • Does it all flow smoothly?

All of these issues are discussed in Chapters 9 and 10. Moreover, they are summarized in Appendix 1, where we include a checklist of redesign problems to consider. Now let’s consider each point in a little more detail in the context of the rent car process.

Start With a Second Look at the Customer Process

Every organization and process team says they want to make customers happy. As we examine how the customer interacts with the process we can begin to imagine changes we might make to simplify what the customer had to go through to rent or return a car. In Figure 14.11 we highlighted the customer process. We already considered this indirectly when we developed our scope diagram, but with a BPMN diagram we can study it in more detail, looking at the actual flow of customer activities, where the customer has to wait, or where he or she might encounter problems. If we want to improve the customer’s experience we need to examine exactly what the customer has to go through to interact with our process and then consider how to improve that experience. Obviously, we cannot deal directly with the customer process—it is what the customer does. But we can certainly change the business process to make it easier for the customer to do what he or she has to do, and we can change our process to make it possible for the customer to do things in a different order. Figure 14.15 shows a diagram that pictures what happens when the customer decides to reserve a car. The BPM team worked up several diagrams like this to ensure that they understood exactly what the customer went through as he or she interacted with the company.

Because the team already knew there were problems with the reservation process they examined specific subprocesses in considerable detail. In this case the team developed a scope diagram of the reserve car subprocess (Figure 14.16). In developing the new diagram the team kept in mind that the reserve car subprocess was contained within the rent car process and would therefore use some, but not all, of the inputs, guides, outputs, and enablers used by the superprocess.

Figure 14.17 shows another way the process redesign team looked at the reserve car process. In this case they considered a variation on the normal reservation process in which a corporate travel office called to make the reservation. In this instance they were focused on what happened when the entity calling for a reservation was a corporate travel office with which Rental Cars-R-Us had an established relationship. Company policy requires Reserve Car employees notify the individual in whose name the car is reserved and thus in this case there are two customers: the entity making the reservation and the customer for whom the reservation is made.

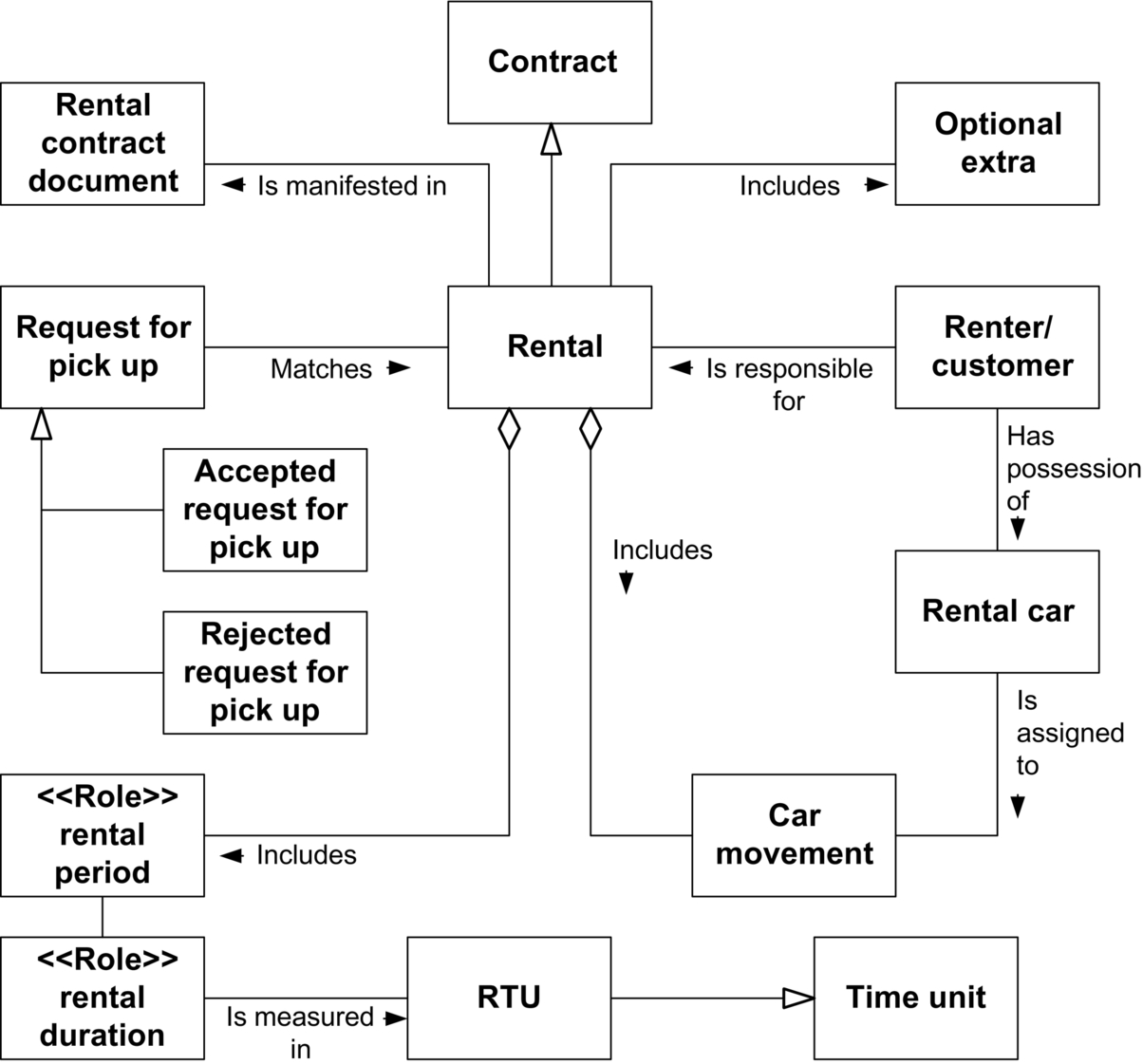

Decisions need to be made concerning the nature of reserve car activity. The BPM redesign team considered the policies and specific business rules that had already been defined to analyze and make decisions about car rentals. To define a set of rules the team needed to ensure that all the major noun phrases used to describe the rules were used in a consistent manner. Figure 14.18 shows a concept network used to define the rule vocabulary of the Rental Cars-R-Us example.

Here are some examples of business rules for Rental Cars-R-Us that use the vocabulary defined in Figure 14.18 and terms defined in other similar concept diagrams.

- • Each rental always has exactly one requested car group.

- • The duration of a rental must not be more than 90 days.

- • A driver of a rental must be a qualified driver.

- • A rental must incur a location penalty charge if the drop-off location of the rental is not the return branch of the rental.

- • The rental charge of a rental is always calculated in the business currency of the rental.

- • A rental may be open only if an estimated rental charge is provisionally charged to the credit card of the renter of the rental.

- • The fuel level of the rented car of a rental must be full at the actual start date/time of the rental.

As the team analyzed existing policies and rules they began to consider two things. First, some of the rules needed to be made more explicit. Second, the team began to see how the whole process could be automated so that customers could register for a car at a website, avoiding any misunderstandings that might arise if a clerk asked the questions.

Another process the redesign team considered in more detail was the return car subprocess. In this case the team simply created an informal expansion of the return car subprocess, showing the activities that made up the subprocess (Figure 14.19).

In each case, as we gather data, ask questions, and create more detailed BPMN diagrams, we are focused on what is done and how it is done. Each subprocess can be broken down into a set of activities. We can define output measures for each activity and then gather data to see if the activity works as we expect it to. Is the quality of the output consistent? If we are really concerned we can prepare a scope diagram for a specific activity. Or, we can define the subprocesses of a given activity and then look at how they perform. How long do different tasks take? Could we restructure the work or automate some portion of it to reduce the time it takes? Are there any unnecessary steps that we could eliminate?

As you explore the As-Is process in more detail you will probably want to decompose some of the activities. In effect, you will generate a new diagram for a single Level 2 process, showing its internal Level 3 activities. You will probably not want to do this for all the activities shown on the Level 1 process diagram, but only for those that you know have problems. Moreover, you can do it in one of two ways. You can generate another scope diagram of a Level 2 process, or you can generate a more detailed BPMN process flow diagram, depending largely on whether you think the problem lies inside the Level 2 process or in the way the Level 2 process interfaces with external stakeholders.

As the BPM redesign team explored the prepare process and maintain car process they began to ask why mistakes were made in car preparation. Figure 14.20 highlights two processes that are essentially manual and are not being done as well as they might. In these cases we want to consider the entire human performance environment to decide what intervention might be most effective. Both activities are managed by the same manager, irrespective of whoever is responsible for the specific swimlane.

As you examine any process or its subactivities, if employees are involved you need to ask how the employees are managed. Do they have clear direction and the tools they need? Do they get feedback when they are on or off target? Are there consequences for success or failure? Many employee “problems” are really management problems—and the best way to improve performance is to change the way the manager deals with the employees. It is at this point that a redesign team might consider whether creating a business process management software (BPMS) application to structure and monitor the process at runtime might improve the management of the process.

Does It All Flow Smoothly?

Finally, one looks at the sequence of activities that make up the overall process. Is the sequence logical? Is everything covered? Does the current workflow keep all employees working at about the same pace? Could some tasks be done in parallel to speed up the process? Could exceptions be handled by a separate employee to speed the flow of routine processing?

Phase 3: Redesigning the Rental Process

As with analysis, so with redesign: it can be simple, or vague and complex. In some cases you will identify specific problems and know just how to fix them. Employees do not understand how to do a specific task, and a quick training course will probably solve the problem. A specific activity is being performed that could be eliminated and save time. If the problem is simple, then redesign is usually focused on accomplishing a specific task.

At other times there are many things wrong with a process and it is unclear where you should begin. Usually, the BPM redesign team holds several brainstorming sessions to consider the problems and decide on the nature of the solution they think likely to solve most or all the problems. In the real world resources and time are always limited, and frequently a team will opt for an 80% solution, solving the most pressing problems and leaving less important problems for a later effort.

In this case the BPM redesign team decided to focus on three problems: (1) The problem customers and the organization had getting the reservation agreement right. (2) The problem the organization had getting new cars prepared as requested. (3) The problem that resulted from managers not being on top of what was happening and responding quickly enough. The solution involved a mix of initiatives, including the following:

- • Revising the rental agreement to make it easier and less ambiguous.

- • Revising the paper application, but at the same time creating a website where customers could make their own reservations. Making the same online reservation system available as an app for smartphones and digital assistants.

- • Carefully training all reservations clerks in the new agreement and associated policies.

- • Retraining depot personnel in the preparation of cars.

- • Developing a preparation quality checklist and requiring managers to check each car before placing it in a stall.

- • Developing a BPMS application to provide HQ and franchise managers with more up-to-date information on what is happening at each franchise.

If a major redesign is called for, then the first thing to consider is what the process will look like when it is redesigned. In such a case we usually begin with a To-Be diagram, a suggestion for how the new process will work. Major changes need to be sold—to management, direct (line) managers, and employees, and perhaps to partners, regulators, or customers as well. This takes time, but beginning with a clear diagram of what will change is usually a good place to start.

Figure 14.21 shows how the process redesign team marked subprocesses that were already automated or to be automated in a Could-Be redesign of the rent car process that converted the reserve cars subprocess into a website where customers could make their own reservations.

Once the BPM team decided that it wanted an automated solution—in this case a website where customers could reserve their own cars and a BPMS app for managers—the team knew that it would need to develop precise requirement specifications for the website and the BPMN app. Luckily, the BPMN diagrams that they had already prepared would be a good start for both website design and for the development of a BPMS app for managers. Figure 14.22 illustrates one of the diagrams that the team developed to identify a use case that helps define records that were created when a user requested a car.

Here is a high-level description of a use case in which the customer books a car rental:

The BPM team defined what the new To-Be process would look like, sold the concept to management and the people who performed the existing rent cars process, and defined the new training and IT resources that they would need to implement the new process. At this point the BPM team project manager began to collaborate with teams from HR and IT as they undertook the actual development of new resources. When called on the team worked with the various groups to define and test the new materials.

Phase 4: Implement the Redesigned Business Process

Implementation involves generating all the resources you require to roll out a new process. If the redesign calls for employee or managerial training someone has to develop or acquire it. If the redesign calls for new employees with different skills, they need to be hired. If the redesign calls for a new software application someone has to acquire or develop it. All these things take time and cost money. Thus it is one thing to do a new design and to get it approved. It is another thing to assemble the resources, and yet another to test and then to actually roll out the new process in the workplace.

In some cases the BPM redesign team undertakes implementation work. More commonly, they delegate it, oversee its completion, and then test that all of the resources work together as required. Thus it is common for the redesign team to let HR develop a new training program or hire new employees, and it is usual for the redesign team to let the IT department acquire or create new software applications. In all cases the BPM redesign team should be heavily involved in defining the requirements and in doing acceptance testing. If they are not, however, they should focus on preparing people in the workplace for the upcoming process changes.

Phase 5: Roll Out the New Rental Process

Rollout refers to all the tasks involved in moving, from having the resources to implement a new process to actually getting that new process up and running. It also includes incidental activities, like a review by the BPM team of its successes and failures, and their recommendations for future BPM teams to improve their work.

Let us assume that the rent car process has several changes, including new procedures for booking lease orders, new software for taking orders, new policies for preparing cars, and a BPMS app that helps the local franchise manager monitor the workflow and any problems that occur. This entire package comes with some new employee training and a class for local managers. The corporate organization installs the software and makes versions of it available to the franchises, but it also creates two teams to help local franchises launch the new process. Each team can handle one franchise a week, and so over the course of a year they roll the new process out to all the franchises, according to a schedule developed by the corporate organization. Reviewing report data at the end of the year Steve La Tour is happy with the results and convinced that the franchises are both more efficient and more consistent in the way they handle customers. The data also show that customers are much happier with the company, and La Tour is convinced that the uptick in business is largely the result of improved customer satisfaction and word of mouth about the company’s new emphasis on making customers happy.

Manage the New Rental Process

Although not part of the redesign process as such, ongoing execution of the process justifies the redesign effort. The redesign team opted to have the IT group create a BPMS app that would monitor day-to-day franchise performance and highlight problems. That provided local managers with a new tool for monitoring and controlling their work. The BPM rollout included a course for managers that described how to use the BPMS app and included instructions in how to use the information to better motivate employees. Similarly, employee training provided during the rollout encouraged employees to take more responsibility for keeping customers satisfied. One of the new activities, instituted when the new process was rolled out, was a monthly meeting when managers and employees met to deal with problems and brainstorm additional process improvements. Franchise managers reported that this has engendered a new spirit of cooperation that is focused on keeping customers happy.

Notes and References

To reiterate, Rental Cars-R-Us is a hypothetical company, not a specific company. This example is modeled on the logic defined in the Object Management Group’s adopted standard “Semantics of Business Vocabulary and Business Rules” (SBVR) (Annex E: EU-Rent Example), which is available at https://www.omg.org/. Interested readers can review the SBVR document for additional information on the logic and business rules that could be developed for this case. (In this example the rules are formatted in RuleSpeak—one of four formats supported by the OMG.)