Chapter 6

Asset Value, Policies, and Roles

THE CISSP EXAM TOPICS COVERED IN THIS CHAPTER INCLUDE:

- Information Security Governance and Risk Management

- Understand and align security function to goals, mission, and objectives of the organization

- Understand and apply security governance

- Organizational processes; define security roles and responsibilities; legislative and regulatory compliance; privacy requirements compliance; control frameworks; due care; due diligence

- Develop and implement security policy

- Security policies; standards/baselines; procedures; guidelines; documentation

- Define and implement information classification and ownership

- Ensure security in contractual agreements and procurement processes

- Understand and apply risk management concepts

- Identify threats and vulnerabilities; risk assessment/analysis; risk assignment/acceptance; countermeasure selection

- Evaluate personnel security

- Background checks and employment candidate screening; employment agreements and policies; employee termination processes; vendor, consultant and contractor controls

- Develop and manage security education, training, and awareness

- Develop and implement information system security strategies

- Support certification and accreditation efforts

- Assess the completeness and effectiveness of the security program

- Manage the security function

- Budget; metrics; resources

- Legal, Regulations, Investigations and Compliance

- Understand compliance requirements and procedures

- Regulatory environment; audits; reporting

- Understand compliance requirements and procedures

- Operations Security

- Understand the following security concepts

- Need-to-know/least privilege; separation of duties and responsibilities; monitor special privileges (e.g., operators, administrators); job rotation; marking, handling, storing, and destroying of sensitive information and media; record retention

- Understand the following security concepts

The Information Security Governance and Risk domain of the Common Body of Knowledge (CBK) for the CISSP certification exam deals with hiring practices, security roles, formalizing security structure, risk management, awareness training, and management planning.

Because of the complexity and importance of hardware and software controls, security management for employees is often overlooked in overall security planning. This chapter explores the human side of security, from establishing secure hiring practices and job descriptions to developing an employee infrastructure. Additionally, we look at how employee training, management, and termination practices are considered an integral part of creating a secure environment. Finally, we examine how to assess and manage security risks.

Employment Policies and Practices

Humans are the weakest element in any security solution. No matter what physical or logical controls are deployed, humans can discover ways to avoid them, circumvent or subvert them, or disable them. Thus, it is important to take into account the humanity of your users when designing and deploying security solutions for your environment. To understand and apply security governance, you must address the weakest link in your security chain—namely people.

Issues, problems, and compromises related to humans occur at all stages of a security solution development. This is because humans are involved throughout the development, deployment, and ongoing administration of any solution. Therefore, you must evaluate the effect users, designers, programmers, developers, managers, and implementers have on the process.

Hiring new staff typically involves several distinct steps: creating a job description, setting a classification for the job, screening candidates, and hiring and training the one best suited for the job. Without a job description, there is no consensus on what type of individual should be hired. Personnel should be added to an organization because there is a need for their specific skills and experience. Any job description for any position within an organization should address relevant security issues. You must consider items such as whether the position requires the handling of sensitive material or access to classified information. In effect, the job description defines the roles to which an employee needs to be assigned to perform their work tasks. The job description should define the type and extent of access the position requires on the secured network. Once these issues have been resolved, assigning a security classification to the job description is fairly standard.

![]()

The Importance of Job Descriptions

Job descriptions are important to the design and support of a security solution. However, many organizations either have overlooked this or have allowed job descriptions to become stale and out-of-sync with reality. Try to track down your job description. Do you even have one? If so, when was it last updated? Does it accurately reflect your job? Does it describe the type of security access you need to perform the prescribed job responsibilities?

Important elements in constructing job descriptions that are in line with organizational processes include separation of duties, job responsibilities, and job rotation.

Separation of duties Separation of duties is the security concept in which critical, significant, and sensitive work tasks are divided among several individual administrators or high-level operators. This prevents any one person from having the ability to undermine or subvert vital security mechanisms. Think of separation of duties as the application of the principle of least privilege to administrators. Separation of duties is also a protection against collusion, which is the occurrence of negative activity undertaken by two or more people, often for the purposes of fraud, theft, or espionage.

Job responsibilities Job responsibilities are the specific work tasks an employee is required to perform on a regular basis. Depending on their responsibilities, employees require access to various objects, resources, and services. On a secured network, users must be granted access privileges for those elements related to their work tasks. To maintain the greatest security, access should be assigned according to the principle of least privilege. The principle of least privilege states that in a secured environment, users should be granted the minimum amount of access necessary for them to complete their required work tasks or job responsibilities. True application of this principle requires low-level granular access control over all resources and functions.

Job rotation Job rotation, or rotating employees among numerous job positions, is simply a means by which an organization improves its overall security. Job rotation serves two functions. First, it provides a type of knowledge redundancy. When multiple employees are each capable of performing the work tasks required by several job positions, the organization is less likely to experience serious downtime or loss in productivity if an illness or other incident keeps one or more employees out of work for an extended period of time.

Second, moving personnel around reduces the risk of fraud, data modification, theft, sabotage, and misuse of information. The longer a person works in a specific position, the more likely they are to be assigned additional work tasks and thus expand their privileges and access. As a person becomes increasingly familiar with their work tasks, they may abuse their privileges for personal gain or malice. If misuse or abuse is committed by one employee, it will be easier to detect by another employee who knows the job position and work responsibilities. Therefore, job rotation also provides a form of peer auditing and protects against collusion. Job rotation is also known as cross-training.

When multiple people work together to perpetrate a crime, it’s called collusion. The likelihood that a co-worker will be willing to collaborate on an illegal or abusive scheme is reduced because of the higher risk of detection provided by the combination of separation of duties, restricted job responsibilities, and job rotation. Collusion and other privilege abuses can be reduced through strict monitoring of special privileges, such as those of an administrator, backup operator, user manager, and others.

Job descriptions are not used exclusively for the hiring process; they should be maintained throughout the life of the organization. Only through detailed job descriptions can a comparison be made between what a person should be responsible for and what they actually are responsible for. It is a managerial task to ensure that job descriptions overlap as little as possible and that one worker’s responsibilities do not drift or encroach on those of another’s. Likewise, managers should audit privilege assignments to ensure that workers do not obtain access that is not strictly required for them to accomplish their work tasks.

Screening and Background Checks

Screening candidates for a specific position is based on the sensitivity and classification defined by the job description. The sensitivity and classification of a specific position is dependent upon the level of harm that could be caused by accidental or intentional violations of security by a person in the position. Thus, the thoroughness of the screening process should reflect the security of the position to be filled.

Background checks and security clearances are essential elements in proving that a candidate is adequate, qualified, and trustworthy for a secured position. Background checks include obtaining a candidate’s work and educational history; checking references; interviewing colleagues, neighbors, and friends; checking police and government records for arrests or illegal activities; verifying identity through fingerprints, driver’s license, and birth certificate; and holding a personal interview. This process could also include a polygraph test, drug testing, and personality testing/evaluation.

Performing online background checks and reviewing the social networking accounts of applicants has become standard practice for many organizations. If a potential employee has posted inappropriate materials to their photo sharing site, social networking biographies, or public instant messaging services, then they are not as attractive a candidate as those who did not. Our actions in the public eye become permanent when those actions are recorded in text, photo, or video and then posted online. A general picture of a person’s attitude, intelligence, loyalty, common sense, diligence, honesty, respect, consistency, and adherence to social norms and/or corporate culture can be gleaned quickly by viewing a person’s online identity.

Creating Employment Agreements

When a new employee is hired, they should sign an employment agreement. Such a document outlines the rules and restrictions of the organization, the security policy, the acceptable use and activities policies, details of the job description, violations and consequences, and the length of time the position is to be filled by the employee. Many of these items may be separate documents. In such a case, the employment agreement is used to verify that the employment candidate has read and understood the associated documentation for their prospective job position.

In addition to employment agreements, there may be other security-related documentation that must be addressed. One common document is a nondisclosure agreement (NDA). An NDA is used to protect the confidential information within an organization from being disclosed by a former employee. When a person signs an NDA, they agree not to disclose any information that is defined as confidential to anyone outside the organization. Violations of an NDA are often met with strict penalties.

![]()

NCA: The NDA’s Evil Twin

The NDA has a common companion contract known as the noncompete agreement (NCA). The noncompete agreement attempts to prevent an employee with special knowledge of secrets from one organization from working in a competing organization in order to prevent that second organization from benefiting from the worker’s special knowledge of secrets. NCAs are also used to prevent workers from jumping from one company to the next just because of salary increases or other incentives. Often NCAs have a time limit, such as six months, one year, or even three years. The goal is to allow the original company to maintain its competitive edge by keeping its human resources working for its benefit rather than against it.

Many companies require new hires to sign NCAs. However, fully enforcing an NCA in court is often a difficult battle. The court recognizes the need for a worker to be able to work using the skills and knowledge they have in order to provide for themselves and their families. If the NCA would prevent reasonable income, the courts often invalidate the NCA or prevent its consequences from being realized.

Even if an NCA is not always enforceable in court, however, that does not mean it doesn’t have benefits to the original company:

- First, the threat of a lawsuit because of NCA violations is often sufficient incentive to prevent a worker from violating the terms of secrecy when they happen to move to a new company.

- Second, if a worker does violate the terms of the NCA, then even without specifically defined consequences being levied by court restrictions, the time and effort, not to mention the cost, of battling the issue in court is a deterrent.

Did you sign an NCA when you were hired? If so, do you know the terms and the potential consequences if you break that NCA?

Throughout the employment lifetime of personnel, managers should regularly audit the job descriptions, work tasks, privileges, and so on for every staff member. It is common for work tasks and privileges to drift over time. This can cause some tasks to be overlooked and others to be performed multiple times. Drifting can also result in security violations. Regularly reviewing the boundaries defined by each job description in relation to what is actually occurring aids in keeping security violations to a minimum. A key part of this review process is mandatory vacations. In many secured environments, mandatory vacations of one to two weeks are used to audit and verify the work tasks and privileges of employees. This removes the employee from the work environment and places a different worker in their position. This often results in easy detection of abuse, fraud, or negligence.

Employee Termination

When an employee must be terminated, there are numerous issues that must be addressed. A termination procedure policy is essential to maintaining a secure environment even in the face of a disgruntled employee who must be removed from the organization. The reactions of terminated employees can range from calm, understanding acceptance to violent, destructive rage. A sensible procedure for handling terminations must be designed and implemented to reduce incidents.

The termination of an employee should be handled in a private and respectful manner. However, this does not mean that precautions should not be taken. Terminations should take place with at least one witness, preferably a higher-level manager and/or a security guard. Once the employee has been informed of their release, they should be escorted off the premises and not allowed to return to their work area without an escort for any reason. Before the employee is released, all organization-specific identification, access, or security badges as well as cards, keys, and access tokens should be collected. Generally, the best time to terminate an employee is at the end of their shift midweek.

When possible, an exit interview should be performed. However, this typically depends upon the mental state of the employee upon release and numerous other factors. If an exit interview is unfeasible immediately upon termination, it should be conducted as soon as possible. The primary purpose of the exit interview is to review the liabilities and restrictions placed on the former employee based on the employment agreement, nondisclosure agreement, and any other security-related documentation.

The following list includes some other issues that should be handled as soon as possible:

- Make sure the employee returns any organizational equipment or supplies from their vehicle or home.

- Remove or disable the employee’s network user account.

- Notify human resources to issue a final paycheck, pay any unused vacation time, and terminate benefit coverage.

- Arrange for a member of the security department to accompany the released employee while they gather their personal belongings from the work area.

- Inform all security personnel and anyone else who watches or monitors any entrance point to ensure that the ex-employee does not attempt to reenter the building without an escort.

In most cases, you should disable or remove an employee’s system access at the same time or just before they are notified of being terminated. This is especially true if that employee is capable of accessing confidential data or has the expertise or access to alter or damage data or services. Failing to restrict released employees’ activities can leave your organization open to a wide range of vulnerabilities, including theft and destruction of both physical property and logical data.

![]()

Firing: Not Just a Pink Slip Anymore

Firing an employee has become a complex process. Gone are the days of placing a pink slip in an employee’s mail slot. In most IT-centric organizations, termination can create a situation in which the employee or the organization is at risk of being harmed or causing harm. That’s why you need a well-designed exit interview process.

However, just having the process isn’t enough. It has to be followed correctly every time. Unfortunately, there are many historical occurrences where this has not happened. You might even have heard of some fiasco caused by a botched termination procedure. Common examples include performing any of the following before the employee is actually informed of their termination:

- The IT department requesting the return of a notebook

- Disabling a network account

- Blocking a person’s PIN or smart card for building entrance

- Revoking a parking pass

- Distributing a company reorganization chart

- Positioning a new employee in the cubicle

- Allowing layoff information to be leaked to the media

It should go without saying that in order for the exit interview and safe termination processes to function properly, they must be implemented in the correct order and at the correct time (that is, at the start of the exit interview), as in the following example:

- Inform the person that they are relieved of their job.

- Request the return of all access badges, keys, and company equipment.

- Disable the person’s electronic access to all aspects of the organization.

- Remind the person about the NDA obligations.

- Escort the person off the premises.

A security role is the part an individual plays in the overall scheme of security implementation and administration within an organization. Security roles are not necessarily prescribed in job descriptions because they are not always distinct or static. Familiarity with security roles will help in establishing a communications and support structure within an organization. This structure will enable the deployment and enforcement of the security policy. The following six roles are presented in the logical order in which they appear in a secured environment:

Senior manager The organizational owner (senior manager) role is assigned to the person who is ultimately responsible for the security maintained by an organization and who should be most concerned about the protection of its assets. The senior manager must sign off on all policy issues. In fact, all activities must be approved by and signed off on by the senior manager before they can be carried out. There is no effective security policy if the senior manager does not authorize and support it. The senior manager’s endorsement of the security policy indicates the accepted ownership of the implemented security within the organization. The senior manager is the person who will be held liable for the overall success or failure of a security solution and is responsible for exercising due care and due diligence in establishing security for an organization. Even though senior managers are ultimately responsible for security, they rarely implement security solutions. In most cases, that responsibility is delegated to security professionals within the organization.

Security professional The security professional, information security (InfoSec) officer or computer incident response team (CIRT) role is assigned to a trained and experienced network, systems, and security engineer who is responsible for following the directives mandated by senior management. The security professional has the functional responsibility for security, including writing the security policy and implementing it. The role of security professional can be labeled as an IS/IT function role. The security professional role is often filled by a team that is responsible for designing and implementing security solutions based on the approved security policy. Security professionals are not decision makers; they are implementers. All decisions must be left to the senior manager.

Data owner The data owner role is assigned to the person who is responsible for classifying information for placement and protection within the security solution. The data owner is typically a high-level manager who is ultimately responsible for data protection. However, the data owner usually delegates the responsibility of the actual data management tasks to a data custodian.

Data custodian The data custodian role is assigned to the user who is responsible for the tasks of implementing the prescribed protection defined by the security policy and senior management. The data custodian performs all activities necessary to provide adequate protection for the CIA Triad (confidentiality, integrity, and availability) of data and to fulfill the requirements and responsibilities delegated from upper management. These activities can include performing and testing backups, validating data integrity, deploying security solutions, and managing data storage based on classification.

User The user (end user or operator) role is assigned to any person who has access to the secured system. A user’s access is tied to their work tasks and is limited so they have enough access to perform the tasks necessary for their job position (the principle of least privilege). Users are responsible for understanding and upholding the security policy of an organization by following prescribed operational procedures and operating within defined security parameters.

Auditor Another role is that of an auditor. An auditor is responsible for testing and verifying that the security policy is properly implemented and the derived security solutions are adequate. The auditor role may be assigned to a security professional or a trained user. The auditor produces compliance and effectiveness reports that are reviewed by the senior manager. Issues discovered through these reports are transformed into new directives assigned by the senior manager to security professionals or data custodians. However, the auditor is listed as the last or final role since the auditor needs a source of activity (that is, users or operators working in an environment) to audit or monitor.

All of these roles serve an important function within a secured environment. They are useful for identifying liability and responsibility as well as for identifying the hierarchical management and delegation scheme.

Security management planning ensures proper creation, implementation, and enforcement of a security policy. The most effective way to tackle security management planning is using a top-down approach. Upper, or senior, management is responsible for initiating and defining policies for the organization. Security policies provide direction for the lower levels of the organization’s hierarchy. It is the responsibility of middle management to flesh out the security policy into standards, baselines, guidelines, and procedures. The operational managers or security professionals must then implement the configurations prescribed in the security management documentation. Finally, the end users must comply with all the security policies of the organization.

![]()

The opposite of the top-down approach is the bottom-up approach. In a bottom-up approach environment, the IT staff makes security decisions directly without input from senior management. The bottom-up approach is rarely utilized in organizations and is considered problematic in the IT industry.

Security management is a responsibility of upper management, not of the IT staff, and is considered a business operations issue rather than an IT administration issue. The team or department responsible for security within an organization should be autonomous from all other departments. The InfoSec team should be led by a designated chief security officer (CSO) who must report directly to senior management. Placing the autonomy of the CSO and his team outside the typical hierarchical structure in an organization can improve security management across the entire organization. It also helps to avoid cross-department and internal political issues.

Elements of security management planning include defining security roles; prescribing how security will be managed, who will be responsible for security, and how security will be tested for effectiveness; developing security policies; performing risk analysis; and requiring security education for employees. These responsibilities are guided through the development of management plans.

The best security plan is useless without one key factor: approval by senior management. Without senior management’s approval of and commitment to the security policy, the policy will not succeed. It is the responsibility of the policy development team to educate senior management sufficiently so it understands the risks, liabilities, and exposures that remain even after security measures prescribed in the policy are deployed. Developing and implementing a security policy is evidence of due care and due diligence on the part of senior management. If a company does not practice due care and due diligence, managers can be held liable for negligence and held accountable for both asset and financial losses.

A security management planning team should develop three types of plans:

Strategic plan A strategic plan is a long-term plan that is fairly stable. It defines the organization’s goals, mission, and objectives. It’s useful for about five years if it is maintained and updated annually. The strategic plan also serves as the planning horizon. Long-term goals and visions for the future are discussed in a strategic plan. A strategic plan should include a risk assessment.

Tactical plan The tactical plan is a midterm plan developed to provide more details on accomplishing the goals set forth in the strategic plan. A tactical plan is typically useful for about a year and often prescribes and schedules the tasks necessary to accomplish organizational goals. Some examples of tactical plans include project plans, acquisition plans, hiring plans, budget plans, maintenance plans, support plans, and system development plans.

Operational plan An operational plan is a short-term, highly detailed plan based on the strategic and tactical plans. It is valid or useful only for a short time. Operational plans must be updated often (such as monthly or quarterly) to retain compliance with tactical plans. Operational plans are detailed plans that spell out how to accomplish the various goals of the organization. They include resource allotments, budgetary requirements, staffing assignments, scheduling, and step-by-step or implementation procedures. Operational plans include details on how the implementation processes are in compliance with the organization’s security policy. Examples of operational plans include training plans, system deployment plans, and product design plans.

Security is a continuous process. Thus, the activity of security management planning may have a definitive initiation point, but its tasks and work are never fully accomplished or complete. Effective security plans focus attention on specific and achievable objectives, anticipate change and potential problems, and serve as a basis for decision making for the entire organization. Security documentation should be concrete, well defined, and clearly stated. For a security plan to be effective, it must be developed, maintained, and actually used.

Policies, Standards, Baselines, Guidelines, and Procedures

For most organizations, maintaining security is an essential part of ongoing business. If their security were seriously compromised, many organizations would fail. To reduce the likelihood of a security failure, the process of implementing security has been somewhat formalized. This formalization has greatly reduced the chaos and complexity of designing and implementing security solutions for IT infrastructures. The formalization of security solutions takes the form of a hierarchical organization of documentation. Each level focuses on a specific type or category of information and issues.

Security Policies

The top tier of the formalization is known as a security policy. A security policy is a document that defines the scope of security needed by the organization and discusses the assets that need protection and the extent to which security solutions should go in order to provide the necessary protection. The security policy is an overview or generalization of an organization’s security needs. It defines the main security objectives and outlines the security framework of an organization. The security policy also identifies the major functional areas of data processing and clarifies and defines all relevant terminology. It should clearly define why security is important and what assets are valuable. It is a strategic plan for implementing security. It should broadly outline the security goals and practices that should be employed to protect the organization’s vital interests. The document discusses the importance of security to every aspect of daily business operation and the importance of the support of the senior staff for the implementation of security. The security policy is used to assign responsibilities, define roles, specify audit requirements, outline enforcement processes, indicate compliance requirements, and define acceptable risk levels. This document is often used as the proof that senior management has exercised due care in protecting itself against intrusion, attack, and disaster. Security policies are compulsory.

Many organizations employ several types of security policies to define or outline their overall security strategy. An organizational security policy focuses on issues relevant to every aspect of an organization. An issue-specific security policy focuses on a specific network service, department, function, or other aspect that is distinct from the organization as a whole. A system-specific security policy focuses on individual systems or types of systems and prescribes approved hardware and software, outlines methods for locking down a system, and even mandates firewall or other specific security controls.

In addition to these focused types of security policies, there are three overall categories of security policies: regulatory, advisory, and informative. A regulatory policy is required whenever industry or legal standards are applicable to your organization. This policy discusses the regulations that must be followed and outlines the procedures that should be used to elicit compliance. An advisory policy discusses behaviors and activities that are acceptable and defines consequences of violations. It explains the senior management’s desires for security and compliance within an organization. Most policies are advisory. An informative policy is designed to provide information or knowledge about a specific subject, such as company goals, mission statements, or how the organization interacts with partners and customers. An informative policy provides support, research, or background information relevant to the specific elements of the overall policy.

From the security policies flow many other documents or subelements necessary for a complete security solution. Policies are broad overviews, whereas standards, baselines, guidelines, and procedures include more specific, detailed information on the actual security solution. Standards are the next level below security policies.

Security Policies and Individuals

As a rule of thumb, security policies (as well as standards, guidelines, and procedures) should not address specific individuals. Instead of assigning tasks and responsibilities to a person, the policy should define tasks and responsibilities to fit a role. That role is a function of administrative control or personnel management. Thus, a security policy does not define who is to do what but rather defines what must be done by the various roles within the security infrastructure. Then these defined security roles are assigned to individuals as a job description or an assigned work task.

Acceptable Use Policy

An acceptable use policy is a commonly produced document that exists as part of the overall security documentation infrastructure. The acceptable use policy is specifically designed to assign security roles within the organization as well as ensure the responsibilities tied to those roles. This policy defines a level of acceptable performance and expectation of behavior and activity. Failure to comply with the policy may result in job action warnings, penalties, or termination.

Security Standards, Baselines, and Guidelines

Once the main security policies are set, then the remaining security documentation can be crafted under the guidance of those policies. Standards define compulsory requirements for the homogenous use of hardware, software, technology, and security controls. They provide a course of action by which technology and procedures are uniformly implemented throughout an organization. Standards are tactical documents that define steps or methods to accomplish the goals and overall direction defined by security policies.

At the next level are baselines. A baseline defines a minimum level of security that every system throughout the organization must meet. All systems not complying with the baseline should be taken out of production until they can be brought up to the baseline. The baseline establishes a common foundational secure state upon which all additional and more stringent security measures can be built. Baselines are usually system specific and often refer to an industry or government standard, like the Trusted Computer System Evaluation Criteria (TCSEC) or Information Technology Security Evaluation and Criteria (ITSEC). For example, most military organizations require that all systems support the TCSEC C2 security level at a minimum.

Guidelines are the next element of the formalized security policy structure. A guideline offers recommendations on how standards and baselines are implemented and serves as operational guides for both security professionals and users. Guidelines are flexible so they can be customized for each unique system or condition and can be used in the creation of new procedures. They state which security mechanisms should be deployed instead of prescribing a specific product or control and detailing configuration settings. They outline methodologies, include suggested actions, and are not compulsory.

Security Procedures

Procedures are the final element of the formalized security policy structure. A procedure is a detailed, step-by-step how-to document that describes the exact actions necessary to implement a specific security mechanism, control, or solution. A procedure could discuss the entire system deployment operation or focus on a single product or aspect, such as deploying a firewall or updating virus definitions. In most cases, procedures are system and software specific. They must be updated as the hardware and software of a system evolve. The purpose of a procedure is to ensure the integrity of business processes. If everything is accomplished by following a detailed procedure, then all activities should be in compliance with policies, standards, and guidelines. Procedures help ensure standardization of security across all systems.

All too often, policies, standards, baselines, guidelines, and procedures are developed only as an afterthought at the urging of a consultant or auditor. If these documents are not used and updated, the administration of a secured environment will be unable to use them as guides. And without the planning, design, structure, and oversight provided by these documents, no environment will remain secure or represent proper diligent due care.

It is also common practice to develop a single document containing aspects of all these elements. This should be avoided. Each of these structures must exist as a separate entity because each performs a different specialized function. At the top of the formalization security policy documentation structure there are fewer documents because they contain general broad discussions of overview and goals. There are more documents further down the formalization structure (in other words, guidelines and procedures) because they contain details specific to a limited number of systems, networks, divisions, and areas.

Keeping these documents as separate entities provides several benefits:

- Not all users need to know the security standards, baselines, guidelines, and procedures for all security classification levels.

- When changes occur, it is easier to update and redistribute only the affected material rather than updating a monolithic policy and redistributing it throughout the organization.

Crafting the totality of security policy and all supporting documentation can be a daunting task. Many organizations struggle just to define the foundational parameters of their security, much less detail every single aspect of their day-to-day activities. However, in theory, a detailed and complete security policy supports real-world security in a directed, efficient, and specific manner. Once the security policy documentation is reasonably complete, it can be used to guide decisions, train new users, respond to problems, and predict trends for future expansion. A security policy should not be an afterthought but a key part of establishing an organization.

Security is aimed at preventing loss or disclosure of data while sustaining authorized access. The possibility that something could happen to damage, destroy, or disclose data or other resource is known as risk.

Managing risk is therefore an element of sustaining a secure environment. Risk management is a detailed process of identifying factors that could damage or disclose data, evaluating those factors in light of data value and countermeasure cost, and implementing cost-effective solutions for mitigating or reducing risk. The overall process of risk management is used to develop and implement information security strategies. The goal of these strategies is to reduce risk and to support the mission of the organization.

The primary goal of risk management is to reduce risk to an acceptable level. What that level actually is depends upon the organization, the value of its assets, the size of its budget, and many other factors. What is deemed acceptable risk to one organization may be a completely unreasonably high level of risk to another. It is impossible to design and deploy a totally risk-free environment; however, significant risk reduction is possible, often with little effort. Risks to an IT infrastructure are not all computer based. In fact, many risks come from noncomputer sources. It is important to consider all possible risks when performing risk evaluation for an organization. Failing to properly evaluate and respond to all forms of risk, a company remains vulnerable. Keep in mind that IT security, commonly referred to as logical or technical security, can provide protection only against logical or technical attacks. To protect IT against physical attacks, physical protections must be erected.

The process by which the goals of risk management are achieved is known as risk analysis. It includes analyzing an environment for risks, evaluating each risk as to its likelihood of occurring and the cost of the damage it would cause if it did occur, assessing the cost of various countermeasures for each risk, and creating a cost/benefit report for safeguards to present to upper management. In addition to these risk-focused activities, risk management also requires evaluation, assessment, and the assignment of value for all assets within the organization. Without proper asset valuations, it is not possible to prioritize and compare risks with possible losses.

Risk Terminology

Risk management employs a vast terminology that must be clearly understood, especially for the CISSP exam. This section defines and discusses all the important risk-related terminology:

Asset An asset is anything within an environment that should be protected. It can be a computer file, a network service, a system resource, a process, a program, a product, an IT infrastructure, a database, a hardware device, furniture, product recipes/formulas, personnel, software, facilities, and so on. If an organization places any value on an item under its control and deems that item important enough to protect, it is labeled an asset for the purposes of risk management and analysis. The loss or disclosure of an asset could result in an overall security compromise, loss of productivity, reduction in profits, additional expenditures, discontinuation of the organization, and numerous intangible consequences.

Asset valuation Asset valuation is a dollar value assigned to an asset based on actual cost and nonmonetary expenses. These can include costs to develop, maintain, administer, advertise, support, repair, and replace an asset; they can also include more elusive values, such as public confidence, industry support, productivity enhancement, knowledge equity, and ownership benefits. Asset valuation is discussed in detail later in this chapter.

Threats Any potential occurrence that may cause an undesirable or unwanted outcome for an organization or for a specific asset is a threat. Threats are any action or inaction that could cause damage, destruction, alteration, loss, or disclosure of assets or that could block access to or prevent maintenance of assets. Threats can be large or small and result in large or small consequences. They can be intentional or accidental. They can originate from people, organizations, hardware, networks, structures, or nature. Threat agents intentionally exploit vulnerabilities. Threat agents are usually people, but they could also be programs, hardware, or systems. Threat events are accidental and intentional exploitations of vulnerabilities. Threat events can also be natural or manmade. Threat events include fire, earthquake, flood, system failure, human error (due to a lack of training or ignorance), and power outages.

Vulnerability The weakness in an asset or the absence or the weakness of a safeguard or countermeasure is a vulnerability.

In other words, a vulnerability is a flaw, loophole, oversight, error, limitation, frailty, or susceptibility in the IT infrastructure or any other aspect of an organization. If a vulnerability is exploited, loss or damage to assets can occur.

Exposure Exposure is being susceptible to asset loss because of a threat; there is the possibility that a vulnerability can or will be exploited by a threat agent or event. Exposure doesn’t mean that a realized threat (an event that results in loss) is actually occurring (the exposure to a realized threat is called experienced exposure). It just means that if there is a vulnerability and a threat that can exploit it, there is the possibility that a threat event, or potential exposure, can occur.

Risk Risk is the possibility or likelihood that a threat will exploit a vulnerability to cause harm to an asset. It is an assessment of probability, possibility, or chance. The more likely it is that a threat event will occur, the greater the risk. Every instance of exposure is a risk. When written as a formula, risk can be defined as risk = threat * vulnerability. Thus, reducing either the threat agent or the vulnerability directly results in a reduction in risk.

When a risk is realized, a threat agent or a threat event has taken advantage of a vulnerability and caused harm to or disclosure of one or more assets. The whole purpose of security is to prevent risks from becoming realized by removing vulnerabilities and blocking threat agents and threat events from jeopardizing assets. As a risk management tool, security is the implementation of safeguards.

Safeguards A safeguard, or countermeasure, is anything that removes or reduces a vulnerability or protects against one or more specific threats. A safeguard can be installing a software patch, making a configuration change, hiring security guards, altering the infrastructure, modifying processes, improving the security policy, training personnel more effectively, electrifying a perimeter fence, installing lights, and so on. It is any action or product that reduces risk through the elimination or lessening of a threat or a vulnerability anywhere within an organization. Safeguards are the only means by which risk is mitigated or removed. It is important to remember that a safeguard, security control, or countermeasure need not be the purchase of a new product; reconfiguring existing elements or even removing elements from the infrastructure are also valid safeguards.

Attack An attack is the exploitation of a vulnerability by a threat agent. In other words, an attack is any intentional attempt to exploit a vulnerability of an organization’s security infrastructure to cause damage, loss, or disclosure of assets. An attack can also be viewed as any violation or failure to adhere to an organization’s security policy.

Breach A breach is the occurrence of a security mechanism being bypassed or thwarted by a threat agent. When a breach is combined with an attack, a penetration, or intrusion, can result. A penetration is the condition in which a threat agent has gained access to an organization’s infrastructure through the circumvention of security controls and is able to directly imperil assets.

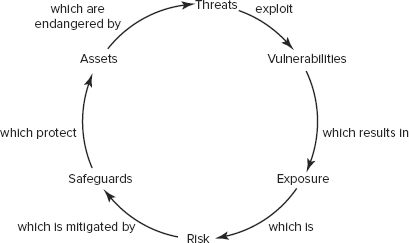

The elements asset, threat, vulnerability, exposure, risk, and safeguard are related, as shown in Figure 6.1. Threats exploit vulnerabilities, which results in exposure. Exposure is risk, and risk is mitigated by safeguards. Safeguards protect assets that are endangered by threats.

FIGURE 6.1 The elements of risk

Risk Assessment Methodologies

Risk management/analysis is primarily an exercise for upper management. It is their responsibility to initiate and support risk analysis and assessment by defining the scope and purpose of the endeavor. The actual processes of performing risk analysis are often delegated to security professionals or an evaluation team. However, all risk assessments, results, decisions, and outcomes must be understood and approved by upper management as an element in providing prudent due care.

All IT systems have risk. There is no way to eliminate 100 percent of all risks. Instead, upper management must decide which risks are acceptable and which are not. Determining which risks are acceptable requires detailed and complex asset and risk assessments.

Risk Analysis

Risk analysis is performed to provide upper management with the details necessary to decide which risks should be mitigated, which should be transferred, and which should be accepted. The result is a cost/benefit comparison between the expected cost of asset loss and the cost of deploying safeguards against threats and vulnerabilities. Risk analysis identifies risks, quantifies the impact of threats, and aids in budgeting for security. Risk analysis helps integrate the needs and objectives of the security policy with the organization’s business goals and intentions. The risk analysis/risk assessment is a “point in time” metric. Threats and vulnerabilities constantly change, and the risk assessment need to be redone periodically.

The first step in risk analysis is to appraise the value of an organization’s assets. If an asset has no value, then there is no need to provide protection for it. A primary goal of risk analysis is to ensure that only cost-effective safeguards are deployed. It makes no sense to spend $100,000 protecting an asset that is worth only $1,000. The value of an asset directly affects and guides the level of safeguards and security deployed to protect it. As a rule, the annual costs of safeguards should not exceed the expected annual cost of asset loss.

Asset Valuation

When the cost of an asset is evaluated, there are many aspects to consider. The goal of asset evaluation is to assign a specific dollar value to it that encompasses tangible costs as well as intangible ones. Determining an exact value is often difficult if not impossible, but nevertheless, a specific value must be established. (Note that the discussion of qualitative vs. quantitative risk analysis in the next section may clarify this issue.) Improperly assigning value to assets can result in failing to properly protect an asset or implementing financially infeasible safeguards. The following list includes some of the issues that contribute to the valuation of assets:

- Purchase cost

- Development cost

- Administrative or management cost

- Maintenance or upkeep cost

- Cost in acquiring asset

- Cost to protect or sustain asset

- Value to owners and users

- Value to competitors

- Intellectual property or equity value

- Market valuation (sustainable price)

- Replacement cost

- Productivity enhancement or degradation

- Operational costs of asset presence and loss

- Liability of asset loss

- Usefulness

Assigning or determining the value of assets to an organization can fulfill numerous requirements. It serves as the foundation for performing a cost/benefit analysis of asset protection through safeguard deployment. It serves as a means for selecting or evaluating safeguards and countermeasures. It provides values for insurance purposes and establishes an overall net worth or net value for the organization. It helps senior management understand exactly what is at risk within the organization. Understanding the value of assets also helps to prevent negligence of due care and encourages compliance with legal requirements, industry regulations, and internal security policies.

After asset valuation, threats must be identified and examined. This involves creating an exhaustive list of all possible threats for the organization and its IT infrastructure. The list should include threat agents as well as threat events. It is important to keep in mind that threats can come from anywhere. Threats to IT are not limited to IT sources. When compiling a list of threats, be sure to consider the following:

- Viruses

- Cascade errors and dependency faults

- Criminal activities by authorized users

- Movement (vibrations, jarring, etc.)

- Intentional attacks

- Reorganization

- Authorized user illness or epidemics

- Hackers

- User errors

- Natural disasters (earthquakes, floods, fire, volcanoes, hurricanes, tornadoes, tsunamis, and so on)

- Physical damage (crushing, projectiles, cable severing, and so on)

- Misuse of data, resources, or services

- Changes or compromises to data classification or security policies

- Government, political, or military intrusions or restrictions

- Processing errors, buffer overflows

- Personnel privilege abuse

- Temperature extremes

- Energy anomalies (static, EM pulses, radio frequencies [RFs], power loss, power surges, and so on)

- Loss of data

- Information warfare

- Bankruptcy or alteration/interruption of business activity

- Coding/programming errors

- Intruders (physical and logical)

- Environmental factors (presence of gases, liquids, organisms, and so on)

- Equipment failure

- Physical theft

- Social engineering

In most cases, a team rather than a single individual should perform risk assessment and analysis. Also, the team members should be from various departments within the organization. It is not usually a requirement that all team members be security professionals or even network/system administrators. The diversity of the team based on the demographics of the organization will help to exhaustively identify and address all possible threats and risks.

The Consultant Calvary

Risk assessment is a highly involved, detailed, complex, and lengthy process. Often risk analysis cannot be properly handled by existing employees because of the size, scope, or liability of the risk; thus, many organizations bring in risk management consultants to perform this work. This provides a high level of expertise, does not bog down employees, and can prove to be a more reliable measurement of real-world risk. But even risk management consultants do not perform risk assessment and analysis on paper only; they typically employ complex and expensive risk assessment software. This software streamlines the overall task, provides more reliable results, and produces standardized reports that are acceptable to insurance companies, boards of directors, and so on.

Once you develop a list of threats, you must individually evaluate each threat and its related risk. There are two risk assessment methodologies: quantitative and qualitative. Quantitative risk analysis assigns real dollar figures to the loss of an asset. Qualitative risk analysis assigns subjective and intangible values to the loss of an asset. Both methods are necessary for a complete risk analysis.

Quantitative Risk Analysis

The quantitative method results in concrete probability percentages. That means it creates a report that has dollar figures for levels of risk, potential loss, cost of countermeasures, and value of safeguards. This report is usually fairly easy to understand, especially for anyone with knowledge of spreadsheets and budget reports. Think of quantitative analysis as the act of assigning a quantity to risk, in other words, placing a dollar figure on each asset and threat. However, a purely quantitative analysis is not possible; not all elements and aspects of the analysis can be quantified because some are qualitative, subjective, and some are intangible. The process of quantitative risk analysis starts with asset valuation and threat identification. Next, you estimate the potential and frequency of each risk. This information is then used to calculate various cost functions that are used to evaluate safeguards.

The six major steps or phases in quantitative risk analysis are as follows:

1. Inventory assets, and assign a value (AV).

2. Research each asset, and produce a list of all possible threats of each individual asset. For each listed threat, calculate the exposure factor (EF) and single loss expectancy (SLE).

3. Perform a threat analysis to calculate the likelihood of each threat being realized within a single year, that is, the annualized rate of occurrence (ARO).

4. Derive the overall loss potential per threat by calculating the annualized loss expectancy (ALE).

5. Research countermeasures for each threat, and then calculate the changes to ARO and ALE based on an applied countermeasure.

6. Perform a cost/benefit analysis of each countermeasure for each threat for each asset. Select the most appropriate response to each threat.

Cost Functions

The cost functions associated with quantitative risk analysis include exposure factor, single loss expectancy, annualized rate of occurrence, and annualized loss expectancy:

Exposure factor The EF represents the percentage of loss that an organization would experience if a specific asset were violated by a realized risk. The EF can also be called the loss potential. In most cases, a realized risk does not result in the total loss of an asset. The EF simply indicates the expected overall asset value loss because of a single realized risk. The EF is usually small for assets that are easily replaceable, such as hardware. It can be very large for assets that are irreplaceable or proprietary, such as product designs or a database of customers. The EF is expressed as a percentage.

Single loss expectancy The EF is needed to calculate the SLE. The SLE is the cost associated with a single realized risk against a specific asset. It indicates the exact amount of loss an organization would experience if an asset were harmed by a specific threat occurring. The SLE is calculated using the formula SLE = asset value (AV) * exposure factor (EF) (or SLE = AV * EF). The SLE is expressed in a dollar value. For example, if an asset is valued at $200,000 and it has an EF of 45 percent for a specific threat, then the SLE of the threat for that asset is $90,000.

Annualized rate of occurrence The ARO is the expected frequency with which a specific threat or risk will occur (that is, become realized) within a single year. The ARO can range from a value of 0.0 (zero), indicating that the threat or risk will never be realized, to a very large number, indicating the threat or risk occurs often. Calculating the ARO can be complicated. It can be derived from historical records, statistical analysis, or guesswork. ARO calculation is also known as probability determination. The ARO for some threats or risks is calculated by multiplying the likelihood of a single occurrence by the number of users who could initiate the threat. For example, the ARO of an earthquake in Tulsa may be .00001, whereas the ARO of an email virus in an office in Tulsa may be 10,000,000.

Annualized loss expectancy The ALE is the possible yearly cost of all instances of a specific realized threat against a specific asset. The ALE is calculated using the formula ALE = single loss expectancy (SLE) * annualized rate of occurrence (ARO), or ALE = SLE * ARO. For example, if the SLE of an asset is $90,000 and the ARO for a specific threat (such as total power loss) is .5, then the ALE is $45,000. On the other hand, if the ARO for a specific threat (such as compromised user account) were 15, then the ALE would be $1,350,000.

Threat/Risk Calculations

The task of calculating EF, SLE, ARO, and ALE for every asset and every threat/risk is a daunting one. Fortunately, quantitative risk assessment software tools can simplify and automate much of this process. These tools produce an asset inventory with valuations and then, using predefined AROs along with some customizing options (that is, industry, geography, IT components, and so on), produce risk analysis reports.

Calculating Annualized Loss Expectancy with a Safeguard

In addition to determining the annual cost of the safeguard, you must calculate the ALE for the asset if the safeguard is implemented. This requires a new EF and ARO specific to the safeguard. In most cases, the EF to an asset remains the same even with an applied safeguard. The EF is the amount of loss incurred if the risk becomes realized. In other words, if the safeguard fails, how much damage does the asset receive? Think about it this way: If you have on body armor but the body armor fails to prevent a bullet from piercing your heart, you are still experiencing the same damage that would have occurred without the presence of the body armor. Thus, if the safeguard fails, the loss on the asset is usually the same as when there is no safeguard. However, some safeguards do reduce the resultant damage even when they fail to fully stop an attack. Body armor is usually this type of defense because it will absorb a significant amount of energy from a bullet and thus cause less damage to the body.

Even if the EF remains the same, a safeguard changes the ARO. In fact, the whole point of a safeguard is to reduce the ARO. In other words, a safeguard should reduce the number of times an attack is successful in causing damage to an asset. The best of all possible safeguards would reduce the ARO to zero. Although there are some perfect safeguards, most are not. Thus, many safeguards have an applied ARO that is smaller (you hope much smaller) than the nonsafeguarded ARO, but it is not often zero. With the new ARO (and possible new EF), a new ALE with safeguard application is computed.

With the pre-safeguard ALE and the post-safeguard ALE calculated, there is yet one more valued needed to perform a cost/benefit analysis. This additional value is the annual cost of the safeguard.

Calculating Safeguard Costs

For each specific risk, you must evaluate one or more safeguards, or countermeasures, on a cost/benefit basis. To perform this evaluation, you must first compile a list of safeguards for each threat. Then you assign each safeguard a deployment value. In fact, you must measure the deployment value or the cost of the safeguard against the value of the protected asset. The value of the protected asset therefore determines the maximum expenditures for protection mechanisms. Security should be cost effective, and thus it is not prudent to spend more (in terms of cash or resources) protecting an asset than its value to the organization. If the cost of the countermeasure is greater than the value of the asset (that is, the cost of the risk), then you should accept the risk.

Numerous factors are involved in calculating the value of a countermeasure:

- Cost of purchase, development, and licensing

- Cost of implementation and customization

- Cost of annual operation, maintenance, administration, and so on

- Cost of annual repairs and upgrades

- Productivity improvement or loss

- Changes to environment

- Cost of testing and evaluation

Once you know the potential cost of a safeguard, it is then possible to evaluate the benefit of that safeguard if applied to an infrastructure. As mentioned earlier, the annual costs of safeguards should not exceed the expected annual cost of asset loss.

Calculating Safeguard Cost/Benefit

One of the final computations in this process is the cost/benefit calculation to determine whether a safeguard actually improves security without costing too much. To make the determination of whether the safeguard is financially equitable, use the following formula:

ALE before safeguard − ALE after implementing the safeguard − annual cost of safeguard = value of the safeguard to the company

If the result is negative, the safeguard is not a financially responsible choice. If the result is positive, then that value is the annual savings your organization can reap by deploying the safeguard.

The annual savings or loss from a safeguard should not be the only consideration when evaluating safeguards. You should also consider the issues of legal responsibility and prudent due care. In some cases, it makes more sense to lose money in the deployment of a safeguard than to risk legal liability in the event of an asset disclosure or loss.

In review, to perform the cost/benefit analysis of a safeguard, you must calculate the following three elements:

- The pre-countermeasure ALE for an asset-and-threat pairing

- The post-countermeasure ALE for an asset-and-threat pairing

- The ACS

With those elements, you can finally obtain a value for the cost/benefit formula for this specific safeguard against a specific risk against a specific asset:

(pre-countermeasure ALE − post-countermeasure ALE) − ACS

Or, even more simply:

(ALE1 − ALE2) − ACS

The countermeasure with the greatest resulting value from this cost/benefit formula makes the most economic sense to deploy against the specific asset-and-threat pairing.

TABLE 6.1 illustrates the various formulas associated with quantitative risk analysis.

Table 6.1 Quantitative risk analysis formulas

| Concept | Formula |

| Exposure factor (EF) | % |

| Single loss expectancy (SLE) | SLE = AV * EF |

| Annualized rate of occurrence (ARO) | #/year |

| Annualized loss expectancy (ALE) | ALE = SLE * ARO |

| or | ALE = AV * EF * ARO |

| Annual cost of the safeguard (ACS) | $ / year |

| Value or benefit of a safeguard | (ALE1 − ALE2) − ACS |

Yikes, So Much Math!

Yes, quantitative risk analysis involves a lot of math. If you have math questions on the exam, at least it will be basic multiplication. Most likely, you will be asked definition, application, and concept synthesis questions on the CISSP exam. This means you need to know the definition of the equations/formulas and values, what they mean, why they are important, and how they are used to benefit an organization. The concepts you must know are AV, EF, SLE, ARO, ALE, and the cost/benefit formula.

It is important to realize that with all the calculations used in the quantitative risk assessment process, the end values are used for prioritization and selection. The values themselves do not truly reflect real-world loss or costs due to security breaches. This should be obvious because of the level of guesswork, statistical analysis, and probability predictions required in the process.

Once you have calculated a cost/benefit for each safeguard for each risk that affects each asset, you must then sort these values. In most cases, the cost/benefit with the highest value is the best safeguard to implement for that specific risk against a specific asset. But as all things in the real world, this is only one part of the decision-making process. Although very important and often the primary guiding factor, it is not the sole element of data. Other items include actual cost, security budget, compatibility with existing systems, skill/knowledge base of IT staff, and availability of product as well as political issues, partnerships, market trends, fads, marketing, contracts, and favoritism. As part of senior management or even the IT staff, is it your responsibility to either obtain or use all available data and information to make the best security decision for your organization.

Most organizations have a limited and all-too-finite budget to work with. Thus, obtaining the best security for the cost is an essential part of security management. To effectively manage the security function, you must assess the budget, the benefit and performance metrics, and the necessary resources of each security control. Only after a thorough evaluation can you determine which controls are essential and beneficial not only to security, but also your bottom line.

Qualitative Risk Analysis

Qualitative risk analysis is more scenario based than it is calculator based. Rather than assigning exact dollar figures to possible losses, you rank threats on a scale to evaluate their risks, costs, and effects. The process of performing qualitative risk analysis involves judgment, intuition, and experience. You can use many techniques to perform qualitative risk analysis:

- Brainstorming

- Delphi technique

- Storyboarding

- Focus groups

- Surveys

- Questionnaires

- Checklists

- One-on-one meetings

- Interviews

Determining which mechanism to employ is based on the culture of the organization and the types of risks and assets involved. It is common for several methods to be employed simultaneously and their results compared and contrasted in the final risk analysis report to upper management.

Scenarios

The basic process for all these mechanisms involves the creation of scenarios. A scenario is a written description of a single major threat. The description focuses on how a threat would be instigated and what effects its occurrence could have on the organization, the IT infrastructure, and specific assets. Generally, the scenarios are limited to one page of text to keep them manageable. For each scenario, one or more safeguards that would completely or partially protect against the major threat discussed in the scenario are described. The analysis participants then assign a threat level to the scenario, a loss potential, and the advantages of each safeguard. These assignments can be grossly simple, such as using High, Medium, and Low or a basic number scale of 1 to 10, or they can be detailed essay responses. The responses from all participants are then compiled into a single report that is presented to upper management. For examples of reference ratings and levels, please see Tables 3-6 and 3-7 in NIST SP 800-30 (http://csrc.nist.gov/publications/nistpubs/800-30/sp800-30.pdf).

The usefulness and validity of a qualitative risk analysis improves as the number and diversity of the participants in the evaluation increases. Whenever possible, include one or more people from each level of the organizational hierarchy, from upper management to end user. It is also important to include a cross section from each major department, division, office, or branch.

Delphi Technique

The Delphi technique is probably the only mechanism on this list that is not immediately recognizable and understood. The Delphi technique is simply an anonymous feedback-and-response process. Its primary purpose is to elicit honest and uninfluenced responses from all participants. The participants are usually gathered into a single meeting room. To each request for feedback, each participant writes down their response on paper anonymously. The results are compiled and presented to the group for evaluation. The process is repeated until a consensus is reached.

Both the quantitative and qualitative risk analysis mechanisms offer useful results. However, each technique involves a unique method of evaluating the same set of assets and risks. Prudent due care requires that both methods be employed. TABLE 6.2 describes the benefits and disadvantages of these two systems.

Table 6.2 Comparison of quantitative and qualitative risk analysis

| Characteristic | Qualitative | Quantitative |

| Employs complex functions | No | Yes |

| Uses cost/benefit analysis | No | Yes |

| Results in specific values | No | Yes |

| Requires guesswork | Yes | No |

| Supports automation | No | Yes |

| Involves a high volume of information | No | Yes |

| Is objective | No | Yes |

| Uses opinions | Yes | No |

| Requires significant time and effort | No | Yes |

| Offers useful and meaningful results | Yes | Yes |

Handling Risk

The results of risk analysis are many:

- Complete and detailed valuation of all assets

- An exhaustive list of all threats and risks, rate of occurrence, and extent of loss if realized

- A list of threat-specific safeguards and countermeasures that identifies their effectiveness and ALE

- A cost/benefit analysis of each safeguard

This information is essential for management to make educated, intelligent decisions about safeguard implementation and security policy alterations.

Once the risk analysis is complete, management must address each specific risk. There are four possible responses to risk:

- Reduce or mitigate

- Assign or transfer

- Accept

- Reject or ignore

Reducing risk, or risk mitigation, is the implementation of safeguards and countermeasures to eliminate vulnerabilities or block threats. Picking the most cost-effective or beneficial countermeasure is part of risk management, but it is not an element of risk assessment. In fact, countermeasure selection is a post-risk-assessment or -risk-analysis activity. Another potential variation of risk mitigation is risk avoidance. The risk is avoided by eliminating the risk cause. A simple example is removing the FTP protocol from a server to avoid FTP attacks, and a larger example is to move to an inland location to avoid the risks from hurricanes.

Assigning risk, or transferring risk, is the placement of the cost of loss a risk represents onto another entity or organization. Purchasing insurance and outsourcing are common forms of assigning or transferring risk.

Accepting risk is the valuation by management of the cost/benefit analysis of possible safeguards and the determination that the cost of the countermeasure greatly outweighs the possible cost of loss due to a risk. It also means that management has agreed to accept the consequences and the loss if the risk is realized. In most cases, accepting risk requires a clearly written statement that indicates why a safeguard was not implemented, who is responsible for the decision, and who will be responsible for the loss if the risk is realized, usually in the form of a “sign-off” letter. An organization’s decision to accept risk is based on its risk tolerance. Risk tolerance is the ability of an organization to absorb the losses associated with realized risks.

A final but unacceptable possible response to risk is to reject risk or ignore risk. Denying that a risk exists or hoping that it will never be realized are not valid prudent due-care responses to risk.

Once countermeasures are implemented, the risk that remains is known as residual risk. Residual risk comprises any threats to specific assets against which upper management chooses not to implement a safeguard. In other words, residual risk is the risk that management has chosen to accept rather than mitigate. In most cases, the presence of residual risk indicates that the cost/benefit analysis showed that the available safeguards were not cost-effective deterrents.

Total risk is the amount of risk an organization would face if no safeguards were implemented. A formula for total risk is threats * vulnerabilities * asset value = total risk. (Note that the * here does not imply multiplication, but a combination function; this is not a true mathematical formula.) The difference between total risk and residual risk is known as the controls gap. The controls gap is the amount of risk that is reduced by implementing safeguards. A formula for residual risk is total risk − controls gap = residual risk.

As with risk management in general, handling risk is not a one-time process. Instead, security must be continually maintained and reaffirmed. In fact, repeating the risk assessment and analysis process is a mechanism to assess the completeness and effectiveness of the security program over time. Additionally, it helps locate deficiencies and areas where change has occurred. Because security changes over time, reassessing on a periodic basis is essential to maintaining reasonable security.

Selecting a countermeasure within the realm of risk management relies heavily on the cost/benefit analysis results. However, you should consider several other factors:

- The cost of the countermeasure should be less than the value of asset.

- The cost of the countermeasure should be less than the benefit of the countermeasure.

- The result of the applied countermeasure should make the cost of an attack greater for the perpetrator than the derived benefit from an attack.

- The countermeasure should provide a solution to a real and identified problem. (Don’t install countermeasures just because they are available, are advertised, or sound cool.)

- The benefit of the countermeasure should not be dependent upon its secrecy. This means that “security through obscurity” is not a viable countermeasure and that any viable countermeasure can withstand public disclosure and scrutiny.

- The benefit of the countermeasure should be testable and verifiable.

- The countermeasure should provide consistent and uniform protection across all users, systems, protocols, and so on.

- The countermeasure should have few or no dependencies to reduce cascade failures.

- The countermeasure should require minimal human intervention after initial deployment and configuration.

- The countermeasure should be tamperproof.

- The countermeasure should have overrides accessible to privileged operators only.

- The countermeasure should provide fail-safe and/or fail-secure options.

The successful implementation of a security solution requires changes in user behavior. These changes primarily consist of alterations in normal work activities to comply with the standards, guidelines, and procedures mandated by the security policy. Behavior modification involves some level of learning on the part of the user. There are three commonly recognized learning levels: awareness, training, and education.

A prerequisite to actual security training is awareness. The goal of creating awareness is to bring security into the forefront and make it a recognized entity for users. Awareness establishes a common baseline or foundation of security understanding across the entire organization. Awareness is not exclusively created through a classroom type of exercise but also through the work environment. There are many tools that can be used to create awareness, such as posters, notices, newsletter articles, screen savers, T-shirts, rally speeches by managers, announcements, presentations, mouse pads, office supplies, and memos as well as the traditional instructor-led training courses. Awareness focuses on key or basic topics and issues related to security that all employees, no matter which position or classification they have, must understand and comprehend.

Awareness is a tool to establish a minimum standard common denominator or foundation of security understanding. All personnel should be fully aware of their security responsibilities and liabilities. They should be trained to know what to do and what not to do.