Chapter 3

Xiaomi: The Most Valuable Start-up in China

A few days before the end of 2014, Lei Jun, the founder and CEO of Xiaomi, the fast-rising Chinese smartphone maker, announced the receipt of $1.1 billion in investment funds following its latest round of fund-raising. Just months before, in the Summer of 2014, Xiaomi took the No. 1 position in China's smartphone market – the world's largest. That investment round valued Xiaomi at $45 billion, making it the highest valued start-up in the world at that time (close to Yahoo's market value), even ahead of $41 billion achieved by the US car-sharing service Uber Technologies Inc. earlier in the same month. (Uber's valuation exceeded Xiaomi later after additional fund-raising rounds.)

Consistent with Xiaomi's signature online-first marketing for its smartphones, the founder announced the investment terms in a post on his verified account on Weibo, China's Twitter-like messaging service. The mobile world, both in China and the West, immediately erupted into heated debate about whether this rising star could justify a $45 billion valuation. Was Xiaomi just an Apple copycat? Could it maintain its leadership position in the fast-maturing market of China when competing with domestic technology conglomerates as well as foreign behemoths like Samsung and Apple? Most importantly, how likely was it that Xiaomi would be able to apply its successful model for low cost smartphones into other product areas to create a new global internet powerhouse?

The Black Horse in a Crowded Market

Xiaomi, whose name means “millet” or literally “little rice” in Chinese, was founded as recently as 2010, yet has become the biggest success story in China's smartphone market. With about $40 million in initial financing, Mr. Lei teamed up with a former Microsoft and Google engineer, Lin Bin, and five other engineers to set up Xiaomi in a small office on the outskirts of Beijing. The company was originally a lean start-up looking to sell phones at cheap prices over the internet, and it also started a software platform named MIUI adapted from Google's Android system to power these phones.

In August 2011, Xiaomi introduced its first smartphone, the Mi-1, which meant that Xiaomi was decidedly late to the hardware game. (As a point of reference, Apple was releasing the iPhone 4S at the same time.) But Xiaomi never positioned itself as a premium device manufacturer. Instead, it insisted that it was an internet company; or if one had to associate the company with smartphones, it was a smartphone company with internet DNA. As discussed in detail later in this chapter, that positioning was reflected in its user base on social media as well as its online marketing strategy. Xiaomi's initial target demographic was young users, and the online buzz around its products attracted frenzied attention from young and trendy Chinese consumers.

In less than 5 years (by 2014), Xiaomi became the leading smartphone brand in China (although various market research firms in China occasionally publish conflicting ranking). From time to time Xiaomi was referred to as “the Apple of China” owing to the excitement it generated among Chinese consumers. Xiaomi's high growth and leadership position are not unchallenged. The iPhone6 release at the end of 2014 put Apple Inc. back into the top vendor position in China. More importantly, with help from its premium brand positioning, Apple took the lion's share of the profits of the smartphone market in China.

In 2015, the battle among the smartphone brands became ultra-competitive as the domestic market started to show signs of maturity and slowing growth. During the second quarter of 2015, according to reports from two analyst firms, Xiaomi regained its crown as the top smartphone firm in China. Shortly after that, in the third quarter of 2015, Chinese technology giant Huawei Technologies Co seized the top place in smartphone sales, while Xiaomi's year-on-year shipments declined for the first time since 2010. As one would expect, doubts arose about whether the most valuable start-up was able to sustain its high growth in an increasingly cut-throat and maturing Chinese smartphone market.

Before the discussion on the current competition and challenges that Xiaomi is facing, it is helpful to first examine several factors that have made it the dark horse in the world's largest smartphone market:

First, the young Mi-fan base before its smartphone release. Before Xiaomi launched its first smartphone in August 2011, it had worked on its Android-based MIUI software platform for more than a year. The MIUI system had gathered more than 300,000 fans (who called themselves Mi-fans), who became the initial core consumers for Xiaomi smartphones. The phones suited young, college-educated consumers who wanted a smartphone but could not afford a premium brand. Despite their limited purchasing power, these young users were internet savvy and active in social networking, and their online interactions with the company and among themselves at the internet forums further strengthened the Mi-fan base.

Because of its existing fan base, Xiaomi's first smartphone, the Mi-1 sold out in two days, and its Mi-2 and subsequent products sold out in a similarly quick fashion. Each new model would initially be sold in a limited quantity (perhaps 50,000 units) through a flash sale on its website. The lucky ones who managed to get the phones would “shai” them at the Mi-fan forums, creating a pent-up demand for the product. One may argue that Xiaomi simply created artificial shortages to generate buzz through “hunger marketing”, but in reality the loyalty of the fan base was more critical. Xiaomi's “hunger marketing” does not seem to be as effective as it has been in the past, which could be attributable to the fact that the offering is no longer novel or, possibly, to a permanent erosion of the fan base due to comparable offerings from the company's competitors.

Second, using low price strategy to grab market share quickly during the Chinese market's explosive growth. Smartphones are like personal computers (PCs) in China ten years ago. For many people in China, smartphones are a status symbol. People pay close attention to what kind of phone their circle of contacts is using, and even the people in the lower income buckets are eager to have a “presentable” a functional smartphone. Focusing on a niche passed up on by premium brands like Apple and Samsung, Xiaomi's low price, high performance devices have played well into the wider Chinese population's desire to own a smartphone and to access the internet for the first time.

Both Xiaomi's Mi (flagship) series products and Redmi series (budget) products are price-competitive devices. Its 2014 flagship model the Mi-4, whose hardware specifications were only slightly inferior to those of the iPhone 6, was sold at about $330 per unit, less than half of the latter's price, and the Redmi phone was sold at about a quarter of that of the iPhone's price. It is important to note that the telecom carrier environment in China has been a favorable factor for Xiaomi. The decline in the telecom carrier subsidy has pushed the majority of Chinese consumers to buy devices that are not associated with a carrier, creating room for entry for a new low-cost brand.

At the same time, Xiaomi has been generous in offering top-notch metal material, screen resolution, chip processor, camera and other features, in order to ensure that its low price is associated with a quality brand instead of a “cheap” product. The similarity of the design to that of the iPhone almost makes it an easy alternative to the Apple brand for many Chinese consumers. Furthermore, its online marketing strategy and the buzz in social media continue to create an attractive image linked to the young and chic lifestyle. With all that, Xiaomi has successfully created an inspirational brand for the consumers at the lower end of the spending power spectrum. As the domestic market begins to saturate and the incremental demand is generated from consumers looking for upgrades instead of their first ever smartphone, Xiaomi's products are moving towards consumers with higher spending power, and it is adjusting its brand identity accordingly.

It is worth noting that Xiaomi willingly accepts a lower profit margin on smartphone sales as part of the internet business model envisioned by the founder Mr. Lei Jun. In recent public interviews, Mr. Lei commented that on the Internet “the best products” – the products that the netizens use and enjoy the most, such as emails and most entertainment content – are all free. He believed that the quickest way for an internet company to attract users was through a flagship product that is offered free of charge, and this is the reason Xiaomi has been attracting and accumulating its users by selling its products as close to cost as is possible.

Of course, not all Xiaomi products and services will be provided at cost. Xiaomi's game plan is to use its high quality smartphone to build a loyal following at a large scale quickly (again, like Apple). Subsequently, a major revenue source will come from charging for services and accessories that accompany the phones. It also plans to generate revenue by providing proprietary software solutions for users’ other needs on the internet, which is similar to the way Amazon released low-price Kindle tablets to motivate customers into buying more e-books and entertainment content. This is the reason Xiaomi's founder likes to call Xiaomi an “internet company” instead of a smartphone company. The smartphone is simply the platform grabbing market share, the profit is connected to it, but lies elsewhere.

Third, a low cost structure based on the internet. Unlike other domestic smartphone players such as Lenovo, Huawei and ZTE that sell a large volume of smartphones through telecom carriers, Xiaomi sells almost all of its phones by way of the e-commerce channel. From the very beginning, Xiaomi's logistic system resembled the “just in time” model from Dell PC computers. Because the phones are ordered and distributed online, Xiaomi has shortened the circulation period of consumer data significantly and thus developed a speedy and very efficient supply chain.

This online model ensures that Xiaomi does not have to worry about the costs for middlemen and distributors, because the e-commerce sales only involve fulfillment and shipping costs, which is also consistent with Xiaomi's vision to be an “internet company”. It is worth noting that because online sales are less transparent, the industry ranking data compiled by the independent research firms are sometimes in conflict, and the corresponding ranking of the brands becomes uncertain and controversial as a result.

Following the same rationale, Xiaomi does not invest in traditional marketing. Instead it focuses on word-of-mouth advertising and social media channels, which are a lot less expensive than traditional advertising. Xiaomi management is also good at using creative strategies to generate buzz on social media to gain free publicity and potentially attract new customers. For example, after an executive meeting in late 2014, the company's co-founder and President Mr. Lin Bin proposed a push-up competition to his executive team. With a Xiaomi tablet on his back, Mr. Lin and other executives did push-ups until they all eventually collapsed from exhaustion. A photo of the competition was released and was broadly shared by the Mi-fans on the social media. This type of internet-based publicity is essentially free promotion for Xiaomi, and it also highlights Xiaomi's brand identity as a young, fun start-up. There is an important lesson here for innovators and entrepreneurs out there -- the public face of the company can be a potential asset and a key part of a marketing strategy. Whether it is Steve Jobs or Lin Bin, consumers respond more strongly to a brand represented by a persona with whom they can connect on a personal level.

Fourth, the ongoing deep engagement with the fan base. Xiaomi intentionally and carefully develops, invests in and nurtures a fan community that drives purchases through lifestyle affinity. Thanks to social media, Xiaomi has more than 10 million fans that extend well beyond China's most developed coastal cities to lower-tier cities. These communities are well organized and share a common passion (even to the point of idolatry) for Xiaomi and its products. The company's online forum has hundreds of thousands of posts a day and many Mi-fans make new friends that way. Those who spend a massive number of hours on the Xiaomi forum may eventually become a “VIP” in the community and be invited to parties that are specifically set up for select fans. This has the effect of making membership and online activism all the more desirable.

One particularly important way in which Xiaomi has been able to strengthen user loyalty is by involving its fans and users in software updates. Xiaomi releases a new version of the operating system every Friday and it listens to the online suggestions on design and features from its Mi-fans. This “updates based on user feedback” approach is also applied to hardware testing. The suggestions from the fans once they are adopted are quickly reflected in the new versions, and the fans enjoy a long-lasting sense of participation, achievement and ownership.

Essentially, the core value of the brand lies in its customers’ engagement. In a way Xiaomi is not selling a product, but the invitation to be a part of a virtual community. This is best illustrated by the many Mi-fan events and Mi Fan Festival organized by Xiaomi each year. At the fifth anniversary of its founding in April 2014, many new products were launched to celebrate the company's major milestone. What was remarkable was that in addition to more than 1 million handsets being bought by the fans on that single day, Xiaomi also sold hundreds of thousands of Mi Rabbits – Xiaomi's mascot, a stuffed toy bunny that wears a Chinese army hat. Nothing else demonstrated more strongly that the consumers in this instance went beyond simply buying a chic smartphone with a high performance-to-price ratio and were actually buying into the brand itself.

Changing Landscape, Fierce Competition

Although Xiaomi was the leading domestic smartphone brand in China in 2014 according to some research firms’ statistics, currently its sales volume are neck and neck with Lenovo and Huawei, the two most important domestic competitors of Xiaomi. Since Apple and Samsung are the two undisputed market leaders, Lenovo, Huawei and Xiaomi are now competing directly for the No. 3 position in the global market. (The two domestic rivals and Apple's Chinese business will be discussed in detail later in this chapter.)

It's worth noting that just like Xiaomi (and many other smartphone producers in China), Lenovo and Huawei have also adopted the Android operating system for their smartphones. So, from an operating system perspective, Google's Android system wins by a landslide (over Apple's iOS system) in China and globally, boosted by faster growing Android-based handsets from the Chinese manufacturers. (Of course, as discussed later in this book, the profit share of the global smartphone market is a totally different story. In recent years, Apple's iPhones have steadily been the most profitable phone business in the world by a huge margin.)

As China's smartphone market continued to mature, it started to show early signs of saturation in 2015, according to a recent study by the industry research firm IDC. The IDC report put the smartphone shipments during the first quarter of 2015 at 98.8 million, down 4.3% from a year earlier, which was the first decrease in new orders in the past six years. Of course, China's smartphone market is still the largest in the world, with Chinese brands still comprising roughly 50% of smartphone shipments globally in 2015 (and a similar share expected for 2016), but its pace of expansion is slowing down.

Amid ever higher smartphone penetration, the Chinese consumers’ tastes are shifting away from low end smartphones. Consequently, the domestic brands need to focus more on existing smartphone owners’ potential device upgrade than on the first-time buyers, and the battle for winning market share from competitors or, preferably, retaining buyers who have a tendency to gravitate to the major brands when upgrading has never been more intense.

In response to this change in market conditions, Xiaomi has developed a full product line that covers low, middle and high end price categories, with the middle and high ends as its new focus. Despite its attempts to be nimble it is clear that Xiaomi is facing fierce competition from both domestic and foreign rivals in every category. In the low price category, brands like Meizu and LeTV that people outside of China may never have heard of are using the same strategies as Xiaomi, selling their price competitive phones online throughout the country. Because their phones are even more competitively priced than Xiaomi's phones, these lower-tier manufacturers, if successful in attracting market share, may take a significant part of the lower end market share away from Xiaomi.

In the high end category, there is no easy way for Xiaomi to win the battle with the formidable Apple brand and its ultra-desirable premium products. As a result, Xiaomi has had to focus on the mid-price products category, which is crowded with domestic players like Lenovo and Huawei as well as the strong foreign rival Samsung. (The case of Samsung's early success and current struggle in the Chinese market is discussed in a different context in this book.) All are competing, at the cost of lower profit margins, to attract Chinese consumers who want to upgrade to phones with premium features. Apple, Xiaomi and Huawei were respectively at the top of the market share ranking in the first, second and third quarters of 2015, according to the statistics by the research firm Canalys.

Lenovo

Lenovo Group Ltd, formerly known as Legend, was founded in 1984 in Beijing. After more than 30 years, it has grown into a tech manufacturing conglomerate producing PCs, tablets, notebooks, servers and a wide range of devices. Lenovo now has three major business lines in traditional PC manufacturing, enterprise solutions and smartphones. Since 2013, Lenovo has surpassed Hewlett-Packard and Dell to become the world's largest personal computer (PC) maker by volume, but it has also made significant investments in the smartphone sector to balance the decline in global PC sales.

Compared to Xiaomi whose business is centered on smartphones, Lenovo's multiple major business lines are likely to be an advantage in the low margin competition in China's smartphone market. However, when Xiaomi reached the $45 billion valuation at the end of 2014, that number was roughly three times the market capitalization of Lenovo. That was an interesting phenomenon, as the net profit of Xiaomi in 2014 was most likely only a fraction of Lenovo's (due to the low price margin in Xiaomi's core business in smartphones), even though accurate numbers were not readily available as Xiaomi has remained a private company.

Part of Xiaomi's high valuation definitely came from the market's optimistic expectation of the growth of smartphone penetration and the potential high profitability from the add-on products and services that it offered. Lenovo's leadership, however, have expressed their view publicly that the smartphone market will soon become saturated, just like the personal computer (PC) market had been previously. Using the PC market as a reference, Lenovo expects the Chinese smartphone market to become less crowded in the near future as some weaker players have to drop out as a result of the cut-throat competition. With its experience in the earlier price wars for personal computers, and its multiple product streams, Lenovo is set to be a formidable rival of Xiaomi in the price war of smartphones.

Lenovo also provides “trendy” smartphone offerings to compete with rivals like Xiaomi. While Lenovo traditionally sells its phones through carriers, it has also expanded into the non-carrier retail market, as well as online sales through social media. For example, in 2015 it launched a sub-brand ShenQi (“Magic” in English) that was offered exclusively online to attract the young netizens. Also, after its acquisition of Motorola Mobility in 2014 from Google for $2.9 billion, Lenovo relaunched Motorola in China with a festival event modelled on Xiaomi events. Fans of Motorola were flown in from different parts of the country to appear on the center stage, with interactive social media feeds on the big screen.

The Motorola acquisition adds a new dimension to Lenovo's smartphone strategy in China. Motorola was a pioneer in mobile phones and a household brand in China many years ago, and it dominated the Chinese market before any real Chinese domestic brand ever surfaced. But it collapsed under the pressure of disruptive technologies and changing consumer behavior. After the merger, Lenovo decided to market both brands in the Chinese market, apparently hoping that its foreign-flavored brand could gain some advantage in the competition for the middle to high end market. Unfortunately, most young Chinese consumers do not remember the earlier glory days of the Motorola brand in China. (Motorola having departed from the Chinese market years ago.) As discussed in later chapters, the Motorola brand may end up helping Lenovo in its attempts at overseas market expansion rather than in the domestic market.

Huawei

Huawei was established 1987 in Shenzhen, the tech innovation and manufacturing hub in Southern China. During the last decade or so, Huawei has grown out of the domestic market to become one of the most competitive and dominant players in the global telecommunications markets. It is best known as the leading telecommunications equipment company in the world. It is also a major multinational networking services provider globally, with footprints in most of the world. Just like Lenovo, the profit from Huawei's smartphone business represents only a fraction of its networking business.

There are two possible reasons for Huawei joining the highly competitive smartphone field. One reason is that the telecom equipment market, just like the PC market for Lenovo, is growing increasingly saturated and is expecting slow growth, so the smartphone market is a potential high growth area for the company. The other reason is probably more important: Huawei has long predicted the convergence of the telecoms and IT businesses, and its leadership seems to believe that this convergence is happening with the emergence of smartphones, wearable devices and the internet of things.

Although in the middle of a pricing war, all the middle-market Chinese brands (which includes almost everyone, since Apple is the unquestionable top premium brand) are aiming to move into the premium brand category. Instead of seeking bigger sales volumes, Huawei's strategy has focused on heavy investment in R&D to offer superior technological features permitting them to charge a premium price. Huawei is justifiably proud of its extensive investment in R&D as well as its mobile network equipment background is also an advantage. Huawei is also a global leader in fixed broadband and mobile broadband technology, which translates into expertise in making phones that could work best with the latest network technology.

Recognizing the advantages of Xiaomi's online marketing approach, Huawei succeeded in increasing the ratio of sales through retailers and e-commerce sites to 80% and reduced sales through telecom operators to 20% by 2014. Interestingly, although Richard Yu, the head of its consumer business group and a Huawei group Executive VP, publicly acknowledged that Huawei's marketing model transformation came from Xiaomi's business practice, he nevertheless publicly insisted that “Xiaomi was never a competitor of Huawei”.

Indeed, Huawei has seen encouraging success in the mid to high-end category, and its Mate7 phone has been one of only a few domestic brands whose price tag has reached $650. The premium comes primarily from unique technological features (for example, Mate7 phones could work with removable hard disks). Meanwhile, Huawei's low-price brand Honor has also proved popular, creating a real challenge to Xiaomi in that lower end market. Richard Yu of Huawei said in a recent public interview that “at most, Xiaomi is a competitor to Huawei's Honor brand (the budget phone model)”.

During the 2015 Chinese New Year season, Richard Yu posted a public comment on Weibo (the Chinese version of Twitter), sending a “friendly reminder” to a “Diao-si brand” that its plan to move up to become a “Gao-Da-Shang” brand may not work out easily without unique core capabilities. Richard Yu's post didn't specifically mention the name of the target of his comments, but people naturally concluded that Xiaomi was the “Diao-si brand” he was addressing, because his comment highlighted the brand's fan base and good price-to-performance ratio. (See the “Diao-si” box.) In addition, Mr. Yu warned that Xiaomi might lose its original “diao-si” consumer base when it tried to move into a premium brand.

That Weibo post was deleted after only seven minutes online, but still stirred up angry remarks from the Mi-fans. Irrespective of the intended meaning of his post, Richard Yu made his point: Xiaomi could have a difficult time in repositioning its brand in the changing market. It needs to either seek high sales volumes at a low profit margin (like the PC market that Lenovo has dominated), or find a way to transform itself into a premium brand which either offers distinctive features (as with Huawei's success in its Mate series), or is an aspirational product that once again unites its fans.

Apple

Examining the Xiaomi phone's overall design, one will quickly notice that its device contours and display style show a remarkable degree of similarity to Apple's iPhones. From time to time the company has been criticized for borrowing so extensively from Apple and other rivals (such as Samsung). It is unclear whether it would have been possible for a company such as Xiaomi to offer a product such as this if intellectual property protection was more robust in China, but this is an issue for Xiaomi (and its rivals) and the courts. This book is simply noting the existing situation. Some critics suggest that Xiaomi has simply taken advantage of Apple's high-end brand identity in China: many Chinese consumers have idolized the Apple brand, and Xiaomi provides a similar product at a much lower price point so that customers are effectively buying a product that is viewed as an “affordable iPhone”. Given the opportunity and greater earnings, those same consumers will happily leave Xiaomi behind.

Traces of imitation of Apple can also be found in Xiaomi's management team, who do not hide their attempts to emulate closely Apple and its late founder Steve Jobs. When Xiaomi releases new products, founder Lei Jun typically comes to the stage in a black T-shirt and Converse shoes, similar to Mr. Jobs's signature outfit. In recent Xiaomi events, founder Lei Jun has also started to use the line “One more thing…” at the end of the presentation, which was the line that Jobs famously used for a surprise announcement of new innovations at Apple's product introduction events.

There is one notable difference however. Xiaomi phones are more “accessible” than the iPhones. Xiaomi takes a more open and dynamic approach to its software updates than Apple's iOS. Xiaomi invites “fans” on its forum to suggest new features, and it sends updates to users every Friday. Soon after each new version's release, thousands of Mi-fans on the internet forums quickly provide feedback to the company on functions, designs, bugs and potential solutions.

In contrast, Apple handles system development internally – Steve Jobs once famously said “customers do not know what they want”, and the customers receive iOS upgrades much less frequently in bundled form. Apple's system design is opaquely controlled by the company itself; therefore no matter who the customer is, there is only one set of standard solutions. Whereas Xiaomi develops a strong fan group based on engagement and community engagement, Apple accumulates its fan group based on exclusivity and a community centered on the cult of design and usability.

Apple opened its first store in China in 2008 and began selling the iPhone in the country in 2009. From the very beginning, Apple made the decision to maintain the iPhones’ high prices, making Apple a luxury brand in China. When theiPhone 5 series was introduced to China in 2013, its golden version quickly became a status symbol in China's high society. (See the “Tu-hao-jin iPhone 5s” box.) In 2015, Apple ranked as China's most coveted luxury brand, according to the Hurun Research Institute's annual survey of 376 ultra-wealthy individuals (whose average net worth exceeded $6.8 million). The survey found that Apple overtook traditional luxury brands including Hermes (2014 top ranking), Louis Vuitton, Cartier, as well as its immediate competitor Samsung as the “best” gifting brand of choice for China's wealthiest individuals.

However, in all the years before the iPhone 6 release at the end of 2014, Apple's highest ranking in China's smartphone market was fourth place in the first quarter of 2014, according to data from research firm Canalys. At the end of 2014, the strong demand for the iPhone 6 and iPhone 6 Plus helped Apple to win the No. 1 market share spot in China for the first time, and this sales momentum carried on into the first quarter of 2015.

There were several reasons for this iPhone 6-led jump in market share for Apple. The most obvious one is the increase in purchasing power of the middle class during the past several years. As the average monthly salary and disposable income continue to increase in China's major cities, Apple's target market keeps expanding. Second, and perhaps more important given the sudden nature of this shift, in December 2013, Apple was able to strike a partnership deal with China Mobile, the largest telecom network operator in China, to sell the new series of iPhone.

The third key factor, however, was Apple's response to its customers’ requests to increase the screen size on the iPhones. For the young demographic, and other active Chinese users, the smartphone is the device used most frequently for entertainment and e-commerce (instead of, and not in addition to, laptops or PC computers). The screen of the earlier versions of iPhones was too small for comfortable video viewing or efficient mobile payment transactions. Also, the small screen made inputting text more difficult because current Chinese character input methods still require users’ paying very close attention to the character keyboard displayed on the screen. The iPhone 6 series gained from the pent-up demand for such a product in 2014, particularly from the middle income group who liked the iPhone as a status symbol, but had picked up an Android phone earlier because of the latter's bigger screen.

As opposed to typical Western companies that would team up with a local partner to offer localized products, Apple played to its global core strengths and advantages, betting on the same premium brand strategy in China. So far, the successful sales of the iPhone 6 series have proved the strategy to be a success. By focusing on the mid- to high-end consumer demographic as the exclusive target for Apple apps and services, Apple has been able to maintain the high price of the iPhone and protect the integrity, as well as premium value, of its brand. This case offers an interesting reference point for other brands in China: in this booming market, should a brand go with a low price and mass distribution, or keep a premium brand and specifically target the purchasing power of the rapidly expanding upper middle class? The Apple case in China illustrates that the latter strategy could also lead to enviable market positioning and strong profits.

Of course, it remains to be seen whether Apple will be able to hold on to its top position after the wave of pent-up demand for the larger-screened iPhones. Using the gray market during the release of the iPhone 6 series as a reference point, the Apple phones’ scarcity premium seems to be on the decline. During the last few years, scalpers in Hong Kong rushed to purchase the new devices at almost every new Apple phone release and quickly flipped them to smugglers to generate a profit. The scalpers mobilized Hong Kong residents with local identity cards to pre-order phones before they collected them to transport across the border. But in the case of the iPhone 6 and the iPhone Plus, the gray market had mostly dried up.

The reason for this was not difficult to discern: the iPhone today is just one option among many for Chinese customers. Local players like Xiaomi, Huawei and Lenovo are offering high quality phones at lower prices, while also competing with Apple's “coolness” factor. The local brands are also more sensitive to the local users' needs, offering Chinese-oriented features such as large screen sizes, optimized connectivity for Chinese networks and dual SIM cards. In fact, Xiaomi and Huawei took the No. 1 market share position from Apple in the second and third quarters of 2015. And their ability to compete will likely improve going forward. As Xiaomi and other Chinese brands expand rapidly into the global markets, the battle is very likely to extend into the global marketplace.

Beyond Smartphones: The Future of Xiaomi

Because it is a private company, Xiaomi does not disclose its net income and profitability, but the news media have nevertheless reported on its estimated financial position. Just like Alibaba and other US-listed Chinese internet companies, Xiaomi's corporate structure includes a mix of domestic and offshore entities. At the top of the group structure is Xiaomi Corp., a Cayman Islands incorporated entity. Xiaomi H.K. Ltd., an offshore entity that is wholly owned by Xiaomi Corp., is believed to be the unit of Xiaomi that directly or indirectly controls the company's domestic units. When Xiaomi closed its latest fund-raising round that valued the company at $45 billion, some media entities that had gained access to some of Xiaomi's internal documents reported that that Xiaomi H.K. Ltd. had a profit margin of 13% and net profit of $566 million in 2014.

Those margin and profit numbers appear to be consistent with Xiaomi's “selling close to the manufacturing cost” strategy. On the one hand, Xiaomi chooses to sell cheaply priced phones to capture a large number of users for Xiaomi's mobile e-commerce businesses quickly before monetizing this community of users at the next stage. On the other hand, the fierce competition in the Chinese market has led to a price war among the smartphone brands based on the Android system, forcing everyone to use a low price as a key differentiating factor. Xiaomi has had to accept a thin profit margin for its smartphone business, as have its competitors.

According to a research report by the investment bank Merrill Lynch Securities on the state of the global smartphone industry in 2014, Xiaomi, Huawei and Lenovo were barely profitable, and the gross margin for each smartphone business was estimated to be at a single digit percentage level. Now that the Chinese market is showing signs of saturation, their profit margins will most likely be squeezed further going forward. Thus some people argue that Xiaomi is in a weaker position than Huawei and Lenovo in this war of attrition, because the latter two have additional business lines that are well established and profitable, whereas Xiaomi's revenue is mostly tied to its smartphones.

Insisting that it is an “internet company” instead of a smartphone company, Xiaomi explains that it focuses more on the internet software and services it sells to its loyal user base. Whereas most mobile phone brands see a sale as the end of the relationship, the company sees it as the beginning. Xiaomi's software and services are supported by its proprietary MIUI system, and Xiaomi is confident that the higher profit margin on them will more than compensate for the low profit margins on the phones.

However, one need only look at Apple – which Xiaomi strives to emulate – to find that this strategy, while effective, may need some time to generate profits. Unlike other smartphone manufacturers who use the open platform Android operating system, Apple uses its proprietary operating system and keeps this entirely under its own control. There is no question that Apple has developed an enormous user base for its product family of iPhone, iMac, iPad and iWatch. But when it comes to Apple's operating income and net profit, it is the iPhone sales that have consistently contributed the lion's share, while the income from software and services is only a small fraction of the total. According to some news reports in late 2014 that quoted Xiaomi's management, Xiaomi's hardware division contributed 94% to its total income.

Connected to the “user” strategy, an even bigger issue is the bifurcation between the smartphone hardware and mobile apps. Xiaomi does not fully “own” its phone users for internet services and transactions, because the Xiaomi device may simply be a medium for the users to access the mobile commerce platforms of other internet entities.

For example, using their Xiaomi phones, Chinese netizens may find the latest online gaming recommendations from their virtual network of friends through Tencent's WeChat, or make online purchases through Alibaba's mobile marketplace Taobao, or search for nearby restaurants’ locations and booking information using Baidu's search engine. Furthermore, each of these mobile platforms includes almost all e-commerce services, and the user could accomplish much without ever leaving the app ecosystem. Since the apps, as well as users, are “phone agnostic” for online activities, they may choose to ignore Xiaomi's own ecosystem of internet services as they continue to engage with the virtual world through their favorite apps. In other words, the activities (or “contexts”) supported by the dominant e-commerce players may be a more important gateway for users’ activities than those offered by the smartphone manufacturer itself, irrespective of how well entrenched its hardware is with its end users.

Xiaomi has fought back by creating an interface called Xiaomi Yellow Page which links the providers of local services to end users and vice versa (see Figure 3.1). The users of Yellow Page do not have to pre-install apps that they do not use frequently, such as those for express delivery tracking and train ticket ordering. To some extent, the Yellow Page helps Xiaomi to keep users of internet services at its own platform. However, the Xiaomi Yellow Page is more of an app consolidation than an innovative platform in its own right. So its “stickiness” – the ability to attract users, capture their attention and keep them coming back – remains questionable. As in the case of the killer apps from BAT, the users will surely install their favorite apps directly if they visit them frequently.

Figure 3.1 Xiaomi Yellow Page

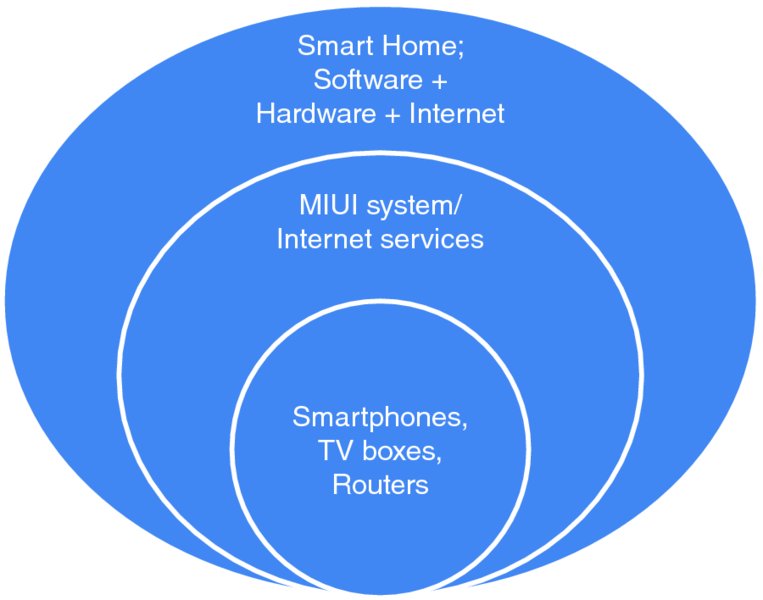

At the end of the day, the high valuation of Xiaomi by the market is a forward bet and is mostly linked to Xiaomi's future, which in founder Lei Jun's own words is “software + hardware + internet”. He considers the mobile phone to be a converged system of software, internet services and hardware, instead of a simple device for communication; he also believes Xiaomi could apply the same “internet thinking” to many other smart devices. The future of Xiaomi is to become an important player in the “internet of things”, and the “smart home” is among the company's top development and growth priorities.

Essentially, Xiaomi has evolved into a company of three layers of product offerings (see Figure 3.2). At Xiaomi's core are its well-established products of smartphones, TV set-top boxes and routers. The immediate next level is the internet services based on Xiaomi's MIUI system that supports the hardware products. According to the company's data, the MIUI system supported 27 languages and had 85 million users at the end of 2014. (In comparison, the main apps from the internet giants BAT already had hundreds of millions of active users.)

Figure 3.2 The Future – Three Layers of Xiaomi

A third level aims to develop a family of smart home devices that are seamlessly cross-linked under the Xiaomi “ecosystem”. For a start, the company has jumped into consumer electronics like cameras and even home appliances like air purifiers. In 2015 alone, Xiaomi spent nearly $1 billion on acquisitions and investments in 39 companies offering a wide variety of products. In a recent public announcement, Xiaomi indicated that it plans to invest $5 billion into 100 smart device companies to further augment its system.

This “software + hardware + internet” strategy, however, is not without its own challenges:

First, many internet firms are also working on integrating software and hardware businesses. While Xiaomi builds an internet company from smartphone hardware origins, other major internet companies are expanding into the hardware business from their existing core strength in mobile e-commerce. Just as the MIUI system and its app store are pre-installed on Xiaomi's own phones, the e-commerce players are investing in smart hardware so that they can fully shape their own users’ mobile experience, starting with the mobile terminal or access point. The best example is the e-commerce giant Alibaba, which has not shied away from investing directly in smartphone manufacturing.

In January 2016, in a move that surprised the market, Alibaba bought a minority stake in Chinese handset maker Meizu Technology Co., whose earlier version of the MX4 smartphone runs the YunOS system from Alibaba. The cloud-based mobile operating system YunOS (“yun” is the Chinese character for “cloud”) was developed by Alibaba in 2011, but only had limited success in attracting users. (Right before the investment into Meizu, according to some news reports it had just collected 10 million users, a tiny proportion of the gigantic Chinese market.) Compared to Xiaomi, Lenovo and Huawei Technologies, Meizu has a tiny market share in China. At the time of the Alibaba investment, Meizu's 2015 smartphone shipment target was about 20 million units, whereas the three top players were targeting 100 million units of annual sales. It remains to be seen whether the backing of Alibaba, and access to its funding, will provide a strong boost to the market share of Meizu phones in China.

The more interesting consequence of the deal, however, is that the two companies are collaborating to further develop Alibaba's existing YunOS system in the context of a “smart home” (see Figure 3.3). When this is considered, Alibaba's investment in smartphone hardware is not that surprising: since the major smartphone brands are not likely to give up their autonomy in terms of design and marketing, Meizu was probably the only available smart hardware partner for Alibaba. Just like Xiaomi, Alibaba is working on various smart hardware products, and the YunOS system opens the way to partnering with manufacturers.

Figure 3.3 YunOS Smart Home

For example, in mid-2015, Alibaba teamed up with the Chinese film company DMG Entertainment and the Hunan Satellite TV station to offer smart set-top boxes and bundled content to cable TV subscribers. For the first time, subscription-based internet, cable and mobile entertainment content was all offered as part of a bundle, similar to those offered in the US. The service reportedly began with six million cable TV subscribers in Hunan province, and it was expected to expand across China. The bundled content service and set-top box have included Alibaba's YunOS operating system, which may gain wider adoption as Alibaba continues to link smart devices with its strength in entertainment content and e-commerce.

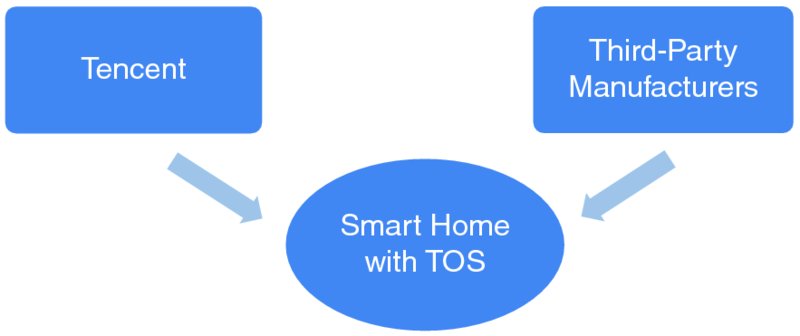

Tencent has a customized version of the Android operating system called Tencent OS, which has also expanded into the fields of internet-connected smart hardware such as TVs and fitness bands. In a model similar to Google's Android OS, Tencent seems content to be a pure software player that offers its system as an open platform for device manufacturers (see Figure 3.4). It is worth noting that as the phone market profit margin has been driven to a minimum on the hardware side, some phone makers may choose to form an alliance with Tencent, akin to Meizu teaming up with Alibaba.

Figure 3.4 TOS Smart Home

Second, Xiaomi is a late entrant to the internet content competition. In particular, entertainment content is being viewed by all internet firms as strategically important to attracting internet users to the mobile world, because the main theme of China's internet is entertainment. On the one hand, the entertainment business can be an important line of revenue growth by itself. On the other hand, when the e-commerce sector for consumer goods becomes increasingly saturated, unique content can effectively serve as a distinguishing factor to draw users to a particular e-commerce ecosystem, keep them hooked, and potentially lead them to related mobile transactions. (In later chapters, the explosive growth of the entertainment businesses on mobile platforms will be discussed in detail. All the major internet firms have invested aggressively to build an expansive content set, as well as platforms, that integrate online and offline entertainment businesses.)

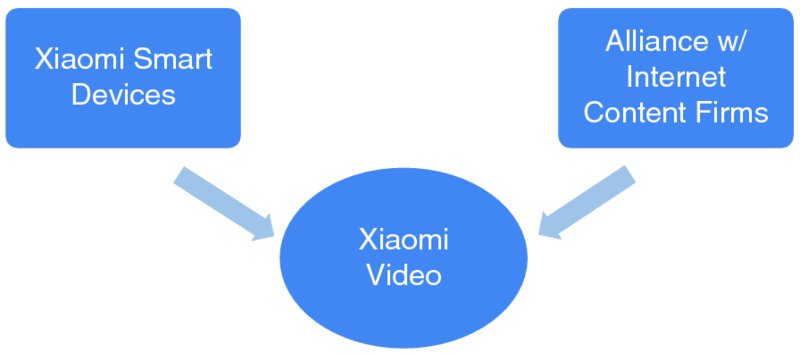

The content business is drastically different from Xiaomi's origins in hardware manufacture and distribution, and Xiaomi has responded by providing a unique set of offerings. In parallel with Xiaomi Yellow Page that integrates service apps, Xiaomi has set up a loose alliance with almost all the major video streaming companies to share their content within its own aggregating system (see Figure 3.5). In this new platform called Xiaomi Video, the users can easily access content from its alliance partners without having to install their respective interface content from Youku Tudou, Tencent Video and iQIYI as it is all available via a single interface. As Xiaomi's founder Lei Jun stated, Xiaomi “offers twice as much content as its competitors without charging customers their annual fees”. Of course, the content offered is also freely available on those platforms, which retain control of their unique content, hidden behind subscription walls. The benefit to them is the ability to market directly to Xiaomi users.

Figure 3.5 Xiaomi's Content Alliance

The the only major internet content company that is not part of the Xiaomi alliance, LeTV, is Xiaomi's most direct competitor because it offers its own “smartphone + content” ecosystem. Originally a video streaming company that has been compared to Netflix, LeTV has expanded its hardware business into smart TV-boxes, and then smart TVs, and more recently smartphones. Its new product, Superphone, is being promoted as a new kind of smartphone that gives access to a collection of exclusive content. If the customer also uses a smart TV from LeTV's product family, the user can use the phone as a remote control.

LeTV's offering is content-centric, and delivers premium content across different devices within its own software ecosystem. From LeTV's perspective, a content alliance is unlikely to provide users with high quality content, because no alliance member will contribute their unique content for free in this loose partnership with Xiaomi. On offer on Xiaomi Video is content that is freely available and could be watched without a subscription to their platform.

LeTV employs a subscription fee model based on exclusive content (and it is worth noting that this annual fee could be applied to offset the LeTV phone cost). Because it has substantial lead time in the content area, LeTV has developed a rich content library and has its own production team. By offering internally-produced content as part of its subscription package LeTV believes that it can offer users a much better “experience” than would be available as part of Xiaomi's alliance. For example, in 2015 LeTV announced a new partnership with NASDAQ-listed Immersion Corp. to provide viewers with four-dimensional (4D) videos on their smartphones. When watching 4D videos on smartphones, viewers could experience special effects like bomb explosions, car races and the wind blowing by interacting physically with their mobile phone.

These two different approaches to internet content led to a war of words between Xiaomi and LeTV in mid-2015. In practice, however, Xiaomi has quietly stepped up its efforts in acquiring and controlling unique content, as have the internet giants Alibaba, Tencent and Baidu. (As will be seen in the later chapters on the mobile entertainment business, the production of unique content has proven to be extremely costly for the internet firms, but the fee-paying model is gaining momentum in China where viewers have been used to free content.) Xiaomi has not only invested significant capital into several major online video sites, but also plans to set up its own content production capabilities.

One of the biggest investments ever made by Xiaomi, was ploughing $300 million into the Baidu-backed online video portal iQIYI. iQIYI is one of the largest online video sites in China, and it also has a division called iQIYI Motion Pictures, which, among other things, co-produces movies in collaboration with foreign partners. This investment should give Xiaomi important access to high quality content to further supplement its video streaming capabilities. At the beginning of 2016, Xiaomi also announced that it is building up a new unit to be named Xiaomi Movies for the film business. Because the content business is drastically different from Xiaomi's core competence, it remains to be seen whether its efforts in this direction will be successful and whether it can catch up with the competition.

Finally, when Xiaomi expands into overseas markets and much broader products offerings, it will be increasingly difficult for the company to maintain its existing business model. The $45 billion question is whether Xiaomi can replicate its smartphone success in other smart devices and integrate them seamlessly into its mobile ecosystem.

To a large extent, Xiaomi's success in China's smartphone market has much to do with Chinese users’ particular preferences and unique market dynamics. There is no guarantee that the model can be replicated elsewhere. For the Xiaomi model to work, the target market may need to have a large population, a developed e-commerce culture and weak telecom service providers. All these factors are important for Xiaomi's low-cost business model. For example, in a developed market like the US, the subsidies from telecom carriers could easily neutralize Xiaomi phones’ price advantage. In another example (to be discussed in detail later in this book), Xiaomi's internet distribution model could not work well in some parts of the Indian market due to the lack of internet infrastructure.

As a young start-up company, Xiaomi is also constrained by the relative absence of existing resources when expanding abroad. For example, Xiaomi does not have much in the way of a patent portfolio, so when it expands to the US or Europe, it may not have access to a sufficient number of patents to strike cross-licensing deals with other smartphone manufacturers, making the company vulnerable to lawsuits from competitors as it tries to innovate to match the features their products offer. Will that make access to overseas markets prohibitive, or simply mean Xiaomi's advantage will be a little less pronounced (because it has to pay for the use of others' patents for example)? The answer will only become clear as Xiaomi engages with markets outside of China.

Xiaomi spreads itself thin as it expands into such a large variety of “smart home” devices. The value proposition represented by Xiaomi's smartphone, means that the brand is linked to high quality in the minds of consumers. As Xiaomi launches a variety of new product categories, however, quality control could become an issue. Also, as the variety of devices expands it becomes increasingly difficult for Xiaomi to maintain its close contact with its users, something that it depends on for both innovation in terms of features, as well as ability to maintain an engaged community of users around the device. The Mi-fan culture has been instrumental to the success of the Xiaomi smartphone – in fact, Xiaomi had developed its Mi-fan base from its MIUI system before its very first smartphone release. With three layers of Xiaomi businesses, the company now has a much larger consumer base than before. But as a result, customers who are further away from the core business may have difficulty thinking of the company in a manner similar to the loyal fans that launched it on the path to success. It could be argued that it is these challenges that go to the heart of Xiaomi's brand identity, core culture and business model that may be the most critical to the company's future.

Despite all these challenges, Xiaomi's grounding in hardware and its successful smartphone business may prove invaluable in the smart device competition. Because its core business in smartphones has focused on competitive pricing, Xiaomi has developed extensive knowhow in supply chain management. As a result, it is likely that it can also do better in controlling costs of other smart devices than its content and platform focused competitors. Because internet firms like Alibaba and Tencent do not have hardware DNA, they will have to work out the complex supply chain issues or acquire hardware know-how by acquiring or partnering with device manufacturers.

In summary, the $45 billion start-up story of Xiaomi has yielded both resounding adulation by fans as well as harsh criticism by sceptics. Founder Lei Jun used to say that Xiaomi looks a bit like Apple, but it is really more like Amazon with some elements of Google. So far, Xiaomi has succeeded beyond even its wildest expectations, but citing a lack of core technological innovations and patents, some people are questioning the sustainability of its projected future growth. One thing is clear, in order for Xiaomi to become the “internet company” that its founders envision, a considerable amount of work needs to be done.