Chapter 8

Internet Finance

On January 4, 2015, the internet firm Tencent launched China's first internet-based bank “WeBank”. One of the five privately funded banks approved by China's central bank, PBOC, WeBank in Chinese suggests a bank for “micro and many”, reflecting its focus on ordinary individuals and small businesses and its linkage to the internet and social network. The ceremony was officiated by Premier Li Keqiang, and he pressed the “enter” button on a computer to send out the first loan of RMB35,000 ($5,400) by WeBank to a truck driver.

This first internet loan represented three important innovational aspects.

First, by providing microloans to the public, internet banks like WeBank addressed demands from individuals that were not adequately addressed by the existing financial system, with its focus on large companies.

Second, the internet bank conducted all operations online, so that the borrower did not need to go to an offline outlet to obtain the loan. WeBank first used Tencent's own version of facial recognition technology to verify the borrower's identity from a remote terminal; all of the loan processing was completed online.

Third, the creditworthiness of the borrower, the truck driver, was analyzed by utilizing big data technology, which effectively reduced the information asymmetry between the bank lender and the borrower. The driver was a member of a Tencent-invested logistics platform called Huo-che-bang (Truck Club), which links truck services with logistics companies. Based on the driver's driving history on the mobile app and his online profiles on other e-platforms, WeBank's financial model gave the driver a high credit rating and granted a loan carrying a 7.5% interest rate, without requiring collateral or a guarantee. In financial terms, WeBank's superior data sources and processing capability enable this internet bank to provide better priced credit to consumers. (Without sufficient information on the borrower, the interest on the loan would likely have been set higher by the bank.)

As summarized by Premier Li at the ceremony, “one small step for WeBank is a giant leap for financial reform”. This statement was no exaggeration as online purchases were only made possible in China a decade ago by an escrow-like service designed by Alipay, the online payment system affiliated with Alibaba. e-Commerce in China started with a cash-on-delivery model, but Alipay and other internet payment platforms managed to build trust between consumers and vendors by serving as a sort of escrow service: when a consumer made a payment through Alipay, Alipay notified the merchant to ship the order, and Alipay released the funds to the merchant only when the consumer received the product. This innovative set-up led to a boom in online transactions in China.

Today a large part of the Chinese population has skipped credit cards entirely in favor of digital payments, just as people in many parts of China are skipping landline phones to buy a smartphone to access the internet for the first time. In addition, Chinese consumers are comfortable with using the internet to manage their savings and investments. As internet companies transform smartphones into a platform for financial transactions, China is way ahead of the rest of the world in terms of how widely internet finance is adopted.

The rising integration of internet and finance is closely linked to two imperfections in the financial system – and potential solutions stemming from the internet. One is the lack of investment choices for individual savers and investors. China's financial services sector is immature compared with developed markets, and it lacks the variety of products and services found in the US market. The two major investment channels – public stock and real estate markets – require large investments and a high risk tolerance. Meanwhile the deposit interest rates at banks are tightly regulated and currently set at low levels.

The other imperfection is the difficult access to credit by small and new businesses, because banks concentrate on the bigger and established companies because of their perceived lower credit risk. In response, internet firms have set up online investment platforms for individuals to educate themselves on capital markets and invest in financial products. New lending and equity financing models are also initiated for under-served individuals and SMEs (small and medium-sized enterprises), such as peer-to-peer (P2P) lending, equity-based crowdfunding and microloans based on big data.

In a short period of time, internet finance has fostered a more inclusive financial system where loans and equity financing are more widely available to consumers, start-ups, SMEs and whoever can put them to productive use. New players, many of which are private, internet-based and light on assets, have entered China's mostly state-controlled financial industry and offered innovative products and services. (See Table 8.1 for selected providers of internet finance to be discussed in this chapter.)

Table 8.1 Examples of internet finance in China

| Product/Service | Providers/Brands (Selected) | Description |

| Third-party payments | Alipay, WeChat Pay | Support e-commerce, usage expanding into O2O activities, also used to pay utility and water bills |

| Crowdfunding | Demohour, dajiatou.com | A new financing channel for venture and movie investments, but estimated 75% capital flowing into “pre-market sales” relating to consumer products |

| P2P Lending | Jimubox, Renrendai, China Rapid Finance, Dianrong.com | Presently the dominant form of online lending, but there is a sharp rise in problematic platforms |

| Financial products sales | Ant Fortune (Alibaba), WeChat wealth management | Online money market funds, mutual funds sales, insurance sales, discount brokerage |

However, due to the lack of a market entrance threshold or business operation standards, many of these new offerings have evolved from regulatory “gray zones” and have grown rapidly “in the wilderness”. For example, in the first half of 2015, there were more than 400 new cases of P2P lending platforms running into operational difficulties, according to data from P2P portal www.wangdaizhijia.com.

On July 15, 2015, China's central bank, PBOC, teamed up with other related regulators and jointly issued the long-awaited policy framework on internet finance in China, the Guidelines on Promoting the Healthy Development of Internet Finance (referred to as “the Guideline” in this chapter). The Guideline defined internet finance as “traditional financial institutions and internet companies using internet technology for payments, internet lending, public equity financing, internet fund markets, internet insurance, internet trust, and consumer finance”. For the first time, government regulation defined the term “internet finance”, and the new financing businesses such as P2P lending and crowdfunding were recognized and addressed.

Reflecting the exceptional complexity of internet finance – which covers numerous financial services under different regulators – a total of 10 government ministries and commissions jointly issued the Guideline. On the financial industry regulators’ side, there were the central bank (POBC), the Ministry of Finance, the State Council Legislative Affairs Office and three regulatory commissions for the stock market, banking market and insurance market (CSRC, CBRC and CIRC, respectively). The internet industry was represented by the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, the State Administration for Industry and Commerce and the State Internet Information Office. In view of fraud and other crimes in this field, the Ministry of Public Security also joined the taskforce.

In terms of the regulatory responsibilities defined by the Guideline, the central bank would monitor online payments, the securities regulator CSRC would supervise crowdfunding and online sales of stocks and stock funds, and the banking regulator CBRC would oversee online lending platforms such as P2P lending. Based on this joint policy framework, the regulators would develop specific rules in their respective jurisdictions. As the topic of mobile payment has already been covered in the chapters on e-commerce and O2O markets, the following sections will focus on the new financing models (equity crowdfunding and P2P lending), the new internet distribution channels for asset management products and their related regulatory challenges.

Crowdfunding

Generally speaking, crowdfunding is a capital raising transaction involving a large number of people, with each person contributing only a small amount to the whole project. In China, the concept of crowdfunding has quickly become widely known precisely because of the “fun” focus of mobile internet. By allowing the average citizen to become a movie micro-financier, the application of crowdfunding to hit movies has educated the market and attracted wide participation (or at least, attention) from the public at large.

Crowdfunding has changed the way films are financed in China. Traditionally, Chinese films have been funded by studios, either state-owned or private, including the new ones set up by the internet firms themselves. In the digital age, crowdfunding campaigns are marketed as an opportunity for ordinary audiences to get involved in the glamour of movie making, since anyone who loves films or adores stars could become a minor investor and participate in movie production and promotion.

In September 2014, Baidu launched its movie financing product Baifa Youxi. Its funding site was a joint launch between Baidu, Taiwan's Central Picture Corporation, Citic Bank and DeHeng law firm in Hong Kong. To avoid the legal uncertainty around the crowdfunding deal structure (for example, constraints on public promotion and the number of investors), Baifa Youxi was set up as a trust for investment services, not a movie project to raise financing directly through crowds. The first movie project listed for investors at Baifu Youxi was Golden Age. Users could put up as little as RMB10 ($1.6) of their own money and receive yields (expected to be between 8% and 16%) based on how the films eventually perform at the box office.

Within hours the Golden Age crowdfunding product quickly attracted 3,300 supporters, who raised nearly $30 million, 120% of the movie's target. Since the investment capital from individual investors was small, the participants’ financial returns would likely be small, but they were probably more excited about being able to claim that they had worked on the Chinese version of the Hollywood classic Gone with the Wind (which Golden Age was compared to in China). In other words, Baidu expressly positioned the Baifa Youxi as a fun experience rather than a serious investment product.

Similarly, Alibaba launched its own version of a movie investment product called Yu'le-bao in 2014. Owing to regulatory considerations, Alibaba also structured it differently from typical equity-based crowdfunding. The Yu'le-bao platform offers investment-linked insurance products from Kuo Hua Life Insurance Company, which investors could purchase from as little as RMB100 ($16), and the collective funds were subsequently invested in entertainment projects. (Yu'le-bao could be translated as “entertainment treasure”.) Underlying the investment product was a range of projects from movies, TV shows and video games. As a way of gathering information on audiences’ taste preferences, each investor was asked to choose a maximum of two investment plans from the list of projects.

As the above examples demonstrate, when putting their small fragments of capital together, the young netizens, who individually do not have a large amount of disposable income, can create a sizable capital pool. As “mini-producers”, investors enjoy the opportunity to visit filming locations, get the exclusively issued electronic magazines and even meet the stars. Internet firms like Baidu and Alibaba, in addition to further familiarizing users with internet finance, also build up data on movie-goers’ taste preferences. It may also serve as a marketing channel, because the investors are likely to be incentivized to mobilize people they know to watch the movies, increase box office takings, and subsequently receive higher returns from their investments.

In addition to the movies and stars, celebrities in other fields have also used crowdfunding for their unique projects. (And in some cases involving unique experiences, such as in the “Harvard Education” box, crowdfunding has turned ordinary people into public figures.) In March 2015, Yao Ming, the former National Basketball Association all-star with the Houston Rockets, started a crowdfunding campaign to invite wine and basketball enthusiasts to own a piece of his Napa Valley winery, for as little as $5,000 per person. Not known to many people before the crowdfunding campaign, Yao Ming's winery had been the biggest seller of high-end Californian wine in China by value in recent years. Driven by Yao Ming's adventure story as a Chinese player in the US NBA, basketball fans and curious investors rushed to participate, and he had met half of his funding target of $3 million within a day.

While these movie-related and celebrity-centered crowdfunding events feature in the news headlines, the majority of the capital in the Chinese crowdfunding market flows into those related to consumer goods pre-sales. For example, e-commerce sites Taobao (Alibaba), JD.com and Qihoo 360 Technology all have sizable “crowdfunding” platforms for consumer products. That really is the unique characteristic of the crowdfunding market in China. One possible explanation is the value of social networks: in addition to marketing, branding and inventory management, a crowdfunding platform provides a kind of social network for e-commerce players, especially if they do not have a WeChat (Tencent) or Weibo (Alibaba).

Because it lowers the cost of setting up a venture company for a specific product, crowdfunding helps to create a new entrepreneurial ecosystem. As a result, more entrepreneurs can engage in more experiments, and innovative start-ups can put their products out into the marketplace with few capital barriers. Looking at the crowdfunding projects of consumer products, one could see them as a combination of venture investing (idea stage), pre-market purchases (product stage), and volume distribution (mature stage) throughout the different phases of a product's life cycle (see Figure 8.1).

Figure 8.1 Crowdfunding of Consumer Products

Then the question becomes whether the crowdfunding model is too lenient on the project teams. Many projects arrive at the fundraising stage when they are only rudimentary ideas. In many cases, production is postponed, product quality is below expectation, or the product is not quite the same as planned. But there is very little that investors can do about it, because crowdfunding promotes innovation. Is that fair to the ordinary investor? To put it another way, is it appropriate for normal investors to behave like venture capitalists, taking on the risk of untested companies?

To that end, one of the largest crowdfunding platforms in China, Demohour, decided to transform itself. Set up in July 2011, Demohour was among the earliest crowdfunding platforms, and the movie project it facilitated which received the most support was a film called A Hundred Thousand Bad Jokes. Soon after, however, Demohour concluded that the existing crowdfunding models for consumer products had led to investments in too many companies that should not have been funded in the first place.

In April 2014, Demohour decided to end its crowdfunding business and turn the company into a “smart device pre-market sales platform”. It vowed to select projects more vigorously before presenting them to the public investors. Also, to keep tighter control of the project, it would delay paying public funding to the project team until it saw substantive progress. (In the past, Demohour typically paid 70% of funding to the project team at the start.)

According to Demohour, in future all standardized product-related crowdfunding platforms will have to become “pre-market sales platforms”, because conflicts among consumers/investors, project teams and crowdfunding platforms are increasing under the earlier model. Essentially, Demohour suggests that the crowdfunding money should only be paid out in pre-market sales, i.e. when a new offering reaches its production phase. The rationale is simple: ordinary people are not venture capitalists, and they should stay with what they are best at – being consumers.

Going forward, the greatest potential that crowdfunding offers is an equity financing channel for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), but this is an area subject to tight regulation. In China, private companies must seek government regulators’ approval before listing, and the qualification requirements for public issuance of equity are very rigorous. In short, it is really challenging for SMEs and start-ups to be eligible for the public issue of securities, and the costs for the listing process and the continuous disclosure filing requirements are prohibitively expensive for SMEs.

In this context, the important legal issue is whether a crowdfunding transaction constitutes a public issuance of equity, which is regulated by China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC), or whether it can be structured as a private placement exempted from registration requirements. Generally speaking, crowdfunding is a sort of equity issuance, where a start-up or established company raises funding from the public for its project. In return, the investors receive a portion of equity returns as reward. In fact, the name “crowdfunding” already suggests there is an inherent “public” element.

This question is critical because if a crowdfunding project is deemed to be a public offering of equity securities, then it must go through the full process of registration, application and approval before financing. Failing this, in the worst-case scenario it could constitute an “issuance of shares or corporate or enterprise bonds without authorization” under the Criminal Law of China. (Of course, this type of crime involves large amounts of capital and severe consequences, a very different scenario from typical crowdfunding transactions where individuals invest small amounts.)

The rational approach for SMEs, of course, is to keep their crowdfunding as private offerings of equity stocks. However, there are stringent requirements to comply with. For one thing, private offerings cannot be promoted in the public domain; instead they have to be offered to a number of specific investors. Most equity-based fundraising platforms set up a membership system for this purpose. Before potential investors can receive information on projects, they first have to qualify as members of the platform.

However, the definition of qualified investors for private placements remains vague under China's Securities Law and related regulations. Taking the concept of “accredited investors” under US securities law as a reference, a qualified investor needs to possess high net worth, ample investing experience and/or special knowledge of the issuer. By contrast, those looking at crowdfunding in China are mostly average people with little capital and limited investing experience. In fact, crowdfunding platforms often ask only for people's names and ID numbers for membership registration. Therefore, compliance with “know your customer” remains an issue.

The other hurdle to qualify for a private placement is that the number of investors must not exceed 200 in total. To this end, most platforms generally hold shares in the form of a special purpose vehicle (SPV) as a means of “consolidating” investors. However, some recent CSRC regulations on private offerings seem to suggest that because the fundraisings often involve multiple levels of investors, the number of investors should be the total of all levels of the fundraising structure. This probably means that underlying investors in a SPV must be calculated separately, making the 200-investor limitation a critical issue for the ultimate fundraising size of crowdfunding transactions.

Finally, in the Guidelines for Internet Finance, the CSRC and other government ministries have formally determined that a crowdfunding of corporate equity characterized by “public distribution, small size, and wide participation” should be treated as a public offering of equity securities and is thus subject to regulation. (See Figure 8.2 for different standards for “public” and “private” crowdfunding transactions.) In other words, unless an equity-based crowdfunding by a corporation fits the standard of a private placement, it would be viewed as a mini-IPO (in the case of early stage start-ups) or a secondary offering (in the case of an existing listed company), subject to all the requirements of a public offering.

Figure 8.2 Two Versions of Crowdfunding: Public Offering vs. Private Placement

Due to the limitation on “small size (fundraising)”, “public side” crowdfunding is not likely to be an important financing channel for corporations any time soon. The small sums of money raised by crowdfunding transactions, whether public or private, may not be sufficient for the financial needs of SMEs and start-ups. In fact, the capital raised may not even be sufficient to cover the offering cost in the case of a “public” crowdfunding.

Crowdfunding should, however, be here to stay because it plays into the “fun” theme of mobile internet. Apart from pre-market sales, crowdfunding in China in the near future will most likely focus on small investments for hit movies, social entrepreneurship and similar projects offering a unique experience. With little investment involved, the downside risk for investors is limited, and at the least they may have some fun and enjoy some interesting stories – or learn about Harvard – in return.

P2P and Internet Bank Lending

Similar to creating new equity financing channels in the form of crowdfunding, the internet has also revolutionized the lending market. Online peer-to-peer (P2P) lending is the practice where ordinary consumers lend directly to individuals and small businesses using online platforms, without using a traditional financial intermediary such as a bank. Historically, commercial banks found small size loans too costly to cover, but these days digitally mediated transactions are reducing lending costs and leading to a boom in financial activities.

While crowdfunding attracts many “diao-si” investors who make a small investment for the sheer joy of participating, P2P lending appeals to a smaller group of wealthy investors who are far more willing to take risks in large amounts. P2P has exploded in popularity in China over the last few years (see Figure 8.3), and China has already surpassed the level in the US (where the model was first developed) and become the world's largest peer-to-peer lending market since 2015. Across the country there are estimated to be more than 3,000 P2P platforms focusing on four industry segments: consumer lending, small business lending, auto loans and real estate lending.

Figure 8.3 Growth in Chinese P2P Online Lending (2011–2015)

(Data Sources: Wangdaizhijia.com, Wind Information)

The P2P lending business is part of the shadow banking market in China, as many P2P lending websites gather funds from the public and then lend funds to individuals or small companies, instead of simply serving as an information platform to facilitate lending and borrowing between parties. A general shortage of credit in the Chinese banking system, combined with banks’ preference to lend to large SOEs (state-owned enterprises), drives individuals and SMEs to online lenders. Attracted by the rapid growth and business potential, venture capital and major internet firms have flocked to the P2P platform start-ups (see Table 8.2).

Table 8.2 Major Chinese P2P platforms and their investors

| Chinese P2P Platforms | Investors (Domestic and Foreign) |

| Renrendai | Tencent |

| ppdai.com | Sequoia Capital |

| Yooli.com | Softbank China Venture Capital, Morningside Group |

| jimubox.com | Xiaomi, Temasek, Matrix Partners, Ventech Capital, Magic Stone Investment |

| Penging.com | Shenzhen Hi-tech Investment Group |

The essence of “peer-to-peer” lending is to use network technology to achieve equal positioning by both the borrower and lender in four aspects: information disclosure, risk appetite, term structure and rights and obligations. In China, however, P2P is understood to be “person-to-person” by some market players. Their P2P platforms aim to allow anyone with money to become a lender, and anyone who needs money to apply for a loan. Without a proper setting, the online lending business is ripe for abuse. Recently there have been a number of Ponzi scheme-like scandals where lenders have pooled funds from investors without matching them to borrowers.

To better protect investors’ interests, the new Guideline has clarified two critical issues relating to P2P lending. As a result, the market has seen a complete shake-up of the existing business model, and the breakneck pace of P2P lending growth has slowed dramatically. The first requirement of the Guideline is that P2P platforms can only serve as information channels to match borrowers with lenders. The Guideline bans P2P sites from “enhancing borrower credit worthiness” (that is, providing security or guarantees for the loan). In other words, P2P lending platforms are now defined as information intermediaries (brokers) rather than credit intermediaries (banks).

This clear definition is a blow to many P2P platforms. In developed markets, the government's credit bureau has data on individuals’ credit history, from which the P2P operators can supply a score for the potential borrower, on which potential lenders can base their decision about whether to enter into the transaction. (In fact, internet firms like Alibaba and Tencent are using their online big data to develop new credit score systems to fill this gap in China, which will be discussed later in the chapter.) But in China this type of credit data system is not fully developed, making additional types of credit support, such as collateral or guarantees, necessary for P2P business.

For example, to attract investors to try out their innovative loan offerings, new P2P platform entrants typically provide high expected return figures. But first-time investors tend to worry about the inherent high risk related to high returns, so the P2P platforms often implicitly guarantee “principal amount protection” to appease investors’ concerns. The reality is, however, that Chinese laws prohibit the salespeople of investment products from guaranteeing “principal protection” or investment returns, except for bank deposits or government bonds (because they are essentially risk free).

For smaller P2P businesses, they will likely have difficulty finding customers if they are not permitted to provide any credit support (such as guarantees or collateral) to win over investors’ confidence. Even before the 2015 regulatory guideline, repeated fraud-related bankruptcies or sudden website closures had already highlighted the risks of the smaller P2P operators. The recent online fraud cases involving high profile P2P platforms further shook the confidence of the public. (See the “P2P Fraud” box.) Therefore, a consolidation of businesses is expected, where only the P2P platforms backed by large companies with trusted reputations can survive.

The second important requirement in the Guideline is that internet finance players like P2P platforms must entrust their users’ funds to the custody of licensed brick-and-mortar banks. In the past, most P2P platforms kept the funds at third-party payment institutions, and the market believed that was a major flaw leading to cases where P2P operators fled with customer funds. To comply with the new rules, P2P platforms are reaching out to banks to set up custodian partnerships.

This custodian relationship is likely to accelerate commercial banks’ entry into online lending. China's commercial banks had kept a close eye on the enormous custodian business for P2P and other internet finance businesses, but the regulatory uncertainties kept them from making major moves. With the new Guideline in place, commercial banks will speed up their entry into the P2P custodian business, and they may acquire quality P2P platforms to strengthen their internal capabilities for internet finance activities. However, due to reputation and credit risk considerations, banks may not accept small P2P operators as custodian clients, which should lead to further consolidation of the P2P market in favor of the larger players.

In this context, a licensed internet bank can be viewed as a formally registered P2P platform with a full banking license to provide legitimate online deposits and lending services. WeBank, which is 30%-owned by the internet giant Tencent, was the first licensed privately-owned internet bank to start operations. Zhejiang Internet Commerce Bank (also called MYBank), a subsidiary of Ant Financial Services Group and closely affiliated with the Alibaba Group, completed its registration a few months later and launched similar web-only banking businesses in mid-2015. Before the arrival of these official internet banks, internet firms had already provided financing services for e-commerce merchants in the form of microloans or supply chain financing. With their experience with individuals and vendors in mobile commerce, they are well placed to serve the under-banked consumers and small businesses at a low cost.

Traditionally, most of the state-run banks in China favor lending to big institutions for two reasons. On the one hand, the major commercial banks have had long-term relationships with and knowledge of the big companies in China. On the other hand, historically the banks have limited data tools for credit risk evaluation of individual consumers and SME businesses, and the transaction costs for those small loans under the brick-and-mortar banking model are prohibitively high. By contrast, internet banks run branchless banking operations that can serve customers 24/7. Their cloud-based model requires much lower operational costs than the traditional brick-and-mortar banking model. In addition, their parent companies’ substantial databases of consumer behavior from internet businesses allow them to compile credit risk data in unconventional and innovative ways.

The internet banks are therefore able to provide financial solutions for a gap in the consumer economy, i.e. providing small amounts of credit to people that cannot be reasonably priced within the formal banking system to fill their special needs. Again, take the first internet loan by WeBank as an example. For the loan to the randomly selected truck driver, Tencent's WeBank used internet-linked data mining tools to assess the credit background of the potential borrower. The driver was a club member at the Tencent-invested logistics platform called Huo-che-bang (“Truck Club”), which linked logistics operators that needed to ship cargo with truck driving companies.

At the time of the loan, this platform had one million drivers with 650,000 truckers as members, and it was serving more than 160,000 logistics company customers. For each club member trucker, Tencent's platform had a large amount of information, such as total distances travelled, total cargo volumes transported, the scope of orders handled and so on. Some drivers had to pre-pay cargo freight, but commercial banks were not set to process such small loan amounts of that nature. WeBank, however, could refer to the data from the driver's operations on the mobile app, develop its own analytic model and evaluate the potential borrower's creditworthiness.

There is no doubt that the branchless bank concept is a major revolution from the existing banking model. Besides lower operating costs, it brings a lot of convenience to the users: there is no need to search for the locations of branches, no travelling required and no queues. Concerning the regulatory requirement on personal identity verification, however, the fact that they are branchless has been the biggest obstacle for internet banks to be fully functional as planned.

Under the current rules of China's central bank, PBOC, when individuals open a banking account, they must visit a real bank outlet to have their identities verified by a bank employee. Similar regulations on personal loans require bank employees to visit every loan applicant at the person's work or business, and then personally witness the signing of each application. Internet-only banks, however, by definition have intentionally eliminated these face-to-face encounters for the sake of efficiency and cost saving.

The solution offered by the internet firms is biometric identification at remote terminals. Among the possible options, facial images have been the top choice by internet firms, ahead of fingerprints, palm prints, retina images and other alternatives. One obvious consideration is probably cost: with the cameras on desktop PCs and smartphones, the marginal cost of taking a digital picture for identification is close to zero. Also, the facial characteristics read by the technology can be compared with the photos at the personal identification card information center and those in police databases. This type of technique means that online facial recognition can leverage offline security agencies’ authoritative databases, whose information has been developed by strict face-to-face settings.

In January 2015, WeBank demonstrated Tencent's own facial recognition technology at the first pilot internet loan, where the truck driver verified his identity from a remote terminal. Shortly thereafter, one of its executives commented in a public interview that their facial recognition technology was quite mature and had lower error probability than the verifications done by human eyes. Supported by strategic cooperation between Tencent and the National Citizen Identity Information Center, which was affiliated to the Ministry of Public Security, its accuracy rate reached 99.65% at that time.

A few months later, Alibaba's founder Jack Ma unveiled Alibaba's own version of facial recognition at the CeBit conference in Hanover, Germany. He pushed a “Buy” button on an app that he called “Smile to Pay”, matched his face with a white outline, and took a picture of himself. That information was transferred to the Alipay server and verified. With that, he bought a 1948 vintage souvenir stamp from Hanover as a gift for the mayor. According to media reports, Alibaba's face scanning system (called Face++) had an accuracy rate of around 99.99%. In addition to remote verification for banking, Alibaba's aim is to apply the facial recognition to all e-commerce, so that within a few years there will be no need to enter a password.

So far, China's central bank is not fully convinced of the accuracy and security of the facial recognition technology. In 2015, the central bank, PBOC, decided that “the conditions are not yet mature for using biometric technology as the primary means of verifying the identities of depositors”. According to the Guideline, biometric identification cannot be used officially until a national standard for its use is developed in the financial sector and the related financial regulations are amended accordingly. Since WeBank's initial loan made remotely to the truck driver, the personal loan service remains in the testing phase. Similarly, Alibaba's MYbank is operating with limited offerings because the physical presence requirements for the opening of accounts are not lifted yet.

The controversy around facial recognition technology illustrates the fine balance that China's financial regulators have to strike. In the Guideline, the authorities have recognized the efficiencies of online banking, the new services it offers to customers and the innovations it brings to the financial industry. The challenge for regulators is to keep pace with technological change and strike a delicate balance that allows innovation to flourish while mitigating risk.

Internet-based Wealth Management

While only a small percentage of the population goes into crowdfunding and P2P lending in China, the majority have embraced internet finance to manage cash (including payments and short-term savings) and access standardized investment products. The latter is a much bigger market (trillion dollars) for internet firms than the former two business lines. For a start, online short-term deposit products from internet firms have been the best example of financial innovation in the mobile economy.

In June 2013, the first Internet Money-Market Fund (I-MMF) product, Yu'e-bao, was launched by Alibaba's financial arm Ant Financial (formerly known as Zhejiang Ant Small & Micro Financial Services Group). The Yu'e-bao I-MMF was offered to internet users as an alternative to traditional short-term deposits at commercial banks.

By the end of 2013, the Yu'e-bao product had already attracted more than 120 million investors and accumulated more than RMB100 billion ($15 billion) assets.

To put the numbers in context, the Yu'e-bao product made the underlying asset manager, Tianhong fund management company (in which Alibaba has a majority stake), the first investment fund in Chinese market history to exceed AUM (assets-under-management) of RMB100 billion within 6 months of launch. By mid-2014, Yu'e-bao's AUM exceeded RMB600 billion (more than $90 billion), standing as one of the largest money market funds globally. Months after Yu'e-bao, Tencent launched its version of I-MMF, “Licai-tong”, which also attracted a large volume of AUM in a short period of time.

The exceptional popularity of the I-MMF products is the result of internet firms identifying and solving several structural issues of the financial market in China with the help of internet tools. First, Chinese households have one of the highest savings rates in the world, so they have trillions in cash in bank deposits. They are not happy with the low returns from the deposits, but they are not necessarily comfortable with the risks of public stocks or real estate. Therefore, Chinese investors are constantly in search of risk-controlled alternatives to demand deposits.

The interesting twist was that Yu'e-bao provided investors with higher returns than typical bank deposits. Its premium return, to a large extent, actually came from Yu'e-bao investing in bank deposits itself. By drawing a big pool of money together, Yu'e-bao's manager Tianhong could negotiate higher deposit rates when it put the capital into the interbank market. In the summer of 2013, the interbank market saw tight liquidity conditions, represented by the skyrocketing borrowing rate (the Shanghai LIBOR rate). As a result, Yu'e-bao was able to offer much higher rates than direct bank deposits. For example, in July 2013, the 7-day rate on Yu'e-bao on an annualized basis floated around 4.6% for a period of time, more than 10 times the benchmark bank deposit rate (0.35%).

Second, Yu'e-bao and similar products have managed to accumulate a large amount of “leftover capital” via the internet. (In fact, “Yu'e-bao” can be translated into “treasure in residual amounts”.) As seen in the internet literature business from earlier chapters, celebrity online novelists are supported by a large number of diao-si readers who pay a miniscule amount to read an installment. Similarly, Yu'e-bao has no investment threshold (which is required by most wealth management products sold at banks), and its minimum initial investment is as low as RMB1 (15 cents in US dollars).

Third, the I-MMF products have high liquidity because of simple online procedures, and they can easily be processed on smartphones and other gadgets. I-MMF products like Yu'e-bao can generally be redeemed on the same day and in many cases within the hour. By contrast, traditional money market funds (MMF) require two to three days to complete the redemption process. In other words, I-MMF products like Yu'e-bao have the high-yield benefit of a MMF but maintain the same liquidity as a bank deposit.

The explosive growth of Yu'e-bao and similar I-MMF products shocked the commercial banks. At the inception of these I-MMF products, the banks saw customers moving out deposits at an alarming rate; meanwhile, they had to finance the interbank market at a high cost. To put it differently, commercial banks experienced a lower asset and liquidity base (the decrease of cash deposits) and higher operating costs (the financing costs to buy liquidity at the interbank market) when challenged by I-MMF products. In a somewhat drastic response, some banks set limits on their customers’ daily transfers of cash to I-MMF services like Yu'e-bao. Soon the major commercial banks started to launch their own internet MMFs that could be redeemed on the same day (T+0).

From a different perspective, the essence of the remarkable success of Yu'e-bao is simply using the internet as a better information channel and a more convenient transaction platform. In the past, banks were the most important channels for funds’ marketing because of their large number of brick-and-mortar branches. Money market funds are readily available at banks and other financial intermediaries, but many ordinary people do not know about them, and the banks as the distribution channel are not incentivized to promote them. Now financial products on the internet have eliminated such information asymmetries. At traditional commercial banks customers also have to go through a separate process to invest in MMFs, while the I-MMFs have simplified the process so much that the customers can transact on smartphones in a few minutes.

Building on the momentum of Yu'e-bao, Ant Financial has developed itself into a distribution platform for investment products covering various asset classes and different risk/reward profiles (see Table 8.3). In August 2015, it launched a dedicated wealth management app “Ant Fortune” (in parallel with the e-payment app Alipay Wallet). To advertise the app and to help the majority of the population to become familiar with financial products, Ant Financial offered the funds at zero commission fees during the promotion period. In addition, it reduced the redemption period from 3 days (T+3) to 1 day (T+1).

Table 8.3 Various “Treasures” and products from Ant Financial/Alibaba

| Name | Investment Profile | Risk |

| Yu'e-bao | Cash management (liquid) | Lowest |

| LeYe-Bao | Insurance coverage for company staff | Low |

| Yu'le-bao | Similar to crowdfunding, invest indirectly in entertainment projects like mobile games, movies and TV shows | Moderate to High |

| ZhaoCai-bao | Fixed-term wealth management products, Alternative assets | Moderate to High |

| Stock Funds | Public stock market exposure | Moderate to High |

| Stock Trading | Direct exposure to individual stocks (to come) | High |

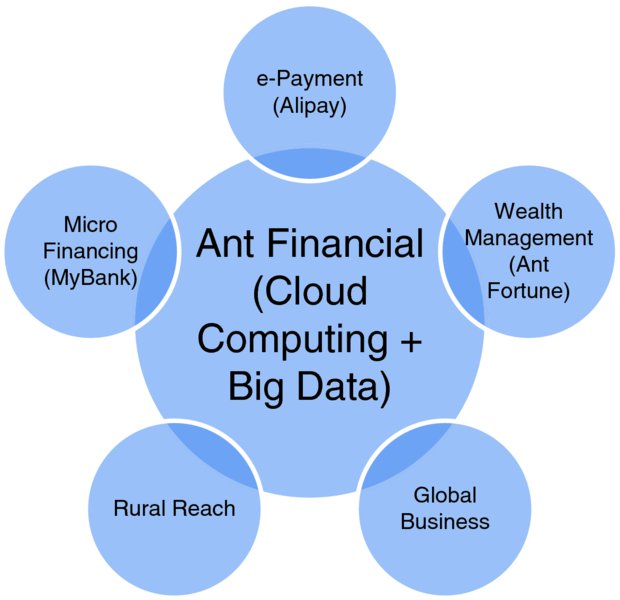

However, the ambition of Ant Financial does not end with being a channel for money market funds or investment funds. It aims to develop a broad-based mobile financing system based on the big data and cloud computing capabilities from the whole Alibaba Group. The Alipay Wallet app, Ant Fortune app, and more mobile services that Ant Financial plans to launch in the near future collectively have the potential to take control of the majority of the population's money transfers, savings, investing and everyday spending in China, if the commercial banks and other financial institutions do not react quickly.

As outlined in the earlier chapters on e-commerce and O2O, Alipay has dominated the mobile payment market. It not only processes e-commerce transactions, but also handles many other types of online payments like utility and water bills. With O2O businesses rising, Alipay has spread into numerous offline payments as well, such as taxi hailing, restaurant services, and movie ticketing. After more than 10 years’ development, Alipay (started in 2003) has completely dominated the PC terminals. At the mobile terminals, even with the increasing competition from WeChat payment based on the social network, Alipay's market share remains at a staggering 80% level according to market research firms’ data.

The main reason for having Ant Fortune as an asset management app that is independent of, rather than integrated with, the Alipay Wallet app is to prevent Alipay from becoming too “big and burdensome” as a platform, which would have a negative impact on users’ experience. This illustrates the enormous scale of the services represented by each business line. When its micro financing business, represented by MyBank, takes off, Ant Financial will most likely launch a separate mobile app for that as well. (See Figure 8.4 for the e-money empire that Alibaba is building up.)

Figure 8.4 Ant Financial's e-Money Empire

With existing leading positions in the above three areas in domestic urban markets, the greater potential for Ant Financial's future growth is in rural China and global markets. In rural areas, the internet services could likely fill a role similar to the community banks in the US – serving clients the big banks do not cover and providing small size loans that the big banks’ business model cannot justify from a cost perspective. The internet may also be the best medium to educate a large part of the Chinese population about capital markets and financial investments that they have never dealt with.

In the global markets, by mid-2015 Alipay reportedly had more than 17 million overseas users and supported settlement transactions in 14 foreign currencies. Relating to cross-border e-commerce, Alipay has developed services like overseas tax rebates, overseas O2O, international money transfers and so on. Meanwhile, Ant Financial is also reaching out through foreign partnerships. In early 2015, Alibaba acquired a 25% stake in the parent company of the major Indian online payment platform and e-commerce firm Paytm. Significant internet finance growth may come from bringing financial inclusion to those emerging market populations that have long been left out of the mainstream business world, as in rural areas of China.

The Future of Internet Finance

By applying mobile technologies to the finance industry, internet firms surprised the traditional financial institutions by offering innovative and convenient services to consumers, which truly put consumer experiences front and center. However, it remains to be seen how disruptive internet finance can be for traditional banking. In the digital age, traditional banks have quickly adopted internet data and analytics capabilities, and every financial institution is incorporating mobile internet technology into its traditional banking and asset management operations.

Take mobile payments as an example. In this field, the difference in user experience between Alipay and banks’ online payment services is continuously decreasing. In addition to commercial banks catching up quickly, internet firms also face new challenges from foreign peers. In February 2016, Apple officially launched its much anticipated Apple Pay service in China through a partnership with China UnionPay (CUP), the only domestic bank card organization. (Samsung is also expected to reach an agreement with CUP soon to bring the Samsung Pay system to China.) Using Apple devices, the customers of 19 major Chinese banks are able to link their bank accounts to Apple Pay, which supports both mobile app and in-store payments. The users can complete transactions at e-commerce sites that accept the payment system or at offline merchants that have compatible point-of-sale (POS) machines from UnionPay.

Although Alipay is the default payment method for e-commerce transactions on Alibaba's e-commerce marketplaces, the payment setups at offline storefronts vary significantly. For O2O activities, consumers generally find a product or merchant before selecting the corresponding payment method (instead of picking the payment method first and then finding a transaction). The customers have to go with the payment method used by the merchant or platform behind the transaction, where Alipay may only be one option. For example, Apple has already listed Carrefour, 7-Eleven, Burger King, McDonalds and KFC among the merchants accepting in-store Apple Pay in China. As a result, Alipay may not always be used by customers when alternatives are readily available and equally functional.

Furthermore, the “big four” state-owned commercial banks have fully developed internet channels and platforms for their customers. For example, all of the major banks have web-based “direct banking” services, which not only offer traditional banking services like credit card repayments and account management remotely via the internet, but also cover expanded services like wealth management and money wiring services. According to a presentation by a major commercial bank executive in 2015, more than 85% of banking business is now being processed through e-channels, a substantial jump from less than 20% ten years ago. Similarly, securities firms and insurance companies are building online and mobile channels to reach more potential customers with specialized products.

Among the industry players, there are radical disagreements on whether the arrival of internet firms is bringing about a revolution in the finance industry, or if the industry is simply going through a rebalancing process after the adoption of internet technology. If the internet only brings a new distribution channel to the finance industry, then internet financing will fall short of a revolution, particularly because the traditional institutions have quickly incorporated the internet channel into their existing large balance sheets and broad branch presence. The “heavy infrastructure” that the banks have accumulated and developed for decades may turn out to be a major competitive advantage in the internet finance war (see Figure 8.5).

Figure 8.5 Banks’ “Heavy Infrastructure” Likely a Competitive Advantage

Therefore, in the same way as video streaming sites have to use unique entertainment content to keep viewers loyal, internet finance companies have to provide special value and services to maintain user loyalty. Otherwise, internet finance firms like Ant Financial may find it difficult to justify their high valuations based simply on their exploitation of the internet as a channel to market. (Ant Financial was valued at more than $40 billion in its 2015 private fundraising round, among the most valuable start-ups in China, like the smartphone maker Xiaomi).

For example, in the summer of 2013 when the I-MMF product Yu'e-Bao was launched, the capital markets had tight market liquidity. Yu'e-Bao benefited from high interbank rates and thus was able to offer much higher yields for customers than bank deposits. As a result, it accumulated users and assets-under-management (AUM) rapidly. However, since 2014 China's central bank has steadily injected cash into the banking system, and the interbank rate has decreased correspondingly. By mid-2015, the yield offered by Yu'e-Bao dropped to half of the yield at inception, and its AUM decreased to a fraction of its peak amount.

To provide unique value to users, the most promising area for internet firms may be to offer small loans to Chinese individuals and SMEs. These under-serviced customers collectively have a huge need for credit, but it is challenging for the commercial banks to acquire (1) a large number of (2) small-scale borrowers (3) with good credit quality (4) at a low cost. Because the majority of the 1.4 billion population has had no credit spending experience or even any interest in borrowing from financial institutions at all, there is no well-developed credit scoring system in China, similar to the FICO scores and other consumer credit record services in the US.

The big data capabilities of internet firms, derived from e-commerce transactions and social network activities, have provided them with a huge competitive advantage. In early 2015, Alibaba launched Sesame Credit Management Group to develop a credit-scoring system primarily based on online data. Sesame Credit was one of the eight privately owned credit-scoring businesses that received preliminary approval from China's central bank, PBOC, and its access to online transaction data has been unrivalled to date.

While in the past the Chinese were using Alipay simply to shop on Alibaba's Taobao e-marketplace, these days the payment platform is so ingrained in China that its hundreds of millions of users access the platform to pay nearly all their household bills. The wealth management platform Ant Fortune also has hundreds of millions of users who manage their savings and investments there through Yu'e-bao and other financial products. In addition to shoppers’ online e-commerce transaction records, Taobao and Tmall also have a history of dealings with tens of millions of small businesses that sell or source goods on the two marketplaces.

All this data on retail consumers enables Sesame Credit to work with those who may have little credit history at traditional credit agencies. As more merchants adopt the Sesame credit score system, “Sesame” opens the door for Alibaba in two directions (see Figure 8.6). On the one hand, Sesame Credit can facilitate access for more consumers to new borrowing services such as home loans, car loans and other types of installment credit. For example, Mobile Loans, a P2P lending website that has partnered with Alibaba, announced that loan requests from borrowers with high credit scores at Sesame would be processed much faster than others. On the other hand, more credit transactions bring more data to the Sesame Credit database, which can serve as a foundation for Alibaba's many other businesses such as O2O business lines.

Figure 8.6 Two-way Data Flow between Sesame Credit and Digital Businesses

Tencent, on the other hand, is applying a social network-based methodology to the credit evaluation of internet users. On Tencent's social networking platforms like WeChat and QQ, more than half a billion people have registered their personal data with effective identity certification. Just like the trucker's operational record on the logistics service app relating to the pilot microloan, Tencent believes that user behavior and history on the social networks also provide sufficient data for the evaluation of creditworthiness. The logic is that the more someone uses social networking services, the more likely that person is to be conscious of and concerned about his or her reputation.

In addition, at Tencent's gaming platform the users’ transactions on virtual goods and online game points are also useful variables for internet data mining. Some of these parameters used by Alibaba and Tencent may seem unconventional, hard to quantify and somewhat arbitrary, but they are all valuable inputs for the big data approach.

According to news reports, P2P lending site China Rapid Finance had used the social network data provided by Tencent WeChat and gaming data to rate 50 million Chinese consumers for creditworthiness by mid-2015.

By contrast, commercial banks generally take an asset-based approach in credit assessment. It is hard for individuals and SMEs to get the loans if they do not have collateral or assets. As a result, while hundreds of millions of the new middle class are now financially active consumers, the existing financial system has not sufficiently covered the majority of the population. Many young, employed people do not have credit scores. That is an enormous vacuum that needs to be filled quickly as China moves into a consumption economy, and the internet-based big data approach may be the only efficient way to resolve it.

The biggest uncertainty around the seemingly unlimited potential of internet finance is industry regulation. China's rapidly expanding internet finance sector is coming under increased scrutiny from Chinese regulators due to the rising numbers of P2P scandals. As discussed earlier in this chapter, regulators have resisted approving facial recognition technology for opening full-service online bank accounts without visits in person to bank branches. As commercial banks rapidly build up their own internet channels, the explosive growth of Yu'e-bao is not likely to be repeated frequently in other areas of the financial markets.

Furthermore, when internet firms dive directly into the underlying finance businesses (in addition to being a new channel), their operations will be subject to the same supervision as traditional banks and institutions, their products will be similarly examined and regulated, and their corresponding compliance costs may turn out to be much higher than they have anticipated. Again, the banks’ existing operational infrastructure, as well as their extensive compliance experience, may provide them with a significant edge in the war of internet finance.

But there is no doubt that internet finance firms can be a source of inspiration and transformation for traditional financial institutions with their pioneering business models and consumer service culture. China is at a crossroads with internet finance and – given the immense potential value to consumers – should move promptly to place it on a sound footing. In particular, commercial banks can refer to the way internet lending platforms innovate through their collection and analysis of consumer data for credit and risk management. As a wave of financial sector liberalization sweeps through China, internet finance may experience a breakthrough from a comprehensive upgrade of the existing regulatory framework.