Chapter 7

“Internet+” Movies

Just like Xiaomi, the dark horse of the smartphone market, the movie series Tiny Times also had the Chinese character for “little” in its name, but it was one of the biggest domestic hits in the mobile internet age.

Tiny Times is a novel-turned-movie series that follows four fashionable college girls navigating their way through romance, work and friendship in Shanghai. As such it has been likened to Gossip Girl and Sex and the City. In the summer of 2014, the premiere of Tiny Times 3.0 raked in nearly $20 million, a record for domestic 2D films. It shocked both the Chinese movie industry and Hollywood when it unseated the US blockbuster Transformers: Age of Extinction to reach the top of China's box office charts during the first week of its official release.

It was remarkable that Tiny Times 3.0’s origination, production and distribution were entirely shaped by social media, big data and internet financing, from beginning to end. The movie was based on a popular web novel, and the producer tapped into the novel's online fans and social network followers for suggestions on selecting the director and stars of the films. The distributors claimed that not a single advertising billboard was used across the country for marketing purposes; instead, promotion was done through the social networks of high school students and young adults. When the movie was criticized for its glorification of consumer culture, its fans – mostly young and female, like the heroines in the movie – rallied to its defense on social networks.

Tiny Times is a good example of a new generation of “internet+” movies in China. Similarly to restaurant booking and car-service hailing, the movie industry is seeing smart devices, ticket-booking mobile apps and related online movie streaming increasingly turning netizens into filmgoers at offline cinemas. At the same time, producers use big data technology to cater to the content demanded by modern Chinese youth, a group that had not been sufficiently addressed before by Chinese movies. For example, the luxurious lifestyle of high society girls in the movie, from fashion brands to exclusive clubs, clearly resonates with the young audiences’ vision of success. Because of these new developments in the internet-related channel and content, the young generation who live with smartphones and tablets are turning themselves into movie-goers.

This trend may seem counter-intuitive at a time when online entertainment consumption is experiencing explosive growth. But it is truly a demonstration of the power of the internet, which keeps injecting new momentum into China's movie market. In fact, the movie business has quickly become one of the fastest-growing sectors in the O2O market. Not surprisingly, all the e-commerce giants are investing heavily in the sector, and each believes its respective online strength – search, e-commerce and social networking – will provide a powerful movie promotional tool. In addition, guided by the big data of audience behavior, each of the firms has set up its own movie unit to produce movies directly, especially those relating to stories about the young generation (who make up the majority of the Chinese internet population).

There is no question that these internet firms are the producers, distributors and exhibitors of the future. This explains why the head of distribution for a major China film group said at a recent industry conference, only half jokingly, that in the future all Chinese movie companies will work for BAT (Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent). At the same time, the internet giants are also expanding into overseas markets as studio buyers, content acquirers and distribution outlets, and this is creating both excitement and anxiety in Hollywood studios. This chapter will discuss how mobile internet has revolutionized China's movie market and why the Hollywood movies’ strategy in China is also being challenged to transform.

The Big Screen Boom

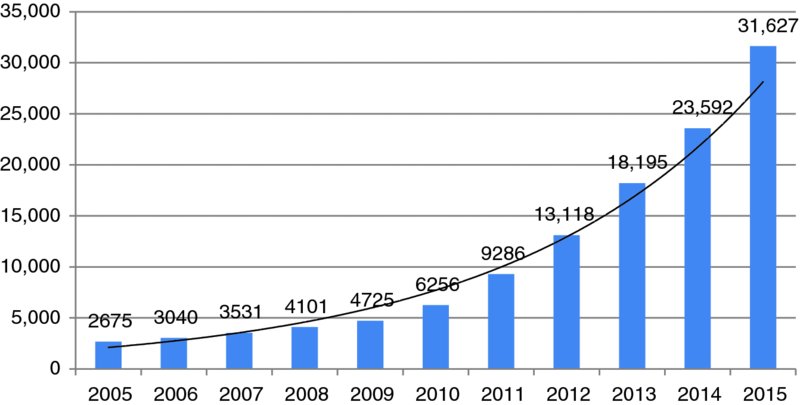

Before discussing the profound implications of the mobile internet and mobile device screens, it is useful to look first at the phenomenal growth that the traditional movie industry in China has enjoyed lately. The most direct data point is the rapid growth of traditional cinema screens. Fueled by China's massive growing urban population, the number of movie screens has increased at a tremendous rate in recent years, and there is no sign of it slowing down. In mid-2015, the opening of the domestic comedy movie Lost in Hong Kong had an unprecedented 100,000+ first-day screen showings on nearly 20,000 screens, marking the widest release in global cinema history.

Although China has already surpassed Japan to become the second-largest film market in the world just below the US, its screen saturation (people per screen average) still has a lot of catching up to do. By the end of 2014, China had about 24,000 screens for nearly 1.4 billion people, versus the US which had 39,000 screens for approximately 300 million people. In other words, in 2014 China had about one screen for over 60,000 people and this is creating about one per 8,000 in the US. With the same level of saturation as in the US, China would have around 160,000 screens (close to seven times the current number).

Given that China has more densely populated cities than the US, one could argue that the US per screen average is not directly comparable to that in China. The neighboring Korean market might be a better reference, with approximately one screen for every 20,000 people. Even at that level, China could be projected to have around 70,000 screens. According to the data from China's State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television, in 2015 more than 8,000 screens were added in China (roughly 20% of the total screens in the US, see Figure 7.1), at a rate of 22 new cinema screens per day. This expansion may continue for years to come, as movie screens continue to reach smaller urban centers across the country.

Figure 7.1 The Rapid Increase of Cinema Screens in China

(Data Source: China's State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television, 2015)

The expansion of big screen theater company IMAX Corp in China is a good example. China is a critical growth market for IMAX as many Chinese consumers, with new disposable income, are trying out IMAX theaters and 3-D films for the first time. According to company data in mid-2014, IMAX had built more than 170 theaters in China since 2004, and it planned to open more than 246 screens in the following five years. (In comparison, there were 340 IMAX screens in North America at the same time.) The China market is set to surpass the US and become the Canadian company's number one market globally.

Corresponding to the rapid increase of movie screens, box office receipts – an equally important data point for the industry – have risen rapidly in China as well. If the appetite of Chinese consumers maintains its growth rate, China will be on track to surpass the US to become the world's largest box office market in just a few years.

According to data from the Beijing-based film research company EntGroup, in 2014 Chinese box office receipts rose 36% from the previous year to reach $4.77 billion. The Chinese market's rapid growth in 2014 was a remarkable exception since the global box office was up only 1% from the previous year and global attendance was flat or declining in most markets around the world. In particular, the US and Canada saw their box office receipts fall by 5% and the key 18 to 39-year-old audience group shrink to its lowest levels in five years, according to a report by the Motion Picture Association of America. In 2015, China's box office takings leapt by nearly 50% from 2014, the fastest annual growth rate since 2011.

The rapid growth of the China movie market has not gone unnoticed by Hollywood. For years, however, the quota on foreign-made films imposed by the Chinese government was a major entry barrier for foreign movies. Historically there was a cap on the importation of foreign movies at 20 pictures per year, and the foreign studios only received a small share (13.5% to 17.5%) of box office revenues. In a positive development for Hollywood, in 2012 the Chinese government lifted the quota to allow 34 movies to be shown in China each year, provided that the additional 14 movies are in 3-D or IMAX formats. Foreign filmmakers’ share of Chinese box office receipts (after costs) was also increased to 25%. “Co-production” movies jointly made by Chinese and foreign studios could be exempted from the quota and the foreign partner could have a bigger share in the box office proceeds. (This promising field is discussed in detail later in this chapter.)

For Hollywood, however, the goal is always to “further open up” the Chinese film market, or even to “completely open it up”. This current quota system is part of a memorandum of understanding agreement between China and the World Trade Organization (WTO) concluded in 2012 and valid for five years. (Incidentally, this quota system is also being applied to TV programs from abroad, with video-hosting sites expected to register foreign content with the authorities.) This means the second round of negotiations will start around February 2017, and Hollywood and other foreign studios (such as those in France) have high expectations that the Chinese government will further relax its quota restricting foreign movie imports.

Since China is a major growth area in an otherwise flat or declining global movie market, the Hollywood studios have pursued it aggressively. The Hollywood blockbusters now have budgets often exceeding $400 million, so to be able to make $100 million or more at the box office in one market is really significant. (When Avatar achieved more than $200 million at the box office in 2010, China was no longer an afterthought as a market.) Instead, movie producers are going to great lengths to make sure their works appeal to both markets, and finding the quickest way to reach the greatest number of Chinese movie-goers has become one of their top priorities.

So far, the Hollywood studios have made significant progress in capturing the Chinese audience. As illustrated by Table 7.1, in 2014 six US studios managed to make more than $100 million at the box office in China. Partly shot in China and with the climax of the movie set in Hong Kong, Paramount's Transformers: Age of Extinction was the best-performing movie in China in 2014, and the $320 million which it achieved at the box office overtook Avatar to set a new record. Even more remarkable, the film's box office takings in China exceeded its North American gross figure of $245 million by a margin of $75 million (based on data from Box Office Mojo), marking a game-changing moment in the dynamic between the top two movie markets in the world.

Table 7.1 Aggregate China box office receipts of US studios in 2014

| Studios | 2014 Rank | Aggregate Box Office in China ($ million) |

| Paramount | 1 | 418 |

| Disney | 2 | 375 |

| Warner Bros | 3 | 358 |

| Fox | 4 | 310 |

| Sony | 5 | 164 |

| Dreamworks Animation | 6 | 122 |

| Universal | 7 | 52 |

| Lionsgate/Summit | 8 | 23 |

(Data Source: Pacific Bridge Pictures Research, 2014)

The year 2015 also saw six Hollywood studios making more than $100 million at the box office from China's film market (see Table 7.2). Universal, which failed to reach that milestone in 2014, took the top spot in the market in 2015, thanks mostly to the wild success of Furious 7. In only 8 days the movie grossed $250 million in China, and its total 2015 gross in China was nearly $400 million, making it the biggest film ever at China's box office. Furious 7 ’s success demonstrated that big budget, effects-driven, Hollywood action spectacular movies are still what the Chinese audiences love best.

Table 7.2 Aggregate China box office receipts of US studios in 2015

| Studios | 2015 Rank | Aggregate Box Office in China ($ million) |

| Universal | 1 | 711 |

| Disney | 2 | 532 |

| Fox | 3 | 285 |

| Warner Bros | 4 | 275 |

| Paramount | 5 | 259 |

| Sony | 6 | 121 |

(Data Source: Pacific Bridge Pictures Research, 2015)

The Chinese market is therefore at the center of global studios’ future strategy. For years, foreign players have faced challenges when navigating the complex cultural, financial and political issues relating to viewers, partners and government in China. As a result, they look to local industry partners for a smooth entry into the world's second largest movie market. In the internet age, however, even domestic film companies themselves are searching for their new positioning. For one thing, the traditional film industry model is being disrupted by complex interactions between online firms and offline cinemas. For another, young, urban Chinese movie fans as the mainstream movie-going group are making their tastes known through social networks and mobile apps. So-called So-Lo-Mo trends are bringing new challenges and opportunities for both Hollywood and Chinese movie studios.

So-Lo-Mo (Social-Local-Mobile)

“So-Lo-Mo” is an abbreviation for Social-Local-Mobile, the three powerful trends reshaping China's film industry in the digital age. Until just a few years ago, China's movie industry resembled Hollywood in the 1930s, when studios controlled all business lines – from talent to production to theaters – before a 1948 Supreme Court ruling forced them to divest. In China this practice was called “being a dragon from head to tail”, whereas the public audiences were passively on the receiving end. Today the internet element not only transforms the business model, but also has a huge impact on movies’ content and production. For new films in China, their idea creation, movie production and marketing campaigns are increasingly shaped by big data and executed via social media (see Figure 7.2).

Figure 7.2 Mobile Internet Through the Life Cycle of a Movie

On “Social”, the social networks provide a powerful link between movie-goers and movies at every stage in the life of a movie. It seems that in future movies will be triggered more by the “tail” (the end-users) via social networks, and mobile internet empowers movie fans to get involved in the whole life of a movie, from beginning to end (or as the Chinese saying goes, “from head to tail”).

The importance of social networks is felt right from the idea creation stage. Before the internet age, it was very hard for young screenwriters in China to emerge, because a handful of producers working with a small number of screenwriters controlled almost the whole market. As discussed in the previous chapter, the internet has leveled the playing field for aspiring young writers, and many online novels have been adapted into feature movies. The popularity rankings of online literature provide movie makers with important information on potential movie-goers’ constantly-shifting preferences for storyline and genre; hence more and more directors actively search the internet for potential hits.

In a more direct way, consumers increasingly make their preferences known to the directors and producers through social media. On a general platform like WeChat or a specialized movie review site like Douban, movie fans comment on the latest movies and make suggestions. Rather like having dinner at a restaurant, they would prefer to have their favorite dishes made to order than wait to see what the chef is cooking.

Meanwhile, the studios are proactively using big data analytics to find consumers’ focus areas. Even after a decision on a movie production is made, directors may still use social networks to interact with fans, because their feedback and comments not only help to polish the “base” online novel for the movie screen, but also create free marketing even before the movie is made. In short, the new studio model is: let us know what you like to watch (simultaneously we will try to figure out your taste preferences using big data technology), and then we will produce it for you.

For instance, starting with the 2011 hit Love is Not Blind, there have been a series of successes in turning online young adult novels into blockbusters, such as the 2013 drama So Young, which was adapted from the novel To Our Eventually Lost Youth. The Tiny Time series is by far the most successful example of all. Its author Mr. Guo Jingming was one of the top-tier online authors – the so-called “zhigaoshen” (the Supreme God) class of writers, with nearly 20 million followers. Based on social network popularity – of both the novel and Mr. Guo himself – the celebrity internet novelist turned his work into a movie. Within a short time, the movie caught on in China and exceeded all expectations to become a franchise.

Of course, the successful transition of Tiny Times from an online novel directly into a blockbuster hit was exceptional. In reality, while lots of film and television companies aggressively purchased popular internet content for production, not many films or TV series lived up to the quality of the original works. Usually, an online work is trialled in the form of a micro movie or web series before studios are convinced of its potential acceptance as a feature-length movie. Take the path of Old Boys: The Way of the Dragon as an example. The story of Old Boys was a sentimental tale of a pair of struggling amateur musicians in China who called themselves the “Chopsticks Brothers”. It first went online in 2010 as a 43-minute micro online movie. After it received tens of millions of online views and its theme tune Old Boys became popular, the story was turned into a full-length movie, which became one of the hits of 2014.

In addition to movie story choices, social networks also help to shape the choice of production team. Again, to use the example of Tiny Times, before Mr. Guo Jingming became a first-time producer-director, he checked with his fan base for advice. The production company also tapped into Weibo (the Chinese Twitter) for suggestions on the director and stars of the films from over 100 million Weibo followers. The feedback was somewhat unexpected because the fans suggested that Mr. Guo himself should be the director, an important reason being “to preserve the original flavor of the novel”.

The new generation of movies are also increasingly using social networks for production financing. Movie crowdfunding has attracted the interest of many young audiences, and it is quickly becoming an important funding channel for movie production companies. (Detailed discussions relating to internet finance will follow in the next chapter.) When Tiny Times reached the third and fourth sequels, young fans were offered the opportunity to invest in the production for as little as $15. They were excited to be “co-producers” of the movie and appreciated the chance to visit filming locations, receive stars’ autographed photos and even meet the stars.

Furthermore, at cinemas the “social” aspect is still visible when a movie is put on the big screen. Selected movie theaters in China have experimented with the “bullet screen” – a new model that enables viewers to chat about the films via text messages on the movie screen while they watch. (See the “Bullet Screen” box.) The “bullet screen” with social interactive features was invented in Japan, and was mostly used in the video streaming context to provide individuals with a virtual “watching together” experience (while watching online videos alone). However, as a testimony to the popularity of social networks in China, some movie theaters have boldly added this feature to the big screen, using the bullet screen in an already “physically watching together” setting.

There is still debate about whether the bullet screen is simply a marketing trick or a major model revolution for the movie industry. For some audiences, the bullet screen is a distraction from movie watching; for others, it is an additional social interaction to enrich the overall movie watching experience. Most likely, the bullet screen is here to stay due to young audiences’ strong desire to express their views. To them, while the director defines the storylines on the movie screen, the bullet screen is a parallel screen of their own to provide feedback on the movies. In future, specialized bullet screen cinemas equipped with cutting-edge technology may emerge, like the IMAX theaters, and it's likely that every cinema will set aside a special section dedicated to bullet screen viewers.

Finally, an important activity for young netizens after watching a movie is to comment on and discuss it on social networks. As a result, even after a movie's release the fans are still influencing its destiny through their movie reviews and comments on social media. For the movies they like, young Chinese fans may exhibit quasi-religious zealotry, whipping up a frenzy or defending it against criticism like an army of loyalists.

For example, when Tiny Times’ emphasis on high-society life and material gratification stirred up controversy in China, its loyal fans on social networks – mostly young girls like the heroines in the movie – defended the film with fervent counterattacks. By contrast, the power of social networks is also obvious when viewers reveal their dislikes. In 2014, the 3-D film Gone with the Bullets was hotly anticipated because it was directed by Jiang Wen, whose 2010 satirical hit Let the Bullets Fly set box office records. But when negative reviews started spreading rapidly via social media, the film's box office suffered.

The second element is the “local” trend, which is both more subtle and more profound than the social network factor. With mobile internet providing Chinese consumers not only with more content, but also with more ways to find it, they have turned the tables, becoming “choosers” in consumption. Probably to the surprise of many, this does not necessarily mean that foreign content, in particular Hollywood movies, is the clear winner in “high quality content”. In fact, local audiences are increasingly open to domestic productions, which for a long time had only a small market share due to the dominance of blockbuster imports from Hollywood.

Among the top 10 China Box Office performers of 2014, domestic and foreign movies were split 50/50 (see Table 7.3). The Hollywood blockbuster Transformers: Age of Extinction ranked No. 1, but it was the only foreign movie in the top 4. According to data from the State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television, in 2014 local productions took 54.5% of China's total box office.

Table 7.3 Top 10 China box office performers of 2014

| Rank | Movie Title | Gross ($ millions) | Domestic/ Foreign |

| 1 | Transformers: Age of Extinction | 320 | Foreign |

| 2 | Breakup Buddies | 187.97 | Domestic |

| 3 | The Monkey King | 167.84 | Domestic |

| 4 | The Taking of Tiger Mountain | 141.02 | Domestic |

| 5 | Interstellar | 121.99 | Foreign |

| 6 | X-Men: Days of Future Past | 116.49 | Foreign |

| 7 | Captain America: The Winter Soldier | 115.62 | Foreign |

| 8 | Dad, Where Are We Going? | 111.87 | Domestic |

| 9 | Dawn of the Planet of the Apes | 107.35 | Foreign |

| 10 | The Breakup Guru | 106.59 | Domestic |

(Data Source: Box Office Mojo, 2014)

In 2015, domestic movies gained even more ground and claimed 7 out of the top 10 box office spots (see Table 7.4), amassing almost two-thirds of total box office receipts (61.6%). For three years in a row (2013–2015), domestic producers gained a bigger share of the market than Hollywood. It is worth noting that in 2015 only action and adventure movies from Hollywood made it to the top 10 box office spot, clearly suggesting that the new generation of movie-goers have strong views on the movies they like to see. Therefore, it is critical for Hollywood studios to better understand the new dynamics in China's market to ensure their movies remain relevant in the world's soon-to-be largest movie market.

Table 7.4 Top 10 China box office performers of 2015

| Rank | Movie Title | Gross ($ million) | Domestic/Foreign | Genre |

| 1 | Furious 7 | 390.91 | Foreign | Action |

| 2 | Monster Hunt | 381.86 | Domestic | Fantasy/Comedy |

| 3 | Lost in Hong Kong | 253.59 | Domestic | Comedy |

| 4 | Mojin: The Lost Legend | 252.01 | Domestic | Action/Adventure |

| 5 | Avengers: Age of Ultron | 240.11 | Foreign | Sci-fi |

| 6 | Jurassic World | 228.74 | Foreign | Action/Adventure |

| 7 | Goodbye Mr. Loser | 226.16 | Domestic | Comedy |

| 8 | Pancake Man | 186.35 | Domestic | Comedy |

| 9 | The Man from Macau II | 154.13 | Domestic | Action |

| 10 | Monkey King: Hero Is Back | 153.02 | Domestic | Animation |

(Data Source: Box Office Mojo, 2015)

The success of homegrown dramas illustrates a remarkable recent evolution in Chinese audiences’ tastes. And it seems that Chinese producers have adapted more quickly to local audiences’ preferences. (Of course, the US studios have to deal with scheduling issues. They are also sometimes given relatively short notice on release dates, making it more difficult to manage marketing campaigns.) The 21st century Chinese audience have seen enough spectacles, explosions and special effects from Hollywood movies. The challenge for the Western producers is to find something relevant to this generation that keeps them engaged, or to find something new that gets them excited. Most of the successful domestic movies have had some kind of social message that resonated with audiences.

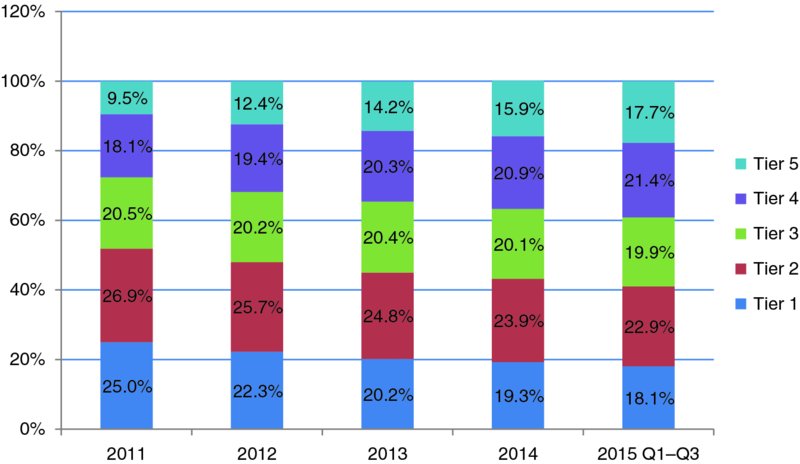

Once again, possibly to the surprise of many, the mainstream “themes” of movies are not necessarily defined by audiences in the top-tier cities like Beijing or Shanghai. Instead, they are increasingly defined by “small town youths”, a term that covers young movie-goers in tier 2, 3, 4 and 5 cities, essentially all youth audiences in urban centers other than the tier 1 cities. According to the White Paper on Small Town Youths by the Ent Group at the end of 2015, during the last few years movie-goers in tier 1 as a percentage of the total market had decreased steadily, while the smallest tier 4 and tier 5 cities were on the rise (see Figure 7.3). This growth is not that surprising when one considers the increasing penetration of mobile internet across the country.

Figure 7.3 Tier 1–5 Cities’ Share of Movie-Goers (2011–2015 Q3)

(Data Source: Ent Group, September 2015)

The emergence of “small town youths” is an important reason for the “going local” trend in China's movie market. In the case of the Tiny Times series, the story centered on the individualistic pursuit of happiness and success, resonating with the young audience, with its exaggerated high-class life full of branded luxuries – everything young movie-goers dreamed of having, but doubted they would ever attain. In particular, the path of the film's protagonist was every Chinese college student's dream: She began the story as an ordinary university student, and then had to face things like job interviews and intimidating bosses in the workplace. But she managed to pull through and her life became better and better – she had a glamorous career, great friends and a handsome boyfriend.

Put another way, the storylines of Tiny Times and the like, which covered the aspirations, insecurities, struggles and stress of the new generation, had filled a void in the traditional domestic movie market. For a long time, at one end of the spectrum of available movies were the movies from the older authors and directors in China, to which young people could not relate or did not even try to understand. At the other end of the spectrum were foreign movies that appeared too remote and random for the “small town youths”. The majority of the young audience like stories from authors of their own age, and they admire fashionable, popular and successful heroes that are also home-grown. To capture the market share in China, Hollywood movies have to adapt to the rapid increase of the “small town youths” at cinemas.

However, this new trend also raised questions about movie quality and the ultimate sustainability of China's movie market. Some film critics lamented that few of the movie hits in recent years had any real critical success, and they suggested that big data on consumer preferences may be skewed by the boom in the new audiences from China's smaller cities. In line with the critics, many hit movies of recent years, including Tiny Times, were selected by online polls to receive the Golden Broom Awards for “the most disappointing films, actors, directors and scriptwriters” of 2014 and 2015 (see the “Golden Broom” Box).

Finally, on the “mobile” side, the internet and smart devices are becoming the main medium linking the movie market and Chinese audiences. At the 2015 Shanghai International Film Festival, the organizing committee released its first ever report on the trend of “internet movies” in China, and its data showed that the internet had become one of the most important marketing channels for Chinese movies. 75.27% of Chinese film viewers decided to watch a movie because they had read the original network fiction, played related online games or watched animations through the internet.

As such, digital marketing has become critical in China's increasingly competitive movie market. In smaller urban centers like tier 3 and lower cities, the internet may be the only cost-effective way to reach the potential audience. Mobile channels are especially important because for small town youths, their smartphones may be their only access to the internet. If young movie fans could be motivated to share movie information on social networks, a movie can potentially achieve far better coverage than by traditional offline advertising. These days the major social networks WeChat, Sina Weibo and Renren (a college-focused social network) are the main portals for online marketing. Meanwhile, specialized movie sites Mtime and Douban have also emerged as centers of movie reviews and scheduling information.

In the case of Tiny Times, for example, the film's producer and distributor Le Vision Pictures (the film arm of China's tech and media conglomerate LeTV), claimed that it did not put up one single advertising billboard across the country. Instead, knowing the fans are mostly high school students and young adults, it did most of the film's marketing activities through social networks. As a result, the production company not only saved a lot on advertising spend, but also claimed 85% accuracy in predicting box office returns by tapping into users of Weibo, Renren and Douban (an entertainment-focused social network).

In addition, mobile internet technology has also changed the way movie-goers pick a cinema nearby and book movie tickets in advance. It's a classic O2O connection between online activities (social network, screenings and location search) and offline activities (cinema going and popcorn promotion deals). As discussed in the earlier O2O chapter, the major O2O market players are approaching this sector from their different strengths – Baidu's mobile search engine, Alibaba's e-commerce big data, Tencent's messaging service and social media, and Wanda's shopping malls and cinema chains.

These big four are in a fierce price war to win the market share for online movie ticket sales. All three internet firms (BAT) have discount ticketing service subsidiaries, and Wanda has also linked interactive mobile apps with its theaters across China. Movie ticketing was an area where traditional movie theaters failed to provide convenient services in the past, due to a lack of investment in technology. Movie theaters used to post their schedule in the middle column or service page of local newspapers. Now the mobile ticketing service provides viewers with the most up-to-date movie schedules, location information of movie theaters, cheap tickets (thanks to the subsidies of the big companies) and seating reservation ahead of the showing. Collectively, the mobile apps have made an offer that movie-goers cannot refuse.

As a result, the market has seen a jump in the number of people using online systems and smartphones to buy movie tickets. In just a few years, online ticket purchases moved from zero to over 50% of the market and have become the mainstream channel. According to Baidu founder Mr. Robin Li's presentation in mid-2015, 55 out of 100 movie tickets were sold online, whereas in the US only 20% of movie tickets were booked online. Of course, the same question has arisen in the movie market as in other O2O sectors. There are concerns that the current discounted ticketing model is not sustainable because sooner or later major firms have to phase out their subsidies in the search for profit.

As with O2O dining services discussed earlier in this book, the core issue in price wars is about the “stickiness” of the new movie-goers, who are not necessarily avid movie fans, but are attracted to cinemas by the deeply discounted ticket price. For now, however, the enormous subsidies are also justified by the major firms as a way of gathering big data, which can potentially help them better understand audiences’ preferences for movie productions. In fact, the big four players’ ambitions extend beyond connecting Chinese audiences with domestic and Hollywood movies, and they have all set up their own movie production units. They actively search for and team up with popular online novels to produce domestic movies. They have also entered into numerous partnerships with prominent writers, producers, actors, directors and studios from Hollywood to work on co-production movies for the Chinese market.

For example, Alibaba's film unit made its first-ever US film investment in Paramount Pictures' blockbuster Mission: Impossible – Rogue Nation, starring actor Tom Cruise. In fact, at the WSJ 2014 JD conference, Alibaba's founder Jack Ma said the company was already “the biggest entertainment company in the world”, because Alibaba was involved in the entire supply chain from investment and production of content all the way to marketing and distribution of the movie. More recently, in early 2016 Wanda acquired Legendary Entertainment, one of Hollywood's biggest movie production companies for approximately $3.5 billion, and Wanda described the deal as “China's largest cross-border cultural acquisition to date”.

It is worth highlighting that Wanda also has an unrivalled offline base for the movie business. Aside from being the largest owner of movie theaters and shopping malls in domestic China, it also acquired AMC Theaters, one of the largest cinema chains in North America, for $2.6 billion in 2012. Its more ambitious project, the Oriental Movie Metropolis (which aims to be the Chinese version of Hollywood), broke ground in 2013 at Qingdao City in Shandong province. This studio complex had a huge budget of $8 billion, which included film studios, movie theaters, a theme park, a film museum, a wax museum and resort hotels.

Therefore, whether “Content is King” or “Channel is King” is not a real question for the big players. With abundant capital, the “big four” are spending huge sums on both sides and positioning themselves as the global studios and distributors of the future. The related question, however, is on the sustainability of exceptional growth in China. In other markets, the low-cost entertainment options on electronic devices have led to less movie-going for young people. Is the Chinese market so different that it could buck the global trend? In China, will online entertainment screens eventually take away audiences from the big screen as has happened in the developed markets?

So far there is no data pointing in that direction, as Chinese movie fans seem to want both the cinema and the mobile-device experience. As big movie screens and mobile internet continue expanding their reach into small cities and rural areas, more “small town youths” are becoming movie-goers, and the market will likely see continued robust box office record-setting over the coming years. Of course, the film industry has already started working on ways to defend its market share. Cinemas equipped with bullet screens have tried to provide the same social interaction during movie watching as viewers have in the context of online video watching. The social and mobile components of movie watching, therefore, may soon blur the separation between big screens and small screens.

Hollywood's Changing DNA

The SoLoMo trends have not only transformed China's movie industry, but also had profound implications for Hollywood studios’ business model in China. The internet-led boom in market size, together with more internet firms becoming movie studios themselves, provides more revenue opportunities and partner selections for Hollywood. At the same time, they need to have a better understanding of the DNA of the new “internet +” film business in China.

In particular, internet distribution and promotion channels have disrupted market dynamics, and Hollywood studios have to rethink their intellectual property rights at play in China in the new mobile, multi-screen context. Traditionally, Hollywood studios pay most of their attention to box office revenue in China, but online business is expected to bring greater revenue into the mix soon. According to industry estimates, although online revenue is currently much smaller compared to box office revenue, it may catch up with or even exceed the latter within the next decade.

Interestingly, the popularity of pirate DVDs in China may contribute to the development of the online movie market. In Western markets, movies go through a very clear “windowing” process. They appear exclusively in theaters for a period of time (traditionally a few months) before they move to DVD, and later to online distribution services. The major theater chains control the majority of movie screens in the United States, and they have aggressively opposed suggestions to shorten their release window for fear that audiences will be enticed to stay home instead. In China, windowing has not really developed, because the popularity of pirate DVDs means there is no legitimate DVD market.

Therefore, mobile internet players reason that the Western studios maybe be better off distributing movies online in China more quickly than before. The logic is that online channels can help to get the movies into the Chinese market before the pirates do, making it convenient for people to watch and pay. It follows that, by offering consumers a legitimate way to watch new films in a timely fashion, audiences may not bother looking for pirated products. (In the past, pirated DVDs were traditionally the fastest way for Chinese audiences to get access to a new movie.) Compared to a decade ago, new generation audiences are keen to enjoy the best movie watching experiences, so low quality pirated DVDs lose their appeal quickly if an authentic copy is available.

In other words, if content is distributed more quickly, audiences may be more willing to pay to watch it on mobile devices for the sake of convenience and quality rather than watching pirated DVDs. For example, in 2015 iQIYI charged just under $1 for Chinese audiences to watch new releases online, which was the same as the cost of a pirated DVD. Thus, if the mobile online distribution model is well utilized and managed, it could provide a good solution to the intellectual property issue, but the window period between cinema release and online distribution needs to be reduced or even eliminated in China. Otherwise, after a long window period, even a hit Hollywood movie may become an old movie by the time it is streamed in China. (In all likelihood, a large number of Chinese audiences would already have resorted to another medium to view it.)

For example, when Tencent entered into a Netflix-style streaming service in 2014 with Warner Brothers (which has a minority stake in the joint venture), the two arranged to deliver movies to homes across China just two weeks after their US cinema release. The 2014 hit 300: Rise of an Empire was among the first batch of titles available to rent in China when the film was still showing in cinemas in the US and other markets. In future, the “windowing” period in China may shrink further when one looks at Netflix in the US as a reference.

In August 2014, the sequel to the martial arts drama Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon and the four Adam Sandler movies were released simultaneously across the globe on Netflix and in IMAX theaters. It was the first deal of its kind, where major motion pictures make their debut on the streaming service and in movie theaters at the same time (that is, eliminating the theater window altogether). The US studios and cinemas were generally doubtful whether the loss of revenue from cinema patrons would be sufficiently compensated by the audiences watching movies at home, because movie ticket prices were substantially higher than the streaming price.

But some were more optimistic that the new model could potentially create a bigger pie. When Lionsgate launched its film Arbitrage simultaneously in theaters and on “video-on-demand”, its chairman was reportedly happy that the movie “found two different audiences”. Most likely more US stars, directors, studios and theater chains will accept straight-to-streaming deals in the near future, in the same way that Netflix has shaken up the television model. TV shows used to follow a similar “window” system, but they are now available for streaming immediately after or very soon after they are broadcast on TV networks.) When the window of theatre exclusivity in the US shrinks further, Hollywood studios should find it both easier and more profitable to embrace Chinese mobile viewers in a more timely way.

As the intellectual property rights protection of movies in China continues to improve (the same is true for videos, as discussed in the previous chapter), the market may see more direct cooperation in content production between Hollywood and Chinese movie studios. The biggest potential is in co-production movies, which have long been viewed by Hollywood studios as a new way to gain a bigger slice of China's booming film market. When officially designated as a US–China co-production, a movie can be treated as a domestic film to bypass China's import quota on foreign films, and the foreign producer could get a bigger share of the Chinese box office than with an imported Hollywood movie. Furthermore, working with Chinese partners helps distribution tremendously. The rumors and stories of local actors involved in blockbusters like Transformers, for example, created a valuable marketing opportunity even before the film's official release in China.

But it won't be easy for a movie to be all things to all markets. Around the world, almost every market focuses on two kinds of films – domestic films that resonate with local lives and Hollywood blockbusters. Due to cultural dissimilarities and the language barrier, finding subjects deemed suitable for both Chinese and US audiences has proved tricky. Over the past decade, co-production works have met with varying degrees of success, as the studios are still struggling to balance Chinese elements with international box office considerations.

Although some Hollywood blockbusters have added Chinese settings and co-stars, they have been at best Hollywood stories with Chinese sub-plots and arbitrarily inserted characters. Transformers: Age of Extinction in 2014 was one of the best-performing movies in China, but it was essentially two movies under one title. As the story developed, action shifted from Texas and Chicago to Beijing, with the final 30-minute all-out robot war taking place entirely in Hong Kong. The 2013 movie Iron Man 3 was filmed in two different versions. The Chinese version had four extra minutes of footage featuring Chinese actors and locations, and another version with most of those scenes cut for international release.

In addition, for the purposes of co-production categorization, multiple product placement deals with Chinese consumer brands are also incorporated into the movies. This begs the question whether they pose challenges to the story's coherence (or become hilarious as in the case of Transformer). (See the “Inserted from China” box.) Market feedback has been clear: forcing “Chinese” elements into films is not the key to success. Even with Chinese fingerprints all over a film, its co-production is not organic if the elements are added in a random way, and the audiences can easily get tired of such awkward combinations.

Two-Way Co-Production

Along with the boom in the domestic film market, Chinese studios are moving up the value chain, helping to develop, design and produce world-class films and animated features. They are taking bigger roles, financially and artistically, in the creative process when collaborating with Hollywood than in the past. Naturally, their ambition is to make Hollywood-scale movies for global audiences. Thus an intriguing expectation is that China's film companies – both the traditional ones and the internet firms – will reverse the co-production equation to create Chinese movies with global appeal.

In a “reversing” co-production, the challenge is flipped accordingly. Rather than adding Chinese elements to a US movie, the producers need to find Chinese stories that could travel globally. Then they may also have to incorporate foreign elements and locations to attract overseas viewers. Such Chinese films will create storylines as a “Hollywood way of looking at China”. Meanwhile, they have to learn about better storytelling from the established foreign film industry to have “a Hollywood way of presenting China”. If that happens, China's movie market will not only surpass the US as the largest consumer of movies, but also emerge as a powerhouse of movie production in the world.

So far, China has yet to become a major exporter of film. Successful recent homegrown movies have had limited success in the overseas market, even though their box office numbers in the domestic market are already on a par with Hollywood blockbusters. The challenge for Chinese playwrights is to identify stories that will resonate with people from different cultures. To date, the situation in China's movie industry is similar to that in India, where the productions are mostly viewed within the country.

Take the 2013 hit movie Lost in Thailand as an example. Lost in Thailand was a contemporary comedy about a pair of co-workers competing to find their company's largest shareholder in Thailand to secure a contract for some coveted technology patent. With a preposterous plot and flamboyant characters, the movie presented Chinese audiences with exactly what they wanted: popular stars, funny dialogue and a subtle reflection on the ambitions and anxieties of China's growing urban middle class. For many new middle class people who feel confused and exhausted by the increasing demands of modern life, the movie resonated with them as a story about “losing themselves”.

In China, Lost in Thailand was considered a comedy, presenting “contemporary China” in a jokey way. Even for Chinese audiences, this film style was a novelty. This low budget production (just under $5 million, according to news reports) was a big commercial success in China: it knocked Life of Pi off China's No. 1 spot in the month of its release and its box office exceeded Titanic 3D. When the movie was shown in US cinemas a while later, many had high expectations and even considered it a Chinese version of The Hangover. (The Hangover 2 took place in Thailand as well.)

However, the domestic box office success of Lost in Thailand did not travel well; instead, the movie got lost in translation. At its weekend opening, it was reportedly shown in a mere 29 cinemas in the US and took less than $30,000 over the weekend. Maybe the humor of Lost in Thailand was simply too Chinese to connect with foreign viewers. But even before the box office consideration, the mere fact that the cinema chain distributor AMC decided to treat it as a niche movie and showed it on only 29 screens throughout the US provided important feedback: it may take some time before US movie distributors have strong confidence in Chinese movies’ broad appeal.

What seemed to be promising, nevertheless, was the respectable performance of its 2015 sequel, Lost in Hong Kong. The state-side distributor Well Go USA released the film in North America on the same day as its Chinese launch, and although it was only shown in 27 theaters in a limited day-and-date North American release, it reportedly had solid success, earning more than $500,000. Also in 2015, another successful home movie Pancake Man had a successful premiere in North America over the opening weekend. Pancake Man was the tale of a poor street pancake vendor who gained miraculous super powers from the pancakes he served. Because the Hollywood film industry had long dominated the superhero movie genre, it was quite an achievement that a new superhero franchise from China could join the mix.

The most important reference point may come in the near future from a “reverse” co-production that is in the making. A fantasy adventure movie called The Great Wall is to be jointly produced in 2016 by Legendary Entertainment and Universal Pictures on the US side, and China Film Company and Le Vision Pictures on the China side. With a $150 million budget, The Great Wall is one of China's biggest productions to date, the largest film ever shot entirely in China for global distribution (a “reverse” from traditional co-production US movies).

In fact, the movie story is fundamentally China-centered. It is set in China hundreds of years ago, involving an army of elite warriors who must transform the Great Wall into a weapon “in order to combat wave after wave of otherworldly creatures hell-bent on devouring humanity”. Legendary described the story as “an elite force making a last stand for humanity on the world's most iconic structure [the Great Wall in China]”, which has secrets hidden beneath the ancient stones. The IMDb website similarly has a one-line summary of the film for interested Westerners: “A mystery centered around the construction of the Great Wall of China”.

The ultimate “reverse” probably results from the fact that the movie director Mr. Zhang Yimo is a Chinese native who does not speak English. Even though his prior productions including Raise the Red Lantern, have won international awards, this is Mr. Zhang's first attempt at a film primarily in English. That could be a challenge for the foreign partners, but the upside for the US production company Legendary Entertainment and Universal Pictures is that, with a Chinese director, together with the large Chinese cast, Chinese locations and Chinese capital investors, the movie easily qualifies as an official Chinese co-production rather than a Hollywood movie with some added Chinese flavors.

This movie is due for global release in November 2016 and US and Chinese film studios will watch it closely to see how enthusiastically the markets accept it. The fundamental risk is the same as for a typical co-production movie: that is, The Great Wall may be too Chinese for international audiences, but still too Hollywood and foreign for Chinese audiences. However, the special theme of the movie provides some cause for optimism. In foreign markets, Western cinemas can introduce the movie simply as an English-language movie with Matt Damon and monsters (perfectly Hollywood) that happens to have Chinese themes. In the Chinese market, action spectacular is the single genre that best resists the challenges from local movies. As shown by Transformers and Furious 7, Chinese audiences love to see movies featuring monster machines that race, fly and perform gravity-defying stunts to save the world.

If The Great Wall proves to be the global blockbuster it aims to be, it may become the template for future China–Hollywood co-productions, and it may further inspire other forms of collaboration between the studios. However, even if it is successful, it may not necessarily mean that studios will be keen to copy this model aggressively. Given the scale of the Chinese movie market itself, most domestic producers would be cautious about the foreign box office potential, because when they globalize their films, the foreign components will most likely dilute the movies’ local flavor, and risk losing some domestic fans. Therefore, many producers may choose to ensure that their productions will appeal to and attract home-based fans first. As a Chinese proverb reminds people, “Don't drop a watermelon to pick up a piece of sesame”.

Still, Hollywood movie producers should find co-production a promising adventure. No matter what the relative China and US content composition equation is in a movie, if it can become a hit in these two markets, it already controls a majority of the world's viewers. As internet giants like Alibaba, Tencent and Baidu invest their way into the movie business, they are set to be the new powerful movie studios in the digital age, as well as the dominating distribution channels of the future. Already their social networks, mobile applications and big data technology have led to an incredible boom in the domestic movie market, and their partnership with Hollywood may create the new generation Chinese movies – a blend of Hollywood standards and China's unique culture, tradition and history – that appeal to global audiences.