Chapter 6

Mobile Entertainment

During the 2014 FIFA World Cup, China's national football team, ranked 103rd in the world, failed to go through to the tournament final in Brazil following the qualifying round. Despite this the mobile internet helped to create a time of celebration for hundreds of millions of fans as well as first-time watchers in China. In past World Cup tournaments, Chinese football fans simply watched the tournament on TV at odd hours (due to time differences) while drinking beer with friends. During the 2014 Brazil Soccer World Cup, people were active participants throughout the time that it was held. In addition to watching TV or online videos, they also interacted actively with their social networks to follow the games, played their own virtual games, and many used their smartphones to place bets on the games for the first time in their lives.

Gambling was generally illegal in mainland China, but provinces were permitted to run official sports lotteries that donate proceeds to charity. Reselling tickets for the sports lotteries run by provincial governments had become an industry in itself. In the 2014 World Cup season, China's internet firms operated as a platform on which the lottery centers could accept the placing of bets. Once again, the internet giants Alibaba and Tencent flexed their muscle in this mobile field, as they competed to build the most convenient and popular mobile lottery portals to help Chinese football fans participate in the World Cup.

Taobao, Alibaba's e-commerce site, promoted the World Cup lottery on its front page, and online shoppers could purchase tickets easily. Tencent naturally built up its interface around WeChat, the most popular social network platform in China. WeChat users could buy tickets while comparing information and thoughts about the teams with their friends. As a result of their mobile apps, soccer lottery purchases accelerated swiftly. Millions of Chinese were drawn in by the online betting platforms’ ease of use and extensive marketing coverage on their mobile terminals. According to news reports, Taobao saw 4 million users bet on its online platform on the first day of the World Cup. Three days later that number had grown to 6 million. By July 5, three weeks into the World Cup and still way before the Cup final, China's National Sports Lottery Center calculated that $1.5 billion in “lotto tickets” had been purchased.

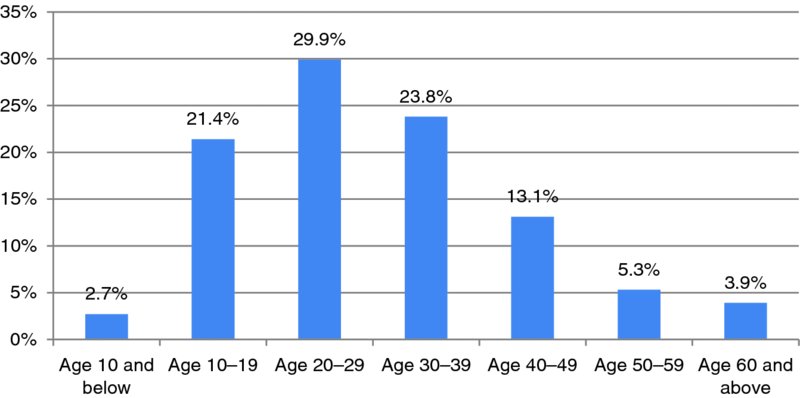

The new flow of money into online sports lotteries during the World Cup is only one example of the revolution in the entertainment industries in China when users embrace the mobile internet (a perfect example of “internet plus” into non-tech markets). In fact, the ultimate theme of the internet in China centers on entertainment and fun, which has a lot to do with the dominant component of young netizens (aged below 39) within the internet population (see Figure 6.1). According to CNNIC data, by the end of 2015 more than 75% of the internet users were between the ages of 10 and 39. Close to one third of the internet population is aged between 20 and 29 (29.9%).

Figure 6.1 Demographic of Chinese Internet Users

(Data Source: CNNIC, December 2015)

Young internet users in China are more focused on entertainment services than the traditional forms of usage of the internet for information searches and email messages. For a large part of their time online, they play online games, watch videos of TV programs and movies, assume online personas in the virtual world and form online communities to have fun together. As smartphones have become the top channel for internet access in China, the young generation of users enjoy themselves whenever and wherever, increasingly consuming, sharing and arguing about the entertainment content on their hand-held devices during their “fragmented time” (for example, during a subway commute or while waiting in line) throughout the day (vis-à-vis the fixed time before a PC).

It should be highlighted that the combination of mobile terminals and online content creates different and extra demand for content, not purely a shift of consumption from personal computers (PCs) to mobile devices. The reasons relate to two features of the mobile applications on smartphones. One factor is convenience. In the earlier example of sports betting on the 2014 World Cup games, the mobile interfaces built up by the internet firms were so convenient for customers to play that many of the lottery players were not actually enthusiastic soccer fans or people that had ever bet in the official sports lottery before.

The other factor is the efficient use of “fragmented time”. For example, online literature can be read on mobile devices anywhere and anytime, which not only leads to a disruption in the physical book market, but also creates a different experience from traditional book reading (and subsequently a large group of new readers). On subways or at shopping malls, there are always people reading online novels on their smartphone screens when they have a few minutes of time available. The biggest growth potential for new demand is from people in smaller cities, who may not have PCs but are now viewing online entertainment content from smart devices.

For the internet firms, the hundreds of millions of entertainment consumers on mobile internet represent a huge business opportunity. In addition to selling physical products to those consumers, the firms are also selling digital content and entertainment, including novels, movies, TV shows and video games. But the online entertainment means more than an important vertical business line to the internet firms.

The bigger picture is that for China's major internet companies such as BAT (Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent), the entertainment business is a common strategic initiative for their respective ecosystems. When e-commerce in physical goods becomes more commoditized, unique content may become a distinguishing feature that draws users to a specific e-commerce empire and then keeps them hooked. The media content on their platforms could help keep their users engaged and prevent them from switching to competitors.

As such, all three internet giants have as their objective the building of an expansive entertainment platform that integrates online and offline entertainment. On the one hand, they compete to become “the top distributor” of content and entertainment in China, whether it is movies or TV shows, sports or gaming, music or novels. On the other hand, they become a major aggregator of content through licensing or partnership arrangements with global quality content owners, and in many cases, become producers of their own content.

As operators of powerful distribution channels, internet firms are making entertainment and services more accessible to users of smartphones and other gadgets like internet TVs. At the same time, they are becoming investors and producers of media content themselves (for example, movies and TV shows) as part of their mobile e-commerce strategy. For the existing entertainment industry players, internet firms are powerful allies and simultaneously enemies at-the-gate.

The year 2014 was probably the “breakout year” for China's mobile entertainment industry. Internet firms considered this content consumption field to be an important growth sector as China moves to a consumer-led economy, and their new capital investments led to unprecedented growth in mobile entertainment, both in terms of increased categories of content offerings and higher quality content from exclusive sources, such as partnerships with foreign content providers, for instance, HBO, NBA and Sony Music. The entertainment platforms of internet empires seamlessly cross-link online novels, publishing, gaming, animation, videos, filming as well as other derivative merchandise, with videos of movies and TV shows at the center.

Among all mobile content, driven by the wide use of smartphones, video streaming is soon expected to account for the majority of mobile internet traffic. Hence it is at the center of internet firms’ entertainment platforms and also the focus of this chapter. However, internet literature is at the upstream of the flow of IP (intellectual property) rights in the industry, as it is the base for a variety of derivative content including publishing, gaming, animation, filming as well as videos. Therefore, in what follows the online literature business is introduced before discussion of the video streaming models in China.

Online Literature

Over the past 10 years, internet literature has grown from fun sharing into a booming business with proven profitability in China. Initially, many aspiring writers posted their works on online forums with little expectation of becoming full-time web-writers. Some were serious writers whose works were not accepted by publishing houses, so they looked to the internet as an alternative publishing platform with a lower access threshold. Many more were amateur authors who simply sought any readers for their novel creation. But today, digital reading – reading through a broad range of digital devices such as smartphones, tablets, laptops and desktop PCs – has become the main way for Chinese people to read a novel; and many authors put their work online first.

The most important catalyst for the boom is mobile devices. Smartphones and tablets are becoming pocket libraries for millions of avid readers in China, and their mobile reading apps make it possible for busy urban people to read wherever they are. The CNNIC data showed that there were nearly 300 million readers of internet literature at the end of 2014. Among all reading mediums – from printed books to computers to smartphones – 84.6% of readers used mobile smartphones to read works of literature, far ahead of the usage of other tools (see Figure 6.2).

Figure 6.2 Usage Percentage of Different Reading Mediums

(Data Source: CNNIC, December 2014)

Readers' migration to mobile devices has already led to industry consolidation. Until recently, the online literature market in China was dominated by three major players: Shanda Literature, Tencent Literature and Baidu Literature. Shanda Literature, a subsidiary of the Nasdaq-listed Shanda Interactive Entertainment Limited, used to own the most popular websites and nearly 50% of the market share. Launched in 2008, Shanda was a pioneer in enabling Chinese writers to publish online freely and monetize their work through micro e-payments from readers as well as rights and licensing deals.

Despite its leadership in content, Shanda Literature missed out on the development of the mobile reading market, and it was acquired in early 2015 by Tencent Literature, whose parent company, Tencent, has mobile entertainment in its corporate DNA. After the merger, the new entity Yue-wen Group (“Reading Literature” in English) became a superpower in the online literature field with approximately 70% market share. Synergies were expected as Shanda Literature had a lot of valuable copyrighted products and Tencent Literature could potentially link them with the mobile channels and huge related user groups within Tencent, such as WeChat and QQ.

The unique feature of Chinese online literature is that most works are serialized novels that authors write and post in installments. This online serial format proves to be a perfect fit for the mobile internet age. Every day, millions of young digital-reading users refresh their mobile apps, just to keep up with the latest daily updates of their favorite reads. For many people who do not have the time to read a book in hard copy, the novels on a mobile phone can be read easily whenever they have some spare time. Each serial installment typically has a few thousand words, so the reading can be done during any “fragmented time”.

The installment format also helps the literature websites to implement a pay-for-content mechanism. When authors start to build up large readerships, the online portals offer them contracts and move their works off the free domain. The sites arrange for the authors to write a story in installments (typically with a total characters cap for each post), and readers then pay a tiny fee equivalent to a fraction of $0.01 to read each update, which is far cheaper than paying for hard copy versions from a book store. The development of mobile payment systems also makes it convenient for readers to make small repeat payments for their serial reading.

In addition to the factors above, the wish-fulfilment themes are a major reason for the enormous popularity of online novels among the young generation. While a big proportion of the readers are in China's smaller cities, calling themselves “diao-si readers” (losers) for not owning an apartment or having no girlfriend, the heroes are handsome, powerful and successful, and the sensational plots of the novels provide the readers with a way to dream of being the heroes themselves. (See the “Diao-si Readers” box.) For this, the internet authors have created many imaginary worlds for the enjoyment of their readership. The diao-si readers must feel even more empowered when they are able to change the direction of a writer's story by posting their feedback and recommendations (with charges definitely applying).

In addition to installment payments, most internet literature websites include a reward function, where readers can award the web writer money or credits at their discretion (for example, if a reader is especially satisfied by the story plot's change based on her suggestion). Some sites also publish periodical popularity rankings of online writers, which the readers must pay to vote for. The millions of online writers in China are categorized by their readers into five levels based on their income and number of fans. Except for the lowest rank, the “drop-dead on street” authors, all the professional writers in higher categories are called “gods”. But they have different titles, like the deities of the Greek pantheon (see Table 6.1).

Table 6.1 The five ranks of web writers in China

| Ranks | Number of Fans | Annual Income($) | Number of Authors |

| “Drop-dead on street” authors | Few fans, only recommended occasionally | < RMB1,000 ($150) | Numerous |

| Xiao-shen (small god) | > 100,000 | > RMB100,000 ($15,000) | Large number – foundation of sites |

| Zhong-shen (middle god) | > 500,000 | > RMB500,000 ($80,000) | Several hundred |

| Da-shen (major god) | > 1 million | > RMB1 million ($150,000) | Hundreds |

| Zhi-gao-shen (the Supreme God) | Multiple millions | Multiple millions RMB (>$1 million) | 20–30 |

(Data Source: 2015 survey by Beijing-based newspaper Jinghua Times)

Based on their online popularity among readers, many popular online novels have been adapted into traditional publishing, games, videos and blockbuster movies. As such, internet literature is the base of IP (intellectual property) rights for a variety of derivative content (see Figure 6.3). According to the data released at the 2015 Shanghai International Film Festival, by the end of 2014, 114 online novels had sold their copyrights to production companies, with 90 works being adapted into TV dramas and the rest into movies. The hit online video The Lost Tomb, which helped Baidu-owned video streaming company iQIYI's mobile app become No. 1 in the free app popularity rankings in the China Apple App store in 2015, was also a production based on an earlier online novel.

Figure 6.3 The Important Value of Internet Literature IP

At the same time, devoted fans of literary works are not only readers. They are also inclined to be loyal audiences of dramas and movies adapted from literature, or players of games and fans of animation. Overall, online literature attracts a large digital-reading user base, has a proven profit model and has the upstream intellectual property (IP) rights for inter-linked entertainment products. Therefore, it is now a key piece of every internet firm's entertainment platform.

Video Streaming: From UGC to PGC

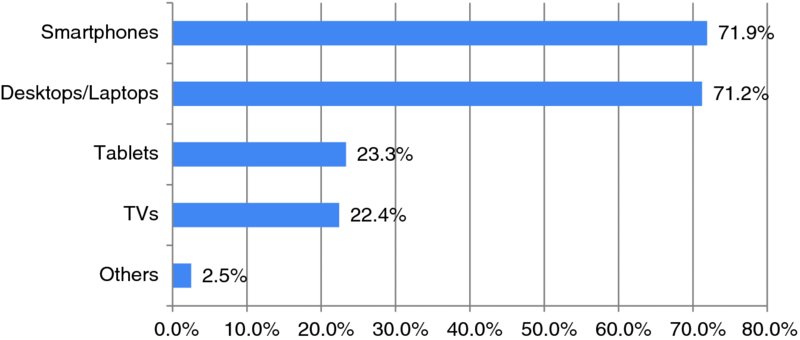

China's streaming video industry has grown exponentially in recent years, driven by the large smartphone population, the increasingly diverse selection of quality content, and the collective efforts by all stakeholders to reduce piracy. The CNNIC data showed that at the end of 2014 China had more than 400 million viewers of online videos. Among them, 71.9% of users watched online videos from their smartphones, making smartphones the leading terminal for online video access ahead of desktop computers and tablets (see Figure 6.4). The smartphone usage figure is expected to rise steadily as Chinese mobile carriers continue adopting faster fourth-generation (4G) networks that will further improve the video viewing experience on mobile devices.

Figure 6.4 Terminal Usages for Internet Videos

(Data Source: CNNIC, December 2014)

The business model of the video streaming websites is mostly based on providing free content to gain user traffic and corresponding advertising income, although the revenue income from the fee-paying internet users’ side is gradually catching up. In this ultra-competitive field, Alibaba-invested Youku Tudou and Baidu's iQIYI are the top two most watched video sites in China. As with the smartphone market, different market research firms’ data have pointed to either of the two as the top leader at different times, and between the streaming sites themselves there is disagreement about each other's statistics on active viewer hits and fee-paying members. Other major players such as Tencent Video and Sohu Video are all within striking distance. Each of them had some unique strength in their early days (see Table 6.2), but as everyone rushes to build up their content library, the various video-hosting sites are becoming similar to each other in terms of content offering.

Table 6.2 Relative speciality of the video streaming sites

| Streaming Sites | Speciality |

| Youku Tudou | Watching and uploading UGC (user-generated content); Short videos |

| iQIYI | Full-length movies; Contents related to media industry and stars |

| Tencent Video | Imported contents (NBA, HBO, Fox Sports, National Geographic, etc.) |

| Sohu Video | Variety shows; TV drama series from the US |

Youku Tudou is the combined company following a merger of the two earliest online video companies in China. Youku was established in 2006 and Tudou in 2005, so their combination created a leading position in terms of accumulated content. This competitive edge was most obvious in terms of user-generated content (UGC), because both had been rooted in user-generated, short videos. For many years these two websites were the “go-to” place for Chinese users to post self-made videos or to “shai” (show off) their experiences. As such, Youku Tudou has often been viewed as a Chinese version of YouTube. Alibaba acquired a 16.5% stake in Youku Tudou in 2014, before it bought the whole company for approximately $4.5 billion in 2015. This alliance has the potential to link e-commerce with video streaming for new businesses.

iQIYI is an independently operated subsidiary of Baidu. Baidu owned iQIYI in full before the smartphone maker Xiaomi invested to become a significant stakeholder of iQIYI in 2014 (which was part of a new “content and device integration” trend). Originally launched in 2010, it is considerably younger than Youku Tudou. But the search engine's backing has helped the subsidiary to amass a large user base quickly, because iQIYI's content is seamlessly integrated into Baidu's search and mobile services. In terms of providing full-length movies, iQIYI has something of a leadership position, because it is the first online video platform in China to focus on fully licensed, high-definition and professionally produced content. An additional speciality of iQIYI is the extensive content relating to the media industry itself along with the life stories of media stars.

Another major player is Tencent Video. Its advantage comes from the popularity of its parent Tencent's two messaging and social networking services, QQ and WeChat, which have hundreds of millions of users each. Social media and entertainment can complement each other very well, one being the catalyst for the growth of the other. The latest music and movies tend to be hot topics within the social platforms, which provides information on the content demand from the end-users, and many videos and music are being shared through the same platforms.

Meanwhile, Sohu Video (part of the internet company Sohu.com) is historically strong in variety shows, and it has also succeeded in licensing hit American TV shows for Chinese viewership. While domestic dramas and variety shows are still significantly more popular than foreign programs, American TV drama is probably the fastest growing content category in China, especially among young urban audiences. For example, The Big Bang Theory, an Emmy-award-winning show about nerdy scientists, was streamed more than 1 billion times in China. More recently, Netflix's political drama House of Cards was so popular in China that in the TV extravaganza celebrating 2015 Singles’ Day, China's online shopping spree that took place on November 11, actor Kevin Spacey made a videotaped appearance in his US presidential persona from the series.

Generally speaking, the industry trend shows that video content is shifting from user-generated content (UGC) to professionally-generated content (PGC). In previous years video sites started as “sharing” sites, so UGC videos did help those sites to attract a large number of users and capture their attention. But after a few years of industry development, Chinese viewers became more sophisticated, and pure UGC could not fully satisfy their consumption needs. In CNNIC's 2014 market survey, user-generated content ranked near the bottom of the 10 categories of programs watched by mobile audiences (see Figure 6.5).

Figure 6.5 Popularity Ranking for Video Content Watched on Smartphone

(Data Source: CNNIC, December 2014)

As Figure 6.5 shows, the most watched content category on the online video sites is TV programming. As a result, the prices for online syndication rights for hit serial TV dramas and top variety shows, such as The Legend of Zhen Huan and I am the Singer, have skyrocketed in the last few years. It may seem surprising that when people move away from their TV sets to watch programs on the internet, TV programs remain their favorite. The reason for this is that people's migration away from TV is due to TV programming as opposed to the content itself. Programs on TV have fixed schedules, long advertisements and are difficult to record and replay; the viewers have no choice but to passively accept these realities. By contrast, internet streaming technology provides the viewers with more convenience and a better experience.

The CNNIC's 2014 data showed that a majority of TV drama viewers had moved to online (see Figure 6.6). Also, 80.4% of internet TV users used the “on-demand” function, while 67.3% used the “replay” function. More interestingly, CNNIC data also showed that after smartphones as the top video watching channel, 82.4% mobile video users preferred using computers to TV for watching movies and TV dramas. This illustrated that once the viewers develop the habit of watching videos “on demand”, they are no longer willing to passively accept the pre-arranged programs on TV channels. They would rather spend far less time watching TV, potentially giving up TV altogether.

Figure 6.6 TV Drama Viewer's Migration to the Internet

It is worth noting, though, that popular professionally generated content does not necessarily consist of blockbusters or big-budget productions. Nor do they have to be perfectly executed with an intelligent storyline. In fact, many TV drama series are denounced by Chinese viewers as “brain-dead drama” or “dog-blood drama”, but people “watch and criticize” and then “watch more and criticize more”. For the viewers of those programs, the focus is not on the show itself, but rather on getting together with friends and joking about the silliness of the content. In other words, the audiences for My Love from Another Star are different from those for House of Cards, but both programs can attract a large number of viewers. (See the “Brain-dead drama” box.)

Although the viewers’ preference for professionally made content is clear (the next section will discuss the PGC content model in detail), it may be too early to declare user-generated content as being on the way out. The unique roots of Youkou Tudou's UGC, closely modeled on YouTube, may actually turn out to be a unique competitive advantage when the PGC available on competitor's websites tends to share the same characteristics. The original web-first shows made by amateurs can always potentially be turned into high quality programs once their value proposition is tested, proven and they have found traction in the market. Since movie theaters and TV stations are expensive channels, independent creative teams may first try out their production on an online platform such as Youku Tukou. In the past, low-budget original content was looked down upon by the professional industry; but in the mobile internet era, productions with online popularity quickly attract the attention of big internet companies and top studios.

For example, in 2013 a young couple from Beijing decided to take a world voyage on their 54-foot sailboat to celebrate their wedding, and they documented their trip on video in full detail. When they uploaded their 300 hours’ worth of footage to the video site Youku, the website staff members were impressed by what they had recorded. Working with the couple, Youku created a documentary series entitled On the Road. The program featured their videos across the globe, and Youku claimed it as the first website-self-made original online reality show in China. The first season of this show, which consisted of 15 episodes that were broadcast once a week, reached over 100 million views on Youku within 6 months of its release. Its second season had similar success.

For foreign studios in particular, working with existing locally-produced shows is an easier and safer way to tap into China's booming online video industry. Take the self-made comedy series Surprise for example. The original online series Surprise involved a main character Dachui Wang who, like the heroes in many internet novels, was a diao-si guy who struggled through various hilarious scenarios of modern day life. It enjoyed explosive viewership on Youku before evolving into a more professional online video production and then a feature length movie production. With more than 2 billion cumulative video views since its 2013 debut, Surprise became China's top web comedy. In 2014, Hollywood's Dreamworks Animation joined forces with Youku Tudou to produce a spate of original online content based on Surprise, and Dreamworks further planned to use the partnership as a platform to develop more content customized for the youth audience.

PGC: In Search of Revenue (and Profit)

Currently, all video services sites in China essentially have the same business model, which is to provide free content to attract online viewers and rely on advertising income as the main revenue source. Revenue from fee-paying members remains relatively small. Given the general belief that “Content is King”, all the major players compete to broaden their content offering. So far, the model has yet to prove profitable, but there are promising signs that the sector may be able to turn the corner in the near future.

No doubt, video streaming on mobile devices provides an interesting channel for consumer goods advertising due to its linkage to young Chinese customers. Young netizens are keen to try out new products, especially the ones they have seen in foreign movies or TV shows. For brands featured on quality programs, the positive impact has been substantial. The online video platforms may turn out to be a better deal than TV commercials overall; the latter can deliver large audiences, but the engagement with viewers is passive and measurement is inaccurate. Many brands have jumped on this advertisement channel bandwagon, including some wildly imaginative marketing campaigns through online videos. (See the “Naked Subway” box.)

But for all the video-hosting sites, the cost of content acquisition has far exceeded advertisement revenue, because all the players try to own the latest and greatest content to keep users on their own domain. As a result, the professionally-generated content of the various sites is quite similar, and the cost of online syndication rights for quality programs has risen rapidly. Thus the competition for content has been escalated to a fight for “exclusive” content. For example, in January 2015, Tencent Video entered into an exclusive distribution agreement with the US National Basketball Association (NBA). For the first time in China, Tencent and NBA will launch “League Pass”, a paid service that allows users to stream a full season of games live online. Just before that, Tencent Video had also become the exclusive online platform for HBO movies and Sony Music Entertainment in China.

Of course, unique high-quality content is the most expensive among all PGC. Therefore, the new strategy of the video sites is to look internally to find content exclusivity, either by partnering with media companies or setting up their own production units to create popular shows in-house. This homegrown content (also referred to as site-self-production) provides the sites with an alternative way – versus syndication or license from media companies – to stand out in distinguishable offerings, while keeping costs down on a relative basis. (In those companies’ financial reports, homegrown PGC on the one hand reduces the cost for acquiring exclusive foreign content, but also increases operating expenses on the other hand.) For example, after the Korean TV series My Love from another Star became popular on the streaming websites, the sites decided to develop their own Korean-influenced shows to meet the demand for such content.

To put this into context, the difficulty in converting views into profits and the rising cost for quality content are felt by their US counterparts too. The most direct reference point is Google's YouTube. YouTube attracts more than one billion users each month, but according to news reports it still has not contributed meaningfully to Google's earnings. When the US streaming service provider Netflix expands into producing original content, it is similarly challenged by rising costs. Amazon has also been criticized by Wall Street for the rising costs of buying rights into HBO TV series and Disney films to build up its streaming video content business.

To increase their revenue income, the Chinese video streaming sites are shifting the free-content model towards the mixed “free-mium model”. On the one hand, the video sites offer basic streaming content for free to attract advertisement income; on the other hand, they have a premium service for paid users offering exclusive content such as the latest Hollywood blockbusters and hit reality shows. However, while content cost is rising steadily, the revenue side of the video hosting industry remains uncertain and challenging.

First of all, as the major players increase spending into professionally-generated content (PGC), the issue of piracy becomes critical. Online piracy has long been a serious issue for the global entertainment industry, and China is no exception. For instance, even though China is the world's largest internet music market by users, according to the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI) the digital music sales in China were at an estimated $82.6 million in 2013, which accounted for less than 1 percent of the $15 billion in global revenues made in 2013 by record companies (putting China at No. 21 globally). Part of the reason was that many small websites distributed unlicensed music downloads.

On the video side, before Tencent Video's exclusive online distribution deal with HBO in 2014, there was no authorized online distribution channel for HBO in China. But popular HBO shows such as Game of Thrones had already attracted a large number of fans, who posted their thoughts and comments on popular Chinese film review sites like Douban.com. This was because many shows were available on piracy video sites, and even on some major online video sites, users had posted unauthorized clips of HBO shows with Chinese subtitles (those posts were later removed).

The encouraging trend is that although copyright piracy still exists in China, the situation is definitely improving. In recent years, China's leading video sites have spent millions of dollars to buy licensed TV shows and movies. As a result they have proactively enforced their intellectual property rights to protect their investments. In 2013, several video platforms teamed up with the Motion Picture Association of the US to take legal action against Baidu and software company Kuaibo (QVOD) for providing access to unlicensed content. Both companies were fined by the National Copyright Administration of China an amount of RMB250,000 each (nearly $40,000), the highest penalty under administrative enforcement measures.

In addition, Kuaibo's peer-to-peer video sharing software also became the target of legal action. This software was the most convenient and popular software for individual viewers to exchange content, and it also enabled piracy vendors to distribute pirated movies and TV shows without paying expensive video bandwidth costs. In June 2014, the Industry and Commerce Supervision Administration in the city of Shenzhen issued a fine to Shenzhen QVOD Technology of more than $40 million.

Many people believe the industry has made significant progress in cleaning up piracy. Unlike a few years ago, most of the Western TV shows and movies on Chinese websites today are licensed. Although pirated content still exists, it is in fact difficult to find a pirated version of new Hollywood movies online. The crackdown on piracy gives the video sites more confidence to invest in more professional content, and it should also help the platforms to guide more users towards pay-per-view or subscription.

The second challenge for the video sites is to develop a stable user group, which is critical for both subscriber fees and advertising income. Under the current “free content + advertising revenue” model, all the sites are converging into similar content offerings, and in the case of hit variety shows, TV series or movies, the content from all video providers is the same. So if one streaming site updates the content too slowly or stops updating, the viewers can simply move to another site (and move back and forth among different sites), since the cost of switching between sites (essentially zero) is much lower than switching cable TV services.

This means that even with professionally-made serial content, it is difficult for any video site to develop a stable viewer base, due to the similar content available on multiple platforms. For user-generated content that is low in quality and lacks coherent themes, the video-hosting sites can only attract passing traffic. For merchants and brands, the commercial value of advertisements on the video sites remains to be fully proven; hence the growth of advertising revenue for the video streaming sites is far behind the rising costs of content acquisition. That in turn puts further pressure on the video streaming sites to spend more on acquiring unique quality content.

The third challenge is to develop paying customers. In the US, the popular method for watching online videos is already subscription-based streaming like Netflix, which involves paying a subscription and streaming as much as the user wants. Only a small percentage of downloads come from on-demand services like iTunes. In China, the pay-for-content habit needs to be nurtured by the video services sites as they expand.

Because of their advertisement revenue-centered model, major video streaming sites are filled with free content for Chinese users. Just like YouTube in the US, the Chinese sites have provided viewers the access – largely free – to nearly all the latest Chinese TV shows, movies, documentaries, professional chess games and so on. Through license agreements between these sites and American networks, even foreign TV shows are often available to Chinese viewers on the same day that they air in the US. Chinese users therefore have little motivation to pay for content online, unless the video-hosting sites provide unique content to get viewers hooked.

For example, in July 2015, iQIYI released its self-produced series The Lost Tomb, which was produced exclusively for online viewers and enjoyed enormous popularity in China. In order to watch the full series, a huge number of users downloaded the iQIYI app and purchased the subscription service. As a result, the company's mobile app became No. 1 in the free app popularity rankings and No. 2 among all the apps at the Apple App store in China.

According to the company's data, the number of user clicks on The Lost Tomb episodes surpassed 160 million within five minutes following the release of the series. Since the release, the episodes of The Lost Tomb have been viewed over 1 billion times. In addition, iQIYI was also encouraged by the fact that the hugely popular The Lost Tomb did not have a big budget like Hollywood blockbusters. It did not even use top-ranking Chinese actors; instead, most of the show's popularity was driven by the young “xiao-xian-rou” actors at lower costs. (See the “Little fresh meat” box.)

Thanks to the development of mobile payments and premium content, combined with the crackdown on unlicensed online content, the market has seen rapid growth in fee-paying subscribers since 2015. For example, with the help of the success of The Lost Tomb, iQIYI announced that the company's paid streaming subscribers had doubled since June to reach 10 million as of December 1, 2015. From iQIYI's perspective, it was hugely encouraging because it took more than four years to acquire the first 5 million paid subscribers, but it only took about five months to double that.

To put this in context though, iQIYI's executive conceded in related interviews that this premium subscriber figure was just “a small portion of our over 500 million users”. In other words, although the growth rate of paid subscribers is strong, the number of subscribing members remains small. According to the 2015 Report on Development of China's Internet Audio-Visual Media by the China Netcasting Services Association, advertising income still accounted for the majority of the sector's revenue (approximately 70%), whereas income from member subscription fees and other services accounted for approximately 30%.

Still, the trend is a cause for optimism for industry players. In relation to Tencent's 2015 White Paper on the Entertainment Industry, Tencent executives claimed that for the major video streaming sites, the fee income from their paid subscribers had grown far more rapidly than advertising income. And it was estimated that the fee income side would catch up and provide a similar share of revenue to the advertising income side within three to four years. Alibaba's upcoming TBO (Tmall Box Office) should be an interesting test case for this. Alibaba announced in mid-2015 that it would launch an online video streaming service in China, similar to the streaming service company Netflix and the pay-television network HBO in the US, which would likely be the first test of a subscription-only model in China. Content quality and user experience would probably have to be perfect to make this experiment a success.

In summary, China's video streaming websites are still struggling to prove the profitability of the “Content is King” model. As piracy is reduced and intellectual property (IP) rights become better protected, the viewer traffic flows will mostly be determined by high-quality, copyrighted content, which will force all players to invest aggressively in exclusive self-made or third-party video content. Therefore, the competition for premium content will continue and intensify, but the large market potential and rapid revenue growth offer hope that the companies will turn profitable in the long run.

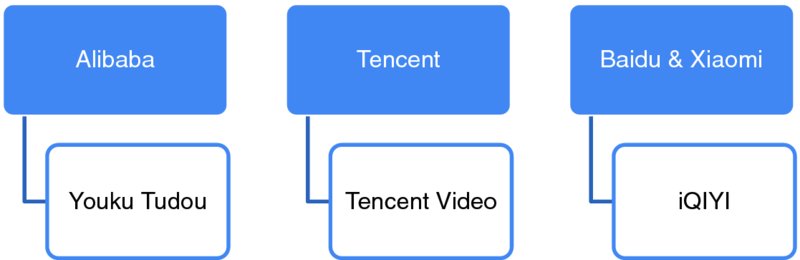

As such, like many other mobile internet businesses, the ultimate competition among the video streaming sites comes down to one thing: capital. To maintain and grow its market share, each site would need capital on three fronts: to buy the content that will win the biggest audiences and the most advertising; to attract experienced online advertising salespeople; and to expand their streaming bandwidth from an infrastructure standpoint. Again, the market sees each of the three internet giants – Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent – running or backing its own online video platform's costly expansion, as they view the mobile entertainment business as of strategic importance to their internet empires (see Figure 6.7).

Figure 6.7 BAT and Their Respective Video Streaming Sites

Multiple Screens, Multiple Revenue Models

Because the main theme of China's mobile internet centers on fun and enjoyment, internet firms view entertainment content as a similarly important channel to bring people to the online world as smartphones, mobile e-retailing, mobile search and social networks. Thus no internet firm can afford not to have a powerful entertainment platform centered on videos, both as a business line by itself for its revenue growth and as an online traffic hook to support the wider mobile commerce empire. This explains why all major players are investing aggressively in this sector even though it may take years before the video streaming business itself can turn profitable. At the same time, the internet giants are integrating the video streaming business with other parts of their respective internet empires in the search for more synergies.

The first aspect of integration is hardware. In the past, video streaming sites mostly used content to compete for users; now they are also investing in related smart devices as another way to engage viewers. In terms of entertainment hardware devices, the viewers’ “old normal” was TV sets before they migrated to the internet. During the earlier years of online entertainment, the main terminal for video viewing was personal computers. Now in the mobile internet era, viewers go to smartphones as their first choice of screen. However, from the point of view of the viewer, the small screen of smart devices is a very different experience from the earlier big screens.

Because viewers still appreciate a big screen for a premium viewing experience, many leading video platforms are working with manufacturers to launch set-top boxes, smart TVs and other devices. In an interesting cycle of development, smart TV sets, equipped with browsers and internet access, are likely to become the “new normal” of living room entertainment in the near future. So far, the customer still prefers set-top boxes to smart TVs for reasons including the latter's higher price, the availability of alternative devices and the complexity of connecting smart TVs to home networks and the internet, but smart TV is quickly catching up in terms of market share.

At the same time, software programmers are trying to apply the same kind of creativity to big TV screens as they have with the small smartphone screens. In the future, TVs are expected to run apps as diverse as those available on smartphones. One can imagine that new apps could turn a smart TV into a multifunction command center for other home activities like food delivery and video calls. Thus, in the living room re-modelled with “Internet +”, the big screen TV may remain as the main entertainment screen for households, and the smart TV and other mobile terminals may converge to collectively offer the same content and same entertainment value for users.

For instance, LeTV, originally a video streaming company that has been compared to Netflix, has expanded its hardware business into smart TV boxes, and then smart TVs, and more recently the smartphone markets. It boasts a content-centered platform, and its plan is to deliver premium content across the different devices within its unique software ecosystem. Similarly, Youku Tudou recently launched a new “Cloud Entertainment” business unit to develop hardware and services to make its content more accessible to users. The unit's first batch of hardware products consisted of a WiFi router, smart TV box and Android-system tablet.

This “content + device” convergence is further illustrated, in the opposite direction, by smartphone producer Xiaomi's $300 million investment in the online video platform iQIYI in late 2014. Apart from Xiaomi smartphones, Xiaomi also produces smart TVs (Mi TV) and set-top boxes (Mi Box), which may help iQIYI to grow its online video market share by reaching users of Xiaomi devices. As mentioned in earlier chapters, Xiaomi's vision is to develop a family of smart home devices that are seamlessly cross-linked under the Xiaomi “ecosystem”, for which the entertainment content of iQIYI may serve as a common linkage.

Another aspect of integration relates to e-commerce. This connection may potentially turn more video viewers into online shoppers, which is referred to as T2O, or “to online”. After its investment in Youku Tudou, Alibaba has started to place advertisements from Taobao and Tmall vendors within the online videos on the video-hosting sites. These videos are set up to have an advertisement cross-link that enables viewers to place orders for consumer goods that they see in the movies or TV shows.

T2O could be understood to mean “buying while viewing”, but it remains to be seen whether the majority of TV watchers are interested in making shopping decisions while enjoying entertainment content at the same time. To avoid disrupting the entertainment experience, a new feature gives the viewer the option, when they see attractive clothes or electronic devices, to either place orders immediately or select the item and put it into a “shopping cart”. In this way the viewer can handle the orders after finishing watching the program. The market, however, still needs more data on whether T2O truly creates a new, substantial source of e-commerce transac-tion flows.

The third integration is with other entertainment products on different screens. As introduced at the beginning of this chapter, internet literature works provide the upstream IP (intellectual property) rights for a variety of derivative content including publishing, gaming, animation, filming, as well as videos. The recent popular shows from iQIYI, LeTV and others, all adapted from popular online literature, were broadcast for both online viewers and TV watchers. In addition, some popular video shows like The Lost Tomb already had plans to produce related feature movies. In future, the video streaming sites may team up with local cable TV stations to offer subscription-based internet, cable and mobile entertainment content in a bundle as happens in the US.

All of the above represent a powerful trend where quality IP will be fashioned into various forms of content, which can then form seamless entertainment across multiple screens and formats, whether smartphones, PC computers, smart TVs, movie theaters and more. As shown by the emergence of Smart TV (and the boom in China's film box office to be discussed in the following chapter), consumer traffic flow between big screens (TV/movie theater) and small screens (smartphone/tablet) is not a one-way road to the mobile world, but a much more profound two-way flow.

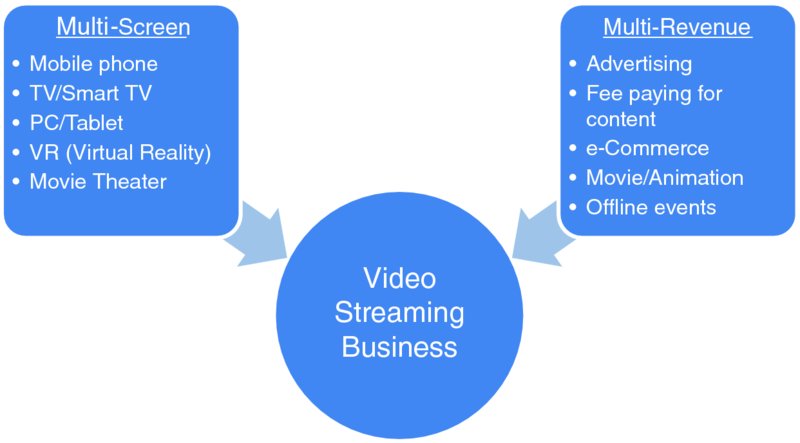

The line between online and offline entertainment is also blurred. For instance, the interaction of online videos, social networks and movie theater-goers is a prevailing O2O value proposition in the film industry. The internet firms have to capture and keep users’ continuous attention no matter what screen they are watching, online or offline – and convince them to pay. As they compete to offer the most compelling content package, terminal devices and integrated platform, the “multi-screen, multi-revenue” model is the new game in town (see Figure 6.8).

Figure 6.8 Multi-Screen, Multi-Revenue Model