Chapter 10

Launched in China

No one would have imagined that Amazon in China could become a customer of its local competitor, Alibaba. But since Amazon opened a flagship store on Alibaba's online marketplace Tmall in early 2015, it has become just that. Tmall offers virtual storefronts and payment portals to merchants, such as Amazon, who use its site in order to access end customers. In return, Amazon pays a commission on each sale on its Tmall outlet.

For Amazon, which is struggling to expand its independent e-commerce operation in China, setting up an online store on Tmall represents a major shift to its strategy. In the US, Amazon is synonymous with e-commerce, but since entering the Chinese market about a decade ago, the company has been fighting an uphill battle with local contenders, such as Alibaba and JD.com. Currently its domestic rivals Alibaba and JD.com control about 90% of the e-commerce market, which means that the world's largest internet retailer is a small player with less than 2% of the total market share.

From its online shop on Tmall, Amazon caters to Chinese consumers’ rising appetite for imported products. As one of the first major non-financial companies to set up operations in the Shanghai Free Trade Zone, Amazon promised customers competitive pricing, relatively fast shipping and a guarantee of the authenticity of the imported goods that it sold, all of which played to its strength as a true global brand. While foreign retailers are unable to compete on price vis-à-vis domestic suppliers, they may win over higher income bracket consumers who are keen to buy authentic branded goods that are simply not available domestically.

The Amazon China case demonstrates that in China's fast growing but highly competitive e-commerce space, it is critical for even highly successful overseas players leveraging their global resources to create a localized strategy. Amazon is still far from posing a serious challenge to Alibaba or JD.com, but its new move helps it to provide a differentiating service to Chinese consumers. As will be illustrated further in this chapter, Uber and other US internet firms are entering the Chinese market employing various localized strategies and tactics, including separate Chinese offices, local employees, local investors and local partners.

The business dealings between Amazon and Alibaba also illustrate that the Chinese and foreign internet firms are increasingly interconnected. The Chinese market not only has an unrivalled internet user group, but is also the largest mobile-first and mobile-only market in the world. As a result, new mobile applications often achieve scale more quickly in China than elsewhere. This chapter will also examine the innovation ecosystem in China, which is quickly becoming a source of unique features, products or business models that can be adapted by foreign companies. The Chinese market is poised to be the trend-setter in the near future, rather than the trend-follower, particularly in next-generation mobile device and application innovation.

Uber: Localization in the Chinese Market

Uber, the San Francisco-based car-sharing app company, was a latecomer to the ride-hailing service market in China. Uber began tests in China in late 2013 in the southern cities of Guangzhou and Shenzhen, offering a service in which customers could hail rides from licensed limousine companies. Its official full-scale expansion in China did not occur until December 2014, when Uber sold an equity stake to China's search engine giant Baidu and integrated its service with Baidu's map application and payment system.

However, Uber has been an undeniable hit in China, and Uber's explosive growth in China may be the best performance by a US tech company in years. Uber CEO Travis Kalanick disclosed at a September 2015 Beijing event that Uber's Chinese unit operated in almost 20 cities. Five of Uber's top ten cities by ride volume were in China, and Uber China counted 1 million rides a day in the country. Furthermore, it planned to enter 100 more Chinese cities over the next year, doubling the company's own expansion goal (of 50 cities) that was set just three months ago.

According to the 2016 Chinese New Year Cross-border Travel Report released by Uber China, Chinese Uber users traveled to 319 cities around the globe during the Spring Festival holiday week in February 2016, more than twice the figure reported in 2015. China's financial hub, Shanghai, reported the largest number of Uber users choosing to travel overseas, followed by Beijing, the southern metropolises of Guangzhou and Shenzhen, and then East China's Hangzhou and Southwest China's Chengdu. (It is worth noting that Chengdu replaced New York to become Uber's most successful city globally in terms of daily ride volumes in October 2015.)

As background, as is the case in many cities around the world, the demand for cross-town transportation is at the heart of an urban lifestyle in modern China. Although more individuals have begun to own their own cars, the demand for taxi service is increasing even more quickly, as the population in many cities has exploded due to relentlessly fast-paced urbanization. Local governments in Chinese cities limit the base fare that taxis can charge customers. In places where the government-mandated taxi fares have been kept low or even reduced, the taxi drivers strike from time to time, making hailing a taxi next to impossible.

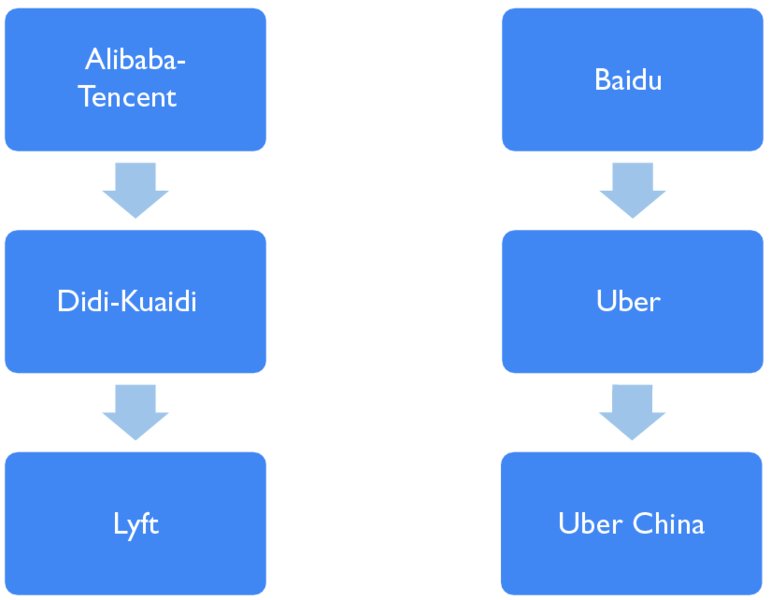

Partially in response to the demographic trends and partially in response to the dysfunctional nature of the market, car-hire apps emerged in 2012 to allow smartphone users to book and pay for taxi rides or limousine services using mobile apps. Their emergence has changed the way that the Chinese travel around their cities. In this area, Uber's main competitor is Didi Kuaidi, a combined entity resulting from the merger of two specialist start-ups in taxi-hailing that were backed by two of China's biggest internet companies Alibaba and Tencent, respectively. Before their merger, Alibaba invested in Kuaidi (translatable to “finding a taxi swiftly”) and Tencent invested in Didi (which denotes the “honk honk” of a taxi).

After their launch in 2012, the Kuaidi and Didi apps caught on instantly with China's urban residents. The already large, expanding and congested cities, with their inadequate public transit networks, and the relatively large fleets of inexpensive taxis make the Chinese market perfect for taxi-hailing mobile services. But trying to get taxi drivers in China to use taxi-hailing applications was not easy. Early on, both companies had to find creative ways to attract, train and convince taxi drivers who were not tech savvy nor wanted to be. They competed head-to-head on the streets to promote their respective apps and corresponding mobile payment systems (Alibaba's Alipay and Tencent's WeChat Pay).

Both Didi and Kuaidi spent huge amounts of cash on subsidies to incentivize passengers and drivers to try out their services. In addition, they set up customer support centers near the spots where taxi drivers gather to have a cigarette or tea during shift changes. Some app managers were based in those centers to facilitate registration and to teach hundreds of taxi drivers how to use the app. At one point, the service centers offered free beer to taxi drivers to register themselves and bring along more of their colleagues to sign up (after completing their shift of course!). Then the drivers would be divided into groups on the app, with the idea being that the drivers could exchange information on traffic and road conditions within the group, which might also encourage the drivers to stay logged onto the app even in the absence of hailing customers.

After a price war reportedly involving more than $300 million in total rebates to taxi drivers and customers, the two companies did entice many taxi drivers and, as a result, permitted Didi and Kuaidi to penetrate the market in a really meaningful way. (In fact, almost all taxi drivers in big cities now have multiple smartphones and tablets installed in their taxis each devoted to servicing specific apps.) And, of course, because it became convenient to have access to at least one app, a large portion of urban residents installed e-payment apps on their smartphones and linked their bank accounts to them, so that they could complete mobile payments directly at the conclusion of their taxi rides.

Unfortunately (or perhaps obviously) the cumulative cost of the subsidies proved to be too much for the internet firms. In February 2015, these two largest taxi-hailing apps decided to enter into a $6 billion merger that effectively put an end to the price war. (Possibly as a symbol of “marriage” and “good will”, the merger news was announced by the founders on Valentine's Day.) At the time of the merger, Didi Kuaidi reportedly employed 4,000 people, compared to the 200 who were working for Uber in China. The combined company had a near monopoly on mobile hailing of traditional taxis, and it also controlled more than 80% of China's private car-hailing market, according to the estimates of research firms.

Didi Kuaidi's taxi-hailing model is different from that of Uber. The internet companies make no money from taxi rides, and the hailing app is simply a tool to acquire customers for other ride-hailing services. Over time, of course, Didi Kuaidi has moved to monetize its giant customer base with what it calls a “freemium” model, in which Didi Kuaidi broadens its offerings to include premium car services and carpooling, both of which have been the main business lines of Uber globally. For example, in the summer of 2014, Kuaidi launched a luxury limo service in 20 cities that competed directly with Uber's high-end black cars.

The key to Uber's rapid growth in China is its commitment to localize its services to suit the Chinese market. In CEO Travis Kalanick's own words from his interview with Chinese media Caixin: “[We] have to go above and beyond in becoming truly Chinese.” Uber understands that the complex and swiftly changing business environment in China is fundamentally different from the rest of the world, and has taken several important steps to adapt its business model to these unique conditions (urbanization, growth, swift demographic change, etc.).

First, Uber set up Uber (China), an independent entity with a separate management structure and separate headquarters. In fact, Uber China was the only instance in which Uber set up a separate company in a foreign company. And it demonstrates Uber's determination to make its Chinese operation embedded in the Chinese market. To that end, Uber China has also engaged with strategic investors that could help guide them to become “more Chinese”. This has included building local management teams, interacting more closely with regulators and the government, and campaigning extensively to acquire more customers and drivers. According to the company's disclosure in early 2016, Hainan Airline Group, Guangzhou Automobile Group, Citic Securities and the insurers China Taiping and China Life are among “a long list of Chinese firms with investment in Uber”.

Among all the Chinese institutional investors, Uber's relationship with Baidu is probably the most critical. For Uber, at least three things about its business in the Chinese market are different from its business in the rest of the world, both from a technology as well as a product perspective. One is about the mobile payment systems in the retail market, which is dominated by its primary competitor's two major investors (Alibaba and Tencent). Another is about maps and location services (because Google Maps still does not work in China at the present moment). The third factor is the reliance on and interconnectivity with social networks, as social apps in China are more thoroughly embedded and often work differently from those available in English-speaking markets.

As summarized by Figure 10.1, the investment relationship with Baidu provides Uber with all three indispensable components – the leading map service in China, a payment system independent from Alibaba's Alipay and Tencent's WeChat Payment, and social network based marketing on the Baidu platform, which is an important alternative to the WeChat social network. (In fact, Uber's public account was blocked by Tencent's WeChat social network in 2015.)

Figure 10.1 Critical Baidu Support for Uber's China Expansion

Uber is acutely aware of the fact that the majority of Chinese consumers are extremely sensitive to price. They aspire to the same services and goods they observe in the developed markets, but they always look out for free stuff or bargains as their incomes are comparably low. As a latecomer, Uber has offered huge subsidies to win over market share, sometimes doling out bonuses that are up to three times the amount of an average ride fare. In 2015, Uber China reportedly invested $1 billion in order to expand its market reach (while Uber was increasingly driving for profitability in the US market).

Interestingly, Uber's discount and subsidy strategy looks very similar to Alibaba's successful attempt to challenge the then-dominant eBay in China a decade ago. Taobao, Alibaba's main C2C (consumer to consumer) e-commerce marketplace, opened in 2003 without charging users fees. For a few years, it maintained a no fee model, while eBay in China continued to charge sellers and so lost market share steadily. Alibaba did not start charging transactional fees until it fully dominated the market. As Uber (China) raised nearly $2 billion in the second half of 2015 (with the latest round of fund raising reportedly boosting its valuation to more than $8 billion), the company is expected to put more subsidies into play in 2016 to continue its aggressive expansion.

Unlike many Western tech firms that mostly rely on expatriate managers, Uber hired local management and empowered them to run city operations. That move is critical for solving local issues in the complex and very challenging car-hiring business environment. For example, because Uber offers a large amount of cash as bonuses to Chinese drivers to get them on board, some drivers game the system by employing specialized software to cheat in reporting rides or their duration.

The local managers are quick to identify and deal with local scams that are detrimental to Uber's business. (See the “Patients, Nurses and Safe Shots” box.) Had Uber simply stuck to the tried and tested formula of hiring expat managers, it is likely that its ability to respond to such local challenges would have been slower and less effectual.

The local management team is also critical to Uber's China operation because the overall regulatory regime remains in flux. Many car-hire app users have applauded the mobile app businesses for the convenience it offers in being able to find a car (whether a taxi or private car) that has a friendlier driver than in a standard taxi. But as in many places where Uber operates, there is also rivalry between its car-hire drivers and the established taxi drivers who are also plentiful in most Chinese cities. The profits made by taxi drivers have been squeezed by the services provided by unlicensed, private drivers, and they complained about the unlicensed nature of the business, attacking it by raising safety concerns.

Generally speaking, Uber and other car-hire app companies that link passengers to private drivers still operate in a legal gray area in the country, as policymakers mull over ways to regulate the industry. The central government has not yet developed nationwide regulations for car-hire apps, but some local municipal authorities have developed regulations that prohibit unauthorized private car owners from using the apps to pick up passengers. Uber's local managers are effective in communicating with the municipal governments. And they have, on occasion, managed to find government officials who are willing to support this innovative technology and service in their cities.

Uber China has also done well in understanding how to play into local users’ special interests and preferences in order to differentiate itself from the competition. For example, in the summer of 2015 Uber China launched a promotion that gave the users the chance to meet eligible bachelors through its app on the eve of Qixi Festival. (The Qixi day is the seventh day of the seventh month in the lunar calendar. In a fairy tale, a celestial weaver and a cowherd on earth fell in love but were separated by heaven's rules. They were only allowed to meet on that one day each year.) In the cities where Uber operated, special buses picked up users who booked places in order to mingle with other singles.

The campaign helped to provide an experience for Chinese Uber users that was both fun and local. On Chinese social media, Uber was lauded as playing matchmaker on the nation's equivalent of Valentine's Day. There were even jokes about Uber having accumulated a convenient, self-selecting pool of potential husbands for single women. In short, the local management teams of Uber China understand what Chinese people need, and they were empowered to acquire users by adapting to local preferences, instead of attempting to impose marketing and publicity techniques simply because they worked in other markets.

Of course, the competition between Uber, Didi Kuaidi and other homegrown car-hiring app companies is far from over, with Uber set to expand its offerings and footprint, and the local players expanding to premium services. Whereas Uber offers marquee black car service in major cities, it has also launched less expensive services such as a ride-sharing service to allow private individuals to pick up passengers. It tries to gain mass appeal in China by offering a higher standard of rides for a modest premium. Conversely, the challenge for the Chinese companies will be to move up-market with new paid services that compete with Uber's successful premium service.

Inevitably, Uber and its local rivals in China are on a collision course in the world's largest car-hiring market. In an interesting parallel to Uber's China's expansion, Alibaba, in 2014, made a sizable investment in Lyft, the main competitor to Uber in the US. In 2015, Alibaba-backed Didi Kuaidi also invested in Lyft, leading to a complex web of partnership and competition among the internet giants in China and Silicon Valley (see Figure 10.2). In fact, it may be a harbinger of more direct competition between the Chinese and US internet firms in their respective home territories. Their fierce rivalry may result in lower prices for customers, creative business models and possibly further revolution in technology.

To add a new twist to their intertwined competition in both the Chinese and US markets, Uber and Didi entered into merger discussions regarding their China operations in August 2016. Such a merger would potentially create a cross-holding alliance. In the proposed transaction, Uber would sell its China operations to Didi in return for a 5.89% stake in the combined company along with “preferred equity interest”, which would be equal to a 17.7% stake. Uber China's investors, including Baidu Inc, would receive a 2.3% stake in the merged entity. Didi founder Cheng Wei and Uber Chief Executive Officer Travis Kalanick would join each other's boards.

This proposed merger was viewed by the market as a form of truce, bringing to an end a costly price war between the two companies who were vying for leadership in China's fast-growing ride-hailing market. By selling its China operations to its fierce rival Didi, Uber would be free to focus on other markets and possibly an initial public offering of the Uber group. However, China's Ministry of Commerce, the antitrust regulator, found that the two announced their agreement to merge without filing an application with the Ministry in advance, and, thus, without obtaining formal clearance.

According to the Ministry of Commerce, based on the antitrust regulations in China, “business operators need to file an application on their merger deal if their combined revenues reach a certain amount.” In September, the Ministry announced at a news conference that it was investigating whether the merger between Didi and Uber's China unit could lead to a potential monopoly. In other words, the vast scale of Uber's operations in China, along with its rapid expansion in this market, may become an obstacle to its planned merger with the major local player.

Figure 10.2 Interconnected China and US Internet Firms in Ride-Hailing

Uber's success in obtaining substantial market share in China, when contrasted with other non-domestic technology companies, can be viewed as unique. However, what's even more interesting from the perspective of this narrative is the fact that Uber's service has taken off in China much faster than it did in the US. For example, Uber's top three most popular cities worldwide purely in terms of ride volumes – Guangzhou, Hangzhou and Chengdu — are all in China. Of course, the enormous scale of the Chinese market is the primary reason. An equally important factor is the high concentration of city residents following central government's urbanization push. There are about 200 cities in China with more than a million people, which are perfect places to develop “shared economy” business models.

Chinese customers are ready adopters of social network technologies. They socialize online and actively re-distribute information on new products or new services to their contacts. The mobile internet and smartphones have created a new social coordinating mechanism, and what the market sees is a seemingly endless potential to put goods, labor, and in the case of Uber, cars that are less than fully utilized, to productive use. The implication is profound: new mobile applications probably can receive market feedback and achieve meaningful scale more quickly in China than elsewhere, because new technology based on “human infrastructure” tends to spread faster in China. In fact, Uber has found that even when it comes to the initial number of customers in a region – the first 1 million users in a city – its growth in China has been much faster than what it has seen elsewhere.

That's probably why Uber CEO Travis Kalanick calls China one of “the largest untapped opportunities for Uber, potentially larger than the US”. For foreign tech companies, the Chinese market is not only important for its enormous market size and the fast pace of technology adoption, but also valuable because of the unique innovation arising from it. As the subsequent sections will illustrate, the emerging innovation ecosystem in China is creating a remarkable wave of innovation that challenges the long-held perception of “Made in China” being simply synonymous with cheap imitation. Going forward, the Chinese market may well be a source of innovation for international companies.

A New Innovation Ecosystem

Few people know of the Zhongguancun Science Park in Beijing, which is one of the major innovation hubs for China's tech industry, and probably even fewer would compare it to Silicon Valley in the US. However, it is the home of established Chinese internet players including Lenovo and Baidu, and it also houses the Chinese headquarters and research center for world-renowned technology corporations such as Google, Microsoft, Intel and Oracle.

Located in the capital city of Beijing, Zhongguancun is filled with angel investors, hedge funds and venture capital firms that have helped fuel the breakneck growth in online and technology based businesses. Zhongguancun is also close to a group of top Chinese universities, national academies and corporate research centers. According to the data from the Ministry of Science and Technology, the Zhongguancun district gave birth to 49 start-ups on a daily (!) basis in 2014. The main section of the Zhongguancun Science Park, the nearly 200-meter-long Inno Way (or “the Innovation Street”), had attracted 2,000 angel investors and investment organizations as well as 4,000 entrepreneurial teams in a year since its June 2014 opening.

The Zhongguancun Science Park, together with numerous high-tech development zones that spread across the country, constitutes a national infrastructure for innovation that is strongly promoted by the central government as well as the local provinces and cities. In his public speeches, President Xi Jinping emphasized that innovation, economic restructuring and consumption should be among the top priorities of China's next stage growth (the 13th Five Year Plan for 2016–2020). Premier Li Keqiang suggested at the 2015 central government work report that, in addition to the existing RMB40 billion (nearly $7 billion) government fund earmarked for China's emerging industries, further funding would be made available for promoting business development and innovation.

The government initiatives include building up the innovation clusters, where the administration system is more user-friendly for businesses to get started (for example, faster corporate registration). Local governments also launch venture funds at provincial and city levels, whose funding and subsidies help early-stage entrepreneurs feel more comfortable with taking a little bit more risk. In dozens of cities like Beijing and Shanghai, university graduates and young professionals are frequently rewarded with preferential tax treatment for their start-up endeavors.

Also, incubator facilities are established to provide entrepreneurs with inexpensive or even free office facilities, assistance with business services, and common spaces that connect the budding startups with potential investors. They also serve as community centers, where entrepreneurial minds can bounce ideas off each other and start-ups’ owners meet angel investors to present projects. In addition, they are also education centers. Various lectures on entrepreneurship and capital markets are held daily, where seasoned professionals share their experiences with the “wannabes”.

There are more than 20 incubator facilities (also known as service centers) on the “Innovation Street” at the Zhongguancun Science Park. For example, established in 2011, Garage Cafe was the first service center at the district where entrepreneurs could work on their projects for a whole day at the cost of one cup of coffee. Today the 3W Café is by far the most famous among all the coffee shops, because Premier Li had coffee there with start-up owners and entrepreneurs in May 2015, tangibly demonstrating the government's support for entrepreneurship and innovation. (See the “Premier Li's Cappuccino” box.)

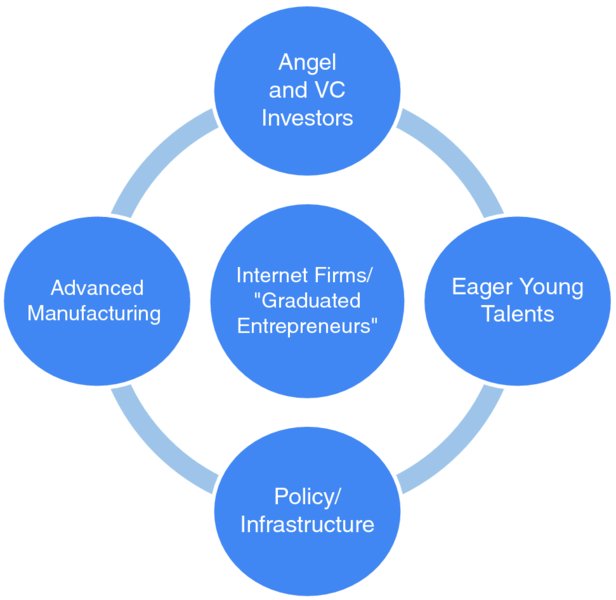

In 2015, according to data from the Ministry of Science and Technology, China had more than 1,600 technology incubator facilities. With government endorsement in the background, a dynamic ecosystem of entrepreneurs and start-ups is organically being built up (see Figure 10.3). The network of established internet firms and their seasoned entrepreneurs, endless eager talents, abundant angel investors and venture capital, and a sophisticated manufacturing system are collectively making China one of the most interesting centers of innovation in the world.

Figure 10.3 China's Innovation Ecosystem

For an illustration, one need look no further than the last decade's track record of Chinese “unicorns”, the early stage tech firms that are valued at $1 billion following an initial public offering (IPO), sale or publicly announced private funding rounds. According to data compiled by Atomico, the London-based venture capital group led by Skype co-founder Niklas Zennstrom, among the 134 tech start-ups that reached the billion-dollar mark during the 10 years of 2004–2014, the number of “unicorns” from China (26) exceeded those from Europe (21), and was only behind the innovation superpower of the US (with 79, of which 52 came from Silicon Valley). (There were none from Africa, Latin America, or the Middle East.)

What is remarkable is that, unlike in the past this new innovation ecosystem cultivates cutting edge ideas for the global technology and media industries. The first generation of Chinese tech companies were mostly copycat versions of Western sites. However, in the new digital economy, the second generation start-ups are about Chinese users’ booming online consumption and the rapid adoption of mobile applications. They are creating a remarkable wave of innovation in business models and product features that challenge long held perceptions and is very likely going to represent a successful source of exports to the rest of the world.

The core of this ecosystem is a network of “graduated entrepreneurs” from established tech firms at home and abroad. Many of them had previous successful careers at the three leading internet firms (Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent). Their BAT resume provides them with immediate credibility in the market. Their alumni network not only provides industry talent to partner with or recruit, but also supplies a pool of seed investors. In some cases, the BAT companies themselves may become a significant strategic investor.

More start-up founders are emerging from other origins as other companies besides BAT have reached significant business scale and multi-billion valuations (Xiaomi being only one example). Equally important, some founders are former Chinese employees of global technology giants such as Microsoft, Hewlett-Packard and Yahoo (either in the US or in their Chinese operations). The trend cuts across the pay grades of the major companies as the most innovative, irrespective of seniority, can replicate the success of the companies they work for, but now as owners or founders rather than as employees.

Either as a senior executive who is financially secure enough to take a major career risk, or as a newly-minted young employee who feels that she does not have much to lose, the aspiration to create a Xiaomi or Didi Kuaidi is everywhere. Hundreds of start-ups have been created in the past three years by former employees of Alibaba and other major internet firms. As previously described, two former employees of Alibaba's Taobao marketplace founded Mogujie, a social shopping website specializing in women's fashion, and it has already become a unicorn itself (with a valuation exceeding $1 billion). This development resembles the multiplying effect seen in the Silicon Valley ecosystem in the last few decades, where the generations of innovators from Intel, Netscape, Google and Paypal have created wave after wave of start-ups.

Along with the growing number of “graduated entrepre-neurs”, there seems to be an endless supply of young and eager talent. More than half a million engineering students a year graduate from Chinese universities. At the business schools, more MBA candidates than ever are taking entrepreneurship courses with ambitious plans of launching start-ups. (Years ago, investment banking and management consulting jobs were the top two career tracks.) And an entire generation of young Chinese students are returning to China for mobile internet opportunities following their undergraduate studies in the US and Europe.

At the 3W Café and other entrepreneurship-themed community meeting places, the “graduated entrepreneurs” are mentors and angel investors to the younger start-ups. Driven by those former internet firm employees, there is an increasingly active angel investor community which is keen to invest in the next big wave of information technology ventures. In recent years, both the amount of angel capital and the number of projects that could be invested in have increased multiple times. According to Zero2IPO Research, during the first half of 2015, there was $743 million angel capital invested in 809 projects, with the average investment per deal nearing $1 million per transaction.

Another important factor in this booming ecosystem is an unprecedentedly large flow of venture capital (VC) – from both foreign and domestic funds – into start-up projects. As would have been expected, businesses that focused on mobile consumers have dominated VC capital-raising in recent years. With the emergence of angel investors, who tend to invest in even earlier phases than the venture capitalists, the VC firms are also moving their involvement forward. (In extreme cases, “investors are in line even before the business is functioning in any meaningful way”.)

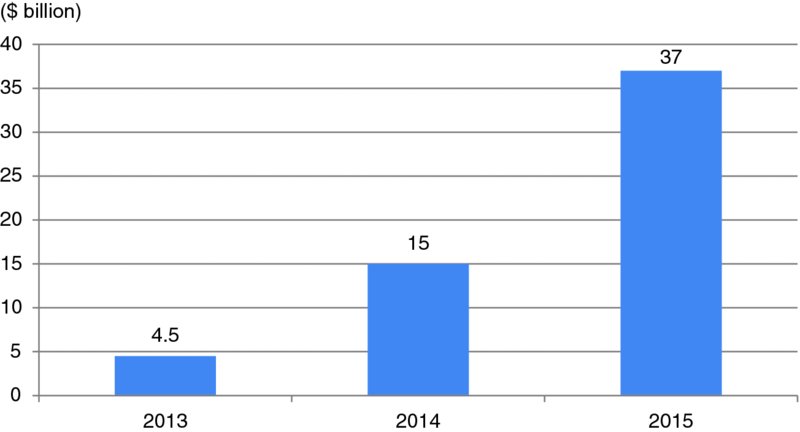

In 2015, according to data from consultancy Preqin, in 2015 venture capitalists invested a record $37 billion in Chinese start-ups, more than double the previous year's number. The doubling of venture deals last year came after a tripling in deal value the year before, demonstrating the immense appetite of the VC industry for Chinese innovation (see Figure 10.4). Although not necessarily counted as venture capital, the investment arms of established internet firms (such as BAT and Xiaomi) are also aggressively chasing investment opportunities. Because they are disruptors themselves, they are constantly on the lookout for the next big thing – some new development that can fundamentally change the ecosystem or even the landscape in which they operate. As a result they diligently make investments into new ideas across all sectors.

Figure 10.4 Total VC Investments in China (2013–2015)

(Data Source: Preqin)

The pace of VC deals slowed in the fourth quarter of 2015 because there were concerns that too many start-ups had been set up in certain sectors in China, leading to costly price wars among them to compete for customers. For example, in the O2O (online-to-offline) service market, many apps often started in a single niche (such as flower delivery and wedding services) and used venture capital to fund subsidies to attract customers and suppliers, rather than focusing on the development of innovative solutions or the scaling of their current platforms. As a result of this, some venture firms have started holding back on new investments, particularly as concerns are rising that the market was saturated with start-ups trying to solve identical problems. Too much competition between these made the risk of business failure very high indeed.

However, Meituan-Dianping (the leading O2O company for restaurant booking and movie ticketing analyzed in Chapter 5) raised $3.3 billion at its latest private fundraising round in early 2016, shrugging off such worries, at least for the present moment. The investors in Meituan-Dianping (valued at more than $18 billion at this fundraising round) included venture capital firm DST Global and Singapore Sovereign Wealth Fund Temasek. The $3.3 billion Meituan-Dianping fundraiser topped an earlier $3 billion round raised by the ride-hailing company Didi Kuaidi to become the single largest funding round on record for a venture capital backed start-up.

In fact, the fundraising by Meituan-Dianping in the January 2016 round sets all records globally for a venture capital fundraising round. And, overall, China is narrowing the gap with the US, the global center of modern venture capital. (According to Preqin data, the value of US deals in 2015 was $68 billion, up from $56 billion the previous year, which represents a smaller increment than that of comparables for China.) The country is, in effect, emerging as a legitimate and serious challenger to the US for leadership of the technology industry.

Also notably, moving beyond “Made in China” does not mean that the sophisticated manufacturing infrastructure is of no use; instead, it is an indispensable part of this ecosystem and a distinctive competitive advantage over other innovation hubs worldwide. China's economy modernization started with manufacturing connected to the import-export businesses. After decades of continuous development, it has a seamless web of sourcing, manufacturing and logistics services that is second to none. The electronic manufacturing sector is by far the most advanced globally. For example, the southern city of Shenzen is arguably the best place for hardware start-ups. Once a small fishing village next to the powerhouse of Hong Kong, following three decades of development Shenzhen is now home to domestic tech giants such as Huawei and ZTE, and it has become an electronics manufacturing center for the global tech industry.

With easy access to parts and manufacturing know-how, this smart hardware hub provides young companies with an edge over foreign competitors in terms of production timelines. Also, having the supply chain in such close proximity means that early stage inventors can easily tweak their pilot products at factories, giving them more opportunities to calibrate the finished product. In fact, China's massive electronics supply chain, still robust in the aftermath of the “Made in China” era and still becoming increasingly sophisticated, is invaluable in the new convergence between hardware and software.

In summary, the new dynamic ecosystem in China is creating more tech start-ups that cannot simply be described as the Chinese version of US or other Western firms. The new generation of companies are more innovative in terms of products and technologies specifically designed for local market needs, more willing to accept outside investors, and have a more global outlook from their inception. In particular, many are using the mobile internet to challenge inefficient domestic incumbents.

In fact, it is quite possible that in the near future China will have more billion-dollar start-ups than the US, although given Silicon Valley's lead, the US is likely to continue to have more firms in the highest bracket of valuation. China's top ten highest valued start-ups (see Table 10.1) are almost all related to mobile commerce. Their high valuation not only reflects their dominance in the world's largest mobile commerce market, but also factors in the investors’ optimism in the special business models or product features that they are pioneering.

Table 10.1 China's top ten highest valued start-ups (as of January 2016)

| Company name | Valuation (US $ bn) | Latest funding (valuation date) | Business description | |

| 1 | Xiaomi | 45 | December 2014 | Leading manufacturer of smartphones and smart devices |

| 2 | Ant Financial | 45 | July 2015 | Internet finance company covering mobile payment, cash management and wealth management |

| 3 | Meituan/ Dianping | 18 | January 2016 | China's Groupon and Yelp, covering both group buying and consumer reviews |

| 4 | Didi Kuaidi | 15 | July 2015 | Dominant taxi-hailing app, Uber's biggest rival in China |

| 5 | Lufax | 9.6 | March 2015 | Internet finance, one of the largest peer-to-peer (P2P) online lenders |

| 6 | DJI Innovations | 8.0 | May 2015 | The world's largest consumer drone maker by revenue |

| 7 | Zhong An Online | 8.0 | June 2015 | China's first online-only insurer |

| 8 | Meizu | 6.0 | February 2015 | Smartphone and internet service company backed by Alibaba |

| 9 | LeTV mobile | 5.5 | November 2015 | Smartphone unit of LeTV, the internet and video conglomerate |

| 10 | Ele.me | 3.0 | August 2015 | Online food delivery service for universities, offices and others |

(Data Sources: Disclosures from fund-raising rounds; Approximate valuations)

Cross-Pollinating Innovation

Today Chinese companies are moving to the forefront of global technology innovation, particularly when it comes to hardware. For example, when President Xi Jinping visited Tajikistan during the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) Summit in September 2014, the smartphone from China's domestic brand ZTE was on his list of national gifts.

The specific ZTE model used for national gifts was reputed as one of the world's most secure handsets (perhaps thanks to ZTE's recruitment of Blackberry's research team after the Canadian company's recent financial distress related restructuring). Historically, China used traditional artisanal products such as silk, porcelain and painting as national gifts in the diplomatic context. Using domestically produced smartphones as “national gifts” is intended as a demonstration of the progress China has made in the technology sector, and it also demonstrates China's determination to transform itself from the “world's factory” for low-tech manufacturing into a global technology exporter.

The Chinese companies’ innovative power was demonstrated at the most recent 2016 Consumer Electronics Show (CES) in Las Vegas, which had a decidedly Chinese flavor this year. Of the more than 3,600 exhibitors in the Vegas show, about one-third came from China, up from about one-fourth in the previous year. China's entrepreneurs were bold in releasing new products to showcase their ingenuity, debuting innovative robots, drones, electric cars, virtual reality headsets, elegant looking Android smartwatches and TV sets with the latest true-to-life imaging technology.

Whereas the innovations from Chinese start-ups wowed the CES crowds, China's giant tech companies were also busy launching their new products and research strategies.

Lenovo made headlines at the 2016 CES with news that it aimed to make a $500 Android device with built-in Google spatial perception technology. It seemed that Lenovo would be the first to bring that particular technology (Google's Project Tango) to consumer smartphones later this year.

Meanwhile, the internet and video conglomerate LeTV supplied “an internet brain” to Aston Martin, the trendy British luxury sports car brand that is associated with the legendary secret agent James Bond. LeTV and Aston Martin showcased the first model of their collaboration – an Aston Martin Rapide S that incorporated the LeTV Internet of the Vehicle (IOV) system. The car featured a new concept for the center console and instrument panel, equipped with an HD touch screen. It also incorporated LeTV's latest speech recognition technology, which enabled the car to respond to the driver's orders such as lowering the windows.

Internet-connected and electric cars are considered to be the next key terminal for mobile internet after the smartphones. Related to terms like “intelligent highway”, “connected cars” is an umbrella term for the idea of linking increasingly intelligent cars to the mobile internet through a stronger form of Wi-Fi or more robust wireless telecommunications networks. In 2015, China issued a new policy to encourage internet companies to develop electric vehicles. In the past, the biggest hurdle for non-automakers entering the industry had been a stipulation that companies had to possess vehicle production capacity. By allowing companies outside the traditional manufacturing sector to develop electric vehicles, the new policy essentially created a new manufacturing model for the auto industry. In effect non-manufacturers, primarily innovative digital companies, could totally outsource their car production.

China's three biggest internet companies Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent (BAT) are becoming involved in the connected car business. In 2015, in one of the first steps in this direction, Baidu launched a cross-platform (smartphone and in-car system) solution for connected cars called CarLife, based on its digital mapping service, Baidu Maps. CarLife provided users with services including route planning, location inquiries, distance estimations and navigation advice for users to avoid traffic. The company also tested a self-driving car model in 2015 and demonstrated the technology to Chinese President Xi Jinping at an industry expo in Wuzhen, Zhejiang province.

Tencent launched the first smart car hardware, “lubao box” in June 2014, which connected vehicles to Tencent's cloud computing services. The “lubao box” focused on the self-examination of a car's condition (such as fuel consumption). Alibaba, on the other hand, worked to improve the entertainment system in cars by leveraging its extensive investments in the media industry. With its strength in hardware devices and smartphone batteries, ZTE chose wireless charging for vehicles as a point of entry into this new field. For years China has promoted the use of electric vehicles to cut pollution, but the lack of charging stations for any type of alternative energy vehicles has always caused a bottleneck. By making charging wireless, ZTE could solve the biggest headache for both owners and for regulators, and the feedback it received on its venture has been very positive.

Of course, these improvements to cars have thus far primarily involved moving mobile apps from smartphones to vehicles. At this early stage, “connected cars” is more about cars with internet connections rather than cars that are connected with each other and with their drivers and other people. The internet firms may be years away from meaningfully changing the value chain of the auto industry. But their investment in connected cars is set to accelerate in the coming years, and the more revolutionary interaction of car, people and road may come sooner than we expect.

The innovation boom among Chinese companies is partly stimulated by the new innovation ecosystem and partly driven by the need to survive in the competitive global market. The major companies have gradually outgrown the low margin “OEM” or “components manufacturer” image, distancing themselves from competition for rock bottom prices. Instead, they move towards higher price categories in the global market, while upgrading their brands to change the conventional perception that Chinese products mean low price, low quality and poor service.

In particular, the mobile internet market is extremely competitive, and therefore finding new ways of meeting the customers’ requirements is critical to commercial success. The Chinese companies are forced to innovate as their profits are squeezed both in domestic and overseas markets. They appreciate the vital importance of innovation and branding in allowing companies to achieve premium pricing, high gross margin and bottom line profitability, which, in turn, can provide the cash flow for further research and development. For that, there is no better example than Apple's dominance in the profit share of the global smartphone market.

Here the case of Apple's iPhone is examined for the last time in this book, and the discussion focuses on the bottom line profitability of Chinese brands and Apple. According to the research firm Canaccord's early 2015 report, Apple (92%) and Samsung (15%) have captured all the profits of the global smartphone industry (see Table 10.2). They collectively accounted for more than 100% of industry profits because other makers either broke even or lost money. The research firm's data did not include privately held companies such as China's Xiaomi and India's Micromax Informatics, but Canaccord believed that the profits for those companies, if any, were not significant enough to change the industry-wide profit allocation numbers.

Table 10.2 Profit distribution of the global smartphone industry

| Year | Lion's Share of Profits |

| Before iPhone (2007) | Nokia (67%) |

| 2010 | Nokia, Apple, Blackberry (similar share) |

| 2012 | Apple, Samsung (50%–50% split) |

| 2014 | Apple (92%), Samsung (15%) |

(Data Source: Canaccord)

Apple's share of profits in early 2015 was remarkable because it sold less than 20% of smartphones but took in 92% of global smartphone profits. Because most Chinese brands (together with Samsung from Korea) are based on Google's Android operating system, it is increasingly difficult to differentiate their products in a highly mature smartphone market. In their high-end products, almost all brands include better cameras and screens, more powerful processors, cooler designs that leverage high quality and innovative materials. To some extent, the smartphone market is beginning to resemble the personal computer (PC) market, where the products are competing in a very saturated market, and most manufacturers struggle to break even. Based on its exclusive ecosystem and branding power, Apple is able to charge a higher price for its iPhones as well as laptops and iMacs to achieve profit dominance.

Of course, the disparity in profits could be partly explained by the different strategies taken by the manufacturers. For example, Xiaomi brands itself as an Internet company that chooses to sell cheaply-priced phones to acquire a large number of users quickly so that it can later focus on more profitable apps and downloads, phone accessories and add-on services. In addition, the Chinese tech companies including Xiaomi believe the global war on smart devices will be decided eventually on a much bigger battlefield than that represented by the smartphone market. As seen in the case of connected cars, all these Chinese players are seeking to tie users into an expanding family of smart devices and internet services.

So far, Chinese tech companies have already proven their mettle by catching up to global rivals in the smartphone and fourth-generation (4G) technology development process. They are now joining a fiercely competitive global race to become the first companies to offer fifth-generation (5G) wireless networks and products to global customers. Many Chinese firms are moving aggressively into the future state of a multi-device and hyper-connected world, which is “Smart 2.0” in ZTE's terminology, “convergence of telecom and IT” in Huawei's, and “all-inclusive ecosystem” in Xiaomi's.

The 5G technology's most visible advantage is its data transfer speeds, which is expected to be 1,000 times faster than that of 4G technology. The high-speed and highly stable 5G services are expected to encompass wireless applications that go far beyond basic internet communication to include driverless smart cars and more. Ultimately, 5G is the infrastructure for the “Internet of Things” (IoT), a loose term used to describe a network of mobile internet, smart devices, home appliances and any physical objects that interact through cloud technology. For example, the faster data transmission rates are expected to provide a constant and reliable stream of real-time street data that is required for driverless cars to function effectively and safely.

Huawei, ZTE and other Chinese tech firms have spent heavily on 5G research, as 5G represents a technological as well as a business revolution. More than 500 Huawei researchers have reportedly been working on the technology since 2009, and the firm is in the middle of a six-year, $600 million 5G research and development program. In July 2015, Huawei CEO Hu Houkun announced that the company planned to finish drafting its 5G standards by the end of 2018 and start commercial deployment in 2020.

Huawei's major rival, ZTE, also launched a 5G research effort in 2009. In ZTE's Smart 2.0 vision, every device – whether smartwatch or conventional refrigerator – is connected to a network, every network – whether highways or cable – is a pipe for objects and information, and every product is customized to individual users based on their unique requirements. According to its own disclosures, ZTE has established eight 5G research centers – four in China, three in the US and one in Europe. Overall, Chinese companies have secured a stronger position in the 5G development process than they had during the run-up to the roll-out of 4G, and China may well play a leading role in setting global standards for 5G technology as a result.

In addition to internal research and organic innovation, Chinese firms also actively acquire research and development capabilities from external markets. As seen in the Baidu/Uber and Lenovo/Motorola Mobility cases, Chinese firms are taking significant equity stakes in foreign firms, and in many cases they are beginning to complete full takeovers. Increasingly, Chinese firms are interested in acquiring cutting-edge technology development by investing in start-ups, especially in Silicon Valley that is still viewed as a key source of innovation and the capital of the mobile internet. Alibaba as well as Baidu and Tencent have collectively invested billions of dollars in these start-ups (see Table 10.3 on recent investments by Alibaba).

Table 10.3 Alibaba's recent investments into US Start-ups

| US Start-ups | Business sector | Amount($ millions) | Date |

| Snapchat | Mobile messaging | $200 | March 2015 |

| Peel | Smart TV mobile app | $50 | October 2014 |

| Kabam | Mobile gaming developer | $120 | August 2014 |

| Lyft | On demand ride-sharing | $250 | April 2014 |

| TangoMe | Social messaging | $280 | March 2014 |

| Shoprunner | Members-only e-commerce | $206 | October 2013 |

| Quixey | “Deep” search engine for information in mobile apps | $50 | October 2013 |

(Data Sources: News Reports and Public Disclosure)

As Chinese companies are dealing with the same in their attempts to grow their business as many US companies, their cooperation may lead to promising cross-pollination of tech innovation. As mentioned previously, Alibaba is working with its portfolio company Quixey to innovate in the area of mobile searching. When compared to traditional search engine searches, mobile searches are more opaque and could be described as scattered. For example, information on a restaurant and its promotion deals is spread over multiple apps for map information, group purchases, consumer reviews and so on. The two companies are now combining their capabilities to develop a “deep search” function to consolidate the information held on multiple apps into one search function so that the users do not have to install and run the individual apps themselves.

It is worth noting that through their investment relationships, the Chinese firms also provide the young companies with valuable insight into China, a market that an ambitious company cannot afford to miss, but at the same time is really difficult to penetrate. For a foreign start-up, it can be advantageous to align with a strategic partner who understands customer behavior, potential competitors, marketing and distribution, and numerous other barriers to entry in the local market. For example, when Tango's gaming and social network business plans to expand beyond the US, Tencent is a formidable incumbent. And, the company that has the best understanding of Tencent other than Tencent is probably Alibaba. As seen in the description of the taxi-hailing market, the player who best understands Alibaba and Tencent and their strengths and weaknesses is Baidu.

In conclusion, in the near future the Chinese market is poised to be a trend-setter, rather than the trend-follower, especially when it comes to next-generation mobile devices and services. One critical component playing into their hands is access to user data, which in the digital era is becoming a significant asset, although it is rarely recorded on corporate balance sheets (sooner or later it must be). With more than half of the 1.4 billion population being internet users, the data in the possession of the Chinese players focused on the consumer market is second to none. It is the oil of the information economy and the source of future Chinese designed products and business models.

In addition to the unrivalled internet user population size, what also makes the market unique is the fact that China is the largest “mobile-first” and “mobile-only” market in the world. For many people in China, especially in rural areas, their first internet experience is often mobile instead of connected to a personal computer of any type – their engagement with products and services begins the moment he or she starts using a smartphone. For example, as seen in the earlier mobile payment discussions, the lack of a widely-spread credit card system in China means that mobile payment are the “first” and “only” non-cash payment options for a vast majority of users.

As a result of these unique conditions, China's digital market has evolved in a very different way from the Western world, moving more aggressively into mobile or originating in mobile in the first instance. Mobile users can book movie tickets, order wedding services and manage financial investments using their smartphones and are comfortable in doing this too. As illustrated in the Uber China case, new mobile applications can potentially achieve significant scale more quickly in China than elsewhere. Because of the very rich array of mobile apps vying for a space in Chinese people's daily lives, in an extreme case the general public actually believed there was a mobile app providing “thugs for hire”. (See the “Didi Daren” box.)

When Tencent launched its first instant messaging product named QQ years ago, the product was viewed as a replica of the same system on which Yahoo Messenger and MSN Messenger were based. More recently, when Tencent started the new mobile app WeChat, it was compared to Facebook and WhatsApp, because WeChat was first and foremost a messaging app for sending text, voice and photos to friends and family. Today, however, WeChat as well as QQ have evolved into much more complex and multi-faceted mobile platforms that seem only very loosely related to their foreign counterparts.

To satisfy Chinese mobile users’ needs, Tencent has built an entire ecosystem of interrelated services around the WeChat platform. Alongside text, video and voice messaging, WeChat users can now shop and make payments, play games, book hotels or flight tickets, order a taxi and do many other things without ever leaving the app ecosystem. The critical component binding it all together is the mature mobile payment system, which makes the integrated services provided by the app more relevant in China than in the US. Another special feature is its voice input capability, which allows users to bypass the cumbersome process of writing Chinese characters on phone screens.

“In the next five years, there will be more innovation, more invention, more entrepreneurship happening in China, happening in Beijing than in Silicon Valley,” said Travis Kalanick, the founder of the world's most valuable start-up Uber Technologies at an early 2016 Beijing conference. “We gotta play our A-game in order to compete with the best.” Indeed, the planned merger between Uber China and Didi has illustrated not only the fierce competition in this cutting-edge market, but also the potential opportunity for a nimble and fast-growing entrant. Uber's continuing deep involvement with the Chinese market, irrespective of whether the merger will be approved or not, may be a harbinger of more external entrants arriving in China to look for new markets and develop new features, products as well as business models. Backed by the emerging ecosystem of entrepreneurship in China, the story of China is rapidly transforming from the old “Made in China” factories to the younger “Innovated in China”.