This chapter begins by discussing a few of the tools that you will use throughout the book. Next, we cover the OSI (Open Systems Interconnection) model and discuss how it relates to networking. We talk about all seven layers of the OSI model. Then we move on to the TCP/IP model and show its relation to the OSI model. We end the chapter discussing well-known port numbers, the different types of networks, and Cisco’s hierarchical internetwork model.

So you want to become a good network engineer? Let us give you some advice: do not believe that you know everything there is to know about networking. No matter what certifications or years of experience you have, there will always be gaps in knowledge and people who know or have experienced issues that you may not have. Troubleshoot issues systematically from layer to layer. Use your resources—such as this book! You can never have too many resources at your disposal in your toolbox. Do not be afraid to ask for help. Do not be ashamed because you cannot resolve a problem. That is why we have teams of engineers. Everyone has their expertise, and we must use each to our advantage. Remember when dealing with networks, it is always better to have a second pair of eyes and another brain to help resolve issues quickly. This will help you save time and stop you from working in circles. You want to know how you can become a good network engineer? Start by reading this book and complete the lab exercises to reinforce what you have learned. The rest will come from experience on the job. Practice makes perfect!

Tools of the Trade

The best way to learn is by doing, and the best way to remember is by repetition. In order to learn real-life network designs and issues, it is best to have a lab. You can have a real or a virtual lab; however, it is more cost effective to have a virtual lab. In modern times, almost all vendors have implementations of their devices in virtual machines (VMs), many of them with significant trial periods that allow you to learn the basics of the technology. However, if you or your organization can afford, it is always best to have a lab with real physical devices since virtual devices have limitations or do not implement all features of the real physical devices.

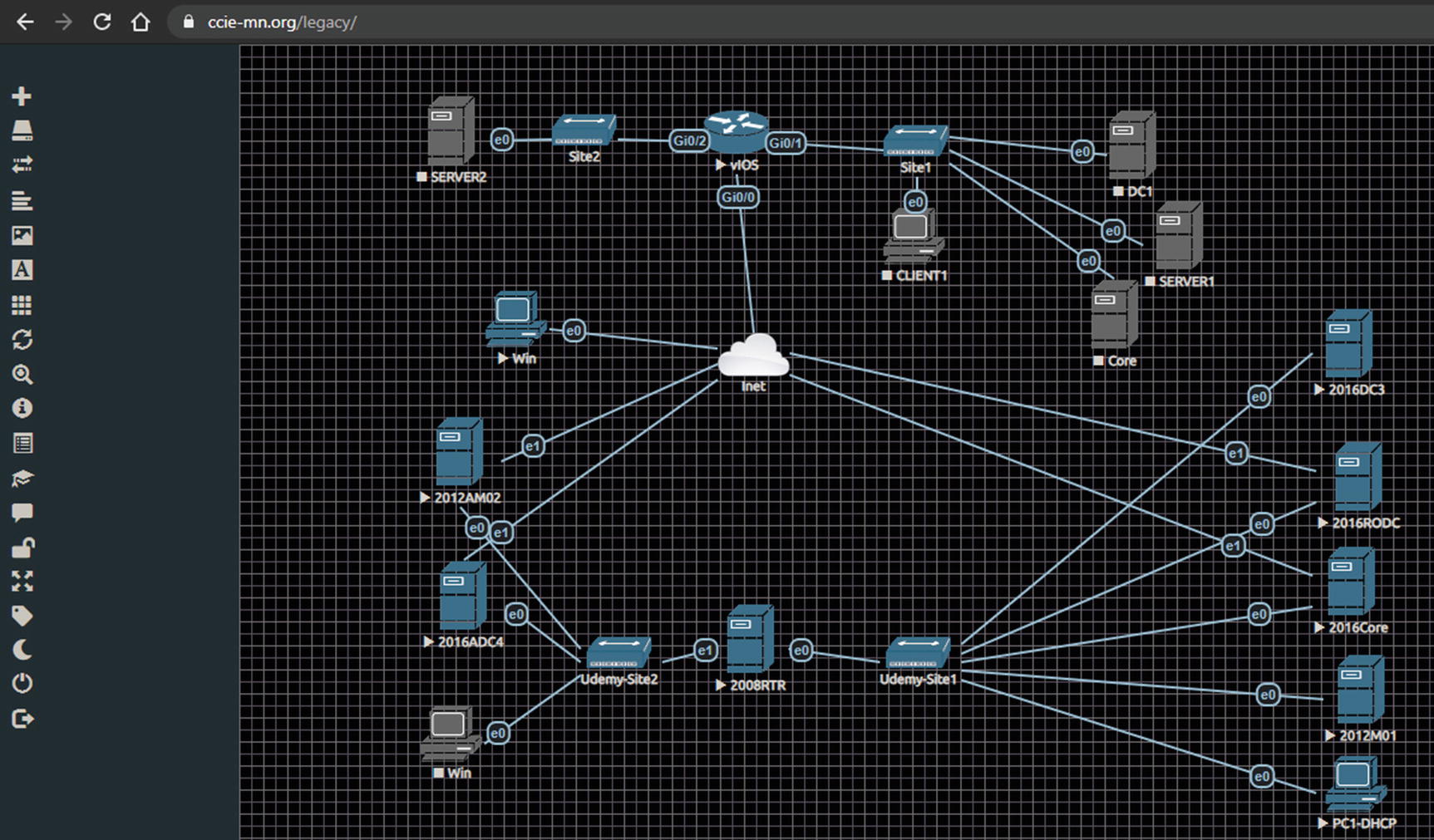

EVE-NG web-based UI

Another great simulation environment tool is the Graphical Network Simulator-3 (GNS3), and our tool of choice to peek into the network packets is Wireshark. There are other tools that you can use, but we found these two to be the easiest and most straightforward. Just in case you want to look at other options, a quick Internet search for “network simulators” and “network sniffers” will provide a list of the available alternatives to GNS3 and Wireshark, respectively.

GNS3 provides a simple all-in-one distribution that integrates Wireshark, VirtualBox, Qemu, and Dynamips among other tools, allowing simulation of network devices and virtualized workstations or servers. A simple visit to www.gns3.com and www.wireshark.org or a search on YouTube will glean vast amounts of information on how to use the tools. You need to be able to get an IOS (Internetwork Operating System) image; do not violate any license agreements. We will use GNS3 and Wireshark exclusively throughout this book.

Cisco Packet Tracer is a network simulation tool that allows you to simulate the configuring, operation, and troubleshooting of network devices. For more information, visit www.netacad.com/web/about-us/cisco-packet-tracer.

Cisco Virtual Internet Routing Lab (VIRL) is a network simulation tool that uses virtual machines running the same IOS as Cisco’s routers and switches. It allows you to configure and test real-world networks using IOS, IOS-XE, IOS-XR, and NX-OS. For more information, visit http://virl.cisco.com. For the 1.x branch of the application, VIRL was the name of the personal product, and Cisco Modeling Labs (CML) was the corporate version. In version 2.0, the names were merged, and VIRL is being renamed to CML Personal Edition. CML 2.0 Personal Edition is a significant improvement over VIRL 1.x. It replaced the thick client with an HTML5 interface and made several efficiency updates. It is available at https://learningnetworkstore.cisco.com/cisco-modeling-labs-personal/cisco-cml-personal.

Open Systems Interconnection (OSI) Model

Before we define the OSI model, let’s talk about why it should be important to you. First, the OSI model is something you should understand and not just gloss over. We understand that the thought of the model can put people to sleep if you have not had that morning coffee yet, but it can be an immense aid if you know how protocols communicate with one another and how each layer operates with another. How is it that a PC can communicate using so many protocols, or why can many companies create technologies that interoperate with others’ technologies? Even though you may be a network engineer and think that you will only work at layers 2 and 3, it is important to know and understand how all the layers of OSI function. This will aid you when it comes to troubleshooting layer 1 and many of the applications you may use to monitor your devices. If you know the OSI model, you can create your own troubleshooting methodology. Gaining the theory and the hands-on practice allows you to know which layers to troubleshoot after you have tested a cable, as data gets closer to the device of the end user. Now that you know how important it is, let’s talk about the OSI model.

The OSI model is a conceptual model, also known as the seven-layer model , which was established by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and the International Telecommunication Union Telecommunication Standardization Sector (ITU-T) to develop commonality in function and interface between communication protocols.

OSI Model

Layer Number | Name of Layer |

|---|---|

7 | Application |

6 | Presentation |

5 | Session |

4 | Transport |

3 | Network |

2 | Data link |

1 | Physical |

The OSI model breaks up/groups functions of communication into seven logical layers: physical, data link, network, transport, session, presentation, and application. Each layer supports the layer above it and is served by the level below it. It is important to note that processing is self-contained and transparent to the other layers. The application, presentation, and session layers define how applications within end units communicate with one another and users. Traditional examples of end units on a network are PCs, servers, printers, and scanners. However, with the evolution of the Web of Things, even your appliances and lightbulbs could be end units.

The physical, data link, network, and transport layers define how data is transmitted from source to destination. The lower layers are important in the processing of intermediary devices such as routers. Table 1-1 shows the seven layers. The layers will be discussed in more detail later in the chapter.

It standardizes the industry and defines what occurs at each layer of the model.

By standardizing network components, it allows many vendors to develop products that can interoperate.

It breaks the network communication processes into simpler and smaller components, allowing easier development, troubleshooting, and design.

Problems in one layer will be isolated to that layer during development, in most cases.

Functions of Layers in the OSI Model

Layer # | OSI Model Layer | Function | CEO Letter Analogy |

7 | Application | Support for application and end user processes | The CEO of a company in New York decides they need to send a letter to a peer in Los Angeles. They dictate the letter to their administrative assistant. |

6 | Presentation | Data representation and translation, encryption, and compression | The administrative assistant transcribes the dictation into writing. |

5 | Session | Establishes, manages, and terminates sessions between applications | The administrative assistant puts the letter in an envelope and gives it to the mail room. The assistant doesn’t actually know how the letter will be sent, but they know it is urgent, so they instruct, “Get this to its destination quickly.” |

4 | Transport | Data transfer between end systems and hosts, connections, segmentation and reassembly, acknowledgments and retransmissions, flow control and error recovery | The mail room must decide how to get the letter where it needs to go. Since it is a rush, the people in the mail room decide they must use a courier. The company must also decide if they would like a delivery receipt notification or if they will trust the courier service to complete the task (TCP vs. UDP). The envelope is given to the courier company to send. |

3 | Network | Switching and routing; logical addressing, error handling, and packet sequencing | The courier company receives the envelope, but it needs to add its own handling information, so it places the smaller envelope in a courier envelope (encapsulation). The courier then consults its airplane route information and determines that to get this envelope to Los Angeles, it must be flown through its hub in Dallas. It hands this envelope to the workers who load packages on airplanes. |

2 | Data link | Logical link control (LLC) layer, media access control (MAC) layer, data framing, addressing, error detection and handling from the physical layer | The workers take the courier envelope and affix a tag with the code for Dallas. They then put it in a handling box and load it on the plane to Dallas. |

1 | Physical | Encoding and signaling, physical transmission of data, defining medium specifications | The plane flies to Dallas. |

2 | Data link | Logical link control layer, media access control layer, data framing, addressing, error detection and handling from the physical layer | In Dallas, the box is unloaded, and the courier envelope is removed and given to the people who handle routing in Dallas. |

3 | Network | Switching and routing; logical addressing, error handling, and packet sequencing | The tag marked “Dallas” is removed from the outside of the courier envelope. The envelope is then given to the airplane workers for it to be sent to Los Angeles. |

2 | Data link | Logical link control layer, media access control layer, data framing, addressing, error detection and handling from the physical layer | The envelope is given a new tag with the code for Los Angeles, placed in another box, and loaded on the plane to Los Angeles. |

1 | Physical | Encoding and signaling, physical transmission of data, defining medium specifications | The plane flies to Los Angeles. |

2 | Data link | Logical link control layer, media access control layer, data framing, addressing, error detection and handling from the physical layer | The box is unloaded, and the courier envelope is removed from the box. It is given to the Los Angeles routing office. |

3 | Network | Switching and routing; logical addressing, error handling, and packet sequencing | The courier company in Los Angeles sees that the destination is in Los Angeles and delivers the envelope to the destination CEO’s company. |

4 | Transport | Data transfer between end systems and hosts, connections, segmentation and reassembly, acknowledgments and retransmissions, flow control and error recovery | The mail room removes the inner envelope from the courier envelope and delivers it to the destination CEO’s assistant. |

5 | Session | Establishes, manages, and terminates sessions between applications | The assistant takes the letter out of the envelope. |

6 | Presentation | Data representation and translation, encryption, and compression | The assistant reads the letter and decides whether to give the letter to the CEO, transcribe it to email, or call the CEO. |

7 | Application | Support for application and end user processes | The CEO receives the message that was sent by their peer in New York. |

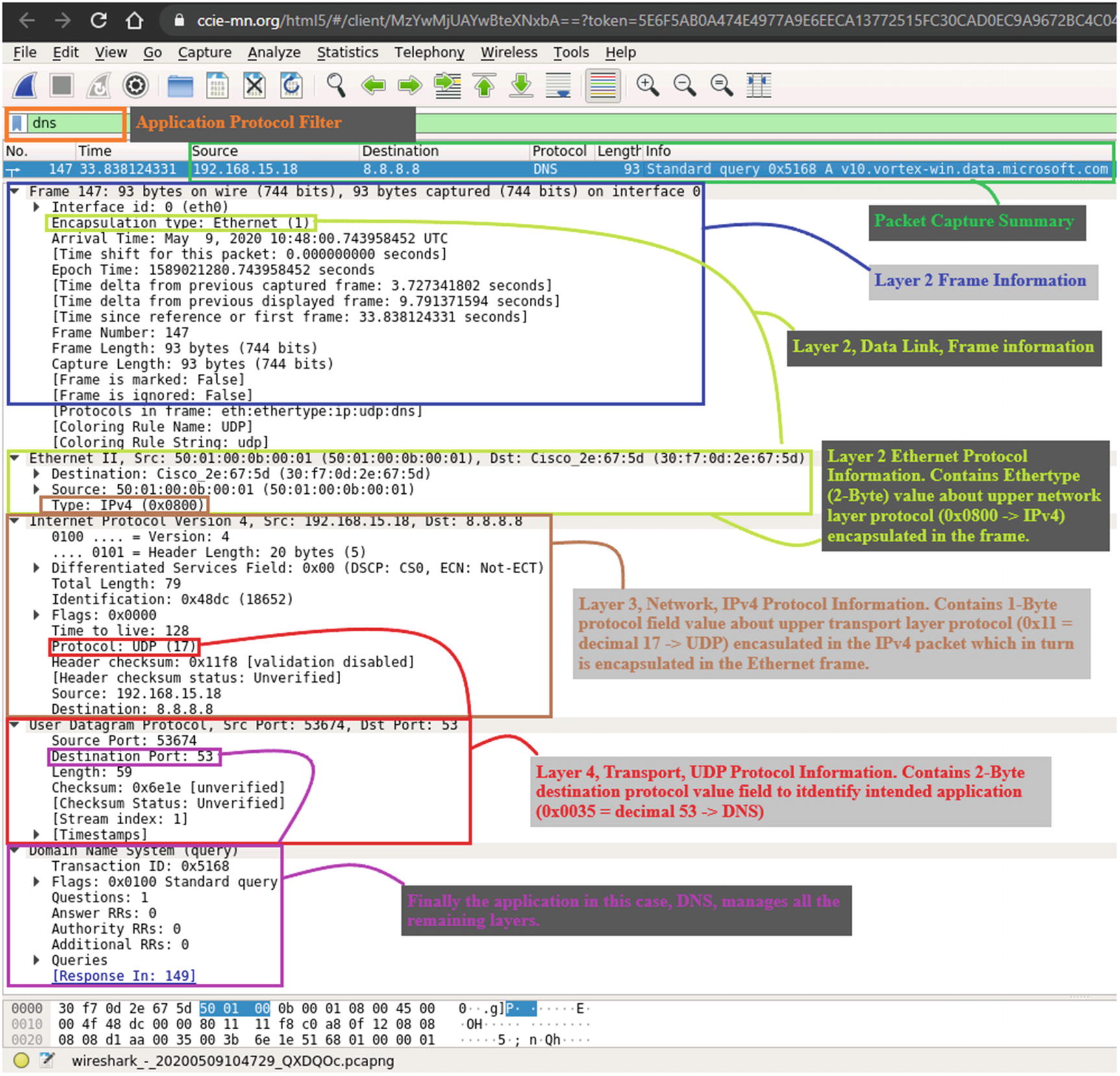

Wireshark DNS packet capture and OSI layers

Physical Layer

The medium of transmission

The physical manifestation of energy for transmission (e.g., light)

The channel characteristics (half duplex, full duplex, serial, parallel)

The methods for error recovery

The timing for synchronization

The range of transmission

The energy levels used for transmission

Data Link Layer

The data link layer provides services to the layer above it (the network layer) and provides error handling and flow control. This layer must ensure that messages are transmitted to devices on a local area network (LAN) using physical hardware addresses. It also converts packets sent from the network layer into frames to be sent out to the physical layer to transmit. The data link layer converts packets into frames, adding a header containing the device’s physical hardware source and destination addresses, flow control, and checksum data (CRC) . The additional information is added to packets from a layer, or a capsule around the original message, and when the message is received at the distant end, this capsule is removed before the frame is sent to the network layer for processing at that layer. The data frames created by the data link layer are transmitted to the physical layer and converted into some type of signal (electrical or electromagnetic). Please note that devices at the data link layer do not care about logical addressing, only physical. Routers do not care about the actual location of your end user devices, but the data link layer does. This layer is responsible for the identification of the unique hardware address of each device on the LAN.

Media access control (MAC ) 802.3: This layer is responsible for how packets are transmitted by devices on the network. Media access is first come/first served, meaning all the bandwidth is shared by everyone. Hardware addressing is defined here, as well as the signal path, through physical topologies, including error notification, correct delivery of frames, and flow control. Every network device, computer, server, IP camera, and phone has a MAC hardware address.

Logical link control (LLC) 802.2: This layer defines and controls error checking and packet synchronization. LLC must locate network layer protocols and encapsulate the packets. The header of the LLC lets the data link layer know how to process a packet when a frame is received.

As mentioned, the MAC layer is responsible for error notification, but this does not include error correction; this responsibility goes to the LLC. When layer 2 frames are received at the end device, the LLC recalculates the checksum to determine if the newly calculated value matches the value sent with the frame. The end device will transmit an acknowledgement signal to the transmitting end unit if the checksum values match. Else, the transmitting end device will retransmit the frame, since it is likely the frame arrived at its destination with corrupted data or did not arrive at all.

Fiber Distributed Data Interface (FDDI ): A legacy technology, but it may still be used in some networks today.

Asynchronous Transfer Mode (ATM ): A legacy technology, but it may still be used in some networks today.

Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) 802.2 (LLC).

IEEE 802.3 (MAC).

Frame Relay : A legacy technology, but it may still be used in some networks today.

PPP (Point-to-Point Protocol).

High-Level Data Link Control (HDLC) : A legacy technology, but it may still be used in some networks today.

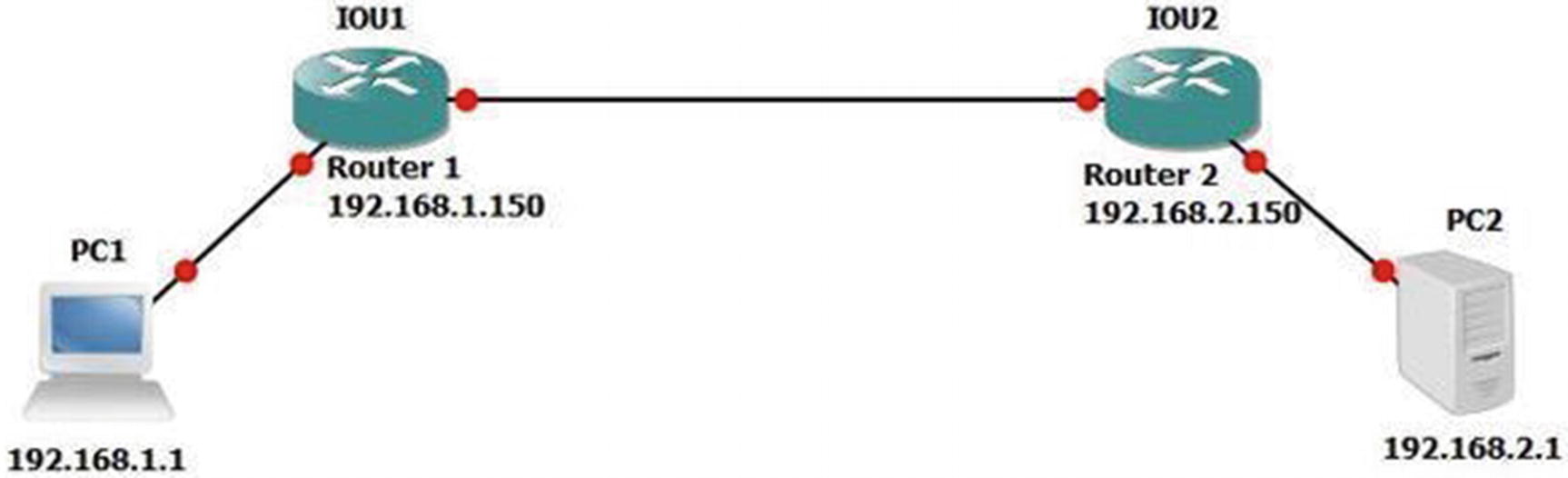

Network Layer

The network layer provides logical device addressing, determines the location of devices on the network, and calculates the best path to forward packets. Routers are network layer devices that provide routing within networks. This layer provides routing capabilities, creating logical paths or virtual circuits to transmit packets from source to destination. The network layer handles logical packet addressing and maps logical addresses into hardware addresses, allowing packets to reach their endpoint. This layer also chooses the route that packets take, based on factors such as link cost, bandwidth, delay, hop count, priority, and traffic.

Networking example

Network layer examples include routing protocols such as Open Shortest Path First (OSPF), Routing Information Protocol (RIP), Enhanced Interior Gateway Routing Protocol (EIGRP), Border Gateway Protocol (BGP), Internet Protocol version 4/6 (IPv4/IPv6), Internet Group Management Protocol (IGMP), and Internet Control Message Protocol (ICMP).

Transport Layer

The transport layer segments and reassembles data for the session layer. This layer provides end-to-end transport services. The network layer allows this layer to establish a logical connection between source and destination hosts on a network. The transport layer is responsible for establishing sessions and breaking down virtual circuits. The transport layer communications can be connectionless or connection-oriented, also known as reliable .

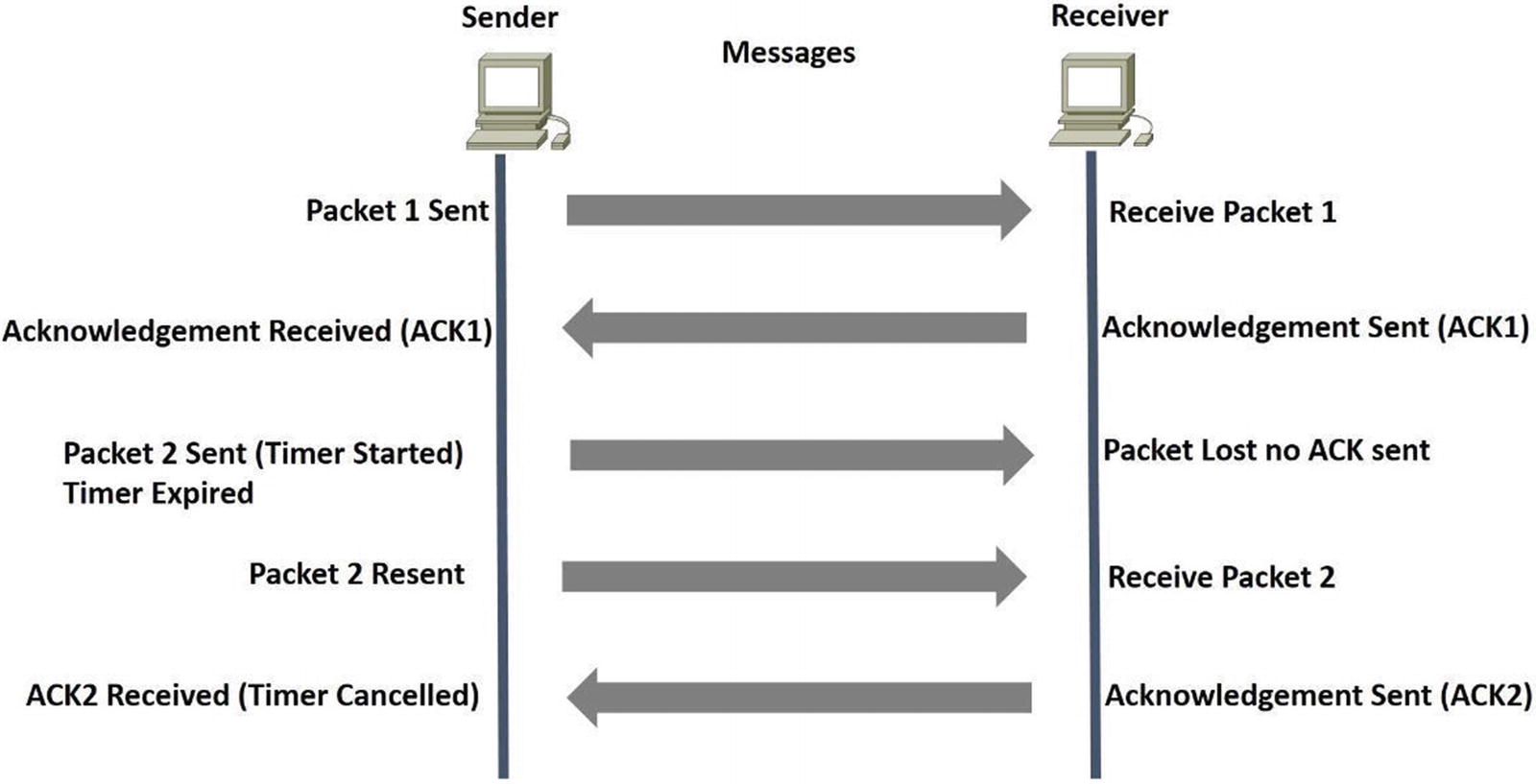

Acknowledgement sent from the receiver to the sender upon receipt of the segments.

If a segment is not acknowledged, it will be retransmitted by the sender.

Segments are reorganized into their proper order once received at the destination.

Congestion, overloading, and data loss are avoided through flow control.

Connection-Oriented

In reliable transport, when a device wants to transmit, it must set up connection-oriented communication by creating a session with a remote device. The session is set up by completing a three-way handshake. Once the three-way handshake is complete, the session resembles a virtual circuit for the communication. A connection-oriented session implies that the method of communication is bidirectional, and the receiving party is expected to acknowledge the data received. The connection-oriented session analogy is akin to having a conversation (not a monologue) with someone. After the transfer is complete, the session is terminated, and the virtual circuit is torn down. During the establishment of the reliable session, both hosts must negotiate and agree to certain parameters to begin transferring data. Once the connection is synchronized and established, traffic can be processed. Connection-oriented communication is needed when trying to send files via file transfer, as a connection must be made before the files can be sent. Connectionless communication is used for applications that require fast performance, such as video chatting.

Session Layer

The session layer is responsible for establishing, managing, and terminating sessions between local and remote applications. This layer controls connections between end devices and offers three modes of communication: full-duplex, half-duplex, or simplex operation. The session layer keeps application data away from other application data. This layer performs reassembly of data in connection-oriented mode while data is passed through, whereas data is not modified when using connectionless mode. The session layer is also responsible for the graceful close of sessions, creating checkpoints, and recovery when data or connections are interrupted. This layer has the ability to resume connections or file transfers where they stopped last.

Structure Query Language (SQL) : An IBM development designed to provide users with a way to define information requirements on local and remote systems

Remote Procedure Call (RPC) : A client-server redirection tool used for disparate service environments

Network File System (NFS ): A Sun Microsystems development that works with TCP/IP and UNIX desktops to allow access to remote resources

Presentation Layer

The presentation layer translates data, formats code, and represents it to the application layer. This layer identifies the syntax that different applications use and encapsulates presentation data into session protocol data units and passes these to the session layer, ensuring that data transferred from the local application layer can be read by the application layer at the remote system. The presentation layer translates data into the form that specific applications recognize and accept. If a program uses a non-ASCII code page, this layer will translate the received data into ASCII. This layer also encrypts data to be sent across the network. The presentation layer also can compress data, which increases the speed of the network. If the data is encrypted, it can only be decrypted at the application layer on the receiving system.

Joint Photographic Experts Group (JPEG) : Photo standards

Moving Picture Experts Group (MPEG) : Standard for compression and coding of motion video for CDs

Tagged Image File Format (TIFF ): A high-resolution graphics format

Rich Text Format (RTF) : A file format for exchanging text files from different word processors and operating systems

Application Layer

The application layer interfaces between the programs sending and receiving data. This layer supports end user applications. Application services are made for electronic mail (email), Telnet, File Transfer Protocol (FTP) applications, and file transfers. Quality of Service, user authentication, and privacy are considered at this layer due to everything being application specific. When you send an email, your email program contacts the application layer.

World Wide Web (WWW) : Presents diverse formats—including multimedia such as graphics, text, sound, and video connecting servers—to end users.

Email: Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP) and Post Office Protocol version 3 (POP3) are used to allow sending and receiving, respectively, of email messages between different email applications.

The OSI Model: Bringing It All Together

The Functions of Each Layer in the OSI Model

Name of Layer | Unit of Data Type | Purpose | Common Protocols | Hardware |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Application | User data | Application data | DNS, BOOTP, DHCP, SNMP, RMON, FTP, TFTP, SMTP, POP3, IMAP, NNTP, HTTP, Telnet, HTTPS, ping, NSLOOKUP, NTP, SFTP | Gateways, proxy servers, application switches, content filtering firewalls |

Presentation | Encoded user data | Application data representation | SSL, shells and redirectors, MIME, TLS (Transport Layer Security) | Gateways, proxy servers, application switches, content filtering firewalls |

Session | Session | Session between local and remote devices | NetBIOS, sockets, named pipes, RPC, RTP, SIP, PPTP | Gateways, proxy servers, application switches, content filtering firewalls |

Transport | Datagrams/segments | Communication between software processes | TCP, UDP, and SPX | Gateways, proxy servers, application switches, content filtering firewalls |

Network | Datagrams/packets | Messages between local and remote devices | IP, IPv6, IP NAT, IPsec, Mobile IP, ICMP, IPX, DLC, PLP, routing protocols such as RIP and BGP, ICMP, IGMP | Routers, layer 3 switches, firewalls, gateways, proxy servers, application switches, content filtering firewalls |

Data link | Frames | Low-level messages between local and remote devices | IEEE 802.2 LLC, IEEE 802.3 (MAC) Ethernet family, CDDI, IEEE 802.11 (WLAN, Wi-Fi), HomePNA, HomeRF, ATM, PPP, ARP, HDLC, RARP | Bridges, switches, wireless access points (Aps), NICs, modems, cable modems, DSL modems, gateways, proxy servers, application switches, content filtering firewalls |

Physical | Bits | Electrical or light signals sent between local devices | Physical layers of most of the technologies listed for the data link layer, IEEE 802.5 (Ethernet), 802.11 (Wi-Fi), E1, T1, DSL | Hubs, repeaters, NICs, modems, cable modems, DSL modems |

Let’s bring the OSI model together in a way where you can see the importance of each layer. How about using Firefox to browse to a website on a computer? You type apress.com into the web browser to contact the web server hosting the content you are requesting. This is at the application layer.

The presentation layer converts data in a way that allows images and text to be displayed and sounds to be heard. Formats at the presentation layer include ASCII, MP3, HTML, and JPG. When you requested to be directed to the apress.com web page, a TCP connection was created to the server using port 80. Each TCP connection is a session maintained by the session layer. The transport layer creates the TCP connections to break the web pages into datagrams that can be reassembled in the correct order and forwarded to the session layer. The network layer uses IP to locate the IP address of the web server via your default gateway. The web request is now sent to the data link layer, and it knows to use Ethernet to send the request. Finally, the transport layer uses the Ethernet for its transport protocol and forwards the website request to the server.

Examples of Applications and How Each Layer Helps the Applications Come Together

Application | Presentation | Session | Transport | Network | Data Link | Physical |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

POP/SMTP | 110/25 | TCP | IP | PPP, Ethernet, ATM, FDDI | CAT 1–6, ISDN, ADSL, ATM, FDDI, COAX | |

Websites | HTTP | 80 | TCP | IP | PPP, Ethernet, ATM, FDDI | CAT 1–6, ISDN, ADSL, ATM, FDDI, COAX |

Directory services, name resolution | DNS | 53 | TCP/UDP | IP | PPP, Ethernet, ATM, FDDI | CAT 1–6, ISDN, ADSL, ATM, FDDI, COAX |

Remote sessions | Telnet | 23 | TCP | IP | PPP, Ethernet, ATM, FDDI | CAT 1–6, ISDN, ADSL, ATM, FDDI, COAX |

Network management | SNMP | 161, 162 | UDP | IP | PPP, Ethernet, ATM, FDDI | CAT 1–6, ISDN, ADSL, ATM, FDDI, COAX |

File services | NFS | RPC Portmapper | UDP | IP | PPP, Ethernet, ATM, FDDI | CAT 1–6, ISDN, ADSL, ATM, FDDI, COAX |

File transfers | FTP | 20/21 | TCP | IP | PPP, Ethernet, ATM, FDDI | CAT 1–6, ISDN, ADSL, ATM, FDDI, COAX |

Secure websites | HTTPS | 443 | TCP | IP | PPP, Ethernet, ATM, FDDI | CAT 1–5, ISDN, ADSL, ATM, FDDI, COAX |

Secure remote sessions | SSH | 22 | TCP | IP | PPP, Ethernet, ATM, FDDI | CAT 1–6, ISDN, ADSL, ATM, FDDI, COAX |

TCP/IP

OSI Model Comparison to the TCP/IP Model with Functions of Each Layer

OSI Model | TCP/IP Model | Function |

|---|---|---|

Application | Application | The application layer defines TCP/IP application protocols and how programs interface with transport layer services using the network. |

Presentation | ||

Session | ||

Transport | Transport (host to host) | The transport layer handles communication session management between end systems. It also defines the level of service and the status of connections. |

Network | Internetwork | The Internet layer encapsulates data into IP datagrams, containing source and destination addresses used to route datagrams between end systems. |

Data link | Network interface | The network interface layer defines how data is actually sent through the network, including hardware devices and network media such as cables. |

Physical |

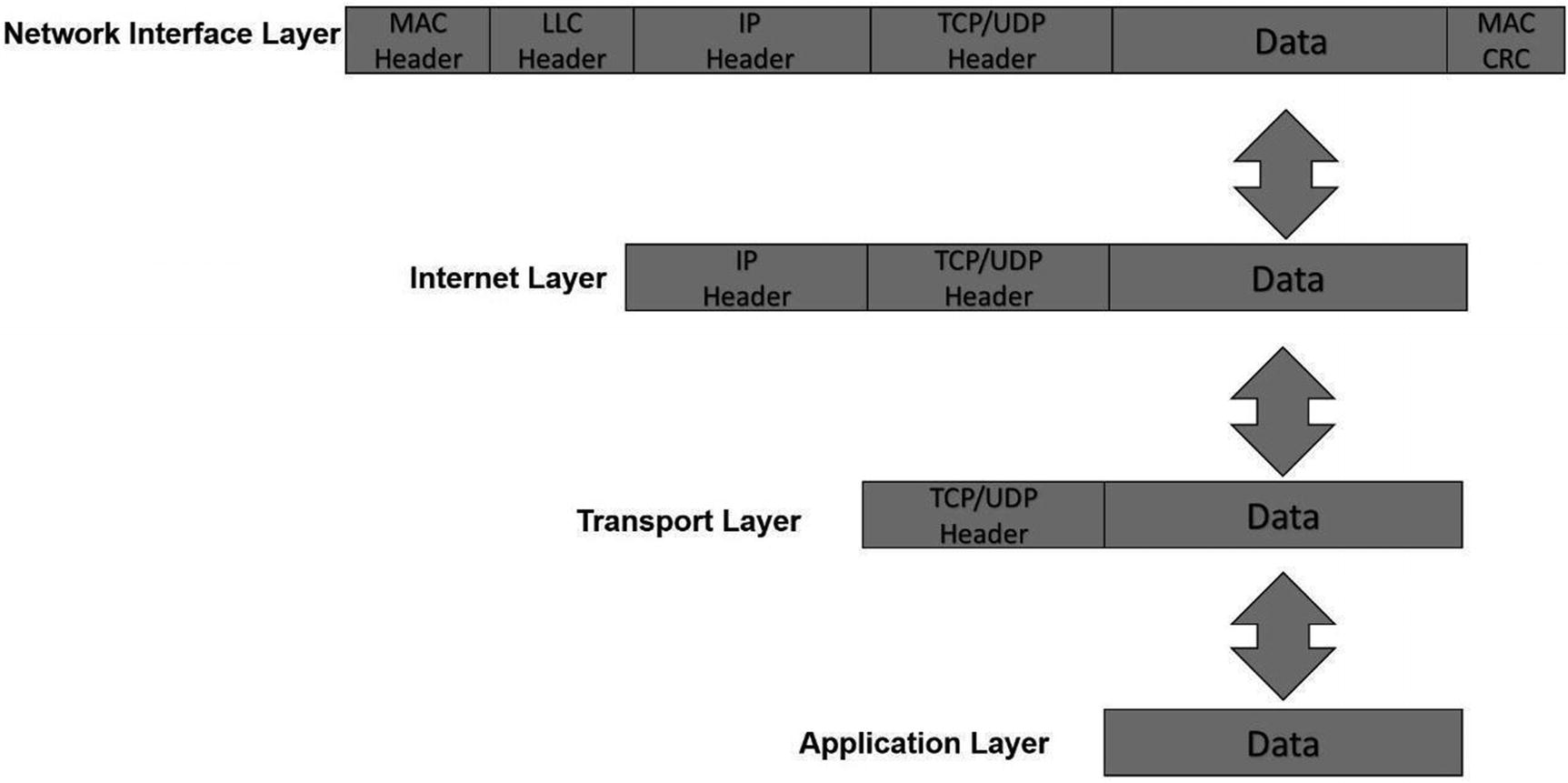

The application, presentation, and session layers in the OSI model correspond to the application layer in the TCP/IP model. The transport layer in the OSI model correlates with the transport layer in the TCP/IP model. The network layer in the OSI model correlates with the Internet layer in the TCP/IP model. The data link and physical layers correspond with the network interface layer in the TCP/IP model.

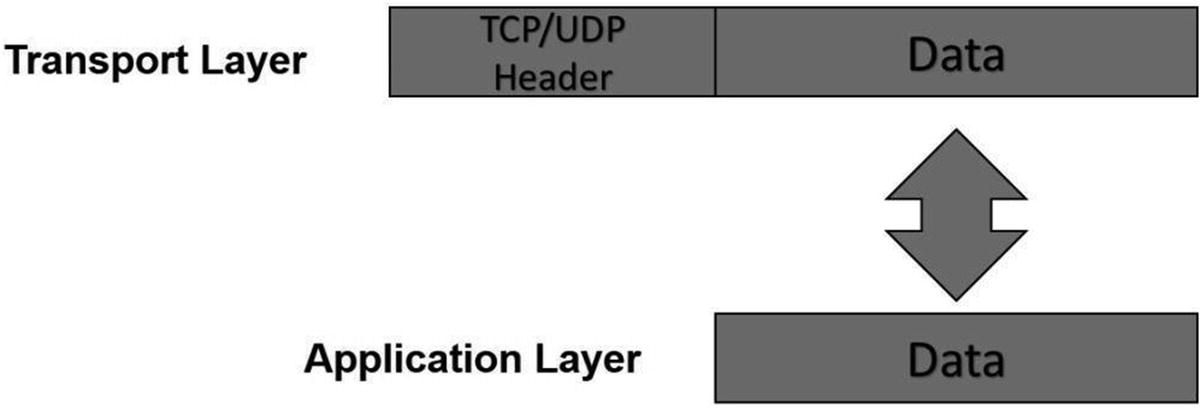

Similarly, when a sender transmits data via the TCP/IP, applications communicate with the application layer, which sends its data to the transport layer, which sends its data to the Internet layer, which sends its data to the network interface layer to send the data over the transmission medium to the destination.

Now we will dive into the layers of the TCP/IP model.

TCP/IP Application Layer

Programs communicate to the TCP/IP application layer. Many protocols can be used at this layer, depending on the program being used. This layer also defines user interface specifications.

Several protocols are used at this layer, most notably File Transfer Protocol (FTP) for file transfers, Simple Mail Transport Protocol (SMTP) for email data, and Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) for website traffic. This layer communicates with the transport layer via ports. The Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA) defines which ports are to be used for which application. Standard applications always listen on port 80 for the HTTP, the SMTP uses port 25, and the FTP uses ports 20 and 21 for sending data. The port number tells the transport protocol what type of data is inside the packet (e.g., what data is being transported from a web server to a host), allowing the application protocol at the receiving side to use port 80, which will deliver the data to the web browser that requested the data.

TCP/IP Transport Layer

The TCP/IP transport layer is identical to and performs the same functions as the transport layer in the OSI model. Two protocols can be used at this layer: Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) and User Datagram Protocol (UDP). The former is connection-oriented and the latter is connectionless, meaning that the TCP provides reliability and error-free delivery of data and also maintains data integrity. TCP is used for emails and website data, whereas UDP is usually used to send control data, including voice and other streaming data where speed is more important than retransmitting packets that are lost.

Transport layer packet

TCP/IP Internet Layer

The TCP/IP Internet layer correlates with the network layer in the OSI model and is responsible for routing and addressing. The most common protocol used at this layer is the Internet Protocol (IP). This layer logically addresses packets with IP addresses and routes packets to different networks.

The Internet layer receives packets from the transport layer, adds source and destination IP addresses to the packets, and forwards these on to the network interface layer for transmitting to the sender. The logical address (virtual addressing), also known as an IP address, allows the packet to be routed to its destination. Along the way, packets traverse many locations through routers before reaching their destination. To view an example of this, open your command prompt on your laptop or workstation. In the command prompt, enter tracert (or traceroute in Linux) apress.com. You will see the number of routers that the packet traverses to its destination.

Internet Protocol (IP) : The IP receives datagrams from the transport layer and encapsulates them into packets before forwarding to the network interface layer. This protocol does not implement any acknowledgement, and so it is considered unreliable. The header in the IP datagram includes the source and destination IP addresses of the sender and the receiver.

Internet Control Message Protocol (ICMP ): The ICMP is a major protocol in the IP suite that is used by network devices to send error messages to indicate that a host or router is unreachable.

Address Resolution Protocol (ARP) : ARP is used to map IP network addresses to the hardware address that uses the data link protocol. This will be discussed further in Chapter 3.

Reverse Address Resolution Protocol (RARP): RARP is used on workstations in a LAN to request its IP address from the ARP table.

Packet at the Internet layer with a header added to it

TCP/IP Network Interface Layer

The TCP/IP network interface layer relates to the data link and physical layers of the OSI model. It is responsible for using physical hardware addresses to transmit data and defines protocols for the physical transmission of data.

Datagrams are transmitted to the network interface layer to be forwarded to their destination. This layer is defined by the type of physical connection your computer has. Most likely it will be Ethernet or wireless.

The logical link control (LLC) layer is responsible for adding the protocol used to transmit data at the Internet layer. This is necessary so the corresponding network interface layer on the receiving end knows which protocol to deliver the data to at the Internet layer. IEEE 802.2 protocol defines this layer.

Packet at the network interface layer with headers and a trailer added to it

Reliability

Synchronize (SYN) : Used to initiate and set up a session and agree on initial sequence numbers.

Finish (FIN) : Used to gracefully terminate a session. This shows that the sender has no more data to transmit.

Acknowledgement (ACK) : Used to acknowledge receipt of data.

How TCP provides reliability

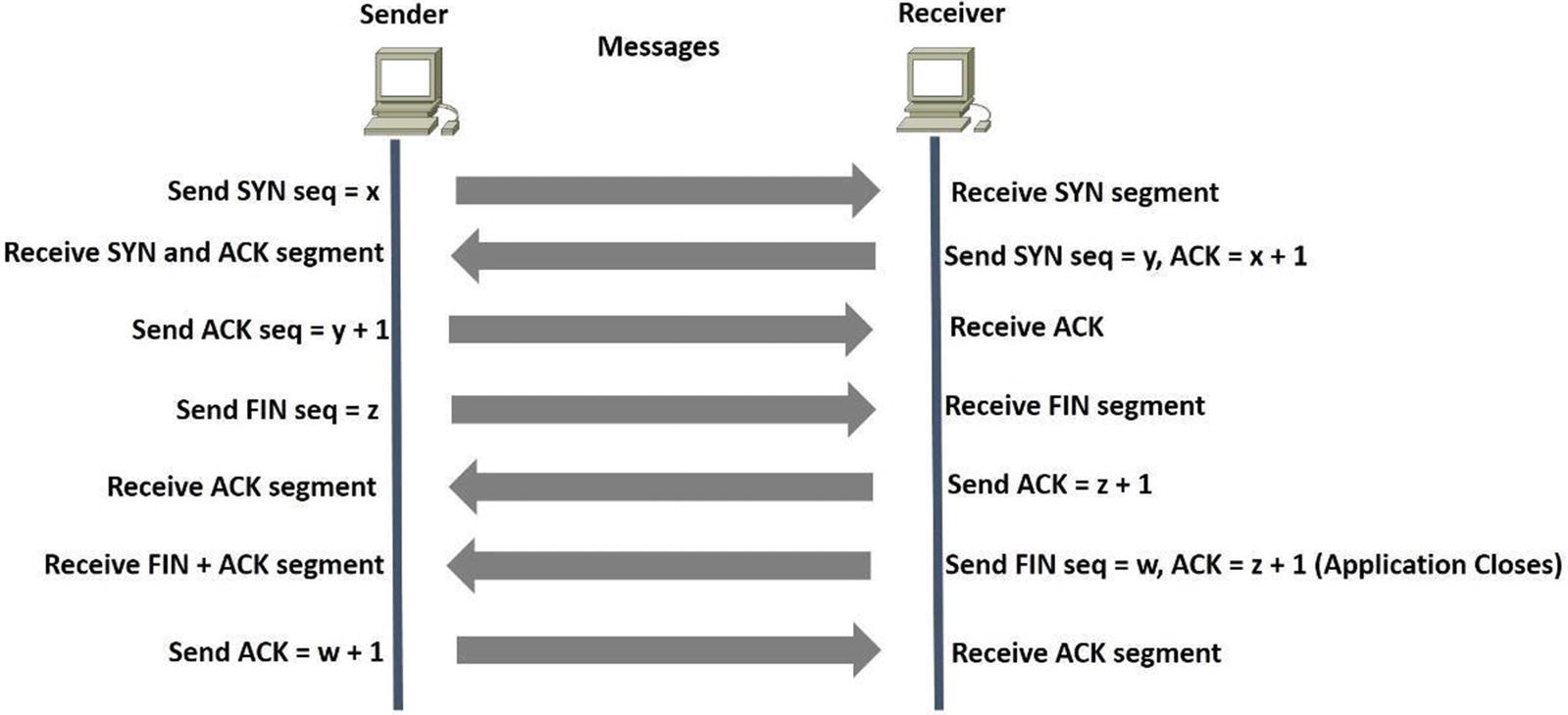

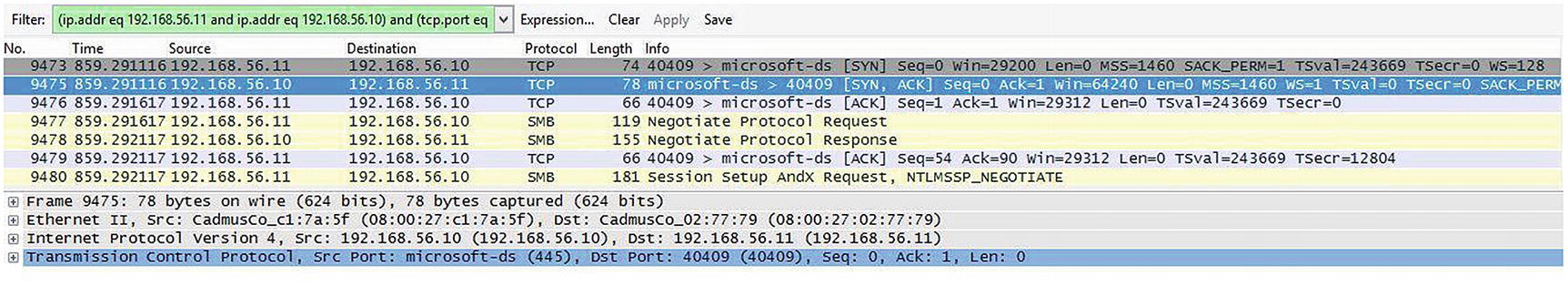

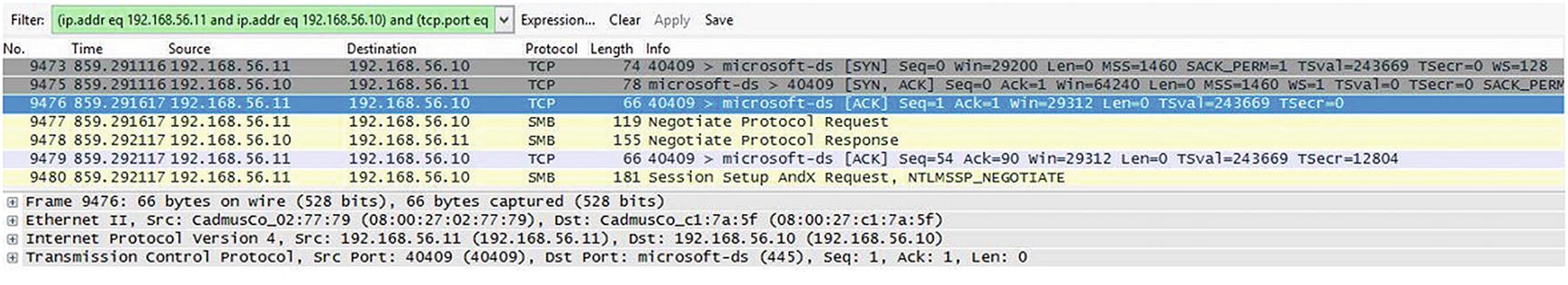

Three-Way Handshake and Connection Termination

When establishing a connection, TCP uses a three-way handshake. The process starts with a SYN sent by a client to a server. The server responds back with a SYN-ACK, with the acknowledgement being increased by one. Finally, the client sends an ACK back to the server to complete the connection setup.

The setup of the TCP three-way handshake and graceful termination of communication between peers

Wireshark SYN packet capture of the TCP three-way handshake

Wireshark SYN and ACK packet capture of the TCP three-way handshake

Wireshark ACK packet capture of the TCP three-way handshake

Figure 1-9 shows that the SYN sequence number starts at x=0.

Figure 1-10 shows that the SYN sequence number starts at y=0 and the ACK sequence number starts at x+1, which is 1.

Figure 1-11. shows that the ACK sequence number is y+1, which is 1.

User Datagram Protocol

The User Datagram Protocol (UDP) is a member of the IP suite. It uses a connectionless transmission model that does not complete any handshaking, thus referred to as unreliable. UDP does not provide guarantee of delivery or reordering or duplicate protection. Time-sensitive and real-time applications are known to use UDP, since dropping packets is preferred to waiting for delayed or lost packets to be resent. UDP has no concept of acknowledgements or datagram retransmission.

Port Numbers

Well-Known Port Numbers

Protocol | Port Number | Description |

|---|---|---|

TCP, UDP | 20, 21 | FTP |

TCP | 22 | SSH |

TCP, UDP | 23 | Telnet |

TCP | 25 | SMTP |

TCP, UDP | 49 | TACACS |

TCP, UDP | 53 | DNS |

UDP | 67 | DHCP |

UDP | 69 | TFTP |

TCP | 80 | HTTP |

TCP, UDP | 88 | Kerberos |

TCP | 110 | POP3 |

TCP, UDP | 161, 162 | SNMP |

TCP | 179 | BGP |

TCP | 443 | HTTPS |

TCP | 465 | SMTPS |

TCP, UDP | 500 | ISAKMP |

UDP | 514 | Syslog |

UDP | 520 | RIP |

TCP, UDP | 666 | DOOM |

TCP | 843 | Adobe Flash |

TCP | 989–990 | FTPS |

TCP, UDP | 3306 | MySQL |

TCP | 3689 | iTunes |

TCP, UDP | 3724 | World of Warcraft |

TCP | 5001 | Slingbox |

TCP, UDP | 5060 | SIP |

TCP | 6699 | Napster |

TCP, UDP | 6881–6999 | BitTorrent |

UDP | 14567 | Battlefield |

UDP | 28960 | Call of Duty |

Types of Networks

Personal area network (PAN)

Local area network (LAN)

Campus area network (CAN)

Metropolitan area network (MAN)

Wide area network (WAN)

Wireless wide area network (WWAN)

Personal Area Network

A personal area network (PAN) is a computer network organized around a single person within a single building, small office, or residence. Devices normally used in a PAN include Bluetooth headsets, computers, video game consoles, mobile phones, and peripheral devices.

Local Area Network

A local area network (LAN) normally consists of a computer network at a single location or office building. LANs can be used to share resources such as storage and printers. LANs can range from only two to thousands of computers. LANs are common in homes now, thanks to the advancements in wireless communication often referred to as Wi-Fi. An example of a LAN is an office where employees access files on a shared server or can print documents to multiple shared printers. Commercial home wireless routers provide a bridge from wireless to wired to create a single broadcast domain. Even though you may have a wireless LAN, most WLANs also come with the ability to connect cables directly to the Ethernet ports on them.

Campus Area Network

A campus area network (CAN) represents several buildings/LANs within close proximity. Think of a college campus or a company’s enclosed facility, which is interconnected using routers and switches. CANs are larger than LANs and, in fact, usually contain many LANs. CANs cover multiple buildings; however, they are smaller than MANs, as buildings in a CAN are generally on the same campus or within a really small geographical footprint (e.g., several buildings interconnected on the same street block or in a business park).

Metropolitan Area Network

A metropolitan area network (MAN) represents a computer network across an entire city or other region. MANs are larger than CANs and can cover areas ranging from several miles to tens of miles. A MAN can be used to connect multiple CANs; for example, London and New York are cities that have MANs set up.

Wide Area Network

A wide area network (WAN) is normally the largest type of computer network. It can represent an entire country or even the entire world. WANs can be built to bring together multiple MANs or CANs. The Internet is the best example of a WAN. Corporate offices in different countries can be connected to create a WAN. WANs may use fiber-optic cables or can be wireless by using microwave technology or leased lines.

Wireless Wide Area Network

A wireless wide area network (WWAN) is a WAN that uses wireless technologies for connectivity. It uses technologies such as LTE, WiMAN, UMTS, GSM, and other wireless technologies. The benefit of this type of WAN is that it allows connectivity that is not hindered by physical limitations. Most point-to-point (P2P) and point-to-multipoint (P2MP) wireless technologies are limited in distance; these networks are often referred to as wireless metropolitan area networks (WMANs). Due to the inherent open nature of wireless technology, most companies use some form of encryption and authentication.

Virtual Private Network

Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) can be used to allow employees to remotely access their corporate network from a home office or through public Internet access, such as at a hotel, or a wireless access point. VPNs can also connect office locations.

Types of networks

Hierarchical Internetwork Model

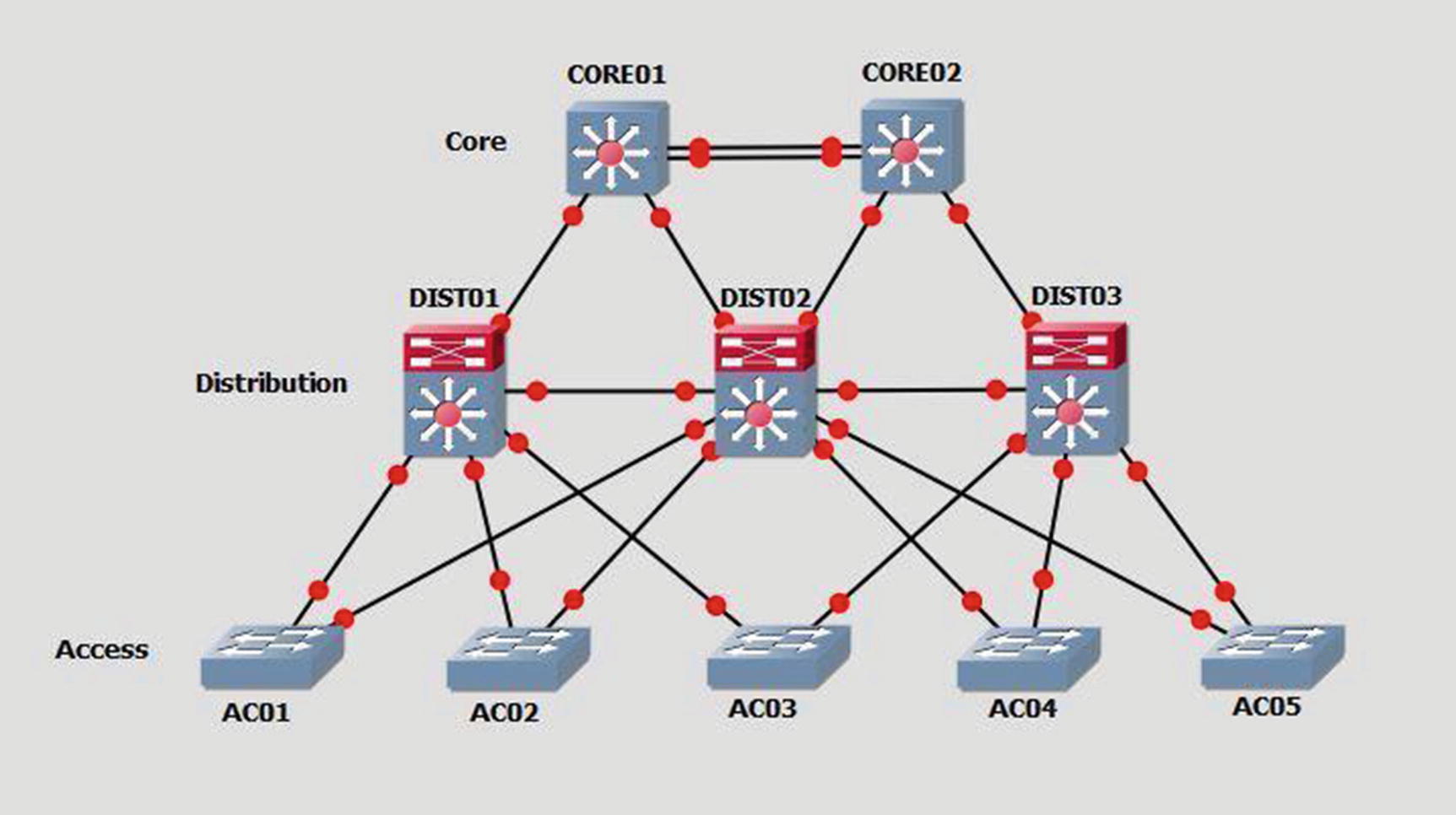

The hierarchical internetwork model was developed by Cisco; it is a three-layer model dividing networks into three layers. The layers are core, distribution, and access. Each layer is responsible for providing different services to end stations and servers.

One key component in network design is switching where you can and routing where you must, meaning that you should use switches wherever possible. Another key component is dividing network devices into zones, which separates user access networks from data centers. Separation can be achieved logically via routers and switches or firewalls. Access devices typically support end devices such as VoIP phones, printers, and computers. Networks can be divided on a per-floor basis or a per-office basis.

Hierarchical internetwork model

The distribution layer connects to the access layer or edge layer. This layer is focused on switching and can be connected redundantly to both the core and user switches. Uplinks to this device should also be groups of links to achieve maximum performance. Firewalls and NAT can be configured in the layer. Routing between VLANs (Virtual Logical Networks) and workgroups is done at this layer. The devices at this layer should be able to process a large amount of traffic. In large networks, a multilayer switch should be used. Redundancy should also be considered at this layer since an outage of these devices could affect thousands of users. Devices should have redundant links to edge layer devices, and redundant power supplies should be used.

The access layer , or edge layer , includes hubs and switches and focuses on connecting client devices to the network. This layer is responsible for clients receiving data on their computers and phones. Any device that connects users to the network is an access layer device. Figure 1-13 displays the architecture of the hierarchical internetwork model developed by Cisco.

Software-Defined Networking Overview

Now that you understand the fundamental building blocks of the network, we can start discussing topics related to deploying and supporting networks. Two models for supporting a network are manual per-device configuration and software-defined networking (SDN). Software-defined networking has become a big buzz phase in recent years, but what does it mean? There is not a simple single answer. There are different types of software-defined networking. We cover different types of software-defined networking in relevant chapters throughout this book. For now, we just want to introduce you to the concepts and explain why software-defined networking is so important.

An oversimplified definition of software-defined networking is using software external to the hardware to control network flows. Over the next few chapters, we will discuss networking concepts and show you how to configure routers and switches using the command line interface. The command line interface configures one device at a time. That is the way we have been managing networks for decades, and most organizations still use this method for a majority of network configuration. An issue with manually configuring each device is it can be error prone and tedious to roll out a change to every device in a large network. With software-defined networks, you can make a change in one interface and have the software make the change on all the hardware devices. Changes could be planned infrastructure changes or reactions to security risk or to the discovery of flow errors. Doesn’t that seem much easier than manually configuring everything?

Software-Defined Network Control Models

There are a few common SDN control models. Two models we want to emphasize are the centralized control plane and the distributed control plane.

Throughout this book, you will learn about routing protocols, overlays, and underlays. In a traditional network, you configure all of these directly on the routers and switches, and the protocols interact with peers to create network flows. Distributed control plane models still use these protocols locally on the hardware to make flow decisions. The difference is that the configuration of the protocols is pushed using centralized software. This model allows you to take advantage of SDN benefits with traditional network hardware. In many cases, it will intermix with hardware that is not controlled by centralized software. This model is the most common in Cisco networks, and most of the SDN examples in this book will use this model.

The centralized control plane model takes all decisions away from the hardware. This model can provide more efficient flows because a centralized server knows about everything. If it is more efficient, why don’t we use it everywhere? One answer is that it isn’t supported by every type of device. Another answer is that to work properly, it needs to be in total control. A few examples where we sometimes see this are with some software-defined WAN (SD-WAN) solutions and with some data center solutions. The centralized control planes in these examples provide optimal utilization of expensive links that you couldn’t realize in distributed control plane environments.

Summary

The chapter has finally come to an end, and you are on your way to becoming a network engineer. We have covered many fundamental concepts and will continue to build upon this information in the upcoming chapters. We began this chapter by discussing the OSI model and how all the layers work together, as each layer has its responsibilities and functions to perform. We discussed each layer in detail, and you should have an understanding of all seven.

We also discussed TCP/IP as the most widely used protocol on the Internet today. You should understand how sessions are started and torn down to include the three-way handshake. We provided illustrations and Wireshark packet captures to allow you to actually see the packets transmitted. You should be familiar with commonly used port numbers and how they are used to transport data.

Lastly, we covered different types of networks, including LAN, CAN, MAN, WAN, and WWAN. Also, we introduced you to the hierarchical network model that is in use in most networks today. The three layers are the core, distribution, and access layers. We are now going to move forward to discuss the physical layer in the next chapter to build on the foundational information from this chapter.