CHAPTER 7

The Incident Response Process

In this chapter you will learn:

• The stakeholders during incident response

• Containment techniques

• Eradication techniques

• Response validation

• Corrective actions

• The purpose of communications processes

I am prepared for the worst, but hope for the best.

—Benjamin Disraeli

A Cast of Characters

Before we dive into the myriad technical issues to consider as part of incident response, we should start at the same topic with which we will wrap up this chapter: people. In the midst of incident responses, it is all too easy to get so focused on the technical challenges that we forget the human element, which is arguably at least as important. We focus our discussion on the various roles involved and the manner in which we must ensure these roles are communicating effectively with each other and with those outside the organization.

Key Roles

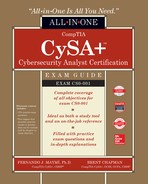

Broadly speaking, the key roles required in incident responses can be determined beforehand based on established escalation thresholds. The in-house technical team will always be involved, of course, but when and how are others brought in? This depends on the analysis that your organization performed as part of developing the incident response (IR) plan. Figure 7-1 shows a typical escalation model followed by most organizations.

Figure 7-1 Typical role escalation model

The technical team is unlikely to involve management in routine responses such as when an e-mail with a malicious link or attachment somehow gets to a user’s inbox but is not clicked on. You still have to respond to this and will probably notify others (for example, the user, supervisor, and threat intelligence team) of the attempt, but management will not be “in the loop” at every step of the response. The situation is different when the incident or response has a direct impact on the business, such as when you have to reboot a production server in order to eradicate malware on it. Management needs to be closely involved in decision-making in this scenario. At some point, the skills and abilities of the in-house team will probably be insufficient to effectively deal with an incident, which is when the response is escalated and you bring in contractors to augment your team or even take over aspects of the response. Obviously, this is an expensive move, so you want to carefully consider when to do this, and management will almost certainly be involved in that decision. Finally, there are incidents that require government involvement. Typically, though not always, this comes in the form of notifying and perhaps bringing in a law enforcement agency such as the FBI or Secret Service. This may happen with or without your organization calling in external contractors, but will always involve senior leadership. Let’s take a look at some of the issues involved with each of the roles in this model.

Technical Staff

The composition of the technical team that responds to an incident is usually going to depend on the incident itself. Some responses will involve a single analyst, while others may involve dozens of technical personnel from many different departments. Clearly, there is no one-size-fits-all team, so we need to pull in the right people to deal with the right problem. The part of this that should be prescribed ahead of time is the manner in which we assemble the team and, most importantly, who is calling the shots during the various stages of incident response. If you don’t build this into your plan, and then periodically test it, you will likely lose precious hours (or even days) in the food fight that will likely ensue during a major incident.

A best practice is to leverage your risk management plan to identify likely threats to your systems. Then, for every threat (or at least the major ones), you can “wargame” the response to a handful of ways in which it might become manifest. At each major decision point in the process, you should ask the question, who decides? Whatever the answer is, the next question should be, does that person have the required authority? If the person does, you just check it off and move to the next one. If the authority is lacking, you have to decide whether someone else should make the decision or whether that authority should be delegated in writing to the first person you came up with. Either way, you don’t want to be in the midst of an IR only to find you have to sit on your hands for a few hours while the decision is vetted up and down the corporate chain.

Contractors

No matter how skilled or well-resourced an internal technical team is, there may come a point when you have to bring in hired guns. Very few organizations, for example, are capable of responding to incidents involving nation-state offensive operators. Calling in the cavalry, however, requires a significant degree of prior coordination and communication. Apart from the obvious service contract with the incident response firm, you have to plan and test exactly how they would come into your facility, what they would have access to, who would be watching and supporting them, and what (if any) parts of your system are off-limits to them. These companies are very experienced in doing this sort of thing and can usually provide a step-by-step guide as well as templates for nondisclosure agreements (NDA) and contracts. What they cannot do for you is to train your staff (technical or otherwise) on how to deal with them once they descend upon your networks. This is where rehearsals and tests come in handy: in communicating to every stakeholder in your organization what a contractor response would look like and what their roles would be.

It is possible to go too far in embedding these IR contractors. Some organizations outsource all IR as a perceived cost-saving measure. The rationale is that you’d pay only for what you need because, let’s face it, qualified personnel are hard to find, slow to develop in-house, and expensive. The truth of the matter, however, is that this approach is fundamentally flawed in at least two ways. The first is that incident response is inextricably linked with critical business processes whose nuances are difficult for third parties to grasp. This is why you will always need at least one qualified, hands-on incident responder who is part of the organization and can at least translate technical actions into business impacts. The second reason is that IR can be at least as much about interpersonal communications and trust as it is about technical controls. External parties will have a much more difficult time dealing with the many individuals involved. One way or another, you are better off having some internal IR capability and augmenting it to a lesser or greater degree with external contractors.

Management

Incident response almost always has some level of direct impact (sometimes catastrophic) on an organization’s business processes. For this reason, the IR team should include key senior leaders from every affected business unit. Their involvement is more than just to provide support, but to shape the response process to minimize disruptions, address regulatory issues, and provide an interface into the affected personnel in their units as well as to higher-level leaders within the organization. Effective incident response efforts almost always have the direct and active involvement of management as part of a multidisciplinary response team.

Integrating these business leaders into the team is not a trivial effort. Even if they are as knowledgeable and passionate about cybersecurity as you are (which is exceptionally rare in the wild), their priorities will oftentimes be at odds with yours. Consider a compromise of a server that is responsible for interfacing with your internal accounting systems as well as your external payment processing gateway. You know that every second you keep that box on the network you risk further compromises or massive exfiltration of customer data. Still, every second that box is off the network will cause the company significantly in terms of lost sales and revenue. If you approach the appropriate business managers for the first time when you are faced with this situation, things will not go well for anybody. If, on the other hand, there is a process in place with which they’re both familiar and supportive, then the outcome will be better, faster, and less risky.

Law Enforcement

A number of incidents will require you to involve a law enforcement agency (LEA). Sometimes, the laws that establish these requirements also have very specific timelines, lest you incur civil or even criminal penalties. In other cases, there may not be a requirement to involve an LEA, but it may be a very good idea to do so all the same. The scenario we just described involving the payment processor is just one example of a situation in which you probably want to involve an LEA. If you (or the rest of your team) don’t know which incidents fall into these two categories of required or recommended reporting, you may want to put that pretty high on your priority list for conversations to be had with your leadership and legal counsel.

When an LEA is involved, they will bring their own perspective on the response process. Whereas you are focused on mitigation and recovery, and management is keen on business continuity, law enforcement will be driven by the need to preserve evidence (which should be, but is not always, an element of your IR plan anyway). These three sets of goals can be at odds with each other, particularly if you don’t have a thorough, realistic, and rehearsed plan in place. If your first meeting with representatives from an LEA occurs during an actual incident response, you will likely struggle with it more than you would if you rehearse this part of the plan.

Stakeholders

The term stakeholder is broad and could include a very large set of people. For the purposes of the CySA+ exam, what we call IR stakeholders are those individuals and teams who are part of your organization and have a role in helping with some aspects of some incident response. They each have a critical role to play in some (maybe even most) but not all responses. This presents a challenge for the IR team because the supporting stakeholders will not normally be as accustomed to executing response operations as the direct players are. Extra efforts must be taken to ensure they know what to do and how to do it when bad things happen.

Human Resources

The likeliest involvement of human resources (HR) staff in a response is when the team determines that a member of the organization probably had a role in the incident. The role need not be malicious, mind you, because it could be a failure to comply with policies (for example, connecting a thumb drive into a computer when that is not allowed) or repeated failures to apply security awareness training (for example, clicking a link in an e-mail even after a few rounds of remedial training). Malicious, careless, or otherwise, the actions of our teammates can and do lead to serious incidents. Disciplinary action in those cases all but requires HR involvement.

There are other situations in which you may need a human resources employee as part of the response, such as when overtime is required for the response, or when key people need to be called in from time off or vacation. The safe bet is to involve HR in your IR planning process and especially in your drills, and let them tell you what, if any, involvement they should have in the various scenarios.

Legal

Whenever an incident response escalates to the point of involving government agencies such as law enforcement, you will almost certainly be coordinating with legal counsel. Apart from reporting criminal or state-sponsored attacks on your systems, there are regulatory considerations such as those we discussed in Chapter 5. For instance, if you work in an organization covered by HIPAA and you are responding to an incident that compromised the protected health information (PHI) of 500 or more people, your organization will have some very specific reporting requirements that will have to be reviewed by your legal and/or compliance team(s).

The law is a remarkably complicated field, so even actions that would seem innocuous to many of us may have some onerous legal implications. Though some lawyers are very knowledgeable in complex technological and cybersecurity issues, most have only a cursory familiarity with them. In our experience, starting a dialogue early with the legal team and then maintaining a regular, ongoing conversation are critical to staying out of career-ending trouble.

Marketing

Managing communications with your customers and investors is critical to successfully recovering from an incident. What, when, and how you say things is of strategic importance, so you’re better off leaving it to the professionals who, most likely, reside in your marketing department. If your organization has a dedicated strategic communications, public relations, media, or public affairs team, it should also be involved in the response process.

Like every other aspect of IR, planning and practice are the keys to success. When it comes to the marketing team, however, this may be truer than with most others. The reason is that these individuals, who are probably only vaguely aware of the intricate technical details of a compromise and incident response, will be the public face of the incident to a much broader community. Their main goal is to mitigate the damage to the trust that customers and investors have in the organization. To do this, they need to have just the right amount of technical information and present it in a manner that is approachable to broad audiences and can be dissected into effective sound bites (or tweets). For this, they will rely heavily on those members of the technical team who are able to translate techno-speak into something the average person can understand.

Management

We already mentioned management when we discussed the roles of incident response. We return to this group now to address its involvement in incident response for managers who are not directly participating in it. This can happen in a variety of ways, but consider the members of senior management in your organization. They are unlikely to be involved in any but the most serious of incidents, but you still need their buy-in and support to ensure you get the right resources from other business areas. Keeping them informed in situations in which you may need their support is a balancing act; you don’t want to take too much of their time (or bring them into an active role), but you need to have enough awareness so all it takes is a short call for help and they’ll make things happen.

Another way in which members of management are stakeholders for incident response is not so much in what they do, but in what they don’t do. Consider an incident that takes priority over some routine upgrades you were supposed to do for one of your business units. If that unit’s leadership is not aware of what IR is in general, or of the importance of the ongoing response in particular, it could create unnecessary distractions at a time when you can least afford them. Effective communications with leadership can build trust and provide you a buffer in times of need.

Response Techniques

Although we commonly use the terms interchangeably, there are subtle differences between an event, which is any occurrence that can be observed, verified, and documented, and an incident, which is one or more related events that compromise the organization’s security posture. Incident response is the process of negating the effects of an incident on an information system.

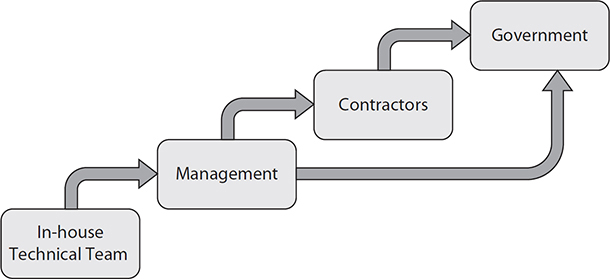

There are many incident response models, but all share some basic characteristics. They all require us to take some preparatory actions before anything bad happens, to identify and analyze the event in order to determine the appropriate counter-actions, to correct the problem(s), and finally to keep this incident from happening again. Clearly, efforts to prevent future occurrences tie back to our preparatory actions, which creates a cycle. Figure 7-2 shows the entire process, which is described in NIST Special Publication 800-61 (Revision 2). In this chapter, we focus on correcting the problems caused by an incident. We’ll assume that someone has already detected and analyzed the incident for us, and we take it from there.

Figure 7-2 The incident response lifecycle

Containment

Once you know that a threat agent has compromised the security of your information system, your first order of business is to keep things from getting worse. Containment is a set of actions that attempts to deny the threat agent the ability or means to cause further damage. The goal is to prevent or reduce the spread of this incident while you strive to eradicate it. This is akin to confining highly contagious patients in an isolation room of a hospital until they can be cured to keep others from getting infected. A proper containment process buys the incident response team time for a proper investigation and determination of the incident’s root cause. The containment should be based on the category of the attack (that is, whether it was internal or external), the assets affected by the incident, and the criticality of those assets. Containment approaches can be proactive or reactive. Which is best depends on the environment and the category of the attack. In some cases, the best action might be to disconnect the affected system from the network. However, this reactive approach could cause a denial of service or limit functionality of critical systems.

Segmentation

A well-designed security architecture (we get to this in Part IV of this book) will segment our information systems by some set of criteria such as function (for example, finance or HR) or sensitivity (for example, unclassified or secret). Segmentation is the breaking apart of a network into subnetworks (or segments) so that hosts in different segments are not able to directly communicate with each other. This can be done by either physically wiring separate networks or by logically assigning devices to separate virtual local area networks (VLANs). In either case, traffic between network segments must go through some sort of gateway device, which is oftentimes a router with the appropriate access control lists (ACLs). For example, the accounting division may have its own VLAN that prevents users in the research and development (R&D) division from directly accessing the financial data servers. If certain R&D users had legitimate needs for such access, they would have to be added to the gateway device’s ACL, which could place restrictions based on source/destination addresses, time of day, or even specific applications and data to be accessed.

The advantages of network segmentation during incident response should be pretty obvious: compromises can be constrained to the network segment in which they started. To be clear, it is still possible to go from one segment to another, like in the case in the R&D users example. Some VLANs may also have vulnerabilities that could allow an attacker to jump from one to another without going through the gateway. Still, segmentation provides an important layer of defense that can help contain an incident. Without it, the resulting “flat” network will make it more difficult to contain an incident.

Isolation

Although it is certainly helpful to segment the network as part of its architectural design, we already saw that this can still allow an attacker to easily move between hosts on the same subnet. As part of your preparations for IR, it is helpful to establish an isolation VLAN, much like hospitals prepare isolation rooms before any patients actually need them. The IR team would then have the ability to quickly move any compromised or suspicious hosts to this VLAN until they can be further analyzed. The isolation VLAN would have no connectivity to the rest of the network, which would prevent the spread of any malware. This isolation would also prevent compromised hosts from communicating with external hosts such as command-and-control (C2) nodes. About the only downside to using isolation VLANs is that some advanced malware can detect this situation and then take steps to eradicate itself from the infected hosts. Although this may sound wonderful from an IR perspective, it does hinder our ability to understand what happened and how the compromise was executed so that we can keep it from happening in the future.

While a host is in isolation, the response team is able to safely observe its behaviors to gain information about the nature of the incident. By monitoring its network traffic, we can discover external hosts (for example, C2 nodes and tool repositories) that may be part of the compromise. This allows us to contact other organizations and get their help in shutting down whatever infrastructure the attackers are using. We can also monitor the compromised host’s running processes and file system to see where the malware resides and what it is trying to do on the live system. This all allows us to better understand the incident and how to best eradicate it. It also allows us to create indicators of compromise (IOCs) that we can then share with others such as the Computer Emergency Readiness Team (CERT) or an Information Sharing and Analysis Center (ISAC).

Removal

At some point in the response process, you may have to remove compromised hosts from the network altogether. This can happen after isolation or immediately upon noticing the compromise, depending on the situation. Isolation is ideal if you have the means to study the behaviors and gain actionable intelligence, or if you’re overwhelmed by a large number of potentially compromised hosts that need to be triaged. Still, one way or another, some of the compromised hosts will come off the network permanently.

When you remove a host from the network, you need to decide whether you will keep it powered on, shut it down and preserve it, or simply rebuild it. Ideally, the criteria for making this decision is already spelled out in the IR plan. Here are some of the factors to consider in this situation:

• Threat intelligence value A compromised computer can be a treasure trove of information about the tactics, techniques, procedures (TTPs), and tools of an adversary—particularly a sophisticated or unique one. If you have a threat intelligence capability in your organization and can gain new or valuable information from a compromised host, you may want to keep it running until its analysis is completed.

• Crime scene evidence Almost every intentional compromise of a computer system is a criminal act in many countries, including the U.S. Even if you don’t plan to pursue a criminal or civil case against the perpetrators, it is possible that future IR activities change your mind and would benefit from the evidentiary value of a removed host. If you have the resources, it may be worth your effort to make forensic images of the primary storage (for example, RAM) before you shut it down and of secondary storage (for example, the file system) before or after you power it off.

• Ability to restore It is not a happy moment for anybody in our line of work when we discover that, though we did everything by the book, we removed and disposed of a compromised computer that had critical business information that was not replicated or backed up anywhere else. If we took and retained a forensic image of the drive, then we could mitigate this risk, but otherwise, someone is going to have a bad day. This is yet another reason why you should, to the extent that your resources allow, keep as much of a removed host as possible.

The removal process should be well documented in the IR plan so that the right issues are considered by the right people at the right time. We address chain-of-custody and related issues in Chapter 9, but for now suffice it so say that what you do with a removed computer can come back and haunt you if you don’t do it properly.

Reverse Engineering

Though not technically a containment technique, reverse engineering (RE) can help contain an incident if the information gleaned from it helps identify other compromised hosts. Reverse engineering is the detailed examination of a product to learn what it does and how it works. In the context of incident response, RE relates exclusively to malware. The idea is to analyze the binary code to find, for example, the IP addresses or host/domain names it uses for C2 or the techniques it employs to achieve permanence in an infected host, or to identify a unique characteristic that could be used as a signature for the malware.

Generally speaking, there are two approaches to reverse engineering malware. The first doesn’t really care about what the binary is, but rather with what the binary does. This approach, sometimes called dynamic analysis, requires a sandbox in which to execute the malware. This sandbox creates an environment that looks like a real operating system to the malware and provides such things as access to a file system, network interface, memory, and anything else the malware asks for. Each request is carefully documented to establish a timeline of behavior that allows us to understand what it does. The main advantage of dynamic malware analysis is that it tends to be significantly faster and require less expertise than the alternative (described next). It can be particularly helpful for code that has been heavily obfuscated by its authors. The biggest disadvantage is that it doesn’t reveal all that the malware does, but rather simply all that it did during its execution in the sandbox. Some malware will actually check to see if it is being run in a sandbox before doing anything interesting. Additionally, some malware doesn’t immediately do anything nefarious, waiting instead for a certain condition to be met (for example, a time bomb that only activates at a particular date and time).

The alternative to dynamic code analysis is, unsurprisingly, static code analysis. In this approach to malware RE, a highly skilled analyst will either disassemble or decompile the binary code to translate its ones and zeroes into either assembly language or whichever higher-level language it was created in. This allows a reverse engineer to see all possible functions of the malware, not just the ones that it exhibited during a limited run in a sandbox. It is then possible, for example, to see all the domains the malware would reach out to given the right conditions, as well as the various ways in which it would permanently insert itself into its host. This last insight allows the incident response team to look for evidence that any of the other persistence mechanisms exist in other hosts that were not considered infected up to that point.

Eradication

Once the incident is contained, we turn our attention to the eradication process, in which we return all systems to a known-good state. It is important to gather evidence before we recover systems because in many cases we won’t know that we need legally admissible evidence until days, weeks, or even months after an incident. It pays, then, to treat each incident as if it will eventually end up in a court of justice.

Once all relevant evidence is captured, we fix all that was broken. The aim is to restore full, trustworthy functionality to the organization. For hosts that were compromised, the best practice is to simply reinstall the system from a gold master image and then restore data from the most recent backup that occurred prior to the attack.

Sanitization

According to NIST Special Publication 800-88 Revision 1 (Guidelines for Media Sanitization), sanitization refers to the process by which access to data on a given medium is made infeasible for a given level of effort. These levels of effort, in the context of incident response, can be cursory and sophisticated. What we call cursory sanitization can be accomplished by simply reformatting a drive. It may be sufficient against run-of-the-mill attackers who look for large groups of easy victims and don’t put too much effort into digging their hooks deeply into any one victim. On the other hand, there are sophisticated attackers who may have deliberately targeted your organization and will go to great lengths to persist in your systems or, if repelled, compromise them again. This class of threat actor requires more advanced approaches to sanitization.

The challenge, of course, is that you don’t always know which kind of attacker is responsible for the incident. For this reason, simply reformatting a drive is a risky approach. Instead, we recommend one of the following techniques, listed in increasing level of effectiveness at ensuring the adversary is definitely removed from the medium:

• Overwriting Overwriting data entails replacing the ones and zeroes that represent it on storage media with random or fixed patterns of ones and zeroes in order to render the original data unrecoverable. This should be done at least once (for example, overwriting the medium with ones, zeroes, or a pattern of these), but may have to be done more than that.

• Encryption Many mobile devices take this approach to quickly and securely render data unusable. The premise is that the data is stored on the medium in encrypted format using a strong key. In order to render the data unrecoverable, all the system needs to do is to securely delete the encryption key, which is many times faster than deleting the encrypted data. Recovering the data in this scenario is typically computationally infeasible.

• Degaussing This is the process of removing or reducing the magnetic field patterns on conventional disk drives or tapes. In essence, a powerful magnetic force is applied to the media, which results in the wiping of the data and sometimes the destruction of the motors that drive the platters. Note that degaussing typically renders the drive unusable.

• Physical destruction Perhaps the best way to combat data remanence is to simply destroy the physical media. The two most commonly used approaches to destroying media are to shred them or expose them to caustic or corrosive chemicals. Another approach is incineration.

Reconstruction

Once a compromised host’s media is sanitized, the next step is to rebuild the host to its pristine state. The best approach to doing this is to ensure you have created known-good, hardened images of the various standard configurations for hosts on your network. These images are sometimes called gold masters and facilitate the process of rebuilding a compromised host. This reconstruction is significantly harder if you have to manually reinstall the operating system, configure it so it is hardened, and then install the various applications and/or services that were in the original host. We don’t know anybody who, having gone through this dreadful process once, doesn’t invest the time to build and maintain gold images thereafter.

Another aspect of reconstruction is the restoration of data to the host. Again, there is one best practice here, which is to ensure you have up-to-date backups of the system data files. This is also key for quickly and inexpensively dealing with ransomware incidents. Sadly, in too many organizations, backups are the responsibility of individual users. If your organization does not enforce centrally managed backups of all systems, then your only other hope is to ensure that data is maintained in a managed data store such as a file server.

Secure Disposal

When you’re disposing of media or devices as a result of an incident response, any of the four techniques covered earlier (overwriting, encryption, degaussing, or physical destruction) may work, depending on the device. Overwriting is usually feasible only with regard to hard disk drives and might not be available on some solid-state drives. Encryption-based purging can be found in multiple workstation, server, and mobile operating systems, but not in all. Degaussing only works on magnetic media, but some of the most advanced magnetic drives use stronger fields to store data and may render older degaussers inadequate. Note that we have not mentioned network devices such as switches and routers, which typically don’t offer any of these alternatives. In the end, the only way to securely dispose of these devices is by physically destroying them using an accredited process or service provider. This physical destruction involves the shredding, pulverizing, disintegration, or incineration of the device. Although this may seem extreme, it is sometimes the only secure alternative left.

Validation

The validation process in an incident response is focused on ensuring that we have identified the corresponding attack vectors and implemented effective countermeasures against them. This stage presumes that we have analyzed the incident and verified the manner in which it was conducted. This analysis can be a separate post-mortem activity or can take place in parallel with the response.

Patching

Many of the most damaging incidents are the result of an unpatched software flaw. This vulnerability can exist for a variety of reasons, including failure to update a known vulnerability or the existence of a heretofore unknown vulnerability, also known as a “zero day.” As part of the incident response, the team must determine which cause is the case. The first would indicate an internal failure to keep patches updated, whereas the second would all but require notification to the vendor of the product that was exploited so a patch can be developed.

Many organizations rely on endpoint protection that is not centrally managed, particularly in a “bring your own device” (BYOD) environment. This makes it possible that a user or device fails to download and install an available patch, and this causes an incident. If this is the case in your organization, and you are unable to change the policy to required centralized patching, then you should also assume that some number of endpoints will fail to be patched and you should develop compensatory controls elsewhere in your security architecture. For example, by implementing Network Access Control (NAC), you can test any device attempting to connect to the network for patching, updates, anti-malware, and any other policies you want to enforce. If the endpoint fails any of the checks, it is placed in a quarantine network that may allow Internet access (particularly for downloading patches) but keeps the device from joining the organizational network and potentially spreading malware.

If, on the other hand, your organization uses centralized patches and updates, the vulnerability was known, and still it was successfully exploited, this points to a failure within whatever system or processes you are using for patching. Part of the response would then be to identify the failure, correct it, and then validate that the fix is effective at preventing a repeated incident in the future.

Permissions

There are two principal reasons for validating permissions before you wrap up your IR activities. The first is that inappropriately elevated permissions may have been a cause of the incident in the first place. It is not uncommon for organizations to allow excessive privileges for their users. One of the most common reasons we’ve heard is that if the users don’t have administrative privileges on their devices, they won’t be able to install whatever applications they’d like to try out in the name of improving their efficiency. Of course, we know better, but this may still be an organizational culture issue that is beyond your power to change. Still, documenting the incidents (and their severity) that are the direct result of excessive privileges may, over time, move the needle in the direction of common sense.

Not all permissions issues can be blamed on the end users. We’ve seen time and again system or domain admins who do all their work (including surfing the Web) on their admin account. Furthermore, most of us have heard of (or had to deal with) the discovery that a system admin who left the organization months or even years ago still has a valid account. The aftermath of an incident response provides a great opportunity to double-check on issues like these.

Finally, it is very common for interactive attackers to create or hijack administrative accounts so that they can do their nefarious deeds undetected. Although it may be odd to see an anonymous user in Russia accessing sensitive resources on your network, you probably wouldn’t get too suspicious if you saw one of your fellow admin staff members moving those files around. If there is any evidence that the incident leveraged an administrative account, it would be a good idea to delete that account and, if necessary, issue a new one to the victimized administrator. While you’re at it, you may want to validate that all other accounts are needed and protected.

Scanning

By definition, every incident occurs because a threat actor exploits a vulnerability and compromises the security of an information system. It stands to reason, then, that after recovering from an incident you would want to scan your systems for other instances of that same (or a related) vulnerability. Although it is true that we will never be able to protect against every vulnerability, it is also true that we have a responsibility to mitigate those that have been successfully exploited, whether or not we thought they posed a high risk before the incident. The reason is that we now know that the probability of a threat actor exploiting it is 100 percent because it already happened. And if it happened once, it is likelier to happen again absent a change in your controls. The inescapable conclusion is that after an incident you need to implement a control that will prevent a recurrence of the exploitation, and develop a plug-in for your favorite scanner that will test all systems for any residual vulnerabilities.

Monitoring

So you have successfully responded to the incident, implemented new controls, and ran updated vulnerability scans to ensure everything is on the up and up. These are all important preventive measures, but you still need to ensure you improve your ability to react to a return by the same (or a similar) actor. Armed with all the information on the adversary’s TTPs, you now need to update your monitoring plan to better detect similar attacks.

We already mentioned the creation of IOCs as part of isolation efforts in the containment phase of the response. Now you can leverage those IOCs by incorporating them into your network monitoring plan. Most organizations would add these indicators to rules in their intrusion detection or prevention system (IDS/IPS). You can also cast a wider net by providing the IOCs to business partners or even competitors in your sector. This is where organizations such as the US-CERT and the ISACs can be helpful in keeping large groups of organizations protected against known attacks.

Corrective Actions

No effective business process would be complete without some sort of introspection or opportunity to learn from and adapt to our experiences. This is the role of the corrective actions phase of an incident response. It is here that we apply the lessons learned and information gained from the process in order to improve our posture in the future.

Lessons-Learned Report

In our time in the Army, it was virtually unheard of to conduct any sort of operation (training or real world), or run any event of any size, without having a hotwash (a quick huddle immediately after the event to discuss the good, the bad, and the ugly) and/or an after action review (AAR) to document issues and recommendations formally. It has been very heartening to see the same diligence in most non-governmental organizations in the aftermath of incidents. Although there is no single best way to capture lessons learned, we’ll present one that has served us well in a variety of situations and sectors.

The general approach is that every participant in the operation is encouraged or required to provide his observations in the following format:

• Issue A brief (usually single-sentenced) label for an important (from the participant’s perspective) issue that arose during the operation.

• Discussion A (usually paragraph-long) description of what was observed and why it is important to remember or learn from it for the future.

• Recommendation Usually starts with a “sustain” or “improve” label if the contributor felt the team’s response was effective or ineffective (respectively).

Every participant’s input is collected and organized before the AAR. Usually all inputs are discussed during the review session, but occasionally the facilitator will choose to disregard some if he feels they are repetitive (of others’ inputs) or would be detrimental to the session. As the issues are discussed, they are refined and updated with other team members’ inputs. At the conclusion of the AAR, the group (or the person in charge) decides which issues deserve to be captured as lessons learned, and those find their way into a final report. Depending on your organization, these lessons-learned reports may be sent to management, kept locally, and/or sent to a higher-echelon clearinghouse.

Change Control Process

During the lessons learned or after action review process, the team will discuss and document important recommendations for changes. Although these changes may make perfect sense to the IR team, we must be careful about assuming that they should automatically be made. Every organization should have some sort of change control process. Oftentimes, this mechanism takes the form of a change control board (CCB), which consists of representatives of the various business units as well as other relevant stakeholders. Whether or not there is a board, the process is designed to ensure that no significant changes are made to any critical systems without careful consideration by all who might be affected.

Going back to an earlier example about an incident that was triggered by a BYOD policy in which every user could control software patching on their own devices, it is possible that the incident response team will determine that this is an unacceptable state of affairs and recommend that all devices on the network be centrally managed. This decision makes perfect sense from an information security perspective, but would probably face some challenges in the legal and human resources departments. The change control process is the appropriate way to consider all perspectives and arrive at sensible and effective changes to the systems.

Updates to Response Plan

Regardless of whether the change control process implements any of the recommendations from the IR team, the response plan should be reviewed and, if appropriate, updated. Whereas the change control process implements organization-wide changes, the response team has much more control over the response plan. Absent sweeping changes, some compensation can happen at the IR team level.

As shown in earlier Figure 7-2, incident management is a process. In the aftermath of an event, we take actions that allow us to better prepare for future incidents, which starts the process all over again. Any changes to this lifecycle should be considered from the perspectives of the stakeholders with which we started this chapter. This will ensure that the IR team is making changes that make sense in the broader organizational context. In order to get these stakeholders’ perspectives, establishing and maintaining positive communications is paramount.

Summary Report

The post-incident report can be a very short one-pager or a lengthy treatise; it all depends on the severity and impact of the incident. Whatever the case, we must consider who will read the report and what interests and concerns will shape the manner in which they interpret it. Before we even begin to write it, we should consider one question: what is the purpose of this report? If the goal is to ensure the IR team remembers some of the technical details of the response that worked (or didn’t), then we may want to write it in a way that persuades future responders to consider these lessons. This writing would be very different than if our goal was to persuade senior management to modify a popular BYOD policy to enhance our security even if some are unhappy as a result. In the first case, the report would likely be technologically focused, whereas in the latter case it would focus on the business’s bottom line.

Communication Processes

We know return to the topic with which we started this chapter: the variety of team members and stakeholders involved in incident responses and the importance of maintaining effective communications among all. This is true of the internal stakeholders we already mentioned, but it is equally true of external communications. You may have a textbook-perfect response to an incident that ends up endangering your entire organization simply because of ineffective communication processes.

Internal Communications

One of the key parts of any incident response plan is the process by which the trusted internal parties will be kept abreast of and consulted about the response to an incident. It is not uncommon, at least for the more significant incidents, to designate a war room in which the key decision-makers and stakeholders will meet to get periodic updates and make decisions. In between these meetings, the room serves as a clearinghouse for information about the response activities. This means that at least one knowledgeable member of the IR team will be stationed there for the duration of the response in order to address these drop-ins. It is ideal when the war room is a physical space, but a virtual one might work as well, depending on your organization.

Apart from meetings (formal or otherwise) in the war room, it may be necessary to establish a secure communications channel with which to keep key personnel up to date on the progress of the response. This could be a group text, e-mail, or chat room, but it must include all the key personnel who might have a role or stake in the issue. When it comes to internal communications, there is no such thing as too much information.

External Communications

Communications outside of the organization, on the other hand, must be carefully controlled. Sensible reports have a way of getting turned into misleading and potentially damaging sound bites, so it is best to designate a trained professional for the role of handling external communications. Some of these, after all, may be regimented by regulatory or statutory requirements.

The first and most important sector for external communications is made up of government entities. Whether it’s the Securities Exchange Commission or the FBI or some other government entity, if there is a requirement to communicate with them in the course of an incident response, then the legal team must be part of the crafting of any and all messages. This is one area that few organizations get to mess up and emerge unscathed. This is not to say that the government stakeholders are adversarial, but that when the process is regulated by laws or regulations, the stakes are much higher.

Next on the list of importance are customers. Though there may be some regulatory requirements with regard to compromised customer data, our focus here is on keeping the public informed so that it perceives transparency and trustworthiness from the organization. This is particularly important when the situation is interesting enough to make headlines or go viral on social media. Just as the lawyers were critical to government communications, the media relations (or equivalent) team will carry the day when it comes to communicating with the masses. The goal here is to assuage fears and concerns as well as to control the narrative to keep it factually correct. To this end, press releases and social media posts should be templated even before the event so that all that is needed is to fill in some blanks before an effective communiqué can be quickly pushed out.

Still another group with which we may have to communicate deliberately and effectively is the key partners, such as business collaborators, select shareholders, and investors. The goal of this communications thrust is to convey the impact on the business’s bottom line. If the event risks driving down the price of the company’s stock, then the conversation has to include ways in which the company will mitigate such losses. If the event could spread to the systems of partner organizations, then the focus should be on how to mitigate that risk. In any event, the business leaders should carry on these conversations, albeit with substantial support from the senior response team leaders.

We cannot be exhaustive in our treatment of how to communicate during incident responses in this chapter, but we hope to have conveyed the preeminence of the interpersonal and interorganizational communications in these few pages. Even the best-handled technical incident response can be overshadowed very quickly by an inability to communicate effectively, both internally and externally.

Chapter Review

This chapter sets the stage for the rest of our discussion on incident responses. It started and ended with a focus on the interpersonal element of IR. Even before we discussed the technical process itself, we discussed the various roles and stakeholders that you, as a team member, must be tracking and with whom you must develop an effective rapport before an incident has even occurred—and you must maintain this relationship during and after response activities. Many an incident has turned into an RGE (resume generating event) for highly skilled responders who did not understand the importance of the various characters in the play.

The technical part, by comparison, is a lot more straightforward. The incident recovery and post-incident response process consists of five discrete phases: containment, eradication, validation, corrective actions, and final reporting. Your effectiveness in this process is largely dictated by the amount of preparation you and your teammates put into it. If you have a good grasp on the risks facing your organization, develop a sensible plan, and rehearse it with all the key players periodically, you will likely do very well when your adversaries breach your defenses. In the next few chapters, we get into the details of the key areas of technical response.

Questions

1. When decisions are made that involve significant funding requests or reaching out to law enforcement organizations, which of the following parties will be notified?

A. Contractors

B. Public relations staff

C. Senior leaders

D. Technical staff

2. The process of dissecting a sample of malicious software to determine its purpose is referred to as what?

A. Segmentation

B. Frequency analysis

C. Traffic analysis

D. Reverse engineering

3. When would you consult your legal department in the conduct of an incident response?

A. Immediately after the discovery of the incident

B. When business processes are at risk because of a failed recovery operation

C. In cases of compromise of sensitive information such as PHI

D. In the case of a loss of more than 1 terabyte of data

4. During the IR process, when is a good time to perform a vulnerability scan to determine the effectiveness of corrective actions?

A. Change control process

B. Reverse engineering

C. Removal

D. Validation

5. What is the term for members of your organization who have a role in helping with some aspects of some incident response?

A. Shareholders

B. Stakeholders

C. Insiders

D. Public relations

6. What process during an IR is as important in terms of expectation management and reporting as the application of technical controls?

A. Management process

B. Change control process

C. Communications process

D. Monitoring process

Refer to the following scenario for Questions 7-12:

You receive an alert about a compromised device on your network. Users are reporting that they are receiving strange messages in their inboxes and having problems sending e-mails. Your technical team reports unusual network traffic from the mail server. The team has analyzed the associated logs and confirmed that a mail server has been infected with malware.

7. You immediately remove the server from the network and route all traffic to a backup server. What stage are you currently operating in?

A. Preparation

B. Containment

C. Eradication

D. Validation

8. Now that the device is no longer on the production network, you want to restore services. Before you rebuild the original server to a known-good condition, you want to preserve the current condition of the server for later inspection. What is the first step you want to take?

A. Format the hard drive.

B. Reinstall the latest operating systems and patches.

C. Make a forensic image of all connected media.

D. Update the antivirus definitions on the server and save all configurations.

9. What is the most appropriate course of action regarding communication with organizational leadership?

A. Provide updates on progress and estimated time of service restoration.

B. Forward the full technical details on the affected server(s).

C. Provide details until after law enforcement is notified.

D. Provide details only if unable to restore services.

10. Your team has identified the strain of malware that took advantage of a bug in your mail server version to gain elevated privileges. Because you cannot be sure what else was affected on that server, what is your best course of action?

A. Immediately update the mail server software.

B. Reimage the server’s hard drive.

C. Write additional firewall rules to allow only e-mail-related traffic to reach the server.

D. Submit a request for next-generation antivirus for the mail server.

11. Your team believes it has eradicated the malware from the primary server. You attempt to bring affected systems back into the production environment in a responsible manner. Which of the following tasks will not be a part of this phase?

A. Applying the latest patches to server software

B. Monitoring network traffic on the server for signs of compromise

C. Determining the best time to phase in the primary server into operations

D. Using a newer operating system with different server software

12. Your team has successfully restored services on the original server and verified that it is free from malware. What activity should be performed as soon as practical?

A. Preparing the lessons-learned report

B. Notifying law enforcement to press charges

C. Notifying industry partners about the incident

D. Notifying the press about the incident

Answers

1. C. Decisions to reach out to external law enforcement bodies or employ changes that will incur significant cost will likely require organizational leadership involvement. They will provide guidance to company priorities, assist in addressing regulatory issues, and provide the support necessary to get through the IR process.

2. D. Reverse engineering malware is the process of decomposing malware to understand what it does and how it works.

3. C. There are regulatory reporting requirements when dealing with compromises of sensitive data such as protected health information. Since these can lead to civil penalties or even criminal charges, it is important to consult legal counsel.

4. D. Additional scanning should be performed during validation to ensure that no additional vulnerabilities exist after remediation.

5. B. Stakeholders are those individuals and teams who are part of your organization and have a role in helping with some aspects of some incident response.

6. C. The communications process is a vital part of the IR process and will allow for an efficient recovery from an incident.

7. B. Containment is the set of actions that attempts to deny the threat agent the ability or means to cause further damage.

8. C. Since unauthorized access of computer systems is a criminal act in many areas, it may be useful to take a snapshot of the device in its current state using forensic tools to preserve evidence.

9. A. Organizational leadership should be given enough information to provide guidance and support. Management needs to be closely involved in critical decision-making points.

10. B. Generally, the most effective means of disposing of an infected system is a complete reimaging of a system’s storage to ensure that any malicious content was removed and to prevent reinfection.

11. D. The goal of the IR process is to get services back to normal operation as quickly and safely as possible. Introducing completely new and untested software may introduce significant challenges to this goal.

12. A. Preparing the lessons-learned report is a vital stage in the process after recovery. It should be performed as soon as possible after the incident to record as much information and complete any documentation that might be useful for the prosecution of the incident and to prevent future incidents from occurring.