5

Investors’ Problems and Protection

CHAPTER OUTLINE

- Introduction

- Relationship Between Investor Protection and Corporate Governance

- Corporate Governance Through Legal Protection of Investors

- Investor Protection in India

- SEBI’s Poor Performance—Suggestions for Improvement

Introduction

Strong investor protection is associated with effective corporate governance. In fact, corporate governance has been advocated by everyone interested in the long term shareholder value, which in turn promotes orderly development of industries and economies. When an investor places his hard-earned money in the securities of a corporation, he does so with certain expectations of its performance, the corporate benefits that may accrue to him, and above all, the prospects of income from, and the possibilities of capital growth of the securities he holds in the firm. At the same time, while he makes an investment decision the investor would have obviously taken note of and evaluated the attendant risks that go with such expectations, especially the possibility of the risk that the income and/or capital growth may not materialise. This mismatch between the expectations of the investors and the unexpected final outcome in terms of income and/or capital growth arises mainly because their hard earned money is entrusted to managers in a corporation whose investment decisions, apart from carrying certain risks of their own, may not match those of the investors.

Strong investor protection is associated with effective corporate governance. When an investor places his hard-earned money in the securities of a corporation, he does so with certain expectations of its performance, the corporate benefits that may accrue to him, and above all, the prospects of income from and the possibilities of capital growth of the securities he holds in the firm. A mismatch occurs when the expectations of the investors and the unexpected final outcome in terms of income and/or capital in a corporation whose investment decisions, apart from carrying certain risks of their own, may not match those of the investors.

Why is Investor Protection Needed?

An appropriate definition of investor protection is very much needed to relate it to corporate governance and to establish the correlation between these two. As stated earlier, when investors finance companies, they take a risk that could land them in a situation in which the returns on their investments would not be forthcoming because the managers or those whom they appointed to represent them on the board may keep them or expropriate them either covertly or overtly. This kind of betrayal of the investors by the “insiders” as the managers or board of directors of the company may shake their confidence, which in the long run would have a deleterious impact on the overall investment climate with serious repercussions on the economic development of the country. The economic parameters of a nation such as output, employment, income, expenditure, and above all, overall economic growth will be badly jeopardised due to declining investment. Therefore, there is a very strong reason to maintain the investors’ morale, protect their interests and restore their confidence as and when there is a tendency for investors to lose confidence in the system or when their investments are at stake. Research findings also reveal that when the law and its agencies fail to protect investors, corporate governance and external finance do not fare well. If there is no investor protection, the insiders can easily steal the firm’s profits, while when it is good, they will find it very difficult to do it.

Definition of Investor Protection

Investors by virtue of their investments in securities of corporations obtain certain rights and powers that are expected to be protected by the state which gave the charter or legal entity to the corporate bodies or the regulators designated by the state to do so. Their basic rights include disclosure and accounting rules that will enable them to obtain proper, precise and accurate information to exercise other rights such as approval of executive decisions on substantial sale or investments, voting out incompetent or otherwise ineligible directors and appointment of auditors. There are also laws that mainly deal with bankruptcy and reorganisation procedures that outline measures and procedures to enable creditors repossess collateral to protect their seniority and make it difficult for firms to seek court protection in reorganisation. In many countries, laws and legal regulations are enforced in part by different law enforcing agencies such as market regulators, i.e. SEBI, courts or government agencies, i.e. the Department of Corporate Affairs in India and markets themselves. If the investors’ rights are effectively enforced by one or all of these agencies, “It would force insiders to repay creditors and distribute profits to shareholders and thereby protect external financing mechanism from breaking down”.1 Thus, investor protection can be defined as both (i) the extent of the laws that protect investors’ rights and (ii) the strength of the legal institutions that facilitate law enforcement.

Relationship Between Investor Protection and Corporate Governance

Recent research confirms that an essential feature of good corporate governance is strong investor protection.2 According to Rafael La Porta et al (1999) “corporate governance to a large extent is a set of mechanisms through which outside investors protect themselves against expropriation by the insiders”. Expropriation is possible because of the agency problems that are inherent in the formation and structure of corporations. Shareholders or investors of a firm are numerous and scattered and therefore cannot manage it. Hence, they entrust the management of the firm to managers who include the board of directors and senior executives such as the CEO and the CFO. However, managerial actions depart from those required to maximise shareholder returns. Such mismatch of objectives results in the agency problem. Investors do realise and accept to a certain level of self-interested behaviours in managers while they delegate responsibilities to them. But when such self-indulgence by managers exceed reasonable limits, principles of corporate governance comes in to check such abuses and malpractices. The core substance of corporate governance lies in designing and putting in place, mechanisms such as disclosures, monitoring, oversight and corrective systems that we can align with the objectives of the two sets of players (investors and managers) as closely as possible and minimise the agency problems.

The core substance of corporate governance lies in designing and putting in place mechanisms such as disclosures, monitoring, oversight and corrective systems so that we can align the objectives of the two sets of players (investors and managers) as closely as possible and minimise agency problems.

How do Insiders Steal Investors’ Funds?

The insiders, both managers and controlling shareholders, can expropriate the investors in a variety of ways. Rafael La Porta et al (cited above) describe several means by which the insiders siphon off the investor’s funds. “In some countries, the insiders of the firm simply steal the earnings. In some other countries, the arrangements they go through to divert the profits are more elaborate. Sometimes, the insiders sell the output or the assets of the firm they control, but which outside investors have financed, to another entity they own at below market prices. Such transfer pricing and asset stripping have largely the same effect as theft. In still other instances, expropriation takes the form of installing possibly under-qualified family members in managerial positions, or excessive executive pay.” In all these instances, it is clear that the insiders use the profits of the firm to benefit themselves (either as excessive executive salaries or in the form unjustifiable perquisites), instead of returning the money to outside investors to whom it legitimately belongs. In this context, minority shareholders and creditors are far more vulnerable. Expropriation also is done by insider selling additional securities in the firm they control to another firm or subsidiaries they own at below market prices, with assistance from obliging interlocking directorates, and also by diverting corporate opportunities to subsidiaries and so on. Such practices, though often legal, have the same effect as theft. However, it must be stressed that these sharp practices of insiders vary from country to country depending on the existence or non-existence of democratic and corporate values, maturity or otherwise of the securities market, financial systems, pace of new security issues, corporate ownership structures, dividend policies, efficiency of investment allocation, the legal system and the competence of the securities market regulator.

The insiders, both managers and controlling shareholders, can expropriate the investors in a variety of ways. Insiders use profits of the firm to benefit themselves, instead of returning the money to outside investors to whom it rightly belongs. Expropriation is also done by insiders selling additional securities in the firm they control to another firm or subsidiaries they own at ‘below-market’ rices, with assistance from obliging interlocking directorates, and also by diverting corporate opportunities to subsidiaries.

Rights to Information and Other Rights

Investor protection is not attainable without adequate and reliable corporate information. All outside investors, whether they are shareholders or investors, have an inalienable right to have certain corporate information. In fact, several other rights provided to them under the law cannot be exercised by shareholders unless companies in which they have invested in, share with them such information. For instance, “without accounting data, a creditor cannot know whether a debt covenant had been violated. In the absence of these rights, the insider does not have to repay the creditors or to distribute profits to shareholders”. Apart from the rights to information, creditors have also certain other rights, and these are to be protected. Minority shareholders have the same rights as majority shareholders in dividend policies and in accessing new security issues. The significant but non-controlling shareholders need the right to have their votes counted and respected. This is the reason why SEBI-appointed Kumar Mangalam Birla committee recommended postal ballot for the benefit of those who could not attend the AGMs held by corporations in cities where their corporate offices are located. The committee recommended that in case of shareholders, who are unable to attend the meeting, there should be a requirement, which would enable them to vote by postal ballot on important key issues such as corporate restructuring, sale of assets, new issues on preferential allotment and matters relating to change in management. Likewise, even the large creditors such as institutional investors who are powerful enough by virtue of their large stakes and need relatively few formal rights, should be able to “seize and liquidate collateral, or to reorganise the firm”. Investors would be unable to protect their turfs even if they have a large number or chunk of the share, if they are not able to enforce their rights.

Investor protection is not attainable without adequate and reliable corporate information. Several other rights provided to them under the law cannot be exercised by shareholders unless companies in which they have invested in share with them such information. Minority shareholders have the same rights as majority shareholders in dividend policies and in accessing new security issues.

There are, however, rules and regulations that are designed to protect investors. Some of the important regulations are with regard to disclosure and accounting standards, which provide investors with the information they need to exercise other rights of investors such as the “ability to receive dividends on pro-rata terms, to vote for directors, to participate in shareholders’ meeting, to subscribe to new issues of securities on the same terms as the insiders, to sue directors for suspected wrongdoing including expropriation, to call extraordinary shareholders meeting etc. Laws protecting creditors largely deal with bankruptcy procedures and include measures which enable creditors to repossess collateral, protect their seniority and make it harder for firms to seek court protection in reorganisation. In different jurisdictions, rules protecting investors come differently from various sources, including company, security, bankruptcy, takeover and competition laws but also stock exchange regulations and accounting standards’. In India, for instance, rules protecting investors emanate from the Department of Corporate Affairs of the Ministry of Finance, the Securities and Exchange Board of India, the Listing Agreements of Stock Exchanges, Accounting Standards of the Institute of Chartered Accountants of India, and sometimes decisions of the superior courts of the country. It should be stressed though that the enforcement of laws by these agencies are as crucial as their content and in most emerging economies these are lax, delayed and dilatory, resulting in poor corporate governance.

Corporate Governance Through Legal Protection of Investors

The objective of corporate governance reforms in most countries including several Latin American and Asian countries is to protect the rights of outside investors, including both shareholders and creditors. These reforms have a focus on expanding financial markets to facilitate external financing of new firms to infuse large foreign investments in existing firms, promote external commercial borrowings to help local firms access foreign capital by listing themselves in stock markets overseas, move away from concentrated ownerships, expose native firms to foreign competition wholesome corporate developments elsewhere and also to improve the efficiency of investment allocation.

The objective of corporate governance reforms in most countries is to protect the rights of outside investors, including both shareholders and creditors. Laws and their enforcement are the major factors that help outsiders to invest in corporate firms. Investor protection is an important constituent of corporate governance.

The importance of legal rules and regulations as a means to protect outside investors against insider expropriation of their money is in sharp contrast to the traditional “laws and economies” perspective and has evolved over the past 50 years. In the words of Rafael La Porta et al: “According to this perspective, most regulations of financial markets are unnecessary since financial contracts take place between sophisticated issuers and equally sophisticated investors. On an average, investors recognise that there is a risk of expropriation and penalise firms that fail to contractually disclose information about them and to contractually bind themselves to treat investors well. Because entrepreneurs bear these costs when they issue securities, they have an incentive to bind themselves through contract with investors to limit expropriation (Jensen and Meckling 1976). As long as these contracts are enforced, financial markets do not require regulation.” While this line of argument is an over-simplification of the process, management that gives room for expropriation that takes place in firms and neglects the grey areas that exist in company administration, this perspective too relies on courts to enforce contracts, when disputes arise.

A case in point is Russia which has a good securities law, a good bankruptcy law and an equally good company law in books. Its Securities and Exchange Commission too is independent and aggressive but relatively has few enforcement powers. With an ineffective judiciary, weak enforcement of law, Russia’s financial market has not grown in an environment where blatant violations of the law are far too common.

So, in reality, laws and their enforcement are the major factors that help outsiders to invest in corporate firms. Although the reputation and goodwill of a firm do help it raise funds, law and its enforcement are the clinching factors to decide on investment. It is an indisputable fact that to a large extent shareholders and creditors decide to invest in firms because their rights are protected by the law. The outside investors are more vulnerable to expropriation, and therefore, more dependent on law, than their employees or the suppliers, who are useful to them and also have reliable source of information to ward off any problems and are at a lesser risk of being mistreated. Besides, available evidence also suggests that in countries where there is poor investor protection there may be a need to change many more rules simultaneously to bring them up to best corporate governance practice. But this may not be easy as families controlling corporations may object to these reforms. Therefore, law and its enforcement are important means to protect investors and would help promote corporate governance.

Impact of Investor Protection on Ownership and Control of Firms

In many countries, firms are owned and controlled by promoter families and in such closely held firms, insiders use every opportunity to abuse the rights of other shareholders and steal their profits through devious means. In such cases where there is poor investor protection, large scale expropriation is feasible. Control through ownership acquires enormous value because it gives such owners opportunities to expropriate effectively. Entrepreneurs who promote companies would not like to lose control and thereby give up the chances of expropriation by diffusing control rights when investor protection is poor. Promoter families in countries with poor investor protection would wish to have concentrated control of the enterprises they have floated. However, expropriation can be limited considerably in these family owned firms, by dissipating control among several large investors none of whom can control the decision of the firm without agreeing with others. But then this is a situation well entrenched, closely held firms’ promoters would wish to avoid. The evidence from a number of individual countries and the seven OECD countries with poor investor protection shows more concentrated control of firms than countries with good investor protection. In the East, except Japan where there is a fairly good investor protection, there is a predominance of family control and family management of corporations. The evidence available in many countries is in consonance with the proposition that legal environment shapes the value of the private benefits of control and thereby determines the ownership structures.

Therefore, the available evidence on corporate ownership patterns around the world supports strongly the importance of investor protection. Evidence also shows that countries with poor investor protection have more concentrated control of firms than countries with good investor protection.

Studies made by various researchers testify to the fact that in countries where there is a concentration of ownership in the hands of few families, there may be stiff opposition to legal reforms that are likely to reduce their control over firms and promote investor protection. Rafael La Porta et al assert: “From the point of view of these families, an improvement of outside investors’ first and foremost right is reduction in the value of control as expropriation opportunities deteriorate. The total value of firms may increase as a result of legal reform, as expropriation declines and investors finance new projects on more attractive terms. Still, the first order effect on the insiders is a massive redistribution of wealth from them to outside investors. No wonder, then that in all countries from Latin America to Asia to Western and Eastern Europe, the families are opposed to legal reform.” According to these authors, there is also another reason why the insiders in such firms are opposed to reforms and the expansion of capital markets. Under the existing conditions, these firms can finance their own investment projects internally or through captive banks or subsidiary financial institutions. Studies show that a large chunk of credit goes to the few largest firms in countries with poor investor protection. This was also the case in India as R. K. Hazari and his researchers of the University of Bombay found out in early 60s. Even recently as late as in 2001, it was found that there has been a rapid expansion of assets and turnover of industrial houses owned by families and there is a massive concentration at the top. The assets of Ambanis of Reliance, the Munjals of the Hero group, Shiv Nadar of HCL Technologies, Tatas, Birlas, Jindals, R. P Goenka, Azim Premji of Wipro, TVS, Chidambaram and Murugappa groups have grown tremendously, mostly due to insider domination and poor investor protection in the country. As a consequence of this fertile situation, the large firms obtain not only the finance they need but also political clout that comes with the access to such finance in a corruption-ridden society, as well as the security from competition of smaller firms that require external capital. Thus poor corporate governance provides large family owned firms not only secure finance but also easy access to politics and markets. The dominant families have thus abiding interest in keeping the status quo lest the reforms take away their privileges and confer outside investors’ protection.

The Impact of Investor Protection on the Development of Financial Markets

Investor protection provides an impetus for the growth of capital markets. When investors are protected from the expropriation of insiders, they pay more for securities which makes it attractive for entrepreneurs to issue securities. Through investor protection, financial markets can develop with ease and perfection, which in turn can accelerate economic growth by (i) enhancing savings and capital formation, (ii) channelising these into real investment and (iii) improving the efficiency of capital allocation, since capital flows into more productive uses. Further financial development improves efficient resource allocation and through this investor protection brings about growth in productivity and output, the two basic ingredients needed to speed up economic development.

Investor protection provides an impetus for the growth of capital markets. When investors are protected from the expropriation of insiders, they pay more for securities which makes it attractive for entrepreneurs to issue securities. Research studies point out that countries with well-developed financial markets, regulated by laws, allocate investment across industries more in line with growth priorities.

Research studies point out that countries with well-developed financial markets regulated by laws, allocate investment across industries more in line with growth opportunities in these industries than countries with weak financial markets or poor regulatory mechanisms. These studies also reveal that (i) most developed financial markets are the ones that are protected by regulation and laws while unregulated markets do not work well, may be due to the fact they allow too much of expropriation of outside investors by corporate insiders (ii) improving the functioning of financial markets confers real benefits both in terms of overall economic growth and the allocation of resources across sectors (iii) one broad strategy of effective regulation and of encouragement of financial markets begins with protection of outside investors, whether they are shareholders or creditors and (iv) enforced outside shareholders’ rights, experience in many countries reveal, encourage the development of equity markets as measured by valuation of firms, the number of listed companies and the rate at which firms go for public issues.

However, investor protection does not necessarily mean rights just included in the laws and regulations alone, but the effectiveness with which they are enforced. In countries with poor investor protection, the insiders may treat outside investors fairly well as long as the firms’ future prospects are bright and they need the continued external financing by outsiders. But when the future prospects tend to deteriorate, insiders may step up expropriation. In such a scenario, unless there are effective laws against such malpractices and they are effectively enforced, outside investors will not be able to do anything but to withdraw their investments. Therefore, investor protection is absolutely essential for the orderly development and continued proper functioning of capital markets.

Banks and Corporate Governance

Banks play a significant role in the growth of the corporate sector by providing them finance for their operations. But, there is a difference in the roles they play in different countries and these diverse roles they play have different impacts, both on investor protection and its end result, corporate governance. There are considerable differences between bank-centred corporate governance systems such as those of Germany and Japan compared to market-centred systems such as those of the UK and the USA. In the former, the main bank provides both a significant share of finance and governance to firms while in the latter finance is provided by large numbers of investors and takeovers play a major governance role.

Banks play a significant role in the growth of the corporate sector by providing them finance for their operations. But, there are considerable differences between bank-centred corporate governance systems such as those of Germany and Japan compared to market-centred systems such as those of the UK and USA. In the former, the main bank provides both, a significant share of finance and governance to firms while in the latter finance is provided by large number of investors and takeovers play a major governance role.

But the classification of financial systems into bank centred and market centred is neither straight forward nor particularly useful. Rafael La Porta et al point out to studies that showed that in the 1980s when the Japanese economy was being touted as the best and worthy of emulation by other economies, such bank-centred governance was widely regarded as superior, since it enabled firms to make long term investment decisions, delivered capital to firms facing liquidity crisis and thereby avoiding costly financial distress, and above all, replaced the expensive disruptive takeover with more surgical bank intervention when the management of the borrowing firm under-performed. The rosy situation, however, did not last long enough. When the Japanese economy collapsed in the 1990s, this form of financing and governance was found faulty. Far from being the promoters of rational investment, Japanese banks were found to be the source of the soft budget constraint, over lending to loss making firms that required restructuring and resorting to collusion with managers to prevent external threats to their control and to collect rents on bank loans. Likewise, banks in Germany too were found to be wanting in providing good governance, especially in bad times.

In the ultimate analysis of the two systems, the market based system with its focus on legal protection of investors, seems to be doing better as was demonstrated time and again, the latest being its successful riding of the American stock market bubble of the 1990s.

In conclusion, it is to be stressed that strong investor protection is an inalienable part of effective corporate governance. Financial markets, very vital constituents of economic growth, need some protection of outside investors, whether by courts, market regulators, government agencies or market participants themselves through voluntary codes or guidelines. There have to be radical changes in the legal structure, the laws and their effective enforcement. With the integration of capital markets, the necessity to bring about these reforms is more pertinent today than it was in earlier times.

Investor Protection in India

Small investors are the backbone of the Indian capital market and yet a systematic study of their concerns and attempts to protect them has been relatively of recent origin. Due to lack of proper investor protection, the capital market in the country has experienced a stream of market irregularities and scandals in the 1990s. SEBI itself though formed with the primary objective of investor protection, took notice of the issue seriously only after the Ketan Parikh scam (2001) and the UTI crisis (1998 and 2001) and has developed sophisticated institutional mechanism and harnessed computer technology to serve the purpose. Yet, there are still continuing concerns about the speed and effectiveness with which fraudulent activities are detected and punished, which is after all, should be the major focus of the capital market reforms in the country.

Due to lack of proper investor protection, the capital market in the country has experienced a stream of market irregularities and scandals in the 1990s. SEBI itself took notice of the issue seriously only after the Ketan Parikh scam (2001) and the UTI crisis (1998 and 2001) and has developed sophisticated institutional mechanism and harnessed computer technology to serve the purpose.

The SEBI–NCAER study (1999) estimated that the investor population in India was 12.8 million or nearly 8 per cent of all Indian households. The bulk of the increase in the number of shareholders had taken place during the boom years 1990–1994 and tapered off thereafter. By 1997 the capital market bubble had burst. The Household Investors Survey of Society for capital Market Research and Development (SCMRD) (1997) revealed the following: (i) a majority of investors reported unsatisfactory experience of equity-investing (ii) 80 per cent of the investors said that they had little or no confidence in company managements (iii) 55 per cent respondents showed little or no confidence on the market regulator, SEBI and (iv) Most preferred saving instruments are government saving schemes and banks’ fixed deposits. This reflected a considerable erosion of investor confidence in securities and corporates. Many subsequent investor surveys also found broadly the same investor reactions.

All these surveys underlined the need for restoring the investor’s confidence in private corporates, which enjoy little credibility with investors who have badly burnt their fingers in a series of scams. This calls for a credible programme of corporate governance reform, focussing on outside minority shareholder protection. The situation does not seem to have changed much today notwithstanding the CII’s code and SEBI’s guidelines and is the reason why investors prefer government securities rather than corporate securities. The sooner this trend is reversed, the better it will be for the development of the capital market in the country.

The N. K. Mitra Committee on Invesotrs’ Protection

This committee chaired by N. K. Mitra submitted its report on investor protection, in April 2001, with the following recommendations:

- There is a need for a specific Act to protect investor interest. The Act should codify, amend and consolidate laws and practices for the purpose of protecting investors’ interest in corporate investment.

- Establishment of a judicial forum and award of compensation for aggrieved investors.

- Investor Education and Protection Fund which is under the Companies Act should be shifted to the SEBI Act and be administered by SEBI.

- SEBI should be the only capital market regulator, clothed with the powers of investigation.

- The regulator, SEBI, should require all IPO’s to be insured under third party insurance with differential premium based on the risk study by the insurance company.

- SEBI Act 1992 should be amended to provide for statutory standing committees on investors protection, market operation and standard setting.

- The Securities Contracts (Regulation) Act 1956 should be amended to provide for corporatisation and good governance of stock exchanges.

Problems of Investors in India

Investor protection is a broader term that covers various measures to protect the investors from malpractices of companies, brokers, merchant bankers, issue managers, registrar of new issues and so on. It is also incumbent on the investor to take necessary and appropriate precautions to protect their own interest, since all investments have some risk elements. But where they find that their interests are adversely impacted because of malpractice by companies, brokers or any other capital market intermediaries, they can seek redressal of their grievances from appropriate designated authorities. Most of the investor complaints can be divided into the following three broad categories:

- Against member–brokers of stock exchanges: Complaints of this category generally centre around the price, quantity etc. at which transactions are put through defective delivery, delayed payments or non-payments from brokers.

- Against companies listed for trading on stock exchanges: Complaints against companies generally centre around non-receipt of allotment letters, refund orders, non-receipts of dividends, interest etc.

- Complaints against financial intermediaries: These complaints can be against sub-brokers, agents, merchant bankers, issue managers etc. and generally centre around non-delivery of securities and non-settlement of payment due to investors. However, these complaints cannot be entertained by the stock exchanges, as per their rules.

Most of the investor complaints can be divided into the following three broad categories: Complaints against member-brokers of stock exchange; complaints against companies listed for trading on stock exchange; complaints financial intermediaries sub-brokers, agents, merchant bankers, issue managers etc. and generally centre around nondelivery of securities and non-settlement of payment due to investors.

Law Enforcement for Investor Protection

There are several agencies in India that are expected to protect investors. In fact, there are so many with overlapping functions that they cause confusion to the investors as to whom they should go for redressal of their grievances. The stated primary objective of the country’s sole capital market regulator, the Securities and Exchange Board of India, popularly known as SEBI, is protection of investors’ interests. But, investor protection is a multidimensional function, requiring checks at various levels, as shown below:

- Company level: Disclosure and Corporate Governance norms.

- Stock brokers level: Self-regulating organisation of brokers.

- Stock exchanges: Every stock exchange has to have a grievance redressal mechanism in place as well as an investor protection fund.

- Regulatory agencies:

- Investors’ Grievances and Guidance Division of SEBI

- Department of Corporate Affairs

- Department of Economic Affairs

- Reserve Bank of India

- Consumer Courts

- Courts of Law

Grievance Redressal Mechanisms

When an investor has a complaint and feels that his interest as an investor has not been protected, he should approach the company concerned, Mutual Fund or the Depository Participant as the case may be. If he is not satisfied with their response, the investor can approach SEBI. SEBI on its part, has instituted a Redressal Mechanism as detailed below in Table 5.1.

It is likely that there may be complaints that may be sometimes beyond the purview and jurisdiction of SEBI. There may be many problems arising due to corporate misgovernance. Table 5.1 provides a comprehensive mechanism of legal protection to investors.

TABLE 5.1. Redressal mechanism of SEBI

| Type | Nature of grievance | Can be taken up with |

|---|---|---|

| I | Issues related to non-receipt of refund order, allotment advice, cancelled stock invests, etc. | Investors’ Grievances and Guidance Division (IGG) |

| II | Non-receipt of dividend | Investors’ Grievances and Guidance Division (IGG) |

| III | Shares-related, i.e., non-receipt of share certificates | Investors’ Grievances and Guidance Division (IGG) |

| IV | Debentures related, i.e., non-receipt of debenture certificates, non-receipt of warrants | Investors’ Grievances and Guidance Division (IGG) |

| V | Non-receipt of letter offer of rights and interest on delayed payments of refund orders | Investors’ Grievances and Guidance Division (IGG) |

| VI | Complaints relating to collective investment scheme | Investors’ Grievances and Guidance Division (IGG) |

| VII | Complaints relating to MF’s | Mutual Funds Deptt., SEBI |

| VIII | Complaints relating to Dematerialisation or DP’s | Depositories and Custodian Cell, SEBI |

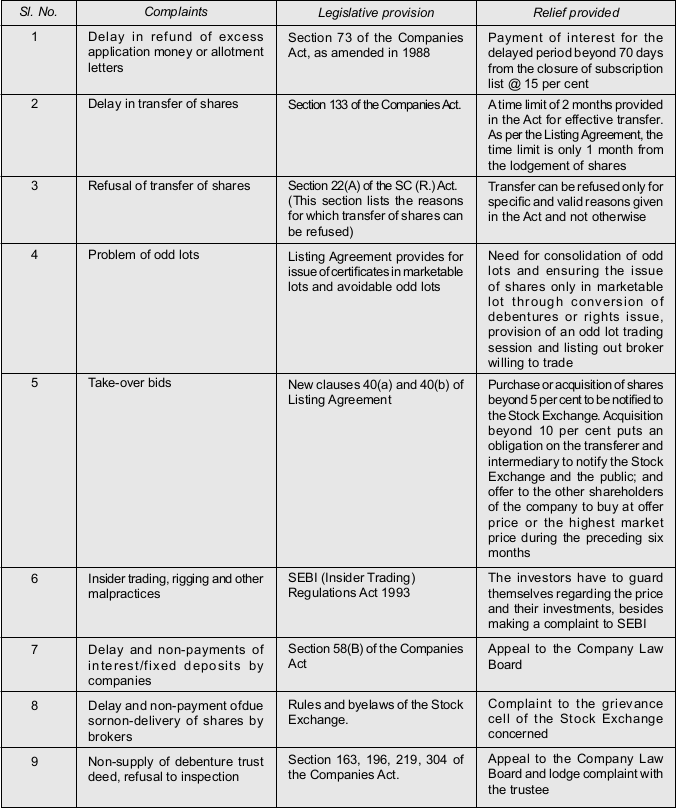

TABLE 5.2 Nature of complaints against companies under various Acts and relief provided

Source: Agarwal, Sanjiv A Manual of Indian Capital Markets, p. 198.

Lacunae in Investor Protection

Though there is a redressal mechanism in place in the country, investors could not get their complaints adequately addressed to, much less solved to their satisfaction by these public authorities. Multiplicity of authorities, overlapping functions, lack of knowledge and understanding by the common investor about these agencies and lack of enforcement have all acted against investor protection. Notwithstanding the existence of this seemingly comprehensive network of public institutions established for investor protection in India, a series of scams have taken place that has shaken the confidence of investors since 1991, the year of economic liberalisation.

Loss of investor confidence due to these scandals that conveyed an image of fraud and manipulation was so great that for several years stock market remained moribund.

To understand policy issues connected with the securities market, it is important to know how these scams burst out in the open due to misgovernance, greed, corruption, inefficiency and market manipulations.

Some Major Indian Scams

- Harshad Mehta scam (market manipulation), 1992: This first stock market scam was one which involved both the bond and equity markets in India. The manipulation was based on the inefficiencies on the settlement systems in GOI bond market transactions. A pricing bubble came about in equity market where the market index went up by 143 per cent between September 1991 and April 1992. The amount involved in the crisis was around Rs. 54 billion.

- MNCs efforts at consolidation of ownership, 1993: There were a number of reported cases when several transnational companies were found to consolidate their ownership by issuing equity allotments to their respective controlling groups at steep discounts to their market price. In this preferential allotment scam alone investors lost around Rs. 5,000 billion.

- Vanishing companies scam, 1993–94: Between July 1993 and September 1994, the stock market index zoomed by 120 percent. During this boom 3911 companies that raised over Rs. 25,0000 million vanished or did not set up projects as promised in their prospectuses. This scam occurred because during the artificial boom, hundreds of obscure companies were allowed to make public issues at large share premia through high sales pitch of questionable investment banks and grossly misleading prospectuses.

- M. S. Shoes (insider trading), 1994: The dominant shareholder of the firm, Pawan Sachdeva, took large leveraged positions through brokers at both the Delhi and Bombay Stock Exchanges to manipulate share prices prior to a rights issue. When the share prices crashed, the broker defaulted and BSE shut down for 3, days as a consequence. The amount involved in the default was about Rs. 170 million.

- Sesa Goa (price manipulation at BSE), 1995: This was caused by two brokers who later failed on their margin payments on leveraged positions in the shares. The exposure was around Rs. 45 million.

- Rupangi Impex and Magan Industries Ltd. (price manipulation), 1995: The dominant shareholders implemented a short squeeze. In both the cases, dominant shareholders were found to be guilty of price manipulation. Amount involved was Rs. 11 million in case of RIL and Rs. 5.8 million in case of MIL.

- Fraudulent delivery of physical certificates, 1995: When anonymous trading and nationwide settlement became the norm by the end of 1995, there was an increasing incidence of fraudulent shares being delivered into the market. It has been estimated that the expected cost of encountering fake certificates in equity settlement in India at the same time was as high as 1 per cent.

- Plantation companies scam, 1995–96: This scam saw Rs. 50,0000 million mopped up by unscrupulous and fly-by-night operators from gullible investors who believed plantation schemes would yield huge returns, being wiped out.

- Mutual funds scam, 1995–98: This scam saw public sector banks raising nearly Rs. 15,0000 million crore by promising huge returns, but all of them collapsed.

- CRB scam through market manipulation, 1997: C. R. Bhansali, a chartered accountant, created a group of companies, called the CRB Group, which was a conglomerate of finance and non-finance companies. Market manipulation was an important focus of the activities of the group. The non-finance companies routed funds to finance companies to manipulate prices. The finance companies would obtain funds from external sources using manipulated performance numbers. The CRB episode was particularly important in the way it exposed extreme failure of supervision on the part of RBI and SEBI. The amount involved in CRB scam was Rs. 7 billion.

- Market manipulation by Harshad Mehta, 1998: This was another market manipulation episode engineered by Harshad Mehta. He worked on manipulating the share prices of BPL, Videocon and Sterlite in collusion with their managements. The episode came to an end when the market crashed due to a major fall in index. Harshad Mehta did not have the liquidity to maintain his leveraged position. In this episode, the top management of the BSE resorted to tampering with the records in the trading system while trying to avert a payment crisis. The president, executive director and a vice-president of BSE had to resign due to this episode. This incident also highlighted the failure of supervision on the part of SEBI. The amount involved was of Rs. 0.77 billion.

- The IT scam, 1999–2000: During this 2 year period, millions of investors lost their entire investments duped by firms that changed their names to sound infotech. But when the unsustainable dotcom bubble burst, the hapless investors realised that their stocks were not even worth the paper in which they were printed.

- Price manipulation by Ketan Parikh, 2001: This scam, known as the Ketan Parekh scam, was triggered off by a fall in the prices of IT stocks globally. Ketan Parekh was seen to be the leader of this episode, with leveraged positions on a set of stocks called the K-10 stocks. There were allegations of fraud in this crisis with respect to an illegal badla market at the Calcutta Stock Exchange and banking fraud.

- Dramatic slide in the stock market, 2004: Between May 14 and 17 2004, there was a dramatic fall in the scrips of Reliance, Hindustan Lever, State Bank, Infosys and ONGC. On May 17, Sensex fell by 11.14 per cent. SEBI has found a dozen players whose names have not been divulged, were responsible for the price rigging and have been put on notice. Earlier on May 14 also, the stock market crumbled. On that day, the largest loser in sensex was the State Bank of India with a dip of 14.77 per cent. In all these falls, the market capitalisation worth millions of rupees was wiped out and consequently investors’ confidence was badly shaken.3 In the aftermath of its investigations, in May 2005, SEBI banned the Swiss investment firm USB Securities from issuing participatory notes and other off-shore derivative instruments for one year for not cooperating in the process of investigation by the market regulator.

- Satyam computer scam, 2009: Ramalinga Raju, founder of Satyam Computer Services Ltd, India’s fourth largest software exporter and the first Indian Internet company to be listed on the NASDAQ, confessed publicly to his involvement in major financial scandals. Raju was said to have falsified accounts, created fictitious assets, padded the company’s profits and cooked up the bank balances, all the time keeping his employees and the board of directors in the dark. The company, its shareholders and the public authorities were said to have been duped to an astronomical amount of not less than Rs. 40,000 billion.4

The series of scams has cast a shadow over the credibility of SEBI, and its capacity to create a safe and sound equity market.

SEBI’s Poor Performance—Suggestions for Improvement

The Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI), the designated capital market regulator, has a sort of mixed record in fostering and nurturing corporate governance in the Indian corporate sector. Since its inception in 1992, SEBI has registered substantial growth in its stature and reach. Presently, its regulatory framework is robust. It has also played a significant role in creating the country’s capital market infrastructure that is recognised as one of the better advanced in the world. If SEBI’s growth and reach over the past 5 years have been significant, its failure too has been spectacular. S. Vaidyanathan in his column “Eye on the Market” in the Hindu Businessline (20 February 2005) lists the following failures: 5

- Poor tackling of price manipulation and insider trading issues: Insider trading and price manipulation ahead of key corporate actions still continue to be rampant. SEBI has not effectively tackled—unlike its American counterpart SEC—issues such as price manipulation and insider trading. It has to strengthen enforcement and surveillance and impose deterrent penalties to stop these wrongdoings.

- Poor conviction rate: Aregulator’s credibility hinges on its ability to achieve a fairly high conviction rate against errant market players. SEBI’s record is poor as without exception the Securities and Appellate Tribunal has overturned its decisions and penal measures in cases against prominent market players. To achieve more convictions, a focus on building a case that passes the test of stringent scrutiny is very much necessary.

- Need to enhance its manpower skills: If SEBI is to make progress in its designated function, there has to be a vast improvement in the quality of its manpower skills at its disposal. Regulatory bodies always find it tough to move in lockstep with the market. It has to invest in developing skill-sets in areas such as finance, accounting, tax and law by attracting professionals of quality and integrity. This would mean making its compensation and working culture attractive.

- It should simplify and trim regulations: There is a need to simplify and trim the regulations, so that they are compact, easy to follow and comprehensible. A plethora of reports is filed by a variety of market participants, institutions and companies to comply with regulations. These should be placed in the public domain in a timely manner, so that analysts can record a history of trends in several areas. This would complement SEBI’s efforts and enhance its effectiveness as a regulator.

- It should tone up quality of disclosures: There is also a need to tone up the quality of disclosures in areas such as earnings, announcements, mergers/acquisitions and FII flows to make them more meaningful for investors. There is an urgent need to streamline SEBI’s website www.sebi.gov.in so as to make it a valuable source of information for investors.

- It should solve issues of IPOs and mutual funds: There are a host of other issues it has to tackle such as confusion over the clearance of IPOs in the Rs. 200 million range ensuring that SEBI files and maintains its own internal databases accurately and efficiently, and to formally shelve the move to convert the Association of Mutual Funds of India into a self-regulatory organisation, as the time for it has not come and such a move could lead to conflicts of interest with SEBI itself.

The foregoing analysis clearly shows that though SEBI has emerged as the one and only capital market regulator in the country, its functioning has been ineffective so far due to its failure to exercise its authority and bring to book the violators and the wrongdoers. It has also let itself to be influenced unduly and unjustifiably by some corporate big-wigs. Therefore, SEBI badly needs to improve administration and accountability and restore its credibility as a powerful regulator.6

An objective analysis of the problems faced by investors in countries like India, leading to an erosion of their confidence in the capital market with the attendant adverse impact on the economic growth shows that the major problems arise due to corporate misgovernance and not due to minor aberrations in following the procedures set by SEBI. To rectify such a situation, actions that lead to corporate misgovernance should be codified and small investors be provided statuary rights to enforce civil liability against the directors to recover the losses to the company and its shareholders due to their misdeeds and non-application of their minds in investment or other decisions that have adversely impacted the shareholders. Some of the misdeeds would include: (i) breach of fiduciary duty (ii) siphoning off corporate funds (iii) misappropriation of company’s funds (iv) price manipulation or insider trading (v) manipulation of accounts (vi) failure to disclose conflicts of interests (vii) fraud or cheating (viii) misappropriation of corporate assets (ix) losses caused due to mismanagement or negligence.

In this context, it is pertinent to note that already law courts have started imposing exemplary punishments to directors who violated codes and guidelines on corporate governance provided by competent authorities. In May 2004, Citigroup agreed for a $2.0 billion settlement, and more than a dozen other banks including J P Morgan Chase and Deutsche Bank are likely to fall in line. In January 2005, at the insistence of a US Court, former directors of WorldCom (now known as MCI) have agreed to pay $18 million out of their pockets as part of a shareholder law suit. Likewise, 18 former directors of the collapsed energy conglomerate Enron, agreed to pay $13 million as part of a settlement in another shareholder lawsuit. Though these settlements are subject to confirmation by the concerned US district courts, corporate governance experts had hailed these settlements for setting a new standard in accountability of directors when companies, they oversee go astray. In India too, as per the dictates of a lower court, recently the directors of a non-banking finance company have agreed to pay back to the company a large sum of money it lost, due to their indiscretion in an investment decision.

Another important protection to the investor would be by strengthening the enforceability of accounting standards in India, as has been done in the US through Sarbanes–Oxley Act. In India, though all the accounting standards have been made mandatory as a result of forceful pleas by various committees on corporate governance, they have not yet acquired the legal status in practice. This lack of legal sanction enables violators and wrongdoers go scot-free. Therefore, it is absolutely necessary if the investor is to be protected and corporate governance ensured for the larger benefit of the economy and nation, all the accounting standards should be legally enforced and exemplary punishments meted out to violators.

- Development of financial markets

- Grievance redressal mechanisms

- Impact of investor protection

- Lacunae

- Law enforcement

- Ownership and control of firms

- Rights to information

- What do you understand by investor protection? Why is it needed?

- Establish in your own words the relationship between investor protection and corporate governance.

- How can corporate governance be ensured through the adoption and guaranteeting of legal protection to investors?

- Comment on the means and measures available in India to ensure investor protection.

- Discuss critically the role of SEBI in ensuring investor protection in India.

- Explain some of the major investor-related scams in India and suggest measures to avoid such scams in future.

- Khanna, Sri Ram, “Financial Markets in India and Protection of Investors,” New Delhi: VOICE (Voluntary Organization in Interest of Consumer Education), New Century Publications.

- Neelamegam, R and R. Srinivasan (1998), “A study of Legal Aspects”, Investors’ Protection, Delhi: Raj Publications.

- Porta, Rafad La, Florencio Lopez De Silanes, Andrei Shleifer and Robert Vishney (Jun. 1999), Investor Protection and Corporate Governance, www.rru.worldbank.org.

- Parikh, Kirit S. and R. Radha Krishna (2004–05), “India Development”, New Delhi: Indira Gandhi Institute of Development. Research, Oxford Univesity Press.

- Fond, Mark L. De and Mingyi Hung, “Evidence from worldwide CEO Turnover”, Investor Protection and Corporate Governance, University of Sothern California: SSRN Resource, www.ssm.com.