16

SEBI: The Indian Capital Market Regulator

CHAPTER OUTLINE

- Introduction

- The Securities and Exchange Board of India

- SEBI’s Role in the New Era

- Phenomenol Growth of Indian Capital Market

- SEBI’s Role in Promoting Corporate Governance

- SEBI’s Shortcomings

- Role of Securities Market in Economic Growth

- SEBI’s Record of Performance

- Suggestions for SEBI’s Improvement

Introduction

Capital is a sine qua non for economic development. Without capital, land will be barren, labour idle and organisation rudderless. Capital enables the entrepreneur to bring together the other factors of production. It is necessary to build and develop infrastructure, buy and put in place plant and machinery, for use as working capital, and for setting up markets and so on. Capital grows out of savings of the community. Capital investment would lead to economic development only if channelised into productive activities. The securities market is the channel through which investible resources are routed to companies. The securities market converts a given stock of investible resources to a larger flow of goods and services. A well-organised and efficiently functioning securities market is conducive to sustained economic growth.

Capital is an essential input for economic development. Capital investment leads to economic growth, only if channelised into productive activities. The securities market is the channel through which investible resources are routed to companies, and enable them to produce goods and services. A well organised and efficient securities market is conducive to sustained economic growth.

Capital Market

Industry raises finance from the capital market with the help of a number of instruments. Broadly speaking, corporates have a choice of (i) equity finance and (ii) debt finance. Experience in different countries varies. Generally, equity-based capital is cheap and less cumbersome to manage and service. Substituting equity finance for debt finance makes domestic firms less vulnerable to fluctuations in earnings or increases in interest rates. During the last decade, more than a third of the increase in net assets of large firms in developing countries across the world, has been secured through equity issuance. This pattern contrasts sharply with that of the industrial countries, in which equity financing during the same period has accounted for less than 5% of the growth in net assets.

In the liberalised economic environment, the capital market plays a crucial role in the process of economic development. The capital market has to arrange funds to meet the financial needs of both public and private sector units, from domestic as well as foreign sources. What is more critical is that the changed environment is characterised by cut-throat competition. Ability of enterprises to mobilise funds at cheap cost will determine their competitiveness vis-à-vis their competitors in order to perform well in a highly competitive environment.

Phenomenal Growth of Indian Capital Market

At the time of independence, there were very few corporations in India. Notwithstanding the absence of a corporate culture in the post-independence era, there was an appreciable growth in the capital market especially after 1985. The Indian capital market by 1990 was one of the fastest growing markets in the world. The number of companies listed on the stock exchange, close to 6000, was the second highest after the US and by 1995 the number rose to 8593. Presently, there are more than 10,000 listed companies in the country’s 25 stock exchanges. Shareholding public is estimated at 20 million. Value of securities traded increased from $5 billion in 1985 to $21.9 billion in 1990, which was the fourth largest amongst the emerging markets of the world. Market capitalisation increased from $14.4 billion in 1985 to $38.6 billion in 1990, $65.1 billion in 1992, $80 billion in 1993 and exceeded $120 billion in 1998–99. Turnover ratio (total value traded as percentage of average market capitalisation) rose to 65.9. Resources raised from the capital market by the non-government public limited companies increased from Rs. 7,063.4 million (US $731 million) to Rs 52,668.0 million in 1982–83.

There was an appreciable growth in the capital market in the post-independence era, especially after 1985.The Indian capital market by 1990 was one of the fastest growing markets in the world. Indian corporations raised domestic debt and equity totalling $ 6.4 billion equivalent in 1994–95, $ 8.5 billion in 1996–97. Indian companies have also been raising substantial sums in the international capital markets-$ 4.7 billion in 1994–95, $ 2.3 billion in 1995–96 and $ 4.7 billion in 1996–97.

Indian corporations raised domestic debt and equity totalling $6.4 billion equivalent in 1994–95 and $8.5 billion in 1996–97. Indian companies have also been raising substantial sums in the international capital markets—$4.7 billion in 1994–95, $2.3 billion in 1995–96 and $4.7 billion in 1996–97. There has been a recent dramatic shift toward increased issuance of debt instruments. The equity-debt split was 97% 3% in 1994–95 by 1996–97, it was 23% to 77%.

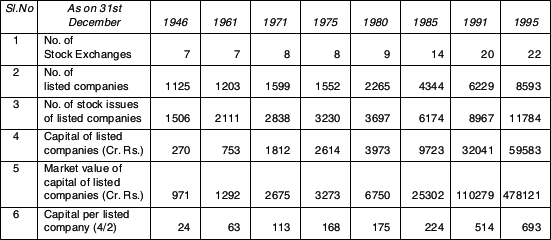

Figure 16.1 Growth Pattern of the Indian stock market

Note: Presently, there are 25 stock exchanges in the country.

Source: Various issues of Bombay stock exchange’s official directory.

Figure 16.1 portrays the overall growth pattern of Indian stock markets since independence. It is quite evident from the table that Indian stock markets have not only grown in number of exchanges, but also in number of listed companies and in capital of listed companies. The remarkable growth after 1985 can be clearly seen from the table, and this was due to the favourable government policies towards securities market.

However, the functioning of the stock exchanges in India suffered from many weaknesses such as long delays in transfer of shares, issue of allotment letters, and refund, lack of transparency in procedures and vulnerability to price rigging and insider trading. To counter these shortcomings and deficiencies and to regulate the capital market, the government of India set up the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) in 1988. Initially, SEBI was set up as a non-statutory body, but in January 1992 it was made a statutory body. SEBI was authorised to regulate all merchant banks on issue activity, lay guidelines, supervise and regulate the working of mutual funds and oversee the working of stock exchanges in India. SEBI, in consultation with the government, has taken a number of steps to introduce improved practices and greater transparency in the capital market in the interest of the investing public and the healthy development of the capital market.

Nature of the Indian Capital Market

The Indian capital market, like the money market, is known for its dichotomy. It consists of an organised sector and an unorganised sector. In the organised sector of the market, the demand for capital comes mostly from corporates, government and semi-government organisations. The supply comes from household savings, institutional investors such as banks, investment trusts, insurance companies, finance corporations, government and international financing agencies.

The unorganised sector of the capital market on the supply side consists mostly of indigenous bankers and moneylenders. While in the organised sector the demand for funds is mostly for productive investment, a large part of the demand for funds in the unorganised market is for consumption purpose. In fact, many purposes, for which funds are very difficult to get from the organised market, are financed by the unorganised sector. The unorganised capital market in India, like the unorganised money market, is characterised by the existence of multiplicity and exorbitant rates of interest, as well as lack of uniformity in their business transactions. On the other hand, the activities of the organised market are subject to a number of government controls, and of the market regulator, SEBI. Though efforts were initiated to bring the unorganised sector under some sort of regulatory framework or at least to bring in some discipline such as registration, these were not successful and this segment is by and large outside the effective government control.

The organised sector has been subjected to increasing insitutionalisation. The public sector financial institutions account for a large chunk of the business of this sector.

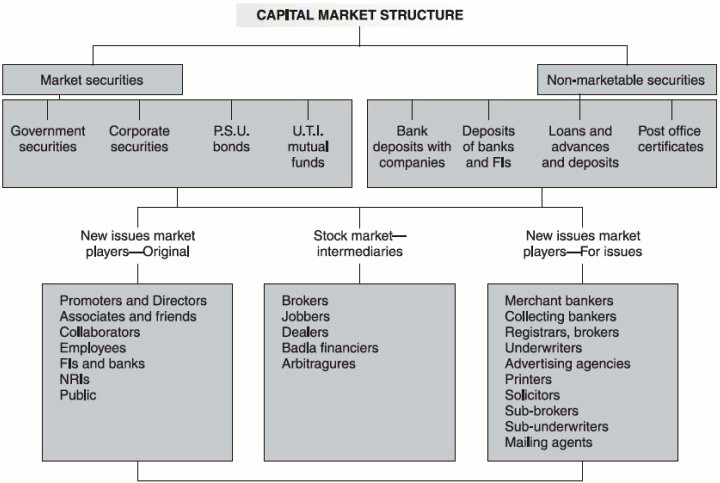

Figure 16.2 Capital market structure

Source: Figure adopted from V.A. Avadhani, Indian Capital Market, Himalaya Publishing House, Mumbai, 1997.

Development of the Indian Capital Market

The Indian capital market, as pointed out earlier, has undergone many significant changes since independence. The important factors that have contributed to the development of the Indian capital market are given below:

- Legislative measures: Laws such as the Companies Act, the Securities Contracts (Regulation) Act and the Capital Issues (Control) Act had empowered the government to regulate the activities of the capital market with a view to assuring healthy trends in the markets, protecting the interest of the investor, efficient utilisation of the resources, etc.

- Establishment of development banks and expansion of the public sector: Starting with the establishment of the Industrial Finance Corporation of India (IFCI), a number of development banks have been established at the national and regional levels to provide financial assistance to enterprises. These institutions today account for a large chunk of the industrial finance.

The expansion of the public sector in the money and capital markets has been accelerated by the nationalisation of the insurance business and the major part of the banking business. The Life Insurance was nationalised in 1956 and the General Insurance in 1972. The Reserve Bank in India was nationalised as early as 1949. The Imperial Bank, the then largest commercial bank in India, was nationalised and established as the State Bank of India in 1955. Fourteen major private commercial banks were nationalised in 1969. With the nationalisation of six more leading private banks in 1980, over 90% of the commercial banking business came to be concentrated in the government sector.

Thus, an important aspect of the Indian capital market is that a large part of the investible funds available in the organised sector is owned by the government. However, the new economic policy has changed the trend, and brought in the private sector in a large measure.

- Growth of underwriting business: There has been a phenomenal growth in the underwriting business, which was mainly due to the public financial corporations and the commercial banks. After the elimination of forward trading, brokers have begun to take on underwriting risks in the new issue market. In the last one decade the amount underwritten as percentage of total private capital issues offered to public varied between 72% and 97%.

- Public confidence: Impressive performance of certain large companies such as Reliance Industries, Tisco and Larsen & Toubro encouraged public investment in industrial securities. Booms and the consequent declaration of hefty dividends in the mid-80s boosted investor confidence.

- Increasing awareness of investment opportunities: The improvement in education and communication has created more public awareness about investment opportunities in the business sector. The market for industrial securities has become broader.

- Capital market reforms: A number of measures have been taken to check abuses and to promote healthy development of the capital market. The enactment of the Securities and Exchange Board of India Act, 1992 and the establishment of the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) as a capital market regulator are important milestones in the process of reforms in this sector.

Deficiencies in the Indian Capital Market

The Indian capital market suffers from the following deficiencies:

- Lack of diversity in the financial instruments

- Lack of control over the fair disclosure of financial information

- Poor growth in the secondary market

- Prevalence of insider trading and front running1

- Manipulation of security prices

- Existence of unofficial trade in the primary market, prior to the issue coming into the market

- Absence of proper control over brokers and sub-brokers

- Passive role of public financial institutions in checking malpractices

- High cost of transactions and intermediation, mainly due to the absence of well-defined norms for institutional investment.

The Indian capital market suffers from deficiencies like, lack of diversity in the financial instruments lack, of control over the fair disclosure of financial information, poor growth in the secondary market, prevalence of insider trading and front running.

In a planned economy, like the one we had prior to liberalisation, when the stock exchanges performed a residual role, these deficiencies did not matter much. On the other hand, in a market-driven economy towards which we are moving, capital market is expected to perform multifarious and facilitative functions, such as:

- Privatisation and a greater role for the private sector imply a large demand for equity finance

- Equity market should enable investors to diversify their wealth across a variety of assets

- Stock markets should perform a screening and monitoring role

- A financial system that functions well requires that the whole financial sector functions efficiently.

In view of its importance, the continuing shortcomings point to the inability of the market to function at a level that is expected.

Impact of Globalisation

With the gradual opening up of the Indian economy, increasing importance of foreign portfolio investment in the market and drastic reduction in import tariffs that has exposed Indian companies to foreign competition, Indian capital market is acquiring a global image. Till recently, participants in the Indian capital market could, to a large extent, afford to ignore what happened in other parts of the world. Share prices largely behaved as if the rest of the world just did not exist. However, now the that Indian capital market responds to all types of external developments, such as US bond yields, the value of the Euro or for that matter of any other currency, the political situation in the Gulf or new petrochem capacity in China.

In short, the Indian capital market is on the threshold of a new era. Gradual globalisation of the market will mean the following changes:

The Indian capital market is on the threshold of a new era. Gradual globalisation of the market will mean the market will be more sensitive to developments that take place abroad; there will be a power shift as domestic institutions are forced to compete with the Foreign Institutional Investors (FIIs) who control the floating stock and are also in control of the Global Depository Receipts (GDR) market.

- The market will be more sensitive to developments that take place abroad.

- There will be a power shift as domestic institutions are forced to compete with the Foreign Institutional Investors (FIIs) who control the floating stock and are also in control of the Global Depository Receipts (GDR) market.

- Structural issues will come to the fore with a plain message: “Either reform or despair.”

- The individual investor in his own interest will refrain from both primary and secondary market; he will be better off investing in mutual funds.

Role of Securities Market in Economic Growth

In the words of G.N. Bajpai, former SEBI Chairman: “It is the securities market which reflects the level of corporate governance of different companies and accordingly allocates resources to best governed companies. If the securities market is efficient, it can penalise the badly governed companies and reward the better-governed companies. Hence, not only the corporate governance standards need to improve, but also efficiency and efficacy of securities market need to improve so that the resources are directed to the deserving companies, which can really boost economic performance. The securities market cannot make best allocation of resources if the standards of corporate governance are not followed in letter and spirit.”

“A well functioning securities market is conducive to sustained economic growth. A number of studies, starting from World Bank and IMF to various scholars, have pronounced robust relationship not only one way, but also both the ways, between the development in the securities market and the economic growth. This happens, as market gets disciplined, developed, efficient and it avoids the allocation of scarce savings to low-yielding enterprises and forces the enterprises to focus on their performance which is being continuously evaluated through share prices in the market and which faces the threat of take over.”2

Though the classical economists led by Adam Smith believed that over time savings would be equal to investment, it does not seem to happen in actual practice. The reason is not far to seek. The savers are different from investors and their motives are also different. The result is disequilibrium between the two. To quote G.N. Bajpai again: “The unequal distribution of entrepreneurial talents and risk taking proclivities in any economy means that at one extreme end, there are some, whose investment plans may be frustrated for want of enough savings, while at the other end, there are those who do not need to consume all their incomes but who are too inert to save or too cautious to invest the surplus productively. For the economy as a whole, productive investment may thus fall short of its potential level. In these circumstances, the securities market provides a bridge between ultimate savers and ultimate investors and creates the opportunity to put the savings of the cautious at the disposal of the enterprising, thus promising to raise the total level of investment and hence growth. The indivisibility or lumpiness of many potentially profitable but large investments reinforces this argument. These are commonly beyond the financing capacity of any single economic unit but may be supported if the investor can gather and combine the savings of many.3 Moreover, the availability of yield bearing securities, makes present consumption more expensive relative to future consumption and, therefore, people might be induced to consume less today. The composition of savings may also change with fewer savings being held in the form of idle money or unproductive durable assets, simply because more divisible and liquid assets are available.”

The securities market facilitates the globalisation of an economy by providing connectivity to the rest of the world. This linkage helps the inflow of capital into the country’s economy in the form of portfolio investment. Besides, a strong domestic stock market performance will also enable well-run local companies to raise capital abroad. Some of the Indian companies like Reliance, Infosys, L & T, Tata Steel and many others have, for instance, successfully tapped markets abroad and secured huge amounts, a prospect unthinkable hardly a decade back or even now in the domestic market. This practice will, in turn, help raise the efficiency of domestic corporates once they are exposed to international competitive pressures and the necessity of not only surviving amidst competition but also to perform well for their continued survival.

The existence of a domestic securities market will deter capital flight from the domestic economy by providing attractive investment opportunities locally. Economists also point out that a developed securities market successfully monitors the efficiency with which the existing capital stock is deployed and thereby significantly increases the average rate of return on investment. Having established the importance of the securities market for promoting corporate governance standards, and equally important economic development of a country, let us turn to India and its securities market.

Abolition of Controller of Capital Issues and Emergence of SEBI

Earlier, prior to the setting up of SEBI, the Capital Issues (Control) Act, 1947 governed capital issues in India. The main objectives of this Act were: (i) to ensure that investment in the private corporate sector does not violate priorities and objectives laid down in the Five Year Plans or flow into unproductive sectors; (ii) to promote the expansion of private corporate sector on sound lines in general, and further the growth of particular corporate enterprises having sound capital structure and (iii) to distribute capital issues time-wise in such a manner that there is no overcrowding in a particular period. The Act was enacted to ensure sound capital structure for corporate enterprises, to promote rational and healthy expansion of joint stock companies in India and to protect the interests of the investing public from the fraudulent practices of fly-by-night operators. The authority for control of capital issues was vested with the Controller of Capital Issues (CCI), according to the principles and policies laid down by the central government. However, the office of the Controller of Capital Issues which was functioning more like an extended arm of the government controlled, rather than guided the orderly development of the capital market and became an anachronism in the new era of a liberalised economy.

The Narasimham Committee on the reform of the financial system in India recommended the abolition of the CCI. The committee in its report submitted in 1991 on the financial system argued that the capital market was tightly controlled by the government and there were a number of restrictions placed by the CCI on the operations of this market. This restrictive environment was “neither in tune with the new economic reforms nor conducive to the growth of the capital market”. The committee strongly favoured substantial and speedy liberalisation of the capital market by closing down the office of the CCI. It suggested that SEBI set up in 1988 should be entrusted with the “task of a market regulator to see that the market is operated on the basis of well laid principles and conventions”. It was also recommended that SEBI should not become a controlling authority substituting the CCI. The government of India accepted this recommendation, repealed the Capital Issues (Control) Act, 1947 and abolished the post of the Controller of Capital Issues.

The significance of this step lies in the removal of bureaucratic hurdles in the way of capital issues. In order to raise capital from the market, the companies were required earlier to obtain consent from the CCI who decided the terms and conditions, the amount of capital to be raised and the pricing of public issues. With the abolition of the CCI, companies became free to issue capital and determine the issue prices based on market conditions. For this, however, they are expected to abide by guidelines prescribed by SEBI. In other words, SEBI has been empowered to control and regulate the new issue and old issues market, namely, the Stock Exchange. The following pages provide details of the objectives, powers, responsibilities, success and failures of SEBI—India’s capital market regulator.

The Securities and Exchange Board of India

The Securities and Exchange Board of India Act, 1992 was enacted by the Indian Parliament “to provide for the establishment of a Board to protect the interests of investors in securities and to promote the development of, and to regulate the securities market and for matters connected therewith or incidental thereto”.

The SEBI Act, 1992 was enacted “to provide for the establishment of a board to protect the interests of investors in securities and to promote the development of, and to regulate the securities market and for matters connected therewith or incidental thereto.”

Objectives of the Board

Section 11(1) of the Securities and Exchange Board of India Act, 1992 explains the powers and functions of SEBI. As per the Act, it shall be the duty of the board to protect interests of the investors in securities and to promote the development of, and to regulate the securities market by such measures as it thinks fit.

The statutory objectives of the SEBI as per the Act are given below:

- Protection of investors’ interests in securities

- Promotion of the development of the securities market

- Regulation of the securities market; and

- Matters connected therewith and incidental thereto.

Functions of the Board

To realise the above core objectives and to carry out its tasks, the Act spells out the functions of SEBI in greater details, as under:4

The act spells out the functions of SEBI regulating the business in stock exchanges and any other securities markets, registering and regulating the working of stock brokers, sub-brokers, share transfer agents, bankers to an issue, trustees of trust deeds, registrars to an issue, merchant bankers, underwriters, portfolio managers, invesment advisers and such other intermediaries who may be associated with securities markets in any manner; prohibiting insider trading in securities.

- Regulating the business in stock exchanges and any other securities markets

- Registering and regulating the working of stock brokers, sub-brokers, share transfer agents, bankers to an issue, trustees of trust deeds, registrars to an issue, merchant bankers, underwriters, portfolio managers, invesment advisers and such other intermediaries who may be associated with securities markets in any manner

- Registering and regulating the working of the depositories, participants, custodians of securities, foreign institutional investors, credit rating agencies and such other intermediaries as the board may, by notification, specify in this behalf

- Registering and regulating the working of venture capital funds and collective investment schemes including mutual funds

- Promoting and regulating self-regulatory organisations

- Prohibiting fraudulent and unfair trade practices relating to securities markets

- Promoting investors’ education and training of intermediaries of securities markets

- Prohibiting insider trading in securities

- Regulating substantial acquisition of shares and take over of companies;

- Calling for information from, undertaking inspection, conducting inquiries and audits of the stock exchanges, mutual funds and other persons associated with the securities markets and intermediaries and self-regulatory organisations in the securities market

- Performing such functions and exercising such powers under the provisions of the Securities Contracts (Regulation) Act 1956 as may be delegated to it by the central government

- Levying fees or other charges

- Conducting research

- Calling from or furnishing to any such agencies, as may be specified by the board, such information as may be considered necessary by it for the efficient discharge of its functions

- Performing such other functions as may be prescribed

Powers of the Board

To carry out its responsibilities under the Act, the board is entrusted with the same powers as are vested in a civil court in respect of the following matters, namely:

- The discovery and production of books of account and other documents at such place and such time as may be specified by the board

- Summoning and enforcing the attendance of persons and examining them on oath

- Inspection of any books, registers and other documents of stockbrokers, sub-brokers, and share transfer agents etc.

Matters To Be Disclosed by the Companies to the Board [Section 11A]

The board may, for the protection of investors, specify the following by regulations:

- The matters relating to issue of capital, transfer of securities and other matters incidental thereto

- The manner in which such matters shall be disclosed by the companies.

The board is empowered under the SEBI Act to issue directions to the following intermediaries: Stock-brokers, sub-brokers, share transfer agent, banker to an issue, trustee of trust deed, registrar to an issue, merchant banker, underwriter, portfolio manager, depository, depository participant, custodian of securities, foreign institutional investor, credit rating agency or any other intermediary associated with the securities market.

Power to Issue Directions

Under Section 11 B of the SEBI Act, the board is empowered to issue directions to the following intermediaries:

- Stock-brokers, sub-brokers, share transfer agent, banker to an issue, trustee of trust deed, registrar to an issue, merchant banker, underwriter, portfolio manager, investment adviser and such other intermediary who may be associated with securities market

- Depository, depository participant, custodian of securities, foreign institutional investor, credit rating agency or any other intermediary associated with the securities market

- Sponsors of venture capital funds, or collective investment schemes including mutual funds

- And to any company with regard to matters to be disclosed by the companies as specified in Section 11A.

Registration of Intermediaries

Different intermediaries mentioned above can commence functioning in their respective activities only after registration with the SEBI and complying with requirements as stated under specific regulations intended for each.

- No stock-broker, sub-broker, share transfer agent, banker to an issue, trustee of trust deed, registrar to an issue, merchant banker, underwriter, portfolio manager, investment adviser, and such other intermediary who may be associated with securities market shall buy, sell or deal in securities except under and in accordance with the conditions of a certificate of regulations made under this Act.

- No securities, foreign institutional investor, credit rating agency or any other intermediary associated with the securities market as the board may, by notification in this behalf specify, shall buy or sell or deal in securities except under and in accordance with the conditions of a certificate of registration obtained from the Board in accordance with the regulations made under this Act.

- No sponsored or carryon or cause to be carried on any venture capital funds or collective investment schemes including mutual funds unless he obtains a certificate of registration from the board in accordance with the regulations.

SEBI has issued detailed rules and regulations to be adhered to by each of the intermediaries above specified.

Establishment of Securities Appellate Tribunals

The SEBI Act also contained a provision for the establishment of an appellate authority to arbiter and exercise power in matters of disputes over SEBI’s decisions as a regulator.

The central government shall by notification, establish one or more Appellate Tribunals to be known as the Securities Appellate Tribunal to function as Appellate Authority and hear appeals.

Civil Court Not to Have Jurisdiction

It is stipulated in the SEBI Act that under Section 15(Y) that no civil court shall have jurisdiction to entertain any suit or proceeding in respect of any matter which an adjudicating officer appointed under this Act or a Securities Appellate Tribunal constituted under this Act is empowered by or under this Act to determine and no injunction taken or to be taken in pursuance of any power conferred by or under this Act. However, appeals against the decision of the Securities Appellate Tribunal can be preferred before a High Court.

Strengthening of SEBI

In January 1995, the Government of India promulgated an Ordinance to amend SEBI Act, 1992, so as to arm the regulator with additional powers for ensuring the orderly development of the capital market and to enhance its ability to protect the interests of investors. The important features of this Ordinance are the following:

- To enable SEBI to respond speedily to market conditions and to reinforce its autonomy, it has been empowered to file complaints in courts and to notify its regulations without prior approval of the government.

- SEBI is now provided with regulatory powers over companies in the issuance of capital, the transfer of securities and other related matters.

- SEBI is now empowered to impose monetary penalties on capital market intermediaries and other participants for a listed range of violations. The amendment proposed to create an adjudicating mechanism within SEBI for imposing penalties and also constituted a separate tribunal to deal with cases of appeal against orders of the adjudicating authority. Earlier, the SEBI Act provided for the suspension and cancellation of registration and for the prosecution of intermediaries, which led to the stoppage of business. The new system of monetary penalties constitutes an alternative mechanism for dealing with capital market violations.

- While investigating irregularities in the capital market, SEBI is now given the power to summon the attendance of and call for documents from all categories of market intermediaries, including persons from the securities market. Likewise, SEBI has now the power to issue directions to all intermediaries and persons connected with securities markets with a view to protecting investors or securing the orderly development of the securities market.

- It was thought that SEBI has all necessary powers to control and regulate the securities market on the one side and effectively protect the interests of the shareholders on the other. However, the stock markets in India have gone through one of the worst and most prolonged crisis in their history, due to the inability of the market regulator to bring to book market violators.

In January 1995, the Government of India promulgated an ordinance to amend SEBI Act, 1992 to arm the regulator with additional powers. Among other power it has been empowered to file complaints in courts and to notify its regulations without prior approval of the government, provided with regulatory powers over companies in the issuance of capital, the transfer of securities and other related matters, and to impose monetary penalties on capital market intermediaries and other participants for a listed range of violations.

SEBI (Amendment) Bill, 2002

Notwithstanding the regulator’s best efforts, the stock market was plagued by price manipulations and insider trading. SEBI known for its low indictment rate of violators of its rules hardly penalised insider traders and was dubbed a toothless tiger. Unscrupulous players and fly-by-night operators abounded, manipulated the system and share prices with impunity, while the regulator watched helplessly from the sidelines. In its defence, SEBI has been pointing out that the law did not give it adequate powers and that the existing penalties (Rs. 5,000 to 5 lakh) were too meagre to deter violators. Taking cognisance of this constraint, the government introduced the Securities and Exchange Board of India (Amendment) Bill, 2002 in the Lok Sobha in November 2002. The Bill was passed by the Parliament on 2 December 2002. It replaced the Ordinance issued by the government on 29 October 2002. The Bill made four key changes that gave SEBI extensive powers to regulate the market. The changes made under the amended Act were as under:

- Search and seizure powers: Earlier, a SEBI officer could only ask market players for specific documents, which allowed the latter to conceal incriminating documents. In the new Act, SEBI’s officers, armed with a search warrant from a judicial magistrate, can search the entity’s premises and even seize documents.

- Freeze bank accounts: SEBI can now impound cash proceeds and securities connected to any transaction it is investigating. It can also, with authorisation from a judicial magistrate, freeze bank accounts of any person or entity involved in any market violation for a duration of 1 month.

- Greater monetary penalties: Earlier, the maximum fine that SEBI could impose on a violator was only up to Rs. 5 lakh. This limit has now been increased manifold in market manipulation or insider trading violations, the fine could go up to Rs. 25 crore or three times the profits made by the entity concerned. For other violations such as non-disclosure, a fine upto Rs. 1 crore could be levied on violators.

- More board strength: The strength of the SEBI’s board has been increased from six to nine of which three (excluding the chairman) will have to be full-time directors. Till the amendment of Act, the SEBI chairman was the only full-time director. The Securities Appellate Tribunal (SAT), the SEBI body that decides on appeals made by market intermediaries and companies against orders passed by the SEBI chairman, has also been strengthened with an increase in number of members from one to three. The idea is to move from individual based to group-based decision making, thereby reducing the possibility of any error or bias.

SEBI’s Role in Promoting Corporate Governance

G.N. Bajpai, former Chairman, Securities and Exchance Board of India, claimed in an international conference in 2003: “With the objective of improving market efficiency, enhancing transparency, preventing unfair trade practices and bringing the Indian market up to international standards, a package of reforms consisting of measures to liberalise, regulate and develop the securities market was introduced in the 1990s. The practice of allocation of resources among different competing entities as well as its terms by a central authority was discontinued. The issuers complying with the eligibility criteria now have freedom to issue the securities at market-determined rates. The secondary market overcame the geographical barriers by moving to screen-based trading, which made trading system accessible to everybody anywhere in the Indian sub-continent. Trades enjoy counter-party guarantee. The trading cycle has been shortened to a day and trades are settled within two working days while all deferral products are banned. Physical security certificates have almost disappeared. A variety of derivatives are available. In fact, some reforms such as straight through processing in securities, T+2 rolling settlement, clearing corporation being the central counter party to all the trades on the exchanges, real time monitoring of brokers positions and margins, and automatic disabling of brokers’ terminals are singular to the Indian securities market. Indian disclosure and accounting standards are as modern, updated, potent and versatile as those of any other market. Today, the Indian securities market stands shoulder to shoulder with most developed markets in North America, Western Europe and Far East.”5

According to SEBI’s former chairman, The Securities and Exchange Board of India has been focussing on the following areas to improve corporate governance:

- Ensuring timely disclosure of relevant information

- Providing an efficient and effective market system

- Demonstrating reliable and effective enforcement

- Enabling the highest standards of governance.

Disclosure standards

The erstwhile SEBI chairman, G.N. Bajpai, claims quoting academicians and researchers that disclosure standard in the Indian regulatory jurisdiction are at par with the best in the world. According to him this is a feedback from several global organisations, both regulatory and market participants.

SEBI has ensured that a company is required to make specified disclosures at the time of issue and make continuous disclosures as long as its securities are listed on exchanges. The standards for these disclosures including the content, medium and time of disclosures have been specified in the Companies Act, Disclosure and Investor Protection Guidelines, Listing Agreement Regulations relating to insider trading and takeover etc. These disclosures are made through various documents such as prospectus, quarterly statements, annual reports etc. and are disseminated through media, web sites of the company and the exchanges, and through EDIFAR (Electronic Data Information Filing and Retrieval) system maintained by the regulator. These disclosures relate to financial performance, sharehoding pattern, trading by insiders, substantial acquisitions, related party disclosures, audit qualifications, buyback details, corporate governance, actions taken against company, risk management, utilisation of issue proceeds, remuneration of directors etc. All listed companies and organisations associated with securities markets including the intermediaries, asset management companies, trustees of mutual funds, SROs, stock exchanges, clearing house/corporations, public financial institutions, professional firms such as auditors, accountancy firms, law firms, consultants, etc. assisting or advising listed companies are required to abide by the Code of Corporate Disclosure Practices specified in SEBI (Insider Trading) regulations.

SEBI has ensured that a company is required to make specified disclosures at the time of issue and make continuous disclosures as long as its securities are listed on exchanges. The standards for these disclosures including the content, medium and time of disclosures have been specified in the Companies Act, Disclosure and Investor Protection Guidelines, Listing Agreement Regulations relating to insider trading and takeover etc. These disclosures are made through various documents such as prospectus, quarterly statements, annual reports etc.

Efficient and effective market system

In the opinion of the chairman of SEBI, the Indian securities market has a large infrastructure to meet the demands of a sub-continental market. Presently, there are 25 stock exchanges and about 10,000 brokers, 15,000 sub-brokers, more than 10,000 listed companies, 500 foreign institutional investors, 400 depository participants, 150 merchant bankers, 40 mutual funds offering over 450 schemes, and 20 million investors. Yet, there is only one regulator. Not only the numbers are gigantic but also the systems and infrastructure are equally atlantean and sophisticated. All stock exchanges in India offer on line, fully automated, nation-wide anonymous, order-driven screen based trading system. It has a comprehensive risk management system. The depositories legislation ensures free transferability of securities with speed, accuracy and security. The securities are transferred electronically in demat form. Further, Indian accounting standards follow international accounting standards (principle based) and are by and large aligned. In addition to creating an efficient trading platform and settlement mechanism, SEBI’s focus is substantially directed towards the following:

- Provision of timely availability of high quality price sensitive information to the market participants to enable them take informed decision and ensure efficient price discovery

- Maintenance of high quality of services and fair conduct for market participants. The regulations specify high standards to become market intermediaries and require them to abide by a code of conduct

- Ensuring that the market is fair, transparent and safe so that issuers and investors are at ease to carry out transactions.

Reliable and Effective Enforcement

SEBI aims at ensuring that no misconduct goes unnoticed or unpunished. It keeps an eye on the happenings in the market and identifies anything unusual or undesirable which may adversely affect the efficacy of the market. Every market participant, irrespective of his size and influence in the market or in the policy, is held accountable for his misdeeds. The proactive approach of the regulator in enforcement can be gauged from the fact that during the financial year 2002–2003, SEBI passed 561 orders, out of which over 350 were punitive.

Highest Standards of Governance

SEBI has avowed that its regulation and guidance of the country’s securities market would spell success in the area of corporate governance. The Kumar Mangalam Birla Committee of the Indian jurisdiction outlined a code of good corporate governance, which compared very well with the recommendations of the Cadbury Committee and the OECD codes. The code was operationalised by inserting a new clause (Clause 49) to the Listing Agreement (LA) and have been made applicable to all the listed companies in India in a phased manner. Following the implementation of the Birla committee recommendations, substantial developments took place in the corporate world and securities market, which required revisit of the issue. The Narayana Murthy Committee has refined the corporate governance norms, which are proposed to be implemented through modification in the listing agreement. The government also appointed few committees to suggest ways and means of realising good corporate governance. Based on their recommendations, government is trying to provide statutory back-up to corporate governance standards.

SEBI has avowed that its regulation and guidance of the country’s securities market would spell success in the area of corporate governance. The Birla committee outlined a code of good corporate governance. The code was operationalised by inserting a new clause (clause 49) to the Listing Agreement (LA) and have been made applicable to all this listed companies in India in a phased manner.

The initiatives for improvement in corporate governance, according to G.N. Bajpai, come mainly from three sources, namely, the market, regulator and the legislature. While the legislative initiative is directed towards bringing about amendments to the basic law-India’s Companies Act to include certain fundamental provisions related to corporate governance, dynamic aspects of corporate governance such as disclosures, accounting standards etc. are being pursued through the regulatory initiatives by bringing about amendments to the Listing Agreement. Such an approach is aimed at because a comparatively more complicated and protracted process is involved in the amendments to legislation in a truly democratic society like India’s. The most important initiative comes from market forces and mechanisms, which encourage and insist on the management’s improving the quality of corporate governance. Indian market has formalised such forces in the form of a rating called “Corporate Governance and Value Creation Rating”, which according to SEBI chairman is quite unique in the world and is sought after voluntarily by companies.

SEBI’s Record of Performance

R. Rajagopalan in his book Directors and Corporate Governance makes the following observation on the role of SEBI: “The Securities and Exchange Board of India and its various committees should be complimented for many things happening in the capital market in India. Be it in the area of protection of small investors’ interests, or technology upgradation or development of securities market, SEBI has indeed been working with commensurate speed and efficiency in the last couple of years. There has, however, been a common perception that SEBI has not developed a cadre of regulatory personnel to effectively track violations. After the Harshad Mehta’s securities scam in 90s which was blamed on a systemic failure, the system needed a thorough overhauling. However, nothing really happened. Later another scamster, Ketan Parikh made use of the loopholes in the system to his advantage. He was instrumental in rigging the prices of shares resulting in heavy losses to the investing public, which led to erosion of faith in the capital market. Over the years, quite a few companies raised money through IPOs and disappeared without a trace. It is not seen that the perpetrators of these frauds are promptly brought to book.”

SEBI’s Role in the New Era

In the changed environment of the Indian economy, when after more than four decades of heavy regulation and anemic growth, with the government slowly opening the economy to market forces, and promoting modification of financial institutions, SEBI has to play a proactive role as a capital market regulator. SEBI’s performance has to be judged in the context of its efficiency in this dynamic environment. The SEBI has made progress in a number of areas:

- Abolition of capital issues control and retaining the sole authority for new capital issues

- Regulation and reform of the capital market by arming itself with necessary authority and powers

- Regulating stock exchanges under Securities Contracts Regulation Act

- Bringing all primary and secondary market intermediaries under the regulatory framework

- Enforcing the companies to disclose all material facts and specific risk factors associated with projects while going in for public issues.

The record of the SEBI, over the period, has indeed been encouraging. SEBI has sought to check and control unfair practices on the stock exchanges, acted against transgressing companies, brokers accused of rigging prices, and scrips showing large price movements. At the same time, SEBI has sought to reduce regulation, and instead to leave it largely to the players in the market.

The capital market is composed of two constituents: the primary market and the secondary market. While the primary market deals with the issue of new stocks and shares, the secondary market deals with the buying and selling of existing stocks and shares. SEBI, as a regulator of capital market, has to play a regulatory role in both these markets. With a view to improving practices and ensuring greater transparency in capital markets so as to have a healthy capital market development and promote corporate governance among companies, SEBI has taken several steps as given below:

Primary Market Reforms

The primary capital market plays an important role in the overall functioning of securities market. Vibrancy of primary market, among other things, is a function of macro economic factors, industrial output and demand. Over the years, the Securities and Exchange Board of India, the market regulator, has taken several initiatives to improve the operational efficiency and transparency of the primary market, which provides investors with issues of high quality and for firms a market where they can raise resources in a cost-effective manner. However, despite these measures the primary market remained lackluster in recent years.

Bonds have been the primary instruments for the resource mobilisation in the primary market followed by equity. Equity with premium compared to the previous year, more than doubled in 2002–2003, while issues in the public sector were dominant during the year, compared to the issues in the private sector, which raised about 87 per cent in the previous year.

With regard to the primary market, the part of the capital market that concerns with the issues of new stocks and shares, the following major changes have been effected by SEBI:

With regard to the primary market, the following major changes have been effected by SEBI: Relating to new issues new norms were introduced; freedom to fix par value of shares; guidelines for tightening the entry norms issued; relating to IPOs measures were spelt out; investor protection measures were taken; cost reduction measures.

- Relating to new issues: In case of new issues, the SEBI has introduced various guidelines and regulatory measures for capital issues with the objective of strengthening standards of disclosures, and certain procedural norms for the issuers and intermediaries with a view to removing the inadequacies and systemic deficiencies in the issue procedures. Companies issuing capital in the primary market are now required to disclose all material facts and specific risk factors regarding the projects; they should also give information regarding the basis of calculation of premium. Companies are free to fix the premium. SEBI has also introduced a code of advertisement for public issues with a view to ensuring fair and truthful disclosures. The prospectus should not contain statements that would mislead the investors. The SEBI has also put in place a system of appointing its representatives to supervise the allotment process and to minimise malpractices in the allotment of oversubscribed issues. Prudential norms have also been laid down for right issues.

- Freedom to fix par value of shares: The SEBI has dispensed with the requirement to issue shares with a fixed par value of Rs. 10 and Rs. 100 and has given the freedom to companies to determine the par value of shares issued by them. Companies with dematerialised shares have been allowed to alter the par value of a share indicated in the Memorandum and Articles of Association. The existing companies, which have issued shares at Rs. 10 and Rs. 100, can avail of this facility by consolidating, splitting their existing shares.

- Guidelines for tightening the entry norms: Guidelines for tightening the entry norms for companies accessing capital market were issued by the SEBI on 16 April 1996. Accordingly, a company should have a track record of dividend for a minimum 3 years out of the immediate preceding 5 years. If a manufacturing company does not have such a track record, it can access the public issue market subject to the condition that projects have been appraised by a public financial institution or a scheduled commercial bank and such appraising agency is also participating in the project fund.

- Relating to IPOs: To encourage Initial Public Offers (IPO), SEBI has let companies determine the par value of shares issued by them. SEBI has permitted issues of IPOs to go for “book building”, i.e. reserve and allot shares to individual investors. However, the issuer will have to disclose the price, the issue size and the number of securities to be offered to the public.

- Investor protection measures: On 15 June 1998, SEBI advised investors to exercise a greater deal of caution while investing in plantation companies. At the same time, plantation companies and other collective investment schemes were directed to obtain credit rating from accredited agencies prior to the issue of advertisement.

- Cost reduction measures: To reduce the cost of issue, SEBI has made underwriting of issue optional, subject to the condition that if an issue was not underwritten and was not able to collect 90% of the amount offered to the public, the entire amount collected should be refunded to the investors. The lead managers have to issue due diligence certificate, which has now been made part of the offer document.

- Relating to private placement market: Private placement market has become popular with issuers because of stringent entry and disclosure norms for public issues. Low cost of issuance, ease of structuring investments and saving of time lag in issuance has led to the popularity and rapid growth of private placement. Total resource mobilisation through private placement market had risen by more than three times between 1995–96 and 1998–99.

- Banker to the issue under SEBI’s purview: The “Banker to the Issue” is now brought under the purview of SEBI for investor protection. The Unit Trust of India (UTI) has been brought under the regulatory jurisdiction of SEBI.

- Regulations on acquisitions and takeovers: SEBI has raised the minimum application size and also the proportion of each issue allowed for firm allotment to institutions such as mutual funds. SEBI has also introduced regulations governing substantial acquisition of shares and take-overs and lays down the conditions under which disclosures and mandatory public offers have to be made to shareholders.

- Merchant banking under SEBI’s jurisdiction: Merchant banking has been statutorily brought under the regulatory framework of SEBI. Merchant bankers are now to be authorised by SEBI and have to adopt the stipulated capital adequacy norms, abide by a code of conduct which stipulates a high degree of responsibility towards inspectors in respect of the pricing and premium fixation of issues. Merchant bankers will also have to adhere to provisions relating to disclosures or offer letters for issues.

- Permission to set up private mutual funds: The government has now permitted the setting up of private mutual funds. A few have already been set up. All mutual funds are allowed to apply for firm allotments in public issues. To improve the scope of investments by mutual funds, the latter are permitted to underwrite public issues. SEBI has relaxed the guidelines for investment in money market instruments. The market regulator has issued fresh guidelines for advertising by mutual funds.

- Making companies provide authentic information: SEBI has advised stock exchanges to amend the listing agreements to ensure that a listed company furnishes annual statement to the stock exchange showing the variations between financial projections and the projected utilisation of funds in the offer documents and the actual utilisation. This would enable shareholders to make comparisons between promises and performance of companies they invested in.

- Making companies comply with issue norms: In order to make companies exercise greater care and diligence for timely action in matters relating to the public issues of capital. SEBI has advised stock exchanges to collect from companies making public issues, a deposit of 1% of the issue amount which could be forfeited in case of non-compliance of the provisions of the listing agreement and non-dispatch of refund orders and share certificates by registered post within the prescribed time.

- Scrutiny of offer documents: SEBI scrutinises offer documents to ensure that the company in the offer document has made all disclosures. All the guidelines and regulatory measures of capital issues are meant to promote healthy and efficient functioning of the issue market.

- Access to international capital market: Since 1992, the government of India has permitted Indian companies to access international capital markets through Euro equity shares. Initially, the Euro-issue proceeds were to be utilised for approved end uses within a period of 1 year from the date of issue. Since there was continued accumulation of foreign exchange reserves with the Reserve Bank and there were long gestation periods of new investments, the government allowed the issuing companies to retain the Euro-issue proceeds abroad and repatriate them to the country only as and when expenditure for the approved end uses were incurred.

The government of India has also liberalised investment norms for Non-Resident Indians (NRIs) so that they and overseas corporate bodies can buy shares and debentures without prior permission of the Reserve Bank of India which has been the practice followed hitherto.

Secondary Market Reforms

In the matter of reform of the secondary market, a market that is engaged in the buying and selling of old stocks and shares, SEBI has initiated the following measures:

In the secondary market, SEBI has initiated measures: registration of intermediaries, reconstitution of stock exchange governing bodies and regulation of collective investment schemes.

- Registration of Intermediaries: SEBI has started the process of registration of intermediaries, such as the stockbrokers and sub-brokers under the provisions of the Securities and Exchange Board of India Act, 1992. The registration is made on the basis of certain eligibility norms such as capital adequacy, infrastructure etc. There has been much opposition and resistance to this step of SEBI.The capital market regulator has also made rules for making client-broker relationships more transparent, particularly with reference to the segregation of client and broker accounts.

- Reconstitution of stock exchange governing bodies: To make the governing body (GB) of a stock exchange more broad-based, SEBI has issued guidelines for its composition. According to these guidelines, the governing body of a stock exchange should have five elected members, of which not more than four nominated by the government or SEBI and three or fewer persons nominated as public representatives. During 1994–95, SEBI has reconstituted the governing bodies of stock exchanges.

- Measures to speed up settlements: SEBI has prohibited “renewal” of transactions in ‘B’ group securities, so that transaction could be settled within 7 days.

- Simplification of procedures: Since 1992, SEBI has constantly reviewed the traditional trading system in Indian stock exchanges. SEBI is simplifying procedures and achieving transparency in costs and prices at which customer orders are executed, speeding up clearing and settlement and finally transfer of shares in the names of buyers. SEBI is setting up depositories, which would immobilise securities and help eliminate paper work—this would give impetus to the growth of stock markets.

- Regulations on insider trading: SEBI has notified regulations on insider trading under the provisions of SEBI Act. Such regulations are meant to protect and preserve the integrity of stock markets and, in the long run, to help inspire investor confidence in them. Despite these regulations, insider trading is rampant in our stock exchanges, and rigging the market and manipulating stock market price quotations are quite common. M.S. Shoes East Ltd. fiasco was an example of market rigging in March 2001; SEBI could do nothing about it though it was known that coteries of stockbrokers connived to hammer the Bombay Stock Exchange with rigging.

- Regulation of collective investment schemes: SEBI’s regulations for collective investment schemes (CIS) were notified on 15 October 1999. CIS includes any scheme, or arrangement with respect to property of any description, which enables investors to participate in the scheme by way of subscription and to receive profits or income or produce arising from the management of such property. Under the SEBI Act and Regulations framed thereunder, no person can carry on any CIS unless he obtains a certificate of registration from SEBI.All existing CISs were required to apply for registration by 14 December 1999.

- Regulation of foreign investments: The government has allowed foreign institutional investors (FIIs) such as pension funds, mutual funds, investment trusts, asset or portfolio management companies etc. to invest in the Indian capital market provided they are registered with SEBI. Till January 1995, as many as 286 FIIs have been registered with SEBI.There were only ten in January 1993. The cumulative net investment of FIIs on Indian equities has increased from $200 million in January 1993 to $3 billion in January 1995, and to $60 billion as on May 2005, according to a report in Economic Times (11 May 2005) reflecting the healthy impact of economic liberalisation policy of the country and to some extent, the prevalence of low rates of interest abroad. The government of India has now permitted joint venture stock broking companies to have non-Indian citizens on their boards of directors.

- Introduction of compulsory rolling settlement: In keeping with international best practice, SEBI has introduced compulsory rolling settlement of select scrips on 10 January 2000. In June 2000, SEBI introduced derivatives trading. As far as internet trading is concerned, SEBI has prescribed minimum technical standards to be enforced by stock exchanges for ensuring safety and security of transactions via the internet. Rolling Settlement has been extended to all scrips on all the stock exchanges with effect from 31 December 2001. SEBI has further decided to shorten the rolling settlement cycle from present T+5 to T+3 for all listed securities from 1 April 2002. The markets have now moved to T+2 settlement from 1 April 2003.

- One point access to investors: In July 2002, SEBI launched a centralised internet based filing system for listed companies called EDIFAR (Electronic Data Information Filing and Retrieval System), which requires companies to post disclosures as per the listing agreement with the stock exchange on the EDIFAR website at the same time as they submit them to the exchange. The objective of EDIFAR is to provide investors simultaneous, one-point access to key information on all listed companies.

Beginning July 2002, SEBI has been posting all orders passed by its chairman against errant companies and market intermediaries on its website. This provides useful information to investors.

- Introduction of takeover codes: With regard to mergers and acquisitions, SEBI has made several investor-friendly amendments to the takeover code in recent months. For example, preferential allotments were brought under the ambit of takeover code in September 2002. This would stop the practice of promoters making preferential allotments to avoid making an open offer to other shareholders. Acquirers also have to disclose their holding more frequently, which increases transparency.

- Trading of government securities through order-driven screen-based system: With a view to encouraging wider participation of all classes of investors, trading in government securities through a nationwide, anonymous, order-driven, screen-based trading system of the stock exchanges, in the same manner in which trading takes place in equities, was launched on 16 January 2003, initially on Bombay Stock Exchange (BSE), National Stock Exchange (NSE) and Over the Counter Exchange of India (OTCEI).

- Delisting guidelines: The market regulator has issued the SEBI (Delisting of Securities) Guidelines, 2003 on 17 February 2003. The guidelines provide that companies can delist from stock exchanges only by offering an exit route to remaining shareholders through a “reverse book building” process. This mechanism would leave the option of pricing to the investors and would be totally transparent to the market. Further, the promoter shall offer a floor price on the basis of average of previous 26-weeks high and low prices to investors.

- Central listing authority: To bring about the uniformity in scrutinising listing applications across the stock exchanges and to strengthen the listing agreements, SEBI has, in April 2003, established the Central Listing Authority in Mumbai. Former Chief Justice of India, Justice M.N. Venkatachelliah, has been appointed as the president of the Authority. There shall be eight other members of the Authority, all of whom shall hold office for a period of 3 years. They shall discharge the following functions: (i) processing the application made by corporates, mutual funds, or collective investment schemes and (ii) making recommendations as to listing conditions.

- Derivative trading: The Central Government lifted the prohibition on forward trading in securities by a notification issued on 1 March 2000 rescinding the 1969 notification. With the enabling enactment of the Securities Laws (Amendment) Act, 1999 in December 1999, trading in stock index futures started in June and July 2001 respectively. Single stock futures have also been introduced since 9 November 2001.

Interest Rate Derivatives trading was formalised on the stock exchanges with the launch of futures on 10-year zero yield coupon bond and zero-coupon notional T-Bill in June 2003.

- Demutualisation and corporatisation of regional stock exchanges: Recently (2004), the Securities Contract (Regulations) Act (SCRA) was amended through the promulgation of an ordinance to make corportisation and demutualisation of stock exchanges mandatory. The ordinance has been issued on the basis of the recommendation of a group under the chairmanship of Justice M.H. Kania, former Chief Justice of India, to advise the government on the issue of corporatisition of stock exchanges. The amendment not only requires separation of ownership and trading rights, it also requires that the majority ownership rests with the public and those without any trading rights. Also through these conditions, the government has signalled a major shift in its earlier stand that stock exchanges should be self-regulating agencies of their members. It now desires that they should be externally regulated.

Further, SEBI has introduced measures in the secondary market, delisting guidelines, central listing authority, derivative trading, and demutualisation and corporatisation of regional stock exchanges.

Traditionally, the Regional Stock Exchanges (RSEs) functioned as mutual societies owned and operated by member brokers. A few of them have already switched to the corporate form. The new action plan now requires them to segregate ownership rights from trading rights. Professionals rather than broker representatives will conduct the affairs of the exchanges. Can the RSEs come together as has been proposed many times and transform themselves into the country’s third exchange along with the National Stock Exchange (NSE) and Bombay Stock Exchange (BSE)? That is a moot question, though few will question the need for increased competition that will give greater choice to investors.

However, in practice, it has always been difficult to form a third all India exchange. Despite the current moves to restructure the RSEs, there is no guarantee that a demutualised and corporate exchange by itself will be the recipe for survival and eventual success. On the contrary, in the opinion of experts, there are valid reasons to be skeptical. The RSEs, in their new form will require a large number of stock market professionals who are scarce. Besides, an exchange operating for profit may sacrifice regulatory concerns for commercial gains.

At present stock exchanges in India are “mutual” and non- profit organisations enjoying tax exemption. The trading members are stockbrokers who also own, control and manage such exchanges for their mutual benefit. The ownership rights and trading rights are combined together in a membership card, which is not freely transferable.

At present stock exchanges in India are “mutual” and non-profit organisations enjoying tax exemption. The trading members are stockbrokers who also own, control and manage such exchanges for their mutual benefit. The ownership rights and trading rights are combined together in a membership card, which is not freely transferable. A publicly held organisation is in a position to ensure greater transparency in dealings, accountability and market discipline and is amenable to changes.

On the other hand, a “demutual” exchange is one in which three distinct sets of people own the exchange, manage it and use its services. The three stakeholders are shareholders, brokers and investing public. The management is vested in a board of directors, assisted by a professional team. A demutualised exchange is generally a profit organisation and a tax paying entity. The ownership rights are freely transferable and there is no membership card.

A typical mutual exchange managed by broker’s representatives is not an ideal model for an enlightened self-regulatory organisation. In this regard, a demutualised framework is expected to have a balanced approach without the inherent conflict of interest. It can generate a greater management accountability. In a competitive environment stock exchanges require funds and to raise funds, mutualised organisations suffer from their own limitations, whereas a demutualised set-up can tap capital markets. A publicly held organisation is in a position to ensure greater transparency in dealings, accountability and market discipline and is amenable to changes. However, a demutualised and corporate form of stock exchange is not an unmixed blessing either. According to C.R.L. Narasimhan, an authority on the subject, they have the following disadvantages:6

- It is not as though the new governance structure will automatically be free from pitfalls. There may arise a different conflict of interest. The new look demutualised exchange operating on profit considerations may opt for a course that may conflict with the regulatory role expected of it.

- Although it is unlikely to happen immediately in India, a corporate stock exchange may be listing its shares on an exchange possibly with its own self.

- While a demutualised structure segregates the different roles of owner’s controllers and traders, it is still necessary to invite eminent people on its Board. That is to ensure that the exchanges take care of public interest too and not merely ensure their commercial character.

- In the demutualised exchanges, share capital will be subscribed to by different investors including the trading members. It may become necessary to prescribe a ceiling on voting powers somewhat akin to what obtains today in banking regulation and law. This, of course, is a handicap that has to be overcome by anybody concerned with capital market.

- An amendment to the Securities Contracts Regulation Act is on the cards: other legal changes/concessions are also necessary before demutualisation takes place.

- As in many other areas of the capital market it has been easy to identify what is wrong with the existing system of stock exchange governance. It has been only slightly more difficult to suggest an alternative system, in this case the demutualised exchange.

It is also likely that the government will push for a speedy transition to the new mode of governance. However, even if the board objectives are achieved, it is likely that the perception of the exchange may not improve dramatically over the short term.

SEBI’s Shortcomings

Though SEBI has come a long way in acquiring more powers and wielding great authority in regulating the Indian capital market, it also suffers from a number of shortcomings. These are as follows:

SEBI suffers from a number of shortcomings like lack of adequate required power.

- Lack of adequate required power: While creating the SEBI, the Government of India seems to have been influenced by regulatory measures adopted in the US to guide the country’s securities market into orderly development. The counterpart of SEBI in the US is the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). However, SEC is entrusted with more penal powers to discipline recalcitrant traders in the market. To make SEBI perform and act like SEC, the Government of India should have provided it with powers to penalise and debar wrongdoers. The Indian government should also consider granting powers for suo moto action on any matter concerning the capital market. If SEBI is an intrinsic part of the process of economic structuring, as it is made out to be, then there is every reason to stress that it should be empowered to play an active role in the capital market.

- Buckles under pressure: Even while analysts bemoan SEBI’s lack of empowerment to wield any power with authority in bringing to book wrongdoers, it is a moot point whether the organisation is really interested in exercising its existing authority. It seems to buckle under pressure when there is every reason to be firm. The M S Shoes East fiasco in which SEBI remained a mute spectator is a case in point. A recent (October, 2004) revision of Clause 49 of the listing agreement (LA) is another point in question. Bowing to intense pressure from corporate and industry chambers against its earlier mandatory requirement with regard to independent directors and whistle-blower policy, the market regulator has now considerably diluted this clause by issuing a master circular which supercedes all earlier ones. Earlier, as part of the mandatory requirement under Clause 49 of LA, SEBI had asserted that independent directors might have tenure, not exceeding in the aggregate, for a period of 9 years on the Board of a company. Had SEBI insisted on the independent directors issue which was an essential ingredient of promoting better governance practices among Indian corporates, many companies would have been forced to remove passive directors appointed by them and bring in new faces to the board.

Likewise, another mandatory requirement for the corporates was to have the whistle blower policy. SEBI’s earlier circular had provided for a whistle blower policy through which a company should establish a mechanism for employees to report to the management concerns about unethical behaviours, actual or suspected fraud, or violation of the company’s code of conduct or ethics policy. This mechanism could also provide for direct access to the chairman of the audit committee in exceptional cases. Once established, the existence of the mechanism may be appropriately communicated within the organisation. The provision of having a whistle-blower policy too has now been made a non-mandatory requirement. In this context, SEBI watchers argue: “It is sad that SEBI buckled under pressure from the intense lobbying by corporates. Some of the promoters are against the whistle-blower policy. This does not suit their working style.” Such fickle-minded approach on the part of the regulator not only brings to the fore its inability to enforce well-intentioned regulations evolved out of considerable experience, thought, and deliberation, but also SEBI could not be believed to promote corporate governance practices with any degree of commitment to the cause.

- The legacy of Nehruvian socialism dies hard: For most of the problems SEBI faces, and with its current positioning and dispensation, it is unable to find solutions to, are part of the legacy of Nehruvian socialism. A regulatory framework that works like an appendage or an extended arm of a government department in a free and a fiercely competitive environment is bound to face serious problems.