2

The Theory and Practice of Corporate Governance

CHAPTER OUTLINE

- The Concept of Corporation

- Theoretical Basis of Corporate Governance

- Agency Theory

- Stewardship Theory

- Stakeholder Theory

- Sociological Theory

- Corporate Governance Mechanisms

- Corporate Governance Systems

- Indian Model of Corporate Governance

- What is “Good” Corporate Governance?

- Obligations to Society at Large

- Obligation to Investors

- Obligation to Employees

- Obligation to Customers

- Managerial Obligation

The Concept of Corporation

No other institution has contributed so much to the growth of market-driven capitalist economies of the world as modern corporations. The Joint Stock Company which is also known as “Corporation” is the nucleus of all business activities in modern economies. Such a company can be easily set up under the Companies Act. The corporation has become the most important industrial unit or business enterprise or a commercial venture. But it is also a fact that all corporations do not enjoy equal measure of power nor are they equal in terms of size and degree of operations. Be it in a developed country such as the US or a developing country such as India, the major portion of capital is in the hands of few giant corporations which are in a position to exercise considerable control over industrial production and its sale.

The definitions of the term “corporation” reflect the perspectives, predelictions and the sensitivity of the people writing them. Lawyers and economists describe the corporation as “a nexus of contracts,” arguing that the corporation is nothing more than the sum of all of the agreements leading to its creation.

No other institution has contributed so much to the growth of market-driven economies as modern corporations. “Corporation” is the nucleus of all business activities in modern economies. Lawyers and economists describe the corporation as “a nexus of contracts,” arguing that the corporation is nothing more than the sum of all of the agreements leading to its creation.

Melvin Aron Eisenberg defines a corporation thus: “The business corporation is an instrument through which capital is assembled for the activities of producing and distributing goods and services and making investments. Accordingly, a basic premise of corporation law is that a business corporation should have as objective the conduct of such activities with a view to enhancing the corporation’s profit and the gains of the corporation’s owners, that is, the shareholders.

According to Chief Justice John Marshall: “A corporation is an artificial being, invisible, intangible, and existing only in the contemplation of the law. Being the mere creature of the law, it possesses only those properties which the charter of its creation confers on it, either expressly or as incidental to its very existence. These acts are supposedly best calculated to effect the object for which it was created. Among the most important properties are immortality, and, if the expression be allowed, individuality; which a perpetual succession of many persons are considered the same, and may act as a single individual.”

What is a Corporate?

In the capitalist economy, the process of capital accumulation that facilitates development of economies by fuelling growth of its various sectors such as industry, agriculture, infrastructure, trade and commerce has become institutionalised by the corporation. The corporation of today has come to replace the sole proprietor of earlier times and tries to maximise its profits and accumulate capital as he did. However, it differs from individual capitalist in two important aspects: (i) The life span of the corporation is much longer, and (ii) it is more rational in decision making by virtue of the fact that it has the benefit of the collective wisdom of the board of directors, and besides, they take decisions using the principles of cost accounting and budget analysis, data collection and processing and managerial consulting.

Though there are numerous definitions of a company, some of which have been quoted earlier, Justice Lindlay’s definition is both lucid and comprehensive. In his words: “By a company is meant an association of many persons, who contribute money or money’ s worth to a common stock and invest it in some trade or business, and who share the profit and loss (as the case may be) arising therefrom. The common stocks so contributed is denoted in money and is the capital of the company. The persons who contribute it, or to whom it belongs, are members. The proportion of capital to which each member is entitled is his share. Shares are always transferable, although the right to transfer them is often more or less restricted.”1

The corporation of today differs from individual capitalist in two important aspects: (i) the life span of the corporation is much longer, and (ii) it is more rational in decision-making by virtue of the fact that it has the benefit of the collective wisdom of the board of directors. Besides, they take decisions using the principles of cost accounting, budget analysis, data collection and processing, and managerial consulting.

A corporation enjoys some privileges and is also bound by responsibilities, indicated in the following definition: A corporation is an association of persons recognised by the law as having a collective personality. The corporation can act as if it were distinct from its members; it has “perpetual succession” and a common seal. It can therefore CONTRACT quite freely—it can also be fined, but it obviously cannot be sent to prison or incur penalties which can only be applied to individuals.2

A corporation is an association of persons recognised by the law as having a collective personality. The corporation can act as if it were distinct from its members, it has “perpetual succession” and a common seal. Characteristics of a corporation are incorporated association, artificial legal existence, perpetual existence, extensive membership, separation of management from ownership, limited liability and transferability of shares.

From the above definitions, the following characteristics of a corporation emerge:

- Incorporated association: A corporation is legally required to be incorporated or registered under the prevalent Companies Act of the country.

- Artificial legal existence: A joint stock company, also referred to as a corporate or corporation, is entitled to a separate legal existence, apart from the persons composing it. In the eyes of law, it is a separate legal person and has rights and duties as any natural person has, though it has no political or civic rights. The Supreme Court of India has defined the legal status of a company thus: “The corporation in law is equal to a natural person and has a legal entity of its own. The entity of the corporation is entirely separate from that of its shareholders; it bears its own name and has a seal of its own; its assets are separate and distinct from those of its members; it can sue and can be sued exclusively for its own purpose; the liability of the members or shareholders is limited to the capital invested by them, similarly the creditors of the members have no right to the assets of the corporation.”3

- Perpetual existence: The life of a corporation is not contingent on the lives of its members. Its life does not end with the exit, retirement, lunacy, insolvency or death of any or all directors or shareholders. The perpetual existence of the company is preserved by the provision of transferability of shares. A company’ s existence depends on law. Law creates a company and law only can dissolve it.

- Common seal: Since a company is an artificial person, it cannot sign documents for itself. It functions through natural persons who are usually directors. However, a company having a legal entity is bound by those documents that are signed by the company’s CEO and carry the seal of the company. Use of seal is a legal requirement. Under the Indian Companies Act, any document bearing the common seal of the company and duly witnessed by at least two directors of the company is legally binding on the company.

- Extensive membership: There is no maximum limit to the membership of a joint stock company. As the purpose of a company is to raise large capital, shares are sold to a large number of persons. Even men of small means can become part-owners of a company by subscribing to its share capital. Companies such as Reliance have millions of shareholders scattered not only through the breadth and width of the country but also abroad.

- Separation of management from ownership: The divorce of ownership from the actual management of the company is what often causes misgovernance of companies. The shareholders, scattered as they are, are not in a position to take part in the day-to-day administration of their company. They cannot also bind the company by their acts. The actual management is delegated to the board of directors elected by them, who in turn, take major policy decisions and hand over the daily administration to salaried managers. These men, motivated as they are by a desire to show profit, may act capriciously and cause misgovernance.

- Limited liability: Although law provides for creating a company with unlimited liability or a company by limited guarantee, the companies with limited liability are most common. Limited liability implies that the liability of the shareholders is limited to the amount unpaid on their shares irrespective of the obligations of the company. This means that even in cases when a company suffers heavy losses and incurs large debt obligations, the personal property of the shareholders cannot be seized for repaying the debts of the company provided shares are fully paid. This limitation of liability eliminates the “risk” of investment and has stimulated investment in all kinds of large industries and huge commercial enterprises and has paved the way for the growth of the material civilisation of the world. It has also encouraged large public savings even among the middle and the lower middle classes.

- Transferability of shares: Shareholders of a public limited company can freely transfer their shares to whomsoever they like without seeking permission from the company. Thus a member of a public company can transfer his holdings without the consent of other members. This imparts liquidity to the investment made in the shares of the company. Shares, like commodities, can be bought and sold in a market known as stock exchange. This facility has also stimulated investments. Capital which is locked up in fixed assets of a company has been made liquid and realisable by transferability of shares. But for this facility, large amount of capital which the present day corporates need cannot be mobilised.

The Concept of Governance

The concept of “governance” is as old as human civilisation. Simply stated, “governance” means the process of decision-making and the process by which decisions are implemented (or not implemented). Governance can be used in several contexts such as corporate governance, international governance, national governance and local governance.

Since governance is the process of decision-making and the process by which decisions are implemented, an analysis of governance focusses on the formal and informal players involved in decision-making and implementing the decisions made and the formal and informal structures that have been set in place to arrive at and implement the decision.

Government is one of the players in governance. Others involved in governance vary depending on the level of government that is under discussion. In rural areas, for example, other players may include influential landlords, associations of peasant farmers, cooperatives, NGOs, research institutes, religious leaders, finance institutions, political parties, the police, etc. The situation in urban areas is much more complex and includes the urban elite, decision-makers at various levels, both government and the private sector media, elected representatives, government officers of various levels, the middle class, the urban poor, NGOs and interested groups, small scale entrepreneurs, trade unions and so on. At the national level, in addition to the above players, media, lobbyists, international donors, multi national corporations, etc. may play a role in decision-making or in influencing the decision-making process.

“Governance” is as old as human civilisation. Simply stated, it means the process of decision-making and the process by which decisions are implemented (or not implemented). An analysis of governance focusses on the formal and informal players involved in decision-making and implementing the decisions made.

All players other than government and the military are grouped together as part of the “civil society”. In some countries, in addition to the civil society, organised crime syndicates also influence decision-making, particularly in urban areas and at the national level.

Similarly, formal government structures are one of the means by which decisions are arrived at and implemented. At the national level, informal decision-making structures, such as “kitchen cabinets” or informal advisors may exist. In urban areas, organised crime syndicates such as the “land mafia” may influence decision-making. In some rural areas, local powerful families may make or influence decision-making. Such informal decision-making is often the result of corrupt practices or leads to corrupt practices.

Theoretical Basis of Corporate Governance

There are four broad theories to explain and elucidate corporate governance. These are: (i) Agency Theory (ii) Stewardship Theory (iii) Stakeholder Theory and (iv) Sociological Theory.

Agency Theory

Recent thinking about strategic management and business policy has been influenced by agency cost theory, though the roots of the theory can be traced back to Adam Smith who identified an agency problem (managerial negligence and profusion) in the joint stock company. The fundamental theoretical basis of corporate governance is agency costs. Shareholders are the owners of any joint stock, limited liability company, and are the principals of the same. By virtue of their ownership, the principals define the objectives of a company. The management, directly or indirectly selected by shareholders to pursue such objectives, are the agents. While the principals generally assume that the agents would invariably carry out their objectives, it is often not so. In many instances, the objectives of managers are at variance from those of the shareholders. For instance, a chief executive may want to increase his managerial empire and personal stature by using the company’s funds to finance an unrelated diversification, which could reduce long term shareholder value. The shareholders and other stakeholders of the company, may not be able to counteract this because of inadequate disclosure about such a decision and because the principals may be too scattered or even not motivated enough to effectively block such a move. Such mismatch of objectives is called the agency problem; the cost inflicted by such dissonance is the agency cost. The core of corporate governance is designing and putting in place disclosures, monitoring, “oversight” and corrective systems that can align the objectives of the two sets of players as closely as possible and, hence, minimise agency costs.

In the modern corporation, where share ownership is widely held, managerial actions depart from those required to maximise shareholder returns. In agency theory terms, the owners are the principals and the managers are the agents and there is an agency loss, which is the extent to which returns to the owners fall. Agency theory specifies mechanisms that reduce agency loss.

The main thrust of the agency theory runs like this. In the modern corporation, in which share ownership is widely held, managerial actions depart from those required to maximise shareholder returns. In agency theory terms, the owners are principals and the managers are agents and there is an agency loss which is the extent to which returns to the residual claimants, the owners, fall below what they would be if the principals, the owners themselves, exercised direct control of the corporation. Agency theory specifies mechanisms which reduces agency loss. These include incentive schemes for managers which reward them financially for maximising shareholder’s interests. Such schemes typically include plans whereby senior executives obtain shares, perhaps at a reduced price, thus aligning financial interests of executives with those of shareholders. Other similar schemes tie executive compensation and levels of benefits to shareholders, returns and have part of executive compensation deferred to the future to reward long-run value maximisation of the corporation and deter short-run executive action which harms corporate value.

Problems with the Agency Theory

Total control of management is neither feasible nor required under this theory. The underlying assumption in the trade-off that shareholders make on employing agents is that they must accept a certain level of self-interested behaviour in delegating responsibility to others. The objective of agency theory is to check the abuse in this trade-off, but its limited success raises the question of its utility as a theoretical model to promote corporate governance. Besides, in agency theory the assumption is with the complexities of investor-board relationship in large organisations, shareholders should have correct and adequate information to wield effective control. Equity investors rarely get these and besides they rarely make clear their exact target returns, and yet delegate authority to meet the target. It is also to be understood that in terms of controls, equity investors hardly have sanctions over boards. Instead, they have to rely on self-regulation to ensure that an orderly house is maintained.

There are two broad mechanisms that help reduce agency costs and hence improve corporate performance through better governance: (i) fair and accurate financial disclosures, and (ii) efficient and independent board of directors.

There are two broad mechanisms that help reduce agency costs and hence, improve corporate performance through better governance. These are:

- Fair and accurate financial disclosures: Financial and non-financial disclosures, which relate to the role of the independent, statutory auditors appointed by shareholders to audit a company’s accounts and present a “true and fair” view of the financial health of the corporation. Indeed, the quality and independence of statutory auditors are fundamental to achieve the purpose. While it is the job of the management to prepare the accounts, it is the responsibility of the statutory auditors to scrutinise such accounts, raise queries and objections (if the need arises), arrive at a true and fair view of the financial position of the company, and report their independent findings to the board of directors and, through them, to the shareholders and investors of the company.

A company that discloses nothing can do anything. Improving the quality of financial and non-financial disclosures not only ensures corporate transparency among a wide group of investors, analysts and the informed intelligentsia, but also persuades companies to minimise value-destroying deviant behaviour. This is precisely why law insists that companies prepare their audited annual accounts, and that these be provided to all shareholders and is deposited with the Registrar of companies. This is also why a good deal of effort in global corporate governance reform has been directed to improving the quality and frequency of disclosures.

- Efficient and independent board of directors: A joint-stock company is owned by the shareholders, who appoint directors to supervise management and ensure that it does all that is necessary by legal and ethical means to make the business grow and maximise long-term corporate value. Directors are fiduciaries of the shareholders, not of the management. They are accountable only to the shareholders. “Independence” has of late become a critical issue in determining the composition of any board.

Stewardship Theory

The stewardship theory of corproate governance discounts the possible conflicts between corporate management and owners and shows a preference for a board of directors made up primarily of corporate insiders. This theory assumes that managers are basically trustworthy and attach significant value to their own personal reputations. The market for managers with strong personal reputations serves as the primary mechanism to control behaviour, with more reputable managers being offered higher compensation packages. Financial reporting, disclosure and auditing are still important mechanisms, but there is a fundamental presumption that these mechanisms are needed to confim managements’ inherent trustworthiness.

The stewardship theory assumes that managers are basically trustworthy and attach significant value to their own personal reputations. It defines situations in which managers are stewards whose motives are aligned with the objectives of their principles. A steward’s behaviour will not depart from the interests of his/her organisation. Control can be potentially counterproductive, because it undermines the pro-organisational behaviour of the steward by lowering his/her motivation.

Stewardship theory can be reduced to the following basics:

- The theory defines situations in which managers are not motivated by individual goals, but rather they are stewards whose motives are aligned with the objectives of their principles.

- Given a choice between self-serving behaviour and pro-organisational behaviour, a steward’ s behaviour will not depart from the interests of his/her organisation.

- Control can be potentially counterproductive, because it undermines the pro-organisational behaviour of the steward, by lowering his/her motivation.

This emphasis on the responsibility of the board to shareholders in the Anglo-Saxon model of corporate governance in terms of stewardship and trusteeship is nowhere better articulated than in the Canadian guidelines. It is stated therein: “Stewardship refers to the responsibility of the board to oversee the conduct of the business and to supervise management which is responsible for the day-to-day conduct of the business. In addition, as stewards of the business, the directors function as the catch-all to ensure no issue affecting the business and affairs of the company falls between cracks.” Similar views, though differently told, predominate in corporate governance guidelines of many countries of the world.

The greatest barrier, however, to the adoption of stewardship mechanisms of governance lies in the risk propensity of principals. Risk taking owners will assume that executives are pro-organisation and favour stewardship governance mechanisms. Where executives, investors cannot afford to extend board power, agency costs are effective insurance against the self-interest behaviours of agents.

The responsibility of the board to shareholders in terms of stewardship and trusteeship cannot be overemphasised. These concepts of stewardship and trusteeship are not new. The sacred scriptures, both in India and Christendom, emphasise the almost filial relationships between the rulers and the ruled. Gandhiji too elaborated the concept of trusteeship to make Indian industrialists better understand and appreciate their roles and responsibilities towards their employees.

Of course, these concepts of stewardship and trusteeship are not new. The sacred scriptures, both in India and Christendom, emphasise the almost filial relationships between the rulers and the ruled. Gandhiji too elaborated the concept of trusteeship to make Indian industrialists better understand and appreciate their roles and responsibilities towards their employees. It is said in many oriental societies including Japan, that an employer has been ordained by God to act as His trustee to own and administer assets for the benefit of his employees.

Though the Agency and Stewardship Theories have something in common, there are certain basic differences. The tables set out below summarise the main differences between the two theories.4

Davis, Schoorman and Donaldson (1997) state that the owners-managers relationship depends on the behaviour adopted respectively by them. Managers choose to act as agents or as stewards according to certain personal characteristics and their own perceptions of particular situational factors. Principals choose to create a relationship of one type or the other depending on their perceptions of the same situational factors and of their managers’ psychological mechanisms. The following tables set out these variables and the differences between the two theories.

TABLE 2.1 Behavioural differences

| Agency Theory | Stewardship Theory |

|---|---|

| Managers act as agents | Managers act as stewards |

| Governance approach is materialistic | Governance approach is sociological and psychological |

| Behaviour pattern is • individualistic • opportunistic • self-serving |

Behaviour pattern is • collectivistic • pro-organisational • trustworthy |

| Managers are motivated by their own objectives | Managers are motivated by the principal’s objectives |

| Interests of the Managers and principals differ | Interests of the managers and principals converge |

| The role of the management is to monitor and control | The role of the management is to faclitate and empower |

| Owners’ attitude is to avoid risks | Owners’ attitude is to take risks |

| Principal-Manager relationship is based on control | Principal-Manager relationship is based on trust |

Adapted from “Development of Corporate Governance System: Agency Theory Versus Stewardship Theory in Welsh Agrarian Coorperative Societies”, by Dr. Alfonso Vargas Sanchez.

TABLE 2.2 Psychological mechanisms

| Agency Theory | Stewardship Theory |

|---|---|

| Motivation revolves around • lower order needs •Extrinsic needs |

Motivation revolves around • Higher order needs • Intrinsic needs |

| Social comparison is between compatriots | Social comparison is between principals |

| There is little attachment to the company | There is great attachment to the company |

| Power rests with the institution | Power rests with the personnel |

Adapted from “Development of Corporate Governance System: Agency Theory Versus Stewardship Theory in Welsh Agrarian Coorperative Societies”, by Dr. Alfonso Vargas Sanchez.

TABLE 2.3 Situational mechanisms

| Agency Theory | Stewardship Theory |

|---|---|

| Management philosophy is control oriented | Management philosophy is involvement oriented |

| To deal with increasing uncertainty and risk, the theory advocates exercise of • greater controls • more supervisions |

To deal with increasing uncertainty and risk, the theory advocates exercise of • training and empowering people • making jobs more challenging and motivating |

| Risk orientation is done through a system of control | Risk orientation is done through trust |

| Time frame is short term | Time frame is long term |

| The objective is cost control | The objective is improving performance |

| Cultural differences revolve around • individualism • large power distance |

Cultural differences revolve around • collectivism • small power distance |

Adapted from “Development of Corporate Governance System: Agency Theory Versus Stewardship Theory in Welsh Agrarian Coorperative Societies”, by Dr. Alfonso Vargas Sanchez.

Shareholder Versus Stakeholder Approaches

While studying theories of corporate governance, it is common to distinguish between shareholder and stakeholder approaches. Shareholder approaches argue that corporations have a limited set of responsibilities, which primarily consist of obeying the law and maximising shareholder wealth. The basic argument is that corporations, by focussing on shareholder interests maximise societal utility. The logic of this position goes back to the ability of the shareholder model to maximise utility, however, is tenuous in that it is based on the assumption of perfect competition. To the extent that the conditions of perfect competition are not in place, the argument falters. More specifically, as deviations from the conditions of perfect competition increase (e.g. imperfect markets, incomplete contracts, information asymmetries), after a certain point, corporations will not be maximising societal utility by merely pursuing shareholder interests. The shareholder approach is logically most compatible with the Anglo-American model of corporate governance.

In contrast to shareholder approaches, stakeholder models of corporate governance argue that those responsible for the governance of the corporation have responsibilities to parties other than shareholders and that, any fiduciary obligations owed to shareholders to maximise profits might be subject to the constraint of respecting obligations owed to such stakeholders.

Stakeholder Theory

The stakeholder theory of corporate governance has a lengthy history that dates back to 1930s. The theory represents a synthesis of economics, behavioural science, business ethics and the stakeholder concept. The history and the range of disciplines that the theory draws upon has led to large and diverse literature on stakeholders. In essence, the theory considers the firm as an input-output model by explicitly adding all interest groups—employees, customers, dealers, government and the society at large—to the corporate mix.

The theory is grounded in many normative theoretical perspectives including the ethics of care, the ethics of fiduciary relationships, social contract theory, theory of property rights, theory of the stakeholders as investors, communitarian ethics, critical theory, etc. While it is possible to develop stakeholder analysis from a variety of theoretical perspectives, in practice much of stakeholder analysis does not firmly or explicitly root itself in a given theoretical tradition, but rather operates at the level of individual principles and norms for which it provides little formal justification. Insofar as stakeholder approaches uphold responsibilities to non-shareholder groups, they tend to be in some tension with the Anglo-American model of corporate governance, which generally emphasises the primacy of “fiduciary obligations” owed to shareholders over any stakeholder claims.

The stakeholder theory is grounded in many normative, theoretical perspectives including ethics of care, the ethics of fiduciary relationships, social contract theory, theory of property rights, and so on. Stakeholder theory is often criticised, mainly because it is not applicable in practice by corporations.

The stakeholder theory is often criticised, more often than not as “woolly minded liberalism”, mainly because it is not applicable in practice by corporations. Another cause for criticism is that there is comparatively little empirical evidence to suggest a linkage between stakeholder concept and corporate performance. But there are considerable theoretical arguments favouring promotion of stakeholders’ interests. Managers accomplish their organisational tasks as efficiently as possible by drawing on stakeholders as a resource. This is in effect a “contract” between the two, and one that must be equitable in order for both parties to benefit.

Criticisms of the Stakeholder Theory

The major problem with the Stakeholder Theory stems from the difficulty of defining the concept. Who really constitutes a genuine stakeholder? There is an expansive list suggested by authors of the theory, ranging from the most bizarre to include terrorists, dogs and trees, to the least questionable such as employees and customers. Some writers have suggested that any one negatively affected by corporate actions might reasonably be included as stakeholder, and across the world this might include political prisoners, abused children, minorities and the homeless. However, a more seriously conceived and yet contested list of stakeholders would generally include employees, customers, suppliers, the government, the community, assorted activist or pressure groups, and of course, shareholders. Some writers on the theory opine that where there are too many stakeholders, “in order to clarify and ease the burden it places upon directors” it is better to categorise them as primary and secondary stakeholders. Clive Smallman in his article “Exploring Theoretical Paradigms in Corporate Governance” says: “The case for including both the serious claimants and the more flippant are rooted in business ethics, in managerial morality and in best practice in business strategy. However, whilst the inclusion of a wide range of interested parties may be well-intentioned, in practice if directors (as agents) attempt to serve too many principals they will fail to satisfy those who have a genuine claim on an organisation.”

Further, Clive Smallman points out to another problem that stems from the stakeholder theory. “Relating to the range and diversity of stakeholders, some critics also accuse stakeholder theory of being “superfluous”, by which they mean that the intent of the theory is better achieved by relying on the hand of management to deliver social benefit where it is required.”

In the assessment of Clive Smallman, “the stakeholder model also stands accused of opening up a path to corruption and chaos; since it offers agents the opportunity to divert wealth away from shareholders to others, and so goes against the fiduciary obligations owed to shareholders (a misappropriation of resources)“.5 Thus, the stakeholder model of corporate governance leads to corrupt practices in the hands of managements with a wide option and also to chaos, as it does not differ much from the agency model, while increasing exponentially the number of principals the agents have to tackle.

Sociological Theory

The sociological approach to the study of corporate governance has focussed mostly on board composition and the implications for power and wealth distribution in society. Problems of interlocking directorships and the concentration of directorships in the hands of a privileged class are viewed as major challenges to equity and social progress. Under this theory, board composition, financial reporting, disclosure and auditing are necessary mechanisms to promote equity and fairness in society.

The sociological theory has focussed mostly on board composition and wealth distribution. Under this theory, board composition, financial reporting, and disclosure and auditing are of utmost importance to realise the socio-economic objectives of corporations.

Corporate Governance Mechanisms

Why Corporate Governance?

As has been pointed out earlier, the joint-stock, limited liability company has become the preferred organisation for running business throughout the world. It has proved its worth in providing employment, generating wealth, and contributing to economic and social development. The original concept of the company, which stems from the mid-nineteenth century, has proved immensely innovative, elegantly simple and highly successful.

In the limited liability company, the business is incorporated as an independent legal entity, separate from its owners, whose liability for its debts is limited to the amount of equity capital they have agreed to subscribe to. In law, the company has many of the rights of a legal person—to buy and sell, to own assets, to incur debts, to employ, to contract and to sue and be sued. The company has a life of its own different from those of its innumerable owners. Although this does not guarantee perpetuity, it does give the company an existence independent of the life of the proprietors, who can transfer their shares to others.

Companies need to be governed as well as managed. Corporate governance is concerned with this need. The board of directors is central and its structure and processes are fundamental; so are the board’s relationships with the company’s shareholders, regulators, auditors, top management and other legitimate stakeholders.

Everywhere ownership is the basis of power. The shareholders nominate and elect directors, who run the enterprise on their behalf. The directors are the stewards of the resources of the business and demonstrate their accountability to the shareholders, in the form of regular financial account and directors’ reports. The shareholders also appoint independent auditors to report that these accounts show a true and fair view of the state of affairs of the company. Regular shareholders’ meetings provide an opportunity for the directors to report and clarify shareholders’ doubts or answer their questions.

Companies need to be governed as well as managed. Corporate governance is concerned with this need. The board of directors is central and its structure and processes are fundamental; so are the board’s relationships with the company’s shareholders, regulators, auditors, top management and other legitimate stakeholders.

There is no uniform scope or content of corporate governance. Some focus on the link between shareholders and the company; some concentrate on the formal structures of the board, codes of board practice and corporate effectiveness; yet others believe the focus should be on the social responsibilities of corporations to a wider set of stakeholders. Corporate governance is a useful umbrella term to cover the exercise of power over and within the company, for the good of all concerned.

Contemporary Corporate Governance Situation

In the original concept of the company, the basis of corporate governance was shareholder democracy. Shareholders were relatively few and close enough to the board of directors to exercise a degree of control. Indeed in millions of smaller, tightly owned companies around the world that is still the situation today.

In many countries, shares of public companies are now held by diverse shareholders: some by private individuals, some by institutional investors such as banks, pension funds and insurance companies, and some by other companies, who might have business relationships with the company. These days, ownership structures of major public companies around the world are complex.

But for major corporations, particularly those which have their shares listed on a stock exchange, the governance situation has practically changed. In many countries, the shares of public companies are now held by diverse shareholders—some by private individuals, some by institutional investors such as banks, pension funds and insurance companies, and some by other companies, who might have business relationships with the company. Ownership structures of major public companies around the world these days are often complex. The first step in understanding the reality of corporate governance in a given company is to understand the ownership structure and, hence, the potential to exercise power and influence over that company.

In the past, most institutional investors ignored their management or rights as shareholders, preferring to sell their shares rather than getting involved in challenging corporate performance. However, a trend in recent years has been for some institutional investors, particularly in the United States, Great Britain and Australia, to become pro-active, calling for boards to produce better corporate performance, questioning directors’ remuneration, and calling for greater transparency on company finances and more accountability from directors. Indeed, one US institutional investor—CalPERS (the Californian Public Employees Retirement System) has produced corporate governance guidelines for companies in which they have invested in France, Germany, Japan and the US.

Growing Awareness and Societal Responses

The growing awareness of corporate governance around the world has been reflected in a plethora of official reports on the subject. These include the American Law Institute Report (1992), the Cadbury (1992), Greenbury (1995) and Hampel (1998) reports from the UK, the Hilmer report (1993) in Australia, the Vienot report (1995) in France, the King report (1995) from South Africa, the OECD report in 1998, as well as studies in Hong Kong, Singapore, Malaysia and elsewhere. In India, the Corporate Governance code was first laid out by the Confederation of Indian Industry (CII) in the wake of interest generated by the Cadbury Committee Report, followed by an in-depth study made by the Associated Chamber of Commerce (ASSOCHAM) and the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI). SEBI appointed Kumar Managalam Birla Committee and adopted its report in mid-2000. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) also constituted its own committee to study problems and issues relating to corporate governance from the perspective of the banking sector. Based on the inputs from these committees, the Department of Company Affairs amended the Companies Act in December 2000 to include corporate governance provisions which became applicable to all Indian companies effective from 1 April 2001.

Many of the official reports provide a code of best practices in corporate governance, detailing expectations on matters such as board structure, audit and audit committees, transparency in financial accounting and director accountability. Some institutional investors, particularly in the United States have also called for codes of corporate governance practices; the best known being the CalPERS’ Global Principles of Corporate Governance. Increasingly, to obtain access to international equity finance, companies around the world have to respond to the corporate governance requirements of these codes.

Meanwhile the debate on companies’ responsibilities to other stakeholders, other than their own shareholders, has been increasing in the US and UK; the Royal Society of Arts’ (RSA) inquiry in the UK produced a study called “Tomorrow’s Company” (1995), which suggested responsibilities to a wider range of stakeholders.

Further, most major companies now operate through group structures of wholly-owned subsidiary companies, partly-owned subsidiaries in which other external parties have a minority equity interest and associated companies in which the holding company has a significant, but not dominant holding. In addition, the globalisation of business dealings has meant that major companies frequently engage in a variety of joint venture and other strategic alliances with other companies. The second step in understanding the reality of corporate governance in a given company is to understand the network of ownership throughout the group, identifying minority interests in group companies and partner interests in joint venture companies. In India we have several such group structures of companies belonging to family-owned entities such as the Tata’s, Birla’s, TVS’, Murugappa’s etc., which are increasingly adopting corporate governance practices in all of their group companies.

Other reasons for the growing concern about corporate governance include changing societal expectations about the social responsibility of private sector companies, the attention being paid to more participatory political systems at national government level and the potential of global communications and information technology to spread ideas and to provide information on companies. The past decade has also seen a massive increase in academic research in corporate governance. At the heart of the exercise of governance over companies is the governing body, typically called the board of directors. It is vital to appreciate the role of the Board.

Corporate Governance Systems

The board of directors seldom appears on the management organisation chart yet it is the ultimate decision making body in a company. The role of management is to run the enterprise while the role of the board is to see that it is being run well and in the right direction.

Management always operates as a hierarchy. There is an ordering of responsibility, with authority delegated downwards through the organisation and accountability upwards to the ultimate boss. By contrast, the board members need to work together as equals, reaching agreement by consensus or, if necessary, by voting. In almost all dispensations each director bears the same duties and responsibilities under the law. A useful way of depicting the interaction between management and the board is to present the board as a circle superimposed on the hierarchical triangle of management.

The role of the management is to run the enterprise while the role of the board is to see that it is being run well and in the right direction. Corporate governance systems vary around the world. Scholars tend to suggest three broad versions (i) The Anglo-American model; (ii) The German model and (iii) The Japanese model.

This model can be applied to the governance of any corporate entity, private or public, profit oriented or service-based organisation. The circle and triangle model mentioned earlier is a powerful analytical tool.

Corporate governance systems vary around the world. Scholars tend to suggest three broad versions: (i) The Anglo-American Model; (ii) The German Model; and (iii) The Japanese Model.

The Anglo-American Model

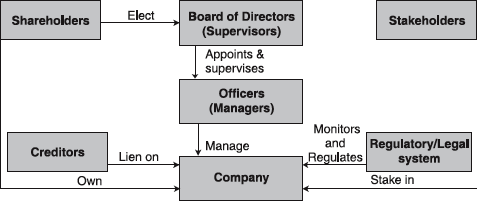

This is also known as unitary board model, as illustrated in Figure 2.1 in which all directors participate in a single board comprising both executive and non-executive directors in varying proportions. This approach to governance tends to be shareholder-oriented. It is also called the ‘Anglo-Saxon’ approach to corporate governance, being the basis of corporate governance in America, Britain, Canada, Australia and other commonwealth countries including India.

In the Anglo-American model, all directors participate in a single board comprising both executive and non-executive directors in varying proportions. ‘Anglo-Saxon’ approach to corporate governance is the basis of corporate governance in America, Britain, Canada, and Australia.

The major features of the Anglo-Saxon or Anglo-American model of corporate governance are as follows:

- The ownership of companies is more or less equally divided between individual shareholders and institutional shareholders.

- Directors are rarely independent of management.

- Companies are typically run by professional managers who have neligible ownership stakes. There is a fairly clear separation of ownership and management.

- Most institutional investors are reluctant activists. They view themselves as portfolio investors interested in investing in a broadly diversified portfolio of liquid securities. If they are not satisfied with a company’s performance, they simply sell the securities in the market and quit.

- The disclosure norms are comprehensive, the rules against insider trading tight, and the penalties for price manipulations stiff, all of which provide adequate protection to the small investor and promote general market liquidity. Incidentally, they also discourage large investors from taking an active role in corporate governance.

Figure 2.1 The Anglo-American Model

German Model

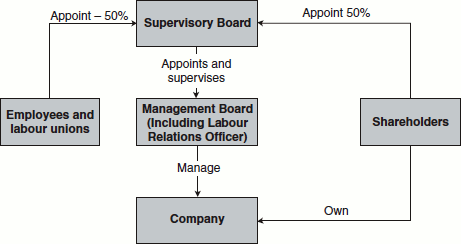

In this model, also known as the two-tier board model, corporate governance is exercised through two boards, in which the upper board supervises the executive board on behalf of stakeholders. This approach to governance is typically more societal-oriented and is sometimes called the Continental European approach, being the basis of corporate governance adopted in Germany, Holland, and to an extent, France.

Corporate governance in the German model is exercised through two boards, in which the upper board supervises the executive board on behalf of stakeholders and is typically societal-oriented. In this model, although shareholders own the company, they do not entirely dictate the governance mechanism. They elect 50 per cent of members of supervisory board and the other half is appointed by labour unions, ensuring that employees and labourers also enjoy a share in the governance. The supervisory board appoints and monitors the management board.

In this model although the shareholders own the company, they do not entirely dictate the governance mechanism. As shown in Figure 2.2, shareholders elect 50 per cent of members of supervisory board and the other half is appointed by labour unions. This ensures that employees and labourers also enjoy a share in the governance. The supervisory board appoints and monitors the management board. There is a reporting relationship between them, although the management board independently conducts the day-to-day operations of the company.

The Japanese Model

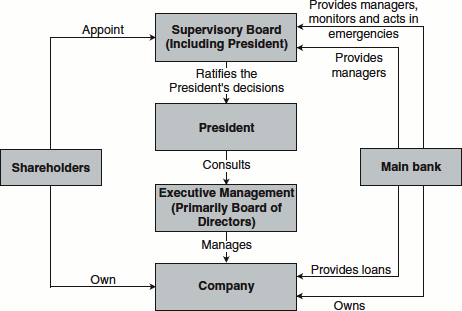

This is the business network model, which reflects the cultural relation-ships seen in the Japanese keiretsu network, in which boards tend to be large, predominantly executive and often ritualistic. The reality of power in the enterprise lies in the relationships between top management in the companies in the keiretsu network. approach bears some comparison with Korean chaebol.

Figure2.2 The German Model

In the Japanese model (Figure 2.3), the financial institution plays a crucial role in fovernance. The shareholders and the main bank together appoint the board of directors and the presdent.

The distinctive features of the Japanese corporate governance mechanism are as follows:

- The president who consults both the supervisory board and the executive management is included.

- Importance of the lending bank is highlighted.

Figure 2.3 The Japanese Model

Common Features in the German and Japanese Models

Despite some differences among the German and Japanese models of corporate governance, there are certain significant features to justify their being bracketed together. Their distinctive features are as follows:

- Banks and financial institutions have substantial stakes in the equity capital of companies. Besides, cross-holding among groups of firms is common in Japan.

- Institutional investors in both the countries view themselves as long term investors. They play a fairly active role in corporate managements.

- The disclosure norms are not very stringent, checks on insider trading are not very comprehensive and effective, and the emphasis on liquidity is not high. All these factors lead to the efficiency of the capital market.

- There is hardly any system of corporate control in these countries; mergers and take-overs are rare occurrences.

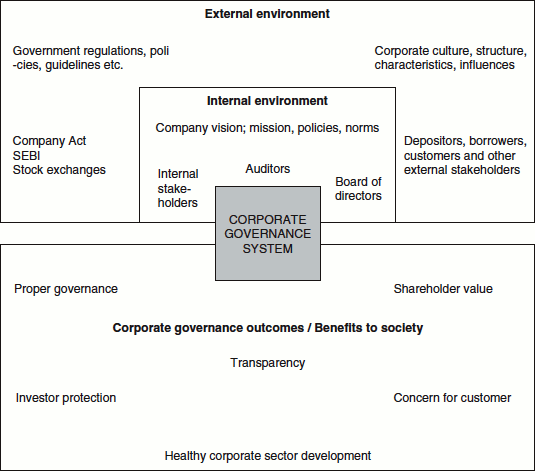

Indian Model of Governance

The Indian corporates are governed by the Company’s Act of 1956 that follows more or less the UK model. The pattern of private companies is mostly that of closely held or dominated by a founder, his family and associates. Figure 2.4 illustrates how the corporate governance system works in India.

Indian corporates are governed by the Company’s Act of 1956 which follows more or less the UK model. The pattern of private companies is mostly that of closely held or dominated by a founder, his family and associates. India has adopted the key tenets of the Anglo-American external and internal control mechanism after economic liberalisation.

Figure 2.4 Indian Corporate Governance Model

Available literature on corporate governance and the way companies are structured and run indicate that India shares many features of the German Japanese model, but of late, recommendations of various committees and consequent legislative measures are driving the country to adopt increasingly the Anglo-American model. In terms of the legislative mechanisms, Indian government and industry constituted three committees to study corporate governance practices in the country and suggest measures for improvement based on what has globally recognised as “best practices”. Significantly, most of the recommendations of the three committees—the SEBI-appointed Kumar Mangalam Birla Committee (2000), the government-appointed Naresh Chandra Committee(2003) and the SEBI’s Narayana Murthy Committee are remarkably similar to those of England’s Cadbury Committee and America’s Sarbanes-Oxley Act, in terms of their approaches and recommendations.

The thrust of the legislative reforms suggested by these committees and subsequent legislative actions adopted, centre around the strengthening of external governance mechanisms. “A key area here includes greater transparency and independent scrutiny of corporate accounts that are made available to investors. This is in line with the Anglo-American model where shareholder influence through the exit option which is contingent upon reliable and accurate information provided by companies. Institutional reforms, including a strengthening of oversight committees and the development of a serious fraud office, are further evidence of the drive to seek for external monitoring of corporate affairs. “In terms of reforms to internal mechanisms such as boards of directors, it is notable that again the recommendations are centred on Anglo-American practice, namely, a greater role for non-executive directors (NEDs) and the curtailment of interlocking directorates.”6

Further, experts point out that India has adopted the key tenets of the Anglo-American external and internal control mechanisms, in the wake of economic liberalisation and its integration into the global economy. “This is evident especially in the realm of the legislative framework where Indian policy-makers have taken their cue from the UK and US committees and their recommendations. Furthermore, a small, albeit high profile group of companies have voluntarily adopted Anglo-American protocols in their bid to successfully raise capital from international markets.”7 Thus corporate governance developments in India in recent years show a paradigm shift from the German/Japanese model to the Anglo-American model.

There are primary distinctions between the three broad models of corporate governance, and within them the actual practices adopted by companies vary considerably. There is not a single preferred model or set of corporate governance mechanisms. Moreover, ideas and practices are evolving fast in many countries. Indeed, given the high calibre directors with relevant experience, appropriate Board leadership and a shared vision for the company’s future, each of the models can prove effective, provided they are consistent with the overall corporate governance infrastructures in the countries concerned.

These various governance systems form a package of overall corporate control in each company law jurisdiction. It is vital to see the package as a whole. There has to be an integrated harmony between state legislation and regulatory infrastructure, stock market regulation and corporate self-regulation. Moreover, the overall corporate governance package has to be consistent with the way the business is done and the reality of relationships in that culture.

What is “Good” Corporate Governance?

Recently the terms “governance” and “good governance” are being increasingly used in development literature. Bad governance is being recognised now as one of the root causes of corrupt practices in our societies. Major donors, institutional investors and international financial institutions provide their aid and loans on the condition that reforms that ensure “good governance” are put in place by the recipient nations. As with nations, corporations too are expected to provide good governance to benefit all their stakeholders. At the same time, good corporates are not born, but are made by the combined efforts of all stakeholders, which include shareholders, board of directors, employees, customers, dealers, government and the society at large. Law and regulation alone cannot bring about changes in corporates to behave better to benefit all concerned. Directors and management, as goaded by stakeholders and inspired by societal values, have a very important role to play. The company and its officers, who, inter alia, include the board of directors and the officials, especially the senior management, should strictly follow a code of conduct, which should have the following desiderata:

Bad governance is being recognised now as one of the root causes of corrupt practices in our societies. Institutional investors and international financial institutions provide their aid and loans on the condition that reforms that ensure good governance are put in place by recipients. Good corporates are not born, but are made by the combined efforts of all stakeholders, board of directors, government and the society at large.

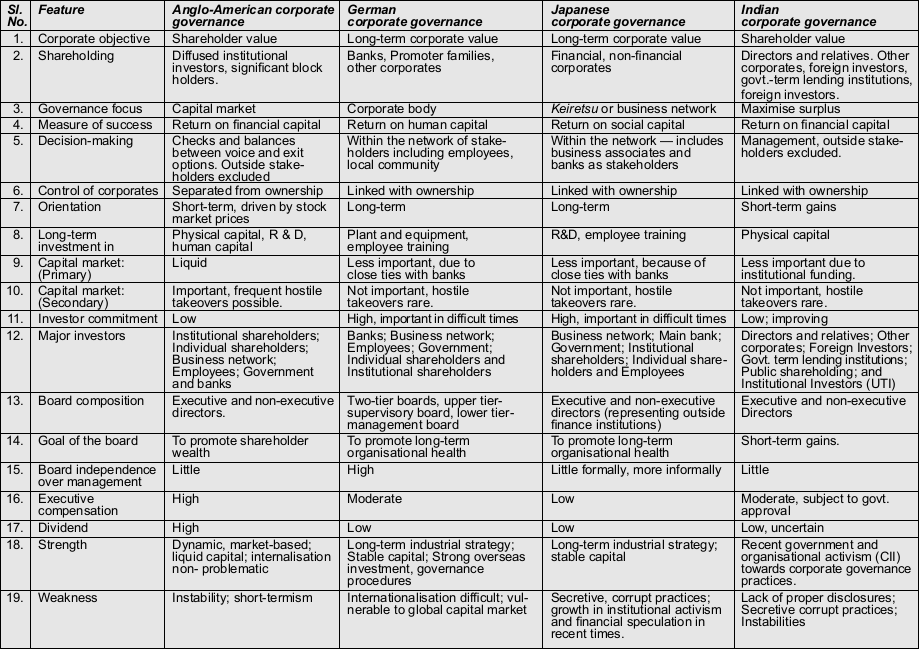

TABLE 2.4 Corporate governance practices—An international comparison

Sources:

- Corporate Governance, The Indian Scenario by Vasudha Joshi, Foundation Books, pp. 124 and 125.

- Large Shareholder Activism in Corporate Governance in Developing Countries: Evidence from India, by Jayati and Subrata Sarkar, International Review of Finance, September 2000, Vol.1, Issue 3.

Obligation to Society at Large

A corporation is a creation of law as an association of persons forming part of the society in which it operates. Its activities are bound to impact the society as the society’ s values would have an impact on the corporation. Therefore, they have mutual rights and obligations to discharge for the benefit of one another.

A corporation is a creation of law, as an association of persons forming part of the society in which it operates. Its activities are bound to impact the society as the society’s values would have an impact on the corporation. Therefore, they have mutual rights and obligations to discharge for the benefit of each other: national interest, legal compliances, honest and ethical conduct.

- National interest: A company (and its management) should be committed in all its actions to benefit the economic development of the countries in which it operates and should not engage in any activity that would militate against such an objective. A company should not undertake any project or activity detrimental to the nation’s interest or those that will have an adverse impact on the social and cultural life patterns of its citizens. A company should conduct its business in consonance with the economic development of the country and the objectives and priorities of the nation’s government and must strive to make a positive contribution to the realisation of its goals.

- Political non-alignment: A company should be committed to and support a functioning democratic constitution and system with a transparent and fair electoral system and should not support directly or indirectly any specific political party or candidate for political office. The company should not offer or give any of its funds or property as donations directly or indirectly to any specific political party candidate or campaign.

- Legal compliances: The management of a company should comply with all applicable government laws, rules and regulations. The employees and directors should acquire appropriate knowledge of the legal requirements relating to their duties sufficient to recognise potential dangers. Violations of applicable governmental laws, rules and regulations may subject them to individual criminal or civil liability as well as disciplinary action by the company apart from subjecting the company itself to civil or criminal liability or even the loss of business.

Legal compliance will also mean that corporations should abide by the tax laws of the nations in which they operate such as corporate tax, income tax, excise duties, sales tax, cesses and other levies imposed by respective governments. These should be paid on time and as per the required amount.

- Rule of law: Good governance requires fair, legal frameworks that are enforced impartially. It also requires full protection of rights, particularly those of minority shareholders. Impartial enforcement of laws require an independent judiciary and regulatory authorities.

- Honest and ethical conduct: Every officer of the company including its directors, executive and non executive directors, managing director, CEO, CFO and CCO should deal on behalf of the company with professionalism, honesty, commitment and sincerity as well as high moral and ethical standards. Such conduct must be fair and transparent and should be perceived as such by third parties as well.The officers are also expected to act in accordance with the highest standards of personal and professional integrity and ethical conduct at their place of work or while working on offsite locations where the company’ s business are located or at social events or at any other place where they represent the company. Honest conduct is a conduct that is free from fraud or deception. Ethical conduct is an ethical handling of actual or apparent conflicts between personal and professional relationship.

An ideal corporation has certain obligations to society such as corporate citizenship, ethical behaviour, environment-friendliness, observing correctly the rule of law and being politically non-aligned.

- Corporate citizenship: A corporation should be committed to be a good corporate citizen not only in compliance with all relevant laws and regulations, but also by actively assisting in the improvement of the quality of life of the people in the communities in which it operates with the objective of making them self-reliant and enjoy a better quality of life.

Such social commitment consists of initiating and supporting community initiatives in the field of public health and family welfare, water management, vocational training, education and literacy and encourages application of modern scientific and managerial techniques and expertise. The company should review its policy, in this respect, periodically in consonance with national and regional priorities. The company should strive to incorporate them as an integral part of its business plan and not treat them as optional and something to be dispensed with when inconvenient. It should encourage volunteering amongst its employees and help them to work in the communities. The company should develop social accounting systems and carry out social audit of its operations towards the community, employees and shareholders.

- Ethical behaviour: Corporations have a responsibility to set exemplary standards of ethical behaviour, both internally within the organisation, as well as in their external relationships. Unethical behaviour corrupts organisational culture and undermines stakeholder value. The board of directors have a great moral responsibility to ensure that the organisation does not derail from an upright path to make short-term gains.

- Social concerns: Corporations exist beyond time and space. So they have to set an example to their employees and shareholders. New paradigm is that the company should not only think about its shareholders but also think about its stakeholders and their benefit. A corporation should not give undue importance to shareholders at the cost of small investors. They should treat all of them equally and equitably. The company should have concerns towards the society. It can help the needy people and show its concern by not polluting the water, air and land. The waste disposal should not affect any human or other living creatures.

- Corporate social responsibility: Accountability to stakeholders is a continuing topic of divergent views in corporate governance debates. In line with the developing trends towards an integrated model of governance toward the creation of an ideal corporate, the emphasis should be laid on corporate social responsiveness and ethical business practices seeking what might well turn out to be not only the first small steps for better governance on this front but also the promise of a more transparent and internationally respected corporates of the future.

- Environment-friendliness: Corporations tend to be intervening in altering and transforming nature. For corporations engaged in commodity manufacturing, profit comes from converting raw materials into saleable products and vendible commodities. Metals from the ground are converted into consumer durables. Trees are converted into boards, houses, and furniture and paper products. Oil is converted into energy. In all such activities, a piece of nature is taken from where it belongs to and processed into a new form. So companies have a moral responsibility to save and protect the environment. All the pollution standards have to be followed meticulously and organisations should develop a culture having more concern towards environment.

- Healthy and safe working environment: A company should be able to provide a safe and healthy working environment and comply with the conduct of its business affairs with all regulations regarding the preservation of environment of the territory it operates in. It should be committed to prevent the wasteful use of natural resources and minimise the hazardous impact of the development, production, use and disposal of any of its products and services on the ecological environment.

An ideal corporate should also exhibit social concern and adequate social responsibility besides ensuring healthy and safe working environment. Corporations should uphold the fair name of the country.

- Competition: A company should play its role in the establishment and support a competitive, open market economy and co-operate to promote the progressive and judicious liberalisation of trade and investment by a country. It should not covertly or overtly engage in activities, which lead to or support the formation of monopolies, dominant market positions, cartels and similar unfair trade practices.

A company should market its products and services on its own merits and should not resort to unethical advertisements or include unfair and misleading pronouncements on competitors’ products and services. Any collection of competitive information shall be made only in the normal course of business and shall be obtained only through legally permitted sources and means.

- Trusteeship: Corporates have both a social purpose and an economic purpose. They represent a coalition of interests, namely, those of the shareholders, other providers of capital, business associates and employees. This belief, therefore, casts a responsibility of trusteeship on the company’s board of directors. They are to act as trustees to protect and enhance shareholder value, as well as to ensure that the company fulfills its obligations and responsibilities to its other stakeholders. Inherent in the concept of trusteeship is the responsibility to ensure equity, namely, that the rights of all shareholders, large or small, foreign or local, majority or minority, are equally protected.

- Accountability: Accountability is a key requirement of good governance. Not only governmental institutions but also the private sector and civil society organisations must be accountable to the public and to their institutional stakeholders. Who is accountable to whom varies depending on whether decisions or actions taken are internal or external to an organisation or institution. In general, an organisation or an institution is accountable to those who will be affected by its decisions or actions. Accountability cannot be enforced without transparency and the rule of law.

- Effectiveness and efficiency: Good governance means that processes and institutions produce results that meet the needs of society while making the best use of resources at their disposal. The concept of efficiency in the context of good governance also covers the sustainable use of natural resources and the protection of the environment.

- Timely responsiveness: Good governance requires that institutions and processes try to serve all stakeholders within a reasonable timeframe. They should also address the concerns of all stakeholders and the society at large.

- Corporations should uphold the fair name of the country: When companies export their products or services, they should ensure that these are qualitatively good and are delivered in time. They have to ensure that the nation’ s reputation is not sullied abroad during their deals, either as exporters or importers. They have to ensure maintenance of the quality of their products, which should be the brand ambassadors for the country.

Obligation to Investors

That the investors as shareholders and providers of capital are of paramount importance to a corporation is such an accepted fact that it need not be overstressed here. A company has the following obligations to investors:

A company ideally has the following obligations to investors: promoting transparency and informed shareholder participation. In the context of enhanced awareness of better governance practices, an ideal corporate should address these issues and ensure meaningful and transparent accounting and reporting, so that there is better harmony in the workplace.

- Towards shareholders: A company should be committed to enhance shareholder value and comply with all regulations and laws that govern shareholder’s rights. The board of directors of the company shall and fairly inform its shareholders about all relevant aspects of the company’s business and disclose such information in accordance with the respective regulations and agreements. Every employee shall strive for the implementation of and compliance with this in his professional environment. Failure to adhere to the code could attract the most severe consequences including termination of employment or directorship as the case may be.

- Measures promoting transparency and informed shareholder participation: A related issue of equal importance is the need to bring about greater levels of informed attendance and meaningful participation by shareholders in matters relating to their companies without, however, such freedom being abused to interfere with management decision. An ideal corporate should address this issue and relate it to more meaningful and transparent accounting and reporting.

- Transparency: Transparency means that decisions taken and their enforcement are done in a manner that follows rules and regulations. It also means that information is freely available and directly accessible to those who will be affected by such decisions and their enforcement. It also means that enough information is provided and that it is provided in easily understandable forms and media.

- Financial reporting and records: A company should prepare and maintain accounts of its business affairs fairly and accurately in accordance with the accounting and financial reporting standards, laws and regulations of the country in which the company conducts its business affairs.

Likewise, internal accounting and audit procedures shall fairly and accurately reflect all of the company’s business transactions and disposition of assets. All required information shall be accessible to the company’s auditors, non-executive and independent directors on the board and other authorised parties and government agencies. There shall be no wilful omissions of any transaction from the books and records, no advance income recognition and no hidden bank account and funds.

Such wilful material misrepresentation of and/or misinformation on the financial accounts and reports shall be regarded as a violation of the firm’s ethical conduct and also will invite appropriate civil or criminal action under the relevant laws of the land.

Obligation to Employees

For too long, corporations in free societies had been adopting a “Hire and Fire” policy in employment of men and women in their work places and hardly treated them humanely taking advantage of the fact that workers had a commodity, namely, labour that was highly perishable with little bargaining power. But in the context of enhanced awareness of better governance practices, managements should realise that they have their obligations towards their workers too.

- Fair employment practices: An ideal corporate should commit itself to fair employment practices, and should have a policy against all forms of illegal discrimination. By providing equal access and fair treatment to all employees on the basis of merit, the success of the company will be improved while enhancing the progress of individuals and communities. The applicable labour and employment laws should be followed scrupulously wherever it operates. That includes observing those laws that pertain to freedom of association, privacy, and recognition of the right to engage in collective bargaining, the prohibition of forced, compulsory and child labour, and also laws that pertain to the elimination of any improper employment discrimination.

By providing equal access and fair treatment to all employees on the basis of merit, the success of the company will be improved while enhancing the progress of individuals and communities.

- Equal opportunities employer: A company should provide equal opportunities to all its employees and all qualified applicants for employment without regard to their race, caste, religion, colour, ancestry, marital status, sex, age, nationality, disability and veteran status. Its employees should be treated with dignity and in accordance with a policy to maintain a conducive work environment free of sexual harassment, whether physical, verbal or psychological. Employee policies and practices should be administered in a manner that ensure that in all matters equal opportunity is provided to those eligible and the decisions are merit-based.

- Encouraging whistle blowing: It is generally felt that if whistle blower concerns have been addressed to some of the recent disasters could have been avoided, and that in order to prevent future misconduct, whistle blowers should be encouraged to come forward. So an ideal corporate is one that deals pro-actively with whistle blowers and to make sure employees have comfortable reporting channels and are confident that they will be protected from any form of retribution. Such an approach will enhance the company’s chances to become aware of, and to appropriately deal with, a concern before an illegal act has been committed rather than after the damage has been done. If reporting is delayed, the company’s reputation can be seriously harmed and it can face a serious risk of prosecution with all its disastrous consequences. An ideal Whistle Blower Policy would mean:

- Personnel who observe an unethical or improper practice (not necessarily a violation of law) shall be able to approach the CEO or the audit committee without necessarily informing their supervisors.

- The company shall take measures to ensure that this right of access is communicated to all employees through means of internal circulars, etc. The employment and other personnel policies of the company should contain provisions protecting “whistle blowers” from unfair termination and other prejudicial employment practices.

- The appointment, removal and terms of remuneration of the chief internal auditor shall be subject to review by the audit committee.

- Humane treatment: Now corporations are viewed like humans and similar kind of behaviour is expected from them like a man with good sense. Companies should treat their employees as their first customers and above all as human. They have to meet the basic needs of all employees in the organisation. There should be a friendly, healthy and competitive environment for the workers to prove their ability.

- Participation: Participation by both men and women is a key cornerstone of good governance. Participation could be either direct or through legitimate intermediate institutions or representatives. Participation needs to be informed and organised. This means freedom of association and expression on the one hand and an organised civil society on the other.

- Empowerment: Empowerment is an essential concomitant of any company’s principle of governance that management must have the freedom to drive the enterprise forward. Empowerment is a process of actualising the potential of its employees. Empowerment unleashes creativity and innovation throughout the organisation by truly vesting decision-making powers at the most appropriate levels in the organisational hierarchy.

- Equity and inclusiveness: A corporation is a miniature of a society whose well being depends on ensuring that all its employees feel that they have a stake in it and do not feel excluded from the mainstream. This requires all groups, particularly the most vulnerable, have opportunities to improve or maintain their well being.

- Participative and collaborative environment: There should not be any form of human exploitation in the company. There should be equal opportunities for all levels of management in any decision-making. The management should cultivate the culture where employees should feel they are secure and are being well taken care of. Collaborative environment would bring peace and harmony between the working community and the management, which in turn, brings higher productivity, higher profits and higher market share.

Obligation to Customers

A corporation’s existence cannot be justified without its being useful to its customers. Its success in the marketplace, its profitability and its being beneficial to its shareholders by paying dividends depends entirely as to how it builds and maintains fruitful relationships with its customers.

A company’s existence cannot be justified without its catering to the needs of its customers. The companies have an obligation to its employees, without whose assistance they cannot realise their objectives. They have to ensure quality of products and services; products at affordable prices; unwavering commitment to customer satisfaction. All these steps will earn for the company customers’ good will to stay long in the business.

- Quality of products and services: The company should be committed to supply goods and services of the highest quality standards, backed by efficient after sales service consistent with the requirements of the customers to ensure their total satisfaction. The quality standards of the company’s goods and services should meet not only the required national standards but also should endeavour to achieve international standards.