18

Corporate Governance in Developing and Transition Economies

CHAPTER OUTLINE

- Introduction

- Problems Faced by Developing and Transitional Economies

- Defining Corporate Governance

- Corporate Governance Models

- The Institutional Framework for Effective Corporate Governance

- Corporate Governance Challenges in Developing, Emerging and Transition Economies

- Current Corporate Governance Settings in Transition Economies

Introduction

The third quarter of the 20th Century witnessed innumerable corporate failures, triggered by frauds and scams worldwide. The reasons for such failures went far beyond just corporate misgovernance. Company managements with the connivance of board members and auditors conspired to defraud their stakeholders, both internal and external. The problems of misgovernance were deep-rooted and did not emanate only from the dichotomy between ownership and management. Lack of transparency and disclosures and inequitable treatment of shareholders, window dressing, fudging of accounts and funnelling of corporate funds into private channels were all becoming too common. These developments created a popular stir and the collective conscience of the world was rudely awakened to the murky going-ons among some of the corporates that adversely impacted their interests and well being. Steps were mooted to root out the misdemenours of the ill-behaved corporations. However, there was a problem. While it was easy to incorporate the required transformational changes in the corporate sphere of advanced countries where the systems, procedures and regulatory bodies to combat and arrest the declining standards were mostly in place, these were absent in the case of developing and transition economies where everything had to be built from the scratch.

The 20th century witnessed innumerable corporate failures, triggered by frauds and scams worldwide. Company managements with the connivance of board members and auditors conspired to defraud their stakeholders, both internal and external. Lack of transparency and disclosures and inequitable treatment of shareholders, window dressing, fudging of accounts and funneling of corporate funds into private channels were all becoming too common. Earlier, the common perspective of corporate governance was to respect the individual system of each country.

Earlier, the common perspective of corporate governance was to respect the individual system of each country. But in the context of globalisation with its attendant enhanced transnational movement of goods and services and for borderless capital markets, a set of global standards for corporate governance is being attempted in recent times. In such a scenario, it is imperative that developing and transition economies should try to put in place required systems and institutions with a view to benefiting from the world-wide application of the principles and percepts of best corporate governance practices. In this chapter, we will analyse the problems and issues confronted by transition economies, how best these can be surmounted and how well these societies can work out a framework and system to absorb the essence and core of corporate governance practices and radiate it to bring growth interspersed with equity in their efforts while developing their economies.

Corporate governance has become a topic of a worldwide political debate because of its apparent importance for the economic health of corporations and society in general. The Asian economic crisis, the continuing turmoil in Russia post-1991 reforms, and the experience of the Czech economy have combined to push the issue of corporate governance from the sidelines to the centrestage. The failure of Enron, WorldCom, and other mega corporations of the US and the moral turpitudes of auditing firms such as Arthur Andersen have added an urgency to remove all those factors that led to corporate misgovernance. There is now a need to have an interdisciplinary approach to study the problem of corporate governance since it spans multiple disciplines, including finance, strategic management, sociology and political science. The framework of corporate governance also depends on the legal and regulatory environment. In addition, the factors such as corporate responsibility and ethics are significant in the study of corporate governance.

Corporate governance is a means whereby society can be sure that large corporations are well-run institutions to which investors and lenders can confidently commit their funds. It is now increasingly clear that having a transparent and fair system to govern markets, equitable treatment of all stakeholders, and a chance for every entrepreneur with a good product to be successful, is as important to democracy as political institutions, and are crucial to sound market economies. Corporate governance creates safeguards against corruption and mismanagement, while promoting fundamental values of a market economy in a democratic society.

Problems Faced by Developing and Transition Economies

Many developing, emerging and transition economies lack or are just now in the process of developing the most basic market institutions. Hence, corporate governance in these societies involves a much wider range of issues. Economic growth in these countries has turned out to be lower than expected. Privatisation does not seem to have brought about the anticipated improvements in corporate efficiency. The state and “para-state” institutions such as privatisation funds remain the largest shareholders of companies. Internal owners dominate in many companies, while the external owners do not have enough voting power to control the companies and thereby to ensure for themselves appropriate returns. The capital markets are just developing and do not facilitate the inflow of new capital as intended. Further, market transactions are often based on the abuse of inside information.

In developed market economies, a system of corporate governance has been built gradually through centuries, and today it can be defined as a complex mosaic consisting of laws, regulations, politics, public institutions, professional associations and codes of ethics. However, in transition economies a lot of details of the mosaic are still missing. Trying to develop a system of good corporate governance in these countries is made difficult by problems such as complex corporate ownership structures, vague and confusing relationships between the state and financial sectors, weak legal and judicial systems, absent or under-developed institutions and scarce human resource capabilities.

Many developing, emerging and transition economies lack or are just now in the process of developing the most basic market institutions. Hence, corporate governance in these societies involves a much wider range of issues. Privatisation does not seem to have brought about the anticipated improvements in corporate efficiency. In developed market economies, a system of corporate governance has been built gradually through centuries, and today it can bedefined as a complex mosaic consisting of laws, regulations, politics, public institutions, professional associations and codes of ethics.

The need for corporate governance in developing, emerging and transition economies extends far beyond resolving problems stemming from the separation of ownership and control, which is the core and substance behind the need for corporate governance. Developing and emerging economies are constantly confronted with issues such as the lack of property rights, the abuse of minority shareholders, contract violations, asset stripping and self-dealing. To make matters worse, these acts often go unpunished. This is because many developing, emerging and transition economies lack the necessary political and economic institutions to enable democracy and markets function effectively. Without these institutions, corporate governance measures will have little impact. Hence, in the context of developing, emerging and transition economies, instituting corporate governance entails establishing democratic, market based institutions as well as sound guidelines to make companies run internally.

For instance, even in some leading developing countries like India which have the benefit of democratic institutions and equity culture for well over five decades, there have been a series of scams involving huge sums of public funds denting seriously investors’ confidence. The judiciary is so lethargic and bureaucratic that it takes more than a couple of decades to bring scamsters to book. Regulatory bodies are not alert, government appointees in Boards are lax, partisan politics and corruption in government and bureaucracy hardly play their roles in effectively stemming the damages caused by corporate misgovernance.

In other transition economies, the problem is still worse, as they lack democratic institutions and corporate culture apart from their having an overdose of bureaucratic management. In the process of establishing an equity culture, transparency in governance and building democratic institutions and regulatory bodies that function within them, much time is lost and more damage is done to proper democratic corporate governance. Some of the problems faced by these economies are given below:

- Lower economic growth

- Dominant public sector—the general perception is that corporate governance is meant for the private sector and the public sector does not fall within its purview

- Lack of effectiveness of privatisation

- Lack of awareness among shareholders

- Greater government influence, and less autonomy to enterprises

- Largest shareholders in most of the companies are the privatisation funds

- Internal owners dominate more than a company’s external owners. Given their discretionary powers, company managers use the company resources to their own advantage. Investors, therefore, cannot get their returns from cash flow of the company from the projects

- External owners do not have enough voting power

- Concentration of ownership in the hands of few individuals and family-owned corporations

- Lack of strong legal protection for investors in developing countries that leads to concentration of ownership which is used as a means to overcome the power of the management. This, in turn, leads to expropriation of minority interests

- Capital markets are underdeveloped and do not facilitate the inflow of new capital. The foreign investors are wary of these markets and hence hesitate to invest in these countries.

- Market transactions are often based on abuse of internal information, and are often manipulative

- Redrawing property rights and contract laws are slow in coming

- Lack of well-regulated banking sector

- Exit mechanisms, bankruptcy and foreclosure norms are absent

- Sound securities market does not exist

- Competitive markets have not developed

- Corruption and mismanagement abound

- Non-uniform guidelines—government formulated guidelines to ensure better governance are not uniformly applied to all companies. Structures of organisations, ownership and often inflexible and impractical rules stand in the way of applying these guidelines universally

Some of the problems facing these economies are lower economic growth, dominantpublic sector lack of awareness among shareholders, greater government infl uence, and less autonomy to enterprises.

The Why and Wherefore of Corporate Governance

In most of the emerging economies, the lack of corporate governance enables insiders, whether they are company managers, company directors or public officials, ransack companies and deny public coffers their dues. They tend to enrich themselves at the expense of shareholders, creditors and other stakeholders such as employees, suppliers, the general public and public authorities.

Globalisation and financial market liberalisation have exposed companies to fierce competition and to considerable capital fluctuations. To expand and be internationally competitive, companies need a large quantum of capital that exceeds traditional funding sources. Failure to attract adequate levels of capital threatens the very existence of individual firms and can have dire consequences for entire economies. Before committing such large funds, investors especially institutional investors require evidence that companies are run according to sound business practices that minimise the possibilities for corruption and mismanagement.

For countries in transition, such as those of Russia and other Eastern European societies, that are forced to adopt capitalistic norms of governance in preference to the erstwhile socialistic system, the problem of good corporate governance development becomes more complicated due to the under-developed institutional infrastructure. The importance of sound corporate governance for transition economies can be explained through its main influences: creation of the key institution which drives the successful economic transformation to a market-based economy, effective allocation of capital and development of financial markets, attracting foreign investment and making a contribution to the process of national development. Corporate governance requires coherent and strict legal regulations which imply an urgent mission for the makers of economic policies of countries in transition. Furthermore, it is important to provide for systems to recruit, train and reward professional managers who can be held to high standards of competency, ethics, and responsibility.

Corporate governance is directly related to financing and investments. For countries in transition, the scarcity of domestic savings demands that capital should be directed towards the most profitable companies, which is possible only if principles of corporate governance are given publicity, transparency and monitoring; in addition, due to the imperfection of market mechanisms (under-developed stock and bond markets and an ineffective banking system), corporate governance presents an additional mechanism for discipline and effective management control in corporations. International capital flows enable companies to tap sources of financing from a great number of investors. If countries want to take full advantage of global capital markets and if they want to attract long-term capital, they must follow clear standards of corporate governance at the international level. The degree to which corporations use basic principles for good corporate governance is a relevant factor for investment decisions as well. It is especially important when we talk about direct investments, which are of the greatest benefit to countries in transition because they bring not only capital, but managerial skills, technology and know-how as well. Corporate governance is just as important for public sector firms as for private sector companies. Instituting corporate governance within public sector firms has recently begun to receive increased attention. This is particularly the case when countries are attempting to curb widespread corruption within the public sector, or when they are preparing public enterprises for privatisation.

Defining Corporate Governance

In its narrowest sense, corporate governance can be viewed as a set of arrangements internal to the corporation that define the relationship between the owners and managers of the corporation. Corporate governance “&is the relationship among various participants in determining the direction and performance of corporations. The primary participants are (1) the shareholders, (2) the management and (3) the board of directors.”

In its narrowest sense, corporate governance can be viewed as a set of arrangements internal to the corporation that define the relationship between the owners and managers of the corporation. Corporate governance “&is the relationship among various participants in determining the direction and performance of corporations. The primary participants are the shareholders, the management and the board of directors.”

The World Bank defines corporate governance from two different perspectives. From the standpoint of a corporation, the emphasis is put on the relations between the owners, management board and other stakeholders (employees, customers, suppliers, investors and communities). Another perspective in defining corporate governance is called “path dependence” where initial historical conditions matter in determining the corporate governance structures that are prevalent today. So, a nation’s system of corporate governance can be seen as an institutional matrix that structures the relations among owners, Boards, and top managers, and determines the goals pursued by the corporation.1

The OECD’S (1999) original definition is: “Corporate governance specifies the distribution of rights and responsibilities among different participants in the corporation, such as the Board, managers, shareholders and other stakeholders, and spells out the rules and procedures for making decisions on corporate affairs. By doing this, it also provides the structure through which the company objectives are set, and the means of attaining those objectives and monitoring performance.”2

Corporate Governance Models

The countries with developed economies apply two different systems of corporate governance—the group-based system and the market-based one or as they are often referred to as the insider and outsider systems.

Insider System

In concentrated ownership structures, ownership and/or control is concentrated in the hands of a small number of individuals, families, managers, directors, holding companies, banks and/or other non-financial corporations. Most countries, especially those governed by civil law, have concentrated ownership structures. Insiders exercise control over companies in several ways: own the majority of the company shares and voting rights; own some shares, but enjoy the majority of the voting rights.

Companies that are controlled by insiders enjoy certain advantages. Insiders have the power and the incentives to monitor management closely thereby minimising the potential for mismanagement and fraud. Moreover, because of their significant ownership and control rights, insiders tend to keep their investment in a firm for longer periods. As a result, insiders tend to support decisions that will enhance a firm’s long-term performance as opposed to decisions designed to maximise short-term gains.

However, insider systems predispose a company to certain corporate governance failures. One is that dominant owners and/or vote holders can bully or collude with management to expropriate the firm’s assets at the expense of minority shareholders. This is a significant risk when minority shareholders do not enjoy legal rights. Similarly, when managers control a large number of shares or votes they may use their power to influence board decisions that may directly benefit them at the company’s expense.

In short, insiders who wield their power irresponsibly waste resources and drain company productivity levels; they also foster investor reluctance and illiquid capital markets. Shallow capital markets, in turn, deprive companies of capital and prevent investors from diversifying their risks.

Developed countries apply two different systems of corporate governance—the insider and outsider systems. The insider system: ownership and/or control is concentrated in the hands of a small number of individuals, families, managers, directors, holding companies, banks and/or other non-financial corporations. Most countries, especially those governed by civil law, have concentrated ownership structures. In the outsider system owners rely on independent board members to monitor managerial behaviour and keep it in check. As a result, outsider systems are considered more accountable and less corrupt and they tend to foster liquid capital markets. Despite these advantages, dispersed ownership structures have certain weaknesses.

Outsider System

Dispersed ownership is the other type of ownership structure. In this scenario, there are a large number of owners each holding a small number of company shares. Small shareholders have little incentive to closely monitor a company’s activities and try not to be involved in management decisions or policies. Hence, they are called outsiders, and dispersed ownership structures are referred to as outsider systems.

Common Law countries such as the UK and the US tend to have dispersed ownership structures. The outsider system or Anglo-American, market-based model is characterised by the ideology of corporate individualism and private ownership, a well-developed and liquid capital market, with a large number of shareholders and a small concentration of investors. The corporate control is realised through the market and outside investors.

In contrast to insider systems, owners in outsider systems rely on independent board members to monitor managerial behaviour and keep it in check. As a result, outsider systems are considered more accountable and less corrupt and they tend to foster liquid capital markets. Despite these advantages, dispersed ownership structures also have certain weaknesses. Dispersed owners tend to be interested in short-term profit maximisation and they approve policies and strategies that will yield short-term gains, but may not necessarily promote long-term company performance. At times, this can lead to conflicts between directors and owners, and to frequent ownership changes because shareholders may divest in the hopes of reaping higher profits elsewhere, both of which weaken company stability. Small-scale investors have less financial incentive to vigilantly monitor boardroom decisions and to hold directors accountable. As a result, directors supporting unsound decisions instead of being removed remain on the board, which is against the company’s interest.

In the outsider model, the discussions about corporate governance are focussed on the responsibility of corporate managers, the lack of control and direct supervision from the owners’ part, and the imperfection of existing control and compensation mechanisms.

It is evident that both insider and outsider systems have inherent risks. Failure to institute the appropriate mechanisms to reduce these risks jeopardises the well-being of entire economies. Corporate governance systems are designed to minimise these risks and to promote political and economic development. An effective corporate governance system relies on a combination of internal and external controls. Internal controls are arrangements within a corporation that aim to minimise risk by defining the relationships between managers, shareholders, boards of directors, and stakeholders. In order to have meaningful effect of these measures, they must be buttressed by a variety of extra-firm institutions or external controls tailored to a country’s environment.

Developing a Corporate Governance Framework

There are the following three different ways in which owners maintain control over the work of management:

- The owners directly influence the corporate strategy and selection of the top management team

- The owners delegate their rights to the board, but ensure that compensation and other incentives are aligned with share price maximisation.

- The owners rely on the market mechanisms of corporate control, such as takeover, when due to a decreasing share price new owners take over a company and change management in order to rehabilitate the company and increase its market value.

In other words, the corporate governance mechanisms can be both internal and external.3 There are two basic dilemmas connected with the corporate governance problem in transition economies. First, is it possible to have the identical framework that has evolved over centuries in developed market economies for the emerging markets, or is it better to adapt the system of corporate governance to the specific circumstances of a transition economy?

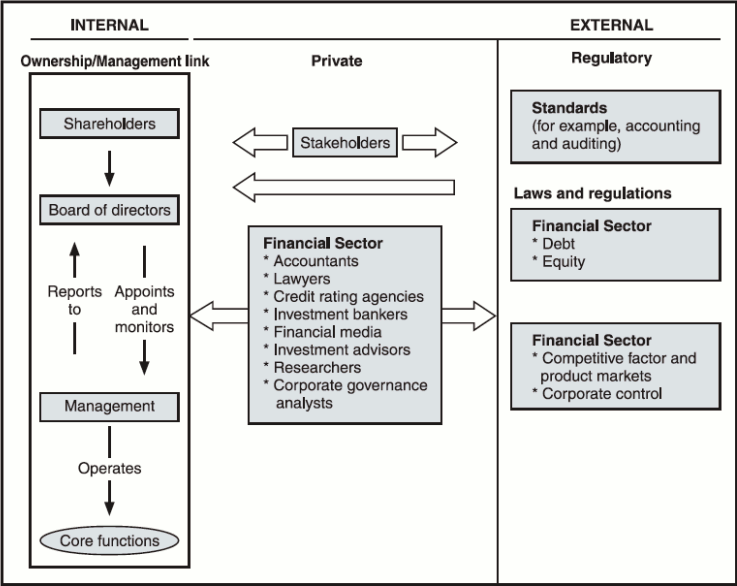

The framework for the implementation of corporate governance in developed economies is explained by the World Bank, as shown in Figure 18.1.

There are three different ways that owners maintain control over the work of management. The owners directly influence the corporate strategy and selection of the top management team, the owners delegate their rights to the board, but ensure that compensation and other incentives are aligned with share price maximization and the owners rely on the market mechanisms of corporate control, such as takeover, when due to a decreasing share price new owners take over a company and change management in order to rehabilitate the company and increase its market value.

It can be observed from the illustration of the framework that there are internal and external forces that interface and interact with one another and have an impact on the behaviours and activities of corporations. While the internal forces define the relationships between and among the key players of the corporation, the external forces help in effecting the discipline and conduct of beahviours.

In developed market economies especially of the West, as the illustration depicts, these forces are institutions and policies that ensure greater transparency by monitoring and effecting discipline among corporations. Examples of external forces include the legal framework for ensuring competition among corporates, the legal machinery to protect rights and privileges of shareholders, the system of accounting and auditing, a well-regulated financial system, the bankruptcy system and the market for corporate control. One could easily envision the situation wherein the internal and external forces combined together create a range of corporate governance systems, reflecting market structures, legal framework, rules and regulations, traditions, precedents and perceptions, cultural and social values.4

Figure 18.1 Modern corporations are disciplined by internal and external factors

Source: World Bank, Corporate Governance: Framework for Implementation, Overview, 1999, www.worldbank.org., p.5.

The second dilemma involves the question of the appropriateness of the mechanism used for corporate governance. The existing corporate governance literature is almost exclusively concerned with external mechanisms—accounting transparency to improve the accuracy of stock market valuations, regulatory pursuit of fraud, the role of the shareholders’ general meeting, “disciplinary” takeovers, legal requirements for the appointment of “external” directors. In these external mechanisms, the crucial role belongs to the well-developed stock market or to the monitoring role of the banks. Unfortunately, in transition economies these mechanisms of market discipline hardly work because of the lack of such institutions as stock markets and an efficient banking sector.

The Institutional Framework for Effective Corporate Governance

As we have seen earlier, developing countries and transition economies lack the required framework to put in place best corporate governance practices. The following are the desiderata for such a framework:

1. Property rights: It is essential that property rights, laws and regulations establish simple and straightforward standards to specify clearly who owns what and how these rights can be combined or exchanged (for example, through commercial transactions), and standards for recording required information (such as the legal owners of property, has the property been used as loan collateral, etc.) in a timely and cost-efficient manner into an integrated, publicly accessible data base. Investors will be extremely reluctant to provide capital to firms without legally stipulated and enforced property rights.

In this context, there are a few key types of legislation. The first is legislation that gives corporations juridical personality by recognising their existence as legal “persons” independent of their owners, establishes corporate chartering requirements, and limits corporate owners’ liability to the value of their equity in the corporation. The second is legislation that permits the establishment of joint stock companies.

Developing countries and transition economies lack the required framework to put in place best corporate governance practices. They need to develop property rights contract laws and a well-regulated banking sector.

2. Contract law: Very few business transactions will occur without legislation and regulations that legally guarantee and enforce the sanctity of contracts. It is essential that such institutions protect suppliers, creditors, employers, employees and so forth. Without such legislations that protect the sanctity of the system of contracts, industries, trade, business and commerce can not have easy and uninterrupted supply of factors of production, raw materials, components, etc.

3. A well-regulated banking sector: A healthy banking system is an absolute prerequisite for a well-functioning stock market and corporate sector. The banking sector provides the necessary capital and liquidity for corporate transactions and growth. Good governance within the banking system is especially important in developing countries where banks provide most of the finance. Moreover, financial market liberalisation has exposed banks to more fluctuations and to new credit risks. As evidenced by the Asian and Russian crises, poorly governed banking systems and massive capital flight can seriously damage national economies.

The banking framework is based on three pillars: minimum capital requirements, supervisory review of an institution’s internal assessment process and capital adequacy and effective use of disclosure to strengthen market discipline as a complement to supervisory efforts. The first, minimum capital requirements, provides banks and supervisors with a range of tools to accurately assess different types of risks so that a bank has an adequate amount of capital to cover these risks. Determining the accuracy of capital adequacy requirements, is useful only if such requirements are upheld. To this end, each bank has a set of policies and procedures to ensure adequate capital requirements, in particular, and sound bank management, in general. Such measures include undertaking credit risks, monitoring and disciplining large borrowers effectively, and adhering to stringent auditing procedures. In the end, it is the results of these internal processes that count and these depend on two factors. The first is effective corporate governance of borrowers, usually firms. Banks need accurate information about a firm’s condition in order to assess risks appropriately. This demands that a company has well-documented and thoroughly audited books that are made available to banks.

The second, the supervisory review process is designed to have effective monitoring mechanisms that ensure compliance. Based on a set of standards, supervisors review a bank’s internal processes in order to determine the extent to which these measures assess the bank’s capital adequacy needs relative to a thorough evaluation of risks. The third, the new framework, bolsters the first two by strengthening disclosure requirements and thereby enhancing market discipline. The only way that market participants can evaluate the soundness of their dealings with banks is weather they can understand and have access to banks’ risk profiles and capital adequacy positions in a timely manner. Regular disclosure of this information will discipline banks because market participants will flock to banks that have sound practices and are financially viable. Market participants will avoid banks that take excessive risks without adequate capital provisions, and possibly those that do not undertake enough risk in order to remain competitive. Disclosing banks’ risk assessments can also improve corporate governance. Banks’ company risk rankings provide important information about a corporation’s financial viability. Shareholders can use this information to press managements for changes or to discipline managements by shifting their capital elsewhere.

Similarly, disclosing information about banks’ ownership structures and relationships with other firms or the public sector fosters good governance of banks and corporations, and helps prevent moral hazard and financial meltdowns. Many developing countries experienced financial crises that stemmed from undisclosed transactions that were not conducted at arm’s length. Examples include the frequent and substantial direct or connected lending by banks to firms in the bank’s business group that were not creditworthy. When this happens on a large scale, the impact can be as great as any other economic shock. In short, links between the government, banks and corporations should be at least disclosed so that shareholders and board members can respond accordingly, and, at best, severed. Similarly, there is increasing discussion about whether or not developing countries should require that commercial and investment banking activities be separated.

4. Exit mechanisms: bankruptcy and foreclosure: Because not all corporate endeavours succeed, legislation that establishes orderly and equitable clearing and exit mechanisms is essential so that investments can be liquidated and reallocated into productive undertakings before they are squandered completely. What is herein necessary are laws and regulations that require financial and non-financial entities to adhere to rigorous disclosure standards concerning their debts and liabilities; and laws and procedures that allow for swift, efficient bankruptcy and foreclosure proceedings that are equitable to creditors and other stakeholders alike. The lack of transparency regarding company and bank debts was a major factor behind the Asian and Russian financial crises. Moreover, the lack of adequate and/or enforced bankruptcy and foreclosure procedures facilitated widespread asset-stripping by insiders.

5. Sound securities markets: Efficient securities markets discipline insiders by sending price signals rapidly and allowing investors to liquidate their investment quickly and inexpensively. This affects the value of a company’s shares and a company’s access to capital. A well-functioning securities market requires laws governing how corporate equity and debt securities are issued and traded, and stipulating the responsibilities and liabilities of securities issuers and market intermediaries (brokers, accounting firms and investment advisers) that are based on transparency and fairness. In particular, laws and regulations governing pension funds and allowing for open-ended mutual funds are extremely important; Stock-Exchange listing requirements should be based on transparency and stringent disclosure standards—independent share registries would be useful in this regard, laws protecting minority shareholders’ rights and a government body such as a Securities Commission that has independent and qualified regulators empowered to regulate corporate securities transactions and to enforce securities laws.

6. Competitive markets: The existence of competitive markets is an important external control on companies forcing them to be efficient and productive lest they lose market share or go under. The lack of competitive markets discourages entrepreneurship, fosters management entrenchment and corruption and lowers productivity. For this reason, it is crucial that laws and regulations establish a commercial environment that is fair, yet competitive. To this end, governments can do the following:

- Remove barriers to entry

- Enact competition and anti-trust laws

- Eliminate protectionist barriers including the protection of monopolies

- Eliminate preferential treatment schemes such as subsidies, quotas, tax exemptions, etc.

- Establish fair trade priorities

- Remove restrictions on foreign direct investment and foreign exchange

- Reduce the cost of setting-up and running a formal business

7. Transparent and fair privatisation procedures: Having transparent, straightforward and fair rules and procedures stipulating how and when enterprises can be privatised is, therefore, essential. Ill-designed privatisation schemes can devastate an economy and negatively influence the business environment. This has been proved time and again in many transition economies and emerging markets.

8. Transparent and fair taxation regimes: Taxation systems should be reformed so that they are fair, simple and straightforward. In this regard, multi-step, complex procedures on fiscal reporting that allow officials to exercise considerable discretion and therefore engage in corruption should be eliminated. Tax laws and regulations should also require adequate and timely disclosure of financial information, and should be enforced, consistently, timely and effectively.

Emerging economies have to put in place transparent and fair privatisation procedures, Transparent and fair taxation regimes, an independent, well-functioning judicial system, strengthened administrative and enforcement capacity of government agencies and establish routine mechanisms of participation.

9. An independent, well-functioning judicial system: One of the most important institutions of a democratic, market-based economy is an independent, well-functioning judicial system that enforces laws consistently, efficiently and fairly, thereby maintaining the rule of law. The judiciary should be alert, efficient and proactive and should be able to dispense justice fairly and speedily.

10. Anti-corruption strategies: One of the major factors that promotes, corporate misgovernance is corruption which is the by-product of controls, bureaucratisation and excessive governance. The state should implement effective anti-corruption measures by specifying and streamlining legal and regulatory codes and clarifying laws on conflict of interest. This will lead to better corporate governance.

11. Reform government agencies: Government agencies that are excessively bureaucratic and inefficient need to be reformed. This can be accomplished by streamlining and simplifying agencies’ internal operating procedures and by regularly evaluating agencies’ performance according to clear, well-defined standards. Measures to improve poorly performing agencies need to be implemented promptly and comprehensively. For example, when exported and imported goods are held up for lengthy periods of time in government-owned ports by customs authorities, entrepreneurs’ costs increase and the competitiveness of these goods decreases; moreover, the temptation to ask for and pay bribes to speed up the process increases.

12. Strengthen administrative and enforcement capacity of government agencies: Governments in these economies should strengthen and maintain their agencies’ administrative and enforcement capacity by cultivating a staff of well-qualified civil servants, hiring and promoting staff based on verifiable professional standards (through standardised tests), offering civil servants vocational training based on the latest technology, paying adequate salaries to attract well-qualified professionals and to deter bribe taking, and offering tenure based on performance. The capacity of government agencies can also be strengthened by providing sufficient financial and technical resources to administer laws expeditiously.

13. Establish routine mechanisms of participation: Establishing the necessary institutional framework for corporate governance to take root requires reforming many existing laws and regulations and creating new ones. In order to ensure that the new framework creates a level playing field, citizens need to have ample opportunity to participate in grafting it. To ensure this, establishing routine mechanisms to participate in the policymaking process on a daily basis are required.

14. An investigative and well-informed media: A well informed and committed media plays a very significant role in ensuring corporate governance. The role of the Fourth Estate (Media) in ensuring corporate democracy cannot be overstressed, and can be considered as important as its role in ensuring that political democracy functions as well as it is intended to be. Many a scam in the corporate world would not have come to limelight but for the bold and upright investigation of journalists. At the same time, journalists and the media they represent also have the responsibility to bring to light and commend the good deeds the corporates do just as they condemn their misdeeds.

15. Strengthening reputational agents: Reputational agents are individuals and/or groups that reduce the information gap between insiders and outsiders by seeking and providing information to outsiders about the performance of insiders and enterprises and by setting high professional standards and then applying peer pressure and, at times, sanctions to uphold them. Reputational agents can also “refer to private sector agents, self-regulating bodies, the media and civic society that reduce information assymmetry, improve the monitoring of firms, and shed light on opportunistic behaviour”. For this reason, it is important to provide the necessary training and environment in which such agents can thrive. Examples of reputational agents include the following:

- Self-regulation bodies such as accounting and auditing professionals

- The media

- Investment bankers and corporate governance analysts

- Lawyers

- Academicians, economists and corporate analysts

- Credit rating agencies

- Consumer activists

- Environmentalists

- Activist investors and shareholders such as institutional investors and venture capitalists

- Non-government Organisations (NGOs)

Each of these individuals or groups has a particular type of expertise, and the resources and responsibilities to undertake intensive monitoring to bridge the information gaps between insiders and outsiders.

Sound Stakeholder Relationships are Good for Business

A common misconception is that achieving profits and looking after stakeholders’ interests are diametrically opposite goals. Operating fairly, responsibly, transparently and accountably towards both shareholders and other stakeholders does more than improving a company’s reputation and attract investment; it gives the corporation a competitive advantage. Firms rely on stakeholders to provide a series of essential inputs such as labour, components, spare parts and other supplies on a predictable basis. Interruptions in the supply of these goods and other services will harm the company’s ability to operate, sell its products and thus survive—let alone make profits. Hence, cultivating and maintaining productive relationships with stakeholders is in a company’s best, long-term interest.

A company’s treatment of other stakeholders such as suppliers is just as important to the company’s long-term performance. A firm that breaks a contract with a supplier or pays unfair prices not only hurts the supplier, but damages its own reputation as a reliable and honest business partner. Other suppliers will be reluctant to conduct business with this company thereby jeopardising the supply of crucial inputs. Moreover, firms that switch suppliers solely based on cost considerations may wind up with an inferior final product that could jettison their overall sales levels and reputation.

In short, firms that treat stakeholders fairly and include them in long-term strategy-planning sessions, minimise the risk that these stakeholders will use their power to extort resources from the company by charging exorbitant fees for specialised inputs—whether it be parts of technical assistance—or by failing to uphold contracts. Stakeholders will quickly realise that their fate hinges partly on the firm’s performance and vice versa.

Healthy relationships between firms and stakeholders can also boost a company’s market share. Employees (whether company staff, suppliers or vendors) that are well-paid and enjoy stable jobs or contracts will have the money and the incentive to buy the firm’s products thereby increasing the company’s value and profits.

There are other ways through which companies can increase profits while offering stakeholders, benefits. A firm that provides infrastructure, education and training programme gives the community useful resources. Local citizens and policymakers will, in turn, have an incentive to return the favour by providing the company with a hospitable business climate in terms of laws and regulations. This can greatly reduce a firm’s operating costs thereby enhancing competitiveness and increasing profits.

Corporate Governance Challenges in Developing, Emerging and Transition Economies

Establishing any one of institutions enumerated above is a necessary and challenging undertaking without which democratic markets and corporate governance cannot take root. Success requires that the private and public sectors work together to establish the necessary legal and regulatory framework and a climate of trust through ethical behaviour.

While the set of institutions described above is designed to be comprehensive, each region is in a different stage of establishing a democratic, market-based framework and a corporate governance system. Hence, each nation has its own particular set of challenges. Some of the general challenges confronting developing, emerging and transition economies include the following:

- Establishing a rule-based (as opposed to a relationship-based) system of governance

- Combating vested interests

- Dismantling pyramid ownership structures that allow insiders to control and, at times, siphon off, assets from publicly owned firms based on very little direct equity ownership and thus few consequences

- Severing links such as cross shareholdings between banks and corporations

- Establishing property right systems that clearly and easily identify true owners even if the state is the owner (When the state is the owner, it is important to indicate which state branch or department enjoys ownership and the accompanying rights and responsibilities.)

- De-politicising decision-making and establishing firewalls between the government and management in corporatised companies where the state is a dominant or majority shareholder

- Protecting and enforcing minority shareholders’ rights

- Preventing asset stripping after mass privatisation;

- Finding active owners and skilled managers amid diffuse ownership structures

- Educating and enlightening investors of their rights and duties

- Encouraging good corporate governance practices and creating benchmarks through co-operation with trade associations

- Establishing regulatory bodies that help reduce fissures through arbitrations and conciliations between competing and conflicting parties;

- Promoting good governance within family-owned and concentrated ownership structures

- Cultivating technical and professional know-how.

Corporate Governance Is Not Only a Private Sector Affair

In many developing, emerging, and transition economies public sector companies contribute more to the nation’s gross national product, employment, income, and capital use than private sector firms. Moreover, public sector companies often shape public policies. As a result, instituting sound corporate governance practices within public sector companies is essential to economic development, growth and reform. To begin with, public companies need to be corporatised before they can be privatised. The corporatisation process can, at times, be lengthy. Even after corporatisation, it takes time before the new company benefits from active owners and skilled managers. In the meantime, good management of the company will ensure that the company’s resources are managed efficiently and fairly thereby increasing the company’s productivity and value. There are other scenarios calling for governance practices within the public sector. Public companies, for example, may gain control of previously privately owned firms through joint ventures. In addition, some public economic entities may never be privatised because they are considered vital to national security or politically sensitive. Obviously, these companies would benefit from sound corporate governance practices. This can be enhanced through granting of financial and managerial autonomy which will reduce political interference, nepotism, corruption and other such evils.

In many emerging, economies public sector companies contribute more to the nation’s gross national product, employment, income, and capital use than private sector firms apart from shaping public policies. As a result, instituting sound corporate governance practices within public sector companies is essential to economic development, growth and reform.

Successful Strategies—One Size Does Not Fit All

Many international organisations are funding corporate governance initiatives that aim to put in place developed country models of corporate governance. More often than not, this fails to instill or improve corporate governance because these models are not designed for local realities and challenges. As a result, indigenous groups are then faced with the task of adapting the international model to local conditions. In India, for instance, attempts by international organisations such as the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and the WTO to promote transparency, accountability and such healthy practices have not been taken kindly by a vast section of political spectrum. The critics complain that these western-based organisations try to transplant systems and procedures that are workable in the West, but are unsuitable in the developing economies that have different cultures, work ethics, employer-employee relations and so on.

Current Corporate Governance Settings in Transition Economies

In emerging economies, the term “corporate governance” is new, yet it has caught on rapidly. A set of formal legal frameworks, often modeled after the Anglo-American system, frequently exists. Nearly all firms have shareholders, boards, and “professional” managers, which are the components of modem corporate governance. However, the similarities in governance between emerging and developed economies are often more in form than in substance.

The countries in transition are facing the problem of corporate governance in a specific way. Their corporate sector consists of “instant corporations” formed as a result of mass privatisation, without the simultaneous development of legal and institutional structures necessary to operate in a competitive market economy. Under the circumstances of diffuse ownership, it enables insiders to strip assets and leave little value for minority shareholders.5

The business environment is without the set of elements needed for making competitive relationships, which provides an advantage to old, large, dominant companies and discourages entrepreneurship and the appearance of new companies. Unstable macroeconomic conditions create a situation of great uncertainty and shorten the time horizon in business. Under unpredictable economic circumstances, managers see their positions as temporary and uncertain which leads to maximising their own profit instead of maximising the company’s profit.

The role of the state in the transition economies is ambiguous. On the one hand, the role of the state in post-socialism should be limited. On the other hand, strong state power is needed to carry through the political programmmes required by economic transformation. Weak governments have proved to be incapable of economic transformation. In reality, the state still has a great role in both the industrial and financial sectors. State authorities and company managers are tightly related, so that the line between the “controllers” and the “controlled” is unclear. In practice, informal constraints, such as relational ties and family and government contacts play a greater role, leading to different outcomes.

The state gives subsidies to companies directly or indirectly while on the other hand, companies enable state representatives to have a certain amount of control over the process of making decisions and cash flow. Behaving in such a way, managers are constantly searching for new subsidies instead of looking for existing or potential strategic partners.

The countries in transition face problem of corporate governance in a paradoxical situation. Their corporate sector consists of “instant corporations” formed as the result of mass privatisation, without the simultaneous development of legal and institutional structures necessary to operate in a competitive market economy. The business environment is without the set of elements needed for making competitive relationships, which provides an advantage to old, large, dominant companies and discourages entrepreneurship and the appearance of new companies. The role of the state in the transition economies is ambiguous. On the one hand, the role of the state in post-socialism should be limited. On the other hand, strong state power is needed to carry through the political programmmes required by economic transformation.

The creation of networks of linked enterprises, rather than of autonomous independent firms is a relationship characteristic of transition economies. Transactions between privatised enterprises become linked to each other, to banks and to the state through complex structures of cross-shareholding and corporate interlocks. Relationships between enterprises and banks are especially crucial in view of the shortage of capital and credit, and continue to be influenced by personal and institutional connections. Where credit is not available from banks, barter relationships amongst organisations known to and trusted by each other provide an alternative means of financing.

In transition economies, the most important firms, such as public sector companies that contribute more to the nation’s gross national product, employment, income and capital use than private sector firms, are controlled by the state as it was in India, prior to 1991. Moreover, public sector companies often shape public policies. From a governance perspective, state-owned firms are controlled by bureaucrats with control rights but with no formal ownership. Although all citizens of a country own the firms, in practice control rights rest with powerful ministries. As a result, citizens subsidise state firms and end up as “minority shareholders” with practically no voice.

The missing element in the context of corporate governance development in transition economies is the lack of institutions associated with successful market economies. In the market economies there is a standard set of institutions that have been successful as the tools used to control corporations. Institutions are the “rule of the game” in a society. They are the rules that society established to reduce the uncertainty of human interactions. The institutional framework has three components: formal rules, informal rules and enforcement mechanisms. While both the formal legal environment and the informal institutional constraints affect corporate governance, institutional theory states that when formal institutions are weak, informal constraints play a larger role in shaping firm behaviour.

Indian cos Committed to Best Global Practices6

According to Stephen Wagner, Indian companies are increasingly putting in place best global practices. At the same time, they have to resort to regular evaluation at all levels with a view to sustaining good corporate governance. “Corporate governance has evolved enormously in India and many big companies in the country are committed to embrace global best practices for their business,” observed Stephen Wagner, Chairman Emeritus of global consultancy Deloitte’s Global Centre for Corporate Governance. “Good governance at companies usually translates into good financial numbers while just having good names on the (firms’) board need not ensure the same.”

In India, the issue of corporate governance came into limelight after the Rs 14,000 crore Satyam accounting fraud by its founder-chairman Ramalinga Raju was brought to the notice of the public.

The question is whether it is possible to reproduce all at once from the institutions of developed market economies in transition economies. The standard institutional portfolio has evolved gradually in different circumstances. Merely transplanting these institutions is not possible because there are new conditions and many cultural differences. On the other hand, to develop entirely new institutions would be an unpredictable adventure. The transition economies cannot afford the luxury of searching for third system between socialism and capitalism. Instead, they have to find a way to accept the existing institutional portfolio and to make it work in the specific cultural, historical and economic environment. Each region is in a different stage of establishing a democratic, market-based economy and a corporate governance system. Hence, each nation has its own particular set of challenges and it has to solve its problems in a way it successfully addresses these and establish the most suitable system of government practices ideal to its genius and people.

- Transition economies

- Anti-corruption strategies

- Competitive markets

- Contract law

- Effective corporate governance

- Emerging economies

- Enforcement capacity

- Exit mechanisms

- Bankruptcy and foreclosure

- Fair taxation regimes

- Governance challenges

- Governance framework

- Governance models

- Governance settings

- Government agencies

- Insider system

- Outsider system

- Participation

- Property rights

- Reputational agents

- Routine mechanisms

- Sound securities markets

- Stakeholder relationships

- Successful strategies

- The institutional framework

- Transparent and fair privatisation procedures

- Well-informed media

- Well-functioning judicial system

- Well-regulated banking sector

- Why and wherefore

- What are the important characteristics of developing countries? Explain their features in the context of countries like India.

- Define corporate governance. Justify the why and therefore of corporate governance in the context of low income countries.

- Discuss the different models of corporate governance. What are the different ways in which an appropriate corporate governance framework can be developed for countries like ours?

- How can a state/society create an institutional framework to ensure corporate governance in the administration of companies involved in business?

- What are the challenges and opportunities involved in ensuring corporate governance in transition economies?

- According to some cynics, corporate governance is a myth. What is your take on this?

- Tricker, B. (1999), Corporate Governance: The Ideological Imperative, in: H.Thomas, and D.O’Neal, Strategic Integration, SMS, Chichester: Wiley.

- CIPE, Instituting Corporate Governance in Developing, Emerging and Transition Economies, A Handbook, March 2002, http://www.cipe.org

- Corporate Governance in Emerging Markets, Vol. 1, ICFAI University.

- OECD (1999) Principles of Corporate Governance, www.oecd.org

- OECD (2001) Corporate Governance and National Development, Technical Papers No. 180, www.oecd.org

- Monks, R.A.G. and N. Minnow (2001) “Corporate Governance”, 2nd Ed, Balckwell Publishing.

- World Bank, Corporate Governance: Framework for Implementation, Overview, 1999, www.worldbank.org

Case Study

Problems and Issues of Corporate Governance in Emerging Economies: Russian Example

The Russian Economy in Transition

The early 1990s witnessed a dramatic transformation of the Russian economy. It started with the dismantling of the command (centrally planned) economy, which was a hallmark of the erstwhile Soviet Union. This was gradually replaced by a market-driven economy operating on the basis of market forces and private property. With the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, the Russian Federation became an independent country. Russia that was the largest of the fifteen republics, which made up of the pre-1991 Soviet Union accounting for over 60per cent of the GDP and half of the Soviet population, had to ensure the transition from socialism to a Laisez-Faire type of economy through a process of trial and error. Some of the former Socialist States of Central Europe began to experiment with a free market system, 2 years before Russia that has provided some insight into the effects of transition from Socialism to a free market economy but their experience could not be replicated fully in Russia as there were a number of differences between them and Russia in terms of political structure, economic institutions and cultural values. Even while experimenting with free market forces, Russia could not shake itself completely from the political culture and social structure with its Soviet past. The question of how well Russia’s fragile democratic and federal institutions would fare during the transition was a question mark all through since the Russian Presidents under the free regime were unwilling to loosen the tight control they exercised over parliament, regional office holders, mass media, courts and the civil society.

Soviet Economy in Retrospect

For nearly 60 years, the economy of the Soviet Union operated on the basis of central planning—state control over virtually all means of production and investment, production, and consumption decisions throughout the economy. Economic policy was made according to directives from the communist party, which controlled all aspects of economic activity. The central planning system left a number of legacies with which the Russian economy had to deal with in its transition to a market economy.

Much of the structure of the Soviet economy that operated until 1987 originated from the time of Stalin, with only few slight changes having been made between 1953 and 1987. Centralised plans were the chief mechanisms the Soviet government used to convert economic policies into programmes. According to these policies, the State Planning Committee (Gosplan) formulated countrywide output targets for stipulated planning periods. Regional planning bodies then adopted these targets for economic units such as state industrial enterprises, state farms (sovkhoz) and collective farms (kolkhoz), each of which had its own specific output plan. Central planning operated on the assumption that if each unit met or exceeded its plan, then equilibrium between demand and supply could be achieved. The role of government was to ensure that the plans were fulfilled. Responsibility for production flowed from the top to the bottom. At the national level, some 70 government ministries and state committees, each responsible for a production sector or subsector, supervised the economic production activities of units within their areas of responsibility. Regional ministerial bodies reported to the national-level ministries and controlled economic units in their respective geographical areas.

The plans incorporated output targets for raw materials and intermediate goods as well as final goods and services. In theory, though not in practice, the central planning system ensured a balance among the sectors throughout the economy. Under this kind of command economy, the state performed the allocation functions that prices perform in a market system. In the Soviet economy, prices were only an accounting mechanism. The government established prices for all goods and services based on the role of the product in the plan and on other non-economic criteria. This kind of administered pricing system produced anomalies. For example, the price of bread, a traditional staple of the Russian diet, was below the price of the wheat used to produce it. In some cases, farmers fed their livestock with bread rather than grain because bread cost less. In yet another such situation, rents for apartments were set very low to achieve social equity, yet housing was in extremely short supply. Soviet industries obtained raw materials such as oil, natural gas, and coal at prices below world market levels, encouraging waste.

However, the central planning system allowed Soviet leaders to marshal resources quickly in times of crisis, such as the Nazi invasion, and to reindustrialise the country during the postwar period. The rapid development of its defence and industrial base after the war permitted the Soviet Union to become a superpower, though this was achieved at the cost of the consumer who had to do with an extremely constricted choice of goods and services and stood as a poor cousin compared to his compatriots in the capitalist countries of the West.

The old socialist system was ineffective because the economy was centrally controlled. Power was concentrated in the hands of the elite of the communist party. The ultimate goal of Peristroika, introduced by Gorbachav was to increase the efficiency of material production while maintaining the essential elements of socialist society in the Soviet Union, the success of which depended on the success of glasnost. Secondly, it depended upon improved international cooperation. Glasnost, or openness, has been heralded by western leaders as signifying the death of socialism. However, according to Professor Rakos, Glasnost merely signified the recognition that people must be directly involved in that which they own (for example, the country’s resources). Rakos pointed out that under the old socialist system the Soviet Union’s bureaucratic interests resisted changes that would have had widespread benefits, if those were potentially disadvantageous to a sub-group, say, a ministry. Thus, technology was underutilised, efficiency was meaningless because an enterprise that lost money or produced useless goods was bailed out by the state, and workers got paid independent of the quantity and quality of output. These conditions resulted in a cycle of shortages of much-wanted consumer goods, lackadaisical management in work forces, money as a facilitator weak reinforcer and of little value in work. Glasnost represented an effort to enhance worker’s self-management so as to produce feelings of ownership. One example of that is the election of managers on Soviet collectives, in contrast to its western use to elect political leaders.

The second requirement for the success of Peristroika was increased international cooperation. Till its adoption, the Soviet Union’s isolation has resulted in too much resources being allocated to armament production and too little international cooperation. More international cooperation could produce hard currency, raw materials, scientific knowledge, technological sophistication, and other factors that would enhance benefits for individual citizens in ways that tended to keep them working, producing high quality consumer and social goods.

Shock Therapy

To convert the worlds’ largest state-controlled economy into a market-oriented system would have been extraordinarily difficult whatever the types of policies chosen. The policies chosen for this herculean task consisted of three major constituents, namely, (i) liberalisation (ii) stabilisation and (iii) privatisation.

The programmes of liberalisation and stabilisation were designed by Yeltsin’s deputy prime minister Yegor Gaidar, a 35-year-old liberal economist, inclined toward radical reform, and widely known as an advocate of “shock therapy.” Shock Therapy began days after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, when on 2 January 1992, Russian President Boris Yeltsin ordered the liberalisation of foreign trade, prices, and currency. This required removal of Soviet-era price controls in order to lure goods back into understocked Russian stores, removing legal barriers to private trade and manufacture, and cutting subsidies to state farms and industries while allowing foreign imports into the Russian market in order to break the power of state-owned local monopolies. The immediate results of liberalisation were hyper-inflation and the near bankruptcy of much of Russian industry.

The process of liberalisation would obviously create winners and losers, Among the winners were the new class of entrepreneurs and black marketers that had emerged under Mikhail Gorbachev’s perestroika. But liberalising prices meant that the elderly and others on fixed incomes suffered a steep fall in living standards, and people saw a lifetime of savings wiped out.

With inflation at double-digit rates per month as a result of sudden price liberalisation, macroeconomic stabilisation was enacted to curb this trend. Stabilisation, also called structural adjustment, is a harsh austerity regime—owing to tight monetary policy and fiscal policy—for the economy in which the government sought to control inflation. Under the Russian stabilisation programme, the government let most prices float, raised interest rates to record highs to as much as 250per cent, imposed heavy new taxes, sharply cut back on government subsidies to industry and construction, and made massive cuts in state welfare spending.

The rationale of the programme was to squeeze the built-in inflationary pressure out of the economy so that producers would begin making sensible decisions about production, pricing and investment instead of chronically overusing resources as was done in the Soviet Union in the 1980s that resulted in shortages of consumer goods by letting the market rather than central planners determine prices, product mixes, output levels, and the like, the reformers intended to create an incentive structure in the economy where efficiency and risk would be rewarded, and waste and carelessness punished. According to the reformers, removing the causes of chronic inflation, was a precondition for all other reforms: Hyper-inflation would wreck both democracy and economic growth, and only by stabilising the state budget could the government proceed to dismantle the Soviet planned economy and create a new capitalist Russia. However, these policies caused widespread hardship as many state enterprises found themselves without orders or working capital. A deep credit crunch shut down many industries and brought about a protracted depression.

Obstacles to the Smooth Transition to Capitalism in Russia

A major reason why Russia’s transition has been painful to a large extent is that the country launched a mammoth task of remaking both its Soviet-era political and economic institutions at one go. Equally daunting was the task of Russia in building a new national state following the disintegration of the Soviet Union. Russia faced a number of unique obstacles during the post-Soviet transition. These obstacles have left Russia on a far worse footing than other former Soviet Russia’s satellite countries of the west that were also going through dual economic and political transitions, such as Poland, Hungary, and the Czech Republic. These countries, however, have fared better since the collapse of the Soviet bloc between 1989 and 1991.

In its efforts to transform itself as a capitalist economy, Russia faces the following problems:

- One major problem facing Russia is the legacy of the Soviet Union’s enormous commitment to the Cold War. In the late 1980s, the Soviet Union was estimated to have allocated a quarter of its gross economic output to the defence sector. At least one out of every five adults in the Soviet Union was employed in the military-industrial complex in some regions of Russia, while as much as half of the workforce was employed in defence plants. The end of the Cold War and the cutback in military spending hit such plants very hard, and it was often impossible for them to quickly retool equipment, retrain workers, and find new markets to adjust to the new post-cold war realities and post-Soviet era. In the process of converting a sort of “wartime” industry into a peace-time industry, an enormous body of experience, qualified specialists and know-how has been lost, as the plants were sometimes switching from producing hi-tech military equipment to making kitchen utensils and the like.

- Another obstacle, partly related to the sheer vastness and geographical diversity of the Russian landmass, was the sizeable number of “mono-industrial” regional economies dominated by a single industrial employer that Russia inherited from the Soviet Union. The concentration of production in a relatively small number of big state enterprises meant that many local governments were entirely dependent on the economic health of a single employer; when the Soviet Union collapsed and the economic ties between Soviet republics and even regions were severed, the production in the whole country dropped by more than 50 per cent. Roughly half of Russia’s cities had only one large industrial enterprise, and three- fourths had no more than four. Consequently, the decrease in production caused tremendous unemployment and underemployment, creating traumatic problems to dependent families.

- Post-1991 Russia did not inherit a functioning system of social security and welfare provided by the government. Since Russian industrial firms were traditionally responsible for a broad range of social welfare functions—building and main-taining housing for their workforces, and managing health, recreational, educational, and similar facilities—the towns possessing few industrial employers were left heavily dependent on these firms, which were the mainstay of employment, for the provision of basic social services. Thus, economic transformation that brought about privatisation of industries created severe problems in maintaining social welfare, since local governments were unable to assume financial responsibility for these functions.

- Finally, there was the problem of human capital. The problem was not that the Soviet population was uneducated. Literacy was nearly universal, and the educational attainment level of the Soviet population was among the highest in the world with respect to science, engineering, and technical specialities. The former Soviet Union’s state enterprise managers were indeed highly skilled at coping with the demands on them under the Soviet system of planned production targets. But the incentive system built into state and social institutions of the Soviet era encouraged skill in coping with an intensely hierarchical, state-centered economy, but discouraged the kind of competitive risk-and-reward centered behaviour of market capitalism. For example, the directors of Soviet state firms were rewarded for meeting output targets under difficult conditions, such as uncertainty about whether, needed inputs would be delivered in time and in the right assortment. As seen earlier, they were also responsible for a slew of social welfare functions for their employees, their families, and the population of the towns and regions where they were located. Profitability and efficiency were well down the list of priorities of Soviet managers. Thus, almost no Soviet employees or managers had first-hand experience with decision-making in the conditions of a market economy. This lack of expertise and experience in the changed economic scenario for the managers brought in a host of human resource management problems.

In short, turning the cold war-era Soviet economy into a market-based peacetime economy without wrenching problems was simply impossible.

Economic Reform in the 1990s

The economic reforms of Russia in the 1990s were characterised by two fundamental and interd-ependent goals—macroeconomic stabilisation and economic restructuring. The transition from central planning to a market-based economy was sought to be ensured through these instruments of the country’s economic policy. Macroeconomic stabilisation involved the implementation of fiscal and monetary policies that promoted economic growth in an environment of stable prices and exchange rates. The latter called for establishing the commercial, legal, and institutional entities—private property, banks, and commercial legal codes—that would permit the economy to operate efficiently. Throwing open domestic markets to foreign trade and investment, and linking the economy with the rest of the world, was an important tool in realising these goals. The new government of the Russian Republic under Yeltsin had begun to address the problems of macroeconomic stabilisation and economic restructuring. But the results were mixed by mid-1996, as in the given circumstances, the goals of these measures seemed to be unrealistically high.

Macroeconomic Stabilisation Measures

The macroeconomic stabilisation programme had set out a number of policy measures to achieve stabilisation, such as sharp reductions in government spending, targeting outlays for public investment projects, defence, and producer and consumer subsidies; and also aimed at reducing the government budget deficit from its 1991 level of 20per cent of GDP to 9per cent of GDP by the second half of 1992 and to 3per cent by 1993. Government imposed new taxes and upgraded tax collection to increase state revenues. In the monetary sphere, the economic programme required the Russian Central Bank (RCB) to cut subsidised credits to enterprises and to restrict money supply growth. The programme aimed at reducing inflation from 12per cent per month in 1991 to 3per cent per month in mid-1993.

Economic Restructuring Measures

The government lifted price controls on 90per cent of consumer goods and 80per cent of intermediate goods immediately after the dissolution of the Soviet Union. In order to establish a realistic relationship between production and consumption that had been lacking in the central planning system, it raised administered prices on energy and food staples such as bread, sugar, vodka and dairy products.