4. Board of Directors: Selection, Compensation, and Removal

In this chapter, we examine how companies select, compensate, and remove board members. We start by examining the size of the market for directors and the qualifications of board members. Next, we discuss how companies identify gaps in the board’s capabilities and recruit individuals to fill those gaps. We then evaluate director compensation and equity ownership guidelines. Finally, we consider the resignation and removal of directors.

Market for Directors

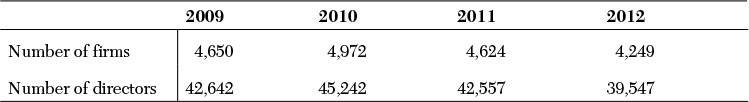

The United States has approximately 40,000 directors of large private and publicly traded corporations (see Table 4.1). The average director stays on a corporate board for seven years. Among companies that establish an age limit for serving on a board, the average mandatory retirement age is about 72 years. Although survey data from the National Association of Corporate Directors (NACD) indicates that board members are replaced through a combination of director evaluations and age limits, general observation suggests that board members tend to retire voluntarily.1 According to Audit Analytics, only about 2 percent of directors who leave the board are dismissed or not reelected.2

Source: Based on data collected by Equilar and computations by the authors.

Table 4.1 Number of Directors in the United States

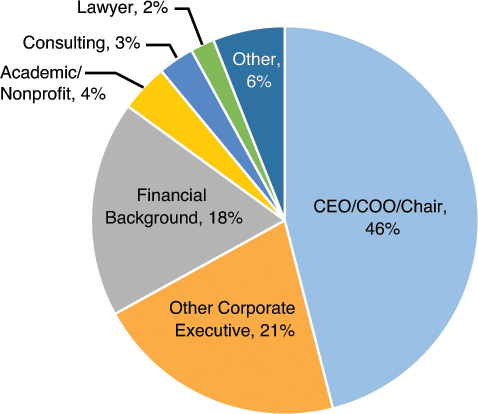

The typical board consists of a mix of professionals with managerial, functional, and other specialized backgrounds. Approximately half of newly elected directors have current or former experience as senior management (CEO, president, COO, chairman, or vice chairman). Twenty percent have experience in an operational or other functional position. The rest come from diverse backgrounds, including finance, consulting, law, academia, and nonprofits (see Figure 4.1).3

Note: “CEO/COO/Chair” also includes president and vice chair. “Other corporate executive” includes division heads and senior/executive vice presidents. “Financial background” includes CFO and treasurer, bankers, investment managers/investors, and accountants.

Source: Adapted from Spencer Stuart, “Spencer Stuart U.S. Board Index” (2013).

Figure 4.1 Background of new independent directors.

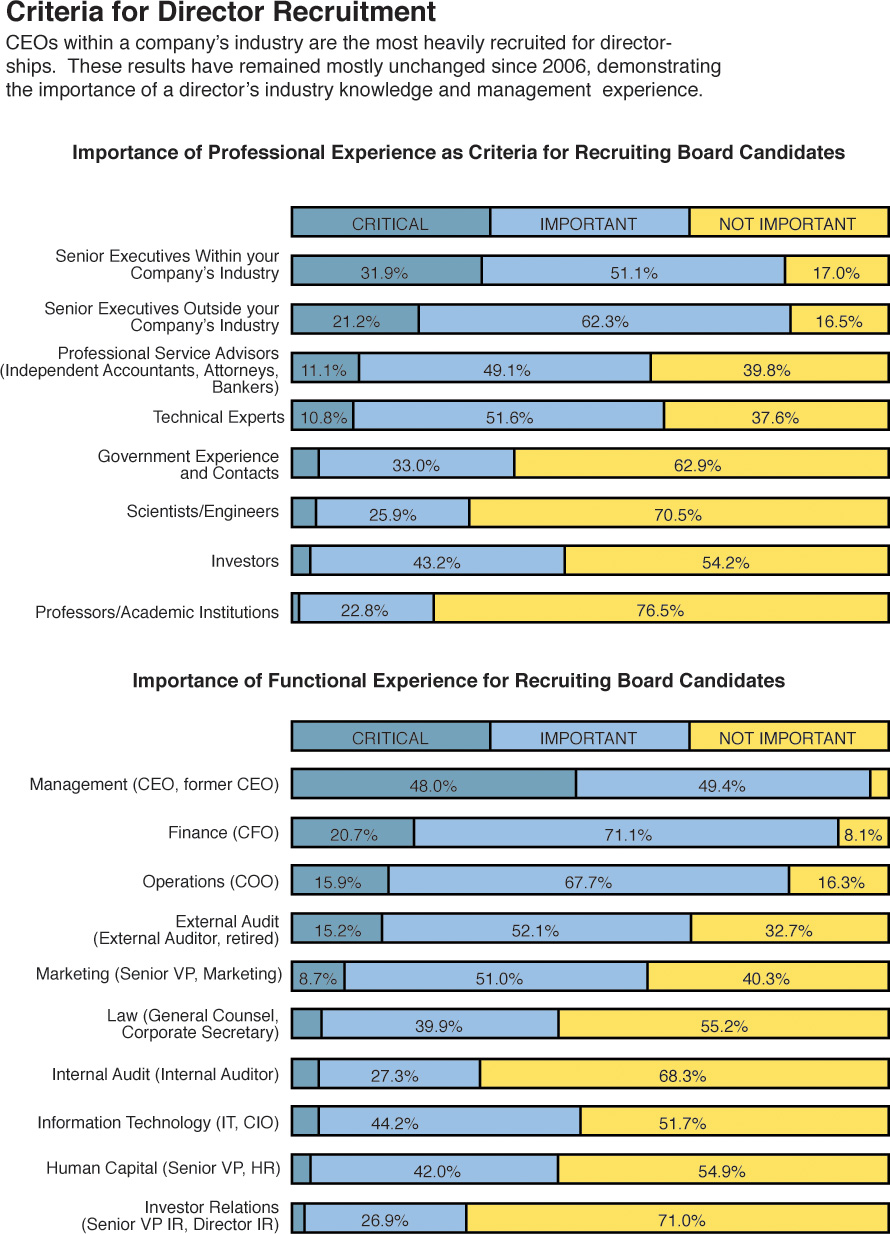

The most important qualification for directorship is relevant industry experience. According to the NACD, 83 percent of directors believe that industry experience is critical or important for recruiting new board candidates. Furthermore, directors have a strong preference to recruit executives with senior-level experience. Current and former CEOs, chief financial officers (CFOs), and chief operating officers (COOs) are the most sought after candidates to serve on the board in terms of function background. (Figure 4.2 illustrates this more completely.)

National Association of Corporate Directors (NACD) and The Center for Board Leadership, “2009 NACD Public Company Governance Survey” (2009).

Figure 4.2 Criteria for director recruitment.

Companies look for a diverse mix of personal and professional backgrounds beyond these qualifications. According to Spencer Stuart, directors most in demand as board candidates are those with ethnically diverse backgrounds (56 percent) and women (54 percent). Highly sought after professional qualifications include financial, international, risk management, information technology, marketing, regulatory, and digital or social media experience.4

Because of the critical role that board members play in the governance process, the quality of individuals who are elected to the board should have a direct correlation with the quality of advice and oversight the board provides to management. In the following sections, we will consider four specialized types of directors: directors who are active CEOs, directors with international experience, directors with specialized knowledge, and diverse directors.

Active CEOs

Active CEOs sit on an average of 0.6 external boards. In recent years, this number has decreased. Spencer Stuart reports a 40 percent decline in the number of active CEOs serving as directors between 2003 and 2013. The reasons cited for this trend are increased workload from active positions, too much time spent traveling for directorships, and limits placed on the number of outside directorships by current employers. More than three-quarters of all S&P 500 companies now limit outside directorships for CEOs, a policy that was not widely in effect a decade ago. Companies have responded to this trend by recruiting new directors who are executives below the CEO level or who are retired CEOs. According to Spencer Stuart, retired CEOs comprise 23 percent, and lower-level corporate executives comprise 21 percent of new independent directors, up from 12 percent each 10 years ago.5

Directors with CEO-level experience offer a useful mix of managerial, industry, and functional knowledge. These individuals can contribute to multiple areas of oversight, including strategy, risk management, succession planning, performance measurement, and shareholder and stakeholder relations. To this end, investors generally react favorably to the appointment of directors with CEO-level experience. Fich (2005) found that the stock market reaction to the appointment of a new outside director is more positive when that director is an active CEO than when he or she is not.6 However, this does not necessarily mean that directors with CEO-level experience are better board members than directors with other backgrounds. Fahlenbrach, Low, and Stulz (2010) found no evidence that the appointment of an outside CEO to a board positively contributes to future operating performance, decision making, or the monitoring of management.7

Survey data also suggests that active CEOs might not be the best board members. According to a study by Heidrick & Struggles and the Rock Center for Corporate Governance at Stanford University, nearly 80 percent of corporate directors believed that active CEOs are no better than non-CEO board members. Although respondents valued the strategic and operating expertise of CEO directors, when asked about their undesirable attributes, a full 87 percent responded that active CEOs are too busy with their own companies to be effective board members. Respondents also criticized active CEOs for being unable to serve on time-consuming committees, for being unable to participate in meetings on short notice, and for being too bossy, for being poor collaborators, and for not being good listeners.8

Finally, the research suggests that the appointment of active CEOs as directors might lead to increased CEO compensation. O’Reilly, Main, and Crystal (1988) found a strong association between CEO compensation levels and the compensation levels of outside directors, particularly members of the compensation committee. They argue that, consistent with social comparison theory, committee members refer in part to their own compensation levels as a benchmark for reasonable pay, leading to a distorted view of “fair market value” when approving CEO pay packages.9 Faleye (2011) also found that the appointment of active CEO directors is associated with higher CEO compensation levels.10

International Experience

As companies expand into international markets, it is important that the board understand how the company might be impacted from strategic, operating, financial, risk, and regulatory perspectives. For this reason, directors with knowledge of local market conditions are highly valued. These directors have contacts with key government decision makers and business executives who can help with supply chain development, manufacturing, customer development, and distribution. This network should help a company enter or expand into a new market by minimizing risk and lowering the cost of executing an international strategy. To this end, Masulis, Wang, and Xie (2012) found that the presence of foreign independent directors on a board is associated with better cross-border acquisitions when the target company is from the foreign director’s home country.11

Boards are becoming more international. According to Spencer Stuart, 29 percent of newly elected directors have international work experience, and 9 percent are of foreign birth. Larger corporations in particular are more likely to have international directors; 55 percent of the largest 200 companies in the S&P 500 have at least one non-U.S. director, compared with 47 percent five years ago.12 The trend of recruiting international directors is not limited to the United States. A study by Egon Zehnder found that, across Europe, the proportion of foreign board members rose from 23 percent in 2006 to 32 percent in 2012.13

Some evidence suggests that the demand for international knowledge exceeds the available supply. In a separate report, Egon Zehnder compared the percentage of revenues that a company earns outside the United States to the percentage of directors with international experience (the logic being that if a company derives half of its revenue from outside the United States, roughly half of the board should have some international experience). They found that international revenue (37 percent) exceeds international board representation among S&P 500 firms when representation is measured by citizenship (7 percent) or work experience (14 percent).14 This suggests that boards might have insufficient international experience, a potential competitive obstacle as U.S. firms expand into new markets.

Special Expertise

Companies also have demand for directors with special expertise that matches the functional or situational needs of the firm. For example, a technological firm needs directors who are experts in the industry to advise on research, development, and production (academics in engineering, computer science, medicine, and natural sciences are commonly used in this capacity). These directors might not have the background to oversee certain business or compliance functions, but their presence is critical for the commercial success of the firm. For example, defense contractor Lockheed Martin counts among its directors a former strategic commander for the U.S. Navy and a former deputy secretary for Homeland Security. Both of these individuals serve on a standing committee to oversee “classified business activities and the security of personnel, data, and facilities.”15 Similarly, companies in dire financial or operating condition might benefit from directors with experience in a corporate turnaround or financial restructuring. Specialized experience can also help companies that face regulatory or legal challenges and companies that regularly engage in mergers, acquisitions, or divestitures.

Given the increasingly important role that information technology plays in supply chain management and customer interaction through the Internet, social media, and mobile technology, more companies are recruiting directors with experience in these areas (known as “digital directors”). Russell Reynolds found that among a sample of large corporations in 2013, 19 percent of newly appointed directors in the United States and 8 percent of newly appointed directors in Europe had digital backgrounds, up sharply from 12 percent and 2 percent, respectively, two years before.16 According to a member of that firm, “I have never seen such an acceleration of demand for specific board expertise.”17 Faleye, Hoitash, and Hoitash (2013) found that industry expertise at the board level is positively associated with innovation and that it leads to higher firm value among firms where innovation is an important part of the corporate strategy.18

In some cases, individuals with specific expertise are not formally elected to the board but instead participate in board meetings as observer or advisory directors. This practice appears to be common among financial institutions. These directors do not vote on corporate matters, so they are shielded from the potential liability that comes with being an elected director. However, they are available to advise the corporation on important matters. For example, a venture capital firm might invite a partner to sit on the board and an associate to attend board meetings as a nonvoting observer (see the following sidebar). According to survey data, 17 percent of companies have one or more board observers.19

Diverse Directors

Companies might seek directors of diverse ethnic origin or female directors when they believe diversity of personal perspective contributes to board deliberation or decision making. According to Spencer Stuart, women and ethnic minorities are the two most sought-after groups of directors. Still, their representation on corporate boards remains low: only 18 percent of directors at large corporations are women, 9 percent African-American, 5 percent Hispanic, and 2 percent Asian.21 Several cultural and societal factors contribute to this result. For example, individuals from these groups might lack access to the closed networks that lead to board appointment; structural imbalances might exist between supply and demand, given the low representation of these groups among senior management teams; the turnover among existing directors that is required for new board seats to become available is low; and personal biases or prejudices might prevent qualified candidates from receiving an equal opportunity for appointment.

Furthermore, research by Heidrick & Struggles suggests that practitioners don’t agree on the value of diversity on the board. Ninety percent of female directors believe that women bring special attributes to the board, whereas only 56 percent of male directors believe this to be true. Similarly, 51 percent of women believe that having three or more female directors on a board makes it more effective, whereas only 12 percent of male directors hold this opinion.22 These are considerable perception gaps that need to be researched.

Despite the difference of opinions, companies have made significant effort toward recruiting diverse board members. Ninety-three percent of companies have at least one female director on the board, and 87 percent have an ethnic minority director.23 According to the NACD, more than 75 percent of directors believe that ethnic and gender diversity is a critical factor in board recruitment.24 (We discuss the impact of diversity on corporate performance in Chapter 5, “Board of Directors: Structure and Consequences.”)

Professional Directors

Professional directors are individuals whose full-time careers are serving on boards of directors. They might be retired executives, consultants, lawyers, financiers, or politicians who bring extensive expertise based not only on their professional background but also on the multitude of current and previous board seats. For example, Vernon Jordan (a former legal advisor to Bill Clinton) is considered by some to be a professional director, having served on more than a dozen corporate boards, including American Express, Ashbury Automotive, J.C. Penney, and Xerox.25 After a successful career in retailing, Allan Leighton of the United Kingdom retired from executive positions at the age of 47 and decided to pursue a career as a professional director (calling the move “going plural”). Subsequently, he served as a board member or an advisor to Royal Mail, Lastminute.com, Scottish Power, and BSkyB.26 According to a survey by Heidrick & Struggles and the Rock Center for Corporate Governance at Stanford University, 63 percent of companies have one or more professional directors on their board.27

Professional directors might be effective as advisors and monitors, given their extensive experience on boards. They have participated in multiple governance systems and have likely witnessed both successes and failures. They might also have more time to dedicate to their board responsibilities because they do not need to balance them with the demands of a “day job.” In addition, professional directors bring extensive personal and professional networks.28

However, relying on professional directors can be risky. Because they serve on multiple boards simultaneously, professional directors tend to be busy. As we see in the next chapter, “busy” directors are associated with lower governance quality. Professional directors might not have the motivation to be effective monitors if they are attracted to the position for its reputational prestige (such as bragging to their social peers), if they do not attend to all of their directorships with equal effort, or if they view serving on multiple boards as a form of “active retirement.” Perhaps validating these concerns, Masulis and Mobbs (2014) found that directors with multiple directorships distribute their efforts unequally, dedicating more time to prestigious corporations than to others.29 Finally, professional directors might lack independence and may be unwilling to stand up to management or fellow directors if they substantially rely on their director fees for income.30

Disclosure Requirements for Director Qualifications

In 2010, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) amended Regulation S–K to require expanded disclosure about the qualifications of directors. Companies must now disclose the specific experience, qualifications, and attributes that make an individual qualified to serve as a director. Companies must also disclose directorships that the individual held during the previous 5 years (instead of only current directorships), legal proceedings involving the director during the previous 10 years, and disciplinary sanctions imposed by regulatory bodies. This information is intended to improve shareholder decisions in a director election.

Regulation S–K was also amended to require disclosure of whether the company has a policy regarding boardroom diversity and, if so, how diversity is considered in identifying director nominees. The SEC did not define diversity, but it suggested that the term could be broadly defined to include differences of viewpoint, professional experience, education, and skills, as well as race, gender, and national origin (see the following sidebar).31

Director Recruitment Process

As we discussed in Chapter 3, “Board of Directors: Duties and Liability,” director recruitment is a key responsibility of the nominating and governance committee. The committee is responsible for identifying qualified candidates to serve on the board, interviewing and selecting candidates to be put before shareholders for a vote, hiring a search firm to assist in the recruitment process (if necessary), and managing the board evaluation process.

The process should begin by evaluating the needs of the company and identifying gaps in the board’s desired capabilities. A list is then assembled of potential candidates whose qualifications fill the identified gaps. The method for assembling this list varies among companies. Some rely extensively on the personal and professional networks of existing board members and the CEO. Others rely on a third-party consultant or search firm to assemble a list of candidates among a broader pool. According to the NACD, approximately 50 percent of companies use a search firm. However, this varies with firm size. Eighty-two percent of large companies (with market capitalization greater than $10 billion) use a search firm, while smaller firms are considerably less likely to do so.35

Although intuition might suggest that board candidates identified by search firms would be more qualified on average than candidates identified through a personal network (because they come from a broader pool and are less likely to be selected because of personal biases of existing board members), this is not necessarily the case. Existing directors often have an extensive network that is equal in breadth and insight to the network a third-party consultant uses. To our knowledge, no rigorous studies have compared the qualification of board candidates deriving from each source, primarily because the role of search firms in selecting directors is not a required disclosure by firms.

The director recruitment process differs from the recruitment process for senior executives in two key manners. First, it is more informal and reliant upon professional networks. Many director candidates are initially referred through the personal and professional connections of current board members (or the CEO) rather than through third-party recruiters. Second, the sequence of steps differs. When recruiting executives, the company assembles a list of top candidates, interviews them, and then makes a selection based on an evaluation of which is best qualified. When recruiting directors, the company assembles a list of top candidates, ranks them in preferential order, and approaches the candidates one at a time. In effect, the board (or the nominating and governance committee) decides who it wants to nominate before meeting face-to-face with the candidates. This requires a more careful evaluation of the skills and experience of the individual, without the benefit of meeting in advance. The meeting is as much an invitation to join the board as it is an interview. This is done because it is considered inappropriate to approach a qualified candidate (one who has been highly successful in a professional career) only to reject him or her in favor of another. It is not clear whether a competitive process would improve board quality or whether the most qualified candidates would choose not to engage in interviews.

The composition of the board should satisfy the diverse strategic, operating, and functional needs of the company. It’s also important that the culture of the board reflect that of the organization and that board members have good rapport among themselves and with senior management. Recruiters recommend against companies selecting directors based on regulatory and compliance expertise. (One exception is that a company embroiled in extensive legal troubles might specifically bring on a director to help the company navigate through this period.) Generally, directors can be taught compliance more readily than they can be taught domain expertise. Perhaps for this reason, more than half of all boards are open to recruiting directors with no previous board experience.36

According to the NACD, directors are satisfied with the board recruitment process. Eighty-seven percent of directors believe their companies are effective or highly effective in handling director recruitment, and only 13 percent believe they are not effective.37

Finally, the director recruitment process is unique in that companies do not tend to engage in succession planning among board members. According to survey data, only half of companies (49 percent) begin the process of identifying potential candidates to serve on the board before an outgoing director announces plans to step down. Fewer than half (40 percent) develop a formal written document to outline the skills, competencies, and experiences required of new director candidates.38 Although companies might feel that the board can continue to function with the loss of a single member, it seems that director succession planning should be a key responsibility of the nominating and governance committee (see the following sidebar). This is especially true if the company requires directors with a rarified skill set.

Director Compensation

Directors require compensation for the time, responsibility, and expense of serving as directors. Recruiters suggest that most directors would be unwilling to do this work on a pro bono basis. (Directors at nonprofits is one exception.) Therefore, the amount of compensation must be sufficient to attract and retain qualified professionals with the knowledge required to advise and monitor the corporation. It should also be structured to motivate directors to act in the interest of shareholders and stakeholders. As a result, understanding the payment structure is important for evaluating the incentives directors have to contribute to a sound governance system.

Director compensation covers not only time directly spent on board matters but also the cost of keeping the director’s calendar open in case of unexpected events, such as an unsolicited takeover bid, financial restatement, or emergency CEO succession. In addition, it covers the personal risk that comes with serving on a board. For example, although we have seen that directors are unlikely to be responsible for out-of-pocket payments for legal liability or expenses, lawsuits still demand substantial time and attention. They also bring reputational risk and take an emotional toll on those involved.43

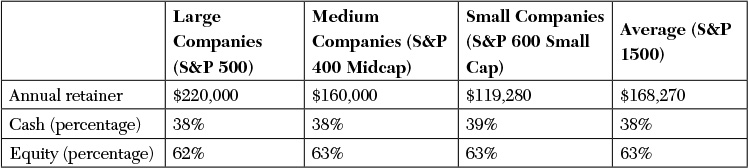

Directors of companies in the S&P 1500 Index receive annual compensation of $168,270, on average. Compensation packages comprise approximately 38 percent cash annual retainer and 62 percent equity (stock options and stock awards). Director compensation is $220,000 at large-sized companies, $160,000 at medium-sized companies, and $119,280 at small companies (see Table 4.2).44

Compensation mix does not vary significantly by company size. Modest variation exists across industries, with a lower mix of equity awards in stable industries such as consumer goods and utilities and a higher mix of equity in research-intensive industries such as technology and healthcare. This suggests that some relation exists between compensation risk and reward, based on the nature of the industry.

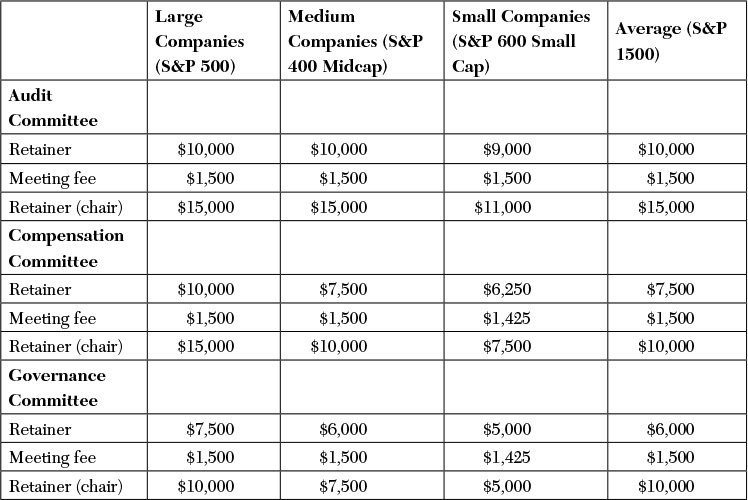

Many companies pay directors supplemental fees for serving on committees. These figures are in addition to the compensation figures cited in Table 4.2. Committee fees might be an annual retainer or might be awarded on a per-meeting basis. Committee fees average between $10,000 and $15,000 per year. Fees are higher for directors who serve on the audit committee because committee members are required to have financial expertise. They also bear a higher risk of being named in shareholder litigation, and they might have a bigger workload when assigned to this committee (see Table 4.3).

Nonexecutive chairmen and lead independent directors also receive supplemental pay. The average total compensation for nonexecutive chairmen is approximately 60 percent higher than that paid to other directors. Lead independent directors receive total compensation that is approximately 12 percent higher. These pay multiples hold true for small, medium, and large companies and are intended to compensate for the increased responsibilities associated with leadership roles.45

One important question is whether the level of director fees is reasonable or appropriate, from the perspective of shareholders. As is the case with most other compensation issues, this is a difficult question to answer. One simple way to think about it is to consider the opportunity cost to these directors. If they were not directors, what might they earn for their services? Directors spend approximately 20 hours per month on board-related duties.46 At $200,000 per year, this translates into an hourly rate of approximately $800. This is comparable to the hourly rate of individuals with similar professional backgrounds (in fields such as business, finance, consulting, and law).

From the corporation’s perspective, the cost of board member compensation can be a significant portion of the total direct cost of maintaining a governance system. (The auditor fee represents another significant direct cost.) According to a study of companies in Silicon Valley, small companies incur total costs for nonexecutive board compensation of around $750,000, and large companies incur $1.8 million. These figures represent 0.5 percent of revenue for the small companies and less than 0.1 percent at the large companies. They also represent 0.16 percent of the market capitalization of the small companies and 0.02 percent of the large companies.47 Although smaller companies get less leverage out of the direct cost of their board, they are perhaps in a stage of growth in which strong monitoring systems and sound strategic advice are more important. Considering the importance that many experts place on having effective corporate governance, these costs are not very significant.48

Another important question is whether the mix of director compensation is appropriate. To answer this, shareholders should consider various factors, including the company’s growth prospects, industry, risk profile, and cash position. For example, a small startup might offer a mix that is heavily comprised of stock options if the company is cash starved, in growth phase, and can benefit from the strategic advice of directors. For these companies, cash is critical for survival, and shareholders likely prefer that the cash be invested in the company, not paid out to board members. This type of pay structure also attracts certain types of directors: those who can deal with risk, who have the valuable strategic insights for the company, and who are willing to work hard to make the company a success. Conversely, large, steadily growing companies might choose to offer a high cash component along with some type of equity payment (such as restricted stock units).

Finally, in evaluating compensation, investors should remember that directors are not managers and that their compensation mix should be consistent with their serving an advisory and oversight function (see the following sidebar). We discuss the incentive value of compensation for executives in Chapter 8, “Executive Compensation and Incentives.”

Ownership Guidelines

Many companies require that directors maintain personal ownership positions in the company’s common stock during their tenure on the board (ownership guidelines). Such a requirement is intended to align the interests of directors with those of the common shareholders they represent, thereby giving directors an incentive to monitor management. For somewhat obvious reasons, shareholders (and governance experts) look favorably upon companies whose directors own stock. However, it is an open question what level of ownership is sufficient to mitigate agency problems between the board and shareholders.

According to Equilar, approximately 78 percent of the 100 largest companies in the United States have some form of director ownership guidelines.52 Companies can structure these guidelines in a few ways. Some companies require that directors accumulate and retain a specified amount of company stock, either through open-market purchases or through the retention of restricted stock grants. The minimum amount of stock that directors are required to hold is defined as a multiple of their annual cash retainer. Other companies require that directors hold restricted stock grants for a minimum number of years. Directors are not required to meet these guidelines immediately upon assuming their board seat but are instead given time to accumulate the minimum ownership amounts. For example, directors at Pitney-Bowes have five years to accumulate their ownership requirement of 7,500 shares (approximately $250,000 in value).53 Directors at Hewlett-Packard are given five years to accumulate shares valued at five times their annual retainer (approximately $500,000 in share value).54 On average, companies give directors five years to meet ownership guidelines.55

Requiring directors to own company shares might not always be a good idea. First, directors are not managers. They are advisors and monitors. Paying directors similar to management might compromise their ability to provide effective oversight. A director might be unwilling to approve a project or an acquisition that risks depressing the company share price in the near term, even if the project will create long-term value, if the director’s personal financial portfolio cannot accommodate stock price volatility. In this way, stock ownership might encourage directors to make decisions through the lens of their personal financial interest instead of the long-term interest of the corporation. Similarly, directors with a large equity position might be less likely to oppose low-level manipulation of accounting results (such as the smoothing of earnings or accelerated booking of revenue) if they believe that stock price will suffer from their detection. Finally, ownership guidelines are not usually calibrated for the wealth of the individual director. A guideline that specifies a $100,000 investment carries a different weight for a director with a net worth of $1 million than it does for a director with a net worth of $100 million.

The evidence on this issue is mixed. Mehran (1995) did not find a relationship between director stock ownership and either increased operating performance or increased firm value.56 However, Mikkelson and Partch (1989) demonstrated that when a director with a major ownership position sits on the board, the company is more likely to agree to a takeover bid. This suggests that director stock ownership might decrease management entrenchment.57 Cordeiro, Veliyath, and Neubaum (2005) and Fich and Shivdasani (2005) found that equity ownership among directors is positively associated with future stock price performance and firm value.58 They saw this as evidence that equity-based compensation gives directors greater incentive to monitor managerial self-interest. However, Brick, Palmon, and Wald (2006) found a positive correlation between director compensation and CEO compensation and that above-average compensation is associated with lower future firm performance. They saw this as evidence of “mutual back scratching or cronyism.”59

Board Evaluation

A board evaluation is the process by which the entire board, its committees, or individual directors are evaluated for their effectiveness in carrying out their stated responsibilities. The concept of a board evaluation was among the key recommendations of the Higgs Report, which stated that “every board should continually examine ways to improve its effectiveness” and remains a recommendation of the U.K. Corporate Governance Code.60 In the United States, annual board evaluations are a listing standard of the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE), which requires that the nominating and governance committee “oversee the evaluation of the board and management.” Furthermore, each committee (audit, compensation, and nominating and governance) is required to perform its own self-evaluation.61

That said, companies are not required to perform an evaluation of individual directors. Some companies do this, but many do not. According to the NACD, only 38 percent of companies evaluate the performance of individual directors. Large corporations are more likely to do so (47 percent) than small companies (30 percent).62

Evaluations—whether at the board, committee, or individual level—are important because they enable the board to understand whether it is meeting its own expectations for performance. For example, a board might discover that it is effective in compliance and regulatory oversight but that it dedicates insufficient time to overseeing the company’s operations or strategy. Evaluations also help the board to understand the performance of directors and whether they are exhibiting the skills, knowledge, and expertise that is expected of them. If a director is not adequately engaged, the evaluation process can be an effective tool for initiating a discussion about improvement or replacement.

Furthermore, board evaluations vary significantly in terms of the process and scope. The following is a list of some of the choices companies make in designing evaluations:

• Are the board and committees evaluated only as a whole or at the level of the individual director?

• Is the board evaluated against the company’s own policies or against the practices of highly successful peers?

• Are individual directors subjected to peer evaluation, self-evaluation, or a combination?

• Are evaluations conducted by interview or by survey?

• Are evaluations conducted by an internal officer (such as a human resources executive), an outside law firm, or a third-party consultant?

In addition, evaluations can address a variety of topics, including these:

• Composition—Does the board have the expertise it needs to fulfill all its responsibilities? Is the process for selecting new directors satisfactory? Are individual board members contributing broadly and in their areas of expertise? Is the board taking full advantage of the skills and experiences of its directors?

• Accountability—Is the board effective in fulfilling its responsibilities? Has the board set an appropriate strategy? Has the board ensured the relationship integrity among the company’s vision, mission, strategy, business model, and key performance metrics? Has the board set realistic long-term objectives? Does the board successfully monitor performance? Does the board successfully monitor and advise the CEO?

• Information—Is the board getting the information it needs? Is information accurate and timely?

• Meetings—Are meetings appropriately structured? Is sufficient time dedicated to all necessary topics? Is discussion open and honest? Are directors adequately prepared?

• Relations—Are directors honest and open in their discussion with one another? Are directors honest and open in their discussion with management? Do boardroom relations encourage optimum decision making? Does management receive appropriate support from the board? Does management receive sufficient oversight from the board?63

Finally, just because an evaluation is comprehensive in scope does not mean that it leads to effective outcomes.64 Practically speaking, it is difficult for the professionals conducting the evaluation to give constructive feedback, even if they are third-party consultants. The consultants who perform these evaluations indicate that many directors, given the success they have achieved in their professional lives, do not welcome commentary about their shortcomings, and consultants’ advice for improvement is often ignored. This is unfortunate, as it can lead to outcomes in which ineffective directors remain on the board when they should either improve or retire. To this end, a survey by Corporate Board Member magazine found that almost a quarter of officers have directors on their boards whom they feel should be replaced. Thirty-six percent of those respondents believe the directors lack the necessary skill set, 31 percent believe that the directors are not engaged, and the remainder believe that the directors either are unprepared for meetings or have been on the boards too long.65 For governance quality to improve, these board members should hear this feedback firsthand.

Removal of Directors

For a variety of reasons, a director might want to leave a corporate board. These reasons can be benign (such as a desire to pursue new opportunities or retire) or more troublesome (such as a fundamental disagreement with fellow board members over the direction of the company—see the following sidebar). Similarly, the company might have either benign or troublesome reasons for wanting to replace a director. The company could decide that, after many years of service, it is time to find a new director who can look at strategy and operations from a different perspective. Or the company might feel that a particular director is negligent in his or her services and is therefore unfit to oversee the organization.

That said, a director leaving unwillingly is extremely rare. (Audit Analytics counts only 106 dismissals out of the entire population of public directors in 2009.)66 Generally directors leave voluntarily. However, it is usually unclear what has prompted a director to step down when that director leaves for reasons other than reaching a mandatory retirement age.

The board may not remove a fellow director, even if the director is performing poorly. Shareholders may remove a director at the annual meeting. This is rare, however, outside of a contested election. During 2013, only 44 directors failed to win majority support.72 Shareholders may also remove a director between annual meetings, if permitted under the company’s charter. This, too, is rare. The most common way a director is removed is not to be renominated for election (see the following sidebar).73

To our knowledge, a well-developed body of research on the removal of directors does not exist. Most studies focus on the resignation of directors following a significant negative event, such as a lawsuit or financial restatement, and not removal during the due course of business. For example, Srinivasan (2005) found that director turnover is significantly higher for firms that undergo a major financial restatement (48 percent during the subsequent three-year period), compared to firms that undergo a technical restatement (18 percent). Furthermore, he found that these board members tend to lose their other directorships as well. The phenomenon is most pronounced for audit committee members.75

Similarly, Arthaud-Day, Certo, Dalton, and Dalton (2006) found that director and audit committee members are 70 percent more likely to turn over if the company experiences a restatement. They explained that forced turnover of senior officers sends a signal that the company is disassociating itself from its past errors and that it is committed to restructuring control and oversight mechanisms to prevent future recurrence. They noted that although these actions do not fully repair reputational damage, they are meant to reassure shareholders that they can rely on the company going forward.76

Finally, people debate whether directors and officers of failed companies should be elected to directorships at other firms or whether their failure to properly monitor one firm should disqualify them from other boards. To this end, shareholders raised questions when Xerox named former chairman and CEO of Citigroup Charles Prince to its board and when Alcoa named former chairman and CEO of Merrill Lynch Stanley O’Neil to its board and audit committee. Nonexecutive directors at Lehman Brothers, Wachovia, Washington Mutual, Bear Stearns, and AIG all gained new directorships after their companies failed.77 On one hand, failure brings meaningful experience that might be valuable in another corporate setting. On the other hand, if the failure was caused by a lapse in judgment or ineffective monitoring, legitimate questions arise over whether a possible recurrence is worth the risk to the corporation. According to one expert, “When selecting individuals to oversee an organization, what criteria should we be using other than their previous performance on a corporate board? [I]f there’s no accountability here, then what is the system of accountability?”78

Still, survey evidence suggests that business leaders are forgiving of directors of failed companies, certainly more than they are of the senior executives of those same companies. According to one report, only 37 percent of executives and directors believe that the former CEO of a company that experienced significant accounting or ethical problems can be a good board member at another company. By contrast, 67 percent of respondents believe that directors of such a company can be a good board member elsewhere. When asked to elaborate, respondents suggest that the CEO is held to a higher standard of accountability, given his or her position of leadership. By contrast, directors are presumed to have less involvement in potential violations and are also seen as able to learn from mistakes of this nature. However, these opinions are not universal.79

Endnotes

1. National Association of Corporate Directors and the Center for Board Leadership, “NACD Public Company Governance Survey” (2008). Accessed October 14, 2010. See www.nacdonline.org.

2. Mark Cheffers and Don Whalen, “Audit Analytics, Director Departures: A Five-Year Overview” (2009). Accessed October 14, 2010. See www.auditanalytics.com/0000/custom-reports.php.

3. Spencer Stuart, “Spencer Stuart U.S. Board Index” (2013). Accessed March 30, 2015. See https://www.spencerstuart.com/research-and-insight/us-financial-services-board-index-2013.

4. Ibid.

5. Ibid.

6. Eliezer M. Fich, “Are Some Outside Directors Better than Others? Evidence from Director Appointments by Fortune 1000 Firms,” Journal of Business 78 (2005): 1943–1971.

7. Rüdiger Fahlenbrach, Angie Low, and René M. Stulz, “Why Do Firms Appoint CEOs as Outside Directors?” Journal of Financial Economics 97 (2010): 12–32.

8. Heidrick & Struggles and the Rock Center for Corporate Governance at Stanford University, “2011 Corporate Board of Directors Survey” (2011). Accessed April 25, 2015. See http://www.gsb.stanford.edu/faculty-research/publications/2011-corporate-board-directors-survey.

9. Charles A. O’Reilly III, Brian G. Main, and Graef S. Crystal, “CEO Compensation as Tournament and Social Comparison: A Tale of Two Theories,” Administrative Science Quarterly 33 (1988): 257–274.

10. Olubunmi Faleye, “CEO Directors, Executive Incentives, and Corporate Strategic Initiatives,” Journal of Financial Research 34 (2011): 241–277.

11. Ronald W. Masulis, Cong Wang, and Fei Xie, “Globalizing the Boardroom—The Effects of Foreign Directors on Corporate Governance and Firm Performance,” Journal of Accounting and Economics 53 (2012) 527–554.

12. Spencer Stuart (2013).

13. Egon Zehnder International, “2012 European Diversity Analysis” (2012). Accessed April 25, 2015. See http://www.egonzehnder.com/files/european_diversity_analysis_2012_1.pdf.

14. Egon Zehnder, “2014 Global Board Index Achieving Global Board Capability: Keeping Pace with Global Opportunity” (2014). Accessed October 1, 2014. See http://www.egonzehnder.com/global-board-index.

15. Lockheed Martin, Form DEF 14A, filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission April 21, 2015.

16. Russell Reynolds, “Digital Economy, Analog Boards: The 2013 Study of Digital Directors” (2013). Accessed December 10, 2014. See http://www.russellreynolds.com/content/digital-economy-analog-boards-2013-study-digital-directors.

17. Joann S. Lublin, “Wanted: More Directors with Digital Savvy,” Wall Street Journal Online (May 15, 2013, Eastern edition): B.6.

18. Olubunmi Faleye, Rani Hoitash, and Udi Hoitash, “Industry Expertise on Corporate Boards,” Northeastern University D’Amore-McKim School of Business Research Paper No. 2013-04 (2013). Accessed April 25, 2015. See http://ssrn.com/abstract=2117104.

19. Heidrick & Struggles and the Rock Center for Corporate Governance at Stanford University (2011).

20. Findlaw, “Nomination and Observer Agreement—Excite Inc. and Intuit Inc” (June 25, 1997). Accessed November 4, 2010. See http://corporate.findlaw.com/contracts/corporate/nomination-and-observer-agreement-excite-inc-and-intuit-inc.html.

21. Spencer Stuart (2013).

22. Boris Groysberg and Deborah Bell, “2010 Board of Directors Survey, Sponsored by Heidrick & Struggles and Women Corporate Directors (WCD)” (2010). Accessed October 7, 2010. See www.heidrick.com/publicationsreports/publicationsreports/hs_bod_survey2010.pdf.

23. Spencer Stuart (2013).

24. National Association of Corporate Directors and The Center for Board Leadership, “NACD Public Company Governance Survey” (2009). Last accessed November 10, 2010. See www.nacdonline.org/.

25. American Express Co., Inc., Form DEF 14A, filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission March 15, 2007.

26. Wikipedia, “Allan Leighton.” Accessed November 14, 2010. See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/allan_leighton.

27. Heidrick & Struggles and the Rock Center for Corporate Governance at Stanford University (2011).

28. Eugene H. Fram, “Are Professional Board Directors the Answer?” MIT Sloan Management Review 46 (2005): 75–77.

29. Ronald W. Masulis and Shawn Mobbs, “Independent Director Incentives: Where Do Talented Directors Spend Their Limited Time and Energy?” Journal of Financial Economics 111 (2014): 406–429.

30. However, one could argue that professional directors have greater incentive for this same reason. If they do a poor job at one firm, they might lose multiple directorships.

31. Securities and Exchange Commission, “17 CFR Parts 229, 239, 240, 249, and 274. Proxy Disclosure Enhancements [Release Nos. 33-9089; 34-61175; IC-29092; File No. S7-13-09].” Last accessed November 4, 2010. See www.sec.gov/rules/final/2009/33-9089.pdf.

32. Analog Devices, Inc., Form DEF 14A, filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission January 30, 2014.

33. Covidien, Form DEF 14A, filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission January 24, 2014.

34. Wells Fargo Inc., Form DEF 14A, filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission March 18, 2014.

35. National Association of Corporate Directors and the Center for Board Leadership (2009).

36. Spencer Stuart (2013).

37. National Association of Corporate Directors and the Center for Board Leadership (2009).

38. Heidrick & Struggles and the Rock Center for Corporate Governance at Stanford University (2011).

39. Korn/Ferry Institute, “34th Annual Board of Directors Study” (2007). Last accessed November 4, 2010. See www.kornferry.com/publication/9955.

40. National Association of Corporate Directors and the Center for Board Leadership (2009).

41. John Harry Evans, Nandu J. Nagarajan, and Jason D. Schloetzer, “CEO Turnover and Retention Light: Retaining Former CEOs on the Board,” Journal of Accounting Research 48 (2010): 1015–1047.

42. Timothy J. Quigley and Donald C. Hambrick, “When the Former CEO Stays on as Board Chair: Effects on Successor Discretion, Strategic Change, and Performance,” Strategic Management Journal 33 (2012): 834–859.

43. One example is the board of the Hewlett-Packard Company following the “pretexting” scandal in 2006. See Alan Murray, “Directors Cut: H-P Board Clash over Leaks Triggers Angry Resignation,” Wall Street Journal (September, 6, 2006, Eastern edition): A.1.

44. Equilar Inc., “2013 S&P 1500 Board Profile Committee Fees (Part 1) Featuring Commentary by Society of Corporate Secretaries & Governance Professionals and Meridian” (2013). Accessed May 5, 2015. See http://info.equilar.com/rs/equilar/images/equilar-2013-board-fees-report.pdf?mkt_tok=3rkmmjwwff9wsrois6xjzkxonjhpfsx57eokx.

45. Equilar Inc., “2013 S&P 1500 Board Profile Committee Fees (Part 2) Featuring Commentary by Semler Brossy” (2013). Accessed December 11, 2014. See http://info.equilar.com/rs/equilar/images/equilar-2013-sp-1500-board-profile-committee-fees-report.pdf?mkt_tok=3rkmmjwwff9wsroisqrmzkxonjhpfsx54ugpx6k3lmi%2f0er3fovrpufgji4fssbli%2bsldweygjlv6sgfs7ffmalt0lgfxby%3d.

46. Spencer Stuart (2013).

47. Compensia, “Silicon Valley 130: Board of Directors Compensation Practices” (October 2007). Accessed April 15, 2015. See www.compensia.com/surveys/sv130-board.pdf.

48. The Sarbanes–Oxley Act of 2002 contributed to a significant rise in director compensation in recent years. Linck, Netter, and Yang (2009) found that director compensation at large companies rose almost 50 percent between 1998 and 2004 (measured as a percentage of sales). They also found a substantial increase in the cost of director and officer (D&O) insurance premiums (which are paid by the firm). See James S. Linck, Jeffry M. Netter, and Tina Yang, “The Effects and Unintended Consequences of the Sarbanes–Oxley Act on the Supply and Demand for Directors,” Review of Financial Studies 22 (2009): 3287–3328.

49. The Coca-Cola Company, Form DEF 14A, filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission March 13, 2007.

50. Ibid.

51. SPX Corporation, Form DEF 14A, filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission March 17, 2004.

52. Equilar Inc., “2012 Director Stock Ownership Guidelines Report,” (2013). Accessed July 28, 2014. See https://insight.equilar.com.

53. Pitney-Bowes Inc., Form DEF 14A, filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission March 27, 2014.

54. Hewlett Packard, Form DEF 14A, filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission February 3, 2014.

55. Equilar Inc., “2012 Director Stock Ownership Guidelines Report,” (2013).

56. Hamid Mehran, “Executive Compensation Structure, Ownership, and Firm Performance,” Journal of Financial Economics 38 (1995): 163–184. As cited in Clifford Holderness, “A Survey of Blockholders and Corporate Control,” Economic Policy Review—Federal Reserve Bank of New York 9 (2003): 51–63.

57. Wayne H. Mikkelson and Megan Partch, “Managers’ Voting Rights and Corporate Control,” Journal of Financial Economics 25 (1989): 263–290. As cited in Holderness (2003).

58. James J. Cordeiro, Rajaram Veliyath, and Donald O. Neubaum, “Incentives for Monitors: Director Stock-Based Compensation and Firm Performance,” Journal of Applied Business Research 21 (2005): 81–90. Eliezer M. Fich and Anil Shivdasani, “The Impact of Stock-Option Compensation for Outside Directors on Firm Value,” Journal of Business 78 (2005): 2229–2254.

59. Ivan E. Brick, Oded Palmon, and John K. Wald, “CEO Compensation, Director Compensation, and Firm Performance: Evidence of Cronyism?” Journal of Corporate Finance 12 (2006): 403–423.

60. Financial Reporting Council “The UK-Corporate Governance Code” (2014). Accessed March 31, 2015. See https://www.frc.org.uk/our-work/publications/corporate-governance/uk-corporate-governance-code-2014.pdf.

61. New York Stock Exchange, “Corporate Governance Standards.” Accessed March 31, 2015. See http://nysemanual.nyse.com/lcmtools/platformviewer.asp?selectednode=chp_1_4_3_6&manual=%2flcm%2fsections%2flcm-sections%2f.

62. National Association of Corporate Directors, “2013–2014 NACD Public Company Governance Survey” (Washington, D.C.: National Association of Corporate Directors, 2014).

63. Adapted from Richard M. Furr and Lana J. Furr, “Will You Lead, Follow, or Develop Your Board as Your Partner?” (2005). Accessed May 5, 2015. See http://www.leader-values.com/article.php?aid=593.

64. We are not aware of any large-scale research studies on the performance consequences of board member evaluation methods.

65. Corporate Board Member and PricewaterhouseCoopers LLC, “Special Supplement: What Directors Think 2009, Corporate Board Member/PricewaterhouseCoopers LLC Survey” (2009). Accessed May 5, 2015. See http://rss.boardmember.com/MagazineArticle_Details.aspx?id=4171.

66. Cheffers and Whalen (2009).

67. Anup Agrawal and Mark A. Chen, “Boardroom Brawls: An Empirical Analysis of Disputes Involving Directors,” Social Science Research Network (2011): 1–60. Accessed May 5, 2015. See http://ssrn.com/abstract=1362143.

68. Fair, Isaac & Co., Form 8-K, filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission June 1, 2001.

69. Surge Components, Inc., Form 8-K, filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission August 1, 2001.

70. Agrawal and Chen (2011).

71. Rüdiger Fahlenbrach, Angie Low, and Rene M. Stulz, “The Dark Side of Outside Directors: Do They Quit When They Are Most Needed?” (July 31, 2013). Charles A. Dice Center Working Paper No. 2010-7; Swiss Finance Institute Research Paper No. 10-17; ECGI - Finance Working Paper No. 281/2010. Accessed April 25, 2015. See http://ssrn.com/abstract=1585192.

72. United States Research Team, “2013 Proxy Season Review United States,” ISS (2013). Accessed December 12, 2014. SEE http://www.issgovernance.com/library/united-states-2013-proxy-season-review/.

73. William Meade Fletcher, “§ 351. Common Law Right to Remove for Cause,” Fletcher Cyclopedia of the Law of Corporations (St. Paul: Homson/West, 1931).

74. Roger Parloff, “Inside Job,” Fortune (July 7, 2008): 94–108.

75. Suraj Srinivasan, “Consequences of Financial Reporting Failure for Outside Directors: Evidence from Accounting Restatements and Audit Committee Members,” Journal of Accounting Research 43 (2005): 291–334.

76. Marne L. Arthaud-Day, S. Trevis Certo, Catherine M. Dalton, and Dan R. Dalton, “A Changing of the Guard: Executive and Director Turnover Following Corporate Financial Restatements,” Academy of Management Journal 49 (2006): 1119–1136.

77. Susanne Craig and Peter Lattman, “Companies May Fail, but Directors Are in Demand,” Dealbook.Nytimes.com (September 14, 2010).

78. Rakesh Khurana, as cited in Ibid.

79. Heidrick & Struggles and the Rock Center for Corporate Governance at Stanford University (2011).