12. Institutional Shareholders and Activist Investors

Despite their ownership positions, institutional investors have only indirect influence on company affairs. The majority of their influence must be exerted through the board of directors, whom they elect to govern on their behalf. However, institutional shareholders can still be powerful: They can communicate their opinions directly to management and the board. If the response they receive is not satisfactory, they can seek to have directors removed, vote against proxy proposals sponsored by management, put forth their own proxy measures, or express their dissatisfaction by selling their shares (“voting with their feet”).

In this chapter, we review these points in detail. We examine the broad universe of institutional investors to understand their objectives and the methods they use to gain influence. We consider the role that proxy advisory firms play in influencing the annual voting process. In addition, we consider the impact of recent and potential regulatory changes, including the trend toward “shareholder democracy” and corporate engagement.

The Role of Shareholders

As discussed in Chapter 1, “Introduction to Corporate Governance,” the shareholder perspective of the corporation states that the primary purpose of the corporation is to maximize wealth for owners. This implies that the question of effective governance, from the standpoint of shareholders, is quite simple: Governance practices should seek to create better alignment between management and shareholder interests, thereby reducing agency costs and increasing shareholder value. Therefore, effective governance focuses on the best way to create this alignment and increase shareholder value.

However, this is an oversimplification of the problem. Disagreements arise among shareholders about the best way to structure a firm’s governance because shareholders themselves are not a homogeneous group.1 They differ in terms of several important attributes. For example, shareholders do not have a single, common investment horizon. Long-term investors might tolerate significant swings in quarterly earnings and share price if they believe that the decisions management is making will ultimately yield a higher level of profitability. Investors with a shorter investment horizon might prefer that management focus on maximizing near-term earnings and stock price.

Shareholders also have different objectives. A large mutual fund institution might only care about the economic results of the corporation. An institutional investor that represents a specific constituent—such as a union pension fund or socially responsible investment fund—might focus on how economic results are achieved and the impact on various stakeholders.

Furthermore, not all shareholders exhibit the same activity level. On one end of the spectrum are passive investors, such as index funds.2 These investors attempt to generate returns that mirror the returns of a predetermined market index. They might be less attentive to firm-specific performance and governance matters. On the other end of the spectrum are active investors. These investors are active in the trading of company securities and care greatly about individual firm outcomes. They might also try to influence corporate affairs (by meeting with management, lobbying to have board members removed, voicing concern about compensation practices, and advancing policy measures through the company proxy).3 Investors who try to influence governance-related matters within the corporation are referred to as activist investors.

Finally, shareholders vary by size. In contrast to small funds, large institutional investors tend to have significant financial resources that they can dedicate to governance matters. For example, BlackRock, with $4.7 trillion in assets under management, has about 20 people in a group that directs proxy voting. These individuals—based in the United States, Europe, Japan, Hong Kong, and Australia—coordinate voting policies and activities across 85 national markets and the 14,000 companies in which BlackRock invests.4

The heterogeneity of shareholder groups creates a coordination problem. Differences in investment horizon, investment objective, activity level, and size make it difficult for shareholders to coordinate efforts to influence management and the board toward a common goal. In some cases, shareholders can work at cross-purposes to one another, even though they share an objective of improving corporate performance.

Coordination is further complicated by the well-known free rider problem. Shareholder actions—such as proxy contests and shareholder-sponsored proxy proposals—require the expenditure of resources. While one institutional investor bears the cost of these efforts, the benefits are enjoyed broadly by all shareholders (who are said to enjoy a “free ride”). For example, an activist institutional fund might lead a successful campaign to destagger a company board or remove economically harmful antitakeover protections. Although all shareholders enjoy the outcome of this effort, the activist investor alone incurs the costs. The asymmetry of cost and payout creates a disincentive for any one firm to take action and can result in underinvestment by institutional investors to improve corporate governance.

Shareholders suffer from having only indirect influence over the corporation (see the following sidebar). They must rely principally on the board of directors to exert direct influence. The board hires and fires the CEO, sets compensation, oversees firm strategy and risk management, oversees the work of the external auditor, writes company bylaws, and negotiates for a change of control. If shareholders do not believe that the board is sufficiently representing their interests in these matters, they must either persuade them to change policies or seek to have them removed. As we saw in Chapter 11, “The Market for Corporate Control,” removing the board is a cumbersome and costly process.

Blockholders and Institutional Investors

A blockholder is an investor with a significant ownership position in a company’s common stock. No regulatory statute classifies an investor as a blockholder, although researchers generally define a blockholder as any shareholder with at least a 1 to 5 percent stake. A blockholder can be an executive, a director, an individual shareholder, another corporation, a foreign government, or an institutional investor (see the next sidebar). Institutional investors include mutual funds, pension funds, endowments, hedge funds, and other investment groups. For the purposes of this chapter, we limit our discussion to nonexecutive and institutional blockholders. (Chapter 9, “Executive Equity Ownership,” discusses executive blockholders and Chapter 14, “Alternative Models of Governance,” discusses family-controlled businesses.)

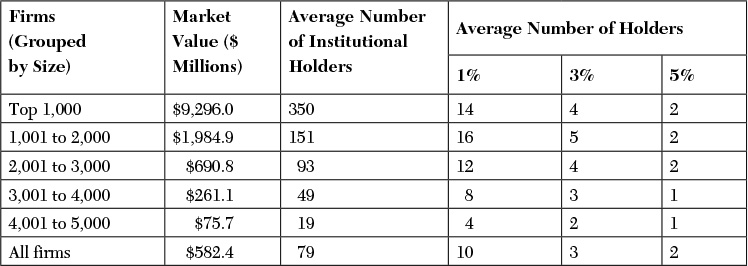

U.S. regulations require that corporations disclose major shareholders to the public. According to Thomson Reuters, 95 percent of publicly listed companies have an institutional shareholder with at least a 1 percent ownership position, 85 percent with at least a 3 percent position, and 74 percent with at least a 5 percent position (see Table 12.1).8 Furthermore, the data suggests that blockholders tend to retain their ownership position over time. Barclay and Holderness (1989) found that firms that have a blockholder at one point in time are likely to continue to have a blockholder five years later. They also found that the ownership position of the largest blockholder tends to increase over time.9

Median values. Sample includes 5,347 firms during 2013.

Source: Thomson Reuters Institutional Holdings (13F) Database.

Table 12.1 Blockholders among U.S. Corporations

Blockholders are predominantly institutions rather than individuals. Among a sample of randomly selected manufacturing firms with blockholders, Mehran (1995) found that 23 percent are individuals, and 77 percent are corporate and institutional blockholders.10 Approximately 70 percent of the shares of publicly traded corporations are held by institutional investors.11

If they decide to act, institutional investors and blockholders are in a position to impose governance reforms on corporations. Their significant voting stakes can determine the outcome of a contested director election or proxy proposal. They can change the outcome of a heated takeover battle or prod a company to put itself up for sale or change strategy. If they hold a large enough position, they can gain board representation and directly influence strategy, risk management, executive compensation, and succession planning.

However, the blockholders’ influence likely depends on the nature of the investment, the nature of the investor, and the relationship between the investor and the corporation. For example, Toyota likely has a different relationship with the auto suppliers it invests in than does a large institutional owner or an activist hedge fund. As we saw in Chapter 9 when we examined managerial equity ownership, block ownership has the potential to either improve or impair firm performance, depending on whether the blockholder treats ownership as an incentive to better the business or uses the position of influence for private gain.

The research literature has examined the impact of block ownership on firm performance. Barclay and Holderness (1989) found that large blocks of shares (at least 5 percent of a company’s stock) trade at a 16 percent premium to open-market prices.12 This indicates that block ownership is perceived to have value either because the acquirer believes it will provide the influence needed either to monitor and improve firm outcomes or to extract some type of private gain from the corporation. The research does not, however, demonstrate that block ownership actually translates to superior performance. McConnell and Servaes (1990) found no relationship between block ownership by an outside investor and a company’s market-to-book value.13 Mehran (1995) also did not find a relationship between block ownership and market value or between block ownership and firm performance.14 This suggests that the presence of outside blockholders is not associated with improvements in firm performance. In aggregate, however, the research is inconclusive on this point.15

Researchers have also studied the relationship between block ownership and governance quality. Core, Holthausen, and Larcker (1999) found that CEO compensation is lower among firms in which an external shareholder owns at least 5 percent of the company shares.16 Similarly, Bertrand and Mullainathan (2000) examined the relationship between representation by a blockholder on the board of directors and “pay for luck.” They found that companies with blockholder directors are less likely to give pay increases for profit improvements that result from industry conditions outside the executive’s control (such as changes in commodity prices).17 Aggarwal, Erel, Ferreira, and Matos (2011) found that increases in institutional ownership positively improve firm-level governance and shareholder protections in international markets. They also found that firms with higher levels of institutional ownership are more likely to terminate a poorly performing CEO and exhibit improvements in valuation over time. These results suggest that active shareholder monitoring can compel a company to adopt better governance standards.18

Furthermore, Mikkelson and Partch (1989) found that companies with an external blockholder on the board of directors are more likely to be the target of a successful acquisition.19 At the same time, they found that if the external blockholder is not on the board, the company is no more likely to receive an acquisition offer or to accept the offer. This suggests that a combination of concentrated ownership and board representation might be effective in decreasing management entrenchment.

Institutional Investors and Proxy Voting

Publicly traded corporations are required by state law to hold an annual meeting of shareholders to elect the board of directors and transact other business that requires shareholder approval. In the U.S., shareholders are provided advance notice of the annual meeting through a written proxy statement, and they vote their shares on ballot items in person or by proxy over the Internet, via the phone, or by mail.

Because of their size, institutional investors are in a better position than individuals to impose governance changes through the proxy voting process. They might exercise this influence by voting against management recommendations on company-sponsored proxy matters, such as director elections, auditor ratification, equity-based compensation plans, and proposed bylaw amendments. Furthermore, they might sponsor or vote in favor of shareholder resolutions that recommend or require bylaw amendments or policy changes not sought by the corporation. (We discuss shareholder-sponsored resolutions in the next section.)

In 2003, the SEC began to require that registered institutional investors develop and disclose proxy voting policies and disclose their votes on all shareholder ballot items.23 The voting records of registered institutions are available to their beneficial owners through Form N-PX. If shareholders believe the institution is overly supportive of management, they can put pressure on it to take a tougher stance or shift their investment to another fund. (Hedge funds are not registered with the SEC and are exempt from these regulations.)

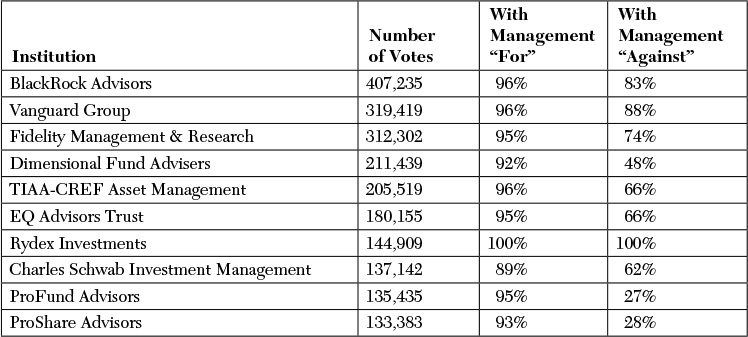

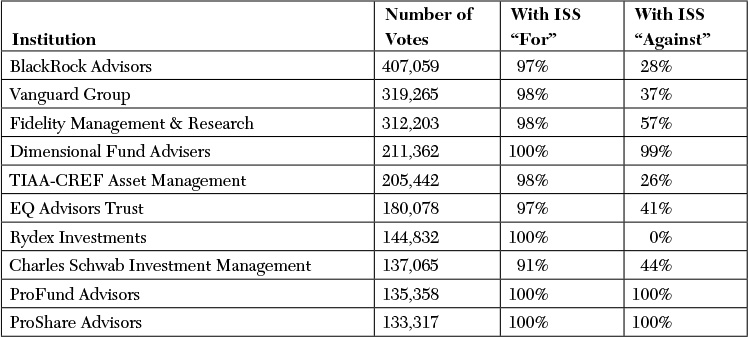

According to data from Institutional Investor Services (ISS), institutional investors vote in line with management recommendations about 95 percent of the time when management is seeking a vote “for” a proposal and 56 percent of the time when management is seeking a vote “against” a proposal. Among the 10 institutional investors with the largest number of votes, Rydex votes with management the most (100 percent when management recommends both in favor of and against an issue), Charles Schwab votes with management the least when management is in favor of a proposal (89 percent), and ProFund Advisors votes with management the least when management is against a proposal (27 percent).24 (See Table 12.2.)

Includes the 10 institutional investors with the largest number of votes, based on Form N-PX 2013 filings.

Source: Data from ISS Voting Analytics (2013). Calculation by the authors.

Table 12.2 Institutional Investor Voting Record (Voting with Management)

It is not clear whether these levels of support are appropriate. On one hand, many proxy proposals are routine, including most director elections, ratification of the external auditor, and the approval of various noncontroversial bylaw amendments. In these cases, no significant governance impact might occur from regularly voting in favor of these matters. On the other hand, it is plausible that routinely voting in accordance with management recommendations is not consistent with fiduciary oversight on behalf of institutional shareholders. Beneficial owners are ultimately responsible for determining whether fund managers vote in their best interest.

Activist Investors

Loosely speaking, an activist investor is a shareholder who uses an ownership position to actively pursue governance changes at a corporation. Any investor can employ an activist strategy, including a union-backed pension fund; an institutional investor with an environmental, religious, or social mission; a hedge fund; or an individual investor with outspoken beliefs. Activists use lobbying efforts to increase leverage and influence corporate governance outcomes beyond what can be achieved by simply voting shares in the proportion of their ownership position. Although activists might have a stated objective of improving shareholder value, they also might have secondary motives that are not value enhancing for shareholders over the long term.

Activists use a variety of mechanisms to influence corporate policy, including sponsoring proposals on the proxy, proxy contests (threatened or actual), pressure through the media and other public forums, and direct engagement.

Under SEC Rule 14a-8, a shareholder owning at least $2,000 or 1 percent in market value of a company’s securities for at least one year is eligible to submit a shareholder proposal. The shareholder must continue to hold the shares through the annual meeting and present the proposal in person at the meeting. Shareholders are limited to submitting one proposal at a time, which is due by a company-specified deadline, generally 120 days before the annual meeting. The company is entitled to exclude shareholder proposals that violate certain restrictions. These include proposals that would violate federal or state law or that deal with functions under the purview of management, the election of directors, the payment of dividends, or other substantive matters. Furthermore, the company can reject a proposal if it relates to a “personal grievance [or] special interest . . . which is not shared by the other shareholders at large.” Also, the company is entitled to exclude proposals that deal with “substantially the same subject matter” as another proposal on the proxy in the preceding five calendar years that received only nominal support.25

In recent years, shareholder proposals have focused primarily on board structure and antitakeover protections (39 percent), social policy issues (39 percent), and executive compensation (22 percent). Individual activists are the most active sponsor of shareholder resolutions, filing 40 percent of the total between 2006 and 2014, followed by labor-affiliated groups (32 percent), religious and other social responsibility investors (27 percent), and other institutional investors (1 percent).26

Shareholders have mixed results gaining majority approval for their proxy proposals. According to Institutional Shareholder Services, shareholder-sponsored proposals that garnered majority support on average in 2013 included proposals to destagger the board of directors (80 percent support), to end or reduce supermajority requirements (72 percent), and to adopt majority voting requirements (58 percent). Shareholder-sponsored proposals that did not receive majority support on average included proposals to give shareholders the right to call special meetings (42 percent), to act by written consent (41 percent), and to nominate directors for election to the board (“proxy access,” 32 percent). Proposals to require a separation between the chairman and CEO also did not receive majority support (31 percent).27

Shareholders can also influence corporate policy through a proxy contest. In a proxy contest, an activist shareholder nominates its own slate of directors to the company’s board (known as a dissident slate). The proxy contest represents a direct attempt to gain control of the board and alter corporate policy, and it is usually attempted in conjunction with a hostile takeover. As we discussed in Chapter 11, proxy contests require significant out-of-pocket expense by the activist shareholder, including purchasing the list of shareholders, preparing and distributing proxy materials, and soliciting a favorable response from key institutional investors. The cost and risk of failure substantially limit the frequency of proxy contests.28 Still, many contests that make it to a vote are successful. According to Institutional Shareholder Services, among 23 proxy contests in 2013, the dissident slate won seats 13 times, lost 7 times, and settled with management 3 times.29

Shareholder activism remains a highly controversial topic. Proponents of activism argue that companies with an engaged shareholder base are more likely to be successful in the long term. Active shareholders reduce agency problems, limit management entrenchment, and combat complacency by pressuring corporate officials to put the interests of shareholders first. Under this argument, activists are a necessary element of the market for corporate control. Opponents argue that shareholder activism is a guise for disruptive behavior that takes managerial and board attention away from substantive corporate matters and the pursuit of long-term value enhancement. In its extreme form, opponents liken activism to extortion that weakens corporations through reckless changes to strategy, capital structure, and asset mix in order to boost stock prices in the short term.

With these competing narratives in mind, we discuss various forms of shareholder activism, including activism by pension funds, socially responsible investment funds, and hedge funds.

Pension Funds

Public pension funds manage retirement assets on behalf of state, county, and municipal governments. Examples include the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS), New York State and Local Retirement System, and California State Teachers’ Retirement System (CalSTRS). Private pension funds manage retirement assets on behalf of trade union members. The largest trade union is the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO), comprising more than 50 national unions and 12 million workers. Other trade unions include the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, the Service Employees International Union, and the United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners of America. Pension assets are held in trust, and the management of these funds is overseen by a board of trustees whose sole purpose is to meet the financial obligations to trust beneficiaries.

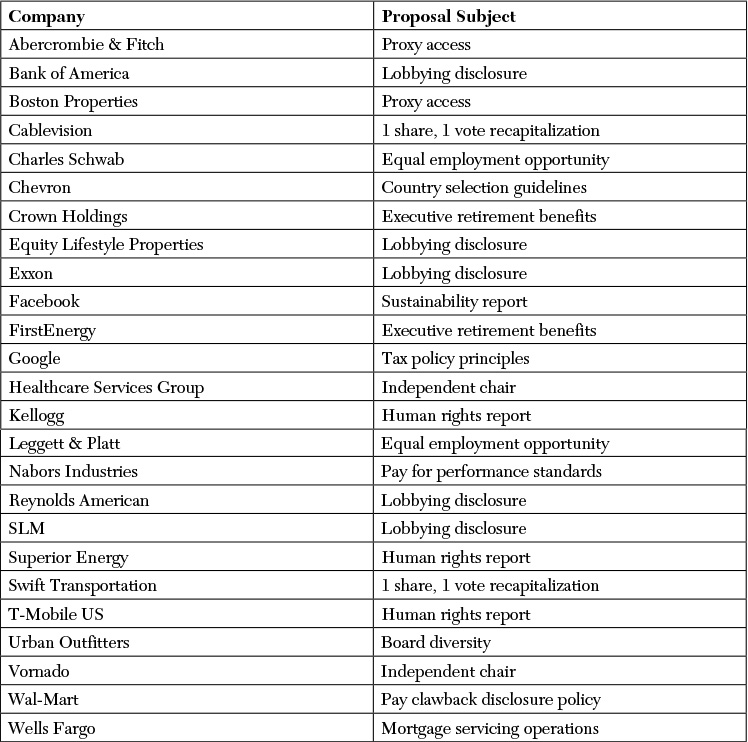

Pension fund administrators are active participants in the proxy voting process. As noted earlier, more than 40 percent of shareholder proxy proposals are sponsored by a union-backed or public pension fund. However, pension activism is not limited to proxy items that the organization has sponsored. Funds also take vocal positions on proposals that other institutions have sponsored. For example, the AFL-CIO keeps a scorecard of what it considers “key votes.” The 2014 scorecard recommended an affirmative vote on 25 proxy measures, including requirements for an independent chairman, proxy access, lobbying disclosure, and other policy reform (see Table 12.3).

Shareholder proposals “for” are consistent with the AFL-CIO Proxy Voting Guidelines.

Source: AFL-CIO, “Key Votes Survey,” (2014). Accessed May 5, 2015. See http://www.aflcio.org/content/download/65871/1747351/2013+AFL-CIO+Key+Votes+Survey.pdf.

Table 12.3 AFL-CIO Key Vote Scorecard (2014)

Some research suggests that union pension funds might not place a priority on maximizing financial returns for their beneficiaries but instead use their ownership position to support union- and labor-related causes. In a highly controversial study, Agrawal (2012) examined the voting record of the AFL-CIO between 2003 and 2006. He found that the AFL-CIO is significantly more likely to vote against directors at companies that are in the middle of a labor dispute, particularly when the AFL-CIO represents the workers. He concluded that “union pension funds cast proxy votes in part as a means of pursuing union labor objectives, rather than maximizing shareholder value alone.”30

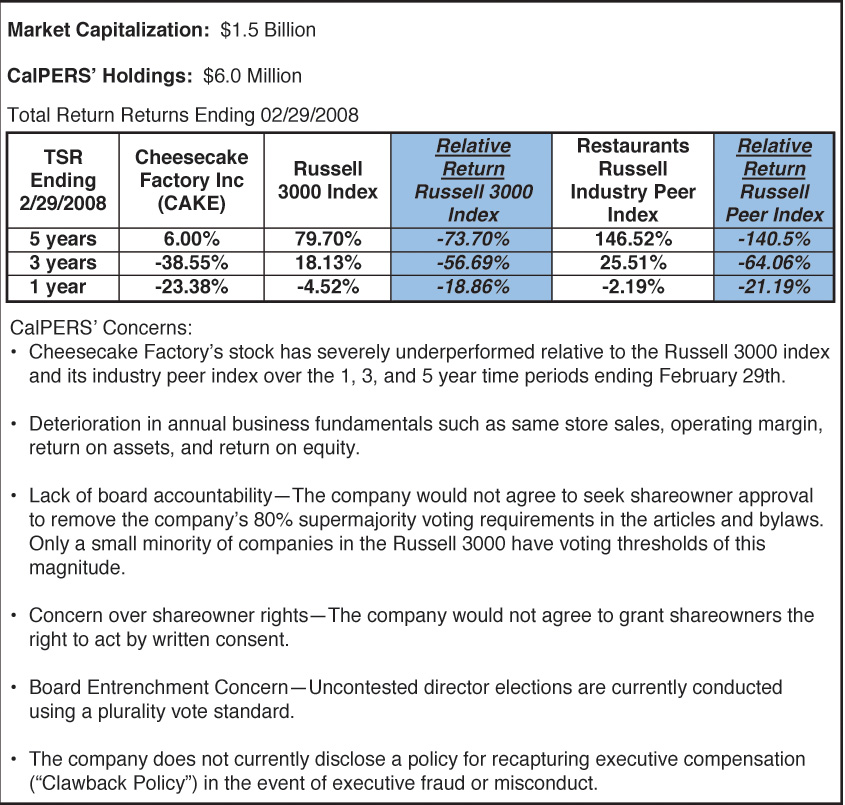

The evidence also suggests that pension fund activism has only a moderate impact on long-term corporate performance. Barber (2007) examined whether CalPERS activism increased shareholder value. His sample included all companies that made the pension fund’s annual “focus list” from 1992 to 2005. Companies on the focus list included those that CalPERS believed exhibited especially poor corporate performance and governance quality (see Figure 12.1). He found only marginal increases in shareholder value on the day CalPERS announced that a company was on the list, indicating that the market expected only a moderate impact from CalPERS intervention. Over the long term, Barber (2007) found practically no excess positive returns. He commented that “long-run returns are simply too volatile to conclude that the long-run performance of focus-list firms is unusual.” This suggests either that CalPERS did not select the right targets for its activism, that it did not have the ability to influence the governance choices at these firms, or that CalPERS’s alternative governance features were no better than the existing governance structure.31 As a result, the influence of public pension funds, although visible, is not well established. (In 2010, CalPERS discontinued the practice of using a public focus list, choosing instead to pursue direct communication with companies.)32

Social Responsibility and Other Stakeholder Funds

Social responsibility and other stakeholder funds cater to investors who value specific social objectives and want to invest only in companies whose practices are consistent with those objectives. Examples of social responsibility include fair labor practices, environmental sustainability, and the promotion of religious or moral values. By one estimate, more than 150 socially responsible mutual funds exist, totaling more than $300 billion in assets.33

Socially responsible funds vary in the extent to which they engage in activism to achieve their objectives. Some funds limit their activism to abstaining from investments in companies that violate their social values. Other funds actively attempt to change corporate practices. For example, Walden Asset Management claims on its Web site, “We do not subscribe to the simplistic view that some companies are ‘socially responsible’ while others are not. Instead, Walden seeks to build portfolios that not only adhere to a client’s risk/return objectives, but are also comprised of companies that best reflect their environmental, social and governance (ESG) priorities. Going further, Walden engages in shareholder advocacy on behalf of our clients to strengthen corporate responsibility and accountability.”34

According to Proxy Monitor, shareholders submitted 136 resolutions related to social and environmental objectives at Fortune 250 companies in 2014. Of these, 135 were defeated, and 1 was approved with the support of the board. On average, social and environmental proposals receive low levels of support (between 5 and 20 percent).35

The low approval rate of resolutions related to social causes suggests that these investors do not hold considerable influence over the proxy voting process. Nevertheless, even failed shareholder initiatives can still be an effective tool for influencing governance outcomes if they are coupled with other public and behind-the-scenes efforts to compel policy change (see the following sidebar).

The research literature is inconclusive regarding whether socially responsible investment funds achieve their dual objectives of advocating a social mission and generating financial returns on behalf of shareholders. Geczy, Stambaugh, and Levin (2005) found that socially responsible mutual funds significantly underperform comparable indices. However, the authors acknowledged that their model did not take into account the “nonfinancial utility of ‘doing good.’” That is, the social benefit that restricting investment might have on corporate behavior was not included.38 Similarly, Renneboog, Ter Horst, and Zhang (2008) found that socially responsible mutual funds in the United States, the United Kingdom, and many European and Asian countries underperform their respective benchmarks by 2.2 percent to 6.6 percent per year. However, they found that risk-adjusted returns are not significantly different from comparable mutual funds (that is, the difference in performance might be driven by the cost of active management instead of the social constraints).39

Activist Hedge Funds

Hedge funds are private pools of capital that engage in a variety of strategies—long–short, global macro, merger arbitrage, distressed debt, and so on—in an attempt to earn above-average returns in the capital markets. More than 1,000 hedge funds exist in the United States, managing between $2 trillion and $2.5 trillion in assets.40 Because they limit their investor pool to accredited investors (those with at least $1 million in investable assets or $200,000 in annual income), many hedge funds are exempt from the Investment Company Act of 1940. Following the Dodd–Frank Act, hedge funds with more than $150 million in assets under management are required to register with the SEC.

Hedge funds are notable among institutional investors in the fee structure that they charge clients. The typical hedge fund charges both a management fee, which is a fixed percentage of assets (typically 1 to 2 percent) and a performance-based fee (typically 20 percent) known as the carry, which is a percentage of the annual return or increase in the value of the investor’s portfolio. The fee structure charged by the industry necessitates superior financial performance. The magnitude of the fees is a considerable hurdle for the fund manager to overcome to simply match an index return.

Pressure to perform might shorten the investment time horizon of hedge funds. The importance of short-term performance presents a challenge because the prices of common stocks are subject to market forces that are outside the control of any one investor. Even a security that is deemed to be “undervalued” does not necessarily revert to “fair value” simply because it has been identified as such. As a result, some hedge funds decide to engage in activism to compel the price of the stock to converge upon its estimated fair value. Notable activist hedge funds include Icahn Capital Management, Pershing Square, Third Point, and Trian Partners. Brav, Jiang, Thomas, and Partnoy (2008) provided a detailed analysis of hedge fund activism. They found that activist hedge funds resemble value investors. Target companies have relatively high profitability in terms of return on assets and cash flow (relative to matched peers) but sell in the market at lower price-to-book ratios. They tend to have underperformed the market in the period preceding the hedge fund’s investment. They have more leverage and a lower dividend payout ratio, and are slightly more diversified in terms of operating businesses. Finally, they tend to be small in terms of market valuation, although their shares trade with more liquidity and are followed by a higher number of investment analysts.41 Of note, they do not tend to suffer from noticeable firm-specific operating deficiencies.42

On average, activist hedge funds accumulate an initial position representing 6.3 percent of the company’s shares (median average). In 16 percent of the cases, the funds also disclose derivative positions or securities with embedded options, such as convertible debt or convertible preferred stock. (This figure likely understates the true derivative exposure because disclosure of derivative investments is not required under SEC regulations.) Hedge funds are likely to coordinate their efforts with other funds to gain leverage. The study found that, in 22 percent of the cases, multiple hedge funds reported as one group in their regulatory filings with the SEC. (This figure likely understates coordination because funds employing a wolf pack strategy, and those that “pile on,” are not required to report a coordinated relationship.)43 Multiple hedge funds reporting as a single group take a 14 percent position, on average.

Institutional investors that acquire material ownership in a company are required to disclose the nature of their investment with the SEC.44 Approximately half of the funds in this study cited “undervaluation” as the reason for their investment. The rest stated that they intended to compel the company to make some sort of business or structural change—such as a change in strategy, capital structure, or governance system—or to pursue a sale of the company. These funds also used aggressive tactics to achieve their objectives, including regular and direct communication with the board or management (48 percent), shareholder-sponsored proposals and public criticism (32 percent), and full-fledged proxy contests to seize control of the board (13 percent).

The market reacts positively to news of initial investment by an activist hedge fund. On the announcement day, target stock prices generate abnormal returns of approximately 2.0 percent. During the next 20 days, the stock price continues to trend higher, with cumulative abnormal returns of 7.2 percent. However, the extent to which piling on by other hedge funds and institutional investors contributes to these short-term abnormal returns is unclear.

Klein and Zur (2009) studied the long-term success of activist hedge funds. Using a sample of 151 funds between 2003 and 2005, they found that hedge funds achieved a 60 percent success rate in meeting their stated objectives. Almost three-quarters (73 percent) of the funds that pursued board representation were successful. All hedge funds (100 percent) that wanted the target company to repurchase stock, replace the CEO, or initiate a cash dividend were successful. And half (50 percent) were able to compel the company to alter its strategy, terminate a pending acquisition, or agree to a proposed merger. These findings indicate that activist hedge funds are influential as a disciplining mechanism on the corporation.45

However, the evidence for their impact on long-term financial performance is mixed. Klein and Zur (2009) found that target companies exhibit abnormal returns around the announcement day of the investment but no subsequent improvement in operating performance. Instead, they reported a modest decline in return on assets and cash from operations. They also reported a decline in cash levels (consistent with increased stock buybacks and dividend payouts) and an increase in long-term debt. Bratton (2006) found some evidence that hedge funds are able to beat a benchmark portfolio in terms of shareholder value creation. However, these computations are quite sensitive to assumptions regarding risk adjustment and choice of the firms selected for the benchmark portfolio. Bebchuk, Brav, and Jiang (2015) studied 2,000 activist hedge fund interventions between 1994 and 2007 and found positive long-term improvements in operating performance, measured by return on assets.46 However, much of this improvement seems to be due to the natural tendency of poor operating performance to be followed by good performance (that is, “regression toward the mean”). deHaan, Larcker, and McClure (2015) found no statistical difference in operating performance among activist targets after controlling for regression tendencies. In fact, the only firms that earned excess stock price returns were those that were ultimately acquired. Activists appear to be good value investors that use the market for corporate control to fairly quickly generate value improvements for shareholders of target firms. Activists do not appear to improve strategy or operations for target companies that continue to be going concerns.47

Gantchev (2013) examined whether proxy contests waged by activist hedge funds result in net positive returns, taking into account the full cost of their efforts, including demand negotiations, board representation, and the contest itself. He calculated that a campaign for control costs on average $10.7 million and that estimated monitoring costs reduce activist returns by more than two-thirds. He found that the mean net activist return is close to zero, but the top quartile of activists earns higher returns on their activist holdings than on their non-activist investments.48

Shareholder Democracy and Corporate Engagement

In recent years, we have seen a considerable push by Congress, the SEC, and governance experts to increase the influence that shareholders have over corporate governance systems. These efforts are broadly labeled shareholder democracy because they are intended to give shareholders a greater say in corporate matters. Advocates of shareholder democracy believe that it will make board members more accountable to shareholder (and possibly stakeholder) objectives.

Elements of shareholder democracy include majority voting in uncontested director elections, proxy access, say-on-pay, and other voting-related issues. Closely related to shareholder democracy is the issue of direct engagement between shareholders and the board of directors. See Chapter 8, “Executive Compensation and Incentives,” for a discussion of say-on-pay. We discuss the other elements of shareholder democracy and corporate engagement next.

Majority Voting in Uncontested Director Elections

Companies have a choice of method for conducting director elections. Under plurality voting, directors who receive the most votes are elected, regardless of whether they receive a majority of votes. In an uncontested election, a director is elected as long as he or she receives at least one vote.

Many shareholder advocates believe that plurality voting reduces governance quality by insulating directors from shareholder pressure. They therefore recommend that companies adopt majority voting procedures in which a director must receive at least 50 percent of the votes (even in an uncontested election) to be elected. A director who receives less than a majority must tender a resignation to the board. The board can either accept the resignation or, upon unanimous consent, reject the resignation and provide an explanation for its conclusion. (Mandatory resignation and acceptance by the board if a director running unopposed fails to get a majority of votes was part of the original the Dodd–Frank Act but was ultimately dropped from the final version of the legislation.)

Majority voting in director elections has been widely adopted by large corporations, with 86 percent of companies in the S&P 500 Index adopting some variant of majority voting. However, it remains less common among small companies. Only 30 percent of the S&P SmallCap 600 Index have adopted majority voting.49

It is not clear whether majority voting improves governance quality. Dissenting votes are often issue driven and not personal to the director. For example, an institutional investor might withhold votes to reelect members of the compensation committee if it believes the company’s compensation practices are excessive. This might inadvertently work to remove a director who brings important strategic, operational, or risk-management qualifications to the board. As we saw in Chapter 4, “Board of Directors: Selection, Compensation, and Removal,” the vast majority of directors receive greater than 50 percent support from shareholders; in 2013, only 44 directors (less than 0.1 percent) failed to receive majority approval.50

Proxy Access

Historically, the board of directors has had sole authority to nominate candidates whose names appear on the company proxy. In 2010, the Dodd–Frank Act instructed the SEC to amend Rule 14a-8 to allow shareholder-designated nominees to be included on the proxy, alongside the nominations set forth by the company. This rule was vacated by a U.S. Court of Appeals in 2011.51 However, shareholder groups subsequently have sponsored resolutions that would grant qualifying investor groups the right to nominate directors on the company’s proxy (“proxy access”).

Under a typical proxy access proposal, shareholders or coalitions of shareholders who hold 3 percent or more of the company’s shares and who have held their positions continuously for at least three years would be eligible to nominate up to 25 percent of the board. Some proxy access proposals have lower thresholds.

According to data from Sullivan & Cromwell, 10 proposals for proxy access were voted on in 2014. Of these, 3 passed and 7 failed; average support was 34 percent.52 The following year, a much greater effort to promote proxy access was under way. The comptroller of the City of New York, overseeing pension funds with a combined $160 billion in assets, submitted proxy access proposals at 75 public companies, including ExxonMobil, Staples, and Abercrombie & Fitch. The outcome of this is not yet known, nor is the impact that proxy access will have on director elections or governance quality known. Few, if any, traditional institutional investors that own block positions are likely to run a dissident slate of directors. It is more likely that activist investors will do so.

Recent research suggests that shareholder democracy initiatives reduce shareholder value. A study by Larcker, Ormazabal, and Taylor (2011) found that the market reacts negatively to potential say-on-pay regulation and proxy access and that the reaction is more negative among companies that are most likely to be affected. They concluded that “the market perceives that the regulation of executive compensation will ultimately result in less efficient contracts and potentially decrease the supply of high-quality executives to public firms.” They also concluded that “blockholders . . . may use the new privileges afforded them by proxy access regulation to manipulate the governance process to make themselves better off at the expense of other shareholders.”53

Proxy Voting

The SEC has been examining the proxy voting process to determine whether rules should be implemented to increase voting participation, efficiency, and transparency. At issue is whether third-party agents have inappropriate influence on the voting process to the detriment of shareholder value. One such party is broker-dealers who act as a fiduciary for beneficial shareholders. Another is vote tabulators (such as Broadridge), intermediaries, and proxy service providers who have access to vote data and might influence votes. A third is institutional investors who lend their securities and might not recall their shares in time to vote on certain matters. The SEC is examining whether the voting process should be changed or disclosure increased to improve decision making. The SEC is also examining ways to increase voting participation by individual shareholders.54 According to data from Broadridge and PricewaterhouseCoopers, retail investors vote only 30 percent of their shares, compared with 95 percent of shares held by institutional investors.55

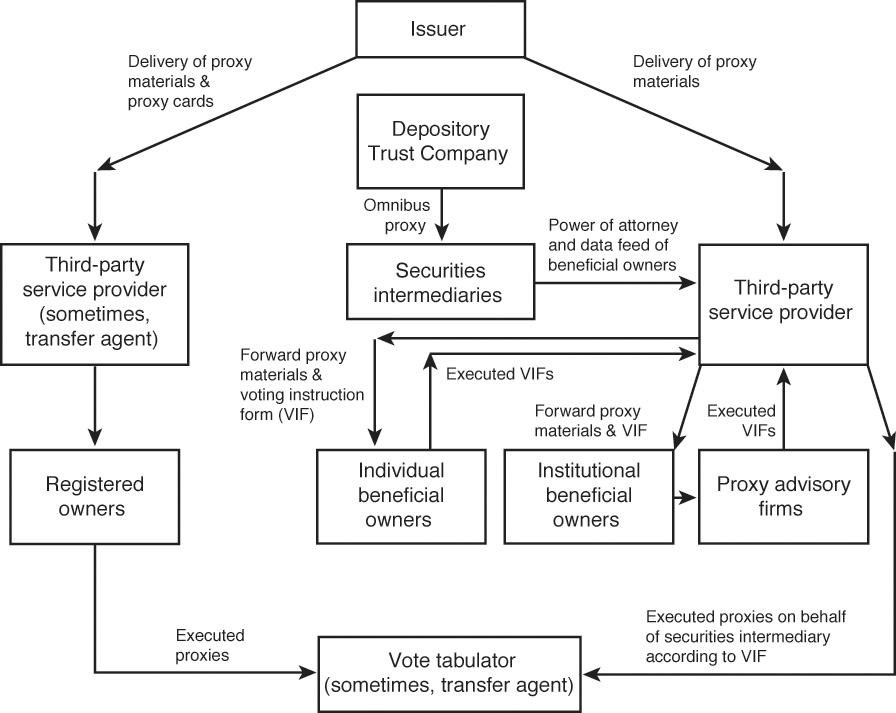

As Figure 12.2 illustrates, the proxy voting process is extremely complicated and, in some cases, not well understood.

Source: Securities and Exchange Commission: Concept Release on the U.S. Proxy System. July 14, 2010.

Figure 12.2 Proxy voting procedures: a complex process.

A 2015 survey by RR Donnelley, Equilar, and the Rock Center for Corporate Governance at Stanford University underscores the frustration that many investors feel about the proxy voting process. The survey found that 55 percent of institutional investors believe that the typical proxy statement is too long. Forty-eight percent believe it is difficult to read and understand. Investors claim to read only 32 percent of a typical proxy, on average. They report that the ideal length of a proxy is 25 pages, compared with an actual average of 80 pages among companies in the Russell 3000.

The survey also found that while investors believe the proxy voting process to be a valuable exercise, portfolio managers are only moderately involved in voting decisions. Among large institutional investors with assets under management greater than $100 billion, portfolio managers are involved in only 10 percent of decisions. Only 59 percent of institutional investors use information in the proxy for investment decisions.56 These data reinforce problems with the current voting system. They also suggest that investors might make more informed decisions if the quality of disclosure were improved.

Corporate Engagement

Finally, institutional investors influence corporate matters not only through the proxy voting process but also through direct engagement with corporations. These efforts are not always visible to the individual shareholder but can have a tangible effect on corporate policy. For example, in 2014 Vanguard sent a letter to approximately 350 companies in which the fund invested to encourage them to declassify their boards, adopt majority voting for directors, and provide shareholders the right to call a special meeting. Vanguard dubbed the effort “quiet diplomacy” and explained that it sent letters “to share our views about corporate governance practices that create the best opportunity for both long-term business success and superior investment returns.”57 That same year, the CEO of BlackRock wrote to companies in the S&P 500 Index to express concern that corporations were being too “short-term” in perspective by favoring dividends and share repurchases over capital expenditures and that these decisions might “jeopardize a company’s ability to generate sustainable long-term returns.”58

Still, direct dialogue between institutional investors and a company’s board of directors is relatively infrequent in the United States. According to the survey by RR Donnelley referenced in the previous section, institutional investors engage with only 9 percent on average of the companies they invest in.59 A PricewaterhouseCoopers survey found that 54 percent of directors believe that it is not appropriate for the board to engage in direct discussion with investors about earnings results, 44 percent believe it is not appropriate to discuss strategy or management performance, and 38 percent that it is in not appropriate to discuss financial oversight or risk management. When asked to elaborate, 94 percent claim that direct communication with shareholders creates too great a risk of mixed messages and 89 percent believe it is not appropriate because investors who seek direct communication with the board often have a special agenda.60

In Europe, direct engagement between shareholders and corporations is more common. For example, the United Kingdom Corporate Governance Code states that “the board as a whole has a responsibility for ensuring that a satisfactory dialogue with shareholders takes place.” It also recommends that “the board should keep in touch with shareholder opinion in whatever ways are most practical and efficient.”61

Proxy Advisory Firms

Many institutional investors rely on a proxy advisory firm to assist them in voting the company proxy and fulfilling the fiduciary responsibility to vote the shares on behalf of clients. The largest proxy advisory firms are Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS) and Glass Lewis & Co., whose clients manage $25 trillion and $15 trillion in assets, respectively.

For a variety of reasons, proxy advisory firms are highly influential in the voting process. First, institutional investors have little economic incentive to incur the research costs necessary to develop proprietary voting policies. Proxy research suffers from the same free rider problem common to many voting situations and discussed at the beginning of this chapter. The average institutional investor has little incentive to bear the cost of researching proxy issues relating to individual firms across a diversified portfolio when it only stands to receive a small fraction of the benefit. Proxy advisory firms can satisfy this need by researching the same set of issues across multiple firms and selling their research to multiple investors. Second, in 2003, the SEC began to require that registered institutional investors develop and disclose their proxy voting policies, and disclose their votes on all shareholder ballot items. The rule was intended to create greater transparency into the voting process and to ensure that institutional investors act without conflict of interest. At the same time, the SEC clarified that the use of voting policies developed by an independent, third-party agency (such as a proxy advisor) would be viewed as being non-conflicted.62 As a result, the proxy voting guidelines of third-party firms have become a cost-effective means of satisfying fiduciary and regulatory voting obligations for institutional investors.

However, several potential drawbacks can occur from relying on the advice of a proxy advisory firm. First, proxy advisory firms take a somewhat inflexible approach toward certain governance matters and do not always properly consider the unique company situation (see the following sidebar). As a result, the recommendations of these firms might reflect a one-size-fits-all approach to governance and the propagation of “best practices” that the research literature has not supported. Second, these firms might not have sufficient staff or adequate expertise to evaluate the items subject to shareholder approval, particularly complicated issues such as the approval of equity-based compensation plans or proposed acquisitions.63 Third, some of these firms have potential conflicts of interest because they provide consulting services to the companies whose proxies they evaluate (see Chapter 13, “Corporate Governance Ratings,” for a discussion). Finally, the complete reliance on proxy advisory firms might constitute an abdication of fiduciary responsibility. Institutional investors are ultimately responsible for ensuring that their votes are in the best interest of their shareholders.64

Considerable evidence documents the influence that proxy advisory firms have over voting matters. Several institutional investors vote in near-perfect lockstep with the recommendations of proxy advisory firms across all proxy resolutions (see Table 12.4).67

Includes the 10 institutional investors with the largest number of votes based on Form N-PX 2013 filings.

Source: Data from ISS Voting Analytics (2013). Calculation by the authors.

Table 12.4 Institutional Investor Voting Record (Voting with ISS)

Bethel and Gillan (2002) found that an unfavorable recommendation from ISS can reduce shareholder support on proxy items by 13.6 to 20.6 percent, depending on the matter of the proposal.68 Cai, Garner, and Walkling (2009) found that directors who receive a negative recommendation from ISS receive 19 percent fewer votes.69 Morgan, Paulson, and Wolf (2006) found that an unfavorable recommendation from ISS reduces shareholder support by 20 percent on compensation-related issues.70 Ertimur, Ferri, and Oesch (2013) had similar findings.71

In response to this and other empirical evidence, an SEC commissioner has expressed concern that “it is important to ensure that advisers to institutional investors . . . are not over-relying on analyses by proxy advisory firms” and that institutional investors should not “be able to outsource their fiduciary duties.”72

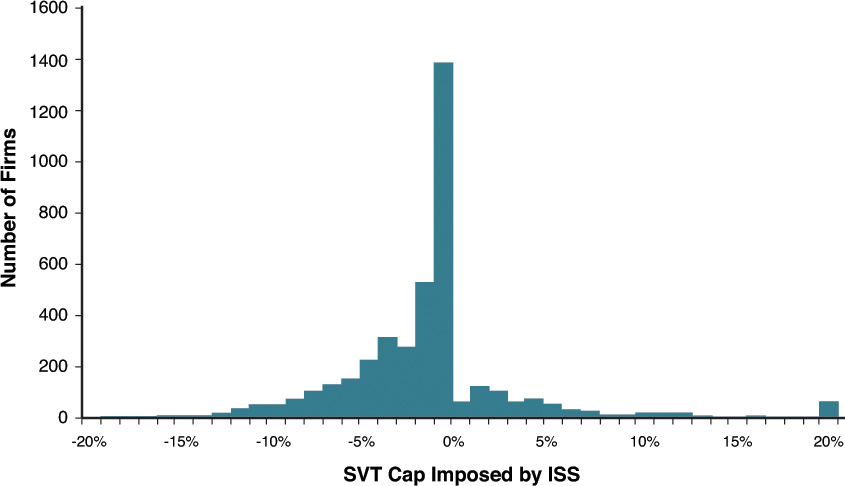

A growing body of evidence also suggests that proxy advisory firms have influence over corporate decisions on compensation design. A 2012 survey found that more than 70 percent of companies report that their executive compensation programs are influenced by the policies and guidelines of proxy advisory firms.73 Furthermore, an analysis by Gow, Larcker, McCall, and Tayan (2013) indicated that companies adjust the size of their equity compensation programs to meet ISS maximum thresholds. Among a sample of 4,230 company observations between 2004 and 2010, 34 percent of proposed equity plans would put the company within 1 percent of the ISS cap. By a greater than 20-to-1 margin, companies request equity that would put them 1 percent below the cap rather than 1 percent above the cap. These results are highly improbable based on chance alone and suggest that many companies acquire information on ISS thresholds and design their equity plans to fall just below this number (see Figure 12.3).74 The proxy statements of companies such as Chesapeake Energy and United Online explicitly reference ISS thresholds in justifying the size of their equity compensation programs.75

Source: ISS Proxy Recommendation Reports (2004–2010). Calculations by Gow, Larcker, McCall, and Tayan (2013).

Figure 12.3 Relation between company equity plan requests and ISS caps.

Finally, research studies suggest that the recommendations of proxy advisory firms are not value increasing and might be value decreasing for shareholders. Larcker, McCall, and Ormazabal (2013) found that many corporations constrain stock option repricing programs to meet the guidelines of proxy advisory firms and that those that do exhibit statistically lower market reactions to the repricing, lower operating performance, and higher employee turnover.76 In a separate study, Larcker, McCall, and Ormazabal (2015) found that a substantial number of firms change their compensation programs to garner a favorable say-on-pay recommendation from proxy advisory firms, and that these changes are also value decreasing to shareholders.77 These results call into question the quality of proxy advisory recommendations (see the following sidebar).

Endnotes

1. The investor relations consulting industry attempts to understand the various roles played by different types of institutional investors and to move the shareholder base to investor types that are perceived as more desirable by management. See David F. Larcker and Brian Tayan, “Sharks in the Water: Battling an Activist Investor for Corporate Control,” Stanford GSB Case No. CG–20 (February 2, 2010).

2. The role of passive index funds in the governance debate is somewhat problematic. If the fund holds roughly the same stocks as the index, it is not clear whether passive funds will be an active change agent for better corporate governance. Still, many people believe that given their sizable ownership position, index funds should use their position to advocate responsible governance reforms when appropriate.

3. Regulation FD (fair disclosure) has greatly limited the extent to which company management meets with individual investor groups. The SEC adopted Regulation FD in October 2000 to limit the selective disclosure of material nonpublic information to investors who might gain an advantage by trading on such information. The rule provides that when an issuer, or person acting on the issuer’s behalf, unintentionally discloses such information, it has an obligation to promptly disclose the same information to the public. Since the adoption of Regulation FD, companies have been less likely to meet with individual investor groups.

4. BlackRock, “2013 Corporate Governance & Responsible Investment Report: Taking the Long View” (2014). Accessed April 4, 2015. See http://www.blackrock.com/corporate/en-us/about-us/responsible-investment/responsible-investment-reports.

5. National Investor Relations Institute and the Rock Center for Corporate Governance at Stanford University, “2014 Study on How Investment Horizon and Expectations of Shareholder Base Impact Corporate Decision-Making” (2014). Accessed May 6, 2015. See http://www.gsb.stanford.edu/faculty-research/centers-initiatives/cgri/research/surveys.

6. Ibid.

7. Brian Bushee, “Identifying and Attracting the ‘Right’ Investors: Evidence on the Behavior of Institutional Investors,” Journal of Applied Corporate Finance 16 (2004): 28–35.

8. Thomson Reuters on WRDS, 13F Institutional Holdings (CDA/Spectrum).

9. Michael J. Barclay and Clifford G. Holderness, “Private Benefits from Control of Public Corporations,” Journal of Financial Economics 25 (1989): 371–395.

10. Hamid Mehran, “Executive Compensation Structure, Ownership, and Firm Performance,” Journal of Financial Economics 38 (1995): 163–184.

11. Stuart Gillan and Laura Starks, “The Evolution of Shareholder Activism in the United States,” Journal of Applied Corporate Finance 19 (2007): 55–73.

12. Barclay and Holderness (1989).

13. John L. McConnell and Henri Servaes, “Additional Evidence on Equity Ownership and Corporate Value,” Journal of Financial Economics 27 (1990): 595–612.

14. Mehran (1995).

15. Clifford G. Holderness, “A Survey of Blockholders and Corporate Control,” Economic Policy Review—Federal Reserve Bank of New York 9 (2003): 51–63.

16. John E. Core, Robert W. Holthausen, and David F. Larcker, “Corporate Governance, Chief Executive Officer Compensation, and Firm Performance,” Journal of Financial Economics 51 (1999): 371–406.

17. Marianne Bertrand and Sendhil Mullainathan, “Do CEOs Set Their Own Pay? The Ones without Principals Do,” NBER working paper Series w7604, Social Science Research Network (2000). Accessed May 6, 2015. See http://ssrn.com/abstract=228095.

18. Reena Aggarwal, Isil Erel, Miguel Ferreira, and Pedro Matos, “Does Governance Travel around the World? Evidence from Institutional Investors,” Journal of Financial Economics 100 (2011): 154–181.

19. Wayne H. Mikkelson and Megan Partch, “Managers’ Voting Rights and Corporate Control,” Journal of Financial Economics 25 (1989): 263–290.

20. Sovereign Wealth Fund Institute, “Sovereign Wealth Fund Rankings,” Data as of April 6, 2015. Accessed May 6, 2015. See http://www.swfinstitute.org/fund-rankings/.

21. Norway Ministry of Finance, “The Management of the Government Pension Fund in 2013” (April 4, 2014.) Accessed April 6, 2015. See http://www.nbim.no/globalassets/documents/governance/stortingsmeldinger/report-to-the-storting-no-19-on-the-management-of-the-government-pension-fund-global.pdf?ID=5229.

22. Mark Scott, “Qatar Wealth Fund Backs Glencore’s Bid for Xstrata,” New York Times (November 16, 2012).

23. Securities Exchange Commission, “Disclosure of Proxy Voting Policies and Proxy Voting Records by Registered Management Investment Companies,” Release No. 25922 (January 31, 2003). Accessed October 8, 2013. See www.sec.gov/rules/final/33-8188.htm.

24. ISS Voting Analytics data for fiscal years from June 2013 to May 2014.

25. Securities Lawyer’s Deskbook, “Rule 14a8: Proposals of Security Holders.” Accessed May 5, 2015. See https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/17/240.14a-8.

26. Proxy Monitor, “A Report on Corporate Governance and Shareholder Activism,” Manhattan Institute (2014). Accessed April 7, 2015 See http://www.proxymonitor.org/Forms/pmr_09.aspx.

27. ISS, “2013 Proxy Season Review: United States” (August 22, 2013). Accessed April 7, 2015. See http://www.issgovernance.com/library/united-states-2013-proxy-season-review/.

28. See Chapter 11, endnote 3. Warren S. De Wied, “Proxy Contests,” Practical Law: The Journal (November 2010). Accessed November 13, 2010. See http://us.practicallaw.com/.

29. ISS, “2013 Proxy Season Review: United States” (August 22, 2013).

30. Ashwini K. Agrawal, “Corporate Governance Objectives of Labor Union Shareholders: Evidence from Proxy Voting,” Review of Financial Studies 25 (2012): 187–226.

31. Brad Barber, “Monitoring the Monitor: Evaluating CalPERS’ Activism,” Journal of Investing 16 (2007): 66–80.

32. Marc Lifsher, “CalPERS Changes Tactics on Poor Performers,” Los Angeles Times blogs online (November 15, 2010). Accessed November 25, 2010. See http://latimesblogs.latimes.com/money_co/2010/11/calpers-company-focus-list.html.

33. Social Investment Forum, “Socially Responsible Mutual Funds Chart: Financial Performance. Information Current as of September 30, 2010.” Accessed November 15, 2010. See www.socialinvest.org/resources/mfpc/.

34. Walden Asset Management, “Advocating for Social Change” (2010). Accessed November 15, 2010. See www.waldenassetmgmt.com/social.html.

35. Proxy Monitor (2014).

36. Nike Corp., Form DEF 14A, filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission August 12, 1996.

37. Voting results from Nike Corp., Form 10-Q for the quarter ending August 31, 1996, filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission October 15, 1996. Corporate reforms from Debora L. Spar and Lane T. La Mure, “The Power of Activism: Assessing the Impact of NGOs on Global Business,” California Management Review 45 (2003): 78–101.

38. Christopher Charles Geczy, Robert F. Stambaugh, and David Levin, “Investing in Socially Responsible Mutual Funds,” Social Science Research Network (October 2005). Accessed June 2, 2014. See http://ssrn.com/abstract=416380.

39. Luc Renneboog, Jenke Ter Horst, and Chendi Zhang, “The Price of Ethics and Stakeholder Governance: The Performance of Socially Responsible Mutual Funds,” Journal of Corporate Finance 14 (2008): 302–322.

40. Wikipedia, “Hedge Funds.” Accessed May 5, 2015. See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hedge_fund.

41. Small, liquid targets enable the activist hedge fund to accumulate a sizable position with relative speed and without running up the price of the stock. Presumably, it also enables the firm to eventually exit the position quickly and without depressing the stock.

42. Alon Brav, Wei Jiang, Frank Partnoy, and Randall Thomas, “Hedge Fund Activism, Corporate Governance, and Firm Performance,” Journal of Finance 63 (2008): 1729–1775.

43. In a wolf pack strategy, multiple hedge funds work together to force change on a target company. Piling on refers to unaffiliated hedge funds accumulating a position in a stock when they learn that an activist has taken a significant position. Hedge funds that pile on to a target are not activists themselves. However, these hedge funds are likely to support the recommendations of the activist.

44. SEC rules require that an investor who holds more than 5 percent of a company’s stock disclose its position. Disclosure on Form 13G indicates that the investor intends to hold the position as a passive investment (that is, the investor does not intend to become active with management or to seek a change in control). Disclosure on Form 13D indicates a possible active holding.

45. April Klein and Emanuel Zur, “Entrepreneurial Shareholder Activism: Hedge Funds and Other Private Investors,” Journal of Finance 64 (2009): 187–229.

46. Lucian A. Bebchuk, Alon Brav, and Wei Jiang, “The Long-Term Effects of Hedge Fund Activism,” Columbia Law Review (forthcoming, June 2015).

47. Ed deHaan, David F. Larcker, and Charles McClure, “Activists as Value Investors,” unpublished working paper (2015).

48. Nickolay Gantchev, “The Costs of Shareholder Activism: Evidence from a Sequential Decision Model,” Journal of Financial Economics 107 (2013): 610–631.

49. SharkRepellent, “Takeover Defenses Trend Analysis, 2014,” SharkRepellent, FactSet Research Systems, Inc. (2015). Accessed March 26, 2015. See www.sharkrepellent.net.

50. ISS, “2013 Proxy Season Review: United States” (August 22, 2013).

51. The Court’s decision was in response to a September 2010 lawsuit filed by the Chamber of Commerce and Business Roundtable against the SEC that claimed “the rule is arbitrary and capricious [and] violates the Administrative Procedure Act, and . . . the SEC failed to properly assess the rule’s effects on ‘efficiency, competition, and capital formation’ as required by law.” See U.S. Chamber of Commerce press release, “U.S. Chamber Joins Business Roundtable in Lawsuit Challenging Securities and Exchange Commission” (September 29, 2010). The Business Roundtable and U.S. Chamber of Commerce Petition for Review filed in the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit (September 29, 2010). Accessed May 5, 2015. See www.uschamber.com/sites/default/files/files/1009uscc_sec.pdf.

52. Sullivan & Cromwell, “2014 Proxy Season Review” (June 25, 2014). Accessed April 8, 2015. See http://www.sullcrom.com/siteFiles/Publications/SC_Publication_2014_Proxy_Season_Review.pdf.

53. David F. Larcker, Gaizka Ormazabal, and Daniel J. Taylor, “The Market Reaction to Corporate Governance Regulation,” Journal of Financial Economics 101 (2011): 431–448.

54. See Securities and Exchange Commission, “Securities and Exchange Commission Proxy Roundtable” (February 19, 2015). Accessed May 5, 2015. See http://www.sec.gov/news/statement/ensuring-shareholders-have-meaningful-effective-vote.html. Also see “Securities and Exchange Commission: Concept Release on the U.S. Proxy System” (July 14, 2010). Accessed May 6, 2015. http://www.sec.gov/rules/concept/2010/34-62495.pdf.

55. Broadridge and PricewaterhouseCoopers, “Directors and Investors: Are They on the Same Page? Insights from the 2014 Proxy Season and Recent Governance Surveys” (October 2014). Accessed May 6, 2015. See http://www.pwc.com/en_US/us/corporate-governance/publications/assets/proxypulse-3rd-edition-october-2014-pwc.pdf.

56. RR Donnelly, Equilar, and the Rock Center for Corporate Governance at Stanford University, “2015 Investor Survey: Deconstructing Proxies—What Matters to Investors” (2015). Accessed May 6, 2015. See http://www.gsb.stanford.edu/faculty-research/publications/2015-investor-survey-deconstructing-proxy-statements-what-matters.

57. According to Vanguard, “We sent formal written communications to the chairpersons and CEOs of nearly 1,000 of our largest holdings. We customized our communications based on specific changes we wanted to see. Nearly 350 of these communications committed requests for companies to remove problematic governance structures (such as classes of stock that disproportionally give one class more votes, or staggered director elections) or to revisit compensation policies. To date, nearly one-half of the companies followed up and more than 80 have also made, or committed to try to make, at least one of the changes. We are still receiving responses as companies address our requests at board and shareholder meetings.” See Vanguard, “Our Proxy Voting and Engagement Efforts: An Update.” Accessed April 13, 2015. See https://about.vanguard.com/vanguard-proxy-voting/update-on-voting/.

58. Text of letter sent by Larry Fink, BlackRock’s Chairman and CEO, encouraging a focus on long-term growth strategies, Wall Street Journal online. Accessed April 4, 2015. See http://online.wsj.com/public/resources/documents/LDF_letter_to_corporates_2014_public.pdf.

59. RR Donnelly, Equilar, and the Rock Center for Corporate Governance at Stanford University (2015).

60. PricewaterhouseCoopers LLC, “PWC’s 2014 Annual Corporate Directors Survey: Trends Shaping Governance and the Board of the Future: Executive Compensation and Director Communications” (2014). Accessed April 7, 2015. See http://www.pwc.com/us/en/corporate-governance/annual-corporate-directors-survey/assets/annual-corporate-directors-survey-full-report-pwc.pdf.

61. Financial Reporting Council, “The UK Corporate Governance Code” (September 2012). Accessed April 7, 2015. See https://www.frc.org.uk/Our-Work/Publications/Corporate-Governance/UK-Corporate-Governance-Code-September-2012.aspx.

62. According to the SEC, “An independent [investment] adviser that votes client proxies in accordance with a pre-determined policy based on the recommendations of an independent third party will not necessarily breach its fiduciary duty of loyalty to its clients even though the recommendations may be consistent with the adviser’s own interest. In essence, the recommendations of a third party that is in fact independent of an investment adviser may cleanse the vote of the adviser’s conflict.” U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, “Egan-Jones Proxy Services: No-Action letter dated May 27, 2004” (2004). Accessed October 8, 2013. See www.sec.gov/divisions/investment/noaction/egan052704.htm.

63. Institutional Shareholder Services has approximately 800 employees. Not all 800 employees are “governance analysts.” Some employees are involved in tedious data collection and other administrative tasks. See ISS, “The Leader in Corporate Governance.” Accessed March 9, 2013. See http://www.issgovernance.com/about/about-iss/.

64. The Department of Labor has proposed broadening the definition of a fiduciary to any entity that provides investment advice to employee benefit plans. If enacted, this would include proxy advisory firms. Marc Hogan, “DOL Proposal Could Threaten ISS,” Agenda (November 8, 2010). Also see Melissa J. Anderson, “SEC to Examine Proxy Advisors for Conflicts of Interest,” Agenda (January 16, 2015). Accessed March 9, 2015. See http://agendaweek.com/pc/1046003/107713.

65. Berkshire Hathaway, “2003 Annual Report.” Accessed August 27, 2007. See www.berkshirehathaway.com/2003ar/2003ar.pdf.

66. Philip Klein, “Reformers’ Proxy Votes Polarize Governance Debate,” Reuters News (April 18, 2004). Andrew Countryman, “Coke Can Go Better with Icon Buffett,” Courier-Mail (April 12, 2004): 18. The Coca-Cola Company, Form DEF 14A, filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission April 9, 2004. Margery Beck, “Buffett Calls Effort to Make Him Leave Coca-Cola Board ‘Absolutely Silly,’” Associated Press Newswires (May 2, 2004).

67. ISS Voting Analytics data for fiscal years from June 2013 to May 2014.

68. Jennifer E. Bethel and Stuart L. Gillan, “The Impact of Institutional and Regulatory Environment on Shareholder Voting,” Financial Management (2002): 29–54.

69. Jie Cai, Jacqueline L. Garner, and Ralph A. Walking, “Electing Directors,” Journal of Finance 64 (2009): 2389–2421.

70. Angela Morgan, Annette Paulson, and Jack Wolf, “The Evolution of Shareholder Voting for Executive Compensation Schemes,” Journal of Corporate Finance 12 (2006): 715–737.

71. Yonca Ertimur, Fabrizio Ferri, and David Oesch, “Shareholder Votes and Proxy Advisors: Evidence from Say on Pay,” Journal of Accounting Research 51 (2013): 951–996.

72. Daniel M. Gallagher, “Gallagher on the Roles of State and Federal Law in Corporate Governance,” Columbia Law School’s Blog on Corporations and the Capital Markets (June 18, 2013). Accessed April 9, 2015. See http://clsbluesky.law.columbia.edu/2013/06/18/gallagher-on-the-roles-of-state-and-federal-law-in-corporate-governance/.

73. The Conference Board, NASDAQ, and the Rock Center for Corporate Governance at Stanford University, “The Influence of Proxy Advisory Firm Voting Recommendations on Say-on-Pay Votes and Executive Compensation Decisions” (2012). Accessed May 6, 2015. See http://www.gsb.stanford.edu/faculty-research/publications/2012-proxy-advisory-survey.

74. David F. Larcker, Ian D. Gow, Allan McCall, and Brian Tayan, “Sneak Preview: How ISS Dictates Equity Plan Design,” Stanford Closer Look Series (October 23, 2013). Accessed May 6, 2015. See http://www.gsb.stanford.edu/faculty-research/centers-initiatives/cgri/research/closer-look.

75. See Chesapeake Energy Corp., Form DEF 14A, filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission April 30, 2014; and United Online Inc., Form DEF 14A, filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission April 30, 2013.

76. David F. Larcker, Allan L. McCall, and Gaizka Ormazabal, “Proxy Advisory Firms and Stock Option Repricing,” Journal of Accounting and Economics 56 (2013): 149–169.

77. David F. Larcker, Allan L. McCall, and Gaizka Ormazabal, “Outsourcing Shareholder Voting to Proxy Advisory Firms,” Journal of Law and Economics (forthcoming 2015).

78. Glass Lewis & Co., “Discussion Paper—An Overview of the Proxy Advisory Industry. Considerations on Possible Policy Options” (June 25, 2012). Accessed March 9, 2015. See http://www.glasslewis.com/assets/uploads/2012/12/062512_glass_lewis_comment_esma_discussion_paper_vf.pdf.

79. ISS, “Policy Formulation and Application” (2015). Accessed March 9, 2015. See http://www.issgovernance.com/policy-gateway/policy-formulation-application/.

80. David F. Larcker, Allan McCall, and Brian Tayan, “And Then a Miracle Happens,” Stanford Closer Look Series (February 25, 2013). Accessed May 6, 2015. See http://www.gsb.stanford.edu/faculty-research/centers-initiatives/cgri/research/closer-look.