5. Board of Directors: Structure and Consequences

In this chapter, we examine the structural attributes of the board of directors and provide an assessment of whether these choices contribute to board effectiveness and shareholder value. Despite what you might read in the popular press or professional literature, this is not a simple exercise.

Our objective is to take you through the evidence. We critically examine the importance of several salient features of a board of directors: separation of roles between the chairman and the CEO, the appointment of a lead director, board size, board committee structure, boards with directors that serve on other boards (that is, “busy” directors), female directors and diverse boards, and others. We also examine what impact, if any, these attributes have on the board’s ability to perform its advising and monitoring functions. If these attributes are important, we should see that they are associated with improved outcomes (such as superior operating performance or increased stock returns) or other observable metrics (such as higher takeover premiums, fewer accounting restatements, less shareholder litigation, and more rational executive compensation). If no improvements are observed, it is difficult to claim that these attributes are significant.

Two caveats are important. First, we do not provide a complete review of the literature on each topic in this chapter. The relevant body of work is too expansive to be summarized in one place. Still, we aim to provide a fair reflection of the general research results. Second, as mentioned in Chapter 1, “Introduction to Corporate Governance,” the results discussed in this chapter are “on average” results across a large sample of companies. They do not tell us what will happen for an individual company. A company might find that a certain board structure is perfectly suitable, given its specific situation, even though the evidence from academic and professional literature suggests that it leads to worse outcomes on average. Where applicable, we cite examples that attempt to draw out these contradictions and, in doing so, enable the reader to draw conclusions about the relative importance of individual attributes. Finally, it is difficult to infer that any change in the board of directors will “cause” a change in organizational performance. In reading this chapter, keep in mind the famous dictum that “correlation does not imply causation.”

Board Structure

The structure of a board of directors is generally described in terms of its prominent structural attributes: its size, professional and demographic information about the directors serving on it, their independence from management, number of committees, and director compensation.

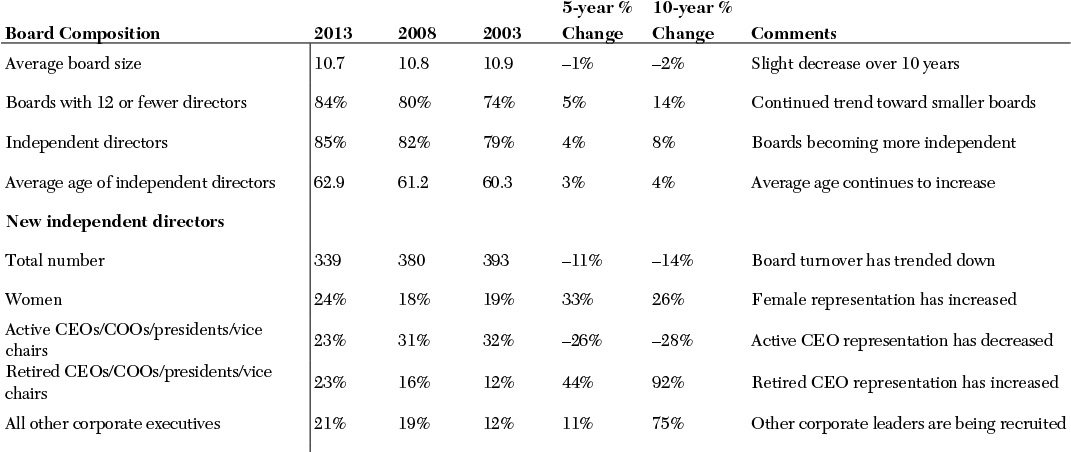

According to Spencer Stuart, the board of an average large U.S. corporation has approximately 11 directors. (Boards usually have an odd number of directors to reduce the likelihood of a tie vote.) The average age of directors is nearly 63 years. More than 85 percent of directors meet the independence standards required by U.S. listing exchanges. Fifty-five percent have a chairman who is also CEO, and only 25 percent have a chairman who is fully independent. Boards meet (in person and by telephone) eight times per year, on average. Audit committee members meet nine times, and compensation committee members six times. The Sarbanes–Oxley Act of 2002 mandates that all members of these committees be independent directors and that at least one member of the audit committee have expertise in finance and accounting. Approximately three-quarters of boards have a mandatory retirement age, which is usually 72 years or older (see Table 5.1).1 Term limits are relatively rare in the U.S. but are observed outside North America.

Source: Spencer Stuart, “Spencer Stuart U.S. Board Index® 2013” (2013). Copyright © 2013 Spencer Stuart. Reprinted and used by permission. Comments edited by the authors.

Table 5.1 Structure of the Board of Directors of U.S. Corporations

Are these the right levels? Would outcomes improve if companies were compelled, through either regulation or shareholder activism, to change the composition of their boards? We consider several attributes:

• Independence of the chairman

• Lead independent director

• Outside (nonexecutive) directors

• Independence standards

• Independent committees of the board

• Representation on the board by selected constituents (bankers, financial experts, politically connected individuals, and employees)

• Companies whose directors sit on multiple boards (busy boards)

• Companies whose senior executives sit reciprocally on each other’s boards (interlocked boards)

• Overlapping committee assignments

• Board size

• Diverse boards

• Boards with female directors

Chairman of the Board

The chairman presides over board meetings. He or she is responsible for scheduling meetings, planning agendas, and distributing materials in advance. In this way, the chairman shapes the timing and manner in which the board addresses governance matters and sets the meeting agenda. The chairman also plays a critical role in communicating corporate priorities, both internally and externally, and in managing stakeholder concerns. The chairman is expected to participate in or lead the discussion of several high-level items, including long-term strategic planning, enterprise risk management, management performance evaluation, management and director compensation, succession planning, director recruitment, and merger-related activity.

Professional studies suggest that certain personal characteristics might be correlated with an individual being more effective in this role. These include good communication and listening skills, a clear sense of direction, business acumen, an ability to bring people together, an ability to get to key issues quickly, and an ability to gain shareholder confidence.2 Although these have not been thoroughly tested, anecdotes of successful public company chairmen tend to support them. For example, John Pepper, former nonexecutive chairman of the Walt Disney Company, was known for being an effective chairman who restored relations with shareholders and stakeholders following the tumultuous ending to Michael Eisner’s long run as CEO of that company. As one friend described Pepper, “He is very balanced and mature and can deal with all kinds of people. He can take a position in the middle of a dispute, but people will feel like he’s listened and considered a position even if he comes out on the other side.”3

Many governance experts assert that it is important that the position of chairman be separated from the position of CEO. This approach is widely adopted in the United Kingdom and other countries. It was also required of companies in the United States that received extraordinary assistance under the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) in 2008, and it was proposed as a requirement of all publicly traded companies under Senator Charles Schumer’s Shareholder Bill of Rights.4 Prominent shareholder groups, pension funds, and proxy advisory firms generally support shareholder proposals to create an independent chairman. According to proxy advisory firm Glass, Lewis & Co., “We ultimately believe vesting a single person with both executive and board leadership concentrates too much oversight in a single person and inhibits the independent oversight intended to be provided by the board on behalf of shareholders”5 According to Spencer Stuart, 25 percent of boards in the United States have an independent chairman.6

Having an independent chairman includes several potential benefits:

• It leads to clearer separation of responsibility between the board and management.

• It eliminates conflicts in the areas of CEO performance evaluation, executive compensation, long-term succession planning, and the recruitment of independent directors.

• It gives clear authority to one director to speak to shareholders, management, and the public on behalf of the board.

• It gives the CEO time to focus completely on the strategy, operations, and culture of the company.

Advocates of an independent chairman believe that having one is particularly important in these situations:

• The company has a new CEO, particularly an insider who has been promoted and therefore has no previous experience as CEO.

• Company performance has declined and significant changes to the company’s strategy, operations, or culture are needed that require management’s complete attention while the board considers whether a change in leadership or sale of the company is necessary (see the accompanying sidebar).

• The company has received an unsolicited takeover bid, which management might not be able to evaluate independently without considerations for their own job status.

However, having an independent chairman can also involve several potential disadvantages:

• It can be an artificial separation, particularly when the company already has an effective chairman/CEO in place.

• It can make recruiting a new CEO difficult when that individual currently holds both titles or expects to be offered both titles.

• It can create duplication of leadership and internal confusion.

• It can lead to inefficient decision making because leadership is shared.

• It can create new costs to decision making because specialized information might not easily transfer from the CEO to the chairman (the information gap).

• It can create a second layer of monitoring costs because the new chairman also poses a potential agency problem.

• It can weaken leadership during a crisis.7

According to Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS), 57 companies held a vote in 2013 on shareholder resolutions to require an independent chairman. Of these, only 4 received majority approval. Average support across all votes was 31.1 percent.11

Researchers have studied the impact of separating the chairman and CEO roles. Most studies have found little or no evidence that separation leads to improved corporate outcomes. For example, Baliga, Moyer, and Rao (1996) found that companies that announce a separation (or combination) of the roles do not exhibit abnormal positive (or negative) stock price returns around the announcement date. They also found no evidence that a change in the independence status of the chairman has any impact on the company’s future operating performance, and they found only weak evidence that it leads to long-term market value creation. They concluded that although a combined chairman/CEO “may increase potential for managerial abuse, [it] does not appear to lead to tangible manifestations of that abuse.”12 Dey, Engel, and Liu (2011) found that companies that separate the chairman and CEO roles due to investor pressure exhibit negative returns around the announcement date and lower subsequent operating performance.13 Boyd (1995) provided a meta-analysis of several papers on chairman/CEO duality and found, on average, no statistically significant relationship between the independence status of the chairman and operating performance.14

Research also suggests that companies are more likely to separate the chairman and CEO roles for succession purposes and are less likely to do so to improve management oversight. Grinstein and Valles Arellano (2008) examined a sample of companies that created nonexecutive chairs between 2000 and 2004. They found that the majority did so with the outgoing chairman/CEO retaining the title of chairman until his or her successor as CEO gained sufficient experience. In these cases, adopting a nonexecutive chairman was a means of providing stability during a period of transition. Only in a minority (20 percent) of the sample did an independent director assume the chairmanship. In these companies, the appointment of an independent chairman was more likely to follow a period of poor operating performance and, therefore, likely was driven by an attempt to improve corporate oversight.15

Brickley, Coles, and Jarrell (1994) reached similar conclusions. They found that firms that separate the chairman and CEO roles almost always appoint a former officer with relatively high stock ownership to the chair. They argued that this structure reduces the cost of sharing information. The authors also found that companies use the chairmanship as a reward to newly appointed CEOs who perform well during a preliminary period. They concluded that a dual chairman/CEO is an important tool in succession planning and that forcing a separation likely creates costs that outweigh the benefits.16

The evidence therefore suggests that an independent chairmanship is likely not a governance practice that definitively improves corporate outcomes. However, it is also not a structure that has been shown to destroy shareholder value.17 The circumstances under which this structure is beneficial will likely vary depending on the specific situation. Research does not support mandating the split for all companies. As a Wall Street Journal columnist glibly stated, “It’s a good idea for companies for which it is a good idea.”18

Lead Independent Director

The position of lead independent director has emerged as somewhat of a compromise between allowing companies to maintain dual chairman/CEO positions and forcing companies to separate these roles and appoint an independent chairman. The position evolved from the role served by the director who presides over executive sessions of the board. The New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) requires that nonexecutive directors meet outside the presence of management in regularly scheduled executive sessions and that an independent director preside over these meetings. In recent years, this director has assumed a more prominent role with expanded powers and has come to be known as the lead independent (presiding) director.

Many corporate governance experts recommend that companies formally appoint a lead independent director, particularly those in which the CEO also serves as chairman of the board. The expectation is that the lead independent director can serve as an important counterbalance to the chairman/CEO. However, beyond presiding over executive sessions, the responsibilities of this role are still being defined and vary widely across companies.

According to Spencer Stuart, the lead director at most companies serves as liaison between the chairman/CEO and independent directors. This person also plays a prominent role in the evaluation of corporate performance, CEO succession planning, director recruitment, and board and director evaluations. Sometimes the lead director serves as the main contact to receive and address shareholder communications.19 He or she can particularly be important during times of crisis, including periods of increased government or regulatory scrutiny, hostile takeover attempts, and contentious proxy battles. In these situations, the lead director brings clarity of communication and clear leadership to internal and external stakeholders.

To be effective, the lead director needs many of the same attributes required of the chairman, including communication and listening skills, diplomacy, and an ability to gain confidence. The lead director must also be willing to take stands that are counter to those of management and, in doing so, compel change. According to one director, “The person has to care for the spirit of the board. He or she needs to be committed to integrity, loyalty, and equanimity. [Y]ou need someone in this role who calls for candor and makes people feel safe about asking the tough and proverbial ‘dumb’ questions.”20 However, the lead director should not become too involved in management issues, particularly during a crisis.

Experts believe that lead directors can contribute to improved corporate performance in these ways:

• Taking responsibility for improving board performance

• Building a productive relationship with the CEO

• Supporting effective communications with shareholders

• Providing leadership in crisis situations or in turbulent times

• Ensuring that the board is engaged effectively in developing corporate strategy

• Leading the board in succession planning for the CEO and senior management and for the board and its leaders21

Although the board should already be discussing these items, appointing a lead director might accelerate the process. Anecdotal evidence suggests that this can be accomplished by concentrating responsibility for selected matters in the hands of one capable director and granting him or her authority to act. Several examples of successful lead directors can provide a model for other companies to emulate. However, as these examples indicate, the lead director is likely to succeed only if given sufficient autonomy and if the chairman or other board members don’t undermine his or her authority (see the following sidebar).

The research literature on lead independent directors is modest because it is difficult to distinguish between companies that have a truly empowered lead director and those that grant that title to the director who presides over executive sessions. Still, some evidence suggests that lead independent directors improve governance outcomes. Larcker, Richardson, and Tuna (2007) found that appointing a lead independent director, in combination with other factors, is associated with improved future operating performance and stock price returns.24

The benefit of a lead director likely will depend on the governance situation of the firm and the personal qualities of the director selected.

Outside Directors

As discussed in Chapter 2, “International Corporate Governance,” securities regulations in most developed countries require that companies have a majority of outside (nonexecutive) directors. Outside directors are expected to execute their duties without undue influence from management because they have no reporting lines to the CEO and do not rely on the company for their livelihood. They are also expected to draw on their professional backgrounds and lend functional expertise to advise on the company strategy and business model. Therefore, they are expected to be better suited to fulfill the advisory and monitoring functions of the board than inside directors.

However, outside directors are likely to be less informed about the company than inside directors. We referred to this earlier as the “information gap” and noted that such a gap is more likely to occur when specialized knowledge is required to run the company. When an information gap occurs, decision making can suffer. Decision making can also suffer through lack of independence. Although companies are required to meet the independence standards of listing exchanges, outside directors who meet these standards in a technical sense are not guaranteed to be truly independent. Some governance experts point out that insiders can coopt the board by nominating outside directors who appear to be independent but are not.25 Alternatively, outside directors might be independent but not adequately engaged or qualified. When this occurs, numerical targets for outside representation become ineffective (see the following sidebar).

Research indicates that investors generally look favorably upon companies that add outside directors to the board. Rosenstein and Wyatt (1990) found that adding an outside director to the board leads to a statistically significant increase in stock price around the announcement date.28 Interestingly, the addition of an insider to the board is greeted with a negative reaction by shareholders if the insider owns only a small amount of company stock but is greeted with a positive reaction if the insider owns a large amount of stock. Apparently, investors understand the potential trade-off between the information advantage of insiders and their potential for self-dealing, and they expect high stock ownership to help mitigate this risk. Nguyen and Nielsen (2010) found that the stock market reacts negatively to the sudden death of an outside board member and that the stock price reaction is more negative when that board member serves a critical role, such as chairman or head of the audit committee or when overall representation on the board by outside directors is low. Conversely, the stock price reaction is less negative when the outside director has been on the board for a long period of time or was appointed during the current CEO’s tenure.29

The impact of outside directors on the long-term operating performance of the company is less clear. Bhagat and Black (2002) found almost no relationship between the percentage of outsiders on a board and the long-term performance of the company’s stock.30 In contrast, Knyazeva, Knyazeva, and Masulis (2013) found that outside board members have a positive effect on firm value and operating performance.31 Duchin, Matsusaka, and Ozbas (2010) found that the effectiveness of outside directors depends on the cost of acquiring information about the firm. When it is easy for outsiders to gain expertise on the firm (because the firm is in a straightforward industry), company performance increases following the appointment of outsiders to the board. When it is difficult for outsiders to gain expertise, company performance decreases following their appointment.32

Boards with a higher percentage of outside directors might also make better decisions regarding mergers and acquisitions. Cotter, Shivdasani, and Zenner (1997) found that when a company announces an acquisition, the stock price change of the acquiring firm is more negative if its board consists largely of executive directors than if the board consists mostly of nonexecutive directors. The expectation is that an acquisition is more likely to destroy value through empire building if executive directors have negotiated the purchase price. Similarly, companies receive a higher takeover premium if the board of the target company is independent.33 Byrd and Hickman (1992) found similar results. The results suggest that a board composed of outsiders is more likely to negotiate arm’s-length transactions, thereby ensuring that the targets and takeover prices are rational.34

Finally, it is not clear whether boards with a higher percentage of outsiders negotiate more rational compensation packages with CEOs. Boyd (1994) found an unexpected positive relationship between the level of CEO compensation and the percentage of outside directors.35 However, Finkelstein and Hambrick (1989) found no relationship between these variables.36

Clearly, outside directorships have both positive and negative aspects. Outsiders have the potential to bring expertise and independence to the board, which can reduce agency costs and improve firm performance. However, outsiders operate at an information disadvantage that can decrease their effectiveness. The research results on this point are mixed, and shareholders should evaluate board members based on their experience and the relevance of that experience in monitoring and advising management.

Board Independence

The NYSE requires that listed companies have a majority of independent directors. Independence is defined as having “no material relationship with the listed company (either directly or as a partner, shareholder, or officer of an organization that has a relationship with the company).”37 A director is not considered independent if the director or a family member:

• Has been employed as an executive officer at the company within the past three years

• Has earned direct compensation in excess of $120,000 from the company in the past three years

• Has been employed as an internal or external auditor of the company in the past three years

• Is an executive officer at another company where the listed company’s present executives have served on the compensation committee in the past three years

• Is an executive officer at a company whose business with the listed company has been the greater of 2 percent of gross revenues or $1 million within the past three years

These standards are intended to ensure that directors execute their duties with independent judgment.38 Independence is important for both the advisory and monitoring functions of the board. It enables a director to objectively evaluate the top executives, strategy, business model, and risk-management policies proposed by senior management. It also enables them to be objective when measuring operating and financial results against predetermined targets. Independence means that compensation arrangements are established through arm’s-length negotiation and that acquisitions are determined in the best interest of shareholders. Directors who maintain material relations with the company or otherwise rely on the company for their livelihood are less likely to be independent in these areas. According to MSCI ESG Research, the boards of Cablevision, Kinder Morgan, J.M. Smucker, and Brown-Forman were among the least independent in 2014; MasterCard and Unum Group scored among the most independent.39

The risk for investors is that the independence standards of the NYSE (or other listing exchanges) do not reliably produce directors with truly independent judgment. The NYSE acknowledges this risk:

It is not possible to anticipate, or explicitly to provide for, all circumstances that might signal potential conflicts of interest, or that might bear on the materiality of a director’s relationship to a listed company. . . . Accordingly, it is best that boards making “independence” determinations broadly consider all relevant facts and circumstances.40

Effectively, NYSE guidelines draw a line in the sand. For investors, this means that some directors will meet independence standards and not be independent in their perspectives, while others will not meet these standards yet be perfectly capable of maintaining independence. Stated differently, there is a risk that the structural characteristics used in the NYSE test for independence are a misleading measure of the independence of an individual director (see the following sidebar).

Most studies fail to find a significant relationship between formal board independence and improved corporate outcomes. We cited some of these studies in the previous section on outside directors. In aggregate, they tend to demonstrate either a modest relationship or no relationship between independence and market returns or long-term performance. Some evidence suggests that independence leads to more rational merger-and-acquisition activity. The relationship between independence and CEO compensation is not clear. We suspect that the structural shortcomings of the NYSE standards of independence confound the data used in most studies and at least partially explain the weak results.

Hwang and Kim (2009) recognized this shortcoming and attempted to correct it by designing a study that takes into account situational or psychological factors beyond NYSE guidelines that risk compromising a director’s judgment. The authors made a distinction between directors who are independent according to NYSE standards (conventionally independent) and those who are independent in their social relation to the CEO (socially independent). They used the board of Cardinal Health to illustrate this distinction:

In the year 2000, this board had 13 directors, 10 of whom were conventionally independent of the CEO. However, one conventionally independent director was not only from the same hometown, but also graduated from the same university as the CEO (incidentally, this director provided a job, at his own firm, for the CEO’s son). Another conventionally independent director graduated from the same university and specialized in the same academic discipline as the CEO. Similarly, 3 others shared informal ties with the CEO and, ultimately, only 5 of the 13 directors were conventionally and socially independent of the CEO.

The authors identified six areas where the independence standards of the NYSE might fail to take into account social relationships that could compromise independence if the director and the CEO have the following in common:

1. Served in the military

2. Graduated from the same university (and were born no more than three years apart)

3. Were born in the same U.S. region or the same non-U.S. country

4. Have the same academic discipline

5. Have the same industry of primary employment

6. Share a third-party connection through another director to whom each is directly dependent

The authors posit that people who share these social connections feel a psychological affinity that might bias them to overly trust or rely on one another without maintaining sufficient objectivity. Among a sample of directors of Fortune 100 companies between the years 1996 and 2005, the authors found that 87 percent are conventionally independent, but only 62 percent are both conventionally and socially independent. They found that social dependence is correlated with higher executive compensation, lower probability of CEO turnover following poor operating performance, and higher likelihood that the CEO manipulates earnings to increase his or her bonus. They concluded that social dependence compromises the ability of the board to maintain arm’s-length negotiations with management.41

Other studies that take an unconventional approach to measuring independence reach similar conclusions. Coles, Daniel, and Naveen (2014) hypothesized that directors appointed by the current CEO are more likely to be sympathetic to his or her decisions and therefore less independent (“coopted”). Consistent with this, they found that the greater the percentage of the board appointed during the current CEO’s tenure, the worse the board performs its monitoring function—measured in terms of pay level, pay-for-performance sensitivity, the likelihood that an underperforming CEO is terminated, and merger and acquisition activity. They concluded that “not all independent directors are effective monitors” and that “independent directors that are coopted behave as though they are not independent.”42 Similarly, Fogel, Ma, and Morck (2014) found that “powerful” independent directors (directors with a large social network) are associated with more valuable merger-and-acquisition activity, stricter oversight of CEO performance, and less earnings management.43

Although this type of analysis is certainly not easy, it demonstrates a level of critical thinking that is sometimes absent in the debate on corporate governance. Their findings suggest that an expanded and more sophisticated assessment of independence is likely to lead to better understanding of governance quality than simply checking for adherence with regulatory guidelines.

Independent Committees

The Sarbanes–Oxley Act of 2002 requires that the audit, compensation, and nomination and governance committees of U.S. publicly traded companies include only independent directors. By contrast, other specialized committees of the board—such as finance and investment committees, credit committees, and science and technology committees—carry no such restrictions and often have a combination of inside and outside directors.

The issues regarding committee independence are similar to those regarding general board independence. Independent committees have the potential to objectively monitor managerial behavior and corporate performance, but committees with inside directors might have firm-specific knowledge that can improve their contribution to long-term operating performance. Independence standards mandated by the Sarbanes–Oxley Act are intended to balance these trade-offs. Committees with a primary charter to monitor the performance of management (audit, compensation, and nomination and governance) carry a legal mandate for independence. All other committees that serve both an advisory and a monitoring function (finance, environmental, science and technology, and others) don’t carry these mandates.

The research literature produces some evidence that independent directorships improve the monitoring ability of the audit committee. Klein (2002) found that companies with a majority of independent directors on the audit committee have higher earnings quality than companies with a minority of independent directors on this committee. However, she did not find that a standard of 100 percent independence improves results compared to a simple majority. (The sample period preceded NYSE requirements for 100 percent independence.) She concluded that although independence on the audit committee might be important, “a wholly independent audit committee may not be necessary.”44

In a separate study, Klein (1998) tested whether having insiders on the investment and finance committees improves firm performance. She reasoned that although the audit committee is intended as an oversight body to mitigate agency costs, investment and finance committees are focused on strategic growth, so they should benefit from an insider’s firm-specific knowledge. She found slight evidence in support of this hypothesis: Companies with a higher percentage of executive directors on the investment and finance committees tend to exhibit slightly better operating returns and stock market performance. She did not find this same correlation for audit and compensation committees.45

These studies suggest that the independence level of committees bears some influence on corporate outcomes. They also support the thesis that having inside directors on committees is neither uniformly positive nor uniformly negative. As we might expect, it depends on the function of the committee.

Bankers on the Board

Bankers play a prominent role on many corporate boards. They bring expertise regarding a firm’s capital structure, financing options, financial risk, and mergers and acquisitions. They also bring industry knowledge gained from serving clients in similar businesses. During times of trouble, they can help facilitate access to capital, particularly when a company is “priced out” of the public markets because of a low credit rating. Bankers also bring monitoring expertise that comes from having a creditor perspective, with an emphasis on compliance with covenants and excess coverage. This enables them to detect and address early signs of trouble.

However, bankers might not be fully independent monitors because they have a divided loyalty between their employers and the company on whose board they sit. Some might use their positions to steer business toward their banks. This violation of fiduciary duty is often hard to detect. Also, when the banker’s employer provides financing to the company, the bank’s interest as creditor might conflict with the interest of shareholders.

Research on the contribution of bankers to company boards is generally unfavorable. Güner, Malmendier, and Tate (2008) found that companies that add commercial bankers to the board tend to increase their borrowing activity but do not realize a corresponding increase in firm value. The evidence suggests that the increase in borrowing activity is encouraged to generate low-risk profits for the lending institution. Furthermore, the authors found no evidence that companies gain access to funds that they could not otherwise receive on their own. Also, the authors found that companies that add investment bankers to the board tend to make worse acquisitions. Stock price returns for the acquiring firm are about 1 percent less on the announcement date when investment bankers are on the board. This conflicts with the notion that investment bankers can create value by negotiating better deals. The findings suggest that bankers who sit as outside directors put the interest of their employers above their obligation to company shareholders.46 Studies on the impact of bankers in Germany and Japan arrive at similar conclusions.47

Erkens, Subramanyam, and Zhang (2014) also examined the impact of commercial bank representation on governance outcomes. They hypothesized that representation by an affiliated banker on a company’s board gives the bank more direct access to information about performance, therefore reducing market pressure to adopt conservative accounting to establish creditworthiness. They found evidence in support of this hypothesis. They also found that banker representation allows lenders to renegotiate debt covenants in a more timely manner, based on private information.48 This study, too, suggests that bankers use their position to protect the interests of their employers.

At the same time, evidence exists that banking experience on the board can be beneficial to the company when the director is not conflicted by a relationship between his or her employer and the company. Huang, Jiang, Lie, and Yang (2014) found that directors with previous investment banking experience improve the outcome of mergers-and-acquisition activity. Companies with investment banking directors exhibit higher returns when announcing an acquisition, pay lower takeover premiums and advisory fees, and exhibit superior performance post-acquisition. This suggests that directors with investment banking experience might help a firm make better acquisitions by identifying suitable targets and reducing the cost of the deals.49

Financial Experts on Board

Section 407(b) of the Sarbanes–Oxley Act requires that companies appoint a financial expert to the audit committee. To qualify as a financial expert, the director must have experience as a public accountant, auditor, principal financial officer, comptroller, or principal accounting officer at an issuer. The director also is required to have an understanding of accounting principles, the preparation of financial statements, internal controls, and audit committee functions.50

The evidence suggests that adding a financial expert to the audit committee improves governance quality. Defond, Hann, and Hu (2005) found that the market reacts favorably when a financial expert is added to the audit committee. They also divided the sample of financial experts into two groups and found that the market reacts positively to the appointment of experts with accounting backgrounds but not those with nonaccounting financial backgrounds. Their results indicate that shareholders value audit committee members who can directly improve the integrity of financial statements.51 Similarly, Agrawal and Chadha (2005) found that companies have fewer restatements when an audit committee member has a CPA or similar degree.52 Krishnan (2005) found that companies that have financial expertise on the audit committee are less likely to have problems with their internal controls.53

Politically Connected Boards

Some companies believe that it is beneficial to add a politically connected director to their board. The director can use his or her professional network or knowledge to help secure government contracts or improve relationships with regulators. Other companies establish political connections when a senior officer leaves the company to take a high-level appointment in the administration or a federal agency.

Modest evidence indicates that investors look favorably upon politically connected boards. Faccio (2006) and Hillman, Bierman, and Zardkoohi (1999) found that investors react positively to news that a company CEO or board member has received a political appointment.54 Similarly, Goldman, Rocholl, and So (2009) found that companies whose board members were affiliated with the Republican party exhibited positive stock price returns following the election of George W. Bush in 2000.55

However, these connections might not yield tangible benefits. Fisman, Fisman, Galef, and Khurana (2006) studied the influence of firm connections to former U.S. Vice President Richard Cheney, who previously served as CEO of Halliburton. They found no evidence that companies benefited from these ties.56 Faccio (2010) found that companies with political connections have lower taxes and greater market power but that they also have lower return on assets and lower market-to-book ratios than peers.57 Studies of French companies have reached similar conclusions.58

Employee Representation

German law requires that the supervisory boards of German corporations have 33 percent employee representation when the company has 500 or more employees and 50 percent employee representation when the company has 2,000 or more employees. This requirement is considered an employee’s right of codetermination and ensures that employees participate in decisions that impact workplace matters such as work rules and schedules, methods for appraising and hiring personnel, the design of health and safety work standards, wage and benefits agreements, and the process for introducing technology into production. Through board seats, employees also have input into high-level corporate matters such as strategy, operations, capital structure, and management oversight. Codetermination has the potential to give employees a real voice in the governance process.

A prudent level of employee involvement can be desirable for decision making. Employees have valuable information about daily business processes, customers, and suppliers. Board representation can facilitate the flow of this information between employees and management. Employee representation can also improve internal relations and reduce work stoppages. In addition, employee representation can reduce agency costs through better oversight of management compensation and perquisites. However, board representation puts employees in a position to engage in higher levels of rent extraction (such as demanding artificially inflated wages or employment numbers). This can reduce a company’s competitive position.

The academic evidence on employee representation is mixed. Gorton and Schmid (2004) found that the stock of German companies with higher levels of employee representation (50 percent of directors) trade at lower prices than the stock of companies with lower levels of employee representation (33 percent of directors).59 Fauver and Fuerst (2006) found that employee representation is positively related to market valuation in industries that require high levels of coordination (such as manufacturing, transportation, and wholesale or retail trade) and in concentrated industries with less competition. Modest evidence shows that the benefits of employee representation form an “inverse U,” meaning that some level of employee representation improves firm valuation, but beyond a certain threshold, it leads to diminishing returns. Companies with employee representation are more likely to pay a dividend, which reduces expropriation of capital by management.60 Using a sample of publicly traded French corporations, Ginglinger, Megginson, and Waxim (2011) also found modest evidence that employee representation on the board is positively associated with firm value and profitability.61

These studies involve European corporations, so it is not clear how they translate to the United States, where employee representation is not required (see the following sidebar). However, studies that have examined firms that are essentially employee owned through employee stock ownership plans (ESOPs) tend to reach negative conclusions. Faleye, Mehrotra, and Morck (2006) examined the performance of companies in which labor owns at least 5 percent of shares and, therefore, has a voice in corporate decision making. They found that such firms have lower valuations, invest less in long-term assets, are more risk averse, exhibit slower growth, have lower employment growth, and have lower labor productivity. They concluded that employee influence conflicts with an objective of maximizing shareholder value.62

However, anecdotal evidence suggests that employee participation in corporate decision making, at either the board level or managerial level, can be beneficial in certain circumstances. For example, Southwest Airlines is known for granting significant autonomy to pilots and flight crews to make adjustments that improve efficiency and increase customer satisfaction. Whether board representation is required for operational benefits to be realized is not clear. We suspect that the effectiveness of employee board representation depends on the nature of the existing relations between management and labor, as well as the culture and competitive positioning of the firm.

Boards with “Busy” Directors

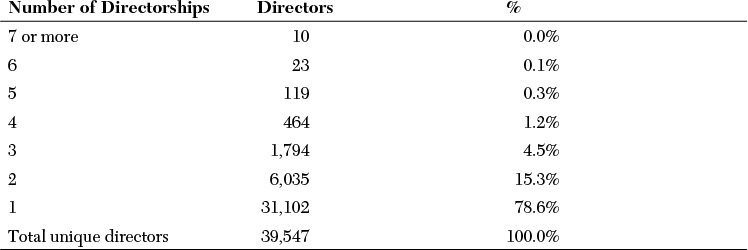

The vast majority (79 percent) of board members in the United States serve on just one corporate board. A fair number sit on two or three boards, but the numbers drop off significantly beyond that. According to data from Equilar, fewer than 1 percent of directors sit on five or more boards (see Table 5.2).66

Source: Data collected by Equilar and computations by the authors. Data for companies with fiscal year ending between June 2012 and May 2013.

Table 5.2 Number of Directorships per Director

Researchers refer to directors who hold multiple board seats as busy directors. The numeric threshold that constitutes a “busy” director is undefined, although researchers generally consider it to be three or more board seats. Similarly, academics refer to a “busy” board as one in which a significant number of directors are busy.

Having a busy director can bring potential benefits. Busy directors are likely to have firsthand access to important information about operations, strategy, and finances at related companies. They are also likely to have broad social and professional networks, which are valuable for recruiting directors, evaluating executive talent, dealing with regulators, and forging partnerships. In addition, busy directors might have high integrity and sound reputations, which are driving factors in the demand for their services. However, busy directors also have the potential to be lax in their oversight or unavailable at critical moments because of outside obligations (see the following sidebar). Recognizing these risks, many companies place restrictions on the number of boards that their directors can sit on simultaneously. According to Spencer Stuart, more than three-quarters (76 percent) of S&P 500 companies had such a restriction in 2013.67

Researchers have studied the relationship between busy boards and governance quality, which is one of the few areas of research on board structure that yields consistent and convincing results: Companies with busy boards tend to have worse long-term performance and worse oversight. Fich and Shivdasani (2006) found that companies with busy boards have lower market-to-book ratios and lower return on assets. They also found that companies with busy boards are less likely to fire an underperforming CEO than companies that do not have busy boards. In addition, they demonstrate that investors react positively to news that a busy director is resigning from the board and negatively to news that an outside director is assuming an additional directorship. Investor response is most negative if the outside director or the board itself becomes “busy” after assuming the additional directorships.71

Many other studies have found similar results. For example, Core, Holthausen, and Larcker (1999) examined a variety of governance variables (busy directors, old directors, directors appointed by the CEO, and so on) to measure their impact on future firm operating performance and other variables, such as CEO compensation. They found that busy boards award larger compensation packages to CEOs than nonbusy boards. Companies with busy boards also exhibit lower one-, three-, and five-year operating performance (measured as return on assets) and stock market returns.72

Falato, Kadyrzhanova, and Lel (2013) found that the stock market reacts more negatively to the sudden death of an independent director when the remaining workload has to be redistributed among busy directors than nonbusy directors. Their evidence suggests that the magnitude of the decline depends on the importance of the deceased directors’ committee roles in the firm, that the performance deficit among busy boards persists over time, and it is accompanied by reduced board monitoring (that is, higher CEO rent extraction and lower earnings quality). They conclude that “independent director busyness is detrimental to board monitoring quality.”73

Field, Lowry, and Mkrtchyan (2013) argued that busy directors are ineffective monitors but are important corporate advisors. They cited as evidence the prominence of busy directors among firms undergoing an initial public offering (IPO) and the contribution of those directors to firm value. They note that the benefits of busyness are “lowest among Forbes 500 firms, which likely require more monitoring than advising.”74

Interlocked (or Connected) Boards

An interlocked board is one in which an executive of one firm sits on the board of another and an executive of the second firm sits on the board of the first. According to one estimate, 8 percent of boards are interlocked through reciprocal CEO representation. When the definition is expanded to include retired CEOs and other current senior executives, the percentage of companies with interlocked boards increases to 20 percent.75

Interlocking creates a network among directors that can lead to increased information flow, which, in turn, improves decision making. Best practices in corporate strategy and firm oversight can be transferred more efficiently across companies that have shared board representation. Director networks also serve as a source of important business relationships, including new clients, suppliers, sources of capital, political connections, regulators, and director and executive referrals.

However, obvious drawbacks exist in this arrangement. Interlocking can become anticompetitive if proprietary information is shared among competing firms that use this information to collude on market actions.76 Furthermore, interlocking creates a dynamic of reciprocity. For example, if the CEO of one firm approves a large compensation contract to the CEO of another firm, it is difficult for the second CEO not to reciprocate. As such, interlocks can compromise the objectivity of directors and weaken their monitoring capability.

Research demonstrates the positive effects of network connections among firms. Hochberg, Ljungqvist, and Lu (2007) found that such connections improve performance of companies in the venture capital industry.77 Fracassi and Tate (2012) found that companies that share network connections at the senior executive and the director level have greater similarity in their investment policies and higher profitability. These effects disappear when the network connections are terminated.78 Cai and Sevilir (2012) found that board connections between firms lead to higher value creation in mergers and acquisitions.79 Larcker, So, and Wang (2013) found that companies with a well-connected board have greater future operating performance and higher future stock price returns than companies whose boards are less connected. These effects are most pronounced among companies that are newly formed, have high growth potential, or are in need of a turnaround.80

Research also demonstrates the role that network connections play in the dissemination of business practices (good and bad). Bizjak, Lemmon, and Whitby (2009) found that the practice of stock-option backdating, which originated among a localized set of companies, was transferred to many more through boardroom connections.81 Brown and Drake (2014) found that tax avoidance strategies are shared across board networks.82 Cai, Dhaliwal, Kim, and Pan (2014) found that corporate disclosure policies—in particular the decision to stop issuing quarterly earnings guidance—are also shared through network connections.83

The evidence also indicates that network connections can lead to decreased monitoring. Hallock (1997) found some weak evidence that CEOs of companies with interlocked boards earn higher compensation than the CEOs of companies with noninterlocked boards.84 Nguyen (2012) found that CEOs whose firms are connected through interlocked boards are less likely to be fired following poor performance.85 Finally, Santos, Da Silveira, and Barros (2009) found evidence that companies with interlocked boards in Brazil have lower market valuations. The results are especially strong for boards that are both interlocked and busy.86

Committee Overlap

A separate body of work examines whether committee overlaps—the degree to which directors serve on multiple committees—improve or impair monitoring functions through better information flow. For example, it might be the case that a director who serves on the audit committee will be a more effective contributor if he or she sits concurrently on the compensation committee. Because compensation contracts are based in part on the achievement of accounting-based performance metrics, a director’s understanding of financial accounting might allow for improved compensation contracting. A director with audit committee experience will be in a better position to understand which components of reported earnings are more informative about CEO decisions (and also less susceptible to manipulation), allowing the committee to write bonus contracts with greater weight on these components.

There is some evidence that these benefits do, in fact, manifest themselves. Carter and Lynch (2009) found that concurrent membership on audit and compensation committees is associated with lower weighting placed on discretionary accounting accruals that might be more susceptible to manipulation and greater weight on stock-return metrics in compensation contracts.87 Similarly, Grathwohl and Feicha (2014) found among a sample of publicly listed firms in Germany that overlap between the audit and compensation committees is associated with higher bonus payments and higher pay-for-performance sensitivity of those bonuses.88

Conversely, there are potential benefits to having members of the compensation committee serve on the audit committee. Compensation committee members will have more detailed knowledge about the incentives that executives have to make accounting choices to maximize compensation and to assess the business risk created by the compensation structure. While the research literature in this area is less developed, there is some evidence that this might occur. Chandar, Chang, and Zheng (2012) found that firms with overlapping membership between the two committees are associated, on average, with higher financial reporting quality.89

Companies exhibit widely varying practices when it comes to audit and compensation committee overlaps. In 2012, 26 percent of publicly traded companies in the United States had no overlapping members between the compensation and audit committees, 33 percent had one overlap, 25 percent two overlaps, and 16 percent three or more overlaps. In approximately one-third of companies (32 percent), the audit committee chair also served on the compensation committee. In a similar percentage of cases (35 percent), the compensation committee chair served on the audit committee. In 6 percent of companies, the audit committee and compensation committees had exactly the same members.90

In the extreme, companies appoint all independent directors to all standing committees so that every committee effectively has 100 percent overlap. This arrangement is known as a “committee of the whole” and is intended to foster knowledge dissemination across the entire board. Because directors participate in all functional discussions, they have greater exposure to the details of the firm’s operations and governance. A committee-of-the-whole structure requires significant time commitment.

Only a slim minority of companies (3.4 percent) employ a committee-of-the-whole structure.91 Goldman Sachs, Coach, Nucor, Moody’s, and A.H. Belo are examples of companies that have committees of the whole, although their regulatory filings provide little insight into their decision to adopt this structure.

More research is needed to understand the trade-offs and benefits of committee overlap and the settings in which they are most likely to be beneficial.

Board Size

The size of the board of directors tends to be related to the size of the corporation. Companies with annual revenues of $10 million have 7 directors, on average, and companies with revenues of more than $10 billion have 11 directors, on average.92

Large boards have more resources to dedicate to both oversight and advisory functions. They allow for greater specialization to the board through diversity of director experience and through functional committees. However, large boards bring additional costs in terms of compensation and coordination of schedules. In addition, large boards suffer from slow decision making, less candid discussion, diffusion of responsibility, and risk aversion. Given the trade-offs, many experts believe a theoretically optimal board size exists. For example, Lipton and Lorsch (1992) argued that boards of directors should have either 8 or 9 members and should not exceed 10.93

Researchers have examined the relationship between board size and corporate performance. Yermack (1996) measured the relationship between board size and firm value (measured as the ratio of market-to-book value). He found that as board size increases, firm value falls (after controlling for factors such as firm size and industry). The largest deterioration in value occurs between boards of 5 and 10 directors, suggesting that inefficiencies grow the most within this range. Yermack (1996) also found that larger boards are less likely to dismiss underperforming CEOs, they are less likely to award compensation contracts that correlate with shareholder value, and shareholders respond negatively to announcements that a company is increasing its board size. The author concluded that “an inverse association between board size and firm value” exists.94

However, as with other structural board variables that we have considered, the truth is more complicated. Coles, Daniel, and Naveen (2008) argued that a variety of other factors likely influence the relationship between board size and firm value. They identified “complexity” as one such variable. The authors argued that complex companies (those with many business segments, those that require external contracting relationships, leveraged firms, and those in specialized industries) might benefit from large boards because they bring more information to the decision-making process. As an example, they cited the board of Gulfstream Aerospace, which included at one point Henry Kissinger, Donald Rumsfeld, and Colin Powell. The authors speculated that “most likely these directors were selected not for monitoring, but for their ability to provide advice in obtaining defense contracts.” If this is the case, a large board should have positive performance effects at complex companies where incremental expertise is needed. The authors tested this hypothesis by separating complex firms from so-called “simple” firms and repeating Yermack’s analysis. They found that complexity brings added explanatory power: Board size is negatively correlated with firm value for simple firms and positively correlated for complex firms (with diminishing benefits beyond a certain point). They concluded, “At the very least, our empirical results call into question the existing empirical foundation for prescriptions for smaller, independent boards. [O]ur evidence casts doubt on the idea that smaller boards with fewer insiders are necessarily value enhancing.”95

The research conducted by Coles, Daniel, and Naveen (2008) is an excellent example of how multiple factors can influence the relationship between a structural attribute and governance outcomes. At first glance, the data suggest that board size and corporate outcomes are strictly linearly related, but in reality, the relationship is more nuanced. Complexity is one explanatory variable that early research did not properly consider, and other variables also likely bear consideration when exploring composition and structure.

Board Diversity

Many stakeholders advocate that corporate officers should increase the ethnic diversity of their boards so that their composition more closely reflects the diversity of the broader U.S. population. Ethnic diversity might improve decision making by ensuring that the board has the full array of knowledge in terms of market dynamics, customer behavior, and employee concerns to succeed operationally and culturally. According to social psychologists, diversity helps boards overcome tendencies toward groupthink, in which directors reach consensus too quickly because of the way social similarities shape their perception and decision making. Diversity can also encourage healthy debate by making directors more likely to challenge one another’s viewpoints without excessive concern for maintaining harmony because of social similarity. From the standpoint of public policy, diversity is an important social value and one that is consistent with equality.96

However, some evidence suggests that boardroom diversity might detract from the quality of decision making. Social psychologists have shown that heterogeneous groups exhibit lower levels of teamwork. Differences among team members can lead to less information sharing, less accurate communication, increased conflict, lower cohesiveness, and an inability to agree upon common goals.97 If this dynamic manifests itself in the boardroom, both advice and monitoring might suffer.

Considerable professional and academic research focuses on the relationship between boardroom diversity and corporate outcomes. Not surprisingly, the results are mixed. Erhardt, Werbel, and Shrader (2003) found a significant positive relationship between diverse gender and minority board representation and corporate performance.98 Similarly, Carter, D’Souza, Simkins, and Simpson (2010) found that board diversity is correlated with higher market-to-book ratios.99 By contrast, Wang and Clift (2009) found no relationship between boardroom diversity and corporate performance, and Zahra and Stanton (1988) found a negative relationship.100

Similarly, the research on diversity and corporate decision making is inconclusive. Westphal and Zajac (1995) found that demographic similarity between the CEO and the board is correlated with higher levels of CEO compensation.101 This is consistent with the idea that social similarity can lead to reciprocity and implies that diversity in the boardroom might improve independence and oversight. However, Belliveau, O’Reilly, and Wade (1996) found that it is not social similarity but the social status of the CEO relative to other board and compensation committee members that leads to higher compensation.102 This implies that CEO power is the greater determinant of boardroom dynamics.

Female Directors

Women are significantly underrepresented on boards of directors. According to Catalyst, a nonprofit research organization dedicated to expanding opportunities for women in business, just 17 percent of the directors of Fortune 500 companies are women, compared with 50 percent of the general population and 47 percent of the workforce. Boards might lack female directors because women are underrepresented at the senior executive level. Only 18 percent of corporate officers are women.103

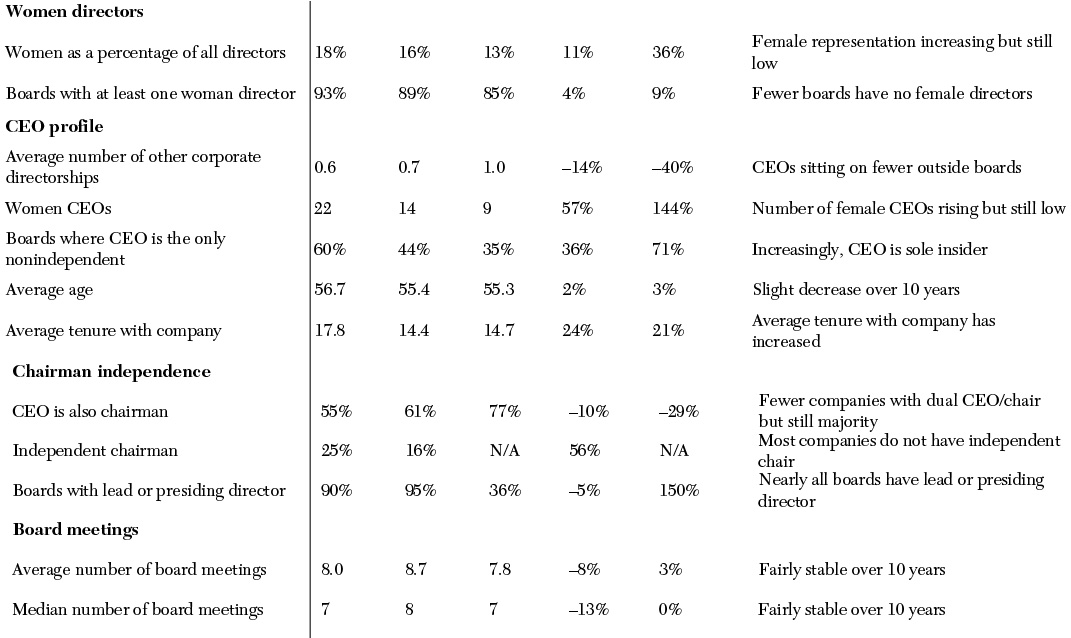

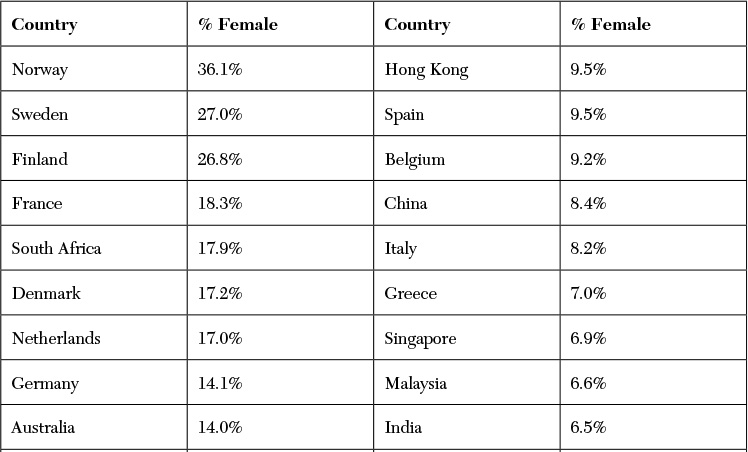

In recent years, several countries have made it a priority to increase female representation on corporate boards. Norway was the first country to pass such a law, requiring in 2003 that all listed company boards be composed of at least 40 percent female directors, with full compliance required by 2008. Companies not compliant with the law risk being delisted from exchanges. The law had an immediate impact on female board membership. In 2002, only 7 percent of directors at Norwegian companies were women. By late 2007, the figure had risen to 35 percent.104 Other European countries followed suit. Spain enacted a 40 percent requirement starting in 2015. France passed similar legislation. Sweden asked companies to voluntarily increase female directorship to 25 percent or risk a legal mandate (see Table 5.3).

Source: GMI Ratings, 2013 Women on Boards Survey.

Table 5.3 Percentage of Female Directors, by Country

Advocates of gender diversity point to the many potential benefits of increasing female representation. Gender balance can enhance board independence by encouraging healthy debate among diverse perspectives and reducing the social similarities among homogeneous groups that can lead to groupthink and premature consensus. Women might have different insights into customer behavior, particularly in industries where women are the primary purchasing agents. Women might also evaluate information and consider risk and reward differently than men, thereby improving decision making. In addition, women may exhibit higher levels of trustworthiness and cooperation, thus improving boardroom dynamics. Finally, social benefits exist for increasing gender equality on the board.

The primary risk to higher female board representation occurs when companies, in an effort to appear more gender-balanced, recruit underqualified directors. This practice, referred to as tokenism, is similar to the risk of appointing outside directors with the sole purpose of satisfying perceived external demand for diversity.

Evidence is inconclusive about whether female board representation improves corporate performance. Catalyst (2007) divided Fortune 500 companies into quartiles based on female board representation. It found that the quartile with the highest percentage of females outperformed the lowest quartile in return on equity (13.9 percent versus 9.1 percent), net margin (13.7 percent versus 9.7 percent), and return on invested capital (7.7 percent versus 4.7 percent). It also found that companies with three or more female directors performed well above average along all three financial metrics. Unfortunately, this study did not include control variables, so it likely omits important explanatory factors, such as industry, company size, or capital structure.105 More rigorous studies find no relationship between female board representation and performance.106

However, modest evidence supports the idea that female representation can improve governance quality. Adams and Ferreira (2009) found that female directors have better attendance records than men and that male directors have fewer attendance problems when women also serve on the board. They also found that boards with female representation are more likely to fire an underperforming CEO and award more equity-based compensation. They did not find a positive correlation between female board representation and either operating performance or market valuation.107

Finally, evidence suggests that female board representation can be detrimental when encouraged primarily to meet arbitrary quotas. Ahern and Dittmar (2012) examined the impact of the Norwegian law on female board representation. They found that the law led to considerable changes in board composition in terms of not only gender but also age, education, and experience. They found that the somewhat arbitrary governmental constraints of the law led to a significant decrease in firm value. They found that the loss in firm value was not primarily attributable to a greater number of female directors but to the inexperience of new directors.108

Summary

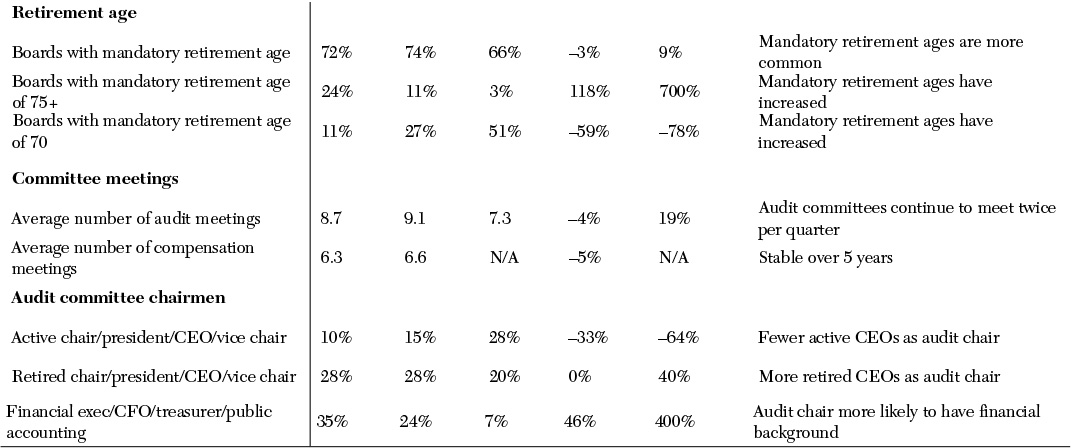

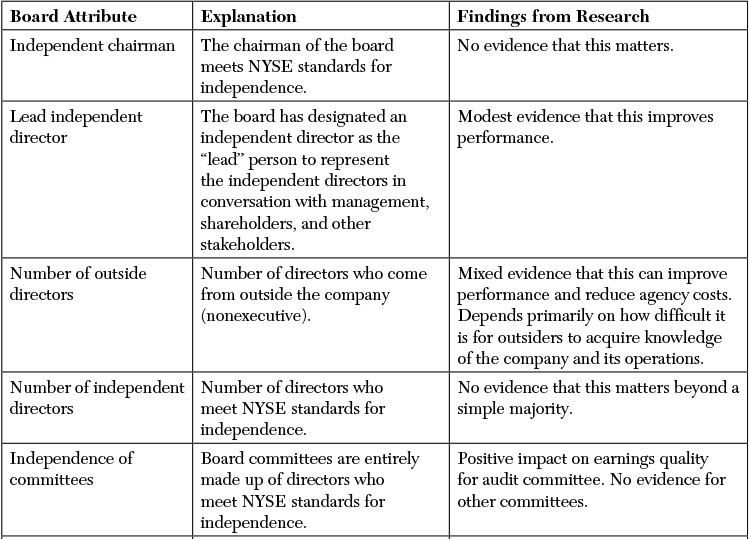

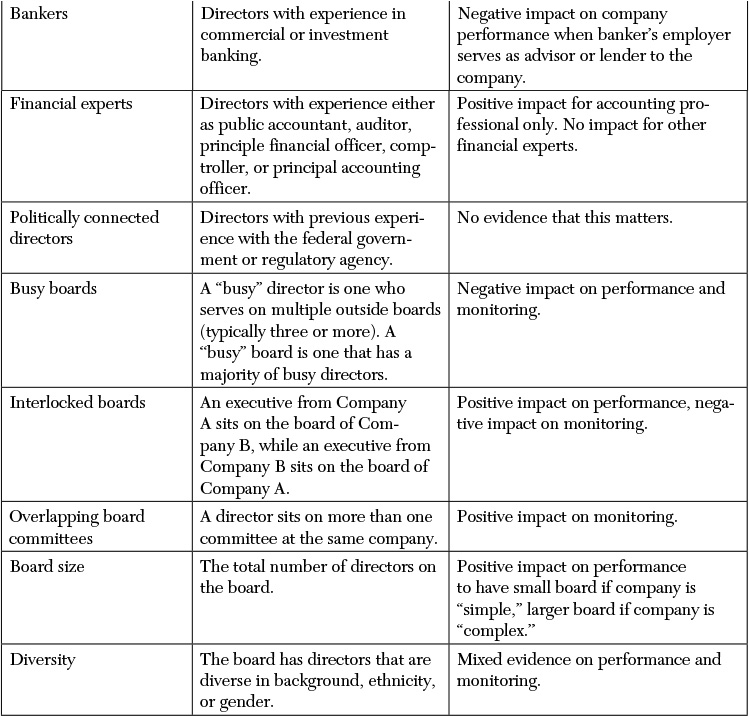

Table 5.4 presents a high-level summary of the evidence discussed in this chapter. A casual reading of this information indicates that very modest evidence supports the adoption of many of these attributes. Although this might be surprising to some, it is characteristic of the current debate on governance that is insufficiently grounded in empirical research. (We discuss this in more detail in Chapter 15, “Summary and Conclusions.”)

Source: Authors.

Table 5.4 Summary of Performance Effect for Selected Board Structural Characteristics

Endnotes

1. Spencer Stuart, “2013 Spencer Stuart U.S. Board Index” (2013). Accessed January 23, 2015. See www.spencerstuart.com/research/.

2. Directorbank, “What Makes an Outstanding Chairman? The Views of More Than 400 Directors.” Accessed May 5, 2015. See http://www.docstoc.com/docs/10282082/What-makes-a-Chairman-Outstanding_Directorbank-Survey_2008.

3. Laura M. Holson, “Former P&G Chief Named Disney Chairman,” New York Times (June 29, 2006): C13.

4. The final version of the Dodd–Frank Act did not include this provision, although it was included in earlier versions of the legislation.

5. Ross Kerber and Lisa Richwine, “Proxy Advisers Urge Split of Chair, CEO Roles at Disney,” Reuters News (February 26, 2013).

6. Spencer Stuart (2013).

7. Ira M. Millstein Center for Global Markets and Corporate Ownership, “Chairing the Board: The Case for Independent Leadership in Corporate North America, Policy Briefing No. 4,” Columbia Law School (2009). Accessed October 12, 2009. See http://web.law.columbia.edu/sites/default/files/microsites/millstein-center/2009%2003%2030%20Chairing%20The%20Board%20final.pdf.

8. Ieva M. Augstums and Mitch Weiss, “Shareholders Oust BofA Chairman,” Associated Press (April 29, 2009).

9. Bank of America, Form 8-K, Exhibit 99.1, filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission October 1, 2014.

10. Christina Rexrode and Dan Fitzpatrick, “Investors Push Back at BofA’s Reversal,” Wall Street Journal (October 31, 2014): C.1.

11. United States Research Team, “2013 Proxy Season Review United States,” ISS (2013). Accessed December 12, 2014. See http://www.issgovernance.com/library/united-states-2013-proxy-season-review/.

12. B. Ram Baliga, R. Charles Moyer, and Ramesh S. Rao, “CEO Duality and Firm Performance: What’s the Fuss?” Strategic Management Journal 17 (1996): 41–53.

13. Aiyesha Dey, Ellen Engel, and Xiaohui Liu, “CEO and Board Chair Roles: To Split or Not to Split?” Journal of Corporate Finance 17 (2011): 1595–1618.

14. Brian K. Boyd, “CEO Duality and Firm Performance: A Contingency Model,” Strategic Management Journal 16 (1995): 301–312.

15. Yaniv Grinstein and Yearim Valles Arellano, “Separating the CEO from the Chairman Position: Determinants and Changes after the New Corporate Governance Regulation,” Social Science Research Network (2008). Accessed October 10, 2009. See http://ssrn.com/abstract=1108368.

16. James A. Brickley, Jeffrey L. Coles, and Gregg A. Jarrell, “Corporate Leadership Structure: On the Separation of the Positions of CEO and Chairman of the Board,” Simon School of Business working paper FR 95-02 (1994). Accessed February 26, 2009. See http://hdl.handle.net/1802/4858.

17. David F. Larcker, Gaizka Ormazabal, and Daniel J. Taylor, “The Market Reaction to Corporate Governance Regulation,” Journal of Financial Economics 101 (2011): 431–448.

18. Holman W. Jenkins, Jr., “A Non-Revolution at Microsoft,” Wall Street Journal (February 5, 2014, Eastern edition): A.15.

19. Spencer Stuart, “A Closer Look at Lead and Presiding Directors, Cornerstone of the Board,” New Governance Committee (2006). Accessed May 5, 2015. See http://content.spencerstuart.com/sswebsite/pdf/lib/Cornerstone_LeadPresiding_Director0306.pdf.

20. Ibid.

21. Jeff Stein and Bill Baxley, “The Role and Value of the Lead Director—A Report from the Lead Director Network,” Harvard Law School Corporate Governance Blog (August 6, 2008). Accessed May 3, 2015. See http://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2008/08/06/the-role-and-value-of-the-lead-director-a-report-from-the-lead-director-network/.

22. Joann S. Lublin, “Theory & Practice: New Breed of Directors Reaches Out to Shareholders; Treading a Fine Line between Apologist, Sympathetic Ear,” Wall Street Journal (July 21, 2008, Eastern edition): B.4.

23. Chris Redman, “Shell Rebuilds Itself,” Corporate Board Member (March/April 2005). Accessed May 5, 2015. See http://shellnews.net/week12/corporate_board_member_magazine21march05.htm. See also David F. Larcker and Brian Tayan, “Royal Dutch/Shell: A Shell Game with Oil Reserves,” Stanford GSB Case No. CG-17 (2009).

24. Those factors include a lead director, greater proportion of blockholders, and a compensation mix that is weighted toward accounting performance, smaller boards, and fewer busy directors. See David F. Larcker, Scott A. Richardson, and Írem Tuna, “Corporate Governance, Accounting Outcomes, and Organizational Performance,” Accounting Review 82 (2007): 963–1008.

25. Roberta Romano, “The Sarbanes–Oxley Act and the Making of Quack Corporate Governance,” Yale Law Journal 114 (2005): 1521–1612.

26. Lehman Brothers, Form DEF 14A, filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission March 5, 2008.

27. Dennis K. Berman, “Where Was Lehman Board?” Wall Street Journal Blog, Deal Journal (September 18, 2008). Accessed November 9, 2010. See http://blogs.wsj.com/deals/2008/09/15/where-was-lehmans-board/.

28. Stuart Rosenstein and Jeffrey G. Wyatt, “Outside Directors, Board Independence, and Shareholder Wealth,” Journal of Financial Economics 26 (1990): 175–191.

29. Bang Dang Nguyen and Kasper Meisner Nielsen, “The Value of Independent Directors: Evidence from Sudden Deaths,” Journal of Financial Economics 98 (2010): 550–567.

30. Sanjai Bhagat and Bernard Black, “The Noncorrelation Between Board Independence and Long-Term Firm Performance,” Journal of Corporation Law 27 (2002): 231.

31. Anzhela Knyazeva, Diana Knyazeva, and Ronald W. Masulis, “The Supply of Corporate Directors and Board Independence,” Review of Financial Studies 26 (2013): 1561–1605.

32. Ran Duchin, John G. Matsusaka, and Oguzhan Ozbas, “When Are Outside Directors Effective?” Journal of Financial Economics 96 (2010): 195–214.

33. James F. Cotter, Anil Shivdasani, and Marc Zenner, “Do Independent Directors Enhance Target Shareholder Wealth during Tender Offers?” Journal of Financial Economics 43 (1997): 195–218.

34. John W. Byrd and Kent A. Hickman, “Do Outside Directors Monitor Managers?” Journal of Financial Economics 32 (1992): 195–221.

35. Brian K. Boyd, “Board Control and CEO Compensation,” Strategic Management Journal 15 (1994): 335–344.

36. Sydney Finkelstein and Donald C. Hambrick, “Chief Executive Compensation: A Study of the Intersection of Markets and Political Processes,” Strategic Management Journal 10 (1989): 121–134.

37. NYSE, “Corporate Governance Listing Standards, Listed Company Manual Section 303A.02—Corporate Governance Standards (approved January 11, 2013).”Accessed May 3, 2015. See http://nysemanual.nyse.com/LCMTools/PlatformViewer.asp?selectednode=chp_1_4_3_3&manual=%2Flcm%2Fsections%2Flcm-sections%2F.

38. Marty Lipton makes the following historical observation: “It is interesting to note that it is not at all clear that director independence is the fundamental keystone of ‘good’ corporate governance. The world’s most successful economy was built by companies that had few, if any, independent directors. It was not until 1956 that the NYSE recommended that listed companies have two outside directors, and it wasn’t until 1977 that they were required to have an audit committee of all independent directors.” See Martin Lipton, “Future of the Board of Directors,” paper presented at the Chairman & CEO Peer Forum: Board Leadership in a New Regulatory Environment, New York Stock Exchange (June 23, 2010).

39. Note that the companies with low independence levels have considerable inside ownership or are controlled corporations. Tony Chapelle, “Listed: The Least and Most Independent Boards,” Agenda (January 16, 2015). Accessed January 16, 2015. See http://agendaweek.com/c/1045763/107713/listed_least_most_independent_boards?referrer_module=Twitter&campCode=Twitter.

40. NYSE.

41. Byoung-Hyoun Hwang and Seoyoung Kim, “It Pays to Have Friends,” Journal of Financial Economics 93 (2009): 138–158.

42. Jeffrey L. Coles, Naveen D. Daniel, and Lalitha Naveen, “Co-opted Boards,” Review of Financial Studies 27 (June 2014): 1751–1796.

43. It might be the case that better companies attract more powerful directors. See Kathy Fogel, Liping Ma, and Randall Morck, “Powerful Independent Directors,” European Corporate Governance Institute (ECGI)—Finance 404, Social Science Research Network (2014). Accessed January 22, 2015. See http://ssrn.com/abstract=2377106.

44. Earnings quality is measured using the metric abnormal accruals. Generally, abnormal accruals represent the difference between Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) earnings, which are measured on an accrual basis, and GAAP cash flow, which represents cash generated by the business. When a large discrepancy exists between these two figures during a sustained period of time, the company’s accounting is considered to be lower quality because the company is systematically recording more net income than it is generating on a cash basis. Research has shown that large abnormal accruals are correlated with an increased likelihood of future earnings restatements. This correlation is modest but still significant. Many academic studies that measure accounting quality use abnormal accruals as a measurement. Although not perfect, it is a standard measure that can be applied across firms. See April Klein, “Audit Committee, Board of Director Characteristics, and Earnings Management,” Journal of Accounting and Economics 33 (2002): 375–400.

45. April Klein, “Firm Performance and Board Committee Structure,” Journal of Law and Economics 41 (1998): 275–303.

46. A. Burak Güner, Ulrike Malmendier, and Geoffrey Tate, “Financial Expertise of Directors,” Journal of Financial Economics 88 (2008): 323–354.

47. Ingolf Dittmann, Ernst Maug, and Christoph Schneider, “Bankers on the Boards of German Firms: What They Do, What They Are Worth, and Why They Are (Still) There,” Review of Finance 14 (2010): 35–71. And Randall Morck and Masao Nakamura, “Banks and Corporate Control in Japan,” Journal of Finance 54 (1999): 319–339.

48. David H. Erkens, K. R. Subramanyam, and Jieying Zhang, “Affiliated Banker on Board and Conservative Accounting,” Accounting Review 89 (2014): 1703–1728.

49. Qianqian Huang, Feng Jiang, Erik Lie, and Ke Yang, “The Role of Investment Banker Directors in M&A,” Journal of Financial Economics 112 (2014): 269–286.

50. Sarbanes–Oxley Act of 2002, Section 407(b).

51. Mark L. Defond, Rebecca N. Hann, and Xuesong Hu, “Does the Market Value Financial Expertise on Audit Committees of Boards of Directors?” Journal of Accounting Research 43 (2005): 153–193.

52. Anup Agrawal and Sahiba Chadha, “Corporate Governance and Accounting Scandals,” Journal of Law and Economics 48 (2005): 371–406.