1. Introduction to Corporate Governance

Corporate governance has become a well-discussed and controversial topic in both the popular press and business press. Newspapers produce detailed accounts of corporate fraud, accounting scandals, insider trading, excessive compensation, and other perceived organizational failures—many of which culminate in lawsuits, resignations, and bankruptcy. The stories have run the gamut from the shocking and instructive (epitomized by Enron and the elaborate use of special-purpose entities and aggressive accounting to distort its financial condition) to the shocking and outrageous (epitomized by Tyco partially funding a $2.1 million birthday party in 2002 for the wife of Chief Executive Officer [CEO] Dennis Kozlowski that included a vodka-dispensing replica of the statue David). Central to these stories is the assumption that somehow corporate governance is to blame—that is, the system of checks and balances meant to prevent abuse by executives failed (see the following sidebar).1

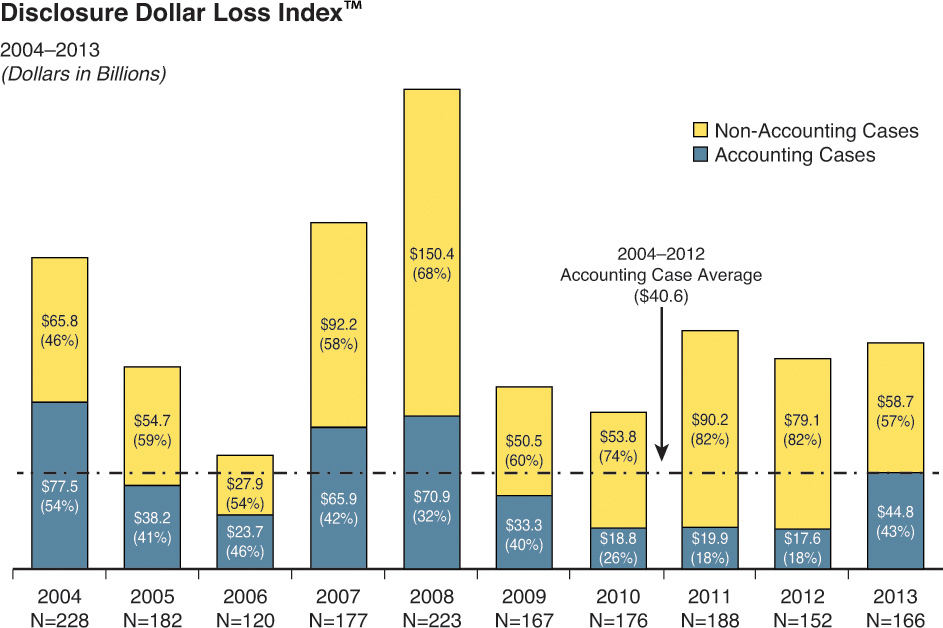

As the case of HealthSouth illustrates, the system of checks and balances meant to prevent abuse by senior executives does not always function properly. Unfortunately, governance failures are not isolated instances. In recent years, several corporations have collapsed in prominent fashion, including American International Group, Bear Stearns, Countrywide Financial, Enron, Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, General Motors, Lehman Brothers, MF Global, and WorldCom. This list does not even include the dozens of lesser-known companies that did not make the front page of the Wall Street Journal or Financial Times but whose owners also suffered. Furthermore, this problem is not limited to U.S. corporations. Major international companies such as Olympus, Parmalat, Petrobras, Royal Bank of Scotland, Royal Dutch Shell, Satyam, and Siemens have all been plagued by scandals involving breakdowns of management oversight. Foreign companies listed on U.S. exchanges are as likely to restate their financial results as domestic companies, indicating that governance is a global issue (see the following sidebar).

Self-Interested Executives

What is the root cause of these failures? Reports suggest that these companies suffered from a “breakdown in corporate governance.” What does that mean? What is corporate governance, and what is it expected to prevent?

In theory, the need for corporate governance rests on the idea that when separation exists between the ownership of a company and its management, self-interested executives have the opportunity to take actions that benefit themselves, with shareholders and stakeholders bearing the cost of these actions.14 This scenario is typically referred to as the agency problem, with the costs resulting from this problem described as agency costs. Executives make investment, financing, and operating decisions that better themselves at the expense of other parties related to the firm.15 To lessen agency costs, some type of control or monitoring system is put in place in the organization. That system of checks and balances is called corporate governance.

Behavioral psychology and other social sciences have provided evidence that individuals are self-interested. In The Economic Approach to Human Behavior, Gary Becker (1976) applies a theory of “rational self-interest” to economics to explain human tendencies, including one to commit crime or fraud.16 He demonstrates that, in a wide variety of settings, individuals can take actions to benefit themselves without detection and, therefore, avoid the cost of punishment. Control mechanisms are put in place in society to deter such behavior by increasing the probability of detection and shifting the risk–reward balance so that the expected payoff from crime is decreased.

Before we rely on this theory too heavily, it is important to highlight that individuals are not always uniformly and completely self-interested. Many people exhibit self-restraint on moral grounds that have little to do with economic rewards. Not all employees who are unobserved in front of an open cash box will steal from it, and not all executives knowingly make decisions that better themselves at the expense of shareholders. This is known as moral salience, the knowledge that certain actions are inherently wrong even if they are undetected and left unpunished. Individuals exhibit varying degrees of moral salience, depending on their personality, religious convictions, and personal and financial circumstances. Moral salience also depends on the company involved, the country of business, and the cultural norms.17

The need for a governance control mechanism to discourage costly, self-interested behavior therefore depends on the size of the potential agency costs, the ability of the control mechanism to mitigate agency costs, and the cost of implementing the control mechanism (see the following sidebar).

Defining Corporate Governance

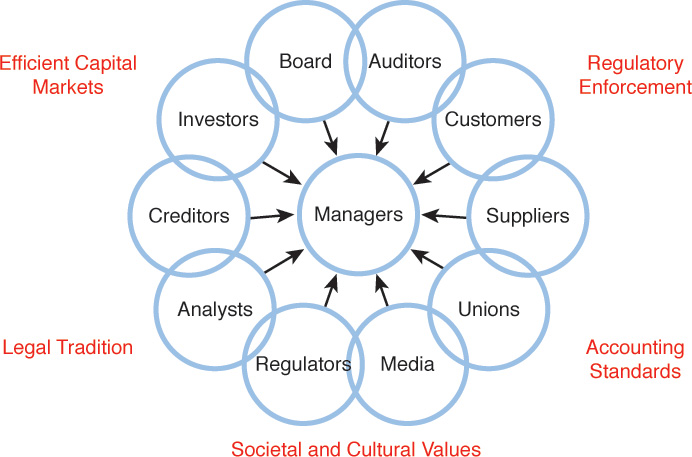

We define corporate governance as the collection of control mechanisms that an organization adopts to prevent or dissuade potentially self-interested managers from engaging in activities detrimental to the welfare of shareholders and stakeholders. At a minimum, the monitoring system consists of a board of directors to oversee management and an external auditor to express an opinion on the reliability of financial statements. In most cases, however, governance systems are influenced by a much broader group of constituents, including owners of the firm, creditors, labor unions, customers, suppliers, investment analysts, the media, and regulators (see Figure 1.3).

Source: Chart prepared by David F. Larcker and Brian Tayan (2011).

Figure 1.3 Selected determinants and participants in corporate governance systems.

For a governance system to be economically efficient, it should decrease agency costs more than the costs of implementation. However, because implementation costs are greater than zero, even the best corporate governance system will not make the cost of the agency problem disappear completely.

The structure of the governance system also depends on the fundamental orientation of the firm and the role that the firm plays in society. From a shareholder perspective (the viewpoint that the primary obligation of the organization is to maximize shareholder value), effective corporate governance should increase the value of equity holders by better aligning incentives between management and shareholders. From a stakeholder perspective (the viewpoint that the organization has a societal obligation beyond increasing shareholder value), effective governance should support policies that produce stable and safe employment, provide an acceptable standard of living to workers, mitigate risk for debt holders, and improve the community and environment.25 Obviously, the governance system that maximizes shareholder value might not be the same as the one that maximizes stakeholder value.

A broad set of external forces that vary across nations also influence the structure of the governance system. These include the efficiency of local capital markets, legal tradition, reliability of accounting standards, regulatory enforcement, and societal and cultural values. These forces serve as an external disciplining mechanism on managerial behavior. Their relative effectiveness determines the extent to which additional monitoring mechanisms are required.

Finally, any system of corporate governance involves third parties that are linked with the company but do not have a direct ownership stake. These include regulators (such as the SEC), politicians, the external auditor, security analysts, external legal counsel, employees and unions, proxy advisory firms, customers, suppliers, and other similar participants. Third parties might be subject to their own agency issues that compromise their ability to work solely in the interest of the company. For example, the external auditor is employed by an accounting firm that seeks to improve its own financial condition; when the accounting firm also provides nonaudit services, the auditor might be confronted with conflicting objectives. Likewise, security analysts are employed by investment firms that serve both institutional and retail clients; when the analyst covers a company that is also a client of the investment firm, the analyst might face added pressure by his firm to publish positive comments about the company that are misleading to shareholders. These types of conflicts can contribute to a breakdown in oversight of management activity.

Corporate Governance Standards

There are no universally agreed-upon standards that determine good governance. Still, this has not stopped blue-ribbon panels from recommending uniform standards to market participants. For example, in December 1992, the Cadbury Committee—commissioned by the accountancy profession and London Stock Exchange “to help raise the standards of corporate governance and the level of confidence in financial reporting and auditing”—issued a Code of Best Practices that, in many ways, provided a benchmark set of recommendations on governance.26 Key recommendations included separating the chairman of the board and chief executive officer titles, appointing independent directors, reducing conflicts of interest at the board level because of business or other relationships, convening an independent audit committee, and reviewing the effectiveness of the company’s internal controls. These standards set the basis for listing requirements on the London Stock Exchange and were largely adopted by the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE). However, compliance with these standards has not always translated into effective governance. For example, Enron was compliant with NYSE requirements, including requirements to have a majority of independent directors and fully independent audit and compensation committees, yet it still failed along many legal and ethical dimensions.

Over time, a series of formal regulations and informal guidelines has been proposed to address perceived shortcomings in governance systems as they are exposed. One of the most important pieces of formal legislation relating to governance is the Sarbanes–Oxley Act of 2002 (SOX). Primarily a reaction to the failures of Enron and others, SOX mandated a series of requirements to improve corporate controls and reduce conflicts of interest. Importantly, CEOs and CFOs found to have made material misrepresentations in the financial statements are now subject to criminal penalties. Despite these efforts, corporate failures stemming from deficient governance systems continue. In 2005, Refco, a large U.S.-based foreign exchange and commodity broker, filed for bankruptcy after revealing that it had hidden $430 million in loans made to its CEO.27 The disclosure came just two months after the firm raised $583 million in an initial public offering. That same year, mortgage guarantor Fannie Mae announced that it had overstated earnings by $6.3 billion because it had misapplied more than 20 accounting standards relating to loans, investment securities, and derivatives. Insufficient capital levels eventually led the company to seek conservatorship by the U.S. government.28

In 2009, Sen. Charles Schumer of New York proposed additional federal legislation to stem the tide of governance collapses. Known as the Shareholder’s Bill of Rights, the proposal stipulated that companies adopt procedural changes designed to give shareholders greater influence over director elections and executive compensation. Requirements included a shift toward annual elections for all directors (thereby disallowing staggered or classified boards), a standard of majority voting for director elections (instead of plurality voting) in which directors in uncontested elections must resign if they do not receive a majority vote, the right for certain institutional shareholders to directly nominate board candidates on the company proxy (proxy access), the separation of the chairman and CEO roles, and the right for shareholders to have an advisory vote on executive compensation (say-on-pay). The 2010 Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act subsequently adopted several of these recommendations, including say-on-pay. The interesting question is whether this legislation was a product of political expediency or based on rigorous theory and empirical research.29

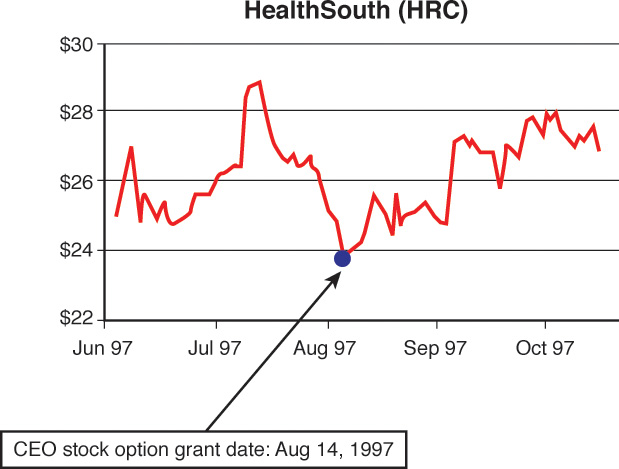

Several third-party organizations, such as GMI Ratings and Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS), attempt to protect investors from inadequate corporate governance by publishing governance ratings on individual companies. These rating agencies use alphanumeric or numeric systems that rank companies according to a set of criteria that they believe measure governance effectiveness. Companies with high ratings are considered less risky and most likely to grow shareholder value. Companies with low ratings are considered more risky and have the highest potential for failure or fraud. However, the accuracy and predictive power of these ratings have not been demonstrated. Critics allege that ratings encourage a “check-the-box” approach to governance that overlooks important context. The potential shortcomings of these ratings were spotlighted in the case of HealthSouth. Before evidence of earnings manipulation was brought to light, the company had an ISS rating that placed it in the top 35 percent of Standard & Poor’s 500 companies and the top 8 percent of its industry peers.30

Changes in the business environment further complicate attempts to identify uniform standards of governance. Some recent trends include the increased prominence of activist investors, private equity firms, and proxy advisory firms in the governance space:

• Activist investors—Institutional investors, hedge funds, and pension funds have become considerably more active in attempting to influence management and the board through public campaigns and the annual proxy voting process. Are the interests of these parties consistent with those of individual shareholders? Does public debate between these parties reflect a movement toward improved dialogue about corporate objectives and strategy? Or does it constitute an unnecessary intrusion by activists who have their own self-interested agendas?

• Private equity firms—Private equity firms implement governance systems that are considerably different from those at most public companies. Publicly owned companies must demonstrate independence at the board level, but private equity–owned companies operate with very low levels of independence (almost everyone on the board has a relationship to the company and has a vested interest in its operations). Private equity companies also offer extremely high compensation to senior executives, a practice that is criticized among public companies but that is strictly tied to the creation of economic value. Should public companies adopt certain aspects from the private equity model of governance? Would this produce more or less shareholder value?

• Proxy advisory firms—Recent SEC rules require that mutual funds disclose how they vote their annual proxies.31 These rules have coincided with increased media attention on the voting process, which was previously considered a formality of little interest. Has the disclosure of voting improved corporate governance? At the same time, these rules have stimulated demand for commercial firms—such as ISS and Glass Lewis—to provide recommendations on how to vote on proxy proposals. What is the impact of shareholders relying on third parties to inform their voting decisions? Are the recommendations of these firms consistent with good governance?32

Best Practice or Best Practices? Does “One Size Fit All”?

It is highly unlikely that a single set of best practices exists for all firms, despite the attempts of some to impose uniform standards. Governance is a complex and dynamic system that involves the interaction of a diverse set of constituents, all of whom play roles in monitoring executive behavior. Because of this complexity, assessing the impact of a single component is difficult. Focusing an analysis on one or two mechanisms without considering the broader context can be a prescription for failure. For example, is it sufficient to insist that a company separate the chairman and CEO positions without considering who the CEO is and other structural, cultural, and governance features of the company?

Applying a “one-size-fits-all” approach to governance can lead to incorrect conclusions and is unlikely to substantially improve corporate performance. The standards most often associated with good governance might appear to be good ideas, but when applied universally, they can result in failure as often as in success. For example, consider the idea of board independence. Is a board consisting primarily of independent directors superior to a board composed entirely of internal directors? How should individual attributes such as business acumen, professional background, ethical standards of responsibility, level of engagement, relationship with the CEO, and reliance on director fees to maintain their standard of living factor into our analysis?33 Personal attributes might influence independence of perspective more than predetermined standards.34 However, these elements are rarely captured in regulatory requirements.35

In governance, context matters. A set of governance mechanisms that works well in one setting might prove disastrous in another. This situation becomes apparent when considering international governance systems. For example, Germany requires labor union representation on many corporate boards. How effective would such a system be in the United States? Japanese boards have few outside directors, and many of those who are outside directors come from banks that provide capital to the firm or key customers and suppliers. What would be the impact on Japanese companies if they were required to adopt the independence standards of the United States? These are difficult questions, but investors must consider them when deciding where to allocate their investment dollars.

Relationship between Corporate Governance and Firm Performance

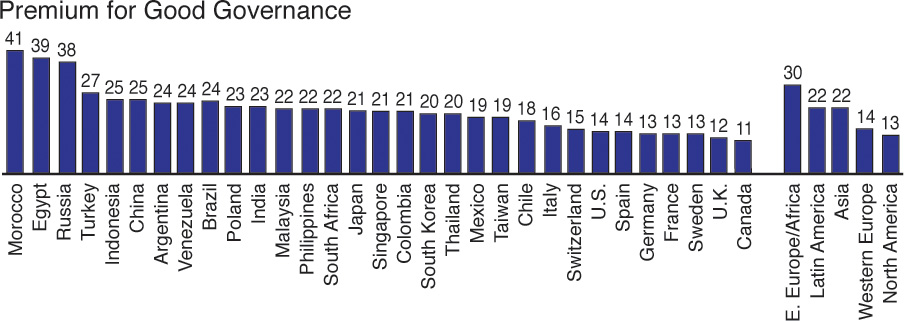

According to a survey by McKinsey & Company, nearly 80 percent of institutional investors responded that they would pay a premium for a well-governed company. The size of the premium varied by market, ranging from 11 percent for a company in Canada to around 40 percent for a company in Morocco, Egypt, or Russia (see Figure 1.4).36

Source: Paul Coombes and Mark Watson, “Global Investor Opinion Survey 2002: Key Findings” McKinsey & Company (2002).

Figure 1.4 Indicated premiums for good corporate governance, by country.

These results imply that investors perceive well-governed companies to be better investments than poorly governed companies.37 However, the extent to which this is true is not entirely clear.

As we will see throughout this book, many studies link measures of corporate governance with firm operating and stock price performance. Perhaps the most widely cited study was done by Gompers, Ishii, and Metrick (2003).38 They found that companies that employ “shareholder-friendly” governance features significantly outperform companies that employ “shareholder unfriendly” governance features. This is an important research study, but as we will see in Chapter 13, “Corporate Governance Ratings,” these results are not definitive. Currently, neither professionals nor researchers have produced a reliable litmus test that measures overall governance quality using a simple common tool.

The purpose of this book is to provide a basis for constructive debate among executives, directors, investors, regulators, and other constituents that have an important stake in the success of corporations. This book focuses on corporate governance from an organizational instead of purely legal perspective, with an emphasis on exploring the relationships between control mechanisms and their impact on mitigating agency costs and improving shareholder and stakeholder outcomes.

Each chapter examines a specific component of corporate governance and summarizes what is known and what remains unknown about the topic. We have taken an agnostic approach, with no agenda other than to “get the story straight.” In each chapter, we provide an overview of the specific topic, a synthesis of the relevant research, and concrete examples that illustrate key points.39 Sometimes the evidence is inconclusive (see the following sidebar). We hope that the combination of materials will help you arrive at intelligent insights. In particular, we hope to benefit the individuals who participate in corporate governance processes so that they can make informed decisions that benefit the organizations they serve.

Endnotes

1. Some material in this chapter is adapted from David F. Larcker and Brian Tayan, “Models of Corporate Governance: Who’s the Fairest of Them All?” Stanford GSB Case No. CG 11, January 15, 2008. Accessed April 24, 2015. See http://www.gsb.stanford.edu/faculty-research/case-studies/models-corporate-governance-whos-fairest-them-all.

2. See Aaron Beam and Chris Warner, HealthSouth: The Wagon to Disaster (Fairhope, AL: Wagon Publishing, 2009).

3. Lisa Fingeret Roth, “HealthSouth CFO Admits Fraud Charges,” FT.com (March 26, 2003).

4. HealthSouth Corporation, Form DEF 14A, filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission May 16, 2002.

5. In re: HealthSouth Corporation Bondholder Litigation. United States District Court Northern District of Alabama Southern Division. Master File No. CV-03-BE-1500-S.

6. Chad Terhune and Carrick Mollenkamp, “HealthSouth Officials May Sign Plea Agreements—Moves by Finance Executives Would Likely Help Build Criminal Case against CEO,” Wall Street Journal (March 26, 2003, Eastern edition): A.14.

7. Carrick Mollenkamp, “Some of Scrushy’s Lawyers Ask Others on Team for Money Back,” Wall Street Journal (December 17, 2003, Eastern edition): A.16.

8. HealthSouth Corporation, Form DEF 14A.

9. Dan Ackman, “CEO Compensation for Life?” Forbes.com (April 25, 2002). Accessed November 16, 2010. www.forbes.com/2002/04/25/0425ceotenure.html.

10. HealthSouth Corporation, Form DEF 14A. See also Jonathan Weil and Cassell Bryan-Low, “Questioning the Books: Audit Committee Met Only Once During 2001,” Wall Street Journal (March 21, 2003, Eastern edition): A.2.

11. HealthSouth Corporation, Form DEF 14A.

12. Ken Brown and Robert Frank, “Analyst’s Bullishness on HealthSouth’s Stock Didn’t Waver,” Wall Street Journal (April 4, 2003, Eastern edition): C.1.

13. Olympus Corporation, “Investigation Report, Third Party Committee” (December 6, 2011). Accessed April 24, 2015. See http://www.olympus-global.com/en/common/pdf/if111206corpe_2.pdf.

14. This issue was the basis of the classic discussion in Adolph Berle and Gardiner Means, The Modern Corporation and Private Property (New York: Harcourt, Brace, and World, 1932).

15. The phrase rent extraction is another commonly used term for agency costs and refers to economic costs taken out of the system without any corresponding contribution in productivity.

16. Gary Becker, The Economic Approach to Human Behavior (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1976).

17. For example, a study by Boivie, Lange, McDonald, and Westphal found that CEOs who strongly identify with their company are less likely to accept expensive perquisites or make other decisions that are at odds with shareholder interests. See Steven Boivie, Donald Lange, Michael L. McDonald, and James D. Westphal, “Me or We: The Effects of CEO Organizational Identification of Agency Costs,” Academy of Management Proceedings (2009): 1–6.

18. Bankruptcydata.com, “2013 Public Company Bankruptcy Filings Annual Report,” New Generation Research, Inc. (2013). Accessed April 24, 2015. See http://www.bankruptcydata.com/bankruptcyyearinreview_form.htm.

19. Enforcement actions are measured as the number of Accounting and Auditing Enforcement Releases (AAER) by the SEC. The SEC issues an AAER for alleged violations of SEC and federal rules. Academic researchers have used AAER as a proxy for severe fraud because most companies that commit financial statement fraud receive SEC enforcement actions. Deloitte, “Ten Things about Bankruptcy and Fraud: A Review of Bankruptcy Filings,” (2008). Accessed April 24, 2015. See http://bankruptcyfraud.typepad.com/Deloitte_Report.pdf.

20. Susan Scholz, “Financial Restatement Trends in the United States: 2003–2012,” Center for Audit Quality. Accessed April 24, 2015. See http://www.thecaq.org/docs/reports-and-publications/financial-restatement-trends-in-the-united-states-2003-2012.pdf?sfvrsn=2/financial-restatement-trends-in-the-united-states-2003-2012.

21. Gibson Dunn, “2013 Year-End FCPA Update,” (2013). Accessed April 24, 2015. See www.gibsondunn.com/publications/pages/2013-Year-End-FCPA-Update.aspx.

22. John Graham, Campbell Harvey, and Shiva Rajgopal, “Value Destruction and Financial Reporting Decisions,” Financial Analysts Journal 62 (2006): 27–39.

23. I. J. Alexander Dyck, Adair Morse, and Luigi Zingales, “How Pervasive Is Corporate Fraud?” Rotman School of Management Working Paper No. 2222608, Social Science Research Network (2013). Accessed April 24, 2015. See http://ssrn.com/abstract=2222608.

24. Association of Certified Fraud Examiners, “Report to the Nations on Occupational Fraud and Abuse: 2014 Global Fraud Survey” (2014). Accessed March 25, 2015. See http://www.acfe.com/rttn-red-flags.aspx.

25. The cost–benefit assessment of a governance system also depends on whether the company operates under a shareholder-centric or stakeholder-centric model. The fundamentally different orientations of these models makes it difficult for an outside observer to compare their effectiveness. For example, a decision to maximize shareholder value might come at the cost of the employee and environmental objectives of stakeholders, but comparing these costs is not easy. We discuss this more in Chapter 2, “International Corporate Governance.”

26. Cadbury Committee, Report of the Committee on the Financial Aspects of Corporate Governance (London: Gee, 1992).

27. Deborah Solomon, Carrick Mollenkamp, Peter A. McKay, and Jonathan Weil, “Refco’s Debts Started with Several Clients; Bennett Secretly Intervened to Assume Some Obligations; Return of Victor Niederhoffer,” Wall Street Journal (October 21, 2005, Eastern edition): C.1.

28. James R. Hagerty, “Politics & Economics: Fannie Mae Moves toward Resolution with Restatement,” Wall Street Journal (December 7, 2006, Eastern edition) A.4. Damian Paletta, “Fannie Sues KPMG for $2 Billion over Costs of Accounting Issues,” Wall Street Journal (December 13, 2006, Eastern edition): A.16.

29. A study by Larcker, Ormazabal, and Taylor found that the legislative provisions in Schumer and Dodd–Frank are associated with negative stock price returns for affected companies. These results seemed to have little impact on the congressional debate. Similarly, the legislators who drafted the Sarbanes–Oxley Act of 2002 did not take into account research literature. See David F. Larcker, Gaizka Ormazabal, and Daniel J. Taylor, “The Market Reaction to Corporate Governance Regulation,” Journal of Financial Economics 101 (2011): 431–448; and Roberta Romano, “The Sarbanes–Oxley Act and the Making of Quack Corporate Governance,” Yale Law Journal 114 (2005): 1521–1612.

30. Cited in Jeffrey Sonnenfeld, “Good Governance and the Misleading Myths of Bad Metrics,” Academy of Management Executive 18 (2004): 108–113.

31. Legal Information Institute, “17 CFR 270.30b1-4 - Report of proxy voting record,” Cornell University Law School. Accessed April 24, 2015. See https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/17/270.30b1-4. See also “Report of Proxy Voting, Record Disclosure of Proxy Voting Policies, and Proxy Voting Records by Registered Management Investment Companies,” Securities and Exchange Commission: 17 CFR Parts 239, 249, 270, and 274 Release Nos. 33-8188, 34-47304, IC-25922; File No. S7-36-02. Accessed April 24, 2015. See http://www.sec.gov/rules/final/33-8188.htm.

32. See David F. Larcker and Allan L. McCall, “Proxy Advisers Don’t Help Shareholders,” Wall Street Journal (December 9, 2013, Eastern edition), A.17.

33. The NYSE acknowledges this risk. See Chapters 3, “Board of Directors: Duties and Liability,” and 5, “Board of Directors: Structure and Consequences,” for more detailed discussion of board independence.

34. Sonnenfeld (2004) wrote, “At least as important are the human dynamics of boards as social systems where leadership character, individual values, decision-making processes, conflict management, and strategic thinking will truly differentiate a firm’s governance.”

35. Milton Harris and Artur Ravi, “A Theory of Board Control and Size,” Review of Financial Studies 21 (2008): 1797–1831.

36. Paul Coombes and Mark Watson, “Global Investor Opinion Survey 2002: Key Findings,” McKinsey & Co. (2002). Accessed April 2, 2015. See http://www.eiod.org/uploads/Publications/Pdf/II-Rp-4-1.pdf.

37. This is what investors said they would do when asked in a formal survey. However, this study does not provide evidence that investors actually pay this premium when making investment decisions.

38. Paul Gompers, Joy Ishii, and Andrew Metrick, “Corporate Governance and Equity Prices,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 118 (2003): 107–156.

39. We are not attempting to provide a complete and comprehensive review of the research literature. Our goal is to select specific papers that provide a fair reflection of general research results.

40. Emphasis added. Nobel Prize Organization, “Oliver E. Williamson—Interview” (2009). Accessed April 24, 2015. See http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/economics/laureates/2009/williamson-telephone.html.

41. For a discussion of the limitations of Tobin’s Q as a measure of firm performance, see Philip H. Dybvig and Mitch Warachka, “Tobin’s Q Does Not Measure Firm Performance: Theory, Empirics, and Alternative Measures,” Social Science Research Network (March 2015). Accessed April 24, 2015. See http://ssrn.com/abstract=1562444.