7. Labor Market for Executives and CEO Succession Planning

In this chapter, we examine the labor market for executives and the CEO succession process. Corporations have a demand for qualified executives who can manage an organization at the highest level. A supply of individuals exists who have the skills needed to handle these responsibilities. The labor market for chief executives refers to the process by which the available supply is matched with demand. For the labor market to function properly, information must be available on the needs of the corporation and the skills of the individuals applying to serve in executive roles.

The efficiency of this market has important implications on governance quality.1 When it is efficient, the board of directors will have the information it needs to evaluate and price CEO talent. This leads to improved hiring decisions and reasonable compensation packages. It also tends to increase discipline on managerial behavior; that is, when managers know they can lose their jobs for poor performance, they have greater incentive to perform. When this market functions inefficiently, management faces less pressure to perform, and distortions can arise in the balance of power between the CEO and the board or in excessive compensation. Executives can also be matched to the wrong job, causing inefficiencies and loss of shareholder value.2

In this chapter, we start by considering the factors that contribute to CEO turnover and evidence on how likely boards are to terminate underperforming CEOs. Next, we examine the CEO selection process. We then evaluate the manner in which companies plan for and implement succession at the CEO level, including both internal and external candidates.

Labor Market for Chief Executive Officers

A discussion of the labor market for CEOs is relevant in a book about governance for several reasons. First, the chief executive officer is the primary agent responsible for managing the corporation and ensuring that long-term value is preserved and enhanced. The board of directors has a “duty” to make sure that the right person is selected for the job.

Second, if a manager knows that he or she can be replaced for poor performance, self-interested behavior is limited. In this way, the concept of a “market for labor” is similar to the concept of a “market for corporate control” (which we discuss in Chapter 11, “The Market for Corporate Control”). In the market for corporate control, the board must decide whether the company is better off under current ownership or whether it should be sold to a third party that can better manage the assets. In the labor market for chief executives, the board is asked to determine whether it is economically better to retain the current CEO, given his or her performance, or try to replace that individual with someone who may be better suited to the company’s needs. In both cases, the CEO is aware that a failure to perform can lead to loss of employment, through either termination or the sale of the company.

Third, the efficiency of the labor market sets the stage for how much compensation is required to attract and retain a suitable CEO. Ultimately, a matching process takes place between the attributes that the company desires (in terms of skill set, previous experience, risk aversion, and cultural fit), the price the company is willing to pay for these attributes, and the compensation package executives are willing to accept. If these issues are clear and the relevant information is available to all parties, the market has the potential to be efficient. In principle, executives and the board will engage in an arm’s-length negotiation, and the resulting pay levels will be neither too high nor too low.3

However, it is not at all clear that the labor market for CEOs is especially efficient. For starters, executive skill sets can be difficult to evaluate. An executive who performs effectively at one company is not necessarily guaranteed to repeat this performance at another company. Even if the executive has the requisite qualifications, the board needs to control for differences in industry, the operating and financial condition of the previous employer, cultural fit, work style, predilection for risk taking, and competitive drive before it can make a selection. For these reasons, it is difficult to predict in advance whether a candidate will succeed. This contrasts with many other labor markets, such as those for accountants or factory workers, in which the skills of an employee are more readily identifiable and easier to transfer across companies.

In addition, the efficiency of the CEO labor market is limited by its size and by the ability of executives to move among companies. A job opening for a sales manager might attract hundreds of applicants, dozens of whom have the requisite skills and are willing to consider an offer. If the company’s preferred candidate turns down an offer for salary reasons, the company can either increase its offer or make an offer to a second- or third-choice candidate. Contrast this with the search for the head of a publicly traded multinational corporation, such as IBM. How many executives were capable of managing IBM when Lou Gerstner was brought in to turn the company around in 1993? Some executive recruiters have speculated that the number might have been no more than 10.4 Regardless of whether this estimate is accurate, the limited size and liquidity of the labor market clearly influences the CEO recruitment process (see the following sidebar).

The efficiency of the labor market is also limited by a lack of uniformity among corporate circumstances and practices. Some companies are looking to develop and promote talent from within; others are looking to bring in an outsider as a catalyst for needed change. If the company is in crisis, an emergency CEO might be required to serve on an interim basis while a long-term successor is groomed. The CEO being replaced may be one who has suddenly died, been forced out for underperformance, or been long scheduled to step down on a specific retirement date. In all these situations, the board is charged with finding a successor; however, the number and quality of candidates available may vary, thereby limiting the company’s options. Nickerson (2013) estimated that labor market inefficiencies cost the average company 4.8 percent of its market cap when hiring a new CEO.6

Labor Pool of CEO Talent

The United States has approximately 5,000 CEOs of publicly traded companies.7 According to data from The Conference Board, the average CEO serves in that role between 7 and 10 years (see Figure 7.1).8

Source: The Conference Board, CEO Succession Practices (2014).

Figure 7.1 Departing CEO Tenure (2000–2013).

In terms of experiential background, no standard career path to becoming a CEO exists. According to one study, 22 percent of the CEOs of large U.S. corporations had a background in finance, 20 percent in operations, 20 percent in marketing, 5 percent in engineering, 5 percent in law, 4 percent in consulting, and 6 percent in “other.”9 Only a third of U.S. CEOs have international experience.10

In terms of educational background, 21 percent of CEOs earned an undergraduate degree in engineering, 15 percent in economics, 13 percent in business administration, 8 percent in accounting, and 8 percent in liberal arts. The most commonly attended undergraduate institutions are Harvard, Princeton, Stanford, University of Texas, and University of Wisconsin. Just less than half have a master’s degree in business administration. Only a small fraction of CEOs have military experience.11 Based on interview data, executive recruiters believe that educational background is an important indicator of an individual’s ability to deal with the higher levels of complexity and decision making that are required as the head of a corporation. They also believe that personal attributes, such as whether a candidate played team sports in college or whether he or she was the oldest child—are indicative of an individual’s leadership ability. (Of course, it is not clear whether these attributes translate into better performance.) Still, primary emphasis is placed on the executive’s professional track record and management style.

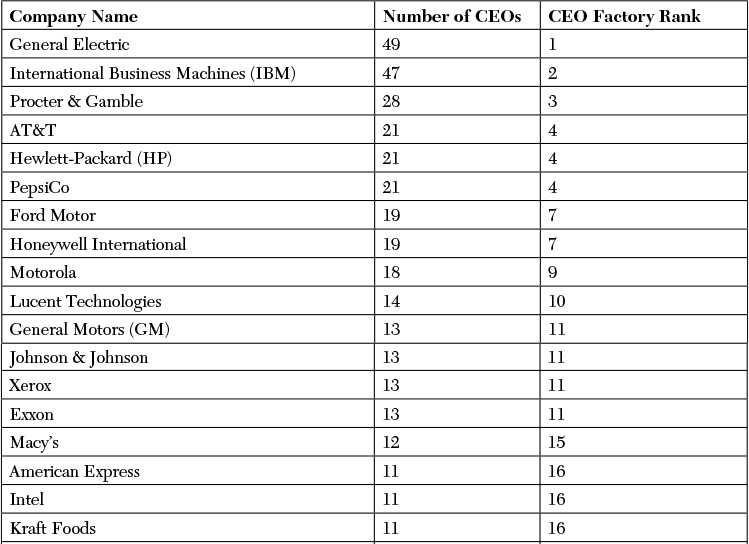

Some evidence exists that personal and professional experience are related to the future performance of a CEO. Cai, Sevilir, and Yang (2014) examined the employment history of CEOs at large U.S. corporations between 1992 and 2010 and found that a disproportionate number (20.5 percent) had previous work experience at a small number of high-profile companies, which the authors describe as “CEO factory firms” (see Table 7.1). They found that the market reacts favorably to the recruitment of CEOs from these firms. They also found that companies that recruit a CEO from these firms exhibit better long-term operating performance and award these executives higher compensation.12

Similarly, Falato, Li, and Milbourn (2012) found that the compensation of newly appointed CEOs is correlated with the executive’s credentials (reputation with the media, age, and education) and that these credentials are positively associated with long-term firm performance.13

Finally, Kaplan, Klebanov, and Sorensen (2012) examined a set of 30 attributes relating to CEO interpersonal, leadership, and work-related skills. They found some evidence that attributes having to do with work style (such as speed, aggressiveness, persistence, work ethic, and high standards) are more predictive of subsequent performance as CEO than interpersonal skills (such as listening skills, teamwork, integrity, and openness to criticism). Still, they caution that research related to CEO characteristics has limitations and that “the generality of our results remains an open empirical question.”14

CEO Turnover

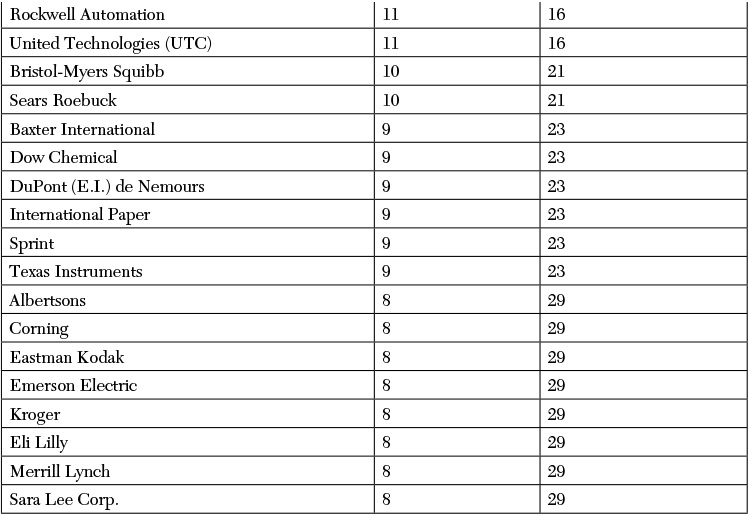

A CEO may leave the position for a variety of reasons, including retirement, recruitment to another firm, dismissal for poor performance, or departure following a corporate takeover. In 2013, CEO turnover was 14.4 percent on a worldwide basis. Over the last decade, this figure has fluctuated between 9 percent and 15 percent (see Figure 7.2).15

Source: Favaro, Karlsson, and Neilson (2014). Reprinted with permission from PwC Strategy & LLC. © 2014 PwC. All rights reserved.

Figure 7.2 CEO turnover rate, 2000–2013.

Extensive research has examined the relationship between CEO turnover and performance.16 Studies show that CEO turnover is inversely proportional to corporate operating and stock price performance.17 That is, CEOs of companies that are not performing well are more likely to step down than CEOs of companies that are performing well. We would expect this from a labor market that rewards success and punishes failure. However, the literature also finds that CEO termination is not especially sensitive to performance. Some CEOs are unlikely to be terminated no matter how poorly they perform.18

This point is clearly illustrated in a study by Huson, Parrino, and Starks (2001). The authors grouped companies into quartiles based on their operating performance during rolling five-year periods. They then compared the frequency of forced CEO turnover (terminations) across quartiles. They found that, although considerable disparity in operating performance exists between the top and bottom quartiles, termination rates are not materially different. For example, during the measurement period 1983–1988, companies in the bottom quartile realized an average annual return on assets (ROA) of –3.7 percent, while companies in the highest quartile realized an average ROA of 12.0 percent, a difference of almost 16 percentage points. Still, the termination rate in the lowest quartile was a meager 2.7 percent per year, versus 0.8 percent in the highest quartile. That is, the probability of the CEO being terminated increased by only 2 percentage points, even though the lowest quartile delivered significantly worse profitability. Results were similar in different measurement periods and when companies were grouped by stock market returns.19

For our purposes, this study suggests that labor market forces are not always effective in removing senior-level executives. Although the probabilities are correlated with performance, they remain very low. Other studies have produced similar findings. A study by Booz & Co. found that even though companies in the lowest decile in terms of stock returns underperform their industry peers by 45 percentage points over a two-year period, the probability that the CEO is forced to resign increases by only 5.7 percent. Booz & Co. concluded that despite corporate governance getting “better” over time, little change has occurred in the sensitivity of termination to performance.20

More recent research by Jenter and Lewellen (2014) found greater sensitivity between performance and forced termination. The authors found that 59 percent of CEOs who perform in the bottom quintile over their first five years are terminated, whereas 17 percent of those in the top quintile are terminated. The difference is even greater for “higher-quality” boards (defined as smaller boards with fewer insiders and higher stock ownership among directors). These findings differ from those of previous studies because Jenter and Lewellen measured CEO-specific relative performance over a longer time period and had a more refined measure of involuntary turnovers.21

Similarly, a proprietary survey by one of the authors found that 50 percent of professional executives and board members say they would terminate a CEO after four quarters of poor earnings performance. “Poor earnings performance” is defined as failure to meet internal and analyst forecasts for quarterly earnings. More than 90 percent say they would terminate a CEO after eight quarters of poor results. This data also suggests that termination is perhaps more closely related to performance than in some of the studies cited earlier.22

Furthermore, evidence suggests that companies with strong governance systems are more likely to terminate an underperforming CEO. Mobbs (2013) found that companies with a credible CEO replacement on the board are more likely to force turnover following poor performance.23 Fich and Shivdasani (2006) found that busy boards (boards on which a majority of outside directors serve on three or more boards and presumably do not have the time to be an effective monitor for shareholders) are significantly less likely to force CEO turnover following a period of underperformance than are boards that are not busy.24 This is consistent with evidence that we saw in Chapter 5, “Board of Directors: Structure and Consequences,” that busy boards are less attentive to corporate performance than are boards whose directors have fewer outside responsibilities.

Studies have also found that companies with a high percentage of outside directors, companies whose directors own a large percentage of shares, and companies whose shareholder base is concentrated among a handful of institutional investors are all more likely to terminate an underperforming CEO. This is consistent with a theory that independent oversight reduces agency costs and management entrenchment. Companies with lower-quality governance tend to “hold on” to underperforming CEOs too long. Strong oversight (by either the board or shareholders) is critical to holding CEOs accountable for company performance. Conversely, companies whose managers own a significant percentage of equity and companies whose CEO is a founding family member are less likely to see their chief executive terminated.25

As we would expect from even modestly efficient capital and labor markets, shareholders react positively to news that an underperforming CEO has been terminated and replaced by an outside successor. Huson, Parrino, and Starks (2001) found excess stock returns of 2 to 7 percent following such announcements.26

Newly Appointed CEOs

Most newly appointed CEOs are internal executives. According to The Conference Board, between 70 and 80 percent of successions involve an internal replacement.27 A variety of reasons explain why shareholders and stakeholders might prefer an insider. Internal executives are familiar with the company, and the board has the opportunity to evaluate their performance, leadership style, and cultural fit on a firsthand basis, giving them greater confidence that the executives will perform to expectations. Insiders bring continuity, which, if the company has been successful, can lead to a smooth transition and less disruption to operations and staffing. For this reason, well-managed companies invest in developing internal talent so that key positions can be filled following unexpected departures.

An external successor might be preferable under other circumstances. The board might be dissatisfied with recent performance or decide that the company needs to change direction. The company might lack insiders with sufficient talent or might prefer an outsider with unique experience (such as one who has successfully navigated an operational turnaround, financial restructuring, regulatory investigation, or international expansion), given the current state of the company. Because an outsider is not wedded to the company’s current mode of operations or to its existing management team, an executive from outside the company might be more effective in bringing change.

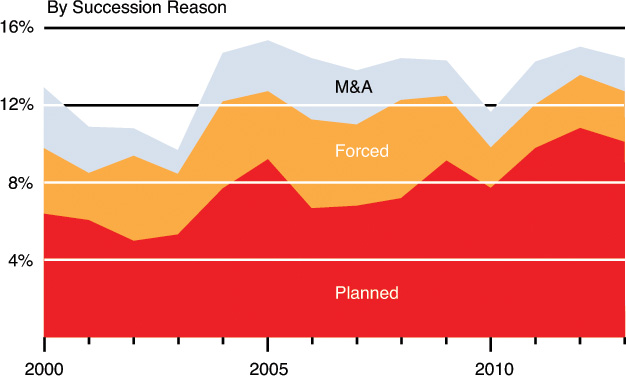

The decision to recruit an external candidate, however, generally comes at a cost. According to Equilar, external CEOs receive first-year total compensation that is approximately 35 percent higher (median average) than that given to internal candidates.28 This differential is fairly consistent across companies by market capitalization sizes (see Figure 7.3). Part of the premium comes from the fact that external candidates tend to have proven experience as CEO, whereas internal candidates are promoted to the position for the first time. Furthermore, companies that recruit a candidate from the outside tend to be in financial trouble. Therefore, these executives require some sort of “risk premium” to take on a job that involves a higher chance of failure. Finally, external candidates must be bought out of existing employment agreements. This involves making them whole for unvested, in-the-money options, the value of which can be quite substantial. For example, when Target recruited Brian Cornell to be CEO in 2014, it offered equity incentives worth almost $20 million, partly to compensate him for options forfeited at his former employer, PepsiCo.29

Source: Equilar Inc., “Paying the New Boss: Compensation Analysis for Newly Hired CEOs” (June 2013). Equilar is an executive compensation and corporate governance data firm.

Figure 7.3 CEO median total compensation ($MM).

The trend of looking outside the company for a CEO has increased in recent years. Murphy (1999) found that only 8.3 percent of new CEOs at S&P 500 companies were outsiders during the 1970s. By the 1990s, that figure had risen to 18.9 percent.30 Studies have also shown that the likelihood of appointing an external successor is inversely related to firm performance. Parrino (1997) found that approximately half of all CEOs who were forced to resign for performance reasons were replaced by an outsider, compared with only 10 percent of CEOs who voluntarily resigned or retired.31

Despite the promise that an outside CEO brings to many companies, considerable evidence indicates that external CEOs perform worse than internal CEOs. For example, a 2010 study by Booz & Co. found that internal CEOs delivered superior market-adjusted returns in 7 out of the previous 10 years.32 Huson, Malatesta, and Parrino (2004) found improvements in operating performance (measured as ROA) following forced termination but only mixed evidence that stock price improved.33 However, results from these studies could be confounded by the fact that companies that require external CEOs tend to be in worse financial condition. Nevertheless, it is possible that either the practice of recruiting external candidates or the process itself is at least partly responsible for poor subsequent performance.

Models of CEO Succession

Broadly speaking, four general models of CEO succession exist:34

• External candidate

• President and/or COO

• Horse race

• Inside–outside model

External Candidate

The first model involves recruiting an external candidate. As discussed earlier, an external candidate is preferable when a company lacks sufficient internal candidates. Unlike internal executives, candidates recruited from the outside tend to have proven experience in the CEO role, thereby reducing the risk that they are unprepared for the responsibility. Also, because external executives are not involved in the decisions of their predecessors, they may have more freedom in making strategic, operational, or cultural changes to the firm. However, external candidates carry significant risk. Even though they are proven in terms of their ability to handle CEO-level responsibilities, they are not proven in terms of organizational fit. The work style that was successful in their previous environment might not necessarily translate well to another (see the following sidebar). External candidates are also more expensive because they need to be bought out of an existing employment contract. External candidates have greater bargaining power to negotiate compensation when they have no viable internal candidates to compete against.

President and/or Chief Operating Officer

The second model of CEO succession is promoting a leading candidate to the position of president and/or chief operating officer (COO), where the executive can be groomed for eventual succession (see the following sidebar). This approach allows a company to observe how an executive performs when given CEO-level responsibility without having to first promote that individual. In addition, it gives the executive experience interacting with the board, analysts, the press, and shareholders—constituents to whom he or she may not previously have had exposure. Because no standard set of responsibilities is associated with the COO role, the scope of the position can be customized to meet the needs of the company. In this way, the executive can be specifically tasked with overseeing a firmwide initiative—such as product launch, international expansion, or restructuring—or trained to overcome a weakness or shortcoming. If he or she is successful, the executive can then be promoted.

At the same time, using a COO appointment in the succession process involves risks. Because it is not a standard role, the responsibilities of the position need to be well defined up front and clearly differentiated from those of the CEO. If not, decision making can suffer. Furthermore, the COO role adds structural and cultural complexity to the organization. If the direct reports of both the CEO and the COO do not clearly understand and support the leadership model of the company, internal divisions can form that undermine the success of the COO. Finally, a clear timeline for succession needs to be established. If the COO remains in the position too long, he or she may become perceived as a “lifetime COO” and lose the internal and external support needed to win promotion.

Horse Race

The third model of CEO succession is the horse race. This model was famously used at General Electric to determine the successor to CEO Jack Welch in 2001, and it has subsequently been used at companies including GlaxoSmithKline, Johnson & Johnson, Microsoft, and Procter & Gamble. In a horse race, two or more internal candidates are promoted to high-level operating positions, where they formally compete to become the next CEO. Each is given a development plan to improve specific skills. Progress is measured over a specified period, with evaluations and feedback provided at predetermined milestones. At the end of the evaluation period, a winner is selected.

As with a COO appointment, a horse race allows the board to test primary candidates before granting a promotion. With this model, however, the board is not committing to a preferred successor in advance. Instead, the board has time to build consensus around a favorite.

The horse-race model also has drawbacks. Horse races tend to be highly public and bring unwanted media attention. They create a politicized atmosphere, in which board members, senior executives, and the CEO jockey to position their favored candidate to win. As such, they can be distracting to management and the organization. In addition, a horse race risks the precipitation of a talent drain. Losers of the race often leave because they do not want to report to the person they lost to and because they feel their only legitimate chance of becoming a CEO is with another company.41

Inside–Outside Model

In an inside–outside model, the company develops a forward-looking profile that lays out the skills and experiences required of the next CEO, based on the future needs of the company. Internal candidates are selected based on their potential fit with this profile. Each is given a preliminary assessment, and areas for development are identified. The candidates are then rotated into new positions where they can develop the skills and experiences needed to fill any gaps in their background. The inside–outside model is different from a horse race: While the internal evaluation is under way, the company identifies promising external candidates, who are also compared against their fit with the CEO profile. If an external candidate is demonstrably better, he or she is recruited to be CEO. If no external candidate is deemed demonstrably better, the leading internal candidate is selected. An external validation is useful in assuring the board that it is selecting the best CEO out of the entire labor market.

The inside–outside model neutralizes certain inefficiencies in the succession process. It levels the playing field between internal and external candidates. Interview data suggests that in many companies, board members are biased against internal executives because they first became acquainted with them in more junior roles and still think of them in a junior capacity. Board members do not have this bias against external candidates, even though external candidates have developed along similar career paths. The inside–outside model reduces this risk by giving the board significant exposure to internal candidates, where their leadership skills can be fully appreciated before they are compared to the external market. Experts recommend that an external candidate be selected only if he or she is 1.5 to 2 times better than the leading internal candidate.42

The risk of using the inside–outside model is that it requires significant planning and oversight. A common mistake occurs when the board lets the external process go on too long. When this occurs, internal candidates may feel that they are not the top choice, even if ultimately selected. This leads to an erosion of trust that affects the working relationship between the board and the new CEO well beyond the transition date.

The Succession Process

The succession-planning process relies on the full engagement of both the board of directors and senior management of the company. As a best practice, succession planning is an ongoing activity and includes preparation for both scheduled and unscheduled transitions. The most critical element of this is the continued development of internal talent. At any time, the company maintains a list of candidates that it can turn to in an emergency. It also maintains a list of primary candidates in line to replace the CEO in a planned succession.

At 37 percent of companies, the full board of directors has primary responsibility for succession; at 31 percent of companies, succession is the responsibility of the nominating and governance committee. Twenty percent of companies assign this duty to the chairman or lead director, and 11 percent of companies look to the CEO for this responsibility.43

When a succession event is scheduled, the board might choose to convene an ad hoc committee specifically tasked with handling the process. This committee is generally chaired by the most senior independent director. Experts recommend that directors be selected based on their qualifications and engagement rather than their availability. Qualified directors have overseen a succession or have participated in one as a CEO.44 Because the new CEO will ultimately be selected by a vote of the full board, however, committee meetings should be open to all interested directors (see the following sidebar).

The outgoing CEO also plays an important role in the succession process. The CEO is responsible for developing talent, in the form of coaching and mentoring, and for assigning executives to areas of the organization where they can be challenged to learn new skills. This includes both job rotations and project-based work. Despite the important role the CEO plays, it is important that the board maintain primary control over the process because the board is responsible for its eventual success. This includes making sure that the CEO does not disrupt or influence the objectivity of the evaluation by advocating on behalf of a favored candidate or undermining a disfavored candidate (see the following sidebar).

The next step in the succession process is to create a skills-and-experience profile. This profile is based on a forward-looking view of the company. If the future needs of the company are different from its present ones, the profile of the next CEO will be quite different from that of the outgoing CEO. The skills-and-experience profile is rooted in the company’s strategy. The board identifies the attributes in terms of professional background and personal qualities required to successfully execute the strategy and achieve organizational objectives. The profile is used as a yardstick against which both internal and external candidates are benchmarked. In the case of long-term succession planning, the progress of internal candidates is measured over time. When it comes time for a succession event, either scheduled or unscheduled, the board will have a list of viable candidates, ranked in order of preference.48

After a new CEO has been selected and approved by a vote of the full board, the transition begins. Interviews with boards and search consultants indicate that transitions can be improved through open and honest dialogue between the CEO-elect and the board. Topics of discussion include how management and the board should interact on an ongoing basis, what each party expects from the other, the requirements for communication, what each party liked and did not like about the previous management, and how the board can support the CEO during both the transition and the tenure. This type of on-boarding activity builds trust and transparency and lays the groundwork for a constructive relationship. The CEO-elect may also choose to improve his or her skills by engaging in coaching by a third-party professional. This allows him or her to collect additional feedback on leadership style and learn to correct behaviors that are not working. Finally, the outgoing CEO can facilitate the transition by remaining behind the scenes but accessible to the new CEO to answer questions that arise.

Interviews suggest that retaining ties to the former CEO is beneficial to the firm. This can be achieved either by inviting the departing CEO to serve (or remain) on the board or by establishing a consulting relationship. Such connections can be beneficial for two reasons. First, the outgoing CEO has unique insight into the firm that can improve the monitoring and advising functions of the boards. Second, extending ties to the outgoing CEO gives that person less incentive to take actions that boost short-term results at the expense of long-term performance in the months prior to departure. At the same time, companies face a risk that the outgoing CEO will exploit a position with the firm to extract agency costs (such as excessive perquisites) without providing substantive value to the firm.

Evans, Nagarajan, and Schloetzer (2010) found that 36 percent of companies invite the outgoing CEO to remain as director.49 The study found that companies are more likely to retain the outgoing CEO as director when he or she retires voluntarily, is a founder or founding family member, or is succeeded by an insider without CEO experience. The company is also more likely to retain the outgoing CEO if the company has had strong stock price performance in the periods preceding the CEO transition.50 (The performance implications of retaining a nonfounder CEO on the board are discussed more fully in Chapter 4, “Board of Directors: Selection, Compensation, and Removal.”)

How Well Are Boards Doing with Succession Planning?

A survey by Heidrick & Struggles and the Rock Center for Corporate Governance at Stanford University took an inside look at CEO succession planning. Based on a sample of directors and CEOs at 140 public and private companies, the survey found a surprising lack of preparedness when it comes to succession. Only 51 percent of respondents reported that their company could name a permanent successor if called upon to do so immediately. A full 39 percent of respondents claimed to have zero viable internal candidates. Instead, respondents expected that it would take 90 days, on average, to find a permanent CEO. This raises serious questions about the attention boards are paying to this critical oversight responsibility.51

The shortcomings appear to stem from a lack of focus. On average, boards spend only two hours per year on succession planning. At most companies, the emphasis appears to be on planning for an emergency but not a permanent successor. A full 70 percent of companies have identified an emergency candidate to serve as CEO on an interim basis if the current CEO needed to be replaced immediately; however, the majority (68 percent) reported that the emergency candidate is not a candidate for the permanent position (see the following sidebar).

Ballinger and Marcel (2010) studied the practice of appointing an emergency—or interim—CEO. They found that it is negatively associated with firm performance and increases a company’s long-term risk of failure, particularly when someone other than the chairman is appointed to the interim position. They conclude that “the use of an interim CEO during successions is an inferior post hoc fix to succession planning processes that boards of directors should avoid.”52

Survey data also suggests that companies fall short on internal talent development. According to the survey cited above, only 58 percent of companies rotate internal candidates into new positions to test their skills and further their growth as part of the grooming process, and only half provide the new CEO with support during the on-boarding and transition process.54 A separate study found that deficiencies in internal talent development extend to the board level. According to The Conference Board, the Institute for Executive Development, and the Rock Center for Corporate Governance at Stanford University (2014), only 55 percent of directors understand the strengths and weaknesses of the senior executive team “extremely well” or “very well.” Fewer than a quarter of directors (23 percent) formally participate in senior executive performance reviews, and only 7 percent act as a professional mentors to these individuals. Without more regular exposure, it is difficult for the board to fully appreciate the leadership potential of internal candidates.55

As these data indicate, many boards do not engage in rigorous succession planning. Instead, succession planning appears often to consist merely of “names in a box,” aimed to satisfy compliance requirements but insufficient to handle an inevitable change in senior management. This may explain why so many companies seem ill-prepared when a CEO suddenly steps down. Succession planning would be improved if it were treated instead as an important element of risk management, with potential disruptions to the organization minimized by ensuring that internal talent is always being developed and external talent identified to manage the company in case of a sudden transition (see the following sidebar).

The External Search Process

Approximately 10 to 20 successful external searches for a new CEO take place among Fortune 500 companies each year. In most of these searches, the board of directors hires a third-party recruiter. The need for an external search indicates that either these companies did not have sufficient internal talent development programs in place to groom a successor, the boards felt their companies required an external candidate to bring about change, or simply the use of an external expert was a necessary part of the due diligence process for selecting a CEO.

The external search market in the United States is characterized by significant concentration. Two firms handle the vast majority of external searches: Heidrick & Struggles and Spencer Stuart. Furthermore, searches are concentrated among just a few influential consultants within these firms.

Potential benefits come from a system dominated by a few well-connected search firms and consultants. Well-connected individuals can efficiently assemble information about the needs and capabilities of a vast number of companies and executives. Through their social and professional networks, they gain access to qualitative information about an executive’s reputation and potential cultural fit with various firms. This information can be critical to understanding how an executive’s proven track record and operation skills will translate into a different environment.

At the same time, market concentration has potential shortcomings. By relying on a select group of recruiters, companies could be limiting the size of the candidate pool. Despite the extensive networks of certain recruiters, experienced talent could be excluded while an established set of executives is recycled among firms. Stated another way, lack of competition among search firms may limit the competition among executives for CEO positions. Other potential shortcomings of the external search market include the following:

• The search consultant may have excessive influence over the selection of candidates. Although directors and other senior executives are invited to nominate qualified external candidates, the search consultant tends to determine who is identified and contacted.

• The search consultant is given considerable responsibility for assessing the pool of candidates and reducing it to a group of finalists. Board members generally do not participate in preliminary interviews, which are handled by the consultant.

• The board might not see enough finalists to make an informed decision. Typically, only three or four finalists are brought before the board committee for in-person interviews (and sometimes only one candidate is). The board tends to make a decision after a handful of interviews, each lasting a few hours. Members of the senior management team are generally not invited to interview the finalists, and interaction with the broader team is not assessed to determine fit.

• The process for determining fair compensation might not be efficient. The search consultant (sometimes in conjunction with the candidate’s personal compensation consultant or lawyer) provides input to the company regarding the necessary compensation for the deal to be consummated. Third parties might have a conflict of interest in negotiating compensation if their own compensation is expressed as a percentage of the CEO-elect’s first-year compensation. Furthermore, both sides know that once a preferred candidate is identified, the board is unlikely to let the deal fall apart for salary reasons, given how time-intensive the search process is.

Despite these concerns, some research evidence suggests that third-party consultants contribute positively to the recruitment process. Rajgopal, Taylor, and Venkatachalam (2012) found a positive association between the use of third-party consultants and the future operating and stock price performance of the hiring firm. The authors found that third-party intermediaries negotiate significantly higher compensation on behalf of clients but that these pay packages have higher equity-based components and are justified based on subsequent performance. They conclude that “skilled CEOs retain talent agents to signal their skill and [their higher pay] is not consistent with rent extraction.”60

Endnotes

1. We loosely define an efficient labor market as one in which the right candidates are recruited into the right positions at the right compensation levels.

2. One method for estimating the efficiency of labor markets is to look at stock price performance following the unexpected death of a CEO. If the “right” executive is in the CEO position, the stock price should go down following an unexpected death. If the “wrong” executive is in the CEO position, the stock price should go up. Johnson, Magee, Nagarajan, and Newman (1985) found no uniform pattern across a sample of sudden deaths but did find evidence that inappropriate appointments might take place at the company-specific level. Salas (2010) found similar results. See W. Bruce Johnson, Robert P. Magee, Nandu J. Nagarajan, and Harry A. Newman, “An Analysis of the Stock-Price Reaction to Sudden Executive Deaths—Implications for the Managerial Labor Market,” Journal of Accounting and Economics 7 (1985): 151–174. And Jesus M. Salas, “Entrenchment, Governance, and the Stock Price Reaction to Sudden Executive Deaths,” Journal of Banking and Finance 34 (2010): 656–666.

3. Third-party agents are often involved in contract negotiations, which can distort the size and structure of compensation packages. Rajgopal, Taylor, and Venkatachalam (2012) found that CEOs who use a third-party agent receive first-year compensation that is significantly higher ($10 million) than those who do not. The study found that CEOs who use such agents tend to deliver superior operating and stock price performance, suggesting that premium compensation could be merited. See Shivaram Rajgopal, Daniel Taylor, and Mohan Venkatachalam, “Frictions in the CEO Labor Market: The Role of Talent Agents in CEO Compensation?” Contemporary Accounting Research 29 (2012): 119–151.

4. Interviews by the authors with executive recruiters, September 2008; proprietary data.

5. Rik Kirkland, Doris Burke, and Telis Demos, “Private Money,” Fortune 155 (2007): 50–60.

6. Jordan Nickerson, “A Structural Estimation of the Cost of Suboptimal Matching in the CEO Labor Market,” Social Science Research Network (November 18, 2013). Accessed February 10, 2015. See http://ssrn.com//abstract=2356680.

7. Based on listings of companies trading on the NYSE (1,800) and NASDAQ (3,100). See NYSE, “NYSE Composite Index.” Accessed May 5, 2015. See http://www1.nyse.com/about/listed/nya_characteristics.shtml. And NASDAQ, “Get the Facts.” Accessed May 5, 2015. See http://www.nasdaq.com/reference/market_facts.stm.

8. Jason D. Schloetzer, Matteo Tonello, and Melissa Aguilar, “CEO Succession Practices 2014 Edition,” The Conference Board (2014). Accessed June 3, 2014. See https://www.conference-board.org/publications/publicationdetail.cfm?publicationid=2731.

9. Burak Koyuncu, Shainaz Firfiray, Björn Claes, and Monika Hamori, “CEOs with a Functional Background in Operations: Reviewing Their Performance and Prevalence in the Top Post,” Human Resource Management 49 (2010): 869–882.

10. Meghan Felicelli, “Route to the Top,” Spencer Stuart (November 1, 2007). Accessed April 6, 2015. See http://content.spencerstuart.com/sswebsite/pdf/lib/Final_Summary_for_2008_publication.pdf.

11. Ibid. See also Efraim Benmelech and Carola Frydman, “Military CEOs,” Journal of Financial Economics, available online 10 May 2014. See http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0304405X14000932.

12. Ye Cai, Merih Sevilir, and Jun Yang, “Are They Different? CEOs Made in CEO Factories,” Kelley School of Business Research Paper No. 15-13, Social Science Research Network (2014). Accessed February 10, 2015. See http://ssrn.com/abstract_id=2549305.

13. Antonio Falato, Dan Li, and Todd T. Milbourn, “CEO Pay and the Market for CEOs,” Feds Working Paper No. 2012-39, Social Science Research Network (2012). Accessed February 16, 2015. See http://ssrn.com/abstract=2191192.

14. Steven N. Kaplan, Mark M. Klebanov, and Morten Sorensen, “Which CEO Characteristics and Abilities Matter?” Journal of Finance 67 (2012): 973–1007.

15. The sample included CEOs of the 2,500 largest publicly traded companies globally. See Ken Favaro, Per-Ola Karlsson, and Gary L. Neilson, “The Lives and Times of the CEO,” strategy+business 75 (2014). Accessed January 28, 2015. See http://www.strategy-business.com/article/00254?pg=all.

16. James A. Brickley, “Empirical Research on CEO Turnover and Firm Performance: A Discussion,” Journal of Accounting and Economics 36 (2003): 227–233.

17. Srinivasan (2005) found that more than half of CEOs step down following a restatement that requires the company to reduce net income. Similarly, Arthaud-Day, Certo, Dalton, and Dalton (2006) found that CEOs are almost twice as likely to be terminated in the two years following a major financial restatement; CFOs are almost 80 percent more likely to be terminated. See Suraj Srinivasan, “Consequences of Financial Reporting Failure for Outside Directors: Evidence from Accounting Restatements and Audit Committee Members,” Journal of Accounting Research 43 (2005): 291–334. And Marne L. Arthaud-Day, S. Trevis Certo, Catherine M. Dalton, and Dan R. Dalton, “A Changing of the Guard: Executive and Director Turnover Following Corporate Financial Restatements,” Academy of Management Journal 49 (2006): 1119–1136.

18. It is difficult to determine from public sources whether a CEO has been terminated or has voluntarily resigned. Most public announcements refer to CEO departures as retirements, and some “educated guesses” are needed to determine whether a departure was involuntary.

19. Mark R. Huson, Robert Parrino, and Laura T. Starks, “Internal Monitoring Mechanisms and CEO Turnover: A Long-Term Perspective,” Journal of Finance 56 (2001): 2265–2297.

20. Per-Ola Karlsson, Gary L. Neilson, and Juan Carlos Webster, “CEO Succession 2007: The Performance Paradox,” strategy+business (2008). Accessed April 6, 2015. See http://www.strategyand.pwc.com/media/file/CEOSuccession2007.pdf.

21. Dirk Jenter and Katharina Lewellen, “Performance-Induced CEO Turnover,” Stanford University, Tuck School at Dartmouth working paper (2014). Accessed February 4, 2015. See http://www.gsb.stanford.edu/faculty-research/working-papers/performance-induced-ceo-turnover.

22. David F. Larcker and Burson-Marsteller, proprietary study (2001).

23. Shawn Mobbs, “CEOs under Fire: The Effects of Competition from Inside Directors on Forced CEO Turnover and CEO Compensation,” Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 48 (2013): 669–698.

24. Eliezer M. Fich and Anil Shivdasani, “Are Busy Boards Effective Monitors?” Journal of Finance 61 (2006): 689–724.

25. Brickley (2003).

26. Huson, Parrino, and Starks (2001).

27. Jason D. Schloetzer, Matteo Tonello, and Melissa Aguilar (2014).

28. Equilar Inc., “Paying the New Boss: Compensation Analysis for Newly Hired CEOs” (June 2013). Accessed May 5, 2015. See http://www.equilar.com.

29. Patrick Kennedy, “New Target CEO Signs for up to $36.6M,” Star Tribune (August 1, 2014): 1.D.

30. Kevin J. Murphy, “Executive Compensation,” Social Science Research Network (1999). Accessed July 27, 2010. See http://ssrn.com/abstract=163914.

31. Robert Parrino, “CEO Turnover and Outside Succession: A Cross-Sectional Analysis,” Journal of Financial Economics 46 (1997): 165–197.

32. Ken Favaro, Per-Ola Karlsson, and Gary L. Neilson, “CEO Succession 2000-2009: A Decade of Convergence and Compression,” strategy+business 59 (Summer 2010). Accessed May 5, 2015. See http://www.strategy-business.com/article/10208.

33. Comparisons were made to industry benchmarks. See Mark R. Huson, Paul H. Malatesta, and Robert Parrino, “Managerial Succession and Firm Performance,” Journal of Financial Economics 74 (2004): 237–275.

34. Content in the following two sections is adapted with permission from David F. Larcker and Brian Tayan, “Multimillionaire Matchmaker: An Inside Look at CEO Succession Planning,” Stanford GSB Case No. CG-21 (April 15, 2010).

35. Stephanie Kang and Joann S. Lublin, “Nike Taps Perez of S.C. Johnson to Follow Knight,” Wall Street Journal (November 19, 2004, Eastern edition): A.3.

36. Joann S. Lublin and Stephanie Kang, “Nike’s Chief to Exit After 13 Months: Shakeup Follows Clashes with Co-Founder Knight; Veteran Parker to Take Over,” Wall Street Journal (January 23, 2006, Eastern edition): A.3.

37. Stephanie Kang, “He Said/He Said: Knight, Perez Tell Different Nike Tales,” Wall Street Journal (January 24, 2006, Eastern edition): B.1.

38. Data from Yahoo Finance! Calculations by the authors. Stock price performance only. Calculations do not include dividends.

39. Edited for clarity. Quote from Steve Watkins, “Kroger’s Dillon on Succession: ‘You Ain’t Seen Nothin’ Yet,’” Business Courier of Cincinnati Online (November 7, 2013).

40. Ben Fritz, “Disney Picks Staggs as No. 2 Executive,” Wall Street Journal (February 6, 2015, Eastern edition): B.1.

41. See also James M. Citrin, “Is a ‘Horse Race’ the Best Way to Pick CEOs?” Wall Street Journal Online (August 3, 2009). Accessed November 10, 2010. See http://online.wsj.com/article/SB124898329172394739.html.

42. Stephen A. Miles and Jeffery S. Sanders, “Creating CEO Succession Processes,” Directorship.com (posted January 27, 2010). Last accessed November 10, 2010. See www.directorship.com/creating-ceo-succession/.

43. Heidrick & Struggles and the Rock Center for Corporate Governance at Stanford University, “2010 CEO Succession Planning survey,” (2010). Accessed May 3, 2015. See http://www.gsb.stanford.edu/faculty-research/publications/2010-ceo-succession-planning-survey.

44. Author interview with Stephen A. Miles, vice chairman of Heidrick & Struggles, September 30, 2009.

45. Monica Langley and Jeffrey McCracken, “Designated Driver Ford Taps Boeing Executive as CEO; Alan Mulally Succeeds Bill Ford, Who Keeps Post of Chairman; A Board Swings into Action,” Wall Street Journal (September 6, 2006, Eastern edition): A.1.

46. Ford Motor Company, Form DEF 14A, filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission April 4, 2008.

47. David F. Larcker, Stephen A. Miles, and Brian Tayan, “Seven Myths of CEO Succession,” Stanford Closer Look Series (March 19, 2014). Accessed May 3, 2015. See http://www.gsb.stanford.edu/faculty-research/centers-initiatives/cgri/research/closer-look.

48. The board should not presume that its favored candidate, internal or external, will accept the job. For this reason, multiple candidates should always be considered, and contingency plans should be in place in case events do not unfold as anticipated. Recruiters recommend that companies engage in regular communication with internal candidates, but survey results suggest that only half of companies do so. A majority (65 percent) have not asked internal candidates whether they want the CEO job or, if offered, whether they would accept. See Heidrick & Struggles and the Rock Center for Corporate Governance at Stanford University (2010).

49. This study is based on John Harry Evans, Nandu J. Nagarajan, and Jason D. Schloetzer, “CEO Turnover and Retention Light: Retaining Former CEOs on the Board,” Journal of Accounting Research 48 (2010): 1015–1047.

50. Jason D. Schloetzer, “Retaining Former CEOs on the Board,” The Conference Board, Director Notes, no. DN-015 (September 2010). Last accessed October 1, 2010. See www.conference-board.org/publications/publicationdetail.cfm?publicationid=1854.

51. Heidrick & Struggles and the Rock Center for Corporate Governance at Stanford University (2010).

52. Gary A. Ballinger and Jeremy J. Marcel, “The Use of an Interim CEO during Succession Episodes and Firm Performance,” Strategic Management Journal 31 (2010): 262–283.

53. James M. Citrin and Dayton Ogden, “Succeeding at Succession,” Harvard Business Review 88 (November 2010): 29–31. Accessed November 17, 2010. See http://hbr.org/2010/11/succeeding-at-succession/ar/1.

54. Heidrick & Struggles and the Rock Center for Corporate Governance at Stanford University (2010).

55. The Conference Board, the Institute of Executive Development, and the Rock Center for Corporate Governance at Stanford University, “How Well Do Corporate Directors Know Senior Management?” (2014). Accessed May 3, 2015. See http://www.gsb.stanford.edu/faculty-research/publications/2014-how-well-do-corporate-directors-know-senior-management.

56. Securities Lawyer’s Deskbook, “Rule 14-8: Proposals of Security Holders.” Accessed May 3, 2015. See https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/17/240.14a-8.

57. SEC Staff Legal Bulletin 14E (CF), “Shareholder Proposals” (October 27, 2009). Accessed May 3, 2015. See www.sec.gov/interps/legal/cfslb14e.htm.

58. See David F. Larcker and Brian Tayan, “CEO Succession Planning: Who’s Behind Door Number One?” Stanford Closer Look Series (June 24, 2010). Accessed May 3, 2015. See http://www.gsb.stanford.edu/faculty-research/centers-initiatives/cgri/research/closer-look.

59. Christian Plath, “Moody’s Corporate Governance: Analyzing Credit and Governance Implications of Management Succession Planning,” Moody’s Investor Service (May 15, 2008). Accessed November 6, 2010. See http://ssrn.com/abstract=1285082.

60. Shivaram Rajgopal, Daniel Taylor, and Mohan Venkatachalam, “Frictions in the CEO Labor Market: The Role of Talent Agents in CEO Compensation?” Contemporary Accounting Research 29 (2012): 119–151.

61. American Electric Power, Form DEF 14A, filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission March 14, 2005. The IRS prohibits the tax deductibility of severance agreements that exceed 2.99 times the executive’s base salary and bonus. See Internal Revenue Code Section 280G, “Golden Parachute Payments.”

62. The Home Depot, Form 8-K, filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission January 4, 2007.

63. David Yermack, “Golden Handshakes: Separation Pay for Retired and Dismissed CEOs,” Journal of Accounting and Economics 41 (2006): 237–256.