2. International Corporate Governance

In Chapter 1, “Introduction to Corporate Governance,” we defined corporate governance as the collection of control mechanisms that an organization adopts to prevent or dissuade potentially self-interested managers from engaging in activities detrimental to the welfare of shareholders and stakeholders. The governance system that a company adopts is not independent of its environment. A variety of factors inherent to the business setting shape the governance system. These factors include the following:

• Efficiency of local capital markets

• Extent to which the legal system provides protection to all shareholders

• Reliability of accounting standards

• Enforcement of regulations

• Societal and cultural values

Differences in these factors have important implications for the prevalence and severity of agency problems and the type of governance mechanisms required to monitor and control managerial self-interested behavior.

In this chapter, we evaluate the research evidence on these factors and consider how they give rise to the governance systems observed in different countries. We then illustrate these principles by providing an overview of governance systems in selected countries. You will see that although globalization has tended to standardize certain features (such as an independence standard for the board of directors), international governance systems as a whole remain broadly diverse. This diversity reflects the unique combination of economic, legal, cultural, and other forces that have developed over time. Therefore, the national context is important to understanding how governance systems work to shape managerial behavior.

Capital Market Efficiency

Markets set the prices for labor, natural resources, and capital. When capital markets are efficient, these prices are expected to be correct based on the information available to both parties in a transaction. Accurate pricing is necessary for firms to make rational decisions about allocating capital to its most efficient uses. Owners of the firm are rewarded for rational decision making through an increase in shareholder value. When capital markets are inefficient, prices are subject to distortion, and corporate decision making suffers.

Efficient capital markets also act as a disciplining mechanism on corporations. Companies are held to a “market standard” of performance, and those that fail to meet the standard are punished with a decrease in share price. Companies that do not perform well over time risk going out of business or becoming an acquisition target. (We discuss this more in Chapter 11, “The Market for Corporate Control.”) If the market is not reasonably efficient, shareholders cannot rely on the market for corporate control to punish management for making poor capital allocation decisions that decrease shareholder value.

Rajan and Zingales (1998) demonstrated the importance of capital markets by measuring the relationship between capital market efficiency and economic growth across countries. They found that industries that require external financing grow faster in countries with efficient capital markets. They concluded that a well-developed financial market is a source of competitive advantage for firms that rely on external capital for growth.1

If a country does not have efficient capital markets, its companies must instead rely on alternative sources of financing for growth, such as influential wealthy families, large banking institutions, other companies, or governments. As providers of capital, these parties also discipline corporate behavior because they actively monitor their investments. However, because their objectives might differ from the pure financial returns that the investing public seeks, their capacity to act as a disciplining mechanism might not align with the interests of shareholders or stakeholders. For example, a wealthy family might be satisfied with below-market returns if it can use a position of control over the organization to extract other benefits—such as corporate perquisites, social prestige, or political influence.

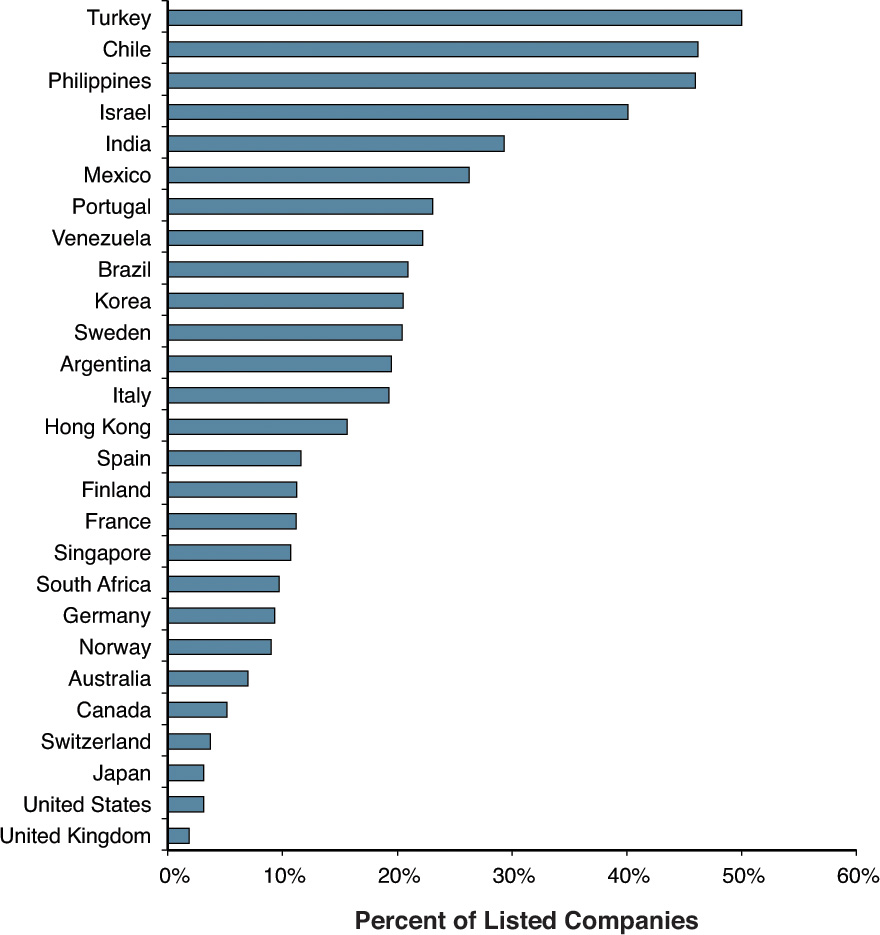

Masulis, Pham, and Zein (2011) demonstrate that family-controlled business groups are more prevalent in countries with weak capital markets and serve as an important source of financing in these countries. Across a broad sample of nations, they found that 19 percent of publicly listed companies belong to a family-controlled group. The figures are lowest (less than 5 percent) in developed economies such as Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States, and highest (more than 40 percent) in emerging markets such as Chile, Israel, and Turkey (see Figure 2.1). The authors also found that pyramidal family groups are an important source of capital for “high-risk, capital intensive firms that could otherwise find it difficult to attract external funding, especially in weak capital markets.”2

Source: Adapted by David F. Larcker and Brian Tayan. Data from: Masulis, Pham, and Zein (2011).

Figure 2.1 Family-controlled business groups in selected countries.

Family-controlled business groups bring increased risk to the economy when they operate with minimal external oversight and when their objectives are to extract rents at the expense of shareholders or stakeholders. For example, Black (2001) concluded that poor accounting disclosure and weak oversight enabled family-controlled business groups in Korea to mask operating problems and prop up weak subsidiaries with financial guarantees that were not disclosed to creditors. Such practices were not sustainable and eventually contributed to the Asian financial crisis of 1997.3 As such, family control can lead to serious agency problems that retard economic growth.4

To this end, Leuz, Lins, and Warnock (2009) found that foreigners invest less money in companies that insiders control and that reside in countries with weak investor protections and lower transparency. They concluded that “firms with problematic governance structures, particularly those with high levels of insider control and from countries with weak institutions, are likely to be more taxing to foreign investors in terms of their information and monitoring costs, which in turn could explain why foreigners shy away from these firms.”5

Finally, efficient capital markets can also serve as a disciplining mechanism on managerial behavior when they are appropriately used in compensation contracts. By offering equity-based incentives such as stock options, the firm can align the interests of management and shareholders. This discourages management from taking self-interested actions that reduce firm value. The absence of an efficient market essentially limits the effectiveness of these types of incentives. In such a setting, agency problems might be best addressed by requiring managers to hold direct and substantial equity positions, by active regulation, or by other governance features that do not rely on efficient capital markets. (We discuss equity incentives in greater detail in Chapters 8, “Executive Compensation and Incentives,” and 9, “Executive Equity Ownership.”)

Legal Tradition

A country’s legal tradition has important implications on the rights afforded to business owners and minority shareholders. Business owners are particularly concerned with the protection of their property against expropriation, the predictability of how claims will be resolved under the law, the enforceability of contracts, and the efficiency and honesty of the judiciary. Minority shareholders are concerned with how the legal system protects their ownership rights and discourages abuse by controlling owners. A system that provides strong protection can be an important factor in mitigating the prevalence and severity of agency problems because penalties can be imposed on self-interested managers or insiders. However, if the legal system is corrupt or cannot be relied upon to provide appropriate protections, this disciplining device will not constrain agency problems.

La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, Shleifer, and Vishny (1998) found that countries whose legal systems are based on a tradition of common law afford more rights to shareholders than countries whose legal systems are based on civil law (or code law).6 The authors also found that creditors are afforded greater protection in common-law countries. They concluded that governance systems are more effective in countries that combine common-law tradition with a reliable enforcement mechanism (discussed in the later section “Enforcement of Regulations”). In a separate study, La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, Shleifer, and Vishny (2002) found that companies operating in countries whose legal systems protect minority interests have higher stock market valuations than companies operating in countries with lesser protections.7

Similarly, studies have shown that political corruption has a negative impact on economic development. According to the World Bank, corruption “undermines development by distorting the rule of law and weakening the institutional foundation on which economic growth depends.”8 Mauro (1995) found that higher levels of corruption are associated with lower economic growth and lower private investment.9 He explained that a corrupt government provides worse protection of property rights and that bureaucratic delay in granting licenses can deter investment in technological advancement. Finally, Pantzalis, Park, and Sutton (2008) found that political corruption is associated with lower corporate valuations.10

If the legal system is corrupt, unpredictable, or ineffective, alternative disciplining mechanisms are necessary in the governance process. For example, if contracts are not enforced through traditional legal channels, they could be “enforced” by the threat of not engaging in future business with the other party. Firms could place directors on the boards of companies that are important suppliers or customers to monitor management and to ensure that contracts are honored. These mechanisms would enable the firms to bypass the legal system and to ensure that shareholder and stakeholder interests are protected.

Accounting Standards

Reliable and sensible accounting standards are critical in ensuring that financial statements convey accurate information to shareholders. Investors rely on this information to evaluate investment risk and reward. Inaccurate information and low levels of transparency can lead to poor decision making and reduce the efficiency of capital markets. The practice of hiring an external auditor to review the application of accounting principles improves investor confidence in financial reporting.

Reliable accounting standards also are critical in ensuring the proper oversight of management. Shareholders and stakeholders use this information to measure performance and detect agency problems. The board of directors uses this information to structure appropriate compensation incentives and to award bonuses. If accounting standards lack transparency or if management manipulates their application, financial reporting will suffer, compensation incentives will be distorted, and shareholders and stakeholders will be less effective in providing oversight.

To improve the integrity of financial reporting, regulators have devised standards that are based on the expert opinions of economists, academics, auditors, and practitioners. In some countries, such as the United States and Japan, accounting systems are rules-based—that is, they prescribe detailed rules for how accounting standards should be applied to various business activities. In other countries, such as many European nations, accounting systems are principles-based—they outline general accounting concepts but do not always dictate the specific application of these concepts to business activities (see the following sidebar).

Academic research demonstrates the importance of reliable accounting standards. Barth, Landsman, and Lang (2008) found, among a sample of companies in 21 countries, that firms that adopted international accounting standards exhibited less earnings management, more timely recognition of losses, and higher-quality measurements of net income and equity book value compared to companies that used domestic accounting standards.11 Similarly, Ernstberger and Vogler (2008) found that German companies that adopted international accounting standards had a lower cost of capital than companies that continued to use German GAAP, which they attributed to an “accounting premium” that comes through improved earnings quality and disclosure.12 Francis, Huang, Khurana, and Pereira (2009) found that transparency in financial disclosure contributed to higher national economic growth rates through efficient resource allocation.13

However, the adoption of reliable accounting standards does not guarantee the integrity of financial reporting. Benston, Bromwich, and Wagenhofer (2006) warned that principles-based accounting systems have potential shortcomings because they provide less-strict guidance and are subject to management interpretation. They cited a 2002 review by accounting regulators in the United States that questioned whether the adoption of a concept-based system “could lead to situations in which professional judgments, made in good faith, result in different interpretations for similar transactions and events, raising concerns about comparability.”14 Price, Román, and Rountree (2011) found that compliance with accounting codes does not necessarily lead to increased transparency or better corporate performance. They concluded that institutional features of the business environment—including ownership characteristics, board attributes, and protection of minority rights by the legal system—are also important contributors to effective governance.15

If accounting rules are unreliable or external auditors cannot be trusted to verify their proper application, countries will require a substitute mechanism to discourage agency problems. These might include severe legal penalties for abuse and vigilant enforcement mechanisms. Investors, customers, and suppliers might circumvent financial reporting information and only rely on companies trusted over time through long interaction or family relationships.

Enforcement of Regulations

Legal and regulatory mechanisms alone cannot protect the interests of minority shareholders. Government officials must be willing to enforce the rules in a fair and consistent manner. Regulatory enforcement mitigates agency problems by dissuading executives from engaging in behaviors such as insider trading, misleading disclosure, self-dealing, and fraud because they acknowledge a real risk of punishment.

Hail and Leuz (2006) found that countries with developed securities regulations and legal enforcement mechanisms have a lower cost of capital than those that lack these characteristics. Controlling for macroeconomic and firm-specific factors, the authors found that differences in securities regulation and legal systems explain about 60 percent of country-level differences in implied equity cost of capital. The importance of regulatory enforcement is greater in countries whose economies are not integrated into international capital markets (such as Brazil, India, and the Philippines) than in those whose economies are integrated (such as Belgium, Hong Kong, and the United Kingdom). When a country’s economy is integrated into international capital markets, the efficiency of those markets can partially make up for deficiencies in the country-specific securities regulation and legal system.16

Regulatory enforcement also contributes to investor confidence that management will be monitored and property rights will be protected. Bushman and Piotroski (2006) found that companies apply more conservative accounting in countries where public enforcement of securities regulation is strong. Because regulators are more likely to be penalized if the companies they monitor overstate accounting results, they will be more rigorous in their enforcement. Knowing this, companies recognize bad news in their financial reports more quickly to avoid regulatory infractions.17 Similarly, researchers have found that participation in equity markets increases when countries adopt insider trading laws because the laws put outside investors on more even footing with insiders who have access to nonpublic information.18

If regulatory enforcement is weak or inconsistent, shareholders cannot expect to have their interests protected by official channels. Therefore, they have to take a more direct role in governance oversight, either through greater rights afforded through the bylaws and charters or through direct representation on the board. Without these tools, they will demand higher returns on capital to compensate for the greater risk of investing their money.

Societal and Cultural Values

The society in which a company operates also strongly influences managerial behavior. Activities that might be deemed acceptable in some societies are considered inappropriate in others (such as conspicuous personal consumption). This impacts the types of activities that executives are willing to participate in and the likelihood of self-serving behavior. Cultural values also influence the relationship between the company and its shareholders and stakeholders. Although complex and difficult to quantify, these forces play a significant role in shaping governance systems.

For example, corporations in Korea have a responsibility to society as a whole, beyond maximizing shareholder profits. Executives who take actions that benefit themselves at the expense of others are seen as betraying the social trust and bringing disgrace on the corporation and its employees. This cultural norm—the concept of shame, or “lost face”—becomes a disciplining mechanism that deters self-interested behavior, similar to the threat of legal penalties in other nations. By contrast, in Russia, personal displays of wealth are tolerated, and corruption is widely seen as an inevitable aspect of the business process. Executives there might be more likely to take self-interested actions because they do not risk the same level of scorn as executives in Korea. In this case, cultural norms do not act as a successful deterrent, and explicit government regulation and enforcement are likely (see the following sidebar).

Although countries vary on many levels, one of the most important social attitudes that shapes governance systems is the role of the corporation in society. As mentioned in Chapter 1, some countries tend toward a shareholder-centric view, which holds that the primary responsibility of the corporation is to maximize shareholder wealth. Actions such as improving labor conditions, reducing environmental impact, and treating suppliers fairly are seen as desirable only to the extent that they are consistent with improving the long-term financial performance of the firm. Other countries tend toward a stakeholder-centric view, which holds that obligations toward constituents such as employees, suppliers, customers, and local communities should be held in equal importance to shareholder returns.

The United States and the United Kingdom are two countries that predominantly embrace the shareholder-centric view. The laws of these countries stipulate that boards and executives have a fiduciary responsibility to protect the interest of shareholders. If the board of directors of a U.S. company were to reject an unsolicited takeover bid on the premise that it would lead to widespread layoffs, it would likely face lawsuits filed by its investors for not maximizing shareholder value. However, all members of society in these countries might not uniformly adopt the shareholder-centric view. For example, union pension funds advocate stakeholder-friendly objectives, such as fair labor laws, and environmental groups encourage corporations to embrace sustainability goals even if they might increase the company’s cost of production. Many corporations embrace these objectives as well, even as their primary focus remains on long-term value creation.

In other societies, the stakeholder-centric view dominates. For example, German law is based on a philosophy of codetermination, in which the interests of shareholders and employees are expected to be balanced in strategic considerations. Germanic legal code enforces this approach by mandating that employees have either one-third or one-half representation on the supervisory board of German companies (depending on the size of the company). In this way, labor is given a real vote on corporate direction. (We consider the impact of employee board representation in Chapter 5, “Board of Directors: Structure and Consequences.”) The Swedish government encourages full employment through consequences that make it difficult to carry out large-scale layoffs, even though such a policy runs the risk of decreasing firm profitability. In Asia, the Japanese are known for job protection and rewarding employees for tenure. In one survey of international executives, only 3 percent of respondents from Japan agreed that a company should lay off workers to maintain its dividend during difficult economic times. In the United States and the United Kingdom, 89 percent of respondents believed that maintaining the dividend was more important.21

Individual National Governance Structures

To get a better sense of how economic, legal, and cultural realities contribute to the governance systems in specific markets, we will consider and compare the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, Japan, South Korea, China, India, Brazil, and Russia.

United States

The United States has the largest and most liquid capital markets in the world. U.S. publicly listed companies had an aggregate market value of $22 trillion, representing approximately 35 percent of the total value of equity worldwide, in 2014.22 The U.S. market is the largest by trading volume, by value of public equity offerings, and by corporate and securitized debt outstanding.23

The most important governance regulatory body in the United States is the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Congress created the SEC through the Securities and Exchange Act of 1934 to oversee the proper functioning of primary and secondary financial markets, with an emphasis on the protection of security holder rights and the prevention of corporate fraud. Among its various powers, the SEC has the authority to regulate securities exchanges (such as the New York Stock Exchange [NYSE], the NASDAQ, and the Chicago Mercantile Exchange), bring civil enforcement actions against companies or executives who violate securities laws (through false disclosures, insider trading, or fraud), ensure the quality of accounting standards and financial reporting, and oversee the proxy solicitation and annual voting process.

Although the SEC bears ultimate responsibility for the quality of accounting standards, it has delegated the process of drafting them to the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB). Founded in 1973, the FASB is a nonprofit organization composed of accounting experts from academia, industry, audit firms, and the investing public. These individuals draft accounting provisions based on accounting and economic principles, taking into consideration the perspective of practitioners. Then they release draft rules for public comment and update the rules as necessary before adoption. After these rules are adopted, they become part of U.S. GAAP. As mentioned earlier, U.S. regulators have signaled an intention to transition from U.S. GAAP to IFRS to increase comparability of financial reporting between the United States and other countries.

Approximately 27 percent of all publicly traded companies in the United States are incorporated in their state of origin, 63 percent in the state of Delaware, and 10 percent in a state other than these.24 Delaware has the most developed body of case law, which gives companies clarity on how corporate matters might be decided if they come to trial. Furthermore, trials over corporate matters in Delaware are heard by a judge instead of a jury, a process that some companies prefer because they believe it reduces their liability risk.25

Companies are required to comply with the listing requirements of the exchanges on which their securities trade. The largest exchange in the United States is the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE). The NYSE requires that a listed company have at least 400 shareholders, maintain a minimum market value and trading volume in its securities, and demonstrate compliance with the following governance standards:

• The listed company’s board is required to have a majority of independent directors.

• Nonexecutive directors must meet independently from executive directors on a scheduled basis.

• The compensation committee of the board must consist entirely of independent directors.

• The audit committee must have a minimum of three members, all of whom are “financially literate” and at least one of whom is a “financial expert.”

• The company must have an internal audit function.

• The chief executive officer (CEO) must certify annually that the company is in compliance with NYSE requirements.

The NYSE Corporate Governance Rules provide a detailed definition of board member independence, which the NYSE defines as the director having “no material relationship with the listed company.”26 However, each company is allowed a degree of discretion in determining whether a board member meets certain of these criteria. Likewise, the NYSE affords flexibility to companies in establishing guidelines for director qualifications, director responsibilities, access to management and independent advisors, compensation, management succession, and self-review. (Legal and regulatory issues are discussed more fully in Chapter 3, “Board of Directors: Duties and Liability.”)

One important piece of federal legislation related to U.S. governance is the Sarbanes–Oxley Act of 2002. Important provisions of Sarbanes–Oxley include the following:

• The requirement that the CEO and chief financial officer (CFO) certify financial results (with misrepresentations subject to criminal penalties)

• An attestation by executives and auditors to the sufficiency of internal controls

• Independence of the audit committee of the board of directors (as incorporated in the listing standards of the NYSE)

• A limitation of the types of nonaudit work an auditor can perform for a company

• A ban on most personal loans to executives or directors

A second important piece of legislation relating to U.S. governance is the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform Act of 2010. Some of the important provisions include the following:

• Say-on-pay—Shareholders are given a nonbinding vote on executive compensation.

• Disclosure—Companies must provide expanded disclosure on executive compensation, pay ratios, hedging of company equity by executives and directors, clawback policies, and golden parachute severance payments due upon a change in control.27

The U.S. governance system is shareholder-centric. Directors have a legal obligation to act “in the interest of the corporation,” which the courts have defined to mean “in the interest of shareholders.” With rare exceptions, employees are not represented on boards of directors. Although shareholders have submitted proxy proposals to further goals of social responsibility—such as environmentalism, fair labor practices, and internal pay equity—few have succeeded. An active market for corporate control and the threat of litigation for companies that do not satisfy shareholder demands serve as effective controls on company behavior. (The market for corporate control and shareholder activism are discussed in Chapters 11, “The Market for Corporate Control,” and 12, “Institutional Shareholders and Activist Investors.”)

Executive compensation is higher in the United States than in most other countries. Fernandes, Ferreira, Matos, and Murphy (2012) found that average total compensation for CEOs in the United States is more than twice what CEOs outside the United States earn ($5.5 million versus $2.3 million).28 Most cross-country differences are explained by pay structure: CEOs who are more highly paid receive a larger percentage of their pay in the form of equity incentives, with U.S. CEOs falling at the high end of the spectrum. It is unknown why CEOs in the United States are paid higher than global averages, but cultural, tax, accounting, political, and other determinants likely are all contributing factors. (Compensation issues are discussed more fully in Chapters 8 and 9.)

United Kingdom

The British model of governance shares many similarities with that of the U.S. model. This likely results from the commonalities between these two countries in terms of capital markets structure, legal tradition, regulatory approach, and societal values. Like the U.S. model, the British model is shareholder-centric, with a single board of directors, management participation on the board (particularly for the CEO), and an emphasis on transparency and disclosure through audited financial reports. This model is generally referred to as the Anglo-Saxon model.

Instead of legislative bodies passing detailed statutes, the British model relies on market mechanisms to determine governance standards. Historically, British Parliament has taken a hands-off approach to regulation. For example, the Companies Act 1985, which consolidates seven Companies Acts passed by Parliament between 1948 and 1983, imposes few governance requirements on companies. The Companies Act 1985 states quite simply that companies are required to have a board (with at least two directors for publicly traded companies) and that the board is responsible for certain administrative functions, including the production of annual financial reports. The Act does not specify a required structure for boards, nor does it mandate procedures for conducting business. The company’s shareholders determine such rules through the articles of association. As a result, U.K. tradition provides flexibility to the corporate body in developing governance standards.

Despite this hands-off approach to regulation, the U.K. has been a leader in governance reform, promoting the following standards of best practices based on the recommendation of expert panels:

• The Cadbury Report (1992)—The accountancy profession and London Stock Exchange commissioned the Cadbury Committee in the early 1990s to provide a benchmark set of recommendations on governance. The committee recommended a set of voluntary guidelines known as the Code of Best Practices. These included the separation of the chairman and CEO titles, the appointment of independent directors to the board, reduced conflicts of interest at the board level because of business or other relationships, the creation of an independent audit committee, and a review of the effectiveness of the company’s internal controls. The recommendations of the Cadbury Committee set the basis for the standards for the London Stock Exchange and have influenced governance standards in the U.S. and several other countries. (See the sidebar that follows.)29

• The Greenbury Report (1995)—The Greenbury Committee was commissioned to review the executive compensation process. The committee recommended establishing an independent remuneration committee entirely comprised of nonexecutive directors.30

• The Hampel Report (1998)—The Hampel Committee was established to review the effectiveness of the Cadbury and Greenbury reports. The committee recommended no substantive changes and consolidated the Cadbury and Greenbury reports into the Combined Code of Best Practices, which the London Stock Exchange subsequently adopted.31

• The Turnbull Report (1999)—The Turnbull Committee was commissioned to provide recommendations on ways to improve corporate internal controls. The committee recommended that companies review the nature of risks facing their organization, establish processes by which these risks are identified and remedied, and perform an annual review of internal controls to assess their effectiveness. The report was updated in 2005.32

• The Higgs Report (2003)—The British government asked Sir Derek Higgs to evaluate the role, quality, and effectiveness of nonexecutive directors.33 Higgs recommended structural changes to the board, including the standards that at least half of the board be nonexecutive directors, that the board appoint a lead independent director to serve as a liaison with shareholders, that the nomination committee be headed by a nonexecutive director, and that executive directors not serve more than six years on the board. The Higgs Report also advised an annual board evaluation.34 The recommendations of the Higgs Report were combined with those of the Turnbull Report and the Combined Code to create the Revised Combined Code of Best Practices. The recommendations of the Higgs Report were replaced in 2011.35

• The Walker Review (2009)—David Walker was asked to review corporate governance practices among U.K. banks to reduce their risk to the economy. Walker recommended structural changes, particularly to executive compensation. These included the standard that at least half of bank employee remuneration be in the form of long-term incentives and that two-thirds of cash bonuses be deferred.36

• Guidance on Board Effectiveness (2011)—The Institute of Chartered Secretaries and Administrators (ICSA) was commissioned to review the recommendations of the Higgs Report. The ISCA recommended that the Higgs Report be withdrawn and replaced with updated guidance that place greater emphasis on the roles and behaviors of directors. These include standards that emphasize ethical leadership, clearly defined responsibilities, productive boardroom dynamics, and the timely sharing of information. These recommendations were incorporated into the Revised Combined Code, which is now known as the U.K. Corporate Governance Code.37

Together, these reports have shaped the board of directors into a monitoring and control body in addition to a strategy-setting body.38

Publicly traded companies in the United Kingdom are not legally required to adopt the standards of the U.K. Corporate Governance Code. Instead, the London Stock Exchange requires that they issue an annual statement to shareholders, explaining whether they are in compliance with the Code and, if not, stating their reasons for noncompliance. This practice, known as comply or explain, puts the burden on public shareholders to monitor whether the company’s explanation for noncompliance is acceptable. As a result, the Code advocates a flexible standard that grants a company, its board, and its shareholders discretion in devising appropriate governance processes.

It is widely accepted that the Code has improved governance standards in the U.K. and the countries that have adopted its key provisions. Still, sparse academic evidence supports this claim. Shabbir and Padgett (2008) found only weak evidence that compliance with Code provisions is correlated with stock price performance, and they found no evidence that compliance is correlated with operating performance.39 This is not to say that the Code has not contributed to governance quality but simply that any improvements are difficult to detect. (We examine the evidence for specific provisions, such as independence, lead directors, and the separation of the chairman and CEO positions, in Chapter 5.)

Economics aside, the comply-or-explain system enables us to observe which governance provisions are deemed useful from the board’s perspective. Surprisingly, a recent study by accounting firm Grant Thornton found that 43 percent of the largest 350 companies on the London Stock Exchange were not fully compliant. The most frequent areas of noncompliance were an insufficient number of independent directors (13 percent), failure to have a remuneration committee with at least three independent directors (7 percent), and failure to separate the roles of chairman and CEO (6 percent).40 Such information might help explain why studies have not found a correlation between compliance levels and operating performance: perhaps companies are prudently rejecting recommended best practices that are inappropriate for their specific situation. Alternatively, it may be the case that the reported governance provisions are not generally important for mitigating agency problems and increasing shareholder value.

The U.K. has also been a leader in compensation reform. In 2002, Parliament passed the Directors’ Remuneration Report Regulations, which require that shareholders be granted an advisory vote on director and executive compensation (say-on-pay). In 2012, Parliament approved legislation making the results of say-on-pay binding. Say-on-pay policies have been adopted in varying form by Australia, the Netherlands, Sweden, Norway, India, and the United States. However, as we discuss in Chapter 8, say-on-pay has had a mixed impact on the rate of compensation increases in countries that have adopted this practice.

Germany

Legal tradition in Germany is based on civil code instead of the common-law tradition of the United Kingdom and the United States. A civil-code tradition means that legislation mandates more aspects of governance, and German corporations are afforded less discretion to determine their own structures and processes. For example, German law stipulates that corporations have a two-tiered board structure (instead of the unitary structure practiced in the Anglo-Saxon model). One board is the management board (Vorstand), which is responsible for making decisions on such matters as strategy, product development, manufacturing, finance, marketing, distribution, and supply chain. The second board is the supervisory board (Aufischtsrat), which oversees the management board. The supervisory board is responsible for appointing members to the management board; approving financial statements; and making decisions regarding major capital investment, mergers and acquisitions, and the payment of dividends. No managers are allowed to sit on the supervisory board. Members of the supervisory board are elected annually by shareholders at the general meeting.41

The law requires the supervisory board to have employee representation. Under the German Corporate Governance Code, a company that has at least 500 employees must allocate one-third of its supervisory board seats to labor representatives; a company with at least 2,000 employees must allocate half to labor. These representation requirements are legal obligations that cannot be amended through bylaw changes. As a result, the German system implicitly places greater emphasis on the preservation of jobs, in contrast to the Anglo-Saxon emphasis on shareholder returns. As mentioned earlier, a system that balances employee and shareholder interest is commonly referred to as codetermination. (Employee board representation is discussed in more detail in Chapter 5.)

German corporate governance also has a tradition of significant ownership and influence from founding family members and German financial institutions. Historically, German corporations have relied heavily on banks instead of capital markets for financing. These relationships grew out of the post–World War II era in which German finance organizations provided loans to hard-hit businesses and received portions of the companies’ ownership as collateral. In return, bank officials were given a seat on the supervisory board. This structure gave German corporations stability through the rebuilding process by ensuring a reliable source of capital for expansion and a major investor with a long-term outlook.42 Even as late as the 1990s, a sample of 158 large German corporations showed that more than half had a shareholder holding more than 50 percent of the equity.43

Given the large representation by labor and financial institutions, German shareholders traditionally have had far less influence over board matters than shareholders in the U.K. and U.S. This structure poses a risk to minority shareholders because they have to rely on other stakeholders to protect their interests. However, increased liberalization of capital markets in recent years and a gradual shift from bank financing to financing through securities markets are beginning to undo several features of this system. German financial institutions have divested many of their block ownership stakes in public corporations. By 2014, none of the 30 companies comprising the DAX Index had a shareholder with more than 50 percent of the equity; the average ownership stake of the largest blockholder decreased from 31 percent in 2001 to 15 percent in 2014.44

The German corporate governance system faces several serious challenges from globalization. Although German citizens might prefer a system of codetermination, the international investment community demands financial returns. This has created conflicts as German corporations balance the needs of employees and shareholders. A second challenge is dealing with a rising level of executive compensation. As corporations grow in size and compete with foreign multinationals for executive talent, compensation levels have risen. For example, politicians and the media criticized Volkswagen CEO Martin Winterkorn for accepting €17.5 million ($23 million) in compensation in 2011 and €20 million in 2012, the highest among companies in the DAX Index.45 Although payments of this magnitude are more common in the United States, it is considered unacceptable by the cultural standards of Europe, which place greater emphasis on social equality. Conflicts over the role of the corporation and executive compensation levels will likely continue in future years.

Japan

As in Germany, the Japanese system of governance has its roots in post–World War II reconstruction. At the end of the war, Allied forces banned the Japanese zaibatsu, the powerful industrial and financial conglomerates that accounted for much of the country’s pre-war economic strength. The Japanese responded by developing a loose system of interrelations between companies, called the keiretsu. Under the keiretsu, companies maintain small but not insignificant ownership positions among suppliers, customers, and other business affiliates. These ownership positions cement business relations along the supply chain and encourage firms to work together toward an objective of shared financial success. As in Germany, bank financiers own minority stakes in industrial firms and are key partners in the keiretsu. Their investments indicate that capital for financing is available as needed.

The culture in Japan is highly stakeholder-centric, and companies view themselves as having a responsibility to contribute to the prosperity of the nation. One of the most important objectives of Japanese management is to encourage the success of the entire supply chain, including industrial and financial partners. Another objective is to maintain healthy levels of employment and preserve wages and benefits. Proponents believe that the Japanese system, unlike Western styles of capitalism, encourages a long-term perspective, builds internal commitment to organizational success, and shares the benefits of success more equitably among constituents. Critics of the Japanese system believe it to be insular and overly resistant to change. (See the following sidebar.)

In 2002, the Japanese Ministry of Justice modified its laws to encourage the adoption of Western-style systems of governance. The revised code enabled Japanese companies to choose between a keiretsu board structure and one with majority-independent audit, nomination, and compensation committees. It also granted board members new authority to delegate broad powers to senior management, including discretion to access public markets for debt and equity. The code revisions enhanced shareholder rights as well, such as the right to appoint or dismiss certain directors and the external auditor. Companies were also allowed more freedom to issue employee stock options. These revisions were intended to improve governance quality, facilitate access to global capital markets, and increase transparency and accountability.49 Evidence shows that it was only moderately successful. Eberhart (2012) found that companies that adopted these governance changes experienced a subsequent increase in their market-to-book ratio. However, he did not find an improvement in operating performance.50

In addition, Japanese companies are facing many of the same pressures from globalization as German companies. As Japanese companies access global capital markets, international institutional shareholders have somewhat replaced the influence of major banks.51 For the first time, Japanese companies find themselves faced with shareholder activists that emphasize operational efficiency and shareholder value over stable employment and conservative management. To shield themselves, companies have adopted defense mechanisms such as “poison pills” (discussed further in Chapter 11). Although shareholder activists are critical of these measures, traditionalists believe that the measures are necessary to preserve the prevailing culture of respect and cooperation between the company and its stakeholders.

Recent events, including a major accounting scandal at Olympus Corporation and renewed emphasis on economic revitalization, have given new momentum to governance reform. In 2014, the Japanese Financial Services Authority adopted a Stewardship Code to encourage dialogue between Japanese corporations and institutional investors. The Stewardship Code calls on shareholders to engage with corporations to enhance medium- and long-term investment returns and disclose how the fund votes at the annual meeting.52 The Japanese government has also taken additional steps to encourage independent oversight of management. In 2014, Parliament enacted a law requiring companies to appoint at least one independent director or, if not, disclose the reason for not doing so. Separately, the prime minister announced the country’s first effort to develop a national corporate governance code based on international principles to improve governance standards in the country. Major provisions included expanded shareholder rights, enhanced disclosure on cross-holdings and related-party transactions, and board-level reforms.53 The changes were intended to attract foreign investors and improve economic returns.

South Korea

Korean economic activity is dominated by conglomerate organizations known as the chaebol, which means “financial house.” Chaebol are not single corporations but groups of affiliated companies that operate under the strategic and financial direction of a central headquarters. A powerful group chairman, who holds ultimate decision-making authority on all investments, leads headquarters.

The chaebol structure was formed following the Korean War. During reconstruction, business leaders worked with government officials to develop a plan for economic growth. Together they identified industries that were deemed critical for the country’s long-term success. These included everything from shipbuilding and construction, to textiles, to financial services. The government offered subsidized loans to business leaders to encourage new investment, and business leaders used these loans to expand aggressively. Although investments were managed as separate enterprises, they shared a common affiliation. The plan was highly successful: the Korean economy grew at an almost unprecedented rate. With economic prosperity came great wealth for the chaebol. In 1995, the 30 largest chaebol accounted for 41 percent of total domestic sales in South Korea.54

However, deficiencies in the chaebol structure came to light in the Asian financial crisis of 1997. First, they were overly insulated from the market forces that compel efficiency. Founding families had unequal voting rights in proportion to their economic interest (two-thirds voting interest compared with 25 percent economic rights), so their decision making was unchallenged. Second, chaebol did not rely on public capital markets for financing, instead relying on internal sources, bank loans, and government subsidies. Therefore, the chaebol were not subject to the disciplining force of institutional shareholders.

Over time, these factors led to deterioration in the financial strength of the chaebol. Despite their size, they were not very profitable. By the mid-1990s, most were publicly traded at a market-to-book ratio of less than 1, indicating that the financial value of their assets was less than historical investment cost. Furthermore, they were highly leveraged. A debt-to-equity ratio of 5 to 1 was not uncommon.55 In addition, group affiliates were tied together by financial guarantees. This created interconnections that made affiliates more vulnerable to financial distress than was initially apparent. Because the groups were not required under accounting rules to disclose these obligations, their true financial condition was apparently unknown to regulators, investors, and creditors. However, the Asian financial crisis brought these troubles into public view. When the Korean currency collapsed, the chaebol were unable to repay their debts, many of which were denominated in U.S. dollars. Eight chaebol went bankrupt in 1997 alone.

To bring stability to the Korean economy and boost investor confidence, the government issued a series of reforms. First, the practice of transferring funds between chaebol affiliates was eliminated. Group companies were forced to become financially self-sufficient, although they could still operate under the strategic direction of group headquarters. Regulators also passed governance reforms that boosted board independence, eliminated intergroup guarantees, and afforded greater rights to minority shareholders. These standards applied only to large corporations with assets greater than 2 trillion won (approximately $2 billion); small companies were exempted.56

Black and Kim (2012) examined the impact of these reforms and found superior stock price performance for the companies that adopted them.57

China

The Chinese model of corporate governance reflects a partial transition from a communist regime to a capitalist economic system. The Chinese government owns a full or controlling interest in many of the country’s largest corporations. Although the government seeks to improve the efficiency of its enterprises, it balances these objectives against stakeholder concerns. These include maintaining high levels of employment and ensuring that critical industries—such as banking, telecommunications, energy, and real estate—are protected from excessive foreign investment and influence.

Chinese companies issue three types of shares: those held by the state, those held by founders and employees, and those held by the public. Shares held by the public fall into three categories: A-shares, B-shares, and H-shares. A-shares trade on the Shanghai Stock Exchange and the Shenzhen Stock Exchange on mainland China. Ownership is restricted to domestic investors, and shares are denominated in renminbi. B-shares also trade on the Shanghai and Shenzhen markets but are denominated in foreign currencies. H-shares trade on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange and are available to foreign investors. H-shares are denominated in Hong Kong dollars. The ownership restrictions placed on these markets have created vastly different liquidity levels, and it is not uncommon for A-shares and H-shares to trade at divergent valuations (with A-shares trading at a significant premium). In addition, limited float and ownership restrictions limit the influence of public shareholders in China.

The Company Law of the People’s Republic of China (revised in 2005) outlines the governance requirements for publicly traded companies.58 Chinese companies are required to have a two-tiered board structure, consisting of a board of directors and a board of supervisors. The board of directors has between 5 and 19 members and usually includes a significant number of company executives. The board of directors is permitted (but not required) to have employee representation. In contrast, the board of supervisors is required to have three or more members, at least one-third of whom are employee representatives. No members of the board of directors or executives are allowed to serve on the board of supervisors.59 Companies are not required to have audit or compensation committees unless they choose to list their shares on foreign exchanges that require them (such as the NYSE).

The Chinese government maintains significant influence over publicly traded companies. The government selects the companies that are eligible for public listing. It is also often a significant shareholder and has representatives serving on the board of supervisors. For example, PetroChina was a publicly traded company with shares listed on the NYSE (American depository shares, or ADSs), the Hong Kong Stock Exchange (H-shares), and the Shanghai Stock Exchange (A-shares) in 2014. However, only 14 percent of the company’s shares were freely traded by the public in these three markets; the remaining 86 percent of its shares were held by China National Petroleum Corp. (CNPC), which was itself 100 percent owned by the Chinese government.60

Research suggests that governance quality might be lower among state-controlled entities. Conyon and He (2011) found that Chinese-listed companies with fewer independent directors were less likely to terminate an underperforming CEO. These companies were also less likely to grant equity-based compensation linking pay with performance.61

India

Following India’s independence from British rule in 1947, the country pursued a socialist economic agenda. Public policy was intended to encourage economic development in a variety of manufacturing industries, but burdensome regulatory requirements led to low productivity, poor-quality products, and marginal profitability. National banks, which provided financing to private companies, often evaluated loans on the size of capital required and the number of jobs created instead of the companies’ return on investment.62 As a result, private companies had little incentive to deploy capital efficiently, and a weak system of corporate governance evolved.

By 1991, the economic situation in the country had deteriorated to such an extent that the Indian government passed a series of major reforms to liberalize the economy and encourage a competitive financial system. With these reforms came pressure to improve governance standards. As a first step, the Confederation of Indian Industries (CII) created a voluntary Corporate Governance Code in 1998. Large companies were encouraged, although not required, to adopt the standards of the Code. One year later, the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) commissioned the Kumar Mangalam Birla Committee to propose standards of corporate governance that would apply to companies listed on the Indian stock exchange. These reforms were incorporated in Clause 49 and applied to all publicly traded companies. In 2004, a second panel, chaired by N. R. Narayana Murthy, chairman of Infosys, made additional recommendations to revise and further update Clause 49.

Clause 49 requires a majority of nonexecutive directors on the board. If the chairman is an executive of the company, at least half of the directors must be independent; if the chairman is a nonexecutive, the requirement for independent directors is reduced to one-third. Board members are limited to serving on no more than 10 committees across all boards to which they are elected. Companies are required to have an audit committee consisting of at least three members, two of whom must be independent directors. The CEO and CFO must certify financial statements. Clause 49 also includes extensive disclosure requirements for related-party transactions, board of directors’ compensation and shareholdings in the company, and any financial relationships that might lead to board member conflicts. Companies are required to include a section in the annual report explaining whether they are in compliance with these standards.63

Although India has made significant regulatory reforms in recent years, several challenges remain. One is that capital markets are largely inefficient. Foreign individual investors are restricted in their ability to directly invest in companies listed on the Bombay Stock Exchange and the National Stock Exchange of India.64 These restrictions reduce capital flows and remove an important disciplining mechanism on managerial behavior. The country’s bond markets are also relatively undeveloped. In 2010, the corporate bond market in India had notional value of only $25 billion, less than 2 percent of gross domestic product (GDP). By comparison, the corporate bond market in the United States was $2.9 trillion notional and 20 percent of GDP.65 With public financing less available, corporations must turn to private sources, which often come with their own agency problems and are less effective monitors.

Another challenge to governance reform is the outsized role that wealthy Indian families continue to play in most major corporations. Family-run companies continue to dominate the Indian economy. For example, Tata Group—which has subsidiaries in the auto manufacturing, agricultural chemicals, hospitality, telecommunications, and consulting sectors—accounts for more than 5 percent of the country’s GDP.66 In aggregate, company insiders and their families own approximately 45 percent of the equity value of all Indian companies.67 When insiders own concentrated levels of a company’s equity, corporate assets could be diverted for the personal benefits of these individuals (such as through excessive salary and perquisites), with minority shareholders bearing the cost of these abuses.

Brazil

As in many other emerging economies, corporate governance in Brazil is characterized by excessive influence by insiders and controlling shareholders and by low levels of disclosure. Brazilian law dictates that only one-third of board members must be nonexecutive. As a result, Brazilian boards tend to have a majority of executive directors. Furthermore, no independence standards exist for nonexecutive directors. Therefore, nonexecutive directors tend to be representatives of a controlling shareholder group or former executives. According to a survey by Black, de Carvalho, and Sampaio (2014), 15 percent of Brazilian companies did not have a single independent director, half had fewer than 30 percent independent directors, and only 20 percent had a majority of independent directors.68 Disclosure rules provide further disincentive to add independent directors to the board: Brazilian companies are not required to disclose the independence status of board members, nor are they required to disclose biographical information that would enable a shareholder to infer this information.

Brazilian firms issue two classes of shares: common shares with voting rights and preferred shares that carry no voting rights. Preferred shares do not pay a fixed dividend. Almost all Brazilian companies have a controlling shareholder or a group that owns a majority of the voting shares. These shareholders hold considerable influence in nominating and electing directors, so the board essentially represents their interests. Minority common shareholders and preferred shareholders have much less influence over board selection and can elect only one director by majority vote.

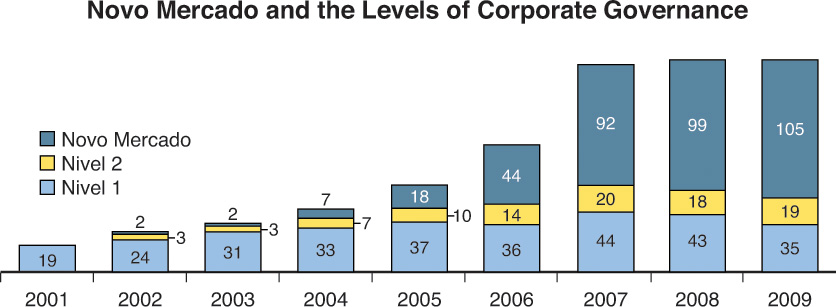

Traditionally, Brazil has had highly regulated capital markets. In the early 1900s, the government ran public exchanges and set transaction fees. Brokers were employees of the state and could pass their positions on to their children. Liberalization began in the 1960s, and by the 1970s, brokerages were transitioned from government control to private ownership. By the 1980s, the largest trading market became the São Paulo Stock Exchange (Bovespa). To stimulate demand for listing on its exchange, Bovespa created three markets for listing based on a company’s governance features. Nivel 1 has the least stringent governance requirements, Nivel 2 has more stringent requirements, and the Novo Mercado has the most stringent requirements. To satisfy the listing requirements of the Novo Mercado, a company must do the following:

• Issue only voting shares

• Maintain a minimum free float equivalent to 25 percent of capital

• Establish a two-year unified mandate for the entire board, which must have at least five members and at least 20 percent independent members

• Publish financial reports in accordance with either U.S. GAAP or IFRS

• Grant minority shareholders the rights to dispose of shares on the same terms as majority shareholders (known as tag-along rights)

These requirements are intended to provide the greatest level of protection for minority shareholders against expropriation by insiders.69

In 2001, the first year the new system was operational, 18 companies transferred their listing to Nivel 1 from the regular exchange. Novo Mercado did not receive its first listing until the following year and did not gain widespread traction until 2004, when Natura, Brazil’s leading cosmetics company, transferred its listing there. Since that point, the number of listed companies on all three of these new exchanges has grown significantly (see Figure 2.3).

Source: Adapted by David F. Larcker and Brian Tayan. Data from: 9th European Corporate Governance Conference (June 28, 2010).

Figure 2.3 Number of companies listed on the Bovespa.

de Carvalho and Pennacchi (2012) found a positive impact on stock prices, trading volume, and liquidity for Brazilian companies that migrate their listing to these new exchanges. They concluded that shareholders positively view the governance changes associated with the new listing requirements.70 Black, de Carvalho, and Sampaio (2014) also found that adoption of Novo Mercado and Level II listing standards was associated with higher market-to-book values.71

Russia

Corporate governance in Russia is characterized by concentrated ownership of shares, insider control, weak legal protection for minority shareholders, modest disclosure, inefficient capital markets, and heavy government involvement in private enterprise. Executives are often controlling shareholders or are closely affiliated with the controlling shareholder, whose interests they tend to serve. A disproportionate number of board members are insiders. In an examination of the boards of directors of the largest 132 public Russian companies in 2012, Deloitte found that an average of two-thirds are executive directors. Among state-controlled entities, insider representation is even higher: 80 percent.72 The vast majority of board members do not represent minority investors.

Controlling shareholders use their influence to increase their claim on corporate assets, sometimes using illegal methods to do so. These methods include forcing solvent companies into bankruptcy to seize assets from minority shareholders, bribing the registrar to lose records of ownership by certain shareholders, manipulating transfer pricing to siphon money to an affiliated company that is wholly owned by the controlling shareholder, and forcing dilution of minority shareholders through a private offering to the controlling shareholder.73 Because legal protections are weak, minority shareholders have limited ability to prevent these actions or seek compensation. For example, BP accused a Russian investor group in 2008 of trying to seize control of joint-venture assets (TNK–BP) by forcing the resignation of the BP-appointed CEO. The chairman of BP stated that the move was “just a return to the corporate raiding activities that were prevalent in Russia in the 1990s [after the fall of the Soviet Union]. Unfortunately, our partners continue to use them and the leaders of the country seem unwilling or unable to step in and stop them.”74 An international investor agreed: “Corporate governance has improved . . . but when someone really wants to break the rules, unfortunately, they can do it. It’s a big concern, as it is causing real losses and damaging investor confidence in this country.” He cited as an example his firm’s investment in a Russian energy company in which “millions of dollars were transferred out of the company in exchange for assets of questionable value.”75

The Russian government is another source of potential abuse for shareholders. The government has shown a tendency to intervene in business to promote its own interests. A primary method involves making dubious claims of unpaid taxes, which are then used as justification for seizing assets. This method was used in 2006 to transfer the assets from privately held Yukos to Gazprom—Russia’s largest oil company, which the Russian government controls. Government corruption also occurs at the regional level, as regional governors accept bribes from local employers in exchange for protection from foreign competition. The government also interferes to maintain employment levels and prevent mass layoffs.

Finally, lack of transparency restricts the influence of shareholders. Disclosure requirements are weak, obscuring the nature of interparty transactions. A state-controlled media also contributes to a lack of transparency.

Black, Love, and Rachinsky (2006) examined the relationship between governance quality and share price in Russia. They found some evidence that firms with better governance features trade at higher market valuations than those with lesser protections.76

Endnotes

1. Raghuram G. Rajan and Luigi Zingales, “Financial Dependence and Growth,” American Economic Review 88 (1998): 559–586.

2. Pyramidal family groups are two or more firms under a common controlling shareholder. See Ronald W. Masulis, Peter Kien Pham, and Jason Zein, “Family Business Groups around the World: Financing Advantages, Control Motivations, and Organizational Choices” Review of Financial Studies 24 (2011): 3556–3600.

3. Bernard Black, “Corporate Governance in Korea at the Millennium: Enhancing International Competitiveness,” Journal of Corporation Law 26 (2001): 537.

4. That said, Kanna and Palepu (1999) warn that family-controlled business groups cannot be safely dismantled unless a so-called “soft infrastructure” is in place, including well-functioning markets for capital, management, labor, and information technology. Tarun Khanna and Krishna Palepu, “The Right Way to Restructure Conglomerates in Emerging Markets,” Harvard Business Review 77 (1999): 125–134.

5. Christian Leuz, Karl V. Lins, and Francis E. Warnock, “Do Foreigners Invest Less in Poorly Governed Firms?” The Review of Financial Studies 22 (2009): 3245–3285.

6. Under common law, judicial precedent shapes the interpretation and application of laws. Judges consider previous court rulings on similar matters and use that information as the basis for settling current claims. By contrast, civil law (or code law) relies on comprehensive legal codes or statutes written by legislative bodies. The judiciary must base its decisions on strict interpretation of the law instead of legal precedent. Examples of common law countries include the United States, England, India, and Canada. Civil law countries include China, Japan, Germany, France, and Spain. See Rafael La Porta, Florencio Lopez-de-Silanes, Andrei Shleifer, and Robert W. Vishny, “Law and Finance,” Journal of Political Economy 106 (1998): 1113–1155.

7. The results in these two La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, Shleifer, and Vishny papers have been examined in subsequent research. For example, Spamann (2010) constructs a new “antidirector rights index” using local lawyers and finds that many of the prior results in these papers become statistically insignificant. Thus, these results might be fragile. See Rafael La Porta, Florencio Lopez-de-Silanes, Andrei Shleifer, and Robert W. Vishny, “Investor Protection and Corporate Valuation,” Journal of Finance 57 (2002): 1147–1170; and Holger Spamann, “The ‘Antidirector Rights Index’ Revisited,” Review of Financial Studies 23 (2010): 467–486.

8. Cited in Jacob de Haan and Harry Seldadyo, “The Determinants of Corruption: A Literature Survey and New Evidence,” paper presented at the Annual Conference of the European Public Choice Society, Turku (April 24, 2006).

9. Paulo Mauro, “Corruption and Growth,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 110 (1995): 681–712.

10. Christos Pantzalis, Jung Chul Park, and Ninon Sutton, “Corruption and Valuation of Multinational Corporations,” Journal of Empirical Finance 15 (2008): 387–417.

11. Mary E. Barth, Wayne R. Landsman, and Mark H. Lang, “International Accounting Standards and Accounting Quality,” Journal of Accounting Research 46 (2008): 467–498.

12. Jürgen Ernstberger and Oliver Vogler, “Analyzing the German Accounting Triad—‘Accounting Premium’ for IAS/IFRS and U.S. GAAP vis-á-vis German GAAP?” International Journal of Accounting 43 (2008): 339–386.

13. Jere R. Francis, Shawn Huang, Inder K. Khurana, and Raynolde Pereira, “Does Corporate Transparency Contribute to Efficient Resource Allocation?” Journal of Accounting Research 47 (2009): 943–989.

14. George J. Benston, Michael Bromwich, and Alfred Wagenhofer, “Principles- Versus Rules-Based Accounting Standards: The FASB’s Standard Setting Strategy,” Abacus 42 (2006): 165–188.

15. Richard Price, Francisco J. Román, and Brian Rountree, “The Impact of Governance Reform on Performance and Transparency,” Journal of Financial Economics 99 (2011): 76–96.

16. Luzi Hail and Christian Leuz, “International Differences in the Cost of Equity Capital: Do Legal Institutions and Securities Regulation Matter?” Journal of Accounting Research 44 (2006): 485–531.

17. Robert M. Bushman and Joseph D. Piotroski, “Financial Reporting Incentives for Conservative Accounting: The Influence of Legal and Political Institutions,” Journal of Accounting and Economics 42 (2006): 107–148.

18. Victor Brudney, “Insiders, Outsiders, and Informational Advantages under the Federal Securities Laws,” Harvard Law Review 93 (1979): 322. See Lawrence M. Ausubel, “Insider Trading in a Rational Expectations Economy,” American Economic Review 80 (1990): 1022–1041. Hayne E. Leland, “Insider Trading: Should It Be Prohibited?” Journal of Political Economy 100 (1992): 859–887.

19. Geert Hofstede, “Cultural Dimensions,” Itim Focus (2015). Accessed March 24, 2015. See http://geert-hofstede.com/national-culture.html.

20. The Hofstede research has been the subject of considerable criticism. We discuss it here as representative of a system for describing cultural attributes without commentary on its accuracy. See Nigel J. Holden, Cross-Cultural Management: A Knowledge Management Perspective (London: FT Prentice Hall, 2002). And Brendan McSweeney, “Hofstede’s Model of National Cultural Differences and Their Consequences: A Triumph of Faith—A Failure of Analysis,” Human Relations 55 (2002): 89–118.

21. Anonymous, “Whose Company Is It? New Insights on the Debate Over Shareholders vs. Stakeholders,” Knowledge@Wharton (2007). Accessed July 7, 2008. See http://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article.cfm?articleid=1826.

22. Despite the impression that diffuse ownership of U.S. securities exists, the ownership of U.S. firms is similar to and, by some measures, more concentrated than the ownership of firms in other countries. See World Federation of Exchanges, “2014 WFE Market Highlights,” WFE Statistics Database. Accessed April 25, 2015. See http://www.world-exchanges.org/insight/reports/2014-WFE-market-highlights. And Clifford G. Holderness, “The Myth of Diffuse Ownership in the United States,” Review of Financial Studies 22 (2009): 1377–1408.

23. However, U.S. markets have been losing their share in several of these categories during recent years. See Committee on Capital Markets Regulation, “The Competitive Position of the U.S. Public Equity Market,” (2007). Accessed June 19, 2014. See http://capmktsreg.org/press/the-competitiveness-position-of-the-u-s-public-equity-market.

24. Computed using 2014 data for 1,871 companies in the Russell 2000 Index covered by SharkRepellent, FactSet Research Systems Inc.

25. Daines (2001) finds that companies incorporated in Delaware are worth approximately 5 percent more than firms incorporated in other states. Debate exists over whether this is because of increased governance quality, greater clarity on shareholder rights, or higher likelihood of receiving a takeover bid from another firm. See Robert M. Daines, “Does Delaware Law Improve Firm Value?” Journal of Financial Economics 62 (2001): 525–558.

26. See Chapter 5 for a discussion of NYSE independence standards. Source: “Corporate Governance Standards, Listed Company Manual Section 303A.02, Independence Tests,” NYSE (2015). Accessed April 9, 2015. See http://nysemanual.nyse.com/LCMTools/PlatformViewer.asp?selectednode=chp_1_4_3_3&manual=%2Flcm%2Fsections%2Flcm-sections%2F.

27. See Weil, Gotshal & Manges, LLP, “Financial Regulatory Reform: An Overview of the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act” (2010). Accessed November 2, 2010. See http://www.weil.com/~/media/files/pdfs/ny%20mailing%2010%20frr%20100721%20weil_dodd_frank_overview_2010_07_21.pdf.

28. Nuno G. Fernandes, Miguel A. Ferreira, Pedro P. Matos, and Kevin J. Murphy, “Are US CEOs Paid More? New International Evidence?” EFA 2009 Bergen Meetings Paper; AFA 2011 Denver Meetings Paper; ECGI—Finance Working Paper No. 255/2009, Social Science Research Network (2012). Accessed April 9, 2014. See http://ssrn.com/abstract=1341639.

29. Adrian Cadbury, “The Financial Aspects of Corporate Governance; Report of the Committee on the Financial Aspects of Corporate Governance” (London: Gee & Co, 1992). Accessed November 3, 2010. See www.ecgi.org/codes/documents/cadbury.pdf.

30. Richard Greenbury, “Directors’ Remuneration: Report of a Study Group Chaired by Sir Richard Greenbury” (London: Gee Publishing, 1995). Accessed November 3, 2010. See www.ecgi.org/codes/documents/greenbury.pdf.

31. Ronnie Hampel, “Committee on Corporate Governance: Final Report” (London: Gee Publishing 1998). Accessed November 3, 2010. See www.ecgi.org/codes/documents/hampel.pdf.

32. Nigel Turnbull, et al., “Internal Control: Guidance for Directors on the Combined Code” (1999). Accessed June 19, 2014. http://www.ecgi.org/codes/documents/turnbul.pdf.

33. Dechert, LLP, “The Higgs Report on Non-Executive Directors: Summary Recommendations” (2003). Last accessed December 5, 2007. See www.dechert.com/library/Summary%20of%20Recommendations1.pdf.

34. Cited in Rob Goffee, “Feedback Helps Boards to Focus on Their Roles,” Financial Times (June 10, 2005): 32.

35. Martin Dickson, “Higgs and the History of Corporate Protest,” Financial Times (February 18, 2003): 25. The Higgs Report was subsequently revised in June 2006 and in May 2010. See www.ecgi.org/codes/documents/frc_combined_code_june2006.pdf. Accessed October 30, 2010. Also see www.frc.org.uk/images/uploaded/documents/May%202010%20report%20on%20Code%20consultation.pdf. Accessed October 30, 2010.

36. David Walker, “A Review of Corporate Governance in UK Banks and Other Financial Industry Entities: Final Recommendations” (November 26, 2009). See http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130129110402/ http://www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/d/walker_review_261109.pdf.

37. Financial Reporting Council, “Guidance on Board Effectiveness,” FRC (2011). Accessed July 15, 2014. See https://www.frc.org.uk/Our-Work/Publications/Corporate-Governance/Guidance-on-Board-Effectiveness.pdf.

38. Paul L. Davies, “Board Structure in the United Kingdom and Germany: Convergence or Continuing Divergence?” Social Science Research Network (2001): 1–24. Accessed October 30, 2010. See http://ssrn.com/abstract=262959.

39. Amama Shabbir and Carol Padgett, “The UK Code of Corporate Governance: Link between Compliance and Firm Performance,” RP 2/08. Cranfield University School of Management (2008). Accessed March 24, 2015. See https://dspace.lib.cranfield.ac.uk/handle/1826/3931.

40. Grant Thornton UK, LLP, FTSE 350 Corporate Governance Review (2013). Accessed July 10, 2014. See http://www.grant-thornton.co.uk/Documents/FTSE-350-Corporate-Governance-Review-2013.pdf.

41. Commission of the German Corporate Governance Code, “German Corporate Governance—Code” (May 26, 2010). Accessed April 9, 2015. See http://www.ecgi.org/codes/code.php?code_id=308.

42. Christopher Rhoads and Vanessa Fuhrmans, “Trouble Brewing: Corporate Germany Braces for a Big Shift from Postwar Stability—Layoffs, Predators, Gadflies Loom with Unwinding of Cross-Shareholdings—Dry Times for Beer Workers,” Wall Street Journal (June 21, 2001, Eastern edition): A1.

43. Jeremy Edwards and Marcus Nibler, “Corporate Governance in Germany: The Role of Banks and Ownership Concentration,” Economic Policy 32 (2000) 239–268.

44. Wolf-Georg Ringe, “Changing Law and Ownership Patterns in Germany: Corporate Governance and the Erosion of Deutschland AG,” Oxford Legal Studies Research Paper No. 42/2014, (2014); American Journal of Comparative Law, forthcoming.

45. Andreas Cremer, “Volkswagen CEO’s Pay Nearly Doubles to 17.5 mln Euros,” Thomson Reuters (March 12, 2012); Anonymous, “Interview with Volkswagen CEO: ‘European Auto Crisis Is an Endurance Test,’” Spiegel Online International (February 13, 2013).

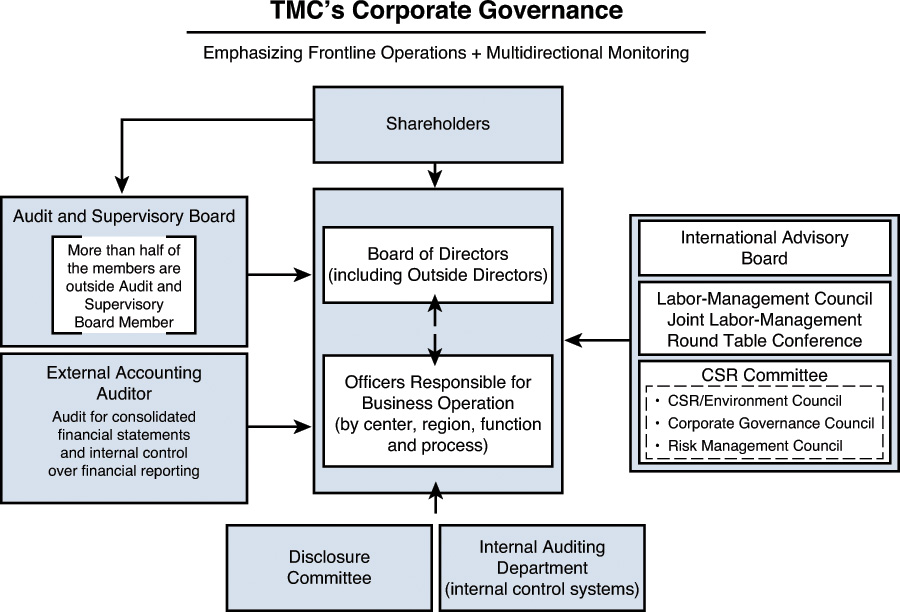

46. Toyota Motor Corporation, Form 6-K, filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission June 29, 2007. One of the guiding precepts of the Toyota Production System, genchi genbutsu, means “go and see for yourself.”

47. Toyota Motor Corporation, “2006 Annual Report,” Accessed June 23, 2008. See http://www.toyota-global.com/investors/ir_library/annual/pdf/2006/, “Toyota Governance.” Accessed November 2, 2010. See http://www.toyota-industries.com/corporateinfo/governance/.

48. Hideaki Miyajima and Keisuku Nitta, “Diverse Evolution of the Traditional Board of Directors: Its Causes and Effects on Performance,” in Corporate Governance—Diversification and Prospects, Kinzai (in Japanese) (2007).

49. TMI Associates and Simmons & Simmons, “Amendments to the Japanese Commercial Code.” Amendment enacted in May 2002, in force as of April 1, 2003 (2003). Accessed April 3, 2015. See www.tmi.gr.jp/english/topic/2003/index.html.

50. Robert Eberhart, “Corporate Governance Systems and Firm Value: Empirical Evidence from Japan’s Natural Experiment,” Journal of Asia Business Studies 6 (2012): 176–196.