11. The Market for Corporate Control

A well-functioning governance system consists of more than a board of directors to provide oversight for the corporation and an external auditor to ensure the integrity of financial reporting. It includes all disciplining mechanisms—legal, regulatory, and market driven—that influence management to act in the interest of shareholders. For example, in Chapter 7, “Labor Market for Executives and CEO Succession Planning,” we examined how a competitive labor market for CEOs puts pressure on management to perform or risk being replaced by another executive, either from within or outside the company, who can deliver better corporate results.

Instead of removing an executive, the board of directors (or in some cases shareholders directly) can decide to transfer ownership of the firm to new owners who will manage its assets more profitably. A change in control involves not only replacing management but also possibly making substantial changes to firm strategy, cost structure, and capital structure. In theory, a change of control makes economic sense only when the value of the firm to new owners, minus transaction costs associated with the deal, is greater than the value of the firm to current owners.1 When this scenario occurs, the acquirer will attempt to purchase the target and capture the resulting economic gains. This general idea is called the market for corporate control.

Of course, the preceding discussion is somewhat simplistic. Clearly, acquisitions also occur for nonstrategic reasons. For example, management might want to increase the scope of operations simply for the sake of managing a larger operation. When this occurs, the acquiring company might receive less in value than it gives up. The management of the acquiring firm might be better off, but the economic impact on shareholders would be considerably less positive. Similarly, the management of the target firm might seek to impede a takeover—even one that makes economic sense—to protect their present jobs. If successful, these actions can lead to inefficiencies in the market for corporate control and can weaken the disciplining effects on managerial performance.

In this chapter, we start by examining the market for corporate control. In general, how beneficial are acquisitions? Do they create or destroy value? Then we examine the steps companies take to protect themselves from unsolicited acquisitions. When is it appropriate for the firm to adopt antitakeover protections? Do they lead to enhanced shareholder value, or are they a source of value-destroying friction?

The Market for Corporate Control

The concept of a market for corporate control was succinctly described by Henry Manne: “The lower the stock price, relative to what it could be with more efficient management, the more attractive the takeover becomes to those who believe that they can manage the company more efficiently.”2 Manne’s thesis was that the price of a company’s stock partly reflects management performance. A low stock price indicates poor management of company assets and provides incentive to outside investors to find alternative sources of capital to acquire the company, replace its management, and maximize its resources for their own gain.

Today we think of the market for corporate control as consisting of all mergers, acquisitions, and reorganizations, including those by a competitive firm, by a conglomerate buyer, or through a leveraged buyout (LBO), management buyout (MBO), or private equity firm. The company that makes the offer is known as the acquirer (or bidder). The company that is the subject of the offer is the target.

An acquisition attempt can either be friendly or hostile. Friendly acquisitions are those in which the target is open to receiving an offer from the acquiring firm. An acquisition might still be considered friendly if the target rejects the initial bid as inadequate but signals that it is willing to negotiate a higher takeover price. Hostile takeovers are those in which the target resists attempts to be acquired at any reasonable price. Management of the target firm might adopt a defense mechanism to protect itself from a takeover, or more likely, it might already have such a mechanism in place that management declines to remove. These are known as antitakeover protections, or antitakeover defenses.

Takeover offers can be structured in three basic forms. A merger occurs when two companies directly negotiate a takeover. Mergers tend to be friendly. A merger is complete when it has been approved by both companies’ boards and shareholders. A tender offer occurs when the acquirer makes a public offer to acquire the shares of the target at a stated price. Tender offers tend to be hostile. In the absence of antitakeover defenses, a tender offer allows a hostile bidder to bypass the target’s board of directors and seek approval directly from shareholders. When antitakeover defenses are in place, a tender offer is combined with a proxy contest. In the proxy contest, the acquirer asks the target shareholders to elect a board proposed by the acquirer to replace the incumbent board. If elected, the new board will disable the antitakeover defenses and allow the acquisition to go forward.3

Acquisitions occur for many reasons. The most frequently cited reason is that the acquiring firm believes it can enhance the profitability of the target company in a manner that the company could not achieve in its existing ownership structure. In this way, the firm’s assets might be worth more to an acquirer than the company as a free-standing entity.4 Examples include these:

• Financial synergies—An acquiring firm believes that it can increase profits through revenue improvements, cost reductions, or vertical integration that comes from combining the two companies’ business lines.

• Diversification—Two companies whose earnings are uncorrelated (for example, because they are in unrelated or countercyclical industries) might benefit by merging because the capital generated when one business is thriving can help the other when it is under pressure. This is the logic behind the conglomerate structure. Conglomerates can also transfer noncash resources, such as management, among divisions.5

• Change in ownership—A new ownership group might be able to improve the profitability of the target through its access to capital, managerial expertise, and other business resources. For example, private equity firms dramatically change the capital structure and incentive plans in the target firm after acquisition (see the following sidebar).

Eckbo (2013) provided an extensive review of the research literature on corporate mergers. He showed that takeover activity enhances production efficiency along the supply chain through consolidation, increased buying power, plant eliminations, more efficient plant operations, and other restructuring activities. He found evidence that large corporations that engage in acquisitions subsequently reduce innovation (investment in research and development); conversely, he found that an active market for corporate control encourages small firms to innovate to increase the probability of becoming takeover candidates. Approximately half of takeovers involving public corporations are initiated by the seller and not by the buyer.6

Companies can also merge for nonstrategic reasons, such as for empire building, management hubris, herding behavior, and compensation incentives. Empire building describes a situation in which the acquiring company’s management seeks to acquire another company primarily for the sake of managing a larger enterprise. Hubris represents overconfidence on the part of management that it can more efficiently utilize the assets of a target to achieve greater revenues or cost savings than current owners can.10 Herding behavior occurs when the senior management team of one company pursues acquisitions because its competitors have recently completed acquisitions.11 Compensation incentives might encourage management to pursue deals that are not in the best interest of shareholders. Management of the acquiring company might pursue a deal because the executives will receive greater compensation for managing a larger enterprise.12 Management of the target company might want to accept a takeover bid because the executives stand to receive large severance or change-in-control payments. According to a study by Equilar, the average CEO stands to receive $29 million in cash and accelerated equity grants following a change in control (see the following sidebar).13

Stock Market Assessment of Acquiring and Target Firms

A vast research literature has examined the market for corporate control and the impact of the acquisitions on corporate performance. Here we summarize some of the basic results.

Who Gets Acquired?

Many researchers have attempted to develop models that predict which companies are likely to become acquisition targets, based on financial and stock price performance.19 Palepu (1986) found some evidence that firms with poor performance, small size, and a need for resources for growth are most likely to be takeover targets. Still, he cautions that it is difficult to predict takeover targets with accuracy.20

Professional studies have also identified attributes that might be common across takeover targets:

• Fundamentally weak performance—The company can be purchased at a low price (relative to assets) and performance can be subsequently improved through managerial changes or capital infusions.

• Companies in an industry with heightened merger activity—Industry groups tend to experience merger activity in waves. An example is the casino industry in the 2000s. A merger wave might be caused by a shift in the marketplace that makes these firms more attractive or encourages consolidation. It might also be driven by psychological factors, such as the herding behavior discussed earlier.

• Low debt levels—Companies with low debt levels have greater financial flexibility. The acquirer can increase the debt levels of the target as part of the financial strategy.

• Strong cash flows—Companies with strong cash flows have greater financial flexibility. Strategic buyers can use internally generated cash flow to fund expansion; private equity buyers can rely on cash flow to support a higher debt burden.

• Valuable assets—The target’s assets might be underutilized, they might be complementary to those of the acquirer, or they might have value that is not readily apparent to public shareholders (such as land, intellectual property, or patents that are not carried on the balance sheet at fair value).21

As mentioned earlier, it is necessary to offer a premium relative to the current stock price in order to convince the target company to accept a deal. As we discussed in Chapter 3, “Board of Directors: Duties and Liability,” the board of directors must evaluate the premium offered in relation to the standalone, long-term value of the company and make a decision that the board members believe is in the interest of shareholders. Eckbo (2009) calculated that the average takeover premium between 1973 and 2002 was about 45 percent (see Figure 11.1).22 Eckbo (2013) found that initial and final takeover premiums are unaffected by whether the target is hostile to the initial bid, the liquidity of the target company’s stock, whether multiple bidders are involved, or whether the takeover is by an acquirer in the same industry or a conglomerate buyer.23

Researchers have also studied the practice of awarding change-of-control payments (golden parachutes) for their implications on takeover activity. Lambert and Larcker (1985) found that the stock market reacts positively to the adoption of a golden parachute provision in the executive employment contract. They suggested that shareholders might view such provisions favorably if they believe it means that a takeover is more likely or that management has greater incentive to negotiate a larger premium in a prospective deal.24 Fich, Tran, and Walkling (2013) studied 851 acquisitions between 1999 and 2007 and found that golden parachutes significantly increase the probability of deal completion; however, they also found that golden parachutes are associated with lower takeover premiums.25 By contrast, Machlin, Choe, and Miles (1993) found that golden parachute provisions significantly increase the likelihood of a takeover and that the size of the payment positively influences the magnitude of the takeover premium. They saw no evidence that such payments are made as a form of rent extraction (that is, if they are awarded only after a deal is already pending) but instead concluded that “golden parachutes encourage managers to pursue shareholder interests.”26

To reduce the likelihood that management pursues a deal simply to realize an accelerated payment, most companies require a “double trigger” before the golden parachute becomes payable: The corporation must undergo a change in control and the executive must be terminated without cause in connection with the deal. According to Equilar, 98 percent of companies that offer cash payments upon a change in control require a double trigger.27

Finally, even successfully negotiated takeovers are often subject to litigation from plaintiffs’ attorneys representing shareholder groups alleging that they did not receive adequate compensation for their shares. These lawsuits typically allege that the target company’s board conducted a flawed sales process that failed to maximize shareholder value. Allegations might include that the process was not sufficiently competitive, that antitakeover protections reduced the deal price, that management or members of the board that negotiated the deal were conflicted (say, due to potential compensation), or that disclosure was inadequate. According to Cornerstone Research, 93 percent of M&A deals valued over $100 million were litigated in 2014. The average number of lawsuits per deal was 4.5. Fifty-nine percent were resolved before the deal closed, and only one went to trial, resulting in $76 million in damages. Eighty percent of settlements required only additional disclosure. Only six involved payments to shareholders.28

Who Gets the Value in a Takeover?

The benefits of a change in ownership are not evenly shared between the acquirer and the target. Research studies routinely have found that the incremental value anticipated by a merger tends to flow predominantly to the target, in the form of a large premium relative to past stock price. Jensen and Ruback (1983) reviewed 12 studies on successful tender offers and acquisitions. They found that target companies exhibit double-digit excess stock price returns between the announcement and consummation of a merger.29 The amount of outperformance varies by the nature of the deal. For example, Servaes (1991) found that companies that are the target of a hostile bid outperform the market by 32 percentage points in the month following the takeover announcement, while companies that agree to a friendly merger outperform by 22 percent.30 Gains also vary by the structure of the deal. Andrade, Mitchell, and Stafford (2001) found that mergers funded with equity result in lower excess returns for target companies than all-cash offers.31

At the same time, the benefits of a change in ownership are decidedly less favorable for the acquirer. Martynova and Renneboog (2008) found that the acquiring firm’s shareholders enjoy no bump up in share price following the announcement of a takeover. Instead, the stock price returns of the acquirer are indistinguishable from those of the general market.32 Studies also show that relative performance depends on the nature of the bid. Goergen and Renneboog (2004) found that hostile takeovers result in worse stock price performance for the acquirer than friendly deals.33 Mergers financed with equity destroy more value for the acquiring firm than mergers financed with cash.34

However, these studies focus on the market’s expectations for the merger based on stock price changes around the announcement date. But what does the evidence say about the long-term economics of deals? The evidence is fairly negative. Studies that measure long-term operating performance (such as earnings-per-share growth or cash flows over a one- to three-year period) largely find that firms tend to underperform their peers following an acquisition.35 In particular, mergers initiated during a wave of activity exhibit below-average long-term performance.36 One obvious explanation is that the acquisition is simply a bad investment in which revenue and cost synergies do not meet expectations. If a target has multiple bids, the acquirer might experience the “winner’s curse,” in which the final bid is actually too high. Acquirers sometimes cut back on investment in working capital and capital expenditures following a deal, actions that can improve cash flow but destroy value. Furthermore, companies that acquire targets within the same industry enjoy no performance advantage over companies that acquire targets from an unrelated industry. Still, some evidence indicates that acquisitions financed with cash perform better than acquisitions financed with equity.37

Although much attention is paid to the economics of a merger, the merger process itself is equally important. Proposed mergers can be highly disruptive to both the target and the acquirer. This is particularly true of hostile takeover attempts, in which considerable resources are expended to mount or defend an unsolicited bid. The bidder must acquire a list of shareholders, contact major shareholders to assess their willingness to sell, and mail proxy materials to all parties. For its part, the target must contact shareholders and convince them not to sell. If the target believes that the threat is credible, it might engage in value-destroying behaviors to thwart the acquisition. All these actions detract from a focus on running day-to-day operations, and boards need to be especially diligent during these activities (see the following sidebar).

Even successful deals result in considerable turmoil for the acquirer. For example, takeovers commonly lead to layoffs as acquirers seek to capture operating efficiencies by reducing labor expenses. Takeovers also lead to executive turnover as management teams are integrated. Krug and Shill (2008) found that executive turnover rates double following an acquisition and that executive turnover remains elevated for 10 years. The authors noted that “long-term leadership instability . . . should be viewed as potentially harmful to integration and long-term performance.”40 Other studies have suggested that how well a company manages the integration process is a key determinant of whether a merger will ultimately generate economic benefits to the acquirer.41

Based on the evidence, considerable debate arises over whether acquisitions are a good idea for the acquiring firm. Consensus seems to have formed that the value of deals generally flows to shareholders of the target firm. Furthermore, experience shows that the surviving firm often fails to realize economic value. As a result, the board should carefully consider whether to allow management to complete large acquisitions. Although in some examples such deals lead to substantial value creation, the average results (discussed earlier) are considerably less compelling for shareholders.

On the other hand, target companies often go through considerable effort to protect themselves from being acquired. Why this is so, given the potential economic returns that target shareholders stand to receive, remains a question. In the second half of this chapter, we consider the actions that targets take to defend themselves from an unsolicited offer and the impact of these actions on shareholder value.

Antitakeover Protections

A company that does not want to become the target of an unsolicited takeover can adopt defense mechanisms that discourage or dissuade potential bidders from making a formal offer. Several important economic reasons justify doing so:

• Preservation of long-term value—A company with attractive future growth prospects that is selling at a depressed market price might want to prevent another company from making a bid at artificially low prices. For example, the firm might have developed a new technology but has chosen not to disclose this information to the public for competitive reasons. The current stock price will not reflect the value of this innovation. By remaining independent, the company will have time to commercialize this technology and deliver long-term value to current shareholders.

• Acquirer myopia—A company that is protected from unsolicited takeovers has greater flexibility to pursue risky, long-term projects that offer attractive future gains. Management is able to make investments with positive net present value that depress current earnings, without having to worry about being taken over before those investments have had time to pay off.

• Enhanced bargaining power—When a company implements antitakeover protections, a potential acquirer is more likely to be compelled to engage management rather than make a hostile bid. This increases management’s negotiating leverage and offers the target the opportunity to secure a higher deal price.

However, antitakeover provisions can also be a manifestation of agency problems, such as management entrenchment. An entrenched management is one that erects barriers to retain its position of power and insulate itself from market forces. An entrenched management is able to extract rents from the company (through continued employment or excessive compensation and perquisites) when these are not merited based on performance.

The board must determine whether antitakeover provisions are truly in the interest of shareholders. Even with antitakeover protections in place, the board of directors has a fiduciary obligation to weigh all offers—both friendly and hostile.

Antitakeover Actions

The most common antitakeover defense is the poison pill—also known as a shareholder’s rights plan. Many companies have this defense in place on an ongoing basis, but even those that do not can adopt one at any time without delay and without shareholder approval.42 When triggered, poison pills have the potential to grant holders of the company’s shares the right to acquire additional shares at a deep discount to fair market value (such as $0.01 per share). The poison pill is triggered if a shareholder or shareholder group accumulates an ownership position above a threshold level (typically 15 to 20 percent of shares outstanding). Once this threshold is exceeded, the market is flooded with new shares that dilute the would-be acquirer’s shareholdings and make it prohibitively expensive for the acquirer to take control of the firm through open market purchases or a tender offer. The effect is so severe that no acquirer will trigger the pill; instead, it will pressure the target board to disable the pill and allow the acquisition to go forward. At the same time, the acquirer will launch a proxy contest to replace the incumbent board with a board that is friendly to the deal and will disable the pill.43

A second layer of antitakeover defenses include those that prevent a hostile acquirer from replacing the incumbent board. The strongest protection is dual-class stock, which gives a controlling shareholder or management enough votes to control board elections. As explained in Chapter 3, a company with dual-class shares has more than one class of common stock. Each class is afforded a different set of voting rights even though they are otherwise economically equivalent. For example, Class A shareholders might have 10 times as many votes per share as Class B shareholders. The class of shares with more generous voting rights typically is not publicly traded, but is held by an insider, the founding family, or another shareholder that is friendly to management. A dual-class share structure means that a corporate raider can accumulate a majority economic stake in a company but still not have majority voting control to replace the board.

A company might also restrict the ability of shareholders to replace the incumbent board by adopting a staggered board, or classified board. As discussed in Chapter 3, with a staggered board, directors typically are grouped into three classes, each of which is elected to a three-year term. Only one class of directors stands for reelection in a given year. A staggered board structure prevents a corporate raider from gaining majority control of a board in a single year. Any proxy contest to have board members removed must be waged over at least a two-year period. The coupling of a poison pill with a staggered board is a very formidable antitakeover defense.

A company with an annually elected board might protect itself by restricting the ability of shareholders to replace the incumbent board between annual meetings. This is achieved through charter provisions that both restrict shareholder rights to call a special meeting (in which the vote would occur) and prohibit shareholders from voting by written consent (in which shareholders who are unable to meet physically can still vote on a matter). If either of these avenues is available to the target’s shareholders, it can be used to hold an election in which the incumbent board is replaced. Still, these defenses are weaker than those described earlier because they only protect the incumbent board until the next annual meeting.

Finally, the state of a target’s incorporation might provide takeover defenses by statute. However, as discussed in Chapter 3, expanded constituency provisions are limited in the protections they afford.

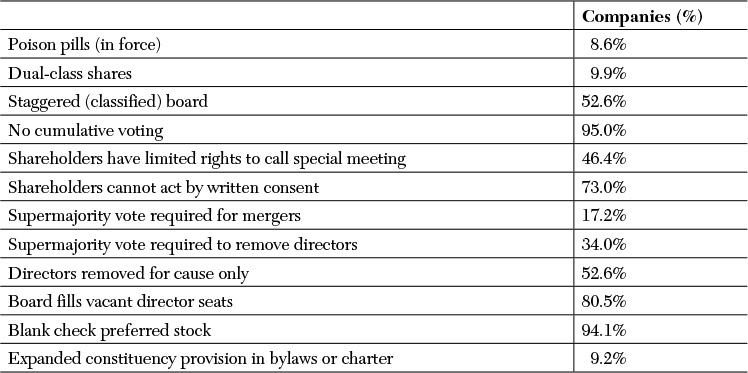

The vast majority of U.S. corporations have adopted some level of protection. Among companies in the Russell 2000, 53 percent have a staggered board, 10 percent have multiple classes of shares with unequal voting rights, and 9 percent have a poison pill protection in place. Seventy-three percent do not allow shareholder action by written consent, and 46 percent have limited shareholder rights to call a special meeting (see Table 11.1).44

Source: Computed using 2014 data for 1,871 companies in the Russell 2000 Index covered by SharkRepellent, FactSet Research Systems, Inc.

Table 11.1 Antitakeover Protections

The question for the board is, should the company implement antitakeover protections? In the following sections, we examine the research on four common defense mechanisms: poison pills, staggered boards, state of incorporation, and dual-class shares. We consider whether these protections are successful in deterring takeovers and what impact they have on governance quality.

Poison Pills

As explained earlier, poison pills are very effective at stopping a hostile takeover (particularly when they are combined with a staggered board). The poison pill defense was first used in 1982 by General American Oil to prevent a hostile takeover by T. Boone Pickens. The defense was ruled legal in 1985 by the Delaware Supreme Court and subsequently has been imitated by numerous other firms.45 A poison pill might also be adopted to delay a takeover bid and give additional companies time to come forward with a competing bid. In rare cases, a poison pill can be adopted to limit the ownership stake and influence of an activist investor that might agitate for a sale of the company. For example, in 2013, Sotheby’s adopted a unique poison pill that limited passive investors such as mutual funds to a 20 percent ownership level and activist shareholders to a 10 percent level.46

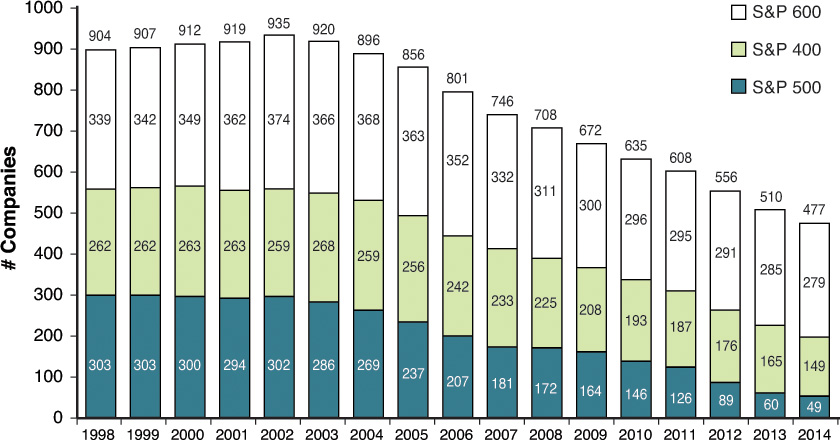

In recent years, many companies in the United States have dropped their poison pills. According to data from SharkRepellent, the number of companies that had a poison pill fell by 85 percent between 2004 and 2014 (see Figure 11.2).47 But as explained earlier in this chapter, a firm can adopt a poison pill quickly after a takeover attempt has become known. To this end, some companies that have eliminated their poison pills have expressly reserved the right to adopt a plan in the future. Some shareholder groups, however, have moved to limit this right by requiring that any new plan be subject to shareholder approval.48

Source: Adapted from SharkRepellent, FactSet Research Systems, Inc.

Figure 11.2 S&P 1500 poison pills in force at year end (including non-U.S. incorporated companies).

Institutional investors take a mixed view on poison pills. The AFL-CIO supports “the legitimate use of shareholder plans,” with the stipulation that its support applies only as long as “shareholders [are] given the opportunity to vote on these plans.”49 Morgan Stanley Investment Management votes “case-by-case on whether the company has demonstrated a need for the defense in the context of promoting long-term shareholder value; whether provisions of defense are in line with generally accepted governance principles [ . . . ]; and specific context if the proposal is made in the midst of a takeover bid or contest for control.”50 By renewing poison pills with a periodic vote, shareholders are able to cast their opinion on whether the provision provides legitimate economic protection or acts as management entrenchment.

Cremers and Ferrell (2014) found that poison pills have a negative relationship with firm value, as measured by market-to-book value ratios. They estimated that firm value decreases by 5 percent upon the adoption of a pill.51

Brickley, Coles, and Terry (1994) found that the market reacts positively to the adoption of a poison pill if the company’s board has a majority of outside directors and negatively if the board does not have a majority of outside directors. They concluded that shareholders view poison pills as protecting their economic interests if the board is independent and that they view poison pills as entrenching management when insiders control the board.52 Ryngaert (1988) reached a similar conclusion. He found no statistically significant reaction to the adoption of a poison pill across a broad sample of firms. However, among firms perceived to be takeover targets, he found a significant negative reaction. He also found that stock prices fall an average 2.2 percent when the plan is upheld in court and rise 3.4 percent when the plan is ruled invalid.53

Poison pills are generally effective in preventing unsolicited takeovers. Ryngaert (1988) found that companies that implement a poison pill are twice as likely to defeat an unsolicited offer as companies without a poison pill.54 Furthermore, companies with a poison pill in place ultimately agree to takeover premiums that are roughly 5 to 10 percent higher.55 These statistics are somewhat misleading, however, because they fail to take into account the decline in stock price that takes place when a company successfully uses a poison pill to defeat an unsolicited takeover. Ryngaert (1988) found that companies that defeat an offer experience market-adjusted declines of 14 percent.56 That is, poison pills tend to reward shareholders if the bid is successful, but not if it fails.

Poison pills have extensive history in the United States but are less common in other countries. For example, in Japan, unsolicited takeovers have generally not occurred, and so Japanese companies have not had to adopt poison pills. In recent years, however, with the growth of global capital markets, international investors have pressured Japanese managers to take aggressive actions to improve performance. This has encouraged the adoption of poison pills among Japanese companies to preserve their autonomy. It also reflects the tensions that can occur when Western styles of capitalism are applied to countries with different societal values (see the following sidebar).

Staggered Board

Staggered boards pose an obstacle to hostile takeover attempts, in that a corporate raider cannot gain control of the board in a single year through a proxy contest. Instead, the raider must win at least two elections, one year apart from each other, to gain majority representation. Although it is not impossible, winning two consecutive elections is significantly more costly and less likely to succeed (the corporation has the opportunity to quell shareholder dissatisfaction in the intervening year).59 In recent years, the use of staggered boards has dramatically decreased. In 2004, approximately 900 of the S&P 1500 had a staggered board; by 2014, this figure had decreased to 477 (see Figure 11.3).60

Source: Adapted from SharkRepellent, FactSet Research Systems, Inc.

Figure 11.3 S&P 1500 staggered (classified) boards (including non-U.S. incorporated companies).

Board classification is a significant deterrent to unsolicited takeovers. Bebchuk, Coates, and Subramanian (2002) examined merger activity between 1996 and 2000 and found no instances of a corporate raider gaining control of a staggered board through a proxy contest. Furthermore, they found that companies with a staggered board are significantly more likely to defeat an unsolicited bid and remain independent (61 percent versus 34 percent of companies with a single-class board). At the same time, companies with a staggered board that do get acquired receive a premium that is fairly similar to those with a single-class board (54 percent versus 50 percent). The authors concluded that the staggered board structure does not “provide sufficiently large countervailing benefits to shareholders of hostile bid targets, in the form of higher deal premiums, to offset the substantially lower likelihood of being acquired.”61

Pound (1987) reached similar conclusions. He examined a sample of 100 companies with staggered boards and supermajority provisions (companies with supermajority provisions require that mergers be approved by more than half of shareholders, typically 66 percent to 80 percent). He found that 28 percent of companies with these protections receive takeover bids, compared with 38 percent for a control sample without these protections. He also found that companies with these provisions that ultimately accept the bid do not receive a significantly higher premium to compensate for the lower likelihood of acquisition (51 percent vs. 49 percent). He, too, concluded that “these amendments increase the bargaining power of management . . . to the detriment of shareholder wealth.”62

Guo, Kruse, and Nohel (2008) found that the announcement to destagger is associated with about a 1 percent increase in stock price. They also found that firms that are considered to have good governance are more inclined to drop the staggered structure.63 Faleye (2007) found that staggered boards are associated with lower CEO turnover, less CEO pay-performance sensitivity, and lower likelihood of proxy contests or shareholder proposals.64

Research evidence, however, is not uniformly negative. Cremers, Litov, and Sepe (2014) examined the effect of staggering and destaggering boards using a time series analysis rather than cross-section analysis, over the time period 1978 to 2011. They found that the adoption of a staggered board is associated with a subsequent increase in firm market-to-book value and destaggering is associated with a decrease in value.65 Ge, Tanlu, and Zhang (2014) examined destaggering transactions in recent years, motivated by activist shareholders, and found that they do not lead to improved performance and might lead to worse outcomes.66 Consistent with these findings, Larcker, Ormazabal, and Taylor (2011) examined the market reaction to proposed regulations that would bar staggered boards and found that firms with staggered boards suffered a negative market response to these proposals.67

Staggered boards therefore are likely to have positive as well as negative implications for shareholders, depending on the situation. Staggered boards afford greater independence to outside directors who can take a long-term perspective without pressure from management or shareholders. For this reason, staggered boards remain a prominent feature of innovative and fast-growing companies, including newly issued IPO companies. At the same time, a clear risk exists that board classification insulates directors from shareholder pressure and reduces director accountability by reducing the frequency of elections. For this reason, many institutional shareholders oppose staggered boards. For example, in 2013, shareholder-sponsored proposals to destagger boards were voted on for 29 companies; 26 of these passed, and average support was 80 percent.68

State of Incorporation

Approximately 60 percent of publicly traded companies in the United States are incorporated in the state of Delaware.69 The rest are predominantly incorporated in the state in which they were founded or are headquartered. The state of incorporation is important because state law dictates most corporate governing rights. A company that faces the threat of a hostile bid can reincorporate in a state with more protective antitakeover laws. For example, Barzuza (2009) provided a review of state antitakeover laws and found that, whereas Delaware tends to have laws that protect shareholder value, at least some states have entered into a “race to the bottom” by allowing very restrictive protections.70

Most institutional investors oppose reincorporation for the purpose of protecting the firm from an unsolicited bid. They view this as an attempt to expand the powers of the board at the expense of shareholders, whose rights are curtailed. To this end, activist investor Carl Icahn has proposed that shareholders be given greater say over the matter with “a federal law that allows shareholders to vote by simple majority to move their company’s incorporation to another state.”71

State law can have an important impact on governance quality. Shareholders view restrictive state laws as negative. For example, Szewczyk and Tsetsekos (1992) measured the impact of the Pennsylvania Senate Bill (PA-SB 1310), which added significant new protections for Pennsylvania-based firms. Under PA-SB 1310, the following holds:

• Directors can consider the short-term and long-term impact on all stakeholders in their assessment of a takeover proposal. This provides considerably more flexibility than a focus on maximization of shareholder value, which is primarily achieved through takeover premium.

• Voting rights of shareholders who control 20 percent or more of the stock are removed until a majority of disinterested shareholders vote to restore their votes. As a result, a corporate raider who accumulates a significant position is not allowed to vote on his or her own takeover proposal unless other shareholders allow this.

• Profits realized by a control group from the disposition of equity within 18 months of obtaining control status are disgorged. This prohibits a raider from driving up the price of a stock and then dumping shares for a short-term gain.

• Severance (up to 26 weeks) must be provided to any employee terminated within 24 months after a change in control.

• An acquirer cannot terminate existing labor contracts after a change in control.

• However, firms can opt out of some or all of these provisions.

Szewczyk and Tsetsekos (1992) tracked the share price performance of a sample of Pennsylvania-based firms from the day PA-SB 1310 was first introduced in the state senate until it was signed into law six months later. They found that these firms performed significantly worse than a comparable sample of firms incorporated outside Pennsylvania. Based on the abnormal change in stock prices over the measurement period, the sample of Pennsylvania firms lost nearly $4 billion in market value through the enactment of the law. Furthermore, companies that subsequently chose to opt out of some or all of the provisions of PA-SB 1310 experienced significant positive stock price returns on the day of the announcement. The authors attributed “this favorable share price response to the firms’ reaffirmation of the fiduciary responsibility of their directors to shareholders.”72

Similarly, Subramanian (2003) examined whether companies are compensated for restrictive antitakeover laws through higher buyout premiums if the bid is ultimately successful. He found that companies incorporated in states with high takeover protections do not receive premiums that are significantly higher than companies incorporated in states with low takeover protections. He concluded that restrictive state laws do not increase the bargaining power of management relative to potential bidders.73

Dual-Class Shares

A company with dual-class shares has more than one class of common stock. In general, each class has proportional ownership interests in the company but disproportionate voting rights. The difference between the economic interest and voting interest of the classes is known as the wedge. (For example, if Class A has 10 percent economic interest and 30 percent voting interest, the wedge is 20 percent.) The class with favorable voting rights typically does not trade in the public market but is instead held by an insider, the founding family, or another shareholder that is friendly to management.

In a dual-class share structure, a corporate raider can accumulate a majority economic stake in a company but still not have majority voting control. For example, prior to its sale to News Corp., the Dow Jones Company had two classes of stock: Class A shares, which were publicly traded, and Class B shares, which were privately held by the Bancroft family. Shareholders of Class A and Class B were afforded equal ownership interests in terms of their rights to profits, dividends, and a claim on company assets. However, Class B shareholders were granted ten times as many votes per share as Class A shareholders. This meant that even though the Bancrofts had less than a 10 percent ownership interest, they still controlled 64 percent of the votes (a wedge of 54 percent). The only way for News Corp. to succeed with its unsolicited offer was to convince members of the Bancroft family to vote in favor of the deal.74

Most institutional investors oppose dual-class shares. Morgan Stanley Investment Management proxy guidelines state that it “generally supports management and shareholder proposals aimed at eliminating unequal voting rights, assuming fair economic treatment of classes of shares held.”75 Likewise, proxy advisory firm Institutional Shareholder Services votes “against proposals to create a new class of common stock with superior voting rights” and “votes against proposals at companies with dual-class capital structures to increase the number of authorized shares of the class of stock that has superior voting rights.”76 These positions are understandable, in light of the fact that institutional owners generally own the shares with inferior voting rights.

In some circumstances, it might make sense to create dual-class stock. For example, a high-growth firm might want to raise capital to pursue a promising new project but might not want to issue straight common stock for fear of giving up too much voting control (that is, the firm does not mind giving up a substantial economic interest to invest in the project but is concerned about losing control over the project to new investors). As a result, the company might decide to issue new stock in a separate class of shares with inferior voting rights. Companies might also opt for a dual-class structure to preserve the independence of management and the board. This is particularly the case when the company’s founder retains a considerable ownership stake in the company. For example, several prominent technology companies with large founder ownership such as Alibaba, Facebook, and Google all elected to have more than one share class following their initial public offerings (see the following sidebar).

The evidence suggests that companies with dual-class shares tend to have lower governance quality. Masulis, Wang, and Xie (2009) examined the relationship between dual-class share structure and shareholder response to company behavior in terms of acquisitions, CEO compensation, cash levels, and capital expenditures. On average, insiders at the companies in the study held 67.4 percent of the voting rights, compared with only 40.8 percent of the economic rights (the wedge was 26.6 percent). The authors found that public shareholders respond negatively and are skeptical about the economic merits of an acquisition announcement. Furthermore, the authors found that as the size of the wedge increases, CEO compensation is higher, shareholders believe that large cash holdings are more likely to be put to uneconomic use, and shareholders place less value on large capital expenditures. The authors concluded that the evidence was “consistent with the hypothesis that insiders holding more voting rights relative to cash flow rights extract more private benefits at the expense of outside shareholders.” That is, companies with dual-class shares are more likely to have agency problems than those with a single share class.80 Gompers, Ishii, and Metrick (2010) reached a similar conclusion.81

Warding Off Unwanted Acquirers

Research demonstrates that antitakeover protections generally reduce governance quality and shareholder value. They do so by increasing the transaction costs associated with a successful acquisition and by shielding management from the disciplining mechanism of otherwise efficient capital markets. However, as we have seen, some evidence also shows appropriate uses for antitakeover provisions.

Daines and Klausner (2001) provided a useful summary that ranks antitakeover protections by their level of protectiveness (from most difficult to least difficult to acquire):

1. Companies that have either dual-class shares or staggered boards and prohibitions on shareholder rights to call special meetings or act by written consent

2. Companies with staggered boards but no limitations on shareholder rights to call special meetings or act by written consent

3. Companies with annually elected boards but prohibitions on shareholder rights to call special meetings or act by written consent

4. Companies with annually elected boards and full shareholder rights to call a special meeting or act by written consent

5. Companies with no antitakeover provisions82

Similarly, Klausner (2013) reviewed the empirical evidence on antitakeover protections in IPO charters and concluded that “the idea that more takeover defenses means greater insulation against the takeover threat [ . . . ] is not true. Once a company has a staggered board, additional defenses provide no protection at the margin, and even in companies without staggered boards multiple defenses are generally redundant.”83

The key issue for the board is to determine whether maintaining control over the corporation or fighting a takeover attempt is in the best interest of shareholders. Unfortunately, the research literature on this topic is mixed. Atanassov (2013) found that antitakeover provisions lead to management entrenchment and less pressure on companies to innovate: Stronger antitakeover protections are associated with a decline in patent filings and citations.84 Bhojraj, Sengupta, and Zhang (2014), however, found the opposite to be true: Innovative companies with strong protections are less likely to engage in myopic activities such as reducing research and development expenditures and filing fewer patents. They concluded that “In contrast to prior research that predominantly documents evidence of harmful effects of antitakeover provisions (ATPs) on average, we show that ATPs can provide benefits to a subset of firms.”85

Similarly, the research on whether a company benefits by resisting a hostile takeover is fairly inconclusive. Bradley, Desai, and Kim (1983) found that companies that reject a takeover offer and are not subsequently taken over lose all the stock price gains earned prior to the announcement.86 Similarly, Safieddine and Titman (1999) found that firms rejecting a takeover on the basis that the offer “is insufficient” experience a 3.4 percent stock price decline on the announcement date.87 Nevertheless, if the target company is truly committed to increasing shareholder value, evidence shows that they can successfully do so. Safieddine and Titman (1999) find that target firms that increase their leverage after rejecting a bid outperform similar firms by about 40 percent over the following five years, whereas firms that do not increase their leverage underperform similar firms by about 25 percent over this time period. That is, the greater debt load gives management incentive (and demonstrates management’s commitment) to increasing cash flow and shareholder value.88 Thus, important contextual elements seem to contribute to whether stock prices rise or decline after a rejected takeover. Nevertheless, boards should consider the very real possibility that the stock price for their firm might never recover following a successful takeover defense (see the following sidebar).

In evaluating antitakeover protections, shareholders and board members might consider several issues. First, how important is the market for corporate control as a disciplining mechanism in the firm-specific governance structure? Perhaps other features of the corporate governance system are sufficient to mitigate agency problems. Second, what are the motives of potential acquirers? Are these motives consistent with the long-term shareholder or stakeholder objectives of the company? Finally, are the antitakeover provisions truly adopted to protect shareholder interests, or are they a manifestation of “entrenched management”?

Endnotes

1. Transaction costs can be substantial. The various parties bidding for RJR Nabisco racked up $203 million in investment banking fees before KKR ultimately emerged as the winner, taking the firm private in 1988.

2. H.G. Manne, “Mergers and the Market for Corporate Control,” Journal of Political Economy 73 (1965): 110–120.

3. On average, 60 proxy contests were initiated at U.S. public companies each year for the period 2001–2005 and 112 for the period 2006–2010. See Warren S. De Wied, “Proxy Contests,” Practical Law: The Journal (November 2010).

4. Note that this is not inconsistent with efficient markets. The market price of the firm can be correct as a free-standing entity, even though the sale of the firm to a different owner can still merit a substantial premium because it can more effectively use the assets.

5. Many researchers question the logic behind this argument. They argue that if shareholders value diversification, they can achieve it on their own through a diversified stock portfolio. To this end, the research literature has shown that companies organized in a conglomerate structure trade at a discount to a portfolio of similar monoline companies that exist as standalone entities.

6. B. Espen Eckbo, “Corporate Takeovers and Economic Efficiency,” ECGI Finance Working Paper No. 391/2013; Tuck School of Business Working Paper No. 2013-122, Social Science Research Network, (October 15, 2013). Accessed May 5, 2015. See http://ssrn.com/abstract=2340754.

7. Steven N. Kaplan and Antoinette Schoar, “Private Equity Performance: Returns, Persistence, and Capital Flows,” Journal of Finance 60 (2005): 1791–1823.

8. Shourun Guo, Edith S. Hotchkiss, and Weihong Song, “Do Buyouts (Still) Create Value?” Journal of Finance 66 (2011): 479–517.

9. Kaplan and Schoar (2005).

10. Jeffrey Pfeffer, “Curbing the Urge to Merge,” Business 2.0 (2003): 58.

11. Researchers have long noted that acquisitions occur in waves. See Michael Gort, “An Economic Disturbance Theory of Mergers,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 83 (1969): 624–642.

12. As we saw in Chapter 8, “Executive Compensation and Incentives,” the size of compensation packages tends to be correlated with company size. It is commonly alleged that this correlation encourages managers to seek growth via acquisitions. Lambert and Larcker (1987) and Avery, Chevalier, and Schaefer (1998) did not find this simple relationship to be true. By contrast, Fich, Starks, and Yore (2014) found that CEO compensation is positively related to deal activity. See Richard A. Lambert and David F. Larcker, “Executive Compensation Effects of Large Corporate Acquisitions,” Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 6 (1987): 231–243; Christopher Avery, Judith A. Chevalier, and Scott Schaefer, “Why Do Managers Undertake Acquisitions?” An Analysis of Internal and External Rewards for Acquisitiveness.” Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization 14 (1998): 24–43; and Eliezer M. Fich, Laura T. Starks, and Adam S. Yore, “CEO Deal-Making Activities and Compensation,” Journal of Financial Economics 3 (2014): 471–492.

13. Equilar Insight, “Executive Compensation Trends—June: CEO Exit Packages, Fortune 200 CEO Severance & Change-in-Control Packages” (2007).

14. Carol Loomis, “Sandy Weill’s Monster,” Fortune (April 16, 2001).

15. “Mega-Merger Mania Strikes U.S. Banks,” The Banker (May 1, 1998).

16. Janice Revell, “Should You Bet on the CEO?” Fortune 146 (November 18, 2002): 189–191.

17. Avery Johnson and Ron Winslow, “Drug Industry Shakeout Hits Small Firms Hard,” Wall Street Journal (March 10, 2009, Eastern edition): A.12.

18. Mark Maremont, “No Razor Here: Gillette Chief to Get a Giant Payday,” Wall Street Journal (January 31, 2005, Eastern edition): A.1.

19. Michael A. Simkowitz and Robert J. Monroe, “A Discriminant Analysis Function for Conglomerate Targets,” Southern Journal of Business (November 1971): l–16. Donald L. Stevens, “Financial Characteristics of Merged Firms: A Multivariate Analysis,” Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 8 (1973): 149–158. A. D. Castagna and Z. P. Matolcsy, “Financial Ratios as Predictors of Company Acquisitions,” Journal of the Securities Institute of Australia (1976): 6–10. Ahmed Belkaoui, “Financial Ratios as Predictors of Canadian Takeovers,” Journal of Business Finance and Accounting 5 (1978): 93–108. J. Kimball Dietrich and Eric Sorensen, “An Application of Logit Analysis to Prediction of Merger Targets,” Journal of Business Research 12 (1984): 393–402.

20. Krishna G. Palepu, “Predicting Takeover Targets: A Methodological and Empirical Analysis,” Journal of Accounting and Economics 8 (1986): 3–35.

21. Paul Tracy, “How to Find Probable Takeover Targets,” StreetAuthority Market Advisor (February 1, 2007). Accessed November 14, 2010. See http://web.streetauthority.com/cmnts/pt/2007/02-01-takeover-candidates.asp.

22. B. Espen Eckbo, “Bidding Strategies and Takeover Premiums: A Review,” Journal of Corporate Finance 15 (2009): 149–178.

23. Eckbo (2013).

24. Richard A. Lambert and David F. Larcker, “Golden Parachutes, Executive Decision Making, and Shareholder Wealth,” Journal of Accounting and Economics 7 (1985): 179–203.

25. Eliezer M. Fich, Anh L. Tran, and Ralph A. Walkling, “On the Importance of Golden Parachutes,” Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 48 (2013): 1717–1753.

26. Judith C. Machlin, Hyuk Choe, and James A. Miles, “The Effects of Golden Parachutes on Takeover Activity,” Journal of Law and Economics 36 (1993): 861–876.

27. Equilar, “Equilar Study: Change-in-Control Cash Severance Analysis Findings from a Study of Change-in-Control Payments at Fortune 100 Companies” (2011). Accessed May 5, 2015. See http://www.globalequity.org/geo/node/3231.

28. Cornerstone Research, “Shareholder Litigation Involving Acquisitions of Public Companies: Review of 2014 M&A Litigation” (2015). Accessed April 1, 2015. See https://www.cornerstone.com/GetAttachment/897c61ef-bfde-46e6-a2b8-5f94906c6ee2/Shareholder-Litigation-Involving-Acquisitions-2014-Review.pdf.

29. Michael C. Jensen and Richard S. Ruback, “The Market for Corporate Control: The Scientific Evidence,” Journal of Financial Economics 11 (1983): 5–50.

30. Two explanations for this exist. In a hostile takeover, the acquirer is required to offer a more attractive price to overcome the target’s objections to the merger and to persuade shareholders to accept the offer. Hostile bids are also likely to trigger a bidding war if the target seeks a friendly merger partner or more attractive terms. See Henri Servaes, “Tobin’s Q and Gains from Takeovers,” Journal of Finance 46 (1991): 409–419.

31. Gregor Andrade, Mark Mitchell, and Erik Stafford, “New Evidence and Perspectives on Mergers,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 15 (2001): 103–120.

32. Marina Martynova and Luc Renneboog, “A Century of Corporate Takeovers: What Have We Learned and Where Do We Stand?” Journal of Banking and Finance 32 (2008): 2148–2177.

33. Mark Goergen and Luc Renneboog, “Shareholder Wealth Effects of European Domestic and Cross-border Takeover Bids,” European Financial Management 10 (2004): 9–45.

34. Martynova and Renneboog (2008).

35. Ibid.

36. Ran Duchin and Breno Schmidt, “Riding the Merger Wave: Uncertainty, Reduced Monitoring, and Bad Acquisitions,” Journal of Financial Economics 107 (2013): 69–88.

37. Aloke Ghosh, “Does Operating Performance Really Improve Following Corporate Acquisitions?” Journal of Corporate Finance 7 (2001): 151–178.

38. Joseph Walker, Michael Calia, and David Benoit, “Allergan Rejects Valeant Takeover Bid,” Wall Street Journal (May 13, 2014, Eastern edition): B.3.

39. Jonathan D. Rockoff, Liz Hoffman, and David Benoit, “Actavis Offers $66 Billion for Allergan: Secret Talks, Aliases, Ski Cap as Disguise,” Wall Street Journal (November 18, 2014, Eastern edition): B.1–B.5.

40. Jeffrey A. Krug and Walt Shill, “The Big Exit: Executive Churn in the Wake of M&As,” Journal of Business Strategy 29 (2008): 15–21.

41. “Executive Agenda: Not So Fast,” A.T. Kearney 8 (2005): 1–13. Accessed April 11, 2015. See http://gillisjonk.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/EA2005Not_So_Fast.pdf.

42. It is easiest for a company to adopt a poison pill if its charter authorizes blank check preferred stock. Preferred stock is a class of stock that is senior to common stock shareholders in terms of credit and capital. A target can protect itself from a corporate raider by issuing preferred stock with special voting rights to a friendly company or investor (white knight). The authorization of preferred stock has a similar effect as issuing dual-class shares. Blank check preferred stock is a class of unissued preferred stock that is provided for in the articles of incorporation and that the company can issue when threatened by a corporate raider.

43. Cross-holdings can also be an effective deterrent to a takeover. Cross-holdings generally occur between companies that have close interrelation along the supply chain. This practice protects firms by having a friendly, passive shareholder that is sympathetic to present management. Cross-holdings are prevalent in several countries, such as the keiretsu of Japan (see Chapter 2, “International Corporate Governance”).

44. Antitakeover protections computed using 2014 data for 1,871 companies in the Russell 2000 Index, SharkRepellent, FactSet Research Systems, Inc.

45. Money-Zine, “Poison Pill Defense” (2009). Accessed November 14, 2010. See www.money-zine.com/Investing/Stocks/Poison-Pill-Defense/.

46. Sotheby’s, Form 8-K, filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission October 4, 2013.

47. SharkRepellent, “S&P 1500 Poison Pills in Force at Year End 1998–2014,” SharkRepellent, FactSet Research Systems, Inc. (2015.). Accessed March 26, 2015. See www.sharkrepellent.net.

48. Robert Schreck, “Inside M&A: Poison Pill Redux—Now More Than Ever,” McDermott Will & Emery (May/June 2008). Accessed April 12, 2015. See http://www.mwe.com/publications/uniEntity.aspx?xpST=PublicationDetail&pub=4777&PublicationTypes=d9093adb-e95d-4f19-819a-f0bb5170ab6d.

49. AFL-CIO, “Exercising Authority, Restoring Accountability: AFL-CIO Proxy Voting Guidelines” (2012). Accessed April 3, 2015. See http://www.aflcio.org/content/download/12631/154821/proxy_voting_2012.pdf.

50. Morgan Stanley, “2013 Investment Management Proxy Voting Policy And Procedures” (October 3, 2013). Accessed April 3, 2015. See https://materials.proxyvote.com/Approved/99999Z/20140812/other_217038.pdf.

51. Martijn Cremers and Allen Ferrell, “Thirty Years of Shareholder Rights and Firm Value,” Journal of Finance 69 (2014): 1167–1196.

52. James A. Brickley, Jeffrey L. Coles, and Rory L. Terry, “Outside Directors and the Adoption of Poison Pills,” Journal of Financial Economics 35 (1994): 371–390.

53. Michael Ryngaert, “The Effect of Poison Pill Securities on Shareholder Wealth,” Journal of Financial Economics 20 (1988): 377–417.

54. Ibid.

55. John Laide, “Poison Pill M&A Premiums,” SharkRepellent, FactSet Research Systems, Inc. (2005). Accessed March 21, 2009. See www.sharkrepellent.net/pub/rs_20050830.html.

56. Ryngaert (1988).

57. Hiroyuki Kachi and Jamie Miyazaki, “In Japan, Activists May Find Poison,” Wall Street Journal (August 8, 2007, Eastern edition): C.2.

58. Andrew Morse and Sebastian Moffett, “Japan’s Companies Gird for Attack; Fearing Takeovers, They Rebuild Walls; Rise of Poison Pills,” Wall Street Journal (April 30, 2008, Eastern edition): A.1.

59. Air Products and Chemicals attempted to circumvent this obstacle in its purchase attempt of competitor Airgas. In 2010, Air Products made an unsolicited offer to purchase Airgas for $5.5 billion. Airgas rejected the offer. Air Products waged a proxy contest and successfully gained three board seats on Airgas’s board at the annual meeting held September 2010. At that same meeting, shareholders approved a bylaw amendment that brought forward the next annual meeting to January 2011, thereby allowing Air Products to run three more board candidates just 4 months later. Airgas sued, claiming that a 12-month wait was required between meetings. While a Delaware Chancery Court upheld the bylaw amendment, the Delaware Supreme Court reversed the lower court’s decision, ruling instead that directors had been elected under the company’s charter to serve three-year terms and that changing the meeting date improperly shortened their terms. When a separate challenge to the company’s poison pill was rejected by the courts, Air Products gave up its attempt to acquire Airgas. See Jef Feeley, “Airgas Trial on Air Products Bid to Focus on Meeting,” Bloomberg (October 1, 2010). Accessed June 30, 2014. See http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2010-10-01/airgas-trial-over-air-products-bid-to-focus-on-challenge-of-meeting-date. Davis Polk, “Delaware Court Permits Stockholders to Shorten Term of Airgas Staggered Board,” Client Newsflash (October 11, 2010). Accessed November 14, 2010. See http://www.davispolk.com/Delaware-Court-Permits-Stockholders-to-Shorten-Term-of-Airgas-Staggered-Board-10-11-2010/. Jef Feeley and Sophia Pearson, “Airgas Wins Ruling Invalidating Annual-Meeting Bylaw,” Bloomberg Businessweek (November 23, 2010). Accessed February 2, 2011. See http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2010-11-23/airgas-wins-ruling-on-annual-meeting-date-in-bid-to-fend-off-air-products.

60. SharkRepellent, “S&P 1500 staggered (Classified) Board Trend Analysis 1999–Present,” SharkRepellent, FactSet Research Systems, Inc. (2015). Accessed March 26, 2015. See www.sharkrepellent.net.

61. Lucian Arye Bebchuk, John C. Coates IV, and Guhan Subramanian, “The Powerful Antitakeover Force of Staggered Boards: Theory, Evidence, and Policy,” Stanford Law Review 54 (2002): 887–951.

62. John Pound, “The Effects of Antitakeover Amendments on Takeover Activity: Some Direct Evidence,” Journal of Law and Economics 30 (1987): 353–367.

63. Re-Jin Guo, Timothy A. Kruse, and Tom Nohel, “Undoing the Powerful Antitakeover Force of Staggered Boards,” Journal of Corporate Finance 14 (2008): 274–288.

64. Olubunmi Faleye, “Classified Boards, Firm Value, and Managerial Entrenchment,” Journal of Financial Economics 83 (2007): 501–529.

65. Martijn Cremers, Lubomir P. Litov, and Simone M. Sepe, “Staggered Boards and Firm Value, Revisited,” Social Science Research Network (July 14, 2014). Accessed May 5, 2015. See http://ssrn.com/abstract=2364165.

66. Weili Ge, Lloyd Tanlu, and Jenny Li Zhang, “Board Destaggering: Corporate Governance Out of Focus?” AAA 2014 Management Accounting Section (MAS) Meeting Paper, Social Science Research Network (January 29, 2014). Accessed May 5, 2015. See http://ssrn.com/abstract=2312565.

67. David F. Larcker, Gaizka Ormazabal, and Daniel J. Taylor, “The Market Reaction to Corporate Governance Regulation,” Journal of Financial Economics 101 (2011): 431–448.

68. ISS, “2013 Proxy Season Review: United States” (August 22, 2013). Accessed April 7, 2015. See http://www.issgovernance.com/library/united-states-2013-proxy-season-review/.

69. SharkRepellent (2015).

70. Michal Barzuza, “The State of State Antitakeover Law,” Virginia Law Review 95 (2009): 1973–2052.

71. Carl C. Icahn, “Capitalism Should Return to Its Roots,” Wall Street Journal Online (February 7, 2009). Accessed November 14, 2010. See http://online.wsj.com/article/SB123396742337359087.html.

72. Samuel H. Szewczyk and George P. Tsetsekos, “State Intervention in the Market for Corporate Control: The Case of Pennsylvania Senate Bill 1310,” Journal of Financial Economics 31 (1992): 3–23.

73. Guhan Subramanian, “Bargaining in the Shadow of Takeover Defenses,” Yale Law Journal 113 (2003): 621–686.

74. The Bancroft family held 83 percent of Class B shares. See Matthew Karnitschnig, “News Corp., Dow Jones Talks Move Forward,” Wall Street Journal (June 27, 2007, Eastern edition): A.3.

75. Morgan Stanley Investment Management, “Proxy Voting: Policy Statement (October 3, 2013).” Accessed April 3, 2015. See https://materials.proxyvote.com/approved/99999Z/20140812/other_217038.pdf.

76. ISS policy gateway, “United States Concise Proxy Voting Guidelines 2015 Benchmark Policy Recommendations” (January 7, 2015). Accessed March 9, 2015. See http://www.issgovernance.com/policy-gateway/policy-outreach/.

77. Calculation by the authors.

78. Oil-Dri Corporation of America, Form 10-K, filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission November 10, 2014.

79. Alibaba Group Holding Limited, Form F-1/A, filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission September 15, 2014.

80. Ronald W. Masulis, Cong Wang, and Fei Xie, “Agency Problems at Dual-Class Companies,” Journal of Finance 64 (2009): 1697–1727.

81. Paul A. Gompers, Joy Ishii, and Andrew Metrick, “Extreme Governance: An Analysis of Dual-Class Firms in the United States,” Review of Financial Studies 23 (2010): 1051–1088.

82. Robert Daines and Michael Klausner, “Do IPO Charters Maximize Firm Value? Antitakeover Protection in IPOs,” Journal of Law Economics and Organization 17 (2001): 83–120.

83. Michael Klausner, “Fact and Fiction in Corporate Law and Governance,” Stanford Law Review 65; Stanford Law and Economics Olin Working Paper No. 449. Social Science Research Network (July 23, 2013). Accessed May 5, 2015. See http://ssrn.com/abstract=2297640.

84. Julian Atanassov, “Do Hostile Takeovers Stifle Innovation? Evidence from Antitakeover Legislation and Corporate Patenting,” Journal of Finance 68 (2013): 1097–1131.

85. Sanjeev Bhojraj, Partha Sengupta, and Suning Zhang, “Takeover Defenses: Entrenchment and Efficiency,” Social Science Research Network (July 31, 2014). Accessed May 5, 2015. See http://ssrn.com/abstract=2474612.

86. Michael Bradley, Anand Desai, and E. Han Kim, “The Rationale behind Interfirm Tender Offers: Information or Synergy?” Journal of Financial Economics 11 (1983): 183–206.

87. Assem Safieddine and Sheridan Titman, “Leverage and Corporate Performance: Evidence from Unsuccessful Takeovers,” Journal of Finance 54 (1999): 547–580.

88. Ibid. This is consistent with target management committing itself to value-enhancing investments (similar to the disciplining role of debt suggested by Jensen [1986]). See Michael Jensen, “Agency Costs of Free Cash Flow, Corporate Finance, and Takeover,” American Economic Review 76 (1986): 323–339.

89. Kevin J. Delaney, Robert A. Guth, and Matthew Karnitschnig, “Microsoft Makes Grab for Yahoo!” Wall Street Journal (February 2, 2008, Eastern edition): A.1.

90. Steven M. Davidoff, “Dealbook Extra,” New York Times (June 6, 2008): 6.

91. Gregory Zuckerman and Jessica E. Vascellaro, “Corporate News: Icahn Aims to Oust Yahoo! CEO Yang if Bid for Board Control Succeeds,” Wall Street Journal (June 4, 2008, Eastern edition): B.3.

92. Jessica E. Vascellaro, “Yahoo! Vote-Counting Error Overstated Support for Yang,” Wall Street Journal (August 6, 2008, Eastern edition): B.6.