Chapter 7

Drawing on Graphical (and Other) Tools for Thinking

In This Chapter

![]() Mapping ideas with charts

Mapping ideas with charts

![]() Seeing graphical tools in action

Seeing graphical tools in action

![]() Discovering powerful tools for thinking

Discovering powerful tools for thinking

Reason makes things which are hard to define, difficult to comprehend.

—Pete Smee (UK professor)

It's lucky that there are more ways to try to understand things than by using reason alone. The human mind is actually very good at grasping complex relationships expressed in pictures and diagrams, for example. But how do you get an issue usually addressed in words and sentences to become one expressed graphically? This chapter is about how to do exactly that — and draw upon maybe unsuspected powers lurking within you!

Mind maps and other kinds of concept charts extract ideas from your head and turn them into something visible and structured. Sounds good, right? Well, they are, but here's the catch: although you can dash off the simplest charts fairly effortlessly, the more useful ones require a lot of thinking. Not only that, they require a lot of different kinds of thinking. Hence the huge difference between a good chart, a useful chart and a bad one that sheds no light at all.

In this chapter, you not only find out how to use graphical elements in a Critical Thinking context (which everyone seems to be doing nowadays), but also how to do so meaningfully, which is rather rarer. Think of this chapter as the ‘art’ one of the book . . . your chance to use different colour pens, browse clip art and maybe try out some computer design packages.

And in this chapter I'll also look at some other tools that can do this, including several different ways of brainstorming, the art of summarising and a variety of approaches to the technique known as triangulation. Sounds complicated? They're not, and I'll explain why.

Discovering Graphical Tools: Mind Mapping and Making Concept Charts

In this section I introduce some graphical tools that Critical Thinkers can use to gain insights into complex conceptual relationships and clarify issues. I call them all ‘concept charts’ but you can find plenty of other names being used, such as mind maps, flow diagrams — or even word trees. Don't get hung up on the terminology in this new and evolving area — the key thing is to see which ideas and techniques work for you. Indeed, you can (and should) just ‘pick'n’mix’ techniques if it seems useful.

Minding out for mind maps

But how do schematics like these ones work? Most of the time, whether speaking or writing, people present information in a linear sequence. They have to because people can't read or listen to two things at once — the competing information becomes a jumble. But in diagrams, the rules change. Suddenly information can be presented in ways that are much more in tune with the way the brain functions — by making multiple connections and comparisons simultaneously.

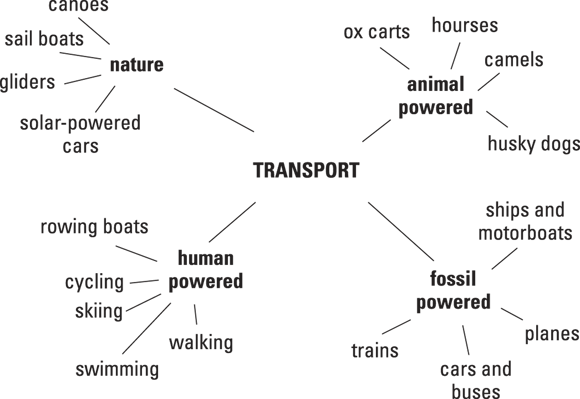

In a mind map, for example, information is structured in a radiant rather than linear manner, as Figure 7-1 shows. The core idea ‘transport’ generates four sub-divisions, which in turn prompt a whole range of specific examples.

Figure 7-1: A mind map on the core theme of ‘transport’. This is the kind of thing that a brainstorming session may produce.

Counting on concept charts

Following links and going with the flow

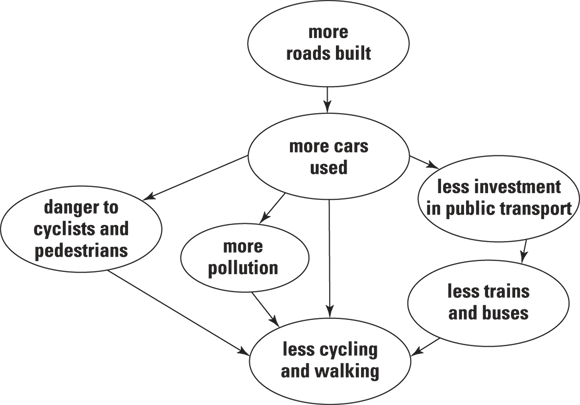

To see what I mean, look at my ‘Roads are Evil’ concept chart (in Figure 7-2), of the kind green activists may create at protest camps. Here the arrows tell a causal story: building the road led to the pollution and to the car accidents, which led to cyclists deciding to drive to work instead.

Figure 7-2: A flow chart that seeks to demonstrate (argue) a particular point: how and why building roads is bad.

On the other hand (to the extent that fewer buses would be wheezing round the streets and so on) less public transport could mean ‘less pollution’ and more walking! But arrows for this possibility aren't included. Diagrams soon get hard to follow if too many factors are included.

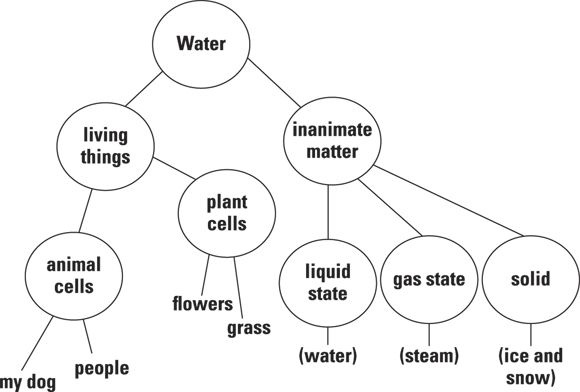

Take a look at the concept chart for water in Figure 7-3.

Figure 7-3: Water concept chart. A simplified version of one of Joe Novak's original concept charts (see the earlier sidebar ‘How it all got started’).

Since water is in all living things Figure 7-3 shows a nice solid line connecting the two. However, no plant cells grow in animals, and so there is no line between these two nodes (animal cells and plant cells). Simple but effective!

Putting Graphical Tools To Use

At the start of this chapter I promise to show you how to put graphical tools to meaningful use in a Critical Thinking context. Well, this is that practical, get-your-hands-dirty, section.

Choosing the right chart arrangement

- Spider: This chart is the easiest one to draw. It starts with the core concept at the centre with other ideas and connections radiating out (see Figure 7-1). Mind maps are essentially spider charts.

- Hierarchical diagrams: These often also branch out, but with a lot of categories at the bottom and just the one at the top (see Figure 7-3 on water).

- Various kinds of flow charts:, The key characteristic of these is that information ‘flows’ around the chart, with the focus often more on this flow than on the concepts in the nodes (check out the later section ‘Drawing flow charts’). Some flow charts specify where things start — inputs into the system — and where they can end — the outputs. Others may have no start or end points but describe the flow in terms of self-contained cycles (see Figure 7-2 on roads for an example).

Some people think that labelling the links — the lines — between the concepts is very important. But I'm not so sure, and it's certainly not universally agreed. Some maps use labels such as ‘includes’ or ‘with’. For example, in a map looking at geology, you may be told ‘metal’ includes ‘gold’ and includes ‘silver’, which seems to distract from the way the map is supposed to reflect the brain's architecture, and to have lost the good, original principle that instead of thinking only in words, people should try to visualise multiple relationships and connections. Add to which, labelling the lines requires people to go back to thinking ‘linearly’.

If, however, your chart is pretty formal, perhaps representing a process, with only one correct way possible to read it, the labels are useful; indeed they're an essential part of the chart's information.

Developing simple concept charts

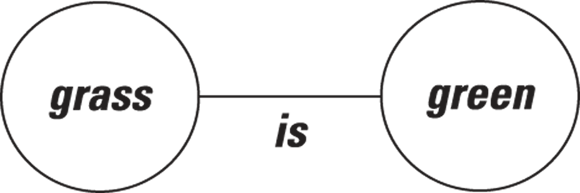

Basically, all concept charts represent statements, just like a written description does. In particular two nodes plus a connecting line represent a proposition, a statement that's supposed to be true. For example, the concept chart in Figure 7-4 is one way to represent the sentence ‘grass is green’.

Figure 7-4: A one-line concept chart.

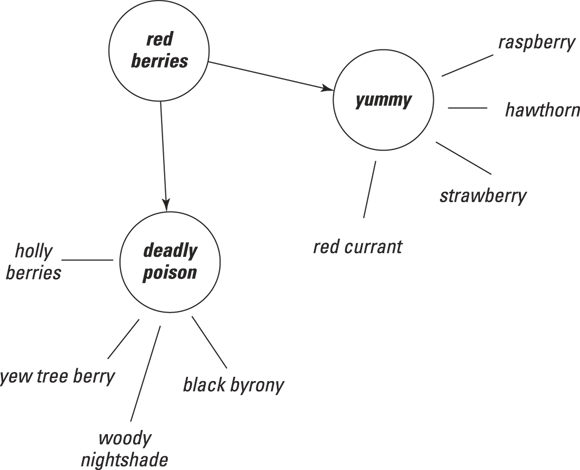

But a more complex and more useful example is to try to represent a sentence such as: ‘Red berries are yummy’. This process of adding new factors is well represented here (see Figure 7-5).

Figure 7-5: A simple chart that begins to do some conceptual work.

Now red berries — like strawberries — are yummy. Raspberries are yummy. Hawthorn berries can be used in jams and wines. But other kinds of red berries, such as yew and holly, aren't yummy.

These maps help both teachers and students to focus on the key ideas (concepts) needed in any given area of enquiry. Like how not to get poisoned when out on nature rambles!

Using maps and charts in the real world

Concept maps have their roots in the sciences, and are widely used today in fields such as software design or engineering, but they're also used in many business and (of course) educational contexts. Some charts are really too personal and idiosyncratic to say very much to anyone except the person who designed them — but others are precise and unambiguous blueprints. Such a wide spectrum of charts and maps exist that finding any features that they all share is difficult.

Because concept charts are constructed to reflect organisation of the declarative memory system, a technical term used to describe things such as facts and knowledge that can be actively recalled and, well, ‘declared’ (such as ‘Paris is the capital of France!’). they're often claimed to facilitate analysis and evaluation of information people already have. The other kind of memory is called non-declarative or procedural memory, and refers to unconscious memories. Things such as skills like, for example, riding a bicycle, or how to construct sentences correctly.

Appreciating the different styles of concept charts and mind maps

When you're producing mind maps and concept charts, you need to be aware of how different graphical techniques suit the different issues, questions or problems.

Concept maps and topic maps (to add another term for something very similar) both allow people to connect concepts or topics via a graphical representation, and both can be contrasted with the particular idea of mind mapping, which is often restricted to radial hierarchies (those spider diagrams) and tree structures. Topic maps are intended to be easily navigated and quickly indicate information — like a well-designed index at the back of a book. But out of all the various schema and techniques for visualising ideas, processes, organisations, concept mapping is unique in its philosophical basis. Which, according to its inventor, Joe Novak, ‘makes concepts, and propositions composed of concepts, the central elements in the structure of knowledge and construction of meaning’.

Another contrast between the more formal kinds of concept mapping and mind mapping is the speed and spontaneity possible when creating the latter. A mind map typically reflects what people think about a single topic, which can focus group brainstorming (something I discuss further in the later section ‘Conjuring up ideas with brainstorming’). The more formal kind of concept chart is rather harder to create, but when done, it can provide more insights. It's a true map, in the sense of something that tells you how things relate and how one thing connects to another. It provides a system view, of a real or an abstract concept.

Graphically, concept charts can become complicated and cease to follow any obvious spatial logic as multiple hubs and clusters are created. For example, one part may be unimportant but take up a lot of space, and another important element may be represented by just a single word or image. In this sense, Mind maps, which fix on a single conceptual centre and then radiate out, have a nice kind of visual logic built in.

Adding movement to your diagrams by drawing flow charts

A common type of technical diagram is a flow chart — which in the broad sense is a concept map. However, the term usually means a pretty precise kind of schematic representation of a sequence of operations, as in a manufacturing process or computer program.

You can see the similarities between these kinds of technical diagrams and rather more free-spirited efforts in the social sciences when you consider the ways that technical flow charts are used. These usually include:

- Defining and analysing a process.

- Providing a step-by-step picture of a process for later analysis, discussion or communication.

- Defining or standardising a process.

- Looking for ways to improve processes.

Most flow charts are made up of three main types of symbol:

- Elongated circles: Signify the start or end of a process.

- Rectangles: Show instructions or actions.

- Diamonds: Show decisions that must be made.

Within each symbol, you write down what the symbol represents: the start or finish of the process, the action to be taken or the decision to be made. Finally, symbols are connected one to the other by arrows, showing the flow of the process:

- Start the flow chart by drawing a circle shape and labelling it ‘Start’.

- Move to the first action or question, and draw a rectangle or diamond depending on whether a decision is required at this stage or not.

- Write the action or question inside it, and draw an arrow from the start symbol to this shape.

Work through your whole process, showing actions and decisions appropriately in the order they occur, and linking these together using arrows to show the flow of the process.

Where a decision needs to be made, draw arrows allowing for every possible outcome from the decision diamond. These arrows are usually labelled with the outcome. At the end of the process is a circle labeled ‘Finish’.

- Test-run your flow chart, working from step to step asking yourself if you have correctly represented the sequence of actions and decisions involved in the process. And then (if you're looking to improve the process) think about whether work is duplicated, or whether other stages should be added.

The process of physically splitting up your diagram can also imply a way to mentally split up a complex issue or process, enabling you (or the people you are sharing the idea with) to concentrate on particular parts of it better.

Considering Other Thinking Tools

The graphical tools I discuss in the preceding section aren't the only ones available to you. Here I cover dump lists, summarising, brainstorming, meta-thinking and triangulation. You can think of these tools as organizational strategies for the contents of your brain!

Dump lists is a way of organizing information in your head, summarizing and meta-thinking are about making sense of things you read or hear, and triangulation is about checking the quality of what you have come up with. Brainstorming is primarily a tool for generating ideas but can also be used to help sort and analyse information.

Emptying your head with a dump list

The truth is that coming up with material is much easier than analysing and selecting the key ideas within it.

Say that you're wondering about a practical problem that presumably has a practical solution, such as why all the plants in your house always die, but you've not yet been able to find the answer. Try a bit of Critical Thinking.

- Lots of my house plants dry out.

- Nothing seems to grow.

- The leaves of my plants go brown and then drop off.

- Even the cactus has a kind of white fungus.

- Maybe I should water my plants more.

- Maybe my plants need plant food.

- Maybe the rooms are too draughty.

- Maybe the plants aren't getting enough sun.

The next step is to do some sifting, sorting and maybe simplifying of the list. Could some of the points usefully be grouped together as concerning the same sort of thing? Is there any one step that would solve the problem. Perhaps you can get rid of things that are easy to solve: for example, the problem ‘the soil has dried out’ implies the solution ‘I should water the plants’. On the other hand the problem ‘Even the cactus has a kind of white fungus’ seems to indicate that maybe too little water is not the problem. So beware crossing out things too soon on your list, as oversimplification of an issue can lead to errors later.

Sifting for gold: Summarising

Summarising is such a useful skill! It involves separating the wheat from the chaff, the golden nuggets from the heaps of spoil, the key words and phrases from the blah, blah blah. Put more simply, summarising is a key life tool that enables you to organise and make sense of the world around you. Here's some simple techniques that can help you do it effectively. Plus, it's a great chance to use those highlighter pens that come in so many more shades than fluorescent yellow.

All you do is use your favourite highlighter to mark up the key points in a piece of text. If you find you've marked up several paragraphs, maybe you aren't being quite critical enough — not summarising but, well, highlighting. So be strict with yourself: only mark up the key idea in any paragraph, and only highlight elements from the most important paragraphs.

But when you do find a phrase in the original text that's particularly striking, and really can't be summed up without losing something, do use the author's exact words. Highlight them! If you make a note, make sure that you put quotation marks around the words and indicate the source — otherwise that fine phrase may turn up, rather disgracefully, unattributed in your work.

Conjuring up ideas with brainstorming

Brainstorming is the name given to the fairly obvious technique of quickly jotting lots of ideas down in response to a question — or even simply a concept. You can brainstorm on your own, but the real advantages of the technique come when you're in a group, because that's where other people's ideas can spark new ones among other members of the group.

The claim of the method's supporters is that brainstorming allows a group to think collectively and build on each other's ideas. Conducting a group brainstorm can also create a buzz, something that can be absent when you work on your own. But brainstorming can be a bit of a ‘lowest common denominator’ exercise too — by which I mean that the idea that everyone likes is not the best one but only the one that everyone shares. Worse! The group may not recognize a good idea just because it is a bit different or novel. So how you brainstorm is important.

- Scribe: Co-ordinators (the scribes) not so much write (which can be a cumbersome and inefficient process) but rather ‘capture’ on the board all the ideas that team members call out. They try to sum up the idea in an appropriate way, regardless of their own feelings about the merits or demerits of the idea.

- All-in: During these sessions, team members can write on the board their ideas just as they come, or perhaps instead verbally share them with the group. The ever-useful yellow sticky notes can be brought out, so that everyone can write their ideas down and then stick them on the board.

The attitude and abilities of the co-ordinators are vital to a successful brainstorm — and although not everyone automatically has the ‘right stuff’, some principles certainly can be adopted. The person leading the brainstorm needs to be enthusiastic and encouraging. Adding ‘fun’ constraints can help spark new ideas — for example, if a group is wondering about, say, how to revitalise inner cities (perhaps a bit of a downer for an early morning session), the co-ordinators can constrain the issue by asking instead: ‘If you had to improve life for people in inner-city Liverpool with just one big project — what would it be?’

Ascending the heights: Meta-thinking

Concept charts require the higher skills in Bloom's famous taxonomy, from mere recall at level one to complex evaluation at level six (check out Chapter 8 for details). In fact, Joe Novak (see the earlier sidebar ‘How it all got started’) says it requires students to use all the levels at once!

But Meta means ‘above’ or ‘higher’, and so meta-thinking indicates taking an overview (view from above) and represents a higher (more critical) level of thinking skill. To be critical often requires a move from ground-level to meta-level thinking.

In his terms, Blue Hat thinking focuses on how to manage the thinking process, checking its focus, setting out the next steps, creating action plans. For instance, if a football team is discussing how to win the next game, the coach likely automatically adopts the Blue Hat style, reminding the players that:

- The focus is how to win the next game against the Brickworks Eleven.

- The agreed next steps the team has identified include practising penalties (because the Brickworks team commit a lot of fouls and maybe will give a penalty away).

- The longer-term aim is how to build on the expected victory over the Brickworks Eleven and get the team promotion to the Grimsby West League!

Trying out triangulation

Or ‘How to triangulate the data to stop the roof falling in’ (that's a metaphor, by the way, which seemed appropriate to me because most roofs contain wooden triangles, which literally stop them falling in).

Triangles are very strong structures and perhaps this is the best way to think of the activity that academics have in mind when they use the term triangulation to describe a methodological tool used when constructing essays and arguments across all areas of knowledge (instead of the mathematical sense, used for many purposes including surveying, navigation, metrology, astrometry and so on.

The use of triangles to estimate distances goes back a long time, certainly to the 6th century BC when the Greek philosopher Thales is said to have used ‘triangulation’ to calculate the height of the pyramids. In Critical Thinking, however, where triangulation is about running a check on your work and strengthening conclusions, the term was only introduced in academia in the 1960s.

- Qualitative researchers: People whose research involves judgements more than mere measurements often use it as a kind of double check on their background assumptions. When triangulation throws up inconsistencies, these researchers (who are concerned with human perspectives) often see the differences as an opportunity to uncover deeper meaning in their data.

- Quantitative researchers: These more ‘scientific’ number-crunching researchers may be more interested in spotting flaws in their methodology and usually just want all their studies to arrive at the same figures. They're inclined to consider differences as very bad news, as ‘weakening the evidence’.

Real-life triangles

Gayle Burr found that two very different impressions of family needs came about depending on whether the relatives were interviewed in person or merely filled out questionnaires. The relatives who were interviewed found talking to the researcher about their experiences therapeutic, and thus were inclined to be positive, but those who only filled out questionnaires used them to communicate their frustrations. Thus, using both research techniques (interviews and questionnaires) added an extra level of insight to the results, making them not only more ‘valid’ in an abstract sense but much more useful in a practical sense too.

When the detective amasses fingerprints, hair samples, alibis, eyewitness accounts and the like, a case is being made that presumably fits one suspect far better than others. Diagnosis of engine failure or chest pain follows a similar pattern. All the signs presumably point to the same conclusion. Note the importance of having different kinds of measurement, which provide repeated verification.

—Matthew Miles and Michael Huberman (Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook (2nd Edition), Sage Publications 1994)

Denzin's three-sided methods

Norman Denzin wrote two books about alcoholics and hospitals that some people in the sociological research business think are hugely underrated classics on a par with the writings of the 19th-century sociologist, Emile Durkheim. Whether Denzin's really is a ‘great’ or not shouldn't matter to Critical Thinkers, but his books certainly contain important messages about a profound social malaise in America, which he attributes to a ‘white male culture’.

Denzin argues that the story of alcohol is intricately connected to the story of American society, because alcohol is a key link between individuals and the social structure. Alcoholics, he says, use alcohol to try to assert their place in the word, and to ‘control’ the world. Of course, in extreme cases, they're the ones who lose control — to alcohol.

Now because Denzin is interested in the inner world of the alcoholic and in the social structures and the ‘real world’ surrounding them, he asks the reader to think of two researchers studying someone who's suffering mental illness and is in hospital. Each of the researchers chooses different methods: one opts for a survey while the other uses participant observation. These methods lead to differences in the questions they ask and the observations they make.

In addition, the findings are coloured by the researchers’ different personalities, biographies and biases, which influence the nature of their interactions with the social world. Each uncovers different aspects of what takes place in the hospital but neither can reveal it all. Therefore, Denzin concludes, to get as full and as accurate a picture as possible, researchers must use more than one strategy.

Answers to Chapter 7’s Exercises

Check out the following answers to this chapter's exercises.

The Plant Problem

Here's my approach to addressing this problem:

- Problems: Plants dry out. Leaves go brown and then drop off.

- Solution: More water.

- The cactus: A special case! Separate it out.

Summarising the paragraph

The key idea here is: ‘use your favourite highlighter to mark up the key points in a piece of text’.

But the pictures or, more accurately, the diagrams you end up with aren't just pretty illustrations. They're ways of coming to deeper insights and more sophisticated understandings of issues and processes.

But the pictures or, more accurately, the diagrams you end up with aren't just pretty illustrations. They're ways of coming to deeper insights and more sophisticated understandings of issues and processes. The process of constructing mind maps and other kinds of concept chart, hinges on using nodes and links. The nodes are represented as circles or squares or other shapes and stand for ideas and information. The lines connecting the nodes are the links and these are the defining relationships. By connecting information like this, you are actually making knowledge explicit — in other words, knowledge is dragged from the subconscious and put on paper in plain black and white (or gorgeous colours). When you create concept charts, you not only become aware of what you already know, but are also able, as a result, to modify and build upon it.

The process of constructing mind maps and other kinds of concept chart, hinges on using nodes and links. The nodes are represented as circles or squares or other shapes and stand for ideas and information. The lines connecting the nodes are the links and these are the defining relationships. By connecting information like this, you are actually making knowledge explicit — in other words, knowledge is dragged from the subconscious and put on paper in plain black and white (or gorgeous colours). When you create concept charts, you not only become aware of what you already know, but are also able, as a result, to modify and build upon it. Professors take the term nodes from maths, where a node is a point in a network at which lines intersect, branch or terminate. Concept charts are networks made up of those nodes and links.

Professors take the term nodes from maths, where a node is a point in a network at which lines intersect, branch or terminate. Concept charts are networks made up of those nodes and links. A mind map is a particular kind of concept chart that usually (but as I say, people use the term pretty fluidly) has one term or concept as its focus. The aim is to literally map out your thoughts, using associations, connections and triggers to stimulate further ideas.

A mind map is a particular kind of concept chart that usually (but as I say, people use the term pretty fluidly) has one term or concept as its focus. The aim is to literally map out your thoughts, using associations, connections and triggers to stimulate further ideas. Notice how the arrows in the figure serve to make an ‘argument’, but also that a chart maker could choose to direct them very differently. In fact, a more accurate flow chart would be one showing all the feedback effects of certain decisions in transport policy — for example, how more cars being used also means more roads are built. This aspect could be shown with a bi-directional arrow, or by not using an arrow at all, just a line.

Notice how the arrows in the figure serve to make an ‘argument’, but also that a chart maker could choose to direct them very differently. In fact, a more accurate flow chart would be one showing all the feedback effects of certain decisions in transport policy — for example, how more cars being used also means more roads are built. This aspect could be shown with a bi-directional arrow, or by not using an arrow at all, just a line. Why not practice with a simple chart on, say, ‘Reading a book’?

Why not practice with a simple chart on, say, ‘Reading a book’?