Chapter 12

Unlocking the Logic of Real Arguments

In This Chapter

![]() Picking out the key elements in everyday arguments

Picking out the key elements in everyday arguments

![]() Examining reasoning in detail

Examining reasoning in detail

![]() Thinking about your listeners or readers

Thinking about your listeners or readers

Thinking is the hardest work there is, which is the probable reason so few engage in it.

—Henry Ford

Arguments lie at the heart of Critical Thinking (‘oh no they don't!’ you cry. ‘Oh yes they do!’ I reply. That's not an argument, by the way, just irritating contradiction!). Such arguments come in all sorts: hidden, irrational, polemical or whatever. But a difference exists between the ‘real-life’ informal arguments of everyday life — ones about real issues addressed to real people — as opposed to the neatly organised formal ones you often find presented in philosophy textbooks.

You encounter these ‘real’ arguments every day. On TV, politicians argue about policies, talent-show judges argue about ‘talent’ and two-dimensional characters argue in soap operas. In the pub, people argue about the relevant merits of their football teams (or even of different sports) and whose partner at home is ‘just the worst’. Often these everyday exchanges aren't arguments in the philosophical or logical sense; they're more like disagreements and increasingly forceful statements of entrenched opinion.

In this chapter I examine some short but fairly typical real arguments both to see how they're constructed and so that you can practise your key Critical Thinking skills. In the process I take a look at aspects that people take for granted in everyday life, such as notions of cause and effect, and the different kinds of reasons — necessary and unnecessary, sufficient and insufficient — that people often confuse when trying to back up their conclusions.

Introducing Real-Life Arguments

In philosophy textbooks, the books on which most Critical Thinking guides are based, the arguments are usually tidy and precise (especially so-called deductive ones — the kind in which Sherlock Holmes specialises). The facts of the matter are clearly stated and the conclusion is neatly marked out with a line or the word ‘therefore’. The focus of attention is definitely all on the logic — or lack of it.

We must take urgent steps to reduce carbon emissions, or the world will overheat!

or

Children should not eat biscuits. They're bad for their teeth.

In addition, to confuse matters further, in everyday language people use the word argument to mean a bad-tempered quarrel or dispute, which is the last place to look for logic or structure.

Even so, you can still restate much of this type of emotional outburst philosophically. After all, most everyday disagreements start with a fact or claim, the argument then working backwards by offering reasons why the statement is true or false, depending on the point of view of the speaker.

In this section, I describe informal logic, the particular role of premises in arguments, and how images can also be used to back up claims. I also investigate the logical structure of arguments, revealing one common error that people — even professors — often make.

Coming as you are: Informal logic

Informal logic sounds intimidating, but needn't be at all:

Informal logic: All about assessing and analysing real-life arguments and debates using everyday language. The work is really in the conversion of issues expressed in informal, everyday language into something more structured.

Informal logic: All about assessing and analysing real-life arguments and debates using everyday language. The work is really in the conversion of issues expressed in informal, everyday language into something more structured.- Formal logic: In contrast, these arguments use symbols and letters to represent the argument. Once an argument has been reduced to symbolic notation, its structure should be easier to see and logicians can then manipulate it in the same sort of (very precise) way that mathematicians manipulate equations.

I know explanations can get more confusing when additional explanations are added into the explanation! Informal logic is really the topic, formal just crept in. . . .

To illustrate, I need an everyday argument. Sure enough here comes one now!

You're a rotten husband!

You don't do the washing-up and you don't even do the gardening.

In philosophy, arguments are typically presented as a series of statements that are themselves true or false (these are generally called premises) coupled with a conclusion. Thus the Critical Thinker prefers to restate the above conversation with the following structure:

- First premise: Rotten husbands are men who don't do the washing-up and don't even do the gardening.

- Second premise: You don't do the washing-up and you don't do the gardening.

- Conclusion: You're a rotten husband!

As I explain in more detail in Chapter 13, if the argument is valid (constructed correctly) then as long as the premises are true, the conclusion must be true too.

This argument, by the way, isn't valid. (Hint: rotten husbands aren't the only people who don't do the washing-up and don't do the gardening.) But pointing out the error in the reasoning is hardly going to let anyone off doing their chores, which just underlines that getting the logical structure of an argument right isn't going to settle many real-life issues. But even so, it can help identify the real issues in a debate.

Persuading with premises

Informal arguments that use everyday language should still set out an argument in good, persuasive steps, putting the assumptions (the premises) first and making sure that the real point is a deduction that follows on (or at least appears to!) later.

Here's a pretty good example of how to do it from logician and political activist Bertrand Russell. He's putting forward a deceptively simple argument concerning educational policy:

The evils of the world are due to moral defects quite as much as to lack of intelligence. But the human race has not hitherto discovered any method of eradicating moral defects. . . Intelligence. . . on the contrary, is easily improved by methods known to every competent educator. Therefore, until some method of teaching virtue has been discovered, progress will have to be sought by improvement of intelligence rather than of morals.

—Bertrand Russell, Sceptical Essays (1935)

Here's my attempt (but try forming your own before peeking):

- First premise: People's bad behaviour should be improved either by improving their morals or through education.

- Second premise: There's no known way to improve people's morals.

- Conclusion: Therefore, people's bad behaviour should be improved through education.

Using pictures in everyday arguments

Far better an approximate answer to the right question, which is often vague, than an exact answer to the wrong question, which can always be made precise.

—John Tukey

Real arguments don't depend just on words, of course. The most successful political broadcasts, for example, mix a voiceover with compelling images to persuade their audiences (a picture really is worth a thousand words); homeowners are supposed to be able to persuade potential buyers by having a pot of coffee brewing. In this section I discuss how these illogical elements persuade, showing that the process is often very subtle.

- Some people are sceptical that images can do any work other than rhetorical.

- Others think that images can carry arguments independently.

- Still others believe that images can carry at least some parts of some arguments.

Many advertisements rely on pictures to support an argument. this fact. Imagine an advertisement for, say, Dummies Jeans, that says simply: ‘Buy Dummies Jeans’. It wouldn't sell very many just for that. But coupled with a picture of some attractive, successful, fun-looking young people — it might well do. The reason is the implied connection between being attractive, successful, fun-looking and young — and the jeans: if you buy Dummies Jeans then you'll become like these people!

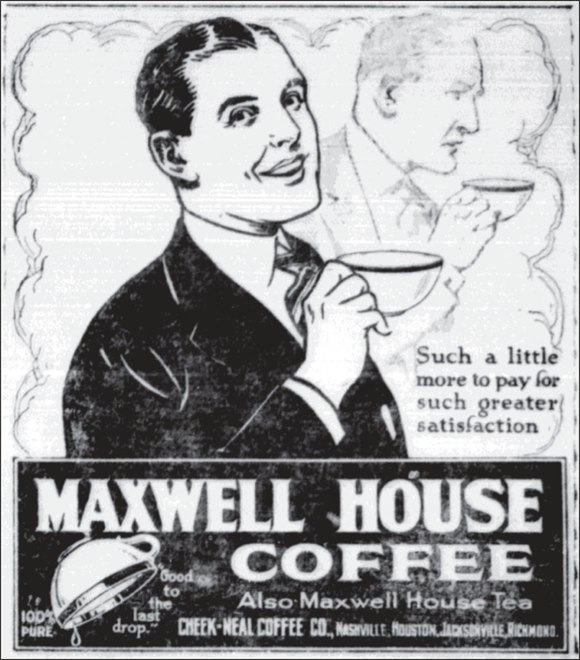

Or take the classic advertisement from the 1920s in Figure 12-1, which simply makes an assertion about the brand (of coffee) that's worth paying ‘a little more’ for. The evidence for the statement is in the pictures. The man is obviously drinking it with enjoyment, while the shadowy drinker just behind is obviously not getting the same ‘satisfaction’ from his cup o’ Joe.

Figure 12-1: Such a little to pay! But where's the evidence?

Okay, this is how I ‘deconstructed’ the ad:

- First premise: Paying a little more for something is worth it if it brings you real satisfaction.

- Second premise: This kind of coffee brings you real satisfaction.

- Conclusion: Therefore, paying a little more for this kind of coffee is worthwhile.

That's the surface message, anyway. The subliminal (hidden) message is that the particular brand of coffee is superior to other brands. This message appears in the argument as one of the assumptions in the premises).

Checking a real argument's structure

Even though real arguments are phrased in ordinary language, they still have a structure that you can try to reveal by stripping away the unnecessary details and expressing the whole thing in its argumentative essence.

Sometimes the use of everyday language itself causes problems with the argument's logic. One logical error is so common it has its own special name: the fallacy of affirming the consequent. You don't need to know the name, but you do need to be able to spot this mistake in reasoning, because it's probably one of the most common errors people — even famous philosophers — make.

Analysing an example of a real argument

Here's a slightly dodgy real argument that illustrates the point from a recent book (The God Argument) by a university philosophy professor.

As presented in his book, religion is a nasty business, consisting of hanging homosexuals, beheading or stoning to death adulterous women, and subordinating ‘women and children’ in Bible Belt America. Because (says the author) religious belief, historically and today, leads to these awful things, people should always try to discourage religious belief.

This is a real argument in two senses: people really make it — as the professor does in his book (although not in so many words) — and it's expressed in everyday language.

Here's one way of looking at its structure, including the evidence offered:

- First premise: Religious belief leads people to do terrible things to other people, such as hanging them for being homosexual or stoning them to death.

- Second premise: Leading people to do terrible things to others, such as hanging them for being homosexual or stoning them to death, is bad.

- Conclusion: Therefore, religious belief is bad.

On that basis the claims here look okay. To investigate whether the sweeping conclusion demands acceptance too — as the professor hopes — you can structure the argument a bit more formally, as follows:

- First premise: Religion leads to terrible things.

- Second premise: If something is terrible, it should be banned.

- Conclusion: Therefore, religion should be banned.

The structure looks to be something like this:

- If A then B.

- If B then C.

- Therefore, if A then C.

Expressed in this way, the argument certainly appears to be valid (in the sense I describe in the earlier section ‘Coming as you are: Informal logic’). But in fact a bit of cheating is going on: it lies in the words of the original argument. Check out the first premise again, the one that says:

Religious belief leads people to do terrible things to other people, like hanging them for being homosexual, or stoning them to death.

The professor doesn't flatly say that religious belief always and invariably leads to each of its adherents doing terrible things but only that it sometimes leads to some people doing them. Clearly he can't state the former, because Mother Teresa, for example, didn't stone adulterers to death in India but helped sick children. So a more accurate way to represent the argument might be as follows:

- If A then sometimes B.

- If B then C.

- Therefore, if A then C.

However, this argument is certainly not valid. As long as some ‘A’ aren't ‘B’, any additional information, no matter how juicy, about ‘B’ is always going to be entirely irrelevant to them. On the other hand, maybe the professor isn't intending to argue this. Perhaps the essence is instead better summarised as follows:

- First premise: If religion is an evil influence on people then people's minds will be addled and lots of bad things result.

- Second premise: People's minds have been addled and lots of bad things have resulted.

- Conclusion: Therefore, religion is an evil influence on people.

Even if it is this version though, the conclusion is still rather wonky. (See the nearby sidebar ‘Scientists arguing illogically’ for more on this.) The problem now with this reasoning is that another explanation for the bad things may exist: maybe inbred sexism or aggressive pursuit of economic self-interest. But such issues are getting, I suppose, into the area of sociology. Explaining the world's problems isn't your task here — you're just looking at the structure of arguments. And in this case, it does seem that the logic of this real argument is rather wonky.

Discussing the usefulness of the fallacy

The fallacy of affirming the consequent is just one of a list of logical fallacies that Aristotle drew up thousands of years ago but are still going strong (see Chapter 14 for details). Indeed, it's such a common argumentative tactic that pointing it out can seem a cool trick to make you look much cleverer than your opponent. But in ‘real life’, is it really an error at all?

People who commit a logic reversal and affirm the consequent are implying that the effect of a cause is also the cause of the cause. To see why this is wrong, recall, from the logic vaults, the crown jewel of the logic, the valid argument called the modus ponens (from the Latin, for ‘the way that affirms by affirming’ — but, for all it matters, it is just a funny name), which has a special form which you can see in the following example.

Suppose you're talking about Paris. A correct argument proceeds like this:

- If it's December then it will be cold in the pavement cafés.

- It is December.

- Therefore, it will be cold in the pavement cafés.

The conclusion is true because the premises are taken to be true:

- If A then B

- A

- Therefore B

But look what happens if instead the argument is mangled to become ‘B therefore A’:

- If it's December then it will be cold in the pavement cafés.

- It is cold in the pavement cafés.

- Therefore, it must be December.

But no! It can be a cold day in January or in almost any month.

Delving Deeper into Real Arguments

In real, everyday, informal arguments, if people don't agree on the underlying facts (the starting points), no amount of persuasion ever allows one side to persuade the other of the rightness of their position. In this section I take a look at the classic ‘if . . . then’ formula, revealing some aspects that people can mix up: cause and effect, unnecessary and insufficient conditions, and independent and joint reasons.

Considering the formula ‘if A then B’

In a sparky, recent book called If A then B: How the World Discovered Logic, two philosophy professors, Michael Shenefelt and Heidi White, argue that reasoning, knowledge and rationality are first and foremost matters of logic: of applying that deceptively simple formula ‘if A then B’ to the world. What's more they argue that the history of the world is also the history of simple logical forms. For example, the simple arguments I discuss in this chapter — where statements are presented and then claimed to lead to a certain conclusion — emerged out of the Ancient Greek way of taking decisions. For the background history, see the nearby sidebar ‘A history of arguing’.

The idea is that if everyone agrees to be logical and let rules decide arguments, people should eventually reach decisions that everyone can see the reasons for and by and large can accept.

Assuming a causal link

Causal links in nature are central to the way people make sense of the world — and just as in logic, they're often not thinking directly about the mechanisms, about why A leads to B. For example, consider these arguments or claims:

- Don't eat wild mushrooms — they're poisonous.

- If you study hard, you'll get a better grade in the exam.

They are very different kinds of statements. One seems more ‘causal’ than the other — yet in another way they're both similar because they're both statements of the kind ‘all A are B’:

- All wild mushrooms are poisonous.

- All people who study hard get good grades.

The philosopher David Hume is credited with a great insight into everyday arguments. He says that the deeply held belief of causal links — for example, that not watering plants causes them to wither or that throwing rocks at windows causes them to break — isn't logical but merely psychological. His rather abstract point about ‘cause and effect’ has many practical implications for Critical Thinking, because he's challenging the root of logic itself.

And what stronger instance can be produced of the surprising ignorance and weakness of the understanding than the present. For surely, if there be any relation among objects which it imports to us to know perfectly, it is that of cause and effect. On this are founded all our reasonings concerning matter of fact or existence . . . Our thoughts and enquiries are, therefore, every moment, employed about this relation: yet so imperfect are the ideas which we form concerning it, that it is impossible to give any just definition . . .

In other words, a key idea that human beings use to make sense of the world around us, that what we have observed one day, in one set of circumstances, can be learnt from and assumed to apply another day in similar circumstances, is based itself just on faith! Why should the same cause always have the same effect? His idea is so radical that it makes nearly all arguments fall to pieces straight away! Hume admits himself that he can see no answers to his problem, but suggests shrugging and carrying on anyway. In a sense that is what we have to do. But Critical Thinkers can benefit from the warning by always doubly sceptical and asking questions when someone asserts that a certain outcome will always follow, given a certain action.

Discussing unnecessary and insufficient conditions

Here's another way in which drilling down into logical reasoning and revealing an their formal structures can help in even informal arguments: specifically, the difference between necessary and unnecessary conditions.

Everyone's familiar with the concept of something being necessary. For example, in order to keep fish in an aquarium alive, it is necessary to make sure that it's full of water. If you let the water evaporate out, the fish perish.

If Phyllis the goldfish is to be happy and healthy [the antecedent] then the water in the aquarium must be kept topped up [the consequent].

So important are necessary conditions that in ordinary language people have many ways to express them. For example:

- Water is necessary for fish to live.

- Fish must have water to live.

- Without water, fish die.

- No fish can survive long outside water.

But keeping the water level topped up isn't a sufficient condition for keeping Phyllis the fish happy and for having a successful aquarium. For example, you need to make sure that the water is clean, that oxygenating weeds are present and that the water is the right temperature. So the water level is a necessary but insufficient condition. So far so useless! But this insight does lead you towards being able to make a new suggestion:

If Phyllis the goldfish is to be happy and healthy then I must place a plastic castle for her to swim around at the bottom of the aquarium.

Certainly this is a very nice thought and I'm not against it at all, but is it absolutely necessary to provide plastic castles for goldfish? Not at all. You could provide some interestingly shaped rocks instead or maybe more weeds.

So clearly this is an unnecessary condition, because Phyllis can be healthy even without the castle. But is the plastic castle also an insufficient condition? Yes it is, because if you fail to feed her, or let the water level drop, or lots of other things, the plastic castle isn't enough to keep Phyllis healthy and happy.

Okay? Here's a couple that you probably didn't think of: you mustn't have any cats that can gobble up Phyllis or any nasty anchor worm eggs introduced into the aquarium, say on the pond weed!

Don't kick yourself if you missed those two. Instead, award yourself one mark if you listed ten points and three marks if you wrote less. Because a Critical Thinker soon realises that it isn't too useful to spend too long on that list because it is potentially an infinite task.

Investigating independent and joint reasons

One quite subtle distinction in critical thinking is between independent and joint reasons.

Killing animals for meat is wrong. Therefore, everyone should become vegetarians.

The argument ‘works’ because the word ‘should’ contains a judgement about what's right and what's wrong — and the first part of the argument says that killing animals is wrong. The hidden structure is probably as follows:

- Killing animals is wrong.

- People shouldn't do things that are wrong.

Therefore, people shouldn't kill animals.

(next step)

- People who aren't vegetarians are involved in the killing of animals.

- Killing animals is wrong.

- Therefore, everyone should become vegetarian.

- Two thirds of the world's surface is covered in water.

- If people stop eating fish then pressure on the fragile ecosystems on land will be increased.

- Increased pressure on the fragile ecosystems on land is bad for the environment.

- Vegetarianism requires people not to eat fish.

- Therefore, vegetarianism is bad for the environment.

There! In this section, you've used logic to prove two opposite sides of the argument! (Vegetarianism is morally right, and vegetarianism is morally wrong.) That's a pretty handy Critical Thinking skill.

Being aware of hidden assumptions

Looking at arguments from the point of view of those making them helps you to spot hidden assumptions that they're making, assumptions that you may want to discuss openly and perhaps challenge.

Elements that influence your views (often without you really realising it) include the following:

- Race, nationality and culture.

- Language and your education.

- Family status (do you have children who depend on you? Are you reliant on others?).

- Economic or social class.

- Whether you're religious or non-religious.

- Views of your peer group (for example, teenagers are notoriously sensitive to and influenced by whatever their friends are doing!).

- Anticipate the kind of counter-arguments that may be put.

- Make a kind of ‘pre-emptive manoeuvre’, by rethinking and if necessary strengthening your own assumptions, especially ones you hadn't really been properly aware of.

But in real, everyday life, people don't argue like that. They rarely start by stating their factual assumptions but instead leave them to be guessed at, and they tend to leap instantly to the conclusion. Here's an example:

But in real, everyday life, people don't argue like that. They rarely start by stating their factual assumptions but instead leave them to be guessed at, and they tend to leap instantly to the conclusion. Here's an example: The distinction isn't much more than that between formal and informal clothes: you dress formally for an interview and informally to cut the grass.

The distinction isn't much more than that between formal and informal clothes: you dress formally for an interview and informally to cut the grass. Grab a pen and paper (or text it on your phone) and set out Russell's argument as three pithy, short sentences, split into two claimed statements of fact and a conclusion that's supposed to follow from them.

Grab a pen and paper (or text it on your phone) and set out Russell's argument as three pithy, short sentences, split into two claimed statements of fact and a conclusion that's supposed to follow from them. David Hume says that the idea that one thing causes another is a human construction, based on past observations and experience. This is his argument

David Hume says that the idea that one thing causes another is a human construction, based on past observations and experience. This is his argument