Chapter 8

Constructing Knowledge: Information Hierarchies

In This Chapter

![]() Seeing how people handle new information

Seeing how people handle new information

![]() Thinking deeper about the knowledge pyramid

Thinking deeper about the knowledge pyramid

![]() Resisting the temptation to give up learning

Resisting the temptation to give up learning

Information is not knowledge. The only source of knowledge is experience.

—Anon.

Some people attribute this piece of wisdom to Einstein, but no one seems to be able to trace it to anything specific. It's certainly the sort of thing he'd say, being a scientist, but then it's also the sort of thing that lots of philosophers have said (such as John Dewey, who guest stars in this chapter). I start with this quote, because it reflects a central theme of this chapter: that many stages of information processing lie behind every piece of knowledge.

To illustrate the process of building knowledge, this chapter uses the analogy of constructing a pyramid. I describe climbing the knowledge pyramid by checking out the building blocks of knowledge: data and information. I also discuss the elegant and definitely pyramid-shaped ideas of Benjamin Bloom as well as another American professor, Calvin Taylor, who extended Bloom's ideas to emphasise the importance of creativity. In addition I look at how to get and keep yourself motivated on that climb to the top of the thinking pyramid.

Although some of this chapter may seem a bit theoretical and abstract, bear with me. These ideas are in fact highly practical in terms of developing your Critical-Thinking skills. So put on stout boots, pack some sarnies and fill a water bottle, because you have a steep but rewarding climb ahead!

Building the Knowledge Pyramid with Data and Information Blocks

Philosophy starts with the question ‘What is knowledge?’, but this section trumps that by going back a stage and asking ‘What is data?’ Or maybe even something like ‘What do we mean by data? This extra step is definitely useful, because knowledge is constructed from smaller building blocks, called data or, sometimes, information.

In this section I pin down the three crucial terms of ‘data’, ‘information’ and ‘knowledge’ and describe how they're related. I discuss them in relation to education and learning and warn about when they can cause problems.

- Low-level, concrete thinking: Concerns simple observations and facts and figures, and is the foundation of the next, more elaborate, type of thinking.

- High-level, abstract thinking: Concerns relationships and things that don't exist (yet). This type of thinking can't take place without the first type.

Now I know that anything hierarchical sounds rather snooty, but it doesn't have to be that way. People certainly need both types and the hierarchy isn't one of value. But nature first makes people experts in practical, concrete thinking, and because you have to train your mind before you can do the abstract kind, a premium applies to the ability to think at the higher level.

Viewing the connections of data and information

Part of the difficulty in this area is the lack of apparent agreement on the meaning of the terms data, information and knowledge. Some dictionaries say that knowledge is the same thing as information, but that data is quite different, whereas others say that data is the same thing as information, but that knowledge is quite different. That such fundamental notions can be so loosely defined is pretty amazing. Critical Thinkers, of course, can't afford to be so lax.

- Data: At the bottom of the hierarchy. Data consists of facts and figures.

- Information: In the middle of the hierarchy. Information comprises data that has been organised to a greater or lesser extent.

- Knowledge: At the top of the hierarchy. Knowledge is certainly like information but rather purer, grander and certainly rather harder to find.

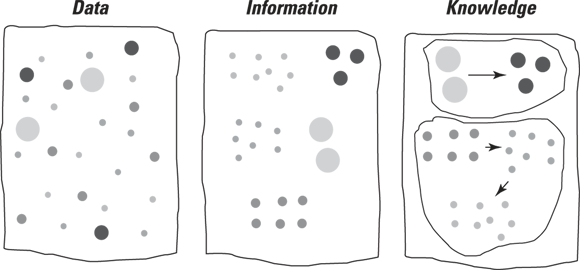

Another way of looking at the relationship between information and data is that the key factor is the degree to which items of data are interlinked. Take a look at Figure 8-1.

Figure 8-1: Constructing knowledge: A visualisation of the relationship of data to information and knowledge.

In the left hand panel, data consists of dots, showing each bit of data in splendid isolation. But in the middle panel, the data has been made ‘sense of’ and connected up. This network of connections is information. Finally, a possible view of knowledge as information further organised within collective, socially constructed linked structures.

Joining the (data) dots to create information

John Dewey, a professor of education in the United States — and something of a progressive — created his Recipe for Education, which concerns the importance of the relationship between facts (data) and how people turn them into information.

1. The human mind does not learn in a vacuum; the facts presented for learning, to be grasped, must have some relation to the previous experience of the individual or to his present needs; learning proceeds from the concrete to the general, not from the general to the particular.

2. Every individual is a little different from every other individual, not alone in his general capacity and character; the differences extend to rather minute abilities and characteristics, and no amount of discipline will eradicate them. The obvious conclusion of this is that uniform methods cannot possibly produce uniform results in education, that the more we wish to come to making every one alike the more varied and individualised must the methods be.

3. Individual effort is impossible without individual interest. There can be no such thing as a subject which in and by itself will furnish training for every mind. If work is not in itself interesting to the individual he cannot put his best efforts into it. However hard he may work at it, the effort does not go into the accomplishment of the work but is largely dissipated in a moral and emotional struggle to keep the attention where it is not held.

—John Dewey (in The Philosopher, 1934)

Another question to ask yourself is what would this argument mean in practice? In his book, Democracy and Education, Dewey gives an example of a man entering a shop showroom full of different chairs. He says that the man's past experiences will help him choose the chair that best suits him. And the more experience he has with various chairs, the better prepared he will be for selecting the correct one.

Everything he knows about chairs comes from the connections that he's created in his mind in the past, such as how comfortable they are to sit on, how difficult to clean, how strong and so on. These connections form the content of his knowledge about chairs. This kind of content is what enables people to make the new connections needed in new situations.

We respond to its [the new experience's] connections and not simply to the immediate occurrence. Thus our attitude to it is much freer. We may approach it, so to speak, from any one of the angles provided by its connections. We can bring into play, as we deem wise, any one of the habits appropriate to any one of the connected objects. Thus we get at a new event indirectly instead of immediately—by invention, ingenuity, resourcefulness. An ideally perfect knowledge would represent such a network of interconnections that any past experience would offer a point of advantage from which to get at the problem presented in a new experience.

—John Dewey (Democracy and Education, 1923)

So Dewey says that information, let alone items of knowledge, can't really be considered in isolation. Nonetheless, there is some sort of difference worth making. The following simple example illustrates the distinction in a nice, simple case.

Suppose that I measure rainfall in my garden for two years and write the figures into a notebook. The list of figures comprises the data. I then make a chart out of the data and send it to my local paper along with a letter explaining that my research shows that it has been a very wet summer. Both the chart and the view expressed in the letter are kinds of information — ways of processing the data.

As soon as I turn them into a chart — that is, organise the data — put it under a heading and make it ‘send’ a message, the data becomes information. (That's also what Carl Hempel means when he says that the transition from data to theory requires a bit of creative imagination — see Chapter 6.) Information is built up out of data, from facts. The facts don't have to be statistical ones like rain measurements, of course. They can come from all kinds of experience from listening to music to watching the sunset. (Qualitative data is descriptive information.)

Watching for errors and biases

Alas, the transition from data to information brings with it the possibility of error and bias.

For reasons such as these, someone seeing my chart could reasonably dismiss it as only my opinion (my letter to the paper certainly is), yet not, I think, the underlying data. They constitute raw and brute facts about my garden as recorded by my gauge.

Turning the Knowledge Hierarchy Upside Down

Several thinkers have adopted and adapted the knowledge hierarchy described in the preceding section, adding extra layers with particular functions to it, such as the intellectual stages of comprehension, analysis and synthesis — and some have even inverted it!

Here I describe the key aspects of this important revising work, particularly that of Benjamin Bloom, who despite his name isn't one of Batman's fantastical foes.

Thinking critically with Benjamin Bloom

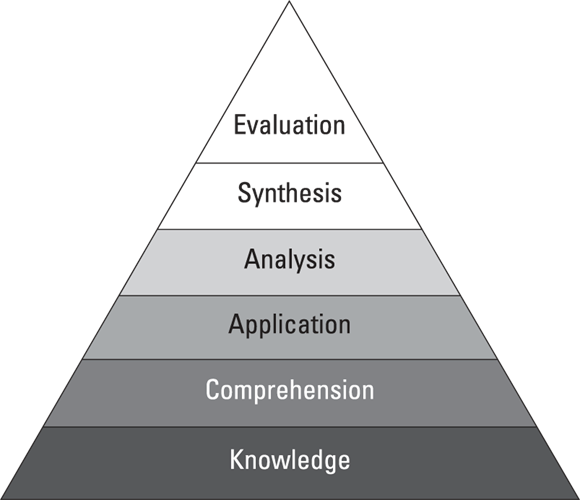

Benjamin Bloom was one of a group of educational psychologists in the US who devised a pyramid model that they said represented different ways of learning. They made it a pyramid to show that the highest form of learning, which for them was evaluating information, was ultimately based on a much broader level of information that had just been, well, learned.

Meeting Bloom's Taxonomy

Bloom wanted to promote higher forms of Critical Thinking in education, such as the use of analysis and evaluation of material, away from teachers just drilling people into remembering facts and rote learning. His system is now half a century old — yet still looks pretty ‘progressive’ in educational terms, which tells you something about how stuck-in-the-mud schools and colleges are as regards learning.

Figure 8-2: Bloom's original triangle.

- Level 1 – Knowledge: Normally people think of knowledge as something wonderful, even powerful. But Bloom defines ‘knowledge’ simply as the remembering of previously learned material. Nothing very grand about that, which is why he puts it right at the bottom of his hierarchy of learning. An example is recalling data or information, such as knowing the names of different kinds of trees.

- Level 2 – Comprehension: The next rung up, comprehension, is the ability to grasp the meaning of material. But this kind of understanding is low-level stuff too. An example is understanding texts, instructions and problems, such as being able to restate something in your own words.

Level 3 – Application: This stage is a step up the hierarchy, because it requires the ability to apply, to use, the ‘learned material’ in new situations. An example would be the practical use of concepts or skills: someone who has studied the difference between facts and inferences is able to apply this skill to certain texts in his examination of arguments.

But if you just rote learn how to apply something that you've been told about (as many people remember being drilled to do in classes), this is still learning at Level 1.

But if you just rote learn how to apply something that you've been told about (as many people remember being drilled to do in classes), this is still learning at Level 1.- Level 4 – Analysis: Only with analysis (a word which means to take things apart) does learning require an understanding of the material. You can't rote learn how to analyse things, though I suppose you can rote learn certain steps that may help you to do it. Analysing is, say, splitting up a text into its component parts to better see and understand its structure — perhaps to spot certain logical fallacies in someone's reasoning.

- Level 5 – Synthesis: Follows analysis because it refers to the ability to put information and ideas together to create something new. Creativity is involved. For example, the skills of synthesis are needed when constructing a new structure from diverse elements or reassembling parts to create a new meaning or interpretation: such as writing an original essay using multiple sources, or designing a garden choosing from a range of possible tools and approaches.

- Level 6 – Evaluation: This, the top level of the Taxonomy, is defined as the ability to assess the value (or perhaps the ‘usefulness’) of the knowledge comprehended, applied, analysed and synthesised at the earlier levels. Evaluation is really the stuff teachers wax long on (Benjamin Bloom was a professor!) about the value of ideas or materials, whether arguments work and even about the merits, skills and abilities of people. A typical example could be choosing the best book when preparing to study a new subject.

Making knowledge flow upwards

Water can't do it, but knowledge does, or at least, that's the implication of Bloom's hierarchy — the upper levels draw on the lower levels but the lower levels can't call upon the higher levels.

For more recent developments see the nearby sidebar ‘A 21st-century triangle’

Thinking creatively with Calvin Taylor

An American Professor of Psychology, called Calvin Taylor, is an important figure in the study of human creativity. His key idea was that many different kinds of skills and abilities exist and that people who're gifted at one thing may not be much good at many others.

Great news! Many people rated as low performers by the traditional measures rise to at least ‘average’ level in one or other of the new talent areas. Taylor claimed that one third of students would probably be highly gifted in at least one of the new talent areas. This new rating would thus increase their motivation, and also allow efforts to be directed more constructively towards ‘what people are good at’ instead of uselessly at what people aren't good at.

Maintaining Motivation: Knowledge, Skills and Mindsets

The importance of maintaining a positive attitude in order to succeed while studying is well known. One study found that two-thirds of students who dropped out of school cited lack of motivation as a factor. Worse still, many of the one third who remained in school were also demotivated!

This section is about how mindsets (psychological attitudes) can determine levels of skill and even abilities. I hope that this section helps you to get and keep yourself motivated on that climb to the top of the thinking pyramid, because it's up there that the most interesting things are happening.

But being motivated is not quite as simple as it's sometimes made out to be — say by P.E. teachers chasing stragglers on a cross-country run. It's not enough to always be keen to do something, or even to make yourself do something — you have to be a realistic judge of your own abilities, and most importantly, about how to build upon them.

Feeling your way to academic success!

So, plenty of research suggests that motivation is crucial to success, but this sort of evidence points at a problem.

Nonetheless, solid research shows that motivation is a key indicator not only of school or academic success but also for achievement in all areas of life. Hardly a surprise, of course. But motivation isn't something that gets taught at school or college — though a bit is trialled as in-service training in the workplace.

Perusing the paradoxical nature of praise

In the 1990s, as part of what was later called the self-esteem movement, some teachers attempted to instill more positive beliefs in their flocks by concentrating on making them ‘feel good about themselves’ and their abilities — and their prospects of success. Unfortunately, the strategy intended to improve students thinking rested on flawed thinking. The self-esteem movement assumed that assuring students that they were exceptional people, clever and talented and so on, would not only make people feel positive about themselves, but also increase their motivation to work and do well too. In fact, it had the opposite effect.

Praising students for their ability tends to produce a defensive response — afterwards students want to ‘rest on their laurels’, so to speak. The study found that students who were praised like this were more likely afterwards to try to avoid starting hard problems — because such problems seemed to carry a risk of failure (a risk of losing their ‘laurels’!).

Developing the necessary mindset

The reality is that in all areas of life, learning and achievement are about the willingness to explore new areas, and to work persistently, steadily and conscientiously. The paradox of praising someone's intelligence or skill levels is that it can discourage that person from progressing. (Which is not to say that plenty of other ways exist to discourage people too — such as calling them stupid and useless.)

- A willingness to take on challenging tasks that provide opportunities to learn new things, instead of settling for easier tasks in your comfort zone.

- The psychological skills of persistence and self-control, instead of being the person who delivers a half-done project because the deadline clashed with a favourite TV show or last week's hot weather and fresh air seemed too enticing. Check out the nearby sidebar ‘Would you pass the Marshmallow Test?’ for research in this area.

Answers to Chapter 8’s Exercises

Here are the answers to this chapter's exercises.

Dewey's recipe for education

My quick note would be: knowledge is all about connections. The rest of the material is interesting, but this is the key idea.

‘It's been an exceptionally wet summer’

I have the rainfall measurements, but the statement is still definitely my opinion. Consider the background context of the claim: with which other towns or areas do I compare my figures and over what time periods? Plenty of value judgements are lurking behind even this simple claim.

Research on the problems of demotivation

I can see at least three things that should ring alarm bells for a Critical Reader with this kind of research:

- The claim that low motivation explains students dropping out from school. The significant finding to support this view would be low motivation among dropouts and high motivation among those who see their courses through. However, perhaps in their zeal to see low motivation everywhere, the researchers also identified evidence of low morale among those who stay in school, which undermines the idea that motivation is the key factor in whether a student stays on or drops out.

- A ‘cause and effect’ law applies to this kind of claimed relationship. Students who struggle academically may become demoralised and drop-out, instead of vice versa.

- The evidence offered is too vague to be persuasive. The researchers offer no names or dates for the survey, which is essentially a bit of hearsay, or these days, ‘something read on the Internet’. Such research wouldn't stand up in a court of law — it doesn't really stand up in an essay!

One of the key insights of this chapter is that what you know is less important than how you know it. That sounds a bit cryptic but boils down to the difference between two types of thinking:

One of the key insights of this chapter is that what you know is less important than how you know it. That sounds a bit cryptic but boils down to the difference between two types of thinking: Read through and then test your skills of comprehension on the following argument from Professor Dewey on democratic education. Try to reduce it to just one line, and then compare what you extract to my note at the end of this chapter (you can read the whole article at

Read through and then test your skills of comprehension on the following argument from Professor Dewey on democratic education. Try to reduce it to just one line, and then compare what you extract to my note at the end of this chapter (you can read the whole article at

In the measuring rainfall scenario in the preceding section, for example, I could easily introduce distortions through the decisions I take for things such as which readings to include (and which to leave out), the scales used for the axes on my chart or maybe even my choice of measuring equipment. Perhaps, to strengthen my point, I might have been tempted to start the readings a bit later than I originally intended to avoid a dry period in the spring!

In the measuring rainfall scenario in the preceding section, for example, I could easily introduce distortions through the decisions I take for things such as which readings to include (and which to leave out), the scales used for the axes on my chart or maybe even my choice of measuring equipment. Perhaps, to strengthen my point, I might have been tempted to start the readings a bit later than I originally intended to avoid a dry period in the spring!