Chapter 4

Assessing Your Thinking Skills

In This Chapter

![]() Trying out your Critical Thinking skills

Trying out your Critical Thinking skills

![]() Steering clear of thinking errors

Steering clear of thinking errors

![]() Appreciating the value of emotional and creative intelligences

Appreciating the value of emotional and creative intelligences

I do not know what I may appear to the world, but to myself I seem to have been only like a boy playing on the sea-shore, and diverting myself in now and then finding a smoother pebble or a prettier shell than ordinary, whilst the great ocean of truth lay all undiscovered before me

— Isaac Newton (as recorded in Memoirs of the Life, Writings, and Discoveries of Sir Isaac Newton, 1855, by David Brewster)

Newton was a pretty clever chap, but a key part of his cleverness was being open-minded and curious, and thinking in unconventional ways. These are the hallmarks and the key skills of the Critical Thinker. And the good news? Everyone can develop them. So, if you can read only one chapter in the book — make it this one! It offers an overview of all the aspects of thinking that people often overlook. For too long courses supposed to help you think have plodded through various kinds of ‘rules’ and exercises that use only a tiny, narrow kind of ‘thinking’.

In this chapter, I explain why these days informal logic is moving away from its focus on dissecting arguments that seem valid but aren't, towards a view of truth and the appropriate use of arguments that puts a much greater emphasis on the context. The skills needed turn out to be much more social than mathematical.

After all, if arguments are restricted to those involving clear propositions, most of the issues people encounter in real life, or most of the mass messages they're bombarded with every day, aren't ‘arguments’ at all! Traditional Critical Thinking too often focuses on what's in an argument — and neglects to look at what's been left outside, whether inadvertently or deliberately. This chapter helps you to avoid that pitfall!

Discovering Your Personal Thinking Habits

This section concerns the theory that because humans are animals that live in groups, their minds have a tendency to think sociocentrically, that is, to think like everyone around them.

First of all, this section tips you off about what's too often wrong with education, and why it fails to give people any real training in Critical Thinking. Then, you get a chance to find out how you measure up to the ideal, with my own specially crafted thinking test. Don't worry; it's quite fun and definitely an eye opener.

Identifying the essence of Critical Thinking

It's true that no one seems to have heard of him nowadays, but this section gives you a taste of the views of the man who, in many ways, started the whole Critical Thinking ball rolling about a century ago, and whose ideas continue to influence the way the subjects is taught now.

Over a century ago William Graham Sumner published a ground-breaking study of ‘how people think’, which blended elements of sociology and anthropology, called Folkways (1906). Sumner is not particularly well known, but he was a remarkable man, a true polymath (expert at everything), with a keen interest in public affairs.

Schools make persons all on one pattern, orthodoxy. School education, unless it is regulated by the best knowledge and good sense, will produce men and women who are all of one pattern, as if turned in a lathe. An orthodoxy is produced in regard to all the great doctrines of life. It consists of the most worn and commonplace opinions which are common in the masses. The popular opinions always contain broad fallacies, half-truths, and glib generalizations.

—William Graham Sumner (Folkways, 1906)

Everyone is like this — fortunately, you're now aware of it! The solution, or antidote, according to Sumner is a hefty dose of Critical Thinking skills in life and in education:

Criticism is the examination and test of propositions of any kind which are offered for acceptance, in order to find out whether they correspond to reality or not. The critical faculty is a product of education and training. It is a mental habit and power. It is a prime condition of human welfare that men and women should be trained in it. It is our only guarantee against delusion, deception, superstition, and misapprehension of ourselves and our earthly circumstances.

Criticism is the examination and test of propositions of any kind which are offered for acceptance, in order to find out whether they correspond to reality or not. The critical faculty is a product of education and training. It is a mental habit and power. It is a prime condition of human welfare that men and women should be trained in it. It is our only guarantee against delusion, deception, superstition, and misapprehension of ourselves and our earthly circumstances.

—William Graham Sumner (Folkways, 1906)

For Sumner, education should be about an insistence on what he calls ‘accuracy and a rational control of all processes and methods’, coupled with a habit of demanding logical arguments to back up all claims along with an indefatigable willingness to rethink, and if necessary to go back and start again.

Testing your own Critical Thinking skills!

To discover how you measure up to Sumner's ideal, try out the test in this section. After all, tests and Critical Thinking skills seem to go hand in hand, like fish and chips, or maybe Dracula and garlic.

The questions conventionally used to measure Critical Thinking skills range widely across a lot of areas — verbal skills, visual skills and of course number skills — but I doubt whether they measure anything that deserves to be called Critical Thinking. More important than that, plenty of recent research indicates that such tests are poor indicators of how anyone may do in any real-world job or situation. The tests only seem to show how good you are at doing, well, tests!

Question 1: Brain teaser

A famous architect builds a hexagonal holiday house in such a way that windows on each side point south to catch the sun. The first day that the new owners are in the house, they're amazed to see through the windows a large, furry animal slowly walk right round the house!

Two skill-stretching queries are: What colour is the beast? And how do you know?

- (a) It's brown, because most large furry animals are brown.

- (b) It's black . . . because bears are black.

- (c) It's white . . . because of the specifications for the windows of the house.

- (d) There's no possible way to answer this and if this is Critical Thinking, it's stupid.

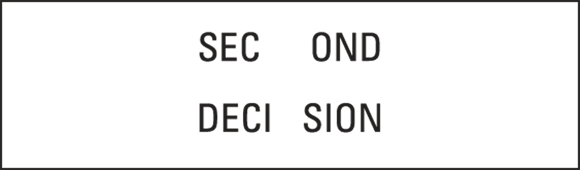

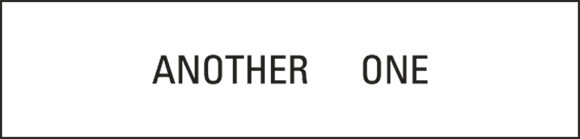

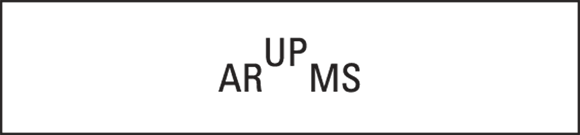

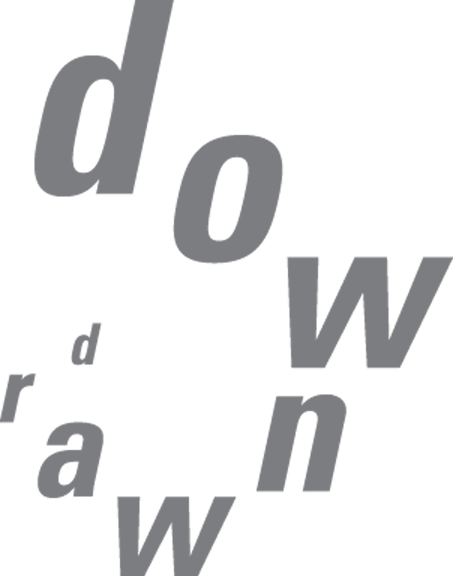

Question 2: Word pictures

Each picture is made up of words, but also represents a common saying. Can you see what the everyday adage is?

- (a)

- (b)

- (c)

- (d)

Question 3: Spot the fallacy!

In the following example, try to pin down the precise problem with the argument. (For more on types of argument errors, check out Chapter 16.)

Many vegetarians believe that killing animals is wrong. If they could have their way, anyone who eats meat should go to prison.

- (a) Slippery slope

- (b) Begging the question or circular argument

- (c) Straw man

- (d) Non sequitur

- (e) Ad hominem

- (Tip: Don't worry if you haven't a clue what these are about — it's just jargon. But that's one thing a lot of these tests measure. Skip to the answers now, if you want a quick decoding of the language in this question.)

Question 4: Spot another fallacy!

In the following example, try to pin down the precise problem with the argument. (You can check up on the definitions for the argument types in the answers as well as find out in more detail about some more in Chapter 16.)

Tea and coffee both contain caffeine, which is a drug. Excess caffeine intake has dangerous side effects, potentially including heart attacks. Therefore, drinking tea or coffee is dangerous.

- (a) Slippery slope

- (b) Begging the question orcircular argument

- (c) Straw man

- (d) Non sequitur

- (e) Ad hominem

Question 5: Type-casting

Which one of the following scenarios best describes a situation in which emotion rather than logic or rational thought has been allowed to decide the outcome?

- (a) Mary hates looking at herself in the mirror. She thinks she has got too fat! So she decides to take up jogging.

- (b) Someone has just telephoned the college to say that they've planted a bomb in one of the buildings. Even though nothing like it has ever happened before, the school principal orders all the students and staff out of the buildings and tells everyone to go home.

- (c) Mark has a job interview at a Silicon Valley computer firm and wants to look the part at his interview. He buys some computer magazines and looks at the pictures in them of the kind of people who seem to work in high-tech businesses, and tries to make himself fit that style.

- (d) Jenny wants to buy a new car, but the model she likes best and can afford has high carbon emissions. She worries this may be the kind of buying decision that if lots of people took would contribute to climate change and be bad for the planet. She wants to ‘be the change’ she believes in, so she gets a different car that's less suitable for her needs but has a better environmental ‘footprint’.

- (e) The publisher is amazed at the new sales figures for Critical Thinking books, which are much higher than anyone had predicted. It decides in future to take very little notice of anything the marketing folk in the firm say.

Question 6: More type-casting

Jenny designs wallpaper for a big home decoration business. She's good at her job, but is caught out when a new and enthusiastic man joins the company and asks her for ideas for a new marketing campaign for the wallpapers? Marketing and advertising aren't her area of expertise at all.

Should she:

- (a) Find out what other wallpaper manufacturers are doing to market their designs, and arrange to chat with people in the marketing department to get their views and share a few ideas. (Brainstorm it too, maybe.)

- (b) Email the new man in marketing (copy to the CEO, colleagues) that she's the wrong person for this task, because she knows nothing about marketing. Suggest that if he can't think of anything himself, he should look around for someone with the right skills.

- (c) Politely acknowledge the request for info, and promise to deal with it as ‘a priority’. Then make sure she's not available until long after the decisions have all been taken anyway by someone else. After all, they'll probably be better qualified to handle it anyway.

Question 7: Business skills

You're stressed out about the mountain of work piling up and realise that you can't possibly finish it all. What's the smart way to meet the challenge?

- (a) Do the best you can, if necessary working evenings and weekends, and skipping meals, to get it all done in some form or another.

- (b) Send a note to everyone involved stating clearly that your workload is excessive and you can only do a proper job if some of the deadlines are extended and less new work is set.

- (c) Recognise that it is your feelings that are the key factor — you feel tired and stressed! Reduce your working hours, take more time off, have proper meals and maybe go somewhere nice at the weekend too.

Question 8: Time management

In your job you always seem to have several tasks to complete by the end of the week. What's the most efficient way of organising your time?

- (a) Be linear: Take the jobs one thing at a time, not starting a new task until you finish with the one at hand.

- (b) Multitask: Tackle everything at once, because this stops you getting bored and some areas overlap, thus immediately saving time.

- (c) Recognise that the problem isn't your way of working but the amount of time you have. Take a strict look at your daily timetable and clear out all the unnecessary jobs and commit yourself to putting in extra hours until the backlog is cleared.

Question 9: Justice for TV watchers

Have a look at this argument:

In Britain, every household pays the same amount for their televisions, regardless of how rich the household is, or how many TVs they have — or how much they watch them! Surely this is unfair. Instead, TV should be made a subscription service so that those who watch the most pay the most. This wouldn't only be fairer, but could also bring in more revenue.

Which of the following arguments uses the same principle as the one above?

(Hint: The question isn't about whether the argument is a good one or not, but rather about its structure.)

- (a) Things should only be available free to people if they can't afford them otherwise.

- (b) Discounts on bus and train fares should be available to people who travel most.

- (c) Rich people should pay a surcharge on their houses to help poor people who don't have a home at all.

- (d) Television channels should be funded by general taxation so that the richer you are the more you pay.

- (e) Internet sites that make a lot of money from advertising shouldn't be able to charge for access.

Question 10: Car rentals

Take a deep breath: here's the maths question!

Bodge-It Rental Cars rent out cars at a cost of £19.99 per day plus free mileage for the first 100 miles. An extra charge of £1.00 applies for every mile travelled over 100 miles.

Luxury Limos charge £100.00 per day for just taking the car out of their showrooms, and 20 pence for every single mile travelled.

How many miles would you need to travel before it paid for you to hire a Luxury Limo?

- (a) 101

- (b) 131

- (c) 151

- (d) 171

- (e) It's always cheaper to hire Bodge-It

Bonus question: The riddle of the old-fashioned brew

Hint. This is another maths question and is based on a question for one of the big Critical Thinking testing organisations.

The Munchkins family makes tea following the traditional rule: ‘warm the pot, and add one spoonful of tea per person plus one for the pot’.

The family used to buy a packet of Green Lion tea every week but because Grandma came to live with them, their tea buying has gone up. Now, every fifth week they buy an extra packet of tea.

Your question is: how many people were at home before Grandma arrived?

Busting Myths about Thinking

You know how your mind sort of glazes over when asked to list all the major exports of Bulgaria? Or to calculate how long a swimming pool will take to fill if a tap drips at the rate of 2.5 cm cubed every minute? But there are people who can do such things and you've probably got used to the idea that they're the smarties in the packet. In this section I describe some misconceptions that people have about thinking, rationality and logicality, and put in a word for some very different ways of seeing intelligence.

Accepting that sloppy thinking can work

In this section I look a scientific look at unscientific thinking, splitting it into two main types, and pick out when it has to be avoided, and when, maybe, it should be allowed a little more space.

- Motivational or ‘hot’ illusions: These stem from the influence of emotions and assessments of personal interests upon the reasoning. For example, most people assume that their views now will stay the same for the foreseeable future, and fiercely defend them, even though, in reality, most people's views change and evolve all the time.

- Cognitive or ‘cold’ illusions: Stem from errors in your reasoning: things like mixing up correlation and causation (two things may keep happening together but that doesn't actually mean one caused the other) or having an unconscious bias in favour of information which fits with your existing views.

Many researchers consider that because both kinds of errors are so common, indeed almost universal, they must have some kind of evolutionary purpose, indeed advantage, for the human species.

Plenty of research also suggests that people who distort assessments in favour of their own self-interest, perhaps inflating their achievements and capabilities in job interviews or in reports, do better in life. Perhaps, paradoxically, self-deception can enhance people's motivation, mood and even productivity.

Trumping logic with belief

In one study (by Jonathan Evans, Julie Barston and Paul Pollard) people were asked to evaluate arguments expressed in formal style — as syllogisms. (A syllogism is an argument which consists of two premises, or starting assumptions, followed by a conclusion which is supposed to follow logically on from it.)

The researchers were really investigating the extent to which people simply accept arguments they encounter that support existing beliefs, without any real examination. This idea (also explored in Chapter 2) connects to the one about the human brain being ‘hard-wired’ after aeons of hunting wildebeest with sticks, to take short cuts rather than hang about to be gobbled by lions.

- All dogs have fur.

- Boa is a python.

- Therefore, Boa doesn't have fur.

Valid or invalid?

- Some cats like milk.

- Toby is a cat.

- Therefore, Toby likes milk.

Valid or invalid?

- Red berries are dangerous to humans to eat.

- Raspberries are a kind of red berry.

- Therefore, raspberries are dangerous.

Valid or invalid?

I don't make you wait for the answers: neither of the first two arguments is valid. Although pythons don't have fur, the first argument hasn't proved that — it doesn't even look like it will! So, I hope you weren't taken in. In the second argument, you may have been tempted to ‘give the argument some rope’, because Toby probably does like milk if he's a cat. Nonetheless, if all you know is that ‘some’ cats like milk, again the conclusion isn't proved.

The third argument is sort-of-valid. I say sort-of because the wording contains a bit of fudge. The first premise ‘Red berries are dangerous to humans to eat’ is true in one sense and not true in another. Far too many arguments depend on such ambiguities!

Anyway, with this one, if you take the claim as being that all red berries are dangerous, the argument is valid, even though the conclusion isn't true. Confused? That's because in logic, a valid argument means that if the starting assumptions are true, then the conclusion must be too; so yes, if all red berries were really dangerous the argument is fine. In real life though, the first premise isn't true. In real life only some red berries are dangerous (and raspberries aren't one of them).

The common-sense intuition to take the starting statement as saying only that ‘lots of red berries are dangerous to humans to eat’ makes the argument invalid, because you can't draw any conclusions in this case about any particular kind of red berry.

Confirming the truth of confirmation bias

Scientists, for all their reputation as dispassionate sifters of data, often fall easy prey to this bias — repeatedly rejecting experiments that come to the ‘wrong’ conclusions. The history of science is full of cases in which scientists carry out an experiment to prove their theory, but if the results come back disagreeing, instead of rethinking the whole theory, they suspect the experimental set-up.

Some great scientific discoveries arose through such behaviour, but also many erroneous ideas and theories were perpetuated long after they should've been abandoned.

- Argument from authority: Where someone assumes that he must be right because he's confident that he knows more than his opponents on certain topics.

- Ad hominem (or directed ‘at the person’) arguments: Where the views of others are dismissed out of hand, perhaps in a condescending or even insulting manner. This bias may lead people to errors in their recall or selection of facts. Who does the washing-up? ‘It's always me!’

Argumentative self-control and Critical Thinking

A good place to start is with some great tips prepared by two Dutch professors, Frans van Eemeren and Rob Grootendorst, as what they call ‘a code of conduct for reasonable discussions’. These appear in a book, alarmingly called Advances in Pragma-Dialectics (2002), where they set out their ‘ten commandments’ to guide anyone in a debate. Here's my take on their ‘best’ four ideas (the others become rather technical and even repeat the same broad points). Therefore, to explain your approach to argumentative self-control, you can, if you like, say that you're following Martin Cohen's Four Commandments, though it doesn't have a great ring, I admit.

Rule 1: Don't stop your opponent from advancing a new position or challenging your position. The authors call this the ‘freedom’ commandment, and it underpins many of the others.

Rule 1: Don't stop your opponent from advancing a new position or challenging your position. The authors call this the ‘freedom’ commandment, and it underpins many of the others.- Rule 2: Both sides must defend and justify their positions when asked to.

- Rule 3: Don't attack positions that no one has put forward. No matter how much fun it is and how clever it makes you look!

- Rule 4: Don't use anything except arguments to advance your position. For example, don't appeal to people's sentiments, let alone their prejudices or fears.

Rules for arguments are all very well, of course, and few people disagree with the general principles. But arguments in the real world aren't so easily sorted out. After all, they often happen because people make genuine mistakes, or have been misled by some erroneous information — such as something they heard on the radio or read in the newspaper or in Wikipedia! Add in distortions caused by strong emotional attachments and you have a rule book that isn't really sufficient for sorting out many arguments.

‘It's only logically consistent, Captain’: Practical wisdom is virtuous

The ability to ‘recognise salient facts’, ‘open-mindedness in collecting and appraising evidence’, ‘fairness in evaluating the arguments of others’ and so on all look pretty useful and should help avoid mistakes in life. Funnily enough, the list of good instincts looks very like Aristotle's ancient ‘intellectual virtues’, written over 2,000 years ago (for background, see the nearby sidebar ‘Getting practical with Aristotle’).

Another virtuous habit useful for anyone involved in an argument is the ability to contemplate potential objections and alternative views. Doing so offsets the two-fold tendency of humans: to overlook what contradicts their existing beliefs and views; and to rest comfortably on sources confirming their biases.

In their book Logical Self-Defense (2006), Ralph Henry Johnson and J Anthony Blair see this problem as arising because ‘the act of reasoning is rarely carried out in a situation that lacks an emotional dimension’, that is, personal interests and involvements often distort the way people treat information and the way they argue, and emotional commitments make it harder to look at an issue from someone else's point of view.

Exploring Different Types of Intelligence: Emotions and Creativity

This section looks at two important but much neglected kinds of intelligence: the emotional and the creative kinds. Did you hear about IBM's powerful computer — the one that outfoxed the world's top chess masters? Well now it's struggling to develop these intelligences too. So keep ahead here.

Thinking about what other people are thinking: Emotional intelligence

Emotional intelligence skills

Goleman suggests that emotions play a much greater role in thought, decision-making and individual success than is commonly acknowledged.

Within the family, with friends and in the workplace, emotional intelligence (some people call it EQ, for emotional quotient, to contrast it with intelligence quotient, or IQ) means being able to listen to, predict and understand other people, and to know the right words to say.

- Spot emotions: Be aware of other people's emotions. Try to notice and read nonverbal signals such as body language and facial expressions in those around you.

- Reason with your emotions: Use your emotions to guide your thinking, for example to help you prioritise. A common error is to give too high a priority to trivial things that are urgent, and neglect important things that don't have an obvious deadline. Using your EQ can counteract this tendency.

- Understand emotions: Emotions can conceal a wide range of causes. For example, if someone is getting angry, it may be because of what you've just done or are currently doing (which may trigger a defensive response from you). But it may also be because they just had some bad news (say, a speeding ticket on the way to work) or maybe they're just overtired. (In Dostoyevsky's famous book, Crime and Punishment, the detective Porfiry Petrovich displays great emotional intelligence and empathy in his investigation of Rodion Raskolnikov.)

- Handle your emotions: The ability to do this is the final key aspect of emotional intelligence. For example, an athlete may be tempted to perform a celebratory trick in the last lap — and maybe lose their focus — and the race. This actually happened at the 2006 Winter Olympics when snowboarder Lindsey Jacobellis made the mistake of celebrating her gold medal before actually having actually won it and ended up with her face in the snow.

EQ not IQ

Unlike IQ, which is gauged by highly standardised tests (such as the Stanford-Binet ones), EQ doesn't lend itself to any single numerical measure. After all, by definition it's a complex, multifaceted quality representing such intangibles as self-awareness, empathy, persistence and social skills. Some aspects can, however, be quantified. Optimism, for example. According to some psychologists, how people respond to setbacks — optimistically or pessimistically — is an indicator of how well they succeed in life.

Finding out about fuzzy thinking and creativity

Being logical is good for some kinds of problems and being emotionally in tune is useful for many more. But plenty of situations require something rather harder to pin down: creative insight.

In these kinds of situations, lots of possible answers can apply: in a sense, anything goes and the more the merrier too. It's not just at advertising confabs looking for new marketing strategies, or design consultancy brainstorms coming up with new ideas for the local supermarket car park that benefit from creative insight, but so too do hard-nosed economists trying to work out how to reboot the economy, and even doctors wondering why so many people seem to be getting colds!

Yet in many situations people still want to end up with something that commands wide acceptance, rather than just their own idiosyncratic opinion or view. In such cases, creative thinkers have to be prepared to risk losing arguments and admit that they've gone up blind alleyways.

Answers to Chapter 4’s Exercises

Here are my answers to this chapter's test.

Feedback on the Critical Thinking skills test

1: Brain teasers

The point of this little teaser is that the important information is present in the dull-looking line about the windows all facing south. The house must be at the North Pole, and the furry animal is thus white — a polar bear. It's easy — but unwise — to overlook the dull.

2: Word pictures

Each picture is made up of words, but also represents a common saying. What are they?

- (a) split second decision

- (b) one after another

- (c) up in arms

- (d) downward spiral

3: Spot the fallacy!

Slippery slope arguments are ones where someone plays on the fact that often the line between two things is hard to draw, but nonetheless, there is a generally accepted difference to be respected.

Begging the question or circular arguments assume at the outset what is supposed to be demonstrated later on.

Straw man arguments pose ridiculous examples only to easily knock them down later.

Non sequiturs, from the Latin, are claims that do not actually follow in any logical sense.

Ad hominem, again from the Latin, are arguments which attack the person making the claim, rather than deal with what they are saying.

You can legitimately say that this argument contains many fallacies, but I claim that the ‘Straw Man’ is the most relevant one to note. No vegetarians argue this and so the claim that they do is, well, made of straw.

4: Spot another fallacy!

This fallacy is ‘begging the question’ meaning that it is a circular argument. The idea is that the explanation used to back up your point relies on the assumption of what it's supposed to be proving.

5: Type-casting

I'd plump for (d) — Jenny and her new car — but honestly, you can make a case for most of them being rooted in ‘irrationality’. These questions are popular in Critical Thinking tests, but they're really rather subjective.

6: More type-casting

Well, I think you can guess that (a) is the ‘politically correct’ answer, especially in business circles. After all, she may not know about marketing but she does presumably know what's good about her designs. But in the real world, I have sympathy for the ‘directness’ of response (b), and in the very real world, the person who uses the third tactic I suspect will be the one who goes furthest!

7: Business skills

The correct answer is (c)! Amazed? But that's the view of most business-skills authorities who offer such questions. In the real world, I suspect answer (a) will get you further.

8: Time management

I think the correct answer is to prioritse — which I didn't put in here! Call it a trick question.

9: Justice for TV watchers

This is a very confusing question. It seems to be about ‘ability to pay’, but in fact, it isn't. Literally, the argument is those who use a service most should pay most. (If poor people watch lots of TV — they should pay most!) The only argument here putting that line is argument

(c) which seems to be saying the opposite: ‘Rich people should pay a surcharge on their houses so as to help poor people who maybe don't have a home at all.’

It would be easy to misread the question and plump for argument (d) ‘Television channels should be paid for by general taxation so that the richer you are the more you pay.’ I'd call this almost a trick question.

10: Car rentals

It's 151. It took me absolutely ages to work it out. Turn it into an equation, though, and it's easy to solve:

50 + (mileage – 80) — 1 = 60 + (mileage) — 0.5

(Note that multiplying by one is just for demonstration purposes.)

Bonus question: The riddle of the old-fashioned brew

The key thing here is that the amount of tea being drunk is up 25 per cent. You also know that Grandma is one person. One person thus requires one extra packet of tea every fifth week, which is a complicated way of saying that one packet of tea lasts one person five weeks, or that one person would be drinking one fifth of a packet in a week.

So previously, when one packet lasted a week, five spoons must have been in the pot, which corresponds not to five people but four people plus that extra spoon ‘for the pot’. The answer is therefore four people, and previously four spoons of tea must have been in the pot.

I've seen people discussing questions like this one on the Internet: they sometimes get the right answer — but for the wrong reasons, which may be okay in a test but not in real life. One person advising all the others even stated confidently that the ‘spoon for the pot’ was ‘completely irrelevant’. But of course, it isn't!

Despite the title, the message of his study is anything but whimsical: he says that people's thinking skills are systematically drained out of them in schools, colleges and the workplace! Sound plausible? The trouble is, modern education is rooted in assumptions about the need to turn individuals into citizens ready to play a role in society. As he puts it:

Despite the title, the message of his study is anything but whimsical: he says that people's thinking skills are systematically drained out of them in schools, colleges and the workplace! Sound plausible? The trouble is, modern education is rooted in assumptions about the need to turn individuals into citizens ready to play a role in society. As he puts it: Nonetheless, lots of people do think such skills are terribly relevant and important, and they certainly tell you something, even if its only how well you'd do in a Critical Thinking skills paper. Naturally, a true Critical Thinker will always try new things and be quite happy to tackle tests like this both in the spirit of fun and to discover something about their own thinking patterns and preferences. So here's one to try. The time allowed for the ten questions is 30 minutes. You can find the answers at the end of this chapter — but don't cheat!

Nonetheless, lots of people do think such skills are terribly relevant and important, and they certainly tell you something, even if its only how well you'd do in a Critical Thinking skills paper. Naturally, a true Critical Thinker will always try new things and be quite happy to tackle tests like this both in the spirit of fun and to discover something about their own thinking patterns and preferences. So here's one to try. The time allowed for the ten questions is 30 minutes. You can find the answers at the end of this chapter — but don't cheat! Psychologists distinguish between two kinds of errors that people make when reasoning:

Psychologists distinguish between two kinds of errors that people make when reasoning: That being said, cognitive illusions can also lead to unwise decisions and errors due to unrealistic assessment of risks or plain wishful thinking, or from self-deception (check out the nearby sidebar ‘Everyone's a bit better than average’). The errors may lead to conflict due to resentments created by prejudice, scapegoating and so on. Other unconscious biases may lead to the phenomenon known as attitude polarisation, which is when two sides with perhaps only minor differences end up much further apart, because each side interprets information in distorted ways that reinforces their prejudices.

That being said, cognitive illusions can also lead to unwise decisions and errors due to unrealistic assessment of risks or plain wishful thinking, or from self-deception (check out the nearby sidebar ‘Everyone's a bit better than average’). The errors may lead to conflict due to resentments created by prejudice, scapegoating and so on. Other unconscious biases may lead to the phenomenon known as attitude polarisation, which is when two sides with perhaps only minor differences end up much further apart, because each side interprets information in distorted ways that reinforces their prejudices.