Whether you work in a government facility, in academia, or for a contractor supplying video to the government, your work must meet the accessibility standards of Section 508 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 (see www.section508.gov). As one regulation states, “All training and informational video and multimedia productions which support the agency’s mission, regardless of format, that contain speech or other audio information necessary for the comprehension of the content, shall be open or closed captioned.” That’s a big net that catches a lot of government and academic videos.

This chapter starts with a look at closed-captioning issues such as what to caption, and how closed captions differ from DVD subtitles. Once you decide to caption, your next step is to set captioning standards to ensure consistency within and among your video productions. The following section will examine the most important issues to consider when establishing your captioning standards.

Then I’ll describe the captioning workflow, starting with how to format your files for import into a captioning program. Using a remarkable program called MAGpie, we’ll synchronize a set of sample captions to a video file and integrate the results with Windows Media, RealVideo, and QuickTime videos.

If you’re producing both streaming videos and DVDs, you’ll need to produce one text stream to work with both formats. As a final step, I’ll identify the tools and suggest a workflow for doing just that.

Before going further, let me acknowledge the kind assistance from two captioning professionals who helped shape this chapter. First, thanks to Cynthia M. King, Ph.D, executive director, academic technology at Gallaudet University, for providing access to her staff and a thorough “tech read” of the chapter. Also, Andrew Kirkpatrick from the Media Access Group at WGBH in Boston provided invaluable insight into the inner workings of MAGpie2, the captioning tool from the Media Access Group, and how closed captions are implemented by Apple, Microsoft, and Real in their respective formats. I also appreciate Andrew’s careful “tech read” of this chapter.

Note that closed captions play a broader role than the subtitles you may have seen in foreign movies or DVDs. That’s because most subtitles assume that the viewer can hear, but doesn’t understand the language. For this reason, noises such as gunshots, screams, music welling up, dogs barking, and cars beeping may not be noted in the subtitle text.

Closed captions assume that the viewer cannot hear. For that reason, to comply with Section 508, closed captions must “contain speech or other audio information necessary for the comprehension of the content.” If you’re producing a DVD for government use, you’ll need to add all the audio cues necessary to satisfy this requirement.

It’s important to note that captioning for broadcast and captioning for streaming video and DVD involve completely different techniques and technologies. Captioning for broadcast involves expensive hardware and software to insert the captioned text directly into the video file.

In contrast, captioning for streaming and DVD involves creating text files in inexpensive (or free) shareware programs and then linking the text file to the video file for streaming, or importing the text file into the DVD authoring program to create subtitles. While some broadcast captioning systems can export text strings for DVD and streaming, if you’re not concerned with broadcast, inexpensive programs function just as well.

This chapter focuses entirely on closed captioning for streaming video and DVD and does not address broadcast-specific requirements or technologies. It also focuses solely on the captioning requirements for on-demand files; live event captioning uses a different set of rules and obviously different transcription requirements.

There are few absolute right or wrong precedents in captioning; what’s most important is to be consistent in how captions are created and applied. Before creating your first closed-captioned text, you should define the conventions you’ll use to produce your closed captions. I’ll cover a list of decisions to consider when creating your captioning standards, along with some suggested approaches.

In formulating these standards, I relied heavily on the standards and practices used by the Media Access Group at WGBH in Boston, the world’s first captioning agency. The people there have been delivering accessible media to disabled adults, students, and their families, teachers, and friends for more than 30 years. Certain areas I address are largely paraphrased from materials from the Media Access Group, with the group’s gracious permission. You can find the Media Access Group’s excellent captioning the guide at http://main.wgbh.org/wgbh/pages/mag/services/captioning/faq/sugg-styles-conv-faq.html#copy.

The most detailed captioning guide I found (with help from Judy Harkins at Gallaudet University’s Technology Access Program) was produced by the Captioned Media Program (CMP) of the National Association of the Deaf, which can be found at www.cfv.org/caai/nadh7.pdf. If you’re looking for one document that contains highly detailed recommendations for nearly all caption-related questions (and why wouldn’t you?), this is it.

The CMP’s style guide incorporates consumer research performed by the Technology Access Program at Gallaudet University and summarized at tap.gallaudet.edu/nsi_recom.htm. This link contains a great document for understanding the philosophy behind the CMP practices and procedures. Another resource addressing a variety of captioning issues, including closed captioning tools, is Gary Robson’s FAQ, found at www.robson.org/capfaq.

For a general perspective on the practices followed by several captioning services, check out Joe Clark’s article in Print magazine, “Typography and TV Captioning.” Though originally published in 1989, it’s still a great (and relevant) read, and can still find it online at: www.joeclark.org/design/print/print1989.html, and other valuable material from Joe at www.joeclark.org/access/captioning.

The first decision you’ll make in defining your captioning standard is how many lines of captions. Television captions tend to be three or four lines, while most Hollywood DVD titles tend to use two lines.

Most streaming producers also use two lines. Some companies, such as the Media Access Group, add a third line at the top of the caption to identify the speaker (Figure 11.1). Unless you have a strong reason to choose otherwise, two lines of text is probably a good place to start. More on the speaker identification issue later.

There are three styles used to make captions appear and disappear from the screen:

Roll-up captions—. These captions scroll up like credits at the end of a movie, line by line, and remain onscreen until pushed out of the viewing area. In a three-line caption, the first line remains onscreen until the fourth line appears to push it off screen.

Paint-on captions—. This technique literally paints the captions onscreen from left to right. Each letter is filled in individually and sequentially, one line after another, until the caption area is fully painted on. The caption area then goes blank for a moment and the next caption begins painting again. Note that paint-on captions are available only for TV, not for streaming media or DVD.

Pop-on captions—. These captions appear all at once and remain onscreen until removed (at which point the caption area goes blank) or is replaced by the next caption.

Paint-on appears to be the preferred approach for movies and other nonlive media, and is the only approach sanctioned by the Captioned Media Program. If you choose Roll-up captions, most of the rules identified next apply, except that two “greater than” symbols should appear before each new speaker.

For example, the text in Figure 11.1 would appear as follows:

>> KEN: Joining us here is Mr. Jan Ozer.

Sometimes in newscasts, three “greater than” symbols are used to indicate a change from one story to another.

Let’s step back for a minute and consider what’s actually happening when you convert a script or transcribed speech into captions. Most conversations involve a give and take between two or more individuals. Sometimes a comment from one might be a single word like “yes” or “no.” Sometimes a response can be three or four sentences long, involving dozens of words.

Irrespective of the length of the speaker’s comments, during captioning we break them down into their most comprehensible chunks. One very relevant chunk is the number of lines within a caption. If you choose two-line captions, this means that all dialog must be subdivided into chunks of two lines each.

However, each line must also be limited to a certain number of characters for optimum readability. For example, the Captioned Media Program requires a maximum of 32 characters per line—a hard limit due to the limitations in television displays. While streaming and DVD formats have more flexibility, you should try to average between 30 and 35 characters per line, including spaces.

So to recap, you must subdivide all speech into two-line chunks, each containing approximately 30 to 35 characters per line. It doesn’t matter if you’re captioning Rhett Butler’s famous last words in Gone With the Wind (“Frankly, my dear...”) or the Presidential State of the Union address; you’ve got to break it down in the same way.

At a high level, when dividing up your text, understand that people don’t read letter by letter or even word by word, they read in chunks of words, or phrases. For this reason, captions are most readable when divided into logical phrases, both within the two lines in a caption and from caption to caption. I’ve illustrated this in Table 11.1.

Table 11.1. Breaking captions into logical phrases.

Good Logical Phrasing | Poor Logical Phrasing | |

|---|---|---|

Caption 1: | Joining us here is Mr. Jan Ozer, | Joining us here is Mr. Jan Ozer, a contributing |

Caption 2: | a contributing editor for New York’s PC Magazine. | editor for New York’s PC Magazine. Welcome Jan. |

Caption 3: | Welcome Jan. |

The phrasing on the right violates both rules; there’s poor phrasing within Caption 1 (breaking up a name) and between Captions 1 and 2 (breaking up a title). If you read both versions out loud, you’ll instantly see that the first column reads much more naturally. “If it sounds like good phrasing, it probably is good phrasing” is the general approach, but for some truly definitive rules, go to page 10 of the Captioned Media Program document I referenced earlier.

Column 2 (right) violates another rule of segmentation: a period should always end a caption (though not all captions have to end with periods). Specifically, in Caption 2, where the first sentence ends with “Magazine,” the next sentence should start a new caption, as it does on the left.

Here’s what we’ve learned from this section (with one additional point):

Segment multiple lines within a caption into logical phrases.

Segment multiple lines of captions into logical phrases.

The end of a sentence ends a caption line.

Start a new caption each time the speaker changes.

Now that you have your text divided into captions, it’s time to decide how to present the text.

Typically, when it comes to print or static (onscreen) text, fonts with serifs, such as Times New Roman, are more readable than sans serif fonts, and words are more recognizable, since most books and magazines use fonts with serifs. The Media Access Group recommends using the Roman font, and Times New Roman is the most similar font installed on most computers.

However, some research indicates that sans serif fonts work better for closed captions than fonts with a serif (there’s more information on this at www.joeclark.org/access/captioning/bpoc/typography.html). According to Gallaudet officials, in their experience sans serif fonts are more readable. The Captioned Media Program appears to share this view, as it chose Helvetica Medium, a sans serif font, as its standard. All in all then, sans serif fonts are probably the best choice.

As discussed in Chapter 5, text with mixed capitals and lowercase lettering is easier to read than all uppercase text, and therefore the recommended practice for streaming media and DVDs. If you think that recommendation differs from most television captions, you’re correct, and here’s why.

Most closed-caption decoders on TV sets can’t display the below-the-line segments of letters such as j, g, q, and y (also called descenders). Instead, they display the entire letter above the line, producing a distracting appearance that decreases legibility. That’s why television uses all caps. Streaming technologies and DVDs don’t have these limitations, so you’re free to use the more readable mixed-case lettering.

Font sizes vary by captioning program, making it impossible to recommend a specific font size. In general, larger fonts are obviously more readable, but if your font is too large, your caption will wrap to the next line, or extend outside the viewing area.

There are also stylistic elements to consider. For example, PBS programs tend to use very small but elegant captions that torture my 40-something eyes (for example, see www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/). Those shown on the Web site of the National Center for Accessible Media (part of the Media Access Group) are much larger and much more readable (see, for example, http://ncam.wgbh.org/richmedia/examples/92.html).

My recommendation is to prioritize readability over elegance. In deciding what font size to use, preview your options within your target player. MAGpie was a fantastic tool, but the appearance of the font size within its preview window didn’t always accurately represent what ultimately appeared in the player.

Here we’ll discuss where to place your captions within (or underneath) the screen, and how and when you announce your speaker. As you would suspect, placement of text, in certain situations, can provide strong clues as to who is speaking. For this reason, in Figure 11.1, the text is positioned on the right, underneath the interviewer, Ken Santucci.

This leads us to Rule Number One in caption placement; if there are two consistently placed speakers, place captions beneath their respective positions. Note that under television rules, both captions, irrespective of placement, would be left-justified. However, since many streaming formats can’t display left-justified text on the right side of the screen, you should right-justify text placed on the right, and left-justify text placed on the left.

If there’s only one speaker, place the caption in the center of the screen and center-justify the text. In addition, if the speaker is off-screen, include the name or identification of the speaker, place the caption in the screen center and center-justify the text.

You should also identify the speaker whenever the viewer has no clear visual clues as to their identity. For example, if the video starts up and an off-screen narrator begins to speak, you should identify the speaker as narrator. If your interview has a J-cut, where the audio from the second video starts playing while the first video remains onscreen (see Chapter 5), you should identify the speaker.

If there are multiple on-screen speakers in a fast-paced discussion, consider identifying the speaker in all captions. Alternatively, since most speakers talk for longer than one or two captions, consider identifying the speaker only when the speaker changes.

As speaker identification is not spoken information, typically it’s set off from the main captioning in some way. For example, in Figure 11.1, the speaker identification is positioned on its own line, in all caps, placed in brackets, and set off with a colon, which is the practice of the Media Access Group. The Captioned Media Program uses italics or brackets, with no colon, and also positions the title on its own line.

In contrast, PBS, in its closed-captioned streaming videos, uses all caps offset with a colon, on the same line as the first line in the caption, which looks like this:

KEN: Joining us here is Mr. Jan Ozer.

Gallaudet’s recommendation is prescient in this regard. “If the character cannot be identified by name, then a descriptor should be provided,” he states. “An acceptable format for explicit identification is the character’s name or descriptor in upper/lower case, surrounded by parentheses, above the caption and left-justified with the caption. Other formats are probably uncontroversial.” Basically, pick one approach, and apply it consistently.

Let’s break these rules down for easy scanning:

If there are two consistently positioned speakers—. Place captions on their respective sides of the screen, justifying to their respective sides.

If there is only one speaker—. Place captions in the center of the screen and center-justify them.

If the speaker is offscreen—. Place captions in the center of the screen and center-justify them. Some producers identify off-screen speakers with italics.

Clearly identify new speakers whenever speaker identification is not obvious to the viewer—. This can occur with off-screen narration, during J-cuts, or when there are many speakers on screen. Format your speaker identification to distinguish it from spoken text.

There’s one real-world caveat to these rules: not all players and/or closed-captioned tools can create or implement left-justified, right-justified, and centered captions. For example, because of alignment problems encountered when playing closed-captioned streams in Windows Media Player, the Media Access Group modified MAGpie to produce only left-placed captions. In addition, RealPlayer can only display left and center-aligned captions (though, of course, you could right-justify the text using space or tab commands). In fact, the only streaming player that properly implemented our speaker-placement strategy was QuickTime.

Positioning within a DVD stream was a little more straightforward, and should be feasible in most authoring programs. Still, before selecting a caption-positioning strategy, test to ensure that all development tools and/or players comply with the strategy.

As we’ve discussed already, closed captions must describe a broad range of audio events to enhance the viewer’s comprehension of the video. As with speaker identifications, these audio events need to be visually different from the spoken information.

The Media Access Group recommends showing sound-effect captions parenthetically, in lowercase italics (but don’t italicize the parentheses), typically presented as a standalone caption. In the context of our interview footage, which was shot during the hustle and bustle of a trade show, captions included the one shown in Figure 11.2, displayed as the video is fading in from black at the start. This lets the viewer know that we’re shooting in a crowd, and you should identify both the source of the noise and the noise itself.

You can use these same indicators to describe the intonations that flavor the speech. In the interview, Ken and I were swapping stories, and he recalled a joint presentation where the equipment setup went less than smoothly. I laughed, and commented, “What a mess that was!” This would be captioned as shown in Figure 11.3. It’s also appropriate to caption emotion (e.g., angry frown, deep in thought, daydreaming) even if there is no accompanying speech.

The styles shown in Figures 11.2 and 11.3 are from the Media Access Group. The Captioned Media Program recommends brackets instead of parenthesis, and places on-screen noises and intonations in normal case, and off-screen noises in italics.

It’s acceptable to use onomatopoeia, or text strings that sound like the noise being described, though Gallaudet University found that most consumers preferred both a text description and onomatopoeia.

These would appear as follows:

(dog growling) Grrrrrrr,

or

(putt drops into cup) Kerplunk!

In addition to noises and sound effects, consider identifying other information that’s apparent in the audio but not in the text description. This would include accents (e.g., French accent), audience reaction (laughing, loud boos) and the pace of speech (slow drawl).

Music often sets the mood of the video, so when background music is present, it should be indicated. Television sets use a special musical note character to identify music playing, or when someone is singing, but the character is not universally recognized by all streaming media players. If it’s not available to you, use the word music in italics surrounded by either parenthesis (Media Access Group) or brackets (Captioned Media Program).

If the music has no lyrics, be as descriptive as possible (soothing music, disco music) and identify the name and the composer if known. Caption the lyrics if they are being sung, starting and ending with the special music character.

The goal with captions is to present them with the actual spoken word, but some people talk faster than others can read. In these instances, it’s accepted practice to edit the text to achieve a certain reading speed.

In this regard, the Captioned Media Program guide presents some very interesting statistics about reading rates along with very clear guidelines. Specifically, the guide states that most elementary or secondary students can read at 120 words per minute (wpm), and adults up to 160 wpm. For Captioned Media Program videos, the guide requires that “no caption should remain onscreen less than 2 seconds or exceed 235 wpm.”

When editing the text, the Media Access Group advises that caption producers “try to maintain precisely the original meaning and flavor of the language as well as the personality of the speaker. Avoid editing only a single word from a sentence as this doesn’t really extend reading time. Similarly, avoid substituting one longer word for two shorter words (even write a shorter word for a longer word) or simply making a contraction from two words (e.g., contracting ‘should not’ to ‘shouldn’t’).”

Note that virtually all style guides recommend against modifying for correct English (substituting “isn’t” for “ain’t,” or “you all” for “y’all”). Finally, if you find yourself having to shorten major sections of speech to meet your desired wpm rate, page 14 of the Captioned Media Program style guide offers some great guidelines.

The first nine steps covered the main issues, but there are many additional standards to address. Two of the most common include:

Treatment of numbers—. Generally spell out one through ten, numerals for higher numbers except when they start a sentence (Media Access Group).

Acronyms—. Display as normal (IEEE rather then eye-triple e)

For others, such as fractions, dates, dollar amounts, and more, consult the Captioned Media Program style guide.

You have your style guide; now you’re ready to begin formatting your text. The first step is to convert the audio into a text file. You can tackle this problem in a number of ways.

First let’s deal with manual conversion. Here a transcriber listens to the audio and enters all speech and other audio information into a file in a word processor. Then the transcriber starts breaking the file into individual captions according to standards used by the closed-captioning program. For example, MAGpie has very specific requirements for text input.

Manual conversion can be very time-consuming. Some sources estimate that television programs and movies rich in nonspeech audio content such as sound effects, background music, and drama, can take up to 20 hours of conversion for each hour of audio. Most corporate or academic training materials should be much shorter, since most of the text is simply transcribed speech. If you have a script that was largely followed, this provides a good starting point.

A quick Google search under “closed captioning services” revealed a number of service bureaus with prices starting at the $6 per minute range, or less than $200 for a 30-minute production. While certainly not cheap, this is a fraction of most production costs, especially if you had to rent equipment, a soundstage, or pay actors or other related personnel.

If you go the service bureau route, when obtaining a quote, be sure to ask the following questions:

What digital and analog captioning formats does the bureau support (Windows Media, QuickTime, Real, Line 21, DVD)?

What level of accuracy will the service bureau guarantee?

What style of captions will the service bureau produce (roll-up, paint-on, pop-on)?

How will the service bureau segment the text (characters per line and lines per caption)?

Will charges include complete audio transcription (sound effects, intonations) or just speech?

Which style guide or other direction will the service bureau use to segment the text and caption information, such as dates, numbers, and the like?

Automatic speech recognition generally works best when tuned to the voice and speech pattern of one user. For this reason, plugging in the audio feed from a training video or lecture involving random individuals will almost always produce poor-quality results.

To avoid this problem, many universities (including Gallaudet’s Television and Media Production Service) have adopted “shadowing” or “voice writing” where a person trained on the software repeats every word spoken in the video into the voice recognition system. Typically, these individuals work in a quiet environment or use a mask to minimize outside interference. These systems are not 100 percent accurate, but they do provide a first draft that can accelerate the transcriber’s work.

Computer Prompting and Captioning Company (CPC), a prominent closed captioned vendor, sells several systems that include IBM ViaVoice speech recognition software (www.cpcweb.com/Captioning/cap_via_voice.htm). You can also read about Gallaudet’s experience with shadowing here:

Most current television programs include closed captioning, which you can capture and reformat for use in streaming content. Grabbing the closed-captioned text itself can be fairly inexpensive, as most All-In-Wonder products from ATI have offered this feature for years (www.ati.com/products/radeon8500/aiwradeon8500/faq.html). Of course, from there, you have to reformat the text as necessary for your ultimate use.

To streamline this process, in fall 2004, The Media Access Group’s research arm, NCAM (National Center for Accessible Media), announced CaptionKeeper, which captures broadcast captions (also called Line 21 captions) and converts them to Real or Windows Media captions ready for live streaming or archiving.

The fee to license CaptionKeeper is $1,000 for corporations and $500 for academic institutions. Third-party hardware is required to capture the Line 21 captions, which will probably add about $800 to the entire system price. Check NCAM’s Web site for more details (http://ncam.wgbh.org/). Note that while the Media Access Group promised to provide details about these products on its Web site, there was nothing posted at press time.

Once you have a transcription of your audio, your work has just begun. Typically, your transcription will list each speaker and their comments in paragraph style, and may or may not have background noises, speech inflections, or other additions necessary to provide complete comprehension of the event.

As a starting point, your transcription may look like this:

Ken: We're streaming today live with both the Real encoder and

the Microsoft Windows encoder, side by side.

Jan: Very politically correct.

Ken: That's another interesting thing. There's more and more of

the streaming codecs available, especially at this show. We just

talked with Apple about QuickTime, and there are several new

ones. We'll talk to those authors, tomorrow.

Now the task is to add the required sound effects and format the text as specified in your style sheet. You should also look at the requirements of your captioning software. For example, MAGpie assumes that a single carriage return separates two lines within a single caption, while a double carriage return means a new caption.

If I input the text as shown in the sample transcript, MAGpie would produce three two-line captions, but the first and third would contain far too many characters. To avoid this, and remove the names (I’ll show who’s speaking by positioning the captions), I would pre-format the file as follows:

We're streaming today live with both the Real encoder and the

Microsoft Windows encoder, side by side.

Very politically correct.

That's another interesting thing. (both laugh)

There's more and more of the streaming codecs available, especially

at this show.

We just talked with Apple about QuickTime, and there are several

new ones.

We'll talk to those authors, tomorrow.

I also added the “( both laugh )” caption to reflect that both Ken and I were laughing after the “politically correct” quip. As we’ll see, preformatting the file in this manner importing into MAGpie a snap. If you decide to try MAGpie, be sure to check out NCAM’s page on preformatting documents for MAGpie http://ncam.wgbh.org/richmedia/tutorials/transcriptpreformat.html.

If you decide to use another captioning program, check the manual for preformatting tips for that product. Bear in mind, most captioning programs won’t accept Word for Windows .DOC files, so save the file as a plain text file with a .TXT extension.

If you’re using a broadcast captioning system, you should first ask your vendor if the system can generate captions in your target format—either QuickTime, Windows Media, or Real.

You can find a relatively complete list of captioning tools at www.captions.org/softlinks.cfm. MAGpie, developed by NCAM, is one of the most popular tools, and downloaded for free at http://ncam.wgbh.org/webaccess/magpie/.

On the download page, you’ll see that installing MAGpie involves several elements, including the Java Virtual Machine, which actually runs the program. Print and follow these installation instructions carefully, otherwise the program won’t run—I know because I didn’t, and it didn’t. One uninstall and meticulous reinstall later, and everything was fine.

MAGpie works most efficiently when applying captions to the actual compressed file you’ll be distributing, so if you haven’t encoded your file, do so before starting. With this and your captions file properly formatted, you’re ready to start.

MAGpie’s interface has two windows, one to play the video and the other to format the captions and synchronize them to the video stream. Since all controls are on the synchronization screen, I’ll mostly show shots of that screen, though if you jump ahead to Figure 11.10, you can see the Player.

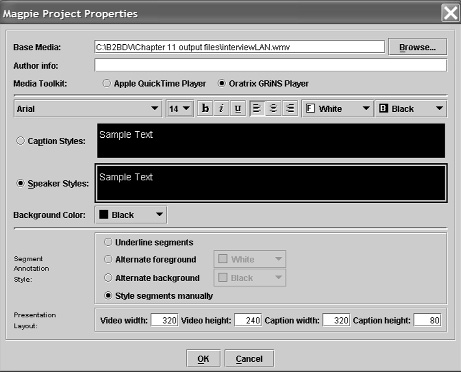

Open MAGpie, then click File > New Project in MAGpie’s file menu. MAGpie’s Open New Project screen appears (Figure 11.4). You can return to this screen at any time by clicking File > Properties.

Click the Browse button on the top right to load your media file. Then click the radio button if you’re captioning a QuickTime file, or the Oratrix GRiNS Player if you’re captioning a Windows Media or Real Video file. I’m working with a Windows Media file, so I’ll choose the GRiNS player.

As you can see, MAGpie allows you to set separate text options for the Caption and Speaker identification styles. Interestingly, though the Media Access Group’s default font is Roman, the default for this tool is Arial, with a white font against a black background. To save a trip back later, click each style and boost the font size to 18, which is what we’ll use in our final captions. Accept all other font defaults.

The Segment Annotation style is an advanced feature that applies Karaoke-style labeling to the captions. Leave this at the default setting (Style segments manually). If your video file is not 320×240, adjust the video parameters to those of your file, and adjust caption width and height accordingly. For example, if your file is 640×480, enter that into the video width and height fields, and make the caption width 640, and the caption height 480. Then, click OK.

Next, MAGpie displays the Create New Project Track screen (Figure 11.5) where you choose the type and name of the track. Audio descriptions are audio files containing narrated descriptions of the video for those with impaired vision, which is an entirely different operation, which I’ll cover later in this chapter. Make sure Captions are clicked, and either accept the track name (as I’ve done) or enter a new one, and click OK.

After you click this screen, the main MAGpie interface should appear with your video in a separate player. Now let’s insert the text file containing the captions. Right click on Track One, and choose Insert Captions from File (Figure 11.6).

MAGpie opens a standard File Open dialog, which you should use to select and load your file. Note that MAGpie loads your file starting on Row 2 of the captions. It’s not necessary, but if you’d like to delete Row 1 so your captions start on Row 1, just click the blank line, right click, and choose Delete Selected Row. When you’re done, MAGpie should look like it does in Figure 11.7.

As you can see, each caption row has a column for Start and End time. You don’t have to insert an End time; if that column is blank, MAGpie simply replaces the caption with the subsequent caption at its designated start time. The only reason to insert an End time is if you’d like the closed-captioned screen area to go blank.

Note the player controls on the top of the MAGpie menu. Use these to play the file in the player, which should be located in a separate window on the left. Alternatively, you can press F6 to start and stop the video.

To start synchronizing captions to audio, click Row 1 and make sure you’re at the absolute start of the video file. Click F9, and MAGpie will insert 0:00:00.00 to synchronize the video starting point with the first row.

MAGpie then automatically advances to the next caption row. Use the player controls to advance the video to where the next caption should appear and press F9 again. With a little practice, you should be able to play the video in real time, and press the F9 key to synchronize each row with the associated audio.

It forces you to concentrate, but I focus on the penultimate word in each caption. When I hear that word, I press F9, and read ahead and find the penultimate word of the next caption. Follow this procedure through to the end of the video file, making sure the final row is blank but contains a start time as shown in Figure 11.8. This helps ensure that the exported caption file will work with all formats.

Once the file is complete, you can use the player controls to test your file and make sure your synchronization is accurate. Any changes you can make directly into the timecode of each starting point; just touch it and enter the new start time. Or you can rewind the video until it’s in front of that caption, start playback, and then press F9 when appropriate.

Now it’s time to adjust the captions to the necessary justification (Figure 11.9). In this case, since I’m sitting on the left, I’ll keep all my comments on the left, right-justify Ken’s questions, and center-justify all other captions. If you didn’t spell-check your captions in your word processor, you can access MAGpie’s spell-check function by clicking Edit > Check Spelling in the main menu.

Figure 11.9. Enter any changes directly in the timecode, then left, center, and right-justify the captions as required.

Because Ken and I were sitting still on our respective sides of the screen, I didn’t insert any speaker names during the interview. Note that MAGpie reflects the Media Access Group’s policy of isolating the speaker name on the first row of a caption, as shown in Figure 11.1. If you adopt a different policy, you can place the speaker name within the first row of the caption, so long as it’s clearly distinguished from the spoken word.

Figure 11.10 contains the preview video from a 320×240 video produced in MAGpie. At 18 points, the text is reasonably readable and proportionate to the video. If you find your font size inappropriate, click File > Properties to return to the MAGpie Project Properties screen.

In terms of workflow, you can certainly enter captions directly into MAGpie if you choose, though I find it less efficient than creating a separate narration file in Word and then formatting that document for MAGpie. If you decide to enter the text directly into MAGpie, simply click the caption box to make the field active, and type the desired text. Use one carriage return to create another line within the caption, and a double carriage return to switch from caption to caption.

One final note. Though MAGpie is a free download, it proved very stable in my tests, performed on a Windows XP Professional computer (I did not test the Mac version). I encountered only one problem—I couldn’t change justifications when working with 320×240 files, though this worked perfectly with 640×480 files.

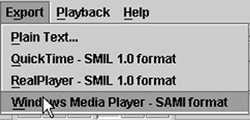

Exporting a file from MAGpie is simple; Click Export and choose the desired format (Figure 11.11). The only caveat is that MAGpie automatically overwrites any files in that directory without warning, so be careful to make sure there are no files in the path before exporting.

The Plain Text export feature is useful if you need a transcript of the event. Now that we have our exported captions properly formatted, it’s time to mate them with our compressed video files to produce captioned video playback.

There are efforts underway to standardize how QuickTime, Real, and Windows Media files synchronize with text (see www.w3.org/AudioVideo/timetext.html), but until these standards are set and adopted by each company, you’ll have to create a separate text file for each technology.

Using MAGpie’s export function, I created interview.smi, a file compatible with Microsoft’s Synchronized Accessible Media Interchange format, or SAMI (all SAMI files use the .SMI extension). This file contains the caption text and synchronization information just created in MAGpie. Now I’ll create a text metafile with an .ASX extension to link this file with interview.wmv, the Windows Media file containing the streaming audio and video file.

To play the video concurrently with the closed caption file, viewers will load the ASX file into Media Player. Similarly, to post your video and captions to a Web site, you would upload all three files to your site and have your Web page link to the ASX file. More on that in a moment.

Here’s what the ASX file contains in our simple example.

<ASX version="3.0"> <TITLE>Interview</TITLE> <ENTRY> <ABSTRACT>Discussion with Ken Santucci at NAB</ABSTRACT> <TITLE>Interview</TITLE> <AUTHOR>Jan Ozer</AUTHOR> <COPYRIGHT>2004</COPYRIGHT> <REF href="file://c:interview.wmv? SAMI=file://c:interview.smi" </ENTRY> </ASX>

Figure 11.12 shows Windows Media Player displaying both the video file and the closed captions. On the right is the Content screen accessed by clicking File > Properties > Content tab, where you can see the Abstract, Title, and Author information mapping over from the ASX file.

Windows Media Player won’t play captions if you’ve selected a “skin” rather than being configured in Full mode. To return to Full mode, click View > Full Mode. In addition, Media Player won’t play captions unless you enable the program to play captions. To do this, click Play > Captions and Subtitles > Captions. If your viewers can’t see your captions, chances are it’s one or both of these configuration issues causing the problem.

If you post the files to a Web site, you must upload the ASX, WMV, and SMI files to your server and update the ASX file to reflect the new locations (also called paths) of the content files. For an excellent white paper on ASX files, including paths to use for the various types of servers that support ASX files, check out www.microsoft.com/netshow/howto/asx.htm. To read up on the SAMI language, check out: http://msdn.microsoft.com/library/default.asp?url=/library/en-us/dnwmt/html/wmp7_sami.asp.

Finally, to learn how to embed Windows Media files directly into a Web site, see WebAIM’s excellent description at www.webaim.org/techniques/captions/windows/3?templatetype=3.

Where Microsoft uses ASX metafiles, RealVideo uses SMIL metafiles, which sound a lot happier (the word is actually pronounced “smile”) but do pretty much the same thing: point RealPlayer to the video and caption file (called a RealText file with an RT extension). MAGpie makes life easy by producing both the SMIL file and the RT file during the same export procedure. To play the captioned stream, run RealPlayer and load the SMIL file MAGpie just created. You can see the results in Figure 11.13.

Figure 11.13. Since MAGpie creates all necessary files, you’re ready to run RealPlayer and play the SMIL file.

Since MAGpie creates the SMIL file automatically, I won’t display it here. If you’re curious, you should be able to open the file in any text editor. For more information on SMIL files, see the SMIL Web site at www.w3.org/AudioVideo/. WebAIM also explains how to link RealPlayer content at www.webaim.org/techniques/captions/real/3?templatetype=3.

MAGpie also produces two output files when exporting for QuickTime: a SMIL file that will play the video and captions together in QuickTime Player, and a text file containing the captions and synchronization information formatted in QuickTime format.

As with RealVideo, the SMIL file I produced for this interview loaded and played normally in QuickTime Player—no muss, no fuss. However, some producers like to add the captions directly into the MOV file containing the QuickTime video, resulting in one MOV file rather than three. Accomplishing this is a three-step process and you’ll need QuickTime Professional to show you how ($29.99, direct from Apple).

Using QuickTime Pro, import the text file by clicking File > Import and selecting the text file. If the text imports properly, you should be able to play the text only file as shown in Figure 11.14.

The next step is to copy and add the MOV file containing the text track into the MOV file containing the actual movie. In the text MOV you just created, click Edit > Select All to select the entire track, then copy it by clicking Edit > Copy.

Load the MOV file containing the audio and video into another QuickTime Player and click Edit > Add. QuickTime Pro adds the text track to the video file, but places it on top of the video (Figure 11.15).

The third step is to position the captions at the bottom. Click Movie > Get Movie Properties. Select the Text Track and Size, and then click the Adjust button. The text track will appear on top of the video with red scaling and rotation points. Grab any black part of the text track and drag it down until it’s beneath the video track—it looks funky, but QuickTime will make room for it. Use your arrow keys to line up the text track precisely (Figure 11.16).

Figure 11.16. Drag the captions down and align (on the left). The finished, captioned movie is on the right.

When finished, Click Done in the Movie Properties screen (where the Adjust button was) and save the file, making sure that it’s self-contained. The finished captioned movie is shown on the right in Figure 11.16. Once again, you can find out more about embedding QuickTime files into a Web site at www.webaim.org/techniques/captions/quicktime/7.php.

If you’re producing streaming media with closed captions, chances are you’re also producing DVDs using the same content. Obviously, once you’ve produced and synchronized the captions, you’d like to use the same files in your DVD productions. Once again, if you own a broadcast captioning program, start by asking your vendor if you can export DVD-compatible subtitles from their systems.

As I was working with MAGpie, this option wasn’t open to me, so I started hunting around on the Web for a tool that could input closed captioned files, and output subtitle files compatible with the three authoring programs I primarily use, Adobe Encore 1.5, Apple’s DVD Studio Pro 3, and Ulead’s DVD Workshop 2.

My search wasn’t exhaustive, but I soon found a program called Subtitle Workshop from URUSoft (www.urusoft.net/products.php?cat=sw&lang=1). The program is a free download; all the company asks is that satisfied users send donations via PayPal.

You can create subtitles in Subtitle Workshop, though it lacks features such as the ability to right- and left-justify text, and MAGpie’s ability to synchronize captions to the video in real time. In terms of pure captioning usability, I preferred MAGpie. However, where MAGpie can only output in the three streaming video formats, Subtitle Workshop supports more than 50 DVD subtitle output formats and offers a wealth of import options.

I started by importing the SAMI file created by MAGpie, which formatted perfectly (Figure 11.17).

Using the output templates available in Subtitle Workshop, I then exported caption files (File > Save As) for DVD Workshop and Adobe Encore. DVD Workshop imported the file without problem, though I had to perform minor text cleanup, primarily in two-line captions, which DVD Workshop attempted to display in one line (you’ll notice it truncated “been digitized” to “beedigitized” in Figure 11.18). In addition, all captions were center-justified and placed in the middle of the screen.

Figure 11.18. The subtitles imported into DVD Workshop without difficulty but required some minor text cleanup.

When I attempted to import the captions into Adobe Encore, I received the error message shown in Figure 11.19. Apparently, Encore can only import Unicode files.

I loaded the file into Windows Notepad to see if I could spot any obvious errors, then checked Notepad’s export options to see if either option recommended by the Encore error message was available. If you click File > Save As, then the Encoding drop-down list box, you’ll see that UTF-8 is listed. I saved the file into UTF-8 format, and Encore loaded it without problem (Figure 11.20) and all captions displayed correctly, though they were all left-justified and placed on the left of the screen.

Interestingly, Encore’s workflow for caption creation is comparatively weak, so budget-minded producers adding subtitles to their DVDs should consider using the MAGpie-to-Subtitle Workshop workflow.

Importing into DVD Studio Pro required a bit more trial and error, but was ultimately successful. We first tried the DVD Studio Pro output preset, which wouldn’t import. This wasn’t surprising given that Apple had changed the subtitle architecture in Version 3. Fortunately, the Apple manual outlines several other formats that should import, including the Spruce Technologies STL format (DVD Studio Pro is partly based on a defunct program called Spruce DVD Maestro).

We tried that format and DVD Studio Pro happily accepted it, with a couple of minor problems—primarily replacing a <P> with a carriage return to produce a two-line caption. As with DVD Workshop, all captions were center-justified and placed in the bottom center of the screen.

While not totally problem-free, Subtitle Workshop certainly proved much more efficient than starting from scratch, and you have to like the price! Subtitle Workshop is not the only fish in the caption-converting sea, however. I also found a product called Lemony (www.jorgemorones.com/lemony/index.htm) that can import MAGpie files and output captions for DVD authoring in a variety of formats, and (it costs ∊135 from Europe).

The workbook for this chapter includes program-specific instructions for inserting and creating closed captions in supported DVD authoring programs. Go to www.doceo.com/dv101.html for a list of currently supported authoring programs.