PHOTOGRAMS

Daniel Ranalli

A photogram is conceptually quite simple, consisting of the forms recorded by the action of light on sensitized paper without the intervention of camera or lens. Such cameraless images are by no means a recent development in the history of photography, having appeared virtually as soon as an image could be retained by the action of light on silver salts. Ever since the experimentation of William Henry Fox-Talbot, who by 1839 had coined the term photogenic drawing, the photogram has provided the means for a wide range of photographic expression, from Man Ray’s Dadaist Rayograms, to the work of numerous contemporary artists as diverse as Barbara Morgan, Henry Holmes Smith, and Robert Heinecken.

I think of camerawork as the subtractive domain of photography: the eye, lens, film, and frame act as editorial devices critically eliminating and selecting. Cameraless work embodies the additive domain, the artist illuminating the blank paper with an idea through added increments of light. Thus, the photographer with a camera observes and selects the essential idea by using the rectangular film frame to subtract the extraneous material. The photogram maker starts with a blank sheet of light-sensitive paper and builds a picture by adding ideas, with light, to the empty white rectangle.

There was a time when I considered my objective as a photographer to be the classic standard print with full tonal scale and precise rendition of what I had perceived, selected, and previsualized. Some years ago, however, I experienced a series of events that radically altered my convictions about the importance of accidental and random effects, and the degree to which one might leave an opening for their occurrence and accept their results. Whereas I once felt it necessary to exercise complete control over my process, I now welcome the characteristically unpredictable results when working with the photogram.

Another appealing aspect of the photogram is the high degree of ambiguity possible in the final print. The photogram has all the surface appearances of a photograph, yet the viewer seeking to identify the subject may note that the shadows are reversed, that an object appears translucent, or that there appear to be many subjective meanings. It is this ambiguity, created by the viewer’s expectations of a photograph, that offers the artist some of the richest opportunities within the medium.

Finally, I am attracted to working with photograms by the basic purity of the process. While I am by no means opposed to the use of technical apparatus, I often find it gratifying to be engaged so directly with the basic elements of photography — light, paper, and photochemistry — without the encumbrances of cameras, lenses, and accessories, and to have the results manifest themselves so magically.

Light Sources

The procedure for making a photogram is quite simple. Objects are placed atop a sheet of unexposed photographic paper in the darkroom and a light source is directed briefly at the paper. The paper is then processed in the normal manner. The resultant image will appear darkest where it has received the greatest exposure to the light, and white or gray where an object has interceded to block some or all of the light from falling on the paper.

No special equipment is required, although a layout table of some type, with outline marks for the various paper sizes employed and a provision for mounting a lamp at different angles, can be a useful work surface.

Light sources are an important choice, one that should be given serious attention. Certainly one of the most productive exercises for the beginner is to make a series of photograms of the same object using a variety of different light sources so that their characteristics can be seen. I have, at one time or another, used each of the following light sources for exposing photograms, getting with each a somewhat different result:

1. Penlight

2. Flashlight

3. Spotlight bulb

4. Reflector bulb

5. Floodlight bulb

6. 15-watt incandescent bulb

7. Fluorescent tube

8. Slide projector

• Enlarger lamp

These are some of the possible light souices for making photogiams.

The Effects of Light Source Choice

The degree to which the light is focused, or the size of the light source, determines the relative sharpness of the shadow that is cast by objects placed on the paper. For example, the shadow cast by a fluorescent tube is much softer and more diffused than that cast by a reflector bulb. I find a flexible-arm drafting-table-type lamp very useful as a basic lamphouse for exposing photograms. The lower-wattage bulbs will prove helpful in avoiding total exposure of the paper and the consequent overall black tone. They permit a longer exposure and the opportunity for greater manipulation.

For results that have a rich gray scale, the surface of the photographic paper must receive differing amounts of light during exposure. Translucent objects will help in this regard, as will uneven patterns of illumination, which can be obtained by suitable light-source placement. I frequently employ multiple as well as moving light sources, which create more complex, if less controllable, results.

Exposed with a high-intensity desk lamp, almost a point source, this photogiam of a flower has clearly defined edges.

The same flower, printed with a normal incandescent bulb at the same distance, has a softer, more ethereal quality as a result of the broader light source.

Photogram Materials

Equipment necessary is little beyond the most basic darkroom furnishings. Two pieces of equipment prove particularly helpful. The first is a sheet of glass slightly larger than the largest paper to be exposed. Placing it on blocks so that it is raised over the paper to be exposed will permit you to slip photographic paper beneath the glass without disturbing the placement of objects on its surface. You can then lower the glass onto the paper for the exposure.

The second is a red or dark amber gel large enough to fit over the cone of the lamphouse. Black-and-white photographic paper is not sensitive to light from this end of the spectrum, and you can arrange objects directly on the photographic paper under illumination from the filtered light without danger of exposing the paper. If the filter is easily removable, you can make the exposure without having to disrupt either the arrangement of objects or the placement of the light source. If you have a red gel over your exposure light to preview your arrangements, the glass is necessary only if you desire repeated prints from the same objects.

A simple layout table setup consists of an exposing light source with red gel taped in place, a sheet of glass propped up over tape framing marks, and a timer.

Objects for Use

Objects to be used in making photograms are practically unlimited. Virtually anything that can be placed on the paper can be printed. Sharpness depends on the degree of contact between the paper surface and the object as well as the light source employed. Objects of glass, paper, acrylic, and other materials that transmit some light all offer interesting possibilities. I have worked with food, body parts, and clothing with intriguing results. Careful observation of the way light is reflected and refracted by different surfaces and textures is important, just as it is in camera photography.

Titled Cheerios, Napkin, and the Real Thing, this photogmm shows the use of recognizable objects to modulate the light.

As in the photogiam on page 32, the light that formed this image was modulated by pieces of cut cardboard.

Making the Photogram

The Process

Arrange a few objects on a sheet of glass slightly larger than the paper size you are using.

Tape an outline of the paper size, or a piece of plain paper that size, beneath the glass to define the boundaries of your working space.

Move the objects (I use pieces of cardboard) until you have an arrangement that looks promising. Bear in mind that it is necessary to reverse mentally the light and dark values on the paper you see in order to visualize accurately the final printed result. The middle tones, with properly controlled exposure, will print middle gray.

Raise the glass onto spacer blocks. They need only be high enough to allow you to slip the photographic paper under the glass.

Turn off the room light. Work under the safelight appropriate for your paper.

Place your photographic paper in the proper position under the glass.

Lower the glass from the blocks.

Expose the paper. Use an exposure time determined by the simple test on the facing page.

Process the photogram as you would a normal print.

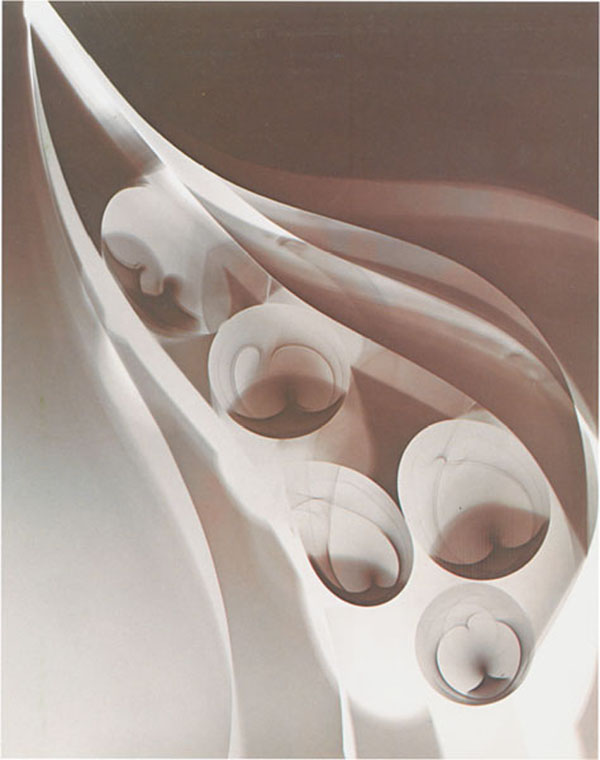

Photogram, 1976

An Exposure Test

A simple exposure test carried out before making your first print will give you a working exposure range for your light source-paper-developer combination. With your light set at the distance you will be using and plugged into your darkroom timer, make a test strip as you would for an enlargement from a negative. Lay the unexposed test strip under the glass, and cover a few centimeters of the paper at each 5 sec increment. Process the paper in your normal manner. The step when the paper first goes to full black and remains unchanged in the subsequent steps is a good starting point for exposure if you desire full blacks in the final photogram. With a 15-watt bulb 1 meter from the paper, try a range of exposures of from 10 to 30 sec.

It takes me a minimum of three attempts, varying exposure as well as burning and dodging, to achieve a satisfactory result. As many as twenty trials may be necessary to obtain a good photogram. This is no different from the labor involved in obtaining a fine print from a negative. There are few shortcuts to optimum printing, and I have no doubt that my earlier years of careful and arduous printing from negatives have been very helpful in allowing me to achieve the results I seek.

Shapes of cut cardboard placed on the glass cast shadows on the paper below. A photo-gram made without lowering the glass will have a less sharply focused image.

Abstraction vs. Representationalism

Most of my own work with the photogram has been abstract rather than representational. I feel I am using light to make marks on photographic paper, rather than printing the shadows and outlines of objects. My principal interest for some time has been in attempting to make objects rather than images. This is far more than a semantic distinction. One of the most significant differences between a painting and a photograph is that the former is characteristically perceived as a thing in itself, rather than, like the latter, as an image of something else.

Although many photographs abstract from their subject matter, sometimes obscuring identity completely through a close-up or an unfocused or manipulated effect, they usually remain images of things that exist. It has been said that the history of photography is the history of its subject matter, and its subject matter always has been some aspect of reality. Historians and critics of contemporary photography place the photogram out of the mainstream of photography. Indeed, the historian Beaumont Newhall felt it should be seen as a branch of abstract painting. In painting, especially since the late 1940s, the subject matter has often been the very paint itself. I have increasingly sought to make the subject matter of my photograms light itself, and to make objects that have no external reference. My photograms have a subject matter of light capable of entirely arbitrary arrangements. There is no remaining connection with the re-corded-reality aspect of the photograph, and they refer more to internal rather than to external associations.

Though my own work is abstract, the photogram offers possibilities for representational imagery as well. The work of Man Ray, especially his photograms that include recognizable objects, is an excellent example of imagery that fully exploits the unique properties of this medium. There is an undeniable ghostlike quality, a kind of dematerialization, that reveals itself in the photograms of many objects. This property should be considered when selecting material for your work.

You may wish to combine your photograms with some of the other approaches to image making offered in this book. Works in color and with nonsilver processes offer rich possibilities as well.

Moholy-Nagy in this 1922 photogmm evidences his use of found objects as light modulators. Moholy’s photograms, widely published, have influenced contemporary photographic composition as his writing has influenced today’s aesthetic criticism.

The photogram, or camera-less record of forms produced by light, which embodies the unique nature of the photographic process, is the real key to photography. It allows us to capture the patterned interplay of light on a sheet of paper. … The photogram opens up perspectives of a hitherto wholly unknown morphosis governed by optical laws peculiar to itself.

Laszlo Moholy-Nagy