Design Out Loud

Protoype to perfection.

In 2009, Intel introduced an innovative product called Intel Reader1, a mobile handheld device for people with reading-based disabilities, such as dyslexia or low vision, or for those who are blind. Simply put, Intel Reader coverts printed text into spoken word. I say innovative not because its component parts were particularly new, but because of how the Reader integrated three existing technologies—the digital camera, optical character recognition software, and a text-to-speech synthesizer—into a groundbreaking advance. Intel Reader provides someone with reading difficulty the ability to hear the contents of a textbook, a phone bill, or a menu. Snap a picture of any of these things and, voilà, Intel Reader tells you what they say.

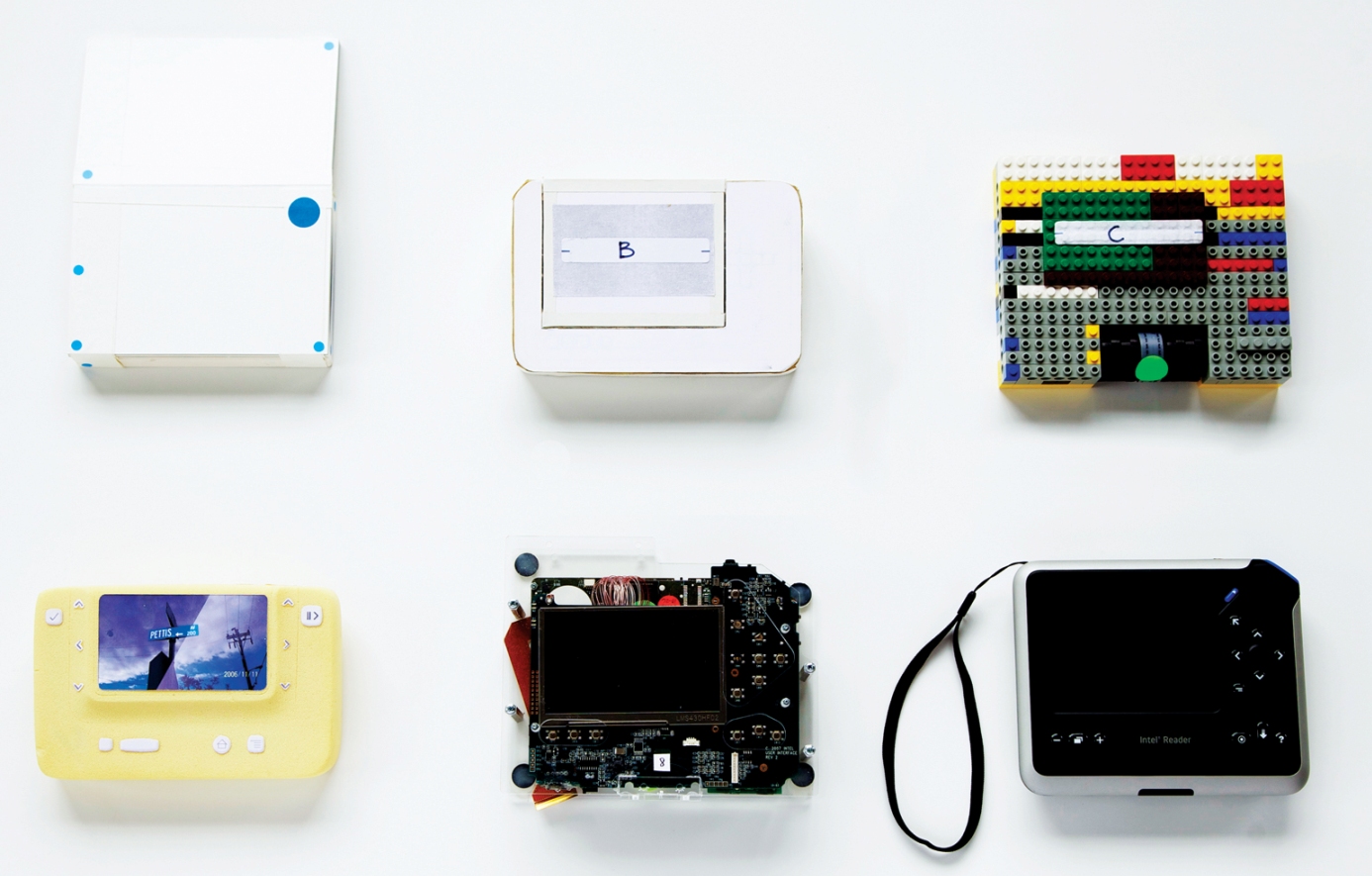

My colleagues and I at LUNAR were part of the design team for Intel Reader, and a good part of what we did was to prototype. In fact, we prototyped like crazy. While prototyping is an integral part of any design effort, because there was no other product like this one on the market we relied on prototyping to quickly explore a wide range of design alternatives at every stage of development.

A prototype is the tangible embodiment of a future product that helps us get a glimpse of what it will be. Prototypes are the lifeblood of a rich design process, because they stimulate the senses and make concepts real so we can feel or evaluate the future, whether through our senses and our emotions or through our rational sides, as we invent a new technology. Remember that the design process is neither linear nor predictable. More often than not design is a zigzagging journey of exploration in which the designer must set a course and then take a few detours on the road before reaching the final destination. To a large degree, prototyping is the strongest navigational tool on this journey.

That's why prototyping early in a process is crucial for saving time and resources later in development. There's a saying that floats around the Institute of Design at Stanford (commonly called the d.school). “Fail early to succeed sooner.” Had we not prototyped the early designs for the Intel Reader in physical forms, we might have missed the fundamental flaw in the design for days (if not for weeks or months), at which point the cost and delay of changing a design might have put the entire project at risk.

We started quickly and somewhat crudely by creating form factors that approximated digital cameras. After all, the Reader would be first and foremost a camera to capture pages of text. We put together a number of mockups that represented some design ideas, which all looked like large versions of a digital camera: a thin rectangle with a lens on one side and a viewfinder screen on the opposite side. These admittedly rough prototypes were presented to target users in early one-on-one research sessions. What we learned proved to be profound, because we saw right away how people would use the Intel Reader.

With their elbows on the table, the target users supported the camera so that they could take a picture of printed materials resting on the table surface. Two problems were immediately apparent: The users had to cock their wrists awkwardly to angle the camera lens toward the table; and those who could use the viewfinder screen couldn't see the screen because it was pointed at the ceiling! Back at the drawing board, we moved the camera to the bottom of the device, thereby fixing both problems.

This is the power of a prototype. It gets the design out of the heads of individual designers and out where other people can touch it and where designers can see how other people perceive, use, control, enjoy, or struggle with a design. The aim is to let ideas mutate in many directions at once so that the strongest mutations survive. LUNAR designer Ken Wood calls this a process of directed evolution. Designers produce a variety of concepts with different traits that are evaluated by the product team. The team will kill concepts that are not fit enough to be carried forward, and the survivors pass on their traits to future designs. Then the process is repeated. The eventual outcome is a product that is strong enough to survive in the real world. Like biological evolution, the offspring of prototypes benefit from previous generations of adaptation. And the more generations there are, the stronger the offspring will be.

As a manager, you might not even know that prototyping takes place, because it is mostly done in the design studio, while you are likely see only the final version of the product. You're probably more familiar with PowerPoint, which one could argue is a prototyping tool. As you know from sitting in untold numbers of meetings, PowerPoint is the primary modeling tool to represent marketing requirements, product specifications, competitive analyses, sales projections, and just about anything else a company needs. PowerPoint decks are useful abstractions for explaining the mechanics of a new product or service and for comparing the attributes of the product or service to other company offerings.

A handful of the dozens of prototypes that we used in the development of the Intel Reader. Materials range from paper to Fome-Cor to surfboard foam to three-dimensional printing to Legos—whatever got the job done quickly. Image: LUNAR

But PowerPoint is rarely used effectively as a prototype. Why? Because PowerPoint lacks a real human and emotional connection to the product or service. PowerPoint can describe product features, list channel retailers, and lay out statistics about the demographic makeup of customers, but it can't achieve anything near to what even a simple prototype can, which is to provide a team with a shared vision of the future product or service. Spreadsheets do have their place in corporate decision making, but when talking about future products and services, PowerPoint decks can reflect only a shadow of what the designers are experimenting with. In design circles, we like to say that a picture is worth a thousand words, but a working prototype is worth a million.

Apple uses prototyping more than any other organization that I've ever encountered in my many years as a design professional. Steve Jobs was famous for refusing PowerPoint presentations, because he wanted to see and touch the prototype. He wanted to hold in his hands exactly what his designers were working on, and he liked showing off prototypes to visitors. Jobs made decisions based on touching and playing with the prototype, not by evaluating data and decks and the financial analyses of a PowerPoint presentation.

Walter Isaacson writes in his book that when the first iPad was in development, Jobs and Ive worried over every tiny detail, including what the right screen size should be. “They had twenty models made—all rounded rectangles, of course—in slightly varying sizes and aspect ratios. Ive laid them out on a table in the design studio, and in the afternoon they would lift the velvet cloth hiding them and play with them.”2 Ive is quoted as saying that this painstaking process of prototyping was how they “nailed” the right screen size.

LET'S GET PHYSICAL

Long before I met my wife, I was lamenting to a good friend how hard it was to find people I was interested in dating. “John, you can't steer a parked car,” he told me. By that he meant that sitting around and whining that I wasn't meeting anyone I wanted to ask out was tantamount to sitting in a car at the curb without the engine started while expecting to get to any destination. Even going on a date, any date, would create forward momentum that would begin my journey and show me things about people and myself that would help me find my way to new relationships.

I'm not suggesting that dating and marriage can be compared to prototyping a new cell phone, laptop, or toothbrush. But the personal analogy can be applied to the complex and messy process of prototyping and product development. You just have to get off your butt and start doing something. For a designer, that means prototyping.

To explain how prototyping works and which tools and methods you need to know about, let's look at Stanford's design program, where building prototypes is central to design education, because the very act of making things influences how you think about your design. Students at the school are told that theories are welcome as long as the theories are put into a prototype and run through a process shorthanded as “express-test-cycle,” or ETC. This was the process we used in the preceding story about the Intel Reader. We expressed our designs quickly as prototypes and then tested them in the hands of users to observe what happened. And we cycled—that is, we repeated the process.

There is almost no limit to the forms of a prototype. An important mandate is that prototypes are made in the roughest, fastest form possible while still answering the important questions at hand. I have seen some wildly simple and effective prototypes in the past couple of years. And I admit that it's often a lot of fun to feel like a kid playing in the sandbox again. For example, one of our designers, Junggi Sung, manipulated a few pieces of paper to show our client, SanDisk, how a magical new flash drive might hide and reveal a USB connector (the product was approved on the spot). For a medical client, we deployed Lego models to explore, communicate, and compare different ways that small packets of medicine can be moved through a delivery device. One time, we taped a phone handset to an iPad to start a conversation about the future of tablets and smartphones. We sometimes use videos (rather than models) to illustrate stories about a potential product, as well as three-dimensional printing, which, as the name suggests, is an automatic machine that can create physical objects from computer-aided design (CAD) files through a variety of methods. The machine in our office slices the CAD model up into paper-thin layers and then builds each layer by deposited melted plastic in the shape of that layer. All of these new technologies allow us to prototype even faster and cheaper and more expressively, and that in turn makes it easier for us to imagine the product and explain it to the client.

Prototypes should be made in the quickest and easiest way possible to make ideas tangible and shareable. This iPad and telephone mash-up provoked a business phone maker to think differently about its opportunities better than an abstract conversation could. Image: LUNAR

PROTOTYPE AND THE OBJECT

A good way to understand prototyping in the real world is to tell you a story about how we used prototyping to help create a revolutionary joystick for computer games.

In 2004, we were approached by a company called Novint, a spin-off of Sandia Labs. Novint wanted to use newly developed haptic technology (i.e., the science of computer-aided touch sensitivity) to create a three-dimensional joystick that would provide gamers a better feel for the action. Expensive haptic systems were already in use by researchers and doctors, who use it to perform minimally invasive surgery with robotic assistance. The leading haptic technology came from a company called Force Dimension, which sold these systems for as much as $20,000. Novint's goal was to come out with a device it could sell for less than $200, and the company asked LUNAR to come up with a great commercial design close to this price point.

Our first prototypes gave Novint and its investors a first peek at what was an exciting, yet nascent, concept. We started with sexy prototypes (we call them appearance models) that captured a vision for what the product might become down the road. By sexy, I mean models in translucent white plastic and stainless steel that took their cues from the special effects found in science fiction movies that gamers enjoy. This created a target for what the final product could be and also helped the company build investor enthusiasm around the product idea.

With the Force Dimension technology and our first prototypes in hand, Novint could create a narrative about where it was headed with this product. It was a story that now had some tangible components and emotional appeal, thanks to the physical models prototyped by LUNAR designers. That was a promising start. The next hurdle was whether we could make a viable product for Novint's gamer market at a price about 100 times less than what the current haptic technology cost.

Prototypes that were made during the development of the Novint Falcon. Image: LUNAR

To find out, we first confirmed with Asian suppliers that they could provide component parts for a cost within striking distance of the target price. Then we did something nondesigners might consider strange: We tried to make the next prototype a failure. Rather than starting with a design that was dependent on $20,000 technology and trying to whittle that down to the price Novint wanted, we started at the low end and made a prototype in the cheapest way possible. Our “failure” joystick had the cheapest possible components (motors, bearings, and sensors) that we could find or design ourselves. To our complete surprise, this bargain-basement prototype joystick worked remarkably well.

By pushing ourselves to the limit with the cheap parts, we had the chance to back up, or zoom out, and see which components and parts needed further prototyping and adapting. By using the makeshift parts in our prototype, we had learned how to remove a big chunk of the cost. Okay, the cheapo joystick didn't move as smoothly as the high-end product, but we did have a working prototype on the very first go. The real trick was to devise a joystick that fools the hands into believing the gamer is actually touching the action seen on the screen. If at any moment the joystick jitters, wiggles, or responds in a way that is not synchronized with the action on the screen, the gamer's brain will notice, because the human sense of touch is just too sensitive.

Our next design phase involved testing. Walt Aviles, Novint's chief technology officer, who had worked on haptic systems at Sandia, became the human guinea pig for the project, because he could precisely judge the performance. He had a master vintner's “nose,” or let's say “hand” in this case. His input fed into refined designs from our team and led to a final product that came in on target, price-wise. That eventually became an award-wining product called the Novint Falcon, which has been keeping gamers happy ever since.

Prototyping was essential to creating a more comfortable toothbrush that would work for the five styles of grip that people use. Image: LUNAR

Prototyping anchored and guided this product through development. But prototyping isn't limited to a computer, a cell phone, or a joystick. As a manager, you shouldn't dismiss out of hand the concept of prototyping because you think the product isn't worth it or that a low-priced commodity can't benefit from having creative design minds take a whack at making it better. The Oral-B toothbrush we designed not only changed the look of the toothbrush, but also burnished the company's image and brand with a healthy patina of charisma, and also boosted the bottom line. Prototyping helped us to develop the form of the toothbrush that customers would grab off the shelves and killed of those that didn't.

A word of caution for organizations adopting a more design-centered approach to product development. At Apple, the senior team understands prototyping. Novint's leadership did, too. But for organizations new to design, it takes skill to look at prototypes and make a decision based on them. I have seen engineering managers try to kill projects because the prototype was not based on reality. Rather than seeing the potential in a prototype, some corporate naysayers see only its faults and judge it as if it were a finished product. This kind of behavior drives designers to hide their work until it's complete enough to be seen by other managers. Another approach I recommend is to make sure that prototypes don't overshoot their intended use. Early prototypes shouldn't look like finished products, because then people will judge them that way. Make them quick and rough, good enough to demonstrate or test the question at hand.

PROTOTYPE AND THE WORKSPACE

At most companies, prototyping takes place in the design studio, because this environment is usually the design and creative hub of the organization. That's the Apple way, too, although exactly what happens inside the Apple design studio remains murky. Given the company's cult of secrecy, access to the studio and information about new products and services are strictly controlled. This is done for obvious reasons, to prevent industrial espionage and, I suspect, as part of the effort to create excitement, buzz, and anticipation about what Apple is up to and what's coming next.

Still, information about the Apple studio sometimes leaks out. I spoke to a person who worked at Apple for almost four years, and her first reaction to a question about the studio was to jokingly compare gaining access to the studio to “the beginning of Get Smart,” the 1960s television show that spoofed the spy genre and featured a secret headquarters with a vaultlike entrance. Isaacson confirms that impression in his book, writing that the studio is “shielded by tinted windows and a heavy clad, locked door.” You might as well try to stroll into the White House. Inside the locked door is a glass-booth reception desk where two assistants stand guard. “Even high-level Apple employees are not allowed in without special permission,”3 said Isaacson, who did breach the barrier on one occasion.

A person who worked at Apple told me that the mood inside the studio is as one would expect: “peaceful and Zen-like.” Product prototypes are strewn across desks, and there are computer-aided workstations, milling machines, and a robot-controlled spray-painting chamber. “There was a sense of joy to be in there and to be working on these things,” this person added. In a typically Apple way, however, prototyping doesn't stop at the locked and bolted door. It's a concept that permeates every department at the company. “Protoyping was a way to work through things to try to get to the most compelling truth,” the former Apple employee, who worked in the marketing department, recalls. “You have instincts, but you can't always know that right away. It is a process of elimination. [Prototyping] advances the conversation and crystallizes the idea and you come out with a well-thought-through result.”

Adam Lashinsky reinforces this by pointing out that every aspect of a product is prototyped at Apple. He relates the amusing story of an unfortunate packaging designer whose job it was to find the best tab “to show the consumer where to pull back the invisible, full-bleed sticker adhered to the top of the clear iPod box.”4 The packaging designer was holed up in a tiny lab with hundreds of prototypes as his quest continued.

Not all design studios have Apple's mystical aura. Nor are they always walled-off spaces where designers huddle together, shrouded in secrecy. Designers do often spend days and nights squirreled away at a desk, seemingly oblivious to their surroundings. But design must also be part of a larger organization. Products don't exist in isolation, and neither should the design studio, because design ideas spread virally. As we think about a more collaborative future of work, progressive companies are beginning to look and behave more like design studios. Unlike PowerPoint files, prototypes require space. They tend to be messy. Organizations that want to harness more creativity are coming around to the idea that they need to have a space for creative chaos, which we call designing out loud.

This has long been the case at Method Products in San Francisco, where the main workspace is a large open area that Joshua Handy, the company's design director, describes as “a noisy colorful space of products and design and concepts that are out there for everyone to see.” Recalling the story about the concentrated laundry detergent the company had developed, Handy says that bags of the detergent and prototypes were lying around the office for years—a constant reminder of an unfinished project and work to be done. Method researchers had been experimenting with pellets as a way to deliver the product, but they couldn't get them to work for a variety of technical reasons. When a colleague of Handy's walked over to his desk to discuss a new pump-bottle idea, the problem and the solution came together in an environment that was conducive to collaboration.

Unlike at Method Products, too many corporate environments resemble sterile cubicle farms with limited collaboration spaces, even in the design studio. Over the past decade, design and architecture firms and design theorists have analyzed the office and how design correlates to productivity, staff retention, and overall happiness. Scott Doorely and Scott Witthoft, codirectors of the environments collaborative at the Stanford d.school, wrote a book called Make Space to share their knowledge about designing workspaces that encourage creativity. In a 2012 interview with Harvard Business Review's IdeaCast, they told the host, “We like to have spaces that allow you to materialize your ideas in the lowest, quickest way possible, and that allows you to throw them away when it's time to throw them away.” Doorely and Witthoft reckon that space plays a crucial role in how creativity is ignited in individuals and in teams. The very design of a space, the authors argue, can answer questions about where ideas come from and how team members participate in creative development.

Of course, the authors did some prototyping. They discovered that a number of different types of workspaces could help promote idea generation and concept evaluation, as well as prototyping. In 2011, we embarked on a similar experiment with the future of creative work when LUNAR moved into a new facility, a 100-year-old factory building in the Potrero Hill neighborhood of San Francisco.

In designing the space, we intentionally created a number of different workspaces. Square footage was stolen from personal workstations (by pushing desks closer together) to free up some experimental collaboration spaces. Adjacent to everyone's desks are a number of nooks, or small conference rooms, that encourage ad hoc meetings. I like to say that no one has an office but everyone can have one when they need one. Prototyping takes place in a flexible, collaboration laboratory—or co-lab for short—area that is home to the sketches and support material for all current projects. With three variations of space, design teams engage in different ways—from focused individual work to a “designing out loud” project space where prototypes can live adjacent to one another and where creativity flows.

CROWDSOURCED PROTOTYPING

Prototyping doesn't need to take place exclusively in a design studio with designers in charge of the process. It can also flourish in the marketplace by tapping the power of crowds and the people who actually buy and use the product.

Crowdsourced prototyping is most likely to be seen with software development. All of Google's many applications—from Gmail to Google Docs to Google Calendar—launched in beta form, allowing Google to test-drive these products with millions of users. Google's approach to product evolution is to get an application out there and let the world test it “behind the scenes,” although millions of people are doing the testing. Updates to the software happen invisibly to the user. One day the software just gets better, as if by magic. I say “as if,” because nobody has to download or install an update.

This is relatively easy for Google to do because of its vast user audience (it logs an estimated 2 billion searches per day). Google can easily select, say, 100,000 users and give them a different version of the software to try out, maybe without even telling them that they are the test rabbits. Google tweaks the width of borders, the size of text, or the color of links as much as it likes to find the most perfect size, color, and proportion. And, of course, this is all tied to its monetization model (what drives you to click more times on the links).

The drawback to prototyping in the real world is that it rarely leads to insanely great products. As a designer, I like and use many Google products. But with the exception of Google Maps—especially its implementation on the iPhone, and the topographical feature that stirs some nostalgic feelings about classical maps—I don't find much inspiration in any of them. Larry Tesler, who is regarded as the father of the graphical user interface for the Macintosh, noted that when companies like Google crowdsource prototyping, it's like tweaking a molehill and hoping it becomes a mountain. But many of these will never become mountains.

In fact, Google killed two products in 2012—Google Buzz and Google Wave—that had been launched with great fanfare just a couple of years ago. It wasn't that surprising. From what I can see, Google asks a lot of questions and does continuous testing on features and functions, but it's not clear who decides exactly what to prototype. It seems like many of Google's products are launched half-baked and then merely modified, or dropped, with a shrug of the shoulders.

In the end, I think Apple's model will prove much stronger. Apple products evolve through rigorous design and prototyping to reach perfection (or pretty near perfection) before they are launched. After that, Apple closely watches how people use them while work continues on the next generation of that product. The crowd is sort of involved, but they are not helping Apple decide between good and a little better. They are informing decisions about tweaking something that is already insanely great.

NEAR-LIFE EXPERIENCES

Prototypes needn't be physical models that you can hold in your hand, or objects that represent a stage in the development and evolution of a future concept or product. Prototypes can be experiences or stories. We all love to tell stories—to ourselves, to our friends, and, of course, to children. Stories help us understand the world and all its complexities and mysteries.

Animated films tell amazing stories, whether hand drawn by the masters in the early days of Disney or by today's digital artists using advanced computer tools at Pixar, the digital-animation company that was owned by Steve Jobs before he sold it to Disney. Yet even with animation technology, you still need stories to animate, and these can be prototyped, too.

Pixar's Academy Award–winning animator John Lasseter, who helped create Toy Story and A Bug's Life, uses prototyping in every scene in every movie. In his book The Second Coming of Steve Jobs, author Alan Deutschman relates that Lasseter would first sketch out storyboards and then film them, before taking the reel to Jeffrey Katzenberg at Disney. Lasseter would then play the reel “filling in the voices for all of the characters and acting out their movements.”5 Lasseter's talent wasn't just drawing and animating well. He could make “the drawings come alive with vivid characterization,” Deutschman writes. Lasseter was developing the plot, characters, and narrative as an experiential or emotional prototype.

As designers, we work with clients to help them get excited about how great their product or service could be. But once in a while, we like to have some fun and tell a story that scares the crap out of them. It's all for their own good, of course.

When Hewlett-Packard shifted in 1999 from being an enterprise and business computing company to being a consumer-oriented computing and printing company, the inkjet printer division asked us to help create a consumer design capability. HP didn't want us to design a new printer. It wanted to know how to reorganize the company and hire the right staff so it would be in a position to create products that would be meaningful to customers.

Part of our solution to this mandate was to create a series of “near-life experiences” as away of prompting gut feelings about how it would feel when new competitors moved into HP's space. We wanted to point out how important it would be for the organization to quickly adopt the consumer design strategy that we were helping it to create. A little playacting would work like shock therapy. Call it design shock therapy.

Fifty HP managers in the company's inkjet division were brought together for a presentation to introduce them to the new consumer design division. During our presentation we flashed on the screen a page purporting to be from Sony Style, a magazine that featured a very hip display of Sony products aimed at a younger audience attuned to coolness and charisma. The page in question showed a modern entertainment unit filled with various Sony stereo equipment, including a great-looking Sony inkjet printer in high-polish black right there in the stack. Jeff Smith, LUNAR's founder and the guy giving the presentation said nonchalantly, “… and here is what Sony is doing to leverage its brand and move into your market.” There were soft gasps in the room. These marketers and engineers were caught totally off guard by the “revelation” that our designers had concocted and Photoshopped it into the Sony Style page. The HP managers quickly got the point: They needed to act swiftly and decisively to shift their thinking from enterprise customers to consumer customers. Our story embedded a message in a visceral medium that was as targeted and direct as any animated scene presentation John Lasseter would make.

We also use stories to explain, inform, and communicate. In 2011, LUNAR's European office in Munich worked with the German environmental organization Green City e.V. and the University of Wuppertal to design a new system to encourage urbanites to use alternatives means of transportation. The team zoomed away from the problem and identified the issues hindering greater use of bicycles, electrobikes, and trains as “green” alternatives to driving cars in a city with a growing car congestion problem. Research showed, for example, that 80 percent of city residents owned bikes but used them only 10 percent of the time. A new mobility system called mo' (short for mobility) was designed to change user behavior and encourage eco-friendly transportation decisions. There was no better way to explain mo than through videos chronicling how ordinary citizens use the new system throughout their day.6

The beauty in this prototype is that it uses stories to communicate a complex experience that changes over time: in this case, different people using alternative transportation for a variety of reasons and situations. It's easy for people to project themselves into the story to imagine themselves climbing on an electrobike or calculating the “mo-miles” they have accumulated while using the system, which makes participants feel like they are part of a special community (mo was designed for Munich but can be applied in any urban area). Increasingly, designers and design firms are relying on storytelling or time-based experience prototypes to research and explain how a new system works and impacts real people. Whether a video, a foam model, or scraps of paper, all prototypes are essential tools that help designers through the process of visualizing and creating a future product or service.

SUMMARY

Prototyping is the lifeblood of a complex design process. It enables designers and managers to make product concepts real and imaginable before they are real. Prototyping involves building the quickest and dirtiest model to do the job—whether paper, cardboard, foam, three-dimensional printed models, videos, storytelling, or near-life experiences—to explain, inform and communicate what a product and service will be.

THE BUILDING BLOCKS

Design out loud

means an open and shared design and prototyping process in which ideas freely circulate among collaborators and are not locked away in isolation.

Prototype the object

is a way to visualize in a multitude of forms and variations what a product might be in order to work through flaws and costs and appearances until all critical parameters are addressed.

Crowdsourced prototyping

takes prototyping out of the design studio and into the marketplace to tap the power of the crowd by focusing on people who actually buy and use the product.

Near-life experiences

move prototyping from physical objects you can hold in your hands to storytelling and visualized experiences that help us understand how a product or service will work in real situations and impact the target audience.

DESIGN LIKE APPLE AGENDA

Before we examine how to use design to connect with the customer, let's review the lessons of this chapter about prototyping by asking questions about how products and services at your company evolve from an idea to a final version:

Notes

1 Although originally introduced by Intel® Corporation, the Intel® Reader is now offered by Intel-GE Care Innovations™, a joint venture dedicated to advancing technologies such as the Reader and its expanded product family Intel-GE Care Innovations™ Achieve.

2 Isaacson, Walter. Steve Jobs. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2011.

3 Ibid.

4 Lashinsky, Adam. Inside Apple. New York: Hachette Book Group, 2012.

5 Deutschman, Alan. The Second Coming of Steve Jobs. New York: Broadway Books, 2000.

6 Mobility for tomorrow. 2010, http://mo-bility.com/mo/home_.html.