Design Is for People

Connect with your customer.

For me, the allure of design started with cars. When I was 12, I drew cars all the time, fascinated by the look and details of each model. I had a coveted subscription to Road & Track magazine, the car magazine, which I devoured each time it landed in the mailbox. I knew the name of every production car and even most of the rare supercars from most of the century. I could recognize the illustrators in Road & Track before looking at their signatures. And, of course, I also imagined getting behind the wheel. I fell asleep at night imagining myself in any number of crazy adventures that involved driving very fast and guiding my sports car around hairpin turns.

In my doodles I designed sports cars, trucks, and SUVs. I was obsessed with their forms, especially the side view and body and wheels. What I liked most were the European and Japanese cars I saw cruising on the highway, because even at that young age I noticed the different details. American cars were sloppy, overgrown beasts. They had giant gaps between the tires and the wheel wells. The dashboards didn't integrate seamlessly with the door panels. But, oh, a foreign make like a Mercedes or a Mazda, here the design was tighter; the fenders hugged the tires, more like what I saw in racing cars. As an adult and a designer (and still a car freak), I know that it's easy to cut corners and overlook such details.

Lee Iacocca and his team at Chrysler had a shared understanding of the needs of suburban families that led to the development of the Dodge Caravan—a huge success because of how well it resonated with the target customers. Image: Courtesy of Chrysler Group LLC

Looking back on my childhood and obsession with cars, I realize that my infatuation was all about me. I was the center of attention, or in today's marketing jargon, the end user. I wasn't designing to meet the needs of other people. I remember seeing a Chrysler Dodge Caravan, the first minivan that was introduced during my car love period, and couldn't for the life of me make sense of this model's appeal. I hadn't yet developed a designer's keen sensitivity to discovering the needs and desires of other people and how to use those insights to create products customers can't live without. To me, the minivan was merely another ugly American car destined for the junkyard.

What I didn't understand was that the minivan was born out of a customer-aware designer insight, which began with a researched understanding of the way that American families were living and where the pain points existed in the current product offerings. This pointed the way to defining opportunities for future products. The minivan let soccer moms effortlessly deliver kids to practice games and birthday parties and to malls and amusement parks. It was easy to drive, easy to load—with plenty of seats for the kids and their friends and the dog. The big sliding door allowed parents to buckle up little Janie in the child seat and retrieve the cooler without wrenching their backs. The floor sat close to the ground, making it easy to step in, while the driver sits high with a commanding view of traffic. And the abundance of cup holders meant that everyone could be armed with their morning coffee or their afternoon snack in between school and dance class. The minivan defined a new category that is ubiquitous today because it answers so thoroughly the needs of families with preteen kids (marketers, in fact, now refer to a specific “minivan life stage” to describe this period in an American family).

Even if minivans aren't your thing, for whatever reason, we've all had those aha moments of discovery when a new product or service addresses a need we didn't know we had. It's as if researchers reached into our minds and poked around to find something that was missing. Then they came up with exactly the right thing to scratch an itch we hadn't even felt.

Some examples: TiVo eliminated complex VCR programming and Dropbox simplified file sharing and backup. Quicken brought order to our personal finances, and OXO made vegetable peeling more satisfying. Apple made sense of how we manage our own personal digital music. Observing the lives of customers to find these unmet needs leads companies to create products and services that create new value, whether it's an incremental improvement in an existing product or a big insight that carves out a new market category.

These innovations are not necessarily cutting-edge technology. That OXO vegetable peeler isn't reinventing the wheel or introducing the world's fastest silicon chip. The peeler simply has a great ergonomic handle and a heft and feel about it that seems just right. What OXO and other companies have perfected is a talent for listening, and that connects to a core principle of design: the notion that you're designing for someone else, as the designers at Chrysler did when they conjured the minivan. This is the Apple approach to design. Apple assumes the role of the customer in the design process and considers every aspect about the product, from the user interface to the in-store retail experience when the customer finally comes into direct contact with the product.

Apple, of course, applies that principle to technology, using design to add a distinctly human sensibility. It makes technology feel emotional, as if a friend rather than an infuriating automaton is in the room. In other words, the digital (technology) feels analog (human). With Apple products, technology does its business behind the scenes but is presented to us as facial expressions. When you swipe to the last page of apps on your iPhone, and then keep swiping, the path moves a little bit and then bounces back, in what Apple calls a “rubber band action,” to signal that you have reached the last page. Rubber band action is completely unnecessary from a programming perspective, but it makes the experience human and delightful. Apple understands that people are wired to treat complex systems as living beings. We recognize patterns in ATMs and on websites and in retail experiences, because that's just how we are, and these interactions become human ones. “Comcast is not very friendly,” we might say. But we're not talking about any individual at Comcast. We're talking about the synthesis of all our Comcast experiences.

That human sensibility applies to the first customer interaction with an Apple product. You take it out of the beautiful box, hit the on button, and start using it without lots of fumbling and decoding of badly written instructions. These products are ready to use even by people who might never have touched one before. They are programmed to smoothly lead customers to their first downloaded e-mail, song, or e-book—which will be the first of many easy and delightful experiences.

A HUMAN CENTERED ETHOS: EMPATHY

In researching this book, I spoke with a number of former Apple employees who helped me construct a firsthand view of the company at every stage of its history. The common thread I detected in all of their stories and comments was that everyone at Apple believes in the company's mission to change the world. That might sound like a pompous and oversized aspiration, but it is taken very seriously by the employees, who share a human-centered ethos, or empathy, which is the ability to understand the feelings of others.

It all comes down to details, like the volume buttons on the side of the iPhone. Dozens of prototypes were made just to tune the feel, size, sound, shape, icons, and orientation for those two buttons. Product design engineers know that even these seemingly minor details are part of the human-centered ethos and can make the product feel like a million bucks—or a piece of crap.

You might be wondering at this point how Apple manages to know its customers so well. How does it maintain such high customer satisfaction levels all the time? What kind of research goes into designing products that inevitably become high-margin profit makers, category killers, and industry game changers all rolled into one? To have that kind of empathy, one assumes that Apple employs thousands of people whose only job is to plumb the depths of customer consciousness so the company has precise information about what products and services will strike deep into the heart of desire.

However, according to executives from Steve Jobs on down, Apple doesn't operate like many other companies in that it doesn't ask the market what to make or undertake conventional forms of research. As discussed in Chapter 2, Jobs distrusted research. Instead of asking customers or the market about products, Apple works largely from intuition and a pervasive human-centered ethos. “We figure out what we want,” Jobs told CNNMoney in 2011, underscoring the “We design for ourselves”1 mantra. Instead of focusing on market research or feedback, Apple has established an internal process where design ideas are traded and filtered in the development process, according to one former Apple product design engineer I spoke with.

This concept isn't unique to Apple. Another Silicon Valley giant, Hewlett-Packard, utilized human-centered design decades before Apple did by encouraging its engineers to look over at their colleagues when imagining new products. This practice, dubbed “next bench,” was promoted by HP founders Bill Hewlett and Dave Packard and became widespread in the company, as veteran HP designer and LUNAR colleague Shiz Kobara told me in an interview. “Their customers were essentially people just like themselves—engineers at the forefront of technology,” Kobara explained. “If the guy at the next bench needed what you were inventing, there was a good chance there was a market for it.”

I suspect it's at least partially true that Apple employees are their own best customers. The extremely talented people working there are no doubt an unequaled source of inspiration about products and design refinements. They have amazing intuition about what makes a product—more precisely, an Apple product—click with a customer. Of course, with Jobs at the helm for so long and with his imperious personality, you could say Apple was in fact using “next bench” design for only one person on the next bench (or in the executive suite): That was Jobs, of course, who had discerning design taste and judgment.

The “next bench” concept doesn't always pay off, however. It can create huge problems for companies when the teams are not in tune with the market. Just look at what happened when General Motors and Ford jumped on the Chrysler minivan success bandwagon. Both automakers made the mistake of handing the design challenge to their truck engineers, partly because they wanted a vehicle on the truck line that would help meet federal fuel-efficiency standards.2 Truck engineers, of course, make trucks, and the resulting minivans they designed were therefore more like trucks—much heavier and harder to handle than the Chrysler models, which stayed true to the goal of being better family cars.

DESIGN RESEARCH

Despite repeated denials by Steve Jobs and others that Apple doesn't do any traditional research, there's no doubt in my mind that Apple does listen to its customers, and that can clearly be labeled as research. When Apple chief executive Tim Cook announced the new iPad in March 2012, he referred to the fact that the company had “talked to customers” about their favorite device for reading and writing e-mail. (It was the iPad. Are you surprised?) It's also clear that Apple pays close attention to what people say about its products via Internet web chatter and social media. While we don't usually consider these traditional research methods, it is a type of research, and whatever information Apple does record is digested and finds it way to subsequent product improvements and revisions.

That iPhone 4S in your pocket has largely the same physical user interface components and on-screen features as the first-generation iPhone. But the details have been enriched. Picture-taking speed has increased, because there's a button on the lock screen that starts up the camera, eliminating several steps in the process compared to previous models. Creating appointments is much faster, because Apple added some much-needed functionality to the calendar app. And, most interesting to me as a designer, the iOS 5 includes features that are seemingly “borrowed” from Google's Android phone—such as the customizable window shade interface that shows the day's weather, events, and stock ticker—even though Jobs had blasted Google for stealing the iPhone interface from Apple. All of these features had been talked about at great length in the press and online and certainly informed Apple's decision to include them in new software releases.

If your company doesn't follow the Apple top-down approach to design development, research can be a powerful path to creating a shared empathy for customers. I'm not talking about market research, which collects quantitative statistical data from a defined demographic focus group. I'm talking more specifically about design research.

Design research takes an anthropological view of the world. It means going into the field to observe and gather qualitative information about people. It means understanding the behaviors and motivations that will be the foundation of an informed design process. Imagine a coming together of design and the social sciences, in which the designer's inherent capacity to control elements of design (form, color, proportion, balance, and flow) converges with the methodologies and strategies social scientists use to uncover the unmet needs of customers.

When we worked on the Oral-B toothbrush project, we looked at videos of real people in their real bathrooms brushing their real teeth. By watching people in context, we had a spy-eye view of their private habits and were able to synthesize some general insights that became important imperatives for the design process. When speaking to clients about the need for design research, I always say that traditional market research alone would never have delivered the same depth of observational information. Who would have even known to ask a focus group whether it would be okay for the toothbrush bristles to touch the top of the sink?

Design research is helping Motorola (now known as Motorola Mobility) transform its culture. After hitting some speed bumps in its design and development process (remember the Frankenstein phone that I described earlier?), Motorola is now taking customer insights seriously and leveraging those insights in the development process. Integrating customer insights into the development and decision-making process “has shifted the culture from a purely engineering-driven environment to a consumer-focused business,” verified Joy Ganvik, senior director of global consumer and market insights at Motorola Mobility. I don't expect to see any more Frankenstein phones with the Motorola name on them anytime soon.

Once design researchers have gathered this information and their observations, they use left-brain analysis to sort out what they found. Similarities in behavior and attitudes are clumped together, and differences are identified. At this point in the process, designers often create a new framework for thinking about the problem. This happened at Method, the cleaning and personal-care products company discussed earlier, after someone observed detergent drips on the top of washing machines. The cleaning agent, Method researchers realized, was actually making the washing machine dirty. The company understood that there was an opportunity to fix this problem by creating a laundry detergent that would not only clean clothes but also keep the laundry room neat and tidy and free of detergent drips.

Here's another good example of design research in action. In 2006, a big Chinese sporting gear company called Li-Ning, which was founded by a former Olympic hero of the same name, needed help to compete with Western brands like Nike and Adidas that were encroaching on its turf. Li-Ning had parlayed his fame into a successful business by borrowing Western-style products and marketing. But younger customers were no longer inspired by Li-Ning's products or message, and the company's market share was eroding. Li-Ning called in Ziba, a Portland-based design firm, which launched an in-depth design research project to find out why.

“Li-Ning had great values from its founder, but they didn't know how to communicate that to the next generation of Chinese youth,” Paul Backett, industrial design director at Ziba, who was involved in the project, told me. Of course, the generation of Chinese youth that Li-Ning needs to understand and sell to in order to survive in an increasingly competitive environment are those young people who are more brand-aware than their parents and also have some of their parents' disposable income.

Ziba is located half a world away from China, but it had experience with on-the-ground design research. Two dozen researchers (including Chinese and American designers) were dispatched to 10 Chinese cities, where they conducted 130 interviews and took 7,000 photographs of Chinese youth. They observed Chinese kids at home and at school and playing sports. They followed them to stores where they bought sporting goods. Such information, Backett says, “is incredibly rich stuff. You end up with insights and results that aren't driven by numbers and demographics. You get to know the people you talk to and their patterns, because you are face-to-face with them. You see sociological patterns.”

Researchers discovered that Chinese youth play sports and think about sports differently than kids in America and Europe, where sports are “all about winning” and Nike's “we're number one” model, Backett points out. In China, sport is seen as the way to make friends, build relationships, and connect with their peers. Sport is much more about play and inclusion than competition and excluding those who can't play at the same level. Another insight: Chinese youth have a strong sense of national identity and are seeking an authentic Chinese sports company.

The researchers suggested that Li-Ning products should address sport as an element of play, because Chinese kids might, in one day, go biking and then play some basketball and then a little soccer. Stores should be redesigned to echo that theme, with elements such as graphics on raw concrete floors to mimic how sports are played in the streets. Fitting rooms shouldn't be hidden away at the back of the store, but brought to the middle so shoppers can interact more with their friends. “You have to immerse yourself in their world and their feelings and concerns,” Backett says about the research. “There are people behind those profiles and targets.”

Design research isn't only for stuff you can hold in your hand. It can also be applied to websites or software apps, which is what the company Intuit did for its amazingly easy-to-use tax preparation software TurboTax. According to a former Intuit employer, this software was tested on real taxpaying people like you and me, who were asked to sit in front of a computer at Intuit's facilities and input tax information as researchers watched. Software makers do this all the time, because by having someone unfamiliar with the program play with it they can unearth any problems that the designers, who are too close to the nuts and bolts, might have overlooked.

This works best if the results are an honest reflection of how the product is used rather than a check-the-box laundry list. Intuit, for example, has long used usability testing to make sure people can use its software. For its tax preparation software, Intuit began doing this testing a bit out of context: Research subjects were given generic receipts to use as the basis for entering data into TurboTax. Sometime in the mid-2000s, Intuit began asking people to bring in their own financial information, W-2 forms, and receipts. This time the researchers spotted some alarming oversights of their previous approach. They could clearly see exactly how the software was used and how much or how little the customers could decipher. One puzzled interviewee said during the process of entering her charitable donations, “I wrote a check to my church, but the computer is asking me whether I donated ‘cash' or ‘items.' Where do I say I wrote a check?” The Intuit designers realized immediately they had merely repeated the confusing questions provided by the IRS instead of explaining them in simple terms that ordinary people could understand. Getting the design research right is a design challenge all its own.

In a similar way, a company called Mint goes TurboTax one better. Mint's software, which I use, aggregates information from all of my banks and financial institutions into one place and then sends the information back to me in terms that a nonfinancial guy like myself can understand. It lets me know about my expenses compared to my budget, all in real time. What's more, Mint learns my spending patterns and alerts me when it senses that I'm over my budget or tapped out. (That's when a gentle e-mail arrives noting, “You've exceeded your clothing budget this month.”)

The software prompts you to think about your spending habits and savings goals, which are not often aligned, and does it in a way that's much more appealing than a spreadsheet. Only a design research team that was looking intensely at human behavior and motivations could have developed an application that feels so intuitive and resonant with my needs (which I'm assuming matches the needs of other people without a good head for figures). Intuit was so impressed with Mint that it bought the company in 2009 for $170 million and integrated its personal-finance application into its own product lineup.

DESIGN FOR SOMEONE, BUT NOT FOR EVERYONE

It's tempting to want your products to be accepted by everyone. Logic suggests that the broadest adoption of a product will lead to more sales and a bigger market share. But the problem for a development team is this: How do you design for everyone? How do you make decisions about the right features, especially when dealing with a complex software product that can be made to do almost anything?

A better way is to define the person you are designing for (the target customer) in a way that the entire team can understand. When a clear picture of this ultimate customer is created and acknowledged by everyone involved, it is easier to reach an alignment about design details, product features, and the overall context of use. You're not excluding other types of customers, of course, but instead you are focusing on a clearly delineated persona who is a composite of real people in your target market. You want the entire team on the same page, objectively, so that the marketing manager doesn't argue to keep a feature in a product for reasons of personal preference, but because a persona named Penelope wants it. The personas we create from what we learn in our design research work best when they make Penelope tangible by describing appropriate details of the underlying goals in her life that relate to the project—for example, a name, a demanding job, her behaviors, attitudes, and uses surrounding cell phones. The made-up personas live in the parallel universe of our office and allow us to give particularity and focus to whatever it is we are designing.

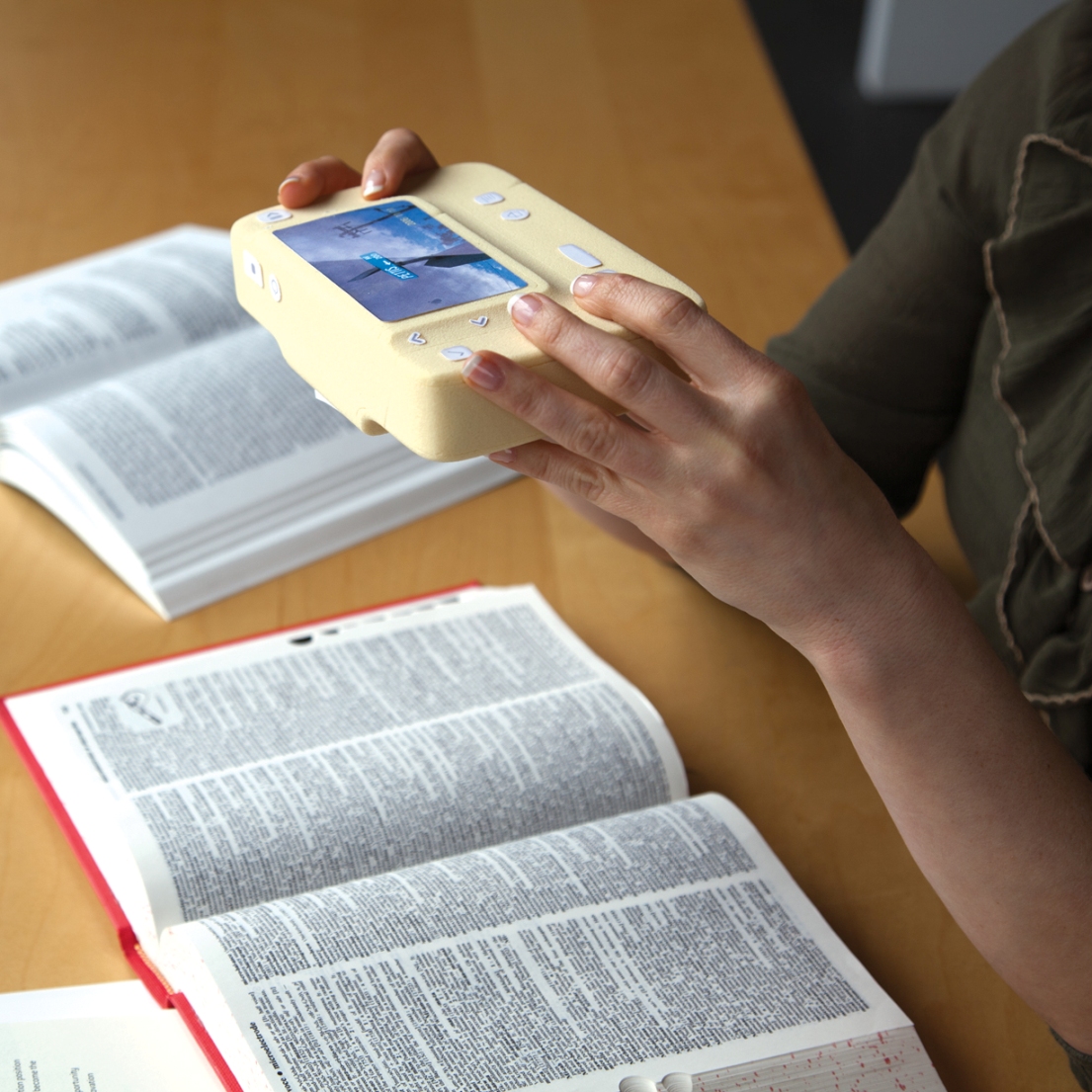

We did this type of design research when creating the Intel Reader discussed in Chapter 2. Personas were particularly needed because no one in the design firm fit the profile of a potential customer. A brilliant guy from Intel, Ben Foss, who was the project leader, was dyslexic, but we couldn't design the Reader only for him. Hearing from other people with similar vision issues was the only road we could follow to know and understand people who would be using the Reader every day for a variety of different tasks.

Throughout the development of the Intel Reader, we interviewed more than 30 people who were dyslexic or who suffered from low vision or were blind. We wanted to know about their lives and problems and how they coped by devising solutions for themselves. The interviews were expanded to include teenagers who had just been diagnosed with dyslexia and retirees who had recently lost their sight to macular degeneration. From this information, we shaped five personas that covered the range of disability, stage of life, occupation, and other social aspects. One of these was a dyslexic teen we named Ethan; another was James, a low-vision senior. Both Ethan and James, who were extreme cases, had needs that encompassed or exceeded everyone else in the group. At the outset, we wanted to refer to blind users as the most extreme example, but we quickly discovered that people who are blind from birth have learned to manage in the world without vision. The more demanding users are those seniors who have been dependent on their vision and then, for whatever reason, begin to lose it and must adapt to a darkening world.

Conducting research for the Intel Reader helped the entire team develop an understanding of the needs and motivations of potential customers, and it led to important insights during the development process. Image: LUNAR

Alongside these personas, we also identified scenarios in which each would be dependent on Foss's digital reader device. James, the senior, wanted to read his mail to find bills that needed to be paid and to navigate restaurant menus on his own. Ethan, the teenager, wanted digitized textbooks and class handouts to help get his homework done. At every turn, the design team turned to our imaginary Ethan and James to help make decisions about design features. How will James navigate the menus? Can he clearly identify the Select button? Is the design discrete enough for Ethan? Is it rugged enough to survive inside his backpack when he drops it on the gym floor? We needed to know whether the design expression makes James feel confident and Ethan feel cool.

The Intel Reader was launched in 2009 with a rich software user interface that satisfied the needs for both James and Ethan. James uses only two buttons on the Reader: one to take a picture and the other to hear the audio playback. Easy. But Ethan uses the full functionality of the Reader to access stored content and skip around in the content and even to transfer the audio to an MP3 file so he can “read” it later on his iPod.

What all these stories illustrate, whether they concern minivans or software or American families or Chinese youth, is that empathy and intimately knowing the customer through design research and listening are critical to the design response. Empathy is also an essential force to muster corporate will to follow through on an innovative or daring product that might veer from the traditional lineup. Without empathy, there would have been no pioneering Chrysler minivan, snazzy Li-Ning retail stores, or helpful iPhone screen lock. Without TurboTax, many Americans would be struggling on April 14 to fill out their tax forms, and without Mint they'd be sweating more each month to balance their family budget. Empathy and a human-centered ethos are the foundation of great design, because they place the customer first, not the marketers, analysts, or financial and engineering experts who might block that vital direct connection to the people who buy your products and services.

SUMMARY

Design starts with knowing your customers and creating a corporate culture that is keen to listen to those customers. Design research uncovers insights into their unmet wants and needs, and this knowledge leads to empathy for the customers. Designers filter this information and build it into new products and services—with an extra dose of fun and delight thrown in—to create insanely great products and services that add extra value for the customers and the company.

THE BUILDING BLOCKS

A human-centered design ethos, or empathy,

is at the heart of the design process for any product or service, whether it's cutting-edge technology, a household product, or an incremental improvement to an existing product. Empathy means listening intently to customers and closely observing how they live and interact with products and services.

Design for someone, but not for everyone.

Clearly define the person you are designing for, who is the target or ultimate customer. Not every product can be all things to all people.

Design research

takes an anthropological view of the world. It gathers qualitative information about people to understand their behaviors and motivations, whereas traditional market research focuses on quantitative data that doesn't provide designers with the information they need.

DESIGN LIKE APPLE AGENDA

Notes

1 Lashinsky, Adam, “How Apple Works: Inside the World's Biggest Startup,” CNNMoney, August 25, 2011, http://tech.fortune.cnn.com/2011/08/25/how-apple-works-inside-the-worlds-biggeststartup/.

2 Taylor III, Alex, “Iacocca's Minivan: How Chrysler Succeeded in Creating One of the Most Profitable Products of the Decade.” Fortune, May 30, 1994.