Chapter 2

Business Model

A business model defines the way a firm creates, delivers, and captures value. Often, technological innovations lead to changes in consumer behavior and to the emergence of new competitors, requiring a company to radically transform its business model. In this chapter, we’ll discuss some of the tough situations faced by companies and highlight the basic principles of new business models that firms should embrace to survive and thrive in the digital era.

Convert Razor into Blade

For a long time the music industry enjoyed significant growth by selling music in physical formats: vinyl, tapes, and CDs. Remember the days when you used to buy a CD with twelve to fifteen songs, even though you really wanted to listen only to one or two songs? Why did the music industry force you to buy twelve to fifteen songs? The cost of producing, shipping, and selling a CD did not change significantly whether a CD had one song or twelve songs, so it made sense for the industry to bundle multiple songs and charge a higher price to cover these costs. However, digital technology changed all this. The cost of reproducing and distributing music dropped significantly in the digital world and allowed iTunes to sell singles.

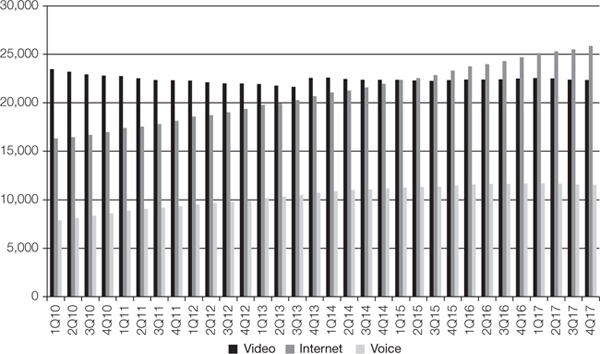

While the unbundling of music was good for consumers, it wreaked havoc on the music industry, which saw a significant drop in its revenues. The sale of digital singles (and albums) and even revenue from streaming services did not come close to equaling that which came from selling bundled music on CDs. Music piracy exacerbated the problem for the industry. As a result of these dramatic shifts, those in the business of making music (songwriters, musicians, sound engineers, etc.) also saw their incomes take a nosedive. The industry had arrived at a kind of paradox: while the popularity of music among consumers reached record highs, the music studios and artists suffered a dramatic drop in their income (see figure 2-1).

FIGURE 2-1

Revenue from the sale of recorded music in the United States, 2000–2017 ($ millions)

Source: Recording Industry Association of America.

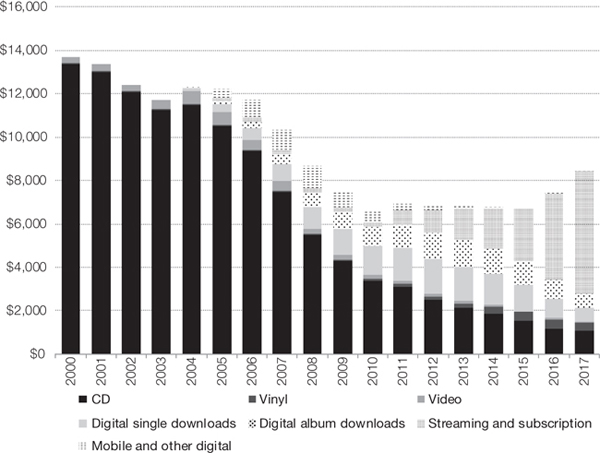

Music studios and artists had traditionally used concerts to generate awareness and excitement among fans in order to sell and make money on music albums. In other words, concerts were the razors to sell music albums—the blades.

Companies have used the razor-blade strategy for a long time: sell razors cheap to make money on the blades. HP sells its printers cheap in order to make money on the ink cartridges. As the income from the selling of recorded music (the blades) declined, studios and artists converted the razor (i.e., the concerts) into blades, or the money-making part of their business. Suddenly free and even pirated music became the cheap razor to drive fans to the expensive concerts (see figure 2-2).

FIGURE 2-2

Revenue from concerts and from the sale of recorded music in the United States, 2000–2017 ($ millions)

Source: Recording Industry Association of America and Pollstar.

Artists have benefitted from this shift, since the percentage they generally receive on concert revenues exceeds the royalties they receive from the sale of music albums.

Artists have also been able to exploit the popularity of their music by entering into direct partnerships with brands. Companies such as Mastercard offer their customers unique experiences by inviting music artists to perform at special events that have become a lucrative source of income for the artists. Global revenue from live music performances is expected to be more than $28 billion by 2020.1

Most companies have multiple sources of revenue, often from complementary products. As we discussed in chapter 1, complements provide a new source of competitive advantage in the connected digital world by increasing consumers’ switching cost. Even if you think your iPhone is similar in its product features to a smartphone from Samsung, you will find it hard to switch to Samsung if you use Apple’s complementary products and services, such as iTunes, FaceTime, and Apple Pay. And complements offer another key advantage: as technology affects a company’s profitability, it can transform the company’s business model by shifting revenue sources from one product/service to another, effectively converting a razor into a blade.

The New York Times (NYT) went through a similar transformation. Like the music industry, newspapers witnessed unbundling due to digital technology, which resulted in the loss of a large portion of their classified advertising revenue to Craigslist, Monster.com, and others. To compensate for the losses in print, every newspaper built an online presence with the hope of reaching a much larger audience around the globe and of generating lots of money in online advertising. While newspapers did reach a large global audience—in 2012 NYT had thirty million unique visitors per month on its website—the online ad revenue was not enough to compensate for the loss of print advertising.

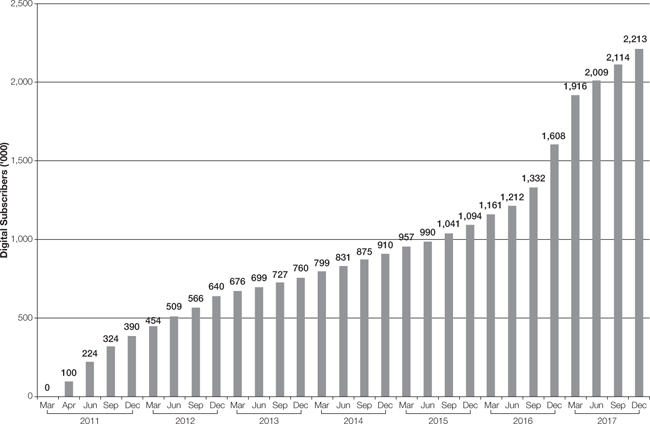

Newspapers like NYT were facing a dilemma. For decades they had sold subscriptions at a low price (the razor) to generate revenue through advertising (the blade). In the online world the razor was completely free, and the blades weren’t selling like they used to. Was it time to convert this razor into a blade? In March 2011, NYT decided to create a paywall and made its website restricted. Users would get free access to twenty articles per month, after which they had to pay. This was a bold move in an era when everyone believed that information should be free. Critics wondered why anyone would pay for access to the NYT’s website when they could get free news through Google. However, NYT believed that consumers still cared about reliable journalism of high quality. The value of a newspaper is not simply in information—anyone can tweet or blog and create information, fake or real. The value is in the curation of that information. Through careful design and pricing, NYT successfully launched its paywall, and by June 2017 it had over two million digital news subscribers (see figure 2-3). In 2000, advertising accounted for almost 70 percent of NYT revenue. During the first half of 2017, over 70 percent of NYT revenue came from subscriptions, a large portion from digital subscribers. The razor has become the blade!

Digital subscribers to the New York Times

Source: Compiled from NYT press releases and financial reports.

Note: The numbers show digital news subscribers only and do not include subscribers to other digital products such as cooking and crosswords, and print subscribers who have digital access to the NYT.

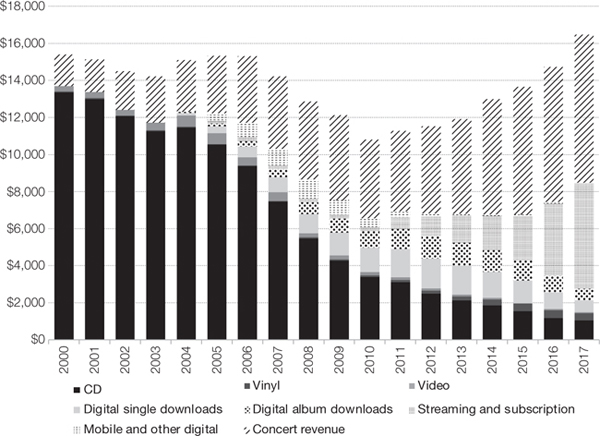

Cable companies such as Comcast are facing similar pressures, as consumers are willing to cut the cord and subscribe to streaming services like Netflix and Hulu. Once again the bundled offering is falling apart in the digital world. New competitors such as Sling TV are offering skinny bundles at low prices to entice consumers. While cord cutting is a topic of significant debate among experts who disagree if this is a relatively limited phenomenon or one that is destined to grow, it is nonetheless a major concern for Comcast, which derives the bulk of its revenue from cable. However, even as cable TV revenue comes under threat from streaming, broadband services provide Comcast a new blade (see figure 2-4).

Shifting the sources of income among complementary products, or converting a razor into a blade or vice versa, is a powerful way not only to manage your own profitability but also to disrupt another industry. For example, Amazon can help its sellers grow by offering them loans at a much lower rate than banks can, since Amazon can use these loans as a razor to make money on the seller transactions (the blades) on its platform. This disrupts the market for small-business loans and makes it difficult for banks to compete.

So, what are your razor and your blade?

Find New Ways to Capture Value

As technology disrupts a company’s business model, the company needs to find new ways to capture value, as demonstrated by The Weather Company and Best Buy.

Turbulent Times for The Weather Channel Company

When David Kenny joined The Weather Channel Company (TWCC) as CEO in January 2012, he inherited an organization that was facing significant challenges. For decades, the company had steadily grown its revenues by selling advertising on its twenty-four-hour cable weather TV channel. Hitching its business model to the ever-increasing American appetite for cable TV had been a sure bet for TWCC . . . until suddenly it wasn’t.

In 2010, the number of cable TV subscriptions in the United States began to slide downward—and continued to fall lower and lower, even as economic conditions improved following the recession. As the cable-subscriber numbers crept down, TWCC was worried that its business model, which relied heavily on TV advertising, would no longer cut it in a world where consumers used apps, online videos, and websites to get news as easily as, or more easily than, they could by turning on the TV. The company was not blind to digital trends and had launched its own website and mobile app. Following the introduction of the iPhone, in 2007, TWCC developed a mobile app that users could download for $3.99. But by 2009, the mobile revenue was a mere $3.5 million. To jump-start its mobile business, TWCC changed its model to one in which the app was free and revenues would be derived from mobile advertising. Although this made its mobile app the second-most-downloaded app for the iPad, consumers checked the weather app for only a few seconds at any given time, which made ad-based monetization difficult.2 With a declining TV audience and a mobile monetization challenge, Kenny faced the task of transforming a company built by the rising tide of cable TV into a modern, weather-oriented media conglomerate.

Landmark Communications had created TWCC in 1982 as the first-ever twenty-four-hour weather channel on cable TV, following in the footsteps of the newly minted twenty-four-hour news channel format started by CNN in 1980. For many years, TWCC made money by selling advertising on its TV channel as well as through subscription fees that cable operators, such as Comcast, paid to TWCC in order to carry its channel in their cable packages. The company also operated a business-to-business, or B2B, subsidiary, Weather Services International (WSI), which provided weather information to businesses such as airlines and insurance companies. In 2008, Landmark sold the company for $3.5 billion to a group consisting of Comcast and two private-equity firms. By 2012, the company’s TV business accounted for roughly 60 percent of total revenue, but the channel was suffering from an eight-year decline in ratings.

Reflecting on the situation he faced, Kenny, in a personal interview with the author, said,

When I joined TWCC, I saw a company that was heavily reliant on TV, and although it was active in new media, it was moving slowly. We were facing competition from many new digital players, including app developers and weather startups. Google, with its deep pockets and fast processing speed, could use publicly available National Weather Service data to quickly become a player in our space. The question that I focused on the most was, how do we add value to consumers and our partners in this new environment?

Kenny had a key insight that drove the vision for the company: “People use weather, which is inherently local, to plan their day,” he said. “What if we provide them relevant information to help them in this critical task?” Suddenly, the company saw itself not simply providing weather forecasts but also helping consumers plan daily activities that may be affected by weather. To reflect this new vision, in September 2012, Kenny proposed to the board that the word channel be dropped from the company’s name, and so it became The Weather Company. And he set an ambitious goal: to grow from $600 million in revenue in 2012 to more than $1 billion by 2016. To achieve this, Kenny followed a particular philosophy: “Think big, start small, scale fast.”

The consumer trend away from TV toward mobile apps was both a challenge and an opportunity. In 40 percent of all smartphones, a weather app is the first app in the morning and the last app at night that people check. However, this daily habit does not last very long since most consumers check weather for only a few seconds. The challenge for The Weather Company was to engage consumers for longer periods.

“We were among the most trusted brands, but we lacked personality,” noted Kenny. To attract and engage millennials, Kenny transformed The Weather Company’s consumer-facing properties into “platishers,” a combination of platforms and content publishers. To lead this effort, he hired Neil Katz—who had previously worked at Huffington Post—as editor in chief of Weather.com. Soon, the company’s website began to move away from showing only syndicated content to creating original stories and videos that were weather- or nature-themed. The company began publishing short videos, such as “Virus Hunters” (about super viruses that could threaten humanity), “Grid Breakers” (about explorers in extreme weather), and “What Does Mars Smell Like?” Lots of the newly developed content also found its way into the company’s mobile app. Not everything worked (e.g., content featuring exercises for a bikini body), but Kenny’s philosophy of learning by experimentation provided new energy and a sense of empowerment to the employees. The new content nearly doubled the amount of time users spent on the site, which in turn led to better advertising partnerships.

Building on his key insight that consumers check local weather to plan their daily activities, Kenny decided to link science with big data to understand consumers’ decisions. In May 2012, he hired his former colleague Curt Hecht, from Publicis, to recreate the way ads were sold. One of Hecht’s early insights was that weather affects the sales of many products. So the company built a platform, WeatherFX, to predict demand based on weather and location. Hecht and his team persuaded retailers and manufacturers to share sales data on every product sold, in every store location, over the last five years. Then the team correlated sales with local weather conditions and forecasts at that time of the year. This created a powerful predictive algorithm of how weather drove consumers’ purchasing decisions.

The goal was to go beyond predicting the obvious relationships (like increased sales of umbrellas when it is raining), and indeed, Hecht and his team found many surprising correlations. Some were hard to explain, such as that strawberries and raspberries sold far better when it was humid outside! Others made a lot of sense after some reflection. For instance, at a particular dew point, people in Dallas rush to buy bug spray . . . because insects’ eggs hatch at that dew point. Yet other insights were intriguing. During bad weather, for example, women worry about logistics, such as getting kids from school or groceries from the market. For men, by contrast, the same inclement weather seems an occasion for watching sports, hosting parties, and buying beer.

The next step was to leverage these insights for commercial purposes. The Weather Company helped retailers decide when to put products on promotion. But just as important, it helped retailers know when no promotion was needed to quickly sell a product. The company then moved on to work with brands like Pantene by showing that consumers buy different types of shampoos based on weather forecasts for the next three days. Pantene started running location-specific ads on The Weather Company’s mobile app and offered a custom tool, “Haircast,” to tell consumers which hair products to use during different weather conditions. Sales of Pantene’s advertised products jumped 28 percent.

The WSI division of the company, as previously mentioned, was already providing weather information to several industries, such as airlines, retailers, and insurance companies. But the new vision that Hecht helped create revealed new possibilities. Just as pilots need weather data to avoid turbulence and make corrections to their flight path, car drivers could also benefit from weather information. The Weather Company struck a deal with BMW to provide weather data in its new cars. In exchange, BMW allowed weather sensors to be placed on the windshield wipers of certain new models so that the motion of the wipers would inform The Weather Company when and where it was raining, which would then further improve the accuracy of The Weather Company’s forecasts.

“Weather affects everything,” explained Kenny, “and as a result, it offers amazing new opportunities for us.” Tesla owners could benefit from the company’s forecasts, since weather conditions affect the battery life and the driving range of Tesla’s electric cars. A partnership with Nike could link weather data to shoes and running applications. Farmers could better manage their crops by installing irrigation systems with built-in chips that receive weather information.

Kenny also looked to partner with companies that could help expand The Weather Company’s global reach. IBM’s consulting division licensed The Weather Company’s data to sell as a product to its clients, including governments, across the globe. Weather data was a centerpiece of many of IBM’s consulting initiatives, including smart cities. The Weather Company also provided weather data to companies like Mahindra, an Indian tractor manufacturer that produces driverless machines that analyze the soil as they move through the field to dispense only as much fertilizer as is needed according to the soil’s profile and expected weather patterns.

By July 2015, almost half of The Weather Company’s employees had joined after Kenny’s arrival. Kenny attracted digital stars, revamped his senior leadership team, and inducted new members into his board. Offices in New York and San Francisco scaled up to bring in talent that could not be recruited into the Atlanta headquarters. A sense of urgency was now palpable in the company. “I am obsessed with velocity,” said Kenny. With a clear direction, The Weather Company, on his watch, transformed itself in a short period of time.

In January 2016, IBM acquired The Weather Company for about $2 billion and David Kenny became the head of IBM Watson with the goal of doing for IBM what he had done for The Weather Company.

Best Buy: Managing the Challenge Posed by Amazon

When Hubert Joly joined Best Buy as its CEO in September 2012, he faced a number of challenges: There was a shareholder challenge, as the company’s founder was attempting to take the company private. There was an operational challenge regarding how to deliver the best possible customer experience. There was a leadership challenge, as the prior CEO had been hurriedly replaced amid allegations of misconduct. And, finally, there was the strategic challenge of competing with Amazon—as Best Buy was increasingly becoming Amazon’s showroom, where a consumer would, for example, see a camera in a Best Buy store, get all the information and advice from the salesperson, but later buy the camera on Amazon for a cheaper price. As a result, Best Buy had seen a dramatic decline in its revenues and profits, and its very survival was in question.

To address these challenges, Joly crafted a “Renew Blue” strategy that addressed Best Buy’s two biggest problems: declining same-store sales and decreasing operating margin. While “Renew Blue” encompassed many different factors—ranging from investing in price matching and improving the online shopping experience to improving the customer experience in stores and finding $1 billion worth of cost savings by eliminating operational inefficiencies—one of its key pillars was to leverage Best Buy’s stores and strengthen the company’s relationships with vendors.

“We were the ‘last man standing’ at the time, since we were the only consumer-electronics store with national presence in the [United States],” said Joly. “We had six hundred million visits to our stores each year—some used to say that our stores would be a liability, but we truly believed those visitors were coming to Best Buy for a reason.” These store visits were also critical for Best Buy’s vendors, such as Samsung, LG Electronics, Sony, and Hewlett-Packard, companies that did not have a national footprint of stores in which to display their products. Joly saw a win-win opportunity for Best Buy and its vendors, an opportunity for those vendors to showcase their products in Best Buy stores in order to provide the best possible customer experience.

In a 2012 interview, Joly mentioned that Best Buy was seeking to strengthen its partnerships with vendors. Shortly thereafter, the head of Samsung Electronics reached out to Joly to establish a new type of arrangement between the two companies, and as a result Best Buy agreed to install 1,400 Samsung “shops” within Best Buy stores. Since it was typically not cost-effective or strategic for manufacturers like Samsung to open their own stores, this arrangement provided a unique benefit. The branded store-within-a-store, which employed dedicated Samsung sales staff, helped Samsung very quickly gain more visibility and engage directly with customers. In return, Best Buy got a fee for showcasing Samsung’s products, similar to the fee paid by consumer packaged-goods firms to supermarket retailers.

Following the success of Samsung Experience Shops, as they were called, Best Buy formed or expanded partnerships with the world’s foremost tech companies, including Amazon, Apple, AT&T, Canon, Google, LG, Microsoft, Nikon, Sony, Sprint, and Verizon. Each vendor made an investment to fund its store-within-a-store. The investment covered things like the cost of in-store fixtures, labor, marketing, and training as well as the fee for Best Buy. With such partnerships, Best Buy evolved and augmented its business model to embrace both its strengths and the needs of the company’s vendors. Although it still made the bulk of its revenues from product sales and services, these new stores-within-stores offered Best Buy upside potential and a way to capture the value Best Buy had already been creating for consumers and vendors alike.

This new strategy worked: comparable store sales and operating income improved, and total shareholder return during 2012–2017 was 642 percent, placing Best Buy among the top 10 percent of S&P 500 companies in that time period. This is especially impressive given that all major retailers in the United States were (and still are) facing tremendous pressures. Circuit City, Radio Shack, and H. H. Gregg, three large electronics retailers, declared bankruptcy in 2008, 2015, and 2017, respectively, and Toys “R” Us announced bankruptcy in March 2018.

The success of Best Buy’s “Renew Blue” strategy shows that physical stores can be great assets and that retail is not a zero-sum game against a single competitor. It also illustrates an often-observed reality: shifts in technology and changes in consumer behavior typically disrupt companies by significantly affecting their source of income even when these companies continue to create tremendous value for their customers. The old ways of capturing value may no longer work, and companies need to find new and often hidden sources of value. When threatened by Amazon, Best Buy partnered with its own vendors to create a win-win situation and found an additional source of revenue while providing consumers great experience.

2018 and Beyond

After the success of “Renew Blue” Hubert Joly and his team embarked on a new growth strategy, called “Best Buy 2020: Building the New Blue.” The company has stated that its purpose is to help customers pursue their passion and live their lives with the assistance of technology, a much bigger idea than merely selling products. As such, the company is vastly expanding its addressable market from just hardware products to services and solutions, including subscription services (a topic we will discuss in detail later in this chapter).

This strategy is based on a few key observations. First, the company is operating in an opportunity-rich environment. Consumers are spending more and more on technology products, and Best Buy is well positioned in this market, having captured more than 16 percent of millennials’ spending in this category. Second, buying technology products is typically part of a complex decision that involves integration across many different products from various manufacturers. Thus, Joly and his team based the new “Best Buy 2020” strategy on two main pillars: “expand what we sell” and “evolve how we sell.”

To expand what it sells, Best Buy is using its strong skills and assets to move into areas such as smart-home management, assisted living (for a population that is aging), and total tech support. In its tech-support pilot, the company is testing a subscription service wherein consumers pay $199 per year or $19.99 per month for unlimited phone, online, and in-store service in addition to discounted in-home service from its tech advisors. As of March 2018, this service was available in all Best Buy stores in Canada and in about two hundred US stores in specific geographies and states. In addition, Best Buy is “evolving how it sells” by continuing to build its online channel and by introducing its in-home channel, through which Best Buy advisors will come meet customers in the comfort of their own homes, free of charge, to listen to their needs and provide recommendations for products and services.

This new strategy highlights the shift in Best Buy’s business model from simply selling products to selling solutions and from processing mere transactions to building a deeper relationship with its customers.

Create Value through Experiences

Best Buy is not alone in facing the pressure from Amazon and e-commerce. The future of the entire retailing industry is uncertain, and retailers are declaring bankruptcy at an alarming pace.

In 2015 alone, Body Central Corp. (a women’s-clothing retailer), Quiksilver (surfwear retailer), American Apparel (clothing retailer), Wet Seal (teen fashion retailer), and Sports Authority (sporting-goods retailer) declared bankruptcy in the United States. Some of the largest department stores, such as Macy’s, are also facing severe financial pressure. As their business shrinks, these retailers are closing stores at a pace that in turn is threatening the very survival of shopping malls. Some retail analysts predict that a third of America’s shopping malls are likely to shut down in the coming years.3

Supermarkets are also under threat. A&P, the pioneering grocery company that drove independent grocers out of business nearly a hundred years ago, itself declared bankruptcy in 2015. Tesco, the leading supermarket in the United Kingdom, is also showing signs of trouble. Retailers such as Borders bookstore and video-rental giant Blockbuster are gone.

What is the future of retailing and brick-and-mortar establishments in the digital age? Perhaps it is time for them to rethink their business model and shift from selling products to selling experiences. These retailers can learn from Starbucks, which started by selling not just coffee but also an experience, endeavoring to become the “third place” in people’s lives (after their homes and their workplaces). But how do you develop an experience-based business?

Reinventing a Grocery Store

In 2007, Oscar Farinetti, an Italian entrepreneur, founded Eataly in Turin, Italy, as a unique, complementary blend of restaurants, a supermarket, and a culinary school—all under one roof—to let customers eat, shop, and learn about Italian food. Essentially, Farinetti reinvented the grocery store.4 By 2016, Eataly had grown from a single store in Turin to thirty-one stores across the world, in cities such as Milan, Rome, New York, Chicago, Boston, Istanbul, Dubai, Tokyo, Munich, and Seoul. And it had ambitious plans to expand its global reach to cities such as Copenhagen, Moscow, and London. Eataly focused on customer experience by making careful strategic choices.

- Concept and Store Design. Supermarkets have traditionally relied on providing convenience, variety, and low prices to consumers. While some newer players, such as Whole Foods, have focused on organic, high-quality fare with fresh food bars, Eataly took this concept to new heights by combining a super-market with several monothematic restaurants and culinary schools about Italian food and cooking.

Why does Eataly combine restaurants, a marketplace, and a culinary school all in one store? There are several advantages to this concept. First, restaurants create the buzz and traffic that lead people to buy products in the marketplace. No one wants to shop in an empty store. Making fresh cheese or pasta right in front of consumers also creates theater that enhances user experience.

Second, restaurants create an environment with lots of social interaction in the middle of a supermarket, which provides a unique experience for customers, allowing Eataly to charge higher prices for its products.

Third, Oscar Farinetti realized from an earlier mistake that restaurants alone are not very profitable. They are a risky venture, with a failure rate of almost 80 percent in large cities.

Fourth, restaurants have a capacity limit. You can turn the tables over only so many times per day, after which there is no possibility of growth unless you somehow expand the seating. Finally, restaurants help reduce wastage or shrinkage of fresh food or food with expiration dates. Shrinkage in a typical supermarket is about 2 percent, and for perishable products is as high as 6 percent to 7 percent. Industry experts believe that eliminating shrinkage could easily double the profitability of the industry.

- Store Size and Location. Combining restaurants and open displays of food preparation, which are essential ingredients for creating an experience, requires additional space—one of the main reasons Eataly stores tend to be large. Eataly has a 50,000-square-foot store in the middle of Manhattan, and a 63,000-square-foot store in the center of Chicago. A typical grocery store has about half the square footage of an Eataly store but stocks almost three times the number of items. Eataly locates its stores in the heart of big cities in order to generate traffic. In other words, it expects its stores to be destinations, places to which customers come from all over the city in search of a good experience, not convenience.

- Marketing and Promotions. Eataly spends almost nothing on marketing. Its marketing consists of in-store displays that tell the origin and story of its products. These displays have a clean and simple design and do not look like typical in-store advertising. Price is almost never mentioned. In-store communication is the main promotional policy, along with events designed and hosted to attract new customers to its stores, and to give food bloggers a reason to continue writing about Eataly—a brilliant form of free advertising. In other words, Eataly leverages social media to market itself at low cost while also continuously changing the stores to attract repeat customers.

How does Eataly’s approach compare with that of traditional supermarkets? The latter compete largely on the basis of price and offer weekly discounts on a variety of products to attract customers to their stores. Manufacturers and suppliers typically fund these promotions by giving trade allowances to retailers to pitch their respective brands. This has made supermarkets heavily reliant on trade allowances and has given immense negotiating power to suppliers.

- Metrics. Retail stores typically measure their performance on the basis of sales or revenue per square foot. However, Eataly eschews such a metric. Commenting on this, Oscar Farinetti said, “[I]t is useless to calculate sales per square meter when we create sales points that are totally different.”5 Alex Saper, the general manager of Eataly USA, elaborated on one of those different sales points: the fresh pasta station. On Saper’s watch, Eataly removed shelves of potentially salable goods just to create spaces in which shoppers could observe fresh pasta being made by hand. It was a bold gamble, but as Saper noted, sales of fresh pasta subsequently increased by 15 percent to 20 percent. “And the reason,” he said, “is that we are selling emotion, we are selling theater here.”6

Oscar Farinetti wants to bring Italian food and its experience to the world, the way Howard Schultz, chairman of Starbucks, brought the Italian coffee experience to everyone. And by 2016, Eataly had built a global brand with half a billion dollars in revenues, healthy profitability, and an aggressive plan to grow all around the world.

Starbucks and Eataly provide powerful lessons for many other industries. As consumers move away from products to experiences, creating value and sustainable advantage will not be based on product features alone. Just like Blockbuster, movie theaters could have been wiped away by Netflix and streaming services. But instead of lowering prices and selling more popcorn, movie theaters in North America are installing reclining chairs akin to business-class seats in an airline, providing seat-side food and wine service, and charging more than double the price they charged before. As a result, movie theaters in the United States and Canada have seen their sales grow from $7.5 billion in 2000 to more than $11.1 billion in 2015, and concession sales in theaters continues to show robust growth.

The move away from products to experiences is evident even in American shopping malls, which were once vast emporiums of products of all types. As the retail environment changes, Simon Property Group, a real-estate giant that operates 108 shopping malls in the United States worth $110 billion, is reinventing the shopping mall for the future. Malls emerged in the 1960s when Melvin Simon (the company’s founder) had the brilliant idea of using a department store as an anchor for a shopping center. Department stores used to attract lots of traffic as stand-alone properties in city centers, and to entice them away, Melvin Simon offered them highly subsidized rent. Even today these anchor stores pay about $4 per square foot annually compared with $42 paid by nonanchor stores.7 But as the fate of department stores has changed due to e-commerce, David Simon, the current CEO of the Simon Property Group, is replacing many of these department stores with restaurants and movie theaters to position malls as a place for experience.

Build an Asset-Light Business

Almost a century ago automobile manufacturers settled on a system of franchising whereby independent dealers would sell mostly a single company’s models. Over time these dealerships have become large businesses in their own right, with many boasting sales in billions of dollars. Until recently, the business model of dealers has remained largely unchanged. Dealerships typically stock hundreds of cars on a large lot (away from city centers to reduce real estate costs), and consumers drive several miles to these lots to see and test-drive cars and to negotiate prices.

However, in the last decade consumer buying behavior has changed dramatically. Studies by Google show that most consumers start their search online about two or three months before they actually buy a car. By the time consumers come to the dealer, they know everything about the car and the various options they want to buy. Surveys also show that consumers hate visiting dealers. They find the experience boring, confrontational, and time-consuming. A study by McKinsey found that ten years ago Americans visited an average of five dealers, perhaps to compare and negotiate prices, but now they visit 1.6 dealers on average, because online services such as TrueCar offer price transparency. Today, the only compelling reason for consumers to visit a dealer is to test-drive a car.

But what if a dealer were to send the two cars that you wanted to test drive to your home at a time that was convenient for you? And what if you had to wait only four to six weeks for a car that was made-to-order, with all the features customized to your taste? Studies by Autotrader confirm that as in-car technologies become increasingly important, consumers are willing to wait longer to get specific features in their car.

There is really no need for dealers to follow a capital- and asset-intensive model anymore. Some auto manufacturers are already embracing this new reality. Tesla does not have traditional dealers. Instead it has showrooms in shopping malls. In the last few years, Audi has opened digital showrooms in London, Beijing, and Berlin. These showrooms are much smaller than their traditional counterparts and display only four models. They are located in the heart of the city to make it easy for even casual car buyers to visit and explore cars, and they offer large multimedia screens for consumers to configure and customize their vehicles. In its first year after opening, in 2012, Audi’s London City showroom had 50,000 visitors and sold an average of seven cars per week, with 75 percent of the orders placed by first-time Audi buyers. On average, customers paid 120 percent of the car’s base price, since the digital showroom encouraged them to configure their cars by adding lots of technology options. Perhaps the most intriguing part is that 50 percent of the customers in the first half of 2013 never bothered to test-drive the car.8 As virtual reality becomes mainstream, visiting a dealer to test-drive a car may become a thing of the past. And dealers would benefit from this new asset-light business model.

Gas Station of the Future

Let’s extend our thinking to reimagine the gas station of the future. For almost a century, gas stations have looked and functioned pretty much the same. Granted, they have become cleaner, made payment easier, and are now often integrated with a convenience store. But the fundamental model of a gas station has remained unchanged. Although electric cars may eventually alter this landscape completely, we will still have gas stations in the near future.

Any business model has to start with solving customers’ pain points and then thinking about how to make that solution economically viable for the company. So let’s start with the customer pain point. Do consumers enjoy going to the gas station to fill up their cars? The answer is an unequivocal no—it is a necessity that we all have to endure but will be happy to do without if possible.

What if the gas station were to come to you instead of you having to go to the gas station? In other words, what if a fuel truck were to come fill your car while it was parked in the parking lot of your company or a shopping mall (delivery to individual homes would be too expensive and inefficient). Sound impossible? There are several startups, such as Booster Fuels, Purple, Filld, and WeFuel, that are already offering this service. You simply order fuel through their apps, indicating a time and a place. In the future, cars may be equipped with sensors that automatically alert you and your fuel app that your car needs refueling. And you don’t even have to pay a premium price for this service. How can these companies make this model work? By delivering gas to you they don’t have the high fixed cost of the gas station. Note that gas stations are often sited in prime locations in a city to make it convenient for consumers, but this also leads to very high real estate costs for the stations. By eliminating this fixed cost, the new players can charge the same price as existing gas stations, provide added convenience to consumers, and still be profitable.

Transition to Product-as-a-Service

In April 2015, Amsterdam’s Schiphol Airport, Europe’s fourth-busiest airport, reached an agreement with Philips, the global leader in lighting, and Cofely, an energy services company, to pay for “lighting as a service” in its terminal buildings. In this so-called pay-per-lux arrangement, Schiphol pays only for the light it uses, while Philips maintains ownership of all light fixtures and remains responsible for their maintenance and upgrade. With this new business model Philips is no longer selling light fixtures and light bulbs (the inputs). Instead, it is being paid for the light (the output) used by its customer. As a result Philips is developing special lighting fixtures that will last 75 percent longer than the conventional fixtures. By using energy-efficient LED bulbs, it hopes to achieve a 50 percent reduction in energy consumption.9

Schiphol was not the only Philips customer opting for lighting as a service. A year earlier, Philips signed a ten-year contract with the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority in the United States for its twenty-five parking facilities. This arrangement required no up-front cost for Washington Metro, which expected to fund the entire contract through the $2 million in annual savings in energy consumption and maintenance costs.10

Philips is not alone in adopting this new business model. In its “pay-per-copy” model, Xerox retains ownership of its office equipment while customers pay for the copies made on these machines.11 Atlas Copco, which produces compressors and air-treatment systems, now offers its customers a “contract-air” arrangement whereby they can pay per cubic meter of compressed air.12 Rolls-Royce offers its airline customers “power-by-the-hour,” whereby customers pay engine repair and service costs pegged only to those hours the engine is in use. Michelin has introduced a similar “pay-per-mile” program for the use of its tires. Hilti, the tool manufacturer, introduced a fleet-management system in which customers pay a monthly subscription fee to get tools on-demand instead of buying them. Using RFID chips to track the usage of these tools, Hilti can anticipate problems, do preventive maintenance, and reduce customers’ downtime. These chips also significantly reduce tool theft at construction sites. With this program, Hilti’s customers benefit from access to the latest tool fleet, less downtime, greater reliability, and an improved cash flow, since there’s no need for a large up-front investment. During the global crisis of 2008–2009, the fleet-management system was instrumental in increasing Hilti’s sales by 26 percent and its operating profit by 12 percent.13 In the new partnership between GE Oil and Gas and its customer Diamond Offshore Drilling, GE owns the equipment and is responsible for its maintenance. Diamond pays GE Oil and Gas only for the days when the equipment is working.14

Product-as-a-Service for Luxury Products and Automobiles

The product-as-a-service model is not limited to industrial products. Almost any company can rethink its business model in these terms. Consider LVMH, which has prided itself on creating the best-quality products and selling them to exclusive clients at very high prices. A typical LVMH handbag sells for a few thousand dollars, and the company’s crocodile-skin City Steamer satchel with engraved padlock and a nametag can fetch $55,000. Similarly, automobile manufacturers like BMW have perfected the engineering of their products, and their midsize luxury cars would reduce your bank account by $60,000 or more.

These companies have always focused on their products, but can they benefit from reimagining their business model and making those products available the way Philips does its light bulbs or Michelin its tires? What if LVMH were to create a service in which subscribers would pay a low monthly fee to get an LVMH bag from a curated list every month? A consumer who could not buy a dozen (or perhaps even one) of these expensive bags would now have the possibility to possess a different bag every month, and for different occasions. Such a service would open up a large and new customer base for LVMH. Several startups, such as Bag Borrow or Steal, have recognized this consumer need and are already offering such a service. Two of my former MBA students, Jennifer Hyman and Jennifer Fleiss, started Rent the Runway with a similar idea of allowing young women to rent expensive dresses rather than having to buy them.

Car companies could benefit from a similar business model. Why do I have to buy a car for $60,000 and drive the same vehicle for the next five years? What if BMW offered a monthly subscription service that allowed consumers to access any car from a curated list? I could drive a sedan on a weekday and a convertible on the weekend. Again, this subscription service could open up a whole new market of consumers for BMW, people who could never afford to buy a BMW otherwise. Interestingly, in 2017 Cadillac started such a subscription plan. For $1,500 a month, members can trade in and out of Cadillac’s ten models up to eighteen times a year. Following Cadillac, Porsche also launched its $2,000 per month subscription service, Porsche Passport, which allows customers to flip between Porsche Cayman, Boxster, Macan, and Cayenne as their needs change. Clutch, a startup in Atlanta, is also offering a monthly subscription service that lets you flip between cars every day.

A New Business Model

As global competition for products intensifies and product differentiation diminishes, it is not surprising that companies are relying more on services for their growth and profitability. Service contracts, replacement parts, and maintenance fees were always an important source of revenue for companies, but product-as-a-service is fundamentally a different business model for the following reasons:

- Outcome-Based. As the examples mentioned above show, the focus in this model is on the outputs or the outcomes for customers, not on the input or the product that the company manufactures. Why is this important? Consider the case of Rolls-Royce, which sells jet engines to its airline customers. In the traditional service model, every engine problem and maintenance need was a revenue opportunity for Rolls-Royce, even though this downtime was costing its customers millions of dollars. In other words, the incentives for Rolls-Royce and its airline customers were not aligned. However, under the outcome-based model, Rolls-Royce is paid only for every hour the plane is flying, thus aligning the incentives for both parties.

- Improved Reliability and Reduced Cost. When a manufacturer retains ownership of and maintenance responsibility for its products, the incentives of the company and its customers are aligned, because the company is motivated to improve the reliability of its products, extend their life, and reduce their operating cost. Rolls-Royce dramatically improved engine reliability and reduced unplanned downtime for its customers as a result of its power-by-the-hour model. The same motivation drove Philips to design lighting fixtures for Schiphol airport that last 75 percent longer. The pay-per-copy model led Xerox to develop an extensive remanufacturing program that saved raw material and reduced waste. A similar program at Philips not only led to cost savings but also helped the company move toward its goal of sustainability.15

- Expanded Customer Base. In many B2B settings the capital cost of the product can be prohibitive, especially for small customers. By retaining ownership and maintenance responsibility, a firm can expand its customer base to those who would not be able to afford the product otherwise. It would have been difficult for Washington Metro to replace and upgrade all its lighting fixtures to reduce its operating costs, but the pay-per-lux model allowed it to benefit from the energy savings without the up-front capital investment. By offering car rental by the hour ZipCar expanded the market to students and infrequent users.

- Customer-Focused Innovation. An outcome-based model drives a company to become customer-focused and thereby changes the company’s innovation process. Ted Levitt, a Harvard Business School professor, once said that people don’t buy drills; they buy holes. While a product-focused company would continue to make its drills better, a customer-focused company would think of new technologies, such as laser, which could be used to achieve the outcome (in this case, creating a hole) that the customer is looking for. Michelin’s pay-per-mile program led it to find innovative ways to get more out of its tires. Its research showed that a third of all breakdowns are tire related and that 90 percent of these are due to incorrect tire pressure. As a result Michelin launched a suite of connected software solutions that, along with its tire-pressure-monitoring system, is designed to help trucking managers whose fleets ride on Michelin tires to optimize the performance of those fleets. This customer focus also helped Michelin realize that fuel represents 29 percent of the per-kilometer operating cost of a forty-ton tractor trailer. So the company launched a new service to help the managers of trucking fleets reduce their fuel consumption. Since its launch, the service has delivered average savings of 1.5 liters per 100 kilometers to its trucking customers, which for the entire European trucking industry would translate into savings of three billion liters of fuel, nine million tons of CO2, and €3 billion in operating cost.16

- Organizational Shift. The product-as-a-service business model leads to significant shifts both within and beyond the organization. The sales force needs to change from selling machines to selling outcomes, and customers who are used to buying products also need to be educated and convinced about this shift. Highlighting the challenge in selling outcome-based services, Bill Ruh, the CEO of GE Digital, noted, “Before we targeted an existing budget line item, but if you are promising to save fuel burn costs, a budget line item does not exist for that, posing a problem for a box-seller.”17 Jim Fowler, GE’s chief information officer, elaborated, “Changing to an outcome based model means willing to be [in] an environment where you don’t know everything about everything that you’re working on. For people who are very risk averse, that’s an uncomfortable place to be.”18 The company also needs to build skills to manage customer relationships over long periods of time. BMW’s launch of its hourly rental service, BMW DriveNow, requires it to develop both analytical and customer-relationship-management capabilities. This model also has financial implications, since the company does not get the large up-front revenue from the sale of its product. Instead, the revenue trickles in over many years. Customer retention in this approach becomes critical.

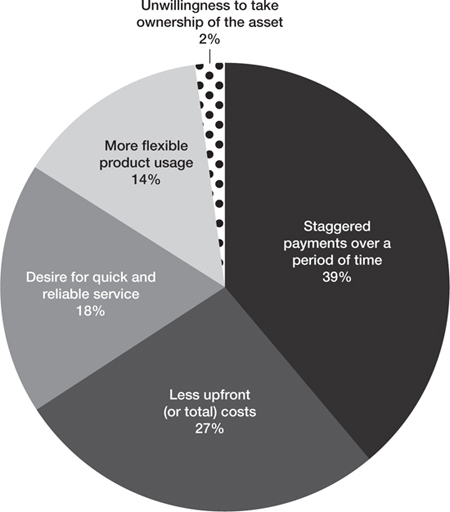

According to IDC, a global market-intelligence firm, 40 percent of the top one hundred discrete manufacturers (who produce finished products such as automobiles) and 20 percent of the top process manufacturers (who combine ingredients such as in the chemical and food industries) will offer product-as-a-service by 2018.19 There’s also been significant acceptance of product-as-a-service and pay-per-use pricing among consumers. In a 2012 survey of over 2,200 consumers in the United States and Europe, Accenture found that payment models such as pay-per-use and power-by-the hour were preferred by an overwhelming 70 percent of consumers to the full up-front product purchase (see figure 2-5).20

FIGURE 2-5

Why consumers accept service-based payment models

Source: Vivek Agarwal, Vinay Arora, and Kris Renker, Evolving Service Centric Business Models: Quest for Profitability and Predictability, Accenture Report, 2013.

As we move toward a demand-based economy, access, not ownership of products, will drive the success of businesses. This shift will make the product-as-a-service model increasingly important in the future.

We will continue to see the emergence of new business models and new rules of engagement. Digital technology is not necessarily a threat to incumbents. It often provides a new set of opportunities if the companies are willing to rethink their business models.