Chapter 3

Platforms and Ecosystems

When Johannes Gutenberg invented the printing press around 1440, he revolutionized the dissemination of ideas to the masses through books and other printed material. Today the global printing industry is worth over $800 billion, more than fifty times the size of the music industry. While digital printing is replacing offset printing and print volume is declining, shift to higher-value products has led to a growth in print revenues that is expected to continue until 2020.1

Although printing technology has evolved in the last six centuries, the printing industry remains highly fragmented. Thousands of small and medium enterprises around the world buy printing machines, which can cost several million dollars apiece, to serve the needs of their local customers. Due to variability in customer demand, the majority of these machines are grossly underutilized. Globally, print capacity exceeds demand by a factor of six to one. Even with this large printing capacity, the process remains inefficient and costly for customers. Large multinational retailers often print the entirety of their catalog supply with a centralized printing company and then ship these catalogs to their stores around the world. However, this process is inefficient due to high shipping costs, the inability to produce localized content (e.g., catalogs in a local language), and oversupply of printed material, which gets outdated quickly and is often discarded by the local stores.

Gelato, a startup based in Norway, decided to reinvent the printing industry to solve the problems of buyers and suppliers by building a platform that connects the two parties. Customers can upload their print design on Gelato’s cloud and order any quantity of the print material to be delivered anywhere in the forty countries where Gelato currently operates. Gelato matches this demand with the unused capacity of a supplier who is closest to the local delivery address. Since its inception in 2007, Gelato has grown rapidly and is cash-flow positive. Henrik Müller-Hansen, its CEO and cofounder, has aspirations to make Gelato into a multibillion-dollar company and, in the process, transform the centuries-old printing industry.

The Platform Revolution

Gelato is one of the many companies that are building platform-based businesses to transform established industries. In recent years we have witnessed the explosion of platform businesses that connect multiple parties such as buyers and sellers (e.g., eBay), or consumers and developers (e.g., Apple’s app store). Alibaba, Amazon’s marketplace, and eBay are all e-commerce platforms. Uber has revolutionized transportation by connecting drivers with riders on its platform. Airbnb built a platform to connect homeowners with travelers who need a place to stay. Upwork connects businesses with freelancers who can perform a variety of tasks.

Why is there a sudden explosion of platforms? To understand this it is useful to go back to 1776 when Adam Smith published his classic book The Wealth of Nations. The main thesis of Smith’s economic theory is that people act in their own self-interest and that in a free market an invisible hand allocates resources efficiently. If the free market is supposed to efficiently match workers with tasks, then why do firms exist? Why don’t we sell our skills in an open market instead of working for a company? In 1937, the economist Ronald Coase published a paper titled “The Nature of the Firm” to address this very question, a paper for which, in 1991, he received the Nobel Prize in economics. Coase argued that firms exist because of transaction costs. Simply put, it would be too difficult and costly for you to get up every morning and find a day’s work that was suitable to your skill.

Today digital technology has dramatically reduced the transaction cost of finding and selling goods and services. Two decades ago it would have been hard for you to sell your old bike except in your immediate locale through a garage sale, but now internet-based platforms such as eBay allow buyers and sellers around the world to connect with one another, thereby reducing the transaction cost of selling (and buying) goods beyond your immediate locale. Similarly, platforms like Upwork reduce the transaction cost of freelancers seeking suitable work that doesn’t require working for a company permanently.

Advantages and Challenges of a Platform

Platforms provide unique advantages compared with traditional business models.

- Greater Access to Sellers. The platform model works best in fragmented markets by aggregating dispersed supply and demand. This aggregation provides tremendous reach to suppliers, on a scale they could not imagine before. Jack Ma, the founder of Alibaba, recognized this opportunity in China when he said, “There are more than 40 million small businesses in China. Many of them operate in fragmented markets, with limited access to communication channels and information sources that would help them market and promote their products.”2 This insight led to the creation of Alibaba, a platform that sells goods from millions of third-party suppliers.

- Better Value to Consumers. Platforms also provide better value to consumers by offering them convenience and a greater variety of products and services at competitive prices, since a large number of suppliers compete for a buyer’s business. A 2015 study of European consumers found that almost all of them (97 percent of internet users) derive significant value from online platforms.3 Through its platform Gelato’s customers have seen a 90 percent reduction in transportation costs and a 50 percent reduction in paper waste.4

- Market Growth. By lowering transaction costs, platforms open up whole new areas of supply and demand. Uber created a completely new supply of cars and drivers by reducing the transaction cost of finding riders, and riders’ demand grew because of an increase in supply that made it easy to find a car on demand. Platforms also break down geographical barriers, greatly expanding the physical reach of both buyers and suppliers.

- Asset-light. Platform businesses facilitate the transactions of third-party players without owning many assets. As indicated in chapter 2, an asset-light model lowers the capital requirement and allows for a business to rapidly expand. Gelato connects $300 million in print assets without owning a single printing machine.

- Scalability. In addition to having a low capital requirement, platform businesses scale quickly due to network effects—more buyers on a platform attract more sellers, and more sellers in turn draw in more buyers. This creates a virtuous circle that often leads to a winner-take-all situation. Not surprisingly we see companies like Facebook, Uber, Alibaba, and Airbnb dominate and effectively become the standard in their markets.

- Innovation. By attracting large numbers of sellers and developers, a platform creates an implicit incentive for them to innovate and improve their product and service to remain competitive. Research on crowdsourcing and open innovation also shows that—in contrast to dynamics within a company-led team—innovation is more likely to thrive in an environment where thousands or even millions of sellers or software developers are creating new products and services on a platform. Platforms also provide a natural lab for these sellers to test new ideas and services.

In spite of these advantages, a company should carefully consider some the challenges it may encounter as it moves to a platform model. Flipkart, an e-commerce player in India valued at over $15 billion, illustrates these challenges.

In 2015, Flipkart decided to aggressively move from an inventory-based model to a marketplace model where it would allow third-party sellers to sell directly to consumers without Flipkart having to warehouse any inventory. The company founders, Sachin and Binny Bansal, took inspiration from Alibaba, Uber, and Airbnb, who demonstrated the efficacy of this asset-light model.5 Uber does not own any cars, Airbnb does not own any hotels, and Alibaba started without owning any products. This lowers the fixed costs and capital investment of these companies and improves their return on assets, and by extension the return on equity. Low capital requirement also allows a company to rapidly scale.

However, not all companies have followed a similar model. Zappos, an online shoe company acquired by Amazon, started as a marketplace in 1999 but by the mid-2000s it had turned into a pure reseller by stocking its inventory and taking full control of transactions. Amazon uses a hybrid model in which third-party sellers account for about half of its revenues. The remaining half comes from the sale of inventory managed and stocked by Amazon itself.

Why do Zappos and Amazon want to hold inventory if a platform offers scale and growth with limited capital investment? An inventory-based model allows for greater control over product quality, delivery, and availability and over customer service. This in turn leads to better customer experience and enhanced customer loyalty. While a rating system for third-party sellers can help weed out bad sellers, this system is far from perfect. Alibaba started without owning any warehouses and operated as a pure platform relying on third-party providers for logistics. However, in 2013, Alibaba launched its logistics arm, Cainiao, with a planned investment of $16 billion in the following five to eight years.6

With this investment, Alibaba wanted to take better control of its logistics, for faster delivery of products, and to avoid the problem of fake and counterfeit products sold by third-party sellers, which had drawn the ire of companies selling branded products.

In summary, a platform offers scale with low capital investment, but it comes with limited control that may lead to poor customer experience. Companies that rely heavily on their platform spend enormous amounts of time and effort managing customer experience.

From Products to Platform

When we think of platforms, we typically think of marketplaces or services like eBay or Uber, which connect buyers and sellers. Can companies that manufacture and sell products become platforms? In January 2014, Google paid $3.2 billion to buy Nest, a smart thermostat that learns what temperature you like and automatically adjusts temperature in your house to save energy. But Google wasn’t buying thermostats, instead, it envisioned Nest becoming a platform on which many applications could be developed for the connected home. In an effort to attract developers to its platform, Nest launched the “Works with Nest” program, and within a year the company had over 10,000 developers creating new applications. Nest also attracted large companies that wanted to be a part of the connected home. Nest, the platform, now works with Philips’ smart LED bulbs, Whirlpool’s washing machines, and Xfinity Home security systems, among other products and services. In the battle to own the home, Amazon created its own device, Echo (a smart speaker that is connected to a voice-controlled personal assistant service called Alexa), and Google responded by launching Google Home. Tesla’s car is nothing but software on wheels and could become a platform for entertainment, payment, and much more.

As devices become embedded with sensors, their value is less in the hardware itself and more in the interconnectedness of that hardware. In the connected world, the battle is no longer fought among products. Instead, competitive advantage comes from building a platform that has an ecosystem around it. However, the journey from product to platform is not always easy or quick, and often a company’s business model evolves over time to reach this stage. The digital journey of GE illustrates this transition.

GE’s Digital Journey and the Birth of the Predix Platform

Founded in 1892 in Schenectady, New York, GE is an industrial giant that operates in 180 countries, employs over 300,000 people, and generates more than $130 billion in revenue. The company manufactures complex industrial products such as wind turbines, jet engines, and locomotives. For over a hundred years, its strength and competitive advantage had been in its engineering, superior product design, and manufacturing.

In 2010, two facts became clear to Jeff Immelt, GE’s CEO at the time. First, industrial productivity was expected to drop to less than 1 percent in the next decade, compared with 4 percent during the last decade.

Second, future improvements in productivity would come from software and analytics instead of physical improvements in products. Bill Ruh, CEO of GE Digital, emphasized this aspect, “Uber and Airbnb own no assets, yet they are valued more than auto manufacturers and hotels. It was clear to us that the future is not about who owns the assets but who makes those assets more productive.”7

Given this reality, GE was concerned about a new set of competitors. What if IBM, Google, or Amazon used their software and analytics capabilities to make GE assets more valuable to GE customers? Would they become the industrial version of Uber and extract all the value? GE could insert sensors into its jet engines and wind turbines to collect data, but could it be more competitive in software and analytics than IBM or Google?

After much deliberation, GE management came up with the idea of “digital twin,” a combination of the physical model of, say, a jet engine that allowed GE’s engineers to forecast the failure probabilities of various components over time; and the real-time operational data from the sensors in an engine in use that could complement the theoretical model of the engineers to more accurately predict failure and offer predictive maintenance. This deep knowledge not just of data and analytics but of physics and engineering gave GE capabilities that IBM or Google could not match effectively.

The question then became how digital twin and improved software capabilities should change GE’s business model. GE could develop software and give it away for free with the capital equipment sales. This would be consistent with GE’s traditional hardware and product focus and would require the least change to its business model. Alternatively, GE could license the software as a separate product to generate additional revenue. A third option would be to deeply integrate GE’s software and analytical capabilities with customers’ own data in order to offer new outcome-based services. That last option could eventually lead to building a platform, but it would require significant investments and new capabilities.

Jeff Immelt decided to transform GE into an industrial digital company, and in 2011 he created GE Software, located in San Ramon, California, and installed Bill Ruh as its head. As with most digital transformations, this one evolved over time. During the transition, which was marked by three distinct phases, GE Software changed from a center of excellence to a stand-alone business unit, GE Digital, with over 30,000 people.

Phase 1: GE for GE

GE started its digital journey to improve the productivity of its own assets. Having been in business for more than a century, GE had a very large installed base that provided it a unique competitive advantage when launching this initiative. The goal was not simply to collect data for the sake of data but to improve the productivity of assets. GE’s analysis showed that a 1 percent efficiency gain could lead to billions of incremental dollars for its customers. Digital twin and asset-performance-management (APM) tools allowed GE to do predictive maintenance, minimize downtime, and optimize assets, all of which saved billions of dollars for its clients.

Phase 2: GE for Customers

As the company developed in-house software and analytical capabilities to improve the productivity of its assets, it decided to invite outside developers to build apps for its cloud-based system, Predix, and also share these apps with GE customers. Soon the company’s relationship with its customers transformed from selling products to selling outcome-based services. One example of this is the GE Renewable Energy Group, which has an installed base of 33,000 wind turbines around the world, almost one-third of all turbines. For customers who bought GE turbines, the company started an outcome-based system called “PowerUp.” As GE got data from sensors in the turbines, it could make real-time changes—for example, changing the pitch of a turbine blade if it got icy in cold weather. These changes have led to as much as a 5 percent increase in annual energy production for some of GE’s clients, which translates into a 20 percent increase in their profits. This productivity improvement is not limited to optimizing each turbine individually. The location of turbines and the prevailing direction of wind on a farm may warrant a farm-level optimization that is suboptimal for an individual turbine but beneficial for the farm a whole.

A strong relationship with its customers is also helping GE develop new services. For example, wind farms, who are GE’s customers, are at nature’s mercy for the amount of energy they can generate on a given day or in a given week. However, customers of wind farms—governments, utility companies—expect the farms to deliver a certain amount of energy. If a farm falls short, it has to buy energy in the spot market, which can be very expensive. Using weather forecasts and historical data from its turbines, GE Renewable can now forecast farms’ power production seven days ahead, allowing them to better manage their power-generation business.

Phase 3: GE for the World

In the next phase GE decided to open up its Predix platform to non-GE customers. Bill Ruh explained GE’s decision to become the platform for industrial products: “There are lots of platforms optimized for consumer Internet applications and consumer devices. There are some aimed at the enterprise world, optimizing the IT environment. We saw nothing in the industrial world.”8 Customers such as Pitney Bowes and Schindler started using Predix and its analytical capabilities for their own clients. Roger Pilc, executive vice president and chief innovation officer of Pitney Bowes, explained his company’s decision to use the Predix platform:

We placed value with GE because they not only built the data and analytics platform, but also because of the journey they’ve been on for the last several years. They’ve been using data from their own machines, doing the data analytics and then ultimately evolving their own services organization in the exact same way as us. That was an important element to us. We speak regularly not just about the technology and the applications, but also about this digital-industrial transformation.9

In his 2015 letter to shareholders, Jeff Immelt highlighted the impact of GE’s digital journey: “This year we will generate $500 million of productivity by applying data and analytics inside GE. The revenue for our analytical applications and software is $5 billion and growing 20% annually . . . We are creating a $15 billion software and digital company inside of GE built on agile practices and new business models.”10

Can Banks Become Platforms?

In 2016, Goldman Sachs shocked the financial-services industry by opening up its structured-notes business to competitors.11 Structured notes, designed to help clients create highly customized risk-return products, had been popular in Europe but had seen limited penetration in the United States due to a highly fragmented market of broker-dealers and a lack of education among them. Goldman Sachs entered this market by creating its own product, called Structured Investment Marketplace and Online Network (SIMON), which was built on the company’s “Marquee” platform.

The evolution of Goldman Sachs’s digital journey followed a pattern remarkably similar to that of GE. In a process championed by Goldman’s chief information officer at the time, R. Martin Chavez (who is now the company’s CFO), Goldman first embarked on creating internal efficiencies across business units. Next, it opened up its Marquee platform to clients so that they could use Goldman’s proprietary database and tools to analyze risk or construct their portfolio. One of the first tools available to clients through application-program-interface (API) integration was SecDB, a powerful database that calculated 23 billion prices across 2.8 million positions daily across 50,000 market scenarios. Giving clients access to SecDB, which had long been considered Goldman’s “secret sauce,” puzzled the market. However, by making these tools available to clients and by tightly integrating Goldman’s systems with those of its clients, Goldman hoped to create stickiness and a unique competitive advantage.

SIMON started as an application on Marquee, and in the beginning Goldman sold only its own products on SIMON. However, the company soon realized the benefit of opening up its platform to competitors. Paul Russo, the global co-chief operating officer of the equities franchise, explained this decision: “We realized that growth of the single dealer model had reached capacity. To continue to grow we need to add more issuers. Clients also like competition. Having multiple issuers allows clients to mix and match credit risk against payoffs effectively.”

Opening the platform to competition effectively increased the size of the pie, and Goldman Sachs took a cut from the sale of competitors’ products on its platform. By 2016, Goldman’s structured-note business had grown to become the second-largest in the United States.

Banks have traditionally been very product focused, and it may be useful for them to rethink their business model. Francisco Gonzalez, the group executive chairman of BBVA, the leading bank of Spain, has argued that banks will have a hard time competing on products as those products become less and less differentiated. Instead, an incumbent bank may want to consider the benefits of creating a platform on which it provides its large customer base access to its own and competitors’ products. In the digital age customers are likely to compare products anyway, and by providing a central place for them to do so, the bank would benefit from getting a portion of revenue if a competing product were sold on its platform.

Developing a Platform Business

The GE and Goldman Sachs cases illustrate some of the issues in transforming a product-focused company into a platform-based company. The goal of a product-focused company is to develop the best product and maximize its sales and profits while ensuring competitive advantage through tight control of proprietary knowledge. In contrast, a platform business creates value not simply by selling products or services but by enabling transactions and by creating an entire ecosystem. Therefore, a platform-based business attempts to build a network of third-party players who can develop complementary services; designs its systems through APIs and tools to facilitate transactions; often supports an open and shared system instead of a closed, proprietary one; and develops mechanisms to manage partners who may have conflicting interests. In the next part of this chapter we delve deeper into some of the major challenges a company faces in building a platform-based business.

Building Critical Mass

Platforms enable transactions between multiple parties (e.g., buyers and sellers), and companies often struggle on how to jump-start the process—should they first focus on buyers (demand side of the platform) or the sellers (supply side of the platform)? Here are some guidelines:

- Develop Compelling Applications or Services Yourself. To jump-start the process, a firm needs to create a supply of good products and services first—after all, without anything to sell, it will be hard to attract potential buyers to the platform. In the early stages, when third-party sellers may be reluctant to join the platform, the firm has to build its own applications or create its own supply. Companies such as Microsoft and Sony—makers, respectively, of the Xbox and PlayStation gaming consoles—rely on the variety and scale of games produced by third-party developers. However, to attract these third-party developers to their platforms, they first developed a handful of engaging games themselves that attracted users, which in turn encouraged third-party developers to join these platforms. GE developed its own applications for its customers before opening the Predix platform for outside developers and non-GE customers. Apple showed the power of its platform by building iTunes. Soon after acquiring Nest, Google acquired Dropcam, maker of a Wi-Fi enabled security camera that could be connected to Nest. This showed the power of the platform and attracted potential developers. Instead of starting with UberX or UberPOOL, in which users drive their own cars, Uber started its service with black cars driven by professional drivers. To jump-start its service, Airbnb used professional photographers to take pictures of apartments, which encouraged users to follow suit.12

- Start with a Focus. Since platforms typically have strong network effects leading to winner-take-all markets, it is tempting to scale quickly by getting into multiple applications fast. However, at the early stage it is critical to develop a compelling use case and powerful customer experience by focusing on a small market to have a proof of concept. Uber started in January 2010 with a test in New York City and later launched the service in San Francisco in May 2010. In the beginning, as mentioned, Uber used black cars driven by professional drivers. While clearly not scalable in the future, this approach was designed to attract enough users to jump-start the process and to ensure great customer experience, which eventually created strong word of mouth. Travis Kalanick, founder of Uber, relied on users’ word of mouth for early growth of the company: “I’m talking old school word of mouth, you know at the water cooler in the office, at a restaurant when you’re paying the bill, at a party with friends—‘Who’s Ubering home?’ 95% of all our riders have heard about Uber from other Uber riders.”13 It took Uber almost a year to test and refine its service in San Francisco before going to a new city in California, Palo Alto. In the realm of social media, even though it faced the dominant incumbent MySpace, Facebook started by focusing only on Harvard students, gradually expanding to more US and international students, before ultimately opening up its platform to everyone. Reflecting on the early growth stage of Flipkart, an Indian e-commerce company that started by selling books, cofounder Sachin Bansal noted, “We were sure from the beginning that we would enter more categories. Initially we thought we would launch the next category in a year. It took us three years to move beyond books.”14

- Subsidize One Side of the Platform. When a company sells a product, it needs to charge each buyer in order to make money. In contrast, a platform connects multiple parties, and the company can afford to subsidize one side to stimulate demand while making profits on the other side. Research shows that the best approach is to subsidize the side of the platform that contributes more to demand for the other side.15 When Adobe introduced Acrobat software, it initially charged $35 to $50 for Acrobat Reader software and $195 for the software to create PDFs. Later, to encourage adoption, it changed its approach and offered the Acrobat Reader for free.16

- Build a Freemium Model. Platform businesses have strong network effects that can create a virtuous circle. To encourage adoption and create this network effect, many companies are beginning to adopt a freemium model in which a basic version of the product is free for customers. Dropbox, Spotify, Pandora, and The New York Times are examples of companies using such a strategy. A freemium model has several benefits: For digital products, the marginal cost of an additional customer is close to zero. A free basic product encourages adoption and creates a large customer base of users that generates strong network effects. And over time, the use of a basic product encourages customers to upgrade to paid premium products. However, designing freemium products and their pricing is a complex issue that requires careful consideration.17

Facilitating Access and Transactions

The primary function of a platform is to enable and facilitate transactions. Recall that a platform business works by aggregating demand from a fragmented market and by reducing transaction costs. Therefore a platform owner needs to build tools and services to provide easy access to third-party players on its platform, use algorithms to match players on multiple sides of the platform, and offer additional services that make it easy for them to do business. For example, software platforms offer APIs to help developers build applications. Facebook helped its users to find friends, which increased Facebook’s value to users. Amazon offers warehousing and shipping services to its marketplace sellers, which makes it easy for the sellers to do business.

Choosing between Open and Closed Systems

One of the main challenges for a company building a platform business is the choice between an open, or shared, system and a closed, or proprietary, system. An open system generally attracts a larger number of independent players to the platform, which fosters greater innovation and variety, builds more complementary products, lowers prices due to competition among players, and creates a larger market. In contrast, a company has more control with a closed system, which allows the company to create better integration and coordination across various products and services offered on its platform, which in turn creates a superior customer experience. A closed system also allows the platform host to capture a larger share of the pie.

Google’s Android is an open system, whereas Apple tightly controls its iOS and carefully screens apps before approving them for its system. As a result of these choices, Android enjoys a larger market share while Apple provides a superior customer experience. In the second quarter of 2017, Android had 87.7 percent of global market share compared with 12.1 percent for Apple’s iOS.18 In the credit- and debit-card market, Mastercard and Visa have open systems in which they partner with banks that ultimately issue cards to customers and acquire merchants. In contrast, American Express manages a closed system in which it acts as an issuing and acquiring bank as well as a processor of transactions. In 2015, Visa accounted for 56 percent of all global card transactions, followed by Mastercard, with its share of 26 percent. American Express had a mere 3.2 percent share of all such transactions.19

For its in-car software, BMW opted to build an open system. Dr. Michael Wuertenberger, the managing director of BMW’s Car IT, explained:

We definitely would like to have an open system. It will not be simply an Apple or a Google system inside the car. BMW has to work with both of them. Two years ago, we launched the first open-source in-car “infotainment” system that is Linux-based and can integrate with both Apple’s and Google’s software. We would like to share that system with other car makers to place into their vehicles. Openness is good.20

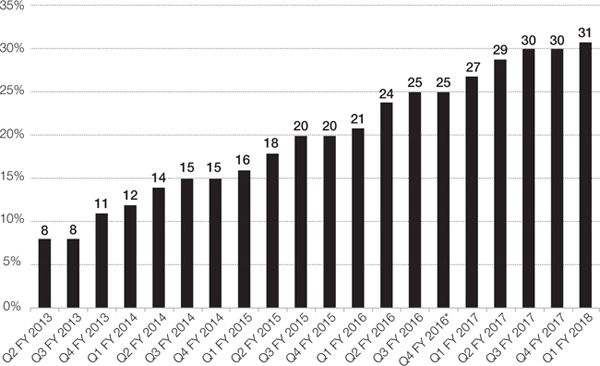

The choice of an open or a closed system is not usually black and white, as there are various parts of the platform that can be kept open or proprietary.21 However, in general, an open system creates a larger market and a closed system creates a better customer experience. So the choice of an open or a closed platform depends on the goal and strategy of the company. For example, Google, Apple, and Samsung are creating open mobile-payment systems to build a large market. However, Starbucks created a very successful closed system for mobile payment that works only at Starbucks stores. Part of its success stems from enhancing customer experience by providing a compelling value proposition to its frequent visitors, who can order and pay ahead for their coffee, before they walk into a Starbucks store. (Figure 3-1 shows the growth of transactions on the Starbucks mobile-payment platform.)

Starbucks’s mobile transactions as a percentage of total transactions, 2013–2018

Source: Company reports and BI Intelligence.

Note: Q4 FY 2016 excludes week 53. Starbucks’s fiscal year ends on the Sunday closest to September 30.

Managing Partners in the Ecosystem

Platforms develop an ecosystem of partners who provide complementary products and services. The word ecosystem was first coined in 1930 by British botanist Roy Clapham, and later popularized by ecologist Arthur Tansley to describe a community of organisms who, in conjunction with their environment, interact as a system.22 These organisms share resources, compete and collaborate, and co-evolve. This idea was adapted for business by the writer James Moore in a 1993 Harvard Business Review article:

To extend a systematic approach to strategy, I suggest that a company be viewed not as a member of a single industry but as part of a business ecosystem that crosses a variety of industries. In a business ecosystem, companies co-evolve capabilities around a new innovation; they work cooperatively and competitively to support new products, satisfy customer needs, and eventually incorporate the next round of innovations.23

Today, business ecosystems have become even more important as technologies are increasingly blurring industry boundaries. “A vibrant ecosystem can enable activities, assets, and capabilities to be flexible and constantly reconfigured in response to the unexpected,” argue the writers Peter James Williamson and Arnoud De Meyer. “Both the demands of consumers and the technologies available to satisfy them have changed dramatically. Today’s world requires the capacity to deliver complex solutions to customers, built by bringing together specialized capabilities scattered in diverse organizations around the world.”24 While the nineteenth and twentieth centuries focused on efficiency and economies of scale, the current era requires coordination across a wide variety of firms to provide complex and dynamic solutions to customers.

Deloitte, a consulting firm, defines business ecosystems as “dynamic and co-evolving communities of diverse actors who create and capture new value through both collaboration and competition.”25 It is this unique aspect of collaboration and competition among firms that makes ecosystems unique and complex to manage.

Firms have varying degrees of control in this environment. For example, Apple largely controls its iOS. Individual developers have limited power. In contrast, Apple had significantly less power when it introduced Apple Pay in partnership with banks and merchants and had to carefully manage its relationship with these partners. In this complex environment, a company must understand the motivations of its partners in order to manage the ecosystem effectively. The launch of Apple Pay illustrates this complexity.

In September 2014, Tim Cook, Apple’s CEO, announced the launch of Apple Pay and said, “Our vision is to replace this [wallet], and we are going to start with payments.”26 Apple did not blow up the existing payment system. Instead, it decided to work within the current payments ecosystem. Jennifer Bailey, vice president of Apple Pay, explained this decision:

We want to support what people already use and love. Consumers are already comfortable using their credit and debit cards that are supported by the majority of merchants and banks. Banks are good at what they do: they are good at credit, branding, customer service and conducting payments. Apple’s role was simply to bring together the hardware, software and services to create the experience on the phone.27

This choice led Apple to work with its partners: the banks, the merchants, and the payment networks (Mastercard, Visa, American Express). While each of these partners collaborated with Apple, they were also considering launching their own mobile-payment systems. Soon after the launch of Apple Pay, some of the largest US merchants launched Merchant Customer Exchange (MCX), Chase created its own mobile-payment system called Chase Pay, Mastercard started Masterpass, and Visa introduced Visa Checkout as its online and mobile-payment system. In this collaboration the key battle is for the control of customers. Banks don’t want Apple to own the user interface and effectively become a utility in the background, yet they can’t ignore Apple either, because of Apple’s strong affinity among consumers.

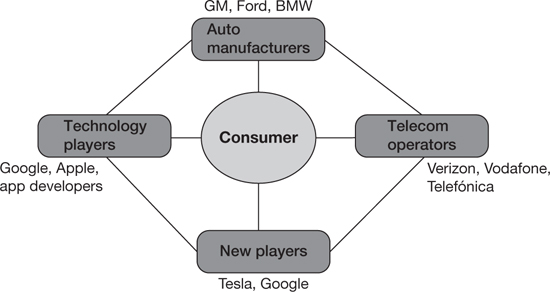

A similar battle for the customer is brewing in the automotive ecosystem, and the participants include incumbent auto manufacturers like GM, Ford, and BMW; new players like Tesla; technology companies like Apple and Google, which are developing in-car technologies such as CarPlay; and telecommunication companies like Verizon, Vodaphone, and Telefónica, which are vying for a position in the era of connected cars (see figure 3-2).

Reflecting on Mercedes-Benz’s strategy, Wilko Stark, vice president of Daimler’s group strategy, product strategy, and product planning, noted:

The company that has access to the customer interface is the one who possesses the opportunity to do one-to-one marketing and personalized services for each customer through the data that is collected. We already know a lot about each of our customers, where they drive, what is their location—we want to offer them personalized services as well.28

There is no easy solution for managing these complex partnerships. Players need to understand the motivations of their partners and carefully balance their own interests with those geared to the success of the overall ecosystem. For instance, even though Apple and Google launched competing mobile-payment systems, they have very different motivations. Apple’s business is largely driven by hardware, so its motivation is primarily to create complementary services for the iPhone, while Google’s business depends on advertising and data. Not surprisingly, in launching Apple Pay, Apple decided that banks and merchants, not Apple, would own the data. In contrast, Google needs mobile-payment data to close the loop from search to purchase to show the effectiveness of its advertising.

Governance

In 2016, Facebook was blamed for influencing the US presidential election by not identifying fake news stories on its site, many of which went viral. Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook’s founder and CEO, described these allegations as crazy. After all, Facebook is an open social platform where people are free to express their opinions without any effort by Facebook to tilt the conversations one way or the other. In a November 12, 2016, Facebook post, Zuckerberg said,

Of all the content on Facebook, more than 99% of what people see is authentic. Only a very small amount is fake news and hoaxes. The hoaxes that do exist are not limited to one partisan view, or even to politics. Overall, this makes it extremely unlikely hoaxes changed the outcome of this election in one direction or the other.29

However, this did not satisfy the critics, who argued that Facebook has a large influence on social conversations and therefore has a responsibility, like a media company, to separate the truth from hoaxes. Using technology and users’ input, Facebook is now trying to identify and curb fake news. In early 2018, Facebook again faced strong criticism for failing to protect consumer data as the news broke that a UK-based company, Cambridge Analytica, used consumers’ Facebook data to target political ads to influence the 2016 US presidential elections.

To avoid market failures, platform owners need a governance system to create rules by which various players operate within its ecosystem—whether it is to limit fake news and pornography on Facebook while still encouraging free and open conversations or to delist sellers with bad customer service on Amazon’s marketplace while still trying to increase the number of sellers. Insights from diverse corners—such as corporate governance in finance and accounting, laws governing interactions among nation-states, and research on the proper function of the kidney exchange—can provide guidance on how to govern and manage a platform business.

Based on his research on the medical labor market and the kidney exchange, Alvin Roth, winner of the 2012 Nobel Prize in economics, said, “Traditional economics views markets as simply the confluence of supply and demand. A new field of economics, known as ‘market design,’ recognizes that well-functioning markets depend on detailed rules.”30 He went on to explain three things that are needed for markets to function properly: Markets or platforms need to provide thickness, which brings large numbers of buyers and sellers together. They need to make it safe for participants to reveal and act on confidential information they may hold. And they need to manage congestion, or competition and complexity, that arises from thickness.

In conclusion, platforms provide a new way of conducting business that warrants an outside-in perspective, meaning that firms need to open up their systems in order to collaborate and partner with many players, some of whom may even be their competitors. And this requires new skills and capabilities to manage and govern a platform.