Chapter 7

Acquiring Customers

Growth is a key priority for every business, and acquiring new customers is a major driver of growth. Digital- and social-marketing tools provide new and innovative ways to spur this growth. However, acquisition costs and profitability vary widely across customers and channels, so in this chapter we will focus on two fundamental questions: Which customers should you acquire, and how should you go about acquiring them?

Which Customers to Acquire

In 2016, Chase introduced its new Sapphire Reserve Card with a very attractive offer: a signing bonus of 100,000 points, $300 in travel credit, triple points earned on all travel and dining expenses, and a value of 1.5 times applied to points redeemed on travel. In spite of its hefty $450 annual fee, this offer generated so much enthusiasm among consumers that within a month of the card’s introduction Chase ran out of the metal from which the card was made. Chase management said that the company exceeded its annual target of customers in less than two weeks.1

A great success? Perhaps. This generous offer was expensive for the bank. In December 2016, Jamie Dimon, CEO of JP Morgan Chase, said that the new Sapphire Reserve Card would reduce the bank’s fourth-quarter profits by as much as $300 million. According to Sanford C. Bernstein & Co., it would take the bank five and a half years to break even on its promotional investment in the card.2

With the card’s high annual fee, Chase was clearly aiming for the affluent customers who have historically been the prime target of the American Express Platinum card. Yet surprisingly, the majority of people who signed up for the Sapphire card were millennials. Chase management justified the acquisition of these customers: “That is significant because millennials make up the majority of our new deposit accounts today, and their wealth is expected to grow at the fastest rate of all generations over the next 15 years.” However, whether or not acquiring these customers was the right decision for Chase depends on how many of these new customers will stay with Chase after the first year, especially when competing firms are also making attractive offers to them. In a note to their clients, Bernstein analysts said, “Lucrative sign-up bonuses give an issuer an opportunity to acquire a large number of customers in a short period of time, though we question whether the type of consumer this attracts leads to a less profitable card product in the long run.”3

To address analysts’ concern, in February 2018, Chase management provided an update on the new Sapphire Reserve customers. It stated that the average income of new cardholders is $180,000; their annual spend on the card is $39,000; and their retention rate is over 90 percent. Chase is also running a pilot in 2018 to convert many of its Sapphire card customers into Chase Private Client and mortgage customers.4

Customer Lifetime Value (CLV)

The Chase example illustrates that the number of acquired customers or their acquisition cost do not provide sufficient information to evaluate a customer acquisition strategy. It is critical to know customer spend and their retention rate to estimate their long-term value. Yet most companies track a host of short-term metrics to assess their marketing campaigns—impressions, number of clicks, click-through rate (CTR), conversion rate (from clicks to purchase), and customer acquisition cost (CAC). Of all these, CAC often becomes the key metric for managers when evaluating the effectiveness of their marketing efforts and when allocating budgets. A media channel that is less expensive in acquiring new customers is often preferred over an expensive channel. However, CAC ignores how much customers spend with the firm and their retention rate, both of which determine the long-term profitability of customers, also called customer lifetime value (CLV).

Gaming companies lose a majority of their customers after the first day of app installation. On average, 80 percent of mobile app users either uninstall or stop using an app within ninety days of downloading it.5 Put differently, firms have a leaky bucket—they keep adding new customers at the top but lose 80 percent of them every three months. Retention rates also vary by media channel, so a cheaper way to acquire customers may not necessarily be the most profitable in the medium to long run. In June 2017, Blue Apron, a meal-kit maker, stumbled in its initial public offering as analysts recognized that almost 60 percent of its customers left the service after six months.6

The 200–20 Rule

All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others.

—Animal Farm, by George Orwell

According to the familiar 80–20 rule, 20 percent of the customers provide 80 percent of the revenue. However, research shows that if we focus on profitability instead of revenues, the rule would be 200–20, where 20 percent of the customers provide almost 200 percent of the profit! How is that possible? Because the remaining 80 percent of customers actually destroy profitability. In other words, a company’s profits would soar if it were to jettison the bottom 80 percent of its customers. Of course, some of these unprofitable customers may be important for other, strategic reasons, but this analysis forces management to articulate the reasons for retaining these unprofitable customers.

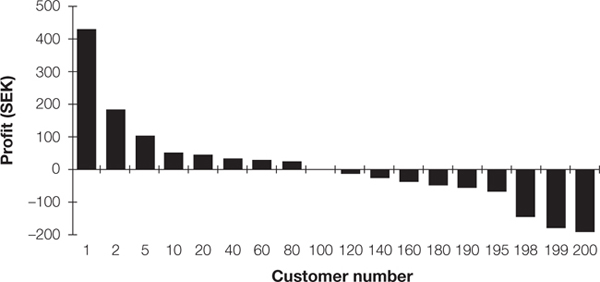

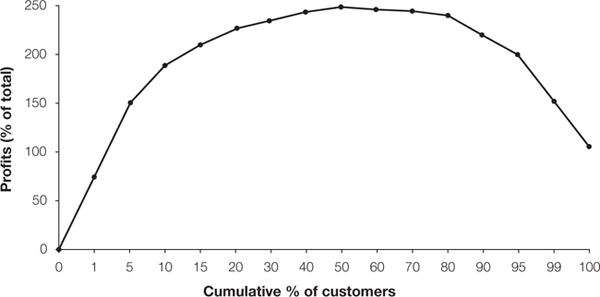

Figure 7-1 shows the customers of Kanthal, a Swedish manufacturer of industrial heating technology, ranked according to their profitability. Only the top 80 customers out of 200 are profitable for the firm. Figure 7-2 shows Kanthal’s profit as we add customers starting with the most profitable to the most unprofitable. The most profitable 5 percent of Kanthal’s customers generated 150 percent of the profits. Only 40 percent of its customers were profitable at all, and that group, taken together, created 250 percent of the firm’s profits. This figure also shows that the bottom 10 percent of the customers lost about 120 percent of the profits.

FIGURE 7-1

Profitability of Kanthal’s customers ranked from most to least profitable

Source: Robert S. Kaplan, “Kanthal (A),” Case 190-002 (Boston: Harvard Business School, 1989, revised 2001).

FIGURE 7-2

Cumulative profitability of Kanthal’s customers

Source: Robert S. Kaplan, “Kanthal (A),” Case 190–002 (Boston: Harvard Business School, 1989, revised 2001).

The graph in figure 7-2 is often called the “whale curve” because of its whale-like shape, and it shows that 20 percent of Kanthal’s customers account for more than 200 percent of its profits. This is a common finding among many companies and illustrates the 200–20 rule of customer profitability. In 2008, Elkay Plumbing, a US manufacturer of sinks, faucets, and fountains for residential and commercial customers, found a similar pattern—the top 1 percent of its customers accounted for 100 percent of its profits, and the most profitable 20 percent of its customers generated 175 percent of its profits.7

These findings underscore the importance of acquiring and retaining the right customers, those who are likely to be profitable in the long run. It also suggests that simple metrics like total number of customers or overall market share—metrics used by a majority of companies as measures of success—may be misleading. A company with a large market share may be saddled with a significant proportion of unprofitable customers.

Implementation Challenges

Even if a firm recognizes that it should acquire customers based on their expected long-term profitability, it faces several challenges in implementing this idea. First, most companies are organized by product or business units that mask huge variation in the profitability of customers within that product or business unit. Second, to measure customer profitability a firm needs to adopt activity-based costing to allocate costs to each customer or customer segment. While this task may seem tedious, advances in cost accounting, data analytics, and technology-based solutions are making it easier to achieve this objective. Third, firms need to keep track of cohorts of customers—for example, those acquired from different channels—to understand their long-term profitability and to allocate resources accordingly. Aggregating customers in a single database regardless of where they came from makes it difficult to assess the effectiveness of customer-acquisition programs.

In 2010 BBVA Compass bank, a US subsidiary of the BBVA Group of Spain, was facing a similar challenge. BBVA Compass spent almost 20 percent of its 2010 marketing budget on acquiring customers online. Management believed that the retention rate of customers who were acquired online was significantly lower than the retention rate of those acquired through branches. However, once the customers were acquired the bank kept a single customer database regardless of the channel by which customer had been acquired, which made it difficult to allocate the budget based on customer profitability.8

How to Acquire Customers

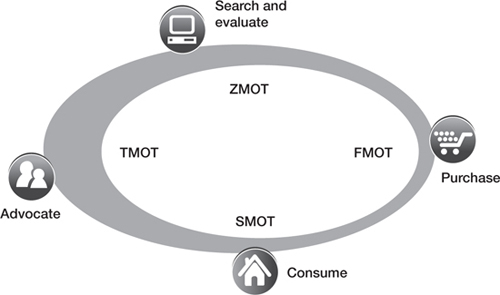

The customer-acquisition process must begin with a deep understanding of a customer’s decision journey or path to purchase. Figure 7-3 shows four key stages of the consumer journey. In 2005, A. G. Lafley, CEO of Procter & Gamble (P&G), described what he called two moments of truth: “The best brands consistently win two moments of truth. The first moment occurs at the store shelf, when a consumer decides whether to buy one brand or another. The second occurs at home, when she uses the brand—and is delighted, or isn’t.”9 Introduction of electronic scanners in stores in the 1980s and the rise of e-commerce in the last two decades have made it possible for firms to know the first moment of truth (FMOT) by tracking the sales of their products.

FIGURE 7-3

Moments of truth

Although P&G could measure sales, Lafley was concerned that the firm had no visibility into how people actually consumed and experienced products—the second moment of truth (SMOT). Recent developments in technology are making it possible to track product consumption. For example, Nestlé could introduce chips into Nespresso machines to know consumers’ coffee-consumption behavior and automatically order Nespresso capsules when consumers’ supplies got below a certain threshold. A medication event–monitoring system offers bottles with microelectronic chips that record the date and time of every bottle opening to ensure that patients adhere to their medication regime.

The battle for consumers begins long before they buy or experience a product. It starts when they open their laptops or tap on their mobile phones to search for a product. In 2011, Google coined the term “zero moment of truth” (ZMOT) to reflect the importance of this period of online searching before consumers show up in a store or make an online purchase. In a Google study 84 percent of shoppers claimed that ZMOT shaped their decisions of which brand to buy.10 Using consumers search data, Google created heat maps to visualize how and when consumers actively searched for a product. For example, a consumer’s search for a new automobile is typically most active two or three months before the actual purchase.

In addition to doing Google searches, consumers read product reviews on Amazon, hotel reviews on TripAdvisor, restaurant reviews on Yelp, and movie reviews on Rotten Tomatoes before making any decision to buy a product. The rise of social media and the increasing use of reviews by consumers have made the third moment of truth (TMOT) a critical factor. This is when loyal fans of a product become passionate advocates for it on social media and consumer-review sites.

A vital part of any successful customer-acquisition strategy is understanding these moments of truth and ensuring that a brand is well represented at each stage.

From Search to Purchase

The consumer journey from ZMOT to FMOT typically involves four stages: awareness, consideration, evaluation, and purchase. For a long time this process was believed to be linear: A consumer may be aware of eight brands of smartphones. She may consider three brands seriously, brands whose various product features and prices she evaluates more thoroughly, leading ultimately to her decision to buy a specific brand.

Recent studies by McKinsey and others have shown that consumers’ search processes may not be linear. A consumer looking to buy a car may start with only BMW and Mercedes but in the course of searching may come to include other brands in the deliberations. McKinsey has found that for automobiles consumers have, on average, 3.8 brands in their initial consideration set, but they add 2.2 additional brands during their search.11 Therefore, brands have an opportunity to influence consumers’ decisions during the search process.

A firm can provide information and influence consumers in three ways: through paid media, which would involve search engine marketing (SEM) and ads on TV, radio, newspapers and magazines; through owned media, which would include the company’s website leveraged with search engine optimization (SEO) to ensure that the site ranks high in organic online searches; and through earned media, whereby consumers learn about a product from the reviews and opinions of other consumers in social media.

In the last few years a lot has been written about the best ways to do SEM, SEO, and social media. Google and Facebook provide tools, case studies, and best practices on their sites. Instead of rehashing these suggestions (e.g., how to buy a keyword or how much to bid on it), I would focus on some of the novel research findings that may make you pause and rethink your digital marketing program.

Personalization and Retargeting

Digital technology and rich data allow firms to personalize ads to consumers based on consumers’ interests, web-browsing behavior, past purchases, and/or the context of the site they are visiting. A novel study by MIT went one step further by morphing banner ads to match consumers’ cognitive styles. For example, some consumers like to read text while others are more visual. If an advertiser can define which style any particular internet user possesses, it can enhance the potential effectiveness of an ad by matching the ad to a given consumer’s cognitive style. The MIT team surveyed a sample of consumers to learn their cognitive style and then tracked their web-browsing behavior to link the two. In practice, one can observe only consumers’ web-browsing behavior, not their cognitive styles. But by using Bayesian models and estimates from the sample consumers, the MIT team could infer consumers’ respective cognitive styles and serve personalized ads in real time. The MIT researchers tested this approach in a large-scale field experiment in which more than 100,000 consumers viewed over 450,000 banner ads on CNET.com. Morphing doubled the click-through rates of the ads. In a follow-up experiment for automobiles, the researchers further demonstrated not only that ad click-through rates improved with morphing but that brand consideration and purchase intentions also jumped significantly.12 In another follow-up study they developed an algorithm to morph the entire website in real time.13

Another commonly used approach to improve ad effectiveness is called retargeting, by which ads are shown to consumers who previously visited a firm’s site but did not buy. Several studies have shown the effectiveness of retargeting, including a recent large-scale field experiment for an online sports company. Using Google’s Display Network of two million websites, the experiment showed that retargeting increased website visits by 17 percent, transactions by 12 percent, and sales by 11 percent.14 But how specific should retargeting be? A specific or dynamic retargeting shows consumers an ad for the exact product that they searched for previously (e.g., Nike Men’s Roshe One running shoes), whereas a generic retargeting may simply show an ad for running shoes. A field experiment for an online travel company, in which almost 80,000 consumers participated, revealed that specific or dynamic retargeting surprisingly does worse that generic retargeting. The authors of the study suggest that many consumers do not have well-formed preferences, especially early in their purchase process, which makes specific targeting less effective.15

Social Media and Virality

Social media has gained a lot of attention from marketers since it allows a message to be amplified without additional cost to a firm. Experts also think that social media is more effective than traditional ads since consumers believe the opinions of other consumers.

In a 2010 interview with Fast Company, Jason Harris, the president of Mekanism, a San Francisco–based social media company, claimed, “We can engineer virality. We guarantee we can create an online campaign and make it go viral.”16 The idea of viral campaigns is seductive. Without spending much money, you create an ad or a video that is shared and viewed by millions of consumers. Marketers are quick to quantify the value of this earned media in terms of the dollars saved that would otherwise have been required to reach the same number of consumers through paid media campaigns.

But can you really engineer virality? The average YouTube video generates fewer than 10,000 views, and only a tiny fraction of YouTube videos have more than one million views.17 The notion of virality comes from epidemiology and involves a single person infected with a communicable disease spreading it to a large population. For a disease to reach epidemic proportions it needs a “reproduction rate” of greater than one, so that each person who gets the disease will, on average, spread it to more than one person. Otherwise the disease dies down quickly. A 2012 study examined the spread of millions of messages on Twitter and Yahoo and found that more than 90 percent of the messages did not diffuse at all. About 4 percent of the messages were shared only once, and less than 1 percent were shared more than seven times.18

To address the challenge of creating virality, Duncan Watts, a social scientist, and Jonah Peretti, the founder of BuzzFeed, have proposed the idea of “big seed” marketing. Unlike the typical virality campaign, which relies on seeding a message with a small number of influencers in the hope that they will spread the message like a disease, Watts and Peretti suggest seeding the message with a large number of people in the hope of amplifying it to a large audience even if the reproduction or sharing rate is less than one.19

Recognizing the difference between virality and amplification, Peretti founded BuzzFeed in 2006 with the aim of amplifying messages through native advertising. BuzzFeed learned that amplification depends not just on creating intriguing stories with humor and catchy titles but also on the medium and the authenticity of the message. Commenting on this, Peretti said,

Because our audience shares content on social networks, BuzzFeed editors have to understand how social media is used. For example, on Twitter, things happen very quickly. If Twitter is the one-hour network, Facebook is one day, and Pinterest is one week. Slow content—a recipe, for example—will work best on Pinterest. Content that is fast and newsy will do better on Twitter . . . But content that does well on Pinterest never gets tweeted, and posts that do well on Twitter find no audience on Pinterest.20

Melissa Rosenthal, formerly BuzzFeed’s director of creative services, had this advice for brand marketers: “You can trick people into clicking, but you can’t trick them into sharing. Everything that performs well is based on a real insight, something that’s actually true [about the brand].”21 David Droga, the CEO of the innovative ad agency Droga5, agrees. “It’s crude,” says Droga, “but the essence, whether we’re talking to a billion-dollar client or a startup, is: Why would anyone give a shit about what we’re making? Not, Do we think it’s cool or clever or funny or worthy? It’s, Why is this relevant?”22

Who should you seed the information with? Most marketing executives believe that social media influencers are the best bet for seeding information. However, in reality it is hard to find reliable influencers. Even using people with a large following on social media does not guarantee success. In 2009, a year before the launch of its new Fiesta, Ford recruited a hundred influential social media personalities to promote the car through blogs, videos, and photos. The list included Judson Laipply, an internet celebrity whose earlier video “The Evolution of Dance” was among YouTube’s all-time most-viewed videos, with 115 million views at that time. However, Laipply turned out to be one of the least effective agents for Ford.23

In a 2013 article in Harvard Business Review, Sinan Aral, a social network expert at MIT, elaborated on the role of influencers in social media:

In 2009 [Ashton Kutcher] became the first user to acquire 10 million followers; by early 2013 the total was 13.7 million. Kutcher would seem the very definition of a social media “influencer.” But . . . how many have ever done something because Kutcher suggested it? . . . If Kutcher is the quintessential influencer but no one does what he suggests, in what way is he influential?24

By tracking 74 million events among 1.6 million Twitter users, Eytan Bakshy, a senior scientist at Facebook, and his colleagues found that “although under some circumstances, the most influential users are also the most cost-effective, under a wide range of plausible assumptions the most cost-effective performance can be realized using ‘ordinary influencers’—individuals who exert average or even less-than-average influence.”25 Jonah Peretti of BuzzFeed agrees: “Editors can dispense with the probably fruitless exercise of predicting how, or through whom, contagious ideas will spread.”26

Collectively, these studies suggest that trying to create virality by seeding a message with a handful of social media influencers is unlikely to be successful and cost effective. Instead, it is better to seed the content with a large number of ordinary users. In fact, many social media campaigns gain traction only after they are picked up by the mainstream media.

Acquisition Through Offers

Companies in almost every industry, be it newspapers, telecom, cable, or credit cards, typically offer significant discounts to attract new customers. In the short term these offers may be effective, but what are their consequences in the long run? In a past collaboration with other researchers, I showed that while price promotions have a positive impact on brand share in the short term, they have a negative long-term impact.27 Another study quantified this negative long-term effect for newspaper subscriptions and showed that acquiring customers through a 35 percent price discount resulted in a long-term value that was about half that of non-promotionally acquired customers.28

How do these offer-based acquisition methods compare with acquisition through word of mouth or through referral programs? Two studies provide some insights. Using data from a web-hosting company, one study found that while marketing-induced customers add more short-term value, customers acquired through word of mouth add nearly twice as much long-term value to the firm.29 Another study tracked ten thousand accounts in a large German bank over a three-year period and found that customers acquired through referral programs were 18 percent more likely than others to stay with the bank, and that they generated 16 percent more in profits.30 In summary, although short-term discounts may provide a quick win in acquiring new customers, word-of-mouth and referral programs are more effective in the long run.

In practice, a company faces customers with varying price sensitivities. Some customers are more price driven and won’t buy unless they are offered discounts. To separate the price-sensitive customers from others, brick-and-mortar retailers have long followed the practice of creating search friction—placing the discounted items in the back of the store or in a separate outlet store. In contrast, online retailers try to reduce search friction and improve user experience for every customer. This results in either offering lower prices to everyone or charging relatively higher prices at the risk of losing price-sensitive consumers. In a recent study, two of my Harvard Business School colleagues wondered if an e-commerce player should deliberately create search friction for discounted products that only price-sensitive customers would hunt for. They conducted a large-scale field experiment with an online fashion and apparel retailer in the Philippines. For a group of consumers (test group), they eliminated discount markers and the ability to search products by price discounts that the company was using on its site, while the other group of customers (control group) was able to use these features. Compared with the control group, consumers in the test group bought fewer discounted products and at lower average discounts, without any impact on their conversion rate (i.e., percent of people who bought one or more items), leading to a significant increase in this online retailer’s profits. After the experiment, the company eliminated discount markers on its site and disabled product search by which item was on discount.31

These research studies show that managers should be careful in using price discounts to acquire new customers—this practice may be effective in the short run but costly in the long run. Recognizing that not all customers are equally price sensitive or equally valuable, firms may want to consider deliberately making it a little harder for consumers to find discounted items.

Beyond the Click

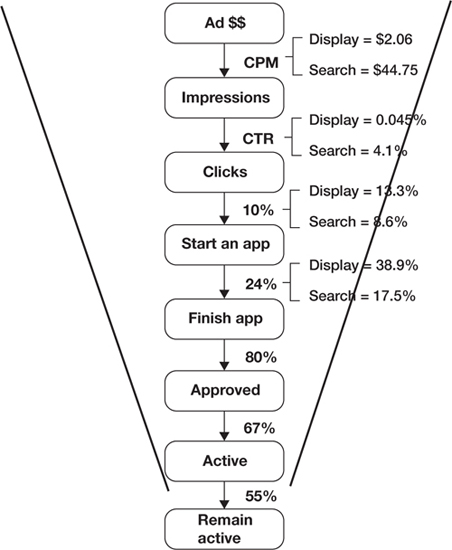

In 2010, BBVA Compass Bank spent a significant proportion of its marketing budget online to entice new customers to open checking and savings accounts with the bank. By tracking data both on the bank’s budget allocation for search and display ads and on the number of impressions, clicks, and new applications generated, we can construct an aggregate picture of the consumer journey (see figure 7-4).

Consumer journey for BBVA Compass Bank’s online customer-acquisition campaign

Source: Sunil Gupta and Joseph Davies-Gavin, “BBVA Compass: Marketing Resource Allocation,” Case 511-096 (Boston: Harvard Business School, 2011), and Teaching Note 512-051 (Boston: Harvard Business School, 2012).

The bank offered a $150 incentive for consumers to open a new account. The offer enticed many to click on the link, but when they went to the landing page, read the fine print, and learned of the conditions they had to meet (e.g., the minimum balance), only 10 percent of the people who clicked on the ad actually started the application. It is even more intriguing that only 24 percent of the people who started filling out the application for a new account actually completed it. This low rate of completion suggests that the application was either too long and complicated or was asking consumers sensitive information that made them abandon the process.

Of the users who completed the application online, about 80 percent were approved by the bank. In contrast, almost all consumers who came into bank branches were approved for a new account. In other words, the quality of customers that came through the online channel was relatively low. This was further confirmed by the fact that only two-thirds of the approved online customers actually funded the account to make it active. Finally, the retention rate of these online customers was 55 percent, compared with over 65 percent for those acquired offline.

This case highlights several important points. First, most digital marketing programs focus exclusively on improving click-through rates (CTR), even though measuring success by clicks and CTR provides only a partial picture. Second, the effective cost of acquisition should not be measured based on clicks or even completed applications. For BBVA Compass, the cost per completed online application was about $80, but if you add the $150 promotional offer and the drop-off after the click and application, the acquisition cost jumps to about $300. (Of the completed applications, 80 percent are approved and 67 percent of the approved applications are funded, leading to 80 percent times 67 percent, or 54 percent effective success rate. Therefore, the effective acquisition cost of a successful new account is $80/0.54 + $150 promotional offer, or about $300).

Third, the firm should carefully examine the reasons for the drop-offs after the click. Why do only 10 percent of those who click actually start the application? Why do only 24 percent of consumers who start the application complete it? And why do only 67 percent who are approved fund their account?

Online commerce players face a similar problem with cart abandonment at the checkout. Studies show that almost 70 percent of online shopping carts are abandoned at the checkout.32 The top three reasons include shipping and other fees, requirement to create a new account, and a long or complicated checkout process. Going beyond ad clicks to understand consumer pain points along their decision journey can help companies make their acquisition programs more effective.

Beyond Advertising

For decades marketing textbooks have talked about the four Ps (or 4Ps): product, price, place (distribution), and promotion (or advertising). Yet most discussions about digital marketing center almost exclusively around digital advertising, even though all 4Ps influence customer acquisition and retention. In the previous chapter, I discussed the importance of place in omnichannel strategies. Here I will briefly highlight how digital technology allows us to think about product and price in new ways.

For digital products with almost zero marginal cost of production and distribution, a powerful strategy is “freemium” (mentioned briefly in chapter 3), in which a basic version of a product is given away for free, and users pay only for upgrading to an advanced version. Those employing a freemium strategy would include producers of gaming apps, Adobe, the New York Times, Hulu, Dropbox, LinkedIn, Box, Splunk, Skype, Pandora, and YouTube. Freemium apps account for 95 percent of Apple App Store revenue and 98 percent of Google Play revenue.33 The freemium strategy has many advantages:

- Firms incur low or no marketing cost to acquire free customers, with the possibility that some free customers will upgrade to become paying customers in the future.

- For products with strong network effects it is a good way to create a virtuous circle in which existing customers become the product’s marketing agents. For example, file sharing in Dropbox encourages current users to invite their friends to use Dropbox as well. Many network products result in a winner-take-all market. A freemium strategy allows for quick scaling to gain momentum and become the market leader.

- For experience goods, consumers need to try the product to see its value. Drew Houston, the founder and CEO of Dropbox, elaborated on this by saying, “The fact was that Dropbox was offering a product that people didn’t know they needed until they tried.”34

- Companies gain valuable feedback by observing the way users interact with products. When Adobe changed its strategy from selling a packaged product to a monthly subscription service with a freemium model, it quickly acquired millions of free users. Monitoring the usage of these consumers allows Adobe to learn what features consumers use more often, where users get stuck, what encourages higher product usage, and so on. This feedback allows Adobe to continuously innovate its product.

- Unlike a limited-time free trial, freemium creates a habit of product usage. The New York Times (NYT) decided to give users twenty free articles per month to get them into the habit of coming to the newspaper site frequently.

A critical question in designing a freemium product is how much to give away for free. Give too little and consumers won’t be excited to join. Give too much and no one will pay to upgrade. In designing its paywall, NYT arrived at twenty free articles per month in order to balance two revenue sources—from advertising and from digital subscriptions. Giving away too few articles would have created a significant drop in website traffic and therefore digital ad revenue, as the Times (of London) experienced. On the other hand, giving away too many articles for free would have limited the potential revenue from digital subscribers. NYT used consumer data and its best judgment to arrive at twenty free articles. It monitored consumers’ response to the paywall, and noting a healthy subscription rate for its digital version, it later reduced the number of free articles to five per month.

If you give away your product, how do you make money? Since many of the freemium customers are free, one may be tempted to conclude that their customer lifetime value is zero. However, these free customers bring value to the firm in two indirect ways—through referrals and network effects that reduces a firm’s customer-acquisition costs, and (for a small fraction of them) through upgrading to a paid version of the product. In a recent research paper, my colleagues and I showed that for a data-storage company a free user is typically worth 15 percent to 25 percent as much as a premium subscriber.35 Another study examined the network effects for a European auction house similar to eBay and found that one new seller on the site brings in almost three additional sellers and eleven additional buyers. Given the seller-acquisition cost of between €12 and €60 and the buyer-acquisition cost of between €5 and €25 for this site, the value of customers acquired through network effects is quite significant.36

While freemium is a good strategy for digital products because they have almost zero marginal cost of production and distribution, for physical products one must charge a price. In these situations, pricing becomes a decisive consideration for both the consumer and the firm. In the digital era, consumers have the ability to search prices across sites and firms have the ability to do frequent pricing experiments to stay competitive and determine optimal pricing.

Not only third-party sellers on Amazon have a wide variation in price over time. Amazon itself is offering different prices at different times. For many products, Amazon tests several prices on the same day. Temporal price variations are becoming a norm in the digital era, and every executive should consider dynamic pricing for his products, similar to what airlines have done for years.

OYO, India’s largest hotel network, boasting more than 6,500 hotel properties in 192 cities across the country, has taken the idea of dynamic pricing to a new level. Ritesh Agarwal, who founded and launched OYO when he was just nineteen years old, initially created a version of Airbnb, but soon realized that India lacked low-to-mid-budget hotels with reliable and standardized services. So he decided to change his business model and started asking existing budget hotels to give him a few rooms and convert them into OYO rooms with such standardized services as Wi-Fi, free breakfast, and clean bathrooms. Hotels with high fixed costs and low occupancy rates were happy to offer OYO some rooms as a way of generating additional income. While OYO’s consumer prices varied depending on market conditions and seasonality, the company initially offered hotel owners a “minimum price guarantee” that gave them a fixed monthly fee for the rooms they offered to OYO. Within a year OYO changed this policy to dynamic pricing that works as follows. Twice a day, once in the morning and once in the afternoon, OYO offers each hotel owner a certain price for its rooms. The owner can then decide how many rooms to offer OYO that day. Depending on the supply of the rooms and on market conditions, OYO then determines the price to offer consumers. In effect, OYO’s dynamic pricing policy attempts to balance—in real time—both the variability in the supply of hotel rooms and the variability in customer demand.

In conclusion, customer acquisition is critical for the growth of a company, and in this chapter we discussed which customers to acquire and how to acquire them. Engaging customers is a necessary condition for acquiring and retaining them, and this is the topic of our next chapter.