Chapter 8

Engaging Consumers

“The right message, to the right customer, at the right time”—marketing executives around the world are convinced that this goal is now becoming a reality, thanks to their ability to track every single click of a consumer on the web, know her location at any time through her mobile device, and have a deep understanding of her interests and activities through social media and Facebook. Sophisticated approaches such as programmatic media buying, real-time marketing, data mining, geotargeting, and retargeting have given marketing experts new confidence in their ability to achieve this goal.

Yet most consumers, by far, find ads annoying. A 2016 survey found that 90 percent of consumers skip preroll video ads—the ads that sites like YouTube force you to see before you can watch what you want. And if preroll isn’t annoying enough, Facebook is now testing a “midroll” video ad format in which an ad plays in the middle of your favorite video! Almost 84 percent of millennials, the prime target segment of most advertisers, admit to skipping or blocking ads all or some of the time.2 Another survey claimed that 69 percent of consumers skip ads on Snapchat.3 In December 2016, over 600 million devices were running ad-blocking software globally, a 30 percent increase over the year before.4 More than 28 percent of mobile devices in India and 58 percent in Indonesia were blocking ads as of December 2016.5 The advertising industry has come up with innovative metrics for ad exposure: Facebook considers it a view when a video plays for three seconds on its site. Snapchat counts it as a view if the video is rendered on the screen, even if it plays for half a second. In 2016, after months of deliberation, the Media Rating Council, an industry organization that sets standards for ad measurement, reported its ruling that a mobile-video ad impression is delivered if 50 percent of ad pixels are in view for two consecutive seconds. No matter what study you believe in, is a 1 percent click-through rate for online ads a huge success? Put differently, when was the last time you declared a victory when 99 percent of the time you failed to achieve your goal?

In spite of all the developments in technology and the rhetoric about engaging consumers, we have failed to take consumers’ perspective. Every brand in the world wants to engage with the consumer, but have the brand managers paused to ask why a consumer would want to engage with a bar of soap, a can of soda, or a bottle of beer?

Advertising was never meant to force people to watch things they did not want to see. The role of advertising is to provide value to consumers by offering them relevant information that helps them make better decisions. Google has been able to achieve this very effectively with search advertising by showing ads that are highly relevant to consumers’ search on their desktops and laptops. However, as consumers’ attention has moved to mobile devices and as companies have started shifting their ad budgets to mobile, even Google has struggled to make mobile advertising relevant to consumers.

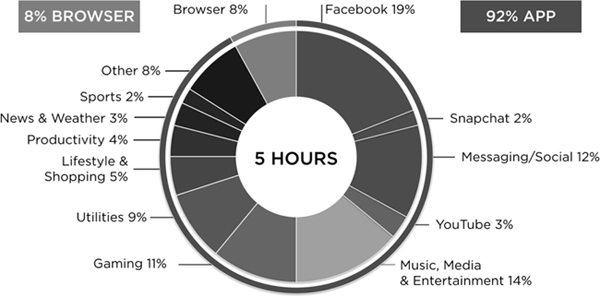

To understand why mobile advertising is so different we need to find out how people really spend time on their smartphones. Unlike on laptops and desktops, where browser search dominates, on mobile devices consumers spend over 90 percent of their time on apps, not browsers. A study of US consumers by Flurry, a mobile analytics company, shows that the majority of this time is spent on social networks such as Facebook and Snapchat, or using entertainment apps (see figure 8-1). Since there is no compelling reason for a consumer to download an app for, say, Coke or Dove soap, brand marketers spend the vast majority of their mobile budgets on in-app ads. These take the form of banner ads in gaming apps, preroll ads on YouTube videos, or ads in Facebook newsfeeds.

FIGURE 8-1

Time spent by US consumers on their smartphones

Source: Simon Khalaf and Lali Kesiraju, “U.S. Consumers Time-Spent on Mobile Crosses 5 Hours a Day,” March 2, 2017, http://flurrymobile.tumblr.com/post/157921590345/us-consumers-time-spent-on-mobile-crosses-5.

While industry studies are full of success stories that claim amazing return on dollars spent on ads in apps and on Facebook (a topic that we will address in the next chapter), let us pause to consider this from a consumer’s point of view. How relevant and useful is a banner ad for, say, BMW or Coke while you are playing Candy Crush or browsing your Facebook newsfeed? Misiek Piskorski, a professor of strategy and innovation at IMD and my former colleague at Harvard Business School, describes an ad in a Facebook newsfeed as being similar to a stranger pulling up a chair next to you when you and your friend are having a private conversation. Put differently, this is the digital version of the 7:00 p.m. sales call that you used to get when you sat down with your family for dinner. One study found that “to motivate a person to generate as many impressions in the presence of bad ads as they would in the presence of no ads or good ads, we would need to pay them roughly an additional $1 to $1.50 per thousand impressions . . . Publishers are often paid less than 50 cents per thousand impressions to run annoying ads, half as much as the estimated economic damage they incurred in our experiments.”6

As consumers, we have come to accept annoying ads as the cost of getting free content. But are there better ways to go about this, ways that help both consumers and brands? This critical question is the focus of this chapter.

Providing Value

The goal of marketing is to create value for consumers. Tesco’s introduction of virtual stores in South Korea and Unilever’s mobile radio station in India provide two excellent case studies of leveraging mobile technology to create win-win strategies for the company and for consumers.

Tesco in South Korea

In 1999, on the heels of Carrefour of France and Walmart of the United States, Tesco entered the South Korean market, one of the most lucrative consumer markets in Asia. As it started opening stores in Korea, under the name Homeplus, it faced a daunting challenge from the largest Korean retailer, Emart. By 2006, both Carrefour and Walmart had decided to pull out of Korea, and Emart acquired Walmart’s Korean operation. By 2009, Emart was dominant in the Korean market, with annual sales of $9.4 billion.7

How could Tesco attract more consumers and compete with Emart without significant additional investment in opening more retail stores? Most consumers hate going to the grocery store for their weekly shopping, so Tesco decided to bring the store to them. In 2011, the company opened its first virtual store in Seoul’s busiest subway station. It plastered the station with a picture of a store shelf that looked identical to an actual shelf in Tesco’s grocery store. After downloading the Homeplus app on their smartphones, consumers could scan the QR code of the virtual items while waiting for their morning trains, and the selected items would be delivered to them when they reached home in the evening. It solved a consumer problem, provided consumers significant value, and also drove business for Tesco. Within three months of launching this mobile app, sales of Homeplus increased by 130 percent, and their number of registered users went up by 76 percent.8 Alas, in 2015 Tesco pulled out of the Korean market, due to its own financial troubles at home and to stronger regulations imposed by the South Korean government. But the company’s app nonetheless remains a great example of innovative consumer engagement.

Unilever in India

In 2014, Hindustan Unilever Limited, the market leader of consumer products in India, faced the challenge of reaching the 130 million people in Bihar and Jharkhand. These two regions are among the most media-dark regions of India, where people do not have electricity for eight to ten hours every day. However, at the time, almost 54 million people had a rudimentary mobile phone—a feature phone, not a smartphone. Unilever decided to transform this basic phone into an entertainment conduit and give consumers something they did not have.

The company created an entertainment channel called Kan Khajura Station, which provided fifteen minutes of free, on-demand entertainment that included music, jokes, news, and promotions for certain Unilever brands. To get access to this entertainment channel consumers would call a toll-free number. As soon as the call was received, it was disconnected, to avoid any cost to the consumer, and an automated callback was generated (incoming calls are free in India) to give the consumer the free fifteen minutes of entertainment. Soon after the station’s launch, Unilever was receiving as many as 150,000 calls a day, and many consumers were calling several times a day. Within six months Kan Khajura Station had eight million unique subscribers, and awareness for Unilever brands had increased significantly. By converting the mobile phone into an entertainment conduit, Unilever created the largest media channel in Bihar and Jharkhand, at a cost of less than four cents per person.9 After its initial success, Hindustan Unilever extended Kan Khajura Station to all the remote villages and towns of India, where traditional media are either unavailable or unreliable. By 2015 the station had thirty-five million subscribers, and within two years of its launch these subscribers had listened to 900 million minutes of entertainment programing that included Hindustan Unilever ads forty-five million times. Taking a page out of the platform strategy discussed in chapter 3, Hindustan Unilever has opened up its station for non-Unilever brands that want to reach and engage these subscribers.10

Tesco and Unilever have the following things in common:

- Marketing is not just advertising. Neither Tesco nor Unilever created another ad campaign to engage consumers. Instead, they focused on solving consumers’ problems and providing consumers significant value.

- As a result, their overtures to consumers weren’t annoying. On the contrary, consumers willingly downloaded the Homeplus app and called Unilever to opt in for the entertainment channel. It is ironic that in a world of two-way communication, most advertisers still follow the age-old one-way communication approach in which consumers are passive receivers of banner or preroll ads.

- Both companies took advantage of the unique aspect of mobile devices. Tesco’s consumers could not scan the QR code with their laptops, and for Unilever’s consumers, radio and TV were not viable options due to frequent and prolonged power outages.

From Storytelling to Story Making

When M. V. Rajamannar (Raja) joined Mastercard in September 2013 as its chief marketing officer (CMO), he inherited a strong brand and the iconic “Priceless” ad campaign.11 Launched in 1997, this campaign showed vignettes of human interactions that concluded with the lines, “There are some things in life money can’t buy. For everything else, there’s Mastercard.” The campaign was so successful that in the next fifteen years it entered the vernacular in many countries. Yet Raja felt it was time for a change. He explained:

There were three fundamental reasons for us to rethink how we engage consumers. First, the Priceless campaign was designed for end consumers, but Mastercard does not issue cards, our partner banks do that. Any effort in engaging consumers should drive our business by helping our bank and merchant partners—a directive clearly communicated to me by Ajay Banga, our CEO.

Second, our brand was positioned as “the best way to pay” even though payment is the lowest emotional point for a consumer during her purchase. Consumers don’t get up in the morning thinking about payments. We needed to look beyond card usage because consumption is only a small part of human life. What happens in the rest of the life directly impacts the consumption of a product or service.

Third, although the Priceless campaign is very memorable, it relies on one-way communication while the world has moved to two-way interactions with consumers. In the era of Netflix and ad blocking no one is listening to our story, no matter how compelling it is. We need to shift from storytelling to story making by making consumers an integral part of the story.

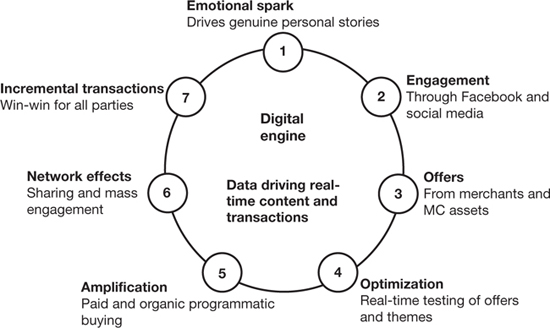

To drive this change, Raja and his team decided to position the brand as “Connecting People to Priceless Possibilities.” To bring this to life, they created a “digital engine” that leveraged digital and social media (see figure 8-2).

The digital engine is a seven-step process based on insights gleaned from data and real-time optimization.

- Emotional Spark. The first step is to create an emotional spark and a connection with consumers. Using data to understand consumers’ key passion points, Mastercard builds videos and creatives to ignite this spark and give consumers a reason to engage. For example, a few weeks before the 2014 New Year’s Eve, Mastercard produced a video in which the actor Hugh Jackman announced a promotion encouraging consumers to submit a story about someone who deeply mattered to them (“family, friends, mentors, who influenced us through their passions and wisdom”). The authors of the winning submissions would, on New Year’s Eve, be flown “anywhere in the world” to reunite with those both distant and dear. Mastercard envisioned each reunion as a “Priceless Surprise.”

- Engagement. By using data to identify the right audience, Mastercard targets that audience with a spark video through Facebook and social media. The goal is to encourage consumers to share their stories. To continue this excitement, Mastercard often produces a second video—in the Hugh Jackman case, the company showed Jackman surprising his own mentor in New York.

- Offers. With the goal of helping its partner banks and merchants in driving their business, which in turn helps Mastercard’s own revenue, the company identifies the best offers to match consumers’ interests. In the New Year’s Eve campaign, after Mastercard’s Asia-Pacific team found that Singapore was a favorite destination for Indian consumers traveling for the holiday, it partnered with Singapore’s Resorts World Sentosa with an attractive offer.

- Real-Time Optimization. At any point in time Mastercard may have several offers. Which of these offers should be highlighted and promoted is determined by A/B testing and real-time optimization of offers, themes, and budget allocation.

- Amplification. Real-time testing provides confidence to Mastercard about the potential success of these offers, and it also encourages its bank and merchant partners to co-market and co-fund these campaigns. This process amplifies both Mastercard’s budget and the impact of the program.

- Network Effects. A few weeks after consumers have submitted their stories, Mastercard selects winners, produces videos of them surprising their friends and families, and uses these videos in social media to encourage sharing.

- Incremental Transactions. These programs translate into incremental business for banks who issue cards, for merchants where consumers spend money, and for Mastercard, which gets a portion of every transaction.

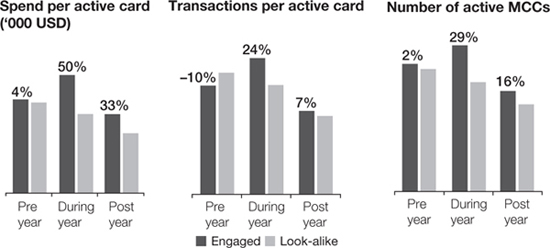

Figure 8-3 shows data about the business impact of Mastercard’s “Priceless Cities” program in the United States.

Transactional impact of US “Priceless Cities”

Engaged consumers spent 4 percent more in pre-year compared to a matched sample of look-alike consumers in the control group, but they spent 50 percent more during the campaign year and 33 percent more after the campaign year.

Source: Company documents.

Note: Engaged denotes cardholders who respond to “Priceless Cities” offers. Look-alike is a matched control sample. MCC stands for “merchant category code.” Pre-year: May 2012–April 2013. During year: May 2013–April 2014. Post-year: May 2014–April 2015.

The Mastercard case highlights important lessons on how to engage consumers:

- Have a Broad Message. Brands need to connect with consumers in how they live and spend their time. This means that firms need to go beyond the brand or product message to become more relevant in consumers’ lives. As Raja said, “Consumers don’t get up in the morning thinking about payments.” So even if you are the best form of payment, it does not matter to your consumers. The same is true for a car, a bar of soap, or a can of soda. Dove soap was very successful in creating a conversation among consumers with its “Real Beauty” campaign, which focused not on the brand or even the product category but on how women and society view beauty. More often than not these broader themes connect with consumers in a very emotional way.

- Shift from Storytelling to Story Making. Google and Facebook have democratized marketing, making it possible for even a small firm with a limited budget to engage in digital marketing and social media. On top of this, there is huge fragmentation in digital media, with the variety of outlets ranging from Snapchat and Instagram to millions of other websites and blogs. All of this has resulted in a significant increase in the supply of advertising, which in turn has led to clutter and consumers’ confusion and annoyance with ads. To break through this clutter, companies need to move from storytelling to story making. As Raja said, “no one is listening to our story, no matter how compelling it is.” A broader message that is emotionally engaging allows for a two-way conversation.

- Be Consistent with the Brand Value. In search of a broad and emotionally engaging message, brands often lose connection to their core value. Even in the digital world each brand needs to stand for something. Eric Reynolds, the CMO of Clorox, emphasized this aspect: “Nothing ever gets better until you’re really clear with yourself about what your brand stands for, why it even exists. At some point, someone has to say, ‘Stop. We’re doing all of this stuff—why? Why does it matter?’ It’s a leadership question. It’s someone declaring a better future and willing to go back and question some of the fundamentals of the brand.”12 In creating an emotional spark, Mastercard keeps three things in mind: (1) The context should appeal to its target audience. Based on its research, Mastercard identified nine passion points, including music, sports, travel, shopping, and dining. (2) The creative should tap into cultural trends of the time. (3) The content should be relevant and consistent with the image of the brand.

These guidelines are simple and straightforward, yet many companies forget them. Take the example of Pepsi’s “Refresh Project,” which was launched in 2010. Pepsi announced that it would award $20 million in grants to individuals, businesses, and nonprofits that promote a new idea to make a positive impact on community. A large number of submissions were about social causes that had nothing to do with Pepsi, and some—for example, reducing obesity—were in direct conflict with what Pepsi is trying to sell. In April 2017, Pepsi’s attempt to engage its consumers with a Kendall Jenner ad backfired, too, because people saw Pepsi exploiting consumers’ sentiment about “Black Lives Matter” without itself having any apparent interest in the cause. Blendtec, a company that sells professional and home blenders, offers the contrasting example of creating an engaging YouTube video series that is consistent with Blendtec’s brand. In the series, called Will It Blend, Tom Dickson, the company founder, blends a series of unusual objects, such as an iPhone or golf balls. Not only are the videos amusing and popular, garnering millions of views, but they also emphasize the power and features of Blendtec products.

- Create Engagement that Drives Business. Advertising needs to achieve two goals: engage and persuade. In the cluttered media environment, we often focus on getting consumers’ attention by engaging them with entertaining content. However, the ultimate goal of advertising is to drive business. Research by my colleague Thales Teixeira has shown that too much entertainment in ads may engage consumers but may detract from both communicating the brand message and increasing sales.13 Simply measuring engagement metrics, such as the number of video views, provides only a partial picture of a program’s success. Mastercard built its digital engine with a clear goal to engage consumers in a way that increases transactions. Using its pre and post studies it can monitor the success of its programs. Similarly, Will It Blend had a significant impact on the sales of Blendtec products.

Moment-Based Marketing

Advertisers are obsessed with knowing consumers—their demographics and interests, their network of friends, what they post on Instagram or Pinterest, what they write in social media. The more we know the consumer, the more targeted and relevant the ad will be—at least that is the hope. But consumers are complex and multidimensional. I am not only a professor but also a parent and, at different moments, a sports fan, a foodie, a traveler, and so on. My mindset and my receptivity to any message vary greatly depending on the context.

Vineet Mehra, the former president of global marketing services at Johnson & Johnson, noticed such a moment on the company’s message board. “At 4:20 a.m.,” explained Mehra, “we started seeing a lot of conversations like this: ‘Has anyone got any tips for getting a baby to sleep through the night?’ ‘My ten-month-old had me up six times last night, but can’t sleep now.’” Recognizing this moment of opportunity to connect with mothers, Johnson & Johnson created video content to help consumers.14 The same content would be far less effective in a different context.

Marketing experts have always focused on macromoments such as the Thanksgiving holiday or TV’s prime time. However, we now live in the mobile era, when, on average, consumers check their smartphones 150 times a day. More than 87 percent of consumers have their phones by their sides day and night, and 68 percent admit to checking their phones within fifteen minutes of waking up in the morning.15 Unlike television ads that aired at 8:00 p.m., regardless of whether or not that was the right time for a consumer, we now have the ability to wait for the right moment before sending a message to a consumer’s mobile phone. This is the era of micromoments, when messages need to arrive at the proper time, in the proper context. In a Harvard Business Review article, I explained this idea:

If you book an Uber ride on Friday evening, ads for restaurants and movies may be relevant at that moment. If you are stuck at an airport because of a delayed flight, you may be more inclined to sign up for Netflix. Driving on a highway at noontime is perhaps the best time for your Google Maps on your car dashboard to show nearby food places.16

These examples focus less on consumer demographics, interests, or even past purchases than they do on the moment and the context.

Moment-Based Marketing in Action

The following minicases illustrate how some companies are using moment-based marketing effectively.

- Sephora. Shopping in stores can be overwhelming for consumers, as they face a large number of choices. It is not uncommon for consumers in these situations to pull out their smartphones in order to find product ratings and consumer reviews. To Bridget Dolan, Sephora’s vice president of interactive media, this provides a great opportunity. She explains, “We think one of the biggest opportunities we have in retail is for our customers to leverage their phones as a shopping assistant when they are standing in the store.” To help shoppers in these moments, Sephora created an app that allows them to scan an item in the store and immediately see product ratings and reviews on their phones. “Having access to this information is that perfect new moment for customers to find everything they’re looking for and get advice from Sephora,” says Dolan.17

- Red Roof Inn. In the aforementioned Harvard Business Review article, I described how Red Roof Inn leveraged technology and consumer insights to send messages at the right moment: “Red Roof Inn realized that flight cancellations in the United States left 90,000 passengers stranded every day. Imagine the emotions of a typical passenger at that moment—it perhaps starts with frustration and anger at the airlines and then turns toward the need to find a place to stay overnight. Recognizing this, the marketing team of Red Roof Inn developed a way to track flight delays in real time that triggered targeted ads for Red Roof Inn near airports. Ads that said, ‘Stranded at the airport? Come stay with us!’ captured the consumers at the right moment, which resulted in a 60 percent increase in bookings compared to other campaigns.”18

- DBS Bank. As it is for most banks, mortgage lending is an attractive business for DBS, a bank based in Singapore. DBS started by creating a mobile app that allowed consumers to find mortgage rates and calculate monthly payments in order to ascertain the affordability of a house that they were considering. However, this app did not differentiate DBS from any other bank. How could DBS help consumers and differentiate itself from others? This question prompted the DBS team to dig deeper into consumers’ home-buying processes to understand specific moments where the bank could help consumers. This exercise led to the development of the Home Connect mobile app. If you are visiting a neighborhood to see houses and are curious to know the prices in that area, the app, according to DBS, lets you “simply hold up your phone and scan your surroundings to view the latest transacted prices in the area.” Or if your decision depends on schools, or distance to public transportation, the app can also help you with that information: “Can’t decide between two options? Check out the amenities and facilities nearby to help you compare. Distance to MRT station or the bus stop? What are the schools nearby? Is there a supermarket in the area?”19 Recognizing the factors that would help consumers make a better decision, DBS integrated publicly available information from various Singapore neighborhoods in its app. This now gives a compelling reason for consumers to use the DBS app, which has become a lead-generation tool for the bank’s mortgage business.

How to Win Micromoments

A 2015 study by Forrester found that only one-third of businesses prioritize a moment-based approach and only 2 percent of firms have all the necessary elements for a moments-ready organization.20 So how do you create a moment-based program? Here are some guidelines:

- Map Consumers’ Journey to Understand Their Intent and Context. According to Google a micromoment is an opportunity that arises when a consumer has intent for a task in a specific context and wants an immediate result. Intent requires us to understand what a consumer needs at a specific moment, and context highlights how that consumer need might change based on a particular situation—for example, whether a consumer is in a store or at home. Elaborating on the intent-context-immediacy nature of micromoments, Lisa Gevelber, Google’s vice president for marketing and a pioneer of the micromoments concept, said, “The advertising game is no longer about reach and frequency. Now more than ever, intent is more important than identity and demographics, and immediacy is more important than brand loyalty.”21

To understand consumers’ intent and context at a specific moment, firms need to map the entire consumer journey at every touchpoint, recognizing two critical things. First, ethnographic and observational studies are often more insightful for understanding the consumer journey than are surveys or consumers’ digital footprints. It is unlikely that Sephora would have recognized consumers’ desire to see product reviews on their smartphones in the store if the company had relied only on surveys or management judgment. Second, for mapping the consumer journey, management typically focuses on the firm’s product, not on the broader consumer journey, which often provides better insights. For example, to map the consumer journey for a mortgage, a bank may consider the following steps: awareness of the bank → consideration → loan application → loan approval → loan origination → monthly payment, etc. If DBS bank had followed this approach it would have missed the opportunity to provide unique value to its customers through information about home prices and neighborhood amenities, information that was conveyed even before consumers were thinking of applying for a mortgage.

- Classify Different Moments into Coherent Groups. Mapping the large number of micromoments among consumers can seem daunting and impractical. Therefore it is useful to categorize these moments into groups that are relevant for consumers and actionable for the firm. Based on its studies, Google has classified micromoments across four groups: I want to know, I want to go, I want to do, and I want to buy. In the I-want-to-know moment, consumers are looking for information to make a decision but perhaps are not yet ready to buy. In one of its studies, Google found that “1 in 3 smartphone users purchased from a company or brand other than the one they intended to because of the information provided in the moment they needed it.”22 Sephora used its app effectively to provide product reviews to its customers in the store. The I-want-to-go moment reflects consumers’ intent to visit a store to check, test, or buy a product that they may have researched online. Knowing the location of the nearby store and the availability of the desired product may be helpful here. I-want-to-do moments are when consumers may need information on such things as how to fix a toilet or how to apply eyeliner. I-want-to-buy moments are when consumers are ready to buy the product. Your business may have similar or different categories of moments. You don’t necessarily have to follow Google’s classification, but it is useful to group hundreds of micromoments into actionable and meaningful buckets.

- Provide Useful Information. As mentioned before, advertising is not about bombarding consumers with messages they don’t want. Instead, it is the art of providing valuable information when consumers need it. Technology enables us to identify these micromoments of consumer need, and it is our task to provide useful information at those points in time. In all three examples above—Sephora, Red Roof Inn, and DBS—the companies offered information that was highly valuable to consumers at a particular moment. If you’re standing in Home Depot trying to figure out which materials you need to purchase in order to fix your bathtub, won’t you find it helpful if Home Depot has how-to videos that show not only what parts may be needed but also how to go about fixing your bathtub? In fact, Home Depot has a large collection of how-to videos, and these videos, taken together, have been viewed more than forty-three million times. These are not intrusive banner ads on consumers’ smartphones but useful content that helps the company earn loyalty in the long run.

- Create Snackable Content. On average, consumers spend about five minutes per session on the top 100 apps, but for more than one-third of mobile apps engagement lasts for less than a minute.23 Based on its studies Google concluded that the average time spent per mobile session is only one minute and ten seconds long.24 Regardless of the precise numbers, all these studies point to the fact that consumers have a very short attention span when they are looking for information on their smartphones. The situation, then, calls for snackable content that addresses a specific intent of the consumer at that moment. BuzzFeed gained a significant following for its news site based on this idea. Recognizing consumers’ short attention spans, Facebook designed its newsfeed to include short videos. Safeway produced videos roughly fifteen to twenty seconds long for Facebook, ones that offered consumers culinary tips and cooking advice.

- Speed Matters. These days consumers are always in a hurry and very impatient. If a website takes more than a few seconds to load, consumers get frustrated and leave the site. Based on an analysis of 900,000 mobile ads’ landing pages across 126 countries, Google found that, on average, it takes twenty-two seconds to fully load a mobile landing page. And 53 percent of mobile-site visitors leave a page that takes longer than three seconds to load.25 Videos and images make it difficult for many sites to load faster, and often the cliché that “less is more” is applicable in these situations.

The three main topics discussed in this chapter—providing value to customers, shifting from storytelling to story making, and moment-based marketing—all point to a fundamental reality about customer engagement. Even though the tools of reaching consumers have changed in the digital era, we still need to have a deep understanding of consumers and provide value to engage them. Annoying ads are not only ineffective but costly to advertisers and publishers.