CHAPTER

TWELVE

CORPORATE BONDS

FRANK J. FABOZZI, PH.D., CFA, CPA

Professor of Finance

EDHEC Business School

STEVEN V. MANN, PH.D.

Professor of Finance

Moore School of Business

University of South Carolina

ADAM B. COHEN, J.D.

Founder

Covenant Review

In its simplest form, a corporate bond is a debt instrument that obligates the issuer to pay a specified percentage of the bond’s par value on designated dates (the coupon payments) and to repay the bond’s par or principal value at maturity. Failure to pay the interest and/or principal when due (and to meet other of the debt’s provisions) in accordance with the instrument’s terms constitutes legal default, and court proceedings can be instituted to enforce the contract. Bondholders as creditors have a prior legal claim over common and preferred shareholders as to both the corporation’s income and assets for cash flows due them and may have a prior claim over other creditors if liens and mortgages are involved. This legal priority does not insulate bondholders from financial loss. Indeed, bondholders are fully exposed to the firm’s prospects as to the ability to generate cash-flow sufficient to pay its obligations.

Corporate bonds usually are issued in denominations of $1,000 and multiples thereof. In common usage, a corporate bond is assumed to have a par value of $1,000 unless otherwise explicitly specified. A security dealer who says that she has five bonds to sell means five bonds each of $1,000 principal amount. If the promised rate of interest (coupon rate) is 6%, the annual amount of interest on each bond is $60, and the semiannual interest is $30.

Although there are technical differences between bonds, notes, and debentures, we will use Wall Street convention and call fixed income debt by the general term—bonds.

THE CORPORATE TRUSTEE

The promises of corporate bond issuers and the rights of investors who buy them are set forth in great detail in contracts generally called indentures. If bondholders were handed the complete indenture, some may have trouble understanding the legalese and have even greater difficulty in determining from time to time if the corporate issuer is keeping all the promises made. Further, it may be practically difficult and expensive for any one bondholder to try to enforce the indenture if those promises are not being kept. These problems are solved in part by bringing in a corporate trustee as a third party to the contract. The indenture is made out to the corporate trustee as a representative of the interests of bondholders; that is, the trustee acts in a fiduciary capacity for investors who own the bond issue.

A corporate trustee is a bank or trust company with a corporate trust department and officers who are experts in performing the functions of a trustee. The corporate trustee must, at the time of issue, authenticate the bonds issued; that is, keep track of all the bonds sold, and make sure that they do not exceed the principal amount authorized by the indenture. It must obtain and address various certifications and requests from issuers, attorneys, and bondholders about compliance with the covenants of the indenture. These covenants are many and technical, and they must be watched during the entire period that a bond issue is outstanding. We will describe some of these covenants in subsequent pages.

It is very important that corporate trustees be competent and financially responsible. To this end, there is a federal statute known as the Trust Indenture Act that generally requires a corporate trustee for corporate bond offerings in the amount of more than $5 million sold in interstate commerce. The indenture must include adequate requirements for performance of the trustee’s duties on behalf of bondholders; there must be no conflict between the trustee’s interest as a trustee and any other interest it may have, especially if it is also a creditor of the issuer; and there must be provision for reports by the trustee to bondholders. If a corporate issuer has breached an indenture promise, such as not to borrow additional secured debt, or fails to pay interest or principal, the trustee may declare a default and take such action as may be necessary to protect the rights of bondholders.

However, it must be emphasized that the trustee is paid by the debt issuer and can only do what the indenture provides. The indenture may contain a clause stating that the trustee undertakes to perform such duties and only such duties as are specifically set forth in the indenture, and no implied covenants or obligations shall be read into the indenture against the trustee. Trustees often are not required to take actions such as monitoring corporate balance sheets to determine issuer covenant compliance, and in fact, indentures often expressly allow a trustee to rely upon certifications and opinions from the issuer and its attorneys. The trustee is generally not bound to make investigations into the facts surrounding documents delivered to it, but it may do so if it sees fit. Also, the trustee is usually under no obligation to exercise the rights or powers under the indenture at the request of bondholders unless it has been offered reasonable security or indemnity.

The terms of bond issues set forth in bond indentures are always a compromise between the interests of the bond issuer and those of investors who buy bonds. The issuer always wants to pay the lowest possible rate of interest and wants its actions bound as little as possible with legal covenants. Bondholders want the highest possible interest rate, the best security, and a variety of covenants to restrict the issuer in one way or another. As we discuss the provisions of bond indentures, keep this opposition of interests in mind and see how compromises are worked out in practice. A more detailed description of covenants is provided in Chapter 43 where credit analysis is covered.

SOME BOND FUNDAMENTALS

Bonds can be classified by a number of characteristics, which we will use for ease of organizing this section.

Bonds Classified by Issuer Type

The five broad categories of corporate bonds sold in the United States based on the type of issuer are public utilities, transportations, industrials, banks and finance companies, and international or Yankee issues. Finer breakdowns are often made by market participants to create homogeneous groupings. For example, public utilities are subdivided into telephone or communications, electric companies, gas distribution and transmission companies, and water companies. The transportation industry can be subdivided into airlines, railroads, and trucking companies. Like public utilities, transportation companies often have various degrees of regulation or control by state and/or federal government agencies. Industrials are a catchall class, but even here, finer degrees of distinction may be needed by analysts. The industrial grouping includes manufacturing and mining concerns, retailers, and service-related companies. Even the Yankee or international borrower sector can be more finely tuned. For example, one might classify the issuers into categories such as supranational borrowers (International Bank for Reconstruction and Development and the European Investment Bank), sovereign issuers (Canada, Australia, and the United Kingdom), and foreign municipalities and agencies.

Corporate Debt Maturity

A bond’s maturity is the date on which the issuer’s obligation to satisfy the terms of the indenture is fulfilled. On that date, the principal is repaid with any premium and accrued interest that may be due. However, as we shall see later when discussing debt redemption, the final maturity date as stated in the issue’s title may or may not be the date when the contract terminates. Many issues can be retired prior to maturity. The maturity structure of a particular corporation can be accessed using the Bloomberg function DDIS.

Interest Payment Characteristics

The three main interest payment classifications of domestically issued corporate bonds are straight-coupon bonds, zero-coupon bonds, and floating-rate, or variable-rate, bonds. Floating-rate issues are discussed in Chapter 17, and the other two types are examined below.

However, before we get into interest-rate characteristics, let us briefly discuss bond types. We refer to the interest rate on a bond as the coupon. This is technically wrong because bonds issued today do not have coupons attached. Instead, bonds are represented by a certificate, similar to a stock certificate, with a brief description of the terms printed on both sides. These are called registered bonds. The principal amount of the bond is noted on the certificate, and the interest-paying agent or trustee has the responsibility of making payment by check to the registered holder on the due date. Years ago bonds were issued in bearer or coupon form, with coupons attached for each interest payment. However, the registered form is considered safer and entails less paperwork. As a matter of fact, the registered bond certificate is on its way out as more and more issues are sold in book-entry form. This means that only one master or global certificate is issued. It is held by a central securities depository that issues receipts denoting interests in this global certificate.

Straight-coupon bonds have an interest rate set for the life of the issue, however long or short that may be; they are also called fixed-rate bonds. Most fixed-rate bonds in the United States pay interest semiannually and at maturity. For example, consider the 4.75% Notes due 2013 issued by Goldman Sachs Group in July 2003. This bond carries a coupon rate of 4.75% and has a par amount of $1,000. Accordingly, this bond requires payments of $23.75 each January 15 and July 15, including the maturity date of July 15, 2013. On the maturity date, the bond’s par amount is also paid. Bonds with annual coupon payments are uncommon in the U.S. capital markets but are the norm in continental Europe.

Interest on corporate bonds is based on a year of 360 days made up of twelve 30-day months. The corporate calendar day-count convention is referred to as 30/360.

Most fixed-rate corporate bonds pay interest in a standard fashion. However, there are some variations of which one should be aware. Most domestic bonds pay interest in U.S. dollars. However, starting in the early 1980s, issues were marketed with principal and interest payable in other currencies, such as the Australian, New Zealand, or Canadian dollar or the British pound. Generally, interest and principal payments are converted from the foreign currency to U.S. dollars by the paying agent unless it is otherwise notified. The bondholders bear any costs associated with the dollar conversion. Foreign currency issues provide investors with another way of diversifying a portfolio, but not without risk. The holder bears the currency, or exchange-rate, risk in addition to all the other risks associated with debt instruments.

There are a few issues of bonds that can participate in the fortunes of the issuer over and above the stated coupon rate. These are called participating bonds because they share in the profits of the issuer or the rise in certain assets over and above certain minimum levels. Another type of bond rarely encountered today is the income bond. These bonds promise to pay a stipulated interest rate, but the payment is contingent on sufficient earnings and is in accordance with the definition of available income for interest payments contained in the indenture. Repayment of principal is not contingent. Interest may be cumulative or noncumulative. If payments are cumulative, unpaid interest payments must be made up at some future date. If noncumulative, once the interest payment is past, it does not have to be repaid. Failure to pay interest on income bonds is not an act of default and is not a cause for bankruptcy. Income bonds have been issued by some financially troubled corporations emerging from reorganization proceedings.

Zero-coupon bonds are, just as the name implies, bonds without coupons or an interest rate. Essentially, zero-coupon bonds pay only the principal portion at some future date. These bonds are issued at discounts to par; the difference constitutes the return to the bondholder. The difference between the face amount and the offering price when first issued is called the original-issue discount (OID). The rate of return depends on the amount of the discount and the period over which it accretes to par. For example, consider a zero-coupon bond issued by Xerox that matures September 30, 2023 and is priced at 55.835 as of mid-May 2011. In addition, this bond is putable starting on September 30, 2011 at 41.77. These embedded option features will be discussed in more detail shortly.

Zeros were first publicly issued in the corporate market in the spring of 1981 and were an immediate hit with investors. The rapture lasted only a couple of years because of changes in the income tax laws that made ownership more costly on an after-tax basis. Also, these changes reduced the tax advantages to issuers. However, tax-deferred investors, such as pension funds, could still take advantage of zero-coupon issues. One important risk is eliminated in a zero-coupon investment—the reinvestment risk. Because there is no coupon to reinvest, there isn’t any reinvestment risk. Of course, although this is beneficial in declining-interest-rate markets, the reverse is true when interest rates are rising. The investor will not be able to reinvest an income stream at rising reinvestment rates. Investors tend to find zeros less attractive in lower-interest-rate markets because compounding is not as meaningful as when rates are higher. Also, the lower the rates are, the more likely it is that they will rise again, making a zero-coupon investment worth less in the eyes of potential holders.

In bankruptcy, a zero-coupon bond creditor can claim the original offering price plus the accretion that represents accrued and unpaid interest to the date of the bankruptcy filing, but not the principal amount of $1,000. Zero-coupon bonds have been sold at deep discounts, and the liability of the issuer at maturity may be substantial. The accretion of the discount on the corporation’s books is not put away in a special fund for debt retirement purposes. There are no sinking funds on most of these issues. One hopes that corporate managers invest the proceeds properly and run the corporation for the benefit of all investors so that there will not be a cash crisis at maturity. The potentially large balloon repayment creates a cause for concern among investors. Thus it is most important to invest in higher-quality issues so as to reduce the risk of a potential problem. If one wants to speculate in lower-rated bonds, then that investment should throw off some cash return.

Finally, a variation of the zero-coupon bond is the deferred-interest bond (DIB), also known as a zero-coupon bond. These bonds generally have been subordinated issues of speculative-grade issuers, also known as junk issuers. Most of the issues are structured so that they do not pay cash interest for the first five years. At the end of the deferred-interest period, cash interest accrues and is paid semiannually until maturity, unless the bonds are redeemed earlier. The deferred-interest feature allows newly restructured, highly leveraged companies and others with less-than-satisfactory cash flows to defer the payment of cash interest over the early life of the bond. Barring anything untoward, when cash interest payments start, the company will be able to service the debt. If it has made excellent progress in restoring its financial health, the company may be able to redeem or refinance the debt rather than have high interest outlays.

An offshoot of the deferred-interest bond is the pay-in-kind (PIK) debenture. With PIKs, cash interest payments are deferred at the issuer’s option until some future date. Instead of just accreting the original-issue discount as with DIBs or zeros, the issuer pays out the interest in additional pieces of the same security. The option to pay cash or in-kind interest payments rests with the issuer, but in many cases the issuer has little choice because provisions of other debt instruments often prohibit cash interest payments until certain indenture or loan tests are satisfied. The holder just gets more pieces of paper, but these at least can be sold in the market without giving up one’s original investment; PIKs, DIBs, and zeros do not have provisions for the resale of the interest portion of the instrument. An investment in this type of bond, because it is issued by speculative-grade companies, requires careful analysis of the issuer’s cash-flow prospects and ability to survive.

SECURITY FOR BONDS

Investors who buy corporate bonds prefer some kind of security underlying the issue. Either real property (using a mortgage) or personal property may be pledged to offer security beyond that of the general credit standing of the issuer. In fact, the kind of security or the absence of a specific pledge of security is usually indicated by the title of a bond issue. However, the best security is a strong general credit that can repay the debt from earnings.

Mortgage Bond

A mortgage bond grants the bondholders a first-mortgage lien on substantially all its properties. This lien provides additional security for the bondholder. As a result, the issuer is able to borrow at a lower rate of interest than if the debt were unsecured. A debenture issue (i.e., unsecured debt) of the same issuer almost surely would carry a higher coupon rate, other things equal. A lien is a legal right to sell mortgaged property to satisfy unpaid obligations to bondholders. In practice, foreclosure of a mortgage and sale of mortgaged property are unusual. If a default occurs, there is usually a financial reorganization on the part of the issuer, in which provision is made for settlement of the debt to bondholders. The mortgage lien is important, though, because it gives the mortgage bondholders a very strong bargaining position relative to other creditors in determining the terms of a reorganization.

Often first-mortgage bonds are issued in series with bonds of each series secured equally by the same first mortgage. Many companies, particularly public utilities, have a policy of financing part of their capital requirements continuously by long-term debt. They want some part of their total capitalization in the form of bonds because the cost of such capital is ordinarily less than that of capital raised by sale of stock. Thus, as a principal amount of debt is paid off, they issue another series of bonds under the same mortgage. As they expand and need a greater amount of debt capital, they can add new series of bonds. It is a lot easier and more advantageous to issue a series of bonds under one mortgage and one indenture than it is to create entirely new bond issues with different arrangements for security. This arrangement is called a blanket mortgage. When property is sold or released from the lien of the mortgage, additional property or cash may be substituted or bonds may be retired in order to provide adequate security for the debtholders.

When a bond indenture authorizes the issue of additional series of bonds with the same mortgage lien as those already issued, the indenture imposes certain conditions that must be met before an additional series may be issued. Bondholders do not want their security impaired; these conditions are for their benefit. It is common for a first-mortgage bond indenture to specify that property acquired by the issuer subsequent to the granting of the first-mortgage lien shall be subject to the first-mortgage lien. This is termed the after-acquired clause. Then the indenture usually permits the issue of additional bonds up to some specified percentage of the value of the after-acquired property, such as 60%. The other 40%, or whatever the percentage may be, must be financed in some other way. This is intended to ensure that there will be additional assets with a value significantly greater than the amount of additional bonds secured by the mortgage. Another customary kind of restriction on the issue of additional series is a requirement that earnings in an immediately preceding period must be equal to some number of times the amount of annual interest on all outstanding mortgage bonds including the new or proposed series (1.5, 2, or some other number). For this purpose, earnings usually are defined as earnings before income tax. Still another common provision is that additional bonds may be issued to the extent that earlier series of bonds have been paid off.

One seldom sees a bond issue with the term second mortgage in its title. The reason is that this term has a connotation of weakness. Sometimes companies get around that difficulty by using such words as first and consolidated, first and refunding, or general and refunding mortgage bonds. Usually this language means that a bond issue is secured by a first mortgage on some part of the issuer’s property but by a second or even third lien on other parts of its assets. A general and refunding mortgage bond is generally secured by a lien on all the company’s property subject to the prior lien of first-mortgage bonds, if any are still outstanding.

Collateral Trust Bonds

Some companies do not own fixed assets or other real property and so have nothing on which they can give a mortgage lien to secure bondholders. Instead, they own securities of other companies; they are holding companies, and the other companies are subsidiaries. To satisfy the desire of bondholders for security, they pledge stocks, notes, bonds, or whatever other kinds of obligations they own. These assets are termed collateral (or personal property), and bonds secured by such assets are collateral trust bonds. Some companies own both real property and securities. They may use real property to secure mortgage bonds and use securities for collateral trust bonds. As an example, consider the 10.375% Collateral Trust Bonds due 2018 issued by National Rural Utilities. According to the bond’s prospectus, the securities deposited with the trustee include mortgage notes, cash, and other permitted investments.

The legal arrangement for collateral trust bonds is much the same as that for mortgage bonds. The issuer delivers to a corporate trustee under a bond indenture the securities pledged, and the trustee holds them for the benefit of the bondholders. When voting common stocks are included in the collateral, the indenture permits the issuer to vote the stocks so long as there is no default on its bonds. This is important to issuers of such bonds because usually the stocks are those of subsidiaries, and the issuer depends on the exercise of voting rights to control the subsidiaries.

Indentures usually provide that, in event of default, the rights to vote stocks included in the collateral are transferred to the trustee. Loss of the voting right would be a serious disadvantage to the issuer because it would mean loss of control of subsidiaries. The trustee also may sell the securities pledged for whatever prices they will bring in the market and apply the proceeds to payment of the claims of collateral trust bondholders. These rather drastic actions, however, usually are not taken immediately on an event of default. The corporate trustee’s primary responsibility is to act in the best interests of bondholders, and their interests may be served for a time at least by giving the defaulting issuer a proxy to vote stocks held as collateral and thus preserve the holding company structure. It also may defer the sale of collateral when it seems likely that bondholders would fare better in a financial reorganization than they would by sale of collateral.

Collateral trust indentures contain a number of provisions designed to protect bondholders. Generally, the market or appraised value of the collateral must be maintained at some percentage of the amount of bonds outstanding. The percentage is greater than 100 so that there will be a margin of safety. If collateral value declines below the minimum percentage, additional collateral must be provided by the issuer. There is almost always provision for withdrawal of some collateral, provided other acceptable collateral is substituted.

Collateral trust bonds may be issued in series in much the same way that mortgage bonds are issued in series. The rules governing additional series of bonds require that adequate collateral must be pledged, and there may be restrictions on the use to which the proceeds of an additional series may be put. All series of bonds are issued under the same indenture and have the same claim on collateral.

Since 2005, an increasing percentage of high yield bond issues have been secured by some mix of mortgages and other collateral on a first, second, or even third lien basis. These secured high yield bonds have very customized provisions for issuing additional secured debt and there is some debate about whether the purported collateral for these kinds of bonds will provide greater recoveries in bankruptcy than traditional unsecured capital structures over an economic cycle.

Equipment Trust Certificates

The desire of borrowers to pay the lowest possible rate of interest on their obligations generally leads them to offer their best security and to grant lenders the strongest claim on it. Many years ago, the railway companies developed a way of financing purchase of cars and locomotives, called rolling stock, that enabled them to borrow at just about the lowest rates in the corporate bond market.

Railway rolling stock has for a long time been regarded by investors as excellent security for debt. This equipment is sufficiently standardized that it can be used by one railway as well as another. And it can be readily moved from the tracks of one railroad to those of another. There is generally a good market for lease or sale of cars and locomotives. The railroads have capitalized on these characteristics of rolling stock by developing a legal arrangement for giving investors a legal claim on it that is different from, and generally better than, a mortgage lien.

The legal arrangement is one that vests legal title to railway equipment in a trustee, which is better from the standpoint of investors than a first-mortgage lien on property. A railway company orders some cars and locomotives from a manufacturer. When the job is finished, the manufacturer transfers the legal title to the equipment to a trustee. The trustee leases it to the railroad that ordered it and at the same time sells equipment trust certificates (ETCs) in an amount equal to a large percentage of the purchase price, normally 80%. Money from the sale of certificates is paid to the manufacturer. The railway company makes an initial payment of rent equal to the balance of the purchase price, and the trustee gives that money to the manufacturer. Thus the manufacturer is paid off. The trustee collects lease rental money periodically from the railroad and uses it to pay interest and principal on the certificates. These interest payments are known as dividends. The amounts of lease rental payments are worked out carefully so that they are enough to pay the equipment trust certificates. At the end of some period of time, such as 15 years, the certificates are paid off, the trustee sells the equipment to the railroad for some nominal price, and the lease is terminated.

Railroad ETCs usually are structured in serial form; that is, a certain amount becomes payable at specified dates until the final installment. For example, a $60 million ETC might mature $4 million on each June 15 from 2000 through 2014. Each of the 15 maturities may be priced separately to reflect the shape of the yield curve, investor preference for specific maturities, and supply-and-demand considerations. The advantage of a serial issue from the investor’s point of view is that the repayment schedule matches the decline in the value of the equipment used as collateral. Hence principal repayment risk is reduced. From the issuer’s side, serial maturities allow for the repayment of the debt periodically over the life of the issue, making less likely a crisis at maturity due to a large repayment coming due at one time.

The beauty of this arrangement from the viewpoint of investors is that the railroad does not legally own the rolling stock until all the certificates are paid. In case the railroad does not make the lease rental payments, there is no big legal hassle about foreclosing a lien. The trustee owns the property and can take it back because failure to pay the rent breaks the lease. The trustee can lease the equipment to another railroad and continue to make payments on the certificates from new lease rentals.

This description emphasizes the legal nature of the arrangement for securing the certificates. In practice, these certificates are regarded as obligations of the railway company that leased the equipment and are shown as liabilities on its balance sheet. In fact, the name of the railway appears in the title of the certificates. In the ordinary course of events, the trustee is just an intermediary who performs the function of holding title, acting as lessor, and collecting the money to pay the certificates. It is significant that even in the worst years of a depression, railways have paid their equipment trust certificates, although they did not pay bonds secured by mortgages. Although railroads have issued the largest amount of equipment trust certificates, airlines also have used this form of financing.

Debenture Bonds

While bondholders prefer to have security underlying their bonds, all else equal, most bonds issued are unsecured. These unsecured bonds are called debentures. With the exception of the utilities and structured products, nearly all other corporate bonds issued are unsecured.

Debentures are not secured by a specific pledge of designated property, but this does not mean that they have no claim on the property of issuers or on their earnings. Debenture bondholders have the claim of general creditors on all assets of the issuer not pledged specifically to secure other debt. And they even have a claim on pledged assets to the extent that these assets have value greater than necessary to satisfy secured creditors. In fact, if there are no pledged assets and no secured creditors, debenture bondholders have first claim on all assets along with other general creditors.

These unsecured bonds are sometimes issued by companies that are so strong financially and have such a high credit rating that to offer security would be superfluous. Such companies simply can turn a deaf ear to investors who want security and still sell their debentures at relatively low interest rates. But debentures sometimes are issued by companies that have already sold mortgage bonds and given liens on most of their property. These debentures rank below the mortgage bonds or collateral trust bonds in their claim on assets, and investors may regard them as relatively weak. This is the kind that bears the higher rates of interest.

Even though there is no pledge of security, the indentures for debenture bonds may contain a variety of provisions designed to afford some protection to investors. Sometimes the amount of a debenture bond issue is limited to the amount of the initial issue. This limit is to keep issuers from weakening the position of debenture holders by running up additional unsecured debt. Sometimes additional debentures may be issued a specified number of times in a recent accounting period, provided that the issuer has earned its bond interest on all existing debt plus the additional issue.

If a company has no secured debt, it is customary to provide that debentures will be secured equally with any secured bonds that may be issued in the future. This is known as the negative-pledge clause. Some provisions of debenture bond issues are intended to protect bondholders against other issuer actions when they might be too harmful to the creditworthiness of the issuer. For example, some provisions of debenture bond issues may require maintaining some level of net worth, restrict selling major assets, or limit paying dividends in some cases. However, the trend in recent years, at least with investment-grade companies, is away from indenture restrictions.

Subordinated and Convertible Debentures

Many corporations issue subordinated debenture bonds. The term subordinated means that such an issue ranks after secured debt, after debenture bonds, and often after some general creditors in its claim on assets and earnings. Owners of this kind of bond stand last in line among creditors when an issuer fails financially.

Because subordinated debentures are weaker in their claim on assets, issuers would have to offer a higher rate of interest unless they also offer some special inducement to buy the bonds. The inducement can be an option to convert bonds into stock of the issuer at the discretion of bondholders. If the issuer prospers and the market price of its stock rises substantially in the market, the bondholders can convert bonds to stock worth a great deal more than what they paid for the bonds. This conversion privilege also may be included in the provisions of debentures that are not subordinated. Convertible securities are discussed in Chapters 14 and 42.

The bonds may be convertible into the common stock of a corporation other than that of the issuer. Such issues are called exchangeable bonds. There are also issues indexed to a commodity’s price or its cash equivalent at the time of maturity or redemption.

Guaranteed Bonds

Sometimes a corporation may guarantee the bonds of another corporation. Such bonds are referred to as guaranteed bonds. The guarantee, however, does not mean that these obligations are free of default risk. The safety of a guaranteed bond depends on the financial capability of the guarantor to satisfy the terms of the guarantee, as well as the financial capability of the issuer. The terms of the guarantee may call for the guarantor to guarantee the payment of interest and/or repayment of the principal. A guaranteed bond may have more than one corporate guarantor. Each guarantor may be responsible for not only its pro rata share but also the entire amount guaranteed by the other guarantors.

ALTERNATIVE MECHANISMS TO RETIRE DEBT BEFORE MATURITY

We can partition the alternative mechanisms to retire debt into two broad categories—namely, those mechanisms that must be included in the bond’s indenture in order to be used and those mechanisms that can be used without being included in the bond’s indenture. Among those debt retirement mechanisms included in a bond’s indenture are the following: call and refunding provisions, sinking funds, maintenance and replacement funds, and redemption through sale of assets. Alternatively, some debt retirement mechanisms are not required to be included in the bond indenture (e.g., fixed-spread tender offers).

Call and Refunding Provisions

Many corporate bonds contain an embedded option that gives the issuer the right to buy the bonds back at a fixed price either in whole or in part prior to maturity. The feature is known as a call provision. The ability to retire debt before its scheduled maturity date is a valuable option for which bondholders will demand compensation ex-ante. All else equal, bondholders will pay a lower price for a callable bond than an otherwise identical option-free (i.e., straight) bond. The difference between the price of an option-free bond and the callable bond is the value of the embedded call option.

Conventional wisdom suggests that the most compelling reason for corporations to retire their debt prior to maturity is to take advantage of declining borrowing rates. If they are able to do so, firms will substitute new, lower-cost debt for older, higher-cost issues. However, firms retire their debt for other reasons as well. For example, firms retire their debt to eliminate restrictive covenants, to alter their capital structure, to increase shareholder value, or to improve financial/managerial flexibility. There are two types of call provisions included in corporate bonds—a fixed-price call and a make-whole call. We will discuss each in turn.

Fixed-Price Call Provision

With a standard fixed-price call provision, the bond issuer has the option to buy back some or all of the bond issue prior to maturity at a fixed price. The fixed price is termed the call price. Normally, the bond’s indenture contains a call-price schedule that specifies when the bonds can be called and at what prices. The call prices generally start at a substantial premium over par and decline toward par over time such that in the final years of a bond’s life, the call price is usually par.

In some corporate issues, bondholders are afforded some protection against a call in the early years of a bond’s life. This protection usually takes one of two forms. First, some callable bonds possess a feature that prohibits a bond call for a certain number of years. Second, some callable bonds prohibit the bond from being refunded for a certain number of years. Such a bond is said to be nonrefundable. Prohibition of refunding precludes the redemption of a bond issue if the funds used to repurchase the bonds come from new bonds being issued with a lower coupon than the bonds being redeemed. However, a refunding prohibition does not prevent the redemption of bonds from funds obtained from other sources (e.g., asset sales, the issuance of equity, etc.). Call prohibition provides the bondholder with more protection than a bond that has a refunding prohibition that is otherwise callable.1

Make-Whole Call Provision

In contrast to a standard fixed-price call, a make-whole call price is calculated as the present value of the bond’s remaining cash flows subject to a floor price equal to par value. The discount rate used to determine the present value is the yield on a comparable-maturity Treasury security plus a contractually specified make-whole call premium. For example, in November 2010, Coca-Cola sold $1 billion of 3.15% Notes due November 15, 2020. These notes are redeemable at any time either in whole or in part at the issuer’s option. The redemption price is the greater of (1) 100% of the principal amount plus accrued interest or (2) the make-whole redemption price, which is equal to the sum of the present value of the remaining coupon and principal payments discounted at the Treasury rate plus 10 basis points. The spread of 10 basis points is the aforementioned make-whole call premium. Thus the make-whole call price is essentially a floating call price that moves inversely with the level of interest rates.

The Treasury rate is calculated in one of two ways. One method is to use a constant-maturity Treasury (CMT) yield as the Treasury rate. CMT yields are published weekly by the Federal Reserve in its statistical release H.15. The maturity of the CMT yield will match the bond’s remaining maturity (rounded to the nearest month). If there is no CMT yield that exactly corresponds with the bond’s remaining maturity, a linear interpolation is employed using the yields of the two closest available CMT maturities. Once the CMT yield is determined, the discount rate for the bond’s remaining cash flows is simply the CMT yield plus the make-whole call premium specified in the indenture.

Another method of determining the Treasury rate is to select a U.S. Treasury security having a maturity comparable with the remaining maturity of the make-whole call bond in question. This selection is made by a primary U.S. Treasury dealer designated in the bond’s indenture. An average price for the selected Treasury security is calculated using the price quotations of multiple primary dealers. The average price is then used to calculate a bond-equivalent yield. This yield is then used as the Treasury rate.

Make-whole call provisions were first introduced in publicly traded corporate bonds in 1995. Bonds with make-whole call provisions are now issued routinely. Moreover, the make-whole call provision is growing in popularity while bonds with fixed-price call provisions are declining. Exhibit 12–1 presents a graph that shows the total par amount outstanding of corporate bonds issued in billions of dollars by type of bond (straight, fixed-price call, make-whole call) for years 1995 to 2009.2 This sample of bonds contains all debentures issued on and after January 1, 1995, that might have certain characteristics.3 These data suggest that the make-whole call provision is rapidly becoming the call feature of choice for corporate bonds.

EXHIBIT 12–1

Total Par Amount of Corporate Bonds Outstanding by Type of Call Provision

The primary advantage from the firm’s perspective of a make-whole call provision relative to a fixed-price call is a lower cost. Since the make-whole call price floats inversely with the level of Treasury rates, the issuer will not exercise the call to buy back the debt merely because its borrowing rates have declined. Simply put, the pure refunding motive is virtually eliminated. This feature will reduce the upfront compensation required by bondholders to hold make-whole call bonds versus fixed-price call bonds.

Sinking-Fund Provision

Term bonds may be paid off by operation of a sinking fund. These last two words are often misunderstood to mean that the issuer accumulates a fund in cash, or in assets readily sold for cash, that is used to pay bonds at maturity. It had that meaning many years ago, but too often the money supposed to be in a sinking fund was not all there when it was needed. In modern practice, there is no fund, and sinking means that money is applied periodically to redemption of bonds before maturity. Corporate bond indentures require the issuer to retire a specified portion of an issue each year. This kind of provision for repayment of corporate debt may be designed to liquidate all of a bond issue by the maturity date, or it may be arranged to pay only a part of the total by the end of the term. As an example, consider a $150 million issue by Westvaco in June 1997. The bonds carry a 7.5% coupon and mature on June 15, 2027. The bonds’ indenture provides for an annual sinking-fund payment of $7.5 million or $15 million to be determined on an annual basis.

The issuer may satisfy the sinking-fund requirement in one of two ways. A cash payment of the face amount of the bonds to be retired may be made by the corporate debtor to the trustee. The trustee then calls the bonds pro rata or by lot for redemption. Bonds have serial numbers, and numbers may be selected randomly for redemption. Owners of bonds called in this manner turn them in for redemption; interest payments stop at the redemption date. Alternatively, the issuer can deliver to the trustee bonds with a total face value equal to the amount that must be retired. The bonds are purchased by the issuer in the open market. This option is elected by the issuer when the bonds are selling below par. A few corporate bond indentures, however, prohibit the open-market purchase of the bonds by the issuer.

Many electric utility bond issues can satisfy the sinking-fund requirement by a third method. Instead of actually retiring bonds, the company may certify to the trustee that it has used unfunded property credits in lieu of the sinking fund. That is, it has made property and plant investments that have not been used for issuing bonded debt. For example, if the sinking-fund requirement is $1 million, it may give the trustee $1 million in cash to call bonds, it may deliver to the trustee $1 million of bonds it purchased in the open market, or it may certify that it made additions to its property and plant in the required amount, normally $1,667 of plant for each $1,000 sinking-fund requirement. In this case it could satisfy the sinking fund with certified property additions of $1,667,000.

The issuer is granted a special call price to satisfy any sinking-fund requirement. Usually, the sinking-fund call price is the par value if the bonds were originally sold at par. When issued at a price in excess of par, the sinking-fund call price generally starts at the issuance price and scales down to par as the issue approaches maturity.

There are two advantages of a sinking-fund requirement from the bondholder’s perspective. First, default risk is reduced because of the orderly retirement of the issue before maturity. Second, if bond prices decline as a result of an increase in interest rates, price support may be provided by the issuer or its fiscal agent because it must enter the market on the buy side in order to satisfy the sinking-fund requirement. However, the disadvantage is that the bonds may be called at the special sinking-fund call price at a time when interest rates are lower than rates prevailing at the time of issuance. In that case, the bonds will be selling above par but may be retired by the issuer at the special call price that may be equal to par value.

Usually, the periodic payments required for sinking-fund purposes will be the same for each period. Gas company issues often have increasing sinking-fund requirements. However, a few indentures might permit variable periodic payments, where the periodic payments vary based on prescribed conditions set forth in the indenture. The most common condition is the level of earnings of the issuer. In such cases, the periodic payments vary directly with earnings. An issuer prefers such flexibility; however, an investor may prefer fixed periodic payments because of the greater default risk protection provided under this arrangement.

Many corporate bond indentures include a provision that grants the issuer the option to retire more than the amount stipulated for sinking-fund retirement. This option, referred to as an accelerated sinking-fund provision, effectively reduces the bondholder’s call protection because, when interest rates decline, the issuer may find it economically advantageous to exercise this option at the special sinking-fund call price to retire a substantial portion of an outstanding issue.

Sinking fund provisions have fallen out of favor for most companies, but they used to be fairly common for public utilities, pipeline issuers, and some industrial issues. Finance issues almost never include a sinking fund provision. There can be a mandatory sinking fund where bonds have to be retired or, as mentioned earlier, a nonmandatory sinking fund in which it may use certain property credits for the sinking-fund requirement. If the sinking fund applies to a particular issue, it is called a specific sinking fund. There are also nonspecific sinking funds (also known as funnel, tunnel, blanket, or aggregate sinking funds), where the requirement is based on the total bonded debt outstanding of an issuer. Generally, it might require a sinking-fund payment of 1% of all bonds outstanding as of year-end. The issuer can apply the requirement to one particular issue or to any other issue or issues. Again, the blanket sinking fund may be mandatory (where bonds have to be retired) or nonmandatory (whereby it can use unfunded property additions).

Maintenance and Replacement Funds

Maintenance and replacement fund (M&R) provisions first appeared in bond indentures of electric utilities subject to regulation by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) under the Public Holding Company Act of 1940. It remained in the indentures even when most of the utilities were no longer subject to regulation under the act. The original motivation for their inclusion is straightforward. Property is subject to economic depreciation, and the replacement fund ostensibly helps to maintain the integrity of the property securing the bonds. An M&R differs from a sinking fund in that the M&R only helps to maintain the value of the security backing the debt, whereas a sinking fund is designed to improve the security backing the debt. Although it is more complex, it is similar in spirit to a provision in a home mortgage requiring the homeowner to maintain the home in good repair.

An M&R requires a utility to determine annually the amounts necessary to satisfy the fund and any shortfall. The requirement is based on a formula that is usually some percentage (e.g., 15%) of adjusted gross operating revenues. The difference between what is required and the actual amount expended on maintenance is the shortfall. The shortfall is usually satisfied with unfunded property additions, but it also can be satisfied with cash. The cash can be used for the retirement of debt or withdrawn on the certification of unfunded property credits.

While the retirement of debt through M&R provisions is not as common as it once was, M&Rs are still relevant, so bond investors should be cognizant of their presence in an indenture. For example, in April 2000, PPL Electric Utilities Corporation redeemed all its outstanding 9.25% coupon series first-mortgage bonds due in 2019 using an M&R provision. The special redemption price was par. The company’s stated purpose of the call was to reduce interest expense.

Redemption through the Sale of Assets and Other Means

Because mortgage bonds are secured by property, bondholders want the integrity of the collateral to be maintained. Bondholders would not want a company to sell a plant (which has been pledged as collateral) and then to use the proceeds for a distribution to shareholders. Therefore, release-of-property and substitution-of-property clauses are found in most secured bond indentures.

As an illustration, Texas–New Mexico Power Co. issued $130 million in first-mortgage bonds in January 1992 that carried a coupon rate of 11.25%. The bonds were callable beginning in January 1997 at a call price of 105. Following the sale of six of its utilities, Texas–New Mexico Power called the bonds at par in October 1995, well before the first call date. As justification for the call, Texas–New Mexico Power stated that it was forced to sell the six utilities by municipalities in northern Texas, and as a result, the bonds were callable under the eminent domain provision in the bond’s indenture. The bondholders sued, stating that the bonds were redeemed in violation of the indenture. In April 1997, the court found for the bondholders, and they were awarded damages, as well as lost interest. In the judgment of the court, while the six utilities were under the threat of condemnation, no eminent domain proceedings were initiated.

Tender Offers

In addition to those methods specified in the indenture, firms have other tools for extinguishing debt prior to its stated maturity. At any time a firm may execute a tender offer and announce its desire to buy back specified debt issues. Firms employ tender offers to eliminate restrictive covenants or to refund debt. Usually the tender offer is for “any and all” of the targeted issue, but it also can be for a fixed dollar amount that is less than the outstanding face value. An offering circular is sent to the bondholders of record stating the price the firm is willing to pay and the window of time during which bondholders can sell their bonds back to the firm. If the firm perceives that participation is too low, the firm can increase the tender offer price and extend the tender offer window. When the tender offer expires, all participating bondholders tender their bonds and receive the same cash payment from the firm.

In recent years, tender offers have been executed using a fixed spread as opposed to a fixed price.4 In a fixed-spread tender offer, the tender offer price is equal to the present value of the bond’s remaining cash flows either to maturity or the next call date if the bond is callable. The present-value calculation occurs immediately after the tender offer expires. The discount rate used in the calculation is equal to the yield-to-maturity on a comparable-maturity Treasury or the associated CMT yield plus the specified fixed spread. Fixed-spread tender offers eliminate the exposure to interest-rate risk for both bondholders and the firm during the tender offer window.

CREDIT RISK

All corporate bonds are exposed to credit risk, which includes credit default risk and credit-spread risk.

Measuring Credit Default Risk

Any bond investment carries with it the uncertainty as to whether the issuer will make timely payments of interest and principal as prescribed by the bond’s indenture. This risk is termed credit default risk and is the risk that a bond issuer will be unable to meet its financial obligations. Institutional investors have developed tools for analyzing information about both issuers and bond issues that assist them in accessing credit default risk. These techniques are discussed in later chapters. However, most individual bond investors and some institutional bond investors do not perform any elaborate credit analysis. Instead, they rely largely on bond ratings published by the major rating agencies that perform the credit analysis and publish their conclusions in the form of ratings. The three major nationally recognized statistical rating organizations (NRSROs) in the United States are Fitch Ratings, Moody’s, and Standard & Poor’s. These ratings are used by market participants as a factor in the valuation of securities on account of their independent and unbiased nature.

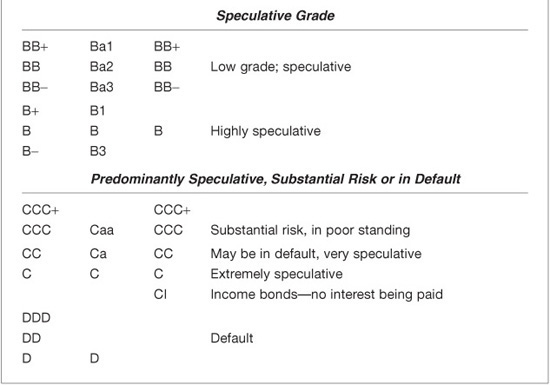

The ratings systems use similar symbols, as shown in Exhibit 12–2. In addition to the generic rating category, Moody’s employs a numerical modifier of 1, 2, or 3 to indicate the relative standing of a particular issue within a rating category. This modifier is called a notch. Both Standard & Poor’s and Fitch use a plus (+) and a minus (−) to convey the same information. Bonds rated triple B or higher are referred to as investment-grade bonds. Bonds rated below triple B are referred to as non-investment-grade bonds or, more popularly, high-yield bonds or junk bonds.

EXHIBIT 12–2

Corporate Bond Credit Ratings

Credit ratings can and do change over time. A rating transition table, also called a rating migration table, is a table that shows how ratings change over some specified time period. Exhibit 12–3 presents a hypothetical rating transition table for a one-year time horizon. The ratings beside each of the rows are the ratings at the start of the year. The ratings at the head of each column are the ratings at the end of the year. Accordingly, the first cell in the table tells that 93.20% of the issues that were rated AAA at the beginning of the year still had that rating at the end. These tables are published periodically by the three rating agencies and can be used to access changes in credit default risk.

EXHIBIT 12–3

Hypothetical One-Year Rating Transition Table

Measuring Credit-Spread Risk

The credit-spread is the difference between a corporate bond’s yield and the yield on a comparable-maturity benchmark Treasury security.5 Credit spreads are so named because the presumption is that the difference in yields is due primarily to the corporate bond’s exposure to credit risk. This is misleading, however, because the risk profile of corporate bonds differs from Treasuries on other dimensions; namely, corporate bonds are less liquid and often have embedded options.

Credit-spread risk is the risk of financial loss or the underperformance of a portfolio resulting from changes in the level of credit spreads used in the marking to market of a fixed income product. Credit spreads are driven by both macroeconomic forces and issue-specific factors. Macro-economic forces include such things as the level and slope of the Treasury yield curve, the business cycle, and consumer confidence. Correspondingly, the issue-specific factors include such things as the corporation’s financial position and the future prospects of the firm and its industry.

One method used commonly to measure credit-spread risk is spread duration. Spread duration is the approximate percentage change in a bond’s price for a 100 basis point change in the credit-spread assuming that the Treasury rate is unchanged. For example, if a bond has a spread duration of 3, this indicates that for a 100 basis point change in the credit-spread, the bond’s price should change be approximately 3%. Spread duration is discussed in Chapter 55.

EVENT RISK

In recent years, one of the more talked-about topics among corporate bond investors is event risk. Over the last couple of decades, corporate bond indentures have become less restrictive, and corporate managements have been given a free rein to do as they please without regard to bondholders. Management’s main concern or duty is to enhance shareholder wealth. As for the bondholder, all a company is required to do is to meet the terms of the bond indenture, including the payment of principal and interest. With few restrictions and the optimization of shareholder wealth of paramount importance for corporate managers, it is no wonder that bondholders became concerned when merger mania and other events swept the nation’s boardrooms. Events such as decapitalizations, restructurings, recapitalizations, mergers, acquisitions, leveraged buyouts, and share repurchases, among other things, often caused substantial changes in a corporation’s capital structure, namely, greatly increased leverage and decreased equity. Bondholders’ protection was sharply reduced and debt quality ratings lowered, in many cases to speculative-grade categories. Along with greater risk came lower bond valuations. Shareholders were being enriched at the expense of bondholders. It is important to keep in mind the distinction between event risk and headline risk. Headline risk is the uncertainty engendered by the firm’s media coverage that causes investors to alter their perception of the firm’s prospects. Headline risk is present regardless of the veracity of the media coverage.

In reaction to the increased activity of leveraged buyouts and strategic mergers and acquisitions, some companies incorporated “poison puts” in their indentures. These are designed to thwart unfriendly takeovers by making the target company unpalatable to the acquirer. The poison put provides that the bondholder can require the company to repurchase the debt under certain circumstances arising out of specific designated events such as a change in control. Poison puts may not deter a proposed acquisition but could make it more expensive. Many times, in addition to a designated event, a rating change to below investment grade must occur within a certain period for the put to be activated. Some issues provide for a higher interest rate instead of a put as a designated event remedy.

At times, event risk has caused some companies to include other special debt-retirement features in their indentures. An example is the maintenance of net worth clause included in the indentures of some lower-rated bond issues. In this case, an issuer covenants to maintain its net worth above a stipulated level, and if it fails to do so, it must begin to retire its debt at par. Usually the redemptions affect only part of the issue and continue periodically until the net worth recovers to an amount above the stated figure or the debt is retired. In other cases, the company is required only to offer to redeem a required amount. An offer to redeem is not mandatory on the bondholders’ part; only those holders who want their bonds redeemed need do so. In a number of instances in which the issuer is required to call bonds, the bondholders may elect not to have bonds redeemed. This is not much different from an offer to redeem. It may protect bondholders from the redemption of the high-coupon debt at lower interest rates. However, if a company’s net worth declines to a level low enough to activate such a call, it probably would be prudent to have one’s bonds redeemed.

Protecting the value of debt investments against the added risk caused by corporate management activity is not an easy job. Investors should analyze the issuer’s fundamentals carefully to determine if the company may be a candidate for restructuring. Attention to news and equity investment reports can make the task easier. Also, the indenture should be reviewed to see if there are any protective covenant features. However, there may be loopholes that can be exploited by sharp legal minds. Of course, large portfolios can reduce risk with broad diversification among industry lines, but price declines do not always affect only the issue at risk; they also can spread across the board and take the innocent down with them. This happened in the fall of 1988 with the leveraged buyout of RJR Nabisco, Inc. The whole industrial bond market suffered as buyers and traders withdrew from the market, new issues were postponed, and secondary market activity came to a standstill. The impact of the initial leveraged buyout bid announcement on yield spreads for RJR Nabisco’s debt to a benchmark Treasury increased from about 100 to 350 basis points. The RJR Nabisco transaction showed that size was not an obstacle. Therefore, other large firms that investors previously thought were unlikely candidates for a leveraged buyout were fair game. The spillover effect caused yield spreads to widen for other major corporations. This phenomenon was repeated in the mid-2000s with the buyout of large, investment grade public companies such as Alltel, First Data, and Hilton Hotels.

HIGH-YIELD BONDS

As noted, high-yield bonds are those rated below investment grade by the ratings agencies. These issues are also known as junk bonds. Despite the negative connotation of the term junk, not all bonds in the high-yield sector are on the verge of default or bankruptcy. Many of these issues are on the fringe of the investment-grade sector.

Types of Issuers

Several types of issuers fall into the less-than-investment-grade high-yield category. These categories are discussed below.

Original Issuers

Original issuers include young, growing concerns lacking the stronger balance sheet and income statement profile of many established corporations but often with lots of promise. Also called venture-capital situations or growth or emerging market companies, the debt is often sold with a story projecting future financial strength. From this we get the term story bond. There are also the established operating firms with financials neither measuring up to the strengths of investment-grade corporations nor possessing the weaknesses of companies on the verge of bankruptcy. Subordinated debt of investment-grade issuers may be included here. A bond rated at the bottom rung of the investment-grade category (Baa and BBB) or at the top end of the speculative-grade category (Ba and BB) is referred to as a “businessman’s risk.”

Fallen Angels

“Fallen angels” are companies with investment-grade-rated debt that have come on hard times with deteriorating balance sheet and income statement financial parameters. They may be in default or near bankruptcy. In these cases, investors are interested in the workout value of the debt in a reorganization or liquidation, whether within or outside the bankruptcy courts. Some refer to these issues as “special situations.” Over the years, they have fallen on hard times; some have recovered, and others have not.

Restructurings and Leveraged Buyouts

These are companies that have deliberately increased their debt burden with a view toward maximizing shareholder value. The shareholders may be the existing public group to which the company pays a special extraordinary dividend, with the funds coming from borrowings and the sale of assets. Cash is paid out, net worth decreased, and leverage increased, and ratings drop on existing debt. Newly issued debt gets junk-bond status because of the company’s weakened financial condition.

In a leveraged buyout (LBO), a new and private shareholder group owns and manages the company. The debt issue’s purpose may be to retire other debt from commercial and investment banks and institutional investors incurred to finance the LBO. The debt to be retired is called bridge financing because it provides a bridge between the initial LBO activity and the more permanent financing. One example is Ann Taylor, Inc.’s 1989 debt financing for bridge loan repayment. The proceeds of BCI Holding Corporation’s 1986 public debt financing and bank borrowings were used to make the required payments to the common shareholders of Beatrice Companies, pay issuance expenses, and retire certain Beatrice debt and for working capital.

Unique Features of Some Issues

Often actions taken by management that result in the assignment of a non-investment-grade bond rating result in a heavy interest-payment burden. This places severe cash-flow constraints on the firm. To reduce this burden, firms involved with heavy debt burdens have issued bonds with deferred coupon structures that permit the issuer to avoid using cash to make interest payments for a period of three to seven years. There are three types of deferred-coupon structures: (1) deferred-interest bonds, (2) step-up bonds, and (3) payment-in-kind bonds.

Deferred-interest bonds are the most common type of deferred-coupon structure. These bonds sell at a deep discount and do not pay interest for an initial period, typically from three to seven years. (Because no interest is paid for the initial period, these bonds are sometimes referred to as “zero-coupon bonds.”) Step-up bonds do pay coupon interest, but the coupon rate is low for an initial period and then increases (“steps up”) to a higher coupon rate. Finally, payment-in-kind (PIK) bonds give the issuers an option to pay cash at a coupon payment date or give the bondholder a similar bond (i.e., a bond with the same coupon rate and a par value equal to the amount of the coupon payment that would have been paid). The period during which the issuer can make this choice varies from five to ten years.

Sometimes an issue will come to market with a structure allowing the issuer to reset the coupon rate so that the bond will trade at a predetermined price.6 The coupon rate may reset annually or even more frequently, or reset only one time over the life of the bond. Generally, the coupon rate at the reset date will be the average of rates suggested by two investment banking firms. The new rate will then reflect (1) the level of interest rates at the reset date and (2) the credit-spread the market wants on the issue at the reset date. This structure is called an extendible reset bond.

Notice the difference between an extendible reset bond and a typical floating-rate issue. In a floating-rate issue, the coupon rate resets according to a fixed spread over the reference rate, with the index spread specified in the indenture. The amount of the index spread reflects market conditions at the time the issue is offered. The coupon rate on an extendible reset bond, in contrast, is reset based on market conditions (as suggested by several investment banking firms) at the time of the reset date. Moreover, the new coupon rate reflects the new level of interest rates and the new spread that investors seek.

The advantage to investors of extendible reset bonds is that the coupon rate will reset to the market rate—both the level of interest rates and the credit-spread—in principle keeping the issue at par value. In fact, experience with extendible reset bonds has not been favorable during periods of difficulties in the high-yield bond market. The sudden substantial increase in default risk has meant that the rise in the rate needed to keep the issue at par value was so large that it would have insured bankruptcy of the issuer. As a result, the rise in the coupon rate has been insufficient to keep the issue at the stipulated price.

Some speculative-grade bond issues started to appear in 1992 granting the issuer a limited right to redeem a portion of the bonds during the noncall period if the proceeds are from an initial public stock offering. Called “clawback” provisions, they merit careful attention by inquiring bond investors. The provision appears in the vast majority of new speculative-grade bond issues, and sometimes allow even private sales of stock to be used for the clawback. The provision usually allows 35% of the issue to be retired during the first three years after issuance, at a price of par plus one year of coupon. Investors should be forewarned of clawbacks because they can lose bonds at the point in time just when the issuer’s finances have been strengthened through access to the equity market. Also, the redemption may reduce the amount of the outstanding bonds to a level at which their liquidity in the aftermarket may suffer.

DEFAULT RATES AND RECOVERY RATES

We now turn our attention to the various aspects of the historical performance of corporate issuers with respect to fulfilling their obligations to bondholders. Specifically, we will look at two aspects of this performance. First, we will look at the default rate of corporate borrowers. From an investment perspective, default rates by themselves are not of paramount significance; it is perfectly possible for a portfolio of bonds to suffer defaults and to outperform Treasuries at the same time, provided the yield spread of the portfolio is sufficiently high to offset the losses from default. Furthermore, because holders of defaulted bonds typically recover some percentage of the face amount of their investment, the default loss rate is substantially lower than the default rate. Therefore, it is important to look at default loss rates or, equivalently, recovery rates.

Default Rates

A default rate can be measured in different ways. A simple way to define a default rate is to use the issuer as the unit of study. A default rate is then measured as the number of issuers that default divided by the total number of issuers at the beginning of the year. This measure gives no recognition to the amount defaulted nor the total amount of issuance. Moody’s, for example, uses this default-rate statistic in its study of default rates.7 The rationale for ignoring dollar amounts is that the credit decision of an investor does not increase with the size of the issuer. The second measure is to define the default rate as the par value of all bonds that defaulted in a given calendar year divided by the total par value of all bonds outstanding during the year. Edward Altman, who has performed extensive analyses of default rates for speculative-grade bonds, measures default rates in this way. We will distinguish between the default-rate statistic below by referring to the first as the issuer default rate and the second as the dollar default rate.

With either default-rate statistic, one can measure the default for a given year or an average annual default rate over a certain number of years. Researchers who have defined dollar default rates in terms of an average annual default rate over a certain number of years have measured it as

![]()

Alternatively, some researchers report a cumulative annual default rate. This is done by not normalizing by the number of years. For example, a cumulative annual dollar default rate is calculated as

![]()

There have been several excellent studies of corporate bond default rates. We will not review each of these studies because the findings are similar. Here we will look at a study by Moody’s that covers the period 1970 to 1994.8 Over this 25-year period, 640 of the 4,800 issuers in the study defaulted on more than $96 billion of publicly offered long-term debt. A default in the Moody’s study is defined as “any missed or delayed disbursement of interest and/or principal.” Issuer default rates are calculated. The Moody’s study found that the lower the credit rating, the greater is the probability of a corporate issuer defaulting.

There have been extensive studies focusing on default rates for speculative-grade issuers. In their 2011 study, Altman and Kuehne find based on a sample of high-yield bonds outstanding over the period 1971–2010, default rates typically range between 2% and 5% with occasional spikes above 10% during periods of financial dislocation.9

Recovery Rates

There have been several studies that have focused on recovery rates or default loss rates for corporate debt. Measuring the amount recovered is not a simple task. The final distribution to claimants when a default occurs may consist of cash and securities. Often it is difficult to track what was received and then determine the present value of any noncash payments received.

While the empirical record is developing, we will state a few stylized facts about recovery rates and by implication default rates.10

• The average recovery rate of bonds across seniority levels is approximately 38%.

• The distribution of recovery rates is bimodal.

• Recovery rates are unrelated to the size of the bond issuance.

• Default rates and recovery rates are inversely correlated.

• Recovery rate is lower in an economic downturn and in a distressed industry.

• Tangible asset-intensive industries have higher recovery rates.

MEDIUM-TERM NOTES

Medium-term notes (MTNs) are debt instruments that differ primarily in how they are sold to investors. Akin to a commercial paper program, they are offered continuously to institutional investors by an agent of the issuer. MTNs are registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission under Rule 415 (“shelf registration”) which gives a corporation sufficient flexibility for issuing securities on a continuous basis. MTNs are also issued by non-U.S. corporations, federal agencies, supranational institutions, and sovereign governments.

One would suspect that MTNs would describe securities with intermediate maturities. However, it is a misnomer. MTNs are issued with maturities of 9 months to 30 years or even longer. For example, in 1993, Walt Disney Corporation issued bonds through its medium-term note program with a 100-year maturity a so-called century bond. MTNs can perhaps be more accurately described as highly flexible debt instruments that can easily be designed to respond to market opportunities and investor preferences.

As noted, MTNs differ in their primary distribution process. Most MTN programs have two to four agents. Through its agents, an issuer of MTNs posts offering rates over a range of maturities: for example, nine months to one year, one year to eighteen months, eighteen months to two years, and annually thereafter. Many issuers post rates as a yield spread over a Treasury security of comparable maturity.

Relatively attractive yield spreads are posted for maturities that the issuer desires to raise funds. The investment banks disseminate this offering rate information to their investor clients. When an investor expresses interest in an MTN offering, the agent contacts the issuer to obtain a confirmation of the terms of the transaction. Within a maturity range, the investor has the option of choosing the final maturity of the note sale, subject to agreement by the issuing company. The issuer will lower its posted rates once it raises the desired amount of funds at a given maturity.

Structured medium-term notes or simply structured notes are debt instruments coupled with a derivative position (options, forwards, futures, swaps, caps, and floors). For example, structured notes are often created with an underlying swap transaction. This “hedging swap” allows the issuer to create structured notes with interesting risk/return features desired by a swath of fixed income investors.

KEY POINTS

• A bond’s indenture includes the promises of corporate bond issuers and the rights of investors. The terms of bond issues set forth in bond indentures are always a compromise between the interests of the bond issuer and those of investors who buy bonds.

• The classification of corporate bonds by type of issuer include public utilities, transportations, industrials, banks and finance companies, and international or Yankee issues.

• The three main interest payment classifications of domestically issued corporate bonds are straight-coupon bonds (fixed-rate bonds), zero-coupon bonds, and floating-rate bonds (variable-rate bonds).

• Either real property (using a mortgage) or personal property may be pledged to offer security beyond that of the general credit standing of the issuer. In fact, the kind of security or the absence of a specific pledge of security is usually indicated by the title of a bond issue. However, the best security is a strong general credit that can repay the debt from earnings.

• A mortgage bond grants the bondholders a first-mortgage lien on substantially all its properties and as a result the issuer is able to borrow at a lower rate of interest than if the debt were unsecured.

• Some companies do not own fixed assets or other real property and so have nothing tangible on which they can give a mortgage lien to secure bondholders. To satisfy the desire of bondholders for security, they pledge stocks, notes, bonds, or whatever other kinds of obligations they own and the resulting issues are referred to as collateral trust bonds.

• Debentures not secured by a specific pledge of designated property and therefore bondholders have the claim of general creditors on all assets of the issuer not pledged specifically to secure other debt. Moreover, debenture bondholders have a claim on pledged assets to the extent that these assets have value greater than necessary to satisfy secured creditors. In fact, if there are no pledged assets and no secured creditors, debenture bondholders have first claim on all assets along with other general creditors.

• Owners of subordinated debenture bonds stand last in line among creditors when an issuer fails financially.

• For a guaranteed bond there is a third party guaranteeing the debt but that does not mean a bond issue is free of default risk. The safety of a guaranteed bond depends on the financial capability of the guarantor to satisfy the terms of the guarantee, as well as the financial capability of the issuer.

• Debt retirement mechanisms included in a bond’s indenture are call and refunding provisions, sinking funds, maintenance and replacement funds, redemption through sale of assets, and tender offers.

• All corporate bonds are exposed to credit risk, which includes credit default risk and credit-spread risk.

• Credit ratings can and do change over time and this information is captured in a rating transition table, also called a rating migration table.