Chapter 1

Getting Started

Key Skills & Concepts

• Understand the Internet as a Medium for Disseminating Information

• Be Aware of the Current Version of HTML

• Plan for the Audience, Goals, Structure, Content, and Navigation of Your Site

• Identify the Best HTML Editor for You

• Learn from the Pros Using the View Source Command of Popular Web Browsers

For as long as I’ve been involved in making web pages, people have asked me to teach them the process. At the start, many are intimidated by the thought of learning HTML. But fear not! After all, one of the reasons I decided to attend art school was to avoid all the math and science classes. So, as I tell my students … if I could learn HTML, so can you.

HTML is not rocket science. Quite simply, it is a means of telling a web browser how to display a page. That’s why it’s called HTML, which is the acronym for Hypertext Markup Language. Like any new skill, HTML takes practice to comprehend what you are doing.

Before we dive into the actual creation of web pages, you must first understand a few things about the Internet. I could probably fill an entire book with the material in this initial chapter, but the following should provide you with a firm foundation.

Understand the Internet as a Medium for Disseminating Information

When you’re asked to write a term paper in school, you don’t sit down and just start writing. First, you have to do research and learn how to format the paper. The process for writing and designing a web page is similar.

The Anatomy of a Web Site

Undoubtedly, you’ve seen more than a few web sites by now. Perhaps you know someone who’s a skilled web navigator, and you’ve watched him surf through a web site by chopping off pieces of the web address. Have you ever wondered what he’s doing? It’s not too difficult. He just knows a little about the anatomy of a web site and how the underlying structure is laid out.

URLs

The fancy word for “web address” is uniform resource locator, also referenced by its acronym URL (pronounced either by the letters U-R-L or as a single word, url, which rhymes with “girl”). Even if you’ve never heard a web address referred to as a URL, you’ve probably seen one—URLs start with http://, and they usually end with .com, .org, .edu, or .net. (Other possibilities include .tv, .biz, and .info. For more information, see www.networksolutions.com.)

Every web site has a URL—for instance, Google’s is www.google.com. The following illustration shows another example of a URL as it appears in a common web browser (Firefox) on the Mac.

The first part of the URL is commonly referred to as a protocol or scheme. In the previous illustration, HTTP was the scheme used. HTTP stands for Hypertext Transfer Protocol, and tells the browser how to access the rest of the URL. In this case, HTTP specifies the browser should display the file using hypertext.

HTTPS is another common scheme, and indicates the browser should connect securely to the server before displaying the content.

The next significant part of a URL is the domain, which helps identify and locate computers on the Internet. To avoid confusion, each domain name is unique. You can think of the domain name as a label or shortcut. Behind that shortcut is a series of numbers, called an IP address, that gives the specific address of where the site you’re looking for is located on the Internet. To draw an analogy, if the domain name is the word “Emergency” written next to the first-aid symbol on your speed dial, the IP address is 9-1-1.

NOTE

Although many URLs begin with “www,” this is not a necessity (depending on how the server is set up). Originally used to denote “World Wide Web” in the URL, using www caught on as common practice. The characters before the first period in the URL are not part of the registered domain and can be almost anything. In fact, many businesses use this part of the URL to differentiate between various departments within the company. For example, the GO Network includes ABC, ESPN, and Disney, to name a few. Each of these is a department of go.com: abc.go.com, espn.go.com, and disney.go.com. Type www.abc.com in the address bar of your favorite web browser, and you’ll notice the URL changes to abc.go.com. That’s because www.abc.com is an alias—or a shortcut—for abc.go.com.

Businesses typically register domain names ending in a .com (which signifies a commercial venture) that are similar to their business or product name. Domain registration is like renting office space on the Internet. Once you register a domain name, you have the right to publish a web site under that name on the Internet for as long as you pay the rental fees.

TIP

Wondering whether yourname.com is already being used? You can check to see which domain names are still available for registration by visiting a registration service like www.godaddy.com or www.networksolutions.com.

The rest of the address contains the exact path to the specific file on the server being displayed. For example, when I visit http://www.fox.com/glee/recaps, I am viewing the content from Fox housed in the “recaps” folder, which is then housed in the “glee” folder on the web server. Here, the slashes separate the domain from each folder name.

Web Servers

Every web site and web page also needs a web server. Quite simply, a web server is a computer, running special software, that is always connected to the Internet.

NOTE

Some people talk about the computer as the server, as in “We need to buy a new server.” Others call the software the server, saying “We need to install a new web server.” Both uses of the word essentially refer to the same thing—web servers make information available to those requesting it.

When you type a URL into your web browser or click a link in a web page, you send a request to the server housing that information. It’s similar to the process that occurs when you dial a phone number with your telephone. Your request “calls” the computer that contains all the files necessary to show you the web page you requested. The computer then “serves” and displays all the pages to you, usually in your web browser.

Ask the Expert

Q: I’ve heard the phrase “the World Wide Web” used so many times, but I’m a little confused about what it actually means and how it relates to the Internet.

A: The World Wide Web (WWW or the Web) is often confused with the Internet. The actual term “Internet” was first used in the early 1970s, when academic research institutions developed a way to connect computers to create better communication and to share resources. Later, universities and research facilities throughout the world began using the Internet. In the early 1990s, Tim Berners-Lee created a set of technologies that allowed information on the Internet to be connected through the use of links in documents. The language component of these technologies is Hypertext Markup Language (HTML). If you want to find out more, a good resource on the history of the Internet is available at http://www.internetsociety.org//internet/internet-51/history-internet.

The Web was mostly text-based until a division at the National Center for Supercomputing Applications (NCSA) created the first graphical web browser in 1993. Called Mosaic, this paved the way for the use of video, sound, and photos, and many other aspects of the modern web browser. As a large group of interconnected computers all over the world, the Internet comprises not only the Web, but also things like newsgroups (online bulletin boards) and e-mail. Many people think of the Web as the graphical or illustrated part of the Internet.

Sites

A URL is commonly associated with a web site. You’ve doubtless seen plenty of examples of such addresses on billboards and in television advertising. For instance, www.amazon.com is the URL for Amazon’s web site, while www.cbs.com is the URL for CBS.

Most commonly, these sites are located in directories or folders on the server, just as you might have your C: drive on your personal computer. Then, within this main site, there may be several folders that house other sections of the web site.

For example, Chop Point is a summer camp and K–12 school in Maine. If you look at the URL for Chop Point Camp’s “about us” section, you can see the name of the folder after the site name:

If you access the main page for the enrollment section, the URL changes to:

Pages

When you visit a web site, you look at pages on the site that contain all its text, graphics, sound, and video content. Even though a web page is not the same size or format as a printed page, the word “page” is used to help us differentiate among pages, folders, and sites. The same way that many pages and chapters can be contained within a single book, many pages and folders (or sections) can also be kept within a web site.

Most web servers are set up to look automatically for a page called “index” as the main page in any folder. So if you were to type in the URL used in the previous example, the server would look for the index page in the “about” folder, which might look like the following:

If you want to look for a different page in the about folder, you could type the name of that page after the site and folder names, keeping in mind that HTML pages usually end with .html or .htm, such as in:

NOTE

Sites built on content management systems like Wordpress typically use a different type of file naming convention than the traditional structure I’ve outlined here. The latest version of Chop Point Camp’s site uses Wordpress, and therefore doesn’t default to index.html pages like those mentioned here. We’ll talk about Wordpress later, but at this point just keep in mind there are a variety of file naming conventions currently in use.

Web Browsers

A web browser is a piece of software that runs on your personal computer and enables you to view web pages. Web browsers, often simply called “browsers,” interpret the HTML code and provide a visual layout displayed on the screen. Browsers typically can also be used to check web-based e-mail and access newsgroups.

The most popular browsers are Microsoft Internet Explorer (also called IE), Google Chrome, and Firefox. In previous years, IE garnered as much as 65 percent of the market share. But as of this writing, the three browsers I mentioned each enjoy roughly 25 percent of the market. The remaining quarter is divided among Safari (Apple’s default browser), Opera, Android, and other miscellaneous browsers.

TIP

To keep current on statistics about browser use, visit http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Usage_share_of_web_browsers.

Browsers are updated regularly, changing to address new aspects of HTML or emerging technologies. Some people continue to use older versions of their browsers, however. This means that at any given time there may be two or three active versions of one browser and several different versions of other browsers being employed by the general public.

What if there were several versions of televisions that all displayed TV programs differently? If this were true, then your favorite television show might look different every time you watched it on someone else’s television. This would not only be frustrating to you as a viewer, it would also be frustrating for the show’s creator.

Web developers must deal with this frustration every day. Because of the differences among various browsers and the large number of computer types, the look and feel of a web page can vary greatly. This means web developers must keep up-to-date on the latest features of the new browser versions, but we must also know how to create web pages that are backward-compatible for the older browsers many people may still be using.

TIP

Most browsers can be easily customized, meaning you can change the text sizes, styles, and colors, as well as the first page that appears when you start your browser. This is usually called your “home” page or your “start” page, and it’s the page displayed when you click the “home” button in your browser. For easier access, many people change their home page to a search engine or a news site customized according to their needs. These personalized sites are often called portals and also offer free e-mail to users. A few examples are Yahoo!, Google, and MSN.

Internet Service Providers

You use an Internet service provider (ISP) to gain access to the Internet. Traditionally, this connection is made through your wired phone line with a company like Verizon or AT&T, or you can connect through a cable line with a company like Comcast or Time Warner.

With the rise of high-speed wireless options, many users access the Internet via wireless broadband connections, either on their phone or through a small device that plugs into a Universal Serial Bus (USB) port, called a dongle. Verizon, Clearwire, Xanadoo, and CLEAR are just a few of the many companies offering high-speed wireless service in the United States.

Regardless of which connection method you choose, the company providing that service is called your ISP. Many ISPs offer you a choice of browsers, and may even provide a particular web browser customized with quick links for things like checking your e-mail and reading local news.

Be Aware of the Current Version of HTML

In its earliest years, HTML quickly went through much iteration, which led to a lack of standardization across the Internet. The World Wide Web Consortium (W3C—www.w3.org) stepped in and began publishing a list of recommendations, called standards, for HTML and other web languages. The last official standard for HTML was HTML 4.01 in 1999.

In an attempt to move the standards away from the old-style HTML and closer to a more flexible language, Extensible Markup Language (XML), the W3C rewrote the standard in 2000. The resulting set of standards, called Extensible Hypertext Markup Language (XHTML), provided a way for HTML to handle alternative devices, such as cell phones and handheld computers.

XHTML 1.0 offered many new features to make the lives of web developers easier, but it was poorly supported by web browsers at its launch in 2001. It was much stricter and had little tolerance for sloppy HTML. In the years immediately following, the W3C updated its recommendation to XHTML 2.0. However, the world didn’t adopt XML as quickly or as warmly as the W3C had anticipated, and the organization ended up switching gears.

In 2008, the W3C released a working draft of the future of hypertext markup: HTML5. Since then, even though HTML5 has been a consistent “work in progress,” the modern browser creators have worked to incorporate as many features as possible. (You can check the status of HTML5 on the W3C’s web site: www.w3c.org/TR/html5.)

Unlike XHTML, HTML5 is intended to allow the best of HTML and XML simultaneously. The development team has been studying the modern use of HTML and its content in an effort to create code standards that will carry us easily into the next generation of the Web.

Previously we needed plug-ins like Flash and QuickTime—which essentially are stopgaps—to do the things HTML wasn’t able to accomplish. Now the combination of HTML, cascading style sheets (CSS), and JavaScript, working together as HTML5, is capable of just about anything web designers and developers need.

Although the standard is technically still in development (as of this writing), plenty of the new features are now supported by the major browsers. I will call attention to those as needed throughout the course of this book, but here are a few highlights:

• More intuitive structure The latest revision offers new HTML elements that make it easier to group related content and structure pages, among other things.

• Better portability It is easier to port your pages from one device to another, whether the content consists of text, images, animation, and interactivity, or a combination of each.

• Next-generation forms HTML5 enables us to create much more interactive and user-friendly forms, both in desktop browsers as well as mobile versions.

• Rich media Speaking of animation and interactivity, HTML removes the need for plug-ins to handle dynamic images. (And yes, this means HTML5 is now a competitor of Flash.)

• Audio and video Embedding audio and video in HTML pages used to be quite a chore. Thankfully the new spec adds elements to easily embed—and style!—both.

You can read more about the specific differences at www.w3.org/TR/2008/WD-html5-diff-20080610.

Plan for the Audience, Goals, Structure, Content, and Navigation of Your Site

In addition to learning about the medium, you need to do the following:

• Identify your target audience.

• Set goals for your site.

• Create your web site’s structure.

• Organize your web site’s content.

• Develop your web site’s navigation.

Identify the Target Audience

If you are creating a web site for a business, a group, or an organization, you are most likely targeting people who might buy or use the company’s products or services. Even if your site is set up purely for the purpose of disseminating information, you must target a certain audience. Consider whether you have existing research regarding your client or user base. This might include demographics, statistics, or other marketing information, such as age, gender, and web experience.

TIP

If your site represents a new company or one that doesn’t already have information about its clients’ demographics, you might check out the competition. Chances are good that if your competition has a successful web site, you can learn from them about your target audience.

Knowing your target audience will influence how you design and develop your web site. For example, if you are developing a site for beginners to learn about the Internet, you want to create a site that is extremely easy to use and does not stray from standard computer conventions. If your site targets teens and young adults, you can expect lots of visits from mobile phone and tablet devices.

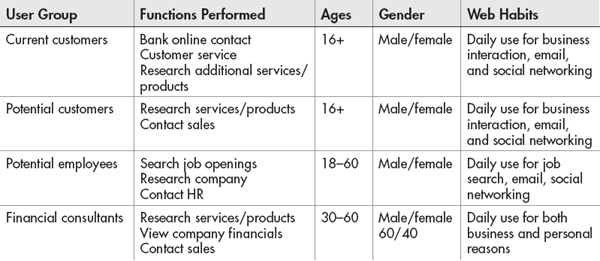

Once you identify your target audience, you need to think about what functions each part of that audience can perform at your site. Try drawing up a chart like Table 1-1 to make your plans. The example in the table is designed for a bank, but you can use it as a starting point for any site you create.

Table 1-1 Functions Performed by a Target Audience

You can use this information to determine the appropriate direction for the site. For new sites, consider taking it a step further to identify a few sample customers in each category. To do so, give your pretend customer a name, age, job, and location, and then specify his or her brand preferences, Internet usage, and what influences and inhibits him.

You might also specify whether he is an “accidental tourist” or a “navy seal” type of visitor. Most sites have a little of both. Have you ever surfed a certain site and then wondered how you got there from here? This is the “accidental tourist,” aka the serendipitous visitor. At the other end of the spectrum is the student on a mission—looking for a specific piece of information for a homework assignment. I call these the “navy seals.”

TIP

Does your site target mostly “navy seal” visitors? These individuals prefer search engines, especially when trying to locate information quickly. Providing a good search engine or site map on your site can greatly increase your repeat visitors.

This type of detailed user information can give extremely beneficial insights to any developer working on the project.

Set Goals

Since the Web’s inception, millions of new web sites have been created. To compete in such a large market, you need to set clear goals for the site that meet the needs of the target audience. For instance, the site might

• Sell products/services

• Recruit potential employees

• Entertain

• Educate

• Communicate with customers

Always remember the goals when developing the site to avoid unnecessary content. If a page or section of content on your site doesn’t meet one of the goals, it may confuse or turn away visitors.

Create the Structure

Once you align your site’s goals with the functions performed by the target audience, you will see a structure forming. Consider a site whose primary goal is to sell office supplies to businesses and whose secondary goal is to recruit potential employees. This site would most likely contain two main topic areas: shop for office supplies and browse available jobs.

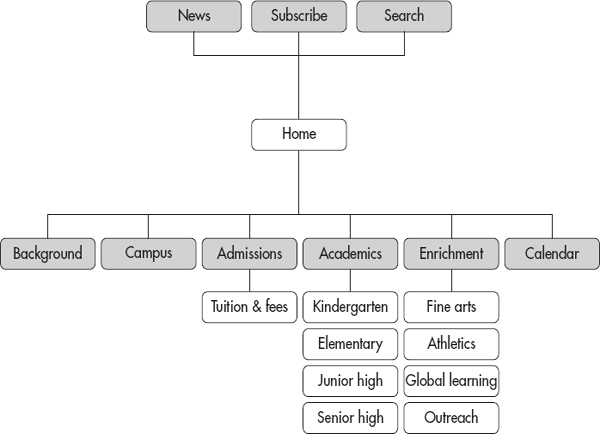

Many people use tree diagrams, such as the one shown in Figure 1-1, to help define the structure of the site. Others use flow charts, wire frames, or simple outlines.

Figure 1-1 A tree diagram showing the structure for a sample school web site

Organize Content

All the content for the site should fit under each of the topic areas in the site structure, and you might have several subcategories in each topic area. So, the “Enrichment” section from the preceding example might be broken down into several subcategories, according to the different types of programs available. Table 1-2 shows how the category names might relate to the folder names.

Table 1-2 Content Organization

Develop Navigation

After the site structure has been defined and the content has been placed into the structure accordingly, you will want to plan out how a visitor to this site navigates between each of the pages and sections. A good practice is to include a standard navigation bar on all pages for consistency and ease of use. This navigation bar probably should include links to your home page and any major topic areas. It should probably also contain the name of your business or a logo so that a simple visual clue lets the user know she has not moved beyond your site by accident.

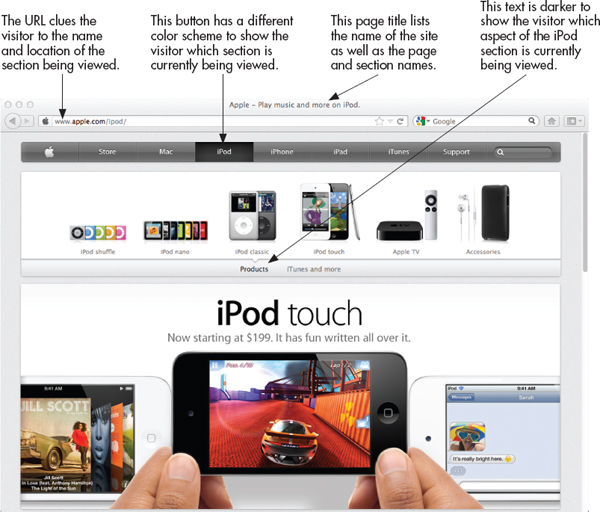

Many sites also offer an additional level of navigation, usually to content related to the currently active section. Highlighting the current section on the navigation bar is important so visitors can more easily distinguish where they are in your site’s structure. This means if your site has two sections—jobs and résumés—the jobs button would look different when you were inside that section and, in some way, should identify it as the current section.

In addition, consider giving your visitors as many visual clues as possible to aid in the navigation of your site (see Figure 1-2). This might be accomplished by repeating the page name in:

Figure 1-2 Apple’s site gives the user plenty of visual clues to aid in navigation.

• The page’s title (the text that appears at the top of the browser window, as well as in search engines)

• The page’s filename

• A headline

• Buttons and links to the page (highlighted if you are viewing that page)

Identify the Best HTML Editor for You

At some point, you may wonder: “Why go to the trouble of learning HTML if I can use a program that does it for me?” With so many new software packages available to help you develop HTML, that’s a valid question. We’ll discuss the pros and cons of each type after reviewing the features of some of the most common editors in Table 1-3. This is by no means an exhaustive list of valid HTML editors. It is merely meant to help get you started by pointing out the key benefits of each.

Table 1-3 Common Tools Used to Edit HTML

After reviewing Table 1-3, you likely noticed that most tools fall into one of two categories. First, text-based editors require you to know some HTML to use them. They can be customized to help speed your coding process, and often have sophisticated checks and balances in place to check for errors in coding. Hundreds, if not thousands, of editors exist. I’ve listed a few of the most popular text-based HTML editors here, and I encourage you to try out a few before settling on one.

Second, WYSIWYG editors don’t require knowledge of HTML. Instead of looking only at the HTML code of your pages, you have the option to view a “preview” of how the page will look in a browser. This way, you can simply drag and drop pieces of your layout as you see fit. These types of programs can have some drawbacks, but they can also be quite useful for the purposes of learning different aspects of HTML or for quickly publishing a basic web page.

Which Is Best?

Some web developers prefer to use the text-based HTML editors rather than have a WYSIWYG editor do it for them, for the following reasons:

• Better control WYSIWYG editors may write HTML in a variety of ways—although not all of them will have the same outcome. This means your pages can look different in each browser. Unfortunately, this has caused some older WYSIWYG programs to be labeled “WYSINWYG” or What-You-See-Is-Not-What-You-Get.

• Faster pages WYSIWYG editors sometimes overcompensate for the amount of code needed to render a page properly, and so they end up repeating code more times than necessary. This leads to large file sizes and longer downloads.

• Speedier editing The large-scale WYSIWYG editors can take a lot of memory and system resources, slowing both the computer and the development process.

• More flexibility Some older WYSIWYG editors are programmed to “fix” code they think is faulty. This may make you unable to insert code or edit the existing code as you wish.

That said, modern WYSIWYG editors have come a long way in terms of control and flexibility. Those developers who sing their praises typically make the following comments:

• Preview WYSIWYG editors allow you to preview your pages within the HTML editor, which means you get an idea of how the page is shaping up even before switching to the browser view.

• Drag-and-drop editing Because WYSIWYG editors have previewing tools, you can actually edit your HTML by dragging and dropping elements throughout the page.

• Advanced inline edition Tools like Dreamweaver offer the capability to code extras beyond static HTML, like CSS, Dynamic HTML (DHTML), and JavaScript, all within the same visual editor used to code basic HTML.

• Best of both worlds With the ability to dig right into the code and still see a visual representation of the output, it’s no surprise that editors like Dreamweaver have become so popular.

Quick confession time: If I sound a bit biased toward Dreamweaver, that’s because I am. I find it does everything I need an HTML editor to do, while still giving me ultimate control over my code. In addition, its companion tool—Contribute—allows me to give access to certain aspects of the web pages to clients, so they can maintain their own pages without altering the underlying structure or format of the site.

In the end, both text-based HTML editors and WYSIWYG editors have their benefits. My recommendation is to download free trials of the various programs and decide for yourself which one works best for your needs.

To achieve the goals of this book, you are free to use any editor or software package you like, provided it gives you access to the source code. To begin, I recommend you use the basic text editor that came with your computer system, such as SimpleText or TextEdit (Mac) or Notepad (Windows). Once you have the basics of HTML down, you can move on and experiment with other available programs.

Learn from the Pros Using the View Source Command of Popular Web Browsers

One of the best ways to learn HTML is to surf the Web and look at the HTML for sites you like (as well as those you don’t like). Most web browsers enable you to view the HTML source code of web pages (as shown in Figure 1-3), using the following commands:

Figure 1-3 Viewing the source of a web page allows you to see the HTML code used to create it.

• In your favorite web browser, bring up the page whose source you would like to view.

• In Chrome, choose View | Developer | View Source. In Firefox or Mozilla, right-click and select View Page Source. In IE, choose View | Source or Page | Source.

• In Safari, you must first choose Safari | Preferences | Advanced and check the option to Show Develop menu in menu bar. Then, choose Develop | Show Page Source.

You’ll notice there are often additional types of code visible. For example, aside from standard HTML code, you might also find references to other files on the server, or even other types of scripts or code altogether. Furthermore, what you’re seeing in the View Source display is only what has been sent by the server for the browser to display. This means there may have been other code used to actually tell the server where to get this code, when to send it, or even how to send it.

If you’d like, you can print or save these pages to review at a later time or to keep in a reference library. Because the Web is open source, meaning your code is free for anyone to see, copying other developers’ code is tempting. But remember, you should give credit where credit is due and never copy anything protected by a copyright, such as graphics and text content.

NOTE

A few browsers don’t let you use View Source. If you find you cannot view the HTML source of a web page, try saving the page to your local hard drive, and then opening it in a text editor instead.

| Try This 1-1 | Develop a Web Site |

The best way to practice HTML is to develop web sites. While developing a personal site might be fun, I think you can sometimes learn more about the whole development process by working on a site for a business or organization. In fact, volunteering your time to develop a web site for a nonprofit organization or a start-up business is a wonderful way to start.

Throughout the course of this book, I’ll give you projects that relate to the development of such a web site. If you already have an organization or business in mind for which you want to develop a site, then use that one. If not, you can follow along while I start a site for a friend’s online tutoring business, and customize it as you see fit.

This specific project takes you through the planning phase of the web development project. Goals for this project include

• Identifying your target audience

• Setting goals for your site

• Creating your web site’s structure

• Organizing your web site’s content

• Developing your web site’s navigation

1. Spend some time researching your organization. Try to learn as much about its business as possible. If you know people within the company, do some interviews to help you identify your target audience, as well as the site goals. If you can’t speak with them, visit other similar sites to determine what type of people the competition is targeting. Some questions to ask and things to consider include

• What business issues or problem(s) will the web site address? What do you want to accomplish? What are your goals for the web site?

• Who are the targeted users/visitors of the site? Do you have any existing research regarding your client or user base, such as demographics, statistics, or other marketing information?

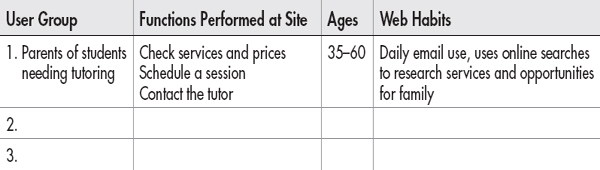

• To determine the appropriate direction for the site, you must match the targeted users and the functions they will perform when visiting the site. For example, will the targeted users be “accidental tourists” directed to the site by an advertisement, or potential investors looking for the financials? How do the audience demographics affect this? (You can use a table like the following to help you plan the targeted users and the functions they might perform at the site.)

2. Pull out one or two key user groups and create a sample user scenario for fictional members of each group. Use the following table to get started.

3. After you decide on the target audience and goals for the site, it’s time to evaluate your content. This is best accomplished through conversations with the people you’re developing the site for. If this isn’t possible, be creative and come up with a list of content you think could be appropriate.

4. Use the answers to the following questions as a springboard for building the structure of your site. Then develop a tree diagram, similar to the one shown in Figure 1-1, to identify all the pieces of your site and where they fit within the overall structure.

• Does an official logo have to be used on the web site?

• Is all the content written and available in digital format?

• What are the main sections of the site? Does all the content fit within those sections?

• List all the content for the site. Assign each piece of content to a section (as necessary) and define the filenames.

Chapter 1 Self Test

1. What is a web browser?

2. What does HTML stand for?

3. Identify the various parts of the following URL: http://www.mcgrawhill.com/books/webdesign/favorites.html __________://________________/__________/___________/__________

4. What is WYSIWYG?

5. Fill in the blank: The latest version of HTML currently under development is _____________.

6. What is the Adobe Dreamweaver program used for?

7. What is one of the three most popular web browsers?

8. Fill in the blank: When you type a URL into your web browser, you send a request to the ________________ that houses that information.

9. What does the acronym “URL” stand for?

10. What organization maintains the standards for HTML?

11. How can you give your site’s visitors visual clues as to where they are in your site’s structure?

12. Fill in the blank: A good practice is to include a standard _________________ on all pages for consistency and ease of use.

13. Fill in the blank: Selling products and recruiting potential employees are examples of web site _______________.

14. Fill in the blank: Before you can begin developing your web site, you must know a little about the site’s target _________________.

15. If your site represents a new company or one that doesn’t already have information about its client demographics, where might you look for information?

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.