6

Frames

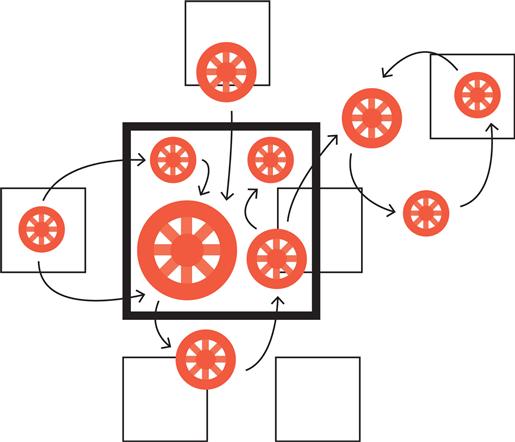

The two previous chapters explored Big Picture aspects pertaining to everything being said and done in the enterprise, and the Anatomy elements implementing those qualities in relationships to people, appearing on all levels as a fractal structure. Their ubiquity and dynamic interplay illustrate well the large degree of complexity design initiatives face on the enterprise level.

Any design challenge deals with the ambiguity of an underdetermined problem setting. Applied to an enterprise context, design has also to deal with a particularly complex environment, a wicked mess. The number of elements and interactions to consider, the diversity of stakeholders and their concerns, the many structures and systems a potential solution depends on, and the soft factors of culture, identity, and change, all make it difficult not only to develop a solution, but also to define the problem to be solved. That complexity makes it impossible to understand an enterprise in its entirety just by breaking it into smaller parts, even for a relatively small company—there are just too many variables which constantly change. Just about everything could be considered an influencing factor relevant to a design process.

We found that design practitioners sometimes struggle with such high-level, complex and ambiguous problems beyond the classic tangible realm of their fields. They tend to leave problem definition and formulation to other disciplines such as management or engineering, and prefer to come into a project at a stage when the client knows what he wants.

Using design strategically requires stepping out of that comfort zone, and applying the solution-oriented mindset of design practice to the larger context of the enterprise that the client seeks to transform. It involves exploring the problem space, questioning and enhancing given problem definitions and constraints, and influencing strategic decisions instead of taking them for granted. The intent of the Enterprise Design approach is to capture the enterprise as both design context and subject in a holistic fashion. To envision a future state beyond an isolated problem setting, designers need to be aware of the enterprise context it is embedded in. The 4 aspects described in this chapter help to develop conceptual models of the enterprise, to capture the details that are necessary and useful during the design process by looking at the enterprise from a particular viewpoint.

Designing means modeling

Because of its inherent complexity, exploring the enterprise as a field for design requires looking at it from different angles. In design theory, this activity is known as framing. The rationale of taking a certain perspective is to generate a frame, a particular viewpoint on a given context and environment, in order to make sense of it and develop a model of elements to consider—either implicitly as a mental model, or externalized in a visual representation or other artifact.

Creating models from different perspectives (also known as framed models) is part of any design activity. In the most general sense, models are representations of something—such as a given situation or context, an idea for a new or evolved state or system, or visible objects like a new building or website. They can be represented in drawings, diagrams, physical models, or written scenarios. Usually, models are either a simplified picture of reality or an illustration of a potential future. They are used to make thoughts and ideas explicit and create maps of related elements, as communication vehicles, and to gain insights into the expectations and needs of stakeholders.

Externalized in documents or other artifacts, framed models help us exchanging with people relevant to the design project, and to develop an understanding of their particular views. Those perspectives enable them to judge what is important, and what change to consider as a success. Driven by facts observed, personal experience, and our own thinking, frames in design combine objective and subjective reasoning. As abstractions, they concentrate on certain elements while deliberately leaving out or radically simplifying others, providing ways to look at a system from different perspectives and through different lenses.

Beyond just exploring the existing, models are used in the process of design synthesis and ideation to connect different aspects of a problem, and to explore and elaborate possible future states to resolve it with regards to these aspects. They permit us to make change visible as descriptions or prototypes that concentrate on one particular viewpoint while keeping other things abstract, and to try out and share different directions and options. They help us make difficult decisions in a space of concerns, become aware of tradeoffs between those decisions, and uncover opportunities for innovation. Furthermore, they are used to define the result of a design process, and to make detailed plans for implementation or production.

Design viewpoints on the enterprise

To understand the enterprise in a way that allows picturing the impact of a purposeful transformation, designers need to deeply explore it and envision its possible future states. Because of its inherent complexity, this means working with a particularly ill-defined problem setting. Any approach to gain insight and develop understanding therefore involves creating several simplified models of the enterprise as a system, with the concerns to be addressed guiding the choice of frames.

The aspects covered on the following pages help us to think about a given problem setting, in determining things to consider in design research and subsequent phases of the process. They enable us to envision potential outcomes with regards to stakeholder concerns, and the target state of the enterprise as a system. They are universally applicable to any kind of strategic design project, and provide a solid basis for custom, project-specific models.

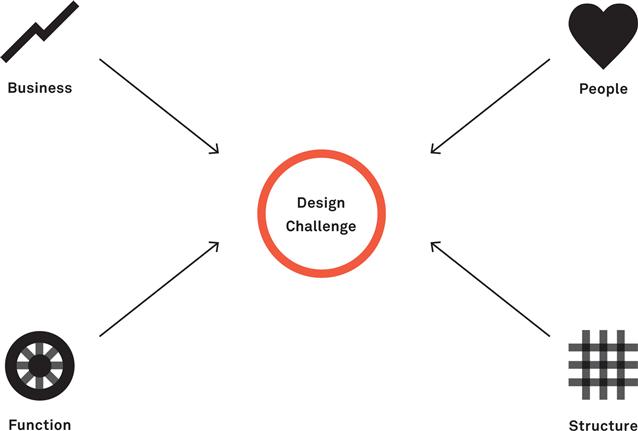

The four framing aspects used in the Enterprise Design framework suggest a set of fundamental perspectives which have their origins in design and systems thinking. they guide conceptual modeling and help when deciding on a direction according to strategic choices:

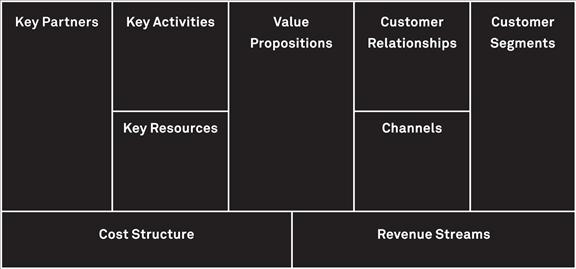

BUSINESS FRAME

captures how market actors create value, operate, and interact, and allows expressing in business terms the objectives the client or business owner intends to accomplish with a design initiative, the customer value gained, and the change desired.![]()

PEOPLE FRAME

captures who in the enterprise is being addressed with a design initiative, and permits grounding all design decisions in the individual goals, characteristics, needs, expectations, and context of individuals and groups in a human-centric way.![]()

FUNCTION FRAME

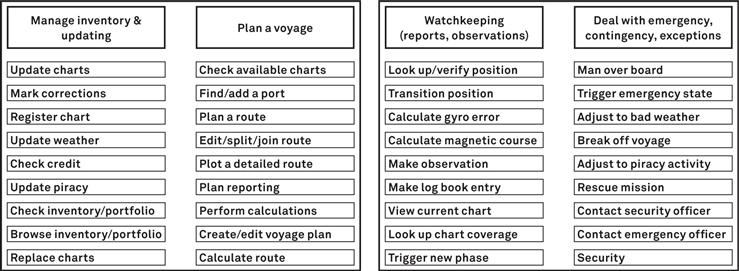

captures the purpose the enterprise fulfills and the behaviors it exhibits towards its stakeholders. The functional viewpoint helps the understanding, prioritization, and selection of a set of requirements the outcomes of a design initiative is expected to meet.![]()

STRUCTURE FRAME

captures the objects and entities relevant to the enterprise, how they interrelate and form a structure. It enables an exploration of the problem domain in conceptual models and the transformation of those models in the course of a design process.![]()

#8 Business

Really, what we’re doing as designers is, ultimately, and inevitably, designing the business of the companies that we’re working for. Whether you like it or not, the more innovative you try to be, the more you are going to affect the business and the business model.

tim Brown at the Rotman Business Design Conference2005

Part 1 of Intersection looked at the way the design competency can help to create value and sustain relationships with the people in touch with the enterprise, and to support an organization in developing and growing its business. Any design initiative is a form of investment in a transformation, to do business in a different and better way than before. Therefore, such an initiative always has a business objective, regardless whether that objective is stated explicitly, or exists only as an implicit understanding in the heads of stakeholders.

Looking at the enterprise from a business perspective as a playing field for design enables the design team to figure out and to further the rationale behind a client request, and to understand the context and objectives of the project. It helps to clarify why you are doing that project at all, and determines the conditions that make it a success or a failure.

Traditional design practice tends to consider these dimensions of the work only in a superficial way. Design goals are seldom expressed in terms that can be easily traced back to the business objectives of a client, making clear in business terms what a project should achieve. To make an impact in the enterprise context however, designers must challenge the status quo and extend their constant inquiry for the best possible outcome to the business results it generates. It becomes vital to develop a profound understanding of the business context, to reach out to all stakeholders and appreciate their views and concerns, and to design in a way that proactively contributes to strategy and objectives.

Both areas of focus have the goal of creating competitive advantage, by producing a compelling offer, outperforming the competition in dimensions relevant to customers, and reducing effort and cost. Taking this perspective allows us to apply business thinking to the design process of improving and reinventing, and addressing business concerns beyond a narrowly defined design brief.

Understanding the Business Context

In our experience, the most common reason for failure in a design project is not related to the quality of the ideas or the execution, or the talent of the design team. Many projects fail because the business objectives and the strategy driving them were unclear or misaligned with the design process. The Enterprise Design framework makes the business frame a core part of design research and modeling activities.

A thorough understanding of the business context behind everything a client or owner wants or considers necessary is an invaluable resource for designers. It allows us to align proposals according to the priorities and perceptions of stakeholders, tracing back requirements and wishes to business concerns, and coming up with solutions which pertain to this environment. More than just integrating into a given context, it allows for modeling and communicating a potential future in business terms, and envisioning the transformation triggered by the outcome of a design initiative. Modeling a business context is a process of inquiry, of capturing the existing, deriving constraints and chasing opportunities for improvement. It is an expression of the business contribution of a design.

Example

As an example for the business dimension in design, think of a company asking a design studio to create a website for them. in their briefing, the company might state requirements such as having a modern web presence or being available to customers around the clock. Applying the business frame allows translating these intermediary goals to strategic objectives that reach beyond an isolated website: supporting customer relationships with an improved reputation and service, leading to more revenue and better retention.

As soon as these business goals are known and agreed on, the design team can consider options holistically across the entire customer Experience without restricting the project to just one channel. An outcome designed to contribute to the business objective might address service operations and after sales, brand considerations, or other elements outside the initial scope of designing a website.

A Business View on the Enterprise

As explored in Chapter 3, design is used mostly within the context of the products and services provided to the customers of an organization, or the communications around those offerings. As a strategic competency for responding to complex problems, it can be used for a much broader range of areas beyond product development. With all the actors and things going on in the enterprise, there are numerous opportunities to drive change by design, following the strategic direction of a Big Picture view on the enterprise.

Exploring the enterprise from a business viewpoint provides tactical direction where design initiatives as investments in transformations can have the most significant influence to help a business strategy come to life. It changes appearances and behaviors, initiates different ways of doing business, and uncovers new opportunities to generate value for people. This also involves introducing new elements, removing others, and rearranging their interplay in business activities.

The business frame focuses on how a business works and how it engages with the markets it addresses, driven by two considerations:

DIFFERENTIATION

the way a business creates value for its customers, and fosters and sustains relationships to them, and makes a unique and distinguishable proposition to the market.

EFFICIENCY

the way a business maximizes profitability, manages resources and infrastructure, and achieves its objectives with the least possible amount of monetary engagement and human effort, and achieving a sustainable development of the enterprise as a whole.

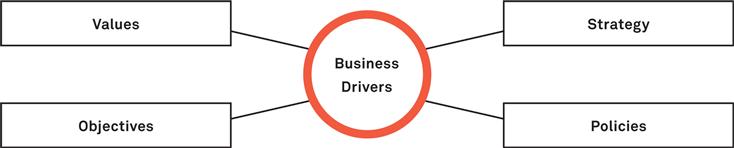

in exploring the drivers behind design initiatives, we found the following elements to be particularly relevant to the business context:

VALUES

pertaining to the fundamental idea of what the business is about, what it stands for, and how stakeholders see it now and in the future. The goal of design synthesis is to capture and express this idea, to help developing a vision of the future by making it visible.

STRATEGY

related to the way a company seeks to achieve competitive advantage over other market players by differentiation of its offering and maximizing efficiency. An awareness of how it contributes to these efforts makes a design initiative strategically relevant.

OBJECTIVES

or goals related to the business success as well as metrics suitable to measure whether those goals have been reached. They form the business case of a design project, describing the goals and, if possible, quantifying the return on investment.

POLICIES

are constraints and rules either self-created by the business following strategy and values, or imposed on it by regulation or law. They state the way things have to be done by the business, so that they affect design decisions and should be clearly defined.

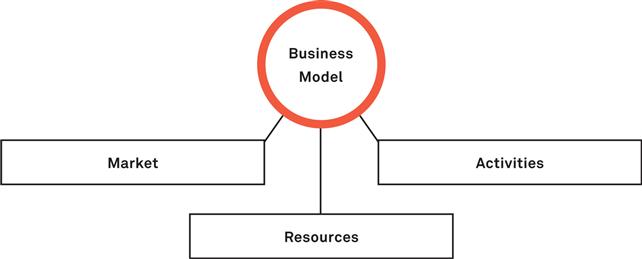

when modeling from a business perspective, the following elements are often of interest to research activities and solution definition:

MARKET

the larger environment to be addressed, with competitors and substitutes, customers to be served and offerings for them, prices and cost structures for customers, as well as market trends and issues. Design outcomes should achieve a better positioning for the organization on a market it is engaged on, or enable it to address a new market.

ACTIVITIES

activities carriend out thoughout the business, that span organizational units, people and tools for automated processing, exchanges via channels used to interact with customers or other organizations, transactions, and flow of revenue. design outcomes should enable faster, simpler, and more robust and reliable processes.

RESOURCES

assets important to the business and the cost they produce, technical or physical infrastructure elements used as platforms to automate and manage work, external partners involved in business activities, communication channels, and tools. design outcomes should achieve more with fewer resources and less cost.

As a starting point for the business frame applied, look at the enterprise as a whole in therms of its big picture aspects. this allows identifying opportunities for innovation and improvement, and developing the key qualities that help an organization pursue its strategic direction in daily business:

IDENTITY

the identity conveyed by the organization, brands, and informal and personal identities, and the way these identities are reflected in image and reputation are essentially how the enterprise creates trust toward its stakeholders. brands are organizational resources and assets, and should be designed to help do business and develop it.![]()

ARCHITECTURE

the combination of formal structures put in place and managed to execute and opera- tionalize the business strategy. The business focus looks at the role of these structures for its activities, how they are maintained and developed, and how to improve business performance by achieving better results with less effort.![]()

EXPERIENCE

the way the business appears in the lives of its customers and other stakeholders as a service provider, employer, or in other roles, and the noticeable value it creates and provides to them. Exploring the experiences of people in touch with the enterprise allows identifying business opportunities to provide more valuable benefits.![]()

Business Design

A very recent addition to the area of design disciplines is business design, a term used more and more as a job role by companies in the field of strategic design such as the design and innovation consultancy IDEO, as well as in management graduate programs. The essence of this approach is designing and redesigning businesses expressed in models, applicable to both new companies and established organizations. It is about applying design to problems related to generating strategic options, defining a good core idea of a business, and modeling how the business generates demand and provides value, and finally about operationalizing this model.

An approach to innovate with business models is outlined in osterwalder’s and pigneur’s book Business Model Generation, applying design to inform strategy, define and reshape business models, and plan their operationalization. It portrays the Business Model Canvas as a tool to generate a map of a business, and to blend ideation, prototyping and storytelling with analytic and strategic tools such as the framework described in the book Blue Ocean Strategy by w. chan Kim and Renée Mauborgne. practitioners of business design combine a design-led approach to achieve business innovation with proficiency in core business domains, including Marketing, operations, and Finance. key to this combination is applying a spirit of entrepreneurship that bridges an emotionally strong business idea with a viable business model.

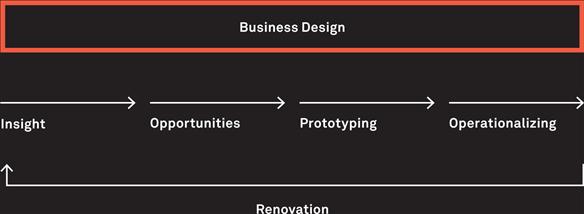

Business Design encompasses different steps of analyzing, designing, prototyping, and introducing new and evolved business models, with a focus on achieving viability:

DEVELOPING INSIGHT

scanning the environment using quantitative analysis and visualization, to understand the drivers behind a business model as well as external and internal success factors.

DISCOVERING OPPORTUNITIES

identifying and applying recurring patterns in business success, in order to discover opportunities for growth, and explore options for a new competitive positioning.

PROTOTYPING AND SIMULATING

making models visible as evaluation and communication devices such as stories, sketches, financial scenarios, or small scale prototypes to be tested with customers.

OPERATIONALIZING AND ITERATING

defining and refining management systems, organizational structures, capabilities, and resources behind a business model, to determine the critical factors that make it work.

Anatomy elements that form relationships in the enterprise are the necessary ingredients to do business:

ACTORS

stakeholders and the business roles they play in the market and the enterprise, most importantly customers, but also investors or (potential) employees. Depending on the level of design, they can be further segmented into different customer segments, investor types, or organizational divisions.![]()

TOUCHPOINTS

channels used to reach actors, offer, deliver, or acquire products and services, and exchange money, information, and goods. They provide the interface to do business with people, both as consumers or representatives of customer organizations, and can be of physical or virtual nature, direct or indirect.![]()

SERVICES

business activities that generate a value that can be expressed in monetary terms, and create or sustain relationships to customers or other actors. This includes the offerings produced and made available for sale and consumption, as well as the ongoing processes creating or supporting stakeholder benefits.![]()

CONTENT

messages and communications with regard to business decision making, within the organization as well as with other actors in the larger enterprise. This includes customer communication along the commercial process, as well as information used for management decisions for management and operations.![]()

Designing Business

Approaching a design challenge from a business perspective requires designers to think like an entrepreneur, or—in the case of an established business—like an internal or external investor in a business transformation. Key to this is the concept of business modeling, the practice of understanding and redesigning the way an enterprise creates value and generates revenue. Based on the business view of the enterprise and individual business context described before, it involves modeling the business and its potential evolution.

Although applicable for any design challenge, the business frame is often considered only superficially in today’s design practice. In order to make an impact on a strategic and enterprise-wide level, it is crucial to develop a deep understanding of the way business is done, both currently and in a changed future setting. A strategic dialogue with business leaders that have commissioned the design work is only possible with a design practice that aims to inform strategy. Designers have to do so in business terms, making explicit their plans to transform enterprise qualities, and how design outcomes can contribute to business success.

A prerequisite for such a dialogue is to have the design team work closely with business stakeholders when preparing and running design initiatives, especially those working on a plan or vision for the future of the enterprise—entrepreneurs and executives, strategists and Marketing experts, owners of projects and programs, investors, customers, and suppliers—essentially anyone tasked with innovation and change, both inside and outside the organization.

Applying the business frame thoroughly is essential for design teams to position themselves, as innovation drivers in the enterprise instead of as merely executors of what others have defined. But this also results in new challenges. It requires discovering business opportunities in design research, and generating choices as investment options. These options have to address how the outcomes of the design process will contribute to business success by generating customer value or improving operations, requiring both analysis of the current business and operating model and a quantification of success conditions. Likewise, they have to be grounded in a well-defined business strategy, translating values, strategy, objectives, and policies into design principles to be applied.

#9 People

Think of two customers. Both were born in 1948, male, raised in Great Britain, married, successful and wealthy. Furthermore, both of them have at least two children, like dogs and love the Alps.

One of them could be Prince Charles and the other Ozzy Osbourne.

Marc Stickdorn and Jakob Schneider in This is Service Design Thinking

Applying a human-centric perspective today is probably the best known way to approach a complex design challenge. This follows from the idea that in the end, it is always people you are designing for, people probably very different from yourself and your team. The goal of any design initiative is to achieve an engaging experience, by providing outcomes which are considered valuable by their audience.

Just as the other aspects described in this chapter, there is no definitive collection of tools or methods, but a range of different approaches that can be used to better address people with a design initiative. A core principle is the goal to understand and relate to people, beyond traditional market research approaches as collecting demographic data about them, or asking them for their opinions. Genuinely designing for human reality requires the designer to find out about people and their lives—attitudes, concerns, aspirations, daily routines, and contexts—in order to to generate the insight knowledge and empathy that drive design decisions. Applying the people frame therefore means approaching both the design problems faced and the potential results envisioned in a humanistic fashion. The insights gained about people allow us to find opportunities to make things better for them and to define and predict the role the outcomes of a design initiative might play in their lives.

Developing knowledge and Empathy

In our daily lives, we encounter people we know well and others we do not, people we do or do not understand when we talk to them. We consider some people friends and are indifferent to others. This aspect of social reality is closely related to design work and the role of the people frame. People are special—addressing them requires designers to appreciate and embrace what makes us individual, to come up with concepts and ideas that fit.

The people frame is based on a straightforward assumption: if we take the people that a design is made for into account and relate to them on a human level, it is much more likely that we will meet their needs and expectations, with the objective of making them happier than before. This in turn is an implicit goal of any design project, since making these people happy means engaged employees, satisfied customers and investors, other stakeholders to the business. While this principle sounds quite simple, holding to it in real life turns out to be somewhat complex. It means making people and their lives an integral part of our creative thinking process, people who in many cases we do not know much about.

The focus of the people frame is to make the outcomes of the design meaningful to people, driven by two key aims to be achieved:

USEFULNESS

making the outcomes of the design process useful in that they help people achieve their goals, addressing the very personal reasons they have to engage in activities or tasks. This involves making things usable, findable, accessible and, useful for the audience.

ENGAGEMENT

making the design outcomes compelling and desirable by addressing people on an emotional and subconscious level. Going beyond pure usefulness, engagement involves elements of stimulation, persuasion, and personality, to generate attraction and build trust.

Example

Imagine the perfect watch you want to give a close friend for her birthday. The basic purpose of looking up the time is quite obvious, so that just about any product that shows hours and minutes fulfills it. To find the perfect watch, however, you will have to take into account a whole range of individual factors and considerations, which depend on your personal relationship and insight into her life. While people with a lot of business travel might like switching between time zones or sophisticated alarms, others might prefer a simple and elegant display. Beyond the functional, a watch might be considered a fashion item, so that brand and appeal come into play. Finding or designing the perfect watch for your friend therefore requires a deep knowledge of her individual lifestyle, daily routines, characteristics, and personality.

Methods traditionally used in Marketing or Product Development, working with standardized models of people based on demographics and quantitative research, are not suited to generate the insights needed to acknowledge and consider people as human beings. Instead, we apply methods used by anthropologists and social sciences, spending time with people to get a personal understanding of their lives, both broad and deep. It requires effort for qualitative research, collaboration, and validation of outcomes, along with a mastery of appropriate techniques of ethnography and shared creative work. In real-life projects, we usually do not have the luxury of designing for close friends or for ourselves. Finding out about the people addressed and involving them in the process therefore is vital to develop the knowledge necessary to determine a good direction for further design work and to identify potential solutions that work and fit.

The Enterprise as a Social Space

The people frame perceives the enterprise as a social construct, as a group of persons. It enables a design team to think of the people targeted, involved, and affected by their outcomes. It allows them to immerse themselves in people’s daily life, and to develop the knowledge and empathy that are behind good solutions and great ideas. As a strictly human-centered viewpoint, it reduces the challenging problem settings of a complex enterprise environment to the everyday reality of people and the personal and social factors that influence it.

in order to develop knowledge about the people you address with a design initiative and gain deep insight into their lives, take into account the following dimensions in research and modeling:

CHARACTERISTICS

demographic data such as their age and profession, but also aptitudes and skills, habits, and attitudes.

ACTIVITIES

looking at the nature of tasks, frequency and duration, tools or artifacts used, and interactions with others.

GOALS

what people want to achieve, immediate and long-term goals, reflecting rational or practical issues related to feeling happy.

SOCIAL ENVIRONMENT

groups, roles and identities, cultural norms and beliefs, local particularities, and the nature of relationships.

CONTEXT

both physical environments and states of mind in which people carry out activities and interact with each other.

Beauty and brains, pleasure and usability - they should go hand in hand.

Don Norman

Elements of relationship Anatomy are about the very concrete manifestation of the enterprise in a person’s daily life:

ACTORS

the roles of a person in social terms. This relates to the individual reflection of the relationships to others in the enterprise space, responsibilities, and the expectations, leading to a certain self-image and behavior. Engaging actors as people means designing for individual aspirations and motivation with regard to their role.![]()

TOUCHPOINTS

the situations someone experiences across the journey of interactions with and within the enterprise, and the particular physical and psychological contexts in which they appear. This refers to the environment, time, duration, and intensity of those contacts, and the factors to be considered to address that context.![]()

SERVICES

the activities carried out in the enterprise to support people and generate benefits for them. Services appear to people only in the effects they produce, and the communication processes and exchanges happening around them. Looking at services from a people perspective allows exploring their role and how they are perceived.![]()

CONTENT

information and messages being exchanged between people in the enterprise, relevant to people only as knowledge that is useful by informing choices and supporting decision- making, or otherwise considered of interest or entertaining. Content is the essence of any exchange, to be designed to fit and make sense to people.![]()

when looking at the Big Picture of the enterprise from a people perspective, it presents itself as a dynamic social space of people interacting with each other in a multitude of different ways:

IDENTITY

identities that appear in the enterprise space and the way they are perceived by people, and lead to certain images in their minds. To people, brands and informal identities are meaningful symbols expressing organizational identity and culture, connected to the enterprise as a social and cultural system, having manners and beliefs, language and rituals, and following behavioral norms.![]()

ARCHITECTURE

the way the enterprise works for people and the role they play in the way it is structured and executes activities. From a people perspective, architecture refers to organization and formally defined responsibilities, individual tasks that contribute to the running enterprise (not restricted to staff, think of customer tasks), tools and systems used, and the human factor in business operations.![]()

EXPERIENCE

while the experience quality of the enterprise is inherently people-centric, looking at experience with an individual’s eyes is all about their overall personal context and condition. it allows examining the meaning of the enterprise of people in touch with it and important to its success, and the role it plays in their lives.![]()

Human-Centered Design

The term Human-centered Design (HOD)—originally coined by Don Norman, and often also called user-centered Design—has been around for quite some time now, used in the context of various design disciplines. It usually refers to a general attitude and mindset applied to the design process as a whole, bringing people and their needs and characteristics into focus of all efforts. While there is no consensus in the design industry what such a process must include, there are some approaches and methods which are developed and evangelized by HcD practitioners. The basic assumption is that human reality, in all its diversity and complexity, is somewhat hard to understand, capture, and describe. It is quite a challenge to consider it in the level of detail needed to capture everything relevant to a design process, and to be able to envision the change it will produce for people.

These tools help a design team to develop a deep understanding of the people they consider relevant to the project, because they are being addressed or impacted, or involved in bringing it to life. In enterprise-wide projects with a large and diverse set of stakeholders, they help to keep human reality in focus during the entire process.

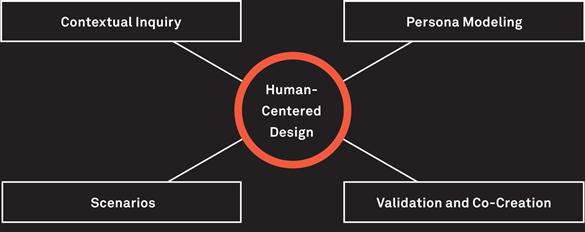

HCD practitioners use a set of methods, most of them having roots in ethnography, sociology, and other people-centric domains:

CONTEXTUAL INQUIRY

invented by Karen Holtzblatt and Hugh Beyer, is based on research sessions in the context where relevant activities take place. it is a mix of interview and observation, letting the interviewer act like an apprentice learning from someone how to do things. it results in a lot of data that is captured in various models informing the design process.

PERSONA MODELING

introduced by Alan cooper, is a technique working with fictional characters based on research with people. According to him, they should be used in a goal-directed design process, exploring the personal goals a persona wants to accomplish and designing to fulfill them as well as possible.

SCENARIOS

are a common tool in most design disciplines, and come in many different forms: as narratives or stories, as storyboards or sequenced sketches, or in the form of diagrams to represent a sequence—all these models are capturing a personal experience of one or several people, providing a basis to envision a possible future state.

VALIDATION AND CO-CREATION

are approaches to involve people actively in the design process. Validation techniques allow putting potential outcomes to the test with people, by facilitating test sessions (also known as Usability Tests) or informal reviews. co-creation goes beyond that by involving people in the creative process, working collaboratively with the designers.

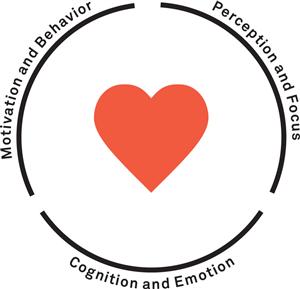

Designing with the people frame is applicable for research, design, and validation activities. it is taking into account multiple distinct but intertwined psychological qualities, and addresses them by applying both factual knowledge about them and subjective conceptualization in an individual context:

PERCEPTION AND FOCUS

are about the impressions of the human senses, what a person sees, hears, smells, tastes, or touches. People fi lter what they perceive to direct their attention on messages and things they focus on, guided by emotion and cognition. Design works with these elements to direct the focus and facilitate comprehension.

COGNITION AND EMOTION

refer to thinking processes and feelings, and their complex interrelationships. This includes expectations people have with regards to an activity, associations they apply to develop conceptual models of the world, and questions of memory and learning. Design considers both aspects of the mind, conscious and reflective thinking as well as affection and emotional reactions.

MOTIVATION AND BEHAVIOR

are about what makes people take an action, to what kinds of activities and conduct that leads them, and how they adapt to the world around them. Understanding motives and intentions in the context of a design problem provides the basis to discover and address the hidden and unexpressed needs of people, by predicting situational change and motivating new behaviors.

Designing for People

Applying the people frame requires investment in research and collaborative work with the audience being addressed, and with the stakeholders considered important. Beyond just knowing the raw facts, working with actual people enables us to walk in their shoes, experiencing the struggles of activities first hand, and to empathize with the people we are designing for. In our design projects, that deep understanding gathered about people has proven to be an important source of ideas, and enables the team to re-frame a given problem in a way that it guides all design decisions. This however requires translating the findings into actionable insights.

The implications of following an HCD principle seem to be interpreted very differently among the various fields where the fundamental paradigm is applied. While practitioners of usability or ergonomics work with analytic approaches driven by metrics, such as task efficiency or cognitive load, methodologies used by design professionals strive to empathize with people, or to engage in co-creative design exercises. Still, all of these different interpretations share a common goal: making people a central consideration in every design decision, and actively involving them in the design work.

In the enterprise context, the people frame connects the design process to the human reality that it seeks to influence—applicable not just to the target group the designers are focusing on, but to the whole range of actors identified as relevant. This helps to expand the human-centric focus beyond an individual outcome. Instead of considering people just as users of a website, customers addressed by a service, or other predefined roles, it allows looking at people first and foremost as human beings with needs and aspirations.

Designing for the enterprise as a social space means considering personalities, individual meanings or roles, and offerings to key stakeholders as persons. This view goes beyond usability and satisfaction, concepts which basically strive to make things less bad—delivering what is expected to not disappoint people, and avoiding needless hassles and efforts. The people frame aims for the big goals: engaging people, helping them to have fun, or making their work a smooth flow. It allows adapting the result of enterprise activities to their lives, their problems, and what makes them happy.

#10 Function

Design is not how it looks like and feels like. Design is how it works.

Steve Jobs

Taking a functional perspective is common in many domains where design is practiced. Because of the difficulties of planning, designing, and implementing any kind of system beyond a certain degree of complexity, it is a natural way to look at things, especially in engineering disciplines, and has also finds its way into Marketing and Product Management. In essence, it is about what a product or another outcome of a design process is actually being made for. It allows specifying, communicating and documenting the scope of a project, resulting in the functions or features it should support.

The idea of a function is representing one of the most relevant and universal values in design work. American functionalist architect Louis Sullivan expressed this in his famous quote that form follows function. Unlike art that must not serve a clear purpose or goal, the outcomes of design work by definition always have a function. Despite the creative nature of the work itself, drawing on individual experience and inspiration from outside the given problem space, any result of a design process follows the underlying rationale, designed to be consumed, perceived or used by someone. It strives to generate value for both the people commissioning it and people being addressed.

The function frame in design attempts to clarify the intentions behind a project. It helps to define what you want to create, but also—often more importantly—what you do not. It is a driving factor important to any design initiative even if not consciously addressed. Applying it consciously in the design process allows us to clarify the purpose of a project as an explicit and shared idea, and to design the behaviors to fulfill that purpose. A key challenge is to determine and capture function in definite requirements.

Eliciting and Modeling Functional Requirements

In the most general sense, function refers to everything related to the rationale behind a design project. It is about the meaning the outcomes will have for persons and groups, the client or owner commissioning the work, and other potential stakeholders, and about planning the resulting system’s behavior in advance in a way that anticipates that meaning. In the end, it is not determined by the designer or developer—it is the user who attributes function. Therefore, predicting function and specifying features usually requires taking into account a large amount of different facts, stakeholder opinions, and observations made in the environment of the project and using this knowledge to elaborate a set of requirements.

In our consulting practice, we found this part of the design process to be particular difficult to get right. While it is necessary to get together with the customer and the people addressed to ask for their needs, in isolation such an approach often leads to failure. It risks producing a large wish list of features and trendy topics, and neglects the potential of hidden needs, ideas available in the project team or among stakeholders, and insights gathered from applying the other perspectives described in this chapter. While having a clear picture of what is wanted is of high value for design decisions, a feature-driven approach bears a great danger, known as feature creep: adding more and more to the list under the assumption that more is always better, or under pressure from the client.

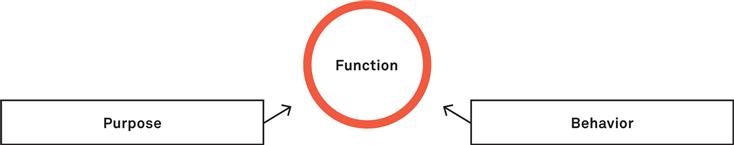

The function frame looks at how something works or should work to serve a defined need, taking into account two main considerations:

PURPOSE

what the project is about, making outcomes of the design process respond to actual requirements and expectations, including goals to be supported and qualities or constraints to be addressed.

BEHAVIOR

how its outcomes should work as a system to accomplish a goal, supporting activities, tasks or business processes, defined as a behavioral description of interactions with the environment.

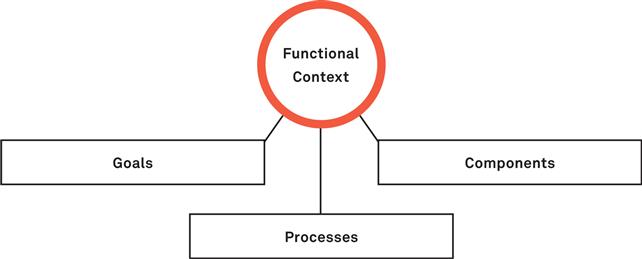

The elicitation and analysis of requirements means understanding and modeling the functional context in which the resulting system will be working, considering a set of distinct elements:

GOALS

either explicitly expressed by stakeholders or otherwise becoming apparent, that can be translated into a function the resulting system has to fulfill. Models about goals are informed by conversations with stakeholders or research, but also by ideas that might unveil a hidden need.

PROCESSES

representing any form of organized and predictable activity corresponding to the fulfillment of a certain set of goals. A functional process model is a detailed description of what is going on, in order to determine the functions required to support and improve those processes. it might also detail the flows that appear in the system as movement of information, money, value, time, or physical resources, and how inputs are transformed and turned into process outputs.

COMPONENTS

are conceptual objects that group a set of related functions as part of the overall system, acting in a process to support the achievement of goals. components are a mental construct to allow decomposing sets of functionality into systems and subsystems, as well as external and internal parts, helping to determine the working structure and behavior of a system.

Requirements are often just laundry lists: someone makes them up, they are arbitrary, out of context and just plain wrong.

Sally Bean, Enterprise Architecture Consultant

Even if the functionality selected is based on a clear understanding of the stakeholders and the concerns the enterprise needs to address, there is a chance that we will end up with a big list of unnecessary, arbitrary, or conflicting requirements that make the results needlessly complicated and ill-suited to solve the key problems. It is essential to distinguish between the functional context of the goals and processes to be supported, and the components designed to perform a function, again looking at both the current state and a potential future.

A thorough modeling of the functional context lets us capture what is expected of the system resulting from a design process in terms of the purposes it has to fulfill, instead of resorting to subjective and arbitrary lists of features. This in turn is a suitable basis from which to deliberately address function in a design process: once the required functions are known to the design team, it can proceed by elaborating a system of components to perform them. Such a systematic approach to function might lead you to completely different functional requirements than originally envisioned, but helps to identify and solve the actual problems behind vague wishes expressed by stakeholders.

Example

Because any enterprise serves a multitude of stakeholders, a way to look at it from a function perspective is imagining it as a machine that carries out an important task for someone else. In the case of an airline, it is seen by passengers as a transportation machine, while investors see it as a money-making machine. To crew members it appears as a job-making machine, to the supplying airplane manufacturers it looks like a product-buying and consumption machine. Looking at the enterprise holistically involves considering these various functions, and envisioning functional components (or subsystems) that perform them. Components that play a role in this design could be a reservation function, financial performance management, or an HR service for employees, embodied and visible to people as tools or procedures related to those functions.

The function frame views the enterprise as a working system that exists to serve a specific purpose, by performing a certain set of functions:

IDENTITY

![]() the purpose and functions associated to identities and brands of the enterprise, and the behavior the system exhibits in executing these functions. In Marketing practice, this is also known as the brand promise, and allows designing functional components to deliver on that promise by providing value and endorsing adequate behavior.

the purpose and functions associated to identities and brands of the enterprise, and the behavior the system exhibits in executing these functions. In Marketing practice, this is also known as the brand promise, and allows designing functional components to deliver on that promise by providing value and endorsing adequate behavior.

ARCHITECTURE

![]() the way the enterprise operates by making functional components work together. A functional perspective on architecture ties all formally defined structures and activities to the functional context they are used in—the processes and corresponding goals they serve—and enables designing the enterprise to fit into this context.

the way the enterprise operates by making functional components work together. A functional perspective on architecture ties all formally defined structures and activities to the functional context they are used in—the processes and corresponding goals they serve—and enables designing the enterprise to fit into this context.

EXPERIENCE

![]() how the functions of the enterprise are accessible and usable to people, supporting them to meet their personal goals. This refers to the purpose the enterprise has for a person, and the behavior it exhibits. It allows conceiving abstract enterprise functions in a way that makes them useful and valuable for people’s activities.

how the functions of the enterprise are accessible and usable to people, supporting them to meet their personal goals. This refers to the purpose the enterprise has for a person, and the behavior it exhibits. It allows conceiving abstract enterprise functions in a way that makes them useful and valuable for people’s activities.

Elements on an Anatomy level can be seen as the context and drivers for functional behaviors:

ACTORS

users addressed with a particular function, feature, or behavior. Finding out about the role in the enterprise and individual goals is the basis to elicit requirements and conceive functionality that makes sense and becomes valuable for a certain actor.![]()

TOUCHPOINTS

interfaces between users and functions, enabling interactions and providing the input / output channels (or front-end) required for any function. Applying this frame on touch- points enables designing them as interfaces to support certain functions.![]()

SERVICES

sets of functions that in combination provide a benefit to service users in the enterprise. services in functional terms are pre-planned behaviors being used in people’s activities. They allow conceiving tools, products, or resources serving functional needs.![]()

CONTENT

the input needed for functions to work and the output they produce (also known as functional parameters and results). Content from a functional perspective refers to data needed for a defined function to work, and the data produced after its execution.![]()

Functions of the Enterprise

Any enterprise is created around a sense of purpose shared by its members, which makes it play a certain role in their lives. Applying the function frame allows us to undersand that role in detail by analyzing processes and corresponding stakeholder goals, and lets us capture and document the functions it must perform to fulfill its purpose. This general purpose the enterprise fulfills for its community of actors drives the decision of which functions to address with a design initiative. It is based on the idea that any function made available as a product or service contributes to that purpose.

Therefore, developing functional models of the enterprise forms the basis to elicit, select and justify the requirements and qualities to be met, and to agree on the functional components and features to be included in the scope of potential outcomes. By applying the functional frame beyond the scope of an individual project, the potential results can be considered part of the larger functional context of the enterprise in order to identify redundancies and integration needs, and to seek opportunities for functional gaps to be filled.

Designing with Function

In everyday practice, the function frame plays an important role in almost any design project, since it relates to the purpose and goals driving it. In Enterprise Design, it helps to envision the enterprise as a functional system, and to design in terms of the functions it fulfills for its stakeholder community. When looking at function on an enterprise-wide level, designers often face a mass of conflicting, overlapping, and intertwined needs. To address these usually requires a certain degree of complexity in the solution. In order to choose and prioritize the functions to address, they have to systematically manage requirements.

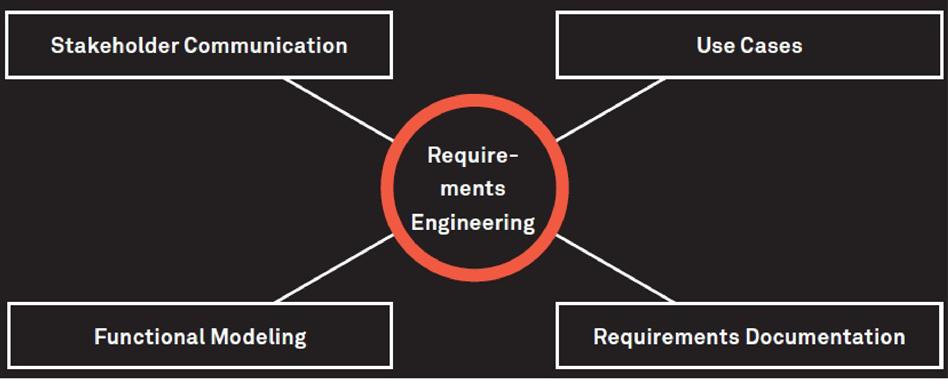

Requirements Engineering

The professional practice of selecting and managing requirements comes from engineering- driven approaches to projects. It is particularly in evidence wherever technical systems exhibit complex behaviors, and on projects where the question of feasibility is prominent. Even when not explicitly addressed by the team, it appears in the form of feature lists or briefing documents, requirements specifications, or other informal means of describing what the outcomes are supposed to do.

Requirements Engineering is an approach to systematically manage functional and other types of requirements. It has its origins in technology-driven disciplines such as professional software development or systems engineering. The activities performed in practice encompass the structured elicitation, analysis, and recording of the needs and conditions that the outcome of a project must meet in order to be successful. That outcome can be a machine, a piece of software, or any other type of system to be planned and constructed.

The practice of Requirements Engineering usually puts a particular focus on the functional aspect of what a system’s behavior should accomplish, but also looks at non-functional or quality requirements such as maintainability or security. Although establishing requirements is part of any design initiative in some form, applying it deliberately and with some formality helps tremendously to agree on a project’s scope.

More than anything else, the process of establishing requirements is a collaborative endeavor of envisioning the outcomes of a project, prioritizing functions and qualities based on that vision, and determining how to implement them as a system. Instead of being carried out in isolation, it has to be an integral part of the design process, with the goal of achieving a common understanding of its outcomes, while the methods applied and level of detail required depend on the particular setting.

The practice of Requirements Engineering applies a variety of techniques to come to a set of requirements to be addressed:

STAKEHOLDER COMMUNICATION

activities to determine potential requirements by collaborating closely with the different parties involved in the project and those impacted or addressed by its outcomes, for example, by conducting stakeholder workshops to inform use cases.

USE CASES

written or graphical descriptions of the behavior a future system exhibits, captured in terms of outside interactions with it. This practice treats the system like a magic black box, avoiding any technical language and excluding details on how it works on the inside.

FUNCTIONAL MODELING

using simplified models to describe how the target system or current system works. This is subject to functional decomposition to divide the functional components until the model captures the behavior on a level of detail suitable for construction.

REQUIREMENTS DOCUMENTATION

capturing requirements in a way that is they are specific and measurable to enable implementation. some methodologies suggest very detailed documentation while others, such as in agile software development, favor writing short user stories.

Modeling function relevant to the design project and to the larger enterprise is a valid basis for establishing requirements, because in the end all requirements — including those describing qualities rather than behavior—pertain to function, to the purpose to be fulfilled by the project’s results, and to the anticipated usage and value generation. It allows us to ground the vision of what the outcomes should do in the goals and processes to be supported, and to design components to fit into that functional context. Such a shared definition of functional models and solid requirements in turn is the basis for working with engineers, system designers, and technologists, for mapping out the scope of the solution to be built, and for ensuring that it is actually feasible.

The choice of requirements is informed by many sources of inspiration — findings from applying the other perspectives, competition or similar projects, new technologies and their possibilities, as well as the free flow of ideas that emerge in a multidisciplinary project team. Applying the function frame enables the design team to agree on what the outcomes should be, to reduce the functional scope to support the most relevant goals and processes, and to provide relevant input to engineers planning the technical part of the project.

#11 Structure

The three frames explored earlier illustrate the difficulties of applying design practice to something as complex as an enterprise. In many cases, the designer is not familiar with the particular domain of a design challenge, which requires detailed knowledge of a certain industry, target group, local culture, or particular use context. It involves gathering and making sense of a large amount of data, in order to develop a thorough understanding about the real-world setting where the outcomes of a design process will be applied.

The structure frame supports this endeavor, by focusing on things that matter to the design project, and their interrelationships. It helps when developing conceptual models of the context and the subject matter of an individual design initiative, and of the structural context of the problem being solved — also called the domain. These conceptual models represent the mental models of different people involved in the design process, and of those addressed by or in touch with its outcome. As with the other perspectives, it is used to actively generate knowledge by modeling and exploring the current state as the context of a design challenge, as well as by envisioning the possible change enacted by introducing a new system of structured elements into that setting.

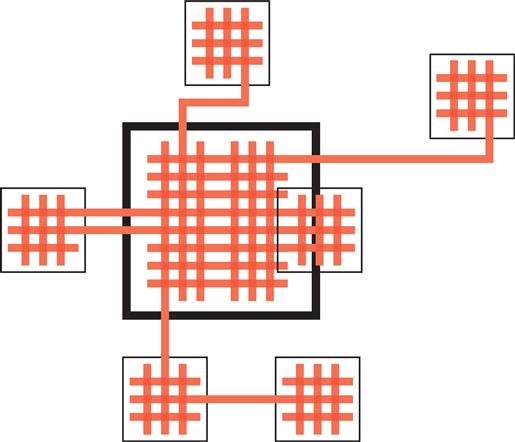

Structural models have their roots in Linguistics and Systems Thinking, and are embraced in engineering approaches such as object-oriented programming and business analysis. Known as object or domain models, and sometimes called ontologies, they describe a set of objects (also called referents or entities) and their relationships. In design projects, working with structural models helps us to learn about the things relevant to a certain design problem. Concrete techniques include concept maps, class diagrams, and entity-relationship models. In the Enterprise Design framework, the structure frame is used to map the things that are important to the enterprise in one way or another, to explore their roles and relationships, and to think about how the results of the design process might transform that structure.

Structures are seen differently by people involved in the project or impacted by its results, reflecting the view of different roles such as business owner, customer, staff, or planner. In the course of a design project, it becomes clearer what parts of the structure have to change to respond to people and business objectives.

The emphasis of this aspect is on developing a holistic understanding of the structural context a design process seeks to improve and envisioning the role its outcomes will play in the wider environment of interrelated objects.

Working with structural models is another way to frame a complex design challenge, focusing on an understanding of the problem domain, and exploring the objects to consider in a design. A conceptual model describing a structure can be expressed in different ways and using different techniques, but usually contains a description of entities and how they relate to each other. It always reflects subjective conceptual models of the people creating it, and can therefore be seen as creative and generative as a business or mental model. Change introduced by a design process is never neutral in such a conceptual model, but becomes a part of it, enhancing or modifying things and resulting in an evolved structure when applied in real life. By introducing new objects, making others obsolete and rearranging relationships, design always attempts to restructure the world.

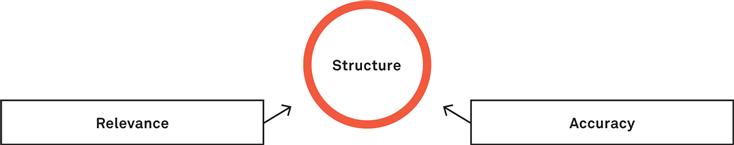

Based on insights from stakeholder research and expert knowledge, the list of things to consider in such a structural model quickly becomes quite large. The structure viewpoint focuses on two main concerns:

RELEVANCE

placing a “spotlight” on a subset of objects which are important to the enterprise with regard to the business objectives, the people being addressed, and the structural context.

ACCURACY

capturing the relevant parts of problem space, domain, or potential future state in a way that corresponds as much as possible to reality, as well as to common conceptual models.

Modeling the Structures to be Designed

One of the particular strengths of the structure viewpoint, despite its subjectivity, is its ability to align and integrate different conceptual models into a coherent representation. The interrelated objects expressed are shared between many different conceptual models of a system, and allow for comparison, prioritization, and alignment.

For the creation of structural models, virtually any noun that people use might qualify as an object to be included. These could be physical and virtual things, people or organizations, representations and symbols, activities or processes, as well as mental constructs or categories—the important question is not the type, but the relevance and accuracy of the model for the design process. It can also help to deepen the analysis by exploring different relationship types such as generalization, instantiation, cardinalities, or by including attributes of objects and the tasks associated with them. Working with structural models enables the designer to externalize and study the different models based on research, prior knowledge and experience, as well as logical implications of the respective model.

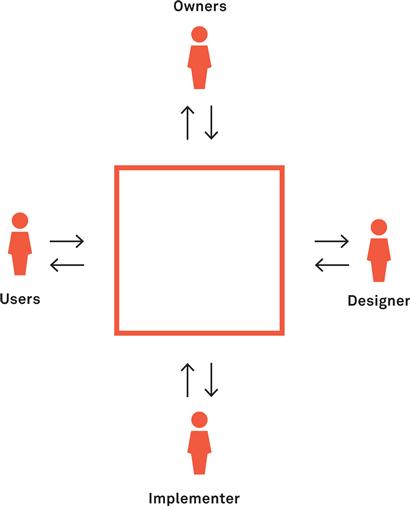

Expanding on an early definition from Don Norman and Stephen Draper in the context of designing user interfaces for software products, there are a number of conceptual views on a system that can be subject to structural modeling in an Enterprise Design context. They can be mapped to the actors addressed and the roles active in the project, and aligned with findings from other perspectives:

THE USERS’ MODEL

describes the enterprise’s structure the way they are understood by its target groups. in most cases this type of model understands the enterprise as a black box, with only a certain parts of the overall structure being exposed to the people it has been created for, embedded in an existing context. The focus is to capture the mental model of people, so that such models often are incomplete and incorrect, being constructed in a person’s mind based on observations, experience, assumptions, and superstitions, and embedding the system into structures from the individual environment it is used in.

THE OWNERS’ MODEL

contains the structures important to the enterprise as a system, based on the views of business stakeholders—actors involved in making the enterprise work. This might include various concepts such as units, offerings, activities, events, competencies, or key partners, focusing on assets, resources, and infrastructure that ensure the viability of the business. it often has a significant overlap with the corresponding users’ models, but includes also background structures invisible to the outside world of customers.

THE DESIGNER’S MODEL

is a conceptual representation of a system as it is designed by a designer, someone envisioning and planning its structure. it describes the system, its components, and their relationship as the designer intends them to appear and act. The focus of a designer’s model is to structure things in a way that they make sense for users and owners as a coherent whole.

THE IMPLEMENTER’S MODEL

captures a system in the way it is built or developed, detailing the technical, operational, and organizational structure in sufficient scope and detail to plan its implementation. The focus being feasibility of a new or evolved system, an implementer’s structural model describes the technical components and operational details put in place to bring the design to life, usually widely hidden from the system’s users.

Example

As an example for the structure frame applied, imagine a design project for a hotel. Some essential structural objects playing a role in the business come to mind quickly, such as rooms, beds, or keys. Thorough design research will result in many objects not quite so obvious — think of abstract objects like reservations or requests, elements outside the realm of the core service like a hairdresser, or even things outside the hotel but relevant to guests such as a bar nearby that serves good drinks, but also produces noise. Other structures could be invisible to guests but equally important to the business and personnel, like staff rooms or the cleaning plan. All these objects are potentially an important part of the design.

Regardless of the focus, creating a good structural model depends on working with domain experts, people who have a profound knowledge and expertise about the domain targeted with a design initiative. Depending on the individual project, those experts can be users of the system being designed, stakeholders, or external actors. Their role is to enable an understanding of the problem setting, making the models relevant and close to reality. With their help, a designer can iteratively refine the structural models, closing the gap between the different conceptual models and the designer’s model, and preparing the subsequent implementer’s model.

The Enterprise as a Structure

In an Enterprise Design project, the diversity of stakeholders makes an overarching structural representation very valuable when seeking alignment of their various concerns and ideas. The structure frame captures the enterprise as a system to be understood and transformed by rearranging and modifying its constituent parts. Any outcome of a design project is an evolved structure, introducing or removing elements and changing their associations. Such a redesigned structure can be described explicitly in a designer’s model, including references to the way the enterprise is structured as a whole. This is again where the ubiquitous qualities and elements described earlier come into play.

The enterprise features structures and substructures related to the three ubiquitous qualities, which can be described and mapped out in structural models to inform design decisions:

IDENTITY

elements in the enterprise that constitute identities relevant to the design initiative. Such elements are often named in the users’ or owners’ conceptual models, formally introduced as brands or just there, such as organizational groups, products, trademarks, or tools.![]()

ARCHITECTURE

elements that make the enterprise work as a system and are related to the design challenge, such as essential services or processes, organizational entities, technical systems, or infrastructure elements, either visible to actors addressed or hidden from view.![]()

EXPERIENCE

objects introduced by the enterprise that appear in the user’s lives and minds, playing a role to make a design achieve objectives toward its target group. This includes physical products and environments, but also brands, services, or messages as things.![]()

Relationship elements on an anatomy level can be mapped to objects in structural models. Including those elements permits capturing relevant structures in individual human-enterprise interactions:

ACTORS

people interacting with objects in the context of a particular relationship to the enterprise, to perform a task or activity.![]()

TOUCHPOINTS

instances of objects appearing in a certain situation, enabling exploration of the level of object visibility and access required.![]()

SERVICES

objects introduced by the enterprise that make available a benefit to actors, such as a website, software tool, or physical store.![]()

CONTENT

the way objects are represented in documents, communications, or other types of descriptions at a certain touchpoint.![]()

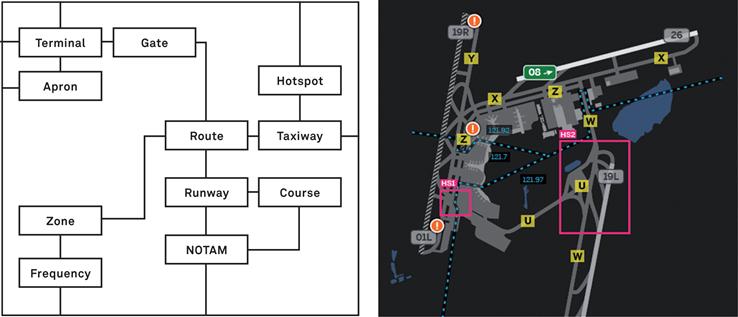

Domain-Driven Design

in the area of software development, a common practice is the construction of structural models as a basis for the implementation of a software solution, known as object-oriented analysis and design, or domain modeling. The goal of such activities, done either before coding or in parallel, is to capture the problem setting in a level of detail that permits an accurate representation in an information system, implemented separately from the other development concerns such as data storage or the presentation of information on a screen.

A key concept in that regard is the domain where that software will be applied. Any context of application can be a domain that applies to a piece of software: the structures, logic, and rules behind its function and behavior. The domain is driven by the concerns of business stakeholders and users, and the problem they want to solve with the software — examples for domains include industries such as banking and healthcare, but also personal settings such as managing a music collection, or the fictional world behind a role-play game.

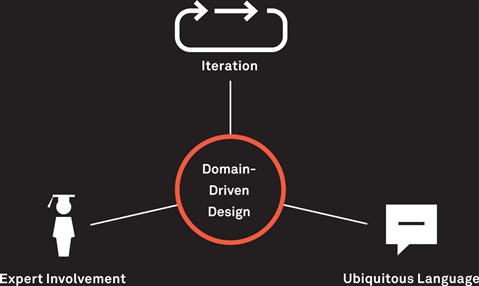

in his book Domain-Driven Design, development expert Eric Evans introduced a framework of the same name. The core idea of DDD is that the domain should drive the design process, since it represents both the real-world environment where the outcomes will be applied, and the conceptual models in the minds of people. This paradigm is used to achieve an alignment between the problem setting and the proposed solution, on a fundamental level that is neutral to any technology or technical implementation paradigm.

The DDD methodology is used for domain modeling in the context of complex software development projects, applying 3 key principles:

EXPERT INVOLVEMENT

any model is based on an active exchange between the designers of the solution, and experts in the domain. By discussing the details of problems and sketching out models together, they collaboratively generate knowledge about the things important to the design, and develop structural models to capture those findings. These models form the basis for developing a designer’s model that fits.

UBIQUITOUS LANGUAGE

one of the key challenges of such interdisciplinary work is one of language. Experts and designers know about different things, have different concepts in mind and use different words. one goal of domain-modeling as used in DDD is to develop a common language based on the model, where every term has a single and clear meaning. This shared language is used in communication, in documents, and as a universal naming convention.

ITERATION AND REFINEMENT

there is awareness in DDD that no model can actually represent a domain as a whole, so that the choices made during modeling are in part analytic and in part subjective statements of how things should be. instead of a single modeling phase, the domain definition is continuously improved and refined during the design process. This involves discussions and co-creation with experts, application in models and prototypes, and ongoing adaption of the model to reflect the latest thinking.

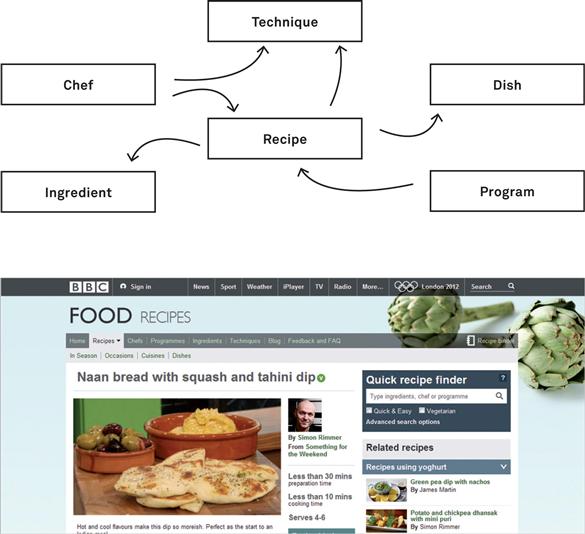

Example

Although originally conceived for software development, Domain-Driven Design is applicable to any project that deals with the transformation or representation of things. In a project for the BBC, Mike Atherton and his team applied the same technique to structure a vast amount of content, reorganizing many of the website’s main sections. Abandoning the tree-like hierarchy of many websites, it takes the connections between things from a user’s model as the basis for navigation and page composition, creating pathways between related items. This way, the navigation model applied fits much better with the user’s mental model, and allows for dynamically pulling together content into useful chunks. By starting from a domain model, the design process at the BBC were able to explore topics as diverse as food, music, and films, guiding the design process independent from the representation of content. Instead of pages and screens, the design team contemplated the actual role these objects play in their business and the lives of their audience.

People think about the things that matter to them, not the documents or records that describe those things.

Mike Atherton, User Experience Designer

Designing with Structure

Modeling the objects relevant to a design challenge provides a powerful foundation for a design project. It allows us to document every relevant object and its relationship to other objects, and even to include the potential results of the design process as a part of that structure — exploring how the world is represented in the design, and how its outcomes integrate into the world.

Applying design on an enterprise level means dealing with a problem setting that shares many characteristics with that of software development in a specific domain. Therefore, the core principles of DDD described by Eric Evans also apply to any difficult design challenge in the enterprise context. The enterprise can be seen as a special case of a domain — especially in large organizations, the jargon used, the constraints imposed and the hidden structures to be considered form a core area of interest for the designer. The creation of structural models in close collaboration with experts helps us find out about the issues, rules, relationships, and concerns.

The outcomes of a design project, all of the things that have been envisioned and produced, have to blend with the real-life context where they are introduced. The structure frame in Enterprise Design helps us explore that context and make structures visible, and to consciously decide on the objects introduced, their designation and attributes. This forms the basis for defining a new state that fits with the conceptual and mental models of people addressed with the results and other stakeholders.

Designing with Frames

A key objective of the Enterprise Design framework described in this book is to apply a holistic and global view to the complex environment that design projects face in the enterprise. As opposed to purely user-centered, business-driven, service-oriented, or similar design paradigms, it aims to provide a vocabulary and approach without imposing a particular focus or main area of interest. That combination of non-focus and a wide range of aspects covered is based on the central idea of taking into account everything that matters, of overcoming the silos, biases, and preconceptions that appear naturally in any multidisciplinary team or diversified stakeholder community.

The four aspects described in this chapter are applicable as universal perspectives, to frame the problem to be solved and reach a global view. They appear in any design project at least in an implicit way, as the ideas and mental models of the project team, and normally they are at least partially made explicit in research findings, concepts, requirement documents, graphical models, or other types of deliverables.

The complexity of the enterprise context makes it worthwhile for us to consider each of them in a more systematic fashion. In essence, the frames help us model the enterprise as a system. Such models can then be used for exploration, synthesis, and concept development to transform that system during the design process.

Although one of the aspects is called people, in fact all of them are intrinsically human, relating to different but related concerns of the people addressed by or involved in the activities of the enterprise. They describe the same system from different points of view, exploring the enterprise as design context, envisioning the way outcomes might transform it, as well as measuring results against the expectations of different actors. They help us deal with the ambiguity of the design challenge by providing frames for both exploration and conceptualization.

The four aspects capture the enterprise as a system, looking in detail at the different aspects relevant to a strategic design process:

THE BUSINESS FRAME

results in models of the enterprise as an economic system, which envision change in terms of business models, markets to address, and opportunities to seize.![]()

THE PEOPLE FRAME

helps to create models of the enterprise as a social system, in order to develop insight into the lives of people impacted by a transformation and adapting outcomes to them.![]()

THE FUNCTION FRAME

sees the enterprise as a procedural system, and allows modeling goals and processes, how the enterprise fulfills its purpose today and how it could work better tomorrow.![]()

THE STRUCTURE FRAME

helps to model the enterprise as an organized system in terms of objects and their relationships, to envision an evolved system and make it fit into the context around it.![]()

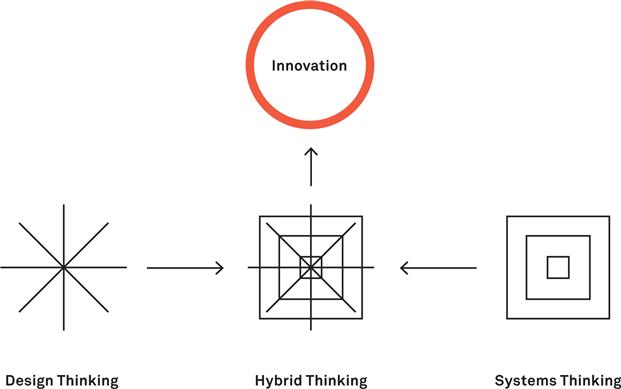

The aspects portrayed in this chapter are thinking devices for dealing with complex design challenges in the enterprise. Applying them requires constantly switching between different modes of thinking:

SYSTEMS THINKING

to explore constraints and dynamics, looking at a problem as part of a larger system and consisting of subsystems rather than in isolation, and defining the context and conditions of the enterprise as a system.

DESIGN THINKING

imagining the future of the enterprise based on various sources of inspiration and creative exploration inside and outside the given system, applying iterative refinement and collaboration to generate and validate ideas.

HYBRID THINKING

bridging both states of mind to synthesize opportunities for innovation in the enterprise.

Closing the Gaps