7

Design Space

Any strategic design project in today’s enterprise environments has to deal with the challenges of a dynamic, uncertain environment. Shifts of an economic, political, technical, or social nature are forcing organizations to reinvent their business models in ever faster cycles of change, to transform themselves into new configurations, learn new capabilities, and address new markets. The ecosystem they address and thrive in is constantly changing, forcing the enterprise to adapt. One of the major hurdles to coming up with a strategy that responds well to new conditions and opportunities is the issue of coherence — aligning the internal activities with external market reality, and thinking beyond individual departments, professional disciplines, or competences.

Design applied to strategic purposes can be seen as a practice of developing just such a coherent a plan for the active part of change, of deliberately introducing new things into a given situation with the intention of transforming it to a desired state. In general, design is about arranging and reshaping the world in a way that it makes sense to people and stakeholders, as business models, as products and experiences, as units of structure and function. Instead of attempting to analyze and optimize the existing, it promotes combining creative leaps with informed synthesis to a discover and make visible the desired target state.

A deep understanding of the environment and the driving factors behind a strategic design project from different perspectives, as described in the previous chapter, is the basis to get a clear picture of the challenge to be solved. It enables us to choose which themes to address, and usually also initiates a number of ideas for potential outcomes. At this point, the focus shifts from inquiry to conceptual thinking.

In essence, those framed models deliver the elements to be included in a desirable future state of the enterprise, defining it as a vision to be executed. What is missing from that vision is a definition of the way those elements work together as a system. To come to such a coherent vision, design teams have to bridge multiple divergent views and cross-cutting concerns, by aligning the different frames and mapping their intersections. The following six conceptual aspects help us to achieve such an alignment, to pave the way to defining the outcomes of a design initiative.

Cross-cutting concerns in Enterprise Design

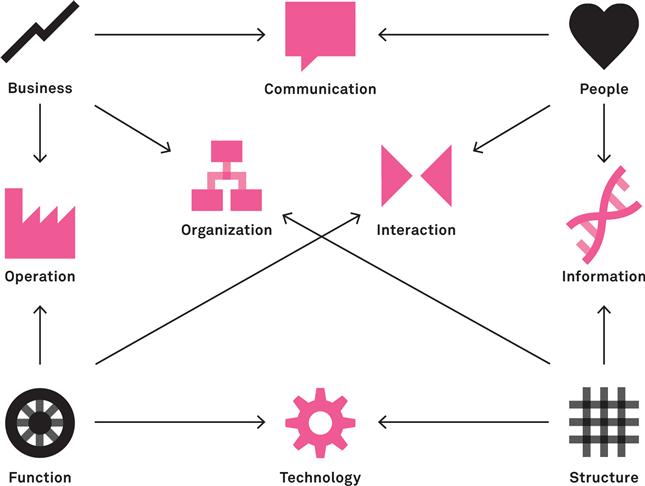

This chapter describes six interrelated aspects which together represent the space of conceptual decisions about a potential future state of the enterprise. Those aspects are information, interaction, communication, organization, operations, and technology, representing significant fields of innovation in strategic design. Each of them corresponds to an area of strategic thinking and alignment with the overall strategy for sustaining and developing the enterprise, and helps us respond to important external trends and identify internal opportunities.

Any transformation of the enterprise means triggering a shift in the way these aspects are addressed, envisioning new ways of doing things and dealing with change. They act as bridges between the different frames applied, to align diverging views and stakeholder concerns and bring their interests together in a common conceptual vision. Depending on your background and experience, there are probably many considerations described in this chapter which you already address as part of your professional practice — whether or not you would call what you do “design work.” Others are perhaps less familiar or generally seen as outside the scope of your work.

When aiming for a strategic impact on the enterprise level, the interrelationships and dependencies between these aspects make them all relevant to design work. In this framework, all aspects are based on connecting and aligning at least two framing aspects from the previous chapter. This means that the conceptual vision must be achieved by framing the problem, deciding on how to design according to different aspects, then applying these decisions on a system of interrelated outcomes.

The conceptual aspects to be addressed in the Enterprise Design framework are the following:

COMMUNICATION

![]() is about the ongoing exchange between people in a business context. In today’s design work, designing communication — in terms of both messages and media — is heavily influenced by the interconnectedness of digital channels, with Internet and social media having turned markets into spaces for rapid and dynamic conversations going on in the enterprise.

is about the ongoing exchange between people in a business context. In today’s design work, designing communication — in terms of both messages and media — is heavily influenced by the interconnectedness of digital channels, with Internet and social media having turned markets into spaces for rapid and dynamic conversations going on in the enterprise.

INFORMATION

![]() is being made available to people about the things that matter to the enterprise (its structure). Designing information is about providing the right things to the right people at the right time, also influenced by the development of digitization and the difficulties of drawing out meaning and gaining knowledge from ever more quickly growing mass of data.

is being made available to people about the things that matter to the enterprise (its structure). Designing information is about providing the right things to the right people at the right time, also influenced by the development of digitization and the difficulties of drawing out meaning and gaining knowledge from ever more quickly growing mass of data.

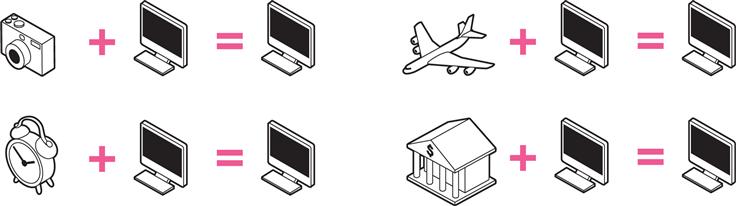

INTERACTION

is about connecting people to functions they are using in the enterprise realm. Designed interactions are omnipresent in the enterprise, where virtually no activity is carried out without the help of digital technology and tools. shaping interactions as behaviors therefore is a basis to define and design useful tools, which are supposed to facilitate them.![]()

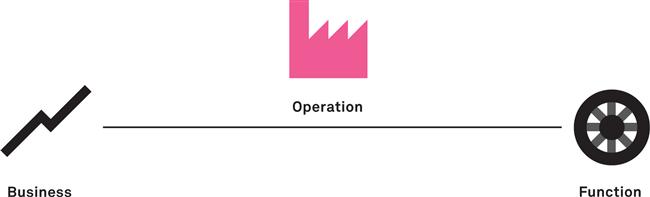

OPERATION

refers to the way the enterprise works and carries out its activities, making use of the functions as capabilities playing a role in ongoing business processes. This aspect is about designing both automated procedures and human work, striving to rethink the way work is being done in terms of both internal efficiency and customer value, defining the flows and drivers behind work processes.![]()

ORGANIZATION

is about the structure of a business, put in place to allocate responsibilities and tasks across organizational units and roles, and building and managing teams. strategic design projects require us to take into account the shape of formal organizational structures, skills and competencies, and their influence on emerging team culture and working habits.![]()

TECHNOLOGY

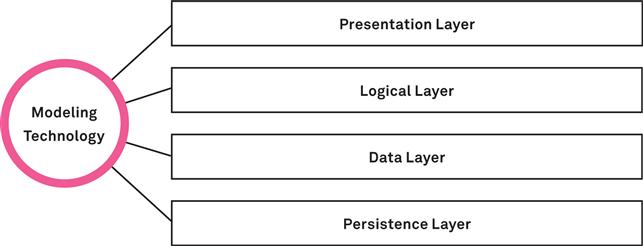

is a means to enable the delivery of enterprise functions, facilitated by the structures put in place to support them. Nowadays any design project depends on a creative usage of technology, playing a vital role in most human activities to be addressed. Designing technology means leveraging technical possibilities for human usage, and shaping it in a way it fits.![]()

#12 Communication

Markets are conversations.

The Cluetrain Manifesto

The arrival of the internet and new forms of digitally supported conversations has transformed and amplified our communication habits. Formerly separate channels of mass communication such as TV and print are converging with instant one-to-one channels such as phone calls or email. New communication platforms appear for specific forms of private or work-related, instant or continuous communication, for various purposes from team collaboration or instant messaging to online dating, auctions, or sharing pictures.

While some communication platforms already play a vital role in the lives of millions, there is a large number of much smaller and more specialized communities and tools appearing. The Internet and its various communication tools provide the user with an enormous choice of platforms and media, and hundreds of competing modes of communication with other people. These communication spaces are closely related and intertwined, with messages transcending the boundaries between them by repetition, syndication, and transformation. People select from those spaces for a particular communication activity based on goals and habits, heavily influenced by local culture and specific group conventions.

Today, we see organizations of all kinds struggle to adapt to this new reality. Traditional Corporate Communications, Advertising, and PR practice has focused on unidirectional mass communication and its indirect influence on reputation and sales success, and has considered the dialogues among individuals as out of scope. The advent of dynamic digitally supported communication spaces removed the boundaries between mass and personal communication, resulting in connected and converging media. In a way, modern enterprises can be seen as a communication space much like communities and platforms on the web—a dynamic community of participants exchanging with each other, across multiple contexts, tools, and communication modes, and with varying reach.

This aspect is about providing the right communications using adequate and useful channels. In the enterprise context, this translates to the fundamental challenges of appearing and participating in these exchanges, as well as facilitating communication with adequate channels and modes. Any business success is the result of communication processes, these being the prerequisite for actual transactions to take place. This requires a dialogue involving customer communication and Marketing, internal collaboration as well as coordination with all suppliers or business partners involved, making the case to invest in modeling and designing communication in the enterprise. It also requires constantly monitoring what is going on in that space, and actively and coherently participating in conversations when they are happening.

Example

To send a message to a friend, people have the choice of a large variety of communication channels and modes, from giving a call or sending a short message or email, to private or public messages via twitter or more special forms such as a greeting card, or even sending a letter on paper. the channels available and considered appropriate vary depending on the context. For example, many people in Japan never had to distinguish between mobile short messaging (sms) and email, since sending and receiving email was supported by most phones much earlier than in other countries. Building on a service similar to email, Facebook allows invitations for events, supporting tailored interactions such as Rsvp. However, the complexity of this function made people accidentally invite the general public, turning private birthday parties into overcrowded mass events and causing the German government to consider prohibiting Facebook events altogether.

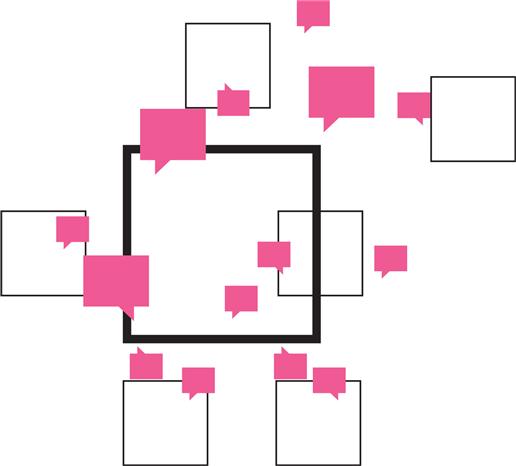

Modeling channels and messages

Based on a large body of research in semiotics, social sciences, and communication theory, models that capture communication processes describe both the nature of the dialogue and the community of participants engaged in it. They help designers for developing an understanding of the ongoing or potential conversations, topics and trends, social interaction modes, and communication needs. Communication models usually describe cycles of social interaction and feedback loops. These models provide a basis to develop a communication strategy by envisioning a future dialogue, and formulating the messages to convey. They capture the enterprise as the business context for an ongoing dialogue between people. In such a model, the social dimension is not regarded as separate from the purchasing decisions and transactional business activities, but as the driver behind them. Designing effective communication channels and good messaging requires us to understand the potential social structures and communication processes, based on insights about people and how they relate and interact.

The communication aspect in design by nature deals with a complex environment where effects are hard to predict. With the myriad of communication modes available today, the design challenge moved from developing and conveying a message to leveraging and redesigning media that effectively facilitate social interaction, while at the same time supporting the goals behind a design initiative. In essence, models about the communication process should not only illustrate how to convey a message to a target audience, but also define the channels and media to facilitate a dialogue and engage in it.

The communication aspect in the Enterprise design framework is driven by two frames portrayed in the previous chapter:

PEOPLE

the foundation of designing for communication is learning about the intended audience to engage, inform, persuade, attract or inspire. Knowledge about identity, interests and motivations, relationships and groups allows tailoring channels and contents. Further, a deep study of the participants of the ongoing dialogue reveals insights about the cultural background that applies in terms of social norms and habits or the repartition of power and influence.

BUSINESS

for all activities going on in the enterprise as a functioning ecosystem, communication processes are the basis. Applying the business frame allows mapping that ecosystem as a market space and capturing the dialogue behind the business transactions. it enables us to understand the economic motivation of market players, and to envision a communication strategy that connects the right actors, positions offerings to the market and facilitates relationships and trust.

In 1948, political scientist Harold Dwight Lasswell formulated his famous model of communication, serving as the archetype for many models to follow:

Who says what to whom in what channel and with what effect?

COMMUNITIES / WHO OR TO WHOM?

modeling community structures describes groups addressed with and involved in communication activities, and apparent social roles. Design projects have to identify and address leaders, followers, moderators, considering interests and motivations, sub-groups, barriers, and relationships.

MESSAGES / WHAT?

the messages communicated, encoded in signs and their meaning (semantics), relationships (syntax) and pragmatics (interpretation). Design is about facilitating reception and reaction, considering media and message format, style, metaphor, and narrative.![]()

MEDIA / IN WHAT CHANNEL?

media are the basis for a communication process by providing means for senders and receivers to engage in an exchange of messages and feedback. In that context, design helps m to support the choice of media by identifying and providing media platforms to engage in, and applying suitable interaction modes.![]()

CONVERSATIONS / WITH WHAT EFFECT?

communication is always aiming to produce an effect on the intended audience. Modeling conversations allows describing how media are used to receive information and again participate in an ongoing process. Such a model captures how social interactions among participants are happening over time, including triggers for activity and feedback loops.![]()

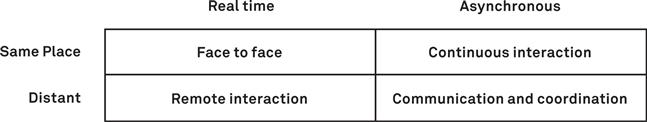

To describe communication media, it is useful to distinguish between different fundamental modes. A model developed by Robert Johansen in 1988 to describe the circumstances of computer-supported cooperative work (cscw) captures the different contexts of communication in time and space:

FACE-TO-FACE INTERACTION

participants are in the same place and interact directly — think of a team using a white board installed in a meeting room.

CONTINUOUS INTERACTION

participants share a place but frequent it at different times — for example a war room or a shared blackboard.

REMOTE INTERACTION

participants are in different locations but interact in real time — such as phone calls, virtual meetings or other live channels.

COMMUNICATION AND COORDINATION

participants are in different locations and interact asynchronously — think of web-based media such as discussion boards or feeds.

Built and sustained by communication, “social” emerges because people like and get along with each other. That’s what the water cooler is for, and why the water cooler is no sooner going away than is the oasis that punctuates the barren passage.

Adrian chan

Designing conversations

As communication is a fundamental part of any human activity in the enterprise, strategic design projects depend on getting that aspect right. Regardless of whether the intended outcome is a product or service, internal change or other types of transformation, success depends on engaging and involving people. Therefore, both the channels used and messages conveyed are subject to conceptual design, keeping the intended audience and their conversations in mind. In that context, designing communication involves mapping the enterprise as communication space, identifying existing platforms and adequate modes of interaction, and extending these platforms with media tailored to particular communication needs.

Communication Design

The term communication Design is used in different ways and with various meanings across the design community, from being just a synonym for graphic design or visual communication, to a systemic initiative of defining the entirety of media and messages in a given social environment. At the core of the disciplines are the encoding and conveying of messages, such as in advertising campaigns, adapted to the now scarce resource of human attention and comprehension.

Designing communication applies in large-scale product launches as well as on the level of projects or teams. Both approaches, the traditional and the social model, are valid for designing communications. instead of being applied in isolation, they are increasingly converging, with conversation topics being triggered by large-scale communications requiring organizations to be prepared to follow up in individual dialogues. this comes with a certain loss of control and the need to take into account the reality of social dynamics in communication, but also contains the opportunity to establish real links to people important to the business.

While the classic practice of communication design is based on a model of mass communication, evolved communication strategies take into account the new reality of hyper- connected people and markets.

Depending on the project, the steps of a Communication Design process may involve different activities:

SELECT MEDIA

selecting and designing adequate media and modes as the environment for the communication process to happen. This may involve mass or personal media, visual or auditory communication, print or interactive, classic or new tools such as annual reports or social network platforms. It might also involve inventing and developing entirely new platforms for social interaction.

FORMULATE MESSAGING

designing and producing the content to convey to the audience across the chosen range of media, including a narrative basis, defining the key messages, and elements of the communication that vary according to different audiences. This messaging concept is the starting point for all further conversations.

PLAN DIFFUSION

publishing the content and bringing it to the intended audience, defining the timing, frequency, and reach of the communication activities. Depending on the individual strategy, this plan might be centrally organized or building on network effects, be planned long in advance, or be adapted based on opportunities.

ENGAGE AND EXCHANGE

preparing for the impact of a communications initiative. This might involve collecting metrics or feedback and adapting communications accordingly, or engaging with participants in personal exchanges according to a set of rules and incentive mechanisms.

Communication In The Enterprise

IDENTITY

![]() how to encode the brand message in communications in a way that it supports organizational identity, and building trust and reputation in the marketplace.

how to encode the brand message in communications in a way that it supports organizational identity, and building trust and reputation in the marketplace.

ARCHITECTURE

![]() how to support communications with adequate and useful media and technologies, responsibilities, and operations.

how to support communications with adequate and useful media and technologies, responsibilities, and operations.

EXPERIENCE

![]() how to design media and messages to reach and engage people, and to adapt to their communication needs and interests.

how to design media and messages to reach and engage people, and to adapt to their communication needs and interests.

Actors

![]() who to address with communications as audience for directed messages and participants contributing to an ongoing dialogue.

who to address with communications as audience for directed messages and participants contributing to an ongoing dialogue.

TOUCHPOINTS

![]() where and when to deliver, tailor, and format messages to participants or recipients, and how provide adequate ways to respond.

where and when to deliver, tailor, and format messages to participants or recipients, and how provide adequate ways to respond.

SERVICES

![]() what communication processes and platforms are needed to support the ongoing service provision via the touchpoints.

what communication processes and platforms are needed to support the ongoing service provision via the touchpoints.

CONTENT

![]() what are the messages to be exchanged in communication processes from the different actors.

what are the messages to be exchanged in communication processes from the different actors.

The enterprise as a bazaar

Designing for communication in the enterprise requires developing an integrated approach for all messages and conversations, including formal and informal communication, small and large scale, short and long term. This applies to the exchanges with market players as well as to the internal communication processes of organizations involved.

In some ways, the enterprise is like an oriental bazaar. Different market players promote their offerings and interact with each other to agree on doing business, with communication being the mediating force between them. The mechanics of such an environment are complex and interwoven—price, placement, and decisions are all dependent on to the dialogue between customer and vendor.

Dealing with the communications aspect in a holistic fashion means designing how the enterprise talks to itself — people involved in its activities — and about itself in the markets addressed. The established forms of advertising campaigns and classic corporate communications will prevail, but merely as a means for reaching a large audience to get the actual conversation going. With today’s large and hyperconnected communication platforms, these conversations are subject to complex social dynamics and network effects that are hard to predict. There have been numerous cases where companies were surprised by the speed, reach, and consequence of social interaction. Designing communication enables organizations to participate and have a say in ongoing conversations in the enterprise.

#13 Information

Information is constantly becoming more relevant in our daily lives. With the shift from print media to digital information and the Internet, we got used to being able to learn just about everything in an instant. But beyond the classic range of digital media, information is now available on a large variety of devices across all our activities and contexts of use, from the smartphone we use while on the move, to the projected interfaces and augmented reality used in professional settings. Essentially, information is everywhere, with tools like Google pulling it out of a hidden space whenever we want it. While this development in many cases makes life a lot easier, the sheer mass of information and its ubiquitous availability across touchpoints multiplies the challenges of organizing it in a way that it is useful to people.

In the enterprise, virtually everything being done requires the acquisition and processing of information. Management decisions, Marketing communication, customer purchases, collaboration between various actors and daily business operations: all activities obtain, use, and produce information, and both human and automated decision making depend on its availability and quality. The acquisition, processing, management, and consumption of information form the basis to run and develop the enterprise.

The challenge of dealing with information is particularly present in today’s business environment, as information and data can prove quite difficult to tame. In many cases, it is scattered across the organization, managed in divisional silos, and reproduced or reorganized on local levels. At the same time, information is floating outside of organizational boundaries and controlled systems, being shared with customers and business partners in the wider enterprise environment.

In their book Information First, Roger and Elaine Evernden argue that in order to address that challenge, organizations must treat information as a business resource, much like capital or labor. They require expertise and strategic thinking to use that resource as part of a business strategy, and to leverage its potential. More than just data to be used in operative processes, information must be seen as the essence of all decision-making and knowledge-building efforts in the enterprise, something that must be adapted to the people using it and interacting with it.

In a world where digital information systems capture data about everything that happens and store an overwhelming amount of content, it is clear that just adding more information to the pile not only provides little value, but can actually make things worse by contributing to the mass that is already there. Already, people are struggling to find and filter the relevant bits out of the general noise, and the knowledge needed is often hidden like a needle in a haystack. Therefore, all structures and systems have to be based on real information needs, retrieval behaviors, and usage patterns.

The information aspect in the Enterprise Design framework is meant to support designers dealing with that challenge — the problem of making available the right information to the right people, in an appropriate way and format, and at the time they actually need and want it. Instead of further building up the haystack, the design challenge with regards to information is to help people find the things they are looking for, and to provide information that is relevant in context.

Modeling information as design material

In the broadest sense, information represents the world around us, helps us making sense out of it and develop an understanding to inform the choices we make. The words, labels, categories, and attributes we use to convey messages in conversations reveal the large diversity of organization systems underlying our information usage. Information is chunked into groups of genres, industries, quantities, time, or geography, all shared concepts and categories used to facilitate access and enable comprehension.

Applied to a design project, the information challenge translates to a problem of organizing it in a way that makes items findable, comprehensible, and useful to different people. This requires defining, structuring, and classifying bits of information, turning them into nodes in a network of connected elements. As Jesse James Garret points out in his book The Elements of User Experience, such a node can be as small as a single number, or as large as an entire library, depending on the individual context of the design project. If done well, such a classification system answers people’s real questions, shows the way to the next item of interest, and makes information accessible according to actual needs, adapted to the respective context of use.

Based on a deep knowledge and models about both the audience to be reached and the structures to be represented, information can be designed to fit. Organizing principles applied to information are agnostic to particular choices of technologies or media, and can be applied regardless of the individual medium used to convey it. The system can be used for signage in a store, a navigation menu on the web, chapters of a printed catalogue, or something different. In order to create define how information nodes can be accessed, designers have to externalize that structure in models, describing the logic of the underlying classification system.

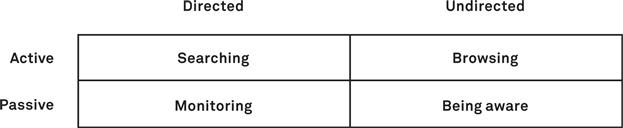

Modeling information is the basis for designing classification systems that actually work. Depending on the individual activity, goals, and context, the strategies people use to seek information vary widely, making the case for a flexible and adaptive classification system. The organizing principles applied therefore have to facilitate different modes of access and usage to support active and passive, directed and undirected behaviors with adequate means of information access.

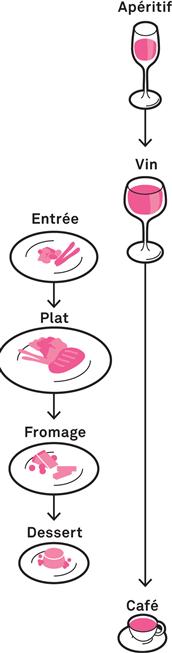

The French dinner classification system

Example

systems organizing information are all around us. some are subject to entire fields of science, such as biological or chemical systems, while others are highly personal. As an example, think about a large music collection. The way to label, sort, tag, and group items in that collection will depend largely on the way the person doing it will listen to music. A fan of classical music might use periods, while someone into jazz or heavy metal could dive into the subgenres. some people prefer to listen to entire albums; others just shuffle through the songs. some might pull out songs for specific occasions, moods, or any combination of the above. whatever system is used, the organized information about the actual items — the songs or albums in the collection—supports its creator in accessing and consuming his or her music. This challenge multiplies when designing an organization system for a larger audience, such as for a store or online music service.

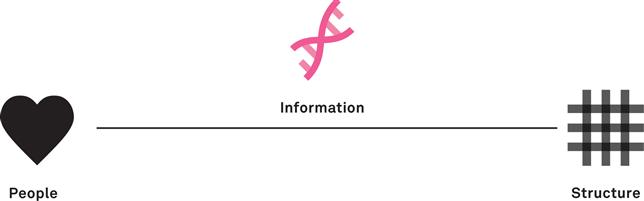

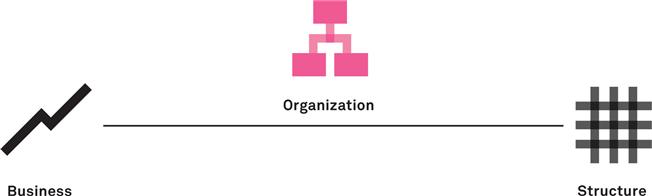

The information aspect in the Enterprise Design framework is driven by combining insights from two aspects portrayed in the previous chapter:

PEOPLE

following the objective of providing information that fits to people’s needs and questions, the insights from applying the people aspect are the starting point to classify and design information. Design uses information to educate, enlighten, or advise people, requiring designers to learn about their information acquisition and consumption behaviors, and to classify and organize information nodes accordingly.

STRUCTURE

the structure aspect captures the things that matter to the enterprise and people in touch with it, and their interrelationships, based on expert involvement and knowledge. Any piece of information is representing a subset of entities which are part of that structure. Therefore, structural models are delivering the basis for organizing information nodes, capturing the underlying domain in terms of entities, language and labels, and relationships and rules to apply.

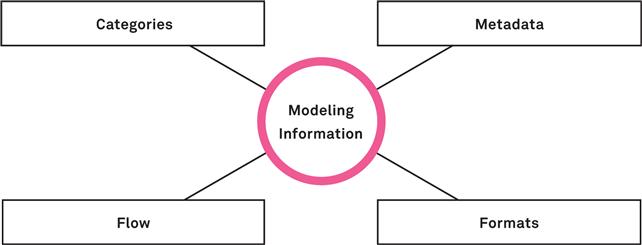

There are a number of different methods to model information, all aiming to formulate structures guiding its organization:

CATEGORIES

help distinguish one object represented in a model from the others, and provide the basis for consistently grouping and labeling information nodes according to their topic. used to guide people to containers of information nodes, a single node might be assigned to a single (hierarchical) category or multiple (faceted) categories.

METADATA

is information about information—the attributes describing it according to different dimensions of classification, such as author, time of creation, genre, size, or tags. Modeling metadata is the basis for making information searchable, or to pull out related nodes in context.

FLOW

models capture how information moves around in a system of some kind and permit to describe their creation, modification, and usage. They are used to study how information is acquired and processed to make decisions, and how it evolves over time.

FORMATS

describe the different kinds of information in a system, the type of media, and the level of structural formalism applied. Models of formats enable us to define the way content is made available, and applying this to the definition of structures, styles, and templates.

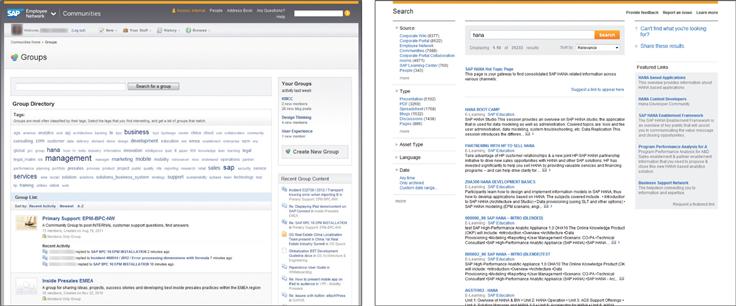

Information Architecture

Certainly, an Information Architect will define the meaning of every element on a website. Because the question of meaning is at the very heart of Information Architecture.

sylvie Daumal

As a professional area of knowledge and practice, information Architecture deals with structuring of information, and the systems and environments that are its containers. coined by Richard saul wurman, the term has been taken up by Louis Rosenfeld and Peter Morville in their book Information Architecture for the World Wide Web from 2001. Beyond a practice applied to websites or business information systems, there is a wide range of schools influencing information architecture practice, ranging from computer science or informatics to library science, linguistics and visualization. in the end, all these different approaches share the goal of leveraging the potential of information and data, turning it into a useful resource, accessible and findable for those who want or need it.

while classic Information Architecture deals with systems such as websites or databases, the professional practice had to move beyond controlled information environments. The new reality of social media and a ubiquitous Internet makes the distinction between new and old media, between providers and users of information obsolete. The constantly growing mass of user-generated contributions makes the issues of information classification and organization even more significant, calling for dynamic and adaptive Information Architecture solutions. This is especially the case for the dynamics and uncertainty of complex enterprise environments.

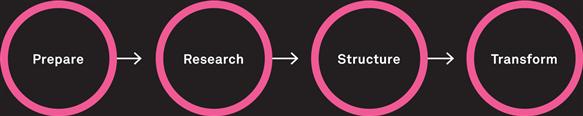

Applied in concrete projects, information Architecture follows a process of exploration and synthesis, often combining top-down, bottom-up, and opportunistic approaches:

DETERMINING NEEDS

gathering requirements and information needs from potential information users and other stakeholders, analyzing how information is currently structured and used. This activity is supported by techniques such as card sorting, working with domain experts and structural models, or looking at existing information repositories.

CLASSIFYING INFORMATION

developing conceptual systems to organize information items. This activity involves developing information and data models to capture the semantics, informing the creation of vocabularies, taxonomies, labeling systems, or logical data schemes. It is informed by information needs derived from the top down, or classifying existing items.

APPLYING SYSTEMS

designing means to find, access, and retrieve information that support different behaviors based on the classification systems. These systems are designed to enable navigation, orientation, and wayfinding, providing relevant information in context. They can be based on a rigorous application of the first two steps, or around information needs as they emerge.

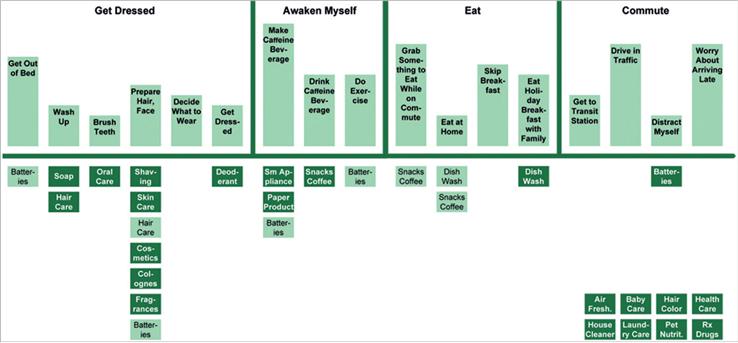

According to American information scientist Marcia Bates, information is only rarely actively sought for, when there is a concrete need justifying the effort. in 2002, she developed a scientific model describing how we find and use information. Her scientific model uses two axes of different behaviors to distinguish four essential modes of information retrieval:

SEARCHING

actively searching for information to answer a specific question, supported by search functionality, indexes, or maps.

MONITORING

passively being alert to notice relevant and interesting information when it appears, supported by alerts or status displays.

BROWSING

actively looking around for information, guided by interests and loosely defined goals, and supported by menus, news, or guides.

BEING AWARE

passively absorbing information during other activities, supported by contextual shortcuts or lists of new or hot items.

Information In The Enterprise

IDENTITY

![]() how to design information to encode brand symbols, language and semantics into categories, labels and structures.

how to design information to encode brand symbols, language and semantics into categories, labels and structures.

ARCHITECTURE

![]() how to design information to support the enterprise in performing its activities and operations, and how to protect information.

how to design information to support the enterprise in performing its activities and operations, and how to protect information.

EXPERIENCE

![]() how to design information in a way that enables perception, understanding, use, and generating knowledge.

how to design information in a way that enables perception, understanding, use, and generating knowledge.

ACTORS

![]() who are the consumers and generators of information in the enterprise, and how to accommodate their journey.

who are the consumers and generators of information in the enterprise, and how to accommodate their journey.

TOUCHPOINTS

![]() where are points of information exchange between actors and the enterprise, and how to create paths between them.

where are points of information exchange between actors and the enterprise, and how to create paths between them.

SERVICES

![]() what information feeds are needed to support service delivery and operations.

what information feeds are needed to support service delivery and operations.

CONTENT

![]() how to design information to chunk, group, and connect enterprise content as information nodes.

how to design information to chunk, group, and connect enterprise content as information nodes.

The value in Information Architecture’s structuring the information in an enterprise is not in attaining some abstract goal of imposing order on disarray but in enabling the provisioning of the right information in the appropriate context to the stakeholders who need it.

Gene Leganza, Forrester Research

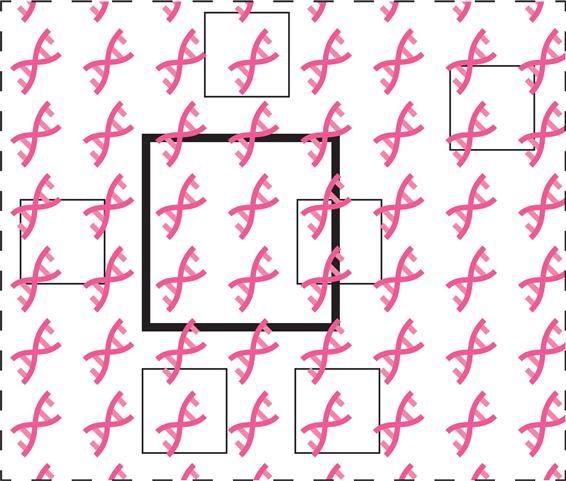

The enterprise as information space

Information only comes to life when applied to a given use context — someone accessing and using it to achieve a certain goal. Therefore, any model describing an abstract organization system is meant to be applied to the design of accessible information spaces, such as electronic archives, web communities, signage systems, or other media. Good models about information provide the blueprints for structuring and connecting information, and ways to organize it in a classification system. To make use of such a system, it has to be turned into perceivable artifacts, delivering information so that it helps us solve the real-world issues of making decisions and developing understanding.

To be applied strategically in an enterprise context, information architectures must be consistent, but at the same time flexible to support varying needs. In practice, this often requires a mix of top-down, bottom-up, and pragmatic approaches to come to an adequate organization scheme. This allows us to balance the role of information systems as a secure and reliable single source of truth, a dynamic and evolving space for social exchange.

The way information is shared, processed, and used requires architectures that span multiple contexts, channels, and media. They have to connect information nodes across the entirety of people’s journeys and business processes, connecting search engines, social media, information systems, and documents. Such a system then is the basis to make offerings findable on the web, inform management decisions with business intelligence, or enable navigation in physical spaces. This makes the underlying organization system similar to the DNA of the enterprise — a consolidated structure for relevant information, a strategic resource when applied in various contexts.

#14 Interaction

From simple tasks like making a call or shopping for an item online to complex problem-solving and creative work, sophisticated tools and devices are a part of everyday life. In fact, they always have been, as using tools to support our activities and achieve our goals is a major aspect of human civilization. In the last few decades, we can see a major shift from the industrial manufacturing of comparatively simple physical tools to a new generation of technology, driven by software and data, embedded in virtually all the products we use.

Such products, both physical and virtual ones, are part of our social and professional lives, supporting us in working, playing, communicating, and learning. Even tools which used to be comparatively simple mechanical or electrical devices now include enough functions, states, and information to make them behave like computers. Compared to the tools and machines of the industrial age or before, these new products are exponentially more complex in nature, as probably earlier using software or electronic devices will have experienced. Software, and the things incorporating it, is famous for not working as expected, being hard to learn and difficult to use.

Interestingly, the modern enterprise as a whole is facing a similar challenge. Businesses have a long history of using software to support and automate their activities—consider the role of machines, data, and automated processes in the enterprise. Within this trend of ever greater digitization, the tools made available to people only got little attention. The same problems of complexity and imprac- ticality are appearing in interactions between people and tools in the enterprise space, hampering business activities and market success.

Digital tools or media are the prevalent mode for interactions in the enterprise, be it customer interactions, collaborative work, or executing operational processes. But still, most of us encounter frustrations in our interactions with even the most advanced organizations, quite similar to our experience with the software-enabled tools we use for our professional and private activities.

The interaction aspect is about consciously and proactively considering the exchanges between people and organizations in the enterprise, and supporting these interactions with automation and tools. It is about shaping behavior as it occurs, by designing the automated part of the dialogue, while anticipating the human part. While it is important to know what’s technically feasible, that is not the driving factor behind modeling and shaping good interactions. Instead, it is the quality of the interactions that make the use of technology a success or a failure.

Modeling interaction and behavior

Learning about the interactions people are engaging in enables designers to consider how the results they produce will be used and to base their design on actual usage patterns. To best support interactions, the design of any tools and systems needs to be based on a solid definition of the dialogue envisioned. Therefore, it is useful to create models of the interactions to be supported as a basis for the design of any tools, by describing the dialogue between tools and their users over time.

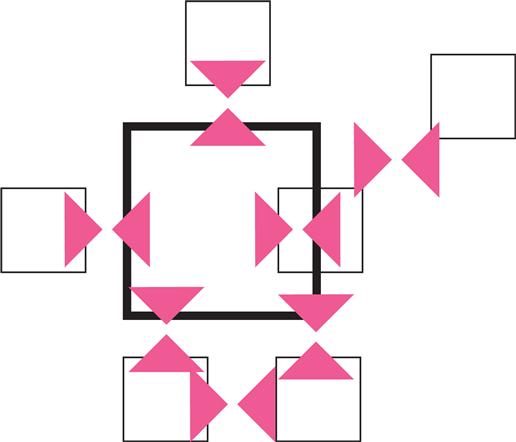

in his inaugural book, The Inmates Are Running the Asylum, interaction design pioneer Alan Cooper describes the effects of introducing computers as part of everyday life—a whole new world of possibilities that comes at the price of a dramatic rise in complexity, resulting in just about everything behaving like computers. Consider these examples from his book:

CAMERAS

that used to be relatively simple personal devices with just about three buttons start to offer hundreds of options and functions, are required to boot in order to work, just as telephones or clocks do.

AIRPLANES

are by now fused with computing technology, and a large part of the emergencies and accidents that have happened in the recent past can be tied to a chain of technical failures, usually in combination with human error from dealing with the mass of data, options, and automation.

BANKS

interact with their customers using online banking and ATMs, making simple transactions such as initiating a standing order to update your address a complex matter to deal with. Instead of a human operator, you are dealing with a computer and following its set of rules.

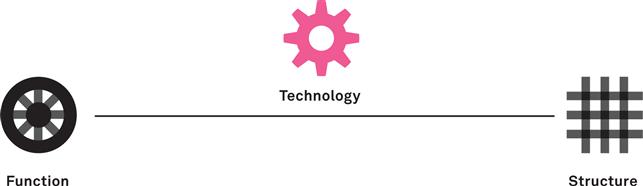

Interactions in the context of the Enterprise Design framework can be seen as exchanges between people and the enterprise, supported by tools or devices that make enterprise functions accessible.

PEOPLE

knowing about who you design for allows insights into the cognitive, physical, and emotional aspects of interactions, and lets us design the dialogue between a tool and a user accordingly. This involves researching, understanding, and modeling people’s activities and motivations. Interaction models are based on these factors to determine the tasks people will attempt to solve with an interactive tool, the strategies, methods, and habits they apply, and scripts applying to the dialogue to be created.

FUNCTION

interactions in the enterprise space are happening in the context of a wider system of actors involved in business processes. Applying the function frame permits us to determine the behavioral topics behind an interaction. Interactions have to support the functional context of goals and processes by meeting defined requirements. They make any functional components in the enterprise accessible to people, supporting the wider purpose to be fulfilled.

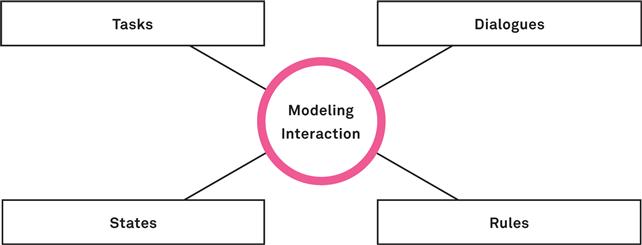

Techniques for modeling interactions have their roots in the areas of Human-computer Interaction (Hci) as well as applied psychology, cognitive science, and ergonomics:

TASKS

are models about activities users perform to reach their goals. They are usually represented as steps to be taken in sequence. Additionally, they might contain different variants of a task flow, points where decisions are being made, information about the complexity or repetitiveness of an activity, or typical scripts and routines.

DIALOGUES

represent the interaction between a user and a system in the form of questions and responses. A common notation of dialogues is as a swim lane diagram, capturing who does what and when in the flow. such a model describes the roles of people and automated components involved, the triggers of user action, and system feedback.

STATES

describe the different conditions presented by the system to be designed to its user, and the transitions between them. such a model us to create a map of all states that have to be considered as part of the design activity, guiding a user from an initial state to a desired end of the dialogue.

RULES

are collections of behavioral instructions to the system, often in the form of if-then statements, in decision tables or trees. Modeling the conceptual rules behind a system’s design captures how it reacts to whatever user input and the automated behavior it exhibits according to a set of environmental variables to be defined.

Example

As an example for your interactions with digital systems, think of the way you interact with your bank to manage your money and your accounts. depending on the offerings and your choices, interactions are supported by an online banking environment, ATMs, and similar machines, as well as by physical interaction with employees in their local branches or via phone. Each interaction largely depends on the tools made available, either to you as a customer or to the staff you are dealing with. while most institutions by now realize the importance of making these tools useful and valuable to their users, they are usually designed in isolation, looking only at people-tool interaction instead of the bigger picture of customer-bank interaction. Problems such as call center staff unaware of requests made online are due to the missing links and transitions between the interactions.

Models of interactions allow us to describe the dialogue between a system and its users, in order to anticipate the behavior on both ends. They capture the interactions in terms of the purpose to be fulfilled, activities and goals to be supported, and the individual contexts where they take place. This enables us to define and describe the desired interactions prior to designing the tools to support them, or even planning to implement them on a technical level. Instead, interaction models give a design team a clear idea of how interactive systems will appear in people’s experiences. In order to create persuasive, useful, and desirable tools, they have to be seen as automated participants in a dialogue between human and machine, designed to shape the interaction as it occurs.

shaping interactions and interactivity

Just like the other conceptual approaches portrayed in this chapter, designed interactions are invisible and intangible to the people they are made for. In order to actually work, they need to be bound with interactive artifacts that facilitate the interaction envisioned. Based on modeling of anticipated and desired interactions, such artifacts can be designed in a way that the choice of technologies, user interface paradigms, and metaphors enable the dialogue to be supported over time, working together to form a coherent whole.

Interaction Design

It is impossible to design interaction pen se, but what interaction designers do is to create conditions for interaction.

Jonas Löwgren, Malmö University (interaction-design.org)

As a professional practice, Interaction Design is a comparatively young discipline concerned with the design of dialogues between interactive systems and their users, or more generally between humans and the things they use as a means to achieve their goals. Compared with the more classic approaches of usability engineering or HCI, Interaction Design puts an emphasis on designing behavior over time as a creative activity. The challenge is understood to be about triggering dialogues and influencing behavior by creating interactive things. Such artifacts are made to accommodate dynamic exchanges with users, taking into account a deep understanding of users and their goals and use contexts, and the possibilities and constraints of technology.

While the outcome of Interaction Design usually is some kind of user interface, Interaction Design defines it rather as an implementation of a more abstract behavioral definition than an independent artifact. Mastering the practice requires a deep knowledge of technology and its promise to enrich people’s lives or solve business problems. Its core area of concern lies in the behavior of the human beings that the technology is being made for. Therefore, turning Interaction Design into interactive artifacts often starts by pretending it works by magic or by people pulling the strings, in order not to get caught up in purely technical considerations too early in the process. The aim behind shaping the behavior of technology- supported products and services is to have an impact on the way their users behave.

An Interaction Design process goes from researching and modeling a certain set of interaction qualities to a specification of the interactive outcomes of a project:

MODEL AND SPECIFY

modeling the interactions to be supported and envisioning ways to facilitate them with tools and systems, based on insights from research and the larger conceptual vision.

DESIGN THE CONDITIONS

design the tools themselves as responsive systems, to be used to support the interactions. This requires a cognitive leap to translate dialogues into interfaces and systems.

PROTOTYPE AND TEST

more than most other design disciplines, interaction Design relies on a trial-and-error approach that emphasizes prototyping and iteration based on validation with future users.

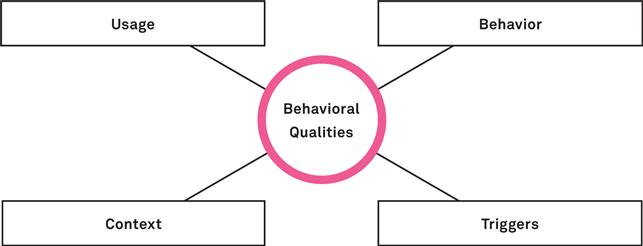

Designing interactions touches a set of fundamental behavioral qualities of interactive systems:

USAGE

learning about people addressed, their activities and usage patterns is a good starting point. it enables the designers to determine different groups such as beginners, intermediaries, and experts, to get a detailed understanding of how the same goals are achieved today and what an interactive tool as an outcome has to do to improve things.

CONTEXT

the individual context of use is the basis for choosing the right means to support the interaction — devices, media, and interface paradigms, for example, audio, websites, or a mobile app.

TRIGGERS

triggers are the concrete means of input and output to be used as part of the dialogue. This includes choosing affordances and metaphors, and turning them into interactive elements.

BEHAVIOR

a definition of the behavior of the system to be designed. This can be done in different forms, but usually includes a procedural description and a set of rules.

Interaction In The Enterprise

IDENTITY

![]() how to turn desired and adequate behavior into designed interactions and dialogues, encoding brand identity and values.

how to turn desired and adequate behavior into designed interactions and dialogues, encoding brand identity and values.

ARCHITECTURE

![]() how to support the activities of the enterprise with interactions, supporting their effective and reliable performance.

how to support the activities of the enterprise with interactions, supporting their effective and reliable performance.

EXPERIENCE

![]() how to make interactions with the enterprises or within its realm, making it useful to people and great to work with.

how to make interactions with the enterprises or within its realm, making it useful to people and great to work with.

ACTORS

![]() who is interacting with the enterprise in what role context to participate in the dialogue to be mediated with interactive tools.

who is interacting with the enterprise in what role context to participate in the dialogue to be mediated with interactive tools.

TOUCHPOINTS

![]() what events are triggering interactions—when and in what kind of context do they appear, and how to accommodate these conditions.

what events are triggering interactions—when and in what kind of context do they appear, and how to accommodate these conditions.

SERVICES

![]() what are the services made available to people in interactions, and what type of dialogue they require.

what are the services made available to people in interactions, and what type of dialogue they require.

CONTENT

![]() what content is being exchanged in interactions and how to support them with instructions, feedback, and contextual information.

what content is being exchanged in interactions and how to support them with instructions, feedback, and contextual information.

Example

As an example, think of the way your company enables people to apply for a job. The interaction starts probably outside the realm of company-owned tools, for example, via a job site, and continues eventually in the career section of your own website with an online application. Both systems can be considered a good subject for Interaction Design. Seen as a whole process, the interaction spans well beyond using these tools to find a job—it involves getting initial feedback by mail, scheduling an interview, and going through a quite long and extensive recruiting process.

Companies are notoriously bad at this, often failing at the first step of sending feedback to everyone who applied within a reasonable timespan. Applying Interaction Design holisti- cally to the wider dialogue enables us to accommodate for this in the design—for example, by supporting HR consultants’ communication with applicants, introducing a tool that reminds them in time and provides the status and next steps of the recruiting process. Although this is a purely internally used system, the impact transforms the enterprises’ behavior towards an external stakeholder group.

The enterprise as a dialogue

Applied on the enterprise level, Interaction Design expands its scope beyond the design of isolated interactive artifacts — it means designing a space for interactions between actors in the ecosystem. Every tool or medium used to facilitate these interactions has to be seen in the context of its wider meaning, as a means to shape the interaction between people and the enterprise and as a way to affect human behavior. This applies to automated components of products and services offered to the market, as well as to internally used tools or systems.

Some leading organizations have tapped into the possibilities of investing in the quality of their interactions, which enables them to deliver a great Customer Experience by providing products and services embedded in a wider system. Instead of isolated tools, customers and other actors are supported by a system of functional elements, designed with their users in mind and facilitating transactions, conversations, relationships, and flows of work. Applying Interaction Design on the enterprise level, deeply rooted in human behavior, unlocks the potential to design more than just usable products and tools — considering the larger dialogue allows us to design enterprise interaction holistically and makes a difference in terms of behavior.

#15 Operation

What from the outside looks like a well-oiled machine is, from the inside, lots of people working really hard to keep up that impression and make it truer each day.

Mei Lin Fung, institute of Service Organization Excellence

The idea of designing business operations has its roots in the idea of operational excellence. It has been developed as part of the lean manufacturing approaches at Toyota and other Japanese organizations, which aim to maximize production quality while minimizing effort and costs and are applicable equally to industrial products and service provision. Efforts in operational design define and plan in detail what is being done, and how it is done in an organization, to produce and deliver its products to the market, and to turn this design into a standardized, repeatable process.

Most people have to deal with large organizations of various kinds, such as phone companies, energy suppliers, or public administration. Airlines transporting your baggage to the wrong destination, after-sales support failing to address your specific problem, mail orders that never arrive, departments unaware of what their colleagues are saying or doing, inability to communicate important information, waiting in long queues—the list of stories of operational failures people have to face is long and frustrating to say the least. Such failures can get downright dangerous in critical areas such as aviation or healthcare.

Despite the long tradition of operational optimization and the advent of digitally supported automation, this is still a particularly error-prone area in the enterprise context. Across all industries, employees feel trapped in narrowly defined processes rather than empowered by them, so they attempt to break out of the system instead of working with it and improving it.

The operations aspect in the Enterprise Design framework deals with the design of all activities executed in the enterprise, tackling the challenge of defining collaboration practice and managed procedures that maximize performance and quality of delivering what the enterprise has been created for. It is the basis for creation or transformation of an operating model of the enterprise, in alignment with the potential outcomes of a strategic design initiative.

Operational design aims to support design teams taking the operational factors into account in projects, to analyze and redefine how business activities are being done to support the larger goal behind the design initiative. To do so, operational designs work towards improving performance across the value chain, identifying and removing unnecessary steps, phases of inactivity, over- or underproduction, defects, or other types of waste. But to make an operating model actually work in real life, this also means making processes transparent to the people carrying them out. It requires empowering them to unlock the flows of work by resolving problems and eliminating errors when they appear.

Modeling operational processes

A model of operations is a definition of the activities an enterprise undertakes to compete in the target markets and deliver products. It is collaborating with suppliers and partners, managing employee relationships, and sustaining its ongoing business. In general, it describes the flow of people’s work and decisions, materials, information, and money through the enterprise’s value chain, starting at a given initial state and aiming to reach an intended satisfactory end state. It reaches across technology, work practice, ad hoc collaboration, and management incentives, and therefore should address everything considered relevant to the achievement of operational goals.

Example

In 2010, one of the largest national railway companies in Europe decided to reward loyal customers with a special promotion, one of them a free upgrade to first class. The upgrade was printed as an icon on the frequent travelers’ cards, entitling the holder to claim the right to pay reduced ticket fares. it was also added as a section to a long public document describing the terms of service.

However, the promotion was not communicated to the personnel effectively, leaving them unprepared to meet customers’ expectations. conductors were unaware of the special offer and did not accept the upgrade card. they humiliated customers by sending them to the lower class compartments or (even worse) attempting to charge a full first class fee. this is a typical example of designing great offerings to customers in the Marketing department, but turning them into a nightmare by failing to taking the operational aspect into account to make it actually work as a process.

Such a model captures the business processes being executed as a series of activities arranged in time and space, and enables design teams to incorporate operational elements in their concepts. Design decisions about operations involve the order and sequence of things being done, and requires us to account for dependencies between activities. Furthermore an operational model specifies ways to deal with any exceptions and deviations to the planned process, allowing people to step in if something goes wrong.

This aspect is informed by insights from the business and the function frames, providing the context for operational design:

BUSINESS

the business aspect reflects the reasoning behind an operational model. Insights from the business model to be implemented allow us to draw conclusions on what to prioritize when designing a subsequent operating model. It clarifies which tasks provide value to the customers, which areas have the highest financial leverage and contribute to market differentiation. It allows us to define metrics as operational objectives, and identifying resources required for execution and exception handling.

FUNCTION

the function aspect is the other main driver for designing operating models. In a way, operation is the coordination of activities directed at supporting the purpose of the business. It is about connecting and orchestrating business functions — or capabilities — helping the enterprise to achieve its objectives, generate value, and work properly. Well-defined functional requirements provide the input needed to identify and connect operational capabilities, detailing what exactly the enterprise needs to be able to do.

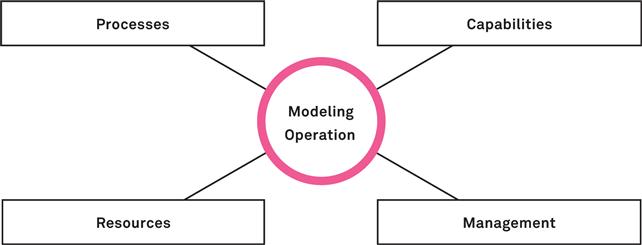

Depending on the industry and nature of the activities, items to capture in an operating model vary. in general, elements fall in these categories:

PROCESSES

the order, sequence, and business of activities and important events, from a starting condition to an end state. The scale depends on the modeling purpose, but can reach from single processes to entire industries from supplier to consumer. it captures how things are done, how to process work, capital, and information along the chain.

CAPABILITIES

the organizational skills and instruments needed to achieve an operational target state. Modeling capabilities allows identifying what an organization has to be able to do in an operating model. Based on a map of capabilities, operational steps can be repartitioned across organizational units. This is also the foundation for local optimization of a capability, and supporting it with tools and technology.

RESOURCES

the finite inputs needed for the operating model to work, such as raw materials, manpower, and capital, as well as the capacities needed to process them to produce the desired outputs. Modeling the kinds of resources that are needed where and when is the basis of addressing questions of planning, transportation and logistics, queuing and scheduling.

MANAGEMENT

the systems put in place to manage the activities, including monitoring and support, initiatives and projects to evolve the operating model, and ongoing controlling and measurement. including the management system in the operating model allows mapping the design to organizational responsibilities, and operationalizing activities such as quality assurance, communication, and security.

Because operations has such a large scope, it is vital to determine what operational factors and details are important to consider in the context of an individual project. This depends on the repetitiveness and predictability of the activities to be done, the degree of possible automation with the help of technology, the expectations of customers and internal stakeholders, and the operational goals. An operational model might cover an entire enterprise ecosystem with processes between a network of intertwined organizations, or just a small subset of activities considered important for the problem at hand. The elements to take into account are consistent independent of the level of detail covered, equally applicable to a big picture model and a detailed process.

Designing work

Many of the disciplines dealing with operational design concentrate on improving the effectiveness of existing operating models using a large variety of approaches. Most approaches focus on achieving better performance, while leaving the existing mode of operation unchanged. They aim at improving the model by wiping out inefficiencies and delays, reducing cost, optimizing resource usage, and generally working towards continuous improvement.

Making the task of developing a potential future operating model part of a strategic design project allows project teams to move beyond just incrementally improving what there is today, letting them look for opportunities to dramatically shift the operational process. As a starting point, such a project usually deliberately sets difficult or unrealistic performance goals, opening the designers’ minds to radical ideas. Key to this is overcoming the paradigms applied in a current operating model — applying design thinking to operations means to radically rethink how work is done and processes are handled.

Business Architecture

Business Architecture enables stakeholders to make key business decisions by taking an integrated view of the business and aligning all the various moving parts in an adaptive 360°model.

Mike Clark

As a professional discipline, Business Architecture focuses on translating strategic decisions and initiatives into structures and systems to be implemented in an organization’s evolved operating model and business functions. Practitioners perceive the enterprise as a dynamic structure of interrelated elements that contribute to maintaining, sustaining, and developing business activities. Applying a Business Architecture approach, this structure is subject to proactive and informed design decisions, providing the link between a defined business model and its execution as a transformation or extension of the operating model.

A Business Architecture approach enables design teams to map out the overall execution of a solution as envisioned in a strategic design — its operating model — as an abstract representation on paper or in a spreadsheet. Sophisticated design paradigms such as Lean or Six Sigma can be applied and tested in such a model as a simulation, trying out different approaches and iteratively validating and refining them in the course of a design process. Once a target operating model has been identified, the team proceeds to encode it in systems, instructions, or other kinds of documentation, as a plan for execution.

The work of Business Architecture professionals consists of a set of interrelated activities, informing the development of business strategy and models, and turning these elements into actionable blueprints of the business:

EXPLORE

the enterprise environment to discover developments and changing conditions or trends that might affect the business model applied, and identify threats and opportunities to inform strategy.

TRANSLATE

strategic initiatives into concrete redesign and improvement projects, defining the evolved business and operating models and communicating changes to other parts of the business.

COMMUNICATE

and socialize with stakeholders the changes envisioned with a new architecture, and advise during its implementation.

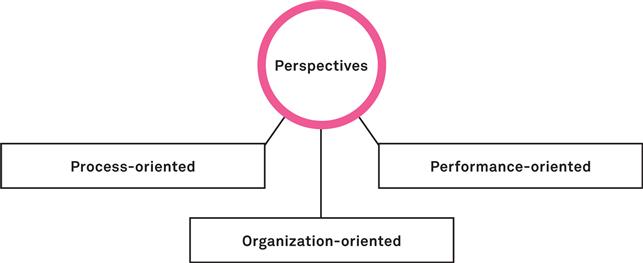

while there is a multitude of domains potentially addressed by initiatives defining the operating model of an enterprise, there is a set of common perspectives used as starting points to such an endeavor:

PROCESS-ORIENTED

approaches see a business as a set of interdependent activities to be executed. They apply techniques from Business process Management and Reengineering to model operations as repeated procedures, sometimes employing operations Research techniques, mathematical models to optimize operations.

PERFORMANCE-ORIENTED

models emphasize on business performance as captured in metrics and goals. such an approach is focused on measuring and improving business performance in numeric terms, using financial models, scorecards, and business Intelligence technology.

ORGANIZATION-ORIENTED

methods model a business as a system of areas, responsibilities, and formal relationships between them. They aim at describing and designing effective systems for governance and work practice.

A design approach to operating models finally aims to reshape human work, supported by systems and tools, rules and incentives, defined procedures and flexible arrangements, making these elements contribute to achieving the goals defined. It also involves specifying and implementing the model into systems and procedures, and also communicating it to people to make it part of their work practice.

An important part of this is a human-centric approach, starting with customers, staff, and other actors, and modeling operations according to the activities and needs to be supported. To be able to envision radical innovation, designers need to explore the activities of people involved in and addressed by the processes to be designed.

The enterprise as a process

In his business novel RecrEAtion, corporate strategist Chris Potts makes the point that although many organizations like to see themselves as the owners of their operational processes, in the end it is the customer who actually owns the process. So instead of designing discrete processes to deliver value to the customers, organizations have to decide how and where they want to appear in their customer’s activities. This then is the basis for designing an operating model that fits.

For the enterprise, an operational design approach can help to rethink its operational systems and subsystems. As the usage of the terms architecture or design in Business Architecture circles suggests, such an approach is actually conceptual design based on insights about people, which makes it very relevant to the goals of any strategic design initiative. It lets us choose an operational mode and to design operations around the role an organization assumes for its customers and other stakeholders.

Operation In The Enterprise

IDENTITY

how can our operating model encode and support the values and behavioral goals embedded in our brand identity.![]()

ARCHITECTURE

how to structure the formal systems in the enterprise to best support the operating model and the ongoing processes.![]()

EXPERIENCE

how to design operations so that we appear in our customers’ and other stakeholders’ lives, support their goals, and provide real value.![]()

ACTORS

who is involved in our operations in what way—what do staff, partners, customers, or other stakeholders contribute.![]()

TOUCHPOINTS

where do we interact with people as part of our operations, and how to turn these exchanges into rewarding opportunities.![]()

SERVICES

how to support service provision to customers and what internal services do we need to provide as part of our operations.![]()

CONTENT

what content has to be communicated as part of operational processes in order to make them work and useful.![]()

#16 Organization

Bringing about organizational change has been a hot topic in management circles for quite a while. The converging effects of group culture and identity, operational processes and planning and organizational politics, and authority make designing and implementing organizational change challenging in the enterprise. This diversity of viewpoints on organizational transformation has produced a wide range of practices dealing with their design and implementation, such as Change Management, Organizational Development, and applied methods like training and coaching.

Any major endeavor in the enterprise requires its organization to evolve and adapt to a new state — introducing new products or services, addressing a new market, or revamping internal operations — developing the business always means destroying existing structures and replacing them with something new. Therefore, the success of a design initiative with strategic impact depends on its ability to influence the organization behind it. In effect, this makes larger design initiatives into organizational change programs, because they have to reach the people involved in delivering the outcomes they intend to shape.

Driven by Marketing initiatives, many companies make unclear promises in their communication to customers. The things that appear in those communications are usually subject to design practice, such as products, interiors, or visual brand identity, driven by a customer-oriented view from the outside. More often than not, there are wide gaps between promise and reality, especially when there is a problem and the standardized operations break down. Equally, many design projects fail because of unclear responsibilities, resistance to change, and ill-adapted organizational structures, especially in the long run after a design project has ended.

In order to make an intended transformation happen in a sustainable way, design projects are dependent on support from many executives, departments, and staff. Any substantial change usually triggers changes in the way work is being done, requiring evolved organizational structures and a new mindset to actually make it work. Transforming organizational structures is by nature a co-creative endeavor, requiring collaboration and support from people involved in the activities and impacted by a change. These projects have to affect the habits and beliefs people are used to in order to change the way things are getting done. Their manifestation in business practice is driven by a mix of formally defined structures such as organizational hierarchies and job definitions, and of informal social norms, habits, and assumptions leading to certain attitudes and behaviors.

Addressing these issues requires us to take into account the organizational reality around the processes and products that come out of a strategic design initiative. The Enterprise Design framework therefore makes the organization aspect an individual conceptual topic independent of any accompanying project or change management. It assumes organization is an aspect that is as worthy of a design initiative as the other conceptual aspects in this chapter, and meant to be modeled and designed to support the objectives of the project.

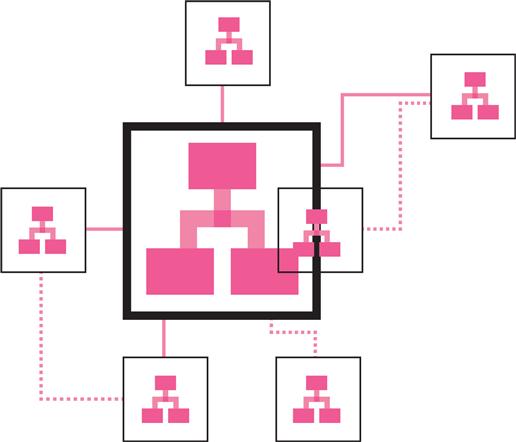

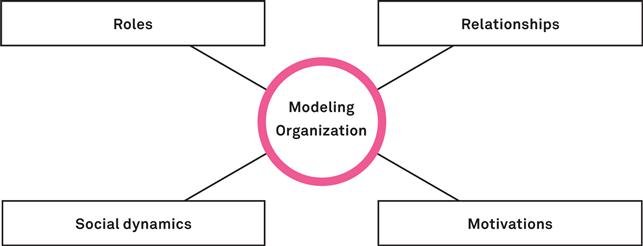

Modeling organization

Design practice never happens in a vacuum, but is always embedded in an existing or emerging organization, impacting both structure and culture. Classic approaches usually start at the periphery of organizational structures and cultures, focusing on the products, services, or communications to the customer. In reality, their success is highly dependent on the adaptation of human behaviors and attitudes in order to really deliver on their promises. Without aligning results to the people intended to work with them, the benefits envisioned from new customer interactions, tools, and technologies, or redefined operations cannot be realized.

While organizations of all sizes and types need to adapt and reinvent themselves in ever shorter cycles, the traditional tools and methods for understanding them are still based on comparatively static metaphors, that neglect the complexity and dynamics that influences their development. They attempt to shape organizations as though they were analogous to buildings, machines, or living organisms, but fail to acknowledge the fact that they are made of people — determined not by fixed parts or processes, but by the mindsets of individuals and the dynamics of groups. So in contrast to those other man-made systems, designing organizations involves dealing with social systems or communities, resistance to change, and politics.