Across the Dashboard

Abstract

Global companies can easily fall prey to diffuse goals or corporate politics when it comes to their globalization practices. Everybody wants to sell a relevant product to their target markets, but often there are geopolitical and culture-related issues to think about. Should a product be sold in both Hebrew and Arabic? Should a map note Taiwan as part of the Chinese territorial expanse? And how to execute the necessary research to avoid a commercial failure and public opinion backlash when insensitive decisions are made? A concerted and thought-out strategy is necessary in order to place the proper strategic emphasis on the globalization and international awareness of a project or product line.

Keywords

Globalization; markets; product; corporate; software development; culture; research

3.1 Establishing a Global Product Vision

No matter where I go in the world, although I can’t speak any foreign language, I don’t feel out of place. I think of the earth as my home.

Akira Kurosawa

It is essential to ensure that content released within your products is always consistently “locally appropriate, and globally relevant.” The right move is to anticipate reception and not to defraud expectation. There is a tendency for ethnocentrism in software design that can easily overshadow the entire development and release cycle. There are markets, however, that are outside of the proverbial box. Clients do expect the right language and experience for their local needs, and it is necessary to harvest these from the actual users.

A software development or service design cycle is an organic process, and the right pieces must fall into place. The same goes for the flexibility and openness to communication that such a department must hold even in the strictest strategic sense.

Pursuing a fully global product vision combines not just the commercial objectives, but also to understand what the reality of people using the product is. This involves user research, globalization processes, and an international strategy. These play a key role in corporate strategy and project planning for what are usually relatively small teams. The vertical or “meta” teams proactively endeavor to enforce cultural awareness across all areas of the company, which in complex multinational decentralized structures, can be a daunting effort.

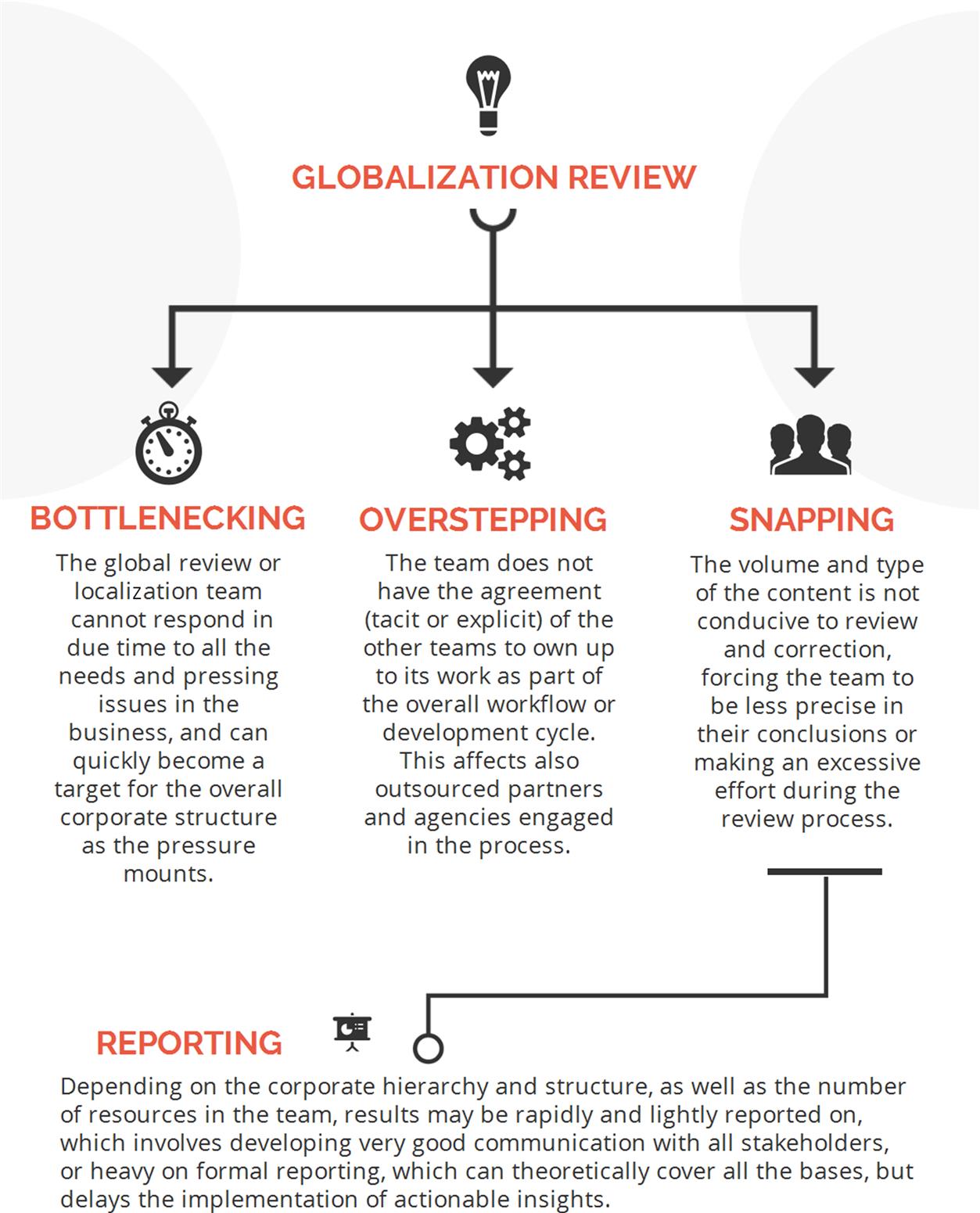

A process shift such as this requires distributed ownership and corporate responsibility. It is not possible for any one isolated team to review effectively the work put into a product by the entire corporation, regardless of its size, without risking three factors (Fig. 3.1.1):

The principal step toward a healthy outward-looking attitude toward international customer bases is to train people to spot issues as soon as possible. In this sense, by the very nature of user experience (UX) work, this type of work encourages a cross-pollination of multidisciplinary skills, often calling teams into a collaboration model.

The communication facilitated by multifunctional people in the organization is a key to the “natural liaison” concept introduced by Adam Polansky. Individuals sustain and represent functional areas that are overlaid and complement each other, and fulfill a vital role in clustering disparate departments and key points of product development consistently. Paul Sherman (2011) suggests that these individuals carry the weight of initiative and evangelization in the corporation, and certainly UX, a field where multifunctionality and the ability to have expertise from various sources converge, lends itself to this active role within the corporate structure. UX incorporates ethnography, design, research, psychology, and human factors: it has become the proverbial kitchen sink for product development and corporate alignment, and the natural response to a primarily consumer-driven culture. However, teams often struggle with the inability to promote UX in the corporation beyond the scope of usability or even esthetics (Fig. 3.1.2).

The misunderstanding over the role of UX derives largely from the inability of companies to understand its customers, a field that UX should be accountable for. Trust is not a one-way street, nor is it a self-sustaining organism that can be left to its own devices after initial implementation. Trust is about making the pieces fit, and, like a jigsaw puzzle, finding out the side where the ridges are slotting in more easily. This process always starts with making the fundamental question: how can a business know its customer base reliably and develop a continuous and consistent perspective of the evolving customer needs?

Research is the obvious answer, both quantitative and qualitative. Interviews and surveys are the most often used methods of understanding users, but they paint a limited picture due to lack of context and practice. Any method relying on people describing what they think or do is limited to a fault, as both can easily contradict each other. People often do things out of habit and might have a limited perception of what motivates their behavior.

The best way to overcome these hurdles is to understand that the road to experience is paved with different pictures and stories and rely on observational information coupled with actual quantitative information. By gaining an insight into the user behavior on your website, the actual streams and the channels that play into your user’s habits, you will find the basis for a sound international strategy.

3.2 Kickstarting Corporate Change

Every man takes the limits of his own field of vision for the limits of the world.

Arthur Schopenhauer

Since the mid-2000s, UX has quickly risen to become a defining field in user-centered design and research. However, its prominence is indebted to the popularity of computers starting in the 1990s. The emphasis on usability as a differentiation factor was directly related to the success of early versions of PC and Mac in the 1990s, allowing for companies to be perceived as different not only by core product proposition and price but also by a renewed emphasis on customer satisfaction and ease of use. This allowed behemoths like Amazon and Apple to become market leaders.

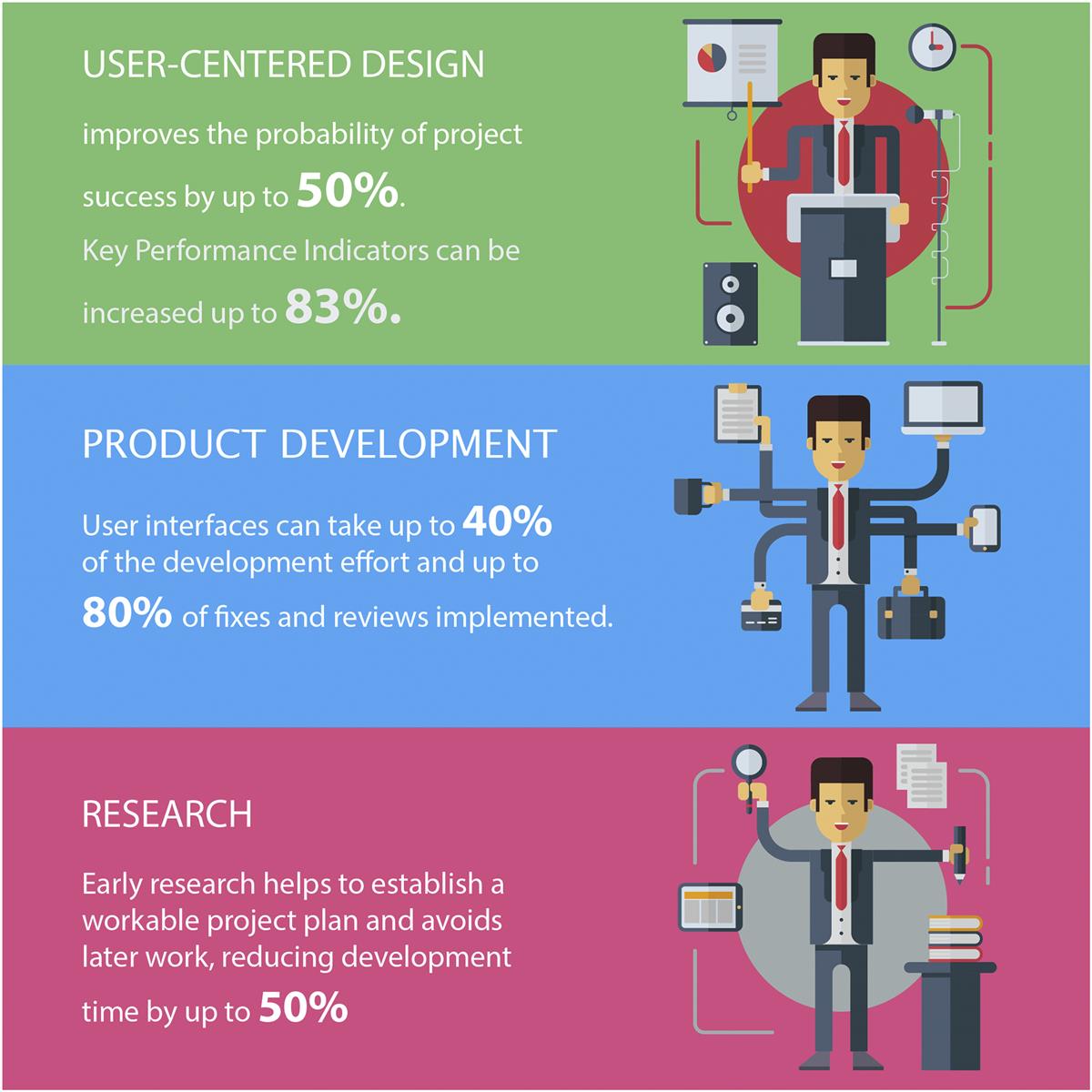

However, many companies are still caught in self-centered paradigms that do nothing to reduce lack of efficiency during development and design. Research has proved systematically (Jones and Sasser, 1995, Prokesch, 1995) that sales increase proportionally to the investment in usability and design research. Investing just 10% of a project’s budget in usability can yield up to 100% on sales and conversion rates (Nielsen, 2003).

The value of user-centered methods in improving the quality of computer systems is paramount to all stages of project development (Fig. 3.2.1):

The general issues faced by a user-centered project are only compounded when combined with the need to develop for international markets. The development of a global vision for a corporate strategy is a perilous zone of discussion that deals with several concurrent aspects. Lots of companies have good solid ideas about products that can appeal to international markets but lack the experience or the adaptability to make a specific product work in markets beyond their normal breadth of experience. This is where the involvement of all the stakeholders is crucial to face the challenges of becoming user-focused, especially on an international level.

Business structures and workflows should support the overall objectives of developing actual products for real people in the real world. When companies have to coordinate globalization projects over different regions, and multiple offices, there are inevitably differences in operation methodology and vision. No company is “born global,” regardless of how acceptable and popular their products may appear to be. The need to have a sustainable globalization operation program is a key component of the wider company strategy. As IBM stated in a 1999 report on “Cost Justifying Ease of Use”: “It makes business effective. It makes business efficient. It makes business sense.”

Regardless of whether the globalization team has responsibilities and stakeholders in the UX, content strategy, or localization sides of the business, the core globalization team should follow these few steps to ensure their role in the process:

![]() be well-connected within the enterprise,

be well-connected within the enterprise,

![]() actively collaborate with in-house copywriters and transcreators,

actively collaborate with in-house copywriters and transcreators,

![]() evangelize for awareness of globalization strategy within the company,

evangelize for awareness of globalization strategy within the company,

It is important to realize the role that UX plays in corporate strategy. Many high-end executives make the mistake of considering UX as “whatever makes the site pretty” or a magical step into user’s minds regardless of methodology and execution. These perceptions can only be countered with consistent and persistent evangelization and education. It is a constant source of frustration for many designers to have to educate an occasionally immature workflow, but it is also an opportunity to apply your empathic skills to improve an organization from the inside.

Companies have a nasty habit of looking sideways rather than ahead. Competitive analysis is often used to generate feature requirements and investment in the roadmap often tags along with other companies in the same segment. This is due to one of the core problems in the market: reactivity. Reactivity is essential to stay afloat in very competitive markets, but it can also stifle internal innovation as original ideas get squashed in favor of following in already trodden paths.

In this context, UX is often framed as a way to optimize conversion and retention. The best way to justify investment in the area and to build a strong business case is to directly correlate it to growth.

3.2.1 Lessons from the Field: Globalization According to Sony

As a company, Sony has forged a long and influential path. Its distinctive minimalist industrial design was an anomaly in the marketplace for decades, but the company used its design philosophy to promote a unique image of high-end simplicity. This proved to have a significant impact on entrepreneurs like Steve Jobs, who studied Sony’s marketing materials attentively when Apple shared its first official headquarters with one of Sony’s US sales offices in the early 1980s.

Times have changed, but Sony’s strategy has remained relatively consistent. Sony’s offices are now distributed worldwide, from Tokyo (also the headquarters of the company) to San Francisco (where most of the company’s UX is designed). With the need to decentralize resources, the company faces a challenge that other major players are also subjected to: the processes and methods for ongoing projects and programs worldwide are not developed in tandem.

In terms of content, for legacy reasons, products are actually developed with 2 source languages for a total of 33 target languages. The company operates in over 70 countries, which implies a massive logistical effort, which is the culmination of a transnational strategy that took over 20 years to implement. In the 1980s, Japan was the first country to successfully open production facilities in the United States and was rewarded with a massive success based on the customer perception of its products as distinctive high-end designer items.

This success was largely due to the time that Sony spent studying markets before setting up operations there. It learned the local reality before investing more heavily in the market, and this research helped it to become one of the most pervasive brands on the planet.

Like most companies, Sony operates by setting up sales operations on a new territory first and only later implementing local operations, which may include development and design teams. This helps to distinguish approaches for the European, Latin American, Asia-Pacific, and Asia markets. Apart from the different market adjustments, products line are introduced or maintained depending on their market performance and their relevance to local audiences. This mandates a careful design strategy, which caters to local requirements yet still preserves the company’s distinctive minimalist style. For instance, the earliest presence of Sony in Germany was focused on establishing a perception of quality, and with this objective, the company focused on understanding the market before setting off on any commercial concerns.

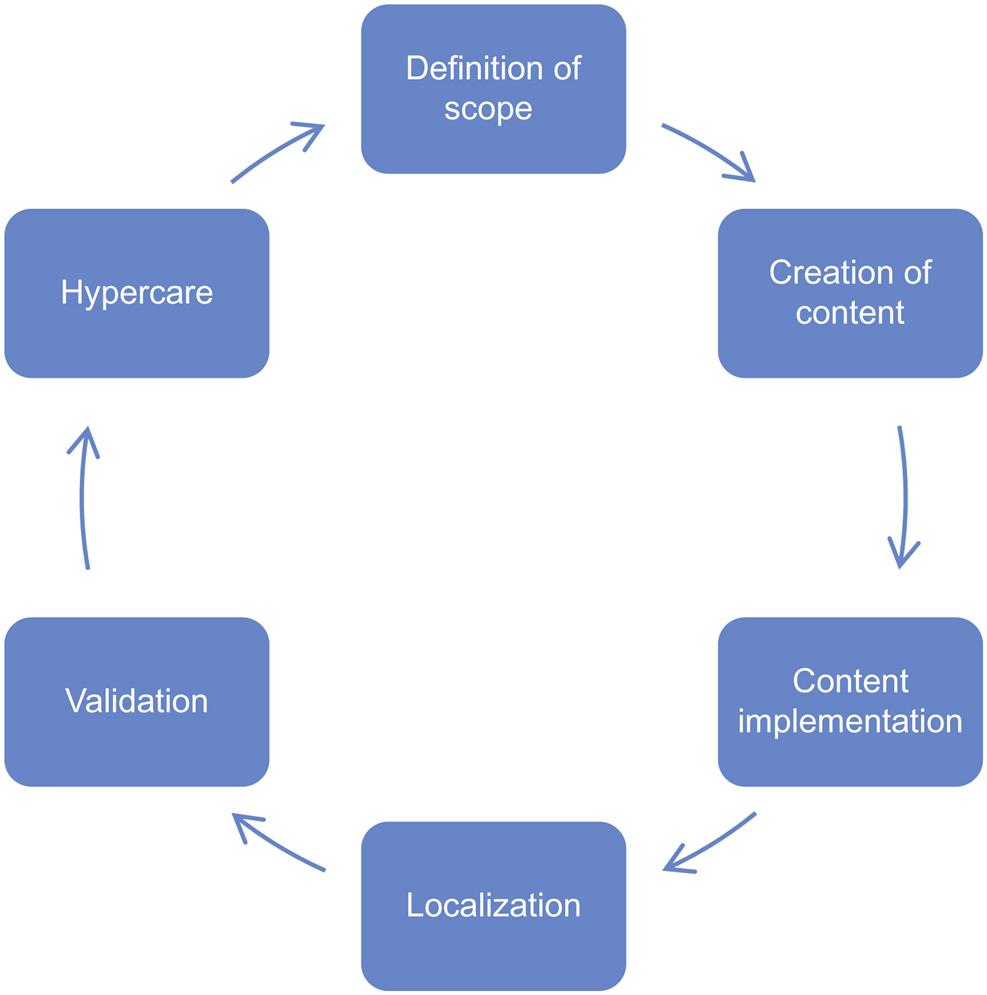

Sony also coordinates global launches across different territories over a period of up to 24 months (longer in some cases) that extends through the following phases for content-sensitive projects (Fig. 3.2.2):

These projects are released in waves, with each wave focused on a different region. Content localization relies on an internal translation system, which is closely integrated with internal CMS and translation partners. Content operations are performed in bulk, and the translation system includes basic automatic QA processing on character length, terminology inconsistencies, fragmented sentences, and automated capitalization issue. This integration allowed Sony to reduce their work volume by up to 50%.

3.3 Agile Globalization

Grand principles that generate no action are mere vapour. Conversely, specific practices in the absence of guiding principles are often inappropriately used.

Jim Highsmith

Agile has quickly become one of the main project methodologies in the software industry, taking both companies and agencies by storm.

Agile is a design and development process framework of a “lean” nature. It is often associated with a certain philosophy underlying a set of guidelines which emphasize close integration and communication, as well as a goal-oriented collaboration among corporate, design, and engineering teams. Agile focuses on goals and actual value, rather than processes, and is inherently a responsive methodology. The document that started it all, the Agile Manifesto, was signed at the Snowbird ski resort in Utah in February 2001 by a group of disgruntled developers and engineers, disappointed with the lack of focus of lightweight methodologies. It is still used as a watershed reference across the industry, unchanged for over 15 years (available at agilemanifesto.org): individuals and interactions over processes and tools; working software over comprehensive documentation; customer collaboration over contract negotiation; responding to change over following a plan. This is also a methodology that is inherently reactive and devoted to rapid development. By reducing the load associated with long requirements documentation typical of Waterfall systems, it is possible to achieve quick and tangible results. This suits UX developments, as work activities can be parallel rather than serial, but the quick and flexible approach can also support quick development and reaction to changing priorities or the logic of the market. Another aspect of Agile that favors UX research and design is its iterative nature. By focusing on the true customer value, rather than internal processes, Agile UX allows for a quick approach to research. This includes the ability to run qualitative studies, like user interviews and testing, or quantitative, like surveys, heuristic analysis, and competitive analysis, in order to make quick decisions on feature prioritization and development focus, and get fast feedback on implementations over the results of the earlier iterations.

Localization is frequently linked to the end-of-chain stage, interspersing time constraints with role diffuseness, leading to severe quality compromises in most cases. However, localization is an essential step in designing and planning for a consistent UX in international markets.

In this context, internationalization and localization becomes an essential component of the overall globalization process. Corporate-wide linguistic strategy is a must in this case and localization departments can work in tandem with the UX teams to help drive this effort by supplying much-needed geopolitical assessments and assessing the effort behind localizing a given product in a given language (Fig. 3.3.1).

This counters the frequent perception of localization as a more or less sophisticated translation management process applied to software development. Not only is this untrue, it is dangerous in Agile environments. In an Agile environment demanding constant responsiveness, responsiveness, and the ability to adapt to changing requirements in a constantly shifting context, the project development process is never really over.

This implies the necessity to change requirements at late stages, which can represent a major hurdle for teams. However, if research and design work together in knowing the market and the user requirements, a key cog of a chain that relies on communication and stable interchange of information is then set into motion. While monolithic development and requirement lack of specificity often compromise results in traditional development structures, Agile’s focus on productivity and decomposable work items enables a richer and more quality-oriented development process.

From a design point of view, localization (or, in cases where both are owned by the same team, globalization) must be one of the stakeholders in the User Story if it is determined that it affects any kind of text resources in the application, either directly (i.e., text changes) or indirectly (i.e., impact on UI design or graphic arrangement). From a maintenance point of view, this relies on preplanning and resource assignment from an early stage. Localization is the primary link between a software application and its international marketability and should be taken into account as early as possible in the software development process.

3.3.1 Team Dynamics: Rockstars and Technical Gaps

However, unlike the view perpetrated by many Agile evangelists and coaches, Agile is not a godsend for development and UX. It is the source of many a frustrating and tense moment in some teams, and depends not the internal corporate structure: the quick pace is often deemed unsuitable for finding the best creative solutions. Although Agile games and methods are used, there is no actual mindset in the team, prompted by distrust and resistance to change; there is a general sense that Agile implementation consists of a “cargo cult” where the benefits will come eventually with sufficient ritual devotion; a typical criticism is that Agile is better suited to smaller teams where the dynamic is higher and easier to manage than with larger corporations. Agile design is not easy to track and even harder to account for in a standardized manner. Agile does not accommodate for the individual and many Lean experts actively advocate against having “rockstar” elements in the team. Agile resistance is also about the barriers that workflow adaptation and management migration must face. On this last point, there are numerous tensions to having cross-functional teams, especially when human nature determines that the individual reward (either material or in recognition) is at the base of most of our behaviors. A team is a psychological mix of combined influences and behaviors, and maintaining a dynamic balance is a hard task for any team leader or manager. Developers provide Luiz Fernando Capretz, in a 2003 study, argued that the most common personality type amongst developers was the so-called ISTJ (introverted, sensing, thinking, judgment), while other studies found that there are correlations between product quality and the dominant personality of team members, with extroversion having a positive effect (Acuña, Gómez, & Juristo, 2009). Designers and developers often have a contentious relationships, as they can sit in different countries, and only really communicate systematically through ceremonies like the daily stand-up. This results in a difficulty of ownership and accountability, as the conflict between both sets may contribute to slow down progress and reduce the odds for productive conversation in the midst of the team. Designers (particularly of a visual nature) may not feel empowered by the development workflow, and if there is a systematic approach to having their tickets or tasks deprioritized by developers so technical or back-end issues are addressed, there may be a growing feeling amongst designers that there is a technical “gap,” whilst developers may well feel that designers throw wireframes “over the wall” to them with little motivation to back it up. In these circumstances, there is no replacement for personal presence and face-to-face communication, particularly when discussing the technical intricacies of a specific design. Having even one full-stack member in the design team will fuel productivity and awareness, serving as an anchor to edge the team closer to understanding the demands of the design and communicating with developers in a more productive manner. Sponsoring co-location (even if temporarily) and visits among the teams can definitely improve the prevalent relationships. Having lean analytics to track implementation success, as well as a shared pattern library and style guide for all project members can also help.

3.3.2 Agile Roles

Actors and stakeholders in an Agile project come together in a unique way that is a departure from traditional workflows. For companies in transition from waterfall to Agile, User Stories can follow an acceptance criteria and function like small, manageable requirements. Any User Story implemented in a product has several components that demand different expertise from a multispecialized team, which can be either contained in different departments or, optimally, working exclusively together on given parts of the product. In this setting, global strategy is a concern from the get-go thanks to constant involvement with the core design and development teams, as well as the product stakeholders. Project management duties are distributed and the Product Owner’s vision is instrumental in the whole process.

The naming of roles often varies between different Agile methodologies, but some commonalities can be identified.

Customer

It can be a combination of the Product Owner and the end-customer. They specify the product requirements, regardless of the actual final plan.

Product Owner

Fulfills a similar role to the classical perception of the Product Manager in waterfall methodologies:

![]() creating and collecting the general requirements of the project,

creating and collecting the general requirements of the project,

![]() establishing clear objectives for ROI,

establishing clear objectives for ROI,

![]() having responsibility over the Product Backlog prioritization and management.

having responsibility over the Product Backlog prioritization and management.

Scrum Master

The role drives and supports the work developed by the team, helping the team to overcome potential obstacles to completing the project stages. The role is of the main facilitator and implementing the process for the whole team.

An iteration typically lasts 1–4 weeks and has four distinct phases:

Planning

The preparation of the project involves prioritizing and handling items in the Product Backlog that will be implemented during the iteration, in case one is used. For noniterative approaches like Kanban, the team gets together regularly to review and plan the next batch of items to be implemented. Normally, if the iterative model is used, it should have a clear theme or goal.

This is where the UX teams can be most influential. Insights from research and preparation for both visual and experience design set the stage for development for implementation. This is also where user testing can be most useful, working on hypothesis and implementation ideas before.

Development

During the Development phase, there is also a daily status meeting known as the daily stand-up. In this meeting, each team member states what they did the previous day, what they are going to do today, and identifies any existing or foreseeable roadblocks.

Review

When the iteration nears completion, a review meeting is held with all stakeholders to demonstrate the new software and receive feedback on it and the functionality that has been developed.

Retrospective

The last phase, or Retrospective, is a postmortem for the team to discuss how the process could be improved.

Localization and design are not separate worlds. Text is an essential part of a complete multimedia system that includes image and text. Visually and linguistically, text plays a major role in the user’s perception of a product. The most refined and sophisticated UX can be wrecked by careless localization and haunted by issues and bugs. Fonts are lost, carefully complimentary labels suddenly appear juxtaposed, HTML is improperly adapted to target locales: all are little product nightmares that can only be countered by a combined approach that makes UX and localization part of the same combination.

Therefore, internationalization is key to a consistent UX in a multilingual product. Internationalization defines the set of processes and techniques that are implicated in making a product capable of adaptation to different cultures. This is where UX implementation is at its trickiest. No sound internationalization-friendly design can be adequately implemented without an accurate study of localization prioritization. You must define which languages and cultures you want to localize into and include both immediate priorities and future plans. This will enable you to optimize layouts for culturally sensitive graphics and indications or—optimally—to change requirements in the light of new market strategies.

3.4 The Role of Global Awareness

The Chinese use two brush strokes to write the word ‘crisis.’ One brush stroke stands for danger; the other for opportunity. In a crisis, be aware of the danger—but recognize the opportunity.

John F. Kennedy

Global companies can easily fall prey to diffuse goals or corporate politics when it comes to their globalization practices. Everybody wants to sell a relevant product to their target markets, but often there are geopolitical and culture-related issues to think about.

Should there be language parity within a region? How do maps account for geographic territorial disputes? And how to execute the necessary research to avoid a commercial failure and public opinion backlash when insensitive decisions are made?

Global awareness is related to the whole enterprise and affects every single process in display. With that in mind, Paige Williams, Director of Global Readiness at Microsoft, classifies the work of her team as helping to ensure that content is “locally appropriate, while globally relevant.” According to her, the right move is to anticipate reception and to be considerate of user expectation. “Understanding cultural and language needs is complex when you consider that people using technology are mobile, bringing their culture and language, or languages, with them wherever they go; be it to the office, in the home, or as they travel to various destinations.”

A software development or service design cycle is an organic process, and the right pieces must fall into place. The same goes for the reliability that such a department must hold even in the strictest strategic sense.

We spend time researching and remaining current on geo, cultural and language topics, to assess not only the correctness of various scenarios, but also to understand where there are complexities or sensitivities to factor in. When things are “right” with a content experience, it’s seamless for users. If things are not quite right, or in fact would be considered “wrong”, it’s more likely to face risk in the marketplace. We would rather vet these scenarios as a part of our overall process of quality, rather than learn about a concern too late in the cycle.

The concept of Global Readiness as a combination of sociopolitical research, internationalization QA, and cultural markers review ensures a key role in corporate strategy and project planning for a relatively small team. The vertical department proactively endeavors to enforce cultural awareness across all areas of the company, which in a complex environment offered by a multinational giant, can be a daunting effort (Fig. 3.4.1).

However, according to Williams, “we cannot possibly cover the entire company from one team; instead, we train people to spot issues as soon as possible and from where they sit in the organization.” In this sense, by the very nature of UX work, this type of work encourages a cross-pollination of multidisciplinary skills, often bringing teams together under the initiative of a corporate strategy toward global readiness.

According to Paige Williams, imagery analysis is also a source of global inspection. The origins of the Global Readiness team began with analyzing the assets shipped with each product, in the beginning starting with products like Encarta, where geoculturally sensitive materials were a likely source of market risk in certain territories. Digital or analog, an encyclopedia always has aspirations of universality, and the correctness of the content is essential to its success.

Cartography was also an important geopolitical concern, where maps often had to accurately portray the contemporary status of international politics in a nonconflictive way. An international company cannot afford to alienate major players, both political and economical, in the international market.

A team involved in cultural assessment has by principle to be multidisciplinary, and to be aware of the actual expectations of the target markets. They have to know what is “locally appropriate, and globally relevant,” and the weight of this process in corporate strategy and project planning is second to none.

The origin of the Microsoft Global Readiness team lies on imagery review with the early product Encarta software, a popular staple of desktop OEM systems in the 1990s. The software was originally provided in CD-ROM and, as a read-only media, it did not benefit from hot fixes and live content updates as most web products do today. The shipped product was expected to last at least 9 months on the shelves, depending on reception and audience demand, and getting the content right before the release was essential to its perceived quality. The maps, borders, names of cities, and other geopolitical markers were a critical aspect of quality assurance in packaged software.

Now, given the dynamism of global politics, local expectations are as critical as ever, especially with the migration to a primarily online experience. This has implications on the release process, particularly with a rigorous compliance process.

It is impossible to avoid issues with released software unless an actual corporate policy is in place that allows cultural review to assume a primary role in the product’s development and final acceptance. Releases are never validated unless checked and approved by content reviewers. According to Williams, the product as a whole has to reflect “what it means to be outside of a (packaged) box, especially when customers do expect the right regardless of where they are originally from, where they are living now, and which language, or languages, they may speak.”

3.5 Iterative Refining

I wanted a perfect ending. Now I’ve learned, the hard way, that some poems don’t rhyme, and some stories don’t have a clear beginning, middle, and end.

Gilda Radner

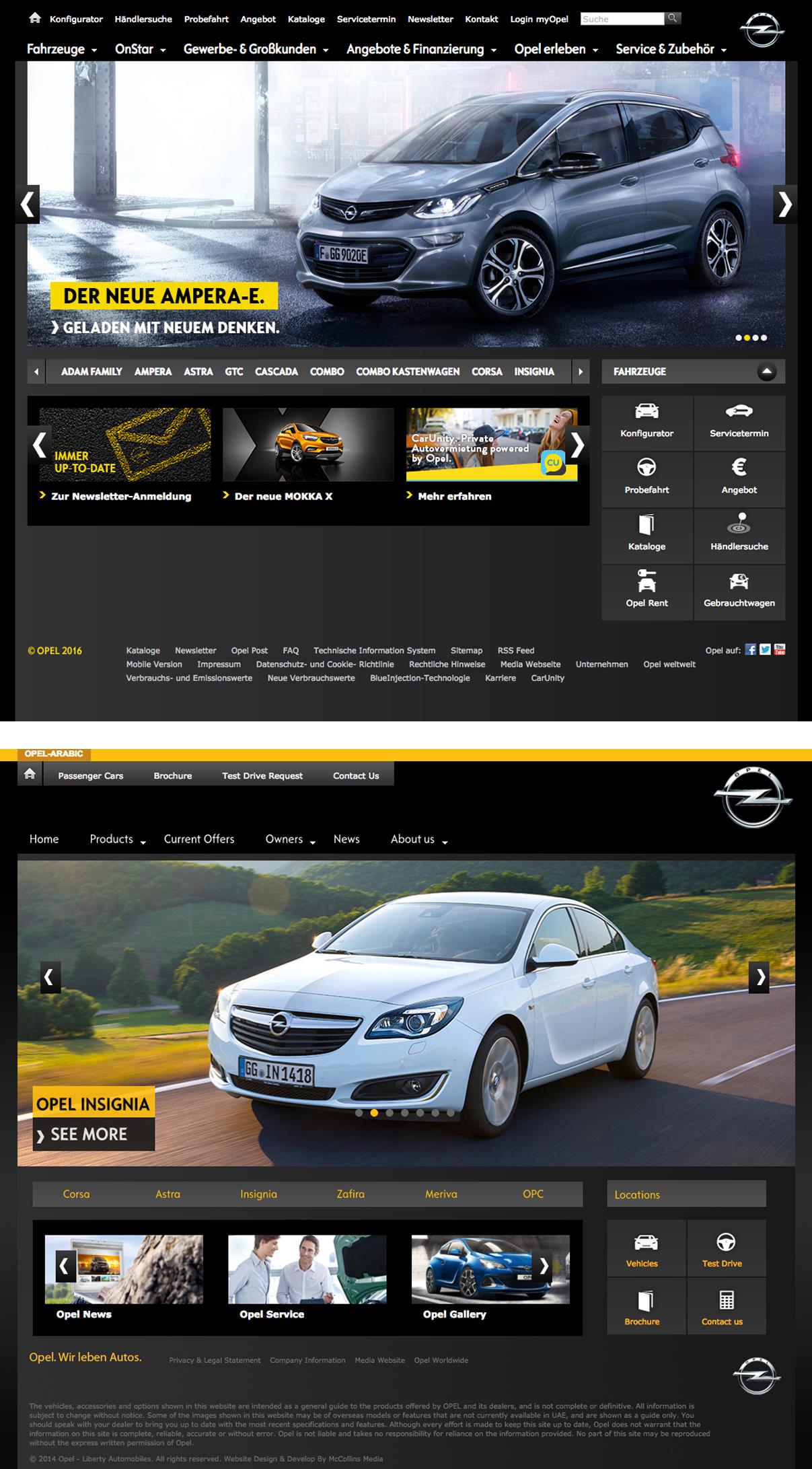

Local websites of global consumer brands often use a global template that is specialized locally. This allows the brands to keep the layout and navigation consistent by usually relying on the same template. This consistency comes at the cost of specialization, but can be cost-effective if the market is still developing or if your website is not the main channel to enter the company’s value proposition. This is the case with the Opel website, which uses a standardized layout for nearly every market, except the ones it goes by a different naming, like Vauxhall in the United Kingdom and Buick in the United States. Like other car brands, the website can be low-context, focusing on technical data exposition and providing an authoritative reference that relies little on the previous knowledge of the product (Fig. 3.5.1A–C).

These brands exemplify that the best approach is often to have a modular approach to both widgets and CSS elements, with front-end and back-end modules available for multiple configuration for different markets.

For corporate webpages, even with transactional areas, this type of globalization process usually relies on a “master design” with a “post-release” international adaptation, and can be treated as a separate project for each territory. However, working on a “simship” (simultaneous shipment) basis for apps and software products requires an altogether more sophisticated integration between teams.

This implies the need to break with the traditional model of a waterfall-based model where UX teams hand over designs to developers for implementation with minimal communication after that hand-off. This leads to a separation of duties that is not beneficial for the workflow as a whole. Designers and managers can easily lose perspective by being unaware of the necessary adjustments and adaptations that their designs may require in development. The problem is compounded in responsive design projects, especially those who span a multitude of platforms. The possibilities that a single design may suit dozens of browsers and mobile combinations, as well as a variety of use cases, are minimal.

The technical drawbacks and necessary depth of testing involved in catering for all these disparate markets implies that the end result will be leveled according to the basest result possible. The design is hindered by the conditions in which it is displayed or by design assumptions which may not hold true. For example, although a metasearch engine developer may assume its top-usability intuitive page runs at a satisfactory speed in all devices, the search options that are key to the user experience may not be visible above the fold in smaller devices like those used in the South American or African markets.

Adapting to multiple devices is akin to a Damocles sword, constantly dangling over a layout and threatening to completely disrupt the experience. Modern UX design focuses largely on a two-dimensional approach to design, similar to a typographical workflow, where sizes and layouts are adjusted continuously, but in this case, instead of a single page size, these designs will hang precariously on thousands of prescriptive and highly variable canvases.

Similarly, features do not come out of a development sprint deliciously garnished and ready to consume, especially in the earlier stages of the development. In fact, often the result is downright disgusting: half-baked and barely functional lumps of code are thrust into testing, but the scope remains the same and the expectations do not change. Add to that the pressure of time in tightly wound environments and the whole thing threatens to unravel.

Too many teams adopt a “stand-by and pray” attitude, where the final release in the cycle is the first user release. However, in order to face the situation constructively, the best approach is to decompose the testing in parts and focus on the parts of the flow of the user journey and to test only the changes made by development.

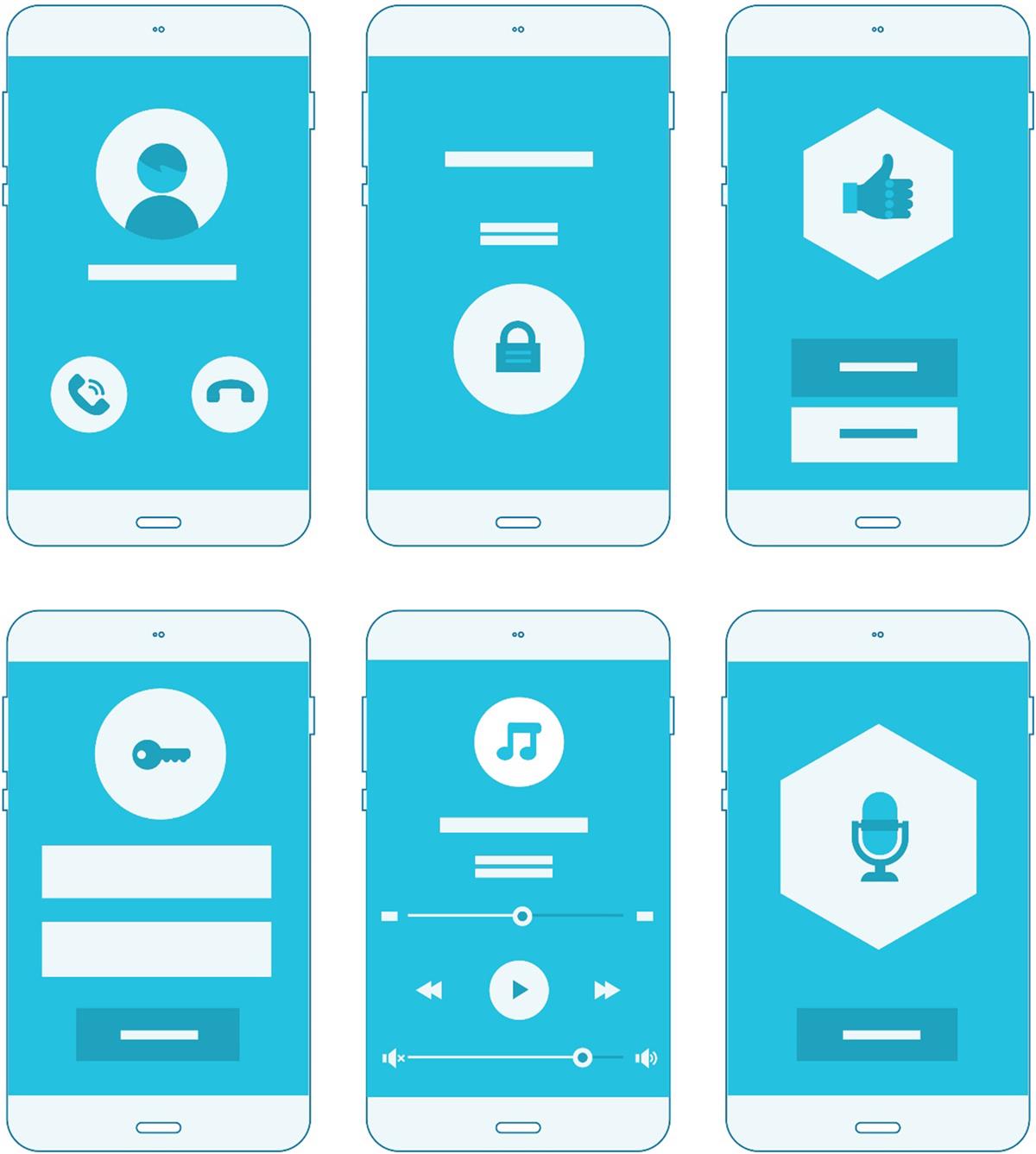

Traditional rapid prototyping can assist in developing a quick iteration of the project, but it will eventually pigeonhole the process, as it focuses on optimizing a design, rather than uncovering fundamental issues with the product or questioning the validity of the feature designed. A good example is app security and password logic, which have grown into one of the more complex full-stack conundrums. Front-end logic limits password rules, whereas the encryption system takes care of the storage and protection of the passcodes. Many form designs have convoluted rules for password checking, yet these seldom amount to an actual increase in app security. According to a 2015 TeleSign report, 73% of online accounts share duplicated passwords, and 54% of people will use less than 5 passwords throughout their entire digital life. The beauty of the design (regardless of how many rules are used to validate passwords) is hindered by the user habits, reducing the value of the effort put into security.

Analyze what effectively works in the context of your team. Frontloading design and prototyping work may be seen as ineffective, and a hybrid approach may benefit the team’s relationship with development and managers. Design can be iterated initially, or validate concepts continuously as the project progresses. The end goal should always to validate the best possible UX, rather than to increase efficiency at the expense of usability or optimize small parts as opposed to developing sustainable scalable workflows.

Rapid prototyping can also benefit from a decentralized corporate structure, where facilities working with an interval of several hours can work on the same front-end design or module on the same time frame. In ideal cases, this can lead to a round-the-clock 24-hour cycle arrangement that can benefit the project as a whole. There is also the risk, however, of misunderstandings and delays due to poor coordination or misunderstandings over knowledge and content ownership.

When possible, use low-fidelity wireframes and do not invest time in high-fi mockups until the needs of both core and secondary audiences are defined and agreed by all the stakeholders’ requirements (Fig. 3.5.2).

3.5.1 Wireframes

Wireframes consist of simplified representation of designs, which can be made into prototypes. These prototypes can be either analog or digital, either for demonstrational or interactive purposes.

Often times, wireframes are represented with lines and text, on paper (hand drawn) or electronic. They should already highlight content and structural elements that are represented with lines and text, as well as a hierarchy and priority of elements.

They are not focused on visual design, and in case visual choices are already making their way into the wireframes, this can sometimes work against acceptance. It depends on the team and stakeholder culture. While early wireframes can set up wrong expectations, it is sometimes useful to illustrate your design solutions with some spit and shine in order to translate a specific product vision properly to the unsuspecting teams. Just be careful on how this may condition very early decisions.

Wireframes are generally devoid of color and styles and serve as a “stick draft” which can be used to test with users and perform heuristic evaluations, as well as to allow the team to visualize and discuss interaction strategies. It is a schematic and a blueprint, and essentially meant to guide feasibility and early testing.

The fidelity may change, as well as the content quality, but a wireframe should translate more than that: it must be in sync with the goals of the project and audience. Therefore, questioning any early details should be a progressive and mindful process, with the priority being the true adherence of the design to the project goals and audience.

Many alternatives will inevitably be produced in the process, so it is important to stay focused on the right issues and try design alternatives.

Any user-centered workflow design will rely on the feedback and analysis of the customers and target users, with this data informing the design process directly. This will maximize the benefits and the adequacy of the redesigned platform to suit the wishes and requirements of the customer, allowing for a smoother and more engaging experience.

3.5.1.1 Lessons From the field

A few ways of designing effectively for different devices are as follows:

![]() Focus on product: for designers, it is important to keep in mind that the intent of design is primarily to deliver a core user experience, which consists of the base level group of features that the product is supposed to deliver. Do not worry about redundant or secondary features, and prioritize those that are at the center of the product.

Focus on product: for designers, it is important to keep in mind that the intent of design is primarily to deliver a core user experience, which consists of the base level group of features that the product is supposed to deliver. Do not worry about redundant or secondary features, and prioritize those that are at the center of the product.

![]() Divide devices by groups: analyze the markets where the product will be sold and develop a shortlist of the most popular phones for each territory you will target with your designs. More information on how to accomplish this strategy is available elsewhere on this book.

Divide devices by groups: analyze the markets where the product will be sold and develop a shortlist of the most popular phones for each territory you will target with your designs. More information on how to accomplish this strategy is available elsewhere on this book.

![]() Be input-agnostic: privilege a “fat finger” approach when designing. Think of the least practical and optimal pathways through a design, and optimize from those. Users will break things, and every flaw can be maximized.

Be input-agnostic: privilege a “fat finger” approach when designing. Think of the least practical and optimal pathways through a design, and optimize from those. Users will break things, and every flaw can be maximized.

3.6 International Research

We have met the enemy and he is us.

Walt Kelly, Pogo cartoon strip

User research is a relatively recent discipline of study and analysis. It is the combined product of techniques used in anthropology, ethnographic studies, market research, and industrial engineering. It is partially the result of a long-standing trend to approximate actual usage observation with intended design, and has been heralded as the best way to get in touch with the audience using an objective methodology and a consistent framework. In most of its assertions, it involves collecting information directly from the users (Lafrenière, 2008) rather than insulating product development from its audience or lacing user feedback with procedural red tape and biased observations.

The field involves a continuous appreciation of the evolution of both usage and technology. User habits change quickly in a day when the average urban dweller has an average of 3.64 devices (GlobalWebIndex, 2016) and not all adopt new products or technologies at the same rate. People differ in social standing, economic power, preferences, emotional responses, and a multitude of other factors that can be attributed to both social and psychological causes.

Rather than to accommodate for individual variation, user research is primarily centered around tendencies and bias in group results. One interview is not enough to make a defensible report, and a sizable and representative sample is needed in order to produce any kind of meaningful results. Sometimes, researchers adopt an holistic approach, “eyeballing” a result or seemingly steering a study toward a certain hypothesis that appears obvious or a common tendency based on past projects. This is a common problem of reliability and validity in ethnographic research (LeCompte & Goetz, 1982), but it can be minimized by taking special care with all stages of the research process:

For example, aspects like the researcher’s gender and social status can play a decisive role in the data collection stage. Depending on the dominant culture and surrounding environment, a female study participant may provide inaccurate or merely different feedback to a male moderator during a test session. A young student might feel constrained by a significantly older interviewer, or too comfortable and seeking social approval with an interviewer who is too young.

Rule of thumb: For any study, it is strongly recommended to have more than one researcher. The average study should involve at least two researchers, if possible of different backgrounds. All the researchers should be exposed to a varied subset of the tested audience (e.g., hold interviews with the same number of men and women and with varied backgrounds) as that will guarantee a better analysis of the multivariate research. Mix and match the entire study as much as possible, rather than assigning “specialized” parts of the study to the same researchers.

To get more meaningful information from participants, the study should have a facilitator who is very familiar with the demographic and background of the participants.

The use of an interpreter during the testing can assure the end-client of the quality of the interview and provide the “gist” of the testing as it occurs. This is particularly relevant during sessions broadcasted directly to stakeholders, as it allows them to take their own notes, discuss observations, and start posting observations on the wall. However, it also has three main disadvantages:

1) It takes more time in the interview session which could otherwise be used for the actual testing.

2) It slows down the responsiveness rate when users take different paths during testing, and may compromise observations.

3) It may create a more difficult atmosphere for the user to communicate openly and for the tester to create a climate of empathy with the user.

The facilitator should, whenever possible, speak the language of the user being tested. It is important to be aware that even when the testing session is perfectly conducted in the original language. It might be challenging to find the right skills in a closed market with limited UX training, such as countries where the practice of UX is still maturing.

3.6.1 Lessons from the Field: International Phones Corp

An international communications company started a study to understand the users’ perception of its own pages versus the competitor pages, and common retailer websites visited in five different countries: Germany, Spain, Netherlands, United Kingdom, and South Africa.

The study goals involved website benchmarking and usability testing for each country with up to nine websites:

The methodology was centered around an unmoderated online usability study using participants who were otherwise unfamiliar with the proposition or brand.

Each user performed up to six tasks for each website, based around:

The user feedback was overwhelmingly negative for the company’s website as well as the competitors for nearly all countries. The users tended to prefer the retailers’ websites, which had a smoother user journey and ironed out many of the usability flaws that the company’s own website displayed.

Users also had a negative reaction toward the inconsistent experience offered by the localized website, particularly in terms of performance and differing layouts and templates.