Mental Manifests

Abstract

Aesthetics are governed by the influence of cultural imperatives. Humans think about shapes and colors differently, influenced by different perspectives of time and perception. These differences are motivated by the institutions and behavior patterns that we observe in those around us, and that we are exposed to since birth, but to what extent do they affect the way we think about interaction, others, and ourselves? What role do we play in the stories we spin about others like us – and the rules that divide us? And how to leverage these differences in the realm of user experience?

Keywords

Mental manifests; cultural model; attitude; social value; storytelling; metaphors; culture; narrative

5.1 Aesthetics and Cultural Imperatives

“I have known everything,” said Lord Henry, with a sad look in his eyes, “but I am always ready for a new emotion.”

Oscar Wilde, The Picture of Dorian Grey

One look at a Buddhist temple and one can see the materialization of Japanese aesthetics and its particular qualities of musicality and rhythm. However, this underlying principle reveals itself even in the way cinema is made in the region and, in particular, in the movie editing of one of their media exports: Japanese anime. Anime animation is usually characterized by an abundance of characters with exaggeratedly slim limbs, outlandish and emotional stories, and cartoonish facial expressions of surprise. However, some of the most successful animes are deservedly in the canon of best animated features ever (e.g., Akira, Howl’s Moving Castle, Spirited Away, among others).

The way that these types of movies treat key scenes is worthy of attention. Each moment is carefully preceded of a single beat that allows the viewer to anticipate the reaction of the character, particularly in an emotional scene. Dramatic pauses are used sparingly in order to allow the audience to engage emotively with the situation, and to allow the scene to unravel before continuing the story.

Part of the reason behind the prevalent use of dramatic pauses in Japanese animation is the need for economy given the limited technical and budget conditions of earlier Anime, but their use also provides a berth to shore the audience’s attention unto. Movie editors use a similar technique to give a scene emotional gravitas by changing its tempo and emotional punctuation. Timing is everything when you want to make an impact on the audience gracefully and in a lasting manner, and this is an essential principle of web design as well.

Regularity, even in the simplest of templates, allows the designer to maximize communication on a medium that demands balance and conciseness. This close relationship between rhythm and linearity plays an essential role in the different design strategies that a Japanese designer may adopt as opposed to its Western counterpart, and the way their minds may process information and formulate new ideas.

This difference in cognitive styles is a complex and contentious subject area with many conflicting theories and very many instruments to determine the different perspectives of cognitive style and in addition, the cultural background of an individual may affect the outcome of any cognitive test. However, there is a body of research (Markus & Kitayama, 1991; Witkin & Berry, 1975) that correlates cultural characteristics and the thinking or cognitive style of certain populations.

The relationship between culture and cognition has been considered in wildly different ways according to the dominant strands of social psychology. The concept that culture could influence basic mechanisms of thought was generally avoided by the prevailing psychological models and has only recently started to receive attention. To understand how culture can shape cognition, a little thought experiment applies: imagine in your head a door handle. Did you picture a door lever or a knob? Both are ergonomically different and prevalent in different areas of the globe. Door knobs tend to be more popular in the United States, whereas levers are most often used in Europe. This difference is even clear in our symbolic associations. Whereas the dove is the bird representing peace in the West, the white crane is the most popular symbol in Asia. This is but one of many differences that have loaded terms like “Westerners” and “Easterners,” which are apparently differentiating and homogeneous, but carry their own share of stereotyping. Richard Nisbett, in his work The geography of thought, suggests that the cognitive style or intellectual approach have been influenced by centuries of separate sets of beliefs and aesthetic sensibilities:

Like ancient Greek philosophers, modern Westerners see a world of objects—discrete and unconnected things. Like ancient Chinese philosophers, modern Asians are inclined to see a world of substances—continuous masses of matter. The Westerner sees an abstract statue where the Asian sees a piece of marble; the Westerner sees a wall where the Asian sees concrete. There is much other evidence—of a historical, anecdotal, and systematic scientific nature—indicating that Westerners have an analytic view focusing on salient objects and their attributes, whereas Easterners have a holistic view focusing on continuities in substances and relationships in the environment.

Nisbett (2003, p. 82)

According to Nisbett, this distinction between holistic and analytic reasoning marks a difference in cultural identity between these two different cognitive styles. Nisbett distinguishes holistic reasoning as “an orientation to the context or field as a whole, including attention to relationships between a focal object and the field, and a preference for explaining and predicting events on the basis of such relationships” (Nisbett, Peng, Choi & Norenzayan, 2001, p. 293).

On the other hand, analytic thought “involves a detachment of the object from its context, a tendency to focus on attributes of the object to assign it to categories, and a preference for using rules about the categories to explain and predict the objects behavior” (Nisbett et al., 2001, p. 293).

These notions build on Witkin’s definition of subjects as “field dependent” or “field independent” (1967), who pioneered the theory of cognitive styles. Later studies (Hayes & Allinson 1988; Nisbett & Norenzayan 2002) have shown the impact of cultural background on the way information is learned and processed, particularly in light of the holistic and analytical dimensions.

Both styles of thinking are deeply connected with their civilizational roots. The Greek favored a scientific method of decomposing Nature’s elements into causality, consequence, and actors. Their epistemology was centered around analysis and the early scientific principle and Chinese rational appeals to a rounder perspective of data as nondiscrete elements.

This is directly reflected in the user attitude in China. Chinese culture is inherently polychronic (a definition first introduced by Edward T. Hall in 1977), where multitasking is common and tasks can be performed simultaneously. Polychronic cultures tend to rely on nurturing and constant attention to ongoing tasks, like scheduling meetings, as opposed to monochronic cultures, which focus on sequential or linear chains of events.

This is directly reflected in the attitude towards web design in China. There is a traditional perception of Chinese websites as hard to navigate with dense, cluttered pieces of content. The reliance on Flash technology, the tendency to have every link open a new tab, and an abundance of links seems to indicate an antiquated attitude towards web design in comparison with the tidy minimalistic designs inspired by Google.

In reality, most contemporary Chinese web design is adopting similar trends to Western design, with bold white space and a minimalism of same-page tasks (Fig. 5.1.1). The fact that the trends in China are more oriented towards sharing with their own social networks and are strictly mobile-based, with desktop sites becoming optional to most companies which instead choose WeChat as a suitable advertising platform.

Another reason for the difference in Chinese web design is the alphabet and its implications for information processing. Cantonese characters are graphically composed by a combination of strokes, and any given character can range from 1 to 60 strokes. The absence of capitalization and Latin indentation and paragraphs contributes to the perception of its “busy look.”

The abundance of links still stumps the average web designer. One of the suggested reasons is that typing in the Chinese alphabet is a difficult task, and the links are supposed to encourage clicking. Chui Chui Tan, editor at Smashing Magazine, has a different opinion: “Chinese use the same keyboards as the West. They use ‘Pinyin’ to input Chinese characters using these alphabet-based keyboards. There are shortcuts. It is fast and easy. It could be slower for Chinese to type in English than in Chinese. Chinese also complain about not being able to find what they are after on a page due to the overwhelming content and links. Instead, they choose to use the search box and skip the homepage.”

Links are often loaded on new tabs because of the traditionally slow connections. The pages continue to load while the users can still continue to read their current page. Flash is used because of its traditional ease to create colorful click-bait that generates ad revenue, but the situation is rapidly changing.

The use of Chinese fonts is also hard to judge at first, as there are still not too many choices on the market and emphasizing Chinese fonts is necessarily difficult because of the alphabet structure. Font sizes also make a difference, because of readability issues, given the complexity of each glyph.

The tendency for complexity is no longer a mainstay of Chinese design. Baidu’s uncanny similarity to Google’s cool minimalism is an example of success with an apparently unappealing Western design.

5.2 Personal Attitudes and Social Values

So, here you are

too foreign for home

too foreign for here.

never enough for both.

Ijeoma Umebinyuo, diaspora blues

Cultures are conventionally divided into traditional and nontraditional. An empirically-based scientific culture is often identified as nontraditional, whereas mythical belief-centered cultures are defined as traditional.

When thinking about modern beliefs and the role of science in our everyday interaction with world, it is difficult to uphold this distinction. The doctor is our shaman. Technology is our God. (And yet fundamentalism is rising and one of the main political issues of our time.) There is only one step of separation between this social arrangement and similar roles played by other actors in nonindustrialized societies, which present a variety of beliefs and the integration of age-old values and principles. It further blurs the line between what was conventionalized as “primitive cultures” and the “new” manifestations the same roles have come to absorb.

One important distinction between traditional culture and nontraditional culture is that the first one tends to be geographically restricted, whereas the latter has spread like wildfire throughout the world. Traditional cultures represent a fixed set of social roles, routines, and ideas about reality and the world. Nontraditional cultures are, for the most part, fluid, interactive, and privilege individual social mobility, along with a strong prevalence of modern technology.

As an example, the Japanese perspective on entrepreneurship was traditionally quite negative. The keiretsu structure in Japanese society, which links different companies as a type of business meta-group, is still very prevalent in the economy, and the safety net for new entrepreneurs is extremely limited. However, the rise of young businessmen such as Hiroshi Mikitani, founder of the “Japanese Amazon” and local e-commerce giant Rakuten, served as the beginning of a mass interest in startup companies. Although working in a small company traditionally signaled either limited prospects or a family business, the rise of entrepreneurship allowed smaller and more agile companies to thrive in an otherwise very monopolistic market (Fig. 5.2.1).

Social psychologist Shalom Schwartz argued that “the prevailing value emphases in a society may be the most central feature of culture,” stating that a singular value represents the “shared conceptions of what is good and desirable in the culture, the cultural ideals” (Schwartz, 2006, pp. 138–139).

Schwartz has since developed a model of 10 fundamental values that determine the motivation and reception of interactive factors. These values are important to understand the role of these values in decision-making processes when the user is faced with a product value proposition. Schwartz defends that users make choices based on a set of wishes and goals, which can be traced to an hierarchy of perceptions of the actual product which, after interaction, correlate with a value. For instance, a user can perceive a website as having a sturdy encryption procedure during payment, which triggers a set of consequences, namely the confident use of a credit card, and correlates to the final or instrumental value, which is the general need to feel secure.

Schwartz suggested a value inventory that would be closer to grouping different values under one sole category:

• Power: Fundamentally correlated with social status and one’s reputation, as well as the control over others. Public image and social recognition are key to the cultures associated with this.

• Achievement: The values from the achievement of goals and personal fulfilment. Associated with ambition and a sense of individual success.

• Hedonism: Solitary or egoistic gratification through self-indulgence.

• Stimulation: Thrills and the excitement of something new and difference drives individuals who are particularly creative or bent on artistry.

• Self-direction: Closely linked to more individual perspectives on social roles, this value category is related to the independence of thought and actions displayed by people.

• Universalism: Related to tolerance and mutual appreciation, as well the promotion of peace and equality. Socially tolerant societies are the most universalist.

• Benevolence: It is closely related to the preservation and protection of others and immediate connections (friends and emotional relationships especially).

• Tradition: Respect for what has come before, and keeping in with the previous customs in place. Normally associated with a more conservative mindset and averse to change.

• Conformity: Restraint and obedience to hierarchies and norms. Control is normally equated with self-discipline and obedience.

• Security: Associated with harmony and stability to a higher degree than normal. Health awareness and cleanliness of habits and personal stance are seen as primary concerns.

Understanding the values that matter to your users is paramount in order to adapt copy and content suitably. For instance, Spain consistently ranks highly on hedonism while the United Kingdom ranks highly in the achievement value set. This sense of achievement may be well perceived in Anglo-American culture, but the perception of an individual who displayed this type of behavior would be very negative in China and similar countries where these dimensions are not as pronounced (Fig. 5.2.2).

5.3 Persuasion and Reason

Character may almost be called the most effective means of persuasion.

Aristotle

Everything is a dialogue, either with others or the environment. The apps we use speak to us, either directly through the content displayed on-screen or with whispers in the background of our push notification list. We tend to engage with software as if they are a teammate or a person, and this can easily assume the role of communication accompanied with collaboration.

Similarly, as in conversations everyday, the systems we interact with everyday are trying their best to persuade us. We can be swayed by influence into buying something or accepting something. Our interactions are directly affected by the way we see reality, and reality is the compound of our expectations plus our influences, social, and otherwise.

As an example, take Steve Jobs. Hailed in many quarters as one of the greatest marketing minds of the 20th century, his path was obstinate and of single purpose. During his addresses for new product releases, he became known for creating what was called a “distorted reality field,” where he was able to convince his audience that, among other unbelievable ideas, the iPad was a good product name.

Steve Jobs conveyed this feeling through rhetorical ability and technical acuity, but most importantly, he did it out with conviction. Jobs successfully persuaded audiences and markets the world over to change their attitude towards smartphones, touchscreens, and digitally-compressed music.

Like other aspects of interaction, persuasion is meant to convince the user to adopt a specific attitude or behavior and, like any method to convince someone, it can also be abused. An interface can convince the unaware user to click on an advertising banner, or to avoid reading terms and conditions that may spare months in a court procedure.

However, the basic focus of persuasive patterns is to address and influence behavioral triggers in users, priming their psychological biases to stimulate specific actions, which are positive either to the system or to the user itself. Applying a trigger in a micro-interaction or conveying the right tone is key to persuade the user to a single click that could mean conversion, and success in the ultimate goal of the buy-sell dynamic.

Theorists like Bob Cialdini argue that there are six basic methods of influencing others. These basic principles have been adapted into multiple interaction patterns, developing a unique set of attributes for each.

• Authority: Assume the role of an expert and a trustworthy authority on a subject or domain. More individualistic societies like Sweden and Denmark, where there is a low power distance between the members of the group, would tend to challenge authority more readily, an authoritative voice in the person of an expert would not necessarily resonate as clearly and quickly as a clear-cut minimal-fuss solution offered through experience. Scandinavia has a culture of consensus is in place and hierarchies are embedded in the group’s relationships (Fig. 5.3.1).

On the other hand, high-context cultures like those prevalent in the Middle East, where families are extended and hierarchies are fairly rigid, have a greater bias towards the influence of those in their immediate network.

• Commitment and consistency: By allowing somebody to spend time or invest effort on an activity, it is easier to request a favor in return. For example, to request the full investment in a yearly subscription after offering 2 months for free. Past experiments in conformity studies have shown that there is a difference in commitment and conformity between different cultures. There is a strong relation between the conformity in group consensus and collectivistic societies (Bond & Smith, 1996). The willingness to comply is also stronger in more collectivistic societies like those in Asian countries (Cialdini et al., 1999).

• Liking bias: We are swayed by personal preference into choice. We tend to pardon those we like faster than those we do not like. Brands operate across similar lines. The qualities perceived in the way a company communicates set the stage for the client’s perceptions. This is one of the reasons why a familiar and friendly tone is used on apps and web services, building in colloquialism and humor in the communication between user and brand. There is a clear link between the perceived communication tone of a company’s content, and being receptive towards the products or services it offers.

• Reciprocity: The principle of doing something in exchange for a favor or to repay an action. For example, we are more likely to retweet users who have retweeted us. Another example is the way that an interaction contrasts reward versus reciprocity. There is evidence that users tend to engage more in a situation of reciprocity rather than reward. For example, users tend to respond better when a registration form is presented after a complementary article, and the conversion rate is significantly higher than if the content is locked behind a register-first gate (Gamberini et al., 2007). Reciprocity tends to work better than reward in the case of free content, something that Radiohead and Pretty Lights can attest to with their pay-what-you-will experiments for otherwise free albums.

• Scarcity: Everything seems more appealing when it is presented as being in short availability. This principle can be coupled with loss aversion, which reflects our unwillingness to part with something that we already have over the possibility of winning something potentially much better. People feel a loss much more vividly than a win.

• Social proof: Reviews and validation by other trusted people play a major role in our decision-making. Social proof happens in particular when we are looking for validation of our own decisions with other people. This is one of the reasons why we look at third-party sites and look at popularity indicators to feel confident about our own choices. In general, we feel more confident about comparing our opinions with those of others and these are instrumental in gauging our own perception. There is a clear difference in how this is manifested across the manifold of multiculturalism. Advertisements in Korea tended to focus on the advantages of buying a product due to the example of others rather than the inherent advantages of the product (Han & Shavitt, 1994), promoting group benefits rather than the benefits of the product itself. The tendency is countered by most Western advertisements, particularly in the United States (Fig. 5.3.2).

5.3.1 Researching

Qualitative research is key to understand the form and applicability that these triggers can have in the context of a user journey. Competitive benchmarking provides a good insight into the stimuli already in place in the marketplace, but in order to start with the source and not the consequence, a combination of methods (e.g., interviews and/or workshops) can provide a solid foundation on what the general biases and expectations of users are in terms of their behavior on the webpage.

By asking questions like “what are your greatest fears when it comes to booking a trip?” or “can you rate how important it is to you to have a recommendation on an hotel or a flight?”, it is possible to group this input under actual persuasive themes that can be mapped to persuasive patterns. These themes can be groups: Cognition, Perception and Memory, Gamification, and Social.

You can approach each one of those persuasive patterns as “themes” and produce a set of recommendations on the general users’ biases. This then can be used by the content and design teams in order to guide decisions on the actual placement, timing, and tone of the messages.

Designing for persuasion is essentially designing an interactive experience that influences and impacts behavior on a preconscious level. An influence analysis allows you to generate ideas on what the actual desired attitude and behavior changes are. By making these explicit, you can then manipulate and change these behaviors much more effectively.

5.3.2 Interview With Masaaki Kurosu

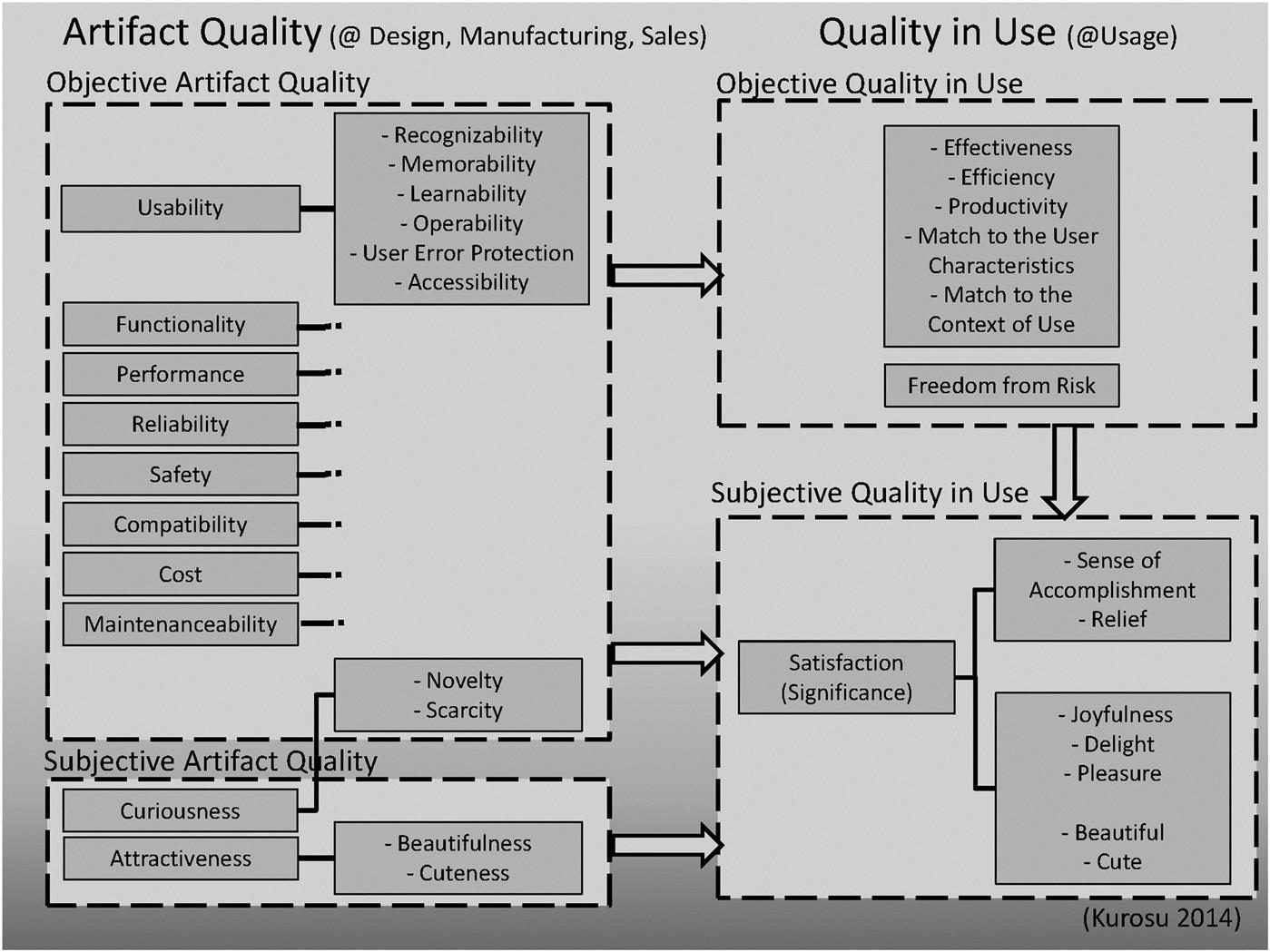

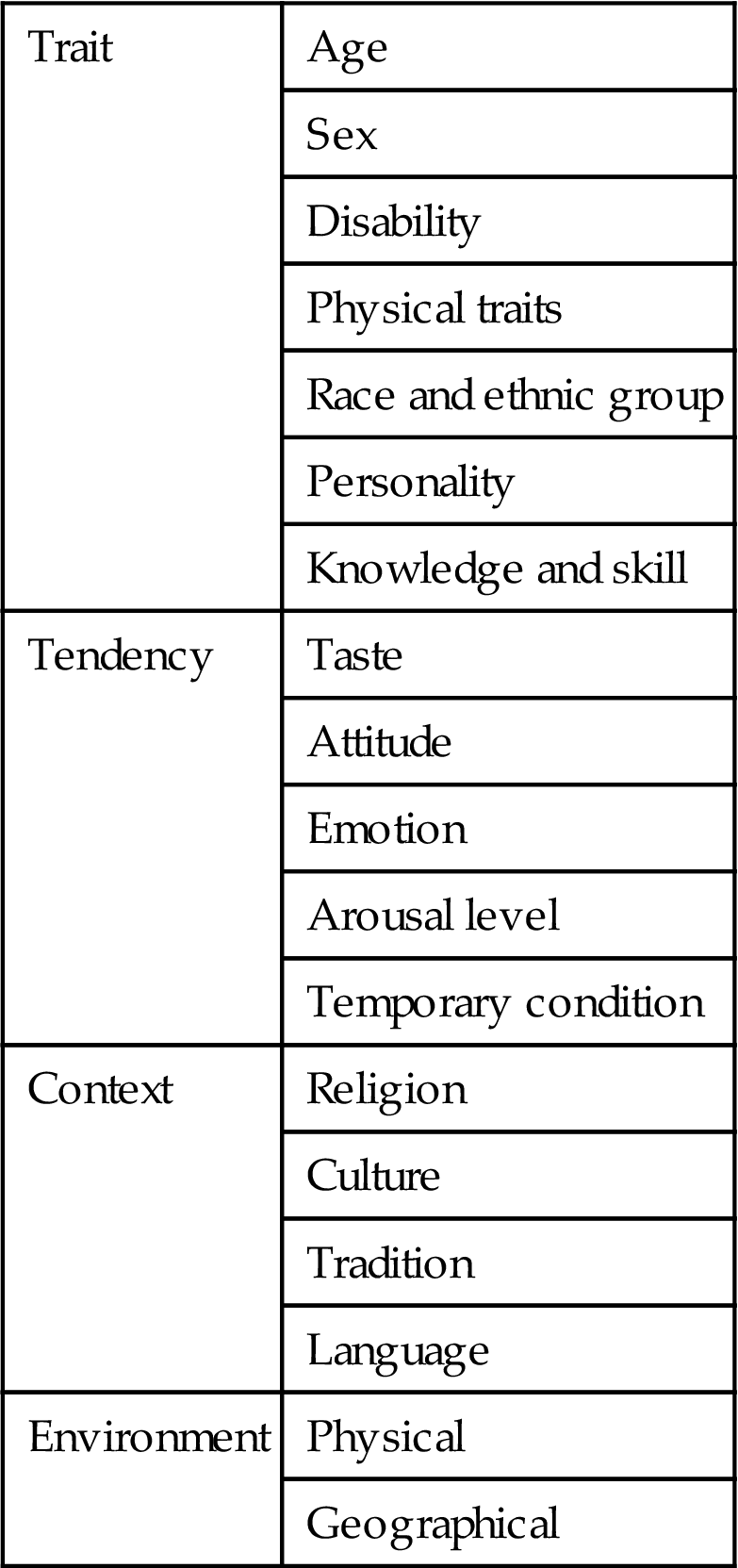

Dr. Masaaki Kurosu is one of the foremost thinkers in contemporary HCI research and author of “Theory of User Engineering” (2016). His works on the relationship between cultural usability and UI design have pioneered a new perception of User Experience and ushered in a new research approach more focused on triggering affective interactions, based on the Artifact Evolution Theory, which connects human factors specific to local populations with the progressive enhancement of technology objects (Table 5.3.1).

Your recent research has focused on the importance of experience design. What is the importance of emotion engineering in comparison to cultural factors in user engineering?

In this figure, I classified quality characteristics into “objective and subjective” vs “artifact quality and quality in use.” The quality in use is related to the UX and the artifact quality including usability is just clarifying the ability or the potential of artifacts. The emotion engineering that is called as Kansei engineering in Japan is related to the subjective quality characteristics both in artifact quality and quality in use. As Hassenzhal pointed out, practical attributes (objective quality characteristics in my figure) and hedonic attributes (subjective quality characteristics in my figure and is related to Kansei engineering) are both important. Culture, in this context, is more related to the subjective quality characteristics.

What is your opinion on the emphasis in recent years on diversity- and usability-oriented design?

Diversity is a fundamental dimension that we’ll have to focus on when designing artifacts.

Government regulation on digital accessibility is not yet a universal trend. Do you think this will change in the future?

Yes, government regulations should back up the universal design. Just summarizing a guideline is just a one step toward the regulations and is not enough. The legal force is quite important.

Seeing that culture can be interpreted as the common set of values and learned responses that affect the way we interact with objects and the world around us (it is known that culture can impact visual recognition and body language), can culture impact usability design in a meaningful objective way?

First of all, from the viewpoint of AET (Artifact Evolution Theory) that I'm establishing, there are various artifacts from culture to culture for achieving the same goal. For example, eating tools include, “knife, fork and spoon” in Western countries, “chopsticks” in East Asia, “spoon and knife” in South Eastern Asia and “hand” in various places in the world. Each tool has its own usability in relation to shape, size, weight, stickiness, etc. of the foods. Example is the chopsticks in Japan where the steak is sometimes cut as a piece of dice before serving it to the table and people don’t need to use the knife and use just the chopsticks. Similar examples can be found so many including the artifact for toilet behavior, washing clothes, cleaning houses, etc. etc. They depend so much on the circumstances and serve to the improvement of usability.

Concerning the diversities you listed, do you think that context can affect tendencies and vice-versa?

Tendencies are frequently characteristic to the person and generally are not much related to the context. But the exception is the case where a person with certain tendency selects the context from many alternatives. A good example is the case of selecting coffee shops - traditional café, Starbucks, etc.

Table 5.3.1

Qualities of Diversity Among Users According to the Artifact Evolution Theory (Kurosu, 2014)

| Trait | Age |

| Sex | |

| Disability | |

| Physical traits | |

| Race and ethnic group | |

| Personality | |

| Knowledge and skill | |

| Tendency | Taste |

| Attitude | |

| Emotion | |

| Arousal level | |

| Temporary condition | |

| Context | Religion |

| Culture | |

| Tradition | |

| Language | |

| Environment | Physical |

| Geographical |

5.4 Cultural Models

The best teachers impart knowledge through sleight of hand, like a magician.

Kate Betts

Ma is one of the most prevalent concepts in Japanese tradition. Ma describes an interval between two or more spatial or temporal things and events. It is an ancient Japanese religio-aesthetic paradigm that brings about a collapse of distinctive (objective) worlds, and even of time and space itself. Richard Pilgrim states that “Ma takes us to a boundary situation at the edge of thinking and the edge of all processes of locating things.” The acknowledgment of these “pregnant nothings” reinforces the importance of the mind-state of mushin (no-mind), and such “empty nothings” are absolutely central to Buddhist, Taoist, and Shintoist thought.

Emotions are universal, whereas facial expressions are relatively universal. A study by psychologist Paul Ekman where photographs of faces were shown to people in over 20 Western countries and 11 preliterate communities in Africa has shown a significantly high percentage of correct interpretations: over 90% of respondents in all the cultures successfully identified smiling faces.

But the question remains on whether these expressions are learned or innate. If we look at a baby on a crib, and put up a drop of vinegar on their lips, the reaction is quite universal: disgust. Neonates in general are able to smile and frown seemingly from birth, suggesting that facial expressions are an inherent component of being human.

However, interpreting facial expressions is a different matter. Several people claim to have difficulty recognizing members of another race, especially in a crowd, but culture influences this power of recognition to a deep degree. Research has shown that Chinese-Americans, e.g., can recognize the facial expressions of Americans more promptly than those displayed by other Chinese people living in China. The same findings have been observed in African-Americans. Respondents identified more quickly and more promptly the expressions on the faces of those they contacted with on a daily basis than those in other cultures.

The way we process information is largely related to culture, and the cleavage between the Western analytic and the Eastern holistic thought splits into different components. Nisbett proposed that the two intellectual approaches differ significantly:

Analytic thinkers tend to see things as discrete individual entities, paying closer attention to the objects themselves rather than anything else surrounding them, and assigning things to categories more promptly. Formal models and rules tend to govern their thinking.

Holistic thinkers focus on continuity and the relationships between things, as one thing in isolation is not necessarily the most important element when thinking about a concrete situation.

Both styles of thinking are deeply connected with their civilizational roots. The Greek favored a scientific method of decomposing Nature’s elements into causality, consequence, and actors. Their epistemology was centered around analysis, whereas the Chinese rationale is holistic, worried about the context and the wider integration of elements.

This influences the way people of either cultural background may think about a problem, a piece of information, and themselves. Quantification is, however, an issue since there is a degree of fuzziness in the approaches. Cultural models were created as an answer to the unsurmountable problem of quantifying human thought in terms of their values and social contexts.

These models are primarily monocultural and thus necessarily incomplete, but they are useful to ascertain the role that certain values play in thought. The models proposed by Hall are possibly the most famous, as he has proposed a variable and quantitative definition of culture as a model composed of different dimensions. Each of these dimensions consist of a character or trait that all cultures possess to a greater or lesser extent, like their perspective of time:

• Low-context: Conversations should have all the information required for a successful interaction, with communication styles being more explicit.

• High-context: Not everything has to be explicit in the interaction. Roles and information are often subdued elements in the conversation, with an indirect communication style (formal/informal, written/symbolic).

Hofstede’s model is based on five cultural dimensions, based on his work with 80 countries:

The premise is that cultures with a high level of individualism have a low-context communication style, preferring a more explicit and formal communication style. Examples of this type of communication include the Swiss, Germans, Scandinavians, Anglo-Americans, English.

On the other hand, collectivism is correlated with high-context communication, where interactions are seen as more implicit and symbolic. Pictorial and visual communication is preferred by peoples like Japanese, Arabs, Latin American, Italian-Spanish, and French.

On this level, high-context cultures tend to be prefer indirect and transformational advertising messages creating emotions through pictures and entertainment (France, Japan). Low-context cultures privilege direct and rational advertising messages providing product information (Germany, United States).

Transposing these assumptions unto a layout and visual design, written text tends to be more informational and rational in nature in low-context communication contexts. High-context communication contexts tend to privilege layouts with visuals pitched with a more entertainment or emotional slant.

These models largely aim at providing a predictive framework for generalized patterns of behavior and their usage has been questioned in many academic quarters. The level of unpredictability and the complex nature of multivariate cultures even within a dominating discourse has given rise to a set of theories around effective brand communication across cultures.

For example, Cateora et al. (2012) has suggested an international marketing model split into two basic sets of factors:

• “Uncontrollables,” which consist of everything that a corporation cannot affect or change, like laws, economic situation, geopolitics, standards;

• “Controllables,” the actual marketing strategies and approaches that a company can manipulate.

There is arguably a correlation between content appeal and brand perception, and not only on a local basis. Local websites of global consumer brands are sometimes standardized on a worldwide basis. This allows the brands to keep the layout and navigation consistent by usually relying on the same template. This consistency comes at the cost of specialization, but it is cost-effective for certain markets. French food brands are sometimes compliant with a high-context style, whereas German car brands (Mercedes-Benz in Italy, Lancia in Germany) can be low-context regardless of the market. Websites of global companies tend to be strongly standardized and dominated by very linear value propositions.

Users seldom visit technology brand websites, unless they are looking for specific information on products, particularly of a technical nature, like specifications. For larger companies, the sheer website volume and deeply structured content can work in the favor of giving a good support resource for the end-client.

With the necessities of keeping a brand presence consistent on a worldwide basis, the “country-of-origin” effect can be difficult to achieve, unless the product depictions are already viewed in a positive light in the target countries. Ensuring a balance in the advertising and social media channels is key to ensure that local users across different markets capture the spirit of the brand. The brand can speak with many voices, but the message should be the same.

Some researchers have tried to correlate the relationship between access and receptivity to the Internet with cultural dimensions like uncertainty avoidance, arguing that individualistic risk-taking societies showed a quicker dissemination of their online presence (Capurro, 2006), especially with the quick rise of mobile in Asia and Africa.

5.4.1 Lessons from the Field:

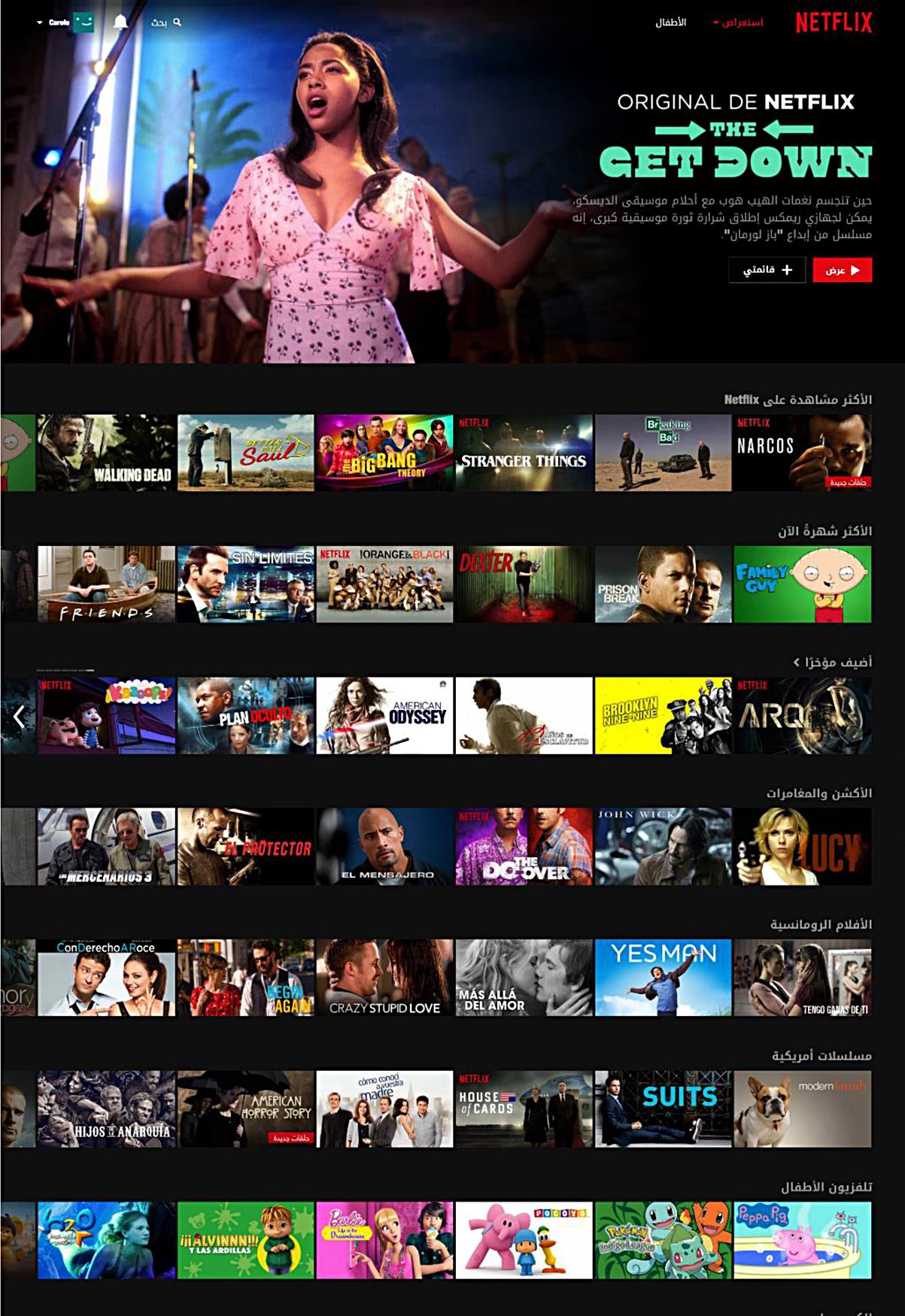

Netflix is one of the leading VOD producers, streaming movies and series to over 190 countries. Its original productions, like House of Cards have earned multiple awards, and it is by far the biggest provider of high-budget content streaming outside of YouTube, with 34 million subscribers outside of the United States. It has successfully introduced terms like “binge-watching” to audiences raised on television and video games across the world, and its aggressive international strategy has taken it to a new level.

Its design is also a master case study in iterative testing. Over the years, the interface has been subjected to a number of A/B testing iterations, with click rate and conversions analytics acting as significant factors of decision in the best approach to take (Fig. 5.4.1).

One of the most ubiquitous factors in the Netflix interface is the absence of a standard list of additions or the full contents of the collection. This allows the service to adapt and render recommendations based on previously seen content and the potential interests of the viewer. In a word, Netflix can push premium content and highlighted material on the viewer by encouraging conversions through convenient access.

Although there are a number of third-party websites and blogs that claim to provide the full list of the Netflix catalog, the service has yet to implement any similar features on its own website. Search engine indexing is also blocked to protect the opacity of its offerings with a paywall.

Netflix is arguably the biggest contender in the West for video-streaming services, but the variety of services worldwide is expanding constantly. These other VOD services are smaller, but have a strong focus on local content that acts as unique selling point when compared to Netflix. By comparison, in South Africa, ShowMax and OnTapTV are two of the biggest services in the continent. The former is backed by media giants Naspers, the largest company in Africa and one of the biggest digital companies in the world.

5.5 Appropriation and Appropriateness

The anonymity of typification is inversely proportional to fullness of content.

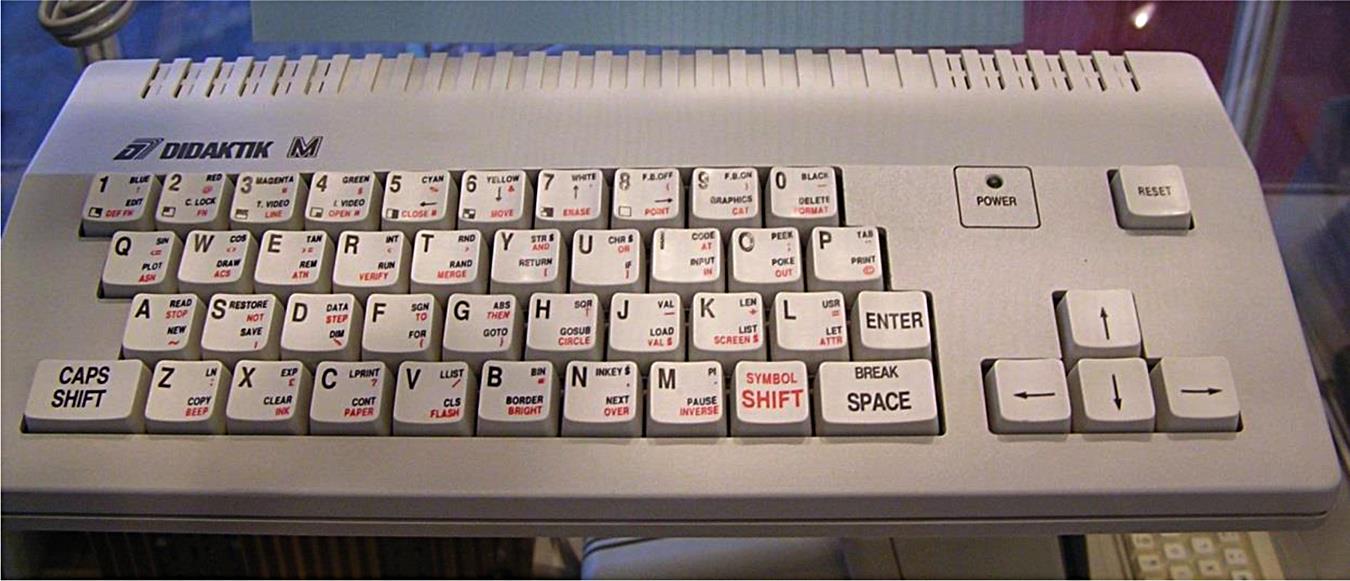

In the days preceding the fall of the Iron Curtain, technology was a limited good and new computer models were hard to find. The implementation of the CoCom embargo made the import of computer systems into the old URSS nearly impossible and, as a result, the new mass-produced personal computer models that flooded American and European stores in the late 1970s and 1980s were inaccessible to the Russian public.

However, that did not stop Russian engineers from finding their own solution to this particular problem. A few systems were smuggled into the URSS through Poland and Czechoslovakia, and found their way to university cities like Leningrad and Lvov, where engineers started taking them apart and figuring out how these particular computers ticked. Until then, Russian computers had been massive mainframe systems occupying that required both costly maintenance and a team of specialists. Now, small compact systems imported from the West allowed a glimpse of what mass computing could look like.

One of the smuggled systems was the ZX Spectrum, a small 48 KB unit running on a BASIC operating system (Fig. 5.5.1). This system was a worldwide success in 1982, leading to a knighthood for its inventor, but like many other appliances of its kind, failed to penetrate the folds of the Iron Curtain. However, in the early 1980s, homespun blueprints and schematics of the system soon started circulating and in the following years, Russian engineers in various points of the country started a myriad variations and clones of the system sprouted in the Eastern Bloc countries. Excluded from regular trade routes and capitalist imports, the local versions of these systems were adapted in order to work with easily obtainable Russian parts. Even the technological limitations of these homemade computers did not deter the budding home engineer. These devices had only a black-and-white display, broke down often, and were relatively expensive to build if you could not source the right parts. But they proved a success in a country where technology was constrained by ideological as much as economic reasons.

Russia exemplified one of the great equalizers of our time: technology. By appropriating the technology produced in another country and making it accessible, it created an internal domestic need for technology consumption. As a result, a specialized black market developed and became an essential resource for the budding home electrical engineer.

What Didaktik M and others like it exemplify is that demand will always circumvent limits in the offer if it is strong enough—especially with a bit of resourcefulness. The need for innovation comes as a response to the local needs rather than a drive unto itself, and that is the motivation behind, among others, many African design projects. In terms of usage, mobile money and small business lending were at their largest with the user bases in Kenya, Nigeria, and Uganda, particularly with the M-Pepea project, which focused on providing emergency credit to those without credit cards or bank loans on a purely mobile platform. Design can be calculated to fulfill social and financial needs, but it can also operate on a personal level, in our homes. According to Eurostat, rented housing has increased in the European market to 20% in 2014, and the need to express oneself through decoration of a personal domestic space has taken a step back into oblivion. Apartments have become transient spaces, and young professionals (aged 25–35 years) renting furnished houses seldom make any changes for the sake of personal decoration. The concept of “home” has changed and is usually associated with past memories or nostalgic associations for those who have lived in family homes. With little time or inclination to develop and endeavor on a new space of their own, their “language” of internal decoration is instead “borrowed” from an existing vernacular. This is one of the reasons for Ikea’s success, according to Alison J. Clarke, Professor of design history at Vienna: “Ikea [is] the exact opposite of self-expression. It is self-expression within a limited repertoire” (in “Reflections: The real reason you still shop at Ikea,” A Travel Blog About Home, July 28, 2016). In a world where the need for self-expression is becoming a global tendency, Ikea provides a good insight into the importance of an intimate canvas that can be assigned an emotional value. The Ikea furniture, as far as physical artifacts go, provides a minimalistic framework for emotional and cultural expression. Values relevant to the buyers have been applied to the diffuse form of Swedish design that has crossed over the world in the past 20 years and appropriated cultural values implicit in the local maelstrom.

5.6 Stereotypes and Generalizations

Once you label me you negate me.

Søren Kierkegaard

A distinct British butler waddles tentatively around an empty dinner table with clearly too many neatly set plates in place. The dining room is swanky, and 19th-century crockery provides a neglected backdrop of high-class abandonment. The butler rings a dusty bell by the corner. An old woman in an elegant black lacy dress enter tentatively at the top of the staircase and is led by the hand to the head of the empty dinner table. What ensues is a 15-minute sketch with the ancient aristocrat hosting a dinner party for nobody at all, with the butler assuming the role of each guest in turn for both drinks and food, following the “same procedure as every year”.

The 1963 comedy sketch is entitled Dinner for One, and despite the fact that both actors in it and the setting are distinctly British, it has been a staple of every single New Year’s Eve schedule in German television and has gone on to become the most repeated program ever. This quirky piece of pantomime has since gone to gain similar staple holiday programming status in other countries like Sweden, Finland, and Australia. Yet, the sketch remains largely unknown in the United Kingdom and the United States, and it never actually aired in either country.

The popularity of the sketch has befuddled many English speakers. It was not conceived to appeal to an international audience like Mr. Bean. It indulges in a light parody of dementia, features acrimonious amounts of booze (which led to its banning in Switzerland for several years), and features the beguiled suggestion of senior citizen sex. However, yelling out “Same procedure as last year?” will likely get you a free round in a Bavarian klappe.

This example of distinctly European cultural contamination shows the illusion of single group identities. Our mind is biased towards difference. We perceive the world not by what is similar, but following the differences between the various elements. As a rule, our cognition is steered towards limits by contrast of colors, shapes, and identities. The hard sharp outlines of things allow us to interpret them and interact with the world more comfortably. We rely on contrast to know when a room gets cold and unpleasant, or when an especially spicy chili creeps into our food. As a race bent on survival, we do not like surprises (for the most part). Homogeneity and assuredness of expectations are not only widespread, but a condition of our reptilian brain.

In order to minimize the probability of jumping off a cliff, we also tell ourselves that we are special and often lie to ourselves about the actual worth of our achievements, looks, and actions. This plays a complex role in our social relations as well. This mental process is called positive distinctiveness, and it is particularly important in giving us our group identity. We perceive those closer to us and more similar to us as part of our group, and more relevant than other groups, and this encompasses different levels of separation between the designer and the actual audience.

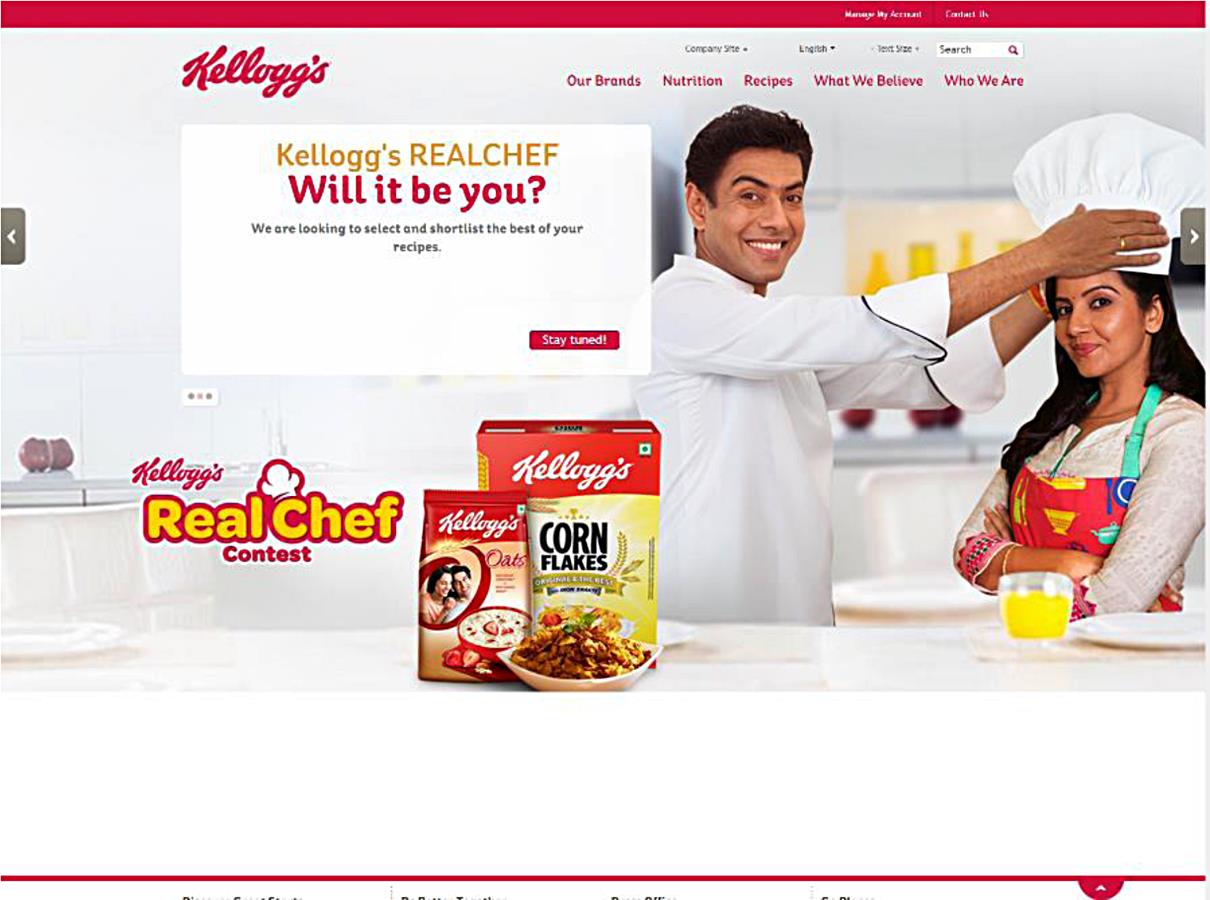

5.6.1 Case Study: Curries, Cereal, and Masturbation

Corn Flakes is one of the most popular breakfast cereals in the world. It was originally created in 1894 by the ultra-religious Dr. John Harvey Kellogg as a breakfast food for the patients staying at his popular sanitarium and health spa. (Incredibly, it was part of a regimen of bland nutritious food meant to purify the body of the “solitary vice” of masturbation.) Over the years, it developed into one of the staples of American and European breakfasts and the best-selling brand of cereal in these continents. The brand experienced a tremendous growth during the 1980s, when it captured nearly half the United States market for breakfast cereals, generating an annual revenue exceeding 6 billion USD. However, in the early 1990s, Kellogg’s found its U.S. market share eroded by its closest competitor, General Mills, and the company’s growth began drooping (Fig. 5.6.1).

It made sense then that Kellogg’s tried to expand to emerging markets, taking the success of its cereal branding to then-untapped economies—starting with India. According to Homi Bhabha, however, the brand did not research into local habits deeply enough: “Kellogg’s set up a branch in India and started producing corn flakes...What they did not realize was that Indians, rather like the Chinese, think that to start the day with something cold—like cold milk on your cereal—is a shock to the system. And if you pour warm milk on Kellogg’s Corn Flakes, they instantly turn into wet paper” (Homi Bhabha in “A Humanist Who Knows Corn Flakes”, 2005: 64–65).

Indian breakfasts usually involve hearty and spicy meals that include Puris, Dosas, and several types of curries.

The local habits initially did not support the appropriation of what had been a breakfast staple elsewhere in the world, and there were different reasons behind the low acceptance engendered in the market.

An exclusively sweet and cold breakfast was not common to the Indian diet, and Kellogg’s initially positioned Corn Flakes as a replacement for the entire meal, rather than a complement.

The advertising focused on the its implication that traditional Indian breakfasts were not healthy was also not well received by a culture that attributed a deep familiar and communitarian meaning to the most important meal of the day.

In subsequent campaigns, Kellogg’s backtracked and employed a combination of popular celebrities, cartoon mascots, and promotional events to grow the brand. Although it managed a sustainable, but slow, growth, the initial bad reaction still haunts the company’s strategy.

5.7 Concepts and Metaphors

The brain appears to possess a special area which we might call poetic memory and which records everything that charms or touches us, that makes our lives beautiful...

Milan Kundera

In 1996, Alvin Yeo suggested a way to categorize the different culturally-related components of interfaces into overt and covert factors. All of these factors would be relevant during the localization process. The overt factors are tangible, straightforward, and observable elements, whereas covert factors would be intangible and depend on culture or “special knowledge” (1996).

One of these “intangible elements” is the use of metaphors in user interfaces. From buttons to icons, an user interface is necessarily inferred from common knowledge, which makes them inevitably prone to being biased due to cultural assumptions. For instance, the image of a page turning in the Kindle is driven by a Western metaphor, as the spine is located on the left, with the pages turning right to left. The direction is necessarily inverted in the Arabic world, where books are read the opposite direction.

The appropriate reading direction makes a difference in information perception and processing. In a successful metaphor, imagery should evade instructional text and all information critical to the user should be clear in the context of the image. The affordances must be self-explanatory. On the other hand, in web design, placing a text frame on an image should also be done in a position relative to the image borders, in which case autosizing the text font to fit to the width is usually the safest choice. Communicating something to the user is the result of many factors, but metaphors can condense a huge number of semantic associations and spare the user of lengthy interpretations.

Metaphors are highly contextual, and function within two different modes: analogy and difference. Difference represents a mode of association: two elements which are unrelated or otherwise share any embedded property are equated as either the same or in the same semantic field. Since a metaphor is not a statement of fact, or otherwise truthful, there should also be a common understanding on the semantic field between the metaphor user and the audience. In other words, it means that something “is like” something else, and the interpreter needs to acknowledge the association by knowing both objects. Analogy, on the other hand, involves a comparison or the transfer of shared properties between both objects. Thinking of both objects in the equation becomes interchangeable, and the association becomes a part of the identity of both.

Despite being highly culturally-dependent, metaphors represent the bulk of user interface graphical output. Icons, logos, and headers rely heavily on symbolism and a complex network of semantic associations to provide users with guidance and visual cues as to how elements are used. This is represented by association with familiar aspects of the workplace and everyday life: the “desktop” or the “trashcan” are representations with an entirely different function in the user interface than in our analog everyday life, but the representation is similar and these semiotic traces are understood by the user as basic functionality due to the concrete and familiar concepts represented (Fig. 5.7.1).

Think about the last time when you saw a traffic sign that you could not recognize. For those who have driven in a country other than the one where they first wrecked their parents’ car, the road has seemingly no secrets. We can cross the entire European Union by car and listen to over 35 languages in a single road trip.

Icons are not universal symbols. As metaphors, they are immediately recognizable in some contexts, but their inability to adhere to a unique international standard is clear in the use of different commands and cues. Sometimes, metaphors also transcend the use that initially brought them to life, like the use of a diskette as a symbol for saving data, whereas diskettes are hardly used in popular media since the mid-1990s. Other technologies have similarly influenced the choice of metaphors in UI design. The player metaphor is still used in web graphics, a reminder of times long past when the VCR ruled the world as the central point of contention for families fighting over the remote. This was, of course, before widely accessible digital streaming took over.

American traffic signs are heavily textual and reliant on contextual cues: the difference between signs like “Walk” and “Don’t Walk” is primarily in the eyes of the beholder. The paradigm of mailboxes, as much a cultural artifact as traditional musical instruments, was a major source of adaptation back in the 1990s, when the Inbox icon came to be associated with U.S. mailboxes. Of course, the experience of British, Japanese, and French users was inherently different, as their mailboxes were not shaped like a tall oven. On the other hand, Japanese mailboxes were shaped as garbage bins for the most part. Telephone booths are another example of these transnational differences (Fig. 5.7.2).

Most metaphors used in UI design have been directly influenced by American engineering. Concepts such as buttons, toggling, formal data input, configuration settings, and safety against mistakes are but some of the systems that transited from the internal logic and patterns applied to traditional engineering.

International imagery can be heavily pictoric and symbolic. Symbols representing products that have similar designs all over the world are easily interpreted, like pencils, envelopes, lightbulbs, cars, and scissors.

As a rule of thumb, images should have no text rendered in them. This is a basic internationalization rule, and also one that will allow maximum reusability of content. It is noticeably harder to edit an image for appropriate text, except if the image is in vectorial format. For instance, in the case of Scalable Vector Graphics (SVG) and Photoshop Document (PSD) formats, the text layers may be successfully extracted and interpreted by an external application that helps editors and content managers to alter the content appropriately for different versions of the asset. This is quite time-consuming and, in general, not a pleasant experience for either the original content creator or those who will be responsible for its adaptation.

It is generally much more straightforward to handle assets separately, with content split in between text and imagery.

Visual puns in particular are impregnable between different cultures, unless they are of a viral nature (e.g., lolkatz). Using acronyms or onomatopoeias are likely to not work internationally. “Cute” elements also may well not contribute to the overall understandability level of the interface (Fernandes, 1995). Pictures should show the maximum amount of information with the minimum level of detail. Consider how universal design works in the context of devices. An app will have to render a PNG with millions of colors in an understandable way and still ensure that users will have the necessary understanding.

Visual messages do not need to be linked to a language. Icons gain in meaning as they become more akin to an actual physical object relevant to the local culture, but not too much that interpretation is lost. Even metaphors that may seem universal, like the lightbulb for an “eureka” moment, are not actually good representations thereof.

5.8 Never-ending Stories

Humans have always been mythmakers.

A short history of myth

Enigmatic German wolves dressed as suspicious grandmothers. Desert desires and courageous thieves in the midst of the Arabian nights. Old men digging their way across mountains in the hardship of Chinese rice fields.

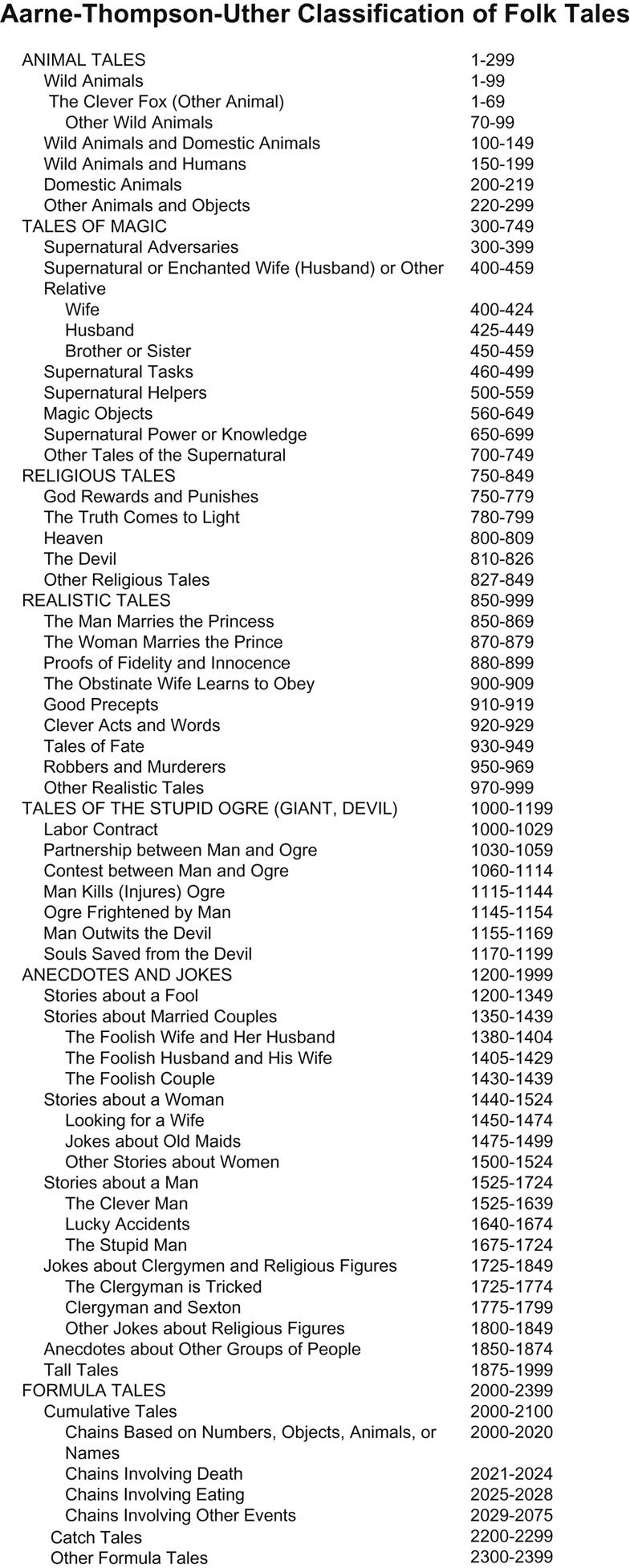

Folk tales are remarkable cultural legacies. They hold the key to the social principles of a culture and reflect perceptions and beliefs of the local people. Their understated (and often euphemized) darkness and animism usually follow a formula and an overarching narrative template. They are sometimes idealistic to a fault, sometimes chillingly creepy (Fig. 5.8.1).

Yet these stories are also remarkably consistent across languages. Snow White, for instance, has minor variations of its basic premise in countries like Armenia. In it, Nourie Hadig (Snow White) is involved in a taut tale involving cursed boys, gypsies, and exploding saber dashees (Turkish for “stone of patience”). However, it still uses the same basic premise of an older woman’s jealousy and the mistreating of a beautiful young girl.

Snow White is only of one many such tales that are remarkably consistent across cultures. The themes and basic narratives of fairy tales are so similar between different nations and regions that there are a number of international classification systems used to identify the different types. One of the most commonly used systems is the Aarne–Thompson–Uther classification system, developed in 2004. This index groups folk tales by motif and/or tale type, revealing the limited amount of themes used worldwide (Fig. 5.8.2).

From animal tales to forced marriage contracts, most folk tales seek to teach values and principles to the unsuspecting audience, be them altruism, prudence, or persistence. These values remain almost universal, and partly this is due to their origin and our own as a species.

These are the values that cultures live by. As children, the examples in these stories inspire us to “do the right thing,” and to do what is “best” in the sense of a commonly accepted behavior in the social context from whence they sprang, and speak to the universal values that bind a common human past.

Fairy and folk tales (the distinction is often hard to pinpoint, even for experts) spring from an oral tradition that dates back over 5000 years. Their origin is enshrouded in the haziness of early history, when the Pan-European civilization was starting to expand to the outer ridges of Asia and Europe, taking with them tales that matured over time.

Because of their common origins and cultural contamination, the structure of the folk tale is an early predecessor to the dramatic arc. Greek theater used and popularized this narrative model, and these tales have a clear similarity in the following aspects:

• Story motif and arc: There is a dramatic progression towards a dénouement that usually occurs after a series of tests or crises the main character is subjected to;

• Structure: There is a balanced sequence of events (or acts) matching beginning, middle, and end, although this may be nonlinear in some narratives;

• Character development: The hero goes through a personal journey of self-fulfillment, revelation, and ultimately meeting its destiny.

This is a part of the audience’s expectations in the West. Most movies and fictional work incorporate this structure, from Star Wars to Iron Man. Without this tension or conflict, the story is often thought of as dull and lifeless, and fails to engage.

The basic template of a common story, or metanarrative, encompassing these three factors, has been engrained in our collective unconscious and systematically analyzed by psychologists and sociologists. The most famous work of this kind is arguably The Hero with a Thousand Faces, by Joseph Campbell. In it, Campbell basically argues that all stories have been told already, and generations keep retelling the same basic myth: from Jesus to Luke Skywalker, the common hero undergoes a journey of peril, confrontation, and ultimately victory.

This basic myth has been absorbed and reinterpreted by different cultures around the world. However, there are subtle differences in how a story is thought of around the world.

In the West, stories often revolve around the concept of conflict and tension. The structure of most stories is multistaged. Gustav Freytag, a German playwright, suggested that this three-part dramatic structure can be represented in the form of a pyramid:

• Beginning (Act I): The normal state of affairs is disrupted by a “problem” or an event, which becomes central to the story by the second-act.

• Middle (Act II): The main character is then forced to resolve the situation.

• Climax (Act III): Through a series of perils and difficulties, the hero meets its fate: either by accomplishing a personal or group victory by defeating opposing forces, or (in the case of a tragedy) by being left in a worse position than initially.

The three-act structure can be expanded and subverted, but the basic narrative model is consistent. Think of a classic tragedy like Romeo and Juliet, or a more modern narrative like Still Alice or Leaving Las Vegas. Although the main characters do not have a moment of triumph, the emotional journey they undertake reveals personal truths and the resilience of their own spirits. These tales have similar dramatic frameworks, as their stories are usually individual, with well-defined main characters, and the audience is asked to identify and empathize with them.

Christopher Booker, in his 2004 book The Seven Basic Plots: Why We Tell Stories, systematized the bulk of the plots used in Western tales as the following:

• Overcoming the monster: The main character is out to destroy an evil force, often equated with the hero’s journey. Examples: Star Wars, The Hunger Games, Dracula, War of the Worlds.

• Rags to riches: A protagonist that is poor or of lesser social standing improves its situation, usually learning the value of humility and self-awareness in the process. Examples: Cinderella, Great Expectations.

• The quest: The hero undertakes a journey and overcomes obstacles to reach a goal or retrieve an object. Examples: Iliad, The Lord of the Rings.

• Voyage and return: The character returns from a trip to a foreign land and in the process meets unfathomable dangers. The only reward is the return to the familiarity of its fabled home. Examples: Odyssey, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, The Wizard of Oz.

• Comedy: A genre often equated with romance, it is usually structured as a sequence of awkward mistakes and situations. It traditionally implies a social reframing of higher classes or morally superior characters, with an eventual cheerful denouement. Examples: Much Ado About Nothing, The Taming of the Shrew, Four Weddings and a Funeral, Pretty Woman.

• Tragedy: The main character’s flaws or haunting past prompt him or her to engage in a downward spiral that ultimately leads to self-destruction. There is usually a second and slightly removed character that acts as a proxy for the audience and pities the fate of the main character. Examples: The Great Gatsby, Hamlet, Breaking Bad.

• Rebirth: The main character undergoes a transformation, often after tragic events, which improves them in some way. Examples: The Snow Queen, A Christmas Carol, Christian Mythology.

All of these narrative models are innately Western, in that they have in common an easily identifiable main character, and emphasize the individual journey, even when the story has several characters. On the other hand, complex narratives like those designed by Kafka and James Joyce usually present decomposed and subverted versions of these styles.

On the other hand, Chinese, Japanese, and Korean tales have a very different narrative approach. One of the classic narrative structures, Kishōtenketsu (![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() , distinguishes itself by having a slightly different structure with four distinct moments:

, distinguishes itself by having a slightly different structure with four distinct moments:

• Introduction: The characters and story are set and established;

• Development: Relationships deepen, the first signs of change loom;

• Twist: A new character or a change of settings is introduced that seems to have no relation to the previous two stages;

• Reconciliation: Both the initial characters or setting and the twist are framed together and tie both strands together.

This type of narrative does not warrant a tension or conflict, either internal or external, as the core of the story. There might be confrontation, difficulties, and stand-offs, but the tale is more about the convergence of two distinct backdrops into one consistent ending. Kishōtenketsu is about the connections and relations of situations, rather than the one person who can make a difference.

Another distinctive aspect of traditional Japanese lore is the frequent reluctance to distinguish between good and evil. Characters are often portrayed in a struggle with the spirit world, represented by nature’s elements and various mythical creatures. The narrative is ultimately one of surprise and self-identification, rather than a cautionary tale or one that can be taken as an example.

Outside of the odd landmark novel like or the quirky action/horror movie, Asian narratives are seldom popular in the East. However, Western-style narratives are becoming more popular in China and Japan, and the model is very familiar nowadays thanks to radio, television, and online sources.

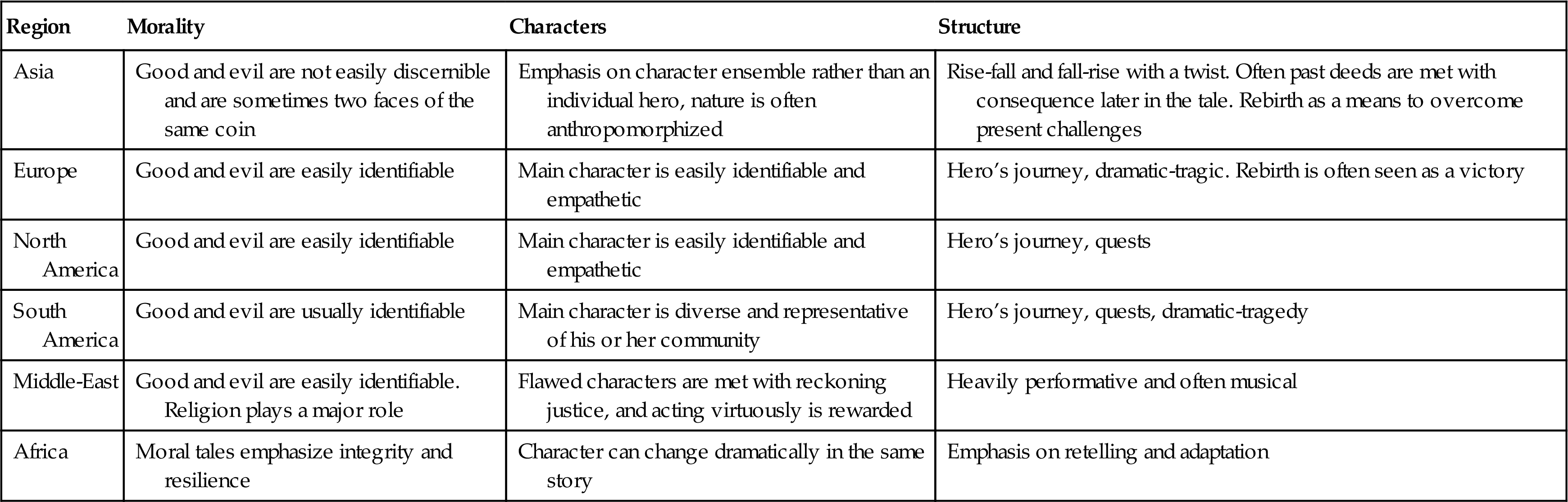

| Region | Morality | Characters | Structure |

| Asia | Good and evil are not easily discernible and are sometimes two faces of the same coin | Emphasis on character ensemble rather than an individual hero, nature is often anthropomorphized | Rise-fall and fall-rise with a twist. Often past deeds are met with consequence later in the tale. Rebirth as a means to overcome present challenges |

| Europe | Good and evil are easily identifiable | Main character is easily identifiable and empathetic | Hero’s journey, dramatic-tragic. Rebirth is often seen as a victory |

| North America | Good and evil are easily identifiable | Main character is easily identifiable and empathetic | Hero’s journey, quests |

| South America | Good and evil are usually identifiable | Main character is diverse and representative of his or her community | Hero’s journey, quests, dramatic-tragedy |

| Middle-East | Good and evil are easily identifiable. Religion plays a major role | Flawed characters are met with reckoning justice, and acting virtuously is rewarded | Heavily performative and often musical |

| Africa | Moral tales emphasize integrity and resilience | Character can change dramatically in the same story | Emphasis on retelling and adaptation |

This style of storytelling is inevitably different from African and Middle-Eastern storytelling models. African storytelling is similar to the Western model in that its style is primarily educational and moral, but adds a complex layer of performance. Proverbs and stories based on oral tales originated centuries ago are common, and play a more dominant role in modern storytelling than what is common in the Europe–US narratives. Old truths live on and play an active role in everyday life. However, similarly, rarely is there a concept of “authoritative” versions: the tale lives on and is reinterpreted with each new telling.

As with Indian myths, Central Asian storytelling is often laced with music. Unlike African tales, most stories are heavily prescribed and have a limited room for improvisation or adaptation. The most traditional form of storytelling is the dastan, a type of Turkic epic that constitutes a complex part of Central Asian literature and influenced literature and folk tales in the region. It is often set in verse and celebrates battles and victories of the local peoples against invaders.

Middle-Eastern storytelling is often characterized by a layered and complex plotline, and may employ different registers and genres in the same tale. It is not unusual that a single tale includes multiple plotlines and incorporates elements of tragedy, comedy, and satire.