Strategy, value chains, business initiatives, and competitive advantage

Keywords

Balanced Scorecard; Business initiative; Business models; Goal; Key performance indicator (KPI); Positioning strategies; Strategic themes; Strategy; Strategy maps; Value propositions

In this chapter we want to discuss some of the ways that executives think about their organizations. It is important that process managers and practitioners understand this because, ultimately, they will be expected to develop business architectures and processes that support the strategies, goals, and initiatives developed by executives. As in so many areas of business, different theorists and different organizations use these terms in different ways. Here are our definitions, and we will try to use these terms consistently throughout the remainder of this book.

- • Goal—A general statement of something executives want to gather data about, and a vector suggesting how they hope the data will trend. For example: increase profits.

- • Objective—We can contrast a goal, like Increase Profits, with an objective, which might be: increase profits by 3% by the end of this year. Objectives are more specific than goals and not only include a unit of measure and a vector, but also include a specific measurable outcome and a timeframe.

- • Strategy—A general statement of how we propose to achieve our goals. For example: our strategy will be to offer the best products at a premium price.

- • Business model—A business model is another way to speak about how an organization will apply a strategy (usually providing more detail about how the strategy will change the organization or what implementation of the strategy will involve). For some a business model simply describes how a company will operate. For others a business model involves a spreadsheet that demonstrates how an organization will apply labor and technology to generate profits over the course of time.

- • Business initiatives—A business initiative is a statement of an outcome executives want the organization to accomplish in the near future. For example: all divisions will install enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems in the coming year. Or, each unit will reduce its expenses by 3% in the coming year. Initiatives can sound very much like objectives, except that they tend to focus on what business units or people will do, rather than results that will be achieved.

- • Key performance indicators (KPIs)—A KPI is a high-level measurement that organization executives intend to monitor to ensure that related goals, strategies, or initiatives are achieved. For example: profits, completed ERP installations.

- • Measures—Just as goals can be contrasted with objectives that are more specific, KPIs can be contrasted with measures, which define not only what is to be measured, but also define the specific, desired outcome and the timeframe. Thus a measure might be division profits for second quarter or departments that have completed ERP installations as of the end of the first quarter.

We will discuss all these terms in more detail in other chapters, but these definitions should suffice for a discussion of the approaches executives employ in setting goals and strategies.

The concept of a business strategy has been around for decades, and the models and processes used to develop a company strategy are taught at every business school. A business strategy defines how a company will compete, what its goals will be, and what policies it will support to achieve those goals. Put a different way, a company’s strategy describes how it will create value for its customers, its shareholders, and its other stakeholders. Developing and updating a company’s business strategy is one of the key responsibilities of a company’s executive officers.

We start our discussion of enterprise-level process concerns with a look at how business people talk about business strategy. This will establish a number of the terms we will need for our subsequent discussion of processes. To develop a business strategy, senior executives need to consider the strengths and weaknesses of their own company and its competitors. They also need to consider trends, threats, and opportunities within the industry in which they compete, as well as in the broader social, political, technological, and economic environments in which the company operates.

There are different schools of business strategy. Some advocate a formal process that approaches strategic analysis very systematically, while others support less formal processes. A few argue that the world is changing so fast that companies must depend on the instincts of their senior executives and evolve new positions on the fly in order to move rapidly.

The formal approach to business strategy analysis and development is often associated with the Harvard Business School. In this brief summary we begin by describing a formal approach that is derived from Harvard professor Michael E. Porter’s book, Competitive Strategy. Published in 1980 and now in its 60th printing, Competitive Strategy has been the bestselling strategy textbook throughout the past two decades. Porter’s approach is well known, and it will allow us to examine some models that are well established among those familiar with strategic management literature.

Defining a Strategy

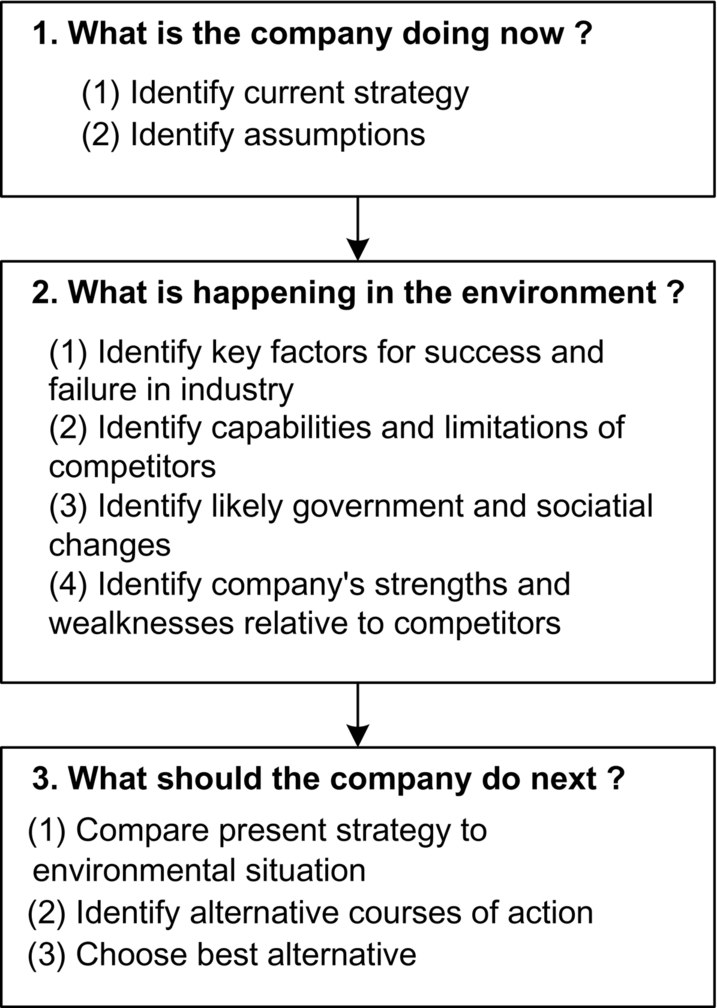

Porter defines business strategy as “a broad formula for how a business is going to compete, what its goals should be, and what policies will be needed to carry out these goals.” Figure 2.1 provides an overview of the three-phase process that Porter recommends for strategy formation.

- • Phase 1: Determine the current position of the company. The formal strategy process begins with a definition of where the company is now—what its current strategy is—and the assumptions that the company managers commonly make about the company’s current position, strengths and weaknesses, competitors, and industry trends. Most large companies have a formal strategy and have already gone through this exercise several times. Indeed, most large companies have a strategy committee that constantly monitors the company’s strategy.

- • Phase 2: Determine what is happening in the environment. In the second phase of Porter’s strategy process (the middle box in Figure 2.1) the team developing the strategy considers what is happening in the environment. In effect, the team ignores the assumptions the company makes at the moment and gathers intelligence that will allow them to formulate a current statement of environmental constraints and opportunities facing all the companies in their industry. The team examines trends in the industry the company is in and reviews the capabilities and limitations of competitors. It also reviews likely changes in society and government policy that might affect the business. When the team has finished its current review, it reconsiders the company’s strengths and weaknesses, relative to the current environmental conditions.

- • Phase 3: Determine a new strategy for the company. During the third phase the strategy team compares the company’s existing strategy with the latest analysis of what is happening in the environment. The team generates a number of scenarios or alternate courses of action that the company could pursue. In effect, the company imagines a number of situations the company could find itself in a few months or years hence and works backward to imagine what policies, technologies, and organizational changes would be required during the intermediate period to reach each situation. Finally, the company’s strategy committee, working with the company’s executive committee, selects one alternative and begins to make the changes necessary to implement the company’s new strategy.

Porter offers many qualifications about the need for constant review and the necessity for change and flexibility, but overall Porter’s model was designed for the relatively calmer business environment that existed 20 years ago. Given the constant pressures to change and innovate that we’ve all experienced during the last three decades, it may be hard to think of the 1980s as a calm period, but everything really is relative. When you contrast the way companies approached strategy development just 10 years ago with the kinds of changes occurring today, as companies scramble to adjust to the world of the Internet and the Cloud, the 1980s were relatively sedate. Perhaps the best way to illustrate this is to look at Porter’s general model of competition.

Porter’s Model of Competition

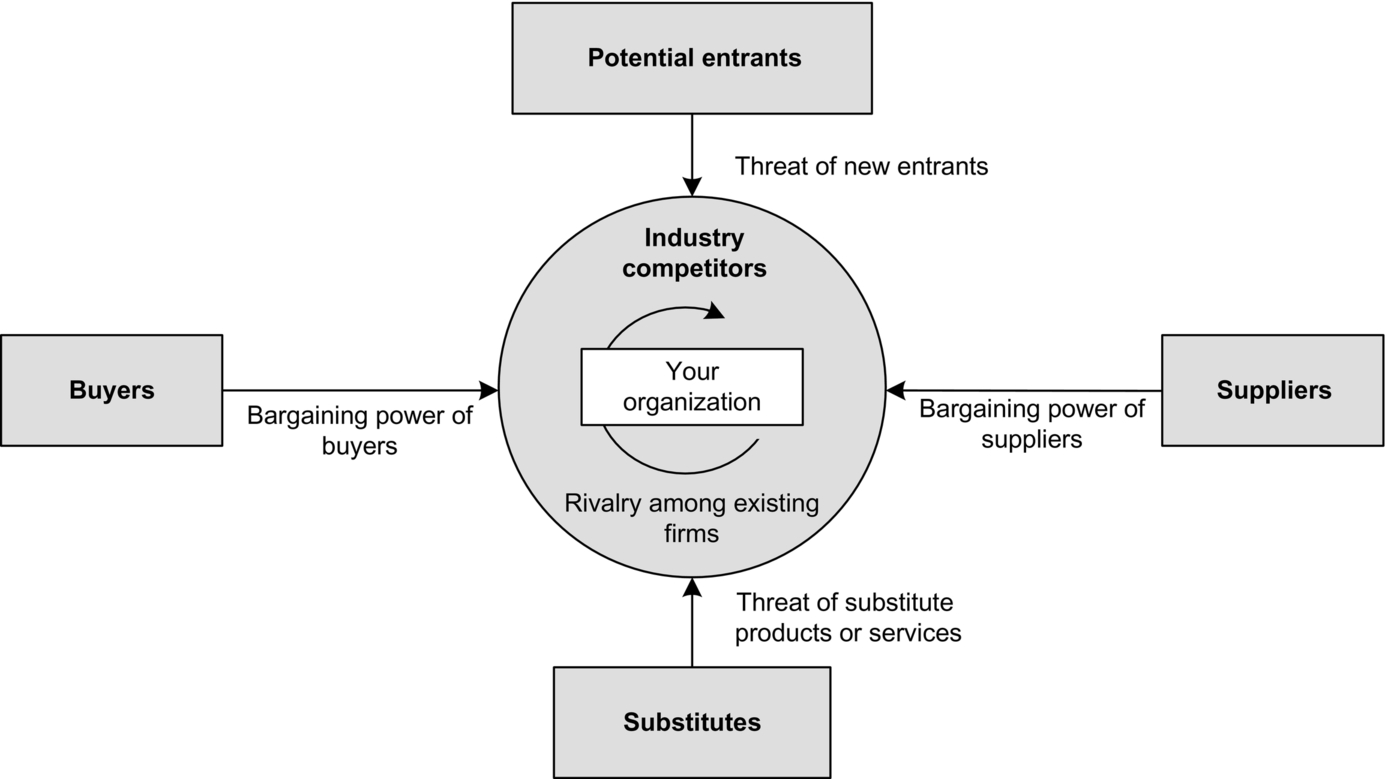

Porter emphasizes that “the essence of formulating competitive strategy is relating a company to its environment.” One of the best-known diagrams in Porter’s Competitive Strategy is the one we have illustrated in Figure 2.2. Porter’s diagram, which pulls together lots of information about how executives conceptualize the competition when they formulate strategy, is popularly referred to as the “five forces model.”

Porter identifies five changes in the competitive environment that can force a company to adjust its business strategy. The heart of business competition, of course, is the set of rival companies that comprise an industry. The company and its competitors are represented by the circle at the center of Figure 2.2.

- • Industry competitors. As rival companies make moves the company must respond. Similarly, the company may opt to make changes itself to place its rivals at a disadvantage. Porter spends several chapters analyzing the ways companies compete within an industry, and we’ll return to that in a moment.

Beyond the rivalry between the companies that make up the industry, there are changes in the environment that can potentially affect all the companies in an industry. Porter classifies these changes into four groups: (1) buyers, (2) suppliers, (3) potential new companies that might enter the field, and (4) the threat that new products or services will become desirable substitutes for the company’s existing products and services. - • Buyers. Buyers or customers will tend to want to acquire the company’s products or services as inexpensively as possible. Some factors give the seller an advantage: if the product is scarce, if the company is the only source of the product or the only local source of the product, or if the company is already selling the product more cheaply than its competitors, the seller will tend to have better control of its prices. The inverse of factors like these gives the customer more bargaining power and tends to force the company to reduce its prices. If there are lots of suppliers competing with each other, or if it’s easy for customers to shop around, prices will tend to fall.

- • Suppliers. In a similar way, suppliers would always like to sell their products or services for a higher price. If the suppliers are the only source of a needed product, if they can deliver it more quickly than their rivals, or if there is lots of demand for a relatively scarce product, then suppliers will tend to have more bargaining power and will increase their prices. Conversely, if the supplier’s product is widely available or available more cheaply from someone else, the company (buyer) will tend to have the upper hand and will try to force the supplier’s price down.

- • Substitutes. Companies in every industry also need to watch to see that no products or services become available that might function as substitutes for the products or services the company sells. At a minimum a substitute product can drive down the company’s prices. In the worst case a new product can render the company’s current products obsolete. The manufacturers of buggy whips were driven into bankruptcy when internal combustion automobiles replaced horse-drawn carriages in the early years of the 20th century. Similarly, the availability of plastic products has forced the manufacturers of metal, glass, paper, and wood products to reposition their products in various ways.

- • Potential entrants. Finally, there is the threat that new companies will enter an industry and thereby increase the competition. More companies pursuing the same customers and trying to purchase the same raw materials tend to give both the suppliers and the customers more bargaining power, driving up the cost of goods and lowering each company’s profit margins.

Historically, there are a number of factors that tend to function as barriers to the entry of new firms. If success in a given industry requires a large capital investment, then potential entrants will have to have a lot of money before they can consider trying to enter the industry. The capital investment could take different forms. In some cases a new entrant might need to build large factories and buy expensive machinery. The cost of setting up a new computer chip plant, for example, runs to billions of dollars, and only a very large company could consider entering the chip-manufacturing field. In other cases the existing companies in an industry may spend huge amounts on advertising and have well-known brand names. Any new company would be forced to spend at least as much on advertising to even get its product noticed. Similarly, access to established distribution channels, proprietary knowledge possessed by existing firms, or government policies can all serve as barriers to new companies that might otherwise consider entering an established industry.

Until recently the barriers to entry in most mature industries were so great that the leading firms in each industry had a secure hold on their positions and new entries were very rare. In the past three decades the growing move toward globalization has resulted in growing competition among firms that were formerly isolated by geography. Thus, prior to the 1960s the three large auto companies in the United States completely controlled the US auto market. Starting in the 1970s, and growing throughout the next two decades, foreign auto companies began to compete for US buyers and US auto companies began to compete for foreign auto buyers. By the mid-1980s a US consumer could choose between cars sold by over a dozen firms. The late 1990s witnessed a sharp contraction in the auto market, as the largest automakers began to acquire their rivals and reduced the number of independent auto companies in the market. Key to understanding this whole process, however, is to understand that these auto companies were more or less equivalent in size and had always been potential rivals, except that they were functioning in geographically isolated markets. As companies became more international, geography stopped functioning as a barrier to entry, and these companies found themselves competing with each other. They all had similar strategies, and the most successful have gradually reduced the competition by acquiring their less successful rivals. In other words, globalization created challenges, but it did not radically change the basic business strategies that were applied by the various firms engaged in international competition.

In effect, when a strategy team studies the environment, it surveys all of these factors. They check to see what competitors are doing, if potential new companies seem likely to enter the field, or if substitute products are likely to be offered. And they check on factors that might change the future bargaining power that buyers or sellers are likely to exert.

Industries, Products, and Value Propositions

Obviously Porter’s model assumes that the companies in the circle in the middle of Figure 2.2 have a good idea of the scope of the industry they are in and the products and services that define the industry. Companies are sometimes surprised when they find that the nature of the industry has changed and that companies that were not formerly their competitors are suddenly taking away their customers. When this happens, it usually occurs because the managers at a company were thinking too narrowly or too concretely about what it is that their company was selling.

To avoid this trap, sophisticated managers need to think more abstractly about what products and services their industry provides. A “value proposition” refers to the value that a product or service provides to customers. Managers should always strive to be sure that they know what business (or industry) their company is really in. That’s done by being sure they know what value their company is providing to its customers.

Thus, for example, a bookseller might think he or she is in the business of providing customers with books. In fact, however, the bookseller is probably in the business of providing customers with information or entertainment. Once this is recognized, then it becomes obvious that a bookseller’s rivals are not only other book stores, but magazine stores, TV, and the Web. In other words, a company’s rivals aren’t simply the other companies that manufacture similar products, but all those who provide the same general value to customers. Clearly Rupert Murdoch realizes this. He has gradually evolved from being a newspaper publisher to managing a news and entertainment conglomerate that makes movies, owns TV channels and TV satellites, and sells books. His various companies are constantly expanding their interconnections to offer new types of value to their customers. Thus, Murdoch’s TV companies and newspapers promote the books he publishes. Later, the books are made into movies that are shown on his TV channels and once again promoted by his newspapers.

As customers increasingly decide they like reading texts on automated book readers, like a Kindle or iPad, companies that think of themselves as booksellers are forced to reconsider their strategies. In this situation it will be obvious that the real value being provided is information and that the information could be downloaded from a computer just as well as printed in a book format. Many magazines are already producing online versions that allow customers to read articles on the Web or download articles in electronic form. Record and CD vendors are currently struggling with a version of this problem as copies of songs are exchanged over the Internet. In effect, one needs to understand that it’s the song that has the value, and not the record or CD on which it’s placed. The Web and a computer become a substitute for a CD if they can function as effective media for transmitting and playing the song to the customer.

Good strategists must always work to be sure they really understand what customer needs they are satisfying. Strategists must know what value they provide customers before they can truly understand what business they are really in and who their potential rivals are. A good strategy is focused on providing value to customers, not narrowly defined in terms of a specific product or service.

In some cases, of course, the same product may provide different value to different customers. The same car, for example, might simply be a way of getting around for one group of customers, but a status item for another set of customers.

In spite of the need to focus on providing value to customers, historically, in designing their strategies most companies begin with an analysis of their core competencies. In other words, they begin by focusing on the products or services they currently produce. They move from products to ways of specializing them and then to sales channels until they finally reach their various targeted groups of customers. Most e-business strategists suggest that companies approach their analysis in reverse. The new importance of the customer and the new ways that products can be configured for the Web suggest that companies should begin by considering what Web customers like and what they will buy over the Web, and then progress to what product the company might offer that would satisfy the new web customers. This approach, of course, results in an increasingly dynamic business environment.

Strategies for Competing

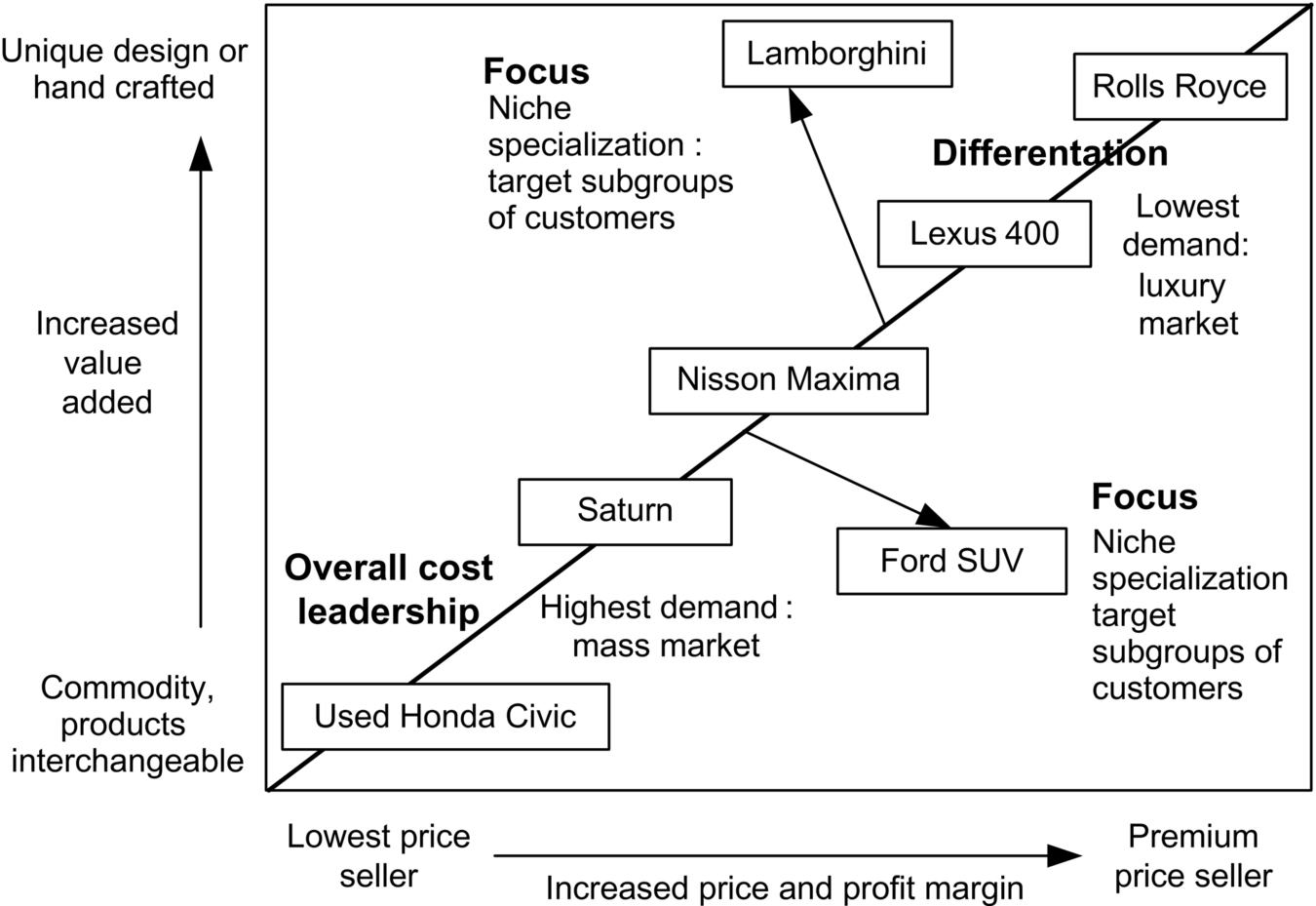

Earlier, we mentioned that Porter places a lot of emphasis on the ways existing companies can compete within an existing industry. In his 1980 book, Competitive Strategy, Porter described competition in most traditional industries as following one of three generic strategies: (1) cost leadership, (2) differentiation, or (3) niche specialization.

- • Cost leadership. The cost leader is the company that can offer the product at the cheapest price. In most industries price can be driven down by economies of scale, by the control of suppliers and channels, and by experience that allows a company to do things more efficiently. In most industries large companies dominate the manufacture of products in huge volume and sell them more cheaply than their smaller rivals.

- • Differentiation. If a company can’t sell its products for the cheapest price an alternative is to offer better or more desirable products. Customers are often willing to pay a premium for a better product, and this allows companies specializing in producing a better product to compete with those selling a cheaper but less desirable product. Companies usually make better products by using more expensive materials, relying on superior craftsmanship, creating a unique design, or tailoring the design of the product in various ways.

- • Niche specialization. Niche specialists focus on specific buyers, specific segments of the market, or buyers in particular geographical markets and often offer only a subset of the products typically sold in the industry. In effect, they represent an extreme version of differentiation, and they can charge a premium for their products, since the products have special features beneficial to the consumers in the niche.

Figure 2.3 provides an overview of one way strategists think of positioning and specialization. As a broad generalization, if the product is a commodity it will sell near its manufacturing cost, with little profit for the seller. Companies that want to sell commodities usually need to sell large volumes.

The classic example of a company that achieved cost leadership in an industry was the Ford Motor Company. The founder, Henry Ford, created a mass market for automobiles by driving the price of a car down to the point where the average person could afford one. To do this, Ford limited the product to one model in one color and set up a production line to produce large numbers of cars very efficiently. In the early years of the 20th century Ford completely dominated auto production in the United States.

As the US economy grew after World War I, however, General Motors was able to pull ahead of Ford, not by producing cars as cheaply, but by producing cars that were nearly as cheap and that offered a variety of features that differentiated them. Thus, GM offered several different models in a variety of colors with a variety of optional extras. Despite selling slightly more expensive cars, GM gradually gained market share from Ford because consumers were willing to pay more to get cars in preferred colors and styles.

Examples of niche specialists in the automobile industry are companies that manufacture only taxi cabs or limousines.

Porter’s Theory of Competitive Advantage

Michael Porter’s first book, Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors, is the one in which he analyzed the various sources of environmental threats and opportunities and described how companies could position themselves in the marketplace. Porter’s second book, Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance, was published in 1985. Competitive Advantage extended Porter’s basic ideas on strategy in several important ways. For our purposes we will focus on his ideas about value chains, the sources of competitive advantage, and the role that business processes play in establishing and maintaining competitive advantage.

We’ve already encountered the idea of a value chain in the Introduction. Figure 2.2 illustrates Porter’s generic value chain diagram.

Porter introduced the idea of the value chain to emphasize that companies ought to think of processes as complete entities that begin with new product development and customer orders and end with satisfied customers. To ignore processes or to think of processes as things that occur within departmental silos is simply a formula for creating a suboptimized company. Porter suggested that company managers should conceptualize large-scale processes, which he termed value chains, as entities that include every activity involved in adding value to a product or service sold by the company.

We’ve used the terms value proposition and value chain several times now, so we should probably offer a definition. The term value, as it is used in any of these phrases, refers to value that a customer perceives and is willing to pay for. The idea of the value chain is that each activity in the chain or sequence adds some value to the final product. It’s assumed that if you asked the customer about each of the steps the customer would agree that the step added something to the value of the product. A value proposition describes in general terms a product or service that the customer is willing to pay for.

It’s a little more complex, of course, because everyone agrees that there are some activities or steps that don’t add value directly, but facilitate adding value. These are often called value-enabling activities. Thus, acquiring the parts that will later be used to assemble a product is a value-enabling activity. The key reason to focus on value, however, is ultimately to identify activities that are nonvalue-adding activities. These are activities that have been incorporated into a process, for one reason or another, that do not or no longer add any value to the final product. Nonvalue-adding activities should be eliminated. We’ll discuss all this in later chapters when we focus on analyzing processes.

Figure 2.2 emphasizes that many individual subprocesses must be combined to create a complete value chain. In effect, every process, subprocess, or activity that contributes to the cost of producing a given line of products must be combined. Once all the costs are combined and subtracted from gross income from the sale of the products, one derives the profit margin associated with the product line. Porter discriminates between primary processes or activities, and includes inbound logistics, operations, outbound logistics, marketing and sales, and service. He also includes support processes or activities, including procurement, technology development, HR management, and firm infrastructure, which includes finance and senior management activities. Porter’s use of the term value chain is similar to Hammer’s use of core process. Many companies use the term process to refer to much more specific sets of activities. For example, one might refer to the Marketing and Sales process, the Order Fulfillment process, or even the Customer Relationship Management process. In this book, when we want to speak of comprehensive, large-scale processes we’ll use the term value chain. In general, when we use the term process we will be referring to some more specific set of activities.

Although it doesn’t stand out in Figure 2.2, if we represented each of the functions shown in the figure as boxes and connected them with arrows, we could see how a series of functions results in a product or service delivered to a customer. If we had such a representation we could also ask which functions added value to the process as it passed through that box. The term value chain was originally chosen to suggest that the chain was made up of a series of activities that added value to products the company sold. Some activities would take raw materials and turn them into an assembled mechanism that sold for considerably more than the raw materials cost. That additional value would indicate the value added by the manufacturing process. Later, when we consider activity costing in more detail we will see how we can analyze value chains to determine which processes add value and which do not. One goal of many process redesign efforts is to eliminate or minimize the number of nonvalue-adding activities in a given process.

Having defined a value chain Porter went on to define competitive advantage and show how value chains were key to maintaining competitive advantage. Porter offered these two key definitions:

- • A strategy depends on defining a company position that the company can use to maintain a competitive advantage. A position simply describes the goals of the company and how it explains those goals to its customers.

- • A competitive advantage occurs when your company can make more profits selling its product or service than its competitors can. Rational managers seek to establish a long-term competitive advantage. This provides the best possible return over an extended period for the effort involved in creating a process and bringing a product or service to market. A company with a competitive advantage is not necessarily the largest company in its industry, but it makes its customers happy by selling a desirable product, and it makes its shareholders happy by producing excellent profits.

Thus, a company anywhere in Figure 2.3 could enjoy a competitive advantage. Porter cites the example of a small bank that tailors its services to the very wealthy and offers extraordinary service. It will fly its representatives, for example, to a client’s yacht anywhere in the world for a consultation. Compared with larger banks, this bank doesn’t have huge assets, but it achieves the highest profit margins in the banking industry and is likely to continue to do so for many years. Its ability to satisfy its niche customers gives it a competitive advantage.

Two fundamental variables determine a company’s profitability or the margin it can obtain from a given value chain. The first is the industry structure. That imposes broad constraints on what a company can offer and charge. The second is a competitive advantage that results from a strategy and a well-implemented value chain that lets a company outperform the average competitor in an industry over a sustained period of time.

A competitive advantage can be based on charging a premium because your product is more valuable, or it can result from selling your product or service for less than your competitors because your value chain is more efficient. The first approach relies on developing a good strategic position. The second advantage results from operational effectiveness.

As we use the terms a strategy, the positioning of a company, and a strategic position are synonyms. They all refer to how a company plans to function and present itself in a market.

In the 1990s many companies abandoned strategic positioning and focused almost entirely on operational effectiveness. Many companies speak of focusing on best practices. The assumption seems to be that a company can be successful if all of its practices are as good as or better than its competitors. The movement toward best practices has led to outsourcing and the use of comparison studies to determine the best practices for any given business process. Ultimately, Porter argues operational effectiveness can’t be sustained. In effect, it puts all the companies within each particular industry on a treadmill. Companies end up practicing what Porter terms “hypercompetition,” running faster and faster to improve their operations. Companies that have pursued this path have not only exhausted themselves, but they have watched their profit margins gradually shrink. When companies locked in hypercompetition have exhausted all other remedies they usually end up buying up their competitors to obtain some relief. That temporarily reduces the pressure to constantly improve operational efficiency, but it usually doesn’t help improve the profit margins.

The alternative is to define a strategy or position that your company can occupy where it can produce a superior product for a given set of customers. The product may be superior for a wide number of reasons. It may satisfy the very specific needs of customers ignored by other companies, it may provide features that other companies don’t provide, or it may be sold at a price other companies don’t choose to match. It may provide customers in a specific geographical area with products that are tailored to that area.

Porter argues that, ultimately, competitive advantage is sustained by the processes and activities of the company. Companies engaged in hypercompetition seek to perform each activity better than their competitors. Companies competing on the basis of strategic positioning achieve their advantage by performing different activities or organizing their activities in a different manner.

Put a different way, hypercompetitive companies position themselves in the same manner as their rivals and seek to offer the same products or services for less money. To achieve that goal they observe their rivals and seek to ensure that each of their processes and activities is as efficient as or more efficient than those of their rivals. Each time a rival introduces a new and more efficient activity the company studies it and then proceeds to modify its equivalent activity to match or better the rival’s innovation. In the course of this competition, since everyone introduces the same innovations, no one gains any sustainable advantage. At the same time margins keep getting reduced. This critique is especially telling when one considers the use of ERP applications, and we will consider this in detail later.

Companies relying on strategic positioning focus on defining a unique strategy. They may decide to focus only on wealthy customers and provide lots of service, or on customers that buy over the Internet. They may decide to offer the most robust product, or the least expensive product, with no frills. Once the company decides on its competitive position it translates that position into a set of goals and then lets those goals dictate the organization of its processes.

Porter remarks that a good position can often be defined by what the company decides not to do. It is only by focusing on a specific set of customers or products and services that one can establish a strong position. Once one decides to focus, management must constantly work to avoid the temptation to broaden that focus in an effort to acquire a few more customers.

If a company maintains a clear focus, however, then the company is in a position to tailor business processes and to refine how activities interact. Porter refers to the way in which processes and activities work together and reinforce one another as fit. He goes on to argue that a focus on fit makes it very hard for competitors to quickly match any efficiencies your company achieves. As fit is increased and processes are more and more tightly integrated, duplicating the efficiency of an activity demands that the competitor rearrange its whole process to duplicate not only the activity, but the whole process, and the relation of that process to related processes, and so on. Good fit is often a result of working to ensure that the handoffs between departments or functions are as efficient as possible.

In Porter’s studies companies that create and sustain competitive advantage do it because they have the discipline to choose a strategic position and then remain focused on it. More important, they gradually refine their business processes and the fit of their activities so that their efficiencies are very hard for competitors to duplicate. It is process integration or fit that provides the basis for long-term competitive advantage and that provides better margins without the need for knee-jerk efforts to copy the best practices of rivals.

Porter’s Strategic Themes

After writing Competitive Advantage in 1985, Porter shifted his focus to international competition. Then, in 1996 he returned to strategy concerns and wrote an article for the Harvard Business Review entitled “What Is Strategy?” which is still worth close study today. In addition to laying out his basic arguments against simple-minded operational efficiency and in favor of strategic positioning and the importance of integrated processes, Porter threw in the idea that strategists ought to create maps of activity systems to “show how a company’s strategic position is contained in a set of tailored activities designed to deliver it.”

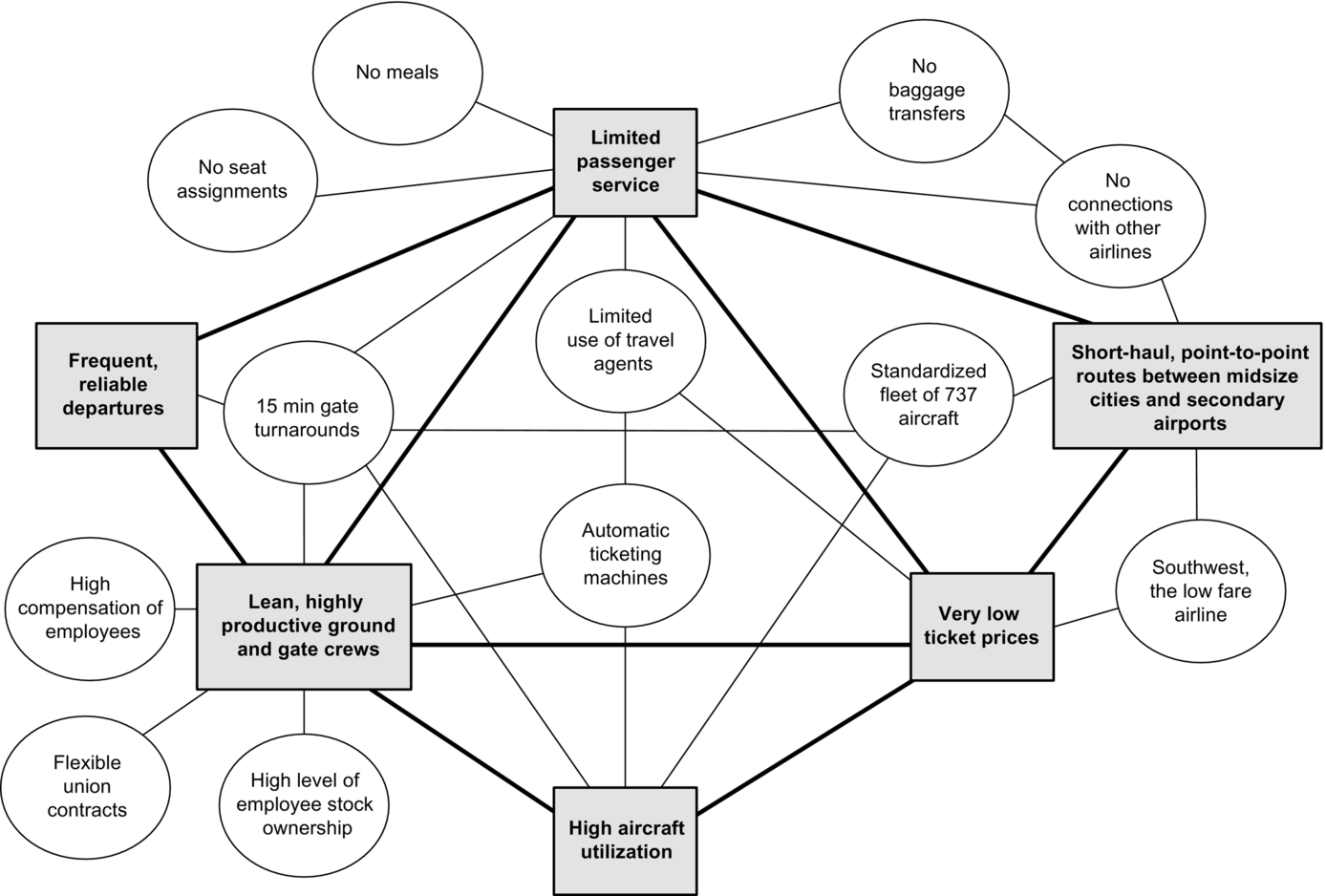

Porter suggested that strategists create network diagrams that show how a limited set of high-level strategic themes, and the activities associated with those themes, fit together to support a strategic position.

Porter provided several examples, and we’ve chosen one to illustrate this idea. In the early 1990s the executives at Southwest Airlines decided on a strategy that emphasized their being the dependable, low-cost airline. Figure 2.4 illustrates the activity-system map Porter provided for Southwest Airlines. The themes are in the rectangles and a set of activities are shown in circles. To charge low prices Southwest limited service. They only operated from secondary airports and didn’t assign seats or check baggage through to subsequent flights. They didn’t serve meals and attendants cleaned the planes between flights. By limiting service they were able to avoid activities that took time at check-in and were able to achieve faster turnaround and more frequent departures. Thus Southwest averaged more flights with the same aircraft between set locations than their rivals. By standardizing on a single aircraft they were also able to minimize maintenance costs and reduce training costs for maintenance crews.

Porter argued that too many companies talked strategy, but didn’t follow through on the implications of their strategy. They didn’t make the hard choices required to actually implement a specific strategy, and hence they didn’t create the highly integrated business processes that were very hard for rivals to duplicate. When companies do make the hard choices, as Southwest did, they find that the themes reinforce one another and the activities fit together to optimize the strategic position.

We’ve read lots of discussions of how business processes ought to support corporate strategies, and we certainly agree. Those who manage processes have an obligation to work to ensure that their process outcomes achieve corporate goals. Companies should work hard to align their process measures with corporate performance measures and to eliminate subprocesses that are counter to corporate goals. Different theorists have proposed different ways of aligning process activities and outcomes to goals. Most, however, assume that when executives announce goals, process people will simply create processes that will implement those goals.

Porter suggests something subtler. He suggests that smart senior executives think in terms of processes. In effect, one strategic goal of the organization should be to create value chains and processes that are unique and that fit together to give the organization a clear competitive advantage that is difficult for rivals to duplicate. He doesn’t suggest that senior executives should get into the design or redesign of specific business processes, but he does suggest that they think of the themes that will be required to implement their strategies, which are ultimately defined by products and customers, and think about the hard choices that will need to be made to ensure that the themes and key processes will fit together and be mutually reinforcing.

This isn’t an approach that many companies have taken. However, a process manager can use this concept to in effect “reverse-engineer” a company’s strategy. What are your value chains? What products do your value chains deliver to what customers? What is your positioning? What value propositions does your organization present to your customers when you advertise your products? Now develop an ideal activity-system map to define your company’s strategic positioning. Then compare it with your actual themes and activities. Do your major themes reinforce each other, or do they conflict? Think of a set of well-known activities that characterize one of your major processes. Do they support the themes that support your company’s strategic positioning?

This exercise has led more than one process manager to an “Ah ha! moment” and provided insight into why certain activities always seem to be in conflict with each other.

As Porter argues, creating a strategy is hard work. It requires thought and then it requires the discipline to follow through with the implications of a given strategic position. If it is done correctly, however, it creates business processes that are unique and well integrated and that lead to successes that are difficult for rivals to duplicate.

The alternative is for everyone to try to use the same best practices, keep copying each other’s innovations, and keep lowering profit margins till everyone faces bankruptcy. Given the alternative, senior management really ought to think about how strategy and process can work together to generate competitive advantage.

Treacy and Wiersema’s Positioning Strategies

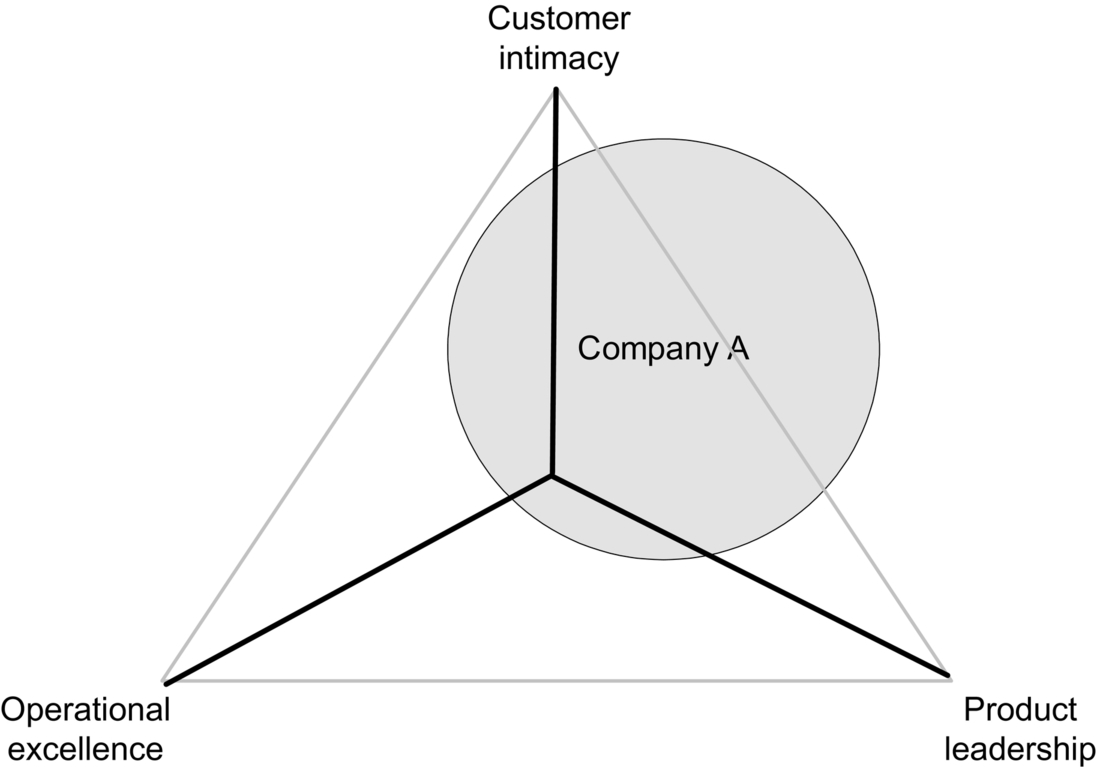

Two other strategy theorists, Michael Treacy and Fred Wiersema, generated a lot of discussion in the mid-1990s with their book, The Discipline of Market Leaders, which extended Porter’s ideas on generic strategies by focusing on customers and company cultures. Treacy and Wiersema suggest that there are three generic types of customers: (1) those whose primary value is high-performance products or services, (2) those whose primary value is personalized service, and (3) those who most value the lowest priced product. It’s easy to see how these might be mapped to Porter’s generic strategies, but they capture subtle differences. Like Porter, Treacy and Wiersema argue in favor of strategic differentiation and assert that “no company can succeed today by trying to be all things to all people. It must instead find the unique value that it alone can deliver to a chosen market.” The authors argue that companies can study their customers to determine what value proposition is most important to them. If they find that their customers are a mix of the three types the company needs to have the discipline to decide which group they most want to serve and focus their efforts accordingly. According to Treacy and Wiersema the three value positions that companies must choose between are:

- • Product leadership. These companies focus on innovation and performance leadership. They strive to turn new technologies into breakthrough products and focus on product life cycle management.

- • Customer intimacy. These companies focus on specialized, personal service. They strive to become partners with their customers. They focus on customer relationship management.

- • Operational excellence. These companies focus on having efficient operations to deliver the lowest priced product or service to their customers. They focus on their supply chain and distribution systems to reduce the costs of their products or services.

Just as one can conceive of three types of customers one can also imagine three types of company cultures. A company culture dominated by technologists is likely to focus on innovation and on product leadership. A company culture dominated by marketing or salespeople is more likely to focus on customer intimacy. A company culture dominated by financial people or by engineers is likely to focus on cutting costs and operational excellence.

Using this approach we can represent a market as a triangle, with the three value positions as three poles. Then we can draw circles to suggest the emphasis at any given organization. It is common to begin a discussion with executives and hear that they believe that their organization emphasizes all three of these positions equally. Invariably, however, as the discussion continues and you consider what performance measures the executives favor and review why decisions were taken, one of these positions emerges as the firm’s dominant orientation. In Figure 2.5 we show the basic triangle and then overlay a circle to suggest how we would represent a company that was primarily focused on customer intimacy and secondarily focused on product leadership.

Obviously, an MBA student learns a lot more about strategy. For our purposes, however, this brief overview should be sufficient. In essence, business managers are taught to evaluate a number of factors and arrive at a strategy that will be compatible with the company’s strengths and weaknesses and that will result in a reasonable profit. Historically, companies have developed a strategy and, once they succeeded, continued to rely on that strategy with only minor refinements for several years (refer to value nets in the Notes and References section).

The Balanced Scorecard Approach to Strategy

Robert S. Kaplan and David P. Norton are consultants who are closely related to the Harvard approach to strategy. Their influence began when they wrote an article titled “The Balanced Scorecard—Measures That Drive Performance,” which appeared in the January–February 1992 issue of the Harvard Business Review (HBR). Since then Kaplan and Norton have produced several other articles, a series of books, and a consulting company, all committed to elaborating the themes laid down in the initial “Balanced Scorecard” article.

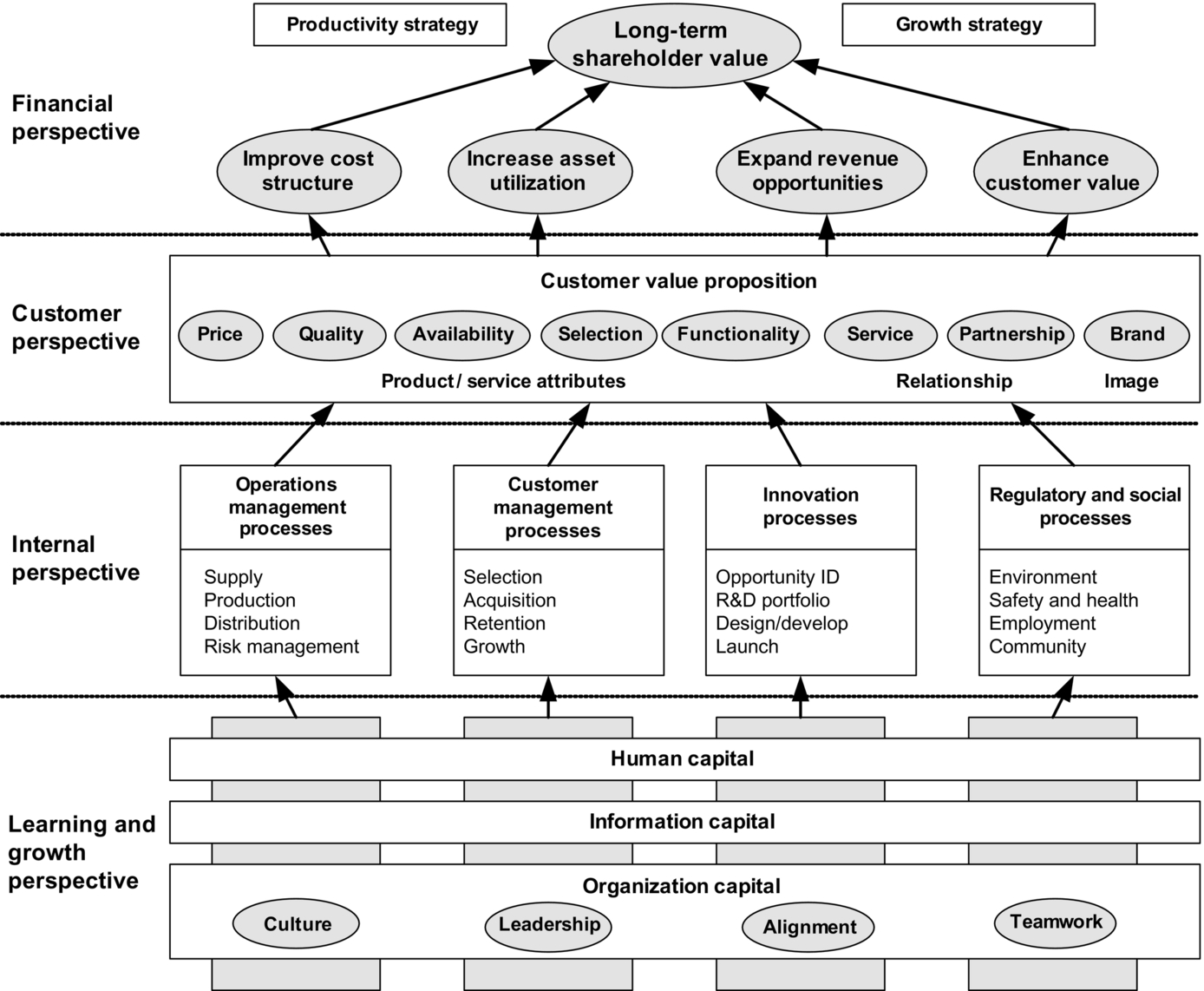

Kaplan and Norton published Strategy Maps, their third book, in 2004. In the Introduction they explained that their journey began in 1990 when they undertook a research project to explore ways that organizations measured performance. At the time they believed that knowledge-based assets—primarily employees and IT—were becoming increasingly important for companies’ competitive success, but that, despite that, most companies were still focused on measuring short-term financial performance. They also believed that “financial reporting systems provided no foundation for measuring and managing the value created by enhancing the capabilities of an organization’s intangible assets.” They argued that organizations tended to get what they measured. The result of this research effort was the Balanced Scorecard approach.

In essence, the Balanced Scorecard approach insists that management track four different types of measures: financial measures, customer measures, internal business (process) measures, and innovation and learning measures. Using the Balanced Scorecard approach an organization identifies corporate objectives within each of the four categories, and then aligns the management hierarchy by assigning each manager his or her own scorecard with more specific objectives in each of the four categories. Properly used the system focuses every manager on a balanced set of performance measures.

As soon as they published their now classic HBR article on the Balanced Scorecard methodology, Kaplan and Norton found that “while executives appreciated a more comprehensive new performance measurement system, they wanted to use their new system in a more powerful application than they had originally envisioned. The executives wanted to apply the system to solve the more important problem they faced—how to implement new strategies.”

In a series of articles and books, Kaplan and Norton have gradually refined a methodology that seeks to align a balanced set of measures to an organization’s strategy. They use a top-down method that emphasizes starting with the executive team and defining the organization’s strategic goals, and then passing those goals downward, using the Balanced Scorecard. They argue that success results from a strategy-focused organization, which, in turn, results from strategy maps and Balanced Scorecards.

Figure 2.6 provides an overview of a strategy map. Kaplan and Norton claim that this generic map reflects a generalization of their work with a large number of companies for whom they have developed specific strategy maps. Notice that the four sets of Balanced Scorecard measures are now arranged in a hierarchical fashion, with financial measures at the top, driven by customer measures, which are in turn the result of internal (process) measures, which in turn are supported by innovation and learning measures.

Their approach to strategy is explained in their September–October 2000 HBR article, “Having Trouble with Your Strategy? Then Map It.” The main thing the new book adds is hundreds of pages of examples, drawn from a wide variety of different organizations. For those that need examples this book is valuable, but for those who want theory the HBR article is a lot faster read.

Given our focus on process we looked rather carefully at the themes, which are, in essence, described as the internal perspective on the strategy map. Kaplan and Norton identify four themes that they go on to describe as “value-creating processes.” Scanning across the strategy map in Figure 2.6 the themes are operations management processes (supply chain management), customer management processes (customer relationship management), innovation processes (the design and development of new products and services), and regulatory and social processes. The latter is obviously a support process and doesn’t go with the other three, but would be better placed in their bottom area where they treat other support processes like HR and IT. Obviously, identifying these large-scale business processes is very much in the spirit of the times. Software vendors have organized around supply chain management and customer relationship management, and the Supply Chain Council is seeking to extend the SCOR model by adding a Design Chain model and a Customer Chain model.

The problem with any of these efforts is that, if they aren’t careful, they get lost in business processes, and lose the value chain that these business processes enable. Going further, what is missing in Strategy Maps is any sense of a value chain. One strategy map actually places an arrow behind the four themes or sets of processes in the internal perspective to suggest they somehow fit together to generate a product or service, but the idea isn’t developed. One could read Strategy Maps and come away with the idea that every company had a single strategy. No one seems to consider organizations with four different business units producing four different product lines. Perhaps we are to assume that strategy maps are only developed for lines of business and that everything shown in the internal perspective always refers to a single value chain. If that’s the case, it is not made explicit in Strategy Maps.

The fact that the process is on one level and the customer is on another is a further source of confusion. When one thinks of a value chain, there is a close relationship between the value chain, the product or service produced, and the customer. To isolate these into different levels may be convenient for those oriented to functional or departmental organizations, but it is a major source of confusion for those who are focused on processes.

Overall, the strategic perspective that Kaplan and Norton have developed is a step forward. Before Kaplan and Norton, most academic strategy courses were dominated by the thinking of Michael Porter, who began by emphasizing the “Five Forces Model” that suggested what external, environmental factors would change an organization’s competitive situation, and then focused on improving the value chain. By contrast, Kaplan and Norton have put a lot more emphasis on measures and alignment, which has certainly led to a more comprehensive approach to strategy. But their approach stops short of defining a truly process-oriented perspective.

We have described the 1990s as primarily concerned with horizontal alignment. Companies tried to eliminate operational and managerial problems that arose from silo thinking and see how a value chain linked all activities, from the supplier to the customer. Today, most companies seem to have moved on to vertical alignment and are trying to structure the way strategies align with measures and how processes align to the resources that implement them. In the shift we believe that something very valuable from the horizontal perspective has been lost. Kaplan and Norton put too much emphasis on vertical alignment and risk losing the insights that derive from focusing on value chains and horizontal alignment.

We’re sure that this is not the intent of Kaplan and Norton, and that they would argue that their process layer was designed to ensure that horizontal alignment was maintained. To us, however, the fact that they don’t mention value chains, and define their internal perspective themes in such an unsophisticated way, from the perspective of someone who is used to working on business process architectures, indicates that they have in fact failed to incorporate a sophisticated understanding of process in their methodology. We suspect that the problem is that they start at the top and ask senior executives to identify strategic objectives and then define measures associated with them. In our opinion this isn’t something that can be done in isolation. Value chains have their own logic, and the very act of defining a major process generates measures that must be incorporated into any measurement system.

Many large US companies have embraced some version of the Balanced Scorecard system, and have implemented one or another version of the methodology. Fewer, we suspect, have embraced strategy maps, but the number will probably grow since the maps are associated with the Scorecard system that is so popular. We think overall that this is a good thing. Most organizations need better tools to use in aligning strategies and managerial measures, and the Balanced Scorecard methodology forces people to think more clearly about the process and has in many cases resulted in much better managerial measurement systems.

For those engaged in developing business strategies, or developing corporate performance systems, the Kaplan and Norton HBR article is critical reading (refer to value nets notes in Notes and References section). Those who want to create process-centric organizations, however, will need to extend the Kaplan and Norton approach.

Business Models

In the past decade it has become popular to speak of strategic issues as business model issues. This terminology reflects an approach that entrepreneurs are more likely to use. In essence, a business model describes how a company plans to make money. Many business models are accompanied by statements that suggest how the company will position itself and use technology to generate a new product or service more efficiently or effectively than its competitors. Several management authors have written books describing the use of business models as a way of deriving a strategy and goals. Some are interesting and we cite the most popular in our references. Suffice to say, however, that business models are really just a spin on positioning and strategy, as described by Porter and others. If your company prefers to speak of business models, fine. The key from the perspective of the process practitioners is simply to ensure that you understand what your executives seek to achieve.

Business Initiatives

Finally, we come to business initiatives. Executives could conceivably define a strategy and announce goals and leave it at that, content to let middle managers organize their efforts accordingly. In most cases, however, the executive team will begin with strategies and goals, and then define a few high-priority initiatives. In essence, the executive team moves from wanting to improve the organization’s profit by 3% a year to mandating that each division will increase its specific profit by some given amount. Or, they will move from wanting to make customers happier to mandating that the sales process be redesigned in the course of the coming year. In most cases business initiatives are associated with KPIs, which are carefully monitored. In some cases managers’ bonuses depend on achieving the KPIs associated with key initiatives.

In the worst case the CEO launches a business initiative and division managers are so concerned with achieving the goals of the initiative that they ignore other operational concerns. An initiative to install ERP may, for example, be allowed to so disrupt regular business processes that sales decline as customers become frustrated with the resulting confusion. In the best case, on the other hand, business initiatives provide guidance to those doing process work and provide them with clear directions as to how to modify major business processes to keep them aligned with the strategic direction the organization is taking.

Summary

We urge readers to study Porter’s Competitive Advantage. In helping companies improve their business processes we have often encountered clients who worried about revising entire processes and suggested instead that standard ERP modules be employed. Some clients worried that we were advocating hypercompetition and urging them to begin revisions that their competitors would match, which would then require still another response on their part. It seemed to them it would be easier just to acquire standard modules that were already “best of breed” solutions. Undoubtedly this resulted from our failure to explain our position with sufficient clarity.

We do not advocate making processes efficient for their own sake, nor do we advocate that companies adopt a strategy based strictly on competitive efficiency. Instead, we advocate that companies take strategy seriously and define a unique position that they can occupy and in which they can prosper. We urge companies to analyze and design tightly integrated processes. Creating processes with superior fit is the goal. We try to help managers avoid arbitrarily maximizing the efficiency of specific activities at the expense of the process as a whole.

We certainly believe that companies should constantly scan for threats and opportunities. Moreover, we recommend that companies constantly adjust their strategies when they see opportunities or threats to their existing position. It’s important, however, that the position be well defined, and that adjustments be made to improve a well-defined position and not simply for their own sake. In the past few years we’ve watched dozens of companies adopt Internet technologies without a clear idea of how those technologies were going to enhance their corporate position. In effect, these companies threw themselves into an orgy of competitive efficiency, without a clear idea of how it would improve their profitability. We are usually strong advocates of the use of new technology, and especially new software technologies. Over the last few decades IT has been the major source of new products and services, a source of significant increases in productivity, and the most useful approach to improving process fit. We advocate the adoption of new technology, however, only when it contributes to an improvement in a clearly understood corporate position.

We also recommend that companies organize so that any changes in their strategic position or goals can be rapidly driven down through the levels of the organization and result in changes in business processes and activities. Changes in goals without follow-through are worthless. At the same time, as companies get better and better at rapidly driving changes down into processes, subprocesses, and activities, it’s important to minimize the disruptive effect of this activity. It’s important to focus on the changes that really need to be made and to avoid undertaking process redesign, automation, or improvement projects just to generate changes in the name of efficiency or a new technology that is unrelated to high-priority corporate goals.

To sum up: We don’t recommend that companies constantly change their strategic position to match a competitor’s latest initiatives. We don’t advocate creating a system that will simply increase hypercompetition. Instead, we believe that companies should seek positions that can lead to a long-term competitive advantage and that can only be accomplished as the result of a carefully conceived and focused corporate strategy. We argue for a system that can constantly tune and refine the fit of processes that are designed and integrated to achieve a well-defined, unique corporate position.

There will always be processes and activities that will be very similar from one company to another within a given industry. Similarly, within a large process there will always be subprocesses or activities that are similar from one company to another. In such cases we support a best-practices approach, using ERP modules or by outsourcing. Outsourcing, done with care, can help focus company managers on those core processes that your company actually relies on and eliminate the distraction of processes that add no value to your core business processes.

At the same time we are living in a time of rapid technological change. Companies that want to avoid obsolescence need to constantly evaluate new technologies to determine if they can be used to improve their product or service offerings. Thus, we accept that even well-focused companies that avoid hypercompetition will still find themselves faced with a steady need for adjustments in strategy and goals and for process improvement.

Ultimately, however, in this book we want to help managers think about how they can create unique core processes, change them in a systematic manner, and integrate them so that they can serve as the foundation for long-term competitive advantage.

Notes and References

Some strategists have recently argued that value chains are too rigid to model the changes that some companies must accommodate. They suggest an alternative that is sometimes termed value nets. IBM represents this approach with business component models (BCMs). (Recently some have begun to speak of this approach as a Capability Model.) This approach treats business processes as independent entities that can be combined in different ways to solve evolving challenges. Thus, the value nets approach abandons the idea of strategic integration, as Porter defines it, to achieve greater flexibility. The value nets and BCM models we have seen simply represent business processes, and don’t show how those processes are combined to generate products for customers. We suspect that this new approach will prove useful, but only if it can be combined with the value chain approach so that companies can see how they combine their business processes (or components) to achieve specific outcomes. Otherwise, the value nets approach will tend to suboptimize potential value chain integration and tend to reduce things to a set of best practices, with all the accompanying problems that Porter describes when he discusses operational effectiveness.

The best book that describes the value nets approach is David Bovet and Joseph Martha’s Value Nets (Wiley, 2000). The best paper on IBM’s variation on this approach is Component Business Models: Making Specialization Real by George Pohle, Peter Korsten, and Shanker Ramamurthy published by IBM Institute for Business Value (IBM Business Consulting Services). The paper is available on the IBM Developer website.

Porter, Michael E., Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors, The Free Press, 1980. The bestselling book on strategy throughout the past two decades. The must-read book for anyone interested in business strategy.

Porter, Michael E., Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance, The Free Press, 1985. This book focuses on the idea of competitive advantage and discusses how companies obtain and maintain it. One of the key techniques Porter stresses is an emphasis on value chains and creating integrated business processes that are difficult for competitors to duplicate.

Porter, Michael E., “What Is Strategy?,” Harvard Business Review, November–December 1996, Reprint No. 96608. This is a great summary of Porter’s Competitive Advantage. It’s available at http://www.amazon.com.

Porter, Michael E., “Strategy and the Internet,” Harvard Business Review, March 2001, Reprint No. R0103D. In this HBR article Porter applies his ideas on strategy and value chains to Internet companies with telling effect. An article everyone interested in e-business should study.

Treacy, Michael, and Fred Wiersema, The Discipline of Market Leaders: Choose Your Customers, Narrow Your Focus, and Dominate Your Market, Addison-Wesley, 1995. This book was extremely popular in the late 1990s and is still worthwhile. It provides some key insights into company cultures and how they affect positioning and the customers you should target.

Kaplan, Robert S., and David P. Norton, “Having Trouble with Your Strategy? Then Map It,” Harvard Business Review, September–October 2000. This article is available at http://www.amazon.com.

Kaplan, Robert S., and David P. Norton, Strategy Maps: Converting Intangible Assets into Tangible Outcomes, Harvard Business School Press, 2004. The Kaplan-Norton model often confuses the relationship between processes and measures, but it also provides lots of good insights. Read it for insights, but don’t take their specific approach too seriously, or your process focus will tend to get lost. Kaplan and Norton’s previous book on the Balanced Scorecard approach to strategy was The Strategy Focused Organization, which was published by Harvard Business School Press in 2001, and it’s also worth a read.

Osterwalder, Alexander, and Yves Pigneur, Business Model Generation, Wiley, 2010. This is a currently popular book on how one can use a business model to define your company’s position and goals.