Chapter 2. The Timeline

The right word may be effective, but no word was ever as effective as a rightly timed pause.

—Mark Twain

The Timeline panel is something like After Effects’ killer application within the overall app. More than any other feature, the Timeline panel extends the unique versatility of After Effects to a wide range of work, and differentiates it from less flexible node-based compositing applications. With the Timeline panel at the center of the compositing process, you can time elements and animations precisely while maintaining control of their appearance.

The Timeline panel is also a user-friendly part of the application that is full of hidden powers. By mastering its usage, you can streamline your workflow a great deal, setting the stage for more advanced work. One major subset of these hidden powers is the Timeline panel’s set of keyboard shortcuts and context menus. These are not extras to be investigated once you’re a veteran but small productivity enhancers that you can learn gradually as you go.

If this chapter’s information seems overwhelming on first read, I encourage you to revisit often so that specific tips can sink in once you’ve encountered the right context in which to use them.

Organization

The goal here isn’t to keep you organized but to get rid of everything you don’t need and put what you do need right at your fingertips.

Column Views

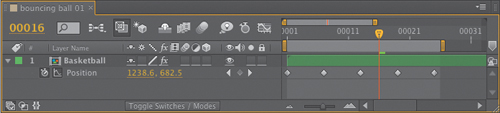

You can context-click on any column heading to see and toggle available columns in the Timeline panel, or you can start with the minimal setup shown in Figure 2.1 and then augment or change the setup with the following tools:

Figure 2.1. This most basic Timeline panel setup is close to optimal, especially if space is tight; it leaves everything you need within a single click, such as Toggle Switches/Modes. No matter how big a monitor, every artist tends to want more space for the keyframes and layers themselves.

• Lower-left icons ![]() : Most (but not quite all) of the extra data you need is available via the three toggles found at the lower left of the Timeline panel.

: Most (but not quite all) of the extra data you need is available via the three toggles found at the lower left of the Timeline panel.

• Layer switches ![]() and transfer controls

and transfer controls ![]() are the most used; if you have plenty of horizontal space, leave them both on, but the F4 key has toggled them since the days when 1280 × 960 was an artist-sized display.

are the most used; if you have plenty of horizontal space, leave them both on, but the F4 key has toggled them since the days when 1280 × 960 was an artist-sized display.

• Time Stretch ![]() toggles the space-hogging timing columns. The one thing I do with this huge set of controls is stretch time to either double speed or half speed (50% or 200% stretch, respectively), which I can do by context-clicking Time > Time Stretch.

toggles the space-hogging timing columns. The one thing I do with this huge set of controls is stretch time to either double speed or half speed (50% or 200% stretch, respectively), which I can do by context-clicking Time > Time Stretch.

Tip

To rename an item in After Effects, highlight it and press Enter (Return) instead of clicking and hovering.

• Layer/Source (Alt or Opt key toggles): What’s in a name? Nothing until you customize it; clear labels and color (see Tip) boost your workflow.

• Parent: This one is often on when you don’t need it and hidden when you do (see “Spatial Offsets” later in this chapter); use Ctrl+Shift+F4 (Cmd+Shift+F4) to show or hide it.

• I can’t see why you would disable AV Features/Keys; it takes effectively no space.

The game is to preserve horizontal space for keyframe data by keeping only the relevant controls visible.

Color Commentary

When dissecting something tricky, it can help to use

• solo layers to see what’s what ![]()

• locks for layers that should not be edited further ![]()

• shy layers to reduce the Timeline panel to only what’s needed ![]()

• color-coded layers and project items ![]()

• tags in the comments field

Tip

To change the visibility (rather than the solo state) of selected layers, choose Layer > Switches > Hide Other Video.

Solo layers make other layers that are not solo invisible. They allow you to temporarily isolate and examine a layer or set of layers, but you can also keep layers solo when rendering (whether you intend to or not).

Tip

I prefer to use solo switches only for previewing, and often set the Solo Switches menu to All Off in my default Render Settings to ensure I don’t leave them activated by accident.

It can make a heck of a lot of sense to lock (Ctrl+L/Cmd+L) layers that you don’t want “nudged” out of position, such as adjustment layers, track mattes, and background solids (but once they’re locked, you can’t adjust anything until you unlock them). If you’re a super-organized person, you can use layer locks effectively to check layers in and out, with the locked ones completed—for now.

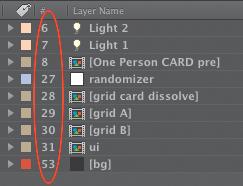

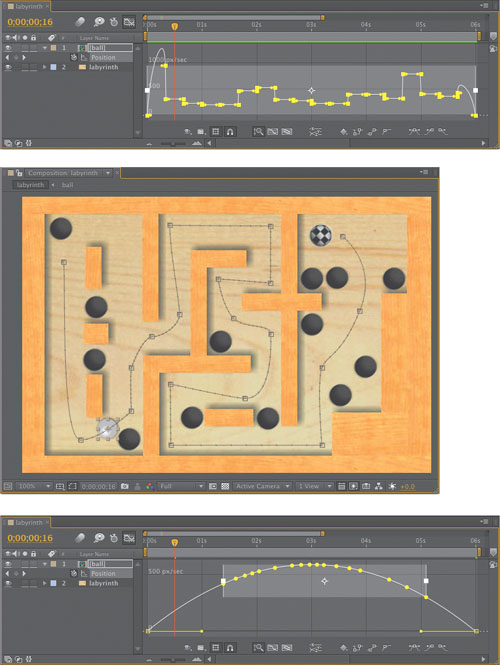

Shy layers are a fantastic shortcut in an often-cluttered Timeline panel. Layers set to Shy are hidden from the layer stack (once the Timeline panel’s own Shy toggle is enabled) but remain visible in the Composition viewer itself (Figure 2.2). Even if you keep the number of layers in a composition modest (as you must for effective visual effects compositing work—see Chapter 4 for more on how), a composition containing an imported 3D track from such software as SynthEyes or Boujou may arrive with hundreds of null layers. I tend to make these shy immediately, leaving only the camera and background plate ready for compositing.

Figure 2.2. Shy layers can greatly reduce clutter in the Timeline panel, but if they ever trick you, study the Index numbers; if any fall out of sequence, there’s a hidden shy layer.

Colors are automagically assigned to specific types of layers (like cameras, lights, and adjustment layers) according to Preferences > Label. I often apply unique colors to track matte layers so I remember not to move them. On someone else’s system, the colors may change according to local user preferences, although they will correspond overall.

Script

![]()

Comments are generally the least-used column in the Timeline panel, but that could change if more people start using a script called Zorro—The Layer Tagger by Lloyd Alvarez (http://aescripts.com/zorro-the-layer-tagger/). This script manages the process of adding tags to layers and using them to create selection sets.

Layer and composition markers can hold visible comments. You can add a layer marker for a given point in time with the asterisk (*) key on your numeric keypad, meaning you can add them while looping up a RAM preview in real time. Composition markers are added using Shift and the numbers atop your keyboard or using the asterisk key with nothing selected. I sometimes double-click them to add short notes.

Navigation and Shortcuts

Keyboard shortcuts are essential for working speedily and effortlessly in the Timeline panel.

Time Navigation

Many users—particularly editors, who know how essential they are—learn time navigation shortcuts right away. Others primarily drag the current time indicator, which quickly becomes tedious. See if there are any here you don’t already know:

• Home, End, PgUp, and PgDn correspond to moving to the first or last frame of the composition, one frame backward or one frame forward, respectively.

Tip

Laptop users in particular may prefer Ctrl+Left Arrow or Right Arrow (Cmd+Left Arrow or Right Arrow) as an alternative to PgUp and PgDn.

• Shift+PgUp and Shift+PgDn skip ten frames backward or forward, respectively.

• Shift+Home and Shift+End navigate to the work area In and Out points respectively, and the B and N keys set these points at the current time.

Notes

![]()

Don’t bother with punctuation when entering time values into a number field in After Effects. 1000 is ten seconds (10:00) when in Timecode mode.

• I and O keys navigate to the beginning and end frames of the layer.

• Press Alt+Shift+J (Opt+Shift+J) or click on the current time status at the upper left of the Timeline panel to navigate to a specific frame or timecode number. In this dialog, enter +47 to increment 47 frames or +–47 to decrement the same number; if you entered –47, that would navigate to a negative time position instead of offsetting by that number.

Layers Under Control

We were reviewing film-outs of shots in progress from The Day After Tomorrow at the Orphanage when my shot began to loop; it looked out a window at stragglers making their way across a snow-covered plaza and featured a beautiful matte painting by Mike Pangrazio. About two-thirds of the way through the shot came a subtle but sudden shift. At some point, the shot had been lengthened, and a layer of noise and dirt I had included at approximately 3% transparency (for the window itself) had remained shorter in a subcomposition. Gotcha!

Tip

The increment/decrement method, in which you can enter + 47 to increase a value by 47 or + -417 to reduce it by 417, operates in most number fields throughout After Effects (including Composition Settings).

After Effects allows you to time the entrance and exit of layers in a way that would be excruciating in other compositing applications that lack the notion of a layer start or end. To avoid the accompanying gotcha where a layer or composition comes up short, it’s wise to make elements way longer than you ever expect you’ll need—overengineer in subcompositions and trim in the master composition.

To add a layer beginning at a specific time, drag the element from the Project panel to the layer area of the Timeline panel; a second time indicator appears that moves with your cursor horizontally. This determines the layer’s start frame. If other layers are present and visible, you can also place the layer in order by dragging it between them.

Here are some other useful tips and shortcuts:

• Ctrl+/ (Cmd+/) adds a layer to the active composition.

• Ctrl+Alt+/ (Cmd+Opt+/) replaces the selected layer in a composition (as does Alt-dragging or Opt-dragging one element over another—note that this even works right in the Project panel and can be hugely useful).

Tip

The keyboard shortcut Ctrl+/ (Cmd+/) adds selected items as the top layer(s) of the active composition.

• J and K navigate to the previous or next visible keyframe, layer marker, or work area start or end, respectively.

• Ctrl+Alt+B (Cmd+Opt+B) sets the work area to the length of any selected layers. To reset the work area to the length of the composition, double-click it.

• Numeric keypad numbers select layers with that number.

• Ctrl+Up Arrow (Cmd+Up Arrow) selects the next layer up; Down Arrow works the same way.

Tip

To trim a composition’s duration to the current work area, choose Composition > Trim Comp to Work Area.

• Ctrl+] (Cmd+]) and Ctrl+[ (Cmd+[) move a layer up or down one level in the stack. Ctrl+Shift+] and Ctrl+Shift+[ move a layer to the top or bottom of the stack.

• Context-click > Invert Selection to invert the layers currently selected. (Locked layers are not selected, but shy layers are selected even if invisible.)

• Ctrl+D (Cmd+D) to duplicate any layer (or virtually any selected item).

• Ctrl+Shift+D (Cmd+Shift+D) splits a layer; the source ends and the duplicate continues from the current time.

• The bracket keys [ and ] move the In or Out points of selected layers to the current time. Add Alt (Opt) to set the current frame as the In or Out point, trimming the layer.

Notes

![]()

For those who care, a preference controls whether split layers are created above or below the source layer (Preferences > General > Create Split Layers Above Original Layer).

• The double-ended arrow icon over the end of a trimmed layer lets you slide it, preserving the In and Out points while translating the timing and layer markers (but not keyframes).

• Alt+PgUp or Alt+PgDn (Opt+PgUp or Opt+PgDn) nudges a layer and its keyframes forward or backward in time. Alt+Home or Alt+End (Opt+Home or Opt+End) moves the layer’s In point to the beginning of the composition, or the Out point to the end.

Tip

It can be annoying that the work area controls both preview and render frame ranges because the two are often used independent of one another. Dropping your work composition into a separate “Render Final” composition with the final work area set and locked avoids conflicts between working and final frame ranges and settings.

Timeline Panel Views

After Effects has a great keyframe workflow. These shortcuts will help you work with timing more quickly, accurately, and confidently:

• The semicolon (;) key toggles all the way in and out on the Timeline panel: single frame to all frames. The slider at the bottom of the Timeline panel ![]() zooms in and out more selectively.

zooms in and out more selectively.

• The scroll wheel moves you up and down the layer stack.

• Shift-scroll moves left and right in a zoomed Timeline panel view.

• Alt-scroll (Opt-scroll) zooms dynamically in and out of the Timeline panel, remaining focused around the cursor location.

Tip

Hold down the Shift key as you drag the current time indicator to snap the current time to composition or layer markers or visible keyframes.

• The backslash () key toggles between a Timeline panel and its Composition viewer, even if previously closed.

• The Comp Marker Bin ![]() contains markers you can drag out into the Timeline panel ruler. You can replace their sequential numbers with names.

contains markers you can drag out into the Timeline panel ruler. You can replace their sequential numbers with names.

• X scrolls the topmost selected layer to the top of the Timeline panel.

Keyframes and the Graph Editor

Transform controls live under every layer’s twirly arrow. There are keyboard shortcuts to each Transform property. For a standard 2D layer these are

• A for Anchor Point, the center pivot of the layer

• P for Position, by default the center of the composition

• S for Scale (in percent of source)

• R for Rotation (in revolutions and degrees)

• T for Opacity, or if it helps, “opaci-T” (which is not technically spatial transform data but is grouped here anyhow because it’s essential)

Once you’ve revealed one of these, hold down the Shift key to toggle another (or to hide another one already displayed). This keeps only what you need in front of you. A 3D layer reveals four individual properties under Rotation to allow full animation on all axes.

Add the Alt (Opt) to each of these one-letter shortcuts to add the first keyframe; once there’s one keyframe, any adjustments to that property at any other frame generate another keyframe automatically.

There are selection tools to correspond to perform Transform adjustments directly in the viewer:

• V activates the Selection tool, which also moves and scales in a view panel.

• Y switches to the Pan-Behind tool, which moves the anchor point.

• W is for “wotate”—it adjusts Rotation. Quite the sense of humor on that After Effects team.

Once you adjust with any of these tools, an Add Keyframe option for the corresponding property appears under the Animation menu, so you can set the first keyframe without touching the Timeline panel at all.

Graph Editor

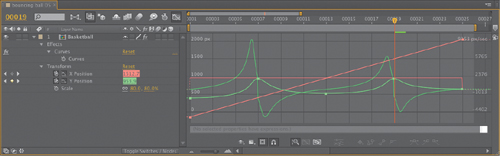

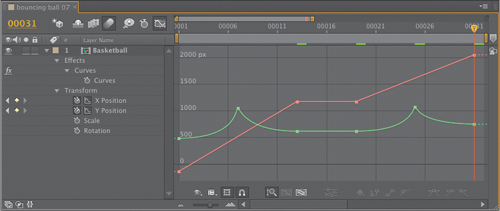

The project 02_bouncing_ball.aep in the accompanying disc’s examples folder contains a simple animation, bouncing ball 2d, which can be created from scratch; you can also see the steps below as individual numbered compositions.

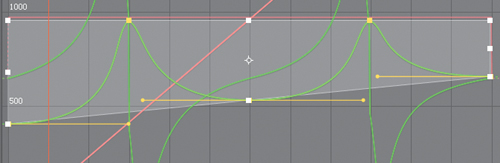

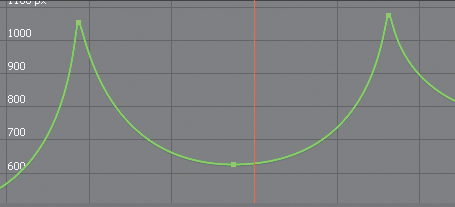

To enable the Graph Editor, click its icon in the Timeline panel ![]() or use the shortcut Shift+F3. Below the grid that appears in place of the layer stack are the Graph Editor controls (Figure 2.3).

or use the shortcut Shift+F3. Below the grid that appears in place of the layer stack are the Graph Editor controls (Figure 2.3).

Figure 2.3. The Graph Editor is enabled in the Timeline panel instead of default Layer view. There is no option to see them together.

Show Properties

By default, if nothing is selected, nothing displays in the graph; what you see depends on the settings in the Show Properties menu ![]() . Three toggles in this menu control how animation curves are displayed in the graph:

. Three toggles in this menu control how animation curves are displayed in the graph:

Tip

To work in the Graph Editor without worrying about what is selected, disable Show Selected Properties and enable the other two.

• Show Selected Properties displays whatever animation property names are highlighted.

• Show Animated Properties shows everything with keyframes or expressions.

• Show Graph Editor Set displays properties with the Graph Editor Set toggle enabled.

Show Selected Properties is the easiest to use, but Show Graph Editor Set gives you the greatest control. You decide which curves need to appear, activate their Graph Editor Set toggle, and after that it no longer matters whether you keep them selected.

Tip

The other recommended change prior to working through this section is to enable Default Spatial Interpolation to Linear in Preferences > General (Ctrl+Alt+; or Cmd+Opt+;). Try this if your initial animation doesn’t seem to match that shown in Figure 2.4.

Figure 2.4. The layer travels across the frame like a bouncing ball, going up and down.

To begin the bouncing ball animation, include Position in the Graph Editor Set by toggling its icon ![]() . Alt+P (Opt+P) sets the first Position keyframe at frame 0; after that, any changes to Position are automatically keyframed.

. Alt+P (Opt+P) sets the first Position keyframe at frame 0; after that, any changes to Position are automatically keyframed.

Basic Animation and the Graph View

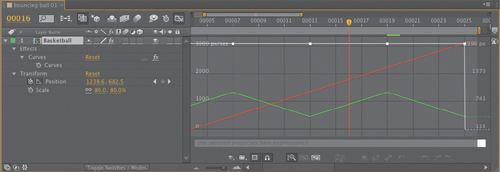

Figure 2.4 shows the first step: a very basic animation blocked in using Linear keyframes, evenly spaced. It won’t look like a bouncing ball yet, but it’s a typical way to start when animating, for new and experienced animators alike.

To get to this point, do the following:

• Having set the first keyframe at frame 0, move the ball off the left of the frame.

• At frame 24, move the ball off the right of the frame, creating a second keyframe.

• Create a keyframe at frame 12 (just check the box, don’t change any settings).

• Now add the bounces: At frames 6 and 18 move the ball straight downward so it touches the bottom of the frame.

This leaves five Position keyframes and an extremely unconvincing-looking bouncing ball animation. Great—it always helps to get something blocked in so you can clearly see what’s wrong. Also, the default Graph Editor view at this point is not very helpful, because it displays the speed graph, and the speed of the layer is completely steady at this point—deliberately so, in fact.

To get the view shown in Figure 2.4, make sure Show Reference Graph is enabled in the Graph Options menu ![]() . This is a toggle even advanced users miss, although it is now on by default. In addition to the not-very-helpful speed graph you now see the value graph in its X (red) and Y (green) values. However, the green values appear upside-down! This is the flipped After Effects Y axis in action; 0 is at the top of frame so that 0,0 is in the top-left corner, as it has been since After Effects 1.0, long before 3D animation was even contemplated.

. This is a toggle even advanced users miss, although it is now on by default. In addition to the not-very-helpful speed graph you now see the value graph in its X (red) and Y (green) values. However, the green values appear upside-down! This is the flipped After Effects Y axis in action; 0 is at the top of frame so that 0,0 is in the top-left corner, as it has been since After Effects 1.0, long before 3D animation was even contemplated.

Notes

![]()

Auto Select Graph Type selects speed graphs for spatial properties and value graphs for all others.

Ease Curves

The simplest way to “fix” an animation that looks too stiff like this is often to add eases. For this purpose After Effects offers the automated Easy Ease functions, although you can also create or adjust eases by hand in the Graph Editor.

Warning

![]()

Mac users beware: The F9 key is used by the system for the Exposé feature, revealing all open panels in all applications. You can change or disable this feature in System Preferences > Dashboard & Exposé.

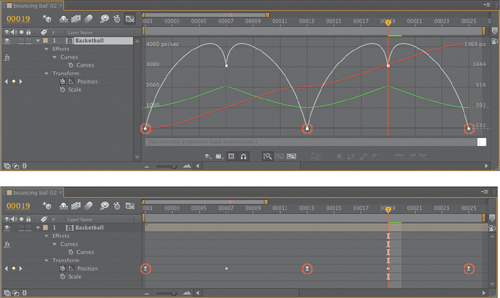

Select all of the “up” keyframes—the first, third, and fifth—and click Easy Ease ![]() (F9). When a ball bounces, it slows at the top of each arc, and Easy Ease adds that arc to the pace; what was a flat-line speed graph now is a series of arcing curves (Figure 2.5).

(F9). When a ball bounces, it slows at the top of each arc, and Easy Ease adds that arc to the pace; what was a flat-line speed graph now is a series of arcing curves (Figure 2.5).

Figure 2.5. Easy Ease is applied (top) to the mid-air keyframes; Layer view (bottom) also shows the change from linear to Bezier with a changed keyframe icon.

Technically, you could have applied Easy Ease Out ![]() (Ctrl+Shift+F9/Cmd+Shift+F9) to the first keyframe and Easy Ease In

(Ctrl+Shift+F9/Cmd+Shift+F9) to the first keyframe and Easy Ease In ![]() (Shift+F9) to the final one, because the ease in each case only goes in one direction. The “in” and “out” versions of Easy Ease are specifically for cases where there are other adjacent keyframes and the ease should only go in one direction (you’ll see one in a moment). In this case it’s not really necessary.

(Shift+F9) to the final one, because the ease in each case only goes in one direction. The “in” and “out” versions of Easy Ease are specifically for cases where there are other adjacent keyframes and the ease should only go in one direction (you’ll see one in a moment). In this case it’s not really necessary.

Meanwhile, there’s a clear problem here: The timing of the motion arcs, but not the motion itself, is still completely linear. Fix this in the Composition viewer by pulling Bezier handles out of each of the keyframes you just eased:

- Deselect all keyframes but leave the layer selected.

- Make sure the animation path is displayed (Ctrl+Shift+H/Cmd+Shift+H toggles).

- Click on the first keyframe in the Composition viewer to select it; it should change from hollow to solid in appearance.

- Switch to the Pen tool with the G key; in the Composition viewer, drag from the highlighted keyframe to the right, creating a horizontal Bezier handle. Stop before crossing the second keyframe.

- Do the same for the third and fifth keyframes (dragging left for the fifth).

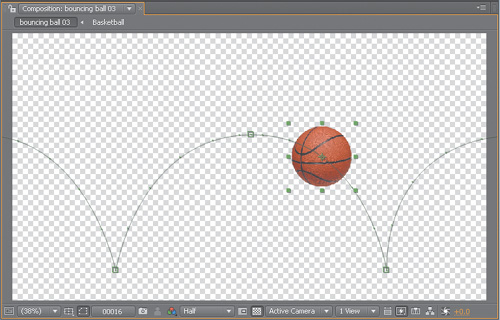

The animation path now looks more like you’d expect a ball to bounce (Figure 2.6). Preview the animation, however, and you’ll notice that the ball crudely pogos across the frame instead of bouncing naturally. Why is that?

Figure 2.6. You can tell from the graph that this is closer to how a bouncing ball would look over time. You can use Ctrl+Shift+H (Cmd+Shift+H) to show and hide the animation path, or you can look in the Composition panel menu > View Options > Layer Controls.

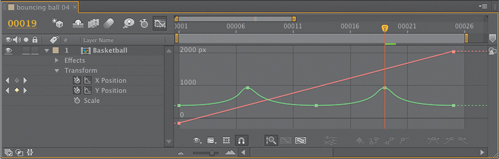

Separate XYZ

The Graph Editor reveals the problem. The red X graph shows an unsteady horizontal motion due to the eases. The problem is that the eases should be applied only to the vertical Y dimension, whereas the X animation travels at a constant rate.

New to After Effects CS4 was the ability to animate X and Y (or, in 3D, X, Y, and Z) animation curves separately. This allows you to add keyframes for one dimension only at a given point in time, or to add keyframes in one dimension at a time.

Select Position and click Separate Dimensions ![]() . Where there was a single Position property, there are now two marked X Position and Y Position. Now try the following:

. Where there was a single Position property, there are now two marked X Position and Y Position. Now try the following:

- Disable the Graph Editor Set toggle for Y Position so that only the red X Position graph is displayed.

- Select the middle three X Position keyframes—you can draw a selection box around them—and delete them.

- Select the two remaining X keyframes and click the Convert Selected Keyframes to Linear button

.

.

Now take a look in the Composition viewer—the motion is back to linear, although the temporal eases remain on the Y axis. Not only that, but you cannot redraw them as you did before; enabling Separate Dimensions removes this ability.

Instead, you can create them in the Graph Editor itself.

- Enable the Graph Editor Set toggle for Y Position, so both dimensions are once again displayed.

- Select the middle Y Position keyframe, and you’ll notice two small handles protruding to its left and right. Drag each of these out, holding the Shift key if necessary to keep them flat, and notice the corresponding change in the Composition viewer (Figure 2.7).

Figure 2.7. If Separate Dimensions is activated, pull out the handles to create the motion arcs right in the Graph Editor; the handles are no longer adjustable in the Composition viewer.

- Select the first and last Y Position keyframes and click Easy Ease; the handles move outward from each keyframe without affecting the X Position keyframes.

- Drag the handles of the first and last Y Position keyframes as far as they will go (right up to the succeeding and preceding keyframes, respectively).

Tip

Separate Dimensions does not play nicely with eases and cannot easily be round-tripped back, so unfortunately you’re best to reserve it for occasions when you really need it.

Preview the result and you’ll see that you now have the beginnings of an actual bouncing ball animation; it’s just a little bit too regular and even, so from here you give it your own organic touch.

Transform Box

The transform box lets you edit keyframe values in all kinds of tricky or even wacky ways. Toggle on Show Transform Box and select more than one keyframe, and a white box with vertices surrounds the selected frames. Drag the handle at the right side to the left or right to change overall timing; the keyframes remain proportionally arranged.

Notes

![]()

There is a whole menu ![]() of options to show items that you might think are only in Layer view: layer In/Out points, audio waveforms, layer markers, and expressions.

of options to show items that you might think are only in Layer view: layer In/Out points, audio waveforms, layer markers, and expressions.

So, does the transform box help in this case? Well, it could, if you needed to

• scale the animation timing around a particular keyframe: Drag the anchor to that frame, then Ctrl-drag (Cmd-drag)

• reverse the animation: Ctrl-drag/Cmd-drag from one edge of the box to the other (or for a straight reversal, simply context-click and choose Keyframe Assistant > Time-Reverse Keyframes)

Notes

![]()

The Snap button ![]() snaps to virtually every visible marker, but not—snap!—to whole frame values if Allow Keyframes Between Frames is on

snaps to virtually every visible marker, but not—snap!—to whole frame values if Allow Keyframes Between Frames is on ![]() .

.

• diminish the bounce animation so that the ball bounces lower each time: Alt-drag (Opt-drag) on the lower-right corner handle (Figure 2.8)

Figure 2.8. How do you do that? Add the Alt (Opt) key when dragging a corner of the transform box; this adjustment diminishes the height of the ball bounces proportionally over time.

If you Ctrl+Alt-drag (Cmd+Opt-drag) on a corner that will taper values at one end, and if you Ctrl+Alt+ Shift-drag (Cmd+Opt+Shift-drag) on a corner, it will skew that end of the box up or down. I don’t do that kind of stuff much, but with a lot of keyframes to scale proportionally, it’s a good one to keep in your back pocket.

Holds

At this point you may have a fairly realistic-looking bouncing ball; maybe you added a little Rotation animation so the ball spins forward as it bounces, or maybe you’ve hand-adjusted the timing or position keys to give them that extra little organic unevenness. Hold keyframes won’t help improve this animation, but you could use them to go all Matrix-like with it, stopping the ball mid-arc before continuing the action. A Hold keyframe ![]() (Ctrl+Alt+H/Cmd+Shift+H) prevents any change to a value until the next keyframe.

(Ctrl+Alt+H/Cmd+Shift+H) prevents any change to a value until the next keyframe.

Drag all keyframes from the one at the top of the middle arc forward in time a second or two. Copy and paste that mid-arc keyframe (adding one for any other animated properties or dimensions at that point in time) back to the original keyframe location, and toggle it to a Hold keyframe (Figure 2.9).

Figure 2.9. Where the graph line is flatlined, the bounce stops mid-air—the result of Hold keyframes, which have the benefit of ensuring no animation whatsoever occurs until the next keyframe.

Beyond Bouncing Balls

In the (reasonably likely) case that the need for a bouncing ball animation never comes up, what does this example show you? Let’s recap:

• You can control a Bezier motion path in the Composition viewer using the Pen tool (usage detailed in the next chapter).

• Realistic motion often requires that you shape the motion path Beziers and add temporal eases; the two actions are performed independently on any given keyframe, and in two different places (in the viewer and Timeline panel).

Animation can get a little trickier in 3D, but the same basic rules apply (see Chapter 9 for more).

Three preset keyframe transition types are available, each with a shortcut at the bottom of the Graph Editor: Hold ![]() , Linear

, Linear ![]() , and Auto Bezier

, and Auto Bezier ![]() . Adjust the handles or apply Easy Ease and the preset becomes a custom Bezier shape.

. Adjust the handles or apply Easy Ease and the preset becomes a custom Bezier shape.

Copy and Paste Animations

Yes, copy and paste; everyone knows how to do it. Here are some things that aren’t necessarily obvious about copying and pasting keyframe data:

• Copy a set of keyframes from After Effects and paste them into an Excel spreadsheet or even an ordinary text editor, and behold the After Effects keyframe format, ready for hacking.

• You can paste from one property to another, so long as the format matches (the units and number of parameters). Copy the source, highlight the target, and paste.

Tip

You can use an Excel spreadsheet to reformat underlying keyframe data from other applications; just paste in After Effects data to see how it’s formatted, and then massage the other data to match that format (if you have Excel skills, so much the better). Once done, copy and paste the data back into After Effects.

• Keyframes respect the position of the current time indicator; the first frame is always pasted at the current time (useful for relocating timing, but occasionally an unpleasant surprise).

• There’s a lock on the Effect Controls tab to keep a panel forward even when you select another layer to paste to it.

• Copy and paste keyframes from an effect that isn’t applied to the target, and that effect is added along with its keyframes.

Close-up: Roving Keyframes

![]()

Sometimes an animation must follow an exact path, hitting precise points, but progress steadily, with no variation in the rate of travel. This is the situation for which Roving keyframes were devised. Figure 2.10 shows a before-and-after view of a Roving keyframe; the path of the animation is identical, but the keyframes proceed at a steady rate.

Figure 2.10. Compare this graph with the one in Figure 2.5 (top); the speed graph is back to a flat-line because the animation runs at a uniform pace. You may not want to bounce a ball, but the technique works with any complex animation, and it maintains eases on the start and end frame.

Pay close attention to the current time and what is selected when copying, in particular, and when pasting animation data.

Layer vs. Graph

To summarize the distinction between layer bar mode and the Graph Editor, with layers you can

• block in keyframes with respect to the overall composition

• establish broad timing (where Linear, Easy Ease, and Auto-Bezier keyframes are sufficient)

The Graph Editor is essential to

• refine an individual animation curve

• compare spatial and temporal data

• scale animation data, especially around a specific pivot point

• perform extremely specific timing (adding a keyframe in between frames, hitting a specific tween point with an ease curve)

In either view you can

• edit expressions

• change keyframe type (Linear, Hold, Ease In, and so on)

• make editorial and compositing decisions regarding layers such as start/stop/duration, split layers, order (possible in both views, easier in Layer view)

By no means, then, does the Graph Editor make Layer view obsolete; Layer view is still where the majority of compositing and simple animation is accomplished.

Notes

![]()

You must enable Allow Keyframes Between Frames in the Graph Editor or they all snap to exact frame increments. However, when you scale a set of keyframes using the transform box, keyframes will often fall in between frames whether or not this option is enabled.

Timeline Panel Shortcuts

The following keyboard shortcuts have broad usage when applied with layers selected in the Timeline panel:

• U toggles all properties with keyframes or expressions applied.

• UU (U twice in quick succession) toggles all properties set to any value besides the default; or every property in the Timeline panel that has been edited.

• E toggles all applied effects.

• EE toggles all applied expressions.

The term “toggle” in the above list means that not only do these shortcuts reveal the listed properties, they can also conceal them, or with the Shift key, they can be used in combination with one another and with many of the shortcuts detailed earlier (such as the Transform shortcuts A, P, R, S, and T or the Mask shortcuts M, MM, and F). You want all the changes applied to masks and transforms, not effects? UU, then Shift+E. Lose the masks? Shift+M.

The U shortcut is a quick way to find keyframes to edit or to locate a keyframe that you suspect is hiding somewhere. But UU— now that is a full-on problem-solving tool all by itself. It allows you to quickly investigate what has been edited on a given layer, is helpful when troubleshooting your own layer settings, and is nearly priceless when investigating an unfamiliar project.

Notes

![]()

The term “überkey” apparently plays on Friedrich Nietzsche’s concept of the “übermensch”—like such an individual, it is a shortcut more powerful and important than others.

Highlight all the layers of a composition and press UU to reveal all edits. Enable Switches, Modes, Parent, and Stretch columns, and you see everything in a composition, with the exception of

• contents of nested compositions, which must be opened (Alt/Opt-double-click) and analyzed individually

• locked layers

• shy layers (disable them atop the Timeline panel to show all)

• composition settings themselves, such as motion blur and frame rate

In other words, this is an effective method to use to understand or troubleshoot a shot.

Dissect a Project

If you’ve been handed an unfamiliar project and need to make sense of it quickly, there are a couple of other tools that may help.

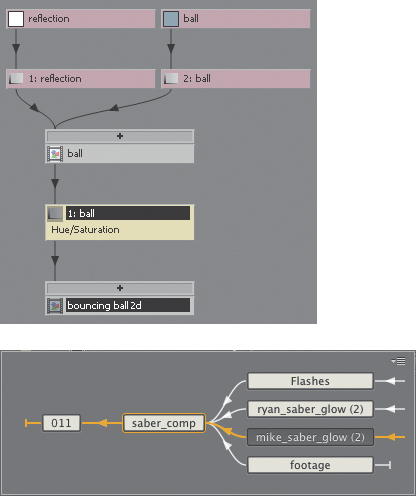

Composition Mini-Flowchart, aka Miniflow (with the Timeline panel, Composition panel, or Layer panel active, press the Shift key; see Figure 2.11, bottom) quickly maps any upstream or downstream compositions and allows you to open any of them simply by clicking on one.

Figure 2.11. The tree/node interface in Flowchart (top) is a diagnostic rather than a creative tool. The gray nodes are compositions, the red source clips, and the yellow is an effect, but there is no way to apply or adjust an effect in this view. Its usage has largely been superseded by the new Miniflow (bottom), which focuses interactively on the current composition.

If you’re looking for a whole visual map of the project instead, try Flowchart view (Ctrl+F11/Cmd+F11 or the tree/node icon in the Composition viewer). You have to see it to believe it: a nodal interface in After Effects (Figure 2.11, top), perhaps the least nodal of any of the major compositing applications.

This view shows how objects (layers, compositions, and effects) are used, and in what relationship to one another. The + button above a composition reveals its components; for the cleanest view, toggle layers and effects off at the lower left. Click the ![]() icon to switch the view to flow left to right, which fits well on a monitor, or Alt-click (Opt-click) it to clean up the view. You can’t make any edits here, but you can double-click any item to reveal it where you can edit it—back in the Timeline panel, of course.

icon to switch the view to flow left to right, which fits well on a monitor, or Alt-click (Opt-click) it to clean up the view. You can’t make any edits here, but you can double-click any item to reveal it where you can edit it—back in the Timeline panel, of course.

Close-up: Nerd-Based Compositing

![]()

Flowchart, the After Effects nodal view, reveals the truth that all compositing applications are, at their core, nodal in their logic and organization. However, this particular tree/node view is diagnostic and high-level only; you can delete but not create a layer.

Keyframe Navigation and Selection

Although no shortcut can hold a candle to the all-encompassing überkey, there are several other useful essentials:

• J and K keys navigate backward and forward, respectively, through all visible keyframes, layer markers, and work area boundaries; hide the properties you don’t want to navigate.

• Click Property Name to select all keyframes for a property.

• Context-click keyframe > Select Previous Keyframes or Select Following Keyframes to avoid difficult drag selections.

• Context-click keyframe > Select Equal Keyframes to hit all keyframes with the same setting.

• Alt+Shift+Transform shortcut, or Opt+Shift+Transform shortcut (P, A, S, R, or T), sets a keyframe; no need to click anywhere.

Tip

If keyframes are “hiding” outside the Timeline panel—you know they’re there if the keyframe navigation arrows stay highlighted at the beginning or end—select all of them by clicking the Property Name, Shift-drag a rectangular selection around those you can see, and delete the rest.

• Click a property stopwatch to set the first keyframe at the current frame (if no keyframe exists), or delete all existing keyframes.

• Ctrl-click (Cmd-click) an effect stopwatch to set a keyframe.

• Ctrl+Alt+A (Cmd+Opt+A) selects all visible keyframes while leaving the source layers, making it easy to delete them when, say, duplicating a layer but changing its animation.

• Shift+F2 deselects keyframes only.

Read on; you are not a keyframe Jedi—yet.

Keyframe Offsets

To offset the values of multiple keyframes by the same amount in Layer view, select them all, place the current time indicator over a selected keyframe (that’s important), and drag the setting; all change by the same increment. If instead you type in a new value, or enter an offset, such as +20 or +-47, with a numerical value, all keyframes take on the (identical) new value.

Notes

![]()

Keyframe multiselection in standard Layer view (but not Graph Editor) is inconsistent with the rest of the application: you Shift-click to add or subtract a single frame from a group. Ctrl-clicking (Cmd-clicking) on a keyframe converts it to Auto-Bezier mode.

With multiple keyframes selected you can also

• Alt+Right Arrow or Alt+Left Arrow (Opt+Right Arrow or Opt+Left Arrow) to nudge keyframes forward or backward in time.

• Context-click > Keyframe Assistant > Time-Reverse Keyframes to run the animation in reverse without changing the duration and start or end point of the selected keyframe sequence.

• Alt-drag (Opt-drag) the first or last selected keyframe to scale timing proportionally in Layer view (or use the transform box in the Graph Editor).

Spatial Offsets

3D animators are familiar with the idea that every object (or layer) has a pivot point. In After Effects, there are two fundamental ways to make a layer pivot around a different location: Change the layer’s own anchor point, or parent it to another layer.

After Effects is generally designed to preserve the appearance of the composition when you are merely setting up animation, toggling 3D on, and so forth. Therefore, editing an anchor point position with the Pan Behind tool triggers the inverse offset to the Position property. Parent a layer to another layer and the child layer maintains its relative position until you further animate either of them. If you set up your offsets and hierarchy before animating, you may find fewer difficulties as you work—although this section shows how to go about changing your mind once keyframes are in place.

To simply frame your layers, Layer > Transform (or context-click a layer > Transform) includes three methods to fill a frame with the selected layer:

• Ctrl+Alt+F (Cmd+Opt+F) centers a layer and fits both horizontal and vertical dimensions of the layer, whether or not this is nonuniform scaling.

• Ctrl+Alt+Shift+H (Cmd+Opt+Shift+H) centers but fits only the width.

• Ctrl+Alt+Shift+G (Cmd+Opt+Shift+G) centers but fits only the height.

Those shortcuts are a handful; context-clicking the layer for the Transform menu is nearly as easy.

Anchor Point

The Pan Behind tool (Y) repositions an anchor point in the Composition or Layer viewer (and offsets the Position value to compensate). This prevents the layer from appearing in a different location on the frame in which you’re working.

The Position offset is for that frame only, however, so if there are Position keyframes, the layer may appear offset on other frames if you drag the anchor point this way. To reposition the anchor point without changing Position:

• Change the anchor point value in the Timeline panel.

• Use the Pan Behind tool in the Layer panel instead.

• Hold the Alt (Opt) key as you drag with the Pan Behind tool.

Any of these options lets you reposition the anchor point without messing up an animation by changing one of the Position keyframes.

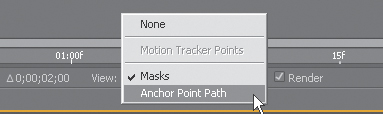

You can also animate the anchor point, of course; this allows you to rotate as you pan around an image while keeping the view centered. If you’re having trouble seeing the anchor point path as you work, open the source in the Layer panel and choose Anchor Point Path in the View pop-up menu (Figure 2.12).

Figure 2.12. Switch the default Masks to Anchor Point Path for easy viewing and manipulation of the layer anchor point. For the bouncing ball, you could move the anchor point to the base of the layer to add a little cartoonish squash and stretch, scaling Y down at the impact points.

Parent Hierarchy

Layer parenting, in which all of the Transform settings (except Opacity, which isn’t really a Transform setting) are passed from parent to child, can be set up by revealing the Parent column in the Timeline panel. There, you can choose a layer’s parent either by selecting it from the list or by dragging the pick whip to the parent layer and using the setup as follows:

• Parenting remains valid even if the parent layer moves, is duplicated, or changes its name.

• A parent and all of its children can be selected by context-clicking the parent layer and choosing Select Children.

• Parenting can be removed by choosing None from the Parent menu.

• Null Objects (Ctrl+Alt+Shift+Y/Cmd+Opt+Shift+Y) exist only to be parents; they are actually 100 x 100 pixel layers that do not render.

You probably knew all of that. You might not know what happens when you add the Alt (Opt) key to Parent settings:

• Hold Alt (Opt) as you select the None option and the layer reverts to the Transform values it had before being parented (otherwise the offset at the time None is selected remains).

• Hold Alt (Opt) as you select a Parent layer and its Transform data at the current frame is applied to the child layer prior to parenting.

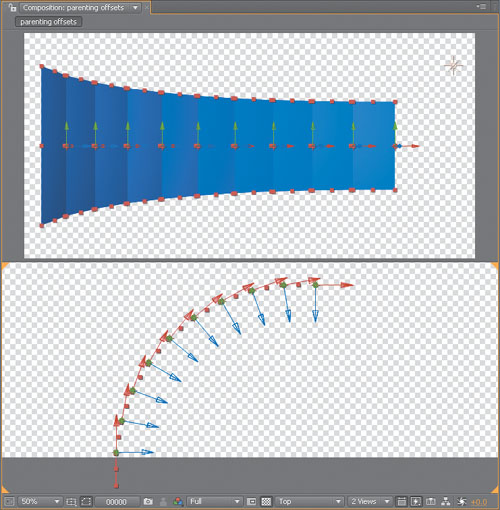

This last point is a very cool and easily missed method for arraying layers automatically. You duplicate, offset, and parent to create the first layer in a pattern, then duplicate that layer and Alt+Parent (Opt+Parent) it to the previous duplicate. It behaves like the Duplicate and Offset option in Illustrator (Figure 2.13).

Figure 2.13. Until you know the trick, setting up a series of layers as an array seems like a big pain. The trick is to create the first layer, duplicate, and offset; now you have two. Duplicate the offset layer and—this is the key—Alt+Parent (Opt+Parent) the duplicate to the offset. Repeat this last step with as many layers as you need; each one repeats the offset.

Motion Blur

Motion blur is clearly essential to a realistic shot with a good amount of motion. It is the natural result of movement that occurs while a camera shutter is open, causing objects in the image to be recorded at every point from the shutter opening to closing. The movement can be from individual objects or the camera itself. Although it essentially smears layers in a composition, motion blur is generally desirable; it adds to persistence of vision and relaxes the eye. Aesthetically, it can be quite beautiful.

Close-up: Blurred Vision

![]()

Motion blur occurs in your natural vision, although you might not realize it—stare at a ceiling fan in motion, and then try following an individual blade around instead and you will notice a dramatic difference. There is a trend in recent years to use extremely high-speed electronic shutters, which drastically reduce motion blur. It gives the psychological effect of excitement or adrenaline by making your eye feel as if it’s tracking motion with heightened awareness.

The idea with motion blur in a realistic visual effects shot is usually to match the amount of blur in the source shot, assuming you have a reference; if you lack visual reference, a camera report can also help you set this correctly. Any moving picture camera has a shutter speed setting that determines the amount of motion blur. This is not the camera’s frame rate, although the shutter does obviously have to be fast enough to accommodate the frame rate. A typical film camera shooting 24 fps (frames per second) has a shutter that is open half the time, or ![]() of a second.

of a second.

Decoding After Effects Motion Blur

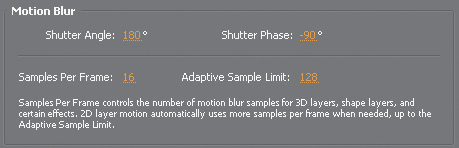

The Advanced tab of Composition Settings (Ctrl+K/Cmd+K) contains Motion Blur settings (Figure 2.14):

• Shutter Angle controls shutter speed, and thus the amount of blur.

Figure 2.14. These are the default settings; 16 is really too low for good-looking blur at high speed, but a 180-degree shutter and –90 degree shutter angle match the look of a film camera. Any changes you make here stick and are passed along to the next composition, or even the next project, until you change them.

• Shutter Phase determines at what point the shutter opens.

• Samples Per Frame applies to 3D motion blur and Shape layers; it sets the number of slices in time (samples), and thus, smoothness.

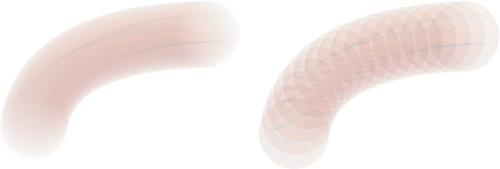

• Adaptive Sample Limit applies only to 2D motion blur, which automatically uses as many samples as are needed up to this limit (Figure 2.15).

Figure 2.15. The low default 16 Samples Per Frame setting creates steppy-looking blur on a 3D layer only; the same animation and default settings in 2D use the higher default Adaptive Sample Limit of 128. The reason for the difference is simply performance; 3D blur is costlier, but like many settings it is conservative. Unless your machine is ancient, boost the number; the boosted setting will stay as a preference.

Here’s a bit of a gotcha: The default settings that you see in this panel are simply whatever was set the last time it was adjusted (unless it was never adjusted, in which case there are defaults). It’s theoretically great to reuse settings that work across several projects, but I’ve seen artists faked out by vestigial extreme settings like 2 Samples Per Frame or a 720-degree blur that may have matched perfectly in some unique case.

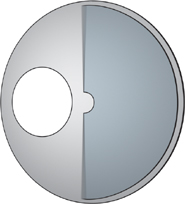

Shutter Angle refers to an angled mechanical shutter used in older film cameras; it is a hemisphere of a given angle that rotates on each frame. The angle corresponds to the radius of the open section—the wedge of the whole pie that exposes the frame (Figure 2.16). A typical film shutter is 180 degrees—open half the time, or ![]() of a second at 24 frames per second.

of a second at 24 frames per second.

Figure 2.16. The 180-degree mechanical shutter of a film camera prevents light from exposing film half the time, for an effective exposure of 1/48 of a second. In this abstraction the dark gray hemi-circular shutter spins to alternately expose and occlude the aperture, the circular opening in the light gray plate behind it.

Electronic shutters are variable but refer to shutter angle as a benchmark; they can operate down in the single digits or close to a full (mechanically impossible) 360 degrees. After Effects motion blur goes to 720 degrees simply because sometimes mathematical accuracy is not the name of the game, and you want more than 360 degrees.

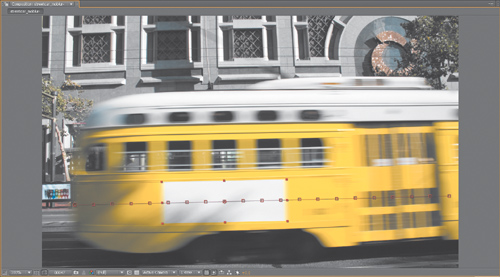

If you don’t know how the shutter angle was set when the plate was shot, you can typically nail it by zooming in and matching background and foreground elements by eye (Figure 2.17). If your camera report includes shutter speed, you can calculate the Shutter Angle setting using the following formula:

shutter speed = 1 / frame rate * (360 / shutter angle)

This isn’t as gnarly as it looks, but if you dislike formulas, think of it like this: If your camera takes 24 fps, but Shutter Angle is set at 180 degrees, then the frame is exposed half the time (180/360 = ½) or ![]() of a second. However, if the shutter speed is

of a second. However, if the shutter speed is ![]() per second with this frame rate, Shutter Angle should be set to 90 degrees. A

per second with this frame rate, Shutter Angle should be set to 90 degrees. A ![]() per second shutter would have a 9-degree shutter angle in order to obey this rule of thumb.

per second shutter would have a 9-degree shutter angle in order to obey this rule of thumb.

Notes

![]()

The 02_motion_blur folder and project on the disc contains relevant example comps. The 02_shutter_angle_diagram project contains the graphics used to create Figure 2.16.

Shutter Phase determines how the shutter opens relative to the frame, which covers a given fraction of a second beginning at a given point in time. If the shutter is set to 0, it opens at that point in time, and the blur appears to extend forward through the frame, which makes it appear offset.

Figure 2.17. The white solid tracked to the side of the streetcar has been eye-matched to have an equivalent blur by adjusting Shutter Angle; care is also taken to set Shutter Phase to –50% of Shutter Angle so that the layer stays centered on the track.

The default –90 Shutter Phase setting (with a 180-degree shutter angle) causes half the blur to occur before the frame so that blur extends in both directions from the current position. This is how blur appears when taken with a camera, so a setting that is –50% of shutter angle is essential when you’re adding motion blur to a motion-tracked shot. Otherwise, the track itself appears offset when motion blur is enabled.

Enhancement Easier Than Elimination

Although software may one day be developed to resolve a blurred image back to sharp detail, it is much, much harder to sharpen a blurred image elegantly than it is to add blur to a sharp image. Motion blur comes for free when you keyframe motion in After Effects; what about when there is motion but no blur and no keyframes, as can be the case in pre-existing footage?

If you have imported a 3D element with insufficient blur, or footage shot with too high a shutter speed, you have the options to add the effect of motion blur using

• Directional Blur, which can mimic the blur of layers moving in some uniform X and Y direction

• Radial Blur, which can mimic motion in Z depth (or spin)

• Timewarp, which can add motion blur without any retiming whatsoever

Yes, you read that last one correctly. There’s a full section on Timewarp later in this chapter, but to use it to add procedural motion blur

• set Speed to 100

• toggle Enable Motion Blur

• set Shutter Control to Manual

Now raise the Shutter Angle and Shutter Samples (being aware that the higher you raise them, the longer the render time). The methodology is similar to that of Reel Smart Motion Blur (RE:Vision Effects); try the demo version on the book’s disc and compare quality and render time.

Timing and Retiming

After Effects is more flexible when working with time than most video applications. You can retime footage or mix and match speeds and timing using a variety of methods.

Absolute (Not Relative) Time

After Effects measures time in absolute seconds, rather than frames, whose timing and number are relative to the number per second. If frames instead of seconds were the measure of time, changing the frame rate on the fly would pose a much greater problem than it does.

Change the frame rate of a composition and the keyframes maintain their position in actual time, so the timing of an animation doesn’t change (Figure 2.18), only the position of the keyframes relative to frames. Here’s a haiku:

Figure 2.18. The bounce animation remains the same as the composition frame rate changes; keyframes now fall in between whole frames, the vertical lines on the grid.

keyframes realign

falling between retimed frames

timing is unchanged

Likewise, footage (or a nested composition) with a mismatched frame rate syncs up at least once a second, but the intervening source frames may fall in between composition frames. Think of a musician playing 3 against 4; one second in After Effects is something like the downbeat.

Time Stretch

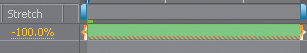

Time Stretch lets you alter the duration (and thus the speed) of a source clip—but it doesn’t let you animate the retiming itself (for that, you need Time Remap or Timewarp). The third of the three icons at the lower left of the Timeline panel reveals the In/Out/Duration/Stretch columns.

I mostly change the Stretch value and find the inter-related settings of all four-columns redundant. I also never use a Time Stretch setting that is anything but an integer multiple or division by halves: 300%, 200%, 50%, or 25%. You can do without the columns altogether using the Time Stretch dialog (context-click > Time > Time Stretch). Ctrl+Alt+R (Cmd+Opt+R) or Layer > Time > Time-Reverse Layer sets the Stretch value to –100%. The layer’s appearance alters to remind you that it is reversed (Figure 2.19).

Figure 2.19. The candy striping along the bottom of the layer indicates that the Stretch value is negative and the footage will run in reverse.

Layer > Time > Freeze Frame applies the Time Remap effect with a single Hold keyframe at the current time.

Frame Blend

Suppose you retime a source clip with a Stretch value that doesn’t factor evenly into 100%; the result is likely to lurch in a distracting, inelegant fashion. Enable Frame Blend for the layer and the composition, and After Effects averages the adjacent frames together to create a new image on frames that fall in between the source frames. This also works when you’re adding footage to a composition with a mismatched frame rate. There are two modes:

• Frame Mix mode overlays adjoining frames, essentially blurring them together.

• Pixel Motion mode uses optical flow techniques to track the motion of actual pixels from frame to frame, creating new frames that are something like a morph of the adjoining frames.

Confusingly, the icons for these modes are the same as Draft and Best layer quality, respectively (Figure 2.20), yet there are cases where Frame Mix may be preferable instead of merely quicker. Pixel Motion can often appear too blurry, too distorted, or contain too many noticeable frame artifacts, in which case you can move back to Frame Mix, or move up to the Timewarp effect, with greater control of the same technology (later in this chapter).

Figure 2.20. The Frame Blend switches for the composition and layer (the overlapping filmstrips to the right of frame). Just because Pixel Motion mode uses the same icon as Best in the Quality switch, to the left, doesn’t mean it’s guaranteed to be the best choice.

![]()

Notes

![]()

The optical flow in Pixel Motion and the Timewarp effect was licensed from the Foundry. The same underlying technology is also used in Furnace plug-ins for Shake, Flame, and Nuke.

Nested Compositions

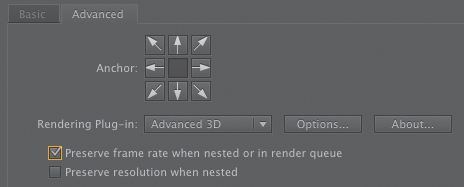

Time Stretch (or Time Remap) applies the main composition’s frame rate to a nested composition; animations are not frame-blended; instead the keyframe interpolation is resliced to this new frame rate. If you put a composition with a lower frame rate into a master composition, the intention may be to keep the frame rate of the embedded composition. In such a case, go to the nested composition’s Composition Settings > Advanced panel and toggle Preserve Frame Rate When Nested or in Render Queue (Figure 2.21). This forces After Effects to use only whole frame increments in the underlying composition, just as if the composition were pre-rendered with that frame rate.

Figure 2.21. The highlighted setting causes the subcomposition to use its own frame rate instead of resampling to the rate of the master composition, if they are different from one another.

Notes

![]()

Effect > Time > Posterize Time can also force any layer to take on the specified frame rate, but effects in the Time category should be applied before all other effects in a given layer. Posterize Time often breaks preceding effects.

Tip

The final Time Remap keyframe is one greater than the total timing of the layer (in most cases a nonexistent frame) to guarantee that the final source frame is reached, even when frame rates don’t match. To get the last visible frame you must often add a keyframe on the penultimate frame.

Time Remap

For tricky timing, Time Remap trumps Time Stretch. The philosophy is elusively simple: A given point in time has a value, just like any other property, so it can be keyframed, including eases and even loops —it operates like any other animation data.

Ctrl+Alt+T (Cmd+Opt+T) or Layer > Time > Enable Time Remapping sets two Time Remap keyframes: at the beginning and one frame beyond the end of the layer. Time remapped layers have a theoretically infinite duration, so the final Time Remap frame effectively becomes a Hold keyframe; you can then freely scale the layer length beyond that last frame.

Beware when applying Time Remap to a layer whose first or last frame extends beyond the composition duration; there may be keyframes you cannot see. In such a case, I tend to add keyframes at the composition start and end points, click Time Remap to select all keyframes, Shift-deselect the ones I can see in the Timeline panel, and delete to get rid of the ones I can’t see.

Tip

There is also a Freeze Frame option in After Effects; context-click a layer, or from the Layer menu choose Time > Freeze Frame, which sets Time Remap (if not already set) with a single Hold keyframe.

Timewarp

The Foundry’s sophisticated retiming tool known as Kronos provides the technology used in Pixel Motion and Timewarp. Pixel Motion is an automated setting described earlier, and Timewarp builds this up by adding a set of effect controls that allow you to tweak the result. Timewarp uses optical flow technology to track any motion in the footage. Individual, automated motion vectors describe how each pixel moves from frame to frame. With this accurate analysis it is then possible to generate an image made up of those same pixels, interpolated along those vectors, with different timing. The result is new frames that appear as if in between the original frames. When it works, it has to be seen to be believed.

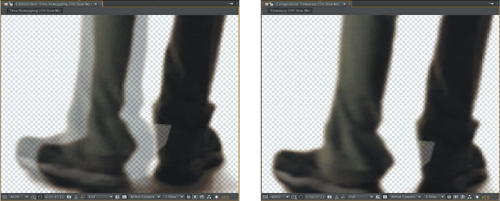

What’s the difference between Time Remap, which requires little computational power, and the much more complex and demanding Timewarp? Try working with the keyed_timewarp_source sequence on the disc (02_timewarp folder) or open the associated example project where it’s already done. Figure 2.22 shows the basic difference between Frame Mix and Pixel Motion.

Figure 2.22. Frame Mix (left) simply cross-dissolves between adjacent whole frames, where as Pixel Motion (right) analyzes the actual pixels to create an entirely new in-between frame.

Notes

![]()

The Foundry’s Kronos tool is now available as a stand-alone plug-in which among other features uses the GPU to outperform Timewarp. A demo version can be found on the book’s disc.

So flipping the Frame Blend toggle in the Timeline panel (Figure 2.20) to Pixel Motion with Time Stretch or Time Remapping gets you the same optical flow solution as Timewarp with the same Pixel Motion method. What’s the difference?

• All methods can be used to speed up or slow down footage, but only Time Remapping and Timewarp dynamically animate the timing with keyframes.

• All methods can access all three Frame Blending modes (Whole Frames, Frame Mix, and Pixel Motion).

• Time Remapping keyframes can even be transferred directly to Timewarp, but it requires an expression (see note) because Timewarp uses frames and Time Remapping seconds.

Notes

![]()

To transfer Time Remap keyframes to Source Frame mode in Timewarp, enable an expression (Chapter 10) for Source Frame and enter the following:

d = thisComp. frame

DurationtimeRemap * 1/d

Timewarp is worth any extra trouble in several ways:

• It can be applied to a composition, not just footage.

• It includes the option to add motion blur with the Enable Motion Blur toggle.

• The Tuning section lets you refine the automated results of Pixel Motion.

To apply Timewarp to the footage, enable Time Remapping and extend the length of the layer when slowing footage down—otherwise you will run out of frames. Leave Time Remapping with keyframes at the default positions and Timewarp will override it.

The example footage has been pre-keyed, which provides the best result when anyone (or anything) in the foreground is moving separate from the background. Swap in the gs_timewarp_source footage and you’ll see some errors. Add the keyed_timewarp_source layer below as a reference, set it as the Matte Layer in Timewarp, and the errors should once again disappear, with the added benefit of working with the full unkeyed footage.

Notes

![]()

Roto Brush (see Chapter 7) is a highly effective tool to create a foreground Matte Layer for Timewarp. This helps eliminate or reduce motion errors where the foreground and background move differently.

You can even further adjust the reference layer and precomp it (for example, enhancing contrast or luminance to give Timewarp a cleaner source), and then apply this precom-posed layer as a Warp Layer—it then analyzes with the adjustments but applies the result to the untouched source.

The Tuning section is where you trade render time and accuracy, but don’t assume that greater accuracy always yields a better result—it’s just not so. These tools make use of Local Motion Estimation (LME) technology, which is thoroughly documented in the Furnace User Guide, if you ever want to fully nerd out on the details.

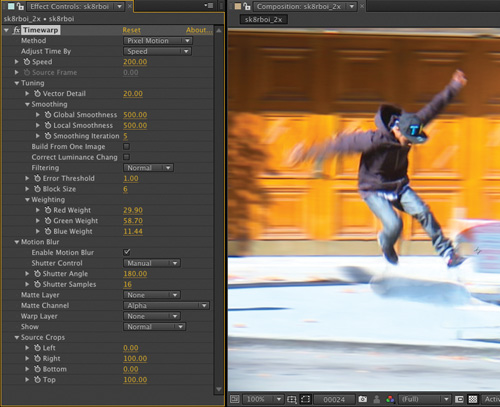

Now try a shot that needs more tuning and shows more of the flaws of Pixel Motion, and how Timewarp can help solve them. The footage in the 02_rotoSetup_sk8rboi folder on the disc features several planes of motion—the wheels of the minivan, the van itself, the skater—and at the climatic moment where the skater pulls the 360 flip, the board utterly lacks continuity from one frame to the next, a classic case that will break any type of optical flow currently available (Figure 2.23).

Figure 2.23. Timewarp’s excellent super slow-mo capabilities work best with continuous motion, such as the torso and legs of the skater; the board itself and his hands move much more unpredictably from frame to frame, causing more difficulty. The best fix is to rotoscope to separate these areas from the background.

Here are a few tweaks you can try on this footage, or your own:

• While raising Vector Detail would seem to increase accuracy, it’s hard to find anywhere in this clip where it helps. Not only does a higher number (100) drastically increase render time, it simply increases or at best shifts artifacts with fast motion. This is because it is analyzing too much detail with not enough areas to average in.

• Smoothing relates directly to Vector Detail. The Foundry claims that the defaults, which are balanced, work best for most sequences. You can raise Global Smoothness (all vectors), Local Smoothness (individual vectors), and Smoothing Iterations in order to combat detail noise, but again, in this case it changes artifacting rather than solving it.

• During the skateboard ollie itself, the 360 flip of the board is a tough one because it changes so much from frame to frame. Build From One Image helps quite a bit in a case like this—instead of trying to blend two nonmatching sets of pixels, Timewarp favors one of them. The downside is that sudden shifts occur at the transition points—the pixels don’t flow.

• There’s no need in this clip to enable Correct Luminance Changes—it’s for sudden (image flicker) or gradual (moving highlights) shifts in brightness.

• Error Threshold evaluates each vector before letting it contribute; raise this value and more vectors are eliminated for having too much perceived error.

• Block Size determines the width and height of the area each vector tracks; as with Smoothing, lower values generate more noise, higher values result in less detail. The Foundry documentation indicates that this value should “rarely need editing.”

Notes

![]()

Twixtor (RE:Vision Effects) is a third-party alternative to Timewarp; it’s not necessarily better but some artists—not all—do prefer it. A demo can be found on the disc.

• Weighting lets you control how much a given color channel is factored. As you’ll learn in Chapter 5, the defaults correspond to how the eye perceives color to produce a monochrome image. If one channel is particularly noisy—usually blue—you can lower its setting.

• Filtering applies to the render, not the analysis; it increases the sharpness of the result. It will cost you render time, so if you do enable it, wait until you’re done with your other changes and are ready to render.

Tip

Did you notice back in the Motion Blur section that Timewarp can be used to generate procedural motion blur without retiming footage (Figure 2.24)?

Figure 2.24. Footage that is shot overcranked (at high speed, left) typically lacks sufficient motion blur when retimed. Timewarp can add motion blur to speed up footage; it can even add motion blur to footage with no speed-up at all, in either case using the same optical flow technology that tracks individual pixels. It looks fabulous.

The biggest thing you could do overall to improve results with a clip like sk8rboi is to use Roto Brush (see Chapter 7) to separate out each moving element—the van, skater, and background.

So Why the Bouncing Ball Again?

Some computer graphics artists are also natural animators; others never really take to it. After Effects is more animation-ready than most compositing applications, and many compositors don’t need to get much into animation. The exercises in this chapter could tell you in an hour or two which camp you fall into, and along the way, cover just about every major Timeline panel animation tool. If you take the trouble to try the animations and learn the shortcuts, you will find yourself with a good deal more control over timing and placement of elements—even if you never find yourself bouncing any virtual balls.