9. Cultivating Innovation: How to Design a Winning Culture

How Culture Affects Innovation

Layered on top of and spread throughout the organization, a company’s systems and processes are a network of social interactions—the organizational culture. Culture, comprised of unwritten rules, shared beliefs, and mental models of the people, alters the effectiveness of the innovation tools we have described. The mightiest company in the computer industry, IBM, nearly disappeared in the early 1990s. The company’s culture prized homogeneity and conformance, and the company could not deal with the rate of change going on around it. Only a risky and forceful change driven by a new external CEO put IBM back on the track of success.

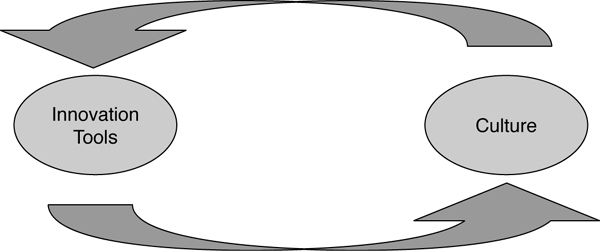

Figure 9.1 depicts how these two elements interact and influence each other and affect the outcome of the innovation effort.

Figure 9.1. The interaction between management tools and culture

Culture is not static; it continually evolves. New systems and processes, new symbols and organizational values can be designed to evolve company culture.1 Dell CEO Kevin B. Rollins launched a concerted effort in 1997 to understand and grow Dell’s culture into a strong competitive asset. The goal was not to create a different culture for Dell, but to adapt and enhance its positive elements. Dell Human Resources Director Paul McKinnon says, “We just aspired to do better.” He and the CEO asked themselves the question, “What would a new winning culture look like here at Dell?”2

Is Innovation the New Religion?

Innovation in some companies is more than a strategy. It’s a way of life, almost a religion. Companies such as Virgin and Southwest Airlines have embedded innovation into their company cultures.3 Virgin CEO Richard Branson expects innovation and rewards it. He has put systems in place to keep innovation alive and a part of the business mentality.

People in organizations riding high due to successful innovation believe intensely in what they are doing so much that the intensity is palpable when you are near them. They are zealous and energetic in espousing their commitment to innovation and their processes that surround it. They think others would benefit from innovation if they only saw the light. Employees at 3M, for instance, can seem almost surprised when visitors to the company don’t have a special creative or innovative interest area of their own.

The cultural anthropologist in us asks, “What is going on here? Why this intensity of belief? Why do innovation processes sometimes become icons?” An example of such an icon is 3M’s “15% free-time” policy, which states that all employees should spend 15% of their time on their own projects and ideas. 3M employees hold this policy in such high esteem that they do not believe the company could survive without it. Google, another place where innovation is deeply embedded in the culture, is going down the same road and has upped the ante, allowing 20% free time for innovation.

Innovation’s mystical aspect is tied to two phenomena:

• Harnessing creativity

• Renewing the company

In an organization that harnesses creativity, employees celebrate that accomplishment. People treat proper management of creativity with a spiritual intensity that is akin to religious belief. For them, creativity in business has an element of luck, and certain organizations are more likely to “get it.” The uncontrollable nature of luck leads some people to attach a mystical aspect to creativity. You are likely to see in the workspaces of such an organization calendars and signs that promote an “idea a day,” or think and rest areas, such as the play rooms some software companies maintain. In general, the air is abuzz with a sense that you are more alive and vibrant when being creative. Innovation in these companies is not an obsession, with everybody worried about how to be more innovative; it has become a way of life ingrained in the business mentality.

The outcome of innovation is renewal and growth for the organization and for all the people within. Successful innovation is viewed differently from other management functions because people perceive that it creates ongoing life for the company. Without innovation, a company succumbs to competitors or market shifts and eventually disappears. As a result, some people in an organization see innovation as securing their futures. For them, innovation is a crucial element of survival, and it needs to be held in high regard and protected.

These phenomena reinforce the power of innovative culture in a company. They can be a vital source of competitive energy, as well as an energizing force for the people in the company.

The Danger of Success

Paradoxically, the biggest threat to innovation is success. The very organizations that are riding high on the success of their innovation efforts, and whose employees believe fervently in the organization and the doctrine of ongoing innovation, are often the organizations most at risk. The risk comes in two forms: complacency and dogma.4

Successful organizations tend to become complacent and conservative in order to preserve their core competencies—those things that lead to their success. This is logical and largely advantageous in the short term. Paradoxically, the things that led to their success could be the very things in the long term that pull them into failure. The danger is that the organization’s managers may become complacent in examining and evaluating their systems and culture because of the performance advantage they enjoy. While enjoying the sensation of success, they may lose the drive that got them there in the first place. Paul Otellini, Intel’s CEO, faced this dilemma when he realized that Intel’s success would not depend on what it had always done well: stamp out faster and faster processors: “The history of the industry was the better mousetrap syndrome: You build a faster thing, and the word will beat a path to your doorstep. But as the industry matured, that no longer became the best way to look at the problem.” Otellini decided that the future would belong to the creative, not the fast. He led the charge to create better, more creative products to run the high-end machines in corporate data centers and make deeper inroads into new consumer markets.5

Success is intoxicating, and people can become very attached to the things they believe cause the success. They become resistant to change, trapped in their own practices. In successful organizations where complacency has set in, it is often very difficult for new ideas and businesses to attract enough resources to get off the ground.

Sometimes this complacency results in a shift to a Play Not to Lose strategy, even though the company’s situation would favor a Play to Win strategy. People start to play more conservatively, dulling the sharpness of the Play to Win innovation strategy. Despite their innovative strengths and relatively strong competitive situation, the companies gradually slide into a Play Not to Lose strategy. Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) was IBM’s main competitor in the mainframe market in the 1980s, with more than 100,000 employees. It was a highly admired company. In contrast to IBM, which had migrated to the computer market, DEC had been a computer company since its inception in 1957. DEC was one of the few companies that could threaten the almighty IBM at the time. Its success was its innovative products, from the successful PDP series in the 1960s to the famed VAX series in the 1980s. However, DEC was unable to adapt to the market. Two forces changed the market. First, customers started to demand open architectures, but the company kept offering DEC-centric products. Second, PCs had gained performance power to eat on DEC’s mainframe market. DEC’s new products were engineering masterpieces in line with the previous generations that had made the company so successful. But they were designed for a market that did not exist anymore. After a decade of losses and turmoil, the company was acquired in early 1998.

In addition, as complacency grows, organizational antibodies become more prevalent. Good ideas are attacked because they would require more change, and the organization is complacent—so complacent that it encourages rather than fights organizational antibodies. A highly successful European manufacturer of electronic components saw how its market started to deteriorate in the last part of the 1970s and early 1980s. Its traditional customers had been European consumer electronic manufacturers that were being swept by Asian competitors. Instead of looking for new business models, the company was stuck to its traditional way of doing business. Top management saw new ideas as either too risky for the firm or too difficult for the firm to execute. It saw the destiny written in stone: to die with its customers. Not until a new top management team took over and redefined the company as a distributor was its future again bright.

Some of the companies that we have used as examples of innovation leaders—Apple, Google, GE, IBM, Genentech—currently face the challenge of maintaining their innovation leadership. Their success has led them into a dangerous situation in which they could lose what they once had that made them great. To avoid that loss, they need to avoid complacency, fight organizational antibodies, keep the strategy carefully honed, and maintain a culture that supports innovation.

Sometimes the threat from success is not from complacency, but comes from firmly held cultural values that turn into dogmas. Toyota challenged the long-held cultural dogma of lifetime employment in Japan when it decided that company salaries should be based on capability rather than seniority, and it opted to reward strong performance with bonuses.

Values represent a company’s belief system. They give employees direction in their day-to-day activities and in decision making. However, these beliefs often harden into rigid principles and orthodoxy. Managers follow these principles as unquestionable truth, without thought or evaluation. Although they may have been effective when initiated, they will not remain so, especially in a fast-changing business and market environment. The very values that initially promoted innovation and success in an organization can be the demise of that same organization if they are not evaluated and adjusted on an ongoing basis. Organizational learning plays a key role in fighting dogma.

Take the example of Arthur D. Little, an international management and technology consulting firm headquartered on the Charles River in Cambridge. A.D. Little was proud of its heritage as an innovator: The firm was more than 100 years old and was the oldest consulting company in the world. It had a long history of innovation in consulting services and in technology. The culture favored constant innovation, and many consultants at the company used to feel that the innovative problem-solving approach should be improved every time a new project was started; the net effect was that the company seldom used the same approach twice. Consequently, innovation was rampant. A.D. Little learned that it is very expensive to innovate everything all the time.

Organizational Levers of an Innovative Culture

Managing innovation while delivering performance is a paradoxical process. The organization must be stable in its identity and strategy, yet open to constant change:

• Focused on the things that make it successful in the present market, yet diverse in the areas it explores for opportunities.

• Conservative, to perpetuate the best practices that exist, yet willing to take risks on new and better things.

• Controlling, to ensure that the innovation investment is well used, but trusting enough to allow employees the freedom to create, explore, take risks, and innovate.

Some companies may choose to avoid this paradox; by doing so, they risk reducing innovation to the minimum and fail to fully capitalize on their innovation investment. Alternately, some may avoid the paradox by maximizing innovation and reducing their performance. Neither is recommended.

Success requires managing this paradox by recognizing and managing the levers of culture that affect innovation.

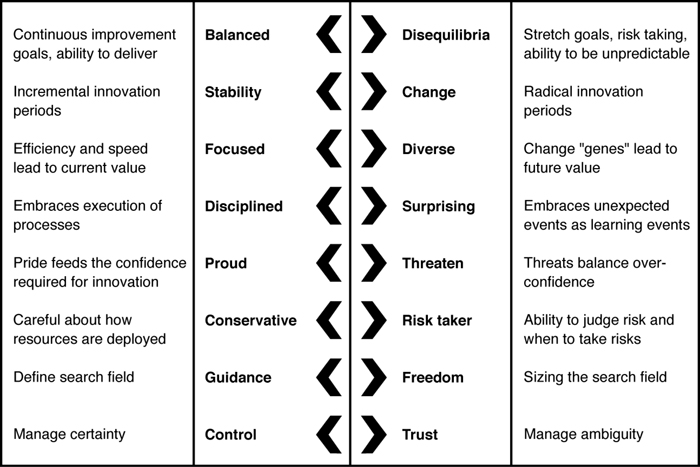

The Levers of an Innovative Culture

Managers have different levers to create the culture that the innovation strategy needs. These levers locate the company in a position between conflicting goals. The particular position depends on the culture that management wants to create. Figure 9.2 lists these levers.

Figure 9.2. Levers of an innovation culture

An innovative culture embraces balance and disequilibria. A balanced culture permits the peace that creativity and value creation need. At the same time, the organization needs to move forward, and only challenges and surprises will move the company forward. Microsoft culture provides stability to people working on its long-term projects, such as the .NET initiative, yet also conveys a sense of urgency to people closer to the strategic game played in the market.

Innovation also requires periods of stability and periods of change. Constant revolution is an unproductive state because the company is unable to fully capture the value of its innovation effort. Toyota’s introduction of the hybrid automobile Prius changed the direction of the industry. Subsequently, Toyota followed with a series of incremental innovations and withheld additional disruptive innovations. A period of incremental innovation (the constant refinement of an idea) should follow each radical innovation, to maximize the value extracted from the radical innovation.

The challenge for top management is to time periods of stability with periods of change—that is, to be aware of and to orchestrate around the ebb and flow of these. An organization cannot be in a constant change process; it needs periods of stability to regroup and regain energy. It needs stability to fully extract the value of innovation. At the same time, the organization must be constantly ready for change. This requires a constant underlying sense of urgency, an imperative for change. The environment may create this need for change. Webvan, even if one of the most expensive failures of the dotcom area, became a threat to existing supermarket chains, which were forced to evaluate how to respond to its eventual success and how to embrace the new technology Webvan was leveraging.

Sometimes the environment may not create the required sense of urgency because the company has a significant advantage sustainable in the foreseeable future or because the market is very stable. In this case, the disequilibria needed to prompt an episode of radical innovation needs to come from inside the organization. BP’s former CEO Lord Brown saw that the company needed to be prodded out of the complacent equilibrium that had affected BP and the other leading companies in the oil industry. He spearheaded the change to focus BP on nontraditional energy issues, including renewable energy. Management plays a critical role in moving the company out of a stable and attractive equilibrium and challenging the organization to innovate. This internal sense of urgency can be communicated through stretch goals, in the form of financial targets (double sales in two years) or nonfinancial targets (enter new geographical markets or grow into new technologies). Stretch targets alone are not enough, though. They need to be supported by a credible strategy that devotes adequate resources to innovation, by systems that encourage innovation, and, most importantly, by a top management team that is committed to innovation.

Focus and diversity is another paradox that successful companies master. Focus provides the efficiency and speed that keeps a company ahead of competitors during evolutionary times. In stable environments, the winners are the companies able to execute—that is, to serve customer needs more efficiently. Focus brings the ability to execute. Management thinking has praised the virtues of a focused strategy for two decades now. But being overly focused leads to myopia and the inability to see potentially important changes in the environment, or a state in which you are inflexible and unable to react to these changes. Focusing on what it knew best left Levi’s unable to react to new trends in the jeans market; focusing on cash registers’ technology that it knew best brought NCR to a very turbulent period.

Embracing diversity in people, ideas, and methods ensures that the organization will thrive in periods of change. The organization must be attentive and must invest in related opportunities. It has to diversify away from what it knows very well and try promising ideas. 3M is constantly experimenting, often outside its traditional markets. Microsoft has diversified progressively from its core PC software to take advantage of market opportunities and has brought entirely different types of people into the company.

An innovative culture embraces discipline and surprise. The second one creates value; the first one captures it. Without discipline, great ideas do not become valuable. Every company successful at innovation follows great ideas with disciplined processes that translate them into value. Philips Electronics, the only European consumer electronics company that has thrived in a market that eliminated all its local competitors, has very detailed processes that have created a sense of discipline together with a sensitivity for new ideas within and outside the company.

Another paradox to manage, and where culture is critical, is a proud organization that also feels threatened. Pride provides the confidence to embark in risky projects with a potentially large payoff. However, pride may also lead to complacency, dismissing the abilities of competitors or potential entrants. Thus, pride needs to come with a sense of uneasiness, a sense of threat that keeps the organization on its toes. The “HP way” created a company in which every employee felt proud and lucky to be part of HP. The pride and the commitment of its people were beyond what any large company had ever achieved and closer to the unity of religious groups. The “HP way” drove the company from its founding. When Carly Fiorina took over, HP’s performance was starting to lose its brightness. Pride seemed to be feeding complacency. Fiorina dramatically changed the emphasis toward the threats that faced the company and each employee. The sense of threat had been losing ground in HP culture, and she brought it back to enhance performance. The culture shock displaced a significant number of employees. The recent demise of Fiorina and the dismal performance of HP stock can be attributed to various reasons, but the move away from the “HP way” and the attempt to refocus the culture away from the sources of the pride required for innovation certainly explain part of these events.

This sense of threat can be real, coming from the market or enacted through the culture of the organization. But in both cases, it provides the balancing force to the potential overconfidence required to address innovation.

An innovative culture is conservative and risk taking at the same time. Vodafone, the leading European mobile phone service provider, is known for its constant innovations in products, services, and marketing. Its leadership is based on staying ahead of its competitors in these dimensions. But Vodafone combines this appetite to try new things with a strong financial control. Risk taking is balanced with attention to measuring and managing risk. Salesforce.com combines new approaches to market its products with careful analyses of its returns. The Red Herring, one of the leading publications in the business of technology, kept its innovation appetite with a cost-conscious culture that emanates from its CEO.

The conservative mindset ensures that employees are aware of the importance of the resources with which they have been entrusted. Every investment and every expense has to be viewed from the perspective of ROI. A culture that supports unquestioned spending, with little regard for the value of the resources, leads to a company that fails in innovation. A conservative culture values risk and carefully evaluates the pros and cons of each innovation opportunity.

Innovation requires freedom, but freedom alone seldom leads to innovation. Real Madrid, one of the best soccer teams in Europe, had a disastrous season in 2003–2004 when the talent it had amassed was the best in the world. Each star player wanted to shine more than the others and played to do precisely this. The coach was unable to guide the players’ desire to be creative into a coherent effort. The 2003–2004 Lakers in the NBA suffered from a similar problem when they lost the finals to a team with much less talent. Too little guidance dilutes the power of freedom into unrelated efforts that ignore each other and do not build a coherent set of abilities going forward. In contrast, too much guidance leads to rejecting good ideas.

Top management needs to outline the “rules of play.” Sony Founder Masaru Ibuka gave a clear direction to the company when he described the mission as follows:

1. Establishing a place of work where engineers can feel the joy of technological innovation, be aware of their mission to society, and work to their heart’s content.

2. Pursuing dynamic activities in technology and production for the reconstruction of Japan and the elevation of the nation’s culture.

3. Applying advanced technology to the life of the general public.

This mission permeated the company since inception and provided guidance for decision makers. A lack of guidance leads to paralysis; people may find too much freedom crippling because they don’t know what they can do next. But very narrow search fields lead to local searches unable to move the company to a new paradigm.

The final paradox is between control and trust. Innovation requires both elements. On one hand, control is required to make informed decisions about resource allocation, strategy development, and performance evaluation. On the other hand, the early stages of innovation are usually hidden to top management; they happen throughout the organization and grow with the support of the local department. An idea that is exposed to the scrutiny of the whole organization too early may easily be killed. Top management needs to trust the systems, people, and culture of the organization to nurture ideas with good potential, even if these ideas are outside the traditional view of top management. Post-its were successful because midlevel managers supported the product through the early development stages. Had the innovation been exposed to senior-level scrutiny earlier in its early stage, it would have lacked sufficient development and supporting market information to further its development, and the idea probably would have been killed.

Legends and Heroes

A large force in shaping culture is the stories that circulate through the organization.6 These stories illustrate extreme manifestations of the culture. As stories circulate from person to person, though, they become distorted. The protagonists become heroes who achieve unheard-of goals. The stories get detached from reality and become legends. Every organization has legends and heroes that communicate the culture.

Nordstrom, one of the most successful retailers in the United States, has a very strong culture centered on customer service. This culture is reflected in stories of regular employees who went beyond their call of duty to serve the customer—driving in the snow to deliver a pair of shoes on time, buying a tie from a competitor to have the perfect suit for a customer, or changing the tire of a customer who could not do it by himself.

Legends and heroes emerge as stories circulate, but management can determine which stories are emphasized and what aspects are highlighted. Electronic Data Systems developed a history of the company’s problems and successes and created an outline of the plan going forward that provided the framework for specific stories describing the emerging culture of the company. This was important in garnering support in the organization and was an integral part of the cultural change and revitalization that was launched in 2004.

The Physical Environment

The indirect effect of the physical environment on creativity is substantial.7 Features in buildings such as colors and shapes have been shown to affect creativity.

This does not mean you should completely redesign your office building, but there are ways to promote a more creative environment using color, light, and space. IDEO’s top performers say they “joined not only because they lead their industry, but also because of their physical and cultural environment.”8 The IDEO office spaces make innovation happen because they are visually and mentally exciting. IDEO’s CEO says that what distinguishes IDEO from its competitors is not their processes, but their ability to see better. He claims that they see the market situation and customer needs better, they see the trends and discontinuities better, and they see solutions better. If clarity of vision is key, if seeing is at the heart of success, then the visual environment of the innovators is a key success factor.

Different Country Cultures Breed Different Innovation Cultures

Understanding and managing organizational culture takes on a new dimension when your organization crosses geographical borders. For managers in multinational and global organizations, the challenge of managing the culture to foster innovation begins with the challenge of understanding how local culture affects the values and beliefs people hold—and thus affects how they think, behave, and contribute. As an HP engineer located in Spain described it, the concept of being on time to a meeting is different in Spain than in the United States. In the United States, it is totally acceptable to finish a conversation in order to be on time to a meeting. However, in Spain, leaving a conversation was unacceptable if the other person had not finished his or her point, even at the expense of being late to a meeting.

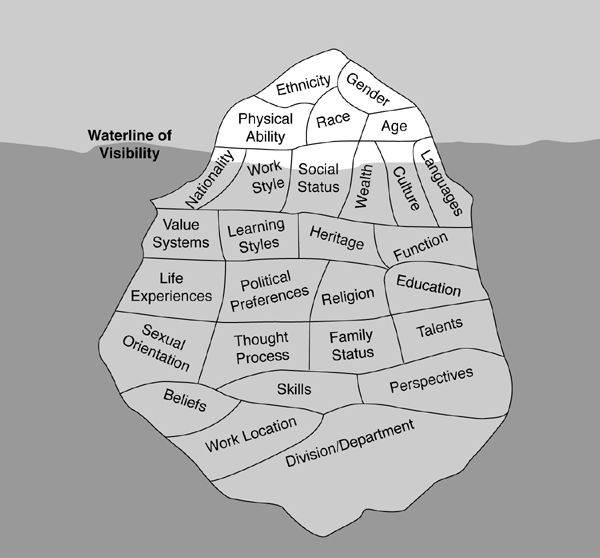

It is important to be aware that a person’s cultural background has a fundamental impact on how he or she responds to organizational culture. Furthermore, most of the elements that make up a culture are not visible or easily discernible. Shell Oil uses Figure 9.3 to educate its employees on this point.

Figure 9.3. The foundations of culture

These differences suggest different perceptions about the source of innovation.9 Asia focuses more on the resources and being able to have the right technology to put the right products into the hands of the customers. The innovation of these companies focuses primarily on managing the resources of the innovation process. In contrast, American companies manage the results of innovation as reflected in product performance. American companies use a pull strategy for innovation, where market demands drive innovation. Asian companies, on the other hand, favor a strategy in which innovation happens in the company and it is then driven to the market. Europe follows a mixed strategy, closer to the American pull strategy, but with more of an emphasis on managing the innovation process.

People and Innovation

The people in an organization adopt, adhere to, change, or reject a culture. They are the vehicles through which a culture has impact and through which innovation (and everything else) happens. Therefore, the human resources strategies of an organization are critically important to building and maintaining innovation.

This section examines the most important elements of people management, including recruiting the right people in the first place, managing them to ensure satisfaction and ongoing motivation, and ensuring that the leaders of the organization fulfill a role that promotes innovation.

Recruiting to Build an Innovative Organization

To foster innovation in your organization, you need to attract and recruit people who will be innovative. It may seem that you need to develop techniques and instruments to identify innovative people and then hire them. However, it is not that simple. True, some people are more naturally innovative than others, but the interplay between the person and his or her environment ultimately determines the level of innovativeness. Even a person who has a proven ability to be innovative would find innovating on an ongoing basis difficult, if not impossible, if put in a culture and situation that do not foster creativity. The culture could stifle his or her innovation, either because the culture is so comfortable for him or her that new approaches do not come to mind, or because the culture is so foreign and uncomfortable that it disrupts that person’s ability to work and contribute.

A software firm was famed for using a very top-down command and control approach. Each employee had clear goals on objectives for the quarter, and these goals were tightly linked to each other. The result was a machine so well tuned to execute on its strategy that the company quickly gained a commanding position in the market. The success attracted very talented employees, and the company appeared to be in a virtuous cycle. However, although the talent it was attracting was excelling at execution, its creativity was unused and even punished—a classic case of unbalanced creativity and value creation. One manager described how she proposed to adapt the software to an Asian market. Her supervisor reluctantly accepted the idea and, because of her insistence, accepted to have the project as part of her goals. The problem was that the objective contributed 5% to her performance—enough to be a worry, but not enough to devote the time required to make it a success. The company began to suffer from a monoculture that suppressed creativity and favored value capture.

Turn Your Recruitment Strategy Upside-Down!

The norm for human resource departments the world over is to find the “right people” with the “right fit” for the organization. However, research into hiring for innovation suggests that a more effective strategy may be to sometimes hire the wrong people—the people who make some people feel uncomfortable during interviews, the people perceived not to fit perfectly into your organization’s culture. This recruiting policy will find people who will challenge the status quo, increase diversity and creativity, and bring higher levels of innovation to the organization.10

Examples abound of success stories in which people have been hired because of their lack of knowledge about the industry. Their lack of preconceived ideas or specific topic knowledge permitted them to explore ideas and see opportunities that others could not. Jane Goodall and her groundbreaking research on chimpanzees is a good example of this. Louis Leakey, the famous anthropologist, offered Goodall the job of researching chimpanzees in Africa. She was reluctant to take the job due to her lack of knowledge and scientific training. However, this was exactly what Leakey wanted—no preconceived ideas of chimpanzee behavior to cloud observation of Goodall’s findings. Goodall’s results were a major breakthrough, and Leakey later commented, “If she had not been ignorant of existing theories, she would never have been able to observe and explain so many new chimp behaviors.”11

However, it can be difficult to hire people who do not fit comfortably in your organization’s preconception of what an employee should be. Remember that you will have to manage the resulting tensions that arise. To hire “outside the mold” to stir up innovation, consider doing some of the following:

• Hire people you think will not fit in but will contribute to creative tension.

• Hire people you don’t like who have significant capabilities and knowledge.

• Invite people from other companies as visitors, and let them tell you what is right and wrong with your innovation.

• Look for people who lack some of the knowledge required for the post, but who have some significant level of compensating qualities.

• Hire those who will question rather than accept.

When you think about it, the characteristics listed here perfectly describe Christopher Columbus. By all accounts, he did not fit in, always questioned the norm, was not well liked, and made a pest of himself in courts across Europe. Spain’s Ferdinand and Isabella gave him a special task, one that put his obstreperous personality and dogged determinism to good use. It also put him far away from others who found him too difficult to stomach. The net result was the discovery of new lands, the accrual of massive wealth, and the recognition of Spain as the leader in world exploration. Columbus perhaps represents the best example of innovative hiring in the history of the Western world.

Hiring the wrong people requires that you hire carefully. Hire skilled people who bring a different perspective, with the qualities required to do an excellent job in their assignment. The aim is to create a team that is creative and can rise to the challenge. Hiring wrong still requires that people hired be team players and have the basic capabilities to be a good match to the prospective job or assignment.12 The old adage “People are your most important asset” is wrong. The right people are your most important asset.13

The Role of Senior Management

If the top managers do not understand the inevitable challenges of innovation, the effort is doomed to failure even as it starts. Thomas Edison knew that people were an important part of innovation. He referred to his team, the army of researchers who developed the ideas and the scientists and machinists who created the prototypes, as muckers. The odd term came from the job title of workers who cleaned out the stables; Edison even referred to himself as the “head mucker.” His metaphor for the people involved in innovation left no doubt about the no-nonsense, hard-working approach he had to innovation.14

Leading Innovation

Innovation leadership should provide the following:15

• An aspiration that challenges complacency and demands that the organization go beyond its current performance, to search, create, and surprise the customer. Sony’s founder constantly challenged his engineers to do things that had never been done before, such as develop new ways to create an image on a TV screen (the Trinitron tube) or very cheap video (the Betamax system).

• A vision that tells the organization where it is going. Johnson & Johnson’s credo, which has guided the company for more than 60 years, starts by saying, “We believe our first responsibility is to the doctors, nurses, and patients, to mothers and fathers and all others who use our products and services.” This vision makes Johnson & Johnson’s reason to exist transparent to employees and other constituencies: Its main mission is to make the life of doctors, nurses, and patients better.

• A leadership commitment in terms of resources. Without this commitment, aspiration and vision are not taken seriously. The new products group at a major consumer goods company was told by senior management that innovation was vitally important and that higher levels were required to meet growth targets. To support this innovation initiative, senior management sent a clear signal of its commitment. Managers assessed the adequacy of the resources to meet the challenge, identified several critical gaps, and quickly filled them. The resource-allocation process serves as an important communication tool to begin to translate long-term strategic plans into actions that people in the organization understand.

• An innovation strategy and a set of processes and management systems to support the strategy. Cheering for innovation and then rewarding, emphasizing, and pressuring employees for short-term performance does not make sense, although it is a common situation in many firms. As a manager described it, “We are behind in product design and product quality, and a big reason for it is the bureaucracy that we have.”

• Leadership by example. When people see the team at the top doing what it says, the message becomes credible. Examples come in very different flavors, from acquisitions that move the organization into new territory, to a remodel of the top management team, to enhanced visibility of innovators within the organization.

• A clear sense of command. Business is about tradeoffs, and innovation is no exception. The top management team is where the chain of command ends and where certain decisions have to be made. In the 1980s, PC companies faced the decision of either having proprietary systems or bending to the IBM standard (which later became the Wintel standard). The decision was not easy, and most of the companies that did not adopt IBM’s standard disappeared (only Apple survived, and not without problems).

• A culture receptive to new ideas and change. Jeffrey Immelt, CEO of GE, stepped up to this challenge when he took charge; he engaged the company in a reassessment of the direction and level of innovation. He challenged norms of behavior and showed that change was necessary for survival.

These are the collective responsibility of senior management. However, the CEO has special responsibilities.

The Role of the CEO

One of the key roles of the CEO is to make innovation part of the culture of the company. Putting the innovation strategy and systems in place is not enough. The CEO needs to work on and in the innovation culture. IDEO, one of the world’s leading industrial design firms and a company known for its innovative culture, says that methodology alone is not enough to create innovation in your organization. According to founder and chairman David Kelley, “Some companies seem more comfortable going through the methodological motions than making the cultural commitments that ongoing innovation demands.”16

Earlier innovation approaches attempted to kluge together the business and technology parts of the organization, but the effect was always suboptimal. If the technology group was in charge of innovation, business management was included in the oversight and management of the process (in other words, a stage-gate process). Likewise, if the strategy and business people were driving innovation, the recommendation was to invite the technology people to the table. The goal was to achieve balance and collaboration between the two groups. However, this missed the essential point: Innovation is based on managing both functions effectively and in concert. Unfortunately, the business functions in an organization cannot effectively manage the technology side, and vice versa. The CEO needs to make certain that collaboration occurs and becomes part of the culture. Steve Jobs worked this critical cultural angle at Apple by being the clear leader of innovation and pushing hard to ensure effective collaboration between the technology and business folks.

Culture and the Innovation Rules

We have come full circle and returned to the point where we started the discussion of the seven rules in Chapter 1, the role of the CEO as leader. The culture of an organization has many components, but one of the most important is leadership. The CEO has a significant impact on the innovation culture that grows in the organization. Marc Benioff, chairman and CEO of Salesforce.com, says, “The difference between success and failure in innovation is leadership.” He says that culture is the most important ingredient that aligns the company and allows it to make its numbers.17

The innovation culture provides the business mentality for innovation. That is the reason many attempts to improve innovation focus on culture; it is the cross-cutting element that threads its way across all the innovation rules. But these views tend to see innovation as amenable to only soft, elusive, almost mystical actions. An innovation culture interacts with the very tangible performance measures and incentives. These are crucial management tools for changing and forming the appropriate innovation behavior, and those changes take place inside the culture. Even organizational antibodies have a cultural component, and different organizations have different types of responses to try to thwart change. Certainly, managing the balance between creativity and value capture has a cultural component. All of these are important aspects of changing culture.

You don’t change culture by going at it directly. You get people to change how they do things, how they think about things, and how they talk about things. And these changes seep in and become the new culture. Dell’s former CEO Rollins used this approach: He worked to have important new values added to the way the people thought about their business. He pushed to have those values, codified in a document called “The Soul of Dell,” become the norms of action, and he influenced the thinking and discussions within Dell.18

Remember, how you innovate determines what you innovate. Culture is an important variable in that equation. It is not just differences in the processes, organization, leadership, performance measures, or incentives that separate the innovation leaders from the others; it is the culture.