2. Mapping Innovation: What Is Innovation and How Do You Leverage It?

A New Model of Strategic Innovation

One of the most common misconceptions is that innovation is primarily, if not exclusively, about changing technology.1 Mention innovation to many business-savvy CEOs, and they envision R&D labs where engineers and scientists are developing the next new technology. However, innovation is not just about changing technologies.

High-performing companies innovate by leveraging both new business models and improved technologies.2 In Chapter 1, “Driving Success: How You Innovate Determines What You Innovate,” we described the business model innovation of Dell and the technology and business model innovations of Apple. Plenty of other examples abound. eBay developed a new online business model for auctions using readily available, albeit fairly new, Internet technology. The retail giant Wal-Mart currently dominates its retail space and has used commercially available computer communication technologies to hyperintegrate its supply chain with suppliers, thereby creating a new business model with significant cost savings.3

Nick Donofrio, lead researcher at IBM, said, “We define ‘innovation’ as our ability to create new value at the intersection of business and technology. We have to have new insights. We have to do things differently. We cannot rely just on invention or technology for success.”4

Even the stodgy, asset-intensive steel industry has seen innovation of this type. Nucor Steel transformed the steel industry when it developed a production technology to turn old metal into steel and changed its business model to capture maximum value. Nucor’s new business model focused on relatively small volume production of high-value products, effectively reversing the heritage industry model of large-scale production runs of commodity products. The combined effect of the technology change and the business model shift sent ripples of change throughout the industry.

Rarely does a technology change occur without also causing a change in business processes. The reverse is also true. Both innovations go together and must be thought and implemented as a whole. For instance, a new technology might require changes in the way the manufacturing facility organizes its work, or a change in how marketing communicates with the company’s customers.

One of the best-known examples of business model-driven innovation is the history of the auto industry in the first half of the twentieth century. Initially, all cars were manufactured in shops, and the process was very labor intensive; each unit was a unique piece of artisan work. The first radical change in the business model came with Henry Ford’s move toward standardization, which applied the concept of a production line to the car industry. Although Ford used new technologies—mainly process technologies to increase the efficiency of its production lines and supply chains—the radical innovation came from the business model dimension. The whole concept of the auto industry was turned upside down—from shop work to production line, from product performance to product cost, from customization to standardization, from assembly to vertical integration, from niche market to mass market. The second transition came when General Motors again redefined the business model, this time at the expense of Ford. Alfred Sloan relied on even less technology than Ford to execute its business model transformation. His ingenuity played through the business model and management knowledge (soft technology, if you want) to overtake Ford. General Motors segmented the market, offered differentiated functionality to each segment, and introduced flexibility in the production process to offer a richer product line.

Successful organizations combine technology change and business model change to create innovation. In addition, to successfully integrate a robust model of innovation into the business mentality, the CEO and the leadership team must balance both the business and technology elements of innovation.

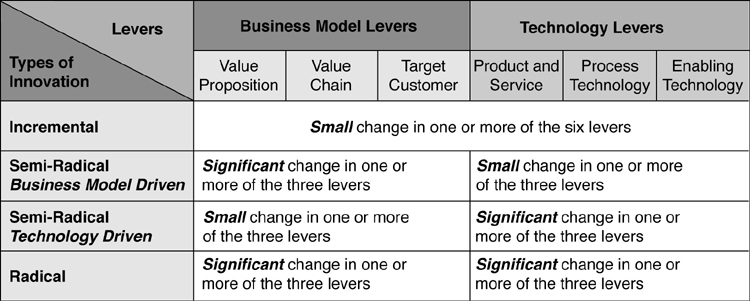

Figure 2.1 illustrates the six levers for change—three in business model and three in technology. Innovation involves changes to one or more of these six elements, as we discuss later in the chapter. In this chapter, we unpack the key characteristics of the business model and technology drivers for innovation (which we began describing in Chapter 1) and describe the six specific levers of change that are at the root of all innovations.

Figure 2.1. The six levers of innovation

Business Model Change

Business models describe how a company creates, sells, and delivers value to its customers. Business model change can drive innovation in three areas:

• Value proposition: What is sold and delivered to the market

• Supply chain: How it is created and delivered to the market

• Target customer: To whom it is delivered

These are the fundamental elements of every business strategy and the logical focal points for innovation.

Value Proposition

Changes in the value proposition of the product or service—essentially, what you sell and deliver to the marketplace—can involve an entirely new product or service, or an expanded proposition for an existing offering. For example, several brands of toothpaste have recently added whitening to their ever-growing list of delivered values, such as cavity protection, breath improvement, and tartar control. Likewise, automobile manufacturers often add new features to their car and truck models, or they provide enhanced after-purchase services. In the world of computing and information management, IBM is moving away from a product-driven value proposition and has tightly bundled a wide range of services with its products. In fact, services have become a major part of its business; in 2003, 48% of IBM’s revenues came from providing services, generating 41% of profits. IBM’s acquisition of PricewaterhouseCoopers (now IBM Global Services) and the growth of hosted applications within the OnDemand initiative are all strategic moves toward enhancing the service aspect of IBM’s product offering. Amazon changed its service offering to become an online mall or retail platform selling goods from other retailers on its site, such as clothes from the Gap, Nordstrom, and Eddie Bauer, and sporting goods with more than 3,000 brands.5

Supply Chain

The second element of innovative business model change is the supply chain—how value is created and delivered to the market. Changes to the supply chain are usually behind-the-scenes changes that customers typically do not see. This type of business model change affects steps along the value chain, including the way an entity organizes, partners, and operates to produce and deliver its products and services. In the 1980s, when Sun Microsystems worked with outside organizations as strategic partners to provide value-creating activities, it created a new approach to outsourcing and gained a big competitive advantage—but you could not discern it explicitly in its products. Supply chain changes also can result when combining parts of the supply chain that different companies typically provide. For example, when General Electric began to couple service contracts with its manufactured electric turbines, it created new synergies and value in its part of the supply chain. Customers bought the package of hardware and service, and GE was able to secure above-average margins for the industry. This significant innovation had major market implications; the business model changed to include hardware and service as bundled products, requiring companies in the space to master both aspects to remain competitive.

Innovations can also come from redefining relationships with suppliers. Toyota redefined this relationship in the car industry during the 1970s. Toyota changed from the traditional confrontational relationship between suppliers and automakers to a collaborative relationship in which suppliers participated in the successes and failures of the automaker. Innovations can also come from carefully managing relationships with complementary assets. Beyond relying on the growth of the platform itself, Microsoft’s Xbox entry into the gaming market depended on game developers who would create applications for it.

Target Customer

Changes in to whom you sell—the target customer segments—usually occur when an organization identifies a segment of customers to which it does not currently direct its marketing, sales, and distribution efforts, but which would consider its products and services valuable. For example, developers of the nutritional bars originally targeted athletes and extreme sports participants. Later, companies found that other customer segments, such as women, were a potentially large set of customers for the nutritional bars. Relatively small changes to the ingredients, packaging, and advertising increased the potential market for the bars several-fold.

Dockers, a brand of ready-to-wear clothing, specifically targeted the “lower-maintenance” customer group with its stain-fighting, no-iron khakis. Dockers targeted these fashion-challenged men with its signature khakis, a departure from its usual targeted segment of fashion-conscious men, and experienced renewed growth.6

Although innovation driven by changes to the targeted customers is not as common as innovation achieved through changes to the supply chain or value proposition, companies should not overlook it when seeking opportunities to innovate.

These three levers—the value proposition, supply chain, and target customer—are the basis for creating business model innovation that leading companies such as Dell, Nucor Steel, and GE have used to their advantage.

Technology Change

Sometimes new technologies are a major part of an innovation, and they stand out and garner significant attention. Other times, the new technologies are hidden from sight and can only be seen by the technical people servicing them. Either way, technology change can fuel innovations in three distinct ways:

• Product and service offerings

Product and Service Offerings

A change to a product or service that a company offers in the marketplace—or introducing an entirely new product or service—is the most easily recognized type of innovation because consumers see the changes first hand. In today’s fast-changing market, consumers have come to expect significant and recurring technological innovation of this type. Consumers have been conditioned to expect product innovation to such an extent that people now commonly time their purchases—for example, waiting for the release of a new model of an MP3 player with additional features and increased storage capacity.

Other examples of product-based technology innovation include the frequent new features released on mobile phones and automobiles. New “blockbuster” prescription drugs are also the result of this type of innovation. McDonald’s introduction of low-fat oil enabled it to capture a new market segment—health-conscious consumers—with the same product and service offering. The new oil does not affect the taste (or perceived quality) of its offering, but it makes the product attractive to an entirely new segment and possibly enhances the attractiveness to existing customers. McDonald’s pioneered this approach to fast food, and it has enabled the company to maximize the value of its existing product and service offering.

Process Technologies

When we think about technology innovation, we think about innovation that drives the performance of the products or services that the company offers. For example, when we think about memory chips, we think about capacity, access speed, or even energy consumption. Product innovation comes to mind because it quickly translates into functionality that the customer can value and price. But product innovation is only one application of technology.

Changes in the technologies that are integral parts of product manufacturing and service delivery can result in better, faster, and less expensive products and services.7 These process technology changes are usually invisible to the consumer but often vital to a product’s competitive posture.8 Examples include food-processing technologies, automobile manufacturing, petroleum refining, electricity generation, and manufacturing in every industry. Process technologies also include the materials used in the manufacturing—after all, manufacturing and materials are intimately connected. For service providers, the process technologies are elements that allow the service to be delivered—the equipment that sends and receives the telephone signals that make up phone service, the package-sorting stations and delivery trucks that allow packages to be delivered by express package service companies, and the airplanes and airports that provide air-transport services. For products and services, process technologies are an essential part of the innovation equation.

Companies continually strive to make changes to the process technologies that could reduce cost and improve the quality of existing products or services. This is especially true in commodity products or services, where it is increasingly difficult to differentiate the product or service; in commodities, cost is often the only way to compete. Certainly, the electric utility industry feels this cost pressure in production, transmission, and distribution of electricity. However, the competitiveness of all products and services benefits from improvements in process technologies.

Enabling Technologies

A third source of technology innovation resides in what we call enabling technology. Instead of changing the functionality of the product or the process, enabling technology allows a company to execute strategy much faster and leverage time as a source of competitive advantage. For example, information technology facilitates the exchange of information among the various participants in the value chain. Closer communications speeds up business processes from product development to supply chain management.

Although it is the least visible to customers, change in enabling technologies, such as information technologies, can be important because it helps ensure better decision making and financial management. For example, Wal-Mart has made important changes to its enabling information-management technologies and has significantly improved its capability to track and manage its partners, the supply chain, and finances.

Integrating the Innovation Model

This new model of innovation requires integrating the management of business models and technologies inside the company. But this integration does not always occur. Facing increasingly effective competition, Intel in 2004 was spending billions on developing and commercializing technology innovations, but it apparently was not focusing on business model innovation. The question asked in Silicon Valley was not whether Intel had the right technologies, but whether it had the right business model to compete in the years ahead. It appeared to many that business model and technology innovation had become separated. Traditionally, organizations create and manage the changes to business models in parts of the organization that are far removed and culturally different from where the technology change is managed. Successful innovation depends on integrating the mental models and activities regarding business models and technology management.

Three Types of Innovation

Not all innovations are created equally; they do not entail the same risks or provide similar rewards. The generic types of innovation include the following:

• Incremental

• Semiradical

• Radical

Incremental innovation leads to small improvements to existing products and business processes. It can be thought of as an exercise in problem solving, with a clear goal but a puzzle to solve in how to get there. At the opposite end, radical innovation results in new products or services delivered in entirely new ways. It can be thought of as an exercise in exploration, pursuing something relevant but unknown in a particular direction. To make the best strategic decisions regarding innovation, it is necessary to understand the characteristics of each type and when it is appropriate to use each. The Innovation Framework, illustrated in Figure 2.2, shows how the different types of innovation fit into the Innovation Matrix.9

Figure 2.2. The Innovation Framework10

For periods of time, a company can be tremendously successful with only incremental changes to its technology. A traditional model of technology change predicts relatively long periods of evolution (incremental innovation) punctuated by short periods of revolution (in which incremental innovation is useless and a radical technology is required).11

A classic example is the refrigeration industry.12 During the nineteenth century, ice was harvested from lakes, stored in caves to limit its melting, and transported as perishable goods. The technology evolved incrementally throughout several decades; the growth and harvesting processes became more efficient as new tools and techniques were applied, the storage benefited from creativity, and the packaging to retain the cold in the ships also improved. But in the early part of the twentieth century, a revolutionary technology, refrigeration, radically changed the industry. Incremental innovation in growing, harvesting, storing, and transporting ice became suddenly obsolete. Interestingly, ice companies reacted to this new technology by doing more of what they knew—and doing it a lot better. The largest improvements in ice-based cooling technology happened when the technology was being phased out by this radically new approach to manufacturing cold. That reaction of the ice companies was not uncommon; the companies had pushed the technology they had mastered for tens of years to its limits, but they did not have the capabilities to appreciate the radical technology.13 A similar evolution happened in shipping technology. The pace of innovation in sailing boats increased significantly when steam engine technology became a threat. And after a few years, the new technology displaced sailing as the means of sea transportation.14 Thus, incremental innovation may be a sustainable strategy for long periods of time before a revolution shakes the industry.

This framework provides a powerful way to guide decisions about innovations. Because how you innovate affects what you innovate, understanding the nature of the change required is vital so that the innovation effort can be managed, funded, and resourced appropriately.

Some people work under the misconception that innovation is always about making something new. Actually, all three types of innovation include a mixture of old and new.

Figure 2.3 depicts the six levers for innovation. Incremental innovation always firmly embraces the existing technologies and business model. Although some elements might change slightly in the incremental innovation, most stay unchanged. Semiradical innovations include little or no changes to the levers of one of the innovation drivers—either the technology or the business model. Radical innovations include changes to levers in both the technology and business model, but usually not to all six levers of innovation. Innovation always involves combining something old and something new from the technology and business model levers.

Figure 2.3. The levers for the three types of innovation

Incremental Innovation

Incremental innovation is the most prevalent form of innovation in most companies, often garnering more than 80% of the company’s total innovation investment. Most companies’ innovation portfolios are full of projects aimed at small changes to one or two of the six levers in the business model or technology.15

Incremental innovations are a way to wring out as much value as possible from existing products or services without making significant changes or major investments.16 For example, car manufacturers often make slight modifications to established models every few years to create a sense of freshness and to rejuvenate sales without making major changes or investments.

Incremental innovation in the business model is as important. A good part of management tools is intended to facilitate this type of innovation. Quality control techniques enable companies to constantly improve quality, financial analysis helps identify mistakes, market research provides information to better target customer needs, and supply chain management is intended to increase the efficiency of the supply chain by removing non-value-added activities. In some cases, the business processes have not been tuned up for long periods of time and a more dramatic refinement is required, such as instituting restructuring and reengineering processes.

Incremental innovation might sound like a minor piece in the equation, but it is actually the cornerstone. It is extremely valuable in providing protection from the competitive corrosion that eats away at market share, profitability, or both. By providing small improvements via changes in both the technology and the business model, a company can sustain its product market share and profitability for a longer time, providing better cash flow and payback on its development and commercialization investments. Gillette has done an admirable job of this with its incremental improvements to its razor technologies since 2000.

William V. Hickey, CEO and president of Sealed Air Corporation, sees incremental innovation as preventative medicine for a deadly disease: commoditization. “Our goal is to find ways to make our products noncommodities through added-value and through differentiation—through innovation,” he said.17

Sometimes companies do not have sufficient levels of incremental innovation in their innovation portfolio. For example, James M. Kilts, former chairman and CEO of Gillette, pointed out that even though Gillette had a reputation for generating new products, it had a weakness when it came to nurturing incremental innovation: “New products have traditionally been a driver to success for Gillette; in 2001, 40% of our sales came from products that weren’t around five years ago. But when I joined Gillette a few years ago, I found that there was a lack of incremental innovation across all parts of the company.”19

Having too little incremental innovation can be dangerous to your company’s health because it allows your competitors to piggyback on your innovations and grab customers using copycat technologies and business models.

But more often, companies find themselves struggling to understand why they always seem to be stuck in the incremental innovation space. These companies invest far too much of their resources in incremental innovation and, in so doing, waste time and resources that they could better use elsewhere. Alternatively, if incremental innovations are used to protect uncompetitive products or services that are past their prime and should be retired, incremental innovations divert resources from critical efforts to create significantly new, higher-value products or services. Either way, investing in incremental innovations that do not have a sufficient return on investment robs a company of the opportunity to invest in other innovations that could provide competitive advantage.

Apparently, the natural course is for a company to gravitate over time toward increasing levels of incremental change. The problem with making incremental innovation the center of gravity is that a company cannot succeed or even survive throughout the long term without complementing its innovation portfolio with other types of innovation.

For years, companies and business units (and even government organizations) have busied themselves with exhaustive efforts to get better at what they were doing. Six Sigma, Total Quality, and other techniques have been the focus of most organizations. These provide no significant change but do provide the greatest use of the assets at hand. As has been shown, these techniques can create real value for the business models and technologies already in place. But companies have been so enthralled with these efforts for another reason: They’re easier to implement. Companies have found it easier to work in the incremental space than to undertake semiradical and radical changes. Basically, incremental ideas appear safer and more comfortable because they are more predictable.

The problem with incremental innovation is that it represents constrained creativity, with only small changes permitted; this often becomes the dominant form of innovation and crowds out other, potentially more valuable changes. Companies often become addicted to incremental innovation and its relative safety, only to find that they cannot venture beyond even if they urgently need to.

Companies that have commodity products or services often find themselves stuck in rampant incrementalism. Operating in the traditional commodity arena usually creates unrelenting pressure on profit margins and results in a continual churn of new products. This keeps the company frantically searching for the next incremental change. Everything new that the R&D and business-planning group develops is incremental. Unfortunately, the advantage from the incremental innovations is countered almost as soon as the innovation is made, and the company has to stay on the treadmill, running faster but never getting ahead. This is the dilemma that Chevron Oronite and Lubrizol faced in the lubrication additives business. The competitive environment demanded massive amounts of incremental change to hold on to market share and protect the shrinking profit margins in the industry. Each company wanted an innovation that was big enough to create some significant competitive advantage that others could not immediately copy. However, given the intensity of the competition, they had no time or resources to dedicate to innovations that could break the deadly spiral of rampant incrementalism.

Interestingly, many companies know that being stuck in rampant incrementalism is a trap. However, try as they might, the leadership cannot get the organization to change. Without leveraging the innovation rules, a company cannot break away from rampant incrementalism. The organization will stay stuck in incremental innovation and eventually die.

Semiradical Innovation

A semiradical innovation can provide crucial changes to the competitive environment that an incremental innovation cannot. Semiradical innovation involves substantial change to either the business model or the technology of an organization—but not to both.20 Often change in one dimension is linked to change in the other, although the concomitant change might not be as dramatic or disruptive. For example, semiradical change in technology might require incremental improvement in the business model, and vice versa.

As we mentioned earlier, Wal-Mart provides an example of semiradical innovation of the business model. Early on, it realized that a great segment of the U.S. consumers wanted low-cost, good-quality products. Delivering effectively against that value proposition required changing the entire business model from the traditional retail outlet. The traditional business model was to locate an outlet in urban areas and to sell a limited number of goods with significant service markup. Wal-Mart’s strategy was to apply the supermarket business model to retailing and couple it with a souped-up supply chain that cut costs dramatically. The company opened large store spaces, provided a wide variety of goods at discount prices (but with less service), and slashed prices. This new application of the business model has built one of the world’s most successful companies.

Dow, Dupont, and Novartis have used semiradical innovation to change the traditional agricultural chemicals market into a dynamic agro-biotech market where biotechnology and chemicals have combined to form entirely new products, such as genetically engineered plants with selectively acting chemicals. The competitive advantage for these innovators is tied to intellectual property in plant genetics technology that generates new value to the customer.

A more recent example occurred in the customer relationship market (CRM) of the 1990s. By the end of that decade, Siebel Systems had emerged as the leading provider of systems to manage sales and marketing processes in large organizations. Siebel relied on an expensive business model in which software was installed on the customers’ servers and customized by skilled professionals. The cost of these systems ranged from hundreds of thousands to millions of dollars. But that changed when Marc Benioff founded Salesforce.com in 1999 to deliver sales, marketing, and customer service and support operations to customers via the Web. Moving away from client/server architecture, the new company relied on Internet technology so that customers could readily access the software and store their data on Salesforce.com servers. Moreover, the customers could pay the monthly subscription (less than $100) without needing capital expense approval. Salesforce.com buy decisions happened at lower levels in the organization and spread throughout sales and marketing groups beyond the radar of the top management or the IT department. Initially, the young company focused on sales force automation in small businesses. Then, over time, Salesforce.com increased its product functionality and attracted larger companies with more complex needs. At a fraction of Siebel prices, Salesforce.com offered functionality in areas where high levels of customization were unnecessary. Salesforce.com redefined the business model for a market segment that benefited from inexpensive and simple CRM.

Major changes in technology are not limited to quantum leaps in the performance of a certain component. Sometimes the radical innovation happens at the architectural level:21 Components are organized in a radically new way without a significant change in the technology underlying the components. Incumbents might dismiss this architectural change as being marginal because their attention is focused on the performance of the components rather than their interactions. Such an event happened in the photolithographic alignment equipment industry, in which equipment is used to align the masks with the silicon wafer in chip production. While the basic technology evolved incrementally, the industry leader changed various times from Kobit, to Canon, to PerkinElmer, to GCA, to Nikon. The changes were due to new combinations of existing components that created significant shifts in product performance.

Any semiradical change in either the business model or technology always requires some degree of change in the other. However, the change in one element (in other words, either technology or business model) is much larger and more important to the success of the innovation than the other. For example, Dell’s shift to a significantly new business model for PCs required some (relatively small) changes to its process and enabling technologies (such as the supply chain management and Internet technologies). However, semiradical innovations are asymmetric because there is a significant change either to the business model levers or to the technology levers—but not to both.22

The two areas in the semiradical innovation space are interrelated, and often innovations created in one area (such as technology change or business model change) create important new opportunities in the other. This two-stage innovation in the semiradical space is a major dynamic of innovation that companies need to manage. It is an area of huge potential value creation but that is overlooked or undermanaged by many organizations.

To collaborate in two-stage semiradical innovation, the groups need to have a map of both the business model and technology space in which they compete. Usually each group has a map of its own space but is not knowledgeable of the other group’s space. This leads to missteps, missed opportunities, and the inability to quickly and effectively capture the two-step innovation in the semiradical innovation space. This collaborative innovation map provides a common framework for discussion among the different groups of threats, opportunities, strengths, and weaknesses that are crucial to successful innovation.

Sensing that something is lacking in their overall innovation portfolio and feeling stuck on the treadmill of rampant incrementalism, companies often decide (or are convinced) to solve their innovation problem by launching a major innovation thrust, undertaking aggressive efforts at semiradical or sometimes radical innovations. As a result of improperly diagnosing of their problems and their capabilities, they completely overestimate their ability to use semiradical innovation to jump-start their portfolio. This rush to solve their problems with a major dose of semiradical or radical innovation activities occurred often around the time of the Internet dotcom buzz. Some of the companies that plunged into semiradical and radical innovation endeavors discovered that they lacked the capabilities to convert their discoveries into commercial realities in a reasonable timeframe. For example, the attempt to lead the major U.S. electric utilities to innovate radically different distributed energy approaches in the grid (such as advanced distributed generation technologies and high-tech demand/response measures using sophisticated electronic interfaces) have been plagued by problems and have moved slowly.

Simultaneously managing both the business model and technology components of semiradical innovation is one of the main innovation challenges for organizations. This two-stage innovation in the semiradical space is a major dynamic of innovation that companies need to manage. Some companies can adeptly manage the change in either the technology arena or the business model arena, but seldom in both. This puts them at a significant disadvantage when paired against a company that can manage change in both arenas.

Radical Innovation

A radical innovation is a significant change that simultaneously affects both the business model and the technology of a company.23 Radical innovations usually bring fundamental changes to the competitive environment in an industry.24 For that reason, changes such as Shell Oil’s process for creating and managing radical innovations are called “game changers.” Successful radical innovations have the potential to rewrite the rules of the game in the industry.25

The introduction of disposable baby diapers in the 1970s is a historical example of radical innovation. Employing radically different technologies to replace the woven cloth of traditional diapers, a company in Sweden tried a new approach. The company adapted absorbent fluff pulp from wood and crafted a simple diaper that roughly matched the performance of the traditional cloth diapers. The diaper was bulkier than traditional cloth diapers and looked and felt different, but it was disposable and did not require laundering. Moreover, consumers could buy the disposables in retail stores. This new approach displaced the traditional diaper service and the diaper home-laundering business models.

The combined changes in the technological and business elements led to a fundamental change in home baby care. In the past few years, the diaper arena has seen a new round of semiradical innovation, in the form of special absorbent and containment technologies that have sparked a new generation of ultrathin diapers. Leaders such as Procter & Gamble, Kimberly-Clark, and Johnson & Johnson have invested massive amounts of money and intellectual resources in areas of development and commercialization, and they continue to introduce incremental improvements to the technologies. In this case, a radical innovation changed the industry and led to a series of cascading semiradical and incremental innovations.

Radical innovations surround us today. One radical innovation in the making is X PRIZE, a contest designed to jump-start a private-sector space race and create a space tourism industry. The contest is modeled on the Orteig Prize, the competition that led to Charles Lindbergh’s transatlantic flight in 1927 in the Spirit of St. Louis. Competitors for the X PRIZE come from many different backgrounds and attempt to harness very different technologies to launch humans into space and return them to Earth. The combination of the change in business models—replacing the government with private-sector investors—and the change in technologies could result in a radical innovation with far-reaching consequences.

You get an idea of how risky and hard to sell radical innovation is when you listen to Peter Diamandis, chairman and founder of the X PRIZE Foundation: “I had approached well over one hundred corporate chief executive officers regarding sponsorship. Few were able to grasp the importance of this new market ... and those who were had great difficulty accepting the risks involved.”26 This is a common litany for those embracing radical innovations.

Although radical innovation can create tectonic shifts in an industry and put a company in the lead, investments in radical innovation need to be approached with caution.27 By their nature, radical innovations are low-probability investments.28 Investing in too much radical innovation (if based on unrealistic expectations that “the next new thing” will change the fate of the company) can waste valuable resources that could be better employed in semiradical or incremental innovations. The key is to maintain a balanced portfolio of radical innovations so that the investment matches the business needs.

Ersatz Radical Innovation

Sometimes companies such as Apple combine two semiradical innovations to create a blockbuster innovation that has a fundamental change in an industry. The effect is like a radical innovation but is the result of two separate innovations. We call this phenomenon ersatz radical innovation (in other words, a substitute for radical innovation).

The development of the video rental market during the past decade is a good example of ersatz radical innovation. The video technologies that made home entertainment possible were technology-dominant semiradical innovation. Product and equipment companies introduced new videotape technologies into the home entertainment arena through well-established sales channels and business models. The video movie rental business, a new business model, sprang from the opportunity created by the video technologies and their penetration in the home entertainment marketplace. The technology advancement was not initially coupled to a business model innovation, as it would be on a radical innovation in which both happened simultaneously.

These two semiradical innovations—first through semiradical technology innovation and then through semiradical business model innovation—had a similar effect as if radical innovation had occurred, and the entire industry was changed. However, as with most cases of two-stage semiradical innovation, different groups bore the risks, costs, and benefits of the two stages. First, the consumer home entertainment equipment companies made the investment, bore the risk, and reaped the rewards. Subsequently, the movie companies and then the distribution/rental companies stepped into the picture.

One has to wonder what would have happened if key players from the equipment suppliers and the rental companies had collaborated. Then truly radical innovation would have occurred, and it could have been orchestrated to provide significant benefits for the collaborators.

We are seeing the home entertainment market transformed again by DVD technologies. Initially, DVD movies were handled in the same manner as videos. However, recently a new business model has emerged: Netflix and, most recently, Wal-Mart have changed the traditional business model.

Disruptive Technologies

Disruptive technologies are a type of semiradical technology innovation, brought about by changing the technology basis but not the business model (upper-left quadrant).30

Disruptive innovation is a broader term that addresses both technology and business model changes. Disruptive innovations include technology-driven innovation (semiradical technology innovation; upper-right quadrant). It also can mean changes to the business model in a semiradical business model innovation (lower-right quadrant), as in Southwest Airlines’ low cost, nonhub approach. However, sometimes disruptive innovations include a combination of technology change and business model change—a radical innovation (upper-right quadrant) such as Microsoft’s .NET initiative.

The term disruptive innovation focuses on one of the effects of innovation: namely disruption to the competitive landscape. Incremental, semiradical, and radical innovations, on the other hand, describe the relative change in the technology and business model elements. As we have discussed, disruptive innovation can be a key source of growth, and CEOs widely seek it. However, you cannot manage toward disruption, per se. To effectively manage, innovation, it is crucial to focus on the internal sources of change—technology and business models—and their links. Leveraging and linking changes in technologies and business models is the right way to create disruptions—and the spectrum of innovations that foster growth.

Innovation Model and the Innovation Rules

The innovation model presented here forms the context for every one of the seven innovation rules. Most importantly, the model is the basis for forming the innovation strategy and the development of the portfolio aligned with the overall business strategy. The role of the CEO is to define the role and prominence of business model innovation and technology innovation in the company’s overall strategy. Dell’s CEO, Michael Dell, explicitly focused his company’s innovation on the PC business model. That focus led to a significant change in the competitive dynamics of the industry and a leading position for Dell. In contrast, Sony’s former CEO, Nobuyuki Idei, decided to focus that company on technology innovation, specifically proprietary components to differentiate its products. As a result of that decision, during a four-year period around 2002, Sony spent 70% of its innovation investment on new chips.31

These CEOs made clear decisions on the relative roles of business models innovation and technology innovation for their companies. They realized that direction on the innovation portfolio must come from the top.

Selecting and integrating the priorities for business model change and technology change, and defining the balance among the three types of innovation in the portfolio (incremental, semiradical, and radical innovation) are the basic responsibilities of senior management. These senior-level decisions are the basis the organization will use to execute the strategy. They provide the context for the downstream decisions related to organizational design, the development of innovation networks, and the development and use of metrics and incentives to drive innovation.