4. Rule #2: Restore Brand Relevance

Remaining relevant in a changing world is critical to a brand’s health. Relevance is a key driver of purchase intent. But increasingly trust is also becoming critical as a driver of purchase intent. Of course, it is important to be different. It is important to be relevant. But just differentiation and relevance without trust is a formula for failure.

Trust is a foundational factor on which effective brand relevance and differentiation can be sustainable. We discuss trust in Chapter 7, “Rule #5: Rebuild Brand Trust.” For now, we focus on the principle and the practices necessary to bring about the restoration of relevance.

When brands lose relevance, customers believe that a company does not understand them anymore. They begin to think that the company is no longer interested in supplying them with what they want, but rather that the company wants them to buy what it is prepared to supply.

To restore brand relevance, we must:

1. Begin with developing a thorough knowledge of the marketplace

2. Conduct and have a true understanding of market segmentation. Understanding market segmentation is fundamental to brand revitalization.

3. Create insight into customers.

4. Prioritize the market segments.

5. Using knowledge and insights, we must define the promise of the brand to appeal to the prioritized market segments.

Jim Cantalupo emphasized the necessity of changing to become relevant for McDonald’s customers. He said: “The world has changed. Our customers have changed. We have to change, too.”1

Thorough Knowledge of the Marketplace

As Joan and I learned, there is a lot of unused information in a big company like McDonald’s. All sorts of information is generated, collected, codified, and filed. Most of this information is filed away. Sometime it is read and then filed away. Country-specific information tends to stay in the country even if it has ramifications globally.

Our advice is to find all the information you can. Then read it. Someone must have thought there was value to generating a particular report or writing a particular white paper or research study. With the Internet and selected services such as LexisNexis, information on just about any topic is available. Be aware of what is going on—in your category, in your country, across geography, in the art world, in the cultural landscape, and so on.2

Before we created the McDonald’s segmentation, we asked to see what segmentation work had been conducted in the past. We learned that more than 100 studies that could be called segmentation studies had been conducted since 1988. These studies contained great information.

If you want to be a learning organization, you have to learn who you are, what you know, what the world is, and what it possibly will be like.

A market segment is a definable group of people or organizations that share common needs in a common context. “Need” is the critical concept.

What is not a market segment? A market segment is not a product category. It is not geography. There is no such thing as the French market, the Japanese market, or the Italian market. Geographies are where market segments exist. Geographies are how you organize to deliver the brand promise to the prioritized market segments.

Product categories are not market segments. So, for example, there is no lip-gloss market; there is no mascara market. But there is a market for attractiveness, for youthfulness, for status, and for elegance.

There is no such thing as the automotive market. Nor is there such a thing as the soft drink market or the pet food market or the hamburger market. Products are what we sell to the market; they do not define the market.

If you want a vehicle for driving your children to soccer practice and saxophone lessons, you might consider a Chrysler minivan, a Volvo wagon, or a Toyota SUV. These would all satisfy the same need. Yet, the automotive industry places each of these types of vehicle in a different category because they tend to look at product classifications rather than needs-based market segmentation.

A market segment is a want. If there is no want, there is no market. If there is a global want, there is a global market. If there is a growing want, there is a growing market. If some people in France and some people in Australia share the same want, then they are in the same market. It just happens that they live in different places. If the want is incorrectly defined, the market segment is incorrectly defined.

The role of marketing is the process of profitably providing branded products and services to satisfy customer wants at superior customer-perceived value compared to competitive alternatives. The goal is to attract customers and to increase their brand loyalty.

Sometimes the best way to persuade people is to convince them that you offer a solution to one or more of their leading problems. When a brand can solve one or more of a customer’s leading problems, it is providing the desired benefits. People tend to be risk-averse. The avoidance of pain or the need to solve a problem is a stronger motivator than the attainment of pleasure. That is, people will usually pay more to avoid an unpleasant consequence than to attain a pleasant one. The problem-solution approach is a practical, flexible, and effective approach to the challenge faced by marketers, designers, and R&D teams when it comes to product/service renovation and innovation.

Dyson understood that many consumers had bothersome problems with their vacuum cleaners. They did not like cleaning the bags. And, they became frustrated trying to find the right bag for their specific machine. Dyson came up with a bagless vacuum cleaner. Then, Dyson promised the added benefit of maintenance of superior suction power, a perceived problem with previous conventional vacuums.

Diet Coke satisfied the want for a diet cola that tasted great.

Sometimes a want can be satisfied with a small renovation such as the Chrysler minivan “fourth” door because people were becoming frustrated with second row access from only one side of the vehicle.

Satisfying customer desires is the key differentiator between marketing and selling. Selling is about convincing customers to buy what we know how to provide. Marketing is about providing what we know customers want or will want. Superior understanding of consumer needs provides the basis for outstanding competitive advantage.

The process of market segmentation is about dividing people into different “markets” that share common needs and are differentiated from people in other segments who share different needs.

Those who look at market segmentation as just another research tool miss its real strategic value. The information provided by insightful market segmentation helps direct brand policy, marketing strategies, and resource allocations. It allows you to identify priority areas for innovation. It helps define your competitive set sometimes in ways that are different from what you currently believe. Effective market segmentation drives business strategy, not just brand strategy.

We no longer live in a world where mass marketing works. We no longer live in a world where mass marketing to masses of consumers with a mass message delivered through mass media makes money. In fact, mass marketing as we knew it is dead. In 2004, the cover story of BusinessWeek was “The Vanishing Mass Market.”

As BusinessWeek said, our country has “atomized into countless market segments defined not just by demography but by increasingly nuanced and insistent product preferences.” They said that it is a whole new world.3

Mass marketers lack focus. There is no central point of interest. Mass marketing tries to appeal to everyone, but the result is an average message that everyone likes a little and nobody likes a lot. Market segmentation helps to identify the different groups of people, their needs, and the circumstances in which they use the brands. A former client of ours at Mars liked to say that effective market segmentation provided FEDA, a focused enduring differential advantage.

The discipline that we use for defining the market segmentation is based on a principle originally described by Rudyard Kipling, which he called his “six little friends”: what, who, why, how, when, and where. In marketing, what people want is a function of who they are, why they use, and the context in which they use (how, when, and where they use).

Since our approach is to first understand people’s needs, we first ask why the customer uses: What are the wants underlying usage? What are the problems with what the customer currently uses? Then, we look at who are the people who have these needs. This is called profiling the segmentation. The next step is to define the context (how, when, and where) in which different needs exist.

Journals and market research professionals discuss many different ways to segment. For example, some marketers use product categories as the basis for market segmentation. This is easy and inexpensive. You just divide up the category by the types of products available.

We see this in many categories. For example, in the automotive business, you now have divisions such as midsize, luxury, SUV, and so on. Today, the product segment refinements in the automotive industry border on bewildering definitions such as luxury, mid-luxury, near-luxury sedan, or premium.

A recent story in Automotive News describes the key segments identified by Ford in its desire to have a global platform. Putting aside the issue of reducing manufacturing complexities, the article demonstrates the problems that a company can fall into when it sticks with a product segmentation that is actually product classification. With no needs attached, how do you distinguish between a B-car, a C-car, a CD-car, a CD-crossover, a compact, a midsized, and a rear-wheel-drive car?4

Product segmentation is a manufacturer’s view of the market: assorting and assigning market segment definitions based on what products are made based on product characteristics. So, for one appliance maker, the segmentation was “hot,” “cold,” and “wet.” No consumer ever asks for a hot appliance. They want a stove or conventional oven or microwave or toaster oven or grill that can address such needs as warming, defrosting, reheating, cooking, baking, grilling, and sautéing, and doing these tasks quickly, slowly, overnight, or in real time. And, where do you place a dishwasher that both wets (washes) and dries (hot) your dishware and cutlery?

McDonald’s held to the idea that since it was a big brand, it must appeal to everyone for every reason. There were some who resisted the McDonald’s needs-based segmentation saying that McDonald’s was a “burgers and fries for everyone” brand.

This is wrong. It is product categorization, not needs-based segmentation. And brands cannot appeal to every person for every occasion. By trying to appeal to an undefined mass market, the result is inevitably a mass message of mediocrity.

WHY segmentation focuses on specific needs, functional and emotional. This is the basis for meaningful market segmentation. Needs-based segmentation begins by identifying people or organizations that share common needs and are different from those who share different needs.

It focuses on why people do what they do. WHY segmentation helps drive product and service design, R&D, positioning, pricing, and sales and marketing. A WHY segmentation for suntan lotion could look like this:

• Those who just want a deep, dark tan

• Those who want to tan naturally while actively participating in outdoor activities

• Those who are concerned about getting dry, flaky skin from too much sun

• Those who are worried about skin cancer and want maximum protection

We can define needs-based market segments in terms of functional needs or emotional needs or a combination both types of needs.

But, WHY segmentation alone does not tell us who has the needs; it just tells us the different needs groups that exist. It does not tell us in what contexts these needs occur. This brings us to the Who × Context dimensions of market segmentation. Having defined the needs segments, the next step is to profile these needs: Who has the needs in what contexts?

WHO segmentation helps us to profile the needs segments in terms of demographics, lifestyles, behaviors, or values. This is important. It is also the most fun because it provides a deeper understanding of people. Advertising agencies love WHO segmentation. It is helpful for creating so-called lifestyle-advertising campaigns. Understanding the WHO of the brand segmentation helps to build a brand connection with the customer.

However, without a thorough understanding of customer needs, it is difficult to implement and operationalize brand development strategies. The Gap thought that “age segmentation” alone, would be the way to boost profitability. So they developed the Forth & Towne retail stores with clothing designed for the over-30-year-old female. When the chain was closed, the press described a misunderstanding of the shopping habits of the 35-year-old woman and a whole slew of other reasons why the Forth & Towne stores failed.5

What these reports neglected to say was that women over 30 years old do not all have the same needs, or the same attitudes. “Women over 30” is not a market. What was the need that Forth & Towne intended to satisfy better than alternatives? This was not clear.

WHO segmentation alone does not focus only on consumer psyches. It does help us to profile the needs segments in terms of the distinguishing characteristics of the people who have the identified needs.

Profiling the people associated with the identified needs segments helps us not only to understand the needs better, but also helps us to develop our marketing plans.

CONTEXT segmentation is based on the fact that people have different needs in different contexts. As the situations change, sometimes so do the benefits desired by the customer. For example, you might want one type of beer when you are at a ball game, and another type of beer when you are dining with a client, and another type of beer when you are at home hanging out with some friends while watching TV.

It is helpful to understand how, when, and where a consumer has a particular need. Again, focusing on context alone is not enough: It must be associated with specific needs and specific people who have these needs to grasp the full picture of the market.

Think about beverages. Occasions could be segmented by context:

• Start the day

• Between meals

• With meals (breakfast? lunch? dinner?)

• Alone

• With kids

• With friends

• With business associates

• In the evening

But, this does not provide insight into what needs people have at these different occasions. And, it does not tell us who has these needs.

The primary determinant of market segmentation is first driven by needs. Our brand goal is to profitably promise and deliver the superior satisfaction of specific customer needs at superior value.

That is why we begin with needs-based segments. Then these are profiled in terms of who and context (how, when, and where).

Needs-Based Segmentation Profiles

What do you do now? We put all this information together to create a multidimensional view of the market: What people buy and use is a function of why they need it × who they are × context of use (how, when, where).

For example, needs-based market segmentation for the original Starbucks concept might look something like this. Four basic needs (WHY): I am thirsty, I need a lift, I need to take a pause, I want to enjoy a small luxury.

• Four key coffee occasions (CONTEXT)—Emergency, at home, coffee break, and café society.

• Four people segments (WHO)—Day-timers, night crawlers, new-agers, and connoisseurs

Starbucks chose originally to focus on the “small luxury” need segment. Profiling this need led to the concept Starbuck described as the “third place”—a place away from home and work appealing to those connoisseurs who want the “small luxury” of a premium quality “café society” experience.

Prioritizing the Markets

These three dimensions (WHY × WHO × CONTEXT) define the market. As we described in the example of a vehicle for driving children to events, the customer, not the marketer, defines the market. If the brand is the source of the promised experience made to the customer, then it is the customer’s perspective of the market that matters. Customers tell us what alternatives they consider when they have a specific need in a specific context.

For example, much of the business press sees McDonald’s as a hamburger restaurant. They report market share and brand performance comparing McDonald’s to the other major hamburger brands. And many McDonald’s managers agreed. But this is misleading. McDonald’s satisfies a variety of needs for a variety of people in a variety of contexts. Children have different needs from teens and young adults and parents. The needs are different at breakfast, snack, lunch, and late night. McDonald’s competition is different at breakfast compared to lunch. So, the competitive set is different for each of these WHYs × WHOs × CONTEXTs.

If you are a business traveler about to board a flight home, you may need a meal to eat on the plane. The airport food court creates the competitive set. Your needs may be the ease of carrying the meal one-handed and/or the tidiness of eating the meal on a cramped tray-table. These needs would be different from the needs you would have if you were at a booth in the same restaurant brand in the strip mall near your home with a friend.

Proper market segmentation is fundamental to modern marketing. Superior understanding of customers, their needs, who they are, and in what context they have these needs, provides the basis for outstanding competitive strategic advantage.

However, any research tool is as much an art as a science. Market segmentation is not the absolute answer. It cannot reveal what you must do tomorrow. Market segmentation provides the landscape on which you creatively and intuitively understand where the best current and prospective territories are for your brand.

To find competitive advantage in our fast-paced, changing world, we must have the clearest understanding of our customers from all angles: What they buy as a function of why they buy, who they are, and how, when, and where they use what they buy.

The New York Times reported in March 2007, that for 44 years the Wal-Mart mantra had been “Low prices, always.” Then Wal-Mart adopted a new approach based on market segmentation. Wal-Mart segmented its customer groups with different wants:

• Brand aspirants—People with low incomes who are obsessed with (need to own) brand names.

• Price-sensitive affluents—Wealthier shoppers who love a good deal (want to feel smart).

• Value-priced shoppers—People who like low prices and cannot afford much more (need to stay on a tight budget).

According to the story, “From now on all product decisions will be organized around the three groups.” Wal-Mart, recognizing the differences and the common characteristic of the love for the deal, created “five power product categories with these three groups of customers in mind: food, entertainment, apparel, home goods, and pharmacy.”6 Big brands deal with fundamental human truths. Generating a global market segmentation depends on identifying universal human truths that exist around the world regardless of geography, time, or space. The satisfaction of a “big hunger” for Snickers is a universal truth.

Looking for the “best deal” is a universal truth. Coca-Cola’s satisfaction of “refreshment” is a universal truth. And, big brands like McDonald’s also focus on fundamental human truths. These truths are the shared common denominators that remain stable over time.

While a global brand shares common, universal human truths, the interpretation of these truths must be adapted to relevant local market conditions.

Interpreting your information and your market segmentation is more than reading—it is an art form. It is not sufficient to take the print-out with the statistical data and say “Voila!”

The same raw data can and should be analyzed a variety of ways using many statistical approaches. Look into the data not just at it. But, analyses alone do not reveal truth. To the information, we need to add insight.

Insight is such an overused, misunderstood, and misappropriated term in marketing and marketing research departments. Insight is an underlying human truth about how the target users really think, feel, or act: It helps you to identify unarticulated wants.

To be insightful, you must be open to everything, and you must use everything. You must not only see the data, but also understand what is behind the data. You must apply imaginative escape with disciplined thinking. You must be able to make connections among things, ideas, and visuals that before were unconnected. Think of insight as informed intuition where intuition is the ability to see into the heart of things—seeing beyond appearances. Insight requires sensing, studying, experiencing, and ingesting the present.

You will need to look at your information and your statistical output with a creative eye, not just a mathematical brain. Is there anything surprising? Is there anything that gives you an “aha” moment?

Do your best to make the information meaningful. I wish there were a process for generating customer insight. There is not. It is part of the process, but to do it you need a certain kind of mindset.

Synthesis Versus Analysis

Here is where a new mindset is necessary. In marketing, synthesis will triumph over analysis. Business schools typically teach that through superior analysis, a great creative insight will be revealed leading to a great innovation. This is unfortunate. Analysis leads to an understanding of where we are now and how we got here. Analysis does not lead to understanding where we should be going. The analytic, backward-looking, approach of inspection, retrospection, and dissection cannot help us create our future. Creative breakthroughs are not born out of detailed analysis; they are born out of creative synthesis.

Relying only on detailed analysis leads to idea paralysis. Analysis is about taking things apart. Synthesis is about creatively integrating, rearranging, and reordering familiar elements in unfamiliar ways.

In November 2003, an article in Harvard Business Review observed that “true innovation and strategic value are going to be found more and more in the ‘synthesizers’—the people who draw together stuff from multiple fields and use that to create an understanding of what the company should do.”7

It is important to identify trends. They are ideas and concepts that happen around us and influence the way and manner in which we behave. Trends are valuable because they inform us about what is presently happening in the world around us. But trends are not insights into where we should be going. Trend analyzers try to forecast the future. Creative synthesizers look for ways to create the future. To create the future, we need synthesis, and for synthesis we need synthesizers.

Synthesizers are different people. They think differently. They like ambiguity, analogy, and paradox. They are curious. They make the strange familiar and the familiar strange. Synthesis takes crafts people, artists, and physical and social scientists who see patterns that we overlook or just cannot see, and who can form foresight from fragments of evidence and seemingly unconnected information. Synthesis is essential to the new mindset for the future. Synthesizers will triumph over analyzers.

Prioritize, Prioritize

No brand, no matter how big can address every opportunity effectively. The imperative is to prioritize. And it defeats the purpose of focus to set out to address all the identified market segments. You must put a stake in the ground somewhere. Where do you draw the brand’s territorial boundaries?

So, the next step is to prioritize the market segmentation. This is a difficult decision for many executives. It is much easier to say “Yes” to the high-priority segments. But, it is often difficult to say “No” to the low-priority segments. You hear executives say: “We cannot eliminate anybody.” “We want to appeal to everybody.” “Why are we focusing on young adults? What about empty nesters or seniors?” But, prioritization of the market segmentation is important.

Prioritization does not mean that a brand should focus on only one segment. It also does not mean that a brand can treat every segment equally. Prioritization helps us to decide which segments to focus on.

It requires an understanding not only of our strengths and weaknesses but also of trends and future opportunities. Of course, it also requires consideration of the available resources.

Research techniques alone should not be the only way you select markets. The segments need to be set against the backdrop of your foresight into the future. Think of the possibilities within each segment. Think about what can be as well as what already exists. The market segmentation opportunities you uncover provide direction for stimulating vibrant ideas for growth.

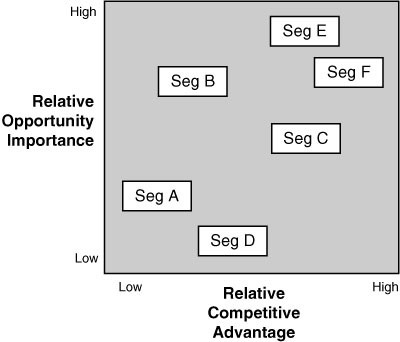

How do you prioritize the market segmentation? Evaluate each segment in terms of both the relative competitive advantage and segment relative opportunity attractiveness.

Here is one tool that we recommend. A two-dimensional analysis like the one in Figure 4.1 helps to prioritize the segmentation. Segments E and F are high-priority opportunities. Segment B may be a great opportunity; however, we need to build organizational competence and develop competitive advantages to compete in this segment. We have a competitive advantage in appealing to segment C, but this is a lower-priority opportunity for profitable growth. Segments A and D are best ignored. We have little competitive advantage, and they represent low profitable growth opportunities.

Leadership means leading the way to the future. Marketers need to lead the way to a new brand destination. McDonald’s knew that internal marketing would be as important as external marketing. We rebranded the role of marketing at McDonald’s, calling it leadership marketing. As we mentioned in Chapter 3, “Rule #1: Refocus the Organization,” leadership marketing is a critical path to refocusing the organization.

The word “leadership” came first because exhibiting leadership is so important to brand revitalization. Leading means rejecting outdated, outmoded ideas of the past. Leadership means providing the strength to jettison marketing practices and mindsets that forced the brand into brand-damaging marketing directions.

Here is an example of the way we exercised leadership marketing to provide brand relevance. A huge, mega-brand like McDonald’s cannot follow the accepted principle that works so well for niche brands: Find a single consumer niche that you can dominate.

So, what is the solution? The choice between mass marketing and niche marketing is a false dilemma. The answer is multisegment marketing. As controversial as it was when we adopted this multisegment strategy at McDonald’s in 2003, the results demonstrate that this approach is correct. Other brands have adopted similar approaches; for example, Best Buy segments by five initial core customer groups:

• Early technology adopters

• Suburban mothers

• Small businesses

• Affluent professionals

• Family fathers

In an article in the Financial Times, the reporter discusses how Best Buy is beginning to focus on two or three of these five groups.8

McDonald’s Segmentation

While there were many potential market segmentation opportunities, prioritization was critical. McDonald’s product and service focus was to provide convenient, affordable, quality food in a clean and friendly environment. McDonald’s referred to this operations strategy as QSCV—quality, service, cleanliness, value. But as a brand strategy, McDonald’s adopted multisegment, multidimensional marketing.

McDonald’s prioritized its marketing resources to focus on three key segments with different needs:9

• Great tasting food and fun for kids

• Healthful eating for young adult moms

• Satisfying food for young adult males

Kids are very important to McDonald’s. They are an important part of the brand heritage. Moms are important because they play a key role in influencing the family’s eating habits. And young adults are important because they are both a growth opportunity and an important part of the new change in brand attitude.

These three key segments identified the “why × who.” McDonald’s also identified four priority contexts: lunch, breakfast, late hours, and snacking.

McDonald’s changed from an unfocused mass marketing to a multifocused brand, focusing on specific market segments with specific marketing messages and specific products.

A brand is not a single word. Some marketing experts say that we should reduce a brand to a single word and aim to own that word in a customer’s mind. This is simple to say. But it is simplistic marketing. A brand is an idea—a multidimensional, multilayered, multifaceted idea. Simplifying a brand to a single word ignores the complexities of a brand and dilutes its appeal. Big brands like McDonald’s are not unidimensional.

Now that we have identified the priority markets for our brand, what is the differentiating brand idea? What is the brand experience we want to promise and deliver to every customer every time? How we articulate that promised experience depends on five specific components: values of the brand, functional and emotional needs the brand promises to satisfy, personality of the brand, and distinguishing supporting features of the brand.

In Guys and Dolls, the wonderful Frank Loesser musical, Adelaide sings: “You promise me this; You promise me that; You promise me everything under the sun; then you give me a kiss, and you’re grabbing your hat, and you’re off to the races again.”9

The promise you make to a specific customer segment is a contract between the customer and brand. It is not something you promise and then “kiss off.” It expresses the contract that we make with customers that if they buy our brand, they will receive the promised brand experience. We need to deliver what we promise.

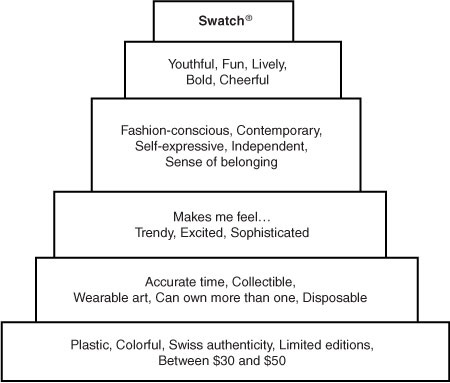

Brand promise is the second P in our Plan to Win. Identifying the promise requires thoughtfulness and creativity. We use a process called the Brand Pyramid to help construct the brand promise.

The Brand Pyramid reflects a simple approach that generates the input used to define the brand promise. It consists of five levels:

• Brand features—The bottom level of the Brand Pyramid. The brand features provide the credible support that provides the evidence of the truth of the promise.

• Functional benefits—What does this brand do for the target customer?

• Emotional rewards—How does this brand make the target customer feel when the functional benefits are delivered?

• Consumer values—Who is the target customer in terms of attitudes, beliefs, opinions, interests, and lifestyles?

• Brand personality—What is the personality of the brand that differentiates it in the mind of the target customers and makes it so personally appealing?

The functional benefits and the emotional rewards together create the brand claim. The brand values and brand personality together create the brand character.10 We create the brand promise using the brand claim and the brand character.

We creatively extract the brand promise from the words, thoughts, and ideas in each level of the Brand Pyramid (see Figure 4.2). The brand promise is a statement describing the intended promised experience of your brand. It is a definition of what we want to be. It is our brand aspiration. Combined with input from the segmentation research and other information, only you and your core team as well as select top management can define the vision for the brand. It is not about guesswork. It is about informed judgment.

We once taught a class using the INSEAD-CEDEP Swatch case.11 From that document and from newspaper and magazine clippings, we created this Brand Pyramid example for the Swatch brand (see Figure 4.3).

Combined with consumer insight, and input from executives, the next step is to synthesize this information, apply it to understanding your Brand Pyramid, and then complete the following Brand Promise contract (see Table 4.1).

Over the years, many of our clients have gone through this process to help restore relevance by updating the promise of a brand that had lost its way.

Defining the brand promise is an important strategic step for revitalizing brand relevance. But, to communicate this idea to the organization, we need to find a shorthand way of stating it, a way that will instantly provide a tonality and attitude to all employees, all communications, and all restaurants and their owners. You might call it a rallying cry; we call it a brand essence.

The brand essence captures the core spirit of the brand. It is a compelling and essential phrase. It is the phrase that unambiguously states how we are relevantly differentiated from our competitors. It is a phrase that describes what motivates our customers.

It is not enough to define the brand essence. It is also important to define what we mean by that phrase. We call this the brand essence dictionary. The dictionary defines the several dimensions of meaning of the brand essence.

A common language with common meanings for commonly used words and phrases is really just good common sense. We should all mean the same things when we say the same things.

We use this Lotus Blossom tool to identify the four to six key words that will help further define the brand essence. It ensures that we create a common book of language so that, regardless of who the employees are, where the employees reside, or what language they speak, we all have a consistent interpretation of the brand.12

For example, CNBC’s “World Wide Exchange” program, on May 19, 2008, presented an interview with David Procter, CEO, Al Khaliji Bank. He mentioned that his bank was ready for a variety of growth opportunities and that these opportunities meshed with the bank’s five core values: Bold, Cool, Swift, Exciting, and Reliable. It was as if the Lotus Blossom with the five dimensions of the bank’s brand were filled in (see Figure 4.4).13

For one client, we interviewed 86 people at all levels of the organization. We asked each person to define a phrase commonly used in the organization—a phrase that is at the heart of what the brand stands for. There were 86 different ways of defining this critically important phrase. Inconsistent interpretation leads to inconsistent implementation.

The brand essence along with the dimensions in the brand dictionary guide training, product development, marketing, store design, and so forth. With “Forever Young” as the brand goal for McDonald’s, we needed to make sure that the interpretation of this simple phrase was consistent around the world.

What is the disciplined process for defining the brand essence and its dimensions? There is none. It is a stroke of creativity that comes from intuitively understanding the Brand Pyramid, the brand promise, the market cube, the consumer information, and the vision for the brand. But, informed insight is not guesswork. There are, however, four guiding principles:

• Base this on a consumer insight.

• Be consistent with Brand Pyramid and brand promise.

• Use as much information as possible.

• Creatively synthesize the information.

At McDonald’s, the brand essence was born from reviewing hundreds of documents, including research studies, speeches, articles and books on McDonald’s, books on food and eating, a press clipping file from 1990 to 2002, online information searches, and selected interviews with executives at McDonald’s, a few who had worked closely with Ray Kroc. It took a synthesist to see what the brand essence was.

Often the best expression of a brand essence is a paradox promise. The concept of the paradox promise underpins many brands’ promised experience. Consumers hate to trade-off benefits. If you want to drink a diet cola, it is certainly much better to have one that has only 1 calorie and also tastes great. Madge the manicurist once promised for Palmolive dishwashing liquid, “It’s hard on dishes. It’s soft on your hands.” Miller Lite defined the light beer market as promising “Great taste. Less filling.” Paradox promises can be terrific opportunities. It is worth a lot when you own a paradox promise in the customer’s mind.14

Our insight was that McDonald’s represented a paradox promise opportunity.

The striking juxtaposition of opposites led to the insight of the essence of McDonald’s being a promised experience that is:

• Familiar yet modern

• Global yet local

• Simple yet enjoyable

• Comfortable yet entertaining

• Consistent yet changing

• Superior quality yet very affordable

With these paradoxes unveiled, the brand essence that focused the new direction for McDonald’s was that it represented youthful exuberance yet had strong roots. The brand challenge was to maintain and strengthen McDonald’s distinctive heritage and make it relevant again. We saw that one of the things that would make McDonald’s so wonderful was that its core values could be relevant forever but their interpretation had to change with the times. The brand challenge was to keep McDonald’s “Forever Young” forever.

A relevant brand promise and brand essence can align a disparate organization and provide inspiration and focus. The brand promise is the statement of the promise that the brand will deliver to every customer, every time, everywhere.

The Do’s and Don’ts of Restoring Relevance

Do

• Gain superior understanding of the customer—Know your target customer better than your competitors. Make sure that you have a clear definition of your target market(s). You should be able to describe your priority segment customers as if they were your best friends.

• Be inspiring—Make sure the brand promise statement is compelling and motivating, even or especially in hard times. People want uplift, not undertow.

• Create three-dimensional market segmentation—Segmenting on what, who, why, or context each alone is insufficient. Life is not one-dimensional; people are not one-dimensional; and so neither should your segmentation be one-dimensional.

• Have a consumer-based view of the marketplace—Let your customers’ needs and unmet needs create the competitive set. You will be surprised. Understand your brand’s perception by market segment.

• Synthesize your information—Go beyond just mere analysis to gain some ideas about the future opportunities and promise of your brand. Generate some critical insights. Be consumer-insight driven.

• Prioritize your segments—Apply focus to the mini cubes and make decisions based on your capabilities, future capabilities, value of each segment, and insights into which hold the potential for your brand. You cannot focus on everything at once. As with everything in life, pick your battles wisely.

• Create your Brand Pyramid and brand promise—Even if you have one, review it using this format. Keeping a brand contemporary and in sync with the current viewpoints and insights is essential to your brand’s health. And remember, this is not filling in the blanks: You are crafting something that will live with your brand for a long time.

• Conduct competitive analysis within segments—Understand the competitive sets from your customers’ perspective.

• Use your needs-based segments as windows on the world—There are opportunities in the identified market cubes. You are really segmenting for innovation and for ideas. Somewhere inside each cube is a terrific new concept.

• Don’t promise genericization—Being generic, offering generic category benefits leads to being a commodity product with no relevant differentiation. When you stand for everything general, you stand for nothing special.

• Don’t conduct template management—Template management is not brand management. Template management lacks passion and understanding. It means you are fabulous at filling in forms. Be passionate about every word and phrase in your Brand Pyramid and brand promise.

• Don’t maintain a mass market mentality—Especially in today’s world, this is death-wish marketing. Mass market messages lead to genericization.

• Don’t be trapped by a nonviable set of segments—Choose your segments wisely based not only on your insight and foresight but also on your current policies and resource capabilities. And, don’t fall on your sword for segments that make no sense.

• Don’t believe that anyone can be a creative synthesist—Anyone can draw, but how many Monets do you have on your team? Find the synthesist in your ranks or hire one. Do not spend money on creative trainers. Sure, it is a lot of fun to juggle and play games off-site, but true creativity through synthesis is something that only certain people can do.

1 “Did Somebody Say a Loss,” The Economist, April 12, 2003.

2 When our consulting firm begins a project, we ask for information. The list of the kinds of information we ask for is in Chapter 9, “Realizing Global Alignment: Creating a Plan to Win,” in the section, “Step 1: Brand Direction.”

3 Branco, Anthony, “The Vanishing Mass Market,” BusinessWeek, July 12, 2004.

4 Wilson, A., “One Ford, Many Key Segments,” Automotive News, April 30, 2007.

5 Barbaro, Michael, “Gap Closing Chain Aimed at Over-30s,” The New York Times, February 27, 2007.

6 Barbaro, Michael, “It’s Not Only About Price at Wal-Mart,” The New York Times, March 2, 2007.

7 Anderson, Chris, “Finding Ideas,” Harvard Business Review, November 2003, 18-19. Also see Gardner, Howard, The Five Minds for the Future, Boston: Harvard Business Review Press, 2007. Howard Gardner provides a clear understanding of the differences and overlaps of synthesizers and creative thinkers.

8 Birchall, Jonathan, “Best Buy Plots its Global Strategy,” Financial Times, May 13, 2008.

9 This concept was shared publicly on various occasions during 2004; for example, Advertising Age, June 2004 and Association of National Advertisers, October 2004.

9 Loesser, Frank, “Sue Me,” Guys and Dolls, 1950.

10 LG Electronics uses a similar approach that is available for review on its corporate Web site. LG discusses how it understands the LG brand in terms of values, promise, benefits, and personality. LG Global Web site, www.lge.com, May 27, 2008.

11 INSEAD-CEDEP, 1987, Distributed by ECCH at Babson Ltd., Babson College, Babson Park, MA; Taylor, William, “Message and Muscle: An Interview with Swatch Titan Nicolas Hayek,” Harvard Business Review, March-April 1993.

12 For a full description of the Lotus Blossom technique, see Higgins, James M., 101 Creative Problem Solving Techniques: The Handbook of New Ideas for Business, Winter Park, FL: New Management Publishing, 1994, 144.

13 “World Wide Exchange,” CNBC, interview with David Procter, May 19, 2008.

14 For an interesting perspective on paradox promise, namely Reingold, Jennifer, “Target’s Inner Circle,” Fortune, March 31, 2008: “Target markets itself to the Lexus set as a designer haven while at its core it makes money selling commodities such as bleach and cereal.” A former Target executive is quoted as saying, “People have within themselves a paradox. Fit in and belong; and also stand out and be unique. Target does both: mass and class.”