6. A Better Devil’s Advocate

“A coach is someone who can give correction without causing resentment.”

—John Wooden

The Roman Catholic Church declares certain very special deceased women and men to be saints. What does it mean to be a saint? The Catholic Church bestows this honor upon individuals who lived extraordinary lives of virtue and holiness. Catholics ask the saints to pray for them, to intercede on their behalf with God. As individuals try to improve themselves and serve others more effectively, they look to the saints as exemplars.

To become a saint, a person must be nominated after he or she has died. Then an investigation takes place. Church officials examine how that person lived, what he or she wrote, and what type of impact the person had on the world. They also look for evidence that the person performed a miracle. To become a saint, a person must be credited with having performed at least two miracles.

People ultimately become saints through a process called canonization. Centuries ago, the Catholic Church made the process quite stringent, intending the naming of a saint to be a rare event. To ensure that a candidate truly deserved to be named a saint, Pope Sixtus V designated a church official to play a special role in the canonization process. In 1587 he assigned someone to serve as Promoter of the Faith, otherwise known as the Devil’s Advocate (Advocatus Diaboli). He directed the Promoter of the Faith to prepare, in writing, all the arguments for why someone did not deserve to be declared a saint. The supporters of a person’s cause needed to overcome the objections and critique of the devil’s advocate to succeed during the canonization process.

Pope John Paul II amended the canonization process during the early years of his tenure at the Vatican. In 1983 he eliminated the office of Promoter of the Faith. John Paul II wanted to increase the number of saints, to create a so-called “fast track.” He aimed to provide more modern-day exemplars for his people, to demonstrate that people could live very holy lives even in an increasingly secular world. He also hoped that some of these new saints would come from geographic regions and cultures that had few saints of their own at that time.

During his tenure, Pope John Paul II canonized approximately 500 individuals—5 times the number that had been canonized in the four centuries since the time of Sixtus V. Removing the Promoter of the Faith as the devil’s advocate clearly had a major impact. Without that strong opposing viewpoint, more candidacies moved successfully and quickly through the canonization process.1

The Devil’s Advocate in Business

The Catholic Church may have initiated the use of devil’s advocates, but over the centuries, other organizations have also embraced the concept. In recent years, many business leaders have adopted devil’s advocacy technique. They recognize that you sometimes need to force an opposition viewpoint into the conversation. In so doing, you can increase the quality of decisions being made.

Consider the case of Ori Hadomi, CEO of Mazor Robotics. Hadomi’s firm produces state-of-the-art robotic guidance systems for spine surgery. Hadomi and his management team take a critical look at themselves at the end of each year. They identify the five biggest mistakes that have been made and work on establishing goals and objectives for the year ahead. Hadomi hunts for patterns among the mistakes. Several years ago, the management team noticed that they often settled on a set of rosy assumptions when making plans. Hadomi explains:

One of the most obvious mistakes we found is that often we choose to believe in an optimistic scenario—we think too positively. Positive thinking is important to a certain extent when you want to motivate people, when you want to show them possibilities for the future. But it’s very dangerous when you plan based on that. So one of our takeaways from that was to appoint one of the executive members as a devil’s advocate.2

The vice president of Sales for International Markets serves as the devil’s advocate at Mazor Robotics. He surfaces and probes crucial assumptions. As a result, the firm generates more realistic objectives and plans. Hadomi comments:

He’s actually very challenging and he knows how to ask the right questions. He really makes sure to say to me, “Let’s be more humble with our assumptions.” And the most surprising thing is that he’s the V.P. of sales for international markets. You would expect the V.P. of sales to be pie-in-the-sky all the time. But he has a very strong, critical way of thinking, and it is so constructive. I feel that in a way, one of the risks of leadership is thinking too positively when you plan and set expectations.3

How many executives have you heard use the phrase “Let me play the devil’s advocate for a moment”? The phrase comes up quite often in many organizations. However, the Devil’s Advocacy approach does not always enhance organizational effectiveness. It can do more harm than good at times. For that reason, this particular method of stimulating conflict and debate warrants further investigation.

Research on Devil’s Advocacy

Several decades ago, a group of scholars began evaluating the Devil’s Advocacy technique. These researchers believed that this technique could help protect against groupthink. A series of experimental studies compared the Devil’s Advocacy approach to the Dialectical Inquiry method described in Chapter 2, “Deciding How to Decide.” Most research did not find a substantial difference in the quality of decisions generated from these two approaches. However, the scholars did find a distinction between these two methods for inducing debate and a third “free discussion” approach, the Consensus technique, that emphasized trying to reach agreement as a team. For instance, David Schweiger, William Sandberg, and James Ragan devised an experimental study in the mid-1980s to compare these three approaches to group decision making. They asked teams of MBA students to tackle a strategic management case study and develop recommendations for the firm’s management team. A panel of expert judges evaluated the decisions that they made. Schweiger, Sandberg, and Ragan found that the Devil’s Advocacy approach yielded significantly better quality choices than did the Consensus approach.4 A subsequent study confirmed the findings using teams made up of managers from three divisions of a Fortune 500 company.5

How and why do devil’s advocates improve decision quality? Do they simply help battle test ideas and assumptions? My colleagues and I recently conducted a study to examine one other potential beneficial effect of the Devil’s Advocacy approach. We hypothesized that a devil’s advocate may help uncover information that one or more individuals hold privately. In so doing, the team may make a more informed decision.6

Several decades ago, Garold Stasser and his colleagues conducted a series of interesting studies about information sharing in groups.7 In one study, they created a murder mystery with a series of clues that could be used to determine who committed the crime. They presented three possible suspects for the murder. If people analyzed the clues properly, they could exonerate two individuals and conclude accurately that the third individual murdered the victim. The scholars asked individuals to tackle the murder mystery and tracked their success rate. Then they asked small groups to try to solve the same murder mystery. For these teams, the scholars distributed the clues unevenly. They distributed some information to all members of the groups. They provided other clues only to specific members. Thus, group members had a mix of private and shared information. The researchers discovered that individuals outperformed groups by a wide margin on this task!8

Why did the groups stumble? Stasser and his colleagues argued that groups do not tend to pool unshared information effectively. Groups often focus their discussion on information commonly possessed by all members. Individuals typically do not disclose data that they possess but that others do not. Incomplete disclosure occurs even when team members share a common goal. Team performance often suffers when members fail to disclose privately held information. Some tasks and decisions require the integration of each member’s information and expertise; just one member’s failure to disclose and share privately held information can impair the team’s ability to accomplish its task effectively.

My colleagues Brian Waddell, Sukki Yoon, and I decided to reexamine this murder mystery recently. For our study, we did not compare individuals to teams. Instead, we examined the performance of two types of teams. Half of our groups followed the identical instructions used in the original experiments by Stasser. The remaining teams tried to solve the same murder mystery, but we assigned one team member to play the role of devil’s advocate. What did we discover? The teams with devil’s advocates significantly outperformed the other groups; they achieved a much higher success rate at solving the mystery. Our research shows that the Devil’s Advocacy approach can do more than just lead to better critique and evaluation of assumptions and alternatives. It can help bring to light crucial information that otherwise would not be shared and integrated effectively.9

The Downside of Devil’s Advocacy

Devil’s advocates can enhance the quality of group decisions. They help us probe assumptions, critique options, and bring to the surface hidden risks. They might help us bring more information to the table that otherwise would not be shared. What’s the downside? Consider some of the words that we often hear used to describe the task of a devil’s advocate: “He plays the contrarian. He pokes holes in all our arguments.” “She tears apart our plans.” “He exposes all the flaws in our arguments.” “She tells us all the reasons our ideas won’t work.” Think about these phrases for a moment. Do they sound like descriptions of constructive criticism?

In too many situations, devil’s advocates focus a great deal of energy on tearing down the ideas that have been put forth by other members of the team. They serve as roadblocks to every creative proposal that others generate. Proponents of an idea become defensive rather quickly. Emotions flare up, and interpersonal conflict skyrockets. If the devil’s advocate has enough power and status in the organization, he or she might come close to exercising veto power on crucial decisions. A loud voice, coupled with power, enables a contrarian to impose his or her will on the group. Other team members become frustrated because it becomes increasingly difficult to accomplish anything new or different. The devil’s advocate can seem to preserve the status quo and inhibit transformative ideas from taking root.

Inspiring Divergent Thinking

How can a devil’s advocate help a team without creating frustration, anger, and defensiveness? We must rethink the purpose of this technique. We have to imagine a very different role for the devil’s advocate within a team. The best devil’s advocates do not focus on tearing others down, or simply finding the weaknesses in the plans being presented. Instead, they try to encourage others to think differently about a problem. They nudge them to examine an issue from a different vantage point or to generate more options for resolving a problem.

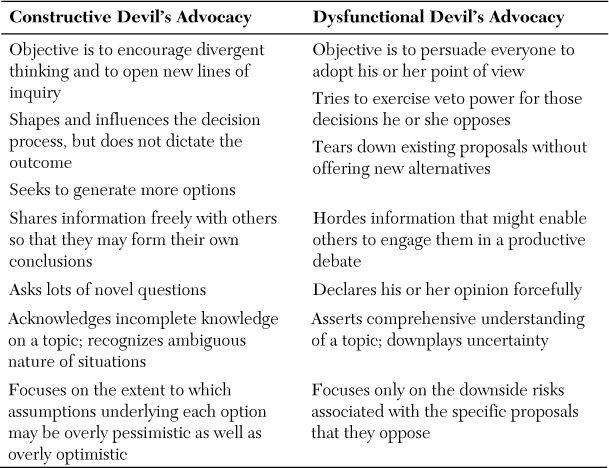

An effective devil’s advocate tries to open up new lines of inquiry rather than simply shut down proposals that may seem flawed or inadequate. An effective devil’s advocate does not always aim to sway people to his or her side on an issue. Instead, that person poses a scenario or a set of questions so that people may discover new options for themselves. A constructive devil’s advocate does not always challenge another group member’s arguments on his or her own. Instead, the devil’s advocate tries to encourage a dialogue through which others can question the logic and supporting evidence presented by their peers. In short, a constructive devil’s advocate strives to inspire more divergent thinking and create a thoughtful conversation rather than simply spark a confrontation. Table 6.1 below provides a comprehensive comparison between a constructive and a dysfunctional devil’s advocate.

Table 6.1 Two Types of Devil’s Advocates

More Than Changing Others’ Minds

A fascinating stream of research has examined how a minority can influence a majority’s thinking within a group. In one early study, Moscovici, Lage, and Naffrechoux assembled groups of six. They asked each group to examine the color of some slides, which were all identical in color—clear blue, in fact. In each group of six, the researchers placed two confederates (that is, subjects behaving as instructed in advance by the researchers). In one-third of the groups, the researchers asked the two confederates to identify each slide as green rather than blue. In a second set of groups, the two confederates identified the slides as green two-thirds of the time; on the remaining occasions, they correctly labeled the slides as blue. Finally, in the control condition, the confederates reported the true color of the slides—blue.

What happened? The four subjects identified the color of the slides correctly when working alone, as well as in the control condition. Interestingly, they also classified the color accurately when the two confederates did not dissent on a consistent basis. However, when the two confederates always asserted that the slides were green, roughly 8% of the subjects agreed with the minority view (which was incorrect!). The experiment shows that a consistent dissenting view can influence a majority within a group. It can actually sway people to change their positions, even to move from a correct choice to an incorrect one.

University of California–Berkeley psychologist Charlan Nemeth argues that consistent minority views do not add value simply by convincing others to change their mind. Dissenters can enhance group effectiveness by spurring divergent thinking. Here’s how she demonstrated her point: In one experiment, she created sets of letters such as this one: PATren. She asked participants to identify the three-letter word that they first noticed. Naturally, most people say “pat” in response to this request if they are provided no information about how others analyzed the set of letters.

Nemeth created two other experimental conditions. In one scenario, she told subjects that three other participants had identified a backward sequence of letters—such as “tap”—when looking at PATren. In that case, most subjects went along with the majority and began to look for backward sequences of letters in each subsequent set.

In a second scenario, Nemeth informed subjects that three people noticed a forward sequence such as “pat” in each set of letters, but one person noticed a backward sequence such as “tap.” Amazingly, when the participants looked at subsequent sets of letters, they did not settle into a stable pattern. People did not stick to either the forward or backward sequence. They formed words using all sorts of combinations—forward sequences, backward sequences, and mixed sequences. They made more words overall than the participants in the other scenarios. In short, knowing that one person looked at the letters quite differently stimulated participants to examine the strings from multiple perspectives. Minority dissent truly opened their minds.10

A devil’s advocate, then, does not need to aim to change people’s positions on an issue. In fact, trying to change people’s minds may be futile. It might simply cause them to retrench and affirm their existing beliefs more fervently. Pushing people to abandon their preexisting positions might spark an interpersonal confrontation that could derail or fragment the group. Instead, a good devil’s advocate may simply plant a seed that helps people see the world differently on their own.

Constructive Techniques

Devil’s advocates may employ a series of techniques to enhance their effectiveness. First, they can adopt lessons from improvisational comedy. In so doing, they can learn how to critique others in a positive manner. We will take a look at how Pixar has developed one such method for constructive criticism, based upon the techniques used by improv actors and actresses. Second, devil’s advocates must look in the mirror and examine their own biases. Sometimes, these “blinders” can make it difficult for a devil’s advocate to remain objective and fair when evaluating others’ ideas. Third, devil’s advocates must learn to ask better questions. Many critics and contrarians spend a great deal of time making statements rather than inquiring and probing. They declare opposition to certain ideas or cite emphatically the flaws in someone’s argument or plan. Effective devil’s advocates spend more time asking questions than issuing declarations. We next examine the most effective types of questions that one may employ.

The “Plussing” Technique

Pixar, the computer-generated animated film company, has created a remarkable string of blockbuster hits over the past two decades. Pixar’s first feature film, Toy Story, became a sensation upon its release in 1995. Widely acclaimed by critics, it grossed nearly $200 million in the United States. In subsequent years, Pixar has developed and released a string of blockbuster hits, including Finding Nemo, Cars, and The Incredibles.

How does Pixar create such spectacular films? What happens during the creative process? Andrew Stanton, the director of Finding Nemo, explains the company’s film-making philosophy: “My strategy has always been: be wrong as fast as we can, which basically means: we’re gonna screw up. Let’s just admit that. Let’s not be afraid of that.”11 The company does not begin working on a movie by writing a script. Instead, it creates rough storyboards. Pixar applies rigorous critique to these early ideas and then iterates as quickly as possible. Stanton and his team developed nearly 100,000 storyboards for WALL-E, an Academy Award–winning film released in 2008.

How does rigorous critique occur at Pixar? How do the film makers keep the conversations positive and productive? Pixar draws upon the lessons of improvisational comedy. When actors interact with one another in an improv sketch, they accept one another’s ideas and build upon them. They use a “yes, and” approach. They take what’s been given to them and find a way to move forward rather than dismiss an idea as outlandish or nonsensical.

The great comedienne Tina Fey launched her career at Second City, one of the best improvisational comedy troupes in the world. She went on to star for a decade on NBC’s long-running sketch comedy series Saturday Night Live. Fey describes the “yes, and” technique eloquently in her best-selling book, Bossypants:

So if we’re improvising and I say, “Freeze, I have a gun,” and you say, “That’s not a gun. It’s your finger. You’re pointing your finger at me,” our improvised scene has ground to a halt. But if I say, “Freeze, I have a gun!” and you say, “The gun I gave you for Christmas! You bastard!” then we have started a scene because we have AGREED that my finger is in fact a Christmas gun. Now, obviously in real life you’re not always going to agree with everything everyone says. But the Rule of Agreement reminds you to “respect what your partner has created” and to at least start from an open-minded place. Start with a YES and see where that takes you.12

Fey goes on to explain why a “can-do” attitude works much more effectively than a negative mentality. She comments that many people begin a conversation by citing all the reasons that a particular idea can’t work. She finds that “can’t-do” mentality very counterproductive:

As an improviser, I always find it jarring when I meet someone in real life whose first answer is no. “No, we can’t do that.” “No, that’s not in the budget.” “No, I will not hold your hand for a dollar.” What kind of way is that to live? The second rule of improvisation is not only to say yes, but YES, AND. You are supposed to agree and then add something of your own. If I start a scene with “I can’t believe it’s so hot in here,” and you just say, “Yeah...” we’re kind of at a standstill. But if I say, “I can’t believe it’s so hot in here,” and you say, “What did you expect? We’re in hell.” Or if I say, “I can’t believe it’s so hot in here,” and you say, “Yes, this can’t be good for the wax figures.” Or if I say, “I can’t believe it’s so hot in here,” and you say, “I told you we shouldn’t have crawled into this dog’s mouth,” now we’re getting somewhere. To me YES, AND means don’t be afraid to contribute. It’s your responsibility to contribute. Always make sure you’re adding something to the discussion. Your initiations are worthwhile.13

By adopting a “yes, and” mentality, improvisational comedy actors try to avoid blocking others’ ideas or stopping the flow of new information. They want to keep the conversation moving forward rather than shift into reverse and replay previous parts of a scene. They might shift a conversation onto a different path, but they don’t go back to a previous fork in the road.

Drawing upon the principles of improv comedy, Pixar deploys a technique that it calls “plussing.” Directors and supervisors do not reject ideas or sketches outright in most cases. They try to find some element of a sketch that has merit and build on that concept. They might acknowledge the value of a particular approach but then inquire as to how it might be done differently. It often involves asking “what if” questions. Animator Victor Navone explains, “You always want to present your ideas in a constructive manner and be respectful of the other animator’s feelings. I usually start my suggestions with ‘what if’ or ‘would it be clearer if” [the character] did it this way.”14

Pixar directors try not to always tell people how to do things differently. Instead, they try to nudge them in a slightly different direction and then let the animators work out the specifics. They do not want to micromanage the animators or dictate to them how to do their work. However, they do want to strive for excellence. They push relentlessly to achieve a level of precision that is truly incredible. However, the directors use “plussing” to provide feedback, while leaving the animators a good deal of autonomy in terms of improving the film.

To make the “plussing” technique work, you need to build a culture that is tolerant of failure. Sometimes you cannot resolve a conflict through argument alone. Two people may have opposing viewpoints, and no clear answer emerges from the constructive debate. Information remains ambiguous, and too many assumptions cannot be validated simply through analysis and argument. In those instances, devil’s advocates should encourage people to conduct small, rapid, relatively inexpensive experiments. In so doing, people can try out new ideas and learn very quickly. They can test hypotheses and move forward rather than simply continue to revisit an unproductive debate.

Pixar encourages people to take risks and acknowledges that failures will occur. Animators constantly experiment and try out new plot ideas. Of course, they also have become adept at cutting their losses when an experiment fails. Animators derive lessons from their failures and incorporate that learning into the next trial. Randy Nelson, former dean of Pixar University, argues, “The core skill of innovators is error recovery not failure avoidance.”15 IDEO has built a failure-tolerant culture as well. Founder David Kelley proclaims the mantra “Fail often to succeed sooner.” The company practices “enlightened trial and error” and rapid prototyping rather than debating opposing viewpoints ad infinitum.16

Confronting Your Own Biases

In many situations, devil’s advocates come to the conclusion that proponents of a particular proposal “need to take the blinders off.” In other words, they believe that those proponents have adopted a narrow perspective on an issue. They complain about the silo thinking of others. However, devil’s advocates often do not acknowledge their own biases. No one engages in a critique of others as a blank slate. We all bring our preconceived notions and prior hypotheses to an issue. To be effective, though, a devil’s advocate must try to shed those blinders. Wiping the slate clean does not just mean that the critique is more “rational” or logical. Confronting personal biases openly and honestly also makes others feel that a devil’s advocate is trying to be as fair as possible. As we will see in the upcoming chapters, perceptions of fairness matter a great deal in a collaborative decision-making process.

Psychologists have shown that confirmation bias is one of the most pernicious traps for decision makers. Put simply, people tend to focus on information that will confirm their preexisting views and positions. Moreover, we often avoid or downplay discordant data that may challenge our prior beliefs.

Consider the study conducted by Charles Lord, Lee Ross, and Mark Lepper of Stanford University, mentioned in Chapter 5, “Keeping Conflict Constructive.” They asked 151 undergraduates to respond to a simple survey regarding their attitudes toward capital punishment. They asked them if they favored the death penalty or not and whether they believed capital punishment has a deterrent effect (that is, does it discourage people from committing murder?). Several weeks later, Lord and colleagues gathered together some of the proponents and opponents of the death penalty. They asked the individuals to examine the results of studies conducted about the efficacy of capital punishment as a deterrent. Everyone had an opportunity to analyze research that supported the deterrence hypothesis as well as research that did not support the notion of the death penalty as a deterrent.17

What did these scholars find? The supporters of the death penalty tended to find the studies supporting their preexisting position to be quite convincing, clearly more persuasive than the research that opposed their prior beliefs. Similarly, opponents of capital punishment found the anti-deterrence research to be more persuasive. Perhaps most interestingly, everyone’s views became more polarized after they examined the research. Proponents became more in favor of the death penalty. Opponents shifted further toward the opposite view. In short, looking at an equal amount of information on both sides of an issue did not bring people together. It did not moderate their views. Instead, people became more entrenched in their existing positions. Why? The confirmation bias, of course. People focused on the information that bolstered their preexisting views and beliefs.

We all encounter the confirmation bias as we process information and examine issues. Organizations occasionally take advantage of this bias as they market goods and services to us. Take the large media organizations, for instance. Fox News and MSNBC clearly understand the confirmation bias. For that reason, the producers at those networks do not try to “play it down the middle” when reporting and analyzing the news. Instead, they provide us what we want to hear and see—that is, news and commentary that will bolster our preexisting political beliefs.

Devil’s advocates will never be able to avoid the confirmation bias completely. We cannot defy human nature. However, devil’s advocates can step back and look at their prior beliefs. They can question whether preexisting views have distorted the critique that they are putting before the group. As a devil’s advocate, ask yourself these types of questions: Are you predisposed to support or oppose a particular concept or plan? What information are you marshaling as you critique this proposal? Have you allowed prior views to distort your analysis and conclusions? How would someone with different prior views examine this issue?

Devil’s advocates must be honest with themselves. If they cannot put aside their own preexisting beliefs, then they should step aside. They should find someone else to occupy this crucial role in the decision-making process. Leaders have to assess the devil’s advocates as well. They should try to determine the extent to which the person occupying the role can provide an impartial critique. If a particular individual cannot be impartial, then perhaps the leader should assign another team member to play the role.

In addition to evaluating the vulnerability to the confirmation bias, devil’s advocates should assess their expectations. What types of advocacy and behavior do they expect from other team members? What do they expect to see as the conclusion of a particular type of analysis? What agendas do they expect to be promoted by various departments or units of the organization?

Expectations shape our behavior a great deal. In many instances, we see what we expect to see. As a result, we may arrive at erroneous conclusions. Devil’s advocates must be sensitive to the fact that their expectations about certain people, groups, and issues may distort their critique of a particular proposal.

To understand the power of expectations, let’s take a look at what occurred one morning in a Washington, DC, subway station. In 2007, Washington Post writer Gene Weingarten worked with classical violinist Joshua Bell to see if they could hoodwink local citizens on their way to work. Bell has earned widespread accolades for his musical prowess and has performed with many of the great orchestras and symphonies of the world. Several years ago, he earned the Avery Fisher prize, a prestigious award for outstanding achievement by an American in classical music.

On a busy weekday morning, Bell went to the L’Enfant Plaza metro stop in Washington, DC. He wore a t-shirt and baseball cap. Bell found a spot near an escalator, and he took out his $3.5 million Stradivarius violin. Bell left his violin case open to accept donations from passersby. For the better part of the next hour, the award-winning violinist performed in that subway station. He started by playing “Chaconne” by Johann Sebastian Bach. Bell described this classical piece as “not just one of the greatest pieces of music ever written, but one of the greatest achievements of any man in history. It’s a spiritually powerful piece, emotionally powerful, structurally perfect. Plus, it was written for a solo violin, so I won’t be cheating with some half-assed version.”18

Many people—1,097 individuals, in fact—passed by and barely noticed him. They went about their normal daily routine. Only 7 people stopped for a minute to listen to the beautiful music. Twenty-seven people donated money to him. He collected a paltry $32. Bell had treated the commuters of Washington, DC, to a beautiful free concert, yet they had not appreciated it. Most had no idea what they had just witnessed and heard.

What’s the lesson from the story of Joshua Bell? We see what we expect to see. We hear what we expect to hear. No one anticipates hearing one of the world’s great classical violinists in that environment. On that morning, some people who passed by had little knowledge of classical music. However, quite a number of people did appreciate and understand that music. Their expectations clouded their judgment. Expectations blinded them to the reality of the situation.

Devil’s advocates must be wary of allowing expectations to distort their judgment. How can they accomplish that difficult task? For starters, before engaging with a team of decision makers, they should consider the types of behaviors, events, and information that they anticipate seeing and hearing. What are the usual patterns of behavior within this team? What are the typical conclusions that a person draws from this type of data? Then the devil’s advocate should take some time to consider the actions and events that would shock or surprise the team members. What do they not anticipate seeing or hearing? Making these two lists of the expected and unexpected can help counter the type of bias that makes many critiques highly flawed.

Questions, Not Declarations

John Houseman starred as Professor Charles Kingsfield in the 1973 film The Paper Chase. The movie depicts the life of first-year students at Harvard Law School. In the opening scene, we witness the first day of class. Kingsfield begins by calling on James Hart to provide his view on a particular legal case involving potential medical malpractice. Hart has not prepared the case because he expected Professor Kingsfield to lecture on the first day of class. After the stern faculty member grills him for quite some time, Hart sits stunned. After class, Hart runs the men’s room to vomit.

A bit later in the film, Professor Kingsfield explains the Socratic method to these ambitious new law school students. Kingsfield explains:

We use the Socratic method here. I call on you, ask you a question, and you answer. Why don’t I give you a lecture? Because through my questions, you learn to teach yourselves...questioning and answering. At times, you may feel that you have found the correct answer. I assure you that this is a total delusion on your part. You will never find the correct, absolute, and final answer. In my classroom, there is always another question. We do brain surgery here....You teach yourselves the law, but I train your minds. You come in here with a skull full of mush, and you leave thinking like a lawyer.19

The devil’s advocate may be inclined to offer somber declarations at times in his or her critique of a specific proposal. He or she may assert that certain flaws exist in a plan or that the team has not considered several serious risks. At times, though, seemingly absolute and unyielding statements will provoke defensiveness on the part of the proponents of a plan. People may retreat to polarized camps. Flashes of anger may emerge.

An effective devil’s advocate never starts with stern declarations. He or she practices the Socratic method, much as Professor Kingsfield describes in The Paper Chase. A successful devil’s advocate focuses first on questions rather than statements. He or she probes and inquires into the logic, facts, and assumptions behind certain arguments. A devil’s advocate tries to uncover the cause–effect relationships that exist or that may be presumed incorrectly to exist.

The use of questions, rather than declarations, aims to inspire self-reflection on the part of a plan’s proponent. Through the Socratic method, the devil’s advocate encourages people to identify the weaknesses and risks of their own plans. If thoughtful questions spur self-critique, then the conversation tends to remain more constructive.

A devil’s advocate does not ask questions alone, though. In the Socratic method of teaching, the instructor does not ask all the questions. A good case method professor orchestrates a dialogue. In that way, he or she serves as a facilitator or moderator. The dialogue does not take place simply between instructor and student. It takes place among the students. When a student articulates a position, the faculty member sometimes plays the devil’s advocate himself. In many cases, though, the instructor turns to the class. He or she invites others to propose penetrating questions to their fellow student or to offer an opposing view. A devil’s advocate must do the same. He or she is a facilitator, not simply the sole contrarian and critic in the room. A devil’s advocate should invite others to ask thoughtful and constructive questions.

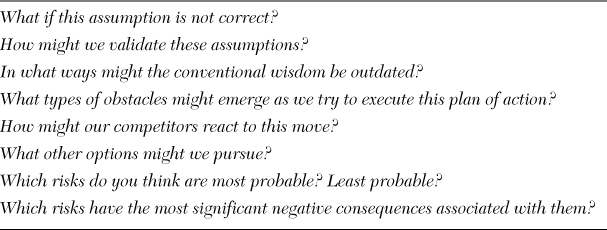

The best question that a devil’s advocate can ask is often: “Have you considered this other option?” Too often devil’s advocates spend all their time articulating the flaws and risks of a particular plan of action. They don’t present an alternative. Former IBM CEO Louis Gerstner used to say, “Don’t tell me about the flood. Build me an ark.”20 Referring to the story of Noah’s Ark from the Bible, Gerstner wanted to remind the contrarians in this organization to focus on identifying potential solutions, not just problems. A devil’s advocate can help stimulate divergent thinking in a team by putting new creative options on the table, even if some of those ideas are a bit impractical or far-fetched. For a list of provocative questions that a devil’s advocate may use, see Table 6.2.

The Broken Record

Devil’s advocates may use all the techniques described in this chapter yet still at times not be effective. Why? Individuals playing the role may be perceived as simply going through the motions. Alternatively, the person consistently playing the devil’s advocate on a team may become a “broken record” over time. Other team members may begin to dismiss the person’s comments after becoming tired of hearing similar critiques in the past.

Charlan Nemeth has conducted some research which suggests that authenticity is a crucial factor in the effectiveness of a devil’s advocate. In several experiments, she compares and contrasts an authentic dissenter with someone who plays the role of devil’s advocate but who may not actually believe the position he or she is taking. Her research suggests that an authentic dissenter may be more effective. Nemeth argues, “It is quite possible that because the authentic dissenter manifests both conviction and courage that people are stimulated to rethink their positions.”21

While these experiments are thought provoking, we should proceed with caution when drawing conclusions from lab studies. First, leaders don’t always have naturally occurring authentic dissent in a team. Sometimes we have to manufacture debate by assigning someone to play the role of devil’s advocate. Second, authentic dissenters in an actual management team often have entrenched positions of their own. Their arguments may provoke affective conflict or drive further polarization of views. The advocacy of an authentic dissenter does not always provoke divergent thinking; it could lead to stalemate. The bottom line: Leaders cannot count on the emergence of an authentic dissenter. They must cultivate dialogue when debate does not naturally occur. Using a devil’s advocate serves as one potentially effective technique for creating robust discussion.

What about the problem of becoming a broken record? Repeated critiques over time certainly can wear on a management team. If a devil’s advocate seems to keep coming back to the same tired arguments over time, people will become frustrated. They will stop listening. What can a leader do in these circumstances? He or she might consider rotating the role of the devil’s advocate. However, asking someone else to serve as the devil’s advocate has its risks. People tend to get better at playing the role effectively with experience. However, leaders may need to take that risk if the devil’s advocate has become a lonely, often dismissed voice of opposition.

Finally, leaders might want to ask two people to serve in the role of devil’s advocate. Why two individuals? Are two heads better than one? In stimulating dissent, strength may exist in numbers. If one person offers a highly divergent viewpoint, others may dismiss that individual as misguided or misinformed. If two people act together in expressing a dissenting view, others may step back before dismissing their critique. Fellow team members may not change their minds quickly. However, they might pause to rethink their position for just a moment. They might think to themselves, “If two other team members feel that way, perhaps there is some merit to that opposing viewpoint.”

Remember the Cuban missile crisis. President Kennedy employed devil’s advocates quite effectively. Interestingly, two people shared the role. Ted Sorensen and Robert Kennedy each served as intellectual watchdogs, probing and questioning the subgroups as they explored the alternative courses of action during that crisis.

Note that these two men were very close to John Kennedy. He trusted them a great deal, and he had worked with them for years. The devil’s advocate(s) should be someone with sufficient status in a team. Why? If a devil’s advocate has some power and status, he or she will not be dismissed or ignored easily. Members of the Kennedy administration knew that these two men had earned the president’s trust and respect. As a result, they listened closely to the dissenting views and probing questions that those two individuals put forth. We cannot just assign anyone to the role of devil’s advocate. We have to select team members who will be heard.

Endnotes

1. J. Allen. (2011). “John Paul II beatification: Politics of saint-making,” BBC News. www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-13207940, accessed January 2, 2013; D. Evans. (2011). “Canonizing the Saints, the Devil’s Advocate, and Mother Teresa.” http://suite101.com/article/canonization-of-saints-the-devils-advocate-and-mother-theresa-a334629, accessed January 2, 2013.

2. A. Bryant. (2011). “Every team should have a devil’s advocate,” New York Times. www.nytimes.com/2011/12/25/business/ori-hadomi-of-mazor-robotics-on-choosing-devils-advocates.html?pagewanted=all, accessed January 5, 2012.

3. Ibid.

4. D. M. Schweiger, W. R. Sandberg, and J. W. Ragan. (1986). “Group approaches for improving strategic decision making,” Academy of Management Journal. 29: pp. 51–71.

5. D. M. Schweiger, W. R. Sandberg, and P. L. Rechner. (1989). “Experimental effects of Dialectical Inquiry, Devil’s Advocacy, and Consensus approaches to strategic decision making,” Academy of Management Journal. 32: pp. 745–772.

6. B. Waddell, M. A. Roberto, and S. Yoon. (2013). “Uncovering Hidden Profiles: Advocacy in Team Decision Making.” Management Decision. 51(2): pp. 321–340

7. G. Stasser and W. Titus. (1985). “Pooling of unshared information in group decision-making: Biased information sampling during discussion,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 48(6): pp. 1467–1478.

8. G. Stasser and D. Stewart. (1992). “Discovery of hidden profiles by decision-making groups: Solving a problem versus making a judgment,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 63(3): pp. 426–434.

9. B. Waddell, M. A. Roberto, and S. Yoon. (2003).

10. C. Nemeth and J. Kwan. 1987. “Minority influence, divergent thinking, and detection of correct solutions,” Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 17: pp. 788–799.

11. P. Sims. (2011). “Pixar’s motto: Going from suck to nonsuck.” Fast Company. www.fastcompany.com/1742431/pixars-motto-going-suck-nosuck, accessed July 21, 2012.

12. T. Fey. (2011). Bossypants. New York: Reagan Arthur Books. p. 84.

13. Ibid.

14. P. Sims. (2011). Little Bets: How Breakthrough Ideas Emerge from Small Discoveries. New York: Free Press. p. 71.

15. R. Nelson. (2008). “Learning and Working in the Collaborative Age.” Apple Education Leadership Summit. www.edutopia.org/randy-nelson-school-to-career-video?page=1, accessed October 4, 2012.

16. T. Kelley. (2001). Art of Innovation: Lessons in Creativity from IDEO, America’s Leading Design Firm. New York: Crown Business.

17. C. Lord, L. Ross, and M. Lepper. (1979). “Biased assimilation and attitude polarization: The effects of prior theories on subsequently considered evidence,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 37: p. 2098.

18. G. Weingarten. (2007). “Pearls before breakfast,” Washington Post. www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/04/04/AR2007040401721.html, accessed December 14, 2012.

19. The Paper Chase. (1973). Twentieth Century Fox Corporation.

20. R. Foster and S. Kaplan. (1997). Creative Destruction: Why Companies That Are Built to Last Underperform the Market—And How to Successfully Transform Them. New York: Broadway Business. p. 163.

21. C. J. Nemeth and J. A. Goncalo. (2005). “Influence and persuasion in small groups,” in T. C. Brock and M. C. Green, eds., Persuasion: Psychological Insights and Perspectives. London: Sage Publications, pp. 171–194.